Oefentherapie bij patellofemorale pijn (PFP)

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van oefentherapie bij patiënten met patellofemorale pijn?

Aanbeveling

Adviseer de patiënt als basis voor de behandeling van patellofemorale pijn quadriceps- en/of heup-georiënteerde oefentherapie gedurende minimaal zes tot twaalf weken en bij voorkeur (deels) onder begeleiding van de fysio- of oefentherapeut.

Bouw het oefenprogramma gestructureerd op (in omvang en in intensiteit); zorg daarbij voor continue afstemming op de klachtenintensiteit van de patiënt.

Besteed aandacht aan mondelinge en schriftelijke educatie voor de patiënt.

Evalueer na zes en twaalf weken de progressie van het oefenprogramma (omvang en intensiteit), pijn (bijvoorbeeld Visual Analogue Scale) en functie (bijvoorbeeld Anterior Knee Pain Score) op gestructureerde wijze.

Overweeg bij onvoldoende progressie na zes weken aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen conform de aanbevelingen (zie de module Aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen PFP).

Heroverweeg de diagnose patellofemorale pijn indien na twaalf weken gestructureerde oefentherapie geen verbetering van pijn en functie zijn opgetreden (zie ook de module Anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek PT).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De literatuur laat een klinisch relevant korte termijneffect zien van oefentherapie op pijn bij patiënten met patellofemorale pijn. Er werden geen klinisch relevante verschillen gevonden voor pijn op lange termijn en functioneren op korte termijn. De bewijskracht van de gevonden studies is laag, door imprecisie en risico op bias in de studies. Terugkeer naar sport en/of werk en de duur van het verzuim werden niet beschreven in de geïncludeerde studies. Patiënttevredenheid werd niet beschreven in de review van der Heijden (2015), maar wel in de RCT van Rathleff (2015), waarin de tevredenheid van patiënten is gemeten op een 5-punt-schaal. Patiënten die naast educatie ook oefentherapie ontvingen, lijken meer tevreden dan wanneer ze alleen educatie krijgen (GRADE laag). Ook lijkt er een positief effect van oefentherapie op het door patiënten gerapporteerde herstel.

Het blijft ingewikkeld om de verschillende interventies (duur, oefeningen, intensiteit) die zijn gedaan in de verschillende studies en geëvalueerd met verschillende uitkomstmaten samen te vatten.

Duur

De duur van de interventieperiode in de geïncludeerde studies liep uiteen van vier weken (Fukuda, 2010) tot vier maanden (Moyano, 2012), waarbij begeleiding door een fysiotherapeut varieerde van één keer per twee weken (Clark, 2000) tot drie keer per week (Fukuda, 2010; Herrington, 2007; Moyano, 2012; Rathleff, 2015). De interventies bestonden deels uit een enkele oefening (Abrahams, 2003; Herrington, 2007) en deels uit oefenprogramma’s die tussen 25 minuten (Van Linschoten, 2009) en 50 minuten (Saad, 2018) duurden. In sommige studies werden naast de begeleide oefensessies ook dagelijkse oefeningen voor thuis voorgeschreven die tussen 15 minuten (Rathleff, 2015) en 25 minuten (Van Linschoten, 2009) duurden.

Oefeningen

De oefenprogramma’s in de geïncludeerde studies waren quadriceps-georiënteerd (bijvoorbeeld Abrahams, 2003; Loudon, 2004; Herrington, 2007), heup-georiënteerd (Hott, 2019 en 2020; Saad, 2018) of een combinatie van beiden (bijvoorbeeld Clark, 2000; Fukuda, 2010; Rathleff, 2015).

Quadriceps-georiënteerde oefenprogramma’s bevatten zowel open keten als ook gesloten keten oefeningen (Abrahams, 2003; Song, 2009; Herrington, 2007). Zo werden bijvoorbeeld de leg extension (open keten) tussen nul en tien graden flexie uitgevoerd (Hott, 2019 en 2020), tussen 60 en 90 graden flexie (Saad, 2018) of tussen 0 en 90 graden flexie (Herrington, 2007). Als gesloten keten oefeningen zijn bijvoorbeeld de leg press tussen 0 en 45 graden flexie (Fukuda, 2010) en tussen 0 en 90 graden flexie (Loudon, 2004; Herrington, 2007) gebruikt. Andere veel gebruikte gesloten keten oefeningen zijn de squat, de one-leg squat en de step up (Song, 2009; Fukuda, 2010; Hott, 2019 en 2020; Loudon, 2004; Moyano, 2013).

Heup-georiënteerde oefenprogramma’s bevatten veelal de ‘clam exercise’ (Hott, 2019 en 2020), ‘side-lying abduction’ (Saad, 2018; Hott, 2019 en 2020), heupabductie in stand (Fukuda, 2010), heupexorotatie in zit (Fukuda, 2010), ‘prone hip extensions’ (Saad, 2018; Hott, 2019 en 2020), ‘seated hip abduction’ (Saad, 2018) en de ‘side plank’ (Saad, 2018).

Intensiteit

De omvang van de oefeningen liep uiteen van drie keer per dag één serie van 15 herhalingen (Abrahams, 2003), tot vier series van zes herhalingen (Herrington, 2007). Bij de isometrische oefeningen werd bijvoorbeeld drie keer één minuut belastingstijd gehanteerd (Saad, 2018). Het is vaak onduidelijk hoe de intensiteit van de oefeningen is bepaald, wat de criteria waren voor het bepalen van die intensiteit en of/hoe in het verloop van de interventieperiode de intensiteiten zijn aangepast op basis van afnemende pijn, verbeterde motorische controle en rekrutering (Clark, 2000; Abrahams, 2003; Loudon, 2004; Van Linschoten, 2009). In de studie van Rathleff (2015) is in eerste instantie de intensiteit van de oefeningen bepaald aan de hand van drie criteria: (1) goede bewegingskwaliteit (controle over heup, knie en voet), (2) volbrengen van het aantal herhalingen, (3) geen toename van pijn na de training of de volgende ochtend. Vervolgens zijn de oefeningen gedurende de interventieperiode verzwaard aan de hand van een opbouw in oefeningen.

Het is vaak onduidelijk of proefpersonen ook daadwerkelijk het trainingsprogramma onder begeleiding dan wel thuis hebben uitgevoerd zoals gepland (Clark, 2000; Abrahams, 2003; Fukuda, 2010; Moyano, 2012). Alleen in de studie van Rathleff (2015) wordt een expliciete subgroep analyse gemaakt, waaruit blijkt dat patiënten met een hoge therapietrouw (> 80% van alle begeleide oefensessies aanwezig) een grotere kans op herstel hadden.

Studiepopulaties en subgroepen

In de geïncludeerde studies is een zekere bandbreedte van kenmerken van proefpersonen te vinden wat geslacht en leeftijd betreft. Over het algemeen zijn zowel vrouwen als mannen als proefpersonen geïncludeerd, waarbij opvalt dat in de studie van Herrington, 2007 alleen mannen participeren en in de studie van Fukuda (2010) alleen vrouwen. Over het algemeen zijn de onderzoeken uitgevoerd bij jongvolwassen proefpersonen (18 tot 30 jaar). De studie van Rathleff (2015) heeft betrekking op adolescenten (gemiddelde leeftijd van 17 jaar) en de studie van Moyano (2012) op volwassenen (gemiddelde leeftijd van 40 jaar).

Het belangrijkste onderdeel van de onderzochte interventies was een vorm van oefentherapie waarbij het activeren van quadriceps- en heupspieren centraal stond. Zeven van de hier geïncludeerde studies bevatten ook stretchoefeningen van de grote spiergroepen (meestal quadriceps en hamstrings). De werkgroep is van mening dat bij patiënten met verkortingen van deze spiergroepen in individuele gevallen de activerende quadriceps- en heupspieroefeningen gecombineerd dienen te worden met stretchoefeningen voor verkorte spiergroepen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Om inzicht te krijgen in de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten met patellofemorale pijn is er in samenwerking met Patiëntenfederatie Nederland een vragenlijst opgesteld en uitgezet. De vragenlijst werd ingevuld door 43 patiënten met patellofemorale pijn, waarvan 34 mannen (79%). Van deze patiënten waren vier patiënten jonger dan 18 jaar (9%), 23 patiënten in de leeftijd tussen 19 en 30 jaar (54%), zes patiënten tussen 31 en 40 jaar (14%) en negen patiënten tussen 41 en 65 jaar (21%) (van één patiënt is de leeftijd onbekend). Met 28 van deze patiënten met patellofemorale pijn (65%) is de behandelmogelijkheid “oefeningen, bijvoorbeeld onder begeleiding van de fysiotherapeut” besproken. In totaal hebben 30 van de 43 patiënten met patellofemorale pijn (70%) oefeningen uitgevoerd, 15 van deze patiënten (50%) waren (zeer) tevreden met de oefeningen en negen patiënten (30%) waren (zeer) ontevreden. Patiënten benoemen een aantal voordelen van deze behandelmogelijkheid zoals “eigen regie”, “actief bezig zijn met klachten”, “duidelijke uitleg van oefeningen en beoogd effect voor klachten”, “combinatie van symptoom behandelen en gedoseerd opbouwen van bewegen” en “kracht in de benen/ sterker worden”. Patiënten benoemen een aantal nadelen van deze behandelmogelijkheid zoals “consequent uitvoeren is lastig en neemt tijd in beslag”, “geen begeleiding erbij, er was ook geen evaluatie”, “pijn/ te veel pijn”.

De werkgroep concludeert uit het bovenstaande dat méér patiënten met patellofemorale pijn geattendeerd moeten worden op de mogelijkerwijs gunstige effecten van de behandelmogelijkheid “oefentherapie”. Hierbij dient voldoende educatie, begeleiding en evaluatie geboden te worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Oefentherapie voor patiënten met patellofemorale pijn wordt veelal onder begeleiding van de fysio- of oefentherapeut uitgevoerd. Er zijn aanwijzingen dat oefentherapie bij adolescenten en jongvolwassenen kosteneffectief is (Tan, 2010). Frequentie en omvang van begeleiden door de fysio- of oefentherapeut zal van verschillende factoren afhangen (klachtenduur en -intensiteit, doel van de revalidatie, therapietrouw enzovoort). In de geïncludeerde studies liepen het aantal contacten met de fysiotherapeut uiteen van zes contacten in drie maanden (Clark, 2000) tot 48 contacten in vier maanden (Moyano, 2012).

De directe kosten voor fysio- of oefentherapeutische begeleiding zijn voor de patiënt. Indien de patiënt over een aanvullende zorgverzekering beschikt en de fysio- of oefentherapeut gecontracteerde zorg levert, zal de begeleiding ten laste van de aanvullend zorgverzekering zijn. In de afgelopen jaren is de omvang van fysio- of oefentherapeutische begeleiding vanuit de aanvullende zorgverzekering sterk afgenomen, waardoor het contact vaak beperkt is tot zes of negen behandelingen. Bij patiënten met een gunstig prognostisch profiel en lagere functie-eisen kan dit beperkte contact door een gerichte combinatie van oefentherapie onder begeleiding van de fysio- of oefentherapeut en zelfstandig oefenen thuis voldoende effectief zijn. Bij patiënten met een ongunstig prognostisch profiel en hogere eisen aan het functioneren in het dagelijks leven zijn over het algemeen zes of negen behandelingen onvoldoende. Patiënten moeten in deze situatie de fysio- of oefentherapeutische zorg zelf gaan betalen wat in de praktijk vaak tot niet-optimale zorg en uitblijven van therapie-effecten leidt, omdat immers niet elke patiënt over de financiële middelen beschikt. Dit is een onwenselijke situatie.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Oefentherapie voor patiënten met patellofemorale pijn moet worden afgestemd op de wensen en mogelijkheden van de patiënt. Oefeningen worden bij voorkeur (deels) onder begeleiding van de fysio- of oefentherapeut uitgevoerd. Daarnaast worden oefeningen voor thuis geïnstrueerd, die in eerste instantie zonder extra hulpmiddelen of apparaten kunnen worden uitgevoerd. Ter voorbereiding op terugkeer in de sport zullen de faciliteiten van de fysio- of oefentherapeut (oefen-/trainingszaal) een grotere rol krijgen en wordt het eventueel nodig dat de patiënt toegang heeft tot een gym/trainingszaal dan wel sportschool. Om effecten van oefentherapie bij patiënten met patellofemorale pijn te realiseren is therapietrouw van de patiënt een kritische succesfactor, omdat de patiënt over langere tijd onder begeleiding dan wel zelfstandig oefentherapie moet uitvoeren. Uit de studie van Rathleff (2015) blijkt dat patiënten met een hogere therapietrouw een hogere kans op herstel hadden. In de literatuur zijn legio barrières beschreven die therapietrouw in de weg staan (onder andere Holt, 2020). In de context van oefentherapie bij patellofemorale pijn zijn de belangrijkste barrières voor therapietrouw: onvoldoende educatie over de reden voor oefeningen en doseringen, tijdsbestek waarover effecten verwacht kunnen worden, toename van anterieure kniepijn door de oefentherapie en onvoldoende variatie in de oefentherapie. Dit wordt ook vanuit de literatuur ondersteund (de Oliveira Silva, 2020; Winters, 2020).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Ondanks de beperkingen van de klinische studies lijkt oefentherapie op korte termijn een klinisch relevante verbetering te geven van pijnklachten.

In de klinische praktijk vertonen patiënten met patellofemorale pijn een grote bandbreedte ten aanzien van tekenen en symptomen (klachtenduur, -intensiteit, mate van beperkingen in het dagelijkse leven, coördinatie en kracht van de quadriceps- en heupspieren).

Klachtenduur vòòr interventie en de intensiteit van de pijn (VAS-Worst Pain) zijn geassocieerd met een langduriger beloop van de klachten (Collins, 2013).

Zo profiteert mogelijkerwijs een patiënt met een hoge klachtenintensiteit én zwakke heupspieren in eerste instantie meer van een pijnvrij en heup-georiënteerd oefenprogramma. Andersom kan een patiënt met een lage klachtenintensiteit en zwakte van de quadriceps profiteren van een quadriceps-georiënteerd oefenprogramma, waarbij “geen toename van pijn na de training of de volgende ochtend” als criterium gehanteerd wordt. De werkgroep is daarom van mening dat keuzes rondom oefeningen, omvang, intensiteit en het wel of niet accepteren van pijn in samenspraak met de patiënt en gebaseerd op de individuele behandelbare grootheden genomen moeten worden. Een groot deel van de oefeningen kan in eerste instantie worden uitgevoerd zonder begeleidende apparatuur. Bij een sport specifieke opbouw en terugkeer naar de sport zijn wel aanvullende oefenmaterialen nodig.

Tenslotte worden educatieve elementen in de behandeling van patiënten met patellofemorale pijn door de werkgroep van belang geacht. Een recente review hierover (de Oliveira Silva, 2020) merkt op dat advies door de behandelaar over het belasten van de knie (‘load management’), advies over het zelf beheersen van pijnklachten (‘selfmanagement’) en uitleg over de oorsprong en mogelijke oorzaken van PFP even effectief zou kunnen zijn als oefentherapie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Patellofemorale pijn (PFP) is een veelvoorkomende en vaak langdurige musculoskeletale klacht, waarbij oefentherapie als kerncomponent van een multimodale aanpak als ‘best evidence’ wordt beschouwd (Collins, 2018; Crossley, 2016). In het ‘evidence based framework for a pathomechanical model of patellofemoral pain’ wordt in het algemeen gesproken over verhoogde stress op het patellofemorale gewricht als bijdragende factor voor het ontstaan (en in stand houden) van nocicepsis vanuit structuren in de anterieure knie (Powers, 2017). Hierbij kunnen zowel patellofemorale malalignment/maltracking als ook verhoogde reactiekrachten een rol spelen. Dit kan gepaard gaan met “niet-mechanische” factoren zoals perifere sensitisatie, catastroferen en kinesiofobie. Oefentherapie tracht de mechanische factoren (bijvoorbeeld reductie femorale endorotatie; Collins 2018), maar ook de niet-mechanische factoren (bijvoorbeeld afname van perifere sensitisatie; Holden, 2020) te beïnvloeden

In Nederland ontvangen patiënten met PFP vaak het advies een vorm van oefentherapie uit te voeren ter klachtenreductie. Hierbij signaleert de werkgroep een drietal knelpunten.

Een eerste knelpunt betreft het feit dat in de praktijk nog steeds regelmatig patiënten niet het advies “oefentherapie” krijgen (zie “waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten”).

Een tweede knelpunt betreft praktijkvariatie in aantal oefeningen, series en herhalingen en criteria (vermoeidheid en/of pijn).

Een derde knelpunt betreft de duur van de oefentherapie. Voor alle betrokken partijen is vaak niet duidelijk op wat voor termijn een relevante klachtenreductie verwacht kan worden, in welke mate patiënten zelfstandig moeten oefenen en hoeveel oefentherapeutische behandelingen door de fysio- of oefentherapeut minimaal nodig zijn (minimale versus optimale zorg).

Op basis van bovenstaande knelpunten is een literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar de effectiviteit van quadriceps- dan wel heup-georiënteerde oefentherapie (of een combinatie) waarbij de controlegroep geen specifieke oefentherapie ontving. Er is niet voor gekozen om alle verschillende vormen van oefentherapie met elkaar te vergelijken, aangezien de verwachting is dat er meer onderzoek is verricht naar oefentherapie versus geen oefentherapie.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Pain (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests exercise therapy reduces pain in the short-term.

Sources: (van der Heijden, 2015; Saad, 2018) |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that exercise therapy results in little to no difference in pain in the long-term.

Sources: (van der Heijden, 2015) |

2. Function (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that exercise therapy results in little to no difference in function in the short-term.

Sources: (van der Heijden, 2015; Hott, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect of exercise therapy is on function in the long-term.

Sources: (van der Heijden, 2015; Hott, 2020) |

3. Return to sport/work (important)

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measure return to sport/work was not reported in the included studies. |

4. Duration of absenteeism (important)

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measure duration of absenteeism was not reported in the included studies. |

5. Patient satisfaction (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Exercise therapy in combination with education may result in a slightly positive effect on patient satisfaction in the short-term and in the long-term compared to education alone.

Sources: (Rathleff, 2015 |

6. Patient recovery (important)

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that exercise therapy with or without education may results in a higher number of recovered patients in the short-term compared to education alone or usual care.

Sources: (Rathleff, 2015; van der Heijden, 2015) |

|

Low GRADE |

The evidence suggests that exercise therapy with or without education may results in a higher number of recovered patients in the long-term compared to education alone or usual care.

Sources: (Rathleff, 2015; van der Heijden, 2015) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The Cochrane systematic review of van der Heijden (2015) described the effects of exercise therapy on pain, function and recovery in adolescents and adults with patellofemoral pain. A total of 31 randomized and quasi-randomized studies, comprising 1690 participants, were included in this review. Different comparisons were included: exercise therapy versus control, exercise therapy versus other conservative therapy, hip and knee exercises versus knee exercises. To answer our clinical question, only the data of the eight studies included in the comparison ‘exercise therapy versus control’ were extracted from this review (Abrahams, 2003; Clark, 2000; Fukuda, 2010; Herrington, 2007; Loudon, 2004; Moyano, 2013; Song, 2009; Van Linschoten, 2009). These studies included different types of exercise therapy and different control groups: as described in Table 1. Overall, there was a moderate risk of bias (ROB) in these studies, given the uncertainty about or lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors.

In addition to the review, Hott (2019) and Hott (2020) describe the same single-blind RCT. In this RCT three groups were compared; knee exercises (n=37), hip exercises (n=39) and free physical activity (n=36) on function, at different times of follow up: 3 months (Hott, 2019) and 12 months (Hott, 2020). Details of the exercise therapy and control groups can be found in Table 1.

Rathleff (2015) described a cluster RCT. A total of 121 adolescents with patellofemoral pain participated, the experimental group received exercise therapy and education and the control group received education alone. The effects were evaluated on patients’ satisfaction and recovery at eight weeks postintervention. Details of the exercise therapy and control groups can be found in Table 1.

The RCT of Saad (2018) compared three different exercises groups (8 weeks intervention) and a control group. A total of 40 recreational female athletes with patellofemoral pain participated. The effects were evaluated on pain and function at eight weeks postintervention. Details of the exercise therapy and control groups can be found in Table 1.

Table 1 Intervention types and control groups

|

|

Intervention group |

Control group |

|

Abrahams (2003) |

traditional exercise protocol: semi squat in neutral to 30 degrees knee flexion held for 2 seconds with subsequent straightening of the knee and rising: 15 repetitions, 3 times daily, for 6 weeks |

waiting list controls |

|

traditional exercise protocol with thigh adduction and tibia medial rotation during eccentric squat 15 repetitions, 3 times daily, for 6 weeks |

||

|

Clark (2000) |

Exercise + tape (+stretching and education): 6 sessions and daily training at home Exercise included wall squat, sit to stand, proprioceptive balance, specific exercises for gluteus medius and maximus, progressive step-down exercises 3 months |

education alone (no treatment) |

|

Exercise (+stretching and education): 6 sessions and daily training at home Exercise included wall squat, sit to stand, proprioceptive balance, specific exercises for gluteus medius and maximus, progressive step-down exercises 3 months |

||

|

Tape (+education): 6 sessions and daily at home |

||

|

Fukuda (2010) |

Knee exercise group: Knee exercises including iliopsoas strengthening in non-weight bearing, seated knee extension 90°-45°, leg press 0°-45°, squatting 0°-45° 3 treatment sessions per week for 4 weeks |

no treatment |

|

knee and hip exercise group: Knee and hip exercises including iliopsoas strengthening in non-weight bearing, seated knee extension 90°-45°, leg press 0°-45°, squatting 0°-45°, hip abduction against elastic band (standing), hip abduction with weights (side lying), hip external rotation against elastic band (sitting), side-stepping against elastic band, 3 x 1-minute lateral rotator muscles 3 treatment sessions per week for 4 weeks |

||

|

Herrington (2007) |

Multi Joint Weight Bearing (= CKC) including leg press exercise in a seated position from 90° of knee flexion to full extension 6 weeks, 3 times per week |

no treatment |

|

Single Joint Non-Weight Bearing (= OKC) including knee extension exercises in a seated position from 90° of knee flexion to full extension 6 weeks, 3 times per week |

||

|

Hott (2019&2020) |

Knee- focused exercise: straight-leg raises in the supine position, supine terminal knee extensions (from 10° of flexion to full extension), and a mini-squat (45° of flexion) with the back supported against the wall (to reduce stabilizing requirements from the hip muscles). Hip-focused exercise: (side-lying hip abduction, hip external rotation (clam shell), and prone hip extension. These exercises were intended to maximally isolate the hip abductors, extensors, and external rotators without stimulating the quadriceps muscles. 3 sessions per week (one supervised and two home sessions) for 6 weeks. Initial dosage was three sets of 10 repetitions for each exercise, progressing to a maximum three sets of 20 repetitions. At inclusion, all participants attended an individual 1-hour consultation with a specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation |

Physical activity: encouragement of physiotherapist to be physically active in accordance with the patient education component but received no specific exercise regime. At inclusion, all participants attended an individual 1-hour consultation with a specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation. |

|

Loudon (2004) |

supervised exercise programme twice a week for 4 weeks, plus 1 physical therapy visit at 6 weeks and 1 at 8 weeks, and additional home exercises Exercises included quadriceps exercises starting with isometrics followed by straight leg raises followed by closed kinetic chain, such as leg press, mini squat, step-up, lunge and balance and reach |

information leaflet (no treatment) orthotics and taping if indicated |

|

home exercise programme + 5 physical therapy visits, 8 weeks |

||

|

Moyano (2013) |

'Classic stretching protocol' (stretching and exercises for hip and knee muscles) and quadriceps strengthening exercises 3 times per week for 16 weeks |

Health educational materials |

|

Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching applied to hamstrings and quadriceps and, after the 4th week, aerobic exercise 45 minutes 3 times per week for 16 weeks |

||

|

Rathleff (2015) |

patient education (see control group) combined with exercise therapy The exercise therapy consisted of a combination of supervised group training sessions (3x pw for 3 months, consisting of neuromuscular training, strength training, mobilisation and stretching) and unsupervised home-based exercises (daily 15 min of quadriceps and hip muscle retraining and stretching). In addition, taping corrections were applied if adolescents achieved a minimum pain reduction of 50% during a two-leg squat. |

patient education provided by physiotherapist one-on-one to the adolescents and their parents. The 30-minute session consisted of pain management; how to modify physical activity using pacing and load management strategies; information on optimal knee alignment during daily tasks; and responses to questions of the patient and parents. Patients also received an information leaflet. |

|

Saad (2018) |

hip strengthening 2x pw 50 min individual session 8 weeks |

no treatment |

|

quadriceps strengthening 2x pw 50 min individual session 8 weeks |

||

|

stretching exercises for hip and knee stabilizers 2x pw 50 min individual session 8 weeks |

||

|

Song (2009) |

Leg-press exercise only (0-45o) (knee) 3 times a week during 8 weeks |

Health educational material |

|

Hip adduction combined with leg-press exercise (knee + hip) 3 times a week during 8 weeks |

||

|

Van Linschoten (2009) |

Exercise therapy including static and dynamic exercises for quadriceps, adductor and gluteal muscles: 9 times in 6 weeks + daily at home for 3 months |

usual care ('wait and see policy') |

Results

1. Pain (critical)

Pain was measured by a visual analogue scale (VAS) or numerical (pain) rating scale (N(P)RS).

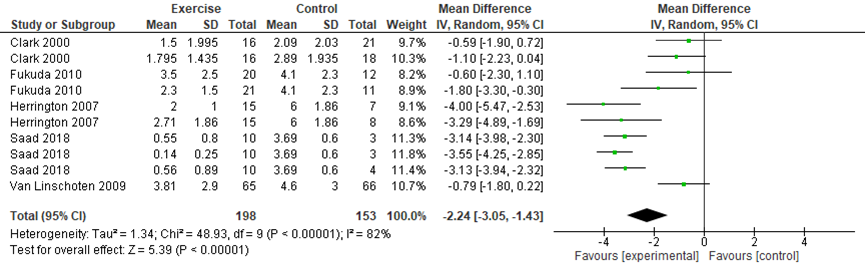

Pain during activity in the short-term (≤ 3 months) was presented in five studies included in the review (Clark, 2000; Fukuda, 2010; Herrington, 2007; Van Linschoten, 2009; n=375). In addition, Saad (2018, n=40) reported pain intensity for the four study groups, it was not specified whether or not this pain score was obtained during activity. In the meta-analysis (figure 1), the data of the control groups were split for studies that included multiple comparisons, so that the individual results of each intervention could be presented while avoiding double counting of those in the control group. The small study of Saad (2018) has a large impact due to the four groups, see table 1. The pooled data resulted in a mean difference (MD) of -2.24 (95%CI: -3.05 to -1.43), favoring exercise therapy.

Figure 1 Pain during activity short-term

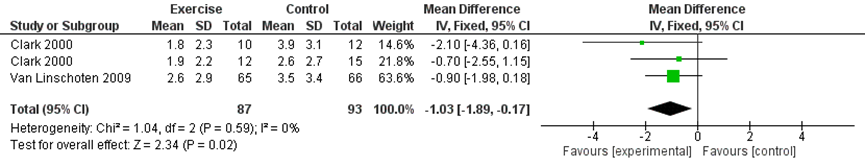

Two studies in the Cochrane review determined the long-term effect of exercise therapy on pain during activity (Clark, 2000; van Linschoten, 2009; n=180). The MD was -1.03 (95%CI -1.89 to -0.17), favoring exercise therapy. See figure 2.

Figure 2 Pain during activity long-term

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome pain (short-term effects) started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials but was downgraded by 2 levels due to study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and heterogeneity in study results (inconsistency, -1). The final level is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome pain (long-term effects) started at high as it was based on RCTs but was downgraded by 2 levels due to study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The final level is low.

2. Function (critical)

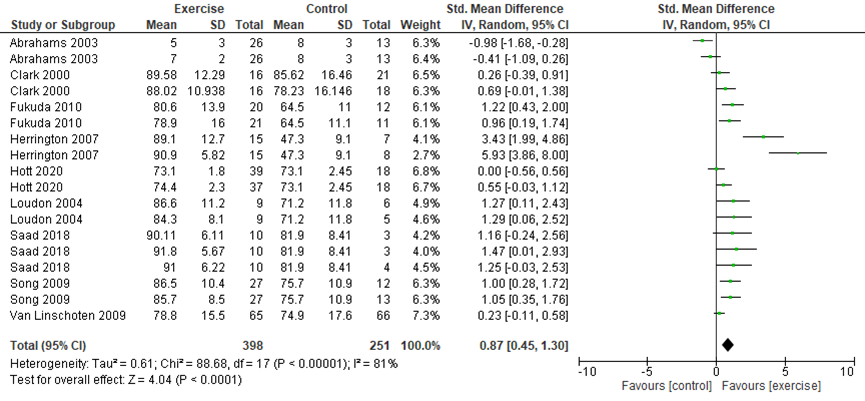

Function was scored with the Anterior Knee Pain Scale (AKPS) (Kujala, 1993), (modified) function scale (Werner, 1993), Lysholm score (Lysholm, 1982), and (modified) Functional Index Questionnaire (MFIQ 0 to 16/100). A higher score means better function. Function (short-term effects) was presented in nine studies (Abrahams, 2003; Clark, 2000; Fukuda, 2010; Herrington, 2007; Hott, 2020; Loudon, 2004; Saad, 2018; Song, 2009; Van Linschoten, 2009; (n=673). The meta-analysis showed a SMD of 0.87 (95%CI: 0.45 to 1.30), favoring exercise therapy. See Figure 3. To interpret these results, the SMD was multiplied with the pooled SD (10.33) of all studies using the AKPS (Fukuda 2010; Herrington, 2007; Hott, 2020; Loudon, 2004; Saad, 2018; Van Linschoten, 2009). The mean difference in functional ability was estimated at 8.98 higher (95%CI: 4.65 to 13.43) favoring the exercise group, this is not a clinically important difference.

Figure 3 Function in the short-term

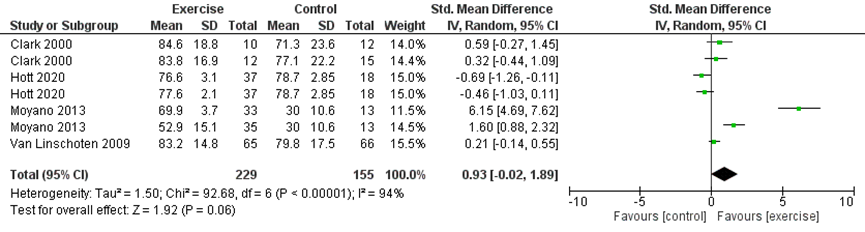

Function (long-term effects) was presented in three studies in the Cochrane review (Clark, 2000; Moyano, 2013; Van Linschoten, 2009; 274 participants). Besides, long-term function was reported by Hott, 2020 (n=112) using the AKPS score. The pooled data resulted in a SMD of 0.93 (95%CI: -0.02 to 1.89), favoring exercise therapy. See Figure 4. To interpret these results, the SMD was multiplied with the pooled SD (11.98) of all studies using the AKPS (Hott, 2020; Moyano, 2013; Van Linschoten, 2009). The mean difference in function was estimated at 11.14 higher (95%CI: -0.23 to 23.72) favoring the exercise group.

Figure 4 Function in the long-term

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome function (short-term effects) started at high as it was based on RCTs but was downgraded by 2 levels to low due to study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and heterogeneity (inconsistency, -1). The final level is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome function (long-term effects) started at high as it was based on RCTs but was downgraded by 3 levels to very low due to study limitations (risk of bias, -1), limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1), and heterogeneity (inconsistency, -1). The final level is very low.

3. Return to sport/work (important)

Return to sport/work was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome return to sport/work was not assessed due to lack of studies.

4. Duration of absenteeism (important)

Duration of absenteeism was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome duration of absenteeism was not assessed due to lack of studies.

5. Patient satisfaction (important)

Patient satisfaction was reported in the study of Rathleff (2015), patients were asked about their satisfaction with the result of the treatment on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “highly satisfied” to “not satisfied at all”. After 3 months 51% of the patients in the education and exercise group (n=62) were satisfied compared to 19% in the education group (n=59), resulting in a risk ratio of 2.63 (95%CI: 1.49 to 4.63). After 12 months, 60% was satisfied in the education and exercise group compared to 36% of the education group, risk ratio is 1.67 (95%CI: 1.12 to 2.49).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient satisfaction started at high as it was based on a RCT but was downgraded by 2 levels to low due to study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The final level is low.

6. Recovery (important)

Patient recovery was reported in the review of van der Heijden (2015). Recovery was measured with on the seven-point Likert scale at 3 and 12 months by Van Linschoten (2009) and at 3, 6 and 12 months by Rathleff (2015), and with the number of patients no longer troubled by symptoms at 12 months (Clark, 2000). After 3 months the pooled data from two studies (Van Linschoten, 2009; Rathleff, 2015; 243 participants) showed that the risk ratio (RR) is 1.32 favoring exercise therapy, 95%CI 0.91 to 1.92. See Figure 5.

Figure 5 Recovery in the short-term

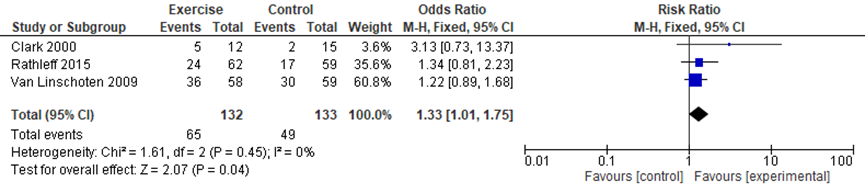

After 12 months the pooled data from three studies (Clark, 2000; Van Linschoten, 2009; Rathleff, 2015; 265 participants) showed that the risk ratio (RR) is 1.33 favoring exercise therapy, 95%CI 1.01 to 1.75. See Figure 2.7.

Figure 6 Recovery in the long-term

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome recovery in the short-term started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials but was downgraded by 2 levels to low due to study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The final level is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome recovery in the long-term started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials but was downgraded by 2 levels to low due to study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The final level is low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of exercise therapy in patients with patellofemoral pain on pain, function, return to sports/ work, duration of absenteeism, patient satisfaction, and patient recovery?

P: patients with patellofemoral pain (adolescents/adults, non-traumatic);

I: exercise therapy;

C: control group/ placebo/ wait and see policy;

O: pain, function, return to sports/ work, duration of absenteeism, patient satisfaction, and patient recovery.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain and function as a critical outcome measures for decision making; and return to sport/work, duration of absenteeism, and patient satisfaction as important outcome measures for decision making. For the outcome pain the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) were used. For the outcome function the Kujala score/ Anterior Knee Pain Score (AKPS) are often used in studies, however, other measurement instruments could also be used. Return to sport/work was measured with the Tegner score. Satisfaction with the result of treatment and recovery were usually measured on a Likert scale.

The working group defined a difference of 2 cm (out of 10 cm) on the VAS or 2 categories on the NRS scale as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference, according to Crossley, 2004. For the Kujala score/ AKPS score, a difference of 10 point (out of 100 points) was defined as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference, according to Crossley, 2004. A minimal clinically important difference for return to sport/work measured with the Tegner score was not predefined. A minimal clinically important difference for duration of absenteeism, patient satisfaction and patient recovery was not predefined.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 22nd April 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 890 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: Systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of the individual studies available) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included at least 20 patients with patellofemoral pain, compared exercise therapy with a control group, and included at least one of the defined outcome measures. Initially eight reviews were selected based on their title and abstract. After reading the full text, seven reviews were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 1 Cochrane systematic review was included (van der Heijden, 2015). Of the 16 RCTs published after 2014 and selected based on title and abstract screening, 11 were excluded, 1 study was included in the Cochrane review, and 3 RCTs (described in 4 articles (Hott, 2019; Hott, 2020; Rathleff, 2015; Saad, 2018)) were added to the analysis of the Cochrane review.

Results

One systematic review and four RCTs studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Abrahams, S., Guilliford, D., Korkia, P, Prince, J. (2003). The influence of leg positioning in exercise programmes for patellofemoral joint pain. Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine;25(3):107-13.

- Collins NJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Crossley KM, van Linschoten RL, Vicenzino B, van Middelkoop M. (2013). Prognostic factors for patellofemoral pain: a multicentre observational analysis. Br J Sports Med.;47(4):227-33.

- Collins, N. J., Barton, C. J., van Middelkoop, M., Callaghan, M. J., Rathleff, M. S., Vicenzino, B. T., … Crossley, K. M. (2018). 2018 Consensus statement on exercise therapy and physical interventions (orthoses, taping and manual therapy) to treat patellofemoral pain: recommendations from the 5th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Gold Coast, Australia, 2017. British Journal of Sports Medicine. Retrieved from https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/18/1170.abstract

- Clark, D.I., Downing, N., Mitchell, J., et al. (2000). Physiotherapy for anterior knee pain: a randomised controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases;59(9):700–4.

- Crossley, K. M., van Middelkoop, M., Callaghan, M. J., Collins, N. J., Rathleff, M. S., & Barton, C. J. (2016). 2016 Patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 2: recommended physical interventions (exercise, taping, bracing, foot orthoses and combined interventions). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50, 844–852. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096268

- Crossley, K.M., Bennell, K.L., Cowan, S.M., Green, S. (2004). Analysis of outcome measures for persons with patellofemoral pain: which are reliable and valid? Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation;85(5):815-22.

- de Oliveira Silva, D., Pazzinatto, M. F., Rathleff, M. S., Holden, S., Bell, E., Azevedo, F., & Barton, C. (2020). Patient Education for Patellofemoral Pain: A Systematic Review. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy;50(7):388-396.

- Fukuda, T.Y., Rossetto, F.M., Magalhaes, E., et al. (2010). Short-term effects of hip abductors and lateral rotators strengthening in females with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy;40(11):736-42.

- Herrington, L., Al-Sherhi, A. (2007). A controlled trial of weight-bearing versus non-weight-bearing exercises for patellofemoral pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy; 37(4):155-60.

- Holden, S., Rathleff, M. S., Thorborg, K., Holmich, P., & Graven-Nielsen, T. (2020). Mechanistic pain profiling in young adolescents with patellofemoral pain before and after treatment: a prospective cohort study. PAIN; 161(5).

- Holt, C. J., McKay, C. D., Truong, L. K., Le, C. Y., Gross, D. P., & Whittaker, J. L. (2020). Sticking to It: A Scoping Review of Adherence to Exercise Therapy Interventions in Children and Adolescents With Musculoskeletal Conditions. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 1–54. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2020.9715

- Hott, A., Brox, J.I., Pripp, A.P. et al. (2019) Effectiveness of Isolated Hip Exercise, Knee Exercise, or Free Physical Activity for Patellofemoral Pain. A Randomized Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Sports Medicine;47(6):1312–1322

- Hott, A., Brox, J.I., Pripp, A.P. et al. (2020) Patellofemoral pain: One year results of a randomized trial comparing hip exercise, knee exercise, or free activity. Scand J Med Sci Sports; 30:741–753.

- Loudon, J.D., Gajewsk, B., Goist-Foley, H.L., Loudon, K.L. (2004). The effectiveness of exercise in treating patellofemoral-pain syndrome. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation;13:323-42.

- Moyano, F., Valenza, M.C., Martin, L. et al. (2013). Effectiveness of different exercises and stretching physiotherapy on pain and movement in patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation;27(5):409-17.

- Powers, C. M., Witvrouw, E., Davis, I. S., & Crossley, K. M. (2017). Evidence-based framework for a pathomechanical model of patellofemoral pain: 2017 patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester, UK: part 3. British Journal of Sports Medicine; 51(24), 1713.

- Rathleff, M.S., Roos, E.M., Olesen, J.L., Rasmussen, S. (2015) Exercise during school hours when added to patient education improves outcome for 2 years in adolescent patellofemoral pain: a cluster randomised trial. Br J Sports Med; 49:406–412.

- Saad, M.C., Vasconcelos, R.A., Mancinelli, L.V.O., et al. (2018). Is hip strengthening the best treatment option for females with patellofemoral pain? A randomized controlled trial of three different types of exercises. Braz J Phys Ther.;22(5):408-416.

- Song, C.Y., Lin, Y.F., Wei, T.C., et al. (2009). Surplus value of hip adduction in leg-press exercise in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Physical Therapy;89(5):409-18.

- Tan, S. S., Van Linschoten, R. L., Van Middelkoop, M., Koes, B. W., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M., & Koopmanschap, M. A. (2010). Cost-utility of exercise therapy in adolescents and young adults suffering from the patellofemoral pain syndrome. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 20(4), 568–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00980.x

- Van Linschoten, R., Van Middelkoop, M., Berger, M.Y., et al. (2009) Supervised exercise therapy versus usual care for patellofemoral pain syndrome: an open label randomised controlled trial. BMJ;339(7728):1010-13.

- Winters, M., Holden, S., Lura, C. B., Welton, N. J., Caldwell, D. M., Vicenzino, B. T., … Rathleff, M. S. (2020). Comparative effectiveness of treatments for patellofemoral pain: a living systematic review with network meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, bjsports-2020-102819.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

van der Heijden, 2015

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to (month/year)

A: Abrahams, 2003 B: Clark, 2000 C: Fukuda, 2010 D: Herrington, 2007 E: Loudon, 2004 F: Moyano, 2013 G: Song, 2009 H: Van Linschoten, 2009

Study design: RCTs and quasi-randomised trials

Setting and Country: A: n.r., UK B: Australia C: n.r., Brazil D: Physical Therapy Department at Riyadh Armed Forces Hospital; Saudi Arabia E: n.r., USA F: n.r., Spain G: n.r., Taiwan H: n.r., the Netherlands

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

31 studies included in total, 10 studies compared exercise therapy with control

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: 78 patients, 29 yrs, 50% female B: 81 patients, 28 yrs, 44% female C: 70 patients, 25 yrs, all female D: 45 patients, 27 yrs, all male E: 32 patients, 27 yrs, 76% female F: 94 patients, 40 yrs, 43% female G: 89 patients, 41 yrs, 87% female H: 131 patients, 24 yrs, 64% female

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention:

A: 1) Traditional exercise protocol / 2) Same exercise protocol with thigh adduction and tibia medial rotation during eccentric squat B: 1) Exercise + tape: 6 sessions and daily training at home / 2) Exercise: 6 sessions and daily training at home C: 1) Knee exercises including iliopsoas strengthening in non-weight bearing, seated knee extension 90°-45°, leg press 0°-45°, squatting 0°-45° / 2) Knee and hip exercises including iliopsoas strengthening in non-weight bearing, seated knee extension 90°-45°, leg press 0°-45°, squatting 0°-45°, hip abduction against elastic band (standing), hip abduction with weights (side lying), hip external rotation against elastic band (sitting), side-stepping against elastic band, 3 x 1 minute lateral rotator muscles D: 1) Single Joint Non-Weight Bearing (= OKC) including knee extension exercises in a seated position from 90° of knee flexion to full extension / 2) Multi Joint Weight Bearing (= CKC) including leg press exercise in a seated position from 90° of knee flexion to full extension E: 1) Home exercises + 5 physical therapy visits / 2) Supervised exercises twice a week for 4 weeks, plus 1 physical therapy visit at 6 weeks and 1 at 8 weeks; and additional home exercises F: 1) 'Classic stretching protocol' (stretching exercises for hip and knee muscles) and quadriceps strengthening exercises: 3 times per week 2) Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching applied to hamstrings and quadriceps and, after the 4th week, aerobic exercise: 3 times per week G: 1) Hip adduction combined with leg-press exercise (knee + hip): 3 times a week / 2) Leg-press exercise only (knee): 3 times a week H: Exercise therapy including static and dynamic exercises for quadriceps, adductor and gluteal muscles: 9 times in 6 weeks + daily at home |

Describe control:

A: waiting list B: 1) Tape: 6 sessions and daily at home / 2) no treatment. Additional intervention in all groups: education C: no treatment D: no treatment E: no treatment F: Health educational materials G: Health educational material H: Usual care: "wait and see" approach

|

Endpoint of follow-up:

A: 6 weeks B: 12 months C: 4 weeks D: 6 weeks E: 8 weeks F: 16 weeks G: 8 weeks H: 12 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: no dropouts B: 12% dropout in the short-term; 39% dropout at 12 months follow-up C: 11% dropout in the short term D: no dropout E: 10% dropout F: 2.7% dropout in the short-term G: 11% dropout in the short-term H: 11% dropout in the short-term

|

Outcome measure pain (short-term)

Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): B: 0.59 (-1.90, 0.72) -1.10 (-2.23, 0.04) C: -1.80 (-3.30, -0.30) -0.60 (-2.30, 1.10) D: -4.00 (-5.47, -2.53) -3.29 (-4.89, -1.69) H: -0.79 (-1.80, 0.22)

Pooled effect (random effects model): -1.46 (95% CI -2.39 to -0.54) favoring intervention group Heterogeneity (I2): 74%

Outcome measure pain (long-term)

Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): B: -2.11 (-4.37, 0.15) -0.69 (-2.52, 1.14) H: -0.97 (-2.05, 0.11)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): -1.07 (95% CI -1.93 to -0.21) favoring intervention group Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure function (short-term)

Effect measure: standardized mean difference (95% CI): B: 0.69 (-0.01, 1.38) 0.69 (-0.39, 0.91) C: 0.96 (0.19, 1.74) 1.21 (0.43, 2) D: 5.93 (3.86, 8) 3.43 (1.99, 4.86) E: 1.29 (0.06, 2.52) 1.27 (0.11, 2.43)

F: 1.05 (0.35, 1.76) 1 (0.28, 1.72) H: 0.23 (-0.11, 0.58)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.1(95% CI 0.58 to 1.63) favoring intervention group Heterogeneity (I2): 84%

Outcome measure function (long-term)

Effect measure: standardized mean difference (95% CI): B: 0.59 (-0.27, 1.46) 0.32 (-0.44, 1.09) F: 6.16 (4.7, 7.63) 1.6 (0.88, 2.32) H: 0.21 (-0.14, 0.55)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.62 (95% CI 0.31 to 2.94) favoring intervention group Heterogeneity (I2): 97% |

Author’s conclusion This review has found very low quality but consistent evidence that exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) may result in clinically important reduction in pain and improvement in functional ability, as well as enhancing long-term recovery. However, the best form of exercise therapy and whether this result would apply to all people with PFPS are unknown. |

Evidence table for intervention studies

Research question: Wat is de waarde van oefentherapie bij patiënten met patellofemorale pijn?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Hott, 2019/ Hott, 2020 |

Type of study: single-blind RCT

Setting and country: outpatient clinic at the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Sørlandet Hospital, Norway

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by The Research Department of Sørlandet Hospital. No conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Aged between 16 years 40 years, a minimum 3-month history of PFP (pain, ≥3 of 10) reproduced by at least 2 activities (stair ascent/descent, hopping, running, prolonged sitting, squatting, kneeling) and present on at least 1 clinical test (compression of the patella, palpation of the patellar facets). For patients with bilateral pain, the worst knee was included. Exclusion criteria: (1) clinical, radiographic, or MRI findings indicative of other specific pathology, including meniscal, ligament, or cartilage injury, as well as osteoarthritis, epiphysitis, significant knee joint effusion, or recurrent patellar subluxation or dislocation; (2) significant pain from hip or back hindering the ability to perform the prescribed exercises; (3) previous surgery to the knee joint; (4) nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or cortisone use over an extended period; (5) previous trauma to the knee joint with an effect on the presenting clinical condition; and (6) physiotherapy or other similar exercises for patellofemoral pain within the previous 3 months.

N total at baseline: Knee: 37 Hip: 39 Control: 36

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: Knee: 28.5±6.2 Hip: 27.8±8.6 C: 26.3±7.0

Sex: Kneel: 35% M Hip: 36% M C: 33% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

The hip-based and knee-based exercise regimens were matched in dosage and progression. Three sessions per week were performed for 6 weeks: 1 under supervision of the physiotherapist and 2 home sessions, with at least 1 day between sessions. Initial dosage was 3 sets of 10 repetitions for each exercise, with progression to a maximum 3 3 20 repetitions. Each repetition was performed dynamically over 2 to 3 seconds, with a 2-second pause between repetitions and a 30-second pause between sets. Additional resistance thereafter was achieved through weights or elastic tubing depending on the exercise.

The knee-focused exercise regimens intended to maximally isolate the quadriceps muscles. The exercises consisted of straight-leg raises in the supine position, supine terminal knee extensions (from 10○ of flexion to full extension), and a mini-squat (45○ of flexion) with the back supported against the wall (to reduce stabilizing requirements from the hip muscles). The hip-focused exercises consisted of side-lying hip abduction, hip external rotation (clam shell), and prone hip extension. These exercises were intended to maximally isolate the hip abductors, extensors, and external rotators without stimulating the quadriceps muscles. |

The control group was encouraged by the study physiotherapist to be physically active in accordance with standardized information. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months (Hott, 2019) 12 months (Hott, 2020)

Loss-to-follow-up 3 months: Knee: 6 (16%) Reasons: discontinued intervention, unavailable, illness Hip: 3 (8%) Reasons: unavailable, illness Control: 3 (8%) Reasons: dissatisfied with group allocation, time constraints

Loss-to-follow-up 6 months: Knee: 8 (22%) Reasons: discontinued intervention, unavailable Hip: 6 (15%) Reasons: unavailable, illness Control: 8 (22%) Reasons: dissatisfied with group allocation, time constraints

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

AKPS (function) at 3 months Knee: 74.4 (69.8-79.0) Hip: 73.1 (69.5-76.7) Control: 73.1 (68.2-78.0)

AKPS (function) at 12 months Knee: 76.6 (70.4 to 83.0) Hip: 77.6 (73.4 to 81.8) Control: 78.7 (73.0 to 84.4)

Usual pain at 3 months Knee: 2.6 (1.8-3.4) Hip: 2.9 (2.4-3.5) Control: 3.2 (2.5-3.9)

Usual pain at 12 months Knee: 2.8 (1.7 to 3.9) Hip: 2.2 (1.4 to 3.0) Control: 2.6 (2.1 to 3.1)

Worst pain at 3 months Knee: 4.0 (3.0-5.1) Hip: 4.9 (4.1-5.7) Control: 5.0 (4.1-5.9)

Worst pain at 12 months Knee: 3.7 (2.5 to 4.9)) Hip: 4.4 (3.6 to 5.3) Control: 3.5 (2.4 to 4.6) |

At inclusion, all participants attended an individual 1-hour consultation with a specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation. |

|

Rathleff, 2015 |

Type of study: cluster RCT

Setting and country: upper secondary school, Denmark

Funding and conflicts of interest:

funded by the Danish Rheumatism Association, The Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund and The Obelske Family Foundation. MSR is being funded by a full-time PhD scholarship from the Graduate School of Health Sciences at Aarhus University

Competing interests: None. |

Inclusion criteria: insidious onset of anterior knee or retropatellar pain of more than 6 weeks duration and provoked by at least two of the following situations: prolonged sitting or kneeling, squatting, running, hopping or stair climbing; tenderness on palpation of the patella, pain when stepping down or double leg squatting; and worst pain during the previous week of more than 30 mm on a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS).

Exclusion criteria: concomitant injury or pain from the hip, lumbar spine or other knee structures; previous knee surgery; self-reported patellofemoral instability; knee joint effusion; use of physiotherapy for treating knee pain within the previous year; or at least weekly use of anti-inflammatory drugs.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 62 Control:59

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I:17.2±1.1 C:17.3±0.9

Sex: I: 26% M C: 14% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Patient education and exercise therapy: The exercise therapy consisted of a combination of supervised group training sessions and unsupervised home-based exercises. The supervised group training sessions consisted of neuromuscular training of the muscles around the foot, knee and hip, strength training for the knee and hip, patellofemoral soft tissue mobilisation, and stretching of the muscles around the hip and knee. To progressively match the exercise level to the performance level of each participant, all exercises were available in multiple levels of difficulty. All adolescents started with exercises at level 1 and progressed from there. The supervised exercises were offered three times per week on school premises immediately after the end of the school day for 3 months. The unsupervised home exercises consisted of approximately 15 min of quadriceps and hip muscle retraining and stretching. Instructions were given immediately after patient education together with a five-page leaflet with pictures and descriptions of the exercises. The exercises were to be performed each day except on the days of supervised group training. The adolescents were instructed to incorporate the exercises into their normal daily routines. Taping corrections were applied in a predetermined order of anterior tilt, medial tilt, glide and fat pad unloading until the participant’s pain was reduced by at least 50%.Tape was only used if adolescents achieved a minimum of 50% reduction in pain measured with a 10 cm VAS during a two-leg squat immediately after application of the tape. |

Patient education: One physiotherapist delivered the patient education in the two clusters randomised to patient education alone. The standardised patient education was held one-on-one with the adolescents and their parents. It lasted for about 30 min and covered: pain management; how to modify physical activity using pacing and load management strategies; information on optimal knee alignment during daily tasks; and responses to questions from the adolescent or the parents. Adolescents also received this information in an eight-page leaflet. |

Length of follow-up: 3, 6, 12 and 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 3 months: 13 (21%) 6 months: 18 (29%) 12 months: 10 (16%) 24 months: 14 (23%) Reasons: n.r.

Control: 3 months: 7 (12%) 6 months: 19 (32%) 12 months: 1 (2%) 24 months: 8 (14%) Reasons: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Recovery 3 months I: 29% C: 19% OR (95% CI): 1.88 (1.25-2.81)

Recovery 6 months I: 32% C: 23% OR (95% CI): 1.43 (0.22-9.24)

Recovery 12 months I: 38% C: 29% OR (95% CI): 1.73 (1.02-2.93)

Recovery 24 months I: 44% C: 22% OR (95% CI): 2.52 (1.65-3.86)

Worst pain 3 months I: 51 (44;58) C: 40 (24;56) Adjusted mean difference (95% CI): −11 (−30 to 9)

Worst pain 6 months I: 51 (31;70) C: 41 (21;60) Adjusted mean difference (95% CI): −10 (−38 to 19)

Worst pain 6 months I: 49 (45;53) C: 37 (34;39) Adjusted mean difference (95% CI):-−11 (−18 to 5)

Worst pain 24 months I: 35 (1;69) C: 24 (15;33) Adjusted mean difference (95% CI):−11 (−46 to 25) |

|

|

Saad, 2018 |

Type of study: 4arm, randomized controlled assessor-blinded trial

Setting and country: university campus Ribeirão Preto Medical School, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study received financial support of The State of São Paulo Research Foundation --- FAPESP (process number: 2010-/12561-9).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Female recreational athlete, defined as participating in aerobic or athletic activity at least 3 times per week for at least 30 min and had anterior knee pain with a minimum intensity of 3 or greater on the 10-cm VAS for at least three months before the study assessment. insidious onset of symptoms; retropatellar or peripatellar pain with at least 2 of the following activities (ascending/descending stairs, running, kneeling, squatting, prolonged sitting or jumping). Exclusion criteria: previous history of knee surgery; history of back, hip, or ankle joint injury or pain; (3) patellar instability; (4) lesion or pain during palpation or test of any structure of knee and (6) any neurological involvement that would affect gait

N total at baseline: Quadriceps group: 10 Hip group: 10 Stretching group: 10 Control group: 10

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: Quadriceps group: 23.2±2.53 Hip group: 22.5±1.08 Stretching group: 21.3±1.16 Control group: 23.2±1.03

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Quadriceps group The exercises in this group focused specifically on quadriceps strengthening 1.Bike – 15 min. warmup 2.Straight Leg Raise – 3x 10 repetitions with ankle weights resistance*. 3.Seated knee extension (open kinetic chain exercise, 90º – 60º of knee flexion) – 3x 10 repetitions with resistance*. 4.Leg Press (closed kinetic chain exercise, 0º – 45º of knee flexion) – 3x 10 repetitions with resistance*. 5.Wall Slide Squat at 90 º - 3 sets of 1 minute

Hip group This group performed exercises to strengthen hip stabilizing muscles 1.Bike – 15 minutes warmup 2.Straight Leg Raise inside lying– 3x 10 repetitions using ankle weights as resistance*. 3.Supine Bridge on Ball Lateral bridge 3x 10 repetitions with 10 second isometric hold on the last repetition 4.Seated Hip Abduction 3x 10 repetitions with resistance*. 5.Strengthening the extensors, abductors, and hip external rotators at four support positions 3x 10 repetitions with ankle weights resistance*.

*Resistance = the weights were increased based on the patient’s reports on the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale based on Borg's Scale of Effort.

Stretching group In this group, the physical therapist monitored and stabilized the patients during the stretching exercises for all muscles involved in knee and hip stabilization: 1.Quadriceps stretching (standing/lying position) 2.Hamstrings stretching (supine position/seated position) 3.Gastrocnemius and soleus stretching (with assistance of ramp/standing position) 4.External rotators of hip and iliotibial band stretching 5.Flexors of hip stretching (on the floor/with assistance of the therapist) 6.Aductors stretching 7.Abdominal stretching All exercises: 3x 30s stretches |

Patients included in this group did not have any kind of intervention for eight weeks, but they were tested at the start of the program & at the end like the other 3 groups. |

Length of follow-up: 8 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Quadriceps group: 1 (10%) Hip group: 0 Stretching group: 0 Control group: 0 Reasons: n.r.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain Quadriceps group: 0.56±0.89 Hip group: 0.55±0.8 Stretching group: 0.14±0.25 Control group: 3.69±0.6

AKPS Quadriceps group: 90.11±6.11 Hip group: 91.8±5.67 Stretching group: 91.0±6.62 Control group: 81.9±8.41 |

|

n.r.= not reported, VAS: visual analog scale

- of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Van der Heijden, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, for included studies

For future updates of the review, we will explore the possibility of publication bias using a funnel plot if there are data from at least 10 trials available for pooling |

Yes

None declared |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: Wat is de waarde van oefentherapie bij patiënten met patellofemorale pijn?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Hott, 2019/ Hott, 2020 |

The randomization sequence was computer generated with blocks of a variable size, stratified by sex, and unknown to anyone in the research team. The sequence was concealed in opaque envelopes, stored by a nurse not otherwise involved in the study, and delivered sequentially to the study physiotherapist at randomization. |

Unlikely |

Unclear

Patients in the control group were lost to follow up since they were dissatisfied with the allocation |

Unlikely

Physiotherapists providing the interventions were blinded to baseline measures. |

Unlikely

Members of the research team who handled outcome measures were blinded to treatment allocation. Data analysis and writing of the manuscript were performed blinded until consensus about the interpretation was reached |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unlikely

The principle of intention to treat was used in the main analysis. |

|

Rathleff, 2015 |

The four schools were randomised either to patient education or patient education and exercise therapy using a computergenerated sequence developed by the main investigator (MSR). Cluster randomisation was chosen to minimise the contamination between individuals, which could occur if more than one adolescent in each class were diagnosed with PFP but randomised to different treatment groups. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unclear

The first author and a statistician not involved in the study performed all analyses. They were not blinded to group allocation during the analyses.

|

Unlikely |

Unclear

Follow-up rate ranged from 73% to 91% with a 91% follow-up rate at the primary endpoint at 12 months. |

Unlikely |

|

Saad, 2018 |

The subjects were randomly allocated to one of four groups: quadriceps strengthening group (QG), hip strengthening group (HG), stretching group (SG) or a control group(CG) (no treatment). The randomization schedule was generated using R 2.7.2 statistical software. The allocation was concealed by the use of consecutively numbered, sealed and opaque envelopes. |

Unlikely

|

Unlikely |

Unclear

One provider treated all groups |

Unlikely

Assessor was blinded |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Alba-Martin 2015 |

Review zonder meta-analyse van de 10 geïncludeerde RCTS, alleen beschrijvende resultaten |

|

Ashraf 2017 |

Taal Persisch (RCT) |

|

Azahin 2016 |

RCT: controlegroep krijgt knieoefeningen |

|

Bolgla 2005 |

Review zonder meta-analyse |

|

Bolgla 2016 |

RCT: knierevalidatie voor controlegroep |

|

Clijsen 2014 |

Review met meta-analyse, overlapt grotendeels overlap met van der Heijden 2015 |

|

Drew 2017 |

feasibility study |

|

Ferber 2015 |

Knierevalidatie in RCT-controlegroep |

|

Foroughi 2019 |

Interventie en control groep in RCT ontvangen kracht en stretchoefeningen |

|

Frye 2012 |

Inclusie van zowel RCT’s, cohorten en observationele studies in reviews |

|

Heijntjes 2003 |

Cochrane review is geüpdatet door van der Heijden 2015 |

|

Karakuay 2014 |

Taal Turks (RCT) |

|

Kooijker 2014 |

Overlap geïncludeerde studies in deze review met Heijden 2015 |

|

Lun, 2005 |

Controlegroep ontvangt een brace |

|

Rabelo 2017 |

Controlegroep in RCT krijgt krachtoefeningen voor heup en knie |

|

Rogan 2019 |

Review includeerde 3 RCT’s >2014 geïncludeerd die ook uit de search van deze module komen |

|

Saltychev 2008 |

Review zonder meta-analyse |

|

Sharif 2002 |

Controlegroep in RCT krijgt conventionele fysiotherapie (included 10 minutes ultrasonic therapy at pulsed mode, quadriceps strengthening, and active short act extension exercises and proprioception training five days a week) |

|

Shetty 2016 |

Controlegroep in RCT krijgt conventionele fysiotherapie en studie gaat over sedentaire populatie |

|

Soleimani 2017 |

Taal Persich (RCT) |

|

Taylor, 2003 |

Pilot studie met <20 patiënten |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 09-05-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 25-01-2022

|

Module[1] |

Regiehouder(s)[2] |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn[3] |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit[4] |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit[5] |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling[6] |

|

Oefentherapie patellofemorale pijn |

VSG |

2022 |

2027 |

1x per 5 jaar |

VSG |

- |

[1] Naam van de module

[2] Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

[3] Maximaal na vijf jaar

[4] (half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

[5] regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

[6] Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Deze richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie

- Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie

- Nederlandse Vereniging van Podotherapeuten

- Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Arbeids- en Bedrijfsgeneeskunde

De richtlijn is goedgekeurd door:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland (en ReumaNederland)

Het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap heeft een verklaring van geen bezwaar afgegeven.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met anterieure kniepijn.

Werkgroep

- Dr. S. van Berkel, sportarts, Isala Zwolle, VSG (voorzitter)

- Dr. M. van Ark, fysiotherapeut, bewegingswetenschapper, Hanzehogeschool Groningen, Peescentrum ECEZG, KNGF

- Drs. G.P.G. Boots, bedrijfsarts, zelfstandig werkzaam, NVAB

- Drs. S. Ilbrink, sportarts, Jessica Gal Sportartsen en Sport- en Beweegkliniek, VSG

- Dr. S. Koëter, orthopedisch chirurg, CWZ, NOV

- Dr. N. Aerts-Lankhorst, waarnemend huisarts, NHG

- Dr. R. van Linschoten, sportarts, zelfstandig werkzaam, VSG

- Bsc. L.M. van Ooijen, (sport)podotherapeut en manueel therapeut, Profysic Sportpodotherapie, NVvP

- MSc. M.J. Ophey, (sport)fysiotherapeut, YsveldFysio, KNGF

- Dr. T.M. Piscaer, Orthopedisch chirurg-traumatoloog, Erasmus MC, NOV

- Drs. M. Vestering, radioloog, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, NVvR

Met methodologische ondersteuning van

- Drs. Florien Ham, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. Mirre den Ouden - Vierwind, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. Saskia Persoon, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. Miriam van der Maten, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Ilbrink |

Sportarts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Ooijen |

Sportpodotherapeut bij Profysic Sportpodotherapie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Linschoten |

Sportarts, zelfstandig werkzaam |

Hoofdredacteur Sport&Geneeskunde |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|