Behandeling buikvenetrombose

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale antistollingsbehandeling voor patiënten met acute buikvenetrombose?

Aanbeveling

Behandel patiënten met een buikvenetrombose (inclusief patiënten met Budd-Chiari syndroom (BCS)) in de acute fase met therapeutisch gedoseerde laagmoleculairgewicht heparine (LMWH).

Overweeg patiënten met een buikvenetrombose na de acute fase te behandelen met een vitamine K antagonist (VKA). Behandeling met een directe orale anticoagulantia (DOAC, Factor Xa-remmer) is ook een optie.

- Overweeg behandeling met een DOAC alleen als er geen sprake is van BCS, Child-Pugh C levercirrose, veneuze darmischemie of ernstige nierfunctiestoornissen.

- Indien gekozen wordt voor behandeling met een DOAC: kies voor een Factor Xa-remmer bij patiënten met buikvenetrombose zonder levercirrose.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de geïncludeerde studies zijn we onzeker over het effect van direct orale anticoagulantia (DOACs) op de cruciale uitkomstmaten majeure bloeding, progressie van buikvenetrombose, (partiële) resolutie van buikvenetrombose en mortaliteit, vergeleken met conventionele antistollingsmedicatie (vitamine K antagonisten (VKA) en laagmoleculairgewicht heparine (LMWH)) in patiënten met een acute buikvenetrombose. Dit geldt voor de totale groep patiënten, alsook voor de patiënten met levercirrose en patiënten zonder levercirrose. De bewijskracht van de gevonden resultaten is erg beperkt, met name vanwege het risico op bias en imprecisie. Ook zijn we onzeker over het effect van DOACs op de belangrijke uitkomstmaten recidief veneuze trombo-embolie (VTE, inclusief buikvenetrombose) en noodzaak voor chirurgische of radiologische ingreep. Geen van de geïncludeerde studies rapporteerde gegevens over de uitkomstmaten leverfalen en levertransplantatie. De overall bewijskracht voor deze module is dan ook zeer laag en er is duidelijk sprake van een kennislacune.

De literatuur is niet eenduidig over de toepassing van DOACs bij de diverse types buikvenetrombose. In de geïncludeerde studies zijn voornamelijk patiënten met portatrombose en in mindere mate met v. mesenterica, v. lienalis trombose en trombose van meerdere buikvenen tegelijkertijd. Patiënten met een Budd-Chiari syndroom (BCS) ontbraken in de geïncludeerde studies. Het is daarom ook niet zeker of de gevonden effecten van DOACs op de cruciale uitkomstmaten van toepassing zijn op de diverse types buikvenetrombose, en in het bijzonder bij patiënten met BCS. Ook varieerde het gebruikte type DOAC tussen de studies, waarbij de meerderheid van de patiënten een Factor Xa-remmer (FXa-remmers) kreeg en een kleine minderheid dabigatran. Helaas zijn er ook geen RCT’s waarin behandeling met DOACs vergeleken worden met VKA/LMWH bij patiënten met een acute SVT. Resultaten uit een niet-vergelijkende cohortstudie waarin patiënten met non-cirrotische acute buikvenetrombose werden behandeld met een DOAC (rivaroxaban), suggereren dat behandeling met rivaroxaban een alternatief zou kunnen zijn voor de standaard antistollingsbehandeling (Ageno, 2022).

De standaardbehandeling van patiënten met een acute buikvenetrombose die een indicatie hebben voor behandeling met antistolling, is therapeutisch LMWH en voor de langere termijn meestal gevolgd door VKA met een streef International Normalized Ratio (INR) tussen 2,0 en 3,0. Hierbij wordt veelal gekozen voor LMWH en niet voor ongefractioneerde heparine (UFH), tenzij er sprake is van een contra-indicatie voor LMWH. Het doel van deze module was te onderzoeken of behandeling met DOACs een plaats heeft bij deze patiënten. Ondanks het feit dat we onzeker zijn over het effect van DOACs op de cruciale uitkomstmaten, suggereren de gevonden resultaten dat DOACs, waarbij met name de FXa-remmers zijn onderzocht en in mindere mate dabigatran, in ieder geval niet meer bloedingen of meer recidief trombose gaven, maar minstens vergelijkbare bloedingsrisico’s en effectiviteit hadden als LMWH of VKA. Daarnaast is het in de klinische praktijk vaak lastig of niet goed mogelijk om bij het stellen van de diagnose buikvenetrombose te weten hoe lang deze al aanwezig is, en daarmee of het om een acute of een chronische buikvenetrombose gaat. Ook is onbekend welke invloed dergelijke kennis heeft op de kansen op een bloeding of trombose en daarmee ook op de veiligheid en de effectiviteit van de behandeling.

Met de acute fase wordt het moment van diagnose bedoeld, waarin sommige patiënten klinisch worden behandeld. Het post-acute moment kenmerkt zich door belangrijk herstel van klachten en de ambulante setting waarbij orale intake geen probleem (meer) is.

Een buikvenetrombose kent meerdere mogelijke oorzaken of omstandigheden waarin deze kan ontstaan. Een bekende setting is bij een infectieuze of inflammatoire ziekte in de buikholte, zoals pancreatitis of inflammatoire darmziekten (IBD). In de studie van Naymagon (2021-B) zijn patiënten met IBD geïncludeerd. Het aantal events voor de uitkomstmaten majeure bloeding en mortaliteit was te laag om uitspraken te kunnen doen over het effect van DOACs vergeleken met conventionele antistolling. Een andere risicogroep zijn patiënten met een maligniteit, in het bijzonder patiënten met een hepatocellulair carcinoom. Zij waren wisselend vertegenwoordigd in de studies en de resultaten en aantallen zijn te beperkt om hier conclusies uit te trekken. Tenslotte is er ook een verschil in patiënten met en zonder levercirrose. Het is mogelijk dat DOACs bij patiënten met gevorderde levercirrose een ander risicoprofiel hebben. In het BAVENO-consensus document wordt aangegeven dat het daarom niet mogelijk is een aanbeveling te doen over de inzet van DOACs bij deze groep patiënten (de Franchis, 2022). In de recente ISTH-richtlijn over antistolling bij een vena porta trombose en levercirrose is de aanbeveling voor patiënten met Child-Pugh A of B levercirrose om te behandelen met een DOAC of LMWH, eventueel gevolgd door VKA. Bij patiënten met Child-Pugh C levercirrose heeft LMWH, eventueel gevolgd door VKA, de voorkeur (Carlin, 2024). Het behandelen van patiënten met een verminderde leverfunctie en een daarbij verlengde INR, kan de behandeling met VKA bemoeilijken. Dit geldt ook voor de interpretatie van de zogenaamde MELD-score, die gebruikt wordt voor de urgentiebepaling bij patiënten op de levertransplantatie-wachtlijst. LMWH blijft dan de antistolling van voorkeur, al kent dit middel voor chronisch gebruik ook beperkingen.

Er is onvoldoende bewijs om het gebruik van DOACs bij patiënten met BSC te adviseren. Er is wel ervaring vanuit de klinische praktijk om dit in individuele gevallen voor te schrijven door voorschrijvers die ervaren zijn met de behandeling van patiënten met BSC.

In het BAVENO-consensus document worden verschillende uitspraken gedaan over het gebruik van DOACs bij patiënten met een buikvenetrombose (de Franchis, 2022). Zo geven zij aan dat er bij patiënten met een verhoogd risico op bloedingen, zoals in het geval van trombocytopenie bij splenomegalie, een individuele afweging gemaakt moet worden. Een ander bloedingsrisico is het hebben van slokdarmvarices, zoals kan ontstaan door portale hypertensie ten gevolge van buikvenetrombose. Derhalve wordt in het BAVENO-consensus document aangegeven dat het raadzaam is om patiënten te screenen op slokdarmvarices en deze te behandelen, indien mogelijk voor de start van antistolling (de Franchis, 2022). De werkgroep is van mening dat het gebruik van antistolling bij patiënten met slokdarmvarices op individuele basis afgewogen moet worden. Als er een indicatie is voor antistollingsmedicatie, heeft de aanwezigheid van slokdarmvarices geen consequenties voor de keuze van het antistollingsmiddel.

De voordelen van parenterale - boven orale - behandeling van een buikvenetrombose zijn theoretisch, tenzij er sprake is van darmischemie. In dat geval is orale therapie niet mogelijk door het kritisch ziek zijn van de patiënt. Ook is de absorptie van orale medicatie in die setting redelijkerwijs verstoord. Het ontbreken van een streefwaarde maakt monitoring van het therapeutische effect van DOACs in deze setting onmogelijk. Het is onbekend wat het effect is van buikvenetrombose die niet gepaard gaat met fulminante darmischemie, maar wel met macro- of microscopisch oedeem van de darmwand, op de absorptie.

Kortom, realiserend dat gerandomiseerde studies ontbreken, de kwaliteit van het bewijs erg laag is en de geïncludeerde studies onvoldoende antwoord geven op de gestelde vragen, is het voorstelbaar dat er, na stabilisatie van het ziektebeeld, toch gekozen wordt voor het gebruik van een DOAC (FXa-remmer) als behandeling van een acute buikvenetrombose, tenzij er sprake is van BCS en cruciale comorbiditeit zoals Child-Pugh C levercirrose, darmischemie of ernstige nierfunctiestoornissen. Bij patiënten met matige levercirrose of Child-Pugh B, is voorzichtigheid geboden (de Franchis, 2022). Bij patiënten met Child-Pugh A kunnen DOACs worden voorgeschreven. De duur van de behandeling moet op individuele basis bepaald worden. Daarbij kunnen de volgende factoren meegewogen worden: locatie van de buikvenetrombose, aanwezigheid van slokdarmvarices of andere risicofactoren voor een bloeding, aanwezigheid van persisterende risicofactoren, andere relevante comorbiditeiten en de voorkeuren van de patiënt.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Naast een mogelijk verschillend risico op bloedingen of recidief trombose, waar de huidige studies onvoldoende uitsluitsel over geven, is voor patiënten het verschil in gebruiks(on)gemak tussen de verschillende anticoagulantia van belang. Waar DOACs een een- of tweemaal daagse inname vereisen, is bij een behandeling met VKA een eenmaal daagse dosering voldoende. Daarnaast is het meten van de INR nodig bij behandeling met VKA, meestal eens per twee tot zes weken, waar bij chronisch gebruik zelfmeten wordt gestimuleerd. In 2020 publiceerde het Zorginstituut Nederland het rapport ‘Evaluatie van de ervaringen en kosten van antistollingszorg (van Dijk, 2020). In dit rapport komt naar voren dat DOAC-gebruikers meer vrijheid ervaren door het overbodig worden van bezoeken aan de trombosedienst. Tegelijkertijd ervaren VKA-gebruikers die zelf meten en doseren ook een grote regie over hun leven.

Het grootste nadeel van DOACs (FXa-remmer) is het ontbreken of beperkte ervaring met een adequaat en direct antidotum wat het gebruik bij een hoog bloedingsrisico of in de setting van een levertransplantatie-wachtlijst onpraktischer maakt. Daarnaast is de klaring van de DOACs grotendeels afhankelijk van de nier- en leverfunctie, wat bij deze patiëntengroep relevant kan zijn.

Het grootste nadeel van de VKA-behandeling is de potentiële ontregeling van de INR door diverse factoren, zoals infecties, koorts, interacterende medicatie maar ook stress of veranderde voeding. Indien door een onderliggende leveraandoening de INR al spontaan verlengd is, kan deze de (stabiliteit van de) behandeling met VKA bemoeilijken. Ook kan het de zogenaamde MELD-score beïnvloeden, die gebruikt wordt voor patiënten op de levertransplantatie-wachtlijst.

Naast een behandeling met tabletten is behandeling met subcutane injecties (LMWH) mogelijk, die een- of tweemaal daags geprikt moeten worden. De meeste patiënten vinden injecties meer belastend dan tabletten en niet iedere patiënt kan zichzelf die injecties toedienen. Hierdoor zijn mantelzorgers of thuiszorg voor deze behandeling noodzakelijk.

Onderzoek naar voorkeuren van patiënten is schaars, maar in het algemeen wordt gevonden dat orale behandeling de voorkeur heeft boven injecties, mits deze even effectief en veilig is (Hutchinson, 2019). Het is van belang om bovenstaande afwegingen met de patiënt te bespreken, om zo samen tot een passende behandeling te komen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In het rapport ‘Evaluatie van de ervaringen en kosten van antistollingszorg’ wordt ook aandacht gegeven aan de kosten. Hierbij was de conclusie dat de kosten voor antistollingszorg gestegen waren, met name door de hogere kosten van DOAC ten opzichte van VKA. LMWH is daarentegen bij de hoogste therapeutische dosering iets duurder dan een DOAC (Farmacotherapeutisch kompas). Tenslotte zijn de meeste DOACs inmiddels (2024) uit patent en zijn de kosten van deze medicatie daardoor ook lager geworden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Alle drie de vormen van antistolling, dus LMWH, VKA en DOAC zijn gebruikelijk en gekend in de zorg voor patiënten met trombose. De verwachting is daarom dat de aanbevelingen haalbaar zijn in de klinische praktijk.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is geen literatuur van goede kwaliteit over de voorkeursbehandeling met antistolling bij patiënten met een acute buikvenetrombose. De behandeling met LWMH in de acute fase en vervolgens LMWH of VKA in de post-acute fase is de huidige standaard en kan nog steeds worden aanbevolen. In overleg met de patiënt kan een DOAC als alternatief worden voorgeschreven voor de post-acute fase, mits in afwezigheid van BCS en cruciale comorbiditeit zoals Child-Pugh C levercirrose, darmischemie of ernstige nierfunctiestoornissen.

Met de acute fase wordt het moment van diagnose bedoeld, waarin sommige patiënten klinisch worden behandeld. Het post-acute moment kenmerkt zich door belangrijk herstel van klachten en de ambulante setting waarbij orale intake geen probleem (meer) is. Daarnaast is het belangrijk bij de start van antistollingsbehandeling, of binnen enkele weken na start, de aanwezigheid van slokdarmvarices te beoordelen en indien aanwezig te behandelen. Dit met het risico op potentieel levensbedreigende bloedingen.

Gezien het ontbreken van voldoende bewijs over de veiligheid en effectiviteit van DOACs in vergelijking met de huidige behandeling met LMWH of VKA zijn de aanbevelingen zwak geformuleerd. Deze onzekerheid maakt dat de behandeling met LMWH of VKA ook in de post-acute fase de keuze van voorkeur blijft, waarbij het niet zeker is of een DOAC een verstandig(er) alternatief is.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Patients with acute symptoms of splanchnic vein thrombosis (SVT, thrombosis of mesenteric vein, portal vein, splenic vein, and/or hepatic veins) are treated with anticoagulants. Treatment with anticoagulants seems beneficial for prevention of recurrent thrombosis, bleeding and development of portal hypertension (Candeloro, 2022; Valeriani, 2021 and Valeriani, 2021). Traditionally vitamin K antagonists (VKA) or low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) have been described for this type of venous thromboembolism (VTE). The large direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) RCTs were performed in patients with deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism and patients with SVT were not included. The question is whether DOACs can be recommended for the treatment of patients with SVT having an indication for anticoagulants. Since many patients with SVT may have comorbidities/ bleeding risk factors, including portal hypertension and oesophageal varices, that are of clinical relevance for the use of anticoagulation and particularly DOACs, the lack of (experience in) a widely available antidote, can have clinical implications and part of decision making. Here we reviewed the present literature on the use of DOACs in patients with SVT.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

General remarks

In selection of the studies, it seemed difficult to select the studies that only included patients with an acute SVT. In part of the studies, it was not specified whether patients with acute and/or chronic SVT were included (Nagaoki, 2018 and Zhang, 2023). The working group decided to include those studies in the literature analysis, as in clinical practice it is also often not known if a SVT is recent or of older age. Besides, in most of the studies patients with PVT were included and it is therefore not sure whether results are also applicable to patients with other SVT. It is important to take this into account in interpreting the results.

Major bleeding

Total group and patients with cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure major bleeding when compared with LMWH/VKA in adult patients with SVT/in adult patients with SVT and cirrhosis.

Sources: Valeriani, 2021; Ilcewicz (2021); Naymagon (2021); Kawata (2021) and Zhang (2023) |

Patients without cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure major bleeding (according to ISTH criteria) for patients without cirrhosis. Therefore no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure major bleeding in patients with SVT without cirrhosis, compared to LMWH/VKA.

|

Progression of SVT

Total group and patients with cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure progression of SVT when compared with LMWH/VKA in adult patients with SVT/in adult patients with SVT and cirrhosis.

Source: Valeriani, 2021; Ilcewicz, 2021; Kawata, 2021 and Naymagon, 2021 |

Patients without cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure progression of SVT for patients without cirrhosis. Therefore no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure progression of SVT in patients with SVT without cirrhosis, compared to LMWH/VKA.

|

(Partial) Resolution of SVT

Total group and patients with cirrhosis and without cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT when compared with LMWH/VKA in adult patients with SVT.

Sources: Valeriani, 2021; Kawata, 2021; Naymagon, 2020; Naymagon, 2021, Naymagon, 2021_B and Zhang, 2023 |

Mortality

Total group and patients with cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure mortality when compared with LMWH/VKA in adult patients with SVT/in adult patients with SVT and cirrhosis.

Source: Naymagon, 2021 |

Patients without cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

No GRADE |

Data is too limited. Therefore no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure mortality in patients with SVT without cirrhosis, compared to LMWH/VKA.

Source: Naymagon (2020) |

Clinically relevant non major bleeding

Total group (DOAC vs VKA or LMWH)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure CRNMB (according to ISTH criteria) when compared with LMWH/VKA in adult patients with SVT.

Source: Kawata,2021 |

Patients with cirrhosis and patients without cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure CRNMB (according to ISTH criteria) for patients with cirrhosis and patients without cirrhosis. Therefore no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure CRNMB in patients with SVT with cirrhosis and patients with SVT without cirrhosis, compared to LMWH/VKA.

|

Recurrent VTE

Total group (DOAC vs VKA)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure recurrent VTE when compared with VKA in adult patients with SVT.

Source: Ilcewicz, 2021 |

Total group (DOAC vs LMWH)

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure recurrent VTE for patients without cirrhosis. Therefore no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure recurrent VTE in patients with SVT nor on patients with SVT with cirrhosis, compared to LMWH.

|

Patients with cirrhosis and patients without cirrhosis (all comparisons)

|

No GRADE |

Data is too limited. Therefore no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure mortality in patients with SVT without cirrhosis, compared to LMWH/VKA.

Sources: Naymagon, 2020 and Ilcewicz, 2021 |

Liver failure

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure liver failure. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure liver failure in adults with acute SVT compared to LMWH/VKA.

|

Liver transplantation

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure liver transplantation. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure liver transplantation in adults with SVT compared to LMWH/VKA.

|

Need for surgical or radiological intervention

|

No GRADE |

Data was too limited. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure need for surgical or radiological intervention in adults with acute SVT compared to LMWH/VKA.

Sources: Naymagon, 2020 and Naymagon, 2021_B |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Valeriani (2021) performed a systematic review to evaluate the effect of anticoagulation treatments in adults with splanchnic vein thrombosis. Several databases were searched up to December 2019, including Medline and Embase. They included 97 studies (N=7969), of which four studies reported data on the effect of treatment with direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) (Hanafy, 2019; Nagaoki, 2018; Wille, 2019 and Sharma, 2020). However, only the study of Nagaoki (2018) was included in our literature analysis, since the publication of Hanafy (2019) was retracted, Sharma (2020) included also patients in the DOAC-group, when they switched from treatment with VKA to treatment with DOAC and the number of patients using DOAC was too limited in Wille (2018). Quality of the observational studies was assessed using the ROBINS-I tool.

Naymagon (2020) performed a retrospective cohort study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of DOACs in patients with non-cirrhotic acute portal vein thrombosis (PVT), compared to treatment with VKA, LMWH or no anticoagulation. They included 330 patients in a large urban tertiary center in the USA. In total, 108 patients received warfarin, 70 patients received enoxaparin and 93 patients received DOACs. Results on the no anticoagulation group are not considered in our literature analysis. Results on the outcome bleeding events and mortality were reported for the different anticoagulation groups, which was the case for other outcome measures.

Ilcewicz (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of DOACs in patients with new PVT, compared to treatment with warfarin. They included 33 patients admitted to a large academic medical center in the USA. In total, 20 patients received DOACs and 13 patients received warfarin. Patients with cirrhosis were also included (N=10). Important outcome measures were bleeding events and recurrence of thrombo-embolic events.

Kawata (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study to evaluate the management and outcomes of patients with SVT. They included 155 patients with a newly diagnosed episode of SVT at the Thrombosis Clinic in a tertiary care hospital in Canada, of which 47 received DOAC and 98 received LWMH or VKA. SVT should have been objectively documented by imaging. Patients with cirrhosis were also included. Progression of SVT, major bleeding and clinically relevant non major bleeding (CRNMB) were important outcome measures.

Naymagon (2021) performed a retrospective cohort study to share their experiences with the anticoagulation treatment of patients with PVT and liver cirrhosis. They included 214 patients with an acute PVT and cirrhosis which were seen in a tertiary care hospital in the USA and primarily focused on the comparison between patients treated with anticoagulation (DOAC (N=18), warfarin (N=26) and enoxaparin (N=42)), and patients not treated with anticoagulation. Patients not receiving any anticoagulant were not included in our analysis. They also reported outcomes by the different anticoagulants, namely major bleeding, mortality and extension of the PVT.

Naymagon (2021-B) performed a retrospective cohort study to compare anticoagulants in the treatment of patients with acute PVT and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). They included 63 patients which were seen in a tertiary care hospital in the USA. Patients received DOAC (N=23), warfarin (N=22) or enoxaparin (N=13). Five patients did not receive any anticoagulation, but were not included in our analysis. They reported on amongst others mortality, major bleeding and need for an additional intervention.

Zhang (2023) performed a retrospective cohort study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of anticoagulants in the treatment of PVT in patients with cirrhosis. They included 77 patients who were admitted to the liver disease center of a tertiary hospital in China. Their study focused primarily on the comparison between anticoagulation (DOAC, N=18; warfarin, N=6, heparin, N=1 and nadroparin, N=2)) and no-anticoagulation (N=50). They only compared the safety of DOAC versus warfarin. Therefore only data on the outcome measure major bleeding is included in our analysis.

Table 1 lists more details on the included studies.

|

Author, year (design) |

Participants |

Characteristics of PVT |

Liver cirrhosis and malignancy (%) |

Intervention |

Comparison |

Follow-up |

|

Nagaoki (2018), retrospective |

N=50 (I: 20, C: 30)

Age: I: 69 (53-74), C: 67 (24-83)

Sex (M): I: 35, C: 57 |

PVT, not reported whether it was acute or chronic |

Cirrhosis: 100

Malignancy: HCC I: 30; C: 63

|

Edoxaban*

mean duration: 6 months |

VKA*

mean duration: 6 months |

6 months |

|

Naymagon (2020), retrospective |

N=330, of which N=57 not using AC (I 93, C1 108, C2 70)

Age: I: 47.1 (15.2); C1: 50.4 (14.8); C2: 51.4 (16.9)

Sex (M): I: 50.5; C1: 52.8; C2: 38.6 |

PVT, acute |

Cirrhosis: 0

Malignancy: Non-HCC malignancy I: 5.4; C1: 1.9; C2: 14.3 |

Apixaban, Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban

At least for 3 months |

VKA (C1), LMWH (C2), Fondaparinux**, no AC**

At least for 3 months |

I: 28.1 ± 11.3 months C1: 55.8 ± 27.4 months C2: 33.0 ± 18.9 months |

|

Ilcewicz (2021), retrospective |

N=33 (I:13, C: 20)

Age: I: 60 ± 18; C: 51 ± 12

Sex (M) I: 69; C: 75 |

New PVT |

Cirrhosis: Previous diagnosis of cirrhosis I:38; C: 25

Malignancy: NR |

Apixaban, rivaroxaban

mean duration: 3 months |

VKA

mean duration: 3 months |

90 days |

|

Kawata (2021), retrospective |

N=136 (I: 43, C: 93)

Age: I: 59±15; C: 55±15

Sex (M): I: 64; C: 59 |

New episode of SVT |

Cirrhosis: 19.4

Malignancy: Abdominal malignancy 31 |

Apixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban

mean duration: 483 (359 –606) days |

VKA/LMWH/no AC**

mean duration: 483 (359 – 606) days |

6 (3-10) months for thrombotic outcomes and 9 (4-15) months for bleeding outcomes |

|

Naymagon (2021), retrospective |

N=214, of which N=86 using AC

Age:**** 60 (54–67)

Sex (M): **** 60.5 |

Acute PVT |

Cirrhosis: 100

Malignancy: Concurrent HCC: 15.1 |

Rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran

median duration of AC: 18.8 (10.8–52.8) months

|

Warfarin/ enoxaparin/no AC**

median duration of AC: 18.8 (10.8–52.8) months |

NR

Median of 21 (11–44) months for patients using AC |

|

Naymagon (2021_B) retrospective |

N=63,of which N=58 using AC

Age (median (IQR)): I: 42 (29-53); C1: 43 (33-54); C2: 44 (32-53)

Sex (M): I: 73.9; C1: 46.2; C2: 63.6 |

Acute PVT and IBD |

Cirrhosis: 6

Malignancy: NR |

Rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran

median duration 3.9 (2.7-6.1) months

|

Warfarin (C1), enoxaparin (C2)/no AC**

median duration of warfarin 8.5 (3.9-NA) months, for enoxaparin not reported |

I: 12 (6-35) months C1: 43 (9-80) months C2: 23 (10-58) months |

|

Zhang (2023), retrospective |

N=77 of which N=27 using AC

Age: 60.4 ± 12.3***

Sex (M): 67***

|

PVT, not reported whether it was acute or chronic |

Cirrhosis: 100

Malignancy: HCC 7 |

DOAC

Median duration of AC: 6 (2-11) months |

Warfarin

Median duration of AC: 6 (2-11) months |

NR

Median of 28.5 months for patients using AC |

*All patients were first treated with danaparoid sodium and Anthrobin P for 3 days at 1500 units/day i.v. in those patients whose antithrombin III activity decreased by less than 70%. ** Not included in our literature analysis. ***Age and sex are not reported by AC used but only for the total group patients receiving anticoagulants.

Results are reported as % (sex, cirrhosis and malignancy) or as mean ± SD/Median (IQR, age). DOAC: direct oral anticoagulants; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; LMWH: low-molecular weight heparin; M: Male; NR: not reported; PVT: Portal vein thrombosis; VKA: vitamin K antagonist

Results

Since part of the studies compared data on treatment with DOAC versus VKA, and on DOAC versus LMWH, it was decided to present the data on those comparisons separately.

Major bleeding

Valeriani (2021), Ilcewicz (2021), Kawata (2021), Naymagon (2021) and Zhang (2023) reported on major bleeding, which was defined as a fatal and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, bleeding leading to a reduction of 2 g/dl or more in hemoglobin concentration or necessitating transfusion of two or more blood units (according to ISTH criteria). Valeriani (2021) included only data of Nagaoki (2018).

Besides, Naymagon (2020) and Naymagon (2021_B) reported on major bleeding, which was however defined as GRADE 3 or 4 according to WHO criteria. We decided not to include these data in the pooled data analysis, but report them separately.

Total group

DOAC vs VKA

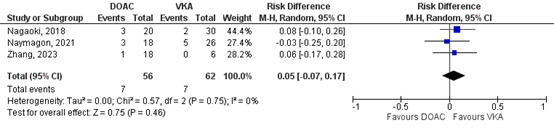

Nagaoki (2018), Ilcewicz (2021), Naymagon (2021) and Zhang (2023) reported on major bleeding, for the comparison DOAC versus VKA. In total for 7/69 (10.1%) patients a major bleeding was reported in the DOAC group, compared to 8/82 (9.8%) patients in the VKA group (Figure 1). This corresponds to a risk ratio (RR, 95%CI) of 1.13 (0.44 to 2.86), which is in favor of the VKA group. Corresponding risk difference (RD, 95%CI) is 0.01 (-0.09 to 0.10), which is not considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 1: Forest plot for the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure major bleeding (according to ISTH criteria) in patients with acute splanchnic vein thrombosis, compared to VKA.

Naymagon (2020) and Naymagon (2021_B) reported that in respectively 2/93 (2.2%) and 0/18 (0%) of the patients in the DOAC group major bleeding was reported, compared to 26/108 (24.1) and 3/22 (13.6%) patients in the VKA group. This corresponds to RRs (95%CI) of respectively 0.09 (0.02 to 0.37) and 0.17 (0.01 to 3.14) which are in favor of the DOAC groups. Corresponding RDs (95%CI) are -0.22 (-0.31 to -0.13) and -0.20 (-0.28 to -0.13), which is considered clinically relevant.

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2021) reported on major bleeding for the comparison DOAC versus LMWH. In the DOAC group, for 3/18 (16.7%) patients major bleeding was reported, compared to 9/42 (21.4%) patients in the LMWH group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 0.78 (0.24 to 2.54) which is in favor of the DOAC group. Corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.05 (-0.26 to 0.16), which is considered clinically relevant.

Naymagon (2020) and Naymagon (2021_B) reported that in respectively 2/93 (2.2%) and 0/18 (0%) of the patients in the DOAC group major bleeding was reported, compared to 10/70 (14.3%) and 1/13 (7.7%) patients in the LMWH group. This corresponds to RRs (95%CI) of respectively 0.15 (0.03 to 0.67) and 0.25 (0.01 to 5.59) which are in favor of the DOAC group. Corresponding RDs (95%CI) are -0.26 (-0.37 to -0.15) and -0.08 (-0.25 to 0.10) which are considered clinically relevant.

DOAC vs LMWH/VKA

Kawata (2021) did not differentiate between patients receiving LMWH or VKA. They reported major bleeding in 3/47 (6.4%) patients in the DOAC group, compared to 6/98 (6.1%) patients in the LMWH/VKA group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 1.04 (0.27 to 3.99), which is in favor of the LMWH/VKA group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is 0.00 (-0.08 to 0.09), which is not considered to be clinically relevant.

Patients with cirrhosis

DOAC vs VKA

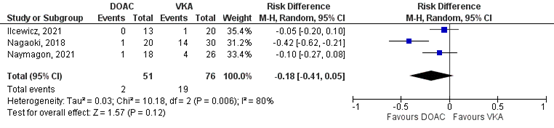

Nagaoki (2018), Naymagon (2021) and Zhang (2023) reported on major bleeding in patients with cirrhosis for the comparison between DOAC versus VKA. In total, for 7/56 (12.5%) patients, major bleeding was reported in the DOAC group, compared to 7/62 (11.3%) patients in the VKA group (Figure 2). This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 1.22 (0.46 to 3.24) which is in favor of the VKA group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is 0.05 (-0.07 to 0.17), which is considered clinically relevant.

Besides, Ilcewicz (2021) reported that for none of the 10 patients with a previous diagnosis of cirrhosis a bleeding event was reported.

Figure 2: Forest plot for the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure major bleeding (according to ISTH criteria) in patients with acute splanchnic vein thrombosis and cirrhosis, compared to VKA.

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2021) reported on the outcome measure major bleeding in patients with cirrhosis for the comparison between DOAC versus LMWH – see also the results for the total group: in the DOAC group, for 3/18 (16.7%) patients a major bleeding was reported, compared to 9/42 (21.4%) patients in the LMWH group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 0.78 (0.24 to 2.54) which is in favor of the DOAC group. Corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.05 (-0.26 to 0.16), which is considered clinically relevant.

Patients without cirrhosis

Naymagon (2020) reported on major bleeding in patients without cirrhosis, which was defined as GRADE 3 or 4 according to the WHO criteria. Data are reported here, but not used to draw conclusions on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure major bleeding in patients without cirrhosis, compared to either VKA or LMWH.

DOAC vs VKA

Naymagon (2020) reported on major bleeding in patients without cirrhosis for the comparison DOAC versus VKA. For 2/93 (2.2%) of the patients in the DOAC group major bleeding was reported, compared to 26/108 (24.1%) patients in the VKA group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 0.09 (0.02 to 0.37), which is in favor of the DOAC group. Corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.22 (-0.31 to -0.13), which is considered clinically relevant.

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2020) reported on major bleeding in patients without cirrhosis for the comparison DOAC versus LMWH. For 2/93 (2.2%) in the DOAC group major bleeding was reported, compared to 10/70 (14.3%) patients in the LMWH group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 0.15 (0.03 to 0.67) which is in favor of the DOAC group. Corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.12 (-0.21 to -0.03), which is considered clinically relevant.

Progression of SVT

Valeriani (2021), Ilcewicz (2021), Kawata (2021) and Naymagon (2021) reported on progression of SVT which was respectively defined as progression of SVT at follow-up imaging (Valeriani, 2021), extension into previously uninvolved vessels or increase in the length/volume of the clot in the same vessel on imaging at 3, 6, and between 6 and 24 months, with a minimum observation period of 6 months (Kawata, 2021), PVT extension (Naymagon, 2021) or not defined (Ilcewicz, 2021). Valeriani (2021) included data of Nagaoki (2018).

Total group

DOAC vs VKA

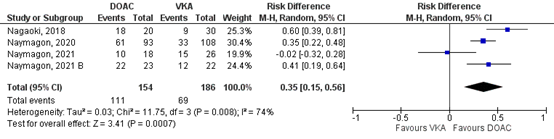

Nagaoki (2018), Ilcewicz (2021) and Naymagon (2021) reported on progression SVT for the comparison DOAC vs VKA. In total, for 2/51 (3.9%) of the patients in the DOAC group was progression of SVT reported, compared to 19/76 (25%) patients in the VKA-group (Figure 4). This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 0.22 (0.06 to 0.82), which is in favor of the DOAC group. Corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.18 (-0.41 to 0.05), which is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3: Forest plot for the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure progression of SVT in patients with acute splanchnic vein thrombosis, compared to VKA.

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2021) reported on progression of SVT for the comparison DOAC vs LMWH. For one of the patients in the DOAC group (N=18) progression of SVT was reported, compared to 8/42 (19.0%) patients in the LMWH group. The corresponding RR (95%CI) is 0.29 (0.04 to 2.16), which is in favor of the DOAC group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.13 (-0.29 to 0.02), which is considered clinically relevant.

DOAC vs LMWH/VKA

Kawata (2021) did not differentiate between patients receiving LMWH or VKA. In total for 3/43 (7.0%) patients, progression of SVT was reported in the DOAC group, compared to 5/93 (5.4%) patients in the LMWH/VKA group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 1.16 (0.29 to 4.62), which is in favor of the LMWH/VKA group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is 0.01 (-0.08 to 0.10), which is not considered clinically relevant.

Patients with cirrhosis

DOAC vs VKA

Nagaoki (2018), Ilcewicz (2021) and Naymagon (2021) reported on progression of SVT for the comparison DOAC versus VKA in patients with cirrhosis. As is depicted in Figure 3, RDs (95%CI) based on data of Nagaoki (2018) and Naymagon (2021) are respectively -0.42 (-0.62 to -0.21) and -0.10 (-0.27 to 0.08), which are in favor of the DOAC group and are not considered clinically relevant. Finally, Ilcewicz (2021) reported that in none of the 10 patients with previous diagnosis of cirrhosis progression of SVT was found.

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2021) reported on progression of SVT for the comparison DOAC vs LMWH in patients with cirrhosis – see also results for the total group: for one of the patients in the DOAC group (N=18) progression of SVT was reported, compared to 8/42 (19.0%) patients in the LMWH group. The corresponding RR (95%CI) is 0.29 (0.04 to 2.16), which is in favor of the DOAC group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.13 (-0.29 to 0.02), which is considered clinically relevant.

Patients without cirrhosis

None of the included studies reported on progression of SVT for patients without cirrhosis.

(partial) Resolution of SVT

Valeriani (2021), Kawata (2021), Naymagon (2020), Naymagon (2021-B), Naymagon (2021) and Zhang (2023) reported on (partial) resolution of SVT which was respectively defined as:

- any grade of recanalization (partial or complete) at follow-up imaging (Valeriani, 2021);

- either complete resolution (no evidence of thrombus in subsequent imaging) or partial resolution (objective reduction in the number of vessels involved or the length of the clot), on imaging at three, six, and between six and 24 months, with a minimum observation period of six months (Kawata, 2021);

- complete radiographic resolution of PVT established on follow-up imaging (Naymagon, 2020; Naymagon, 2021 and Naymagon, 2021_B);

- partial (> 50% reduction of the thrombus) or complete (complete disappearance of the thrombus) PVT recanalization (Zhang, 2023).

Valeriani (2021) included data of Nagaoki (2018).

Total group

DOAC vs VKA

Nagaoki (2021), Naymagon (2020), Naymagon (2021), Naymagon (2021_B) and Zhang (2023) reported on (partial) resolution of SVT for the comparison DOAC vs VKA. In total, for 111/154 (72.1%) of the patients in the DOAC-group was complete resolution of SVT reported, compared to 69/186 (37.7%) patients in the VKA-group (Figure 4). This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 5.18 (1.49 to 18.09), which is in favor of the DOAC-group. Corresponding RD (95%CI) is 0.35 (0.15 to 0.56), which is considered clinically relevant.

Zhang (2023) reported on partial or complete SVT recanalization. However, number of events was not reported. Therefore, these data could not be included in the pooled analysis. Hazard ratio (95%CI) was 4.05 (0.5 to 37.7), which is in favor of the DOAC-group and is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 4: Forest plot for the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT in patients with acute splanchnic vein thrombosis, compared to VKA.

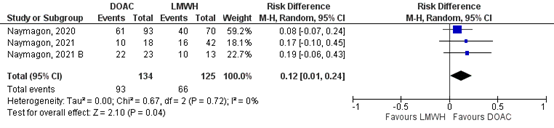

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2020), Naymagon (2021), Naymagon (2021_B) reported on (partial) resolution of SVT for the comparison DOAC vs LMWH. In total, for 93/134 (69.4%) of the patients in the DOAC group was complete resolution of SVT reported, compared to 66/125 (52.8%) patients in the VKA-group (Figure 5). This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 1.21 (1.01 to 1.46), which is in favor of the DOAC-group. Corresponding RD (95%CI) is 0.12 (0.01 to 0.24), which is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 5: Forest plot for the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT in patients with acute splanchnic vein thrombosis, compared to LMWH.

DOAC vs LMWH/VKA

Kawata (2021) did not differentiate between patients receiving LMWH or VKA. In total, for 25/43 (58.1%) patients (partial) resolution of SVT was reported in the DOAC-group, compared to 54/83 (65.1%) patients in the LMWH/VKA-group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 0.89 (0.66 to 1.20), which is in favor of the LMWH/VKA-group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.07 (-0.25 to 0.11), which is considered clinically relevant.

Patients with cirrhosis

DOAC vs VKA

Nagaoki (2021), Naymagon (2021) and Zhang (2023) reported on (partial) resolution of SVT for the comparison DOAC vs VKA. Zhang (2023) did not report the number of events, so results could not be pooled and are reported in Table 2. Results are inconsistent, since Nagaoki (2021) and Zhang (2023) reported results in favor of the DOAC-group while Naymagon (2021) reported a non-clinically relevant difference in favor of the VKA-group.

Table 2: Results on the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT in patients with acute splanchnic vein thrombosis and cirrhosis, compared to VKA.

|

Study |

DOAC-group (n/N (%)) |

VKA-group (n/N (%)) |

Effect estimate (95%CI) |

|

Nagaoki (2021) |

18/20 (90) |

9/30 (30) |

RD: 0.60 (0.39 to 0.81) RR: 3.00 (1.70 to 5.28) |

|

Naymagon (2021) |

10/18 (55.6) |

15/26 (57.7) |

RD: -0.02 (-0.32 to 0.28) RR: 0.96 (0.57 to 1.63) |

|

Zhang (2023) |

NR |

NR |

HR: 4.045 (0.52 to 37.67) |

RD: Risk difference, RR: risk ratio, HR: Hazard ratio, DOAC: direct oral anticoagulants, NR: not reported, VKA: vitamin K antagonists

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2021) reported on (partial) resolution of SVT for the comparison DOAC vs LMWH. For 10/18 (55.6%) patients (partial) resolution of SVT was reported in the DOAC-group, compared to 16/42 (0.4%) patients in the LMWH/VKA-group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 1.46 (0.83 to 2.57), which is in favor of the DOAC-group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is 0.17 (-0.10 to 0.45), which is considered clinically relevant.

Patients without cirrhosis

DOAC vs VKA

Naymagon (2020) and Naymagon (2021_B) reported on (partial) resolution of SVT for the comparison DOAC vs VKA. Results are reported in Table 3. Differences are in favor of the DOAC-group and are considered clinically relevant.

Table 3: Results on the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT in patients with acute splanchnic vein thrombosis without cirrhosis, compared to VKA.

|

Study |

DOAC-group (n/N (%)) |

VKA-group (n/N (%)) |

Effect estimate (95%CI) |

|

Naymagon (2020) |

61/93 (65.6) |

33/108 (30.6) |

RD: 0.35 (0.22 to 0.48) RR: 2.15 (1.56 to 2.96) |

|

Naymagon (2021_B) |

22/23 (95.7) |

12/22 (54.5) |

RD: 0.41 (0.19 to 0.64) RR: 1.75 (1.19 to 2.59) |

RD: Risk difference, RR: risk ratio, DOAC: direct oral anticoagulants, VKA: vitamin K antagonist

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2020) and Naymagon (2021_B) reported on (partial) resolution of SVT for the comparison DOAC vs LMWH. Results are reported in Table 4. Differences are in favor of the DOAC-group and are considered clinically relevant.

Table 4: Results on the effect of DOACs on the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT in patients with acute splanchnic vein thrombosis without cirrhosis, compared to LMWH.

|

Study |

DOAC-group (n/N (%)) |

LMWH-group (n/N (%)) |

Effect estimate (95%CI) |

|

Naymagon (2020) |

61/93 (65.6) |

40/70 (57.1) |

RD: 0.08 (-0.07 to 0.24) RR: 1.15 (0.89 to 1.47) |

|

Naymagon (2021_B) |

22/23 (95.7) |

10/13 (76.9) |

RD: 0.19 (-0.06 to 0.43) RR: 1.24 (0.91 to 1.70) |

RD: Risk difference, RR: risk ratio, DOAC: direct oral anticoagulants, LMWH: low molecular weight heparin

Mortality

Naymagon (2020), Naymagon (2021) and Naymagon (2021_B) reported on mortality, which was not further defined.

Total group

DOAC vs VKA

Naymagon (2021) reported on mortality for the comparison DOAC versus VKA. In the DOAC group, 3/18 (16.7%) of the patients died, compared to 4/26 (15.4%) in the warfarin group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 1.08 (0.28 to 4.27), which is in favor of the VKA group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is 0.01 (-0.21 to 0.23) which is not considered clinically relevant.

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2021) reported on mortality for the comparison DOAC versus LMWH. In the DOAC group, 3/18 (16.7%) of the patients died, compared to 8/42 (19.1%) in respectively the warfarin and enoxaparin group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 0.88 (0.26 to 2.92), which is in favor of the DOAC group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.02 (-0.23 to 0.19) which is not considered clinically relevant.

Naymagon (2020) and Naymagon (2021_B) reported also on mortality, but data was very limited. Naymagon (2020) reported that 12/330 (3.6%) patients died, of which three were related to PVT (enoxaparin group: N=1/70, warfarin group: N=1/108, DOAC group: N=0/93). Naymagon (2021_B) reported that 2/58 patients died during follow-up, of which one was related to PVT (warfarin group: N=1/22, enoxaparin group: N=0/13 and DOAC group: N=0/23). Since data is too limited, it cannot be used to draw conclusions on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure mortality in patients with SVT, compared to conventional anticoagulation.

Patients with cirrhosis

DOAC vs VKA

Naymagon (2021) reported on mortality for the comparison DOAC versus VKA in patients with cirrhosis – see also results on the total group: in the DOAC group, 3/18 (16.7%) of the patients died, compared to 4/26 (15.4%) in the warfarin group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 1.08 (0.28 to 4.27), which is in favor of the VKA group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is 0.01 (-0.21 to 0.23) which is not considered clinically relevant.

DOAC vs LMWH

Naymagon (2021) reported on mortality for the comparison DOAC vs LMWH – see also results on the total group: in the DOAC group, 3/18 (16.7%) of the patients died, compared to 8/42 (19.1%) in respectively the warfarin and enoxaparin group. This corresponds to a RR (95%CI) of 0.88 (0.26 to 2.92), which is in favor of the DOAC group. The corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.02 (-0.23 to 0.19) which is not considered clinically relevant.

Patients without cirrhosis

Naymagon (2020) reported on mortality in patients without cirrhosis – see also results on the total group: they reported that 12/330 (3.6%) patients died, of which three were related to PVT (enoxaparin group: N=1/70, warfarin group: N=1/108, DOAC group: N=0/93). Results are too limited to draw conclusions.

Clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNMB)

Kawata (2021) reported on CRNMB, which was defined according to the criteria of ISTH.

Total group – DOAC versus LMWH/VKA

Kawata (2021) reported on CRNMB for the comparison DOAC versus LMWH/VKA. In the DOAC group, for 1/47 (2%) patients a CRNMB was reported, compared to 4/98 (4%) patients in the LMWH/VKA group. This corresponds to an RR (95%CI) of 0.52 (0.06 to 4.54), which is in favor of the DOAC group. Corresponding RD (95%CI) is -0.02 (-0.08 to 0.04). This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Patients with cirrhosis

None of the included studies reported on CRNMB for patients with SVT and cirrhosis.

Patients without cirrhosis

None of the included studies reported on CRNMB for patients with SVT, without cirrhosis.

Recurrent VTE

Ilcewicz (2021) reported on recurrent thrombo-embolic events, which was defined as VTE of typical locations, including peripheral deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, new or worsened index PVT, and other atypical VTE. We considered data on worsening of PVT in the systematic analysis for the outcome measure progression of SVT.

Total group

DOAC vs VKA

Ilcewicz (2021) reported on recurrent thrombo-embolic events. In the DOAC group for none of the 13 patients a recurrent thrombo-embolic was reported, compared to 3/20 (15%) patients in the warfarin group. For all of them a new SVT was reported.

All comparisons

Naymagon (2020) reported that recurrence of SVT was not associated with type of anticoagulants and occurred in 9 of all included 330 patients (2.7%, patients without receiving anticoagulants were also included in this group, and effect measure was not reported). Data was too limited and was therefore not used to draw conclusions on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure recurrent VTE in patients with SVT, compared to conventional anticoagulation.

Patients with cirrhosis

Ilcewicz (2021) reported that in none of the 10 patients with cirrhosis a recurrent VTE was found. Therefore, data is too limited to draw conclusions.

Patients without cirrhosis

Naymagon (2020) reported on recurrence of SVT in patients without cirrhosis – see also results for the total group. In short, they reported that recurrence of SVT was not associated with type of anticoagulants and occurred in 9 of all included 330 patients (2.7%, patients without receiving anticoagulants were also included in this group, and effect measure was not reported).

Liver failure and liver transplantation

None of the included studies reported on liver failure and liver transplantation.

Need for surgical or radiological intervention

Total group

None of the included studies reported on need for surgical or radiological intervention by the different anticoagulation groups. However, Naymagon (2021-B) reported that three of the patients who developed symptomatic portal hypertension (SPH) received a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (enoxaparin-group: N=2/13, warfarin group: N=1/22, DOAC group: N=0/23). Besides, Naymagon (2020) reported that 24/104 (23%) of the patients developing chronic SPH received a TIPS. They concluded that this was not significantly different between the groups (including also the non-anticoagulants group). Data was too limited and was therefore not used to draw conclusions on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure need for surgical or radiological intervention in patients with SVT, compared to conventional anticoagulation.

Patients with cirrhosis

None of the included studies reported on need for surgical or radiological intervention for patients with cirrhosis.

Patients without cirrhosis

Naymagon (2020) reported on patients without cirrhosis who developed chronic SPH and received a TIPS – see also results for the total group. In short, they reported that 24/104 (23%) of the patients developing chronic SPH received a TIPS. They concluded that this was not significantly different between the groups (including also the non-anticoagulants group).

Level of evidence of the literature

General remarks

In part of the studies, it was not specified whether patients with acute and/or chronic SVT were included (Nagaoki, 2018 and Zhang, 2023).

Major bleeding

All comparisons

The evidence regarding the outcome measure major bleeding (according to ISTH criteria) came from observational studies and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the studies (e.g. events might have been missed due to retrospective design of the study, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (serious imprecision, downgraded 2 levels).

Patients without cirrhosis

None of the included studies reported on major bleeding (according to ISTH criteria) for patients without cirrhosis.

Progression of SVT

Total group (DOAC vs LMWH)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure progression of SVT came from observational studies and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the studies (e.g. progression might have been missed since there was no routine imaging/imaging was not standardized, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed one of the thresholds for clinical relevance (serious imprecision, downgraded 1 level).

Total group (DOAC vs VKA), patients with cirrhosis (DOAC vs VKA and DOAC vs LMWH)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure progression of SVT came from observational studies and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the studies (e.g. progression might have been missed since it was not sure whether there was routine imaging, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (serious imprecision, downgraded 2 levels).

Patients without cirrhosis

None of the included studies reported on progression of SVT for patients without cirrhosis.

(partial) resolution of SVT

Total group (DOAC vs VKA) and patients without cirrhosis (DOAC vs VKA)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure progression of SVT came from observational studies and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the studies (e.g. (partial) resolution of SVT might have been missed since it was not sure whether there was routine imaging, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, number of included patients was low (imprecision, downgraded 1 level).

Total group (DOAC vs LMWH)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT came from observational studies and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the studies (e.g. (partial) resolution might have been missed since there was no routine imaging/imaging was not standardized, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed one of the thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded 1 level).

Patients with cirrhosis (DOAC vs VKA)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT came from observational studies and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the studies (e.g. (partial) resolution might have been missed since there was no routine imaging/imaging was not standardized, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, results were inconsistent (inconsistency, downgraded 1 level) and the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded 1 level).

Patients with cirrhosis (DOAC vs LMWH) and patients without cirrhosis (DOAC vs LMWH)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure (partial) resolution of SVT came from observational studies and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the study (e.g. (partial) resolution might have been missed since there was no routine imaging/imaging was not standardized, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded 2 levels).

Mortality

Total group (DOAC vs VKA and DOAC vs LMWH) and patients with cirrhosis (DOAC vs VKA and DOAC vs LMWH)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure mortality came from observational studies and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the studies (e.g. risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups, patients with short follow-up were excluded and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (serious imprecision, downgraded 2 levels).

Patients without cirrhosis

Data was too limited and could therefore not be used to draw conclusions on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure recurrent mortality in patients with SVT without cirrhosis, compared to conventional anticoagulation.

Clinically relevant non major bleeding

Total group (DOAC vs VKA or LMWH)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure clinically relevant non major bleeding came from an observational study and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the studies (e.g. events might have been missed due to retrospective design of the study, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the thresholds for clinical relevance (serious imprecision, downgraded 2 levels).

Total group (DOAC vs VKA and DOAC vs LMWH), patients with cirrhosis and patients without cirrhosis

None of the included studies reported on CRNMB for patients with or without cirrhosis, nor for the comparisons between DOAC and VKA or DOAC and LMWH for the total group.

Recurrent VTE

Total group (DOAC vs VKA)

The evidence regarding the outcome measure recurrent VTE came from an observational study and therefore the level of evidence started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias in the study (e.g. recurrent VTE’s might have been missed since there was no routine imaging, risk on indication bias, time frame differed between the groups and risk on (residual) confounding, downgraded 2 levels). Besides, the number of events (and patients) was very low (serious imprecision, downgraded 2 levels).

Total group (DOAC vs LMWH) and patients with cirrhosis

None of the included studies reported on recurrent VTE for patients with cirrhosis nor for the comparison between DOAC and LMWH.

Patients without cirrhosis

Data was too limited and could therefore not be used to draw conclusions on the effect of DOAC on the outcome measure recurrent VTE in patients with SVT without cirrhosis, compared to conventional anticoagulation.

Liver failure, liver transplantation and clinically relevant non major bleeding

None of the included studies reported on liver failure and liver transplantation. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of DOACs on the outcome measures liver failure and liver transplantation in adults with SVT.

Need for surgical or radiological intervention

Data was too limited and could therefore not be used to draw conclusions on the effect of DOAC on need for surgical or radiological intervention in patients with SVT, compared to conventional anticoagulation.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: what are the (un)desirable effects of treatment with Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOAC) in adult patients with acute SVT, compared to treatment with low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH), vitamin K antagonist (VKA) or heparin?

| P (Patients): | adult patients with acute SVT (acute portal vein thrombosis, acute Budd Chiari syndrome, acute hepatic vein thrombosis, acute splenic vein thrombosis, acute SVT, acute mesenteric vein thrombosis) |

| I (Intervention): | DOAC |

| C (Comparison): | LMWH, VKA, heparin |

| O (Outcomes): | major bleeding, clinically relevant non major bleeding (CRNMB), mortality, recurrent VTE, progression of SVT, (partial) resolution of SVT, liver failure, liver transplantation, need for surgical or radiological intervention |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered major bleeding, progression of SVT, (partial) resolution of SVT and mortality as critical outcome measures for decision making; CRNMB, recurrent venous thromboembolic event (VTE), liver failure, liver transplantation and need for surgical or radiological intervention as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Major bleeding: fatal bleeding, and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular or pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome, and/or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin levels of 1.24 mmol/L (20 g/L or greater) or more, or leading to a transfusion of 2 U or more of whole blood or red cells, as defined by International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis;

- Recurrent VTE: objectively confirmed VTE, including recurrent SVT;

- Need for surgical or radiological intervention: Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS), thrombosuction, bowel resection.

A priori, the working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a risk difference of 3%* as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for major bleeding, progression of SVT, (partial) resolution of SVT, mortality, clinically relevant non major bleeding and recurrent VTE. For all other outcome measures, the default thresholds proposed by the international GRADE working group were used as a threshold for clinically relevant differences: a 25% difference in relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes (RR< 0.8 or RR> 1.25), and 0.5 standard deviations (SD) for continuous outcomes.

Since presence of liver cirrhosis is an important underlying cause for SVT and factor in deciding on type of anticoagulants for the treatment of patients with SVT, subgroup analysis will be performed for patients with liver cirrhosis and patients without liver cirrhosis.

*Based on the differences applied in the guidelines on thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. This working group derived the minimal clinically (patient) important differences from the ACCP (2012).

Search and select (Methods)

Two literature searches were performed. At first, we searched for systematic reviews and RCT and after this we performed an additional search to supplement the selected review(s) with observational studies that were published after the search date of the selected review(s).

Search 1: Systematic reviews (SR) and RCTs

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until July 5th, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 669 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: (systematic reviews of) RCTs and observational studies which evaluated the effectiveness of DOAC in adult patients with acute SVT, compared to treatment with heparin, LMWH or VKA. 37 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 36 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and only one study was included (Valeriani, 2021).

Search 2: Observational studies

The search strategy of the systematic review (Valeriani, 2021) was completed on December 19th, 2019. Therefore, we performed an additional search on observational studies in the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) with relevant search terms between 1st of January 2019 until the 30th of October 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 553 hits. Studies were selected based on following criteria: observational studies which compared the effectiveness of DOAC in adult patients with acute SVT. The following studies were excluded:

- Switch over studies in which patients that switched from (long-term) conventional anticoagulants to DOACs are considered as patients in the DOAC group.

- Studies that primarily included patients with chronic SVT.

- Studies that primarily included patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and SVT, because characteristics/treatment options/prognosis of those patients differ significantly from other patients with acute SVT.

In selection of the studies, it seemed difficult to select the studies that only included patients with an acute SVT. In the study of Khan (2022) 43% of the patients had a chronic SVT. This study was excluded. However, in other studies it was not specified whether patients with acute and/or chronic SVT were included (Nagaoki, 2018 and Zhang, 2023). The working group decided to include those studies in the literature analysis, as in clinical practice it is also often not known if an SVT is acute or of older age. It is however important to take this into account in interpreting the results.

18 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 12 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and six studies were included.

In total, 1 SR (search 1) and six observational studies (search 2) were included.

Results

Seven studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Ageno W, Beyer Westendorf J, Contino L, Bucherini E, Sartori MT, Senzolo M, Grandone E, Santoro R, Carrier M, Delluc A, De Stefano V, Pomero F, Donadini MP, Tosetto A, Becattini C, Martinelli I, Nardo B, Bertoletti L, Di Nisio M, Lazo-Langner A, Schenone A, Riva N. Rivaroxaban for the treatment of noncirrhotic splanchnic vein thrombosis: an interventional prospective cohort study. Blood Adv. 2022 Jun 28;6(12):3569-3578. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007397. PMID: 35439303; PMCID: PMC9631568.

- Candeloro M, Valeriani E, Monreal M, Ageno W, Riva N, Lopez-Reyes R, Peris ML, Beyer Westendorf J, Schulman S, Rosa V, López-Núñez JJ, Garcia-Pagan JC, Magaz M, Senzolo M, De Gottardi A, Di Nisio M. Anticoagulant therapy for splanchnic vein thrombosis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2022 Aug 9;6(15):4516-4523. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007961. PMID: 35613465; PMCID: PMC9636325.

- Carlin S, Cuker A, Gatt A, Gendron N, Hernández-Gea V, Meijer K, Siegal DM, Stanworth S, Lisman T, Roberts LN. Anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and treatment of venous thromboembolism and portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2024 Sep;22(9):2653-2669. doi: 10.1016/j.jtha.2024.05.023. Epub 2024 May 31. PMID: 38823454.

- Van Dijk CE, Heim N and Witteveen J. Evaluatie van de ervaringen en kosten van antistollingszorg. Zorginstituut Nederland. 2020. https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publicaties/rapport/2020/10/20/evaluatie-antistollingszorg

- de Franchis R, Bosch J, Garcia-Tsao G, Reiberger T, Ripoll C; Baveno VII Faculty. Baveno VII - Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2022 Apr;76(4):959-974. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.12.022. Epub 2021 Dec 30. Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2022 Apr 14;: PMID: 35120736; PMCID: PMC11090185.

- Hutchinson A, Rees S, Young A, Maraveyas A, Date K, Johnson MJ. Oral anticoagulation is preferable to injected, but only if it is safe and effective: An interview study of patient and carer experience of oral and injected anticoagulant therapy for cancer-associated thrombosis in the select-d trial. Palliat Med. 2019 May;33(5):510-517. doi: 10.1177/0269216318815377. Epub 2018 Nov 29. PMID: 30488789; PMCID: PMC6506899.

- Ilcewicz HN, Martello JL, Piechowski K. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of portal vein thrombosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun 1;33(6):911-916. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001958. PMID: 33079786; PMCID: PMC8371984.

- Kawata E, Siew DA, Payne JG, Louzada M, Kovacs MJ, Lazo-Langner A. Splanchnic vein thrombosis: Clinical manifestations, risk factors, management, and outcomes. Thromb Res. 2021 Jun;202:90-95. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.03.018. Epub 2021 Mar 21. PMID: 33798804.

- Nagaoki Y, Aikata H, Daijyo K, Teraoka Y, Shinohara F, Nakamura Y, Hatooka M, Morio K, Nakahara T, Kawaoka T, Tsuge M, Hiramatsu A, Imamura M, Kawakami Y, Ochi H, Chayama K. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban for treatment of portal vein thrombosis following danaparoid sodium in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2018 Jan;48(1):51-58. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12895. Epub 2017 Apr 27. PMID: 28342265.

- Naymagon L, Tremblay D, Zubizarreta N, Moshier E, Troy K, Schiano T, Mascarenhas J. The efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in noncirrhotic portal vein thrombosis. Blood Adv. 2020 Feb 25;4(4):655-666. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001310. PMID: 32078681; PMCID: PMC7042983.

- Naymagon L, Tremblay D, Zubizarreta N, Moshier E, Mascarenhas J, Schiano T. Safety, Efficacy, and Long-Term Outcomes of Anticoagulation in Cirrhotic Portal Vein Thrombosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 Oct;66(10):3619-3629. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06695-4. Epub 2020 Nov 5. PMID: 33151401.

- Naymagon L_B, Tremblay D, Zubizarreta N, Moshier E, Naymagon S, Mascarenhas J, Schiano T. The Natural History, Treatments, and Outcomes of Portal Vein Thrombosis in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 Jan 19;27(2):215-223. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa053. PMID: 32185400; PMCID: PMC8427727.

- Valeriani E, Di Nisio M, Riva N, Cohen O, Garcia-Pagan JC, Magaz M, Porreca E, Ageno W. Anticoagulant therapy for splanchnic vein thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2021 Mar 4;137(9):1233-1240. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006827. PMID: 32911539.

- Valeriani E, Di Nisio M, Riva N, Cohen O, Porreca E, Senzolo M, De Gottardi A, Magaz M, Garcia-Pagan JC, Ageno W. Anticoagulant Treatment for Splanchnic Vein Thrombosis in Liver Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2021 Jul;121(7):867-876. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1722192. Epub 2021 Feb 1. PMID: 33525037.

- Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Li D, Guo M, Li H, Liu R, Cui X. Safety, efficacy and prognosis of anticoagulant therapy for portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: a retrospective cohort study. Thromb J. 2023 Jan 30;21(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12959-023-00454-x. PMID: 36717831; PMCID: PMC9885579.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What are the (un)desirable effects of treatment with Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOAC) in adult patients with acute abdominal vein thrombosis, compared to treatment with low-molecular weight heparine (LMWH), vitamin K antagonist (VKA) or heparin?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Valeriani, 2021

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs/ cohort studies.

Literature search up to December, 2019

A: Hanafy (2018)* B: Nagaoki (2018) C: Sharma (2020)** D: Wille (2019)***

*Retracted article and therefore not considered in this literature review. **Part of the patients switched from VKA to DOACs and were considered in the DOAC-group. Study is excluded. ***Data on DOACs is to limited and therefore this study is not considered in this literature review.

Study design: Retrospective studies

Setting and Country: B: University hospital, Japan C: Tertiary centre, India

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: B: No funding declared, no COI C: None

Systematic review was not funded. However, publication costs of article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. |

Inclusion criteria SR: diagnosis of SVT; observational study or RCT including ≥10 patients; availability of radiological or clinical outcomes; and anticoagulant treatment with LMWH, unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux, VKAs, DOACs or no anticoagulant therapy.

Exclusion criteria SR: study design different from those specified in the inclusion criteria; inclusion of < 10 patients; and anticoagulant therapy different from those specified in the inclusion criteria.

97 studies included of which 4 studies on DOACs.

Important patient characteristics at baseline:*

N B: I: 20, C: 30) C: I: 36, C:62

Age B: I: 69 (53-74) C: 67 (24-83) C: I:29.5 (22–35) C: 28 (23–37)

Sex (male): B: I: 65%, C: 57% C: I: 53%, C: 61%

Child-Pugh score (mean or %) B: A/B/C I: 15/5/0, C: 15/10/5 C: I: 7 (6-8), C: 6 (5.7-7)

MELD score B: NR C: I: 10.8 (8.6-13), C: 11.7 (9.2-13.8)

INR B: NR C: I: 1.3 (1.2-1.4), C: 1.4 (1.2-1.6)

Etiology (%) HBV/HCV/NBNC: I: 4/6/10, C: 7/16/7

*Extracted from individual studies.

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

B: Edoxaban (60 mg once daily for 6 months, dosage was halved in patients with eGFR 30-50 ml/min, patients <60 kg and patients with concurrent treatment with a strong P-glycoprotein inhibitor) C: Dabigatran (duration of therapy: 14.1 ± 6.9 months)

|

Describe control:

B: Warfarin (dosage adjusted to achieve INR 1.5-2.0) C: vitamin K antagonists (duration of therapy: 10.5 ± 6.7 months)

|

End-point of follow-up:

B: 6 months (regular clinical FU at 2 wks, 1 month, 3 months and 6 months) C: NR (once a month for the initial 3 months followed by once in 3 months)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? B: NR C: NR

|

Outcome major bleeding Defined as major bleeding by study authors or interpreted as major by the review authors.

DOAC (n/N) B: 3/20 C: 1/36

VKA (n/N) B: 2/30 C: 3/62

Outcome mortality Defined as overall mortality

DOAC (n/N) B: NR C: 1/36

VKA (n/N) B: NR C: 3/62

LMWH (n/N) B: NA C: NA

Outcome progressive SVT Defined as progression of SVT at follow-up imaging.

DOAC (n/N) B: 1/20 C: NR

VKA (n/N) B: 14/30 C: NR

LMWH (n/N) B: NR C: NA

(recurrent) VTE Defined as deep vein thrombosis of the lower or upper extremities, pulmonary embolism, or recurrent SVT

DOAC (n/N) B: NR C: 4/36

VKA (n/N) B: NR C: 4/62

LMWH (n/N) B: NA C: NA

Recanalization of SVT Defined as any grade of recanalization (partial or complete) at follow-up imaging

DOAC B: 18/20

VKA B: 9/30

|

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): Tool used by authors: ROBINS-I

B: high C: high

Author’s conclusion In summary, anticoagulant therapy for SVT is associated with vein recanalization and low probability of thrombosis progression. The risks of recurrent VTE and major bleeding in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy and the proportion of events in those left untreated strongly suggest the need for additional studies to optimize SVT management.

Remarks Sharma (2020): Any patient who was switched over to dabigatran from VKAs was considered in dabigatran arm.

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

Research question: What are the (un)desirable effects of treatment with Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOAC) in adult patients with acute abdominal vein thrombosis, compared to treatment with low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH), vitamin K antagonist (VKA) or heparin?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Naymagon, 2020 |

Type of study: Retrospective study

Setting and country: Urban tertiary care center, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Non commercial funding and no COI. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with ICD code for non-cirrhotic (acute) PVT seen between January 2000 and February 2019.

Exclusion criteria: Splanchnic vein thrombosis without portal vein involvement, had cirrhosis or tumor thrombus, received interventional thrombolysis/thrombectomy, lacked baseline imaging of PVT at diagnosis, lacked subsequent follow-up imaging at least 3 months after diagnosis, or seemed to have chronic rather than acute PVT (eg, had known prior history of PVT or had evidence of cavernous transformation or other radiographic features to suggest chronic PVT at the time of initial diagnosis).

N total at baseline: 330 of which 57 did not receive anticoagulation Intervention: 93 Control1: 108 Control 2: 70

Important prognostic factors2: age (median (IQR)): I: 47.1 (15.2) C1: 50.4 (14.8) C2: 51.4 (16.9)