Oefentherapie bij patella tendinopathie (PT)

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale vorm van oefentherapie bij patiënten met patella tendinopathie?

Aanbeveling

Adviseer de patiënt als basis voor de behandeling van patella tendinopathie oefentherapie (actieve behandeling) gedurende twaalf weken, bij voorkeur (deels) onder begeleiding van de fysio- of oefentherapeut.

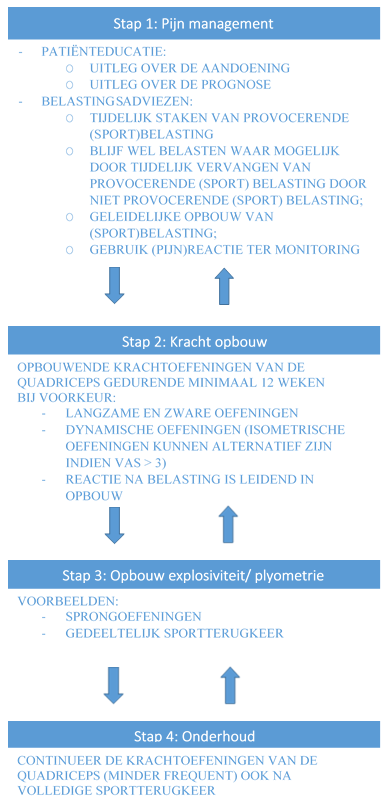

Gebruik een stappenplan (zie figuur 1) bij de behandeling van patiënten met een patella tendinopathie:

- Pijn management:

- Patiënteducatie (mondelinge en schriftelijke educatie).

- Belastingsadviezen. - Kracht opbouw:

Opbouwende krachtoefeningen van de quadriceps gedurende minimaal 12 weken. De vorm van oefentherapie dient te worden afgestemd met de individuele patiënt. De voorkeur gaat uit naar langzame en zware oefeningen waarbij afhankelijk van de reactie van de kniepees gekozen kan worden voor een of meerdere contractievormen. - Opbouw explosiviteit/ plyometrie:

Afhankelijk van type sportbeoefening kan in aansluiting worden gestart met een geleidelijke opbouw van explosieve/ plyometrische activiteiten. - Onderhoud bestaande uit krachtoefeningen van de quadriceps.

Overweeg eventueel aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen bij onvoldoende progressie na patiënteducatie, belastingsadviezen en twaalf weken structurele oefentherapie (zie de module Aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen PT).

Figuur 1 Stappenplan behandeling patiënten patella tendinopathie

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Oefentherapie wordt in de klinische praktijk het meest toegepast als behandeling voor patella tendinopathie. Diverse studies (zie bijvoorbeeld Kjaer, 2009; Rudavsky, 2014; Van Rijn, 2019) bevestigen het belang van oefentherapie en ook bij andere tendinopathieën is de meeste evidentie aanwezig voor een actieve behandeling. Daarnaast worden studies naar het effect van andere behandelingen vrijwel altijd gecombineerd met oefentherapie. Oefentherapie wordt daarom ook door de werkgroep gezien als hoeksteen van de behandeling van patella tendinopathie. Het doel van deze uitgangsvraag was om te achterhalen wat de optimale vorm van oefentherapie is op basis van de huidige literatuur op dit gebied.

Er werden vijf gerandomiseerde studies gevonden die naar de effectiviteit van de verschillende vormen van oefentherapie ten opzichte van elkaar hebben gekeken. De studiepopulaties in de gevonden studies zijn erg klein, waardoor er weinig uitspraken gedaan kunnen worden over de effectiviteit van de verschillende interventies. Derhalve kunnen er op basis van de literatuur geen sterke aanbevelingen worden geformuleerd over het effect van de verschillende oefentherapievormen ten opzichte van elkaar.

De werkgroep probeert in onderstaande overwegingen uiteen te zetten hoe het tot de aanbevelingen is gekomen. De effectiviteit, veiligheid, kosten, tijd die de patiënt in de behandeling moet investeren en beschikbaarheid van de behandeling zijn hierin meegenomen. Hierbij dient er rekening mee te worden gehouden dat het voorschrijven van oefentherapie geen ‘one size fits all recept’ is; dit komt bijvoorbeeld door variaties in het stadium van patella tendinopathie (reactief of degeneratief (Cook, 2016)), verschillen in de kinetische keten bij patiënten en de omvang en intensiteit van sportbeoefening en/of werkbelasting. Dit maakt oefentherapie ook lastig te onderzoeken, mede omdat waarschijnlijk meerdere oefeningen in de opbouw worden toegepast en het tijdspad per individu zal verschillen. In de beschreven studies gaat het veelal om de chronische, degeneratieve vorm van patella tendinopathie.

De opbouw van oefentherapie kan volgens de werkgroep worden vormgegeven door gebruik te maken van het volgende stappenplan gebaseerd op Rudavsky (2014): 1. Pijn management, 2. Kracht opbouw, 3. Opbouw explosiviteit/plyometrie, 4. Onderhoud.

1. Pijn management

Op basis van klinische expertise adviseert de werkgroep om patiënteducatie en belastingsadviezen te overwegen als basis van de behandeling van patella tendinopathie. De werkgroep is van mening dat patiënteducatie bijdraagt aan een adequaat verwachtingsmanagement en plannen van meer realistische doelstellingen. De belastingsadviezen hebben als belangrijk doel om de patiënt zelfbewuster en zelfredzamer te maken.

