Computer ondersteunend screenen (COS) en digitale cytologie met AI

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de toegevoegde diagnostische waarde van computer ondersteunde (COS) dan wel digitale screening met een artificial intelligence (AI) algoritme op standaard cervixcytologische DLC-preparaten?

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling-1

Overweeg COS in te zetten omdat het een betrouwbare methode is en kwalitatief gelijkwaardig aan manueel screenen. Dit geldt alleen voor op de Europese markt toegestane COS-methodes behorende bij de eveneens op de Europese markt toegestane DLC-methode.

Voer bij de implementatie van COS in het eigen laboratorium altijd een doeltreffende verificatie uit. En houd rekening met een leercurve per analist.

Aanbeveling-2

Overweeg COS in te zetten bij (dreigende) capaciteitstekorten aan screenende analisten.

Beperk het maximum te screenen preparaten per analist per dag, zodanig dat de kwaliteit (accuratesse) van de cervixcytologische diagnostiek aantoonbaar niet lager wordt. Ook om deze reden dient de kwaliteit van COS blijvend geëvalueerd te worden.

Aanbeveling-3

Gebruik dezelfde verificatie methodiek bij de introductie van (toekomstige) CE-gemarkeerde digitale cytologie modules met AI niet alleen voor analisten maar ook voor pathologen. Advies is om 100-200 casus als testset in te zetten.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

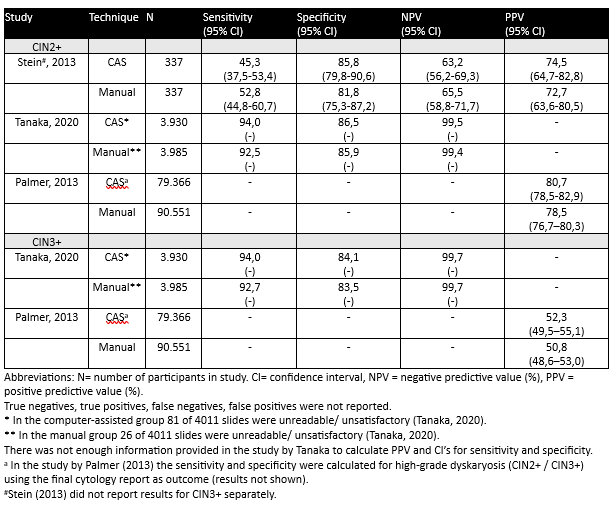

Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de diagnostische accuratesse van de Computer Ondersteunend screenen (COS) en digitale cytologie met AI voor het detecteren van CIN2+ en cervicale maligniteit, vergeleken met manuele lichtmicroscopische beoordeling met dunne laag cytologie (DLC), gebruikmakend van histologische follow-up als referentiestandaard. Zowel de gerapporteerde sensitiviteit (van 45.3% tot 94.0%) als negatief voorspellende waarde (NVW, 62.5% to 99.5%) van COS en manueel varieerden per studie, maar waren tussen beide screenmethodes vergelijkbaar. De specificiteit van COS voor CIN2+ was 85.8% - 86.5%, nagenoeg gelijk aan manuele beoordeling (81,8% - 85,9%). De gegevens voor CIN3+ komen uit twee studies (Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013). De sensitiviteit van COS voor CIN3+ was 94%, vergelijkbaar met 92.7% voor manuele beoordeling. De NWV van COS en manueel screenen was 99.7%.

De bewijskracht van de gevonden literatuur is matig vanwege beperkingen in de studieopzet, die mogelijk tot bias hebben kunnen leiden (met name door onduidelijkheden rondom het proces van patiënten selectie (Stein, 2013; Tanaka, 2020) en een beperkt inzicht in de timing van de indextest nl. de tijd tussen sampling voor cytologie en uitvoer colposcopie, die de kans op misclassificatie bias kan verhogen (Palmer, 2013; Stein, 2013)). Binnen de pathologie is dat weliswaar de standaard werkwijze in de praktijk, maar methodologisch moet dit toch beschouwd worden als een bias. De matige sensitiviteit in de studie van Stein (2013) heeft mogelijk te maken met de uitvoering van de screening in Brazilië en is niet vergelijkbaar met de kwaliteit van screenen in Nederland, maar is wel als onderbouwing te gebruiken om twee methodes met elkaar te vergelijken.

Op basis van de geïncludeerde studies (Stein, 2013; Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013) kan worden geconcludeerd dat COS screenen ten opzichte van manueel screenen tenminste gelijkwaardig is (non-inferior) aan manueel screenen en een tendens naar een hoge specificiteit en sensitiviteit en een hoge positief voorspellende waarde heeft.

De reden om COS in te zetten in de praktijk kan ook zijn om de screentijd te verkorten om capaciteitsproblemen op de werkvloer te minimaliseren. De screentijdwinst wordt in meerdere studies aangetoond variërend van 10- 90% extra gescreende preparaten per tijdseenheid (geen onderdeel van het systematisch literatuuronderzoek) (Wilbur, 2009; Palmer, 2012; Sweeney Schledermannn, 2007; Pacheco, 2007; Pacheco, 2008). Het nadeel van te hoge werkdruk is een verminderde diagnostische accuratesse. Dit effect werd aangetoond in 2 studies uit de VS met aantallen per analist per dag >100 die in Nederland niet gebruikelijk zijn (Renshaw, 2016).

In 3 studies zijn ook lagere frequenties voor COS/manueel gevonden voor afkeuren (Bethesda: unsatisfactory, KOPAC: Pap 0) van preparaten (1,8-2,0 % voor DLC versus 2,7 % (2,6-2,8) voor manueel (Palmer, 2012; Tanaka, 2020)). Er zijn meerdere aanwijzingen in de literatuur (job satisfaction) dat analisten voorkeur geven aan screenen met AI op basis van het kleinere aantal cellen dat beoordeeld moet worden per preparaat (Palmer, 2012; Thrall, 2018).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De richtlijnwerkgroep verwacht dat COS screenen kostenneutraal is. Voor de uitvoering van COS zijn per laboratorium aangepaste glaasjes, scanners en speciale microscopen nodig. De kortere screentijd en de aantallen te screenen preparaten kunnen in een business case uitwijzen of de COS-methode kosteneffectief is.

Voor de recent ontwikkelde digitale cytologie-met AI-systemen – waarvan alleen de GeniusTM Digital Diagnostic System (Hologic) CE-gemarkeerd is, (Hologic, Instructions for use, 2024) - is de verwachting dat de toepassing in de komende jaren snel zal stijgen, dat kosten mogelijk hoger zijn dan voor COS en dat ook de leercurve en expertise snel zal gaan. Wel moet rekening worden gehouden met hoge aanschafkosten. Echter mogelijkheden om via de beveiligde cloud op meerdere locaties op één systeem te werken, zullen de kosten per laboratorium kunnen drukken. Daarnaast is het mogelijk om laagdrempelig digitale consulten te vragen. Deze ontwikkeling zal ook een verdere oplossing moeten vormen voor behoud van de cervixdiagnostiek met aanvaardbare doorlooptijden bij de dreigende tekorten aan cytologisch analisten in Nederland.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

COS-toepassing in het laboratorium leidt niet tot extra handelingen of belasting voor de patiënt, omdat hetzelfde DLC glaasje gebruikt kan worden en hetzelfde sample beschikbaar is voor co-testing (hrHPV en cytologie). De snellere screentijd kan wel leiden tot een snellere uitslag bij capaciteitsproblemen in een cytologie laboratorium.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie.

