Antitrombotische beleid ter preventie van herseninfarct

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het optimale antitrombotisch beleid voor patiënten met atriumfibrilleren (met uitzondering van patiënten met mechanische hartkleppen of matige tot ernstige mitralisstenose)?

Deze uitgangsvraag bevat de volgende deelvragen:

- Bij welke patiënten met atriumfibrilleren zijn orale anticoagulantia geïndiceerd?

- Hoe dienen patiënten met atriumfibrilleren vervolgd te worden?

- Met welke anticoagulantia moeten patiënten met atriumfibrilleren behandeld worden?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik het klinisch patroon van atriumfibrilleren (dat wil zeggen, nieuw gediagnosticeerd, paroxysmaal, persistent, langdurig persistent, permanent) niet voor de indicatiestelling voor antitrombotische behandeling.

Gebruik een op risicofactoren gebaseerde benadering zoals de CHA2DS2-VASc-score (tabel 1):

- Geef geen antitrombotische behandeling ter preventie van herseninfarct bij AF-patiënten met een CHA2DS2-VASc-score van 0 bij mannen of 1 bij vrouwen (NB. Voor behandeling bij katheterablaties en cardioversie wordt verwezen naar de module 6.3).

- Overweeg orale anticoagulantia ter preventie van herseninfarct bij AF-patiënten met een CHA2DS2-VASc-score van 1 bij mannen of 2 bij vrouwen.

- Geef orale anticoagulantia voor de preventie van herseninfarct bij AF-patiënten met een CHA2DS2-VASc-score ≥ 2 bij mannen of ≥ 3 bij vrouwen.

Overweeg het gebruik van een bloedingsscore, zoals de HAS-BLED-score (tabel 3), met als doel modificeerbare risicofactoren voor bloeding te identificeren en te behandelen (tabel 2) en om die patiënten te identificeren met een hoger risico op bloedingen (bijvoorbeeld HAS-BLED-score ≥ 3) die ingepland moeten worden voor vroege en frequentere klinische beoordeling en follow-up.

Beschouw een (hoog) geschat bloedingsrisico niet als een absolute contra-indicatie* voor orale anticoagulantia.

(Her)beoordeel het risico op herseninfarct en bloedingen periodiek om de indicatie voor orale anticoagulantia te sturen (bijvoorbeeld, starten van orale anticoagulantia bij patiënten die niet langer een laag risico op een herseninfarct hebben) en mogelijk modificeerbare risicofactoren voor bloedingen aan te pakken. De werkgroep adviseert ten minste jaarlijks aan te houden.

Overweeg bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren die aanvankelijk een laag risico op een CVA hebben, de eerste herbeoordeling van het risico op CVA na 4 tot 6 maanden na diagnose.

Gebruik een DOAC (in plaats van vitamine K-antagonisten) ter preventie van herseninfarct bij AF-patiënten die in aanmerking komen voor orale anticoagulantia.

- NB: zie module Atriumfibrilleren en valvulaire hartziekte voor atriumfibrilleren bij matig tot ernstige mitralisklepstenose en bij mechanische hartklepprothese.

Indien VKA gebruikt wordt:

- Gebruik een INR-streefwaarde 2,0 tot 3,0 en streef naar een TTR ≥ 70%.

- Bespreek de voordelen en nadelen van een DOAC ten opzichte van VKA (als er geen contra-indicatie voor DOAC is).

Bij patiënten met VKA en een lage TTR (bijvoorbeeld < 70%):

- Overweeg omzetting naar een DOAC, waarbij goed gelet wordt op adherentie; of

- Probeer de TTR te laten verbeteren (bijvoorbeeld educatie/voorlichting aan de patiënt over het belang van een stabiele TTR en contact leggen met de Trombosedienst).

Overwegingen

Stroke risk assessment

Overall, AF increases the risk of stroke five-fold, but this risk is not homogeneous, depending on the presence of specific stroke risk factors/ modifiers. Main clinical stroke risk factors have been identified from non-anticoagulated arms of the historical RCTs conducted >20 years ago, notwithstanding that these trials only randomized < 10% of patients screened, whereas many common risk factors were not recorded or consistently defined (Pisters, 2012). These data have been supplemented by evidence from large observational cohorts also studying patients who would not have been included in the RCTs. Subsequently, various imaging, blood, and urine biological markers (biomarkers) have been associated with stroke risk (Pisters, 2012; Szymanski, 2015). In addition, non-paroxysmal AF is associated with an increase in thrombo-embolism (multivariable adjusted HR 1.38; 95% CI 1.19 to 1.61) compared with paroxysmal AF (Ganesan, 2016). Notably, many of the risk factors for AF-related complications are also risk factors for incident AF (Allan, 2017).

Common stroke risk factors are summarized in the clinical risk-factor-based CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥ 75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke, Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category (female)) score (Table 1) (Lip, 2010).

Table 1 CHA2DS2-VASc score (source: Hindricks, 2020)

|

Risk factors and definitions |

Points awarded |

|

|

C |

Congestive heart failure Clinical HF, or objective evidence of moderate to severe LV dysfunction, or HCM. |

1 |

|

H |

Hypertension Or on antihypertensieve therapy |

1 |

|

A |

Age 75 years of older |

2 |

|

D |

Diabetes mellitus Treatment with oral hypoglaemic drugs and/or insulin of fasting blood glucose > 125 mg/dL (7 mmol/L) |

1 |

|

S |

Stroke Previous stroke, TIA, or systemic arterial thromboembolism |

2 |

|

V |

Vascular disease Angiographically significant CAD, previous myocardial infarction, PAD, or aortic plaque |

1 |

|

A |

Age 65-74 years |

1 |

|

Sc |

Sex category (female) |

1 |

|

Maximum score |

9 |

|

Stroke risk scores have to balance simplicity and practicality against precision (Killu, 2019; Rivera-Carvaca, 2017; Alkhouli, 2019). As any clinical risk-factor-based score, CHA2DS2-VASc performs only modestly in predicting high-risk patients who will sustain thrombo-embolic events, but those identified as low-risk (CHA2DS2-VASc 0 (males), or score of 1 (females)) consistently have low ischaemic stroke or mortality rates (< 1%/ year) and do not need any stroke prevention treatment.

Female sex is an age-dependent stroke risk modifier rather than a risk factor per se (Wu, 2020; Tomasdottir, 2019). Observational studies showed that women with no other risk factors (CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1) have a low stroke risk, similar to men with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 (Friberg, 2012). The simplified CHA2DS2-VA score could guide the initial decision about OAC in AF patients, but not considering the sex component would underestimate stroke risk in women with AF (Overvad, 2019; Nielsen, 2020). In the presence of >1 non-sex stroke risk factor, women with AF consistently have significantly higher stroke risk than men (Nielsen, 2018; Marzona, 2018).

Many clinical stroke risk factors (for example renal impairment, OSA, LA dilatation (Vinereanu, 2017, Atrial Fibrillation Investigators, 1998; Friberg, 2015; Poli, 2017; Bassand, 2018)) are closely related to the CHA2DS2-VASc components, and their consideration does not improve its predictive value (the relationship of smoking or obesity to stroke risk in AF is also contentious) (Overvad, 2013). Various biomarkers (for example troponin, natriuretic peptides, growth differentiation factor (GDF)-15, von Willebrand factor) have shown improved performance of biomarker-based over clinical scores in the assessment of residual stroke risk among anticoagulated AF patients (Hijazi, 2017; Lip, 2006); notwithstanding, many of these biomarkers (as well as some clinical risk factors) are predictive of both stroke and bleeding (Hijazi, 2017) or non-AF and non-cardiovascular conditions, often (non-specifically) reflecting simply a sick heart or patient.

More complex clinical scores (for example Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD - Atrial Fibrillation (GARFIELD-AF)) (Fox, 2017) and those inclusive of biomarkers (for example Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) (Zhu, 2017; Singer, 2013), Intermountain Risk Score Graves, 2018), ABC-stroke (Age, Biomarkers, Clinical history)) (Hijazi, 2016) improve stroke risk prediction modestly but statistically significantly. The ABC-stroke risk score that considers age, previous stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA), high sensitivity troponin T (cTnT-hs) and N-terminal (NT)-prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide has been validated in the cohorts of landmark DOAC-trials (Hijazi, 2017; Oldgren, 2016; Berg, 2019). A biomarker score-guided treatment strategy to reduce stroke and mortality in AF patients is being evaluated in an ongoing RCT (the ABC-AF Study, NCT03753490).

Whereas the routine use of biomarker-based risk scores currently would not substantially add to initial stroke prevention treatment decisions in patients already qualifying for treatment based on the CHA2DS2-VASc score (and a limited practicality would be accompanied by increased healthcare costs) (Rivera-Caravaca, 2017; Rivera-Caravaca, 2019; Esteve-Pastor, 2017), biomarkers could further refine stroke risk differentiation among patients initially classified as low risk and those with a single non-sex CHA2DS2-VASc risk factor (Shin, 2019).

Studies of the CHA2DS2-VASc score report a broad range of stroke rates depending on study setting (community versus hospital), methodology (for example excluding patients subsequently treated with OAC would bias stroke rates towards lower levels), ethnicity, and prevalence of specific stroke risk factors in the study population (different risk factors carry different weight, and age thresholds for initiating DOACs may even differ for patients with a different single non-sex stroke risk factor, as follows: age 35 years for HF, 50 years for hypertension or diabetes, and 55 years for vascular disease) (Chao, 2019; Nielsen, 2016). No RCT has specifically addressed the need for OAC in patients with a single non-sex CHA2DS2-VASc risk factor (to obtain high event rates and timely complete the study, anticoagulation trials have preferentially included high-risk patients), but an overview of subgroup analyses and observational data suggests that OAC use in such patients confers a positive net clinical benefit when balancing the reduction in stroke against the potential for harm with serious bleeding (Lip, 2015; Fauchier, 2016).

For many risk factors (for example age), stroke risk is a continuum rather than an artificial low-, moderate-, or high-risk category. Risk factors are dynamic and, given the elderly AF population with multiple (often changing) comorbidities, stroke risk needs to be re-evaluated at each clinical review. Recent studies have shown that patients with a change in their risk profile are more likely to sustain strokes (Chao, 2018; Yoon, 2018). Many initially low-risk patients (> 15%) would have ≥ 1 non-sex CHA2DS2-VASc risk factor at 1 year after incident AF (Chao, 2019; Potpara, 2012; Weijs, 2019), and 90% of new comorbidities were evident at 4.4 months after AF was diagnosed Chao, 2019).

A Patient-Centred Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)-commissioned systematic review of 61 studies compared diagnostic accuracy and impact on clinical decision making of available clinical and imaging tools and associated risk factors for predicting thromboembolic and bleeding risk in AF patients (Borre, 2018). The authors concluded that the CHADS2 (CHF history, Hypertension history, Age ≥ 75 y, Diabetes mellitus history, Stroke or TIA symptoms previously), CHA2DS2-VASc, and ABC risk scores have the best evidence for predicting thrombo-embolic risk (moderate strength of evidence for limited prediction ability of each score).

Bleeding risk assessment

When initiating antithrombotic therapy, potential risk for bleeding also needs to be assessed. Non-modifiable and partially modifiable bleeding risks (Table 2) are important drivers of bleeding events in synergy with modifiable factors (Chao, 2018). Notably, a history of falls is not an independent predictor of bleeding on OAC (a modelling study estimated that a patient would need to fall 295 times per year for the benefits of ischaemic stroke reduction with OAC to be outweighed by the potential for serious bleeding) (Man-Son-Hing, 1999).

Table 2 Risk factors for bleeding with OAC and antiplatelet therapy (source: Hindricks, 2020)

|

Non-modifiable |

Potentially modifiable |

Modifiable |

Biomarkers |

|

Age >65 years |

Extreme frailty ± excessive risk of fallsa |

Hypertension/elevated SBP |

GDF-15 |

|

Previous major bleeding |

Anaemia |

Concomitant antiplatelet/NSAID |

Cystatin C/CKD-EPI |

|

Severe renal impairment (on dialysis or renal transplant) |

Reduced platelet count or function |

Excessive alcohol intake |

cTnT-hs |

|

Severe hepatic dysfunction (cirrhosis) |

Renal impairment with CrCl < 60 ml/min |

Non-adherence to OAC |

von Willebrand factor (+ other coagulation markers) |

|

Malignancy |

VKA management strategyb |

Hazardous hobbies/occupations |

|

|

Genetic factors (e.g. CYP2C9 polymorphisms) |

|

Bridging therapy with heparin |

|

|

Previous stroke, small-vessel disease, etc. |

|

INR control (target 2.0-3.0), target TTR >70%c |

|

|

Diabetes mellitus |

|

Appropriate choice of OAC and correct dosingd |

|

|

Cognitive impairment/dementia |

|

|

|

CKD-EPI= Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; CrCl = creatinine clearance; cTnT-hs = high-sensitivity troponin T; CYP = cytochrome P; GDF-15 = growth differentiation factor-15; INR = international normalized ratio; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OAC = oral anticoagulant; SBP = systolic blood pressure; TTR = time in therapeutic range; VKA = vitamin K antagonist.

aWalking aids; appropriate footwear; home review to remove trip hazards; neurological assessment where appropriate

bIncreased INR monitoring, dedicated OAC clinicals, self-monitoring/self-management, education/behavioural interventions

cFor patients receiving VKA treatment

dDose adaptation based on patient’s age, body weight, and serum creatinine level

Modifiable and non-modifiable bleeding risk factors have been used to formulate various bleeding risk scores (Fox, 2017; Gage, 2006; Fang, 2011; O’Brien, 2015; Rohla, 2019; Pisters, 2010) generally with a modest predictive ability for bleeding events (Mori, 2019; Yao, 2017). Studies comparing specific bleeding risk scores provided conflicting findings (O’Brien, 2015; Rohla, 2019; Rutherford, 2018). Various biomarkers have been proposed as bleeding risk predictors, but many have been studied in anticoagulated trial cohorts (while bleeding risk assessment is needed at all parts of the patient pathway - when initially not using OAC, if taking aspirin, and, subsequently, on OAC). Additionally, biomarkers are non-specifically predictive of stroke, death, HF, et cetera (Thomas, 2017; Khan, 2019). or even non-cardiovascular conditions (for example glaucoma) (Ban, 2017), and the availability of some biomarkers is limited in routine clinical practice.

The biomarker-based ABC-bleeding risk score (Age, Biomarkers (GDF-15, cTnT-hs, haemoglobin) and Clinical history (prior bleeding)) (Berg, 2019; Hijazi, 2016) reportedly outperformed clinical scores, but in another study there was no long-term advantage of ABC-bleeding over HAS-BLED score (Table 3), whereas HAS-BLED was better in identifying patients at low risk of bleeding (HAS-BLED 0 - 2) (Esteve-Pastor, 2017). In the PCORI-commissioned systematic review (Borre, 2018), encompassing 38 studies of bleeding risk prediction, the HAS-BLED score had the best evidence for predicting bleeding risk (moderate strength of evidence), consistent with other systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing bleeding risk prediction approaches (Caldeira, 2014; Zhu, 2015; Chang, 2020).

Table 3 Clinical risk factors in the HAS-BLED score (source: Hindricks, 2020)

|

Risk factors and definitions |

Points awarded |

|

|

H |

Uncontrolled hypertension SBP >160 mmHg |

1 |

|

A |

Abnormal renal and/or hepatic function Dialysis, transplant, serum creatinine > 200 µmol/L, cirrhosis, bilirubin > 2 x upper limit of normal, AST/ALT/ALP/ > 3 x upper limit of normal |

1 point for each |

|

S |

Stroke Previous ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke |

1 |

|

B |

Bleeding history or predisposition Previous major hemorrhage or anemia or severe thrombocytopenia |

1 |

|

L |

Labile INR TTR <60% in patiënt receiving VKA |

1 |

|

E |

Elderly Aged >65 years or extreme frailty |

1 |

|

D |

Drugs or excessive alcohol drinking Concomitant use of antiplatelet or NSAID; and/or excessiveb alcohol per week |

1 point for each |

|

Maximum score |

9 |

|

ALP = alkaline phosphatase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; SBP = systolic blood pressure; INR = international normalized ratio; NSAID = Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; TTR = time in therapeutic range; VKA = vitamin K antagonist.

aHaemorrhagic stroke would also score 1 point under the ‘B’ criterion

bAlcohol excess or abuse refers to a high intake (for example > 14 units per week), where the clinician assesses there would be an impact on health or bleeding risk

A high bleeding risk score should not lead to withholding OAC, as the net clinical benefit of OAC is even greater amongst such patients. However, the formal assessment of bleeding risk informs management of patients taking OAC, focusing attention on modifiable bleeding risk factors that should be managed and (re)assessed at every patient contact, and identifying high-risk patients with non-modifiable bleeding risk factors who should be reviewed earlier (for instance in 4 weeks rather than 4 to 6 months) and more frequently (Chao, 2018; Lip, 2016). Identification of ‘high bleeding risk’ patients is also needed when determining the antithrombotic strategy in specific AF patient groups, such as those undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Overall, bleeding risk assessment based solely on modifiable bleeding risk factors is an inferior strategy compared with formal bleeding risk assessment using a bleeding risk score (Chao, 2018; Guo, 2018; Esteve-Pastor,2017), thus also considering the interaction between modifiable and non-modifiable bleeding risk factors. Bleeding risk is dynamic, and attention to the change in bleeding risk profile is a stronger predictor of major bleeding events compared with simply relying on baseline bleeding risk. In a recent study, there was a 3.5-fold higher risk of major bleeding in the first 3 months amongst patients who had a change in their bleeding risk profile (Chao, 2018).

In the mAFA-II trial, prospective dynamic monitoring and reassessment using the HAS-BLED score (together with holistic App-based management) was associated with fewer major bleeding events, mitigated modifiable bleeding risk factors, and increased OAC uptake; in contrast, bleeding rates were higher and OAC use overall decreased by 25% in the ‘usual care’ arm when comparing baseline with 12 months (Guo, 2020).

Absolute contraindications to oral anticoagulants

The few absolute contraindications to OAC include active serious bleeding (where the source should be identified and treated), associated comorbidities (for example severe thrombocytopenia < 50 platelets/µL, severe anaemia under investigation, et cetera), or a recent high-risk bleeding event such as intracranial haemorrhage (ICH). Non-drug options may be considered in such cases (module 8.3).

Stroke prevention therapies

Vitamin K antagonists

Compared with control or placebo, vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy (mostly warfarin) reduces stroke risk by 64% and mortality by 26% (Hart, 2007), and is still used in many AF patients worldwide. VKAs are currently the only treatment with established safety in AF patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease and/or an artificial heart valve.

The use of VKAs is limited by the narrow therapeutic interval, necessitating frequent international normalized ratio (INR)monitoring and dose adjustments (De Caterina, 2013). At adequate time in therapeutic range ((TTR) > 70%), VKAs are effective and relatively safe drugs. Quality of VKA management (quantified using the TTR based on the Rosendaal method, or the percentage of INRs in range) correlates with haemorrhagic and thrombo-embolic rates (Wan, 2008). At high TTR values, the efficacy of VKAs in stroke prevention may be similar to DOACs, whereas the relative safety benefit with DOACs is less affected by TTR, with consistently lower serious bleeding rates (for example ICH) seen with DOACs compared with warfarin, notwithstanding that the absolute difference is small (Sjalander, 2018; Amin, 2014).

Numerous factors (including genetics, concomitant drugs, et cetera) influence the intensity of VKA anticoagulant effect; the more common ones have been used to derive and validate the SAMe-TT2R2 {Sex (female), Age (60 years), Medical history of ≥ 2 comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD/myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease (PAD), HF, previous stroke, pulmonary disease, and hepatic or renal disease), Treatment (interacting drugs, for example amiodarone), Tobacco use, Race (non-Caucasian)) score (Apostolakis, 2013), which can help to identify patients who are less likely to achieve a good TTR on VKA therapy (score > 2) and would do better with a DOAC. If such patients with SAMe-TT2R2> 2 are prescribed a VKA, greater efforts to improve TTR, such as more intense regular reviews, education/counselling, and frequent INR monitoring are needed or, more conveniently, the use of a DOAC should be reconsidered (Proietti, 2015).

Direct oral anticoagulants

In four pivotal RCTs, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban have shown non-inferiority to warfarin in the prevention of stroke/systemic embolism (Connoly, 2009; Patel, 2011; Granger, 2011; Giugliano, 2013). In a meta-analysis of these RCTs, DOACs were associated with a 19% significant stroke/systemic embolism risk reduction, a 51% reduction in haemorrhagic stroke (Ruff, 2014), and similar ischaemic stroke risk reduction compared with VKAs, but DOACs were associated with a significant 10% reduction in all-cause mortality (supplementary table 8). There was a non-significant 14% reduction in major bleeding risk, significant 52% reduction in ICH, and 25% increase in gastrointestinal bleeding with DOACs versus warfarin (Ruff, 2014).

The major bleeding relative risk reduction with DOACs was significantly greater when INR control was poor (i.e. centre-based TTR< 66%). A meta-analysis of the five DOAC-trials (RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy), ROCKET-AF (Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation), J-ROCKET AF, ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation), and ENGAGE AF TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation - Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48)) showed that, compared with warfarin, standard-dose DOACs were more effective and safer in Asians than in non-Asians (Wang, 2015). In the AVERROES (Apixaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid (ASA) to Prevent Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Who Have Failed or Are Unsuitable for Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment) trial of AF patients who refused or were deemed ineligible for VKA therapy, apixaban 5 mg b.i.d. (twice a day) significantly reduced the risk of stroke/systemic embolism with no significant difference in major bleeding or ICH compared with aspirin (Connolly, 2011).

Post-marketing observational data on the effectiveness and safety of dabigatran (Carmo, 2016; Huisman, 2018), rivaroxaban (Camm, 2016; Martinez, 2018), apixaban (Li, 2017), and edoxaban (Lee, 2018) versus warfarin show general consistency with the respective RCT. Given the compelling evidence about DOACs, AF patients should be informed of this treatment option.

Persistence to DOAC therapy is generally higher than to VKAs, being facilitated by a better pharmacokinetic profile of DOACs (Ingrasciotta, 2018) (Supplementary Table 9) and favourable safety and efficacy, especially amongst vulnerable patients including the elderly, those with renal dysfunction or previous stroke, and so on (Chao, 2018). Whereas patients with end-stage renal dysfunction were excluded from the pivotal RCTs, reduced dose regimens of rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and apixaban are feasible options for severe CKD (creatinine clearance (CrCl) 15 to 30 mL/min using the Cockcroft-Gault equation) (Stanton, 2017; Siontis, 2018). Considering that inappropriate dose reductions are frequent in clinical practice (Steinberg, 2016), thus increasing the risks of stroke/systemic embolism, hospitalization, and death, but without decreasing bleeding risk (Yao, 2017), DOAC therapy should be optimized based on the efficacy and safety profile of each DOAC in different patient subgroups.

Other antithrombotic drugs

In the ACTIVE W (Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events) trial, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and clopidogrel was less effective than warfarin for prevention of stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, and vascular death (the annual risk of events was 5.6% versus 3.9%, P =0.0003), with a similar rate of major bleeding (Connolly, 2006). In the ACTIVE-A trial, patients unsuitable for anticoagulation had a lower rate of thrombo-embolic complications when clopidogrel was added to aspirin compared with aspirin alone, but with a significant increase in major bleeding (Connolly, 2009). Aspirin monotherapy was ineffective for stroke prevention compared with no antithrombotic treatment and was associated with a higher risk of ischaemic stroke in elderly patients (Sjalander, 2014).

Overall, antiplatelet monotherapy is ineffective for stroke prevention and is potentially harmful, (especially amongst elderly AF patients) (Mant, 2007; Lip, 2011), whereas DAPT is associated with a bleeding risk similar to OAC therapy. Hence, antiplatelet therapy should not be used for stroke prevention in AF patients.

Combination therapy with oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs

The use of antiplatelet therapy remains common in clinical practice, often in patients without an indication (for example PAD, CAD, or cerebrovascular disease) beyond AF (Verheugt, 2018). There is limited evidence to support the combination therapy solely for stroke prevention in AF, with no effect on reductions in stroke, myocardial infarction, or death, but with a substantial increase in the risk of major bleeding and ICH (Mant, 2007; Lip, 2011).

Long-term oral anticoagulation per atrial fibrillation burden

Although the risk of ischaemic stroke/systemic embolism is higher with non-paroxysmal versus paroxysmal AF, and AF progression is associated with an excess of adverse outcomes (Potpara, 2012; Ogawa, 2018), the clinically determined temporal pattern of AF should not affect the decision regarding long-term OAC, which is driven by the presence of stroke risk factors (Ganesan, 2016). Management of patients with AHRE/subclinical AF is reviewed in module 10. Stroke risk in AHRE patients may be lower than in patients with diagnosed AF (Mahajan, 2018), and strokes often occur without a clear temporal relationship with AHRE/subclinical AF (Brambatti, 2014; Boriani, 2014), underscoring its role as a risk marker rather than a stroke risk factor (Freedman, 2017a; Freedman, 2017b). Whether AHRE and subclinical AF have the same therapeutic requirements as clinical AF 7 is presently unclear, and the net clinical benefit of OAC for AHRE/subclinical AF > 24 h is currently being studied in several RCTs (Freedman, 2017).

Notably, patients with subclinical AF/AHRE may develop atrial tachyarrhythmias lasting more than 24 h (Van Gelder, 2017) or clinical AF; hence careful monitoring of these patients is recommended, even considering remote monitoring, especially with longer AHRE and higher risk profile (Boriani, 2018). Given the dynamic nature of AF as well as stroke risk, a recorded duration in one monitoring period would not necessarily be the same in the next.

Long-term oral anticoagulation per symptom control strategy

Symptom control focuses on patient-centred and symptom-directed approaches to rate or rhythm control. Again, symptom control strategy should not affect the decision regarding long-term OAC, which is driven by the presence of stroke risk factors, and not the estimated success in maintaining sinus rhythm.

Management of anticoagulation-related bleeding risk

Strategies to minimize the risk of bleeding

Ensuring good quality of VKA treatment (TTR> 70%) and selecting the appropriate dose of a DOAC (as per the dose reduction criteria specified on the respective drug label) are important considerations to minimize bleeding risk. As discussed in Bleeding risk assessment, attention to modifiable bleeding risk factors should be made at every patient contact, and formal bleeding risk assessment is needed to help identify high-risk patients who should be followed up or reviewed earlier (for example 4 weeks rather than 4 to 6 months) (Lip, 2016). Concomitant regular administration of antiplatelet drugs or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) should be avoided in anticoagulated patients. Bleeding risk is dynamic, and attention to the change in bleeding risk profile is a stronger predictor of major bleeding events, especially in the first 3 months (Chao, 2018).

High-risk groups

Certain high-risk AF populations have been under-represented in RCTs, including the extreme elderly (≥ 90 years), those with cognitive impairment/dementia, recent bleeding or previous ICH, end-stage renal failure, liver impairment, cancer, and so on. Observational data suggest that such patients are at high risk for ischaemic stroke and death, and many would benefit from OAC.

Patients with liver function abnormalities may be at higher risk of bleeding on VKA, possibly less so on DOACs. Observational data in cirrhotic patients suggest that ischaemic stroke reduction may outweigh bleeding risk (Pastori, 2018; Kuo, 2017; Lee, 2019).

In patients with a recent bleeding event, attention should be directed towards addressing the predisposing pathology (for example bleeding ulcer or polyp in a patient with gastrointestinal bleeding), and the reintroduction of OAC as soon as feasible, as part of a multidisciplinary team decision. Consideration should be made for drugs such as apixaban or dabigatran 110 mg b.i.d., which are not associated with an excess of gastrointestinal bleeding compared with warfarin. Where OAC is not reintroduced, there is a higher risk of stroke and death compared with restarting OAC, although the risk of rebleeding may be higher (Staerk, 2015). Similarly, thromboprophylaxis in cancer may require a multidisciplinary team decision balancing stroke reduction against serious bleeding, which may be dependent on cancer type, site(s), staging, anti-cancer therapy and so on.

Thromboprophylaxis in specific high-risk groups is discussed in detail throughout module 8.

Decision making to avoid stroke

In observational population cohorts, both stroke and death are relevant endpoints, as some deaths could be due to fatal strokes (given that endpoints are not adjudicated in population cohorts, and cerebral imaging or post-mortems are not mandated). As OAC significantly reduces stroke (by 64%) and all-cause mortality (by 26%) compared with control or placebo (Hart, 2007), the endpoints of stroke and/or mortality are relevant in relation to decision making for thromboprophylaxis.

The threshold for initiating OAC for stroke prevention, balancing ischaemic stroke reduction against the risk of ICH and associated QoL, has been estimated to be 1.7%/year for warfarin and 0.9%/year for a DOAC (dabigatran data were used for the modelling analysis) (Eckman, 2011). The threshold for warfarin may be even lower, if good-quality anticoagulation control is achieved, with average TTR> 70% (Proietti, 2016). Given the limitations of clinical risk scores, the dynamic nature of stroke risk, the greater risk of stroke and death among AF patients with ≥ 1 non-sex stroke risk factor, and the positive net clinical benefit of OAC among such patients, we recommend a risk-factor-based approach to stroke prevention rather than undue focus on (artificially defined) ‘high-risk’ patients. As the default is to offer stroke prevention unless the patient is low risk, the CHA2DS2-VASc score should be applied in a reductionist manner, to decide on OAC or not (Lip, 2016).

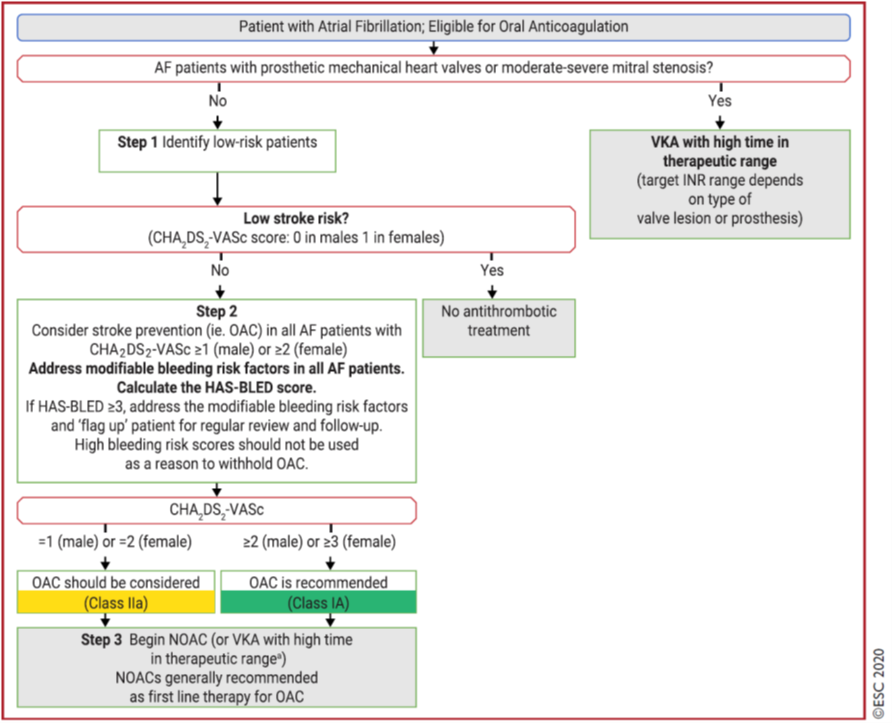

Thus, the first step in decision making (‘A’ Anticoagulation/Avoid stroke) is to identify low-risk patients who do not need antithrombotic therapy. Step 2 is to offer stroke prevention (i.e., OAC) to those with ≥ 1 non-sex stroke risk factors (the strength of evidence differs, with multiple clinical trials for patients with ≥ 2 stroke risk factors, and subgroups from trials/observational data on patients with 1 non-sex stroke risk factor). Step 3 is the choice of OAC-a DOAC (given their relative effectiveness, safety and convenience, these drugs are generally first choice as OAC for stroke prevention in AF) or VKA (with good TTR at > 70%). This ‘AF 3-step’ patient pathway (Freedman, 2016; Lip, 2015) for stroke risk stratification and treatment decision making is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 A - Anticoagulation/Avoid stroke: The ‘AF 3-step’ pathway (source: Hindricks, 2020)

AF = atrial fibrillation; CHA2DS2-VASc = Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥ 75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke, Vascular disease, Age 65 to 74 years, Sex category (female); HAS-BLED = Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly (> 65 years), Drugs/alcohol concomitantly; INR = international normalized ratio; NOAC = non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (referred to as DOAC in this guideline); OAC = oral anticoagulant; SAMe-TT2R2 = Sex (female), Age (< 60 years), Medical history, Treatment (interacting drug(s)), Tobacco use, Race (non-Caucasian) (score); TTR = time in therapeutic range; VKA = vitamin K antagonist

aIf a VKA being considered, calculate SAMe-TT2R2 score: if score 0 to 2, may consider VKA treatment (for example warfarin) or DOAC; if score > 2, should arrange regular review/frequent INR checks/ counselling for VKA users to help good anticoagulation control, or reconsider the use of DOAC instead; TTR ideally >70%

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Patiënten met atriumfibrilleren (AF) hebben een vijfvoudig verhoogd risico op een trombo-embolische episode/herseninfarct in vergelijking met mensen zonder AF. De absolute incidentie van herseninfarct is sterk afhankelijk van bijkomende risicofactoren zoals leeftijd en wordt bepaald aan de hand van de CHA2DS2-VASc-score. Orale antistolling met directe orale anticoagulantia (DOAC’s) of vitamine K antagonisten (VKA) verlagen dit risico met 65-70%. Bij de indicatiestelling voor anticoagulantia dienen risicofactoren voor bloedingen meegewogen te worden.

Deze module geldt niet voor patiënten met atriumfibrilleren in combinatie met een mechanische hartklep of matig tot ernstige mitralisstenose. Hiervoor wordt verwezen naar de module Atriumfibrilleren en valvulaire hartziekte.

Deze module betreft niet het beleid rondom katheterablatie bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren. Hiervoor wordt verwezen naar de module Peri-procedureel management ter preventie van herseninfarct bij patiënten die ritme-controle interventies ondergaan.

Zoeken en selecteren

To answer the clinical question, the ESC-guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation from 2020 (Hindricks, 2020) was used.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 17-10-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-09-2022

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2018 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met atriumfibrilleren.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. N.M.S. (Natasja) de Groot, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus Medisch Centrum te Rotterdam, NVVC (voorzitter)

- P.H. (Pepijn) van der Voort, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Catharina Ziekenhuis te Eindhoven, NVVC

- Dr. M.E.W. (Martin) Hemels, cardioloog, werkzaam in het Rijnstate Ziekenhuis te Arnhem en RaboudUMC te Nijmegen, NVVC

- Dr. T.J. (Thomas) van Brakel, thoraxchirurg, werkzaam in het Catharina Ziekenhuis te Eindhoven, NVTNET

- Dr. M. (Michiel) Coppens, internist-vasculair geneeskundige, werkzaam in de Amsterdam Universitair Medische Centra te Amsterdam, NIV

- Dr. S. (Sander) van Doorn, huisarts, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht te Utrecht, NHG

- Prof. dr. M.K. (Kamran) Ikram, neuroloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus Medisch Centrum te Rotterdam, NVN

- H. (Hans) van Laarhoven, zelfstandig adviseur, werkzaam bij Laerhof Advies, Harteraad

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. B.H. (Bernardine) Stegeman, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

De Groot (voorzitter) |

Cardioloog-elektrofysioloog, Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam |

Mede-oprichter Stichting Atrial Fibrillation Innovation Platform |

Unrestricted grant voor AF bij Hartfalen, Pathofysiologische onderzoek (valt buiten de afbakening) |

Geen (valt buiten de afbakening) |

|

Brakel |

Cardio-thoracaal chirurg |

Verzorgen van trainingen voor chirurgische behandeling van AF (Trainingscontract met Medtronic; inkomsten voor de afdeling) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Coppens |

Internist-vasculaire geneeskunde |

* Wetenschappelijke adviesraad Trombosestichting Nederland (onbetaald). |

Betaald adviseurschap of betaalde lezingen/nascholingen voor Bayer, Daiichi Investigator initiated studies met externe financiële ondersteuning en door industrie geïnitieerde studies Bayer, UniQure, Roche CSL Behring and Daiichi Sankyo |

Geen (valt buiten de afbakening, niet over AF-patiënten; onderzoek ging bijvoorbeeld over DOAC bij short bowel patiënten) |

|

Van der Voort |

Cardioloog-electrofysioloog Catharinaziekenhuis Eindhoven |

Bestuurslid van NHRA, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Laarhoven |

Zelfstandig adviseur voor de zorg |

Bestuurslid LAREB, vergoeding conform normering NTVZ Voorzitter Raad van Toezicht stichting Leefh, vergoeding conform NVTZ |

* Lid Patientenadviesraad Pfizer, vacatievergoeding * Adviesraad ‘NOAC’ (eenmalig 2019, vacatievergoeding) |

Geen |

|

Van Doorn |

* Assistant professor, Julius Centrum, UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

* Betrokken als co-PI van het ALL-IN onderzoek, naar de substitutie van AF zorg van de 2e lijn naar de huisarts, inclusief behandeling met anticoagulantia: doe 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa055 (afgerond) * co-PI betrokken bij het FRAIL-AF onderzoek, een gerandomiseerd onderzoek naar de veiligheid en effectiviteit van DOAC’s bij kwetsbare ouderen: trialregister.nl NTR6721, doi 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032488 (lopend) * Betrokken bij onderzoek met routine zorg data (CPRD) naar de veiligheid en effectiviteit van DOAC’s, en een systematische review naar DOAC doseringen. |

Geen |

|

Hemels |

* Cardioloog-elektrofysioloog Rijnstate ziekenhuis * Programmaleider NVVC Connect atriumfibrilleren |

* Associate editor van Netherlands Heart Journal, géén vergoeding * Onderwijsactiviteiten voor medisch specialisten, huisartsen, (ziekenhuis)apothekers en arts-assistenten/physician assisants, betreft urenvergoeding

|

* Principal investigator (samen met prof. M.V. Huisman) van het Dutch AF onderzoeks en registratieproject namens de NVVC en in opdracht van VWS/ZonMw. Er gaat een vergoeding naar de vakgroep cardiologie in het Rijnstate i.v.m. mijn werkzaamheden voor dit project, ook gefinancierd door FNT * Local principal investigator van diverse patiëntgebonden studies (hartritmestoornissen gerelateerd) in het Rijnstate ziekenhuis, géén persoonlijke vergoeding hiervoor |

Geen |

|

Ikram |

Hoogleraar Klinische Neuro-epidemiologie en neuroloog, Afdelingen Neurologie & Epidemiologie, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Stegeman |

Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Meelezer |

||||

|

Jakulj |

* Internist-nefroloog Amsterdam UMC en Dianet * Lid richtlijnencommissie Nederlandse Federatie voor Nefrologie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Harteraad en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module 1 Definitie en diagnose van atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 2 Atriumfibrilleren, subtype, burden en progressie |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 3 Screenen voor atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 4 Integrale behandeling voor patiënten met atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 5.1 Antitrombotisch beleid ter preventie van herseninfarct |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 5.2 Afsluiting of verwijdering van het linker hartoor |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.1 Frequentiecontrole |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.2 Ritmecontrole |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.2.1 Ritmecontrole met antiaritmische medicatie |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.3 Katheterablatie |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.4 Chirurgie voor atriumfibrilleren en concomitante chirurgie voor atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.5 Hybride katheter-/ chirurgische ablatie procedures |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 6.6 Peri-procedureel management ter preventie van herseninfarct |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 7 Cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en bijkomende ziekten |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.1 Atriumfibrilleren bij hemodynamische instabiliteit |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.2 Acute coronaire syndromen, chronisch coronairlijden, en percutane en chirurgische revascularisaties bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.3 Acuut herseninfarct of hersnebloeding bij patiënten met atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.4 Bloeding ten tijde van antistolling |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.5 Atriumfibrilleren en valvulaire hartziekte |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.6 Atriumfibrilleren en chronische nierschade |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.7 De oudere en kwetsbare patiënt met atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.8 Atriumfibrilleren en aangeboren hartafwijkingen |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.9 Atriumfibrilleren bij erfelijke hartspierziekten |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.10 Atriumfibrilleren tijdens de zwangerschap |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.11 Atriumfibrilleren in professionele sporters |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 8.12 Postoperatief atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 9 Sekse-gerelateerde verschillen in atriumfibrilleren |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module 10 Epidemiologie, implicaties en behandeling van subklinisch AF/AHRE |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

Implementatie

De werkgroep is vooral inhoudelijk bezig geweest met het aanpassen van de ESC-richtlijn ‘Diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation’ naar de Nederlandse praktijk. De werkgroep heeft een aantal suggesties gegeven voor het onder de aandacht brengen bij medische professionals van de nieuwe richtlijn. De verdere implementatie van de aanbevelingen uit de richtlijn valt buiten de expertise van de werkgroep.

Voorstel voor te ondernemen acties per partij

Hieronder wordt per partij toegelicht welke acties zij kunnen ondernemen om aandacht te geven aan de richtlijn.

Alle direct betrokken wetenschappelijk verenigingen/beroepsorganisaties

- Bekend maken van de richtlijn onder de leden.

- Publiciteit voor de richtlijn maken door over de richtlijn te publiceren in tijdschriften en te vertellen op congressen.

De lokale vakgroepen/individuele medisch professionals

- Het bespreken van de aanbevelingen in de vakgroepsvergadering en lokale werkgroepen.

- Het bespreken van de richtlijnen in de onderwijsuren van de medisch specialist in opleiding

- Het volgen van bijscholing die bij deze richtlijn ontwikkeld gaat worden.

- Afstemmen en afspraken maken met andere betrokken disciplines om de toepassing van de aanbevelingen in de praktijk te borgen.

Het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

Toevoegen van de richtlijn aan de Richtlijnendatabase.

Werkwijze

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met atriumfibrilleren. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door het Zorginstituut Nederland, Zelfstandige Klinieken Nederland, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie, Vereniging Innovatieve Geneesmiddelen, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie, Federatie voor Nederlandse Trombosediensten, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Hart- en Vaatverpleegkundigen, Nederland Huisartsen Genootschap en Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd via Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbevelingen)

De Engelse tekst uit de ESC-richtlijn Diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation uit 2020 (Hindricks, 2020) is overgenomen, tenzij er argumenten voor de Nederlandse praktijk van belang zijn. De tekst is vervolgens aangepast en in het Nederlands opgesteld.

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. GRADE staat voor Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Vertalen van aanbevelingen

De European Society of Cardiology gebruikt een standaardformulering voor de aanbevelingen op basis van de klasse en niveau van het bewijs. Deze standaardformulering met vertaling naar het Nederlands staat in de onderstaande tabel weergegeven.

|

Class of recommendations |

Suggested wording to use |

Nl’se vertaling, gehanteerd door onder andere de CVRM-richtlijn |

|

I |

Is recommended/is indicated |

Sterke aanbeveling met een actieve, directieve formulering, zoals behandel, streef naar, et cetera |

|

II |

|

|

|

IIa |

Should be considered |

Zwakke aanbeveling met een actieve, directieve formulering, zoals overweeg |

|

IIb |

May be considerd |

Zwakke aanbeveling met als formulering: kan worden overwogen |

|

III |

Is not recommended |

Sterke aanbeveling met een actieve, directieve formulering, zoals behandel niet, et cetera |

CVRM, CardioVasculair RisicoManagement

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) (published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 29). Eur Heart J. 2020;ehaa612. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.