Effecten van patiënteducatie worden vaak onderbelicht. Recent onderzoek bij patiënten met gluteus medius tendinopathie laat zien dat patiënteducatie in combinatie met oefentherapie effectiever is dan een afwachtend beleid of een injectie met corticosteroïden (Mellor, 2018). Patiënteducatie voor patiënten met patella tendinopathie heeft volgens de werkgroep 3 elementen: uitleg over de aandoening, uitleg over de prognose en pijneducatie. Concreet houdt dit in dat er wordt uitgelegd dat het een overbelastingsblessure betreft met vaak langdurige klachten als gevolg. Daarnaast kunnen de klachten een terugkerend karakter hebben, vooral indien de specifieke provocerende (sport- en/of werk-) belasting wordt gecontinueerd. Pijneducatie houdt in dat zorgverleners hun kennis over pijn delen met de patiënt. Dit omvat uitleg van de neurofysiologie van acute en chronische pijn (inclusief centrale sensitisatie). In de vroege fase van een reactieve tendinopathie kan er nog sprake zijn van een acute (fysiologische) pijn, terwijl in de chronische fase de pijn pathologisch (dysfunctioneel) kan zijn (Rio, 2014). Naast lichamelijke factoren komt er steeds meer aandacht voor de invloed van psychosociale aspecten op langdurige pijnklachten. Relatieve rust kan kortdurend waarschijnlijk de pees beschermen in de vroege (reactieve) fase van de tendinopathie. Echter, factoren zoals angst voor het ontstaan van meer schade of een volledige ruptuur, bewegingsangst en catastroferen van de klachten, kunnen vooral bij langer bestaande klachten het herstel negatief beïnvloeden. Bij de aanwezigheid van dit soort factoren kan pijneducatie effectief zijn in het verbeteren van ervaren gezondheid en verminderen van de zorgconsumptie. Dit is voornamelijk bij patiënten met lage rugpijn onderzocht, maar nog niet bij patiënten met patella tendinopathie (Louw, 2014).

Binnen het stadium pijn management speelt advies over belasting en belastbaarheid van de patellapees volgens de werkgroep een belangrijk rol. Het tijdelijke staken of vervangen van provocerende (sport- en of werk) belasting door niet-provocerende (sport- en of werk) belasting staat hierbij centraal om de pijnklachten op korte termijn te verminderen, waarna deze op basis van de (pijn)reactie (VAS van 5 (0 tot 10) of lager) weer geleidelijk kan worden opgebouwd (Silbernagel, 2007). Hierbij is het belangrijk beweging te blijven stimuleren, maar zo veel mogelijk een toename van de klachten te vermijden. Hoewel dit een geaccepteerde methode van revalidatie is bij tendinopathieën (Davenport, 2005), is het effect hiervan niet in gerandomiseerde studies onderzocht.

Een snelle tijdelijke staking van provocerende (sport- en/of werk-) belasting kan in het geval van een reactieve patella tendinopathie mogelijk al voldoende zijn voor een snelle sport- en of werkterugkeer.

Op korte termijn (tot 45 minuten na een oefensessie) zouden zware isometrisch contracties mogelijk pijn verminderend kunnen werken (Rio, 2017). Deze resultaten zijn echter niet gerepliceerd in een latere studie, die wel een kleine verbetering in pijn vonden, maar geen verschil zagen tussen zware isometrische oefeningen of zware dynamische oefeningen (heavy slow resistance) (Holden, 2019). Ook bij andere tendinopathieën is het bewijs voor isometrische oefeningen tegenstrijdig, waarbij er geen beter effect ten opzichte van isotone oefeningen lijkt te zijn (Clifford, 2020). Aangezien de eerste studies naar zware isometrische oefeningen op dit moment tegenstrijdige resultaten laten zien, is de werkgroep van mening dat dit, indien hier op individuele basis een goede reden voor is (bijvoorbeeld voorafgaand aan een belangrijke wedstrijd), op basis van trial and error kan worden toegepast. Isometrische oefeningen hoeven niet als standaard zorg te worden toegepast.

2. Kracht opbouw

Na de eerste pijnmanagementfase (welke gedurende de revalidatie gecontinueerd zal worden), volgt een fase gericht op opbouw van kracht. De werkgroep adviseert wanneer mogelijk direct te starten met een vorm van krachtoefeningen voor de quadriceps. Het blijft ingewikkeld om de verschillende interventies (oefeningen, duur, intensiteit) die zijn onderzocht in de verschillende studies en geëvalueerd met verschillende uitkomstmaten samen te vatten. Op basis van de huidige literatuur kunnen geen sterke aanbevelingen worden geformuleerd over wat de optimale vorm van oefentherapie is. Oefenvormen die kunnen worden toegepast zijn excentrische, isotonische (concentrisch en excentrisch) en isometrische oefeningen. Een overeenkomst binnen de onderzochte programma’s lijken oefeningen met een langzame en zware belasting van de quadriceps te zijn. Gezien de resultaten kan er niet een contractievorm boven een andere worden geplaatst. Dit komt overeen met eerdere reviews die de studies van meerdere tendinopathieën op een rij hebben gezet (Couppe, 2015; Malliaras, 2013). Zij geven ook aan dat de eerder superieur geachte excentrische oefeningen op dit moment geen meerwaarde lijken te hebben boven concentrische oefeningen van dezelfde intensiteit. Dit wordt eveneens bevestigd in een recent gepubliceerde RCT (Breda, 2021). Deze RCT laat een beter resultaat op de VISA-P van een opbouwