bDMARDs

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de effectiviteit van biological (b)DMARDs bij reuscelarteriitis?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg tocilizumab voor reuscelarteriitis, in combinatie met glucocorticoïd-afbouw, bij patiënten met:

- een opvlamming van de ziekte na onvoldoende respons op maximaal getolereerde dosis methotrexaat of bij contra-indicaties voor of bijwerkingen van methotrexaat.

- een hoog risico op, of reeds optreden van glucocorticoïd toxiciteit, na onvoldoende respons op maximaal getolereerde dosis methotrexaat of bij contra-indicaties voor of bijwerkingen van methotrexaat.

Indien onvoldoende ervaring met tocilizumab, overleg met een collega met expertise over het opstarten en monitoren van de behandeling.

Er wordt geen aanbeveling geformuleerd voor de behandeling van reuscelarteriitis met sirukumab en abatacept vanwege nog onvoldoende bewijs.

Behandel reuscelarteriitis niet met anti-TNF, aangezien dit niet effectief is bij reuscelarteriitis.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De BSR-richtlijn beschrijft de vergelijking bDMARDs plus glucocorticoïden (GC) versus alleen GC o.b.v. enkele studies. Twee studies laten het effect van de bDMARD tocilizumab (TCZ) zien. Het bevorderlijke effect van TCZ wordt gezien op alle uitkomstmaten, d.w.z. ziekteactiviteit, cumulatieve dosering GC en bijwerkingen. De BSR-richtlijn concludeert dat TCZ plus GC minder kans op bijwerkingen geeft dan alleen GC (RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.41, 1.00), QoE+++). De bewijskracht voor de verschillende uitkomstmaten is hoog tot matig (Mackie, 2020).

Eén andere studie met een kleine omvang van de studiepopulatie laat het effect van de bDMARD abatacept zien. Er werd een significant verschil gevonden op de primaire uitkomst maat ‘Tijd tot opvlamming’ in het voordeel van abatacept, maar het percentage in remissie op 12 maanden was dit niet. Deze studie werd gegradeerd met een lage bewijskracht. De overall bewijskracht (o.b.v. alle uitkostmaten) is laag.

Naast deze bDMARDs heeft de BSR-richtlijn ook enkele studies naar de effectiviteit van TNF-remmers bekeken. Op basis van het bewijs concludeert de richtlijn dat TNF-remmers niet aanbevolen moeten worden voor een behandeling bij patiënten met reuscelarteriitis (RCA) (Mackie, 2020).

In de update, gedaan voor deze richtlijn, van de samenvatting van de literatuur vanaf 2018 zijn 3 artikelen beschreven. Twee artikelen betreffen een vergelijking met de bDMARD TCZ (Stone, 2021; Strand, 2019) en één artikel de vergelijking met de bDMARD sirukumab (Schmidt, 2020). De studie van Schmidt (2020) laat zien dat behandeling met sirukumab met GC mogelijk effectiever is bij patiënten met RCA dan behandeling met alleen GC. Echter bevat de studie slechts een kleine populatie waardoor de algehele bewijskracht zeer laag is. Bijwerkingen lijken meer voor te komen in de groep behandeld met sirukumab en prednisolon t.o.v. de groep behandeld met alleen prednisolon. De kwaliteit van deze bevinding is echter matig t.g.v. bias en te weinig precisie. Sirukumab is op dit moment niet geregistreerd voor gebruik in Nederland.

De studies van Stone (2021) en Strand (2019) ondersteunen het resultaat van de oorspronkelijke GiACTA studie (Stone 2017) dat behandeling met TCZ plus GC een effectievere behandeling is bij patiënten met RCA dan alleen GC. De overall bewijskracht van de extensie studie en post-hoc analyse meegenomen in deze richtlijn zijn minder sterk dan de oorspronkelijke studie ten gevolge van het openlabel en post-hoc karakter van de studies. Daarnaast is er in deze studies geen melding gemaakt over bijwerkingen. TCZ is op dit moment geregistreerd in Nederland voor de behandeling van RCA.

Vlak voor het finaliseren van de richtlijn is er een ongecontroleerde openlabel proof-of-concept studie gepubliceerd waarin patiënten met een opvlamming van RCA onder behandeling met GC werden behandeld met baricitib. Het doel van deze studie was om ‘safety’ te bekijken en een eerste inschatting van effectiviteit te kunnen maken. Er waren 15 patiënten geïncludeerd die allen werden behandeld met baricitinib 4mg/dag en daarnaast een versneld GC afbouwschema. Na 52 weken werden 14 patiënten nog behandeld met baricitib en waren in remissie. Dertien van hen hadden geen GC behandeling meer. Er was 1 patiënt uitgevallen door een bijwerking. Aangezien dit geen gecontroleerde studie betreft is er verder onderzoek nodig om tot een aanbeveling te komen hierover, maar het lijkt een hoopvol resultaat (Koster, 2022).

Samenvattend, kan op basis van de adviezen in de BSR-richtlijn en de geïncludeerde studies bij de literatuur update tot 2021 geconcludeerd worden dat TCZ een plaats heeft in de behandeling bij RCA op het moment van een opvlamming waarvoor ophoging van GC nodig is, dan wel bij het optreden van bijwerkingen of een hoog risicoprofiel voor het optreden van bijwerkingen t.g.v. GC (bijvoorbeeld co morbiditeit). Nadelig zijn de kosten verbonden aan deze behandeling.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Patiënten geven vaak in de spreekkamer aan dat zij liever geen, of zo min mogelijk GC willen gebruiken, dus het beschikbaar komen van meer behandel alternatieven is wenselijk. Met name de groep waarbij de bekende bijwerkingen van GC veel invloed hebben door hun co-morbiditeit kunnen erg gebaat zijn bij GC-sparende medicatie, onder andere patiënten met diabetes mellitus, osteoporose. Ook patiënten bij wie er al andere risicofactoren zijn om deze aandoeningen te ontwikkelen kan een lagere dosis GC of sneller stoppen met GC mogelijk verder ontwikkelen van deze ziekten voorkomen. Zoals hierboven al genoemd, zijn er op dit moment alleen studies die ondersteunen dat TCZ op deze plaats ingezet kan worden. Voor andere bDMARDs is nog onvoldoende ondersteuning.

Het doel van de behandeling met TCZ voor de patiënt is om de RCA zo snel mogelijk onder controle te krijgen met zo min mogelijk kans op bijwerkingen en daarnaast het sneller reduceren, liefst zelfs stoppen, van de GC. In de studie van Stone (2017) werd ook een sneller GC-afbouwschema toegepast waarbij in 26 weken patiënten op 0 mg uitkwamen. In deze richtlijn is ook voorbeeld van een versneld GC afbouwschema opgenomen, wat gebaseerd is op deze studie (zie module Glucocorticoïden en het Afbouwschema).

De belasting voor de patiënt die bij TCZ komt kijken bestaat uit het zelf leren toedienen, of anders laten toedienen, van de injecties en de eventuele bijwerkingen van TCZ in deze relatief oudere patiëntenpopulatie (onder andere infecties, diverticulitis, bloedbeeldafwijkingen, hypercholesterolemie). Belangrijk is dat TCZ in het algemeen een normalisatie van BSE en CRP geeft, waardoor deze niet meer geschikt zijn als biomarkers voor de RCA, maar ook niet meer voor andere ziekten, zoals infecties. Het is aan te raden om patiënten hierover goed in te lichten.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De directe geneesmiddelkosten van TCZ liggen veel hoger dan GC of csDMARDs. Het zou echter kunnen zijn dat TCZ wel kosten effectiever is dan GC of csDMARDs. Behandeling met GC is in de meerderheid van de RCA-patiënten initieel effectief, maar is vaak langdurig, gaat vaak gepaard met GC-gerelateerde bijwerkingen/complicaties en bij het merendeel van de patiënten treedt een recidief op na initiële remissie. RCA kan ernstige complicaties (onder andere visusverlies, herseninfarct, aneurysmata) geven, met aanzienlijk zorggebruik tot gevolg en de bijbehorende kosten als gevolg voor de samenleving. Ook GC-geïnduceerde bijwerkingen kunnen extra kosten met zich meebrengen. Op dit moment is in de literatuur nog geen ondersteuning voor superieure kosteneffectiviteit van TCZ boven alleen GC behandeling. De BSR-richtlijn beschrijft wel dat er is aangedragen dat een GC-sparende therapie zoals TCZ kosten-effectiever zou kunnen zijn in de volgende subgroepen; 1) RCA-patiënten die ophogen van GC therapie nodig hebben vanwege terugval van de ziekte, en 2) RCA-patiënten met een hoog risico op bijwerkingen van verdere GC behandeling (bijvoorbeeld op basis van co-morbiditeitsprofiel of andere risicofactoren voor GC-gerelateerde toxiciteit: bijvoorbeeld neuro-psychiatrische GC-gerelateerde bijwerkingen, eerdere fragiliteitsfracturen of moeilijk te beheersen diabetes mellitus). In Nederland is TCZ geregistreerd voor RCA, er zijn geen verdere consequenties aan verbonden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is geen kwantitatief of kwalitatief onderzoek gedaan naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van de interventies bij RCA, maar TCZ wordt ook bij andere ziekten voorgeschreven in Nederland, zoals onder andere reumatoïde artritis en ook juveniele idiopatische artritis. Bij deze groepen is uit onderzoek en in de praktijk gebleken dat de behandeling goed verdragen wordt. Behandelaars die TCZ vaker voorschrijven hebben al ervaring opgedaan met logistiek omtrent spuitinstructies, controle van mogelijke bijwerkingen en uitleg van risico’s bij TCZ. De werkgroep beveelt aan dat het voorschrijven van TCZ bij RCA verricht wordt door behandelaars met ervaring met het behandelen van RCA en bij voorkeur ook ervaring met TCZ. Het kan alleen worden verstrekt door een ziekenhuisapotheek. TCZ is op dit moment geregistreerd voor de behandeling van RCA en wordt vergoed.

De behandeling wordt bij voorkeur subcutaan gegeven bij RCA, dosering 1 keer per week 162mg s.c.. Er is data over intraveneus gebruik bij RCA, en dit leek minder effectief dan subcutaan. Het is belangrijk dat bijwerkingen van TCZ gemonitord worden (o.a. leukocyten, cholesterol spectrum) en dat er goede instructies gegeven worden hoe te handelen bij bijwerkingen, zoals onder andere infecties. Vóór dat patiënt kan starten moet (latente) tuberculose uitgesloten worden volgens de landelijke richtlijn. Zodra TCZ gestart is volstaat een sneller GC-afbouwschema, hierbij kan het schema elders in deze richtlijn dienen als voorbeeld.

De behandeling is voor alle patiënten toegankelijk, er is geen indicatie dat er ongelijkheid tot deze behandeling is tussen patiënten.

Rationale van de aanbeveling:

RCA is een ernstige aandoening, met mogelijk ook invaliderende complicaties. Behandeling bestaat nu uit GC, maar dit gaat gepaard met frequente en soms ook ernstige bijwerkingen. Ook is het door comorbiditeit soms een onwenselijke behandeling. Daarnaast kan tijdens het GC afbouwen een opvlamming van de ziekte optreden. Er zijn meerdere bDMARDs onderzocht als GC-sparende medicatie bij RCA. Anti-TNF laten geen effect zien bij RCA-patiënten in onderzoek van hoge kwaliteit. Voor bDMARDs zoals abatacept en sirukumab is het overall bewijs op dit moment nog onvoldoende. Voor TCZ is wel door middel van kwalitatief hoogstaand onderzoek vastgesteld dat het effectief is op ziekteactiviteit, daling van GC gebruik en bijwerkingen. Dit is terug te zien in de BSR-richtlijn en de update van de literatuur. Kanttekening hierbij is dat het effect van TCZ bij patiënten met langer dan 4 jaar GC voor RCA nog onvoldoende onderzocht is en alsmede de optimale behandelduur in de klinische praktijk. Verder zijn de relatief hoge kosten, de normalisatie van de BSE en CRP waardoor deze niet meer geschikt zijn als biomarkers, de mogelijke bijwerkingen en het potentiële aantal te behandelen patiënten factoren die een weloverwogen plaatsbepaling van dit middel voor de indicatie RCA noodzakelijk maken. Derhalve verdient het de voorkeursbehandeling met TCZ te laten verrichten door behandelaars met ervaring met behandelen van RCA en TCZ. Verder is het advies TCZ pas in te zetten als MTX in een optimale getolereerde dosis van maximaal 25mg/week faalt of bijwerkingen veroorzaakt. Op basis van bovengenoemde overwegingen concludeert de werkgroep dat er een indicatie voor TCZ is bij de behandeling van RCA indien er een indicatie is voor een GC-sparend middel na onvoldoende respons op optimaal gedoseerde MTX of bij contra-indicaties voor -dan wel bijwerkingen van MTX. Na start kan een sneller GC-afbouwschema doorlopen worden (zie module Glucocorticoïden en het Afbouwschema). Indien de behandeling met TCZ faalt door ineffectiviteit of bijwerkingen kan in overleg met een centrum met expertise gekeken worden naar andere mogelijkheden. Verder wijst de werkgroep op de recente studie gepubliceerd over baricitinib en andere studies die nu lopen waaruit in de nabije toekomst voor patiënten die falen op TCZ mogelijk vervolg behandelopties blijken, onder andere studies naar het effect van andere JAK/STAT remmers en mavrilimumab (Sandovici, 2022). Hierover kunnen nu nog geen aanbevelingen gedaan worden. Noot: deze behandelingen worden niet door de huisartsen voorgeschreven.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Behandeling van reuscelarteriitis (RCA) bestaat nog steeds voornamelijk uit glucocorticoïden (GC). Ondanks dat GC bij veel patiënten effectief zijn in het bereiken van remissie, geldt dit niet voor alle patiënten. Bovendien heeft een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten ook bijwerkingen van GC. Daarnaast krijgt ongeveer 75% van de patiënten met RCA een opvlamming van de ziekte ondanks behandeling met GC. GC-sparende dan wel alternatieve behandeling voor RCA is hierdoor noodzakelijk. Momenteel is er geen eenduidige behandelstrategie bij patiënten met RCA in Nederlandse richtlijnen. In de NHG-standaard ‘Polymyalgia rheumatica en arteriitis temporalis’ staat een behandelschema prednisolon (waaronder afbouwschema) bij PMR opgenomen en een initiële behandeldosis in geval van RCA. Een recente richtlijn van ‘British Society for Rheumatology’ (BSR) geeft een aanbeveling voor het toevoegen van bDMARDs bij RCA in geval van contra-indicaties, GC-ineffectiviteit of opvlammingen van RCA onder GC (Mackie, 2020). Deze aanbeveling wordt gedaan op basis van literatuur gezocht tot en met juni 2018.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Moderate GRADE |

Treatment with TCZ plus GC, compared to GC alone improves disease activity (i.e., (sustained) remission at week 52 and week 104) in patients with GCA.

Sources: Stone, 2021.Stone, 2017. |

|

Low GRADE |

Evidence suggests that treatment with TCZ plus GC, compared to GC alone reduces the cumulative GC doses in patients with GCA between week 52 and 104.

Sources: Stone, 2021. |

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown what the longer term effect of treatment with TCZ plus GC, compared to GC alone in patients with GCA is with respect to adverse events. This outcome measures were not studied in the included studies in this update.

Sources: none. |

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown what the effect of treatment with TCZ plus GC, compared to GC alone in patients with GCA is with respect to the outcome measure patient reported outcomes. No effect estimates could be calculated.

Sources: Strand, 2019 |

Samenvatting literatuur

First, we will describe the results of the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) guideline, published in 2020.

Then we will describe any new studies results we found in our current update.

BSR-guideline

Tocilizumab (TCZ) was approved for GCA by the US and European regulatory authorities in 2017 based on the results of two randomized controlled trials of addition of 1 year TCZ, or placebo, to tapering GC therapy (Villiger, 2016; Stone, 2017).

In the larger of these trials (GiACTA trial, Stone, 2017), both patients with new GCA and patients with relapsing GCA were included. Patients with relapsing GCA had to have been treated for GCA for no more than 4 years prior to enrolment. TCZ was combined with a standardized prednisolone taper according to which prednisolone cessation occurred at 6 months. Patients receiving placebo were treated with one of two alternative prednisolone tapering schedules, by which prednisolone cessation was achieved at either 6 months or 1 year if the patient remained relapse-free. If a patient relapsed during the study, prednisolone therapy was escalated according to investigator discretion.

The primary endpoint (sustained remission at 1 year plus adherence to the tapering protocol, using a definition of remission incorporating CRP levels) was achieved in 56% of patients treated with weekly subcutaneous TCZ, and in 53% of those treated every other week. In the placebo group, sustained remission at 1 year was achieved in 14% of that tapering prednisolone over 6 months and 18% of that tapering prednisolone over 1 year. Comparing weekly TCZ with placebo plus 6-month GC taper, relative risk (RR) for sustained remission was 4.0 (95 % CI 1.97 to 8.12, QoE++++). Comparing with other groups revealed similar results, with RR 3.01 - 3.79, QoE ++++. Patients in the TCZ treatment arm also showed a higher rate of sustained remission using a modified definition of sustained remission that did not require CRP normalization (weekly TCZ compared with placebo plus 6-month GC taper: RR 2.95, 95% CI 1.66 - 5.26, QoE +++, for other comparisons RR 1.65 – 2.76, QoE+++). In both this trial and in the smaller single-centre trial (Villiger, 2016), an increase in relapse-free survival at 1 year (RR 3.57, 95% CI 2.29 - 5.55, QoE ++++) was seen, and a reduction in 1-year cumulative GC dose was observed in the TCZ treatment arms (mean difference 1434 mg lower (95% CI 2148 mg lower to 720 mg lower) in the weekly TCZ group compared to placebo plus 6 month tapering of GC, QoE++++; mean difference from 1434mg to 1956 mg in other comparisons, QoE++++). Patient-reported outcomes were encouraging although these were assessed using generic measures, since no disease-specific patient-reported outcome has yet been fully validated for GCA. Of note, although GC-sparing efficacy was demonstrated, these studies were not designed or powered to demonstrate a reduction in GC-related adverse events.

TCZ has only been approved for weekly subcutaneous use, although it has also been studied in intravenous formulation (Villiger, 2016). In the multicentre RCT (Stone, 2017) one of the treatment arms received subcutaneous TCZ every 2 weeks, rather than weekly; patients in this treatment arm also reached the primary endpoint, although it appeared to be less efficacious in relapsing patients. The trials in GCA have not demonstrated an increased risk of adverse events with TCZ (Villiger, 2016; Stone, 2017); pooling of data from both trials indicated a lower rate of serious adverse events in patients treated with TCZ than those treated with placebo (RR 0.64, 95%CI 0.41 to 1.00, QoE+++).

Abatacept was studied in a single, small trial (Langford, 2017). All patients received abatacept initially in addition to GC therapy. Those achieving remission were randomized in week 12 to either continue the drug or to switch to placebo. Time-to-relapse analysis, which was the primary endpoint, significantly favored abatacept. A post-hoc analysis to compare the proportion of patients in remission at 12 months did not show a significant difference between the treatment arms (RR 1.50 CI 0.71 - 3.17, QoE++), likely due to the small size of the study. At present abatacept is not approved for treatment of GCA.

TNF inhibitors have been studied in two randomized controlled trials (Hoffman, 2007; Seror, 2014), both of which showed inefficacy but an increased incidence of infections. A third, small RCT of etanercept for GCA (Martinez-Taboada, 2008) did not fulfil the inclusion criteria for the literature review; although it showed a lower cumulative GC dose in the etanercept arm, this trial failed to show a significant result for its primary outcome. Based on this evidence, TNF inhibitors cannot be recommended for GCA.

Update

Description of studies

Schmidt (2020) performed a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Sirukumab (i.e., a selective, high-affinity human interleukin (IL)-6 monoclonal antibody), compared to prednisolone in the treatment of GCA. Patients eligible for inclusion were randomized to Sirukumab 100 mg every 2 weeks plus 6-month or 3-month prednisolone taper, sirukumab 50 mg every 4 weeks plus 6-month prednisolone taper, or placebo every 2 weeks plus 6-month or 12-month prednisolone taper. The number of patients in sustained remission (defined as achievement of all the following: remission (absence of clinical signs and symptoms of GCA and normalization of ESR [<30 mm/h] and CRP [<1 mg/dl]) by week 12; absence of disease flare (recurrence of symptoms attributable to active GCA with or without elevations in ESR/CRP) following remission at week 12 through week 52; completion of assigned prednisolone taper protocol; no requirement for rescue therapy at any time through week 52) was the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints were disease flare, cumulative dose prednisolone and adverse events. In total 161 patients were randomized to treatment with 1) sirukumab 100 mg every 2 weeks plus 6-month (n=42) or 3-month prednisolone taper (n=39), sirukumab 50 mg every 4 weeks plus 6-month prednisolone taper(n=26), or placebo every 2 weeks plus 6-month (n=27) or 12-month prednisolone taper (n=27). The study was prematurely terminated because of the sponsor’s decision to stop the further development of sirukumab, thus only 17% completed week 52. As expected, no differences were shown at baseline between the groups. The mean age was 70 years, and 77% of the included patients were female. Although, during the trial many patients were lost-to-follow up due to study termination or early withdrawal. This was frequent in all groups (range 79% to 89%). Therefore, only a limited number of patients were included in the population for analysis regarding efficacy outcomes.

Stone (2021) performed an open-label extension study of the GiACTA trial. In the GiACTA trial 251 patients were randomly assigned to the following treatment groups (2:1:1:1); subcutaneous TCZ (an interleukin-6 receptor [IL-6R] antagonist; 162 mg) once a week or every other week, combined with a 26-week prednisolone taper, or placebo combined with a prednisolone taper over a period of either 26 weeks or 52 weeks. After 52 weeks patients were eligible to participate in de open-label extension study. During this study (i.e., week 52 to week 104) treatment was according to the decision of the treating physician. The outcomes of interest were clinical remission (defined as absence of relapse as determined by the investigator) at week 52, maintained clinical remission (defined as the absence of relapse throughout part two after the achievement of clinical remission at the end of part one) at week 104, cumulative prednisolone dose, and adverse events. In total 215/251 (86%) patients participated in the open label extension study. During the trial 8% of them withdrew from the trial, without being different in the initial treatment arms. The open label design of this study is a limitation. Besides, not all outcomes of interest (i.e., adverse events) are reported per initial treatment strategy.

Strand (2019) performed a post-hoc analysis of the GiACTA trial. As described above, patients were randomized to four different treatment arms. The current study excluded the following treatment arm; subcutaneous TCZ (162 mg) once every other week. The primary outcome of this study at week 52 was health related quality of life, measured with SF-36 PDC and MCS and total scores, PtGA and FACIT-Fatigue. In total three treatments arms were of interest; subcutaneous TCZ (162 mg) once a week (n=100) combined with a 26-week prednisolone taper, or placebo combined with a prednisolone taper over a period of either 26 weeks (n=50) or 52 weeks (n=51). No differences were shown at baseline between de treatment arms. The mean age was 69 years, and approximately 76% of them were female. A limitation of the current study is the post-hoc design. Although the main study is described in the BSR-guideline (Mackie, 2020).

Results

Data of the additional literature is described per outcome measure and per comparison (i.e., sirukumab and TCZ). If possible, data will be pooled.

Sirukumab vs. prednisolone

1. Sustained remission

Schmidt (2020) reported that sustained remission at week 52 was achieved in 3/17 (18%) patients in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 6-month prednisolone arm, 2/13 (15%) in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 3-month prednisolone arm, 1/9 (11%) in the initial sirukumab 50mg q4w + 6-month prednisolone arm, and not in patients receiving only prednisolone during 6- or 12 months. The treatment arms were pooled as followed; Schmidt, 2020a, Sirukumab 100mg q2w + 6-month prednisolone vs. the initial 12-month prednisolone arm; Schmidt, 2020b, Sirukumab 50mg q2w + 6-month prednisolone vs. the initial 6-month prednisolone arm. The pooled estimated resulted in a relative risk (RR) of 3.11 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.38 to 67.95), suggesting that achieving sustained remission at week 52 is more common in the sirukumab plus prednisolone arms compared to only prednisolone. The risk difference was 0.15 (-0.03 to 0.33).

2. Remission

Schmidt (2020) reported that remission at 12 weeks was achieved in 13/17 (76%) patients in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 6-month prednisolone arm, 7/13 (54%) in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 3-month prednisolone arm, 8/9 (89%) in the initial sirukumab 50mg q4w + 6-month prednisolone arm, in 5/9 (56%) in the initial 6-month prednisolone arm, and 5/7 (71%) of the patients in the 12-month prednisolone arm. The pooled estimated resulted in an RR of 1.27 (95%CI 0.84 to 1.93), suggesting that achieving remission at week 12 is more common in the sirukumab plus prednisolone arms, compared to the only prednisolone arms. The risk difference was 0.19 (-0.08 to 0.47).

3. Presence of flare

The presence of flare from week 12 to week 52 was observed by Schmidt (2020) in 9/17 (53%) patients in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 6-month prednisolone arm, 9/13 (69%) in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 3-month prednisolone arm, 5/9 (56%) in the initial Sirukumab 50mg q4w + 6-month prednisolone arm, in 8/9 (89%) in the initial 6-month prednisolone arm, and 5/7 (71%) of the patients receiving prednisolone during 12 months arm. The pooled estimated resulted in an RR of 0.68 (95%CI 0.43 to 1.07), suggesting that presence of flare from week 12 to week 52 is less common in the sirukumab plus prednisolone arms compared to only prednisolone, see Figure 1. The risk difference was -0.26 (-0.54 to 0.02).

4. Cumulative GC doses

Schmidt (2020) reported the mean (SD) cumulative GC doses in mg at week 52. This dose in mg was in 2974 (2697) in 11 patients of the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 6-month prednisolone arm, 2417 (2085) in 10 patients of the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 3-month prednisolone arm, 2556 (1363) in 6 patients of the initial sirukumab 50mg q4w + 6-month prednisolone arm, 3157 (1988) in 7 patients of the initial 6-month prednisolone arm, and 3603 (1478) in 6 patients of the initial 12-month prednisolone arm.

The pooled estimated resulted in a SMD of -0.28 (95%CI -1.02 to 0.46), suggesting that the cumulative GC doses was lower in the sirukumab plus prednisolone arms, compared to the only prednisolone arms, see Figure 2.

5. Adverse events

This outcome was reported for treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE, including; any adverse event (AE) from first dose to 16 weeks post last dose), and adverse events of special interest (AESI, including; GC-related events, cytopenia, gastrointestinal perforation, injection site and hypersensitivity reactions, elevated lipids, abnormal liver function tests, malignancies, blindness, serious and opportunistic infections, severe disease flares, limb claudication, and major adverse cardiovascular events) in the study of Schmidt (2020).

5.1 Any adverse event (TEAE)

Any AE was observed in 41/42 (98%) patients in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 6-month prednisolone arm, 36/39 (92%) in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 3-month prednisolone arm, 25/26 (96%) in the initial sirukumab 50mg q4w + 6-month prednisolone arm, in 26/27 (96%) in the initial 6-month prednisolone arm, and 24/27 (89%) of the patients in the 12-month prednisolone arm (Schmidt, 2020). This was leading to discontinuation of subcutaneous sirukumab or placebo in 5/42 (12%), 8/39 (21%), 3/26 (12%), 3/27 (10%), and 2/27 (7%), in the sirukumab 100 mg every 2 weeks plus 6-month or 3-month prednisolone taper, sirukumab 50 mg every 4 weeks plus 6-month prednisolone taper, or placebo every 2 weeks plus 6-month or 12-month prednisolone taper treatment arms, respectively.

The pooled estimated resulted in an RR of 1.04 (95%CI 0.94 to 1.27), suggesting that the occurrence of any AE is more common in the sirukumab+prednisolone arms, compared to the only prednisolone arms, see Figure 3. The risk difference was 0.04 (-0.05 to 0.13).

5.2 AESI

An AESI observed in 30/42 (71%) patients in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 6-month prednisolone arm, 28/39 (72%) in the initial sirukumab 100mg q2w + 3-month prednisolone arm, 23/26 (89%) in the initial sirukumab 50mg q4w + 6-month prednisolone arm, in 15/27 (56%) in the initial 6-month prednisolone arm, and 15/27 (56%) of the patients in the 12-month prednisolone arm (Schmidt, 2020).

The pooled estimated resulted in an RR of 1.44 (95%CI 1.10 to 1.89), suggesting that the occurrence of an AESI is more common in the Sirukumab+prednisolone arms, compared to the only prednisolone arms, see Figure 4. The risk difference was 0.25 (0.08 to 0.42).

6. Patient reported outcomes

This outcome was not reported in the study of Schmidt (2020).

Conclusions

Level of evidence of the literature

There are no judgements about the confidence in estimates of the effect or quality of evidence for the summary of literature of the BSR-guideline in the current module. Therefore, we refer to the BSR-guideline (Mackie, 2020).

Regarding the articles which are included in the update, the level of evidence (GRADE method) is determined per outcome measure and is based on results from RCTs and therefore starts at level “high”. Subsequently, the level of evidence was downgraded if there were relevant shortcomings in one of the several GRADE domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient reported outcomes could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measures were not studied in the included study.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disease activity (i.e., remission, sustained, remission, presence of flare) was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (2 levels, 95%CI of mean difference includes no significant effect (RR=1), no clinically relevant effect (RR 0.75-1.25), and relative low number of included patients).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cumulative glucocorticoid doses was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (2 levels, 95%CI of the mean difference includes no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5) and relative low number of included patients).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events (i.e., any AE, AESI) was downgraded by 3 levels because of applicability (bias due to indirectness as AESI were only of interest of Sirukumab) and imprecision (2 levels, 95%CI of mean difference includes no significant effect (RR=1), no clinically relevant effect (RR 0.75-1.25), and relative low number of included patients).

Conclusions

|

Low GRADE |

Evidence suggests that treatment with sirukumab plus GC, compared to GC alone slightly improves disease activity (i.e., remission, sustained, remission, presence of flare) in patients with GCA.

Sources: Schmidt, 2020. |

|

Low GRADE |

Evidence suggests that treatment with sirukumab plus GC, compared to GC alone slightly reduces the cumulative GC doses in patients with GCA.

Sources: Schmidt, 2020. |

|

Very low GRADE |

Evidence is uncertain about the effect of treatment with sirukumab plus GC, compared to GC alone on adverse events (i.e., any AE, AESI) in patients with GCA.

Sources: Schmidt, 2020. |

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown what the effect of treatment with sirukumab plus GC, compared to GC alone in patients with GCA is with respect to patient reported outcomes. This outcome measures was not studied in the included studies.

Sources: none. |

Tocilizumab vs. prednisolone

1. Sustained remission

Stone (2021) reported that sustained remission at week 52 was achieved in 26/49 (53%) patients in the initial TCZ every-other-week plus 26-week prednisolone arm, 56/100 (56%) of the patients in the initial TCZ-weekly plus 26-week prednisolone arm, 9/51 (18%) of the patients in the placebo plus 52-week prednisolone arm, and 7/50 (14%) of the patients in the placebo plus 26-week prednisolone arm (Stone, 2021).

The treatment arms were pooled as followed; Stone, 2021a, TCZ-weekly plus 26-week prednisolone vs. placebo plus 52-week prednisolone arm; Stone, 2021b, TCZ every-other-week plus 26-week prednisolone vs. placebo plus 26-week prednisolone arm.

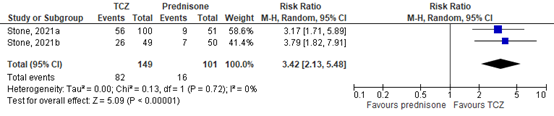

The pooled estimated resulted in an RR of 3.42 (95%CI 2.13 to 5.48), suggesting that achieving sustained remission at week 52 is more common in the TCZ plus prednisolone arms compared to only prednisolone, see Figure 2. The risk difference was 0.39 (0.28 to 0.50).

Figure 1. Forest plot sustained remission at week 52.

2. Remission

Stone (2021) reported that remission at week 52 was achieved in 36/40 (90%) patients in the initial TCZ every-other-week plus 26-week prednisolone arm, 81/85 (95%) of the patients in the initial TCZ-weekly plus 26-week prednisolone arm, 34/46 (74%) of the patients in the placebo plus 52-week prednisolone arm, and 33/44 (75%) of the patients in the placebo plus 26-week prednisolone arm.

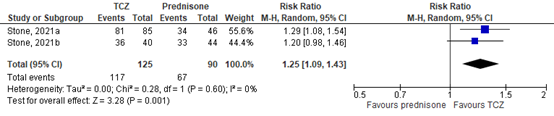

The pooled estimated resulted in an RR of 1.25 (95%CI 1.09 to 1.43), suggesting that achieving remission at week 52 is more common in the TCZ plus prednisolone arms, compared to the only prednisolone arms, see Figure 2. The risk difference was 0.19 (0.08 to 0.29).

Figure 2. Forest plot remission at week 52.

3. Presence of flare

This outcome was not reported in the study of Stone (2021) or Strand (2019).

4. Cumulative GC doses – week 104

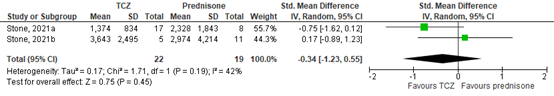

Stone (2021) reported the mean (SD) cumulative GC doses in mg at week 104. This dose in mg (i.e., between week 52 and 104) was in 3643 (2495) in 5 of the 22 patients receiving GC in the initial TCZ every-other-week plus 26-week prednisolone arm, 1374 (834) in 17 of the 47 patients receiving GC in the initial GC-weekly plus 26-week prednisolone arm, 2328 (1843) in 8 of the 13 patients receiving GC in the placebo plus 52-week prednisolone arm, and 2974 (4212) in 11 of the 13 patients receiving GC in the placebo plus 26-week prednisolone arm.

The pooled estimated resulted in a SMD of -0.34 (95%CI -1.23 to 0.55), suggesting that the cumulative GC doses was lower in the TCZ plus prednisolone arms, compared to the only prednisolone arms, see Figure 3.

Figure 3. Forest plot cumulative prednisolone dose – week 104.

5. Adverse events

This outcome was not reported in the study of Stone (2021) or Strand (2019) per initial treatment arm.

6. Patient reported outcomes

This outcome was reported in the study of Strand (2019) by using data of the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores and all eight individual domains (physical function, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, role emotional and mental health). Further Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA) was analyzed by visual analogue scale (VAS) and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue. Outcomes are described per instrument.

6.1 SF-36 PCS

Strand (2019) measured this outcome. The mean scores at baseline and at week 52 and change scores were reported. The mean score at baseline, week 52, and change was 43.10, 47.75, 4.18, respectively in patients treated with TCZ every week plus 26-weeks prednisolone, compared to 42.65, 41.52, -0.98, respectively in patients treated with placebo plus 26-weeks prednisolone. Since the standard deviation were not reported, it is not possible to calculate a mean difference with 95%CI. However, the change of 4.18 in the TCZ arm is a minimal clinical important difference. This was not shown for the placebo arm.

6.2 SF-36 MCS

Strand (2019) measured this outcome. The mean scores at baseline and at week 52 and change scores were reported. The mean score at baseline, week 52, and change was 42.77, 51.64, 8.10, respectively in patients treated with TCZ every week plus 26-weeks prednisolone, compared to 42.73, 49.36, 5.25, respectively in patients treated with placebo plus 26-weeks prednisolone. Since the standard deviation were not reported, it is not possible to calculate a mean difference with 95%CI. However, the changes of 8.20 in the TCZ arm and 5.25 in the placebo arm are minimal clinical important differences. Outcomes were not statistically significant different.

6.3 SF-6D- utility score

Strand (2019) measured this outcome. The mean scores at baseline and at week 52 and change scores were reported. The mean score at baseline, week 52, and change was 0.694, 0.775, 0.080, respectively in patients treated with TCZ every week plus 26-weeks prednisolone, compared to 0.686, 0.721, 0.034, respectively in patients treated with placebo plus 26-weeks prednisolone. Since the standard deviation were not reported, it is not possible to calculate a mean difference with 95%CI. However, the change of 0.80 in the TCZ arm is a minimal clinical important difference (i.e., 0.040). This was not shown for the placebo arm (change of 0.034).

6.4 PtGA

Strand (2019) measured this outcome. The mean change scores were reported. The mean change was -17.14 in patients treated with TCZ every week plus 26-weeks prednisolone, compared to -7.19 in patients treated with placebo plus 26-weeks prednisolone. Since the standard deviation were not reported, it is not possible to calculate a mean difference with 95%CI. However, the change of 17.14 in the TCZ arm is a minimal clinical important difference (i.e., 10.0). This was not shown for the placebo arm (change of -7.19).

6.5 FACIT-Fatigue

Strand (2019) measured this outcome. The mean change scores were reported. The mean change was 5.30 in patients treated with TCZ every week plus 26-weeks prednisolone, compared to 0.09 in patients treated with placebo plus 26-weeks prednisolone. Since the standard deviation were not reported, it is not possible to calculate a mean difference with 95%CI. However, the change of 5.30 in the TCZ arm is a minimal clinical important difference (i.e., 4.0). This was not shown for the placebo arm (change of 0.09).

Level of evidence of the literature

There are no judgements about the confidence in estimates of the effect or quality of evidence in this module for the summary of literature of the BSR-guideline. Therefore, we refer to the BSR-guideline (Mackie, 2020).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient reported outcomes could not be assessed with GRADE as no estimate of the effect could be provided.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure disease activity (i.e., remission, sustained, remission) was downgraded by 1 level because of imprecision (1 level, no clinically relevant effect (RR 0.75-1.25), or/and relative low number of included patients).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure cumulative GC doses was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (2 levels, 95%CI of the mean difference includes no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5) and relative low number of included patients).

Zoeken en selecteren

Een update van het literatuuronderzoek van de BSR-richtlijn is uitgevoerd voor de vraag.

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: In giant cell arteritis (GCA) (P), what is the effect of GC plus biological agents (I) on outcome (O) compared with GC alone (C)?

P: GCA patients

I: GC plus biological agents

C: GC alone

O: disease activity, disease relapse, diseases remission, sight loss and ischaemic complications, patient reported outcomes (VAS global wellbeing, morning stiffness (VAS and duration in minutes), quality of life, fatigue), inflammatory markers (e.g. ESR, CRP), imaging of shoulder/hip, duration of GC therapy, discontinuation of GC therapy, cumulative GC dose, lowest GC dose, adverse events, cardiovascular events, hospitalization, mortality.

The guideline development group considered sustained remission and GC free remission as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and time to relapse and cumulative GC dose as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions employed in the studies.

Search and select (Methods) - update

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched(updated) with relevant search terms from 01-01-2018 until 31-05-2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab

Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 135 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria;

- patients with GCA,

- comparison of treatment with GC plus bDMARDs, compared to treatment with only GC,

- at least one of the outcomes of interest (PICO) is reported.

Twelve studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, nine studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three studies were included.

Results - update

Three additional studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Hoffman GS, Cid MC, Rendt-Zagar KE, Merkel PA, Weyand CM, Stone JH, Salvarani C, Xu W, Visvanathan S, Rahman MU; Infliximab-GCA Study Group. Infliximab for maintenance of glucocorticosteroid-induced remission of giant cell arteritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007 May 1;146(9):621-30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-9-200705010-00004. PMID: 17470830.

- Koster MJ, Crowson CS, Giblon RE, Jaquith JM, Duarte-García A, Matteson EL, Weyand CM, Warrington KJ. Baricitinib for relapsing giant cell arteritis: a prospective open-label 52-week pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 Jun;81(6):861-867. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221961. Epub 2022 Feb 21. PMID: 35190385; PMCID: PMC9592156.

- Langford CA, Cuthbertson D, Ytterberg SR, Khalidi N, Monach PA, Carette S, Seo P, Moreland LW, Weisman M, Koening CL, Sreih AG, Spiera R, McAlear CA, Warrington KJ, Pagnoux C, McKinnon K, Forbess LJ, Hoffman GS, Borchin R, Krischer JP, Merkel PA; Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium. A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Abatacept (CTLA-4Ig) for the Treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Apr;69(4):837-845. doi: 10.1002/art.40044. Epub 2017 Mar 3. PMID: 28133925; PMCID: PMC5378642.

- Mackie SL, Dejaco C, Appenzeller S, Camellino D, Duftner C, Gonzalez-Chiappe S, Mahr A, Mukhtyar C, Reynolds G, de Souza AWS, Brouwer E, Bukhari M, Buttgereit F, Byrne D, Cid MC, Cimmino M, Direskeneli H, Gilbert K, Kermani TA, Khan A, Lanyon P, Luqmani R, Mallen C, Mason JC, Matteson EL, Merkel PA, Mollan S, Neill L, Sullivan EO, Sandovici M, Schmidt WA, Watts R, Whitlock M, Yacyshyn E, Ytterberg S, Dasgupta B. British Society for Rheumatology guideline on diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Mar 1;59(3):e1-e23. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez672. PMID: 31970405.

- Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, Carreño L, López-Longo J, Figueroa M, Belzunegui J, Mola EM, Bonilla G. A double-blind placebo controlled trial of etanercept in patients with giant cell arteritis and corticosteroid side effects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 May;67(5):625-30. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.082115. Epub 2007 Dec 17. PMID: 18086726.

- Sandovici M, van der Geest N, van Sleen Y, Brouwer E. Need and value of targeted immunosuppressive therapy in giant cell arteritis. RMD Open. 2022 Feb;8(1):e001652. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001652. Erratum in: RMD Open. 2022 Mar;8(1): PMID: 35149602; PMCID: PMC8845325.

- Seror R, Baron G, Hachulla E, Debandt M, Larroche C, Puéchal X, Maurier F, de Wazieres B, Quéméneur T, Ravaud P, Mariette X. Adalimumab for steroid sparing in patients with giant-cell arteritis: results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Dec;73(12):2074-81. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203586. Epub 2013 Jul 29. PMID: 23897775.

- Schmidt WA, Dasgupta B, Luqmani R, Unizony SH, Blockmans D, Lai Z, Kurrasch RH, Lazic I, Brown K, Rao R. A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Sirukumab in the Treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2020 Dec;7(4):793-810. doi: 10.1007/s40744-020-00227-2. Epub 2020 Aug 25. PMID: 32844378; PMCID: PMC7695797.

- Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, Klearman M, Aringer M, Blockmans D, Brouwer E, Cid MC, Dasgupta B, Rech J, Salvarani C, Schett G, Schulze-Koops H, Spiera R, Unizony SH, Collinson N. Trial of Tocilizumab in Giant-Cell Arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 27;377(4):317-328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613849. PMID: 28745999.

- Stone, J. H., Han, J., Aringer, M., Blockmans, D., Brouwer, E., Cid, M. C., ... & Bao, M. (2021). Long-term effect of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: open-label extension phase of the Giant Cell Arteritis Actemra (GiACTA) trial. The Lancet Rheumatology, 3(5), e328-e336.

- Strand V, Dimonaco S, Tuckwell K, Klearman M, Collinson N, Stone JH. Health-related quality of life in patients with giant cell arteritis treated with tocilizumab in a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019 Feb 20;21(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1837-7. PMID: 30786937; PMCID: PMC6381622.

- Villiger PM, Adler S, Kuchen S, Wermelinger F, Dan D, Fiege V, Bütikofer L, Seitz M, Reichenbach S. Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016 May 7;387(10031):1921-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00560-2. Epub 2016 Mar 4. PMID: 26952547.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: In giant cell arteritis (GCA) (P), what is the effect of glucocorticoids plus biological agents (I) on outcome (O) compared with glucocorticoids alone (C)?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Schmidt, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: 56 hospitals and clinics in Australia, Belgium Bulgaria, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, the UK, and the USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study (GSK study number: 201677; NCT02531633) and Rapid Service Fee were funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). Conflict of interest was reported in the article |

Inclusion criteria: Patients aged C 50 years with active GCA were included. GCA was diagnosed according to the following criteria: history of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) C 50 mm/h and/or C-reactive protein (CRP) C 2.45 mg/dl; plus unequivocal cranial GCA symptoms and/or unequivocal polymyalgia rheumatica symptoms; plus features of GCA by temporal artery biopsy or imaging (e.g., ultrasound, magnetic resonance angiography, computed tomography angiography, positron emission tomographycomputed tomography).

Exclusion criteria: Patients with a major ischemic event (unrelated to GCA) within 12 weeks of screening, marked prolongation of QTc interval, or receiving certain medications were excluded.

N total at baseline: Intervention1: 42 Intervention2: 39 Intervention3: 26 Control1: 27 Control2: 27

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I1: 70.5 (7.3) I2:68.1 (6.7) I3:67.5 (9.5) C1: 71.6 (7.1) C2: 70.7 (9.0)

Sex: I1:74% female I2; 77% female 13; 73% female C1: 85% female C2: 78% female

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Intervention1: sirukumab 100 mg q2w for 12 months plus a 6-month prednisolone taper Intervention2: sirukumab 100 mg q2w for 12 months plus a 3-month prednisolone taper. Intervention3: sirukumab 50 mg q4w for 12 months plus a 6-month prednisolone taper

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Control1: placebo q2w for 12 months plus a 6-month prednisolone taper Control2: placebo q2w for 12 months plus a 12-month prednisolone taper |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention 1: N 33 (79%) Reasons (describe); study termination or early withdrawal

Intervention 2: N 34 (87%) Reasons (describe); study termination or early withdrawal

Intervention 3: N 21 (81%) Reasons (describe); study termination or early withdrawal

Control 1: N 22 (81%) Reasons (describe); study termination or early withdrawal

Control 2: N 23 (85%) Reasons (describe); study termination or early withdrawal

Incomplete outcome data: Yes, see lost to follow up; only patients with completed data in analysis.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Sustained remission, n (%): Intervention1: 3 (18%) Intervention2: 2 (15%) Intervention3: 1 (11%) Control1: 0 Control2: 0

Presence of flare from week 12 to 52, n (%); Intervention1: 1 (6%) Intervention2: 1 (8%) Intervention3: 1 (11%) Control1: 5 (56%) Control2: 2 (29%)

TEAE, n (%); Intervention1: 41 (98%) Intervention2: 36 (92%) Intervention3: 25 (96%) Control1: 26 (96%) Control2: 24 (90%)

AESI, n (%); Intervention1: 30 (71%) Intervention2: 27 (72%) Intervention3: 23 (89%) Control1: 15 (56%) Control2: 15 (56%)

Overall cumulative prednisolone dose, mean (sd) mg; Intervention1: 2.97 (2.97) Intervention2: 2.42 (2.09) Intervention3: 2.56 (1.36) Control1: 3.16 (1.99) Control2: 3.60 (1.48)

|

Limited number of patients for analyses as result of early study termination |

|

Stone, 2021 |

Type of study: open-label extension phase study of RCT

Setting and country: x

Funding and conflicts of interest: Study was sponsored by F Hoffmann-La Roche. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who completed the 52-week double-blind part of the study were eligible to enter part two, which was a 104-week, open-label, non-randomised follow-up period.

Exclusion criteria: -

N total at baseline (week 52): Intervention1: 85 Intervention2: 40 Control1: 46 Control2: 44 Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I1: 70.0 98.4) I2: 69.9 (8.4) C1: 68.8 (7.4) C2:69.7 (8.0)

Sex: I1:72 68% I2: 67, 79% C1:35, 76% C2:33, 75%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes at baseline 0; but not at baseline 52 weeks regarding disease activity. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Intervention1: tocilizumab weekly plus a 26-week prednisolone taper Intervention2: tocilizumab every other week plus a 26-week prednisolone taper*

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Control1: placebo plus a 52-week prednisolone taper plus Control2: a 26-week prednisolone taper

|

Length of follow-up: 104 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention1: N 8 (9%) Reasons (describe); AE (2x), death, patient decision (3x), physician decision.

Intervention1: N 2 (5%) Reasons (describe); AE, death.

Control1: N 4 (9%) Reasons (describe); AE, death, patient decision (2x).

Control2: N 4 (9%) Reasons (describe); lost-to-follow-up, patient decision (2x), physician decision.

Incomplete outcome data: Yes, see lost to follow up; only patients with completed data in analysis.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Remission at week 104 Intervention1: 36/40 (90%) Intervention2: 81/85 (95%) Controle1: 34/46 (74%) Controle2: 33/44 (75%)

Sustained remission at week 104: Intervention1: 13/36 (36%) Intervention2: 38/81 (47%) Controle1: 20/34 (59%) Controle2: 18/33 (55%)

Cumulative prednisolone dose, median mg (IQR) over 3 years Intervention1: 2647 mg (95% CI 1987–3507) Intervention2:3948 mg (2352–5186) Controle1: 5323 mg (3900–6951) Controle2: 5277 mg (3944–6685)

|

Open label follow-up, not all patients received initial medication. |

|

Strand, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT (post hoc analysis)

Setting and country: x

Funding and conflicts of interest:This study was funded by Roche. Funding for manuscript preparation was provided by F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd. Competing of interest are reported in the article. |

Inclusion criteria: patients ≥ 50 years of age with newly diagnosed or relapsing active GCA confirmed by temporal artery biopsy or cross-sectional imaging and a history of elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate attributable to GCA were eligible for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria: ? N total at baseline: Intervention: 100 Control:50

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 695 (8.5) C: 69.3 (8.1)

Sex: I: 78% female C: 76 female

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

tocilizumab-QW + Pred-26

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

PBO + Pred-26

|

Length of follow-up: 52 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N 15(15%) Reasons; AE (6x), chose not to participate (6x), lack of efficacy, withdrawn by physician, no adherence trial

Control: N 6 (12%) Reasons; AE (2x), lack of efficacy(2x), chose not to participate (2x).

Incomplete outcome data: Yes, see lost to follow up; only patients with completed data in analysis.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

SF-36 PCS: Intervention: 47.75 Control: 41.52

SF-36 MCS: Intervention: 51.64 Control: 49.36

SF-6D Intervention: 0.775 Control: 0.721

|

* post hoc analysis only quality of life.

SF-36; MCID ≥2.5 |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Risk of bias table

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Schmidt, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Central randomization with computer generated random numbers |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Central randomization with computer generated random numbers |

Definitely yes;

Reason: double blinded placebo controlled RCT Patients, health care providers and outcome assessors blinded (blinding of data collectors and analysts not reported) |

Probably no

Reason: loss to follow up was frequent but similar in all groups. Outcome were reported based on collected data. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely no;

Reason: due the loss of follow up no statistical analysis were performed due to the limited sample size. |

Some concerns, due to frequent loss to follow up and the limited data available. |

|

Stone, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Central randomization with computer generated random numbers (initial) |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Central randomization with computer generated random numbers (initial) |

Definitely no;

Open label follow up study. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Probably no;

Reason: not all outcomes reported regarding the initial subgroups. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns, due to open label follow up phase. |

|

Strand, 2019 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Central randomization with computer generated random numbers |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Central randomization with computer generated random numbers |

Definitely yes;

Reason: double blinded placebo controlled RCT Patients, health care providers and outcome assessors blinded (blinding of data collectors and analysts not reported) |

Probably yes;

Reason: loss to follow up was frequent but similar in all groups. Outcome were reported based on collected data. |

Probably yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported regarding quality of life in this post-hoc analysis. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns since the current publication is a post-hoc analysis. |

- Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules..

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body. Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

- Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Hellmich, 2018 |

Guideline, for considerations |

|

Monti, 2019 |

Articles in BSR-guideline |

|

Berti, 2019 |

Articles in BSR-guideline |

|

Villiger, 2016 |

In BSR-guideline |

|

Bender, 2020 |

Articles in BSR-guideline |

|

Stone, 2019 |

Post-Hoc GiACTA; only patients with flare |

|

Spiera, 2021 |

Post-Hoc GiACTA: patients with GCA+PMR, GCA+carnial symptoms |

|

Dua, 2021 |

Articles in BSR-guideline |

|

Conway, 2018 |

No comparison, only ustekinumab |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 25-09-2023

Beoordeeld op geldigheid :

Algemene gegevens

Autorisatie van deze richtlijn is afgestemd met Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap.

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met reuscelarteriitis.

Samenstelling van de werkgroep

Werkgroep

- Prof. Dr. E. Brouwer, reumatoloog, werkzaam in UMC Groningen, NVR, voorzitter van de werkgroep.

- Drs. D. Boumans, reumatoloog, werkzaam in Ziekenhuisgroep Twente (t/m december 2022), NVR.

- Prof. Dr. J. van der Laken, reumatoloog, werkzaam in Amsterdam UMC, NVR.

- Dr. A. van der Maas, reumatoloog, werkzaam in Sint Maartenskliniek, NVR.

- Dr. M. Sandovici, reumatoloog, werkzaam in UMC Groningen, NVR

- Dr. K. Visser, reumatoloog, werkzaam in Hagaziekenhuis, NVR.

- Dr. W. Eizenga, huisarts, NHG.

- Dr. A.E. Hak, internist-klinisch immunoloog, werkzaam in Amsterdam UMC, NIV/NVvAKI.

- Dr. D.J. Mulder, internist-vasculair geneeskundige werkzaam in UMC Groningen, NIV/NVIVG.

- Dr. J.W. Pott, oogarts, werkzaam in UMC Groningen, NOG.

- Mw. O. Vos, verpleegkundig specialist, werkzaam in Tergooi MC, V&VN.

- Dhr. H. Spijkerman, fysiotherapeut, KNGF.

- Mw. M. Deinema, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, vasculitis stichting.

Klankbordgroep

- Dr. D. Paap, fysiotherapeut, werkzaam in UMC Groningen, KNGF.

- Dr. R. Ruiter, internist ouderengeneeskunde, klinisch farmacoloog, werkzaam in Maasstad ziekenhuis, NIV/OGK.

- Dr. T. Balvers, neuroloog, werkzaam in LUMC, NVN.

- Prof. Dr. R.H.J.A. Slart, nucleair geneeskundige, werkzaam in UMC Groningen, NVNG.

- Drs. G. Mecozzi, chirurg, werkzaam in UMC Groningen, NVT.

- Dr. B.R. Saleem, chirurg, werkzaam in UMC Groningen, NVvH.

- Mw. M. Esseboom, oefentherapeut, VvOCM.

- Mw. J. Korlaar- Luigjes, verpleegkundige gespecialiseerd in reumatologie en vasculitis, werkzaam in Meander MC, V&VN.

- Mw. M. van Engelen, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, vasculitis stichting.

- Mw. O. van Eden, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, vasculitis stichting.

Met ondersteuning van

- Drs. I. van Dusseldorp, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- Dr. M.M.A. Verhoeven, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Prof. Dr. E. Brouwer (voorzitter) |

internist, reumatoloog |

- Vanaf 2 april 2022 Bestuurslid stichting Auto-immune Research Collaboration Hub ARCH |

|

Geen |

|

Drs. D. Boumans |

reumatoloog |

- Lid OMERACT-US Large Vessel Vasculitis - Consulterend reumatoloog Prisma Netwerk Siilo B.V. |

- |

Geen |

|

Prof. Dr. J. van der Laken |

reumatoloog |

- |

- |

Geen |

|

Dr. A. van der Maas |

reumatoloog |

Lid van de wetenschappelijke adviesraad van Medidact, werkzaamheden: meedenken over kopij/onderwerpen, soms artikelen en af en toe voorwoord/editorial schrijven |

1. In ons ziekenhuis zijn we bezig met onderzoek naar PMR. Er loopt een korte proof-of-concept studie naar rituximab bij PMR, vooralsnog ongesubsidieerd. Er zijn geen partijen betrokken met financiële belangen bij de uitkomst. 2. We zijn verder een RCT aan het opzetten naar methotrexaat bij patiënten bij wie recent de diagnose PMR is gesteld. We hebben hiervoor subsidie toegezegd gekregen van ReumaNederland. Zij hebben geen financieel belang bij de uitkomst van dit onderzoek. 3. Onze afdeling werkt mee aan een sponsor geïnitieerde studie met sarilumab bij PMR. Onze afdeling krijgt een vergoeding voor het includeren en behandelen van patiënten in het kader van dit onderzoek. Los daarvan is er geen bijkomend financieel belang. |

Geen |

|

Dr. M. Sandovici |

reumatoloog |

- |

PI ReumaNederland project: “A novel disease model for Giant Cell Arteritis: the antibody-independent role of B cells in the pathogenesis of Giant Cell Arteritis” |

Geen |

|

Dr. K. Visser |

reumatoloog |

commissie kwaliteit NVR, onbetaald; EULAR werkgroep aanbevelingen t.a.v. reumatische immuun gerelateerde bijwerkingen immunotherapie, onbetaald |

HAGA reumatologie – sarilumab studie Sanofi |

Geen |

|

Dr. W. Eizenga |

Huisarts |

|

|

Geen |

|

Dr. A.E. Hak |

Internist, Klinisch immunoloog |

|

Dr. A.E. Hak is coördinator van het door het Ministerie van VWS erkend Vasculitis Expertisecentrum AMC (actueel Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC). Binnen dit expertisecentrum zijn patiënten met GCA in zorg, dan wel wordt van elders om expertise gevraagd (naast overige vormen van vasculitis). In dit kader wordt regelmatig overleg gevoerd met de Vasculitis Stichting (Patiëntenorganisatie). |

Geen |

|

Dr. D.J. Mulder |

Internist, Vasculair geneeskundige |

- |

- |

Geen |

|

Dr. J.W. Pott |

oogarts |

Opleider Oogheelkunde UMCG, secretaris werkgroep Nederlandse Neuro-ophthalmology (NeNDS), Lid bestuur European Neuro-ophthalmology Society (EUNDS) |

|

Geen |

|

Mw. O. Vos |

verpleegkundig specialist, |

- |

- |

Geen |

|

Dhr. H. Spijkerman |

Fysiotherapeut |

Lid stuurgroep Netwerk Multipele Sclerose Groningen (onbetaald), Lid Geriatrie Netwerk Groningen (onbetaald), Student post HBO - master Geriatrie - fysiotherapie te Breda. Verwachte afstudeerdatum: juni 2020 (onbetaald) |

|

Geen |

|

Mw. M. Deinema |

patiëntvertegenwoordiger |

|

-- |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiënten perspectief door patiëntenverenigingen uit te nodigen voor de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse en een lid van de patiëntenvereniging af te vaardigen in de werkgroep. Het verslag hiervan is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntenvereniging en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module verwijzing |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module diagnostiek |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module medicamenteuze behandeling |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module niet- medicamenteuze behandeling |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module monitoring |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met de schriftelijk knelpuntenanalyse. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door VvOCM, NIV, ZN, NVZ, NVR, IGJ, KNGF, VIG, NVZA, ReumaNederland, V&VN, Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland, NHG, KNMP, NOG via de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten (Bijlage 1).

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen