Sociale vaardigheidstraining

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van sociale vaardigheidstraining (SOVA-training) bij kinderen en jongeren met autisme?

Aanbeveling

Bied sociale vaardigheidstraining niet routinematig aan.

Bied ouderbegeleiding en advisering op school aan, gericht op het stimuleren van sociale ontwikkeling van hun kind/leerling. Stem hierin af met de leerkracht en het ondersteuningsteam van de school.

Weeg, indien sociale vaardigheidstraining toch wordt aangeboden, enerzijds de mogelijke effectiviteit en anderzijds de inspanning en mogelijke faalervaring voor het individu af. Bespreek deze afweging met het kind en/of de ouder(s) of verzorger(s).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In de literatuur is gezocht naar de effectiviteit van sociale vaardigheidstrainingen (SOVA) in de behandeling van kinderen en jongeren met autisme. In totaal zijn er één systematische review (met daarin twaalf relevante RCTs) en zes aanvullende RCTs gevonden over verschillende SOVA-trainingen bij kinderen en jongeren met autisme. Naast enkele methodologische beperkingen, zoals het feit dat geen enkele studie geblindeerd was, waren de studiepopulaties relatief klein. De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten – sociale prestaties, interactie en kwaliteit van vriendschappen – en daarmee ook de algehele bewijskracht is beoordeeld als zeer laag. Er kunnen op basis van de literatuur geen harde conclusies getrokken worden over de waarde van SOVA-training bij kinderen en jongeren met autisme.

Hoewel het bewijs voor SOVA-training beperkt is, blijkt uit de praktijk dat kinderen en jongeren met autisme steun nodig hebben om succesvol te socialiseren met hun leeftijdsgenoten. Andersom hebben leeftijdsgenoten hulp nodig om succesvol te werken, spelen en interacteren met kinderen en jongeren met autisme. Een cruciaal aspect voor kinderen en jongeren met autisme om volwaardig deel te nemen aan zowel de sociale als leeromgeving in de school, is het begrijpen en het accepteren van andere kinderen/jongeren en het oefenen van sociale vaardigheden. Zeker ook zo belangrijk is dat dit twee kanten op werkt en hun leeftijdsgenoten hier ook in oefenen (‘double empathy problem’) (Fuentes, 2020).

Het stelt ons voor het dilemma dat kinderen en jongeren met autisme ondersteuning nodig hebben in hun sociale ontwikkeling maar het nut van SOVA-training niet aangetoond kan worden. Het is ook niet duidelijk of en wat wel effectieve componenten uit SOVA-trainingen zijn en of er programma’s zijn die beter aansluiten op een bepaalde subgroep. Er kunnen daarom geen adviezen gegeven worden gebaseerd op wetenschappelijke evidentie. De werkgroep doet op basis van klinische ervaring en professionele mening de volgende aanbevelingen. Het groepsgewijze aanbod van SOVA-training heeft de voorkeur boven een individueel programma door de mogelijkheid tot oefening. Wel ben je daarin afhankelijk van het aanbod. Wat we weten is dat een interventie voor kinderen en jongeren met autisme gericht op de sociale ontwikkeling moet zijn aangepast aan het ontwikkelingsniveau en als doel moet hebben dat de omgeving meer begrip, sensitiviteit en responsiviteit ontwikkelt naar hoe het kind met anderen omgaat en communiceert (NICE, 2021). Alleen als de omgeving goed aansluit op waar het kind is in zijn sociaal-emotionele ontwikkeling kan een interventie beklijven. Zo kan een kind met autisme ondertiteling op sociaal gebied nodig hebben die passend is bij een jongere kalenderleeftijd. Het is goed voor te stellen dat SOVA-trainingen door hun gestandaardiseerde aanpak onvoldoende aansluiten op de vaak nog jonge denkkaders op sociaal-emotioneel vlak bij het kind met autisme. Hierdoor kan de nadruk komen te liggen op het aanleren van gedragingen in plaats van het stimuleren van de ontwikkeling, hetgeen het toepassen van vaardigheden buiten de training in de weg staat.

Daarom is het gebruik van natuurlijke momenten gedurende de dagelijkse routines een aanbevolen strategie om sociale communicatie te bevorderen. Op deze manier wordt generalisatie van vaardigheden door de verschillende milieus heen gefaciliteerd (Zwaigenbaum, 2015).

De werkgroep concludeert dat hoewel er weinig wetenschappelijk bewijs is, er in de literatuur en de dagelijkse praktijk van ouders/verzorgers en clinici wel consensus is over de wenselijkheid van het stimuleren van de sociale ontwikkeling bij kinderen en jongeren met autisme. Vanuit de ervaring van mensen met autisme weten we dat teveel de nadruk op het aanleren van sociale vaardigheden averechts kan werken doordat dit bijdraagt aan het negatieve zelfbeeld niet goed te zijn zoals je bent en je gaat leren jezelf aan te passen.

Wanneer psycho-educatie heeft plaatsgevonden aan ouders/verzorgers en onderwijsomgeving, kan het nodig zijn om beiden nog meer handvatten te geven om de sociale ontwikkeling van het kind met autisme te stimuleren. De rol van de professional kan bestaan uit het coachen van sleutelfiguren in de omgeving van het kind. Deze sleutelfiguren kunnen immers gedurende de hele dag interventies toepassen om sociale ontwikkeling te faciliteren en moeilijkheden daarin te verminderen (advies ESCAP richtlijn 2020). Het gaat hier om opvoedingsvaardigheden als modeling (voordoen en toelichten van gedrag) en feedback, naast technieken gericht op communicatie, interactief spel en sociale routines (NICE 2021). De afstemming op het het kind en zijn ontwikkelingsniveau zijn hierbij cruciaal.Uit onderzoek weten we dat met name meisjes/ vrouwen kunnen neigen tot het maskeren van hun autisme en mooi weer kunnen spelen terwijl dat egodystoon is en veel energie kost. Mogelijk kan te veel modeling hier aan bijdragen en is het goed deze balans in de gaten te houden.

Het herkennen en aanmoedigen van individuele sterke kanten kan daarnaast helpen om een positieve omgeving te creëren voor het kind met autisme en diens familie. Sterkten kunnen gebruikt worden om zwakten te compenseren. Zo kunnen goede visuele vaardigheden effectief zijn in de communicatie bij kinderen en jongeren met minder goede verbale vaardigheden. Speciale interesses (bijvoorbeeld feiten, nummers, computers of dieren, strips, bekenden, muziek, knutselen, koken, natuur) kunnen worden gebruikt voor het verbeteren van schoolse en praktische vaardigheden maar ook voor het voeden van sociale contacten (ESCAP 2020).

Op basis van de bovenstaande punten, ziet de werkgroep allereerst een rol voor ouderbegeleiding en advisering op school (leerkracht en ondersteuningsteam), indien stagnatie van de sociale ontwikkeling zich voordoet. Scholen kunnen hiervoor een beroep doen op de jeugdgezondheidszorg. Deze kan met de school meedenken over benodigde aanpassingen en aanpak op de school in afstemming met het kind en zijn ouders en ook hoe medeleerlingen mee te nemen in het begrijpen van het kind met autisme. De jeugdgezondheidszorg kan naar de GGZ verwijzen wanneer intensievere ondersteuning van school of ouders nodig is.

Er zijn geen aanwijzingen dat het routinematig aanbieden van SOVA-training zinvol is omdat er uit onderzoeken onvoldoende blijkt dat deze bijdraagt aan toepassing van vaardigheden in situaties buiten de training.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Een SOVA-training beoogt vaardigheden tijdens sociale interacties te verbeteren en daarmee het zelfvertrouwen van kinderen of jongeren met autisme te vergroten (Laugeson, 2012; Neef, 2010; Tse, 2007; Volkan, 1998). Het doel van een SOVA-training sluit daarmee goed aan op de wens van veel kinderen en jongeren met autisme en hun ouders/verzorgers, namelijk dat deze kinderen/jongeren met meer vertrouwen aan sociale interactie kunnen deelnemen. Vanuit klinische ervaring ervaart de werkgroep dat het toepassen van aangeleerde vaardigheden in nieuwe situaties bij kinderen en jongeren met autisme niet vanzelfsprekend is. Het is daarom van belang met ouders/verzorgers en kind een goede afweging te maken. Levert deze investering die ouder en kind doen in een SOVA-training voldoende op? In de praktijk wordt nogal eens gezien dat de SOVA-training wordt aangeboden zonder goed af te stemmen op het kind zelf. Soms zijn de verwachtingen voor het kind ook niet voldoende helder. Zeker gezien het gebrek aan bewijskracht voor de effectiviteit van SOVA-trainingen, is het verstandig de mening van de patiënt in de afweging mee te nemen. Dit vergroot de motivatie en de kans op effect van de training. Wanneer een SOVA-training niet het gewenste effect oplevert, kan dit een faalervaring zijn voor de patiënt en daarmee belemmerend werken voor toekomstige hulpverlening.

Ook moet rekening worden gehouden met de mogelijkheid dat een SOVA-training de boodschap aan een kind kan geven dat hij of zij afwijkt. Kinderen en jongeren met autisme kunnen het idee krijgen dat ‘zij’ het probleem zijn en moeten leren om met anderen om te gaan. ‘Zij’ moeten zich dan aanpassen, terwijl de sociale problemen ook sterk een ‘double empathy’ probleem zijn. Als de training op school aan een geselecteerde groep wordt gegeven zou dit mogelijk ook stigmatiserend kunnen werken. Door onbegrip kunnen zij immers binnen de groep negatief gelabeld worden met de gevolgen van dien.

Bovenstaande risico’s van een SOVA-training, waardoor deze mogelijk niet oplevert waar hij voor bedoeld is, nemen niet het belang van de wens achter SOVA-training weg: het versterken van sociale vaardigheden. Naast of in plaats van SOVA-training kunnen alternatieven overwogen worden zoals vaktherapie. Bij een wens voor SOVA-training vanuit het kind, kan gekeken worden hoe de negatieve effecten hiervan zoveel mogelijk voorkomen kunnen worden en de kans op een succeservaring zoveel mogelijk aanwezig.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Verminderde sociale vaardigheden kunnen problemen veroorzaken op uiteenlopende levensdomeinen hetgeen direct of indirect kosten met zich mee kan brengen voor zowel de persoon die het betreft als de maatschappij en zorginstellingen. Verbetering van sociale vaardigheden zou dan logischerwijs een kostenreductie met zich meebrengen. Echter, bij de systematische search naar literatuur voor deze module komt geen eenduidig beeld naar voren van de effectiviteit van de beschreven interventies, evenmin van de kosteneffectiviteit ervan. Ook blijkt uit de gevonden artikelen onvoldoende of er sprake is van subgroepen waarvoor met betrekking tot de kosten andere bevindingen gelden. De werkgroep kan dan ook geen conclusie trekken over de kosteneffectiviteit van SOVA-training.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

SOVA-trainingen worden op verschillende plaatsen uitgevoerd waaronder scholen en ggz-instellingen. Het merendeel van de in de literatuur beschreven interventies vergt veel organisatie, wat in sommige gevallen implementatie kan bemoeilijken. Naar verwachting vereist goede SOVA-training een intensieve samenwerking tussen zorgverleners, ouders/verzorgers en scholen, ook als de training in een ggz-instelling wordt uitgevoerd. Wanneer de training op school wordt uitgevoerd, brengt dit als aandachtspunt mee dat de uitvoering ten koste gaat van primaire schoolactiviteit, wat gefaciliteerd moet kunnen worden vanuit afdelings- en bestuursniveau.

Voor veel interventies geldt dat het effect mede afhangt van de motivatie van de doelgroep, die bij SOVA-training in een deel van de gevallen niet aanwezig zal zijn. Ouders/verzorgers en scholen kunnen kinderen en jongeren stimuleren tot ontwikkeling van sociale vaardigheden door in allerlei opzichten bij hen aan te sluiten en af te stemmen op individuele behoeften. Daarbij is kennis van autisme onontbeerlijk en hiertoe zal psycho-educatie hieraan vooraf moeten gaan. Ten slotte zijn de beschikbaarheid van de benodigde zorgverleners met vereist kennisniveau en kunde bepalend.

Er zijn aanwijzingen voor barrières aangaande de toegang tot zorg en inzet bij interventies, deze worden beschreven door Malik-Soni (2022). Hierbij kan gedacht worden aan invloed van sociale en culturele achtergronden (zie hiervoor ook de module Psycho-educatie) en de individuele ernst van autisme. Slechts beperkt wordt beschreven wat de invloed is van sociale klasse op toegang van de interventie. Eén studie (Chung, 2023) benadrukt bijvoorbeeld de brede toegankelijkheid van de training. In de setting van deze studie werd de training echter aangeboden in de vorm van een app. Het vermoeden is dat sociaaleconomische klasse invloed heeft op toegankelijkheid van SOVA-trainingen in de Nederlandse situatie. Bijvoorbeeld mensen die in armoede leven, geen werk hebben, hun kind zonder partner grootbrengen, en/of huisvestingsproblemen hebben ervaren mogelijk minder ruimte voor een dergelijke interventie.

Het in Nederland implementeren van de aanbevelingen zal vermoedelijk vooral inspanning vergen in het voldoen aan de randvoorwaarden: er moet al psycho-educatie en afstemming met het kind over motivatie hebben plaatsgevonden. Daarnaast moeten individuele doelen worden vastgesteld met het kind, en dienen ouders/verzorgers en school intensief te worden betrokken.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De werkgroep beoordeelt op basis van onderzoek en praktijk dat er te weinig evidentie bestaat om SOVA-training routinematig aan te bieden. Vanuit het ontwikkelingsperspectief van het kind met autisme is begrip en oefening van sociale vaardigheden zeker van belang, ook in de schoolcontext. Bij het gebruik van natuurlijke momenten gedurende de dag kan beter aangesloten worden op de ontwikkeling en behoeften van het kind dan bij een SOVA-training. Hierdoor ligt generalisatie van vaardigheden meer in het verschiet. Het heeft dan ook de voorkeur boven SOVA-training om /verzorgers en school te adviseren en te coachen om de sociale ontwikkeling van het kind door de dag heen te faciliteren. Hetgeen niet uitsluit dat bij gemotiveerde kinderen en jongeren SOVA-training aangeboden kan worden wanneer met bovenstaande overwegingen en beperkingen rekening wordt gehouden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het doel van sociale vaardigheidstraining (oftewel SOVA-training) is om kinderen en jongeren met autisme sociale vaardigheden aan te leren die hen beter in staat stellen contacten aan te gaan met leeftijdgenoten en/of volwassenen. Hiermee wordt bedoeld dat indien kinderen/ouders dat wenselijk achten, een verbreding van het vaardigheidsrepertoire wordt nagestreefd. Nadrukkelijk wordt niet bedoeld om toe te trainen naar een maatschappelijk opgelegde norm.

Autistische kinderen hebben immers net als kinderen en jongeren zonder autisme behoefte aan contact maar zijn vaak minder sociaal vaardig waardoor dit niet lukt. Daarnaast missen leeftijdsgenoten en volwassenen vaak de vaardigheden om goed aan te sluiten bij hen. Ook kan het ontbreken aan randvoorwaarden het contact in de weg staan, zoals de beschikbaarheid van ruimtes die niet te vol en rumoerig zijn.

Gebrek aan contact staat groei en ontwikkeling in de weg. Vriendschappen, bestaand uit het samen dingen doen, gedachten en gevoelens delen en aardige dingen doen voor elkaar, zijn zeker niet vanzelfsprekend bij autisme. SOVA-training richt zich op het trainen van dergelijke vaardigheden bij het kind met autisme.

SOVA-training wordt met regelmaat aangeboden in het reguliere onderwijs, het speciaal onderwijs, binnen jeugdzorg, jeugdteams, de zorg bij verstandelijke beperking, en binnen ggz-instellingen. Het varieert per school of instelling of SOVA-training gegeven wordt. SOVA-trainingen worden aangeboden voor verschillende leeftijdsgroepen, zowel voor kinderen in de hogere klassen van de basisschool als op de middelbare school en voor (jong)volwassenen. SOVA-trainingen worden veel toegepast om alledaagse sociale vaardigheden te trainen, waaronder oogcontact maken, laten merken hoe je je voelt, complimenten geven en afspraken maken met leeftijdgenoten. SOVA-trainingen kennen een brede verscheidenheid in hun aanpak waaronder groepstrainingen, e-health programma’s, programma’s met een cognitief-gedragstherapeutische aanpak of middels peer support (ESCAP 2020). Tegelijkertijd is er veel overeenkomst tussen verschillende trainingen, zowel qua doel, als qua vaardigheden waarop die zich richten, als qua technieken waarmee ze dat doen (modeling, rollenspellen, huiswerk, gezamenlijke bijeenkomsten, etc).

Voorbeeld van een SOVA-training voor jongeren met autisme is PEERS (Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills) voor jongeren van 12-18 jaar (Idris, 2021). De PEERS-training is gericht op het maken en behouden van vrienden, hetgeen aansluit op de behoefte van veel jongeren met autisme. Het gaat hierbij om gespreksvaardigheden waaronder het mengen in een gesprek en het afronden van een gesprek, het kiezen van geschikte vrienden en afspreken met vrienden, gepast gebruik van humor en het omgaan met afwijzing, meningsverschillen, geruchten of roddels (Kenniscentrum kinder- en jeugdpsychiatrie, 2021).

Een andere training is de ToM (Theorie of Mind) training, een sociale vaardigheidstraining voor kinderen van 9 t/m 12 jaar met autisme die moeite hebben zich te verplaatsen in de gedachten en gevoelens van anderen, en die moeite hebben met het begrijpen van en omgaan met emoties en/of angstig en agressief zijn in sociale situaties. De ToM-training beoogt de ontwikkeling van het sociaal en emotioneel denken te stimuleren en kent ook een blended versie, de ToM-e (ZonMW 2017).

Hoewel zowel ouders/verzorgers als clinici soms de wens hebben kinderen en jongeren te ondersteunen in hun ontwikkeling op het gebied van sociale en communicatieve vaardigheden, is de vraag in wetenschappelijk onderzoek of het volgen van SOVA-training daaraan bijdraagt in situaties buiten de training. De kwestie die daarbij ook speelt, is in hoeverre SOVA-training aanzet tot het aanpassen van gedrag zonder dat dit uit de interne motivatie van het kind voortkomt. Dat past niet in het huidige tijdsgewricht gericht op inclusie en het verminderen van stigma. En vriendschappen onderhouden `omdat het zo hoort` kan ook veel energie kosten en stress geven.

De werkgroep wil in deze module dan ook meer zicht krijgen op de meerwaarde van SOVA-training in vergelijking met het niet aanbieden hiervan.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Social performance (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of social skills training on social performance when compared with waitlist control or usual care in children and adolescents with ASD.

Source: Gilmore, 2022*: Luckhardt, 2018.

*Including: Choque-Olsson, 2017; Corbett, 2016; Schohl, 2014; Freitag, 2016; White, 2013; Jonsson, 2019; Rabin, 2021; Shum, 2019; Vernon, 2018. |

2. Interaction (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of social skills training on interaction when compared with waitlist control in children and adolescents with ASD.

Source: Corbett, 2019; Shih, 2018; Ko, 2019. |

3. Quality of friendships (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of social skills training on quality of friendships when compared with waitlist control in children and adolescents with ASD.

Source: Gilmore, 2022*.

*Including: Schohl, 2014; Laugeson, 2009. |

4. Number of friends (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Social skills training may result in little to no difference in number of friends when compared with waitlist control or usual care in children and adolescents with ASD.

Source: Gilmore, 2022*.

*Including: Schohl, 2014; Laugeson, 2009; Matthews, 2018; Shum, 2019; Yoo, 2014. |

5. Social skills (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Social skills training may result in little to no difference in social skills when compared with waitlist control or usual care in children and adolescents with ASD.

Source: Gilmore, 2022*; Ashori, 2019; Dekker, 2019.

*Including: Choque-Olsson, 2017; Jonsson, 2019; Corbett, 2016; Shum, 2019; Schohl, 2014; Laugeson, 2009; Matthews, 2018; Rabin, 2021; Vernon, 2018. |

6. Quality of life (important), 7. Patient satisfaction (important)

|

no GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of social skills training on quality of life and patient satisfaction when compared with waitlist control or usual care in children and adolescents with ASD.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Gilmore (2022) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of group social skills interventions at improving social functioning in adolescents with congenital, acquired or developmental disabilities. The electronic databases PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PsycINFO, and Web of Science were searched with relevant search terms from inception to March 2020. Inclusion criteria were 1) RCTs evaluating group social skills interventions in adolescents (mean age 11-17 years) with acquired, congenital or developmental disabilities, 2) reporting of outcome measures addressing social knowledge, social competence or social participation, 3) availability of treatment manual for the intervention, and 4) comparison was no intervention or another intervention. Studies were excluded if 1) the group social skills training was delivered in schools only, 2) no English publication was available, and 3) the focus was on adolescents with a primary mental health disorder. A total of sixteen studies were included in the systematic review, of which twelve adhered to our selection criteria and PICO, and were therefore described and analyzed in the current literature analysis (Choque-Olsson, 2017; Jonsson, 2019; Corbett, 2016; Schohl, 2014; Laugeson, 2009; Matthews, 2018; Rabin, 2021; Shum, 2019; Yoo, 2014; Freitag, 2016; White, 2013; Vernon, 2018).

Ashori (2019) conducted an experimental study with pre-test post-test design and control group to examine the effect of video modeling on the social skills of children with ASD. A total of 24 male children aged 6-8 years with a diagnosis of ASD with high performance (IQ between 70-85) in the first or second grade of school were included. Children were excluded if 1) there was evidence of a neuro-developmental disorder except ASD, and/or 2) they currently followed a similar intervention program. Participants were randomly assigned to either the video modeling experimental group or the waitlist control group. This study was conducted at two elementary schools in Tehran, Iran, and did not receive funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit agency.

Corbett (2019) performed an RCT to examine the impact of SENSE Theater intervention on behavior and social cognition in youth with ASD. In total, 87 children aged 8-16 years with a diagnosis of ASD according to the DSM-5 and an IQ ≥70, participated. Children were excluded if, over the last six months, they displayed aggression defined as verbal or physical threats to harm other children or adults. Participants were randomly divided into the SENSE Theater intervention group or the waitlist control group. This study was conducted at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA. Funding was received from NIMH R34 MH097793 (Corbett), NICHD Grant to Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, a VKC Hobbs Discovery Award, and donations to SENSE Theater to assist some families with travel costs.

Dekker (2019) conducted an RCT to investigate the effectiveness of a manualized group social skills training for high-functioning children with ASD. A total of 122 high-functioning (IQ ≥80) children in the last two and half years of primary education with a diagnosis of ASD according to the DSM-IV-TR were included. Exclusion criteria were 1) physical condition affecting participation, and 2) child could not travel to the child mental health center for training. Participants were randomly assigned to the social skills training group, the social skills training with additional parent and teacher involvement group, or the care as usual group. The study was conducted at a child mental health center in Groningen, the Netherlands, and was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw).

Ko (2019) conducted a study to expand the evidence of the START socialization program for adolescents with ASD. This study was performed in the same sample of participants as the study conducted by Vernon (2018), which previously examined results from the parent and self-report survey measures. A total of 35 participants were randomized to either the START intervention program or the waitlist control group. The study was conducted in Santa Barbara, USA and was funded by the Organization for Autism Research.

Luckhardt (2018) performed a study on a subsample of the multicenter RCT conducted by Freitag (2016). Children and adolescents aged 8-20 years with a diagnosis of ASD participated in the SOSTA-net trial (Freitag, 2016) and were randomized to receive either add-on group-based social skills training SOSTA-FRA or treatment as usual. Participants of the study were included in the Frankfurt subsample of the full SOSTA-net trial. A total of 33 participants were included. Exclusion criteria were 1) IQ <70, 2) schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or any personality disorder as well as aggressive behavior 3) any severe neurological or medical condition interfering with group therapy, 4) group-based social skills training during the last 6 months prior to inclusion, and 5) in-patient treatment. The study was conducted at the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University Hospital Frankfurt, Germany. Funding was received from the German Research Foundation.

Shih (2019) performed a multisite RCT to examine the effectiveness of a social skills intervention called Remaking Recess (RR) in elementary school-age children with ASD. Children were included if 1) their parents and primary classroom teacher provided informed consent to participate, 2) they met the ADOS research criteria for ASD, 3) were aged 5-11 years, and 4) if they were included in a general education classroom for at least 51% of the school day. No exclusion criteria were reported. A total of eighty children met the inclusion criteria and were randomly assigned to either the RR intervention group or the waitlist control group. The study was conducted at three large urban school districts: 1) Los Angeles Unified School District, 2) School District of Philadelphia, and 3) Rochester City School District. This trial was supported by a grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services and NIMH K01MH1001099 (Locke).

Study characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1

|

KONTAKT plus standard care (extended) |

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Based on behavioral therapeutical principles and the social learning theory |

|

||||

Results

1. Social performance

Nine studies included by Gilmore (2022) reported on social performance (by using questionnaires), assessed by using the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) (range: 0-195) (Choque-Olsson, 2017; Corbett, 2016; Schohl, 2014; Freitag, 2016; White, 2013) or SRS-2 (range: 65-260) (Jonsson, 2019; Rabin, 2021; Shum, 2019; Vernon, 2018). In addition, Luckhardt (2018) also reported on social performance assessed by using the SRS. For all scales, higher scores indicate greater severity of social impairment. Choque-Olsson (2017), Jonsson (2019), Rabin (2021), Shum (2019) and Freitag (2016) provided change data from baseline to postintervention.

Data of two studies could not be pooled because the authors provided estimated marginal means (Corbett, 2016) or because data was provided based on if participants received the facial emotion recognition task or the biological motion task (Luckhardt, 2018).

- Corbett (2016) reported an estimated marginal mean (SD) of 73.53 (7.83) for the intervention group (n=17) and 80.23 (7.81) for the control group (n=16).

- For the facial emotion recognition task, Luckhardt (2018) reported a postintervention mean (SD) SRS Parent score of 92.6 (27.3) for the intervention group (n=17) and 94.5 (27.7) for the control group (n=14). Mean difference was -1.90 (95%CI -21.37 to 17.57) in favor of the intervention group, which was considered not clinically relevant. The authors reported a postintervention mean (SD) SRS Parent score of 88.0 (24.4) for the intervention group (n=17) and 96.6 (27.6) for the control group (n=14) for the sample that received the biological motion discrimination task. Mean difference was -8.60 (95%CI -27.14 to 9.94) in favor of the intervention group, which was considered not clinically relevant.

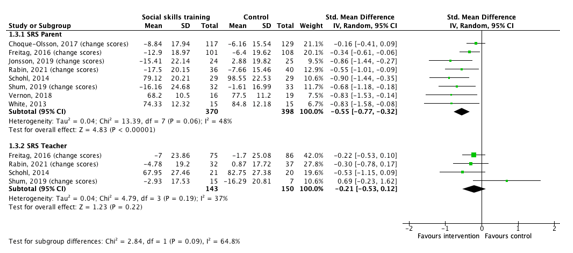

Figure 1 shows the pooled data. Both standardized mean differences (SMDs) are in favor of the social skills intervention. The SMD of the SRS Parent of -0.55 (95%CI -0.77 to -0.32) was considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. The effect of social skills training on social performance in children and adolescents with ASD (postintervention)

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

2. Interaction

Three studies reported on the outcome measure interaction (by observation), assessed by using the Peer Interaction Paradigm (PIP) (Corbett, 2019), the Playground Observation of Peer Engagement (POPE) time-interval coding system (Shih, 2018) and by performing video-recorded conversations (Ko, 2019).

- Corbett (2019) reported on interaction, defined as cooperative play and verbal interaction. The authors performed a 20-minute semi-structured interaction with the participant with ASD. Continuous timed-event coding of cooperative play (= percentage of time the participant was engaged in a reciprocal activity for enjoyment that involved the participation of ≥2 children) and verbal interaction (= engagement between ≥2 children including the participant with ASD that begins with a verbal overture and continues in a reciprocal sequence of to-and-from communication) was conducted.

- Shih (2018) reported on interaction, defined as joint engagement. The authors used the POPE time-interval coding system that identifies durations of joint engagement (e.g., playing a game or having a conversation) with peers.

- Ko (2019) reported on interaction, defined as questions asked, positive facial expressions and mutual engagement. Video-recorded conversations were systematically coded for each of these variables.

Table 2. Results on interaction

3. Quality of friendships

Two studies included in Gilmore (2022) reported on quality of friendships, assessed by using the Friendship Quality Scale (FQS) (Schohl, 2014; Laugeson, 2009). The FQS is a self-report measure to assess the quality of children’s and early adolescents’ friendships. Both studies used different versions of the FQS. Schohl (2014) used the FQS (range: 0-23) that consists of 23 yes/no questions from five different subscales. Laugeson (2009) used the FQS (range: 23-115) that consists of 23 items each answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ‘not true’ to 5 ‘really true’. For both versions, higher scores reflect better quality friendships.

- Schohl (2014) reported a mean (SD) FQS score of 82.45 (15.41) for participants in the social skills intervention group (n=29) and 82.65 (19.42) for participants in the control group (n=29). Mean difference was -0.2 (95%CI -9.22 to 8.82) in favor of the control group. This difference was considered not clinically relevant.

- Laugeson (2009) reported a mean (SD) FQS score of 17.2 (4.0) for participants in the social skills intervention group (n=17) and 16.6 (4.6) for participants in the control group (n=16). Mean difference was 0.60 (95%CI -2.35 to 3.55) in favor of the social skills intervention group. This difference was considered not clinically relevant.

4. Number of friends

Five studies included in Gilmore (2022) reported on number of friends, assessed using the Quality of Socialization Questionnaire (QSQ) or the previous version, namely the Quality of Play Scale (QPQ) (Schohl, 2014; Laugeson, 2009; Matthews, 2018; Shum, 2019; Yoo, 2014). The QSQ is a 12-item self- and caregiver-report measure adapted from the QPQ, of which two items assess the frequency of hosted and invited get-togethers over the previous month. Higher scores indicate participation in more hosted and invited get-togethers with friends. Results are presented in Table 3.

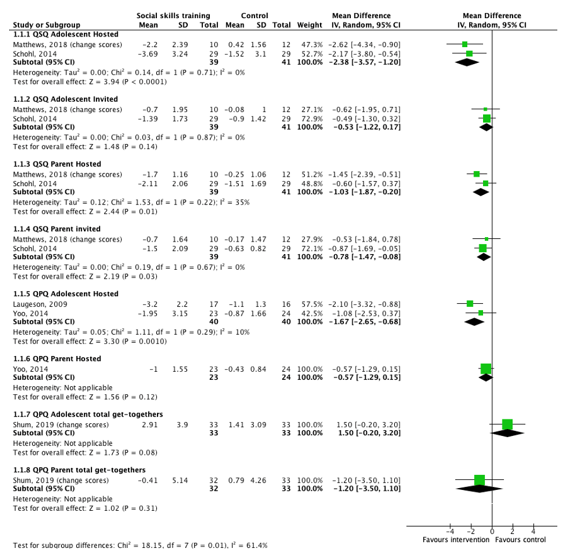

Figure 2 shows the pooled data per assessment measure and subscale. For the means of this guideline, raw scores as presented in the figure were transformed (+/-). All mean differences are in favor of the intervention, except one regarding QPQ Adolescent total get-togethers which is in favor of the control group.

Table 3. Results on the frequency of hosted and invited get-togethers

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

QPQ parent total get-togethers*

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

Figure 2. The effect of social skills training on the frequency of hosted and invited get-togethers in children and adolescents with ASD (postintervention)

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

5. Social skills

Nine studies included by Gilmore (2022) reported on social skills, assessed by using either the social parent and social teacher subscales of the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System to measure everyday skills related to social functioning (ABAS-II) (Choque-Olsson, 2017; Jonsson, 2019; Corbett, 2016; Shum, 2019) or the social parent, teacher and adolescent subscales of the Social Skills Rating Scales (SSRS)/the Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scales (SSIS-RS) (Schohl, 2014; Laugeson, 2009; Matthews, 2018; Rabin, 2021; Vernon, 2018). In addition, two other studies reported on social skills, assessed by the Autism Social Skills Profile (ASSP) (Ashori, 2019) and the SSRS (Dekker, 2019). For all scales, higher scores indicate better social skills. Choque-Olsson (2017), Jonsson (2019) and Shum (2019) provided change data from baseline to postintervention.

Data of Corbett (2016) was not pooled because they provided estimated marginal means. The authors reported an estimated marginal mean (SD) of 4.61 (2.22) for the intervention group (n=17) and 2.88 (2.27) for the control group (n=16).

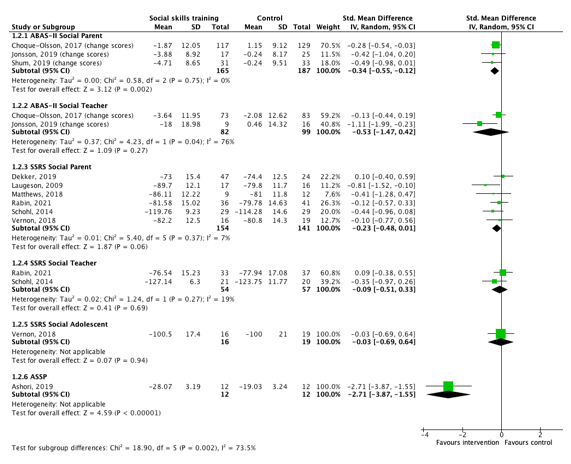

Figure 3 shows the pooled data per assessment measure and subscale. For the means of this guideline, raw scores as presented in the figure were transformed (+/-). All standardized mean differences (SMD) are in favor of the social skills intervention. Two SMD of -0.53 (95%CI -1.47 to 0.42) for the ABAS-II Social Teacher subscale and -2.71 (95%CI -3.87 to -1.55) for the ASSP were considered clinically relevant. The others were considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 3. The effect of social skills training on social skills in children and adolescents with ASD (postintervention)

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

6. Quality of life, 7. Patient satisfaction

None of the studies reported on the outcome measures quality of life and patient satisfaction.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Social performance

The level of evidence regarding social performance was downgraded by three levels to very low because the unblinded nature of all studies (risk of bias: -1), conflicting results (inconsistency: -1), and the confidence interval is crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

2. Interaction

The level of evidence regarding interaction was downgraded by three levels to very low because the unblinded nature of all studies (risk of bias: -1), the low number of included patients and the wide confidence intervals of individual studies (imprecision: -2).

3. Quality of friendships

The level of evidence regarding quality of friendships was downgraded by three levels to very low because the unblinded nature of all studies (risk of bias: -1), the confidence intervals are crossing the borders of clinical relevance and the low number of included patients (imprecision: -2).

4. Number of friends

The level of evidence regarding number of friends was downgraded by two levels to low because the unblinded nature of all studies (risk of bias: -1) and the low number of included patients (imprecision: -1).

5. Social skills

The level of evidence regarding social skills was downgraded by two levels to low because the unblinded nature of all studies (risk of bias: -1), and the confidence intervals are crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

6. Quality of life, 7. Patient satisfaction

None of the studies reported on the outcome measures quality of life and patient satisfaction and could therefore not be graded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of (add-on) social skills training compared with waitlist control, placebo attention or no add-on social skills training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)?

| P: |

Children and adolescents with ASD |

| I: |

Social skills training (stand-alone or add-on) |

| C: |

Waitlist, placebo attention, no social skills training as add-on treatment |

| O: |

Social performance, interaction, quality of friendships, number of friends, social skills, quality of life, patient satisfaction |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered social performance, interaction, and quality of friendships as critical outcome measures for decision making and social skills, number of friends, quality of life, and patient satisfaction as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (0.8 ≥ RR ≥ 1.25), and 0.5 SD (baseline) or -0.5 > SMD > 0.5 for continuous outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com), and PsycINFO were searched with relevant search terms from 2017 until 11 July 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 216 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), or randomized controlled trials (RCTs);

- Studies including twenty or more (ten per arm) participants;

- Studies with a maximum follow-up of six months;

- Studies according to the PICO; and

- Studies with English language full-text publication.

58 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 51 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and seven studies were included.

Results

Seven studies (one systematic review and six RCTs) were included in the analysis of the literature. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. Blinding of participants was not included in the risk of bias assessment performed by Gilmore (2022), but for the development of this guideline blinding was taken into consideration.

Referenties

- Ashori, M., & Jalil-Abkenar, S. S. (2019). The Effectiveness of Video Modeling on Social Skills of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 7(3), 159-166.

- Corbett BA, Ioannou S, Key AP, Coke C, Muscatello R, Vandekar S, Muse I. Treatment Effects in Social Cognition and Behavior following a Theater-based Intervention for Youth with Autism. Dev Neuropsychol. 2019 Oct;44(7):481-494. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2019.1676244. Epub 2019 Oct 7. PMID: 31589087; PMCID: PMC6818093.

- Dekker V, Nauta MH, Timmerman ME, Mulder EJ, van der Veen-Mulders L, van den Hoofdakker BJ, van Warners S, Vet LJJ, Hoekstra PJ, de Bildt A. Social skills group training in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019 Mar;28(3):415-424. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1205-1. Epub 2018 Jul 21. PMID: 30032394; PMCID: PMC6407743.

- Fuentes J, Hervás A, Howlin P; (ESCAP ASD Working Party). ESCAP practice guidance for autism: a summary of evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;30(6):961-984. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01587-4. Epub 2020 Jul 14. PMID: 32666205; PMCID: PMC8140956.

- Gilmore R, Ziviani J, Chatfield MD, Goodman S, Sakzewski L. Social skills group training in adolescents with disabilities: A systematic review. Res Dev Disabil. 2022 Jun;125:104218. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104218. Epub 2022 Mar 17. PMID: 35306461.

- Ko JA, Miller AR, Vernon TW. Social conversation skill improvements associated with the Social Tools And Rules for Teens program for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Autism. 2019 Jul;23(5):1224-1235. doi: 10.1177/1362361318808781. Epub 2018 Oct 31. PMID: 30378448.

- Luckhardt C, Kröger A, Elsuni L, Cholemkery H, Bender S, Freitag CM. Facilitation of biological motion processing by group-based autism specific social skills training. Autism Res. 2018 Oct;11(10):1376-1387. doi: 10.1002/aur.2013. Epub 2018 Oct 15. PMID: 30324710.

- Malik-Soni, N., Shaker, A., Luck, H., Mullin, A.E., Wiley, R.E., Lewis, M.E.S., Fuentes, J., & Frazier, T.W. (2022). Tackling healthcare access barriers for individuals with autism from diagnosis to adulthood. Pedriatic Research, 91, 1028-1035. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01465-y

- Shih, W., Dean, M., Kretzmann, M., Locke, J., Senturk, D., Mandell, D. S., ... & Kasari, C. (2019). Remaking recess intervention for improving peer interactions at school for children with autism spectrum disorder: Multisite randomized trial. School Psychology Review, 48(2), 133-144.

- Wang HI, Wright BD, Bursnall M, Cooper C, Kingsley E, Le Couteur A, Teare D, Biggs K, McKendrick K, de la Cuesta GG, Chater T, Barr A, Solaiman K, Packham A, Marshall D, Varley D, Nekooi R, Gilbody S, Parrott S. Cost-utility analysis of LEGO based therapy for school children and young people with autism spectrum disorder: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022 Jan 17;12(1):e056347. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056347. PMID: 35039300; PMCID: PMC8765033.

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Choueiri R, Kasari C, Carter A, Granpeesheh D, Mailloux Z, Smith Roley S, Wagner S, Fein D, Pierce K, Buie T, Davis PA, Newschaffer C, Robins D, Wetherby A, Stone WL, Yirmiya N, Estes A, Hansen RL, McPartland JC, Natowicz MR. Early Intervention for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Under 3 Years of Age: Recommendations for Practice and Research. Pediatrics. 2015 Oct;136 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S60-81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3667E. PMID: 26430170; PMCID: PMC9923898.

Evidence tabellen

Risk of bias tables

|

Study reference |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? |

Was the allocation adequately concealed? |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented? Were patients , healthcare providers, data collectors, outcome assessors, data analysts blinded? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent? |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting? |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias? |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure |

|

Ashori, 2019 |

Probably yes

Reason: Random sampling method was used. |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: Blinding was not performed. |

No information |

Probably no

Reason: No study protocol available or mentioned. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

HIGH |

|

Corbett, 2019 |

Probably yes

Reason: Simple randomization by a non-affiliated statistician |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: Open-label trial. Blinding was not performed. |

Probably no

Reason: Data were missing for multiple outcome measures resulting in 4-5% missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02276534). Outcomes are reported as prespecified in protocol. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

HIGH |

|

Dekker, 2019 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Computer generated randomization was used. Randomization was done in a 2:2:1 ratio with block size five. |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: Blinding was not performed. |

Probably no

Reason: All data was missing for 4% of participants in intervention group, and for 8% of participants in the control group. Data on questionnaire was missing for 2-8% participants. |

Probably yes

Reason: Study is registered (NTR2405), but protocol is not available. But no reason to doubt that the study is free of selective outcome reporting. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

HIGH |

|

Ko, 2019 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Participants were randomized using a simple randomization procedure (coin flip). |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: No blinding was performed, except for the trained coders (coding of outcome measures). |

Definitely no

Reason: 4/20 participants discontinued in the treatment group, and 1/20 participants discontinued in the control group. |

Probably no

Reason: No registration known; nothing is mentioned about a protocol. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

HIGH |

|

Luckhardt, 2018 |

Definitely yes

Reason: An internet-based randomization system was used (1:1 ratio). |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: No blinding was performed, except for the teachers who rated the secondary outcome measures. |

Probably no

Reason: No participants were lost to follow-up in the intervention group, but three participants (17%) were lost to follow-up in the control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Trial is registered (ISRCTN94863788). Outcome was reported as prespecified in protocol. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

HIGH |

|

Shih, 2018 |

Probably no

Reason: Random selection distributed participants to the immediate treatment group or to the control group. |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: No blinding was performed, except for the rating observers. |

Definitely no

Reason: 20% of participants were lost to follow-up in both groups. |

Probably no

Reason: No registration known; nothing is mentioned about a protocol. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted. |

HIGH |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Afsharnejad B, Falkmer M, Black MH, Alach T, Lenhard F, Fridell A, Coco C, Milne K, Chen NTM, Bölte S, Girdler S. Cross-Cultural Adaptation to Australia of the KONTAKT© Social Skills Group Training Program for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Feasibility Study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020 Dec;50(12):4297-4316. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04477-5. PMID: 32270385. |

n < 10 participants per arm |

|

Afsharnejad B, Falkmer M, Black MH, Alach T, Lenhard F, Fridell A, Coco C, Milne K, Bölte S, Girdler S. KONTAKT® social skills group training for Australian adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022 Nov;31(11):1695-1713. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01814-6. Epub 2021 May 30. PMID: 34052908. |

Comparison is not conform the PICO of this module (interactive cooking programme) |

|

Babb, S., Raulston, T. J., McNaughton, D., Lee, J.-Y., & Weintraub, R. (2021). The Effects of Social Skill Interventions for Adolescents With Autism: A Meta-Analysis. Remedial and Special Education, 42(5), 343-357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932520956362 |

Included studies with a single-case design only |

|

Beaumont R, Walker H, Weiss J, Sofronoff K. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Video Gaming-Based Social Skills Program for Children on the Autism Spectrum. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021 Oct;51(10):3637-3650. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04801-z. Epub 2021 Jan 3. PMID: 33389304; PMCID: PMC7778851. |

Comparison is not conform the PICO of this module (social skills program Secret Agent Society versus cognitive skills training game) |

|

Brady R, Maccarrone A, Holloway J, Gunning C, Pacia C. Exploring Interventions Used to Teach Friendship Skills to Children and Adolescents with High-Functioning Autism: a Systematic Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020 Jan 04;7:295-305. |

Includes no suitable RCTs according to selection criteria (n < 10 per arm; non-randomized studies) |

|

Chancel R, Miot S, Dellapiazza F, Baghdadli A. Group-based educational interventions in adolescents and young adults with ASD without ID: a systematic review focusing on the transition to adulthood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022 Jul;31(7):1-21. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01609-1. Epub 2020 Sep 5. PMID: 32889578. |

Describing results; overview of the literature |

|

Choque Olsson N, Flygare O, Coco C, Görling A, Råde A, Chen Q, Lindstedt K, Berggren S, Serlachius E, Jonsson U, Tammimies K, Kjellin L, Bölte S. Social Skills Training for Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Jul;56(7):585-592. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.001. Epub 2017 May 10. PMID: 28647010. |

Included in Gilmore (2022) |

|

Chung K, Chung E. Randomized controlled pilot study of an app-based intervention for improving social skills, face perception, and eye gaze among youth with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2023 Apr 27;14:1126290. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1126290. PMID: 37181907; PMCID: PMC10173303. |

Intervention is not conform the PICO of this module (individual SST instead of group) |

|

Dean M, Williams J, Orlich F, Kasari C. Adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and social skills groups at school: A randomized trial comparing intervention environment and peer composition. School Psych Rev. 2020;49(1):60-73. doi: 10.1080/2372966x.2020.1716636. Epub 2020 Mar 30. PMID: 33041430; PMCID: PMC7540922. |

Wrong comparison (SKILLS versus ENGAGE; two different models of school-based group social intervention) |

|

Dean M, Chang YC. A systematic review of school-based social skills interventions and observed social outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder in inclusive settings. Autism. 2021 Oct;25(7):1828-1843. doi: 10.1177/13623613211012886. Epub 2021 Jul 7. PMID: 34231405. |

Describing results; overview of the literature |

|

Dekker V, Nauta MH, Timmerman ME, Mulder EJ, Hoekstra PJ, de Bildt A. Application of Latent Class Analysis to Identify Subgroups of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders who Benefit from Social Skills Training. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021 Jun;51(6):2004-2018. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04678-y. PMID: 32892235; PMCID: PMC8124042. |

Subgroup analysis of Dekker (2019), with subgroups based on social-communicative skills before and response patterns to training |

|

Drüsedau LL, Götz A, Kleine Büning L, Conzelmann A, Renner TJ, Barth GM. Tübinger Training for Autism Spectrum Disorders (TüTASS): a structured group intervention on self-perception and social skills of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2023 Oct;273(7):1599-1613. doi: 10.1007/s00406-022-01537-y. Epub 2023 Jan 11. PMID: 36629941; PMCID: PMC10465396. |

Non-randomized design |

|

Justin D. Garwood & Christopher L. Van Loan (2019) Using Social Stories with Students with Social, Emotional, And Behavioral Disabilities: The Promise and the Perils, Exceptionality, 27:2, 133-148, DOI: 10.1080/09362835.2017.1409118 |

Literature review (non-systematic) |

|

Gates JA, Kang E, Lerner MD. Efficacy of group social skills interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017 Mar;52:164-181. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.006. Epub 2017 Jan 18. PMID: 28130983; PMCID: PMC5358101. |

Less recent and complete compared to Gilmore (2022) |

|

Gengoux GW, Schwartzman JM, Millan ME, Schuck RK, Ruiz AA, Weng Y, Long J, Hardan AY. Enhancing Social Initiations Using Naturalistic Behavioral Intervention: Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial for Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021 Oct;51(10):3547-3563. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04787-8. Epub 2021 Jan 2. PMID: 33387236. |

Population is not conform the PICO of this module (typically developing peers are included and compared) |

|

Gunning, C., Holloway, J., Fee, B. et al. A Systematic Review of Generalization and Maintenance Outcomes of Social Skills Intervention for Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 6, 172–199 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00162-1 |

Outcomes are not conform the PICO of this module (generalization and maintenance outcomes) |

|

Hong ER, Neely L, Gerow S, Gann C. The effect of caregiver-delivered social-communication interventions on skill generalization and maintenance in ASD. Res Dev Disabil. 2018 Mar;74:57-71. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.01.006. Epub 2018 Jan 20. PMID: 29360047. |

Outcomes are not conform the PICO of this module (generalization and maintenance outcomes) |

|

Ibrahim K. Neural effects of a cognitive-behavioral social skills treatment on gaze processing in children with autism spectrum disorder. 2016. |

Comparison is not conform the PICO of this module (CBT versus facilitated play) |

|

Jonsson U, Olsson NC, Coco C, Görling A, Flygare O, Råde A, Chen Q, Berggren S, Tammimies K, Bölte S. Long-term social skills group training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019 Feb;28(2):189-201. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1161-9. Epub 2018 May 10. PMID: 29748736; PMCID: PMC6510850. |

Included in Gilmore (2022) |

|

Kamps, Debra M. et al. “Peer Mediation Interventions to Improve Social and Communication Skills for Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” (2017). |

Wrong publication type (handbook) |

|

Ke, F., Whalon, K., & Yun, J. (2018). Social Skill Interventions for Youth and Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Review of Educational Research, 88(1), 3-42. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317740334 |

Very describing results; no risk of bias assessment |

|

Lee JH, Lee TS, Yoo SY, Lee SW, Jang JH, Choi YJ. Metaverse-based social skills training programme for children with autism spectrum disorder to improve social interaction ability: an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled pilot trial. The Lancet. 2023 July;61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102072 |

n < 10 participants per arm |

|

Leifler E, Coco C, Fridell A, Borg A, Bölte S. Social Skills Group Training for Students with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities in Senior High School-A Qualitative Multi-Perspective Study of Social Validity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 28;19(3):1487. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031487. PMID: 35162512; PMCID: PMC8835167. |

Non-randomized design, n < 10 participants per arm |

|

Leung PWS, Li SX, Tsang CSO, Chow BLC, Wong WCW. Effectiveness of Using Mobile Technology to Improve Cognitive and Social Skills Among Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Ment Health. 2021 Sep 28;8(9):e20892. doi: 10.2196/20892. PMID: 34581681; PMCID: PMC8512196. |

Includes no relevant RCTs according to PICO |

|

Li, D., Choque-Olsson, N., Jiao, H. et al. The influence of common polygenic risk and gene sets on social skills group training response in autism spectrum disorder. npj Genom. Med. 5, 45 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-020-00152-x |

Wrong aim (to analyze the effect of polygenic risk score and common variants in gene sets on the intervention outcome) |

|

Lopata C, Donnelly JP, Rodgers JD, Thomeer ML. Systematic review of data analyses and reporting in group-based social skills intervention RCTs for youth with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. March 2019;59:10-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.11.008 |

Wrong aim (to assess the extent to which the study planning, data assessment, and data analytic procedures used in the RCTs included in Gates (2017) adhered to established standards for RCTs) |

|

Lopata C, Thomeer ML, Rodgers JD, Donnelly JP, McDonald CA, Volker MA, Smith TH, Wang H. Cluster Randomized Trial of a School Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019 Nov-Dec;48(6):922-933. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1520121. Epub 2018 Oct 30. PMID: 30376652. |

Comparison is not conform the PICO of this module (schoolMAX vs SAU), follow-up > 6 months |

|

March-Miguez, Inmaculada and Maria-Inmaculada Fernández-Andrés. “INTERVENTION IN SOCIAL SKILLS OF CHILDREN WITH AUTISTIC SPECTRUM DISORDER: A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REVIEW.” (2018). |

Wrong publication type (bibliographical review) |

|

Matthews NL, Orr BC, Warriner K, DeCarlo M, Sorensen M, Laflin J, Smith CJ. Exploring the Effectiveness of a Peer-Mediated Model of the PEERS Curriculum: A Pilot Randomized Control Trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018 Jul;48(7):2458-2475. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3504-2. Erratum in: J Autism Dev Disord. 2018 Mar 19;: PMID: 29453708. |

Included in Gilmore (2022) |

|

McKeithan, G. K., & Sabornie, E. J. (2020). Social–Behavioral Interventions for Secondary-Level Students With High-Functioning Autism in Public School Settings: A Meta-Analysis. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 35(3), 165-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357619890312 |

Included studies with a single-case design only |

|

McVey AJ, Schiltz H, Haendel A, Dolan BK, Willar KS, Pleiss S, Karst JS, Carson AM, Caiozzo C, Vogt E, Van Hecke AV. Brief Report: Does Gender Matter in Intervention for ASD? Examining the Impact of the PEERS® Social Skills Intervention on Social Behavior Among Females with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017 Jul;47(7):2282-2289. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3121-5. PMID: 28391452; PMCID: PMC6419962. |

Reports no absolute values and dispersion measures (only group differences) |

|

Menezes M, Harkins C, Robinson MF, Mazurek MO. Treatment of Depression in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. October 2020;78:101639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101639 |

Outcomes are not conform the PICO of this module (depression symptoms) |

|

Mirzaei SS, Pakdaman S, Alizadeh E, Pouretemad H. A systematic review of program circumstances in training social skills to adolescents with high-functioning autism. Int J Dev Disabil. 2020 Jun 1;68(3):237-246. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2020.1748802. PMID: 35603001; PMCID: PMC9122374. |

No comparison; describing results (correlations) |

|

Płatos M, Wojaczek K, Laugeson EA. Effects of Social Skills Training for Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum: a Randomized Controlled Trial of the Polish Adaptation of the PEERS® Intervention via Hybrid and In-Person Delivery. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023 Nov;53(11):4132-4146. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05714-9. Epub 2022 Aug 24. PMID: 36001196; PMCID: PMC9399988. |

Follow-up > 6 months |

|

Pulido-Banner MA. EFFECTIVENESS OF SOCIAL SKILLS TRAINING FOR ADOLESCENTS WITH AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER. 2017 |

n < 10 participants per arm |

|

Radley, K.C., Dart, E.H., Brennan, K.J. et al. Social Skills Teaching for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Review. Adv Neurodev Disord 4, 215–226 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-020-00170-x |

Included studies with a single-case design only |

|

Rumney, H. L., & MacMahon, K. (2017). Do social skills interventions positively influence mood in children and young people with autism? A systematic review. Mental Health and Prevention, 5, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2016.12.001 |

Outcomes are not conform the PICO of this module (measures of depression and/or anxiety) |

|

Safer-Lichtenstein J, Hamilton JC, McIntyre LL. Examining Demographics in Randomized Controlled Trials of Group-Based Social Skills Interventions for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019 Aug;49(8):3453-3461. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04063-4. PMID: 31119512. |

Wrong aim (to review the demographic reporting practices and diversity of participants in published RCTs of GSSIs for individuals with ASD) |

|

Schiltz HK, McVey AJ, Dolan BK, Willar KS, Pleiss S, Karst JS, Carson AM, Caiozzo C, Vogt EM, Yund BD, Van Hecke AV. Changes in Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents with ASD Completing the PEERS® Social Skills Intervention. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018 Mar;48(3):834-843. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3396-6. PMID: 29164445; PMCID: PMC10321229. |

Substudy of Schohl (2014) which is included in Gilmore (2022) |

|

Shum KK, Cho WK, Lam LMO, Laugeson EA, Wong WS, Law LSK. Learning How to Make Friends for Chinese Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Hong Kong Chinese Version of the PEERS® Intervention. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019 Feb;49(2):527-541. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3728-1. PMID: 30143950. |

Included in Gilmore (2022) |

|

Soares EE, Bausback K, Beard CL, Higinbotham M, Bunge EL, Gengoux GW. Social Skills Training for Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Meta-analysis of In-person and Technological Interventions. J Technol Behav Sci. 2021;6(1):166-180. doi: 10.1007/s41347-020-00177-0. Epub 2020 Nov 17. PMID: 33225056; PMCID: PMC7670840. |

Outcome reporting unfavorable; no group means and SD but only hedge’s g and 95%CI |

|

Syriopoulou-Delli CK, Gkiolnta E. Review of assistive technology in the training of children with autism spectrum disorders. Int J Dev Disabil. 2020 Jan 20;68(2):73-85. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2019.1706333. PMID: 35309695; PMCID: PMC8928843. |

Literature review (non-systematic) |

|

Christine K. Syriopoulou-Delli & Kyriaki Sarri (2023) Vocational rehabilitation of adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: a review, International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, DOI: 10.1080/20473869.2023.2208898 |

Includes no relevant RCTs according to PICO |

|

Tawankanjanachot, N., Melville, C., Habib, A., Truesdale, M., & Kidd, L. (2023). Systematic review of the effectiveness and cultural adaptation of social skills interventions for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders in Asia. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 104, Article 102163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2023.102163 |

Relevant studies are included in Gillmore (2022) which is more recent |

|

Tseng A, Biagianti B, Francis SM, Conelea CA, Jacob S. Social Cognitive Interventions for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Affect Disord. 2020 Sep 1;274:199-204. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.134. Epub 2020 May 25. PMID: 32469804; PMCID: PMC7430499. |

Describing results; current state of knowledge. No data presented. |

|

van Pelt BJ, Idris S, Jagersma G, Duvekot J, Maras A, van der Ende J, van Haren NEM, Greaves-Lord K. The ACCEPT-study: design of an RCT with an active treatment control condition to study the effectiveness of the Dutch version of PEERS® for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Jun 1;20(1):274. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02650-9. PMID: 32487179; PMCID: PMC7268391. |

Wrong publication type (study protocol) |

|

Wang HI, Wright BD, Bursnall M, Cooper C, Kingsley E, Le Couteur A, Teare D, Biggs K, McKendrick K, de la Cuesta GG, Chater T, Barr A, Solaiman K, Packham A, Marshall D, Varley D, Nekooi R, Gilbody S, Parrott S. Cost-utility analysis of LEGO based therapy for school children and young people with autism spectrum disorder: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022 Jan 17;12(1):e056347. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056347. PMID: 35039300; PMCID: PMC8765033. |

Outcomes are not conform the PICO of this module (cost-utility analysis) |

|

Watkins L, Ledbetter-Cho K, O'Reilly M, Barnard-Brak L, Garcia-Grau P. Interventions for students with autism in inclusive settings: A best-evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2019 May;145(5):490-507. doi: 10.1037/bul0000190. Epub 2019 Mar 14. PMID: 30869925. |

Wrong publication type (best evidence synthesis) |

|

Wichers RH, van der Wouw LC, Brouwer ME, Lok A, Bockting CLH. Psychotherapy for co-occurring symptoms of depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2023 Jan;53(1):17-33. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722003415. Epub 2022 Nov 21. PMID: 36404645. |

Outcomes are not conform the PICO of this module (measures of depression and/or anxiety) |

|

Wolstencroft J, Robinson L, Srinivasan R, Kerry E, Mandy W, Skuse D. A Systematic Review of Group Social Skills Interventions, and Meta-analysis of Outcomes, for Children with High Functioning ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018 Jul;48(7):2293-2307. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3485-1. PMID: 29423608; PMCID: PMC5996019. |

Less recent/outcomes of interest compared to Gilmore (2022) |

|

Zhang B, Liang S, Chen J, Chen L, Chen W, Tu S, Hu L, Jin H, Chu L. Effectiveness of peer-mediated intervention on social skills for children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Pediatr. 2022 May;11(5):663-675. doi: 10.21037/tp-22-110. PMID: 35685075; PMCID: PMC9173870. |

Comparator is not conform the PICO of this module (ABA-based early behavioral intervention) |

|

Zheng, Shuting et al. “Improving Social Knowledge and Skills among Adolescents with Autism: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of UCLA PEERS® for Adolescents.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 51 (2021): 4488 - 4503. |

Outcome reporting unfavorable; no group means and SD but only hedge’s g and 95%CI |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 27-05-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 19-05-2025

De Nederlandse Vereniging voor Autisme autoriseert de richtlijn maar niet de module ‘Vroege interventies’ omdat zij zich niet kan vinden in de inhoud.

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen en jeugd met autismespectrumstoornissen. Alle werkgroepleden hebben deelgenomen aan de werkgroep om het perspectief van de vereniging te vertegenwoordigen.

Werkgroep

- Mevr. dr. Anna van der Miesen, arts-onderzoeker, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, NVvP

- Mevr. dr. Annelies de Bildt, psycholoog, Accare, Groningen, NIP

- Mevr. Claudette Nouris, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Landelijke Oudervereniging Balans

- Mevr. dr. Els Blijd-Hoogewys, klinisch psycholoog, Psychiatrie Noord, Groningen, NIP

- Mevr. dr. Fleur Velders, kinder- en jeugdpsychiater, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, Utrecht, NVvP

- Mevr. drs. Gemma Witteman, jeugdarts, Karakter kinder- en jeugdpsychiatrie, Enschede, AJN jeugdartsen

- Mevr. dr. Janneke Zinkstok, kinder- en jeugdpsychiater, Radboud Universitair Medisch Centrum, Nijmegen, NVvP

- Dhr. Jasper Wagteveld, ervaringsdeskundige, NVA

- Mevr. dr. Jopje Ruskamp, kinderarts, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, Utrecht, NVK

- Dhr. drs. Jos Boer, verpleegkundig specialist, Dimence Groep, Deventer, V&VN

- Dhr. dr. Mathieu Pater, muziektherapeut, Muziek en Therapie, Vaktherapie Nederland

- Dhr. dr. Richard Vuijk, klinisch psycholoog - psychotherapeut, SARR Autisme Rotterdam – onderdeel van Antes Parnassia Groep, Rotterdam, NIP

- Mevr. dr. Wietske Ester, kinder- en jeugdpsychiater, Curium Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden en Sarr Autisme Rotterdam-Youz Kinder- en jeugdpsychiatrie, Rotterdam NVvP

- Dhr. prof. dr. Wouter Staal, kinder- en jeugdpsychiater, Radboud Universitair Medisch Centrum, Nijmegen, NVvP

Klankbordgroep

- Mevr. prof. dr. Maretha de Jonge, orthopedagoog-generalist, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, Utrecht, NVO

- Mevr. prof. dr. Tjitske Kleefstra, klinisch geneticus, Radboud Universitair Medisch Centrum, Nijmegen, VKGN

Met ondersteuning van

- Mevr. drs. Beatrix Vogelaar, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mevr. drs. Laura van Wijngaarden, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dhr. drs. Toon Lamberts, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. dr. Anna van der Miesen |

02-2023--04-2024: CAMH, Toronto, Canada: post-doc onderzoeker 02-2023-heden: Amsterdam UMC, lokatie VUmc, post-doc onderzoeker 04-2024-heden: GGZ inGeest, arts-assistent in opleiding tot psychiater |

* Archives of Sexual Behavior, International Journal of Transgender Health: editorial board member (onbetaald). * Faculty of General Education Initiative (GEI), World Professional Association for Transgender Health (betaald). * Scientific Committee, European Professional Association for Transgender Health (onbetaald). * Lid kerngroep Female Autism Network of the Netherlands (onbetaald).

|

* Robert Wood Johnson Foundation - Investigating Portable Components of the Netherlands Gender Affirming Care Policy to Improve Transgender Youth Health Outcomes in the United States (projectleider). * KNAW Ter Meulen beurs - Gender Diversity in a Prospective Clinical Youth Cohort: Prevalence Rates and Associations with Suicidality, Self-Harm, Mental Health Risks, and Protective Factors (projectleider). * Womenmind 2022 Postdoctoral Fellowship Competition - Sex Assigned at Birth, Gender Identity, and Gender Identity Diversity Differences in a Prospective Clinical Youth Cohort: Prevalence Rates and Associations with Suicidality, Self-Harm, Mental Health Risks, and Protective Factors (projectleider). * Discovery Fund 2022 Postdoctoral Fellowship – Declined. * Agis Innovatiefonds - Buitengewoon jezelf (geen projectleider).

* Arcus Foundation: Transgender Youth Outcomes Initiative: Understanding the Impacts of Trans Youth US State-BasedPolicies to Drive Policy and Public Perception Change (projectleider) * Womenmind 2023 Seed Funding Competition:An Intersectional Lens to Youth Wellness Hubs Ontario: Learning with Girls/Women and Gender Diverse Youth (geen projectleider) * Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Seksualiteit:Beyond Gender-Related Medical Care: The influence of Policies, Practices, and Contextual factors on Transgender Adolescent’s Mental Health and Wellbeing (projectleider) * General Research Fund Hong Kong University:Both sides now: Expressed and perceived gender (non)conformity and psychosocial wellbeing in Chinese community children (projectleider) womenmind 2024 Seed Funding Competition: Creating a * Community-Developed Self-Advocacy Tool for Autistic Gender-Diverse Adolescents for the Promotion of Wellbeing (geen projectleider) * Canadian Institutes of Health Research: Strengthening Youth Wellness Hubs Ontario's Learning Health System through Enhancing Measurement Based Care, Data Integration and Equity-focused Practices (geen projectleider)

Alle subsidies zijn charitatief (geen sponsoring door de industrie). |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mevr. dr. Annelies de Bildt |

Psycholoog, Accare, Groningen. |

Stuurgroepvoorzitter ADOS en ADI-R

|

* ZonMw (08450012220002) Verbeteren van diagnostiek bij mensen met een matige of ernstige verstandelijke beperking (projectleider). * Auteur NL bewerking ADI-R en ADOS * ADOS en ADI-R trainer * Redacteur van een boek over autisme bij kinderen, uitgegeven in 2021, bij BSL. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mevr. Claudette Nouris |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Landelijke Oudervereniging Balans |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mevr. dr. Els Blijd-Hoogewys |

Behandel Inhoudelijk Manager, Klinisch psycholoog en senior onderzoeker bij INTER-PSY (full-time)

Per 1 januari 2025 psycholoog bij Psychiatrie Noord. |

Mede-oprichter en voorzitter FANN (Female Autism Network of the Netherlands), onbetaald Voorzitter CASS18+ (consortium voor BIG geregistreerde behandelaars van volwassenen met autisme), onbetaald Lid Autisme Jonge Kind, landelijk expertise netwerk, onbetaald Lid Alliantie Gender & GGZ, namens NIP, onbetaald Organisator Nationaal Autisme Congres, deelname in winst/verlies Diverse lezingen over autisme, betaald |

Boeken over autisme geschreven of de redactie daarvan gedaan:

Mede-aanvrager van een onderzoek NWO, Breaking the cycle: an inclusive school environment outside the classroom for adolescents with ASD (geen projectleider). |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mevr. dr. Fleur Velders |

Kinder- en jeugdpsychiater, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, Utrecht |

Nederlands Jeugd Instituut; commissielid erkenningscommissie jeugdinterventies (vacatiegelden) |

* Zorginstituut Nederland, Samen beslissen in de praktijk met kinderen, gericht op kinderen met psychische klachten (geen projectleider). |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mevr. drs. Gemma Witteman |

Jeugdarts, Karakter kinder- en jeugdpsychiatrie, Enschede

Werkzaamheden diagnostiek en behandeling van kinderen met ASS |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mevr. dr. Janneke Zinkstok |

Kinder- en jeugdpsychiater, Radboud Universitair Medisch Centrum, Nijmegen |

* Redactie Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie (onbetaald, maar vacatiegelden) * Ethics committee internatinal society psycho genetics |

* ZonMW, COFIT-PSY project: Gevolgen van COVID-19-maatregelen voor mensen met psychiatrische aandoeningen (projectleider). * Radboudumc Principal Clinician subsidie voor innovatie project om ouders van kinderen met aangeboren ontwikkelingsstoornissen te ondersteunen (projectleider). * Agis innovatiefonds subsidie voor project om ervaringsdeskundigheid te ontsluiten voor jongeren met autism en licht verstandelijke beperking (projectleider). * ZonMW middellang - Een verloren generatie? Effecten van de COVID-19 pandemie op de mentale gezondheid van jongeren (geen projectleider)

|

Geen restricties. |

|

Dhr. Jasper Wagteveld |

Ervaringsdeskundig adviseur, Dokter Bosman |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mevr. dr. Jopje Ruskamp |

Kinderarts, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, Utrecht |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Dhr. drs. Jos Boer |

Verpleegkundig specialist, Dimence Groep, Deventer

Per januari 2023 bij het Specialistisch Centrum Ontwikkelingsstoornissen (SCOS). |

Promovendus Brain Division UMC Utrecht |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Dhr. dr. Mathieu Pater |

Muziektherapeut, ZZP. |

Geen. |

Geen. |

Geen restricties. |

|

Dhr. dr. Richard Vuijk |

Klinisch psycholoog - psychotherapeut, SARR Autisme Rotterdam – onderdeel van Antes Parnassia Groep, Rotterdam, NIP |

Eigen praktijk voor scholing AutismeSpectrumNederland. |

Auteur: Werkwijzer - Psychodiagnostiek autismespectrumstoornis volwassenen (2018) en Nederlands Interview voor Diagnostiek Autismespectrumstoornis bij volwassenen (NIDA) – Handleiding en Interview |

Geen restricties. |

|

Mevr. dr. Wietske Ester |

Kinder- en jeugdpsychiater, Youz Kinder- en jeugdpsychiatrie, SARR Autisme, Rotterdam. Associate Professor, kinder- en jeugdpasychiater, Curium-LUMC, Leiden. |

Geen. |