Timing bij ongeplande sectio’s

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het optimale tijdsinterval tussen de indicatie spoedkeizersnede en de geboorte van het kind?

Aanbeveling

Voer een spoed Sectio Caesarea Categorie 1 zo snel mogelijk uit. Vermeld bij het aanmelden van de ingreep de maximaal gewenste DDI (Decision-to-Delivery-Interval).

Voer een spoed Sectio Caesarea Categorie 2 indicatie binnen 75 minuten uit. Vermeld bij het aanmelden van de ingreep de maximaal gewenste DDI (Decision-to-Delivery-Interval). Een DDI > 75 minuten is niet wenselijk.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het doel van deze uitgangsvraag was om te achterhalen wat het optimale tijdsinterval tussen de indicatie spoedkeizersnede en het uitvoeren van de operatie is. Hiervoor is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de vergelijking tussen een DDI ≤30 minuten en DDI >30 minuten bij vrouwen die een spoed keizersnede ondergingen. Bij deze update zijn elf nieuwe observationele studies gevonden die voldeden aan de PICO. De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten (5-minute Apgar score <7, Asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10) was zeer laag. Ook voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten was de bewijskracht zeer laag. Dit betekent dat andere studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. De lage bewijskracht werd met name veroorzaakt door methodologische beperkingen en conflicterende resultaten van lage precisie. Dit is inherent aan het onderwerp. Gerandomiseerde trials over dit onderwerp zullen nooit uitgevoerd worden omdat dit als onethisch bestempeld zal worden. De informatie zal alleen uit observationele cohorten voortkomen die ook nog eens belemmerd zijn door verschillende vormen van bias. Dit is verre van ideaal maar het zijn wel de enige beschikbare data.

De analyse van literatuur resulteert in een opmerkelijke paradox: kinderen die het snelst geboren werden na het stellen van de spoedindicatie (<30 minuten) hadden de slechtste uitkomst (NICU opname, asfyxie). De kinderen bij wie gewacht werd (>30 minuten) lijken de uitkomsten beter. Echter, de analyse wordt gehinderd door het feit dat alle studies observationele cohorten waren. Door de studieopzet zijn indicaties niet gelijkelijk verdeeld over de behandelgroepen en is er sprake van selectie bias: zwangere vrouwen waarbij de foetale conditie het meest bedreigd was werden het eerst geopereerd. Kinderen die met de grootste spoed geboren werden hadden voorafgaand dus al een hogere kans op een slechte uitkomst. Het gevonden verschil zegt eerder iets over de indicatiestelling voor de ingreep dan over daadwerkelijke snelheid waarmee de ingreep verricht wordt. Bloom (2016) laat een opmerkelijk verschil zien in de mate van urgentie van de indicaties tussen de DDI<30 min en DDI>30 min groepen. In de DDI <30 minuten was in 9.2% sprake van een zeer acute indicatie (uitgezakte navelstreng 7.1%, abruptio 1.9%, bloedende placenta praevia 0.2%) terwijl dit in de DDI>30 minuten groep slechts in 0.3% voorkwam (uitgezakte navelstreng 0.2%, abruptio 0.1%, bloedende placenta praevia 0%). Gezien deze verdeling is het niet verbazingwekkend dat de kinderen in de DDI<30 min groep vaker een lage pH (<7.0) van de navelstrengarterie hadden (4.8 versus 1.6%) en wat vaker geïntubeerd moesten worden (3.1 versus 1.3%). Voor de overige neonatale uitkomsten werden geen statistisch significante uitkomsten gevonden.

Slechts enkele geïncludeerde studies corrigeren voor factoren die van invloed kunnen zijn op de keuze voor DDI <30 min versus DDI >30 min (bijvoorbeeld indicatie, mate van urgentie, cardiotocografie) of die van invloed kunnen zijn op de neonatale uitkomst (bijvoorbeeld prematuriteit, medicatiegebruik). Thomas (2004) corrigeert met logistische regressie voor de primaire indicatie voor de sectio, bevindingen bij cardiotocografie, mate van urgentie en type anesthesie. Er werd geen statistisch significant verschil gevonden in de adjusted odds ratio’s voor de 5 minuten Apgar-score <7 tussen kinderen die werden geboren met een DDI<15 min in vergelijking met een DDI tussen 16 en 75 minuten. Er werd wel een significant verschil gevonden voor 5 minuten Apgar-score <7 een DDI <15 in vergelijking met een DDI>75 minuten (OR 1.7, 95%CI 1.2 tot 2.4).

Grobman (2018) corrigeerde ook voor indicatie. Patiënten werden gestratificeerd voor foetale indicatie of niet vorderen van de baring. Grobman (2018) excludeerde echter de echt urgente indicaties (uitgezakte navelstreng, abruptio placentae) omdat deze situaties als dusdanig urgent moeten worden gezien dat bepalen van DDI niet relevant werd geacht (het kind moet immers zo snel mogelijk geboren worden) en het een te bepalende confounding factor zou zijn in relatie tot de neonatale uitkomst. Grobman (2018) analyseerde DDI <15 minuten versus 16-30 min en >30 minuten. Opvallend was dat in een substantieel deel de 30 minuten norm niet werd gehaald (83% in groep waar de baring niet vorderde en 41% in de foetale indicatiegroep). Gezien de eerder genoemde exclusiecriteria is dit laatste percentage verklaarbaar. Uit een andere systematische review bleek ook dat de 30 minuten tijdslimiet niet altijd gehaald werd (Tohler, 2014). Een subanalyse toonde dat studies van hoge kwaliteit in landen met een lage perinatale sterfte in 82% de 30 minuten norm wel werd behaald (zowel Categorie 1 als 2). Alleen kijkende naar de Categorie 1 sectio’s, dan werd in 95% van de gevallen deze norm wel gehaald (Tohler, 2014).

Spoedkeizersneden om levensreddend te handelen voor de baby kunnen ook een keerzijde hebben voor de moeder, resulterend in een toename van complicaties. Bij slechts vier van de geselecteerde studies werden maternale uitkomsten gerapporteerd (Grobman, 2018; Le Mitouard, 2020; Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022; Temesgen, 2020). Allen rapporteerden fluxus (>1000 cc), noodzaak bloedtransfusie, het aantal infecties en wondcomplicaties. Drie studies (Grobman, 2018; Le Mitouard, 2020; Temesgen, 2020) beschreven ook operatieve schade (blaas laesie) en twee studies (Grobman, 2018; Temesgen, 2020) rapporteerden de noodzaak tot hysterectomie. Er werd geen verschil gezien in maternale uitkomsten tussen DDI<30 min en DDI>30 min. Bij Grobman (2018) werden meer bloedtransfusies verricht naarmate de DDI korter was. Onverwacht zat dit verschil in de groep waarbij op foetale indicatie een sectio werd uitgevoerd. Een relatie tussen wachttijd en fluxus zou eerder verwacht zijn bij niet vorderende baring waarbij langer wachten tot meer transfusies zou leiden, maar dit liet deze studie niet zien (Grobman, 2018). Temesgen (2020) toonde daarentegen wel opvallend verschil in het aantal infecties (DDI<30min: 6.3% wondinfecties, DDI>30min: 1.5% wondinfecties). Hierbij dient wel vermeld dat Grobman (2018) plaatsvond in de VS en Temesgen (2020) in Ethiopië. Een eenduidige conclusies ten aanzien van maternale uitkomsten kan op basis van de huidige literatuur niet getrokken worden.

Wegens de lage bewijskracht is de werkgroep van mening dat het niet mogelijk is om de uitgangsvraag eenduidig te beantwoorden. Op basis van indirecte bewijsvoering, bestaande internationale richtlijnen, de grote impact voor patiënten, expert opinion en consensus is de werkgroep echter van mening dat indien er sprake is van een Categorie 1 spoedindicatie voor een sectio, deze ingreep zo snel mogelijk uitgevoerd dient te worden. Voor zorgevaluatie- en auditdoeleinden kan de 30 minuten grens als norm worden aangehouden. Hoewel bij de spoedindicatielijst een categorie 2 ingreep gedefinieerd is als een ingreep die binnen 8 uur moet plaatsvinden is bij een sectio met een Categorie 2 indicatie een DDI>75 minuten niet wenselijk. Omdat zowel binnen de Categorie 1 en Categorie 2 indicaties een verschil in urgentie kan bestaan, is het raadzaam om bij het aanmelden van deze spoedingrepen te vermelden binnen hoeveel minuten het kind geboren dient te worden.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Een spoedkeizersnede is een ingrijpende gebeurtenis voor ouders. Het is belangrijk om hiermee rekening te houden en aandacht te hebben voor eventuele angst en stress. Dit kan door goed te luisteren naar ouders. De bevallende vrouw en haar partner/naaste(n) moeten zo duidelijk mogelijk geïnformeerd worden over de spoedkeizersnede, het plan en de wachttijd tot de spoedkeizersnede. Informatie hoort op passend niveau en in begrijpelijke taal te worden gegeven. Probeer de bevallende vrouw en haar partner/naaste(n) waar mogelijk voortdurend op de hoogte te houden over de plannen en eventuele veranderingen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De werkgroep is niet bekend met kosten-effectiviteitsstudies op dit gebied. Echter zal deze module geen consequenties hebben voor de kosten aangezien de aanbevelingen niet veranderd zijn en dit reeds bestaand beleid is.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Deze richtlijn zal geen problemen geven ten aanzien van implementatie aangezien de aanbevelingen niet veranderd zijn en dit reeds bestaand beleid is. Het sluit aan bij de bestaande praktijk en zal binnen de NVOG breed gedragen zijn. Praktijkvariatie op dit onderwerp is zeer onwenselijk. Wat het ideale DDI is en in hoeverre Nederlandse ziekenhuizen al voldoen aan de bestaande normen is onbekend. Om uniformiteit te bevorderen en implementatie te verbeteren zou het raadzaam zijn als elektronische patiëntendossier (EPD-) systemen de DDI als parameter inbouwen zodat ziekenhuizen spiegelinformatie hebben over hun eigen handelen en dit kunnen inzetten voor verbetertrajecten. Door de EPD’s hierop aan te passen zal de administratieve last beperkt blijven. De DDI zou dan ook als kwaliteitsindicator gebruikt kunnen worden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van indirecte bewijsvoering, bestaande internationale richtlijnen, de impact voor patiënten, expert opinion en consensus is de werkgroep van mening dat indien er sprake is van een Categorie 1 spoedindicatie voor een sectio, deze ingreep zo snel mogelijk uitgevoerd dient te worden. Voor zorgevaluatie- en auditdoeleinden kan de 30 minuten grens als norm worden aangehouden. Bij een Categorie 2 indicatie is een DDI>75 minuten niet wenselijk. Omdat zowel binnen de verschillende Categorie 1 en Categorie 2 indicaties een verschil in urgentie kan bestaan is het raadzaam om bij het aanmelden van deze spoedingrepen te vermelden binnen hoeveel minuten het kind geboren dient te worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het adviesrapport ‘Een goed begin’ in december 2009 (Stuurgroep zwangerschap en geboorte, 2009) beschreef aanbevelingen om ‘het aantal maternale en perinatale sterftegevallen door sub-standaard factoren in de zorg in vijf jaar te halveren’. Eind 2010 schreef de Minister van VWS aan de Tweede Kamer dat deze aanbevelingen grotendeels werden overgenomen. De maatregelen richtten zich vooral op het verbeteren van de samenwerking, de acute verloskundige zorg en de risicoselectie. In juni 2011 moest de nieuwe Minister toegeven dat het advies over de voorgestelde 15 minutennorm (het starten van een behandeling in geval van een potentieel levensbedreigende situatie binnen 15 minuten) en de voorgestelde begeleidings- en bewakingsnormen niet haalbaar waren. Driekwart van de ziekenhuizen kon destijds niet aan de voorgestelde normen voldoen. Belangrijkste knelpunten waren de onvoldoende beschikbare professionals (gynaecologen, verpleegkundigen, OK-personeel) en het ontbreken van extra financiële investeringen in mensen en middelen. Deze situatie is momenteel niet verbeterd. Daarnaast was er op basis van literatuur geen eenduidig bewijs dat verkorting van het Decision-to-Delivery Interval ook daadwerkelijk tot verbeterde uitkomsten leidt.

De NICE-richtlijn (2021) uit het Verenigd Koninkrijk hanteert de 30 minuten norm voor spoed keizersneden die worden uitgevoerd omdat sprake is van een levensbedreigende situatie (Caesarean Section Category I). Dit komt overeen met Categorie 1: binnen 30 minuten (zie module ‘Classificatiesystemen’). Voor Categorie 2 wordt zowel in de Britse als Nederlandse richtlijn een limiet van 75 minuten aangehouden. Hoewel de normen in de NICE-richtlijn oorspronkelijk bedoeld waren als audit-instrument en niet als aanbevelingen, zijn ze in de kliniek wel als zodanig gebruikt. Inmiddels zijn er nieuwe studies over dit onderwerp gepubliceerd.

Gezien het acute karakter, de enorme impact op de kwaliteit van leven van patiënten en de organisatorische en logistieke crisis in de huidige Nederlandse gezondheidszorg (waarbij bestuurders steeds meer roepen om concentratie van zorg) is praktijkvariatie zeer onwenselijk. Een éénduidig advies over de snelheid waarmee een spoedkeizersnede moet worden uitgevoerd is daarom op zijn plaats. Deze module betreft een herziening van de originele module uit 2018.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Unexpected NICU admission (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DDI of ≤30 minutes on unexpected NICU admission when compared with DDI of >30 minutes in women who underwent emergency caesarean section.

Source: Ayele, 2021; Chauleur, 2009; Grobman, 2018; Hillemanns, 2003; Kitaw, 2021; Kolas, 2006; Mishra, 2018; Nasrallah, 2004; Roy, 2008; Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022; Tashfeen, 2017; Temesgen, 2020. |

2. Neonatal mortality (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DDI of ≤30 minutes on neonatal mortality when compared with DDI of >30 minutes in women who underwent emergency caesarean section.

Source: Ayele, 2021; Bello, 2015; Bloom, 2005; Grobman, 2018; Heller, 2017; Holcroft, 2005; Huissoud, 2010; Le Mitouard, 2020; Mishra, 2018; Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022; Temesgen, 2020. |

3. 5-minute Apgar score <7 (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DDI of ≤30 minutes on 5-minute Apgar score <7 when compared with DDI of >30 minutes in women who underwent emergency caesarean section.

Source: Ayele, 2021; Bello, 2015; Heller, 2017; Kitaw, 2021; Mishra, 2018; Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022; Tashfeen, 2017; Temesgen, 2020. |

4. Asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10 (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DDI of ≤30 minutes on asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10 when compared with DDI of >30 minutes in women who underwent emergency caesarean section.

Source: Bloom, 2006; Bousleiman, 2022; Hillemanns, 2003; Holcroft, 2005; Huissoud, 2010; Nasrallah, 2004; Pearson, 2011; Roy, 2008. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies (updated search)

Ayele (2021) performed a retrospective cross-sectional study to assess whether a DDI of ≤30 minutes achieved in daily practice in women who underwent emergency caesarean section in hospitals in Ethiopia. Pregnant mothers, assigned in the prenatal unit for obstetrical service and who subsequently underwent emergency caesarean delivery were included in this cohort study. Mothers having insufficient information on the patient charts, with hypertensive disorders, and transferred from other health care facilities for critical obstetric service were excluded.

In total, 510 patients were included in the analysis, of which 89 patients had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 421 patients had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measures: 5-minute Apgar score <7, unexpected NICU admission, and neonatal mortality.

Bello (2015) performed a prospective observational study to determine the DDI for emergency caesarean deliveries and to evaluate the effects of delays on perinatal outcomes, in women who underwent emergency caesarean sections at a tertiary centre in Nigeria. All emergency caesarean deliveries in women who signed informed consent were included in the cohort study. Diagnosis of intrauterine foetal death before the caesarean delivery were excluded.

In total, 235 patients were included in the analysis, of which 5 patients had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 230 patients had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measures: 5-minute Apgar score <7 and perinatal mortality.

Bousleiman (2022) performed a retrospective analysis of a prospective observational caesarean registry dataset to assess the risk for foetal outcomes based on decision-to-incision (DTI) time interval in women who underwent emergency caesarean delivery in a hospital in the United States of America. Women with a gestational age of at least 37 weeks at delivery, with no more than one prior caesarean section (only with prior transverse or unknown incision), who underwent emergency caesarean delivery were included in the cohort study. Women with more than one prior caesarean section, multiple gestations, and stillbirth, and pregnancies resulting in neonates with major congenital anomalies or a birthweight below 2,500 grams, and women with prior caesarean sections with vertical incisions were excluded.

In total, 4,760 patients were included in the analysis, of which 2751 patients had a DTI of ≤30 minutes and 2,009 patients had a DTI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measure: asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10.

Grobman (2018) performed a secondary analysis of an observational cohort to estimate whether the DTI time for caesarean delivery was associated with differences in neonatal outcomes in women who underwent caesarean delivery in 25 medical centres in the USA. Women who had term, singleton nonanomalous gestation in the cephalic presentation, no prior caesarean delivery, intended to labour in the current pregnancy, and subsequently underwent an intrapartum caesarean delivery were included in the cohort study. Women who presented to labour with non-reassuring foetal status, with indication for ≤because of an abruption or cord prolapse, and women for whom data for time for decision for caesarean or incision was lacking (or so long as to be unlikely) in the medical record were excluded.

In total, 3,482 patients were included in the analysis, of which 1171 had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 2311 had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following relevant outcome measures: unexpected NICU admission, neonatal mortality, and asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10.

Heller (2017) performed a secondary analysis of perinatal survey data to explore relevant data to DDI for emergency caesarean sections performed for the most common indications: suspected and documented foetal asphyxia at a Healthcare institute in Germany. Data of new-borns with gestational age of 24-45 completed weeks of gestation, and if one of the following indications for emergency section applied: abnormal cardiotocography (CTG) findings, abnormal foetal heart rate, asphyxia detected by foetal blood analysis, were included in the cohort study. Emergency caesarean section with a DDI of >3 hours, stillbirths with time of death prior to admission to hospital or prior to delivery or unknown, and new-borns with congenital malformations were excluded. In total, data of 39,291 caesarean sections were included, of which 3,9171 had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 120 had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measures: 5-minute Apgar score <7 and neonatal in-hospital mortality.

Kitaw (2021) performed a prospective cohort study to determine the average DDI and its effect on perinatal outcomes in women who underwent emergency caesarean sections at public hospitals in Ethiopia. Women who underwent emergency caesarean section during the study period were included in the cohort study. Women who underwent emergency caesarean section with a preterm foetus, uterine rupture before the decision, intra-uterine foetal death and foetuses with gross congenital anomalies were excluded. In total, 182 patients were included in the analysis, of which 26 patients had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 156 patients had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measures: 5-minute Apgar score <7 and unexpected NICU admission.

Le Mitouard (2020) performed an observational study to assess neonatal outcomes for emergency caesareans with different DDIs in women who underwent emergency caesarean sections at 26 public and private maternity units in France. Prospectively included cases of caesareans performed as code orange emergencies or code red extreme emergencies, regardless of the type of pregnancy or foetal presentation were included in the cohort study.

In total, 354 patients were included in the analysis, of which 178 patients had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 176 patients had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measure: neonatal mortality and asphyxia pH<7.10.

Mishra (2018) performed an observational study to assess the impact of DDI on obstetric outcomes in women who underwent emergency caesarean section in an obstetric unit in India. Pregnant women with single live foetus in pregnancy between 37 and 42 weeks with category I or category II indications (immediate threat to life of woman or foetus or maternal or foetal compromise) were included in the cohort study. Women with category III or IV (needing early delivery but no foetal or maternal compromise or planned or elective), with known congenital foetal anomaly and medical complications of pregnancy were excluded. In total, 480 patients were included in the analysis, of which 80 patients had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 400 patients had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measures: 5-minute Apgar score <7, unexpected NICU admission, and neonatal mortality.

Sunsaneevihayakul (2022) performed a retrospective study to assess the frequency of emergency caesarean deliveries with DDI of ≤30 minutes and to compare differences in pregnancy outcomes for deliveries completed before and after DDIs of 30 minutes in a hospital in Thailand. Pregnant women who had an emergency caesarean delivery were included in the cohort study.

In total, 254 patients were included in the analysis, of which 246 patients had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 8 patients had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measures: 5-minute Apgar score <7, unexpected NICU admission, and neonatal mortality.

Tashfeen (2017) performed a cross-sectional study to assess DDIs in emergency caesarean section cases to identify the impact of a delayed DDI on perinatal outcomes in all women who underwent caesarean sections at a hospital in Oman. All women with singleton pregnancies delivered by emergency caesarean section procedures due to fetal distress, antepartum haemorrhage or umbilical cord prolapse were included in the cohort study. Women with multiple pregnancies or pre-term deliveries were excluded.

In total, 246 patients were included in the analysis, of which 105 had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 141 patients had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measures: 5-minute Apgar score <7 and unexpected NICU admission.

Temesgen (2020) performed a prospective cohort study to evaluate the DDI and its effect on fetal-maternal outcomes in women undergoing emergency caesarean delivery in a specialized hospital in Northwest Ethiopia. All women who underwent category 1 emergency caesarean delivery under both general and regional anaesthesia were included in the cohort study. Women who underwent category 1 caesarean delivery with preterm foetus, uterine rupture before decision, refused to give consent and foetus with gross congenital anomalies were excluded.

In total, 166 patients were included in the analysis, of which 32 patients had a DDI of ≤30 minutes and 131 patients had a DDI of >30 minutes. The study reported the following outcome measures: 5-minute Apgar score <7, unexpected NICU admission, and neonatal mortality.

Results

In the following outcome measures, eleven studies (Ayele, 2021; Bello, 2015; Bousleiman, 2022; Grobman, 2018; Heller, 2017; Kitaw, 2021; Le Mitouard, 2020; Mishra, 2018; Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022; Tashfeen, 2017; Temesgen, 2020) from the updated search and ten studies (Bloom, 2006; Chauleur, 2009; Hillemanns, 2003; Holcroft, 2005; Huissoud, 2010; Kolas, 2006; Nasrallah, 2004; Pearson, 2011; Roy, 2008; Thomas, 2004) from the original search were taken into account.

1. Unexpected NICU admission (critical)

In total, twelve studies reported the outcome measure unexpected NICU admission. Seven studies were retrieved from the updated search (Ayele, 2021; Grobman, 2018; Kitaw, 2021; Mishra, 2018; Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022; Tashfeen, 2017; Temesgen, 2020) and five studies were retrieved from the original search (Chauleur, 2009; Hillemanns, 2003; Kolas, 2006; Nasrallah, 2004; Roy, 2008).

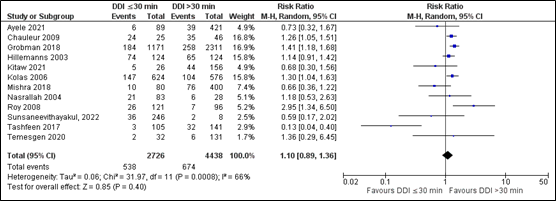

In the ≤30 minutes-group (n=2,726) and in the >30 minutes-group (n=4,438) 538 patients and 674 patients were admitted to NICU, respectively. The pooled data show a risk ratio of 1.10 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.36), favouring the >30 minutes-group (Figure 1). This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 1. NICU admission

2. Neonatal mortality (critical)

In total, eleven studies reported the outcome measures neonatal mortality. Eight studies were retrieved from the updated search (Ayele, 2021; Bello, 2015; Grobman, 2018; Heller, 2017; Le Mitouard, 2020; Mishra, 2018; Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022; Temesgen, 2020) and three studies were retrieved from the original search (Bloom, 2005; Holcroft, 2005; Huissoud, 2010).

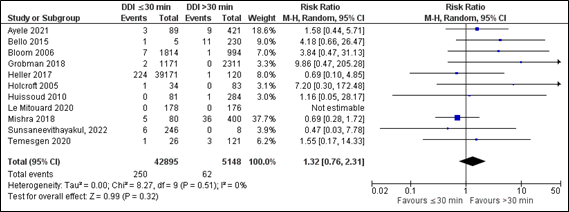

In the ≤30 minutes-group (n=42,895) and in the >30 minutes-group (n=5,148) 250 neonates and 62 neonates died, respectively. The pooled data show a risk ratio of 1.32 (95% CI 0.76 to 2.31), favouring the >30 minutes-group (Figure 2). This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Neonatal mortality

3. 5-minute Apgar score <7 (important)

In total, eight studies reported the outcome measure 5-minute Apgar score <7. All eight studies were retrieved from the updated search (Ayele, 2021; Bello, 2015; Heller, 2017; Kitaw, 2021; Mishra, 2018; Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022; Tashfeen, 2017; Temesgen, 2020).

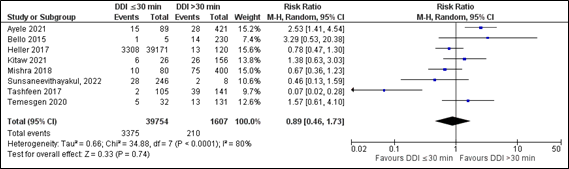

In the ≤30 minutes-group (n=39,754) and in the >30 minutes-group (n=1,607) 3,375 patients and 210 patients had a 5-minute Apgar score <7, respectively. The pooled data show a risk ratio of 0.89 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.73), favouring the ≤30 minutes-group (Figure 3). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 3. 5-minute Apgar score <7

4. Asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10 (important)

In total, ten studies reported the outcome measure asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10. Three studies were retrieved from the updated search (Bousleiman, 2022; Grobman, 2018; Le Mitouard, 2020), and seven studies were retrieved from the original search (Bloom, 2006; Hillemanns, 2003; Holcroft, 2005; Huissoud, 2010; Nasrallah, 2004; Pearson, 2011; Roy, 2008).

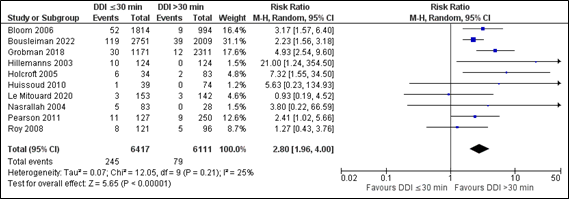

In the ≤30 minutes-group (n=6,417) and in the >30 minutes-group (n=6,111) 245 patients and 79 patients had asphyxia due to an arterial cord pH <7.10, respectively. The pooled data show a risk ratio of 2.80 (95% CI 1.96 to 4.00), favouring the >30 minutes-group (Figure 4). This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the four outcome measures was based on observational studies and therefore starts at low.

1. The level of evidence regarding unexpected NICU admission was downgraded by 4 levels to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), because the confidence interval exceeds the levels for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2), and because of conflicting results (inconsistency, -1).

2. The level of evidence regarding neonatal mortality was downgraded by 3 levels to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), the confidence interval exceeds the levels for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1), and conflicting results (inconsistency, -1).

3. The level of evidence regarding 5-minute Apgar score <7 was downgraded by 3 levels to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), the confidence interval exceeds the levels for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1), and conflicting results (inconsistency, -1).

4. The level of evidence regarding asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10 was downgraded by 1 level to very low, because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of a decision-to-delivery interval on short term (DDI ≤30 minutes) in comparison to long term (DDI >30 minutes) in women with emergency caesarean section?

P: Women undergoing an unplanned emergency caesarean section

I: DDI ≤30 min

C: DDI >30 min

O: Unexpected NICU admission, neonatal mortality, 5-minute Apgar score <7, asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered unexpected NICU admission and neonatal in-hospital mortality as critical outcome measures for decision making; and 5-minute Apgar score and asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10 as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following differences as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference (dichotomous outcomes, relative risk; yes/no):

- Unexpected NICU admission: 10% (≤0.9 or ≥1.10)

- Neonatal mortality: 5% (≤0.95 or ≥1.05)

- 5 minute Apgar score: 25% (≤0.8 or ≥1.25)

- Asphyxia arterial cord pH <7.10: 25% (≤0.8 or ≥1.25)

Search and select (Methods)

For this update, the databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) and Cochrane were searched with relevant search terms starting from 2015 until 8 November 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 807 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trials, or observational comparative studies,

- studies including ≥ 20 (ten in each study arm) patients,

- full-text English language publication, and

- studies according to the PICO.

In total, 30 studies were initially selected from the updated search, based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, nineteen studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and eleven studies were included, in addition to the ten studies which were included in the original search (see Appendix 'Evidence en Risk of Bias tabellen behorende bij de module ‘Timing van decision-to-delivery bij ongeplande sectio’s’ (Beoordeeld: 23-04-2018)').

Results

Eleven observational studies were included in the updated analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Bello FA, Tsele TA, Oluwasola TO. Decision-to-delivery intervals and perinatal outcomes following emergency caesarean delivery in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015 Sep;130(3):279-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.036. Epub 2015 May 19. PMID: 26058530.

- Bloom SL, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Gilbert S, Hauth JC, Landon MB, Varner MW, Moawad AH, Caritis SN, Harper M, Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Miodovnik M, O'sullivan MJ, Sibai BM, Langer O, Gabbe SG; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Decision-to-incision times and maternal and infant outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jul;108(1):6-11. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000224693.07785.14. PMID: 16816049.

- Bousleiman S, Rouse DJ, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Huang Y, D'Alton ME, Siddiq Z, Wright JD, Friedman AM. Decision to Incision and Risk for Fetal Acidemia, Low Apgar Scores, and Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy. Am J Perinatol. 2022 Mar;39(4):416-424. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1717068. Epub 2020 Sep 21. PMID: 32957140.

- Chauleur C, Collet F, Furtos C, Nourrissat A, Seffert P, Chauvin F. Identification of factors influencing the decision-to-delivery interval in emergency caesarean sections. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68(4):248-54. doi: 10.1159/000239783. Epub 2009 Sep 23. PMID: 19776612.

- Degu Ayele A, Getnet Kassa B, Nibret Mihretie G, Yenealem Beyene F. Decision to Delivery Interval, Fetal Outcomes and Its Factors Among Emergency Caesarean Section Deliveries at South Gondar Zone Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: Retrospective Cross- Sectional Study, 2020. Int J Womens Health. 2021 Apr 28;13:395-403. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S295348. PMID: 33953613; PMCID: PMC8089467.

- Grobman WA, Bailit J, Lai Y, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Varner MW, Thorp JM Jr, Leveno KJ, Caritis SN, Prasad M, Tita ATN, Saade G, Sorokin Y, Rouse DJ, Blackwell SC, Tolosa JE; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Defining failed induction of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218(1):122.e1-122.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.556. Epub 2017 Nov 11. PMID: 29138035; PMCID: PMC5819749.

- Heller G, Bauer E, Schill S, Thomas T, Louwen F, Wolff F, Misselwitz B, Schmidt S, Veit C. Decision-to-Delivery Time and Perinatal Complications in Emergency Caesarean Section. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017 Sep 4;114(35-36):589-596. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0589. PMID: 28927497; PMCID: PMC5615394.

- Hillemanns P, Hasbargen U, Strauss A, Schulze A, Genzel-Boroviczeny O, Hepp H. Maternal and neonatal morbidity of emergency caesarean sections with a decision-to-delivery interval under 30 minutes: evidence from 10 years. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003 Aug;268(3):136-41. doi: 10.1007/s00404-003-0527-4. Epub 2003 Jul 15. PMID: 12883825.

- Holcroft CJ, Graham EM, Aina-Mumuney A, Rai KK, Henderson JL, Penning DH. Cord gas analysis, decision-to-delivery interval, and the 30-minute rule for emergency caesareans. J Perinatol. 2005 Apr;25(4):229-35. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211245. PMID: 15616612.

- Huissoud C, Dupont C, Canoui-Poitrine F, Touzet S, Dubernard G, Rudigoz RC. Decision-to- delivery interval for emergency caesareans in the Aurore perinatal network. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010 Apr;149(2):159-64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.12.033. Epub 2010 Jan 15. PMID: 20079963.

- Kitaw TM, Tsegaw Taye B, Tadese M, Getaneh T. Effect of decision to delivery interval on perinatal outcomes during emergency caesarean deliveries in Ethiopia: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021 Nov 8;16(11):e0258742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258742. PMID: 34748563; PMCID: PMC8575252.

- Kolås T, Hofoss D, Oian P. Predictions for the decision-to-delivery interval for emergency caesarean sections in Norway. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(5):561-6. doi: 10.1080/00016340600589487. PMID: 16752234.

- Le Mitouard M, Gaucher L, Huissoud C, Gaucherand P, Rudigoz RC, Dupont C, Cortet M. Decision-delivery intervals: Impact of a colour code protocol for emergency caesareans. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020 Mar;246:29-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.12.027. Epub 2019 Dec 28. PMID: 31927407.

- Mishra N, Gupta R, Singh N. Decision Delivery Interval in Emergency and Urgent Caesarean Sections: Need to Reconsider the Recommendations? J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2018 Feb;68(1):20-26. doi: 10.1007/s13224-017-0991-6. Epub 2017 Apr 13. PMID: 29391671; PMCID: PMC5783908.

- Nasrallah FK, Harirah HM, Vadhera R, Jain V, Franklin LT, Hankins GD. The 30-minute decision-to-incision interval for emergency caesarean delivery: fact or fiction? Am J Perinatol. 2004 Feb;21(2):63-8. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-820513. PMID: 15017468.

- Pearson GA, Kelly B, Russell R, Dutton S, Kurinczuk JJ, MacKenzie IZ. Target decision to delivery intervals for emergency caesarean section based on neonatal outcomes and three year follow-up. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011 Dec;159(2):276-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.07.044. Epub 2011 Aug 11. PMID: 21839577.

- Roy KK, Baruah J, Kumar S, Deorari AK, Sharma JB, Karmakar D. Caesarean section for suspected fetal distress, continuous fetal heart monitoring and decision to delivery time. Indian J Pediatr. 2008 Dec;75(12):1249-52. doi: 10.1007/s12098-008-0245-9. Epub 2009 Feb 4. PMID: 19190880.

- Sunsaneevithayakul P, Talungchit P, Wayuphak T, Sirisomboon R, Sompagdee N. Decision-to- Delivery Interval After Implementation of a Specific Protocol for Emergency Caesarean Delivery Because of Category III Fetal Heart Rate Tracings. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2022 Nov;44(11):1153-1158. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2022.09.001. Epub 2022 Sep 10. PMID: 36096428.

- Stuurgroep zwangerschap en geboorte. Advies Stuurgroep zwangerschap en geboorte. Utrecht, december 2009. Link: https://www.nvog.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Advies-Stuurgroep-zwangerschap-en-geboorte-1.0-01-01-2009.pdf

- Tashfeen K, Patel M, Hamdi IM, Al-Busaidi IHA, Al-Yarubi MN. Decision-to-Delivery Time Intervals in Emergency Caesarean Section Cases: Repeated cross-sectional study from Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2017 Feb;17(1):e38-e42. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2016.17.01.008. Epub 2017 Mar 30. PMID: 28417027; PMCID: PMC5380420.

- Temesgen MM, Gebregzi AH, Kasahun HG, Ahmed SA, Woldegerima YB. Evaluation of decision to delivery time interval and its effect on feto-maternal outcomes and associated factors in category-1 emergency caesarean section deliveries: prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Mar 17;20(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-2828-z. PMID: 32183720; PMCID: PMC7077147.

- Tolcher MC, Johnson RL, El-Nashar SA, West CP. Decision-to-incision time and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;123(3):536-548. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000132. PMID: 24499762.

- Thomas J, Paranjothy S, James D. National cross sectional survey to determine whether the decision to delivery interval is critical in emergency caesarean section. BMJ. 2004 Mar 20;328(7441):665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38031.775845.7C. Epub 2004 Mar 15. PMID: 15023829; PMCID: PMC381217.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table: update 2023 (n=11)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Ayele, 2021 |

Quantitative retrospective cross-sectional study

Setting and country: Hospitals of South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia

Source of funding: No specific grant form any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant mothers, assigned in the prenatal unit for obstetrical service and subsequently undergone emergency caesarean delivery.

Exclusion criteria: Mothers having insufficient/incomplete information on the patient charts, with hypertensive disorders, and transferred from other health care facilities for critical obstetric service.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 89 Control: 421 Total: 510

Important prognostic factors: Time of decision (day): Intervention: 7 Control: 245

Previous CS (no/one/≥two): Intervention: 52/68/15 Control: 261/94/20

Type of anesthesia (general/regional): Intervention: 48/41 Control: 92/329

Experience of surgeons (obstetricians/emergency surgeons): Intervention: 73/16 Control: 178/243

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported. |

APGAR score at 5th minute: - <7 Intervention: 15 (16.9%) Control: 28 (6.7%) - ≥7 Intervention: 74 (83.1%) Control: 393 (93.3%) OR 2.84 (95%CI 0.44 to 5.58), in favour of DDI >30 minutes

NICU admission: Intervention: 6 (6.7%) Control: 39 (9.3%) OR: 0.70 (95%CI 0.29 to 1.72), in favour of DDI ≤30 minutes.

Neonatal death: Intervention: 3 (3.4%) Control: 9 (2.1%) OR 1.59 (95%CI 0.42 to 6.02), in favour of DDI >30 minutes.

|

|

|

Bello, 2015 |

Prospective, observational study.

Setting and country: University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Source of funding: Not reported.

Conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: All emergency caesarean deliveries, signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: Diagnosis of intrauterine fetal death before the decision for caesarean delivery (CD).

N total at baseline: Intervention: 5 Control: 230 Total: 235

Important prognostic factors: Not reported for DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes. Only reported for DDI <75 vs DDI ≥75.

Groups divided by DDI <75 vs DDI ≥75 were comparable. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported. |

5-min Apgar score: - 0-3: Intervention: 1 Control: 6 - 4-6: Intervention: 0 - 7-10: Intervention: 4 Control: 216 P=0.159

Perinatal mortality Intervention: 1 (20.0%) Control: 11 (4.8%) P=0.23

|

|

|

Bousleiman, 2022 |

Retrospective secondary analysis of prospective observational caesarean registry dataset.

Setting and country: Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York City, USA.

Source of funding: A.M.F. is supported by a career development award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Women ≥37 weeks of gestational age at delivery, no more than one prior caesarean. Women who underwent emergency caesarean delivery. Of women with prior caesarean, only those with prior transverse or unknown incision were included

Exclusion criteria: Women with >1 prior caesarean, multiple gestations, and stillbirth, pregnancies resulting in neonates with major congenital anomalies or birthweight <2.500 g. Of women with prior caesarean, women with prior T.J. and vertical incisions were excluded.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 2751 Control: 2009

Important prognostic factors: Maternal age: - <18: Intervention: 191 Control: 79 - 18-24: Intervention: 1003 Control: 707 - 25-34: Intervention: 1179 Control: 917 - 35-39: Intervention: 296 Control: 243 - >39: Intervention: 82 Control: 63

Prenatal care: Intervention: 2684 Control: 1965

Labor induction: Intervention: 188 Control: 246

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported. |

Risk for cord pH ≤7.0 (present): Intervention: 150 (3.7%) Control: 48 (1.2%)

Risk for cord pH ≤7.1 (present): Intervention: 399 (9.9%) Control: 149 (3.7%)

Risk for umbilical artery cord pH ≤7.0 (present): Intervention: 119 (3.5%)

Risk for Apgar score ≤6 at 5-minutes (yes): Intervention: 165 (2.9%) Control: 70 (1.2%)

Risk for Apgar score ≤5 at 5-minutes (yes): Intervention: 97 (1.7%) Control: 41 (0.7%) |

|

|

Grobman, 2018 |

Secondary analysis of an observational cohort

Setting and country: 25 medical centers of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, USA.

Source of funding: Grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Center for Research Resources.

Conflicts of interest: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Term, singleton, nonanomalous gestation in the cephalic presentation, no prior CD, intended to labor in de current pregnancy (no indications for caesarean such as human immunodeficiency virus, active herpes, placental previa, or prior myomectomy), and subsequently underwent an intrapartum CD.

Exclusion criteria: Presented to labor and delivery with nonreassuring fetal status, as it could not be known for what duration of time the nonreassuring status had existed, indication for caesarean was an abruption or cord prolapse, data from women in whom either the time for decision for caesarean or insicision at caesarean was lacking in the medical record, or in whom DTI time was so long as to be unlikely in actuality.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 1171 Control: 2311 Total: 3482

Important prognostic factors: Not reported for DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes.

Age n (%): <20: 157 (4.5%) 20-24.9: 675 (19.4%) 24.9-29.9: 907 (26.0%) 30-34.9: 943 (27.1%) ≥35: 800 (23.0%)

Indication for caesarean: Arrest disorder: 2069 (59.4%) Nonreassuring fetal status: 1412 (40.6%)

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Incision time (DTI) ≤30 minutes. |

Decision to Incision time (DTI) >30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not applicable.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not applicable.

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable. |

pH <7.0: Intervention: 30 (2.6%) Control: 12 (0.5%)

Apgar <5 at 5 min: Intervention: 12 (1.0%) Control: 9 (0.4%)

Death: Intervention: 2 (0.2%) Control: 0 (0%)

NICU admission: Intervention: 184 (15.7%) Control: 258 (11.2%) |

Use of DTI instead of DDI |

|

Heller, 2017 |

Secondary analysis of perinatal survey data

Setting and country: Institute for Quality Assurance and Transparency in Healthcare, Berlin, Germany.

Source of funding: Not reported.

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Heller has received reimbursement of conference fees and travel expenses from KelCon GmbH. The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists. |

Inclusion criteria: Newborns with gestational age of 24-45 completed weeks of gestation, if one of the following indications for emergency caesarean section applied: - abnormal cardiotocography (CTG) findings - abnormal fetal heart rate - asphyxia detected by fetal blood analysis.

Exclusion criteria: Emergency caesarean section with DDI of >3 hours, stillbirths with time of death prior to admission to hospital or prior to delivery or unknown, newborns with congenital malformations.

N total at baseline: Total: 39291 Intervention: 39171 (99.7%) Control: 120 (0.3%)

Important prognostic factors: Not reported for DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes.

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not applicable.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not applicable.

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable. |

Death in hospital: Intervention: 224 Control: 1 Odds ratio DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes: OR 0.66 (95%CI 0.09 to 4.89), in favour of DDI ≤30 minutes.

5-minute Apgar score <7: Intervention: 3308 Odds ratio DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes: OR 0.67 (95%CI 0.37 to 1.20), in favour of DDI ≤30 minutes.

Arterial cord blood pH <7.0: Intervention: 1761 Odds ratio DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes: OR 0.70 (95%CI 0.32 to 1.52), in favour of DDI ≤30 minutes. |

For suspected or confirmed asphyxia.

Death in hospital adjusted for: adjusted for: sex (female vs. other), multiple birth status (single birth vs. other), gestational age (24–31, 32–36, reference ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation), presentation (cephalic vs. other), maternal BMI (<20, 20-24, vs. >25), year of birth (2009 vs. other).

5-minute Apgar score <7 adjusted for: sex (female vs. other), multiple birth status (single birth vs. other), developmental status (growth retardation vs. other), gestational age (24–31, 32–36, reference ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation), presentation (cephalic vs. other), anesthesia (general vs. other), maternal BMI (<20, 20-24, 25-29 vs. >30), previous caesarean delivery (status post caesarean section vs. other), parity (first birth vs. other), year of birth (2008, 2014 vs. other). |

|

Kitaw, 2021 |

Prospective cohort study

Setting and country: Bahir Dar city public hospitals in the Amhara region, Ethiopia.

Source of funding: No specific funding was received by the authors.

Conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: All women who underwent emergency caesarean section (EmCS) during the study period.

Exclusion criteria: Women who underwent EmCS with a preterm fetus, uterine rupture before the decision, intra-uterine fetal death, and fetuses with gross congenital anomalies.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 26 Control: 156 Total: 182

Important prognostic factors: Not reported for DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes.

Age n (%): <20: 4 (2.2%) 20-24: 51 (28%) 25-29: 62 (34%) 30-34: 44 (23.6%) ≥35: 21 (11.5%)

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not applicable.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not applicable.

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable.

99.45% response rate. |

Fifth minute APGAR score <7: Intervention: 6 Control: 26 OR 0.6 (95%CI 0.2 to 1.2), in favour of DDI >30 minutes.

Admission to NICU: Intervention: 5 Control: 44 OR 1.6 (95%CI 0.5 to 4.5), in favour of DDI ≤30 minutes. |

|

|

Le Mitouard, 2020 |

Observational study

Setting and country: Association des Utilisateurs du Réseau Obstétrico-pediatrique Regional, 26 public and private maternity units, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France.

Source of funding: Not reported.

Conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Prospectively included cases of caesareans performed as code orange emergencies or code red extreme emergencies, regardless of the type of pregnancy or fetal presentation.

Exclusion criteria: Code green (no short-term threat) has been described but was not the subject in this study.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 178 Control: 176

Important prognostic factors: Not reported for DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes.

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not applicable.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not applicable.

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable.

|

5-min Apgar 3: Intervention: 1 (0.6%) Control: 0 P=1

pH <7: Intervention: 3/153 (2%) Control: 3/142 (2.1%) P=1

Early death: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

|

Code orange (emergency caesarean section) taken into account, code red (extreme emergency caesarean section) not taken into account. |

|

Mishra, 2018 |

Observational study

Setting and country: Tertiary level government medical college teaching hospital, Chhattisgarh, India.

Source of funding: Not reported.

Conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women with single live foetus in pregnancy between 37 and 42 weeks with category I or category II indications (category I: immediate threat to life of woman or foetus, category II: maternal or foetal compromise but not immediate life-threatening).

Exclusion criteria: Women with category III or IV (category III: needing early delivery but no foetal or maternal compromise, category IV: planned for elective LSCS), known congenital foetal anomaly and medical complications of pregnancy.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 80 Control: 400 Total: 480

Important prognostic factors: Not reported for DDI ≤30 minutes vs >30 minutes.

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Till discharge from hospital.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not applicable.

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable.

|

NICU number (%): Intervention: 10 (12.5%) Control: 76 (19%)

Apgar <7 at 5-minutes number (%): Intervention: 10 (12.5%) Control: 75 (18.75%)

Neonatal death number (%): Intervention: 5 (6.25%) Control: 36 (9.5%)

|

|

|

Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022 |

Retrospective study

Setting and country: Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Source of funding: Supported by a grant from the Siriraj Research Development Fund.

Conflicts of interest: Not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Pregnant women who had an emergency caesarean delivery for category III FHR tracing with code blue activation.

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 246 Control: 8

Important prognostic factors: Age, mean ± SD: Intervention: 29.8 ± 6.6 Control: 27.1 ± 5.4

Gestational age at delivery (wk), mean ± SD: Intervention: 37.9 ± 2.9 Control: 37.2 ± 2.6

Time of decision (during office hours): Intervention: 86 (35.0%) Control: 3 (37.5%)

Type of anesthesia (general): Intervention: 231 (93.9%) Control: 7 (87.5)

Groups were comparable at baseline. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not applicable.

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable.

|

5-minute Apgar score <7: Intervention: 28 (11.4%) Control: 2 (25.0%) P=0.241

Umbilical cord arterial pH <7.2: Intervention: 93 (43.3%) Control: 2 (25.0%) P=0.472

Umbilical cord arterial pH, mean ± SD: Intervention: 7.18 ± 0.14 Control: 7.17 ± 0.18 P=0.899

NICU admission: Intervention:36 (14.6%) Control: 2 (25.0%) P=0.342

Neonatal death: Intervention: 6 (2.4%) P=1.000

|

|

|

Tashfeen, 2017 |

Cross-sectional study

Setting and country: Nizwa Hospital, Nizwa, Oman.

Source of funding: No funding received.

Conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: All women with singleton pregnancies delivered by emergency CS procedures due to fetal distress, antepartum haemorrhage or umbilical cord prolapse.

Exclusion criteria: Women with multiple pregnancies or pre-term deliveries.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 105 Control: 141 Total: 246

Important prognostic factors: Not reported.

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not applicable.

Incomplete outcome data: Not applicable.

|

Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU) admissions: Intervention: 3 (2.9%) Control: 32 (22.7%) P<0.001

Apgar score at five minutes <7: Intervention: 2 (1.9%) Control: 39 (27.7%) |

|

|

Temesgen, 2020 |

Prospective cohort study

Setting and country: Gondar University Specialized Hospital, Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia.

Source of funding: Funding by College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar. The University of Gondar had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: All clients who underwent category-1 emergency C/S delivery under both general and regional anaesthesia.

Exclusion criteria: All clients who underwent category 1-emergency C/S with preterm fetus, uterine rupture before decision, refused to give consent and fetus with gross congenital anomaly.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 32 Control: 131 Total: 166

Important prognostic factors: Number of previous C/S (0/1/2/≥3): Intervention: 29/0/2/1

Time of decision (day): Intervention: 14 Control: 87

Type of anaesthesia (regional): Intervention: 26 Control: 121

Groups comparable at baseline: not reported. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) ≤ 30 minutes. |

Decision to Delivery Interval (DDI) > 30 minutes. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not applicable.

Incomplete outcome data: Total: 3

Response rate 98.2%

|

APGAR score at 5th minute <7: Intervention: 5 (15.6%) Control: 13 (9.9%) OR 1.68 (95%CI 0.55 to 5.12), in favour of DDI >30 minutes.

NICU admission: Intervention: 2 (6.2%) Control: 6 (4.6) OR 0.52 (95%CI 0.11 to 2.38), in favour of DDI ≤30 minutes.

Neonatal death: Intervention: 1 (3.1%) Control: 3 (2.3%) OR 1.38 (95%CI 0.14 to 13.69), in favour of DDI >30 minutes.

|

Category 1 emergency caesarean delivery. |

Risk of Bias table: update 2023 (n=11)

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables? |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed? |

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Ayele, 2021 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were selected from registries from four hospitals. |

Definitely yes

Reason: DDI time was measured in the hospital and registered in patient records. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably yes

Reason: Possible confounding factors retrieved from the health care birth register, and medical records of maternal files. |

Probably yes

Reason: Variables that displayed a relationship in binary and multivariable logistic regression analysis and with P-values less than 0.20 were incorporated into multivariable logistic regression analysis model. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital and are retrieved from medical records of maternal files. |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

LOW (all outcome measures) |

|

Bello, 2015 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were prospectively selected from the population of a University college hospital. |

Definitely yes

Reason: DDI times were measured in the hospital. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably no

Reason: No information about measurement of possible confounding factors. |

Probably no

Reason: Only perinatal mortality was taken into account in multivariate regression. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital.

|

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) |

|

Bousleiman, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Petients were selected from a registry dataset. |

Definitely yes

Reason: DDI times were registered in medical records. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably no

Reason: No information about measurement of possible confounding factors. |

Probably no

Reason: Associations with outcome measures of interest were not corrected for possible confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital and are retrieved from the registry dataset. |

Probably no

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. Data were not available for significant proportions of cord gas values. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures), HIGH (cord pH) |

|

Grobman, 2018 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were selected from a registry dataset. |

Definitely yes

Reason: DDI times were registered in medical records. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably no

Reason: No information about measurement of possible confounding factors. |

Probably no

Reason: Associations with outcome measures of interest were not corrected for possible confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital and are retrieved from medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) |

|

Heller, 2017 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were selected from data pool of all inpatient deliveries in Germany. |

Definitely yes

Reason: DDI times were retrieved from German Perinatal Survey data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably yes

Reason: Possible confounding factors retrieved from German Perinatal Survey data. |

Probably yes

Reason: Risk adjustment models based on risk factors discussed in literature and documented in the perinatal survey were used for the analysis. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital and are retrieved from the perinatal survey. |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

LOW (all outcome measures) |

|

Kitaw, 2021 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were prospectively selected from a selected cohort from three hospitals. |

Probably yes

Reason: DDI times were measured and registered in the hospitals. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably no

Reason: No information about measurement of possible confounding factors.

|

Probably no

Reason: Associations with outcome measures of interest were not corrected for possible confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data reported. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) |

|

Le Mitouard, 2020 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were prospectively selected from 26 public and private maternity units. |

Probably yes

Reason: DDI times were measured and registered in the hospitals.

|

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably no

Reason: No information about measurement of possible confounding factors.

|

Probably no

Reason: Associations with outcome measures of interest were not corrected for possible confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital. |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data reported. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) |

|

Mishra, 2018 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were selected from a medical teaching hospital registry. |

Definitely yes

Reason: DDI times measured in the hospital and were retrieved from the registriy. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably no

Reason: No information about measurement of possible confounding factors.

|

Probably no

Reason: Associations with outcome measures of interest were not corrected for possible confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital. |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data reported. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) |

|

Sunsaneevithayakul, 2022 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were selected from electronic medical records of an obstetric hospital unit. |

Definitely yes

Reason: DDI times were retrieved from electronic medical records. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably yes

Reason: Possible confounding factors retrieved from electronic medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: A stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate possible confounding factors. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were retrieved from electronic medical records. |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data reported. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

LOW (all outcome measures) |

|

Tashfeen, 2017 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were selected from a hospital registry. |

Probably yes

Reason: DDI times were measured in the hospital. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably no

Reason: No information about measurement of possible confounding factors.

|

Probably no

Reason: Associations with outcome measures of interest were not corrected for possible confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital. |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data reported. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) |

|

Temesgen, 2020 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Patients were prospectively selected in a hospital. |

Probably yes

Reason: DDI times were measured in the hospital. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcome measures of interest were outcomes in the newborn. |

Probably no

Reason: No information about measurement of possible confounding factors. |

Probably no

Reason: Associations with outcome measures of interest were not corrected for possible confounders. |

Probably yes

Reason: Outcomes were measured in the hospital. |

Probably yes

Reason: Short term measurement of outcomes. No missing outcome data reported. |

Not applicable

Reason: No co-interventions. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Andersen BR, Ammitzbøll I, Hinrich J, Lehmann S, Rinste CV, Løkkegaard ECL, Tolsgaard MG. Using machine learning to identify quality-of-care predictors for emergency caesarean sections: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2022 Mar 7;12(3):e049046. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049046. PMID: 35256439; PMCID: PMC8905885. |

Not conform PICO: wrong outcome measures

|

|

Ayeni OM, Aboyeji AP, Ijaiya MA, Adesina KT, Fawole AA, Adeniran AS. Determinants of the decision-to-delivery interval and the effect on perinatal outcome after emergency caesarean delivery: a cross-sectional study. Malawi Med J. 2021 Mar;33(1):28-36. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v33i1.5. PMID: 34422231; PMCID: PMC8360283. |

Not conform PICO: Wrong DDI comparison

|

|

Bhatia K, Columb M, Bewlay A, Tageldin N, Knapp C, Qamar Y, Dooley A, Kamath P, Hulgur M; collaborators. Decision-to-delivery interval and neonatal outcomes for category-1 caesarean sections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2021 Aug;76(8):1051-1059. doi: 10.1111/anae.15489. Epub 2021 Apr 23. PMID: 33891311; PMCID: PMC8251307. |

Not conform PICO: wrong comparison (not comparing DDIs)

|

|

Canelón SP, Boland MR. Not All C-sections Are the Same: Investigating Emergency vs. Elective C-section deliveries as an Adverse Pregnancy Outcome. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2021;26:67-78. PMID: 33691005. |

Not conform PICO: wrong population (not only emergency), no DDI comparison |

|

Gonzalez Fiol A, Meng ML, Danhakl V, Kim M, Miller R, Smiley R. A study of factors influencing surgical caesarean delivery times in an academic tertiary center. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2018 May;34:50-55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2017.12.010. Epub 2018 Jan 6. PMID: 29502992; PMCID: PMC6277973. |

Not conform PICO: wrong comparison (primary vs secondary vs tertiary c-section), wrong outcome (operation time) |

|

Gupta S, Naithani U, Madhanmohan C, Singh A, Reddy P, Gupta A. Evaluation of decision-to-delivery interval in emergency caesarean section: A 1-year prospective audit in a tertiary care hospital. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2017 Jan-Mar;33(1):64-70. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.202197. PMID: 28413274; PMCID: PMC5374832. |

Not conform PICO: outcome measures not differentiated for DDI

|

|

Hirani BA, Mchome BL, Mazuguni NS, Mahande MJ. The decision delivery interval in emergency caesarean section and its associated maternal and fetal outcomes at a referral hospital in northern Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017 Dec 7;17(1):411. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1608-x. PMID: 29212457; PMCID: PMC5729006. |

Not conform PICO: no clear distinction between groups for DDI. |

|

Hughes NJ, Namagembe I, Nakimuli A, Sekikubo M, Moffett A, Patient CJ, Aiken CE. Decision-to-delivery interval of emergency caesarean section in Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 May 27;20(1):324. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03010-x. PMID: 32460720; PMCID: PMC7251662. |

Not conform PICO: no comparison between DDIs

|

|

IGWE, P. C., EGEDE, J. O., OGAH, E. O., ANIKWE, C. C., NWALI, M. I., & LAWANI, L. O. (2021). Association and Determinants of Decision-Delivery Interval of Emergency Caesarean Sections and Perinatal Outcome in a Tertiary Institution. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research, 15(3). |

Not conform PICO: wrong P, wrong I (only 1% within 30 min)

|

|

Kinsella SM. An audit of the effect of case selection on compliance with a 30-minute audit standard for decision-to-delivery interval at category 1 caesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2021 Nov;48:103214. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2021.103214. Epub 2021 Aug 17. PMID: 34500189. |

Not conform PICO: wrong outcome measures

|

|

Kitaw TM, Limenh SK, Chekole FA, Getie SA, Gemeda BN, Engda AS. Decision to delivery interval and associated factors for emergency caesarean section: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021 Mar 20;21(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03706-8. PMID: 33743626; PMCID: PMC7981954. |

Not conform PICO: wrong outcome measures

|

|

Lafitte AS, Vardon D, Morello R, Lecerf M, Stewart Z, Dreyfus M. Peut-on diminuer le délai décision-extraction des césariennes en urgence en optimisant l’architecture des locaux ? [Can we reduce the decision-to-delivery interval in case of emergency caesarean sections by optimizing the premises' architecture?]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2017 Nov;45(11):590-595. French. doi: 10.1016/j.gofs.2017.09.002. Epub 2017 Oct 27. PMID: 29111291. |

Not conform PICO: wrong comparison (before and after moving unit)

|

|

Obsa MS, Shanka GM, Menchamo MW, Fite RO, Awol MA. Factors Associated with Apgar Score among Newborns Delivered by Caesarean Sections at Gandhi Memorial Hospital, Addis Ababa. J Pregnancy. 2020 Jan 6;2020:5986269. doi: 10.1155/2020/5986269. PMID: 32395344; PMCID: PMC7199625. |

Not conform PICO: wrong comparison (low vs high Apgar score)

|

|

Oppong SA, Tuuli MG, Seffah JD, Adanu RM. Is there a safe limit of delay for emergency caesarean section in Ghana? Results of analysis of early perinatal outcome. Ghana Med J. 2014 Mar;48(1):24-30. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v48i1.4. PMID: 25320398; PMCID: PMC4196525. |

Not conform PICO: wrong comparison (imminent threat vs no imminent threat)

|

|

Spain JE, Tuuli M, Stout MJ, Roehl KA, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Time from uterine incision to delivery and hypoxic neonatal outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2015 Apr;32(5):497-502. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396696. Epub 2014 Dec 24. PMID: 25539409. |

Not conform PICO: wrong comparison: time from uterine incision to delivery

|

|

Tebeu PM, Tchamte CN, Kamgaing N, Antaon JSS, Mawamba YN. Determinants of the decision to incision interval in case of emergency caesarean section in Yaoundé' hospitals. Afr Health Sci. 2022 Jun;22(2):511-517. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v22i2.59. PMID: 36407365; PMCID: PMC9652684. |

Not conform PICO: wrong outcome measures |

|

Tucker L, Frühauf A, Dumbuya I, Muwanguzi P, Lado M, Lavallie D, Sheku M, Kachimanga C. Reducing Decision to Incision Time Interval for Emergency Caesarean Sections: 24 Months' Experience from Rural Sierra Leone. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Aug 13;18(16):8581. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168581. PMID: 34444330; PMCID: PMC8392021. |

Not conform PICO: wrong outcome measures

|

|

Väänänen AJ, Kainu JP, Eriksson H, Lång M, Tekay A, Sarvela J. Does obesity complicate regional anesthesia and result in longer decision to delivery time for emergency caesarean section? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2017 Jul;61(6):609-618. doi: 10.1111/aas.12891. Epub 2017 Apr 17. PMID: 28417459. |

Not conform PICO: wrong comparison (BMI <30 vs 30-35 vs >35)

|

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 17-10-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 04-09-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten die patiënten die in een ziekenhuis een spoedingreep moeten ondergaan.

Werkgroep

- Dhr. dr. P.H.W. (Pieter) Lubbert, chirurg, NVvH (voorzitter)

- Dhr. dr. H. (Hilko) Ardon, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Dhr. dr. L.F.M. (Ludo) Beenen, radioloog, NVvR

- Dhr. drs. V.A. (Victor) van Bochove, intensivist, NVIC

- Mevr. prof. dr. M.A. (Marja) Boermeester, gastro-intestinale / oncologisch chirurg, NVvH

- Dhr. dr. E.M. (Eelke) Bos, neurochirurg, NVvN

- Mevr. N.H.B.C. (Nicole) Dreessen, Afdelingshoofd OK, LVO

- Dhr. prof. dr. L. (Leander) Dubois, MKA-chirurg, NVMKA

- Dhr. drs. P.G. (Peter) van Etten, oogarts, NOG

- Dhr. drs. A.J.P. (Peter) Joosten, orthopedisch chirurg, NOV

- Dhr. dr. S.V. (Steven) Koenen, gynaecoloog, NVOG

- Dhr. dr. R.A.F. (Rob) de Lind van Wijngaarden, cardio-thoracaal chirurg, NVThorax

- Mevr. dr. E.C. (Lise) van Turenhout, anesthesioloog, NVA

- Dhr. drs. M.P.M. (Martijn) Verhagen, AIOS Spoedeisende Geneeskunde, NVSHA

- Mevr. E.C. (Esen) Doganer, beleids/projectmedewerker, K&Z (tot maart 2023)

- Mevr. A. (Anne) Swinkels, beleids/projectmedewerker, K&Z (tussen maart 2023 tot september 2023)

- Mevr. M. (Marjolein) Jager, beleids/projectmedewerker, K&Z (vanaf september 2023)

Klankbordgroep

- Dhr. dr. P.M. (Peter-Paul) Willemse, uroloog, NVU

- Mevr. dr. ir. M.E. (Maartje) Zonderland, directeur Zonderland & Van Zeijl

Met ondersteuning van:

- Mevr. dr. C.T.J. (Charlotte) Michels, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. drs. E.R.L. (Evie) Verweg, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroep |

Functienaam en werkgever |

Nevenfunctie |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Pieter Lubbert (voorzitter) |

Chirurg, Heelkunde Friesland |

Bestuurslid Heelkunde Friesland Groep |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Eelke Bos |

Neurochirurg, ErasmusMC |

Geen |

*Consultant voor Brainlab A.G. (www.brainlab.com). *Co-PI van de BMP4 Fase 1 studie gefinancierd door Stemgen. |

Geen restrictie |

|

Hilko Ardon |

Neurochirurg, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis |

*Voorzitter van de Kwaliteitscommissie van de NVvN *Bestuurslid van de NVvN |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Leander Dubois |

*MKA chirurg, AmsterdamUMC en St. Antonius ziekenhuis. *Hoogleraar Maxillofaciale Traumatologie, Universiteit van Amsterdam |

Aandeelhouder P MED (start-up tandheelkundige implantaten; eind 2023 failliet) |