Inleiding van de baring bij PPROM

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale timing voor de bevalling bij een zwangere met voortijdig prematuur gebroken vliezen voor 37 weken (PPROM)?

De uitgangsvraag bevat de volgende deelvragen:

- Wat is het meest aangewezen beleid tussen 34 en 37 weken bij een zwangere met PPROM (alle vrouwen): laat preterm bevallen danwel expectatief beleid tot 37 weken?

- Wat is het meest aangewezen beleid bij een zwangere met PPROM 34 tot 37 weken én GBS dragerschap*?

*Binnen deelvraag 2 gaat het om de subpopulatie van vrouwen met PPROM waarbij de aanwezigheid van groep B-streptokokken (GBS) in de urogenitale tractus (urine en/of rectum/vagina) is aangetoond.

Aanbeveling

Adviseer een expectatief beleid tot 37 weken bij een zwangere vrouw met PPROM als er geen tekenen van intra-uteriene infectie of andere foetale of maternale redenen˜̽͌ zijn om te streven naar een bevalling.

˜̽͌Zie module voor beleid bij PPROM en GBS dragerschap

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De beschikbare literatuur is onzeker over het effect van een geplande vroegtijdige bevalling na het breken van de vliezen tussen 34 en 37 weken op de uitkomst perinatale mortaliteit. Het verschil in zwangerschapsduur bij geboorte tussen de twee groepen was in alle studies klein. (Gemiddeld verschil 0,48 week; circa 3,3 dagen) (Bond, 2017). Het bewijs is van lage kwaliteit, vooral door het lage aantal sterftegevallen in beide groepen. De perinatale mortaliteit is bij deze zwangerschapsduur zeer laag en de interventie lijkt hier weinig invloed op te hebben. De beschikbare literatuur is ook onzeker over het effect op neonatale infecties. Bond 2017 en Quist-Nelson 2018 rapporteerden niet over maternale sepsis. In de PPROMEXIL trial kwam maternale sepsis gedefinieerd als temperatuur > 38,5 graden in combinatie met een positieve bloedkweek of hemodynamische instabiliteit waarvoor IC monitoring noodzakelijk was, zes keer voor in de groep die gepland vroeg beviel (6/366) en één keer (1/361) in de expectatieve groep. Er zijn geen gevallen van maternale mortaliteit in beide groepen beschreven. Dit komt ook overeen met de klinische ervaring omtrent deze uitkomstmaat.

Wel leidt een geplande vroegtijdige bevalling tussen 34 en 37 weken zwangerschap waarschijnlijk tot een verhoogd risico op neonatale RDS en NICU-opname (beide moderate grade) vergeleken met een expectatief beleid tot 37 weken. Er is waarschijnlijk geen klinisch relevant verschil in het risico op postpartum endometritis.

De literatuur laat geen voordeel zien voor een van de strategieën wat betreft neonatale mortaliteit en neonatale infecties. De literatuur wijst voor de overige cruciale uitkomstmaten (RDS, NICU opnames, manier van bevallen) richting expectatief beleid.

Een vroege bevalling zou alleen voordelig kunnen zijn om het risico op endometritis en chorioamnionitis te reduceren. Dit zijn echter geen cruciale uitkomstmaten. Voor alle andere niet-cruciale uitkomstmaten lijkt een expectatief beleid voordeliger (maternale mortaliteit, hyperbilirubinemie, ventilatiebehoefte en gebruik van pijnmedicatie tijdens de bevalling) of gelijkwaardig (endometritis, Apgar score < 7, maternaal bloedverlies) te zijn. De overige uitkomstmaten (hypoglycaemie, urogenitale infecties, patiënt tevredenheid, moeder-kind bonding) worden in de betreffende studies niet gerapporteerd.

De overall bewijskracht is gelijk aan de laagst gevonden bewijskracht van één van de cruciale uitkomstmaten en is laag.

In de twee-jaars follow-up van de kinderen geboren in de PPROMEXIL studie, waaraan 44% van de oorspronkelijk gerandomiseerde moeders meededen (van der Heyden, 2015), werden iets minder afwijkende scores in de screenende vragenlijsten voor gedrags- en ontwikkelingsproblemen (ASQ (Ages and Stages questionnaire (14 versus 26 %, (verschil in percentage -11,4 (95% CI -21,9 tot -0,98; p = 0.033)) en CBCL (Child Behaviour Checklist (13 versus 15% verschil in percentage -2,13 (95% CI -11,2 tot 6.94; p = 0,645)) gezien bij kinderen na een beleid gericht op geplande vroege bevalling vergeleken met een expectatief beleid. De follow-up was echter niet compleet en bovendien werden de kinderen niet zelf onderzocht.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Zwangere vrouwen hechten waarde aan objectieve informatie over de afweging tussen de twee behandelstrategieën. Ze hebben bij afwachtend beleid behoefte aan goede informatie over welke controles er zijn, en duidelijke instructies over waar ze zelf op moeten letten.

In de studies werden de waarden en voorkeuren van de zwangere vrouwen niet onderzocht. In de PPROMEXIL studie werden ook patiëntengegevens verzameld van vrouwen die geschikt waren voor randomisatie, maar niet aan de RCT wensten deel te nemen (31%). De voorkeur voor een expectatief beleid van deze vrouwen was de reden om niet deel te nemen aan de studie.

Een vroege baring kan wenselijk zijn in het geval van een (beginnende) infectie. Vrouwen en hun partners vinden het belangrijk dat ze hier goed op voorbereid worden.

Specifiek moet er aandacht zijn voor de sociale en mentale balans van de vrouw, haar partner en hun familie om de langere duur, intensiteit en belasting van een klinische opname van moeder en dreiging van vroeggeboorte, het hoofd te bieden. Het te verwachten verloop van de zwangerschap, bevalling en nazorg, dient dan ook met hen besproken te worden. Een goede informatievoorziening maakt dat de vrouw en haar partner in staat zijn om zich voor te bereiden en acties te ondernemen om de gevolgen van een opname en mogelijke vroeggeboorte sociaal ook te organiseren en mentaal te kunnen dragen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Van zowel de PPROMEXIL studies (Vijgen et al, 2014) als de PPROMT studie (Lain, 2016) is een kosteneffectiviteitsanalyse verricht. Bij de PPROMEXIL studie bedroegen de gemiddelde kosten per vrouw € 8094 de groep die gepland vroeg beviel en € 7340 voor expectatief beleid (verschil € 754; 95% betrouwbaarheidsinterval -335 tot 1802). Dit is een niet-significant verschil. Dit verschil ontstond voornamelijk in de postpartumperiode, waar de gemiddelde kosten € 5669 bedroegen voor de groep vroege bevalling versus € 4801 voor expectatief beleid. De kosten van de bevalling waren hoger bij vrouwen die waren gerandomiseerd voor geplande vroege bevalling vergeleken met vrouwen die gerandomiseerd waren voor expectatief beleid (€ 1777 versus € 1153 per vrouw). De antepartumkosten in de groep met expectatief beleid waren hoger vanwege het langere antepartumverblijf van de moeder in het ziekenhuis.

Voor de groep die gerandomiseerd werd tussen 36 en 37 weken werden er geen verschillen in kosten gevonden tussen de 2 behandelstrategieën. In de groep die werd gerandomiseerd tussen 35 en 36 weken was dit verschil echter wel aanwezig (Vijgen, 2014).

In de PPROMEXIL studies waren de vrouwen klinisch opgenomen in beide groepen. Wellicht zou de zwangere na PPROM tussen 34 en 37 weken middels thuismonitoring of poliklinisch kunnen worden gemonitord waardoor de zorgkosten verlaagd zouden kunnen worden.

Van de PPROMT trial werd ook een economische analyse verricht (Lain, 2016). In deze studie werden geen significante verschillen gevonden in kosten tussen de twee behandelopties.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Expectatief beleid is aanvaardbaar, haalbaar en vereist geen implementatietraject en is overeenkomstig het huidige beleid. Het is aannemelijk dat de voordelen van expectatief beleid overeenkomen met het belang en de voorkeur van de meeste patiënten en de nu al gangbare zorg in de gynaecologische praktijken.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Hoewel de beschikbare bewijslast laag is, lijken vrijwel alle uitkomstmaten in het voordeel van expectatief beleid te wijzen. Een geplande vroege bevalling lijkt gepaard te gaan met meer risico’s dan expectatief beleid. Er zijn dan ook geen argumenten om routinematig een vroege bevalling te adviseren na PPROM tussen 34 en 37 weken. Expectatief beleid is klinisch haalbaar en wordt veelal toegepast.

Zorg hierbij voor goede informatievoorziening voor de vrouw en haar partner met betrekking tot de verwachte opnameduur en schenk aandacht aan haar psycho-sociale situatie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er zijn twee strategieën bij PPROM, streven naar een bevalling tussen 34 en 37 weken AD en expectatief beleid tot 37 weken AD en dan streven naar bevalling. Het is onduidelijk welk beleid tot betere uitkomsten leidt voor zowel moeder als kind. Dit geldt ook voor vrouwen met PPROM voor 34 weken zwangerschapsduur die nog niet bevallen zijn bij het bereiken van de termijn van 34 weken (module inleiding van de baring bij PPROM ).

Daarnaast is het onduidelijk wat het beste beleid is voor vrouwen met PPROM die GBS-drager zijn gezien het mogelijk verhoogde risico op neonatale GBS infectie. Er is hierin in Nederland praktijkvariatie; sommige klinieken adviseren vanaf 34 weken de bevalling na te streven, terwijl anderen afwachten tot 37 weken zwangerschapsduur (module inleiding van de baring bij PPROM en GBS dragerschap ) .

Voor het bepalen van GBS-dragerschap wordt verwezen naar de richtlijn Preventie en behandeling van early-onset neonatale infecties (https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/preventie_en_behandeling_van_early-onset_neonatale_infecties/intrapartum_antibiotica_op_basis_van_risicofactoren_bij_early-onset_neonatale_infecties.html), waarin staat dat bij dreigende vroeggeboorte < 37 weken AD (= aanwezigheid van risicofactor) wordt gescreend op GBS-kolonisatie door middel van een rectovaginale kweek.

Module Inleiding van de baring bij PPROM

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Critical outcome measures

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management* until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in perinatal mortality among neonates.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in outcome perinatal infections among neonates. Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM increases the risk of respiratory distress syndrome compared to expectant management until 37 weeks.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management slightly increases the number of NICU admissions among neonates.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in the rate of Caesarean deliveries.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

Important outcome measures

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy versus expectant management until 37 weeks on maternal mortality in women with PPROM. Maternal mortality did not occur in the reported studies.

Sources: (Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in outcome postpartum endometritis. Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM probably increases the risk of hyperbilirubinemia compared to expectant management until 37 weeks.

Sources: (Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks probably results in little to no difference in the number of neonates with an Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM probably increases the risk of need for ventilation among neonates compared to expectant management until 37 weeks.

Sources: (Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

|

High GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM results in a reduction of clinical chorioamnionitis compared to expectant management until 37 weeks.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in postpartum haemorrhage.

Sourced: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in in little to no increase in the use of pain medication during delivery.

Sources: (Bond, 2017; Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measures maternal sepsis, neonatal hypoglycaemia, urogenital infection, patient satisfaction and mother-child bonding were not reported. Sources: (Bond, 2017; Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following sub question:

What are the (non) beneficial effects of immediate delivery (before 37 weeks gestational age) versus an expectant policy (after 37 weeks gestational age) on neonatal and maternal outcomes?

P: Pregnant women with preterm premature rupture of membranes before 37+0 weeks of pregnancy.

I: (Immediate) delivery between 34+0 and 36+6 weeks of pregnancy.

C: Expectant management until 37+0 weeks of pregnancy unless medical indication to pursue delivery.

O: Perinatal mortality, perinatal infections (early sepsis within 72 hours after birth proven by blood culture), respiratory distress syndrome, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)-admission, maternal sepsis, maternal mortality, delivery mode (instrumental/non instrumental, vaginal/caesarean delivery), neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal hypoglycemia, Apgar-score < 7 after 5 minutes, neonatal need for ventilation, postpartum endometritis, maternal urogenital infection, chorioamnionitis (clinical and histological), postpartum haemorrhage, pain medication during delivery, maternal satisfaction about childbirth/childbirth experience and bonding between mother and child.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered perinatal mortality, perinatal infections (early sepsis within 72 hours after birth proven by blood culture), respiratory distress syndrome, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)-admission, delivery mode (instrumental/non instrumental, vaginal/caesarean delivery) and maternal sepsis as critical outcome measures for decision making. Maternal mortality, neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal hypoglycemia, Apgar-score < 7 after 5 minutes, neonatal need for ventilation, maternal urogenital infection, postpartum endometritis, chorioamnionitis (clinical and histological), postpartum hemorrhage, pain medication during delivery, maternal satisfaction about childbirth/childbirth experience and bonding between mother and child were defined as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above, but used the definitions used in the studies.

For the outcome measures maternal and perinatal mortality any statistically significant difference was considered as a clinically important difference between groups.

For all other outcome measures, the GRADE default - a difference of 25% in the relative risk for dichotomous outcomes (RR< 0.8 or RR> 1.25) and 0.5 standard deviation for continuous outcomes - was taken as a minimal clinically important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until July 28th, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 255 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria 1) immediate labour induction was compared with expectant management in women with PPROM 34 to 37 weeks of gestation, 2) at least one of the predefined outcome measures was reported. Fourteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 12 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 2 systematic reviews and meta-analyses were included.

Results

Two systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Bond, 2017; Quist-Nelson, 2018). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Summary of literature

Description of studies

The Cochrane systematic review by Bond (2017) compared planned early birth with expectant management in women with PPROM on foetal, infant and maternal well-being. Immediate labour induction included induction of labour by any means and vaginal birth as well as caesarean section. Expectant management involved waiting until spontaneous birth or until the baby was at term (37 weeks of gestation). For the purpose of this review, only trials that included women between 34-37 weeks of gestation were included. A total of 5 RCTs were included: three multicentre trials, i.e. PPROMT in 11 countries (Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Romania, South Africa, UK and Uruguay)(Morris, 2016), and PPROMEXIL-1 and PPROMEXIL-2 in The Netherlands (Van der Ham, 2012a+b), and two single centre trials (Albania and USA) (Koroveshi, 2013; Naef, 1999).

The individual participant data meta-analysis by Quist-Nelson (2018) compared planned immediate delivery and expectant management in women with PPROM between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation. Immediate labour induction included both planned early vaginal birth as well as caesarean section. The review included only trials that could deliver individual study data when contacted. A total of 3 RCTs were included: the three multicentre trials reported earlier (Morris, 2016; Van der Ham, 2012a+b).

Results

Crucial outcome measures

1. Perinatal mortality

Four trials (including 2686 neonates) reported on the outcome measure perinatal mortality (Bond, 2017). Perinatal mortality was not further defined (Bond, 2017).

Table 3.1 Perinatal mortality, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

|

Study |

Immediate Delivery

|

Expectant Management

|

Risk difference, random effects model (95% CI) |

Heterogeneity, I2 |

|

Morris, 2016 |

1/923 (0.1%) |

1/910 (0.1%) |

0 (0 to 0) |

- |

|

Naef, 1998 |

0/57 |

0/63 |

- |

- |

|

Van der Ham 2012a |

0/268 |

0/270 |

- |

- |

|

Van der Ham 2012b |

1/100 (1%) |

0/95 |

- |

- |

|

Total |

2/1348 (0.1%) |

1/1338 (0.1%) |

0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) |

0% |

Source: Bond (2017); I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Perinatal mortality was reported in 2 cases out of 1348 (0.1%) in the immediate delivery group compared to 1 case out of 1338 (0.1%) in the expectant management group (Absolute risk reduction 0%, 95%CI 0 to 0%) (Table 3.1).

2. Perinatal infections confirmed with a blood culture

Four trials (including 2691 neonates) reported on the outcome measure perinatal infections confirmed with a blood culture (Bond, 2017). Neonatal infection/sepsis (confirmed) was defined as a proven neonatal infection confirmed with a blood culture within 48 hours of birth (Bond, 2017).

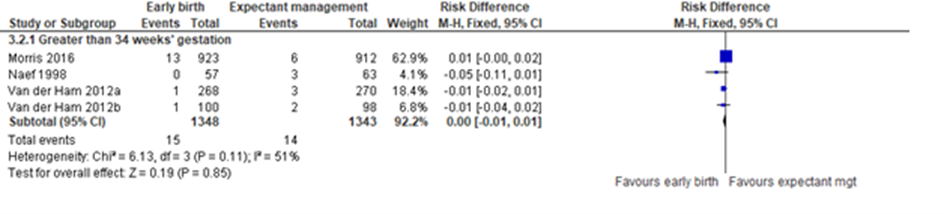

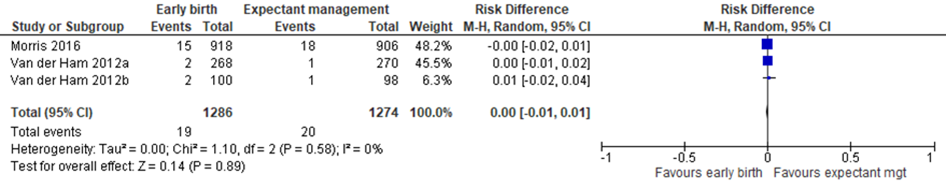

Figure 3.2 Perinatal infections confirmed with a blood culture, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation

Source: Bond (2017); Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Perinatal infections, confirmed with blood culture, were reported in 15 cases of 1348 (1%) in the immediate delivery group compared to 14 cases of 1343 (1%) in the expectant management group (Absolute risk reduction 0%, 95CI -1% to 1%) (Figure 3.2). The trial by Morris (2016) had more events in the early birth group and heterogeneity was moderate (I2=51%). Morris used prophylactic antibiotics, however when analysed with subgroups for whether or not prophylactic antibiotics were used, results were comparable (Bond, 2017). The other (smaller) trials besides Morris reported relatively less events.

3. Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS)

Five trials (including 2992 neonates) reported on the outcome measure respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (Bond, 2017). The outcome was not further defined (Bond, 2017).

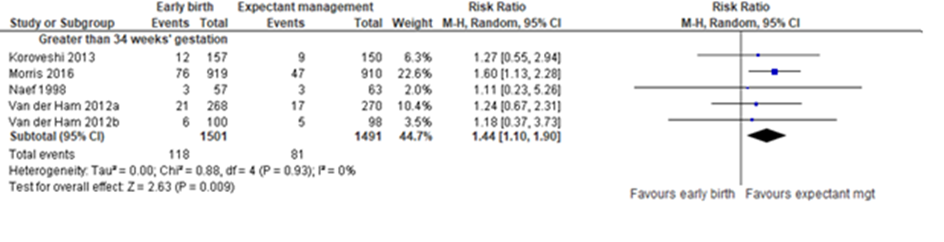

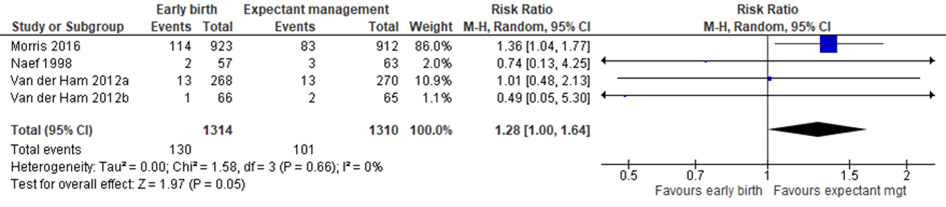

Figure 3.3 Respiratory distress syndrome, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

Source: Bond (2017); Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

RDS was reported in 118 cases of 1501 neonates (8%) in the immediate delivery group compared to 81 cases in 1491 neonates (5%) in the expectant management group, which was a statistically significant difference in favour of expectant management (Absolute risk reduction 3%, RR 1.44 (95%CI 1.10 to 1.90)) (Figure 3.3).

4. Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)-admission

Four trials (including 2691 neonates) reported on the outcome measure NICU-admission (Bond, 2017). The outcome was not further defined (Bond, 2017).

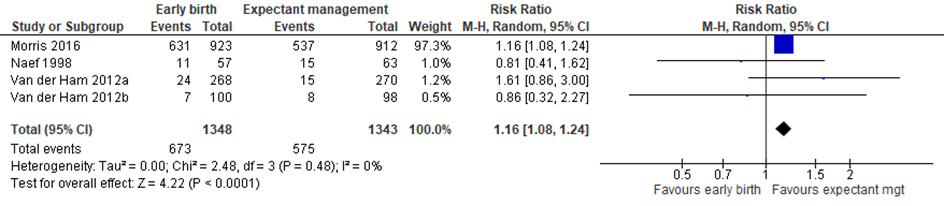

Figure 3.4 NICU admission, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

Source: Bond (2017); Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Admission to the NICU was reported in 673/1348 neonates (50%) in the immediate delivery group versus 575/1343 (43%) in the expectant management group, which was a statistically significant difference in favour of expectant management (Absolute risk difference 7%, RR 1.16 (95%CI 1.08 to 1.24)) (Figure 3.4). Two smaller studies showed a point estimate on the ‘immediate delivery’ side, however these were smaller studies that did not significantly impact the overall estimate when removed.

5. Delivery mode: Caesarean delivery

Five trials (including 2992 cases) reported on the outcome measure delivery mode (Bond, 2017). Only the delivery mode by means of Caesarean delivery (and not: assisted versus not assisted birth) was reported (Bond, 2017).

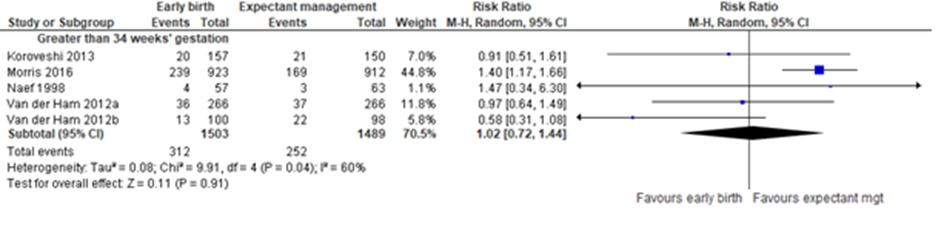

Figure 3.5 Caesarean delivery, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

Source: Bond (2017); Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Caesarean delivery was reported in 312/1503 (21%) cases in the immediate delivery group versus 252/1489 (17%) cases in the expectant management group (Absolute risk difference 4%, RR 1.02 (95%CI 0.72 to 1.44)) (Figure 3.5). Results were heterogenous (I2=60%). It is unclear what caused this inconsistency between studies, however it could be due to differences in local clinical practice. There was no statistically significant difference in rates of caesarean sections because of foetal distress between immediate delivery and expectant management (RR 0.89 (95%CI 0.66 to 1.20)) (Bond, 2017).

6. Maternal sepsis

This outcome was not reported.

7. Maternal mortality

Maternal death was reported in three trials (including 2563 women) (Quist-Nelson, 2018). Maternal death was not further defined (Quist-Nelson, 2018). No cases of maternal death were reported in the immediate delivery group (0/1,289) and no cases in the expectant management group (0/1,274). The risk ratio could therefore not be determined for this outcome.

Important outcome measures

8. Postpartum endometritis

Three trials (including 2563 women) reported on the outcome measure postpartum endometritis (Bond, 2017). Postpartum endometritis was not further defined (Bond, 2017).

Table 3.6 Postpartum endometritis, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

|

Study |

Immediate Delivery

|

Expectant Management

|

Risk difference, random effects model (95% CI) |

Heterogeneity, I2 |

|

Morris, 2016 |

1/923 (0.1%) |

4/912 (0.4%) |

0.00 (-0.01 to 0.00) |

- |

|

Van der Ham 2012a |

2/266 (0.8%) |

4/266 (1.5%) |

-0.01 (-0.03 to 0.01) |

- |

|

Van der Ham 2012b |

0/100 |

0/95 |

0.00 (-0.02 to 0.02) |

- |

|

Total |

3/1289 (0.2%) |

8/1273 (0.6%) |

0.00 (-0.01 to 0.00) |

0% |

Source: Bond (2017); I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Postpartum endometritis was reported in 3/1289 women (0.2%) in the immediate delivery group versus 8/1273 (0.6%) in the expectant management group (Absolute risk reduction -0.4% (95%CI -1% to 0%) (table 3.6).

9. Hyperbilirubinemia

Three trials (including 2565 women) reported on the outcome measure hyperbilirubinemia (Quist-Nelson, 2018). The outcome measure was not further defined (Quist-Nelson, 2018). The results were pooled, however individual study results were not reported. The risk ratio (RR) was adjusted for trial and gestational age at randomization.

Hyperbilirubinemia was reported in 655/1288 neonates (51%) in the immediate delivery group versus 549/1277 (43%) in the expectant management group (adjusted RR 1.18 (95%CI 1.09 to 1.28)). The effect was statistically significant in favour of expectant management (p<0.01). Heterogeneity between trials was significant (p heterogeneity=0.04). However, individual study results or the possible reason for heterogeneity were not reported (Quist-Nelson, 2018).

10. Hypoglycaemia

This outcome was not reported.

11. Apgar-score < 7 at 5 minutes

Three trials (including 2560 neonates) reported on the outcome Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes (Bond, 2017).

Figure 3.7 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

Source: Bond (2017); Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes was reported in 19/1286 cases (2%) in the immediate delivery group and 20/1274 (2%) in the expectant management group (Absolute risk difference 0% (95%CI -1% to 1%) (Figure 3.7) (Bond, 2017).

12. Need for ventilation

Four trials (including 2624 neonates) reported on the outcome measure need for ventilation (Bond, 2017). The outcome measure was not further defined (Bond, 2017).

Figure 3.8 Need for ventilation, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

Source: Bond (2017); Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Among the immediate delivery group, 130/1314 neonates (10%) were in need for ventilation compared to 101/1310 (8%) among the expectant management group, which was a statistically significant difference in favour of expectant management (RR1.28 (95%CI 1.00 to 1.64)) (Figure 3.8).

13. Urogenital infection

This outcome was not reported.

14. Chorioamnionitis (clinical and histological)

The working group was interested in clinical as well as histological assessment of chorioamnionitis. Three trials (including 850 women) reported on the outcome measure clinical chorioamnionitis (Bond, 2017). Clinically diagnosed amnionitis was defined as “maternal temperature associated with uterine tenderness, maternal or foetal tachycardia, or both, and/or foul smelling amniotic fluid in the absence of any other cause of identifiable infection” (Bond, 2017).

The two trials by Van der Ham also reported on histological chorioamnionitis, which was assessed by sending in the placenta for histological examination after birth (Van der Ham 2012a, van der Ham 2012b). The study authors did not report the total number of included placentas, therefore pooled results could not be determined.

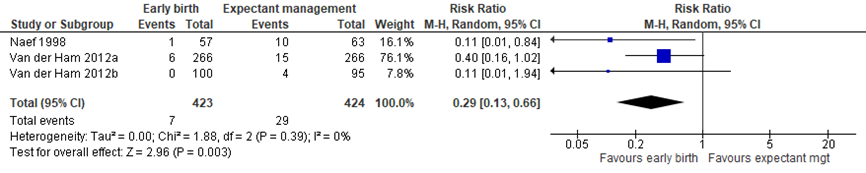

Figure 3.9 Clinical chorioamnionitis, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

Source: Bond (2017); Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

In the immediate delivery group 7/423 (2%) cases of clinical chorioamnionitis were reported compared to 29/424 (7%) cases in the expectant management group (RR 0.29 (95%CI 0.13 to 0.66)) (Figure 3.9). The difference was statistically significant in favour of immediate delivery.

15. Postpartum haemorrhage

Three trials (including 2565 women) reported on the outcome measure postpartum haemorrhage (Quist-Nelson, 2018). The outcome measure was not further defined (Quist-Nelson, 2018). The results were pooled, but individual study results were not reported. The risk ratio (RR) was adjusted for trial and gestational age at randomization (Quist-Nelson, 2018). In the immediate delivery group 53/1291 (4%) cases of postpartum haemorrhage were reported compared to 57/1274 (4%) in the expectant management group (Adjusted RR, RR 0.94 (95%CI 0.65 to 1.35).

16. Pain medication during delivery

Three trials (including 2562 women) reported on the outcome measure pain medication (Bond, 2017). Pain medication was defined as the use of epidural/spinal anaesthesia during delivery (Bond, 2017).

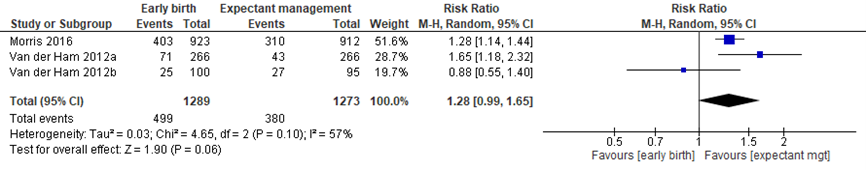

Figure 3.10 Pain medication: use of epidural/spinal anaesthesia, immediate delivery versus expectant management in women with PPROM

Source: Bond (2017); Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistically heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

In the immediate delivery group epidural/spinal anaesthesia was administered in 499/1289 women (39%) versus 380/1273 (30%) in the expectant management group (RR 1.28 (95%CI 0.99 to 1.65)) (Figure 3.10).

17. Patient satisfaction /childbirth experience

This outcome was not reported.

18. Bonding

This outcome was not reported.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure perinatal mortality started high and was downgraded with 2 levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (3 events in 2686 participants).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure perinatal infections started high and was downgraded with 2 levels to a low GRADE, one level because of imprecision (29 events in 2691 participants) and one level because of inconsistency (I2=52%).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure respiratory distress syndrome started high and was downgraded with 1 level to a moderate GRADE because of imprecision (upper boundary of clinical relevance RR> 1.25 was exceeded).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure NICU admission started high and was downgraded with one level to a moderate GRADE because of inconsistency (point estimate of two smaller trials differed).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure caesarean delivery started high and was downgraded with 2 levels to a low GRADE because of inconsistency (point estimates differed and high heterogeneity I2=60%). It was decided not to downgrade for imprecision as well, as this could be the result of inconsistency.

The outcome measure maternal sepsis was not reported.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure maternal mortality started high and was downgraded with 3 levels to a very low GRADE because of severe imprecision (no events were reported). Because no events of maternal mortality were reported, it was not possible to draw conclusions based on this outcome.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postpartum endometritis started high and was downgraded with 2 levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (11 events in 2562 participants).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hyperbilirubinemia started high and was downgraded with 1 level to a moderate GRADE because of imprecision (the upper level of clinical relevance RR> 1.25 was exceeded).

The outcome measure hypoglycaemia was not reported.

The outcome measure Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes started high and was downgraded with one level to a moderate GRADE because of imprecision (39 events in 2560 participants).

The outcome measure need for ventilation started high and was downgraded with 1 level to a moderate GRADE because of imprecision (the upper boundary of clinical relevance RR>1.25was exceeded).

The outcome measure urogenital infection was not reported.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure chorioamnionitis started high and was not downgraded.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postpartum haemorrhage started high and was downgraded with 2 levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (both the lower and upper boundaries of clinical relevance were exceeded).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain medication during delivery started high and was downgraded with 2 levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (the upper boundary of clinical relevance RR> 1.25 was exceeded) and inconsistency (point estimate of Van der Ham 2012b differed from the other trials; I2 = 57%).

The outcome measure patient satisfaction was not reported.

The outcome measure mother-child bonding was not reported.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table:

Risk of bias table 3a:

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Bond, 2017 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Quist-Nelson 2018 |

Yes |

Yes, but only individual participant data was included |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes, used individual study data and corrected for trial and gestational age |

No |

Yes |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Money, 2013 |

Guideline from 2013 about GBS in neonate, no comparison labour induction versus expectant management |

|

Buchanan, 2010 |

Former version of Bond 2017 |

|

Lain, 2017 |

Economic analysis of RCT by Morris 2016 |

|

Lynch, 2019 |

Observational comparison between labour induction at 34 weeks and waiting until 35 weeks |

|

Pasquier, 2019 |

RCT, comparison between induction and expectant management until 34 weeks |

|

Van der Ham, 2007 |

Trial protocol |

|

Vijgen, 2014 |

Economic analysis of RCT by Van der Ham 2012 |

|

Money, 2013 |

Guideline from 2013 about GBS in neonate, no comparison labour induction versus expectant management |

Literature search strategy

|

Richtlijn: Geboortezorg top 50 – cluster 6 |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: 3A: Wat is de optimale timing voor inleiden van de baring bij een zwangere met PPROM? 3B: Welke plaats heeft inleiding van de baring bij PPROM en GBS dragerschap tussen 34 en 37 wk?? |

|

|

Database(s): Embase, Medline |

Datum: 28-7-2020 |

|

Periode: 2000 – juli 2020 |

Talen: Engels |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Miriam van der Maten |

|

|

Toelichting en opmerkingen:

|

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

Embase |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

63 |

37 |

66 |

|

RCT |

163 |

83 |

189 |

|

Totaal |

226 |

120 |

255 |

Critical outcome measures

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management* until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in perinatal mortality among neonates.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in outcome perinatal infections among neonates. Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM increases the risk of respiratory distress syndrome compared to expectant management until 37 weeks.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management slightly increases the number of NICU admissions among neonates.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in the rate of Caesarean deliveries.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

Important outcome measures

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy versus expectant management until 37 weeks on maternal mortality in women with PPROM. Maternal mortality did not occur in the reported studies.

Sources: (Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in outcome postpartum endometritis. Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM probably increases the risk of hyperbilirubinemia compared to expectant management until 37 weeks.

Sources: (Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks probably results in little to no difference in the number of neonates with an Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM probably increases the risk of need for ventilation among neonates compared to expectant management until 37 weeks.

Sources: (Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

|

High GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM results in a reduction of clinical chorioamnionitis compared to expectant management until 37 weeks.

Sources: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in little to no difference in postpartum haemorrhage.

Sourced: (Bond, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

Immediate delivery between 34 and 37 weeks of pregnancy in women with PPROM compared to expectant management until 37 weeks may result in in little to no increase in the use of pain medication during delivery.

Sources: (Bond, 2017; Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measures maternal sepsis, neonatal hypoglycaemia, urogenital infection, patient satisfaction and mother-child bonding were not reported. Sources: (Bond, 2017; Quist-Nelson, 2018) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 27-03-2023

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 12-05-2023

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen.

Werkgroep

- Dr. C.J. (Caroline) Bax, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVOG (voorzitter)

- Dr. J.L. (Jantien) van der Heyden, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Bernhoven ziekenhuis te Uden, NVOG

- Dr. M.M. (Martina) Porath, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Maxima Medisch Centrum te Veldhoven, NVOG

- Dr. S.M.T.A. (Simone) Goossens, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Maxima Medisch Centrum te Veldhoven, NVOG

- Dr. I.H. (Ingeborg) Linskens, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVOG

- Dr. F. (Fatima) Hammiche, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVOG

- Prof. dr. C.A.J. (Catherijne) Knibbe, ziekenhuisapotheker-klinisch farmacoloog, werkzaam in het St Antonius ziekenhuis Nieuwegein & Utrecht, en hoogleraar, werkzaam bij LACDR, Universiteit Leiden, NVKFB

- Dr. R.C. (Rebecca) Painter, gynaecoloog, associate professor, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVOG

- Drs. E.C.J. (Evelyn) Verheijen, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Annaziekenhuis te Geldrop, NVOG

- J. (Jolein) Vernooij, klinisch verloskundige, physician assistant in opleiding, werkzaam in het OLVG locatie Oost te Amsterdam, KNOV

- J. (José) Hollander-Boer, verloskundige, werkzaam bij Academie Verloskunde Amsterdam Groningen, KNOV, clusterwerkgroep

- J. (Jacobien) Wagemaker, projectleider, werkzaam in het Maasstadziekenhuis te Rotterdam, Care4Neo

- I. (Ilse) van Ee, patiëntenvertegenwoordiger, werkzaam bij de Patiëntenfederatie te Utrecht, PFN

- Dr. M.C. (Martine) Bouw-Schaapveld, kinderarts-neonatoloog, werkzaam in het Deventer ziekenhuis te Deventer, NVK

- Dr. M. (Mireille) van Westreenen, arts-microbioloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC te Rotterdam, NVMM

- Dr. M.L. (Mark) van Zuylen, anesthesioloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVA

- Drs. I.C.M. (Ingrid) Beenakkers, anesthesioloog, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht te Utrecht, NVA

- Dr. S.V. (Steven) Koenen, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis te Tilburg, NVOG, lid stuurgroep

- Dr. J.J. (Hans) Duvekot, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC te Rotterdam, NVOG, lid stuurgroep

Meelezers

- Leden van de Otterlo-werkgroep (2021)

Met ondersteuning van

- Drs. Y. (Yvonne) Labeur, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. L. (Laura) Viester, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. J.H. (Hanneke) van der Lee, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Actie |

|

Bax* |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog Amsterdam UMC |

Gastvrouw Hospice Xenia Leiden (onbetaald) Lid NIPT consortium Voorzitter WG Otterlo NVOG Lid commissie kwaliteitsdocumenten NVOG Lid pijlerbestuur FMG NVOG Penningmeester WG Infectieziekten NVOG Lid werkgroep voorlichting en deskundigheidsbevordering prenatale screening RIVM Lid werkgroep implementatie scholing prenatale screening RIVM |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Beenakkers |

Anesthesioloog UMCU/WKZ |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Bouw-Schaapveld |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog, Deventer ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Duvekot |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Erasmus MC |

Directeur medisch advies en expertisebureau Duvekot, Ridderkerk, ZZP |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Galjaard |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Erasmus MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Goossens |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Maxima MC Veldhoven |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hammiche |

Gynaecoloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hollander-Boer |

Docent verloskunde Academie Verloskunde Amsterdam Groningen Verloskundige -> oproepcontract Verloskundige stadspraktijk Groningen (zelden) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Knibbe |

Ziekenhuisapotheker-klinisch farmacoloog, Sint Antonius ziekenhuis Nieuwegein & Utecht Hoogleraar individualized Drug Treamtment, LACDR, Universiteit Leiden |

Lid Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek, Den Haag (vacatiegelden) Gastaanstelling onderzoeker, Erasmus MC, Sophia Kinderziekenhuis, afdeling NICU (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Koenen |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis |

Incidenteel juridische expertise (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Linskens |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Painter |

Gynaecoloog, aandachtsgebied maternale ziekte, associate professor, Amsterdam UMC |

Voorzitter Special Interest Group NVOG ‘Zwangerschap en diabetes en obesitas’ (onbetaald) Lid Gezondheidsraad commissie ‘Voeding en zwangerschap’ (vacatiegelden naar werkgever) Lid richtlijncommissie ‘Chirurgische behandeling van obesitas’ (NVvH) (onbetaald) Lid namens NVOG bij RIVM commissie ‘Hielprikscreening’ (onbetaald) Voorzitter organiserend comité Congres ICGH 2019 (onbetaald) Clustercoördinator regio Noord-Holland NVOG Consortium 2.0 (onbetaald) Lid wetenschapscommissie Pijler obstetrie NVOG (onbetaald) Lid Koepel Wetenschap namens Pijler obstetrie Wetenschappelijk adviseur bij patiëntenvereniging 2EHG (hyperemesis gravidarum) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Porath |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Maxima Medisch Centrum |

lid NVOG werkgroep Otterlo (onbetaald) lid richtlijnwerkgroep extreme vroeggeboorte |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

van der Heyden |

Gynaecoloog, Bernhoven ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

van Ee |

Adviseur patiëntenbelang, Patiëntenfederatie |

Vrijwilliger Psoriasispatiënten Nederland, Coördinator patiëntenparticipatie en onderzoek en redactie lid centrale redactie (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

van Westreenen |

Arts-microbioloog, Erasmus MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

van Zuylen |

Anesthesioloog in opleiding, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Verheijen |

Gynaecoloog Maasziekenhuis Pantein Boxmeer |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vernooij |

Klinisch verloskundige, physician assistant in opleiding, OLVG locatie Oost |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Wagemaker |

Projectleider PATH Maasstadziekenhuis, ZZP adviseur, trainer, onderzoeker Family Centered en Single Room Care |

Vrijwilliger Care4Neo (soms vacatiegelden) VrijwilligerV&VN kinderverpleegkunde (soms vacatiegelden) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Labeur |

Junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut FMS |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Viester |

Adviseur, Kennisinstituut FMS |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

van der Lee |

Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut FMS |

Onderzoeker, AmsterdamUMC |

Geen |

Geen actie |

*Voorzitter werkgroep

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door vertegenwoordigers van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en Care4Neo af te vaardigen in de clusterwerkgroep. De conceptrichtlijn werd tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan de betrokken patiëntenverenigingen.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodules zijn opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten. Tevens is er een knelpunteninventarisatie gedaan in november 2018 middels een Invitational conference.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de voorzitter en de adviseur concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Deze zijn met de werkgroep besproken waarna de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen heeft vastgesteld. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep per uitgangsvraag welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodules worden aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren worden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren worden de conceptrichtlijnmodules aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodules worden aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas, T., Merglen, A., Heen, A. F., Kristiansen, A., Neumann, I., Brito, J. P., ... & Guyatt, G. H. (2017). UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ open, 7(11).

Alonso-Coello, P., Schünemann, H. J., Moberg, J., Brignardello-Petersen, R., Akl, E. A., Davoli, M., ... & Morelli, A. (2018). GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. Gaceta sanitaria, 32(2), 166-e1.

Brouwers, M. C., Kho, M. E., Browman, G. P., Burgers, J. S., Cluzeau, F., Feder, G., ... & Littlejohns, P. (2010). AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Cmaj, 182(18), E839-E842.

Hultcrantz, M., Rind, D., Akl, E. A., Treweek, S., Mustafa, R. A., Iorio, A., ... & Katikireddi, S. V. (2017). The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 87, 4-13.

Richtlijnen, A., & Kwaliteit, R. (2012). Medisch specialistische richtlijnen 2.0. Utrecht: Orde van Medisch Specialisten.

http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Neumann, I., Santesso, N., Akl, E. A., Rind, D. M., Vandvik, P. O., Alonso-Coello, P., ... & Guyatt, G. H. (2016). A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 72, 45-55.

Schünemann, H., Brożek, J., Guyatt, G., & Oxman, A. (2013). GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from guidelinedevelopment. org/handbook. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann, H. J., Oxman, A. D., Brozek, J., Glasziou, P., Jaeschke, R., Vist, G. E., ... & Bossuyt, P. (2008). Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. Bmj, 336(7653), 1106-1110.

Wessels, M., Hielkema, L., & van der Weijden, T. (2016). How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(4), 320.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Embase

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medline (OVID)

|

1 exp Fetal Membranes, Premature Rupture/ or pprom.ti,ab,kf. or 'preterm prom'.ti,ab,kf. or 'preterm premature rupture of'.ti,ab,kf. or ((preterm or midtrimester or 'second trimester' or 'mid trimester') adj3 ('rupture of membrane*' or 'rupture of the membrane*' or 'amnion rupture' or 'membrane* rupture*' or 'rupture* membrane*')).ti,ab,kf. (8807) 2 exp Labor, Induced/ or ((labo*r or delivery or parturition) adj3 (induc* or stimulat* or immediate)).ti,ab,kf. or priming.ti,ab,kf. or planned early deliver*.ti,ab,kf. or iol.ti,ab,kf. (66325) 3 1 and 2 (684) 4 limit 3 to (english language and yr="2000 -Current") (366) 5 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (456826) 6 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (2007340) 7 4 and 5 (37) 8 (4 and 6) not 7 (83) 9 7 or 8 (120) |