De verwachting is dat COS mits goed geïmplementeerd en geverifieerd, van toegevoegde diagnostische waarde kan zijn en een oplossing is voor het dreigende tekort aan cytologisch analisten. Het gebruik van alleen één van de twee op de Europese markt toegestane COS-methodes is toegestaan behorend bij de eveneens op de Europese markt toegestane DLC- methodes. De in het eigen laboratorium uit te voeren verificatie dient aan te tonen dat de methode ten minste kwalitatief gelijkwaardig is qua sensitiviteit en specificiteit aan manueel screenen. Daarbij is het belangrijk dat alle analisten een op de dagelijkse praktijk gebaseerde leer-en test set doorlopen met vooraf gestelde minimale omvang en uitkomstcriteria voor sensitiviteit, specificiteit, NVW en PVW. Diezelfde set zou ook door ervaren analisten uit hetzelfde laboratorium als vergelijking kunnen worden beoordeeld om de criteria te laten aansluiten bij de lokale situatie. Daarbij zou een geringe “verrijking” van de samenstelling met bijzondere of zeldzame casus van toegevoegde waarde kunnen zijn.

Tevens is de verwachting dat op zeer korte termijn de COS-module met beperkte AI niet meer door leveranciers zal worden aangeboden op de markt maar dat de digitale cytologie (DC) met uitgebreidere AI daarvoor in de plaats zal komen. Hoewel er ten tijde van de systematische literatuursearch nog geen klinische studies geselecteerd konden worden, zijn er recent wel twee vergelijkende studies (Ikenberg, 2023; Cantley, 2024) gepubliceerd waarvan de resultaten hieronder kort weergegeven worden met name vanwege de verwachte toepassingsmogelijkheden, ook in Nederland. De kosten voor een digitaal systeem met AI zijn hoger, de verwachting is dat de screentijd efficiënter zal zijn en uit mondelinge communicatie en uit 2 publicaties (Ikenberg, 2023; Cantley, 2024) een prettige werkmethode zal zijn voor analisten. Een doeltreffende verificatie zowel voor analisten als pathologen, zal ook bij de introductie van digitale cervixcytologie module met AI, een voorwaarde zijn voor elk laboratorium en onderdeel van ISO15189 accreditatie.

Rationale van aanbeveling-1: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure

Beide beschreven COS-methodes die op de Europese markt zijn toegelaten kunnen veilig worden toegepast op de bijbehorende DLC-methodes, mits bij implementatie een doeltreffende verificatie in het eigen laboratorium is uitgevoerd zoals beschreven in deze richtlijn. Eén van de methodes (TISHologic) is op dit moment echter uit de handel en heeft plaatsgemaakt voor de digitale versie (GeniusHologic). Dat geeft op dit moment wellicht voor laboratoria aanleiding tot afwachten, omdat de literatuur nog onvoldoende onderbouwing geeft, maar omdat de methode wel is goedgekeurd voor de Europese markt en de voorgaande versie (TIS) wel aantoonbaar gelijkwaardig is aan manueel screenen, zou de methode na een adequate verificatie, toch ingevoerd kunnen worden. Uit de literatuur blijkt dat de accuratesse van toepassing van COS binnen de cervixcytologie diagnostiek kwalitatief tenminste gelijkwaardig aan manueel screenen. Uit de literatuur (Kitchener, 2011) blijkt dat een voldoende doeltreffende uitgevoerde leercurve-test van belang is voor de uiteindelijke gewenste accuratesse van de COS-techniek. Uit kwaliteitsoverwegingen verdient het aanbeveling om de follow-up uitkomsten van COS ten opzichte van manueel screenen periodiek maar tenminste 1x per jaar uit te voeren.

Rationale van aanbeveling-2: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure

Uit de literatuur blijkt dat de efficiëntie van het screenen (kortere screentijd) sterk varieert van 10% tot 90% korter dan bij manueel screenen en dat dit effect ook toeneemt met de tijd afhankelijk van de expertise met de COS-methode (Palmer, 2020; Stein, 2013; Pacheco 2008, Schledermann, 2007; Biscotti, 2005). De meeste winst in tijd is te behalen bij uitstrijken zonder afwijkingen (Pap1) omdat daarbij slechts een beperkt aantal velden hoeft te worden gescreend. De efficiëntie overall hangt dus ook sterk af van de prevalentie van cytologische afwijkingen.

Vanuit kwaliteitsoverwegingen en risicomanagement (ISO15189 versie 2022) dient ieder laboratorium aantoonbaar te blijven monitoren dat ook bij hogere productie per tijdseenheid door COS vergeleken met manueel screenen, de kwaliteit van de cervixcytologische diagnostiek geborgd blijft.

Rationale van aanbeveling-3: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure.

Recent zijn (na de afsluiting van het systematische literatuuronderzoek) twee publicaties verschenen waarin de digitale cytologie (DC) met AI-methode en COS op klinische uitkomsten op basis van histologie zijn vergeleken (Ikenberg, 2023; Cantley, 2024). Kort samengevat; in Ikenberg’s artikel is sprake van 2051 consecutieve TIS glaasjes uit 2020 waarvan 1994 glaasjes (=95,2%) gedigitaliseerd konden worden. Er werden in totaal 555 aselecte casus met afwijkingen retrospectief geanalyseerd, waarvan Pap1 (NILM) glaasjes deel uitmaakten d.m.v. systematische selectie (iedere 40e casus) om tot een van tevoren vastgesteld aantal casus te komen voor voldoende statistische power. Er was een complete concordantie tussen beide methodes van 97,3%, met in 0,64% een grote discrepantie. Met DC werden significant meer hooggradige laesies gevonden (hogere sensitiviteit voor HSIL+/ASC-H en CIN2+ en CIN3+ en hogere specificiteit voor LSIl en HSIL en ook hogere NVW. De screentijd voor DC was significant korter dan voor COS; 44,8 seconden versus 89,9 seconden per glaasje (p< 0,0001). Het werkplezier van analisten werd getest aan begin, halverwege en einde van de te screenen glaasjes en na een periode van adaptatie, voelde men zich zeker van de diagnose en in het algemeen was men minder vermoeid.

In de publicatie van Cantley (2024) werden 319 DLC glaasjes prospectief gediagnostiseerd door 6 analisten en 3 cytopathologen en de interobserver uitkomsten in testverband manueel en met DC werden vergeleken met de oorspronkelijke routine Pap classificatie en statistisch geanalyseerd op basis van 8, 4 en 3 Papklassen deels gebaseerd op klinische behandelstratificatie. De resultaten lieten een betere concordantie zien voor DC met AI vergeleken met manuele DLC-screening, een kortere screentijd en voor alle deelnemers betekende het gebruik van DC met AI als een positieve ervaring, gebruikersvriendelijk en comfortabel. De eerste resultaten van screenen op basis van DC met AI zijn veelbelovend en uitgebreidere klinische validatie onderzoek zal noodzakelijk zijn. De Digitale cytologie Task Force van de American Society of Cytopathology adviseert een testset van 100-200 casus voor een betrouwbare klinische validatie (Kim, 2024).

De werkgroep verwacht dat de DC met AI kwalitatief ten minste gelijkwaardig is aan manueel screenen met COS op grond van deze eerste twee publicaties en dat de screentijd t.o.v. COS mogelijk nog gehalveerd gaat worden. Er zijn dus op dit moment geen zwaarwegende argumenten om DC met AI niet in te voeren.

DC met AI is een veelbelovende nieuwe techniek voor de indicatieve cervixcytologische diagnostiek met mogelijk hogere sensitiviteit voor CIN2+ en hogere specificiteit voor LSIL en HSIL en kortere screentijd per preparaat in vergelijking met manueel screenen met COS.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In current practice cytology (manual screening on liquid based cytology) and hrHPV co-testing is often performed for women with a cervical smear. A shortage of cytotechnologists is expected to occur in the near future, a trend we are already seeing. To ensure continuity of cervical diagnostics, support for manual screening is desirable. With the help of additional computer assisted algorithms (artificial intelligence, AI), screening could be faster and possibly more reliable than the current manual screening. A systematic literature search was performed to look at the diagnostic value of computer-assisted screening (CAS) and digital cytology with AI compared to manual screening. In the considerations, more aspects (including the reproducibility and screening efficiency and job satisfaction) of these techniques both individually and by laboratory are addressed.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Computer-assisted screening (CAS)

Sensitivity CIN2+

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of CAS cytology likely results in little to no difference in sensitivity for CIN2+ (45.3- 94.0%), compared to manual screening of cervical LBC preparations (52.8 - 92.5%), using cervical histology as a reference.

Sources: Stein, 2013; Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013 |

Specificity CIN2+

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of CAS cytology likely results in little to no difference in specificity, for CIN2+ (85.8 - 86.5%), compared to manual screening of cervical LBC preparations (81.8 - 85.9%), using cervical histology a reference.

Sources: Stein, 2013; Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013 |

NPV CIN2+

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of CAS cytology likely results in little to no difference in negative predictive value (62.5 - 99.5%) for CIN2+, compared with manual screening of cervical LBC preparations (65.5 – 99.4%), using cervical histology as a reference.

Sources: Stein, 2013; Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013 |

PPV CIN2+

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of CAS cytology likely results in little to no difference in positive predictive value for CIN2+ (74.5 - 80.8%), compared with manual screening of cervical LBC preparations (72.7 - 78.5%), using cervical histology as a reference.

Sources: Stein, 2013; Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013 |

Sensitivity CIN3+

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of CAS cytology likely results in little to no difference in sensitivity for CIN3+ (94%), compared to manual screening of cervical LBC preparations (92.7%), using cervical histology as a reference.

Sources: Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013 |

Specificity CIN3+

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of CAS cytology likely results in little to no difference in specificity, for CIN3+ (84.1%), compared to manual screening of cervical LBC preparations (83.5%), using cervical histology a reference.

Sources: Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013 |

NPV CIN3+

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of CAS cytology likely results in little to no difference in negative predictive value (99.7%) for CIN3+, compared with manual screening of cervical LBC preparations (99.7%), using cervical histology as a reference.

Sources: Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013 |

PPV CIN3+

|

Moderate GRADE |

The use of CAS cytology likely results in little to no difference in positive predictive value for CIN3+ (52.3%), compared with manual screening of cervical LBC preparations (50.8%), using cervical histology as a reference.

Sources: Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013 |

Digital cytology with artificial intelligence (AI)

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn about the diagnostic accuracy of digital cytology with AI, compared to manual cytology, due to the absence of data.

Sources: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Stein (2013) conducted an observational study in Brasil to compare computer-assisted evaluation of liquid-based cytology (LBC) preparations (Sure-Path) with manual light macroscopy of the LBC preparations. The authors used the BD FocalPoint GS Imaging System (FGIS) (BD, Burlington, NC). The cytologic samples were collected in 2010-2011 through referrals to Barretos Cancer hospital (Brasil). First, the samples were analyzed with a light microscope under routine conditions, and a year later the same group of cytotechnologists conducted microscope-automated screening in the Guided Station of the FocalPoint system. The FocalPoint system classified cellular changes into quintiles in accordance with the probability of abnormality of each slide. There were 5 quintiles, with quintile 1 having the highest probability of abnormality and 5 having the lowest probability. Also, quintile 99 was introduced for slides that were classified into quintile 5 but had no image available for review and slides that the computer was not able to classify within parameters recorded in the system. These slides needed to be manually reviewed by a cytotechnologist. Cases with cytologic changes (ASC-US+) in the manual and automated groups were reviewed by 6 cytopathologists.

In total, 10.165 samples were available, of which 9.847 (96.9%) were revised, and 318 (3.1%) cases were not classified by Focal-Point (quintile 99). The results showed a good correlation of cytological classification and the quintiles of the FGIS for both techniques. The analysis of sensitivity and specificity of manual and computer-assisted methods was performed only in patients who underwent cervical biopsy (n=337). Diagnostic accuracy measures were calculated to detect CIN2+ (histologically confirmed by biopsy) using HSIL+ (high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion and higher) as the cytologic criterion.

Tanaka (2020) performed an observational study that compared manual screening of ThinPrep cytological preparations to screening by the ThinPrep Integrated Imager (Hologic, Inc). Samples were collected in 2011-2012 in a routine clinical setting in different hospitals in Japan and were analyzed at the Setagaya Health Center Clinical Laboratory Department (Tokyo, Japan). Samples were allocated in a way that manual and computer-assisted screening of each sample was not performed by the same cytotechnologist. The assessors were blinded to patient clinical information and results of each group. The ‘negative’ group included cases without CIN1 or higher squamous cell abnormalities or glandular abnormalities confirmed by histology, as well as cases that had not undergone biopsy and were determined as ‘negative’ by triple-check. The ‘positive group’ consisted of cases with CIN1 or more severe squamous cell abnormalities or glandular abnormalities confirmed by histology. In total, 4.011 samples were available, of which 3.911 were analyzed (3.503 in the ‘negative’ group and 408 in the ‘positive’ group).

Palmer (2013) conducted a parallel group randomized trial to investigate the impact of computer-assisted screening within the Scottish Cervical Screening Programme. The trial consisted of 169.917 samples which were LBC preparations from the screening program. Two groups of three laboratories screened 79.366 slides randomized to test arm (ThinPrep Imager; Hologic, Inc.) and 90.551 to control arm (manual ThinPrep screening). The preparations were randomly allocated in each laboratory by a strict accession number (1–50 imaged and 51–100 manually screened). Rural and urban laboratories participated in the trial. Screeners were not blinded. Data for the analysis were derived from a screening database and from recording sheets designed to capture productivity data. Sensitivity, specificity and false-negative rates were calculated using the final cytology report as the outcome for each participating laboratory with confidence intervals and mean values for the total production, and positive predictive value (PPV) for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN2+) was determined using histological biopsy as outcome.

Results

Results per outcome measure are shown in Table 1.

In the study of Palmer (2013) results are reported for the sum of all six (not individual) laboratories.

Table 1. Diagnostic accuracy of computer-assisted (CAS) cytology vs. manual screening of cervical cytological preparations (CIN2+ and CIN3+) using histology as a reference standard

1. Computer-assisted (CAS) cytology

Sensitivity

In the study by Stein (2013), the sensitivity of CAS cytology (FocalPoint) to detect CIN2+ was 45.3% (95% confidence interval (CI) 37.5 - 53.4), compared to 52.8% (95% CI 44.8 - 60.7) for the manual light microcopy of LBC preparations.

Tanaka (2020) found that the sensitivity of CAS cytology (ThinPrep Integrated Imager) to detect CIN2+ in cervical cytological preparations was 94.0%, compared to 92.5% for manual screening of ThinPrep cytological preparations. For CIN3+, the sensitivity was 94.0 % in the CAS cytology group and 92.7% in the manual cytology group.

Palmer (2013) found that the mean value of 6 laboratories for PPV for CIN2+ was 80.7 (CI 78,5 -82,9) for the imager arm and 78,5 (CI 76,7-80,3) for the manual arm. For the CIN3+ outcome the imager arm showed 52,3% (CI49,5-55,1) and for the manual arm 50,8 (CI48,6-53,0).

Specificity

In the study by Stein (2013) the specificity of CAS cytology (FocalPoint) to rule-out CIN2+ was 85.8% (95% CI 79.8 - 90.6), compared to 81.8% (95% CI 75.3 - 87.2) for the manual light microcopy of LBC preparations.

Tanaka (2020) found that the specificity of CAS cytology (ThinPrep Integrated Imager) to rule out CIN2+ lesions was 86.5%, compared to 85.9% for manual screening of ThinPrep cytological preparations. For CIN3+, the specificity was 84.1% in the CAS cytology group and 83.5% in the manual cytology group.

Positive predictive value (PPV)

The positive predictive value of CAS cytology (FocalPoint) for CIN2+ was 74.5% (95% CI 64.7 - 82.8), compared to 72.7% (95% CI 63.6 - 80.5) for the manual light microcopy of LBC preparations (Stein, 2013).

Tanaka (2020) did not report the PPV of CAS cytology (ThinPrep Integrated Imager) for CIN2+/ CIN3+.

Palmer (2013) calculated PPV as the percentage of cases referred for high-grade cytological abnormalities (moderate dyskaryosis or worse) that are found on biopsy to have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN2+). The PPV of CAS cytology was 80.7% (95% CI 78.5–82.9), compared to 78.5% (95% CI 76.7–80.3) for manual screening.

For CIN3+, the PPV was 52.3% (95%CI: 49.5–55.1) using CAS cytology and 50.8% (95%CI: 48.6–53.0) using manual screening.

Negative predictive value (NPV)

The NPV of CAS cytology (FocalPoint) for CIN2+ was 63.2% (95% CI 56.2-69.3), compared to 65.5% (95% CI 58.8 - 71.7) for the manual light microcopy of LBC preparations (Stein, 2013).

In the study of Tanaka (2020), the NPV for CAS cytology (ThinPrep Integrated Imager) for CIN2+ was 99.5%, compared to 99.4% in the manual screening group. For CIN3+, the NPV was equal in both study groups, 99.7% (in the CAS cytology group and in the manual cytology group).

Palmer (2013) did not report on NPV of CAS cytology vs. manual screening.

2. Digital cytology with artificial intelligence (AI)

There were no studies found at the time of the systematic literature search that reported on digital cytology with AI that fulfilled the PICROT criteria.

Level of evidence of the literature

Computer-assisted screening (CAS)

The evidence was derived from 2 observational studies and 1 parallel group randomized trial (Stein, 2013; Tanaka, 2020; Palmer, 2013). The level of evidence for all reported outcome measures started at ‘high quality’.

Sensitivity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘sensitivity’ was downgraded by 1 level to ‘moderate’, because of study limitations related to patient selection and the flow and timing (unclarity about the time between index test and reference standard (-1 risk of bias).

Specificity

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘specificity’ was downgraded by 1 level to ‘moderate’, because of study limitations related to patient selection and the unclarity about the time between index test and reference standard (-1 risk of bias).

PPV

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘PPV’ was downgraded by 1 level to ‘moderate’, because of study limitations and unclarity about flow and timing (-1 risk of bias).

NPV

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘NPV’ was downgraded by 1 level to ‘moderate’, because of study limitations and concerns about flow and timing (-1 risk of bias).

Digital cytology with artificial intelligence (AI)

The level of evidence could not be assessed due to the absence of studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the diagnostic accuracy of computer-assisted screening (CAS) or digital cytology with artificial intelligence (AI) compared to manual screening on light microscopic Thin-layer slides in women with cervical smears, using histological outcome as a reference standard?

| P (Patients): |

Women with cervical smears |

| I (Index test): |

Computer-assisted cytology or digital cytology with AI |

| C (Comparator test): |

Manual light microscopy of liquid-based cytology (LBC) |

| R (Reference standard): | Detection of high grade CIN2+ lesions and malignancy (this includes CIN3+, AISs and adenocarcinomas) by histologic examination of cervical biopsy specimens |

| O (Outcome measure): |

Sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), positive predictive value (PPV) |

| Timing and setting: | Additional techniques with digital cytology as a replacement for fully manual light microscopic techniques for assessment of cervical smears |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV as critical outcome measures for the comparison of the abovementioned techniques.

At the moment of preparing this revision, the guideline working group restricted to liquid bases cytology techniques approved for the European market (for CAS: Becton and Dickinson Focal point Surepath and Hologic ThinPrep Imaging system (TIS) and for the digital method with AI only the (GeniusHologic) is recently admitted.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a between-test difference of maximum 5% in sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) for CAS at least equal to manual screening.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms for studies about diagnostic accuracy of computer-assisted cervical cytology (with or without AI) vs. manual liquid-based cytology from 01-01-2005 until 19-09-2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 408 hits.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, detailed search strategy with search date, in- and exclusion criteria, exclusion table, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), RCTs or observational studies;

- full-text English language publication; and

- studies according to the PICROTS criteria.

22 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 19 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 3 studies were included. After closing of the systematic Medline Database search, two studies were recently published on digital cytology with AI. These are commented on in the considerations and recommendations by working group members.

Results

Two observational studies (Stein, 2013; Tanaka, 2020) and 1 parallel group randomized trial (Palmer, 2013) were included in the analysis of the literature.

Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- 1 - Biscotti CV, Dawson AE, Dziura B, Galup L, Darragh T, Rahemtulla A, Wills-Frank L. Assisted primary screening using the automated ThinPrep Imaging System. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005 Feb;123(2):281-7. PMID: 15842055.

- 2 - Cantley RL, Jing X, Smola B, Hao W, Harrington S, Pantanowitz L. Validation of AI-assisted ThinPrep® Pap test screening using the GeniusTM Digital Diagnostics System. J Pathol Inform. 2024 Jul 2;15:100391. doi: 10.1016/j.jpi.2024.100391. PMID: 39114431; PMCID: PMC11304920.

- 3 - Hologic, GeniusTM Digital Diagnostic System Instructions for Use , 2001.

- 4 - Ikenberg H, Lieder S, Ahr A, Wilhelm M, Schön C, Xhaja A. Comparison of the Hologic Genius Digital Diagnostics System with the ThinPrep Imaging System-A retrospective assessment. Cancer Cytopathol. 2023 Jul;131(7):424-432. doi: 10.1002/cncy.22695. Epub 2023 Apr 17. PMID: 37068094.

- 5 - Kim D, Thrall MJ, Michelow P, Schmitt FC, Vielh PR, Siddiqui MT, Sundling KE, Virk R, Alperstein S, Bui MM, Chen-Yost H, Donnelly AD, Lin O, Liu X, Madrigal E, Zakowski MF, Parwani AV, Jenkins E, Pantanowitz L, Li Z. The current state of digital cytology and artificial intelligence (AI): global survey results from the American Society of Cytopathology Digital Cytology Task Force. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2024 Sep-Oct;13(5):319-328. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2024.04.003. Epub 2024 Apr 16. PMID: 38744615.

- 6 - Kitchener HC, Blanks R, Dunn G, Gunn L, Desai M, Albrow R, Mather J, Rana DN, Cubie H, Moore C, Legood R, Gray A, Moss S. Automation-assisted versus manual reading of cervical cytology (MAVARIC): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Jan;12(1):56-64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70264-3. Epub 2010 Dec 9. PMID: 21146458.

- 7 - Pacheco MC, Conley RC, Pennington DW, Bishop JW. Concordance between original screening and final diagnosis using imager vs. manual screen of cervical liquid-based cytology slides. Acta Cytol. 2008 Sep-Oct;52(5):575-8. doi: 10.1159/000325600. PMID: 18833820.

- 8 - Palmer TJ, Nicoll SM, McKean ME, Park AJ, Bishop D, Baker L, Imrie JE. Prospective parallel randomized trial of the MultiCyte™ ThinPrep(®) imaging system: the Scottish experience. Cytopathology. 2013 Aug;24(4):235-45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2012.00982.x. Epub 2012 May 22. PMID: 22616770.

- 9 - Schledermann D, Hyldebrandt T, Ejersbo D, Hoelund B. Automated screening versus manual screening: a comparison of the ThinPrep imaging system and manual screening in a time study. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007 Jun;35(6):348-52. doi: 10.1002/dc.20640. PMID: 17497655.

- 10 - Stein MD, Fregnani JH, Scapulatempo C, Mafra A, Campacci N, Longatto-Filho A; RODEO Study Team From Barretos Cancer Hospital. Performance and reproducibility of gynecologic cytology interpretation using the FocalPoint system: results of the RODEO Study Team. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013 Oct;140(4):567-71. doi: 10.1309/AJCPWL36JXMRESFH. PMID: 24045555.

- 11 - Tanaka K, Aoki D, Tozawa-Ono A, Suzuki N, Takamatsu K, Nakamura M, Tsunoda H, Seino S, Kobayashi N, Shirayama T, Takahashi F. Comparison of ThinPrep Integrated Imager-Assisted Screening versus Manual Screening of ThinPrep Liquid-Based Cytology Specimens. Acta Cytol. 2020;64(5):486-491.

- 12 - Wilbur DC, Black-Schaffer WS, Luff RD, Abraham KP, Kemper C, Molina JT, Tench WD. The Becton Dickinson FocalPoint GS Imaging System: clinical trials demonstrate significantly improved sensitivity for the detection of important cervical lesions. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009 Nov;132(5):767-75. doi: 10.1309/AJCP8VE7AWBZCVQT. PMID: 19846820.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

Research question: What is the diagnostic value of new digital techniques (with or without an artificial intelligence algorithm) for cervical cytological preparations?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Stein, 2013 |

Type of study[1]: cohort diagnostic accuracy study

Setting and country: Barretos Cancer Hospital, Brasil

Funding and conflicts of interest: BD Brazil (São Paulo) supported part of the study with the SurePath collection kits and equipment.

|

Inclusion criteria: cervix cytologic slides of women who had a previous suspicious examination elsewhere, women examined in mobile units of the Preventing Cancer Hospital of Barretos, women who had gynecologic consultations in the municipalities that send their tests to the sector of pathology at Barretos Cancer Hospital

Exclusion criteria: not reported

N= 10,165 slides n=337* slides *used for analysis of diagnostic accuracy

Prevalence: n.a. Mean age (± SD): 45 (13.9)

Other important characteristics: n.a. |

Describe index test: microscope-automated screening in the Guided Station of the FocalPoint system

Cut-off point(s): n.a

Comparator test[2]: slides were prepared in the liquid-based Sure-Path method and evaluated with a light microscope under routine conditions.

Cut-off point(s): n.a

Cases with cytologic changes (ASC-US+) in the manual and automated arms were reviewed by 6 cytopathologists. |

Describe reference test[3]: cervix biopsy with histology

Cut-off point(s): n.a.

|

Time between the index test en reference test: n.a.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) n.a.

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? n.a. |

Outcome measures and effect size (95%CI)4:

MANUAL SCREENING Without cytopathologist review (n=337) Sensitivity 52.8 (44.8-60.7) Specificity 81.8 (75.3-87.2) Positive predictive value 72.7 (63.6-80.5) Negative predictive value 65.5 (58.8-71.7)

With cytopathologist review (N=337) Sensitivity 59.6 (51.6-67.3) Specificity 83.0 (76.6-88.2) Positive predictive value 76.2 (67.8-83.3) Negative predictive value 69.2 (62.5-75.4)

COMPUTER-ASSISTED SCREENING Without cytopathologist review (n=337) Sensitivity 45.3 (37.5-53.4) Specificity 85.8 (79.8-90.6) Positive predictive value 74.5 (64.7-82.8) Negative predictive value 63.2 (56.2-69.3)

With cytopathologist review (N=334) Sensitivity 60.4 (52.3-68.0) Specificity 76.0 (69.0-82.1) Positive predictive value 69.6 (61.2-77.1) Negative predictive value 67.9 (60.8-74.3) |

Diagnostic accuracy parameters were calculated to predict CIN2+ (Biopsy) Using HSIL+ as the cytologic criterion.

|

|

Tanaka, 2020 |

Type of study: case-control diagnostic accuracy study

Setting and country: Keio University Hospital, St. Marianna University Hospital, Tokyo Dental College Ichikawa General Hospital, and NTT Medical Center Tokyo; Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study was supported by Hologic Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) according to the multicentre collaborative research agreement.

|

Inclusion criteria: women who had a ThinPrep Pap test

Exclusion criteria: unsatisfactory results/ slides could not be interpreted.

N=4,011

Prevalence: n.a.

Mean age (± SD): n.a.

Other important characteristics: n.a.

|

Describe index test: screening of slides with ThinPrep Integrated Imager

Cut-off point(s): Bethesda classes, ASC-US

Comparator test: manual screening of ThinPrep slides

Cut-off point(s): n.a. |

Describe reference test: cervix biopsy with histology

Cut-off point(s): CIN 1,2 en 3

|

Time between the index test en reference test: n.a.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) = 100 (2.5%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Yes |

Outcome measures and effect size:

MANUAL SCREENING CIN2+ Sensitivity 92.5 % Specificity 85.9 % Negative predictive value 99.4 % Positive predictive value – n.a.

CIN3+ Sensitivity 92.7 % Specificity 83.5 % Negative predictive value 99.7 % Positive predictive value – n.a.

SCREENING USING THINPREP IMAGER CIN2+ Sensitivity 94.0 % Specificity 86.5 % Negative predictive value 99.5 % Positive predictive value – n.a.

CIN3+ Sensitivity 94.0 % Specificity 84.1 % Negative predictive value 99.7 % Positive predictive value – n.a.

Difference in sensitivity and specificity for the negative (n=3,503 cases) and positive group (n=408) Negative group Specificity manual 88.9 (95% CI 87.8- 89.9)% Specificity Imager 89.6 (95%CI 88.6-90.5) % Difference 0.7 (95% CI -0.13 – 1.5) % (p=0.1)

Positive group Sensitivity manual 91.7 (95%CI 88.4-94.1) % Sensitivity Imager 92.4 (95% CI 89.3-94.7) % Difference 0.74 (95% CI -3.14 – 4.61) % (p=0.8) |

Definition of the study groups

cases with no CIN1 or higher squamous cell abnormalities or glandular abnormalities confirmed by histology AND cases that had not undergone biopsy and were determined as negative by triple-check.

Positive group: cases with CIN1 or more severe squamous cell abnormalities or glandular abnormalities confirmed by histology.

|

|

Palmer, 2013

|

Type of study: parallel group randomized trial

Setting and country: rural and urban laboratories participating in Scottish Cervical Screening Programme, Scotland

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding- not reported; conflict of interest: T.J.P., S.M.N., M.E.M., D.B. and A.J.P. have all received travel and accommodation expenses to attend the Hologic Annual Medical Education meetings. J.E.A.I. and L.B. report no conflicts of interest. S.M.N. is a member of the Hologic Northern European Advisory Board. |

Inclusion criteria: all samples were screening programme LBC preparations (from Scottish Cervical Screening Programme). Heavily bloodstained samples were included in both study arms and glacial acetic acid (GAA) washes were performed according to laboratory protocols.

Exclusion criteria: none

N= 169.917 samples (number of patients not mentioned)

Prevalence: n.a.

Mean age ± SD: n.a.

Other important characteristics: n.a.

|

Describe index test: manual screening of cervical slides

Cut-off point(s): n.a.

Comparator test: image-guided (Dual Review) screening of cervical slides

Cut-off point(s): n.a. |

Describe reference test: - cervical biopsy with histology (only for PPV) - final cytology report

Cut-off point(s): n.a.

|

Time between the index test en reference test: Unclear

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) n.a.

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? n.a. |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Histology as reference standard

MANUAL SCREENING CIN2+ Sensitivity not reported Specificity not reported Negative predictive value not reported Positive predictive value 78.5 (95%CI: 76.7–80.3)

CIN3+ Sensitivity not reported Specificity not reported Negative predictive value not reported Positive predictive value 50.8 (95%CI: 48.6–53.0)

IMAGE-GUIDED SCREENING (Dual Review) CIN2+ Sensitivity not reported Specificity not reported Negative predictive value not reported Positive predictive value 80.7 (95%CI: 78.5–82.9)

CIN3+ Sensitivity not reported Specificity not reported Negative predictive value not reported Positive predictive value 52.3 (95%CI: 49.5–55.1) |

|

[1] In geval van een case-control design moeten de patiëntkarakteristieken per groep (cases en controls) worden uitgewerkt. NB; case control studies zullen de accuratesse overschatten (Lijmer et al., 1999)

[2] Comparator test is vergelijkbaar met de C uit de PICO van een interventievraag. Er kunnen ook meerdere tests worden vergeleken. Voeg die toe als comparator test 2 etc. Let op: de comparator test kan nooit de referentiestandaard zijn.

[3] De referentiestandaard is de test waarmee definitief wordt aangetoond of iemand al dan niet ziek is. Idealiter is de referentiestandaard de Gouden standaard (100% sensitief en 100% specifiek). Let op! dit is niet de “comparison test/index 2”.

[4] Beschrijf de statistische parameters voor de vergelijking van de indextest(en) met de referentietest, en voor de vergelijking tussen de indextesten onderling (als er twee of meer indextesten worden vergeleken).

Risk of bias assessment diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS II, 2011)

Research question: What is the diagnostic value of new digital techniques (with or without an artificial intelligence algorithm) for cervical cytological preparations?

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Stein, 2013 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Unclear

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? No

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear, not reported. Niet relevant? follow-up langer?

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Unclear

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Unclear |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

The study does not provide enough information about patient numbers, their characteristics and enrolment process.

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

It is unclear whether the assessors of cytological slides were blinded to the comparator test results at the time of the index test.

RISK: UNCLEAR

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

Only patients who had cervix biopsy were included in the analysis of sensitivity and specificity.

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

It is unclear how many patients of the total study population received the reference standard.

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

|

Tanaka, 2020 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear

‘Cases were selected from the routine clinical volume at the participants’ hospitals’.

Was a case-control design avoided? No

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? No

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear, not reported

Did all patients receive a reference standard? No

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

Medical information was hidden from the assessors. ‘The manual arm and imager arm for 1 specimen were sorted out so that they would not be performed by the same cytotechnologist.’

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

It is not stated whether assessors knew of the biopsy results.

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

Some cases were determined as negative by triple-check and no biopsy was performed (double reference standard).

RISK: HIGH

|

|

|

Palmer, 2013

|

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear, not reported

Likely consecutive. Samples were all screening programme LBC preparations.

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

Screeners were not blinded (not mentioned to what).

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? No

No threshold was used.

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Two reference standards were used: - biopsy with histology (used only for positive predictive value) - final cytology report (used for sensitivity and specificity)

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes Patients received one of the 2 reference standards.

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

No demographic characteristics of the patients reported.

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No |

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Bao, H., Bi, H., Zhang, X., Zhao, Y., Dong, Y., Luo, X., Zhou, D., You, Z., Wu, Y., Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Fang, L., & Wang, L. (2020). Artificial intelligence-assisted cytology for detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or invasive cancer: A multicenter, clinical-based, observational study. Gynecologic oncology, 159(1), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.07.099 |

AI not by Genius digital Diagnostic System/ experimental AI algorithm |

|

Bao, H., Sun, X., Zhang, Y., Pang, B., Li, H., Zhou, L., Wu, F., Cao, D., Wang, J., Turic, B., & Wang, L. (2020). The artificial intelligence-assisted cytology diagnostic system in large-scale cervical cancer screening: A population-based cohort study of 0.7 million women. Cancer medicine, 9(18), 6896–6906. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3296 |

AI not by Genius digital Diagnostic System/ experimental AI algorithm |

|

Bolger, N., Heffron, C., Regan, I., Sweeney, M., Kinsella, S., McKeown, M., Creighton, G., Russell, J., & O'Leary, J. (2006). Implementation and evaluation of a new automated interactive image analysis system. Acta cytologica, 50(5), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1159/000326001 |

wrong reference standard (no histology); does not report PPV and NPV |

|

Klug, S. J., Neis, K. J., Harlfinger, W., Malter, A., König, J., Spieth, S., Brinkmann-Smetanay, F., Kommoss, F., Weyer, V., & Ikenberg, H. (2013). A randomized trial comparing conventional cytology to liquid-based cytology and computer assistance. International journal of cancer, 132(12), 2849–2857. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.27955 |

wrong comparison (LBC manual versus CC, LBC CAS versus CC); missing biopsy results for some preparations; does not report sensitivity and specificity for each method |

|

Vassilakos, P., Clarke, H., Murtas, M., Stegmüller, T., Wisniak, A., Akhoundova, F., Sando, Z., Orock, G. E., Sormani, J., Thiran, J. P., & Petignat, P. (2023). Telecytologic diagnosis of cervical smears for triage of self-sampled human papillomavirus-positive women in a resource-limited setting: concept development before implementation. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology, 12(3), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasc.2023.02.001 |

selected population (only self-sampled human |

|

Xue, P., Xu, H. M., Tang, H. P., Wu, W. Q., Seery, S., Han, X., Ye, H., Jiang, Y., & Qiao, Y. L. (2023). Assessing artificial intelligence enabled liquid-based cytology for triaging HPV-positive women: a population-based cross-sectional study. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 102(8), 1026–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14611 |

selected population (only HPV+ women), |

|

Boon, M. E. and Ouwerkerk-Noordam, E. and Meijer-Marres, E. M. and Bontekoe, T. R. Switching from neural networks (PAPNET) to the imager (Hologic) for computer-assisted screening. Acta Cytologica. 2011; 55 (2) :163-166 |

CAS with Imager vs CAS with PAPNET |

|

Caputo A, Macrì L, Gibilisco F, Vatrano S, Taranto C, Occhipinti E, Santamaria F, Arcoria A, Scillieri R, Fraggetta F. Validation of full-remote reporting for cervicovaginal cytology: the Caltagirone-Acireale distributed lab. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2023 Sep-Oct;12(5):378-385. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2023.06.001. Epub 2023 Jun 7. PMID: 37482510. |

does not fit picrot |

|

Crowell, Elizabeth F. and Bazin, Cyril and Thurotte, Vianney and Elie, Hubert and Jitaru, Laurette and Olivier, Gregoire and Caillot, Yann and Brixtel, Romain and Lesner, Boris and Toutain, Matthieu and Renouf, Arnaud Adaptation of CytoProcessor for cervical cancer screening of challenging slides. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2019; 47 (9) :890-897 |

wrong ref standard |

|

Eichhorn, J. H. and Brauns, T. A. and Gelfand, J. A. and Crothers, B. A. and Wilbur, D. C. A novel automated screening and interpretation process for cervical cytology using the Internet transmission of low-resolution images: A feasibility study. Cancer. 2005; 105 (4) :199-206 |

does not fit picrot |

|

Eichhorn, J. H. and Buckner, L. and Buckner, S. B. and Beech, D. P. and Harris, K. A. and McClure, D. J. and Crothers, B. A. and Wilbur, D. C. Internet-based gynecologic telecytology with remote automated image selection: Results of a first-phase developmental trial. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2008; 129 (5) :686-696 |

does not fit picrot |

|

Erbarut Seven, I. and Mollamemisoglu, H. and Eren, F. Reliability of reporting the presence of transformation zone material in Papanicolaou smears using an automated screening system. Cytopathology. 2017; 28 (4) :280-283 |

does not fit picrot |

|

Halford, J. A. and Batty, T. and Boost, T. and Duhig, J. and Hall, J. and Lee, C. and Walker, K. Comparison of the sensitivity of conventional cytology and the ThinPrep Imaging System for 1,083 biopsy confirmed high-grade squamous lesions. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2010; 38 (5) :318-26 |

conventional cytology vs thinprep; wrong comparison |

|

Levi, Angelique W. and Chhieng, David C. and Schofield, Kevin and Kowalski, Diane and Harigopal, Malini Implementation of FocalPoint GS location-guided imaging system: experience in a clinical setting. Cancer cytopathology. 2012; 120 (2) :126-33 |

does not fit picrot |

|

Passamonti, B. and Bulletti, S. and Camilli, M. and D'Amico, M. R. and Di Dato, E. and Gustinucci, D. and Martinelli, N. and Malaspina, M. and Spita, N. Evaluation of the FocalPoint GS system performance in an Italian population-based screening of cervical abnormalities. Acta Cytologica. 2007; 51 (6) :865-871 |

does not fit picrot, C=conventional pap smeer |

|

Rebolj, M. and Rask, J. and Van Ballegooijen, M. and Kirschner, B. and Rozemeijer, K. and Bonde, J. and Rygaard, C. and Lynge, E. Cervical histology after routine ThinPrep or SurePath liquid-based cytology and computer-assisted reading in Denmark. British Journal of Cancer. 2015; 113 (9) :1259-1274 |

wrong study design,does not fit picrot |

|

Thrall MJ, Russell DK, Bonfiglio TA, Hoda RS. Use of the ThinPrep Imaging System does not alter the frequency of interpreting Papanicolaou tests as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. Cytojournal. 2008 Apr 24;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-5-10. PMID: 18435848; PMCID: PMC2373310. |

does not report outcomes of interest; does not fit picrot |

|

Wiersma, D. and Vinke, A. and Siebers, A. G. and Melchers, W. J. G. and Bekkers, R. L. M. and Loopik, D. L. The added value of digital imaging to reflex cytology for triage of high-risk human papillomavirus positive self-sampled material in cervical cancer screening: A prospective cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2023; 130 (2) :184-191 |

wrong sample (self sample) |

|

Wilbur, D. C. and Black-Schaffer, W. S. and Luff, R. D. and Abraham, K. P. and Kemper, C. and Molina, J. T. and Tench, W. D. The Becton Dickinson focalpoint GS imaging system: Clinical trials demonstrate significantly improved sensitivity for the detection of important cervical lesions. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2009; 132 (5) :767-775 |

wrong ref standard,does not fit picrot |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 10-07-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 24-06-2025

Algemene gegevens

De voorliggende richtlijn betreft een gedeeltelijke herziening van de richtlijn Cervixcytologie uit 2016. Alle modules zijn beoordeeld op actualiteit. Vervolgens is een prioritering aangebracht welke modules een daadwerkelijke update zouden moeten krijgen. Hieronder staan de modules genoemd met de wijzigingen.

|

Onderwerpen |

Wijzigingen richtlijn 2024/2025 |

|

Module 1 Algemeen |

Vervangen door de startpagina |

|

Module 1.1 Procesbeschrijving |

Vervangen door de startpagina |

|

Module 2 Epidemiologie en pathofysiologie |

Onveranderd |

|

Module 3 Aanvraag, uitvoering en verwerking |

|

|

Module 3.1 Indicaties voor cervixcytologisch onderzoek |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 3.2 Geldigheidsduur van het BVO-advies |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 3.3 Vereiste klinische gegevens |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 3.4 Methode afname materiaal |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 3.5 Logistiek van het materiaal |

Onveranderd |

|

Module 3.6 Eerste opvang en verwerking laboratorium |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4 Diagnostiek |

|

|

Module 4.1 Keuze voor test/test traject |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.1.1 Type cytologische test |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.1.2 Nieuwe moleculaire en cytologische technieken detectie CIN2+ |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

|

Submodule 4.1.2.1 Moleculaire technieken detectie CIN2+ |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

|

Submodule 4.1.2.2 Cytologische technieken detectie CIN2+ |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

|

Module 4.1.3 Primaire beoordeling van cervixcytologie |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.1.4 Codering van de uitslag |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.1.5 Beoordeelbaarheid |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.1.6 Beoordeling bij atrofie |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.2 Multiple screen protocol |

Onveranderd |

|

Module 4.3 Computer Ondersteunend Screenen (COS) en digitale cytologie met AI |

Nieuw ontwikkeld |

|

Module 4.4 hrHPV-test |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.4.1 Type hrHPV-test/Keuze hrHPV-test |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.4.2 Beoordeling resultaat van hrHPV-test |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.4.3 Uitslag hrHPV-test en beoordeling cervixcytologie |

Komt te vervallen |

|

Module 4.5 Verslaglegging |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 4.6 Rapportage |

Onveranderd |

|

Module 4.7 Wijziging in het verslag en versiebeheer |

Onveranderd |

|

Module 5 Follow-up |

|

|

Module 5.1 Follow-up na behandeling aan de cervix |

Komt te vervallen, met een verwijzing naar de CIN, AIS en VAIN richtlijn |

|

Module 5.2 Self sampling bij follow-up van behandelde cervicale laesies |

Komt te vervallen, met een verwijzing naar de CIN, AIS en VAIN richtlijn |

|

Module 5.3 Controle van de uitvoering van het advies |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 6 Organisatie van zorg |

|

|

Module 6.1 Eisen aan de methodologie en setting |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 6.2 Volumenormen |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

Module 6.3 Indicaties voor revisie |

Onveranderd |

|

Module 6.4 Bewaarcondities |

Minimale (tekstuele) aanpassingen |

|

|

|

|

Flowcharts |

|

|

Flowchart Cytologisch onderzoek en hrHPV bij klachten |

geüpdatet |

|

Flowchart Bevolkingsonderzoek |

geüpdatet |

Belangrijkste wijzigingen ten opzichte van vorige versie

Er zijn drie nieuwe (sub)modules aan de richtlijn toegevoegd, namelijk de module “Moleculaire technieken detectie CIN2+”, de module “Cytologische technieken detectie CIN2+” en de module “Computer Ondersteunend Screenen en digitale cytologie met AI”. De overige modules zijn opnieuw beoordeeld waarbij er aanpassingen zijn gedaan ter uniformering met het bevolkingsonderzoek baarmoederhalskanker, de NVOG richtlijn CIN, AIS en VAIN (2021) en de NHG standaard Vaginaal bloedverlies (versie januari 2024).

De herziening van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule(s).

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor de herziening van de richtlijn is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor personen die cervixcytologisch onderzoek krijgen.

Werkgroep

- Mw. dr. A.M. (Anne) Uyterlinde (voorzitter), klinisch patholoog (met pensioen per 01-01-2024), Amsterdam UMC, NVVP

- Mw. drs. L.F.S. (Loes) Kooreman, patholoog, Maastricht UMC+, NVVP

- Dhr. dr. A.J.C. (Adriaan) van de Brule, klinisch moleculair bioloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, NVVP

- Mw. C.H.M. (Lianne) Marijnissen - van Gils, teamleider cytologie, Pathologie Zuid-West Nederland, NVML

- Mw. L. (Liselore) Moenis, teamleider cytologie, Symbiant, NVML

- Mw. dr. N.E. (Nienke) van Trommel, gynaecoloog-oncoloog, Antoni van Leeuwenhoekziekenhuis, NVOG

- Mw. drs. A.M.L.D. (Anne-Marie) van Haaften-de Jong, gynaecoloog, HagaZiekenhuis, NVOG

- Mw. drs. R. (Roosmarijn) Luttmer, gynaecoloog, OLVG, NVOG

- Mw. dr. W.W. (Wieke) Kremer, gynaecoloog in opleiding, Amsterdam UMC, NVOG

- Dhr. ing. P.A. (Paul) Seegers, senior adviseur protocollen, Stichting Palga

- Dhr. dr. A.G. (Bert) Siebers, adviseur gegevensaanvragen, Stichting Palga

- Mw. drs. E. (Esther) Brouwer, senior programmamedewerker bevolkingsonderzoeken naar kanker, RIVM

- Mw. J. (Joyce) Nouwens, huisarts, Huisartsenpraktijk Jongsma & Nouwens, NHG

- Mw. ir. J.G. (Josée) Diepstraten, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Stichting Olijf

Met ondersteuning van

- Mw. dr. E.V. (Ekaterina) Baranova - van Dorp, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mw. dr. L. (Lotte) Houtepen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mw. dr. N. (Nikita) van der Zwaluw, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Adriaan van de Brule |

Klinisch Moleculair Bioloog in de Pathologie (KMBP), |

Beroepenveldcie. Fontys Hogescholen (onbetaald), |

Deel van eigen HPV onderzoek vindt plaats ism bedrijven, waarbij gratis testkits ter beschikking gesteld worden. Ikv. STZ erkenning HPV expertise-centrum Jeroen Bosch ziekenhuis, Kennis tbv eigen HPV-diagnostiek binnen Jeroen Bosch ziekenhuis en P-DNA

|

Geen restrictie (onderzoek CCDiagnostics: geen projectleider; onderzoek Hologic en Roche: niet gerelateerd aan uitgangsvraag module) |

|

Anne Uyterlinde (vz.) |

Universitair medisch specialist, patholoog (O-aanstelling sinds 1-1-2024) bij Amsterdam UMC locatie VUMC (onbetaald); Landelijke Referentie Functionaris Cytologie bij BVO Nederland (16 u/week, betaald) |

* Landelijke Referentiefunctionaris Bevolkingsonderzoek Baarmoederhalskanker, gedetacheerd bij Bevolkingsonderzoek Nederland (FSB), (0,4 FTE) vanuit Amsterdam UMC. Geen persoonlijke vergoeding *Technical Assessor Pathologie Laboratoira voor ISO 15189 (2022) ad hoc bij RVA. Beeordeling van werkzaamheden tijdens een audit. (betaald) |

Geen deelname aan onderzoek met extra financiering. Wel pilotonderzoek gecoördineerd als Landelijke Referentie Functionaris naar de inzet van COS binnen het bevolkingsonderzoek in opdracht van RIVM en screeningsorganisatie. De uitkomsten zijn beoordeeld en goedgekeurd door de Gezondheidsraad (2022). |

Geen restrictie |

|

Anne-Marie van Haaften-de Jong |

Gynaecoloog Haga Ziekenhuis (betaald) |

* Werkgroep NVVP - Cervixcytologie, modulaire revisie landelijke richtlijn, vacatiegelden |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Bert Siebers |

Adviseur gegevensaanvragen, Stichting Palga |

Geen |

"PREFER studie * ZonMW - Risk profiling in cervical cancer screening to reduce unnecessary referrals and follow-up - Geen projectleider" |

Geen restrictie |

|

Esther Brouwer |

Sr. programmamedewerker / projectleider (in dienstverband) RIVM-Centrum voor Bevolkingsonderzoek |

Niet van toepassing |

Werkzaam bij het Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM), Centrum voor Bevolkingsonderzoek (CvB). Voor de positie van het RIVM en de taakomschrijving van het CvB zie: www.rivm.nl. |

Geen restrictie |

|

Josée Diepstraten |

Lid werkgroep Kwaliteit van Zorg van Stichting Olijf (onbetaald) |

Namens Stichting Olijf tevens betrokken bij Programmacommissie Bevolkingsonderzoek baarmoederhalskanker en bij andere richtlijnrevisies (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Joyce Nouwens |

Functienaam: huisarts werkgever: NHG |

- Programma commissie baarmoederhalskanker, rol consulent vanuit NHG (vergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Lianne van Gils |

Teamleider cytologie, Pathologie Zuid-West Nederland B.V. |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Liselore Moenis |

Teamleider Cytologie, Symbiant |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Loes Kooreman |

Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum+, patholoog |

Voorzitter Nederlandse werkgroep gynaecopathologie, onbetaald. |

Roche PDL1 mamma, deelname aan onderzoek waarvoor vergoeding aan het ziekenhuis. Novartis PIK3CA mamma, deelname adviesraad eenmalig. SCEM 1x per jaar, vergoeding voor onderwijs gynaecopathologie WOG. * Roche - PDL1 interobserver studie mammacarcinoom - Geen projectleider * Novartis - Eenmalige adviesraad PIK3CA mammacarcinoom - Geen projectleider * SCEM – Onderwijs |

Geen advieswerk gedurende richtlijn traject. Extern gefinancierd onderzoek niet-gerelateerd. |

|

Nienke van Trommel |

Gynaecoloog- oncoloog |

kort project met RIVM in 2022/2023 over communicatie met 9-jarigen en hun ouders over HPV vaccinatie |

* KWF - Fertiliteit sparende behandeling cervix carcinoom - Projectleider * KWF - Kwaliteit van leven na fertiliteit sparende behandeling gynaecologische kanker - Geen projectleider * Maarten van der Weijden Stichting – vroege detectie ovariumcarcinoom |

Geen restrictie |

|

Paul Seegers |

Sr. Adviseur Landelijke Pathologie en Moleculaire protocollen |

Member of the digitalization working group of the Belgium Society of Pathology |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Roosmarijn Luttmer |

Gynaecoloog - Ziekenhuis Amstelland, Amstelveen |

Werkgroep preventie cervixcarcinoom Suriname |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Wieke Kremer |

Arts-assistent in opleiding tot gynaecoloog, Amsterdam UMC. |

2022-11 Online webinar op uitnodiging van Qiagen over gepubliceerd wetenschappelijk onderzoek over het gebruik van methyleringsmarkers (waaronder QiaSure) in behandeling van voorloperstadia van baarmoederhalskanker. Vergoeding uitbetaald aan werkgever. |

Concerve studie ZonMw - Preventing overtreatment of CIN2/3: role of methylation markers in predecting regression (CONCERVE) - Geen projectleider |

Geen presentaties/activiteiten voor commerciële partij gedurende richtlijntraject. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Stichting Olijf en Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse en afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging (Stichting Olijf) in de werkgroep. Het verslag van de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse (zie aanverwante producten) is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Stichting Olijf en de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de nieuwe richtlijnmodules is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Computer Ondersteunend Screenen (COS) en digitale cytologie met AI |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 tot 250.000 patiënten), volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet OF het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft (behalve een verificatier en bevoegdheden traject). De investering wordt gecompenseerd door effectiever productieproces en minder FTE (geen ontslagen maar natuurlijk verloop). Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 3.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die een uitstrijkje krijgen voor cervixcytologisch onderzoek. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NVVP, 2016) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door verschillende partijen via een schriftelijke uitvraag. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |