Initiële behandeling bij kinderen met epilepsie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de initiële behandeling van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen?

Aanbeveling

Bij patiënten met bekende epilepsie: het eigen coupeer protocol is leidend. Zie kinderformularium voor de juiste doseringen.

Thuissituatie

- Verstrek midazolam (0,2 mg/kg, maximum 10 mg) voor nasale toediening aan ouders/verzorgers van kinderen, indien er een indicatie is voor noodmedicatie.

- Bespreek met de ouders/verzorgers het gebruik van de noodmedicatie en dat deze na 5 minuten kan worden gegeven. Bespreek dat indien de eerste dosis midazolam nasaal na 5 minuten niet werkt, er direct de ambulance moet worden gebeld. Geef deze informatie ook schriftelijk mee.

Zorginstelling

- Geef als eerste keus midazolam (buccaal, nasaal of intramusculair). Hanteer bij voorkeur een eerste dosering midazolam van 0,2mg/kg (maximum dosering: 10 mg).

Bij onvoldoende resultaat:

- Indien niet kan worden voorzien in controle van de ademhaling en saturatiebewaking: bel ambulance.

- Indien wel kan worden voorzien in controle van de ademhaling en saturatiebewaking: dien als zorgverlener een tweede dosering midazolam van 0,2 mg/kg (buccaal, nasaal of intramusculair) toe. Zorg dat de tweede gift de maximum totale dosering van 0,4 mg/kg of 20mg niet overschrijdt.

- Indien na tweede gift onvoldoende effect: bel ambulance.

Ziekenhuissetting - spoedeisende hulp, ziekenhuisafdeling met bewakingsmogelijkheden van vitale functies, intensive care

- Volg het stroomschema, zie bijlage.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In de literatuur is gekeken naar de behandeling bij een gegeneraliseerde convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen. Er werden vijf studies (één netwerk meta-analyse, één systematic review, drie RCTs) gevonden over met convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen. Een breed scala aan eerste- en tweedelijns medicijnen worden in deze studies met elkaar vergeleken. De studiepopulaties in de gevonden studies zijn echter relatief klein, met enkele methodologische beperkingen (risk of bias, inconsistentie, imprecisie). De bewijskracht van de literatuur is daardoor zeer laag voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat seizure cessation en zeer laag voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat termination of SE after drug administration. Dit betekent dat nieuwe studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. Derhalve kunnen er op basis van de literatuur geen sterke conclusies worden getrokken over welk middel het meest effectief is en de voorkeur heeft bij de behandeling van een gegeneraliseerde convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen.

Eerstelijns behandeling

Verschillende studies hebben het stoppen van de status epilepticus na toedienen van medicatie als primaire uitkomstmaat onderzocht. Echter wordt hierbij de voorbereidingstijd veelal niet meegenomen in de metingen, wat een onderschatting kan geven van het daadwerkelijke tijdsbestek. Midazolam intramusculair is effectiever in het stoppen van aanvallen dan lorazepam intraveneus, het tijdsinterval van intentie tot behandeling tot stoppen van de aanval is zelfs korter (Silbergleit, 2012; Welch, 2015). Bij de werkgroep zijn geen gerandomiseerde studies bekend waarin midazolam intraveneus is vergeleken met lorazepam intraveneus. Uit ervaringen in de praktijk van het cluster lijkt lorazepam intraveneus een gelijkwaardig alternatief te zijn voor midazolam intraveneus. Dit beleid wordt ook in verschillende andere landen gevolgd. Zonder intraveneuze toegang kan beter eerst nasaal, buccaal of intramusculair met midazolam worden gecoupeerd, direct gevolgd door het aanbrengen van een intraveneuze toegang. Tegelijkertijd dienen de vitale functies te worden veilig gesteld (zie stroomschema). Zo snel mogelijk couperen draagt in belangrijke mate bij aan het veiligstellen van vitale functies. De snellere werking na intraveneus toedienen van medicatie gaat verloren door het tijdsverlies van het aanbrengen van een intraveneuze toegang. De noodzaak tot snel starten met behandeling wordt verder onderbouwd door een observationele studie (Gainza-Lein, 2018). Deze studie toont aan dat een delay in behandeling tot een slechtere uitkomst leidt.

In een recente systematische review (Chhabra, 2021: gepubliceerd na het uitvoeren van deze search dd. 21-06-2021) werd midazolam intranasaal vergeleken met andere toedieningsvormen van benzodiazepines en werd de tijd tussen aankomst in het ziekenhuis en het stoppen van de status epilepticus onderzocht. Intranasaal midazolam bleek in een kortere tijd (gemiddeld verschil: -3,51 minuten; 95%CI -6,84 tot -0,18) hetzelfde effect te bereiken als andere toedieningsvormen van benzodiazepines.

Omtrent de verschillende toedieningsvormen is een beperkt aantal studies bekend waarbij ouders of verzorgers intranasaal of rectaal middelen hebben toegediend (Jeannet, 1999; Holsti, 2010). In beide studies werd intranasaal midazolam vergeleken met diazepam rectaal, beide studies tonen aan dat het geven van 0,2 mg/kg intranasaal midazolam in de thuissituatie veilig en effectief is. Diazepam rectiole heeft een gunstigere kostenprofiel en langere houdbaarheid dan midazolam intranasaal. Desalniettemin stelt het cluster dat midazolam nasaal als eerste keus middel wordt gebruikt als noodmedicatie in de thuissituatie, gezien de snellere werking ten opzichte van diazepam rectiole. Ook vanuit patiëntenperspectief heeft midazalom de voorkeur (Jeannet, 1999; Holsti, 2010). In de situatie waarin diazepam rectioles thuis effectief zijn gebleken, is continueren hiervan mogelijk indien dit is genoteerd in het eigen coupeerprotocol.

Midazolam voor buccale toediening is in Nederland geregistreerd. Dit zou gegeven kunnen worden bij neusverkoudheid of indien genoteerd in eigen coupeerprotocol. In zorginstellingen met verpleegkundig geschoold personeel kan behalve nasaal of buccaal ook intramusculair medicatie worden toegediend. Als een kind op de spoedeisende hulp of ziekenhuisafdeling reeds een infuus heeft, dan is intraveneuze toediening het snelst en meest effectief.

Het is momenteel nog onvoldoende onderzocht welk tijdsinterval met welke toedieningsvorm het meest effectief is. Hier ligt een kennislacune. Doch het is waarschijnlijk moeilijk een studie op te zetten waarbij ultravroege behandeling versus vroege behandeling na 5 minuten gaat vergelijken.

Ten aanzien van de gebruikte dosis, zijn er substantiële verschillen in gehanteerde dosis tussen verschillende studies te vinden. De werkgroep is van mening dat het veiliger is om in de aanbevelingen een dosis te vermelden en niet een range aan mogelijke doses. Middels een eenduidige dosis kunnen vergissingen worden voorkomen. Daarnaast voorkomt het benoemen van een standaard dosis dat hetzelfde kind in de ene situatie een relatief lage dosis krijgt en in een andere situatie een hoge dosis terwijl hier geen geldende reden voor is. De werkgroep hoopt dat op deze manier een meer eenduidig standaard beleid wordt toegepast in de klinische praktijk.

Tweedelijnsbehandeling

Hoewel studies geen grote verschillen in effectiviteit laten zien, heeft het cluster op basis van bekende bijwerkingen, veiligheid en gemaksoverwegingen uit de praktijk een voorkeur voor levetiracetam als behandeling van een kind met een convulsieve status epilepticus. In de praktijk wordt in toenemende mate levetiracetam gebruikt, in plaats van fenytoïne of valproaat. Mogelijke voorkeuren van levetiracetam zijn de korte toedieningstijd (tijdwinst) en het ontbreken van hemodynamische en respiratoire bijwerkingen. Daarnaast zijn er voor levetiracetam geen absolute contra-indicaties en fatale complicaties bekend, zoals dit wel voor fenytoïne en valproaat geldt (Garbovsky; 2015; Mindikoglu, 2011). Daarnaast kan levetiracetam 40 mg/kg worden opgeladen bij kinderen die reeds levetiracetam gebruiken (Lyttle, 2019). Er zijn in Nederland weinig kinderen die fenytoïne onderhoud gebruiken. Echter het moment dat een kind fenytoïne onderhoud gebruikt, is het niet mogelijk om met fenytoïne op te laden bij een status epilepticus. Of het mogelijk is valproaat op te laden bij kinderen die valproaat gebruiken is onbekend. Bij het cluster zijn geen subgroepen bekend waarvoor het positieve effect van levetiracetam niet zou gelden.

Bij gelijke effectiviteit wegen aspecten als bijwerkingen zwaarder meer. Cardiovasculaire aandoeningen, respiratoire insufficiëntie of andere potentiële bijwerkingen moeten goed overwogen worden door de behandelaar. Levetiracetam lijkt de veiligste optie bij kinderen. Ook hier geldt dat indien fenytoïne of valproaat in een eerdere situatie bij hetzelfde kind is gebruikt met goed resultaat, er geen reden is om deze keuze te wijzigen naar het oordeel van het cluster indien dit genoteerd staat in het eigen coupeerprotocol.

Onvoldoende resultaat na tweedelijns behandeling

Indien er ± tien minuten na de tweedelijnsbehandeling onvoldoende resultaat is behaald, dient contact te worden opgenomen met de kinder intensive care voor overleg over behandeling en eventuele opname. Daadwerkelijk opnemen is afhankelijk van lokale en regionale afspraken (zie stroomschema).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het belangrijkste doel van de middelen is het stopzetten en voorkómen van nieuwe epileptische aanvallen. In de thuissituatie speelt het gebruikersgemak van de toedieningsvorm een belangrijke rol bij de keuze van middelen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen economische evaluaties bekend met betrekking tot deze uitgangsvraag.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In de literatuuranalyse wordt fosfenytoïne vergeleken met levetiracetam (Abdelgadir, 2020; Chamberlain, 2020; Nalisetty, 2020; Senthil, 2018). Echter wordt dit middel niet geleverd in Nederland en is dit fosfenytoïne niet door de EMA geregistreerd.

Er is geen kwantitatief of kwalitatief onderzoek bekend naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van de behandeling met status epilepticus bij kinderen. Met vergelijkbare effectiviteit van de middelen, zijn de bijwerkingen en de toedieningssnelheid van de middelen een groot bezwaar voor zowel de behandelend zorgverlener als voor de patiënt.

Figuur 1. Stroomschema: Behandeling status epilepticus bij kinderen in de ziekenhuissetting

Zie bijlage

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Uit onderzoeken uit het buitenland blijkt dat kinderen met een convulsieve status epilepticus frequent pas laat medicamenteus behandeld worden. Kinderen die laat behandeld worden zijn ook moeilijker te behandelen en hebben een slechtere uitkomst (Gainza-Lein, 2018). Het is onbekend of dit in Nederland ook het geval is.

In deze module worden de mogelijkheden geëvalueerd om epileptische aanvallen te couperen buiten het ziekenhuis (bijvoorbeeld thuis, buitenshuis op school, instellingen voor kinderen met een beperking) of in het ziekenhuis (bijvoorbeeld bij epilepsiecentra, op ziekenhuisafdelingen met mogelijkheid tot monitorbewaking of op een spoedeisende hulp). Afhankelijk van de situatie waarin medicatie gegeven moet worden, zijn er immers meer of minder mogelijkheden tot het toedienen van medicatie en controle op de bijwerkingen hiervan. De mogelijkheden en inzet van ambulancepersoneel valt buiten het doel van deze richtlijnmodule.

In de literatuur wordt veelal onderscheid gemaakt tussen eerstelijns- en tweedelijnsmiddelen. Anticonvulsiva zijn bedoeld een epileptische aanval te beëindigen, de eerst gegeven anticonvulsiva worden veelal eerstelijns benoemd. Als dit onvoldoende effect heeft, dan wordt de behandeling aangevuld met tweedelijns middelen, veelal bestaande uit anti-aanvalsmedicatie. Anti-aanvalsmedicatie worden gebruikt om epileptische aanvallen te voorkomen. Een aantal anti-aanvalsmedicatie wordt ook gebruikt in de behandeling van een status epilepticus. De vraag is welke toedieningsvorm de voorkeur heeft, en daarnaast welke middelen in aanmerking komen.

Deze module heeft als doel om middels een duidelijk beleid, te voorkomen dat vertraging ontstaat in de medicamenteuze behandeling van een status epilepticus bij kinderen. Deze module evalueert welke eerstelijns- en tweedelijns behandeling het meest effectief en gunstig is voor convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen. Dit betreft een update van de module ‘Status Epilepticus bij kinderen - Buiten het ziekenhuis’ en de module ‘Status Epilepticus bij kinderen - Spoedeisende hulp’ d.d. juni 2020 (inclusief de zoekstrategie d.d. 1 januari 2019).

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. First-line seizure management: diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, and paraldehyde

1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the additional effect of diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, and paraldehyde on seizure cessation when these first-line treatments are compared in children with status epilepticus.

The evidence is very uncertain about the additional effect of intramuscular midazolam on seizure cessation when compared with buccal midazolam in children with status epilepticus.

Sources: Zhang, 2021; Alansari, 2020 |

2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of intramuscular midazolam on termination of SE after drug administration when compared with buccal midazolam in children with status epilepticus.

Sources: Alansari, 2020 |

4. Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, and paraldehyde on the requirement for ventilatory support when these first-line treatments are compared in children with status epilepticus.

Sources: Zhang, 2021 |

7. Length of hospital stay (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, and paraldehyde on length of stay when these first-line treatments are compared in children with status epilepticus.

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of intramuscular midazolam on length of stay when compared with buccal midazolam in children with status epilepticus.

Sources: Zhang, 2021; Alansari, 2020 |

3. Mortality (important); 5. Hypotension (important)

| - GRADE | The outcome measure ‘mortality’ was not graded, as outcomes were not reported. The outcome measure ‘hypotension’ was not graded, due to the very low number of events.

Sources: N.A. |

2. Second-line seizure management: fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate

1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate on seizure cessation when these second-line treatments are compared in children with status epilepticus.

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of intramuscular midazolam on seizure cessation when compared with buccal midazolam in children with status epilepticus.

Sources: Zhang, 2021; Abdelgadir, 2021; Handral, 2020; Nazir, 2021 |

2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on termination of SE after drug administration when compared with phenytoin or phenobarbital in children with status epilepticus.

Sources: Abdelgadir, 2021; Nazir, 2021 |

4. Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate on the requirement for ventilatory support when these second-line treatments are compared in children with status epilepticus.

Sources: Zhang, 2021 |

7. Length of hospital stay (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate on length of stay when these second-line treatments are compared in children with status epilepticus.

Sources: Zhang, 2021 |

3. Mortality (important); 5. Hypotension (important)

| - GRADE | The outcome measure ‘mortality’ was not graded due to the very low number of events.

Sources: N.A. |

The conclusions below remain maintained, as no new literature was found for the following comparisons.

Huidige conclusies - Kinderen > Couperen buiten het ziekenhuis (Richtlijn 2020)

Toedieningswijze benzodiazepines

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat nasale, buccale en intramusculaire toediening van benzodiazepines prettiger worden bevonden door patiënten en zorgverleners dan rectale toediening.

Sources: Haut, 2016 |

Midazolam buccaal vs. diazepam rectaal

| MODERATE GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat behandeling met buccaal midazolam effectiever is dan rectaal diazepam om een epileptische aanval <10 minuten te doen staken.

Sources: Jain, 2016 |

Midazolam intramusculair

| LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat behandeling met intramusculair midazolam het meeste effect heeft ter coupering van een aanval in vergelijking met andere toedieningsvormen. Er zijn aanwijzingen dat behandeling met intramusculair midazolam het snelst toegediend kan worden in vergelijking met andere toedieningsvormen.

Sources: Arya, 2015; Zhao, 2016 |

Midazolam intranasaal

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat behandeling met intranasaal midazolam het frequentst zorgde voor het stoppen van een aanval in vergelijking met andere toedieningsvormen.

Sources: Arya, 2015 |

Lorazepam rectaal/intraveneus vs. diazepam rectaal

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat behandeling met lorazepam rectaal (0.05-0.1 mg/kg) een grotere kans geeft op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen dan behandeling met diazepam rectaal (0.3-0.4 mg/kg; max. 10 mg).

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat ademdepressie minder vaak optreedt bij behandeling met lorazepam (intraveneus en rectaal) dan bij behandeling met diazepam.

Sources: Appleton, 2008 |

Midazolam buccaal vs. diazepam rectaal

| MODERATE GRADE | Het is waarschijnlijk dat behandeling met midazolam buccaal (max. 10 mg) een grotere kans geeft op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen dan behandeling met diazepam rectaal (max. 10 mg), zonder dat er verschillen zijn in het optreden van ademdepressie.

Sources: McMullan, 2010 |

Huidige conclusies - Kinderen > Couperen op de spoedeisende hulp (Richtlijn 2020)

Midazolam intramusculair vs. lorazepam intraveneus

| VERY LOW GRADE | Behandeling met midazolam intramusculair (13-40 kg: 5 mg; >40 kg: 10 mg) lijkt een grotere kans te geven op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen dan behandeling met lorazepam intraveneus (13-40 kg: 2 mg; >40 kg: 4 mg). Midazolam heeft een minstens een even snel resultaat bij een gelijke kans op complicaties of noodzaak tot intubatie, en bij midazolam intramusculair komen minder vaak ziekenhuis- en intensive care-opnames voor.

Sources: Silbergleit, 2012; Welch, 2015 |

Levetiracetam intraveneus vs. lorazepam intraveneus

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat behandeling met levetiracetam intraveneus (20 mg/kg) een even grote kans geeft op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen als behandeling met lorazepam intraveneus (0.1 mg/kg). De kans op hypotensie of noodzaak tot beademing lijkt groter bij behandeling met lorazepam intraveneus dan bij levetiracetam intraveneus.

Sources: Misra 2012 |

Valproaat intraveneus vs. fenytoïne intraveneus

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat behandeling met valproaat intraveneus (20-30 mg/kg) een grotere kans geeft op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen dan behandeling met fenytoïne intraveneus (18-20 mg/kg) en daarbij veiliger is met betrekking tot het optreden van hypotensie of ademdepressie.

Sources: Misra, 2006; Agarwal, 2007 |

Midazolam nasaal vs. diazepam intraveneus

| MODERATE GRADE | Het lijkt waarschijnlijk dat behandeling met midazolam nasaal (0.2 mg/kg) een even grote kans geeft op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen als behandeling met diazepam intraveneus (0.2-0.3 mg/kg), zonder dat er aanwijzingen zijn voor verschil in optreden van ademdepressie.

Midazolam nasaal kan sneller toegediend worden dan diazepam intraveneus, waardoor de aanval vanaf aankomst op de SEH sneller gestopt kan worden dan met diazepam intraveneus.

Sources: Thakker, 2010; Lahat, 2000; Mahmoudian, 2004 |

Lorazepam intraveneus vs. diazepam intraveneus

| LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat lorazepam intraveneus (0.05-0.1 mg/kg) een even grote kans geeft op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen als behandeling met diazepam intraveneus (0.2-0.4 mg/kg).

Er zijn aanwijzingen dat ademhalingsdepressie even vaak optreedt bij behandeling van kinderen met een convulsieve status epilepticus met lorazepam als bij behandeling met diazepam.

Sources: Sreenath, 2010; Appleton, 2008; Appleton, 1995 |

Lorazepam rectaal vs. diazepam rectaal

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat behandeling met lorazepam rectaal (0.05-0.1 mg/kg) een grotere kans geeft op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen dan behandeling met diazepam rectaal (0.5 mg/kg of 10 mg).

Sources: Appleton, 2008 |

Lorazepam rectaal vs. diazepam rectaal

| HIGH GRADE | Het is aangetoond dat behandeling met midazolam buccaal (max 10 mg) een grotere kans geeft op het stoppen van een convulsieve status epilepticus bij kinderen dan behandeling met diazepam rectaal (max 10 mg), zonder dat er verschillen zijn in het optreden van ademdepressie.

Sources: McMullan, 2010 |

Midazolam intramusculair/nasaal vs. lorazepam intraveneus vs. diazepam intraveneus/ rectaal

| LOW GRADE | Intramusculair of nasaal midazolam en intraveneus lorazepam zijn effectiever dan intraveneus of rectaal diazepam.

Intramusculair of nasaal midazolam is minstens even effectief als intraveneus lorazepam bij de behandeling van pediatrische status epilepticus.

Sources: Zhao, 2016 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Zhang (2021) performed a systematic review and network meta-analyses (NMA) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of various anti-seizure medications in paediatric patients with status epilepticus.

Inclusion criteria were pediatric patients (aged 1 month to 18 years), patients diagnosed with convulsive status epilepticus, and RCTs. Various dosage and administration routes were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were mixed populations (pediatric and adult patients) without an age subgroup analysis, studies with participants who did not meet the definition of ‘convulsive status epilepticus’, participants who received the study drug prior to admission, sample size ≤30 patients, and study design that was not an RCT. Three databases (PubMed, Embase, Cochrane) were searched up to May 2020.

Sixteen RCTs with a total of 3.397 paediatric patients were included, of which eight RCTs (n=1.689; Lahat, 2000; Ahmad, 2006; Mpimbaza, 2008; Sreenath, 2010; Chamberlain, 2014; Malu, 2014; Momen, 2015; Welch, 2015) were conducted in untreated patients and eight RCTs were conducted in patients who required second-line treatment (n=1.711; Malamiri, 2012; Burman, 2019; Dalziel, 2019; Lyttle, 2019; Noureen, 2019; Chamberlain, 2020; Nalisetty, 2020; Vignesh, 2020). Leading RCTs like the ConSEPT (Dalziel, 2019), EcLiPSE (Lyttle, 2019) and ESETT trial (Chamberlain, 2020) were included in this NMA.

Four first-line (midazolam, diazepam, lorazepam, paraldehyde) and five second-line (valproate, phenobarbital, phenytoin, fosphenytoin, levetiracetam) antiseizure medications were assessed in the pediatric population. The definition of ‘convulsive status epilepticus’ was comparable between studies.

Regarding risk of bias, selection bias of the reported results was the most frequent bias observed, followed by bias due to deviations from intended interventions, measurement bias, and randomization bias. Despite interventions not being blinded to participants and caregivers in some studies, outcome measurement was unlikely to be affected. Missing outcome biases were assessed as low for all RCTs.

Relevant outcome measures included seizure cessation (critical), respiratory depression (important), and length of stay (important).

Abdelgadir (2020) performed a systematic review and meta-analyses to evaluate the efficacy and safety of levetiracetam in treating convulsive status epilepticus in childhood. Inclusion criteria were pediatric patients (aged 1 month to 18 years) and RCTs that compared intravenous levetiracetam with any other treatment for convulsive status epilepticus. Four databases (Medline, Embase, Cinahl, Cochrane) were searched up to April 2020. Ten RCTs with a total of 1.907 paediatric patients were included. Leading RCTs like ConSEPT (Dalziel, 2019), EcLiPSE (Lyttle, 2019) and ESETT (Chamberlain, 2020) were included in this study. Three comparisons were available:

- Intravenous levetiracetam vs. intravenous phenytoin (Lyttle, 2019; Dalziel 2019; Noureen, 2019; Sharma, 2019; Singh, 2018; Vignesh, 2020; Wani, 2019);

- Intravenous levetiracetam vs. intravenous fosphenytoin (Chamberlain, 2020; Nalisetty, 2020; Senthil, 2018); and

- Intravenous levetiracetam vs. intravenous valproate (Chamberlain, 2020; Wani, 2019).

Relevant outcome measures included drug administration to seizure cessation (critical), termination of SE after drug administration (critical), mortality (important), respiratory depression (important), and length of stay (important).

Regarding intravenous levetiracetam, this systematic review includes more RCTs (n=10) in comparison to the NMA (n=6) performed by Zhang (2021). Because a NMA can combine both direct and indirect evidence and thus involves more comparisons, we reasoned from Zhang (2021) in this module. As Zhang (2021) did not assess the outcome measures ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ and ‘mortality’, we used the data from Abdelgadir (2020). For all other outcome measures, we checked the NMA with Abdelgadir (2020) whether the direction of effects was similar.

Leading RCTs like the ConSEPT (Dalziel, 2019), EcLiPSE (Lyttle, 2019) and ESETT (Chamberlain, 2020) are included in both the NMA and systematic review (Zhang, 2021; Abdelgadir, 2020). The ConSEPT trial (Dalziel, 2019) and the EcLiPSE trial (Lyttle, 2019) compared phenytoin versus levetiracetam for second-line management of paediatric convulsive status epilepticus. The ConSEPT trial included 233 children (phenytoin n=114, levetiracetam n=119) and the EcLiPSE trial included 286 children (phenytoin n=134, levetiracetam n=152). The ESETT trial (Chamberlain, 2020) compared the efficacy and safety of levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, and valproate in established status epilepticus. In this study, 225 children (fosphenytoin n=71, levetiracetam n=85, valproate n=69) participated.

Alansari (2020) conducted an RCT to compare the efficacy and safety of intramuscular midazolam with buccal midazolam as first-line treatment for active seizures in children brought to the emergency department. A total of 150 children presenting with acute convulsive seizure were randomized into intramuscular midazolam and buccal midazolam. In the intramuscular midazolam-group were 75 children (mean age: 49 ± 46 months, 41M/34F) and in the buccal midazolam-group were 75 children (mean age: 45 ± 37 months, 33M/42F). Intramuscular midazolam consisted of 0.25 mg/kg (maximum 8 mg), and the buccal midazolam consisted of 0.30 mg/kg (maximum 10 mg). Follow-up period was until discharge from the hospital.

Relevant outcome measures include (time from) drug administration to seizure cessation (critical); (duration of) persistent seizure cessation (critical); respiratory depression (important), hypotension (important), and length of hospital stay (important).

Handral (2020) conducted an RCT to compare the efficacy and safety of intravenous levetiracetam and intravenous fosphenytoin in the management of pediatric status epilepticus. If seizures persisted even after two doses of lorazepam, participants were randomized to receive either levetiracetam (30 mg/kg) or fosphenytoin (30 mg/kg) and followed for 48 hours. In the levetiracetam-group were 58 children (mean age: 3.09 ± 2.98 years, 32M/26F) and in the fosphenytoin-group were 58 children (mean age: 3.77 ± 3.79 years, 36M/22F). Outcome measures were seizure cessation (critical) and respiratory depression (important). In the methods section was stated that hypotension was assessed, but results were not reported in the article.

Nazir (2020) conducted an RCT to compare the efficacy and safety of intravenous phenytoin, intravenous levetiracetam and intravenous valproate as second-line status epilepticus treatment in children. A total of 150 patients were randomly assigned to three groups: the phenytoin-group (loading dose: 20 mg/kg diluted in NS at a rate <1 mg/kg/min, maintenance dose: 5 mg/kg/day in two divided doses); the levetiracetam-group (loading dose: 25 mg/kg at 3 mg/kg/min, maintenance dose: 25 mg/kg/day divided 12 hourly), and the valproate-group (loading dose: 25 mg/kg at 3 mg/kg/h, maintenance dose: 20 mg/kg/day in divided doses 12 hourly). Follow-up period was 3 months. Outcome measure was seizure cessation (critical) and termination of status epilepticus after drug administration (critical).

This search contains an update from the guideline dd. 17 June 2020. No new literature is found regarding the following comparisons:

- benzodiazepines (nasal, buccal, intramuscular)

- lorazepam (intravenous, rectal) vs. diazepam (rectal)

- lorazepam (rectal) vs. diazepam (rectal)

- lorazepam (intravenous) vs. levetiracetam (intravenous)

- midazolam (buccal) vs. diazepam (rectal)

- midazolam (nasal) vs. diazepam (intravenous)

- midazolam (intramuscular) vs. lorazepam (intravenous)

- midazolam (intranasal)

- valproate (intravenous) vs. phenytoin (intravenously)

Thus, the pervious conclusions remain valid. The description of previous included studies is presented as Appendix 1 and 2 (2020).

Results

1. First-line seizure management

1.1 Network: Diazepam versus lorazepam versus midazolam versus paraldehyde

1.1.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

In total, 1,686 patients were randomized to receive first-line intervention, including midazolam, diazepam, lorazepam, and paraldehyde. This NMA reported odds ratio to estimate risk, however, an odds ratio results to an overestimation of the risk because the outcome is not rare. Therefore, risk ratios have been used to assess the evidential value, rather than odds ratios.

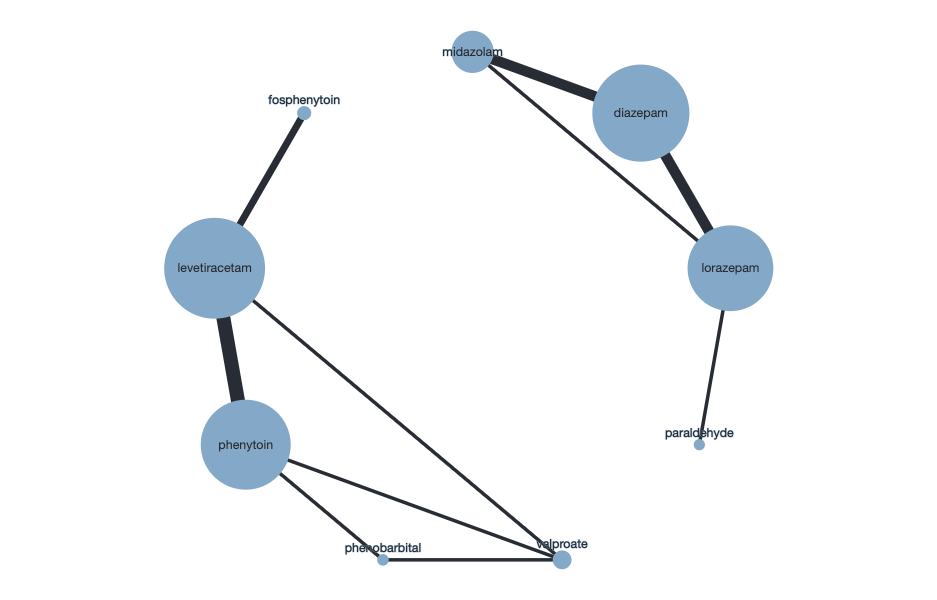

Figure 1 shows the network of first- and second-line seizure management comparisons. Direct and mixed comparison for seizure cessation between these drugs did not show statistically significant differences as therapies showed similar effects in seizure cessation (see Table 1). Regarding seizure cessation, the results of this NMA (Zhang, 2021) are supported by the outcomes of the meta-analysis performed by Abdelgadir (2021).

Table 1 First-line seizure management - outcome comparison of seizure cessation. Data were presented as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

| Diazepam | 1.073 (0.922, 1.248) | 1.001 (0.857, 1.168) | 1.313 (0.907, 1.901) |

| 0.932 (0.801, 1.085) | Lorazepam | 0.933 (0.767, 1.135) | 1.224 (0.874, 1.716) |

| 0.999 (0.856, 1.166) | 1.072 (0.881, 1.303) | Midazolam | 1.312 (0.889, 1.938) |

| 0.761 (0.526, 1.102) | 0.817 (0.583, 1.144) | 0.762 (0.516, 1.125) | Paraldehyde |

Figure 1 Network of included studies (Zhang, 2021). Right: first-line seizure management. Left: second-line seizure management.

1.1.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Not reported.

1.1.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the first-line seizure management, Zhang (2021) could not assess mortality in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values.

1.1.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

Seven first-line studies (Lahat, 2000; Ahmad, 2006; Mpimbaza, 2008; Sreenath, 2010; Chamberlain, 2014; Momen, 2015; Welch, 2015) were included in the first-line seizure management analyses. The comparison between midazolam versus diazepam resulted in a risk difference of 0.07 (95%CI -0.12 to 0.32). The comparison between midazolam versus lorazepam resulted in a risk difference of 0.06 (95%CI -0.14 to 0.29). The differences were not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

1.1.5 Hypotension (important)

Not reported.

1.1.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

Zhang (2021) evaluated ‘length of stay’ as patient admission to an ICU for second-line seizure management. Analyses on admission to the ICU was performed exclusively in second-line studies because most first-line studies did not have sufficient information for pooled data.

1.2 Intramuscular midazolam versus buccal midazolam

1.2.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

For the comparison between intramuscular midazolam and buccal midazolam, one study (Alansari; 2020) with 150 children assessed seizure cessation as seizure activity at five minutes. In the intramuscular midazolam-group 41 out of 75 (61%) patients had seizure cessation and in the buccal midazolam-group 32 out of 75 (46%) patients had seizure cessation. This resulted in a risk ratio of 1.28 (95%CI 0.92 to 1.79). This difference was clinically relevant, but not statistically significant.

1.2.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

For the comparison between intramuscular midazolam and buccal midazolam, time from administration of study medication until complete cessation of seizure activity was assessed by one study (Alansari, 2020).

Mean time from administration of study medication until seizure cessation was 15.9 minutes (SD 28.7) for the intramuscular midazolam-group and 17.8 minutes (SD: 27.5) for the buccal midazolam-group. This resulted in a mean difference of -1.90 minutes (95%CI -10.90 to 7.10). This difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant. The very broad confidence interval should be taken into consideration.

1.2.3 Mortality (important)

Not reported.

1.2.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

For the comparison between intramuscular midazolam and buccal midazolam, ‘respiratory depression’ was assessed by one study (Alansari, 2020). One patient in the intramuscular midazolam-group and none in the buccal midazolam-group developed depression three minutes after administration of study medication. Additionally, in the intramuscular midazolam-group 3 out of 67 patients (5%) patients and in the buccal midazolam-group 1 out of 70 patients (1%) required intubation through the course of treatment. This difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant. Caution is needed due to the very low number of events and the wide confidence interval.

1.2.5 Hypotension (important)

For the comparison between intramuscular midazolam and buccal midazolam, ‘hypotension’ was assessed by one study (Alansari, 2020). One patient in the intramuscular midazolam-group and none in the buccal midazolam-group developed hypotension three minutes after administration of study medication.

1.2.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

For the comparison between intramuscular midazolam and buccal midazolam, ‘length of stay’ defined by Alansari (2020) as admission to the overall length of stay, requiring PICU, and the and length of PICU stay. Mean length of hospital stay was 48.5 hours (SD: 103.4) in the intramuscular midazolam-group and 54.67 hours (SD: 119.8) in the buccal midazolam-group (mean difference: -6.17, 95%CI -43.59 to 31.25). In the intramuscular midazolam-group in 8 out of 67 patients (12%) and in the buccal midazolam-group group 12 out of 70 patients (17%) were admitted to the PICU (risk ratio: 0.70, 95%CI 0.30 to 1.60). Mean length of PICU stay was 148.3 hours (SD: 214.3) in the intramuscular midazolam-group and 73 hours (SD: 50) in the buccal midazolam-group (mean difference: 75.0, 95%CI -76.17 to 226.17). Caution is advised due to the low number of events and very large 95% confidence intervals.

2. Second-line seizure management

2.1 Network: fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, valproate

2.1.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

In total, 1,711 patients were randomized to receive the second-line intervention, including fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate. This NMA reported odds ratio to estimate risk, however, an odds ratio results to an overestimation of the risk because the outcome is not rare. Therefore, risk ratios have been used to assess the evidential value, rather than odds ratios.

Direct and mixed comparison for seizure cessation between these drugs did not show statistically significant differences as therapies showed similar effects in seizure cessation (see Table 2). Regarding ‘seizure cessation’, the results of this NMA (Zhang, 2021) are supported by the outcomes of the meta-analysis performed by Abdelgadir (2021) which also resulted in similar effects for ‘seizure cessation.

Tabel 2 Second-line seizure management - outcome comparison of seizure cessation. Data were presented as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

| fosphenytoin | 0.844 (0.642, 1.110) | 0.710 (0.476, 1.058) | 0.908 (0.668, 1.236) | 0.823 (0.599, 1.131) |

| 1.185 (0.901, 1.558) | levetiracetam | 0.841 (0.612, 1.155) | 1.076 (0.920, 1.259) | 0.975 (0.777, 1.224) |

| 1.409 (0.945, 2.101) | 1.189 (0.866, 1.633) | phenobarbital | 1.280 (0.945, 1.735) | 1.160 (0.865, 1.554) |

| 1.101 (0.809, 1.498) | 0.929 (0.794, 1.087) | 0.781 (0.576, 1.059) | phenytoin | 0.906 (0.715, 1.148) |

| 1.215 (0.884, 1.671) | 1.026 (0.817, 1.287) | 0.862 (0.643, 1.156) | 1.104 (0.871, 1.399) | valproate |

2.1.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Zhang (2021) could not assess ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values. The systematic review performed by Abdelgadir (2021) did assess time to clinical cessation of seizure activity for levetiracetam vs. phenytoin and levetiracetam vs. valproate, by using studies that were included in Zhang (2021). We incorporated these data in the section ‘levetiracetam versus phenytoin’ and ‘levetiracetam and valproate’.

2.1.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the second-line seizure management, Zhang (2021) could not assess mortality in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values. The systematic review performed by Abdelgadir (2021) did assess all-cause mortality for second-line levetiracetam vs. phenytoin and levetiracetam vs. valproate, by using studies that were included in Zhang (2021). We incorporated these data in the section ‘levetiracetam versus phenytoin’ and ‘levetiracetam and valproate’.

2.1.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

Five second-line studies (Malamiri, 2012; Burman, 2019; Nalisetty, 2020; Chamberlain, 2020; Vignesh, 2020) were included in the assessment of ‘respiratory depression’. Comparisons between levetiracetam versus valproate, phenobarbital versus valproate, phenytoin versus valproate, fosphenytoin versus valproate resulted in a risk difference of -0.01 (95%CI -0.30 to 0.48), 0.06 (95%CI -0.17 to 0.53), 0.11 (95%CI -0.25 to 0.53), 0.18 (95%CI -0.11 to 0.89), respectively. The differences regarding ‘respiratory depression’ were not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

2.1.5 Hypotension (important)

Zhang (2021) could not assess ‘hypotension’ in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values. This outcome was also not reported in Abdelgadir (2021).

2.1.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

Zhang (2021) evaluated ‘length of stay’ as patient admission to an ICU for second-line seizure management. The comparisons between valproate versus levetiracetam, phenobarbital versus valproate, phenytoin versus valproate, fosphenytoin versus valproate resulted in a risk difference of 0.40 (95%CI -0.03 to 0.66), 0.56 (95%CI 0.05 to 0.89), 0.29 (95%CI -0.12 to 0.55), 0.20 (95%CI -0.18 to 0.55), respectively. The difference between valproate and phenobarbital was statistically significant, but not clinically relevant. Additionally, Abdelgadir (2021) also did not detect statistically significant differences nor clinically relevant differences for length of stay in the ICU.

2.2 Intravenous levetiracetam versus valproate

2.2.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

This comparison is included in the NMA (Zhang, 2021).

2.2.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Abdelgadir (2021) and Nazir (2021) did not report assess time to termination of SE after drug administration for levetiracetam versus valproate. Zhang (2021) could not assess ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ for second-in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values.

2.2.3 Mortality (important)

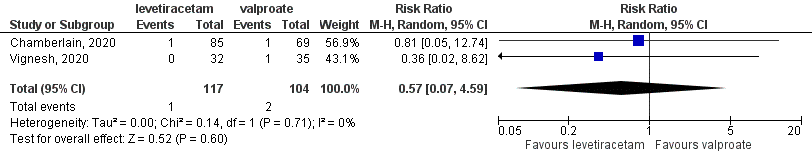

Zhang (2021) could not assess mortality in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values. Nazir (2021) did not report on mortality. The meta-analysis performed by Abdelgadir (2021) assessed all-cause mortality for levetiracetam versus valproate.

For the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, two studies (Vignesh, 2020; Chamberlain, 2020) with 221 participants were combined in meta-analysis (Abdelgadir, 2021). In the LEV group in 1 out of 117 patients (1%) died and in the VPA group 2 out of 104 patients (2%) died. This resulted in a risk ratio of 0.57 (95%CI 0.07 to 4.59), see Figure 2. This difference was not statistically significant but clinically relevant. Caution is needed due to the very low number of events and the wide confidence interval.

2.2.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

Not reported.

2.2.5 Hypotension (important)

Not reported.

2.2.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

This comparison is included in the NMA (Zhang, 2021).

2.3 Intravenous levetiracetam versus phenytoin

2.3.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

This comparison is included in the NMA (Zhang, 2021).

2.3.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

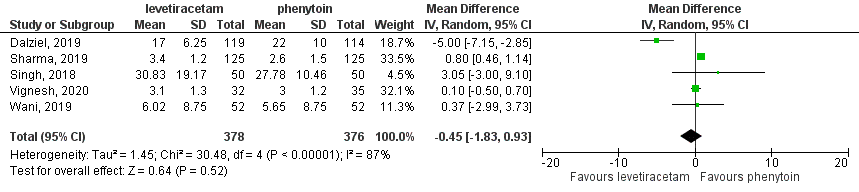

For the comparison between levetiracetam and phenytoin, five studies (Dalziel, 2019; Vignesh, 2020; Wani, 2019; Sharma, 2019; Singh, 2018) with 754 participants were combined in meta-analysis (Abdelgadir, 2021). Nazir (2021) did not report on ‘Termination of SE after drug administration’. When timing of cessation of seizure activities was compared

Figure 2 Comparison levetiracetam versus valproate: mortality

Figure 3 Comparison levetiracetam versus phenytoin: termination of SE after drug administration

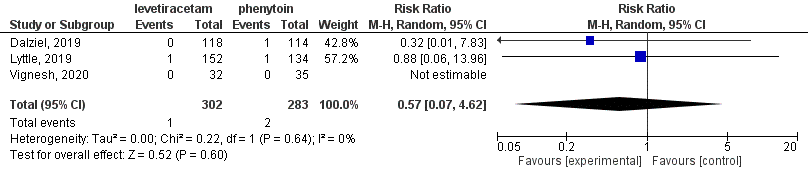

Figure 4 Comparison levetiracetam versus phenytoin: all-cause mortality

between the levetiracetam-group (n=378) and the phenytoin-group (n=376), the mean difference was -0.45 minutes (95%CI -1.83 to 0.93). This difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant (see Figure 3).

2.3.3 Mortality (important)

For the comparison between levetiracetam and phenytoin, three studies (Lyttle, 2019; Dalziel, 2019; Vignesh, 2020) with 585 participants were combined in meta-analysis (Abdelgadir, 2021). Nazir (2021) did not report on ‘mortality’. In the levetiracetam-group in 1 out of 302 patients (1%) died and in the phenytoin-group 2 out of 283 patients (1%) died. This resulted in a risk ratio of 0.57 (95%CI 0.07 to 4.62), see Figure 4. Considering the very low number of events and the broad confidence interval, this should be interpreted with caution.

2.3.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

Not reported.

2.3.5 Hypotension (important)

Not reported.

2.3.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

This comparison is included in the NMA (Zhang, 2021).

2.4 Intravenous levetiracetam versus fosphenytoin

2.4.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

This comparison is included in the NMA (Zhang, 2021).

2.4.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

For the comparison between levetiracetam and fosphenytoin, two studies (Nalisetty, 2019; Senthil Kumar, 2018) with 111 participants were combined in meta-analysis (Abdelgadir, 2021). The timing of cessation of seizure activities was 57 minutes in the levetiracetam-group (n=57) and the fosphenytoin-group (n=54), the mean difference was -0.70 minutes (95%CI -4.26 to 2.86). This difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

2.4.3 Mortality (important)

Not reported.

2.4.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

For the comparison between intravenous levetiracetam and fosphenytoin one study (Handral; 2020) assessed respiratory depression, but results were not stated in the article. The need of intubation was provided. Intubation was required in 1 out of 58 patients (2%) in the levetiracetam-group and in 3 out of 58 patients (5%) in fosphenytoin-group.

2.4.5 Hypotension (important)

Not reported.

2.4.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. First-line seizure management

1.1 Network: Diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, paraldehyde

1.1.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, and paraldehyde: the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference), and conflicting results between studies (-1; heterogeneity).

1.1.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

The outcome ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ was not reported and could not be graded.

1.1.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the first-line seizure management, Zhang (2021) could not assess ‘mortality’ in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values. Therefore, the level of evidence was not graded.

1.1.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

Regarding the comparison diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, and paraldehyde: the level of evidence regarding the outcome ‘respiratory depression’ started as high and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference), and conflicting results between studies (-1; heterogeneity).

1.1.5 Hypotension (important)

The outcome ‘hypotension’ was not reported and could not be graded.

1.1.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

Regarding the comparison diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, and paraldehyde: the level of evidence regarding the outcome ‘length of stay’ started as high and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference), and conflicting results between studies (-1; heterogeneity).

1.2 Intramuscular midazolam versus buccal midazolam

1.2.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison intramuscular midazolam to buccal midazolam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference and relatively small number of included patients).

1.2.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ started as high and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; because of wide confidence interval and relatively small number of included patients).

1.2.3 Mortality (important)

The outcome ‘mortality’ was not reported and could not be graded.

1.2.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘respiratory depression’ was not assessed due to the very low number of events.

1.2.5 Hypotension (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hypotension’ was not assessed due to the very low number of events.

1.2.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘length of hospital stay’ started as high and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference and relatively small number of included patients).

2. Second-line seizure management

2.1 Network: fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, valproate

2.1.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate: the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias) conflicting results between studies (heterogeneity), incoherence (disagreement between direct and indirect evidence), and/or imprecision (confidence interval cross one or both boundaries of clinical important difference).

2.1.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Zhang (2021) could not assess ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values. Therefore, the level of evidence was not graded.

2.1.3 Mortality (important)

Zhang (2021) could not assess ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ in quantitative NMA analysis because of missing outcomes and null values. Therefore, the level of evidence was not graded.

2.1.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

Regarding the comparison fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate: the level of evidence regarding the outcome ‘respiratory depression’ started as high and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias) conflicting results between studies (heterogeneity), incoherence (disagreement between direct and indirect evidence), and/or imprecision (confidence interval cross one or both boundaries of clinical important difference).

2.1.5 Hypotension (important)

The outcome ‘hypotension’ was not reported and could not be graded.

2.1.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

Regarding the comparison fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate: the level of evidence regarding the outcome ‘length of stay’ started as high and was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias) conflicting results between studies (heterogeneity), incoherence (disagreement between direct and indirect evidence), and/or imprecision (confidence interval cross one or both boundaries of clinical important difference).

2.2 Intravenous levetiracetam versus valproate

2.2.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

This comparison is included in the NMA - second-line seizure management

(Zhang, 2021).

2.2.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

The outcome ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ was not reported and could not be graded.

2.2.3 Mortality (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ was not graded due to the very low number of events.

2.2.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

The outcome ‘respiratory depression’ was not reported and could not be graded.

2.2.5 Hypotension (important)

The outcome ‘hypotension’ was not reported and could not be graded.

2.2.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

This comparison is included in the NMA - second-line seizure management

(Zhang, 2021).

2.3 Intravenous levetiracetam versus phenytoin

2.3.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

This comparison is included in the NMA - second-line seizure management

(Zhang, 2021).

2.3.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Regarding the comparison levetiracetam versus phenytoin, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference), and conflicting results between studies (-1; heterogeneity).

2.3.3 Mortality (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ was not graded due to the very low number of events.

2.3.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

The outcome ‘respiratory depression’ was not reported and could not be graded.

2.3.5 Hypotension (important)

The outcome ‘hypotension’ was not reported and could not be graded.

2.3.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

This comparison is included in the NMA - second-line seizure management

(Zhang, 2021).

2.4 Intravenous levetiracetam versus fosphenytoin

2.4.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

This comparison is included in the NMA - second-line seizure management

(Zhang, 2021).

2.4.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Regarding the comparison levetiracetam versus fosphenytoin, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference), and conflicting results between studies (-1; heterogeneity).

2.4.3 Mortality (important)

The outcome ‘mortality’ was not reported and could not be graded.

2.4.4 Requirement for ventilatory support (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘respiratory depression’ was not graded due to the very low number of events.

2.4.5 Hypotension (important)

The outcome ‘hypotension’ was not reported and could not be graded.

2.4.6 Length of hospital stay (important)

This comparison is included in the NMA - second-line seizure management (Zhang, 2021).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Which type, dosage and form of medication is most effective in the treatment of status epilepticus in children with convulsive status epilepticus?

P: Children with convulsive status epilepticus

I: Anti-seizure medication (such as diazepam, midazolam, lorazepam, phenytoin, valproate, levetiracetam, lacosamide, brivaracetam, or other new anti-seizure medication)

C: Same medication but other dosage and/or form; other type of medication, placebo

O: (time from) Drug administration to seizure cessation; (duration of) persistent seizure cessation (dichotomous and continuous); requirement for ventilatory support, hypotension, mortality, length of hospital stay

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered (time from) drug administration to seizure cessation, (duration of) continued seizure cessation, as a critical outcome measure for decision making; mortality, requirement for ventilatory support, hypotension, and length of hospital stay as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. Length of hospital stay is defined as the overall length of time a patient is hospitalized. The working group defined convulsive status epilepticus as acute convulsive seizures lasting for more than 5 minutes according to the ILAE definition.

Per outcome, the working group defined the following differences as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences.

Dichotomous outcomes (relative risk; yes/no):

- From drug administration to seizure cessation within certain period: RR ≥ 10%

- Persistent seizure cessation at least one hour: RR ≥ 10%

- Respiratory depression (requirement for ventilatory support): RR ≥ 10%

- Mortality: RR ≥ 10%

- Hypotension: RR ≥ 10%

Continuous outcomes:

- Time from drug administration to seizure cessation: ≥ 2 minutes

- Duration of persistent seizure cessation: ≥ 30 minutes

- Length of hospital stay: ≥ 2 days

Search and select (Methods)

The search strategy dated from 01-01-2019 was updated. The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 01-01-2019 (last search) until 21-06-2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. One search was conducted for all modules concerning status epilepticus. The search was limited to systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials. The systematic literature search resulted in 305 hits. Studies for this module were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic review (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available) or randomized controlled trial;

- full-text English language publication;

- children aged ≥1 month and <18 years;

- studies including ≥ 20 (ten in each study arm) patients; and

- studies according to the PICO.

After reading the full text five studies were included in the literature summary of this module.

Results

Five number of studies were included in the analysis of the literature, of which two systematic reviews and three randomized controlled trials. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Alansari K, Barkat M, Mohamed AH, Al Jawala SA, Othman SA. Intramuscular Versus Buccal Midazolam for Pediatric Seizures: A Randomized Double-Blinded Trial. Pediatr Neurol. 2020 Aug;109:28-34. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2020.03.011. Epub 2020 Mar 16. PMID: 32387007.

- Ahmad S, Ellis JC, Kamwendo H, Molyneux E. Efficacy and safety of intranasal lorazepam versus intramuscular paraldehyde for protracted convulsions in children: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2006 May 13;367(9522):1591-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68696-0. PMID: 16698412.

- Burman RJ, Ackermann S, Shapson-Coe A, Ndondo A, Buys H, Wilmshurst JM. A Comparison of Parenteral Phenobarbital vs. Parenteral Phenytoin as Second-Line Management for Pediatric Convulsive Status Epilepticus in a Resource-Limited Setting. Front Neurol. 2019 May 15;10:506. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00506. PMID: 31156538; PMCID: PMC6530138.

- Chamberlain JM, Okada P, Holsti M, Mahajan P, Brown KM, Vance C, Gonzalez V, Lichenstein R, Stanley R, Brousseau DC, Grubenhoff J, Zemek R, Johnson DW, Clemons TE, Baren J; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Lorazepam vs diazepam for pediatric status epilepticus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014 Apr 23-30;311(16):1652-60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2625. PMID: 24756515.

- Chamberlain JM, Kapur J, Shinnar S, Elm J, Holsti M, Babcock L, Rogers A, Barsan W, Cloyd J, Lowenstein D, Bleck TP, Conwit R, Meinzer C, Cock H, Fountain NB, Underwood E, Connor JT, Silbergleit R; Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network investigators. Efficacy of levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, and valproate for established status epilepticus by age group (ESETT): a double-blind, responsive-adaptive, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Apr 11;395(10231):1217-1224. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30611-5. Epub 2020 Mar 20. PMID: 32203691; PMCID: PMC7241415.

- Chhabra R, Gupta R, Guptaa LK. Intranasal midazolam versus intravenous benzodiazepines for acute seizure controle in children; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav 2001.125;108390

- Dalziel SR, Borland ML, Furyk J, Bonisch M, Neutze J, Donath S, Francis KL, Sharpe C, Harvey AS, Davidson A, Craig S, Phillips N, George S, Rao A, Cheng N, Zhang M, Kochar A, Brabyn C, Oakley E, Babl FE; PREDICT research network. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children (ConSEPT): an open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 May 25;393(10186):2135-2145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30722-6. Epub 2019 Apr 17. PMID: 31005386.

- Gaínza-Lein, M., Fernández, I. S., Jackson, M., Abend, N. S., Arya, R., Brenton, J. N.,... & Pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group. (2018). Association of time to treatment with short-term outcomes for pediatric patients with refractory convulsive status epilepticus. JAMA neurology, 75(4), 410-418.

- Garbovsky, L. A., Drumheller, B. C., & Perrone, J. (2015). Purple glove syndrome after phenytoin or fosphenytoin administration: review of reported cases and recommendations for prevention. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 11(4), 445-459.

- Holsti, M., Dudley, N., Schunk, J., Adelgais, K., Greenberg, R., Olsen, C.,... & Filloux, F. (2010). Intranasal midazolam vs rectal diazepam for the home treatment of acute seizures in pediatric patients with epilepsy. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 164(8), 747-753.

- Jeannet, P. Y., Roulet, E., Maeder-Ingvar, M., Gehri, M., Jutzi, A., & Deonna, T. (1999). Home and hospital treatment of acute seizures in children with nasal midazolam. European journal of paediatric neurology, 3(2), 73-77.

- Lyttle MD, Rainford NEA, Gamble C, Messahel S, Humphreys A, Hickey H, Woolfall K, Roper L, Noblet J, Lee ED, Potter S, Tate P, Iyer A, Evans V, Appleton RE; Paediatric Emergency Research in the United Kingdom & Ireland (PERUKI) collaborative. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of paediatric convulsive status epilepticus (EcLiPSE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2019 May 25;393(10186):2125-2134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30724-X. Epub 2019 Apr 17. PMID: 31005385; PMCID: PMC6551349.

- Handral A, Veerappa BG, Gowda VK, Shivappa SK, Benakappa N, Benakappa A. Levetiracetam versus Fosphenytoin in Pediatric Convulsive Status Epilepticus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2020 Jul-Sep;15(3):252-256. doi: 10.4103/jpn.JPN_109_19. Epub 2020 Nov 6. PMID: 33531940; PMCID: PMC7847106.

- Malamiri RA, Ghaempanah M, Khosroshahi N, Nikkhah A, Bavarian B, Ashrafi MR. Efficacy and safety of intravenous sodium valproate versus phenobarbital in controlling convulsive status epilepticus and acute prolonged convulsive seizures in children: a randomised trial. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2012 Sep;16(5):536-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2012.01.012. Epub 2012 Feb 11. PMID: 22326977.

- Malu CK, Kahamba DM, Walker TD, Mukampunga C, Musalu EM, Kokolomani J, Mayamba RM, Wilmshurst JM, Dubru JM, Misson JP. Efficacy of sublingual lorazepam versus intrarectal diazepam for prolonged convulsions in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Child Neurol. 2014 Jul;29(7):895-902. doi: 10.1177/0883073813493501. Epub 2013 Jul 31. PMID: 23904337.

- Mindikoglu, A. L., King, D., Magder, L. S., Ozolek, J. A., Mazariegos, G. V., & Shneider, B. L. (2011). Valproic acid-associated acute liver failure in children: case report and analysis of liver transplantation outcomes in the United States. The Journal of pediatrics, 158(5), 802-807.

- Momen AA, Azizi Malamiri R, Nikkhah A, Jafari M, Fayezi A, Riahi K, Maraghi E. Efficacy and safety of intramuscular midazolam versus rectal diazepam in controlling status epilepticus in children. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015 Mar;19(2):149-54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2014.11.007. Epub 2014 Nov 29. PMID: 25500574.

- Mpimbaza A, Ndeezi G, Staedke S, Rosenthal PJ, Byarugaba J. Comparison of buccal midazolam with rectal diazepam in the treatment of prolonged seizures in Ugandan children: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2008 Jan;121(1):e58-64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0930. PMID: 18166545.

- Nalisetty S, Kandasamy S, Sridharan B, Vijayakumar V, Sangaralingam T, Krishnamoorthi N. Clinical Effectiveness of Levetiracetam Compared to Fosphenytoin in the Treatment of Benzodiazepine Refractory Convulsive Status Epilepticus. Indian J Pediatr. 2020 Jul;87(7):512-519. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03221-2. Epub 2020 Feb 22. PMID: 32088913.

- Nazir M, Tarray RA, Asimi R, Syed WA. Comparative Efficacy of IV Phenytoin, IV Valproate, and IV Levetiracetam in Childhood Status Epilepticus. J Epilepsy Res. 2020 Dec 31;10(2):69-73. doi: 10.14581/jer.20011. PMID: 33659198; PMCID: PMC7903044

- Noureen N, Khan S, Khursheed A, Iqbal I, Maryam M, Sharib SM, Maheshwary N. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Injectable Levetiracetam Versus Phenytoin as Second-Line Therapy in the Management of Generalized Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Children: An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Neurol. 2019 Oct;15(4):468-472. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2019.15.4.468. PMID: 31591834; PMCID: PMC6785465.

- Senthilkumar, C. S., P. Selvakumar, and M. Kowsik. "Randomized controlled trial of levetiracetam versus fosphenytoin for convulsive status epilepticus in children." Int J Pediatr Res 5.4 (2018): 237-242.

- Sharma P, Mandot S, Bamnawat S. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in pediatric population: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2019 Mar;6(2):741-745. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20190722

- Silbergleit, R., Durkalski, V., Lowenstein, D., Conwit, R., Pancioli, A., Palesch, Y., & Barsan, W. (2012). Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. New England journal of medicine, 366(7), 591-600.

- Singh K, Aggarwal A, Faridi MMA, Sharma S. IV Levetiracetam versus IV Phenytoin in Childhood Seizures: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2018 Apr-Jun;13(2):158-164. doi: 10.4103/jpn.JPN_126_17. PMID: 30090128; PMCID: PMC6057176.

- Sreenath TG, Gupta P, Sharma KK, Krishnamurthy S. Lorazepam versus diazepam-phenytoin combination in the treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010 Mar;14(2):162-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.02.004. Epub 2009 Mar 18. PMID: 19297221.

- Vignesh V, Rameshkumar R, Mahadevan S. Comparison of Phenytoin, Valproate and Levetiracetam in Pediatric Convulsive Status Epilepticus: A Randomized Double-blind Controlled Clinical Trial. Indian Pediatr. 2020 Mar 15;57(3):222-227. PMID: 32198861.

- Wani G, Imran A, Dhawan N, Gupta A, Giri JI. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin in children with status epilepticus. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019 Oct 31;8(10):3367-3371. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_750_19. PMID: 31742170; PMCID: PMC6857426.

- Welch RD, Nicholas K, Durkalski-Mauldin VL, Lowenstein DH, Conwit R, Mahajan PV, Lewandowski C, Silbergleit R; Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials (NETT) Network Investigators. Intramuscular midazolam versus intravenous lorazepam for the prehospital treatment of status epilepticus in the pediatric population. Epilepsia. 2015 Feb;56(2):254-62. doi: 10.1111/epi.12905. Epub 2015 Jan 17. PMID: 25597369; PMCID: PMC4386287.

- Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liao Q, Liu Z. Preferential Antiseizure Medications in Pediatric Patients with Convulsive Status Epilepticus: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin Drug Investig. 2021 Jan;41(1):1-17. doi: 10.1007/s40261-020-00975-7. Epub 2020 Nov 4. PMID: 33145680.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

| Study reference | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | Intervention (I) | Comparison / control (C)

| Follow-up | Outcome measures and effect size | Comments |

| Zhang, 2021 | SR and network meta-analysis RCTs.

Literature search up to May 2020 (databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library)

Study design: 16 RCTs (n=3397).

A: Lahat, 2000 B: Ahamed, 2006 C: Mpimbaza, 2008 D: Sreenath, 2010 E: Malamiri, 2012 F: Malu, 2013 G: Chamberlain, 2014 H: Momen, 2015 I: Welch, 2015 J: Burman, 2019 K: Dalziel, 2019 – ConSEPT trial L: Lyttle, 2019 - EcLiPSE trial M: Noureen, 2019 N: Chamberlain, 2020 – ESETT trial O: Nalisetty, 2020 P: Vignesh, 2020

Setting and Country: A: Israel B: Malawi C: Uganda D: India E: Iran F: Congo and Rwanda G: USA H: Iran I: USA J: South Africa K: Australia, New Zealand L: UK M: Pakistan N: USA O: India P: India

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial; no conflicts of interest stated. | Inclusion criteria SR: *pediatric patients; * diagnosis of status epilepticus; *RCTs.

Exclusion criteria SR: *mixed population without a pediatric subgroup analysis; *not status epilepticus; *received the study drug prior to admission; *sample size fewer than 30; *not RCTs.

16 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Baseline characteristics not reported for the total groups, only per intervention vs. control.

Groups comparable at baseline? N.R. | A: Midazolam (0.2 mg/kg IN) B: Lorazepam (100 μg/kg IN) C: Diazepam (0.5 mg/kg intrarectally) D: Lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg IV)

E: Valproate (20 mg/kg IV) F: Diazepam (0.1 mg/kg sublingually) G: Diazepam (0.2 mg/kg IV) H: Midazolam (0.3 mg/kg IM) I: Midazolam (10 mg IM) J: Phenobarbital (20 mg/kg IV) K: Phenytoin (20 mg/kg IV or intraosseously) L: Levetiracetam (40 mg/kg IV) M: Levetiracetam (40 mg/kg IV) N: Levetiracetam (60 mg/kg IV)

O: Fosphenytoin (20 mg PE/ kg IV) P: Phenytoin (20 mg/kg IV)

I groups: Number of pt, sex ratio (M:F) A: 21 (13:8) B: 80 (44:36) C: 165 (82:83) D: 90 (55:35) E: 30 (16:14) F: 202 (91:111) G: 162 (87:75) H: 50 (31:19) I: 60 (35:25) J: 52 (26:26) K: 114 (53:61) L: 152 (75:77) M: 300 (216:84) N: 225 (124:101) O: 29 (16:13) P: 35 (19:16)

Age, mean ± SD (range) mo A: 16 (6–38) B: 18.5 (9–33) C: 18.0 (11.5–36.0) D: 84 ± 36.8 E: 5 (3–16) y F: 35.5 (17.8–54) G: 4.9 ± 4.9 y H: 2 ± 1.1 y I: 6.4 ± 4.8 y J: 25.7 (13.1–65.6) K: 4.0 ± 3.9 y L: 2.7 (1.3–5.9) y M: 3.54 ± 0.24 y N: 6.1 ± 4.3 y O: 32.9 ± 37.2 P: 44 ± 43

| A: Diazepam (0.3 mg/kg IV) B: Paraldehyde (0.2 mL/kg IM) C: Midazolam (0.5 mg/kg intrabuccal.) D: Diazepam (0.2 mg/kg IV) à IV phenytoin 18mg/kg E: Phenobarbital (20 mg/kg IV) F: Lorazepam (0.5 mg/kg intrarectally) G: Lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg IV) H: Diazepam (0.5 mg/kg intrarectally) I: Lorazepam (4 mg IV) J: Phenytoin (20 mg/kg IV) K: Levetiracetam (40 mg/kg IV or ntraosseously) L: Phenytoin (20 mg/kg IV) M: Phenytoin (20 mg/kg IV) N: Fosphenytoin (20 mg PE/kg IV) vs. Valproate (40 mg/kg IV) O: Levetiracetam (40 mg/ kg IV) P: Valproate (20 mg/kg IV) vs. Levetiracetam (20 mg/kg IV)

C groups: Number of pt, sex ratio (M:F) A: 23 (12:11) B: 80 (43:37) C: 165 (84:81) D: 88 (47:41) E: 30 (21:9) F: 234 (130:104) G: 148 (68:80) H: 50 (27:23) I: 60 (36:24) J: 59 (32:27) K: 119 (59:60) L: 134 (72:62) M: 300 (190:110) N: unclear O: 32 (16:16) P: 35 (21:14) vs. 32 (18:14)

Age, mean ± SD (range) mo A: 18 (6–40) B: 19.0 (10.5-36) C: 17.0 (10.5–30.0) D: 78.7 ± 32.5 E: 4 (3–11) y F: 35.5 (19–60) G: 4.8 ± 4.6 y H: 2.5 ± 1.4 y I: 6.9 ± 4.6 y J: 22.2 (14.8–46.3) K: 3.8 ± 3.8 y L: 2.7 (1.6–5.6) y M: 3.46 ± 0.22 y N: unclear O: 29.4 ± 31.2 P: 59 ± 44 vs. 58 ± 50 | End-point of follow-up: N.R.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N.R.

| Outcome measure 1: Seizure cessation (critical) First-line: The point estimates of seizure cessation midazolam (49%), diazepam (31%), lorazepam (14%), and paraldehyde (5%). Random effects model, Odds ratio:

Second-line: The point estimates of seizure cessation phenobarbital (39%), levetiracetam (31%), valproate (17%), phenytoin (6%), and fosphenytoin (6%). Random effects model, Odds ratio:

Outcome measure 2: termination of SE after drug administration (critical) N.R.

Outcome measure 3: mortality (important) N.R.

Outcome measure 4: requirement for ventilatory support (important) First-line: RDdiazepam-midazolam: 0.07, 95%CI -0.12 to 0.32 RDlorazepam-midazolam: 0.06, 95%CI -0.14 to 0.29

Second-line: RDlevetiracetam-valproate: -0.01, 95%CI -0.30 to 0.48 RDphenobarbital-valproate: 0.06, 95%CI -0.17 to 0.53 RDphenytoin-valproate: 0.11, 95%CI -0.25 to 0.53 RDfosphenytoin-valproate: 0.18, 95%CI -0.11 to 0.89

Outcome measure 5: hypotension (important) N.R.

Outcome measure 6: Length of hospital stay (important) Admission to the ICU, second line: RDlevetiracetam-valproate: 0.40, 95%CI -0.03 to 0.66 RDphenobarbital-valproate: 0.56, 95%CI 0.05 to 0.89 RDphenytoin-valproate: 0.29, 95%CI -0.12 to 0.55 RDfosphenytoin-valproate: 0.20 95%CI -0.18 to 0.55

| Facultative: * Midazolam could be a better option for first-line treatment. Phenobarbital, levetiracetam, and valproate had their respective superiority in the second-line intervention. * Best ranked first-line ASMs was midazolam, which had superiority to both primary and secondary outcomes (seizure cessation, recurrence, and respiratory depression). * Diazepam was more frequently used in the emergency room. * Phenobarbital ranked best among second-line ASMs for seizure cessation and admission to the ICU. * Valproate had superiority with respect to preventing recurrence within 24 h and had an equally lower risk in respiratory depression compared with levetiracetam.

Personal remarks: * Sample size in half of the included studies was small. *Clinical heterogeneity in age, etiology, and admission interval may also cause potential biases.

Level of evidence: low to very low.

Risk of Bias: Randomization process: 5 / 16 deviations from intended interventions: 7 /16 Missing outcome data: 1 / 16 Measurement bias: 6 / 16 Selection bias: 13 /16 (some concern) Overall: 10 / 16

Sensitivity analyses: not performed.

Statistical heterogeneity: No evidence of heterogeneity was found (I2<25%, p>0.05). Clinical heterogeneity: age, etiology, and admission interval may cause potential biases.

|

Abdelgadir, 2020.

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) | SR and meta-analysis of RCTs.

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (1946–April 2020), Embase (1974–April 2020), CINAHL (1982–April 2020), CENTRAL (issue 4, 2020).

Study design: 10 RCTs (n=1907).

A: Chamberlain, 2020 - ESETT trial B: Dalziel, 2019 - ConSEPT trial C: Lyttle, 2019 - EcLiPSE trial D: Nalisetty, 2020 E: Noureen, 2019 F: Senthil Kumar, 2018 G: Sharma, 2019 H: Singh, 2018 I: Vignesh, 2020 J: Wani, 2019

Setting and Country: A: USA B: Australia, New Zealand C: UK D: India E: Pakistan F: India G: India H: India I: India J: India

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Authors have not declared a specific grant. Competing interests are not declared. | Inclusion criteria SR: *RCTs. *Patients aged 1mo–18y. *Comparison intravenous levetiracetam with any other treatment for CSE. *Outcome: clinical cessation of seizure activities. *No language restriction.

Exclusion criteria SR: N.R.

10 RCTs included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients A: LEV (n=85), FOS (n=71), VAL (n=69) B: LEV (n=119), PHEN (n=114) C: LEV (n=152), PHEN (n=134) D: FOS (n=29), LEV (n=32) E: LEV (n=300), PHEN (n=300) F: LEV (n=25), FOS (n=25) G: LEV (n=125), PHEN (n=125) H: LEV (n=50), PHEN (n=50) I: PHEN (n=35), LEV (n=32), VAL (n=35) J: LEV (n=52), PHEN (n=52)

Age group A: 2 - 18y B: 3mo - 16y C: 6mo - 18y D: 2mo - 18y E: 1 - 14y F: 3mo - 12y G: 6mo - 18y H: 3 - 12y I: 3mo - 12y J: 1mo - 12y

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. | A: 60 mg/kg levetiracetam (max 4.5 g)

B: 40 mg/kg levetiracetam over 5 min C: 40 mg/kg levetiracetam over 5 min D: fosphenytoin 20 mg/kg over 10 min (max 1 gram) E: 40 mg/kg levetiracetam over 15 min F: fosphenytoin 20 mg/kg of G: 20 mg/kg levetiracetam H: 30 mg/kg at 5 mg/kg/min levetiracetam I: 20 mg/kg over 20 min of either phenytoin, levetiracetam or valproate J: levetiracetam 40 mg/kg over 10 min | A: fosphenytoin 20 mg/kg (max 1.5 g) vs. valproate 40 mg/kg (max 3 g) over 10 min B: phenytoin 20 mg/kg over 20 min

C: phenytoin 20 mg/kg over 20 min

D: levetiracetam 40 mg/kg (max 3 grams) over 10 min E: 20 mg/kg phenytoin over 30 min F: levetiracetam 30 mg/kg over 7 min G: phenytoin 20 mg/kg H: 20 mg/kg phenytoin at 1 mg/kg/ minute I: 20 mg/kg over 20 min of either phenytoin, levetiracetam or valproate J: phenytoin 20 mg/kg over 20 min

| End-point of follow-up: N.R.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N.R.

| Outcome measure 1: Seizure cessation (critical) See Zhang (2021)

Outcome measure 2: termination of SE after drug administration (critical) Timing of cessation of seizure activities levetiracetam: 378 minutes phenytoin: 376 minutes Mean difference: -0.45 minutes (95%CI −1.83 to 0.93; I2=87%).

levetiracetam: 57 minutes fosphenytoin: 54 minutes Mean difference of -0.70 minutes (95%CI −4.26 to 2.86; I2=79%).

Outcome measure 3: mortality (important) levetiracetam: 1/302 patients (1%) phenytoin: 2/283 patients (1%) RR: 0.57 (95%CI 0.07 to 4.62, p=0.64 I2=0 %), favouring levetiracetam.

levetiracetam: 1/117 patients (1%) valproate: 2/104 patients (2%) RR: 0.57 (95%CI 0.07 to 4.59, p=0.71 I2=0 %), favouring levetiracetam.

Outcome measure 4: requirement for ventilatory support (important) N.R.

Outcome measure 5: hypotension (important) N.R.

Outcome measure 6: Length of hospital stay (important) See Zhang (2021)

| Facultative: Levetiracetam is comparable to phenytoin, fosphenytoin and valproate as a second line treatment of paediatric CSE.

Personal remarks: * modest sample sizes of some of the included RCTs. * Moderate heterogeneity was identified due to some differences in study designs (e.g. different drugs used, dosages and infusion rates). *Various dosages and infusion manners are included in the analyses.

Level of evidence: moderate (due to inconsistency and heterogeneity of the studies and the small sample size).