Keuze van procedure en timing bij specifieke patiëntengroepen

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale methode voor het inbrengen van een gastrostomiekatheter?

Deze uitgangsvraag bevat de volgende onderliggende vragen:

- Wat is de optimale methode voor het inbrengen van een gastrostomiekatheter bij patiënten met hoofd-halskanker?

- Wat is de optimale methode voor het inbrengen van een gastrostomiekatheter bij patiënten met neuromusculaire aandoeningen?

- Wat is de optimale methode voor het inbrengen van een gastrostomiekatheter bij patiënten met slikstoornissen?

Aanbeveling

Gastrostomie

- Kies voor gastrostomie indien > 30 dagen enterale voeding nodig is en de levensverwachting van de patiënt langer dan een maand is.

- Stel plaatsing uit bij ernstig zieke patiënten in een slechte conditie, omdat het risico op ernstige complicaties en zelfs overlijden te hoog is. Overbrug ten minste vier weken met nasogastrische of nasoduodenale sonde om het beloop van de ziekte en de prognose van de patiënt te evalueren.

- Overweeg bij neuromusculaire patiënten juist vroege gastrostomiekatheter plaatsing om in zo goed mogelijke conditie de plaatsing hiervan mogelijk te maken. In deze patiënten wordt een directe gastrostomie-plaatsing zonder voorafgaande neussonde geadviseerd.

PEG-plaatsing

- Overweeg PEG-plaatsing middels de pull-techniek of PRG plaatsing als eerste keuze voor langdurig toedienen van sondevoeding (> 30 dagen).

- Kies voor PRG of PEG-plaatsing middels de push-techniek bij patiënten met orofaryngeale, laryngeale en hypofaryngeale tumoren en patiënten met oesofagus stenose.

- Kies voor PRG-plaatsing bij patiënten met neuromusculaire aandoeningen die beademd worden of bij wie sedatie niet mogelijk is.

- Kies voor chirurgische gastrostomie of een gecombineerde (endoscopisch geassisteerde) procedure bij patiënten waarbij gelijktijdig een andere operatie wordt uitgevoerd en wanneer een normale PEG of PRG niet kan worden geplaatst bij bijvoorbeeld voorliggend colon/ontbreken van diafanie.

- De keuze voor een modaliteit moet eveneens gebaseerd worden op lokale faciliteiten en expertise.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de geïncludeerde studies zijn we onzeker over het effect van PEG versus chirurgische gastrostomie en PRG versus chirurgische gastrostomie op de cruciale uitkomstmaat mortaliteit. De bewijskracht van de resultaten is erg beperkt vanwege het risico op bias in de geïncludeerde studies en de (erg) lage aantallen. De overall bewijskracht voor deze module is dan ook zeer laag (zeer laag GRADE). Er is dus duidelijk sprake van een kennislacune.

Voor de patiëntengroep met slikstoornissen, werden geen geschikte studies gevonden. Ook werden er geen studies gevonden die PEG of PRG vergeleken met chirurgische gastrostomie in patiënten met motorneuronziekten. Voor de groep patiënten met diverse ziekten werden geen studies gevonden die PRG vergeleken met chirurgische gastrostomie. Er is voornamelijk veel retrospectief onderzoek verricht. De verwachting is ook dat er weinig tot geen prospectieve of gerandomiseerde studies verricht zullen worden op dit thema.

Aanvullende argumenten

In de praktijk wordt weinig gebruik gemaakt van chirurgische gastrostomie; chirurgische plaatsing is vaak niet de eerste keuze vanwege onder andere het hogere risico op complicaties, de grotere complexiteit, de hogere kosten en omdat het meer belastend is voor de patiënt. Vaak wordt hier alleen voor gekozen als de plaatsing van de gastrostomie gecombineerd kan worden met een andere chirurgische ingreep. Daarnaast wordt er soms gekozen voor een endoscopisch geassisteerde chirurgische gastrostomie.

Zowel PEG als PRG worden veel gebruikt. De vergelijking tussen PEG en PRG voor de verschillende subgroepen is met name gebaseerd op retrospectieve studies, waarbij er sprake is van een zeer lage bewijskracht. De voorkeur voor een van beide technieken (PEG versus PRG) wordt vaak bepaald door de lokale ervaring en voorkeur van elk ziekenhuis. Procedure gerelateerde en 30-dagen mortaliteit, evenals infectieuze complicaties, lijken vergelijkbaar tussen beide groepen in deze retrospectieve studies. Sonde gerelateerde complicaties (dislocatie, obstructie, en defecten aan de sonde) lijken beduidend hoger na PRG plaatsing (rond 2 tot 3% bij PEG versus 25% bij PRG, binnen 30 dagen). In patiënten met hoofd-hals carcinoom was er een lagere procedure gerelateerde mortaliteit en minder sonde gerelateerde complicaties na PEG plaatsing. Bij motorneuronziekte patiënten werd geen verschil gezien tussen PEG en PRG. Er dient opgemerkt te worden dat dit retrospectieve studies betreffen zoals genoemd in de literatuuranalyse. Vanwege het retrospectieve karakter is de bewijskracht laag. Echter, gezien de werkgroep van mening is dat deze resultaten overeen komen met de praktijkervaring, worden deze getallen wel klinisch relevant geacht in het maken van een keuze voor PEG of PRG. Praktische argumenten, zoals het percentage succesvolle plaatsingen (dit lijkt in één studie hoger bij PRG (97,1% versus 91,2%) dan bij PEG (Strijbos, 2018), en pijnklachten (door de manier van plaatsing (met hechtingen door de buikwand) lijkt een PRG meer pijnklachten te geven dan PEG) kunnen ook meegenomen worden in deze besluitvorming.

Late complicaties (optredend > 30 dagen) kunnen in de praktijk ook een belangrijke rol spelen in de keuze tussen PEG en PRG. Het belangrijkste verschil tussen PEG en PRG is het grote aantal ‘tube failure’ (dislocatie of obstructie) dat we zien optreden. Ongeveer 25% van de PRG sondes valt uit of disloceert (Strijbos, 2018 en Strijbos, 2019). Daarnaast is het nodig om deze regelmatig te vervangen, waarbij de termijn afhankelijk is van de adviezen van de fabrikant. In de praktijk zien we dat dit meestal tussen 3 en 6 maanden ligt, zie module Organisatie van zorg - nazorg. Bij PEG ligt het percentage uitval/dislocatie rond de 5 en 7% (met name bij de PEG-J, bij reguliere PEG ligt dit aantal nog veel lager). In onze optiek is PEG voor veel patiënten om deze reden een betere keuze, indien allereerst de bovenstaande andere overwegingen zijn meegenomen in de beslissing.

Laryngospasme

Er is geen literatuur beschikbaar over het optreden van laryngospasmen bij het plaatsen van een PEG-sonde. Het optreden van laryngospasmen bij het plaatsen van een PEG-sonde kan de plaatsing onmogelijk maken. Dit fenomeen is echter zeer zeldzaam. Er hoeven derhalve geen extra of aanvullende maatregelen te worden toegepast anders niet dan de standaard organisatie van zorg.

Subgroepen

Indien beschikbaar en geplaatst in zorgvuldig geselecteerde patiënten, lijkt PEG de voorkeur te hebben boven PRG vanwege een lager aantal complicaties. Bij geselecteerde patiënten lijkt PRG een waardevol alternatief. Allereerst is dit te overwegen bij patiënten bij wie sedatie niet mogelijk is. Daarnaast worden hieronder per subgroep overwegingen genoemd in de keuze voor een PEG of een PRG. De keuze voor PEG of PRG zou echter eveneens gebaseerd moeten worden op lokale faciliteiten en expertise.

Hoofd- halskanker

In geval van orofaryngeale tumoren of stenose kan een PRG verricht worden gezien hierbij slechts een dunne sonde/voerdraad door de slokdarm geplaatst wordt. In deze gevallen, indien passage met endoscoop mogelijk is, zou ook een push-PEG plaatsing verricht kunnen worden. De reden om niet voor een reguliere (pull-) PEG te kiezen bij patiënten met orofaryngeale tumoren is het risico op een ernstige complicatie, namelijk entmetastasen. Dit wordt ook wel ‘tumor seeding’ genoemd. Er is geen onomstotelijk bewijs dat het risico hierop verhoogd is bij plaatsing middels de pull-techniek. Echter, literatuurstudie toont 49 case reports van entmetastasen na pull-PEG plaatsing, en slechts een case na PRG plaatsing (Hawken, 2005; Sinapi, 2013; Coletti, 2006 en Zhang, 2014). De studie van Strijbos (2018) beschrijft daarnaast nog 1 casus na PRG plaatsing. Een studie (Ellrichmann, 2013) toonde een percentage van 9.4% entmetastasen na pull-PEG bij patiënten met plaveiselcelcarcinoom van de slokdarm.

Er zijn verschillende theorieën over het ontstaan van deze metastasen, waarbij de eerste gebaseerd is op iatrogene verspreiding van tumorcellen doordat de flens van de PEG langs de tumor wordt getrokken. Ten tweede wordt uitgegaan van lymfogene/hematogene verspreiding (gezien hoge incidentie van gelijktijdige metastasen op andere locaties). Als laatste wordt het verspreiden van tumor cellen door loslating gezien als een mogelijke oorzaak. De cellen worden meegevoerd tijdens het doorslikken van bijvoorbeeld speeksel, met nadien hechting aan een wondoppervlak (in dit geval de insteekopening). Al met al neigt de literatuur naar een hoger risico op entmetastasen bij pull-techniek. Om deze reden raden we aan in deze specifieke gevallen te kiezen voor PRG of push-PEG.

Slikstoornissen

In geval van slikstoornissen door een neurologische oorzaak (herseninfarct, hersenbloeding, neuro-degeneratieve ziekten (bijvoorbeeld Parkinson, MSA, PSP) spierziekten) zonder respiratoire problemen (beademing, beperkte respiratoire reserve, laryngospasmen) heeft PEG plaatsing de voorkeur boven PRG vanwege lager aantal complicaties. In aanwezigheid van respiratoire problemen heeft PRG plaatsing de voorkeur boven PEG: in geval van (nachtelijke) ademhalingsondersteuning wordt de PRG plaatsing met ademhalingsondersteuning uitgevoerd (met nadien observatie op IC), in geval van laryngospasmen wordt geadviseerd om de PRG plaatsing zonder sondeplaatsing te verrichten. In geval van beperkte respiratoire reserve dient in goed overleg met longarts (bij voorkeur van centrum voor thuisbeademing (CTB)) een plan op maat gemaakt te worden.

Neuromusculaire aandoeningen

Bij voldoende respiratoire reserve heeft PEG plaatsing lichtelijk de voorkeur boven PRG plaatsing. Een en ander hangt echter ook sterk af van de lokale expertise. Lees hiervoor ook de Module Organisatie van zorg. In aanwezigheid van respiratoire problemen heeft PRG plaatsing de voorkeur boven PEG: in geval van (nachtelijke) ademhalingsondersteuning wordt de PRG plaatsing met ademhalingsondersteuning uitgevoerd (met nadien observatie op IC). In geval van laryngospasmen, welke zeldzaam zijn, wordt geadviseerd PRG plaatsing zonder sondeplaatsing te verrichten. In geval van beperkte respiratoire reserve dient in goed overleg met een longarts (bij voorkeur van CTB) een plan op maat gemaakt te worden.

Ethische aspecten

Ethische aspecten dienen meegenomen te worden in de overwegingen. De commissie adviseert dit over te laten aan het inzicht van de verwijzer, waarbij afgewogen dient te worden of het risico van de procedure opweegt tegen de voordelen van een gastrostomiekatheter plaatsing. Hierbij adviseren we om de huisarts en/of een palliatief team/ verpleegkundige te betrekken.

Palliatieve fase

De richtlijn ‘palliatieve zorg’ adviseert sondevoeding alleen te starten indien voldaan wordt aan de volgende voorwaarden: een Karnofsky Performance status van > 50% en een geschatte levensverwachting van minstens 2 tot 3 maanden (Oncoline, 2014). De werkgroep raadt aan om sondevoeding (en dus het eventueel plaatsen van een gastrostomiekatheter) alleen te starten bij patiënten met een levensverwachting van meer dan één maand, in navolging van de ESPEN guideline (Bischoff, 2020). De Karnofsky Performance status is niet toepasbaar bij mensen met neuromusculaire aandoeningen.

Timing van de procedure

In een Nederlandse studie (Strijbos, 2018) vond men een relatief hoge 30-dagen mortaliteit bij zowel PEG als PRG plaatsingen (respectievelijk 10,7% versus 5,1%), gerelateerd aan de onderliggende ziekte. Dit impliceert dat het plaatsen van een gastrostomiekatheter bij ernstig zieke patiënten in een slechte conditie uitgesteld zou moeten worden, omdat het risico op ernstige complicaties en zelfs overlijden hoog is. Uit onze praktijkervaring blijkt ook dat vaak al in een vroeg stadium (met name na bijvoorbeeld ernstig CVA) een verzoek tot PEG plaatsing bestaat. Een alternatief is nasogastrisch of nasojejunaal voeden gedurende enkele weken, om het beloop van de ziekte en de prognose van de patiënt te evalueren.

Literatuur over timing bij neuromusculaire aandoeningen gaat over het algemeen vooral over amyotrofische lateraalsclerose (ALS) patiënten. De commissie is uitgegaan van het principe dat het risico van deze specifieke patiënten te extrapoleren valt naar andere neuromusculaire aandoeningen. Daarbij is de expert opinion dat plaatsing in een vroeg stadium van de ziekte aan te raden is. Allereerst omdat het stabiliseren van gewicht belangrijk is voor spierkracht en daarmee een langere overleving (Burgos, 2018). Daarnaast is bij vroege plaatsing de conditie van de patiënt beter, met minder risico’s tijdens plaatsing van de gastrostomiekatheter. Daarbij is er over het algemeen een indicatie voor levenslange gastrostomie en heeft een tijdelijke neussonde gedurende enkele weken om die reden geen meerwaarde. Dit advies komt ook voort uit de nieuwste Europese richtlijn (ESGE), waarin vroege plaatsing wordt aangeraden zodra gewichtsverlies optreedt ondanks bijvoeding (Arvanitakis, 2021; Gkolfakis, 2021). Een meta-analyse en recente cohortstudie onderschrijven deze mening (Cui, 2018; Bond, 2019).

Daarbij speelt de respiratoire functie een belangrijke rol als het gaat om de techniek en mogelijkheid van sedatie tijdens gastrostomiekatheter plaatsing. Hierop wordt in een specifieke module ingegaan (zie Module Sedatie bij neuromusculaire aandoeningen).

Bij patiënten met hoofd-halskanker is er discussie over timing van gastrostomie: dient er een profylactische plaatsing bij alle patiënten uitgevoerd te worden of reactieve plaatsing bij complicaties van de behandeling, zoals secundaire dysfagie ten gevolg van mucositis. Bij een recente enquête onder 8 behandelcentra in Nederland komt dat duidelijk naar voren: 4 centra plaatsen profylactisch en 4 centra reactief een PEG (nog niet gepubliceerde data). Tot wel 75% van de hoofdhals-patiënten die gecombineerde chemoradiotherapie (CCRT) krijgen ontwikkeld dysfagie (Baschnagel, 2013; Caudell, 2009; Caudell, 2010; Vlacich, 2014; Logemann, 2008; Eisbruch, 2011; Feng, 2010; Roe, 2010; Kraaijenga, 2014; Hunter, 2014; Van der Molen, 2011). Het voordeel van profylactische plaatsing is een lagere kans op ondervoeding en dehydratie (Mekhail, 2001; Langmore, 2011). Echter het niet gebruiken van de slikspieren blijkt nadelig, omdat er daardoor ook vaak chronische slikproblemen zijn (Hutcheson, 2013; Pohar, 2015; Ward, 2016; Langmore, 2015) en patienten hierdoor sonde-afhankelijk worden (Logemann, 2008; Goguen, 2006; Morton, 2009; van der Molen, 2014; Ackerstaff, 2012). Daarnaast blijkt met regelmaat achteraf niet iedere patiënt een PEG nodig gehad te hebben en is dan wel blootgesteld geweest aan de risico’s van deze invasieve procedure.

Anderzijds leidt het reactief plaatsen vaker tot ondervoeding en is er meer kans op dehydratie (Silander, 2012). Het enige artikel dat als basis gebruikt kon worden in een recente Cochrane review blijkt een studie die voortijdig afgebroken werd vanwege een gebrek aan inclusie (Corry, 2008).

Een neusmaagsonde zou nog als minder invasieve techniek gebruikt kunnen worden om tijdelijk sondevoeding te geven. Echter ook hierover ontbreekt gedegen vergelijkend onderzoek.

De Europese richtlijn (ESGE) (Arvanitakis, 2021; Gkolfakis, 2021) adviseert profylactische plaatsing van push-PEG bij patiënten met hoofdhalskanker die chemoradiatie ondergaan, als sprake is van risicofactoren (gewichtsverlies, hogere leeftijd, hoge stralingsdosis, en nasofaryngeale/hypofaryngeale tumoren). Het bewijs hiervoor is echter van lage kwaliteit en de aanbeveling zwak. In feite zou dan afhankelijk van de lokale expertise ook een PRG geplaatst kunnen worden.

De werkgroep is van mening dat er geen strikte aanbeveling gedaan kan worden op basis van de huidige literatuur en dat lokale expertise, gewoonte, beschikbaarheid en ook logistiek (kort interval tussen indicatiestelling gastrostomiekatheter en daadwerkelijke plaatsing) een rol dienen te spelen.

Het dient nog onderstreept te worden dat voeding via een gastrostomie (PULL/PUSH-PEG, PRG) als bijvoeding dient. Afhankelijk van wat een patiënt wel nog veilig kan eten en drinken wordt er bepaald wat er nog normaal gebruikt kan worden.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

De belangrijkste doelen van de interventie zijn afhankelijk van de indicatie voor gastrostomie, maar betreffen in de meeste gevallen adequate voeding via de gastrostomie. Het geeft patiënten en hun families vaak rust om te weten dat de patiënt voldoende gevoed wordt. Er zijn verschillende patiëntfactoren die de methode van plaatsing mede bepalen. De voordelen van een gastrostomie vergeleken met een nasogastrische (of nasoduodenale) sonde zijn dat deze langdurig gebruikt kan worden, er minder klachten in het neus-keel gebied zijn en cosmetisch voordeliger wordt gevonden door de meeste patiënten (door het dragen onder de kleding in plaats van via de neus). Het belangrijkste eindpunt betreffende de keuze van een gastrostomie zijn complicaties, met procedure gerelateerde mortaliteit als voornaamste. Andere complicaties die meewegen in de keuze, zijn sonde gerelateerde complicaties zoals dislocatie met noodzaak tot vervanging. Ook kan de keuze tussen narcose (zoals bij chirurgische plaatsing), sedatie of geen van beiden meespelen. Deze keuze zal met name een rol spelen bij patiënten met pulmonale belasting. Patiënten ervaren een endoscopie vaak als belastend. Zo moeten ze bijvoorbeeld nuchter zijn, het kan leiden tot kokhalzen en ze hebben het gevoel dat ze niet kunnen ademen. Echter met sedatie is een PEG een procedure die maximaal 10 minuten duurt. Het is belangrijk om de beschikbare methodes en de risico’s en voor- en nadelen hiervan met de patiënten en eventueel hun familie te bespreken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van een PEG of PRG worden vooral bepaald door het wel of niet opnemen van de patiënt rond de procedure. Het blijkt bij navragen binnen de commissie dat er een grote praktijkvariatie bestaat: van dagbehandeling tot nacht observatie om ook de nazorg verder te stroomlijnen. De technische plaatsing zelf is ongeveer even duur in geval van PEG en PRG.

Een chirurgische gastrostomie brengt meer kosten met zich mee dan een PEG of PRG vanwege alle bijkomende zorgproducten (gebruik operatiekamer, anesthesie).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In feite moet iedere MDL-arts een PEG-sonde kunnen plaatsen en verwijderen. Er is echter wel een verschil in expertise. Daarnaast neemt de ervaring per arts af omdat het aantal MDL-artsen toegenomen is, maar het aantal patiënten met een indicatie voor een PEG niet. Het aantal procedures per MDL-arts is derhalve afgenomen. Er dient daarom overwogen te worden om PEG-sondes door een beperkt aantal MDL-artsen per afdeling te laten verrichten. Ook een PRG vergt specifieke expertise. Vaak wordt deze techniek door interventieradiologen toegepast. Er zijn opvallende lokale verschillen tussen ziekenhuizen als het gaat om de beschikbaarheid van PRG, maar ook in de keus om een PRG dan wel PEG te plaatsen bij specifieke indicaties.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er bestaat een indicatie voor een gastrostomiekatheter indien > 30 dagen sondevoeding nodig is. Sondevoeding wordt namelijk alleen aangeraden bij patiënten met een levensverwachting van meer dan één maand. Bij patiënten in slechte conditie is de kans op complicaties groter, daarbij blijft prognose van deze patiënten lastig in te schatten. Op basis van hoge 30 dagen mortaliteit in meerdere studies, soms tot 10% gerelateerd aan onderliggende ziekte, bevelen we sterk aan de indicatie voor een gastrostomiekatheter beter te overwegen en de selectie van patiënten strikter te maken. Het advies voor deze patiënten is dan ook om een periode van 4 weken te overbruggen met nasogastrische sonde, en na deze periode opnieuw de conditie en prognose van patiënt in te schatten.

PEG of PRG is de eerste keuze indien er een indicatie bestaat voor > 30 dagen sondevoeding. Vanwege een mogelijk hoger risico op entmetastasen bij pull-PEG, adviseert de werkgroep een PRG of push-PEG te plaatsen bij patiënten met orofaryngeale, laryngeale en hypopharyngeale tumoren. In geval van een stenose die niet met een diagnostische gastroscoop te passeren is, dient er altijd een andere techniek dan de pull-PEG gekozen te worden, aangezien het interne plaatje de stenose dan ook niet kan passeren. In dat geval kan er een push-PEG onder endoscopische controle van een kinder-gastroscoop (oraal of nasaal ingebracht) dan wel een PRG verricht worden. Bij patiënten waarbij geen sedatie wenselijk is, bijvoorbeeld bij patiënten met neuromusculaire aandoeningen die beademd worden, adviseert de werkgroep eveneens de plaatsing van een PRG. Chirurgie is de laatste optie, de werkgroep adviseert dit alleen te verrichten indien dit gelijktijdig met een al geplande operatie uitgevoerd kan worden (eventueel gecombineerd, endoscopisch geassisteerd).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De optimale techniek voor langdurige enterale voeding is nog niet goed vastgesteld. Zowel percutane endoscopische gastrostomie (PEG) als percutane radiologische gastrostomie (PRG) zijn veelgebruikte technieken. Complicaties en mortaliteit van beide technieken zijn eerder gemeld, maar de technieken zijn niet goed vergeleken met elkaar. Er is tot nu toe geen consensus bereikt over welke techniek gunstiger is voor verschillende patiëntengroepen.

Het doel van deze module was om de resultaten te specificeren voor verschillende patiëntengroepen (hoofd-halskanker, neuromusculaire aandoeningen en slikstoornissen). Echter, bij gebrek aan gegevens over deze specifieke patiëntengroepen, hebben we besloten eerst studies te beschrijven die wel de patiëntengroepen omvatten, maar geen subgroepanalyses rapporteerden. Deze studies omvatten een verscheidenheid aan patiëntengroepen. Vervolgens hebben we studies met de volgende patiëntengroepen geanalyseerd: patiënten met 1) hoofd-halskanker, 2) neuromusculaire aandoeningen en 3) slikstoornissen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Patients with various diseases

Mortality

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether PEG differed from PRG or surgical gastrostomy with regard to procedure related mortality in patients with various diseases. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Bailey, 1992; Edelman 1998; Ho, 1999; Bankhead, 2005; Ljungdahl, 2006; Oliveira, 2016; Strijbos, 2018; Vidhya, 2018; Cherian, 2019; Strijbos, 2019) |

Peristomal infection

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether PEG differed from PRG or surgical gastrostomy with regard to peristomal infection in patients with various diseases. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Edelman 1998; Ho, 1999; Ljungdahl, 2006; Oliveira, 2016; Strijbos, 2018; Vidhya, 2018; Park, 2019; Strijbos, 2019) |

Systemic infection

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether PEG differed from PRG with regard to systemic infection in patients with various diseases. For PEG versus surgical gastrostomy, number of events was too few to draw a conclusion on the risk on systemic infection. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Ho, 1999; Ljungdahl, 2006; Oliveira, 2016; Strijbos, 2018; Vidhya, 2018; Park, 2019; Strijbos, 2019) |

Pain

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether PEG and PRG differed with regard to pain in patients with various diseases. None of the included studies reported on pain for the comparison PEG versus surgical gastrostomy. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Park, 2019; Strijbos, 2019) |

Leakage

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether PEG differed from PRG or surgical gastrostomy with regard to leakage in patients with various diseases. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Edelman 1998; Ho, 1999; Ljungdahl, 2006; Oliveira, 2016; Strijbos, 2018; Park, 2019) |

Tube failure

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether PEG differed from PRG or surgical gastrostomy with regard to tube failure in patients with various diseases. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Ho, 1999; Ljungdahl, 2006; Oliveira, 2016; Strijbos, 2018; Vidhya, 2018; Park, 2019; Strijbos, 2019) |

Patients with head and neck cancer

Mortality/systemic infection/tube failure

|

- GRADE |

Number of events was too few to draw a conclusion on the risk on procedure related mortality, systemic infection or tube failure due to PEG, PRG or surgical gastrostomy in patients with head and neck cancer.

Sources: (Strijbos, 2018; Rustom, 2008) |

Peristomal infection

|

- GRADE |

Number of events was too few to draw a conclusion on the risk on peristomal infection due to PEG versus PRG in patients with head and neck cancer. None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Strijbos, 2018) |

Pain

|

- GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure pain. |

Leakage

|

Very low GRADE |

When compared to each other, it is unclear whether PEG, PRG or surgical gastrostomy differed with regard to tube leakage in patients with head and neck cancer.

Sources: (Strijbos, 2018; Rustom, 2008; Bailey, 1992) |

Patients with motor neuron diseases

Mortality/systemic infection/tube failure

|

- GRADE |

Number of events was too few to draw a conclusion on the risk on procedure related mortality, systemic infection or tube failure due to PEG versus PRG in patients with motor neuron disease. None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Strijbos, 2018) |

Peristomal infection

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether PEG versus PRG differed with regard to peristomal infection in patients with motor neuron disease. None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Sources: (Strijbos, 2018) |

Pain/leakage

|

- GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures pain and leakage. |

Patients with swallowing disorders

Mortality, peristomal infection, systemic infection, pain, leakage and tube failure

|

- GRADE |

No study could be included on the comparison between PEG, PRG and surgical gastrostomies in patients with swallowing disorders. Therefore it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the effect of those different techniques on all of the outcome measures. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Submodule 1 various patient groups

Ten studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Strijbos, 2018; Strijbos, 2019; Vidhya, 2018; Ljungdahl, 2006; Bankhead, 2005; Oliveira, 2016; Edelman, 1998; Ho, 1999; Park, 2019 and Cherian, 2019).

Description of studies

Strijbos (2018) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the outcomes of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) versus percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy (PRG). They searched Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane and DARE databases until May 2017. ROBINS-I and NOS scales were used for quality assessment. There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies. 16 observational studies were included. Those studies reported on 934 initial PEGs (placed using the pull method) and 1093 initial PRGs. Main outcomes were infectious and tube-related complications within 30 days, procedure related mortality and 30-day mortality. Seven studies were included in the analysis on patients with various diseases (Silas, 2005; Laasch, 2003; Möller, 2009; La Nauze, 2012; Laskaratos, 2013; Galaski, 2009 and Elliot, 1996; N=not reported). Study characteristics of the included studies on various patients groups are depicted in Table 2.1.

Strijbos (2019) performed a retrospective cohort study on the early and late complications of PEG versus PRG. 760 patients with successful PEG/PEG-J or PRG insertion in a tertiary referral center in the Netherlands were included in the study. 291 patients underwent PEG and 469 underwent PRG. PEG was performed according to the standard Pull-method. PRG was performed using a Wills-Oglesby Percutaneous Gastrostomy set. Standard antibiotic prophylaxis was not given. Mean age (SD) at baseline was 62,4±14,9 years in the PRG group and 63,4±11,0 years in the PEG group. Of the patients in the PRG group 65% were men versus 59.5% in the PEG group. Indication for tube insertion was amongst others ALS (PRG: 9.8%, PEG: 2.7%), head and neck cancer (PRG: 69.9%, PEG: 38.8%), other malignancy (PRG: 3.8%, PEG: 7.2%) and neurological disease (PRG: 2.7%, PEG: 14%).

Vidhya (2018) performed a retrospective cohort study on the complications of RIG versus PEG. 137 patients undergoing initial PEG and RIG insertion at a tertiary health institution in Australia were included. 85 patients underwent PEG and 52 underwent RIG. PEG was placed using a pull through technique. RIG insertions were performed with an 18F balloon tipped Cook Medical Gastrostomy Tube. Preoperative antibiotics (2G IV Cephazolin) prior to PEG was recommended. There are no guidelines regarding antibiotic administration prior to RIG. Median age at baseline was 64 years in the RIG group and 65 years in the PEG group. Of the patients in the RIG group 65.4% were men versus 63.5% in the PEG group. Indications for tube insertion were head and neck cancer (RIG: 40.4%, PEG: 35.3%), esophageal cancer (RIG: 15.4%%, PEG: 0%), CVA (RIG: 21.2%, PEG: 31.8%), neuromuscular pathology (RIG: 0%, PEG: 10.6%), trauma (RIG: 5.8%, PEG: 7.1%) and other (RIG: 17.3%, PEG: 15.3%).

Ljungdahl (2006) performed a prospective randomized trial at a hospital in Sweden on the complications of PEG versus surgical gastrostomy. 70 patients with impaired swallowing and a need for long-term (> four weeks) enteral feeding, irrespective of the cause were randomly assigned to PEG (n=35) or surgical gastrostomy (n=35). PEG was inserted using a pull technique. Open gastrostomy was performed using a 22-Fr gastrostomy tube. Preoperatively, all patients were administered an intravenous single 1.5-g dose of cefuroxime. Median age at baseline was 69 (22 to 82) years in the PEG group and 65 (19 to 88) years in the surgical gastrostomy group. Of the patients in the PEG group 60% were men versus 34.3% in the surgical gastrostomy group. Indications for tube insertion were oropharyngeal cancer (PEG: 11.4%, SG: 20%), neurologic disease (PEG: 28.6%, SG: 37.1%), stroke (PEG: 48.6%, SG: 37.1%) or cerebral trauma (PEG: 11.4%, SG: 5.7%).

Bankhead (2005) performed a retrospective cohort study on the complications of PEG versus surgical gastrostomy (open versus laparoscopic (LAP)). 91 patients undergoing gastrostomy tube insertion in the Temple University Hospital (teaching hospital) were included in the study. PEG was inserted using the Ponsky or pull technique. LAP was performed by dilatation up to 14Fr, after which a balloon tube was placed through a peel-away introducer. Open surgical gastrostomy was performed using the Stamm technique. A preoperative dose of prophylactic antibiotics was administered intravenously to all patients. 23 patients underwent PEG, 39 patients LAP gastrostomy and 29 patients open surgical gastrostomy. Mean age (SD) at baseline was 57.1±15.9 years in het PEG group, 56.1±18.3 years in the LAP group and 60.5±16.5 years in the open surgical gastrostomy group. Indications for tube insertion were ventilator-dependent respiratory failure (n=45), dysphagia (n=30), head and neck cancer (n=9) and altered mental status (n=7).

Oliveira (2016) performed a retrospective cohort study on the complications and mortality of PEG versus surgical gastrostomy (open versus LAP). 535 patients undergoing gastrostomy tube insertion in a tertiary center in Portugal with large experience in PEG procedures, were included in the study. 509 patients underwent PEG, eight patients LAP gastrostomy and 26 patients open surgical gastrostomy. Surgical procedures were not described. It was also not reported whether patients received antibiotic prophylaxis. Mean age (SD) at baseline was 63±15.7 years in the PEG group, 59.6±14.8 years in the LAP/open surgical gastrostomy group. Of the patients in the PEG groups 68% were men, versus 100% in de LAP group and 72.2% in the open surgical gastrostomy group. Indications for tube insertion were head and neck cancer (PEG: 37.3%, LAP: 100%, open: 22.2%), neurological dysphagia (PEG: 52%, LAP: 0%, open: 0%), drainage (PEG: 0.6%, LAP: 0%, open: 44.5%) or other (PEG: 10%, LAP: 0%, open: 33.3%).

Edelman (1998) performed a retrospective cohort study at a hospital in the USA on the complications and mortality of PEG versus LAP. 29 patients undergoing gastrostomy insertion (PEG or LAP) were included in the study. 17 patients underwent PEG, while 12 patients underwent LAP. LAP procedure was done using the technique described by Edelman and Unger. PEG was performed using a modified Gauderer-Ponsky method. Alternatively, a pull method was used. It was not reported whether patients received antibiotic prophylaxis. Mean age at baseline was 81 (43 to 97) years in the PEG group and 67 (20 to 94) years in the LAP group. Of the patients in the PEG groups 58.8% were men, versus 64.2% in de LAP group. Indications for tube insertion were inability to eat, malnutrition, and/or recurrent aspiration, which were not different between treatment groups (% not reported).

Ho (1999) performed a retrospective cohort study on the complications and mortality of PEG versus LAP. 356 patients undergoing gastronomy at the surgery department of a university medical center in the USA were included in the study. 82 patients underwent PEG, 60 patients LAP and 214 patients open surgical gastrostomy. PEG was performed using the push technique. LAP gastrostomy was placed using two 5-mm ports and needle-placed T-fasteners. Open surgical gastrostomy was performed using a double purse string technique. Preoperatively, all patients received intravenous antibiotics, either prophylactic or as part of ongoing therapy. Mean age at baseline was 52 years in the PEG group, 50 years in the LAP and 44 years in the open surgical gastrostomy group. Of the patients in the PEG groups 69.5% were men, versus 58.3% in de LAP group and 61.7% in the open surgical gastrostomy group. Indications for tube insertion were head and neck cancer (PEG: 29%, LAP: 32%, open: 11%), Esophageal cancer (PEG: 0%, LAP: 8%, open: 10%), neurological disorder (PEG: 35%, LAP: 3%, open: 11%), malnutrition (PEG: 1%, LAP: 3%, open: 14%) or trauma/burn (PEG: 22%, LAP: 40%, open: 25%).

Park (2019) performed a retrospective multicenter cohort study on the complications of PEG versus PRG. 418 patients who underwent initial PEG (n=324) or PRG tube insertion (n=94) for nutritional purpose at five university hospitals in South Korea were included. PEG tubes were inserted using the pull-type or introducer type. All PRG tubes were inserted under fluoroscopic guidance using a modified Seldinger technique. In the PRG group 86.2% of the patients received antibiotic prophylaxis, versus 89.5% in the PEG group. Mean age (SD) at baseline was 66.2±13.3 years in the PRG group and 66.7±14.8 years in the PEG group. Of the patients in the PRG group 61.7% were men versus 72.2% in the PEG group. Indications for tube insertion were medical diseases (PRG: 2.1%, PEG: 1.9%), neurological diseases (PRG: 59.6%, PEG: 74.1%) and surgical diseases (PRG: 29.8%, PEG: 18.5%).

Cherian (2019) performed a retrospective cohort study on the complications of PEG versus radiologically inserted gastrostomy (RIG). Patients with all-cause gastrostomy insertion at a quaternary institution in Australia were included. During the study period, 402 patients underwent gastrostomy insertion, of which 307 patients received a PEG tube and 95 patients a RIG tube. The type of PEG used was not reported. RIG was performed using gastric insufflation with three-suture gastropexy. Perioperatively, antibiotics were administered using a dosage of 1-2g IV cephazolin or 0.5g vancomycin for patients allergic to cephalosporins or known to be colonised with MRSA. Median age at baseline was 65 (35-89) years in the RIG group and 62 (18-91) years in the PEG group. Of the patients in the RIG group 68.4% were men versus 78.6% in the PEG group. Indications for tube insertion were head and neck cancer (RIG: 44.2%, PEG: 68.5%), other cancer (RIG: 25.2%, PEG: 6.5%) and no malignancy (RIG: 30.5%, PEG: 24.7%).

Table 1 Study characteristics of included studies for PEG, PRG and surgical gastrostomies in various patients groups

|

Author, year |

Study design |

Patient group |

Techniques (details) |

Selection technique |

Antibiotics |

|

Studies in Strijbos, 2018 |

|||||

|

Retrospective cohort study |

Various |

PEG (pull) PRG (gastric insufflation, T-fasteners) |

Not reported |

Preoperative antibiotics in PEG, but not standard in PRG. |

|

|

Laasch, 2003 |

Prospective multicenter cohort study |

Various |

PEG (pull) PRG (10.5 F Tilma or 12 F Ultrathane gastrostomy) |

Not reported (three cohorts from three different hospitals) |

No standard antibiotic prophylaxis. |

|

Möller, 2009 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Various |

PEG (pull) PRG (one-step or two-step procedure) |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

La Nauze, 2012 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Various |

PEG (pull) PRG (Pitman procedure) |

Not reported |

Standard peri-procedural antibiotics |

|

Laskaratos, 2013 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Various |

PEG (pull) PRG (modified Seldinger technique) |

Based on service availability, technical issues and physician preference. |

Antibiotics in PEG, but not in PRG. |

|

Galaski, 2009 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Various |

PEG (pull) PRG (not reported) |

Based on availability or physician preference of the service; the PRG method was not reserved for patients with head and neck cancer |

Antibiotics were not prescribed consistently as prophylaxis. |

|

Elliot, 1996 |

Prospective cohort study |

Various |

PEG (pull) PRG (gastric insufflation, Wills-Ogelsby catheter) |

Procedure was booked for the next available list; this determined the type of procedure performed. Except for CF patients (PEG) and esophageal obstruction (PRG). |

Antibiotics were not prescribed consistently as prophylaxis, except for CF patients. |

|

Other studies |

|||||

|

Park, 2019 |

Retrospective multicenter cohort study |

Medical, neurological and surgical diseases |

PEG (pull or introducer) PRG (modified Seldinger technique) |

Based on service availability, technical issues, and physician’s preference |

Antibiotics were not prescribed consistently as prophylaxis. |

|

Cherian, 2019 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Head and neck cancer, other cancer, no malignancy |

PEG (technique not reported) RIG (gastric insufflation with 3-suture gastropexy) |

Routine endoscopic first-line insertions, and radiology receiving those in whom this is contraindicated |

Standard peri-procedural antibiotics |

|

Strijbos, 2019 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Various, e.g. ALS, Head and neck cancer, other malignancy, neurological disease |

PEG (pull) PRG (Wills-Oglesby Percutaneous Gastrostomy) |

Based on clinical judgment and practical considerations |

Standard prophylactic antibiotics were not given in at least PRG. |

|

Vidhya, 2018 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Head and neck cancer, esophageal cancer, CVA, neuromuscular, trauma or other |

PEG (pull) RIG (18F balloon tipped Cook Medical Gastrostomy Tube) |

Based on availability or treating doctor preference |

Preoperative antibiotics in PEG, but not standard in PRG. |

|

Ljungdahl, 2006 |

Randomized trial |

Swallowing disorders (oropharyngeal cancer, neurologic disease, stroke or cerebral trauma) |

PEG (pull) Open gastrostomy (22-FR gastrostomy tube) |

n.a. |

Preoperative antibiotics |

|

Bankhead, 2005 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Ventilator dependent respiratory failure, dysphagia, head and neck cancer and altered mental status. |

PEG (Ponsky or pull) Open gastrostomy (Stamm) LAP (2 ports, T-fasteners, peel-away introducer) |

Based on surgeon preferences |

Preoperative antibiotics |

|

Oliveira, 2016 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Head and neck cancer, neurological dysphagia, drainage or other |

PEG (not reported) Open gastrostomy or LAP (not reported) |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Edelman, 1998 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Inability to eat, malnutrition, recurrent aspiration |

PEG (modified Gauderer-Ponsky method or pull) LAP (Edelman and Unger technique) |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Ho, 1999 |

Retrospective cohort study |

Head and neck cancer, esophageal cancer, neurological disorder, malnutrition, trauma/burn. |

PEG (push) Open gastrostomy (double purs string technique) LAP (2 ports, T-fasteners) |

Not reported |

Preoperative antibiotics |

Results

Mortality

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included five studies which reported on procedure related mortality (Elliot, 1996; Silas, 2005; Galaski, 2009; Möller, 2009; Laskaratos, 2013). Cherian (2019), Strijbos (2019) and Vidhya (2018) also reported procedure related mortality. Results are shown in Table 2. In total 7/1032 patients in the PRG group died due to the procedure, compared to 5/989 patients in the PEG group.

Table 2 Procedure related mortality (n/N) in patients with various diseases undergoing PEG or PRG

|

|

Procedure related mortality |

|

|

Author, year |

PRG (n/N) |

PEG (n/N) |

|

Elliot, 1996 |

1/45 |

0/33 |

|

Silas, 2005 |

0/193 |

0/177 |

|

Galaski, 2009 |

1/44 |

0/30 |

|

Möller, 2009 |

3/94 |

0/12 |

|

Laskaratos, 2013 |

0/40 |

0/53 |

|

Vidhya, 2018 |

0/52 |

0/85 |

|

Cherian, 2019 |

0/95 |

0/308 |

|

Strijbos, 2019 |

2/469 |

5/291 |

|

Total |

7/1032 |

5/989 |

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

Open

Bailey (1992), Ho (1999), Bankhead (2005), Ljungdahl (2006) and Oliveira (2016) reported on procedure related mortality for PEG versus open surgical gastrostomies. Results are shown in Table 3. In total, 8/679 patients in the PEG group died due to the procedure, compared to 13/323 patients in the surgical gastrostomy group.

Table 3 Procedure related mortality (n/N) in patients with various diseases undergoing PEG or surgical gastrostomy

|

|

Procedure related mortality |

|

|

Author, year |

PEG (n/N) |

Surgical gastrostomy (n/N) |

|

Bailey, 1992 |

2/30 |

2/45 |

|

Bankhead, 2005 |

0/23 |

0/29 |

|

Ljungdahl, 2006 |

1/35 |

2/35 |

|

Ho, 1999 |

4/82 |

9/214 |

|

Oliveira, 2016 |

1/509 |

unclear |

|

Total |

8/679 |

13/323 |

LAP

Edelman (1998), Ho (1999), Bankhead (2005) and Oliveira (2016) reported procedure related mortality for PEG versus laparoscopic gastrostomies. Results are shown in Table 4. In total, 5/631 patients in the PEG group died due to the procedure, compared to 3/121 patients in the laparoscopic gastrostomy group.

Table 4 Procedure related mortality (n/N) in patients with various diseases undergoing PEG or laparoscopic gastrostomy

|

|

Procedure related mortality |

|

|

Author, year |

PEG (n/N) |

Laparoscopic gastrostomy (n/N) |

|

Bankhead, 2005 |

0/23 |

0/39 |

|

Edelman, 1998 |

0/17 |

0/14 |

|

Ho, 1999 |

4/82 |

3/60 |

|

Oliveira, 2016 |

1/509 |

0/8 |

|

Total |

5/631 |

3/121 |

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Peristomal infection

PEG versus PRG

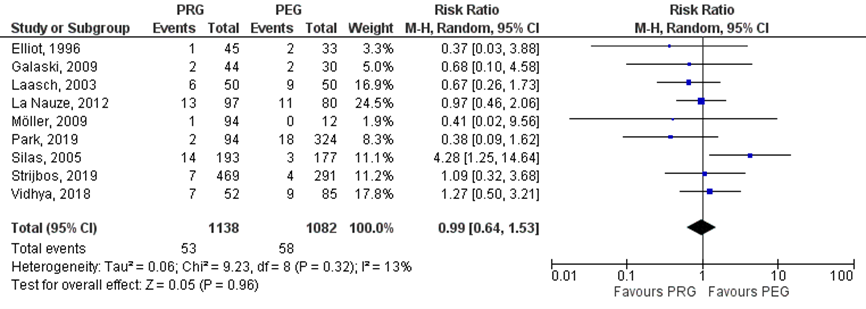

Strijbos (2018) included six studies which reported on peristomal infections (Elliot, 1996; Laasch, 2003; Silas, 2005; Galaski, 2009; Möller, 2009). Park (2019), Strijbos (2019) and Vidhya (2018) reported also on peristomal infections. In total, 53/1138 (4.7%) patients in the PRG group had peristomal infections, compared to 58/1082 (5.4%) patients in the PEG group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 0.99 (0.64 to 1.53, Figure 2.5), in favor of the PRG group. This difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant (RR> 0.8).

Figure 1 Peristomal infections in various patient groups undergoing PEG versus PRG

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

Ho (1999) reported 3/82 cases with perioperative peristomal infection in the PEG group, compared to 7/214 cases in the open surgical gastrostomy group. Oliveira (2016) reported 3/509 cases with peristomal infection in the PEG group. In the study of Ljungdahl (2006) in both groups 6/35 (17.1%) patients developed peristomal infection.

LAP

Ho (1999) reported 3/82 cases with perioperative wound infection in the PEG group, compared to no cases in the laparoscopic gastrostomy group (n=60). Edelman (1994) reported no cases of peristomal infection in both groups. Oliveira (2016) reported 3/509 cases with peristomal infection in the PEG group, while no morbidity occurred in the laparoscopic gastrostomy group (n=8).

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Systemic infection

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included four studies which reported on peritonitis or pneumonia (Elliot, 1996; Galaski, 2009; La Nauze, 2012; Möller, 2009). Furthermore, Park (2019), Strijbos (2019) and Vidhya (2018) reported on those outcome measures. In total, 10/895 patients in the PRG group suffered from peritonitis, compared to 2/855 in the PEG group (table 5.6). Besides, in the PRG group 16/801 patients developed pneumonia, compared to 14/843 in the PEG group (Table 5).

Table 5 Events (n/N) of peritonitis and pneumonia in various patient groups undergoing PRG or PEG

|

Author, year |

PRG |

PEG |

|

|

Events (n/N) |

Events (n/N) |

|

Peritonitis |

||

|

Elliot, 1996 |

3/45 |

0/33 |

|

Galaski, 2009 |

1/44 |

0/30 |

|

La Nauze, 2012 |

1/97 |

0/80 |

|

Möller, 2009 |

1/94 |

0/12 |

|

Park, 2019 |

0/94 |

1/324 |

|

Strijbos, 2019 |

2/469 |

0/291 |

|

Vidhya, 2018 |

2/52 |

1/85 |

|

Total |

10/895 |

2/855 |

|

Pneumonia |

||

|

Elliot, 1996 |

6/45 |

5/33 |

|

Galaski, 2009 |

1/44 |

0/30 |

|

La Nauze, 2012 |

4/97 |

4/80 |

|

Park, 2019 |

0/94 |

0/324 |

|

Strijbos, 2019 |

4/469 |

4/291 |

|

Vidhya, 2018 |

1/52 |

1/85 |

|

Total |

16/801 |

14/843 |

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

OPEN

Ljungdahl (2006) reported 1/35 case with local peritonitis in the PEG group and 2/35 cases with pneumonia in the surgical gastrostomy group. Oliveira (2016) described 3/509 cases in the PEG group which suffered from peritonitis due to leakage of gastric contents in the peritoneum. Ho (1999) reported 1/214 case with peritonitis in the open surgical gastrostomy group, compared to no cases in het PEG group (n=82).

LAP

Oliveira (2016) described 3/509 cases in the PEG group which suffered from peritonitis due to leakage of gastric contents in the peritoneum. No morbidity occurred in the laparoscopic gastrostomy group (n=8). In the study of Ho (1999) in both groups, none of the patients developed peritonitis.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Pain

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) did not report on the outcome measure pain. Park (2019) reported on pain over at least 30 days. In the PRG group, none of the patients had pain, compared to 7/324 (2.1%) in the PEG group. Strijbos (2019) reported also pain over 30 days, which was not further defined. In the PRG group, 43/469 (9.2%) patients had pain, compared to 12/291 (4.1%) in the PEG group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 2.22 (1.19 to 4.15), in favor of the PEG group. This difference was statistically significant and clinically relevant (RR> 1.25).

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies reported on pain for the comparison PEG versus SG.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Leakage

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included four studies which reported on leakage (Elliot, 1996; Galaski, 2006; Laasch, 2003; Möller, 2005). Furthermore, Park (2019) also reported on stoma leakage. In total, 17/327 patients in the PRG group suffered from leakage, compared to 10/449 patients in the PEG group (Table 6).

Table 6 Events (n/N) of leakages in various patient groups undergoing PRG or PEG

|

Author, year |

PRG |

PEG |

|

|

Events (n/N) |

Events (n/N) |

|

Elliot, 1996 |

4/45 |

1/33 |

|

Galaski, 2009 |

5/44 |

5/30 |

|

Laasch, 2003 |

2/50 |

0/50 |

|

Möller, 2009 |

3/94 |

1/12 |

|

Park, 2019 |

3/94 |

3/324 |

|

Total |

17/327 |

10/449 |

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

OPEN

Ho (1999) reported stoma leakage for 7/82 (8.5%) patients in the PEG group, compared to 13/214 (6.1%) patients in the open surgical gastrostomy group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 1.41 (0.58 to 3.40), in favor of the open surgical gastrostomy group. This difference was not statistically significant, but clinically relevant (RR> 1.25). In the study of Ljungdahl (2006) 4/35 (11.4%) patients in the PEG group suffered from stoma leakage, compared to 7/35 (20%) patients in the surgical gastrostomy group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 0.57 (0.18 to 1.78), in favor of the PEG group. This difference was not statistically significant, but clinically relevant (RR< 0.8).

LAP

Ho (1999) reported stoma leakage for 7/82 (8.5%) patients in the PEG group, compared to 5/60 (8.3%) patients in the surgical gastrostomy group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 1.02 (0.34 to 3.07), in favor of the surgical gastrostomy group. This difference was not statistically significant, nor clinically relevant (RR< 1.25). Edelman (1994) reported no cases of leakage in both groups. Oliveira (2016) described 3/509 cases in the PEG group which suffered from peritonitis due to leakage of gastric contents in the peritoneum.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Tube failure

PEG versus PRG

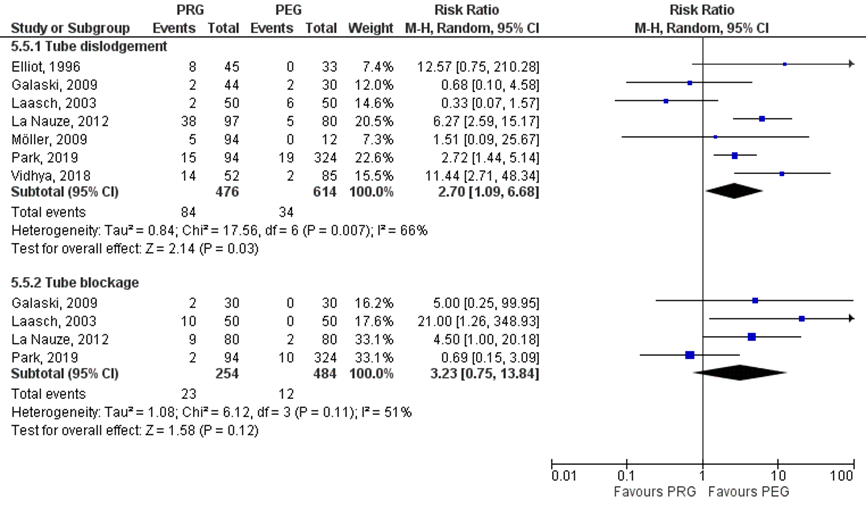

Strijbos (2018) included five studies which reported on tube dislodgement (Elliot, 1996; Galaski, 2006; La Nauze, 2012; Laasch, 2003; Möller, 2005). Furthermore, Park (2019) and Vidhya (2018) reported also on tube dislodgement. In total, 84/476 (17.6%) patients in the PRG group had tube dislodgement, compared to 34/614 (5.5%) patients in the PEG group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 2.70 (1.09 to 6.68), in favor of the PEG group (Figure 2.8). This difference was statistically significant and clinically relevant (RR> 1.25).

Strijbos (2018) included three studies which reported on tube blockage (Galaski, 2006; La Nauze, 2012; Laasch, 2003). Furthermore, Park (2019) reported also on tube blockage. In total, 23/254 (9.1%) patients in the PRG group had blocked tube, compared to 12/484 (2.5%) patients in the PEG group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 3.23 (0.75 to 13.84), in favor of the PEG group (Figure 2.8). This difference was statistically not significant, but clinically relevant (RR>1.25). Strijbos (2019) reported on tube complications, which included tube blockage, tube leakage and tube dislodgement. In the PRG group 124/469 (26.4%) patients had tube complications, compared to 8/291 (2.7%) patients in het PEG group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 9.62 (4.78 to 19.36), in favor of the PEG group. This difference was statistically significant and clinically relevant (RR> 1.25).

Besides, Elliot (1996) reported also on tube replacements, which were due to malfunctioning of the tube, tube dislodgments or tubes that were pulled out. In the PRG group, in 15/45 (33.3%) patients tube had to be replaced, compared to 8/33 (24.2%) patients in the PEG group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 1.38 (0.66 to 2.86), in favor of the PEG group. This difference was statistically not significant, but clinically relevant (RR> 1.25).

Finally, La Nauze (2012) reported 4/97 cases with tube malposition and 4/97 cases with tube deterioration in the PRG group, compared to respectively 1/80 and 3/80 cases in the PEG group.

Figure 2 Tube dislodgment and tube blockage in various patient groups undergoing PEG versus PRG

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

OPEN

Ho (1999) reported tube dislodgement for 2/82 (2.4%) cases in the PEG group, compared to 12/214 (5.6%) cases in the open surgical gastrostomy group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 0.43 (0.10 to 1.90), in favor of the PEG group. This difference was not statistically significant, but clinically relevant (RR< 0.8). In the study of Ljungdahl (2006) tube dislodgement was reported for 2/35 (5.7%) patients in the PEG group, compared to 6/35 (17.1%) patients in the surgical gastrostomy group.

LAP

Ho (1999) reported tube dislodgement for 2/82 (2.4%) cases in the PEG group, compared to 4/60 (6.7%) cases in the laparoscopic gastrostomy group. Oliveira (2016) described 3/509 cases in the PEG group which suffered dislocation of the tube with peritonitis due to leakage of gastric contents in the peritoneum. In the PEG group, also seven patients suffered tube dislocation leading to buried bumper syndrome.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Level of evidence of the literature

Mortality

The level of evidence for observational studies starts low. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure procedure related mortality was downgraded to very low because of risk of bias and/or imprecision. For PEG versus PRG number of events was very low, but total number of included patients was high. Since we expect that new data will not lead to different results, we did not downgrade for imprecision. For PEG versus surgical gastrostomy the number of events was low (< 300 events) and we therefore downgraded for imprecision. There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies, mainly due to confounding and deviations from intended interventions. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Peristomal infection

The level of evidence for observational studies starts low. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure peristomal infection was downgraded to very low because of risk of bias and/or imprecision. For PEG versus PRG number of events was very low, but total number of included patients was high. Since we expect that new data will not lead to different results, we did not downgrade for imprecision. For PEG versus surgical gastrostomy the number of events was low (< 300 events) and we therefore downgraded for imprecision. There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies, mainly due to confounding and/or selection of reported results. The results of the study from Silas (2005) show different results compared to the other included studies. This might be due to the fact that the PRG group included high number of patients with malignancies (69.4%) compared to the PEG group (23.2%). None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Systemic infection

The level of evidence for observational studies starts low. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure systemic infection was downgraded to very low because of risk of bias. For PEG versus PRG number of events was very low, but total number of included patients was high. Since we expect that new data will not lead to different results, we did not downgrade for imprecision. There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies, mainly due to confounding and/or selection of reported results. For PEG versus surgical gastrostomy, number of events was too few to draw a conclusion on the risk on systemic infection. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Pain

The level of evidence for observational studies starts low. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded to very low because of risk of bias and imprecision. The 95%CI of the effect estimate crossed the threshold for clinical relevance (RR 0.8/RR 1.25, imprecision). It is not clear how pain was defined/measured (risk of bias). None of the included studies reported on pain for the comparison PEG versus surgical gastrostomy. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Leakage

The level of evidence for observational studies starts low. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure leakage was downgraded to very low because of risk of bias and imprecision. For PEG versus PRG, the 95%CI of the effect estimate crossed the threshold for clinical relevance (RR 0.8/RR 1.25) and the null effect (imprecision). For PEG versus surgical gastrostomy, number of events was very low (< 300, imprecision). There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies, mainly due to confounding and/or selection of reported results. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Tube failure

The level of evidence for observational studies starts low. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure tube failure was downgraded to very low because of risk of bias and imprecision. The 95%CI of the effect estimate crossed the threshold for clinical relevance (RR 0.8/RR 1.25) and for some aspects of tube failure also the null effect (imprecision). There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies, mainly due to confounding and/or selection of reported results. None of the included studies compared PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

The included studies focused on the comparison between PEG and PRG or PEG and surgical gastrostomy. Based on this data we cannot draw conclusions on PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Submodule 2 Patients with head and neck cancer

3 studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Strijbos, 2018; Rustom, 2006 and Bailey, 1992).

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Strijbos (2018) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the outcomes of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) versus percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy (PRG). They searched Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane and DARE databases until May 2017. ROBINS-I and NOS scales were used for quality assessment. There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies. 16 observational studies were included. Those studies reported on 934 initial PEGs (placed using the pull method) and 1093 initial PRGs. Main outcomes were infectious and tube-related complications within 30 days, procedure related mortality and 30-day mortality. Subgroup analyses were performed for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) and patients having motor neuron diseases (MND). Three studies were included in the subgroup analysis for patients with head and neck cancer (Grant, 2009; Rustom, 2006 and McAllister, 2013, N=349). Study characteristics of the included studies on HNC patients are depicted in Table 2.9.

Rustom (2006) performed a retrospective cohort study at a regional center for head and neck cancer in the United Kingdom, on the complications and mortality of PEG, Radiologically Inserted Gastrostomy (RIG) and surgical gastrostomy (LAP and open). 78 HNC patients undergoing gastrostomy were included in the study. Preoperatively, all patients received antibiotics. Surgical procedures were not described. Mean age at baseline was 63.6 years in the PEG group, 64.8 years in the RIG group and 70.3 years in the surgical gastrostomy group. Of the patients in the PEG groups 31% were men, versus 19% in the RIG group and 8% in the surgical gastrostomy group.

Bailey (1992) performed a retrospective cohort study at a hospital medical center in the USA, on the complications and mortality of PEG versus two different surgical gastrostomy techniques. Data of randomly chosen 75 HNC patients were analyzed. PEG procedure was not described. In case of surgical gastrostomy, they used either the cuffed Silastic gastrostomy technique or Stamm technique. The Stamm technique was performed with a Malecot (n=10), foley (n-14) or DePezzor (n=4) catheter. It was not reported whether patients received antibiotic prophylaxis. In the total group, mean age at baseline was 61 year and 74.7% were men. Baseline characteristics are not reported by treatment groups.

Table 7 Study characteristics of included studies on PEG, PRG and surgical gastronomies for patients with head and neck cancer

|

Author, year |

Study design |

Techniques (details) |

Selection technique |

Antibiotics |

|

Studies in Strijbos, 2018 |

||||

|

Grant, 2009 |

Prospective multicenter cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (introducer) |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Rustom, 2006 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (not reported) |

Not reported |

Preoperative antibiotics |

|

McAllister, 2013 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (gastric insufflation, possibly ultrasound or fluoroscopy) |

Not reported |

No standard antibiotic prophylaxis |

|

Other studies |

||||

|

Rustom, 2006 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (pull) RIG (not reported) Surgical gastrostomy (not reported) |

Not reported |

Preoperative antibiotics |

|

Bailey, 1992 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (not reported) Surgical gastrostomy (stamm or cuffed Silastic gastrostomy) |

The choice of gastrostomy reflected surgeon bias independent of disease stage. |

Not reported |

Results

Mortality

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included two studies which reported on procedure related mortality (Grant, 2009; Rustom, 2006). In the study of Rustom (2006) 2/28 (7%) patients in the PRG group died due to the procedure, compared to none of the 40 patients in the PEG group. In the study of Grant (2009) 2/51 (3.9%) patients in the PRG group died, compared to 1/121 (0.8%) patients in the PEG group. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on mortality for PEG versus PRG.

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

Rustom (2006) reported procedure related mortality. In the PEG group none of the patients died, compared to 1/10 (10%) patients in the surgical gastrostomy group. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on mortality for PEG versus surgical gastrostomy.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

Rustom (2006) reported procedure related mortality. In the PRG group 2/28 (7%) patients died, compared to 1/10 (10%) patients in the surgical gastrostomy group. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on mortality for PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Peristomal infection

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included two studies which reported on peristomal infections (Grant, 2009; McAllister, 2013). Grant (2009) reported on major and minor peristomal infections. For 2/121 (1.7%) patients in the PEG group a major peristomal infection was reported, compared to none of the patients in the PRG group. In the PRG group 4/51 (7.8%) patients had systemic infection at the wound site. In the PEG group, 4/121 (3.3%) patients had systemic infection at the tube site. McAllister (2013) reported on 30-day postoperative peristomal infections. In both groups, for none of the patients peristomal infection was reported.

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure peristomal infection for the comparison PEG versus surgical gastrostomy.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure peristomal infection for the comparison PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Systemic infection

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included three studies which reported on peritonitis (Grant, 2009; Rustom, 2006 and McAllister, 2013). In the PRG group 5/167 (3.0%) patients had peritonitis, compared to none of the patients in the PEG group. Grant (2009) reported one case of aspiration pneumonia in the PRG group and no cases with sepsis in both groups. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on systemic infection for PEG versus PRG.

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

Rustom (2006) reported on peritonitis and pneumonia. In both groups, none of the patients developed peritonitis; in the surgical gastrostomy group one patient died from bronchopneumonia. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on systemic infection for PEG versus surgical gastrostomy.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

Rustom (2006) reported on peritonitis and pneumonia. In the PRG group 3/28 (10.7%) patients developed peritonitis, compared to none of the patients in the surgical gastrostomy group. In the surgical gastrostomy group one patient died from bronchopneumonia. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on systemic infection for PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Pain

PEG versus PRG

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure pain for the comparison PEG versus PRG.

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure pain for the comparison PEG versus surgical gastrostomy.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure pain for the comparison PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Leakage

PEG versus PRG

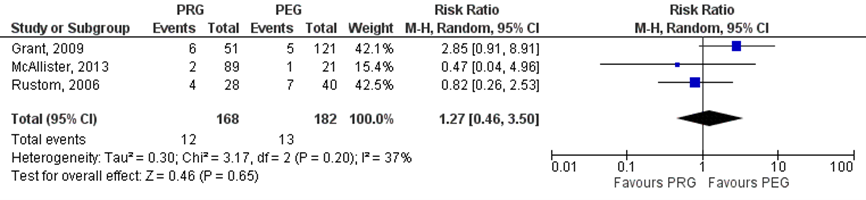

Strijbos (2018) included three studies which reported on leakage (Grant, 2009; Rustom, 2006 and McAllister, 2013). In the PRG group tube leakage was reported for 12/168 (7.1%) patients, compared to 13/182 (7.1%) patients in the PEG group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 1.27 (0.46 to 3.50), in favor of the PEG group (Figure 2.10). This difference was not statistically significant, but clinically relevant (RR> 1.25).

Figure 3. Tube leakage in head and neck cancer patients undergoing PEG versus PRG

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

Bailey (1992) reported on external leaks. In the PEG group 8/30 (26.7%) patients had external leak, compared to 15/45 (33.3%) patients in the surgical gastrostomy group. The risk ratio (95%CI) was 0.80 (0.39 to 1.65), in favor of the PEG group. This difference was not statistically significant, but clinically relevant (RR< 0.8). Rustom (2006) reported on peristomal leakage. In the PEG group 7/40 (17.5%) patients had peristomal leakage, compared to 3/10 (30%) patients in the surgical gastrostomy group.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

Rustom (2006) reported on peristomal leakage. In the PRG group 5/28 (17.9%) patients had peristomal leakage, compared to 3/10 (30%) patients in the surgical gastrostomy group.

Tube failure

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included three studies which reported on tube failures (Grant, 2009; Rustom, 2006 and McAllister, 2013). Grant (2009) reported three patients with tube dislodgement and one case with tube blockage in the PRG group (n=51), compared to one patient with tube rupture in the PEG group (n=121). Rustom (2006) reported six cases with tube dislodgement and one case with tube blockage in the PRG group (n=28), compared to respectively two and one patient(s) in the PEG group (n=40). McAllister (2013) reported 12 cases in which tube was removed accidentally and one case with tube construction in the PRG group (n=89). In the PEG group (n=21) one patient had buried bumper, one patient had obstructed tube and in one case tube was removed accidentally. Because of few events for the different aspects of tube failure, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on tube failure for PEG versus PRG.

PEG versus surgical gastrostomy

Bailey (1992) reported three cases with failed tube, seven cases in which tube was pulled out, one case with prolapse and one case with retraction in the PEG group (n=30), compared to respectively five, 13, no and one case(s) in the surgical gastrostomy group (n=45). Rustom (2006) reported two patients with tube dislodgement and one patient with tube blockage in the PEG group (n=40), compared to respectively two and none of the patients in the surgical gastrostomy group (n=10). Because of few events for the different aspects of tube failure, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on tube failure for PEG versus surgical gastrostomy.

PRG versus surgical gastrostomy

Rustom (2006) reported three patients with tube dislodgement and one patient with tube blockage in the PRG group (n=28), compared to respectively two and none of the patients in the surgical gastrostomy group (n=10). Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on tube failure for PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Level of evidence of the literature

Mortality/systemic infection/tube failure

Number of events was too few to draw a conclusion on the risk on procedure related mortality, systemic infection or tube failure due to PEG, PRG or surgical gastrostomy.

Peristomal infection

Number of events was too few to draw a conclusion on the risk on peristomal infection due to PEG versus PRG. None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Pain

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure pain.

Leakage

The level of evidence for observational studies starts low. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure leakage was downgraded to very low because of imprecision and risk of bias. The 95%CI of the effect estimate crossed the threshold for clinical relevance (RR 0.8/RR 1.25) and the null effect (imprecision). There was serious risk of bias in the studies, mainly due to confounding, missing data and selection of reported results. Finally, results were inconsistent between the different studies.

Submodule 3 patients with motor neuron disease

One study was included in the analysis of the literature (Strijbos, 2018).

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Strijbos (2018) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the outcomes of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) versus percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy (PRG). They searched Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane and DARE databases until May 2017. ROBINS-I and NOS scales were used for quality assessment. There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies. 16 observational studies were included. Those studies reported on 934 initial PEGs (placed using the pull method) and 1093 initial PRGs. Main outcomes were infectious and tube-related complications within 30 days, procedure related mortality and 30-day mortality. Subgroup analyses were performed for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) patients and patients having motor neuron diseases (MND). Six studies were included in the subgroup analysis for patients with motorn neuron diseases (Allen, 2013; Blondet, 2010; Chio, 2004; Desport, 2005; McDermott, 2015; Rio, 2010; N=529). Study characteristics of the included studies on patients with MND are depicted in table 8.

Table 8 Characteristics of the included studies on PEG, PRG and surgical gastronomies for patients with motor neuron diseases

|

Author, year |

Study design |

Techniques (details) |

Selection technique |

Antibiotics |

|

|

Studies in Strijbos, 2018 |

|||||

|

Allen, 2013 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (not reported) |

- |

- |

|

|

Blondet, 2010 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (gastric insufflation, t-fasteners) |

Not reported |

Systematic antibiotic prophylaxis in PEG patients |

|

|

Chio, 2004 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (gastric insufflation, a 12F polyurethane tube) |

PRG between 2000 and 2002, PEG before 2000. |

No antibiotics were routinely given |

|

|

Desport, 2005 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (gastric insufflation, T-fasteners) |

RIG as first line therapy when patients had a slow vital capacity less than 50%, or where PEG was refused. |

Preoperative antibiotics |

|

|

McDermott, 2015 |

Prospective multicenter cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (not reported) |

Based on practical and clinical considerations |

Not reported |

|

|

Rio, 2010 |

Retrospective cohort study |

PEG (pull) PRG (not reported) |

RIG: patients who had poor respiratory function and patients who had failed PEG as a result of diaphragm muscle weakness. |

Not reported |

|

RIG, radiology inserted gastrostomy

Results

Mortality

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included six studies which reported procedure related mortality (Allen, 2013; Blondet, 2010; Chio, 2004; Desport, 2005; McDermott, 2015; Rio, 2010). In the study of Allen (2013) two patients in the PEG group died. In the study of Rio (2010) one of the patients in the PEG group died. In other studies, none of the patients died due to the procedure. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on mortality for PEG versus PRG.

None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Peristomal infection

PEG versus PRG

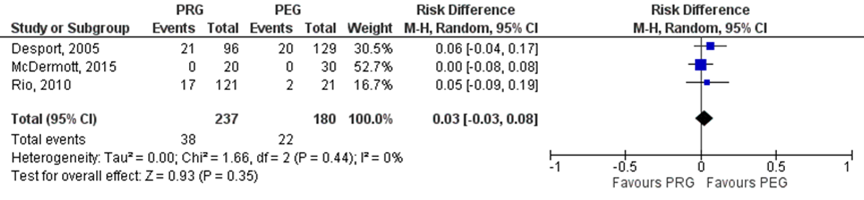

Strijbos (2018) included three studies which reported on infectious complications (Desport, 2005; Rio, 2010 and McDermott, 2015). In the PRG group 38/237 (16%) patients had infectious complications, compared to 22/180 (12%) patients in the PEG group (Figure 2.12). The risk difference (95%CI) was 0.03 (-0.03 to 0.08), in favor of the PEG group. This difference was not statistically significant. None of the studies specifically reported on peristomal infections.

Figure 4. Peristomal infections in patients with motor neuron diseases undergoing PEG versus PRG

None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Systemic infection

PEG versus PRG

McDermott (2015) reported on pneumonia. In both groups four patients developed pneumonia. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on systemic infection for PEG versus PRG.

None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Pain

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure pain for the comparison PEG versus PRG. Also none of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Leakage

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure leakage for the comparison PEG versus PRG. Also none of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Tube failure

PEG versus PRG

Strijbos (2018) included one study which reported on tube failure (Chio, 2004). In the PRG group one patient had tube displacement. In the PEG group, tube was ruptured in one patient. In both patients, no tube replacement was needed. Because of few events, it was not possible to draw a conclusion on the risk on tube failure for PEG versus PRG.

None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Level of evidence of the literature

Mortality/systemic infection/tube failure

Number of events was too few to draw a conclusion on the risk on procedure related mortality, systemic infection or tube failure due to PEG versus PRG. None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Pain/leakage

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures pain and leakage for the comparison PEG versus PRG. Also none of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Peristomal infection

The level of evidence for observational studies starts low. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure peristomal infection was downgraded to very low because of imprecision, risk of bias and indirectness. Number of events was low (< 300, imprecision). There was moderate to serious risk of bias in most of the studies, mainly due to confounding, deviations from intended interventions and selection of reported results. Finally, the included studies did not specify type of infections (indirectness). None of the included studies compared PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

The included studies focused on the comparison between PEG and PRG. Based on this data we cannot draw conclusions on PEG/PRG versus surgical gastrostomy.

Submodule 4 patients with swallowing disorders

Description of studies

No study could be included on the comparison between PEG, PRG and surgical gastrostomies in patients with swallowing disorders.

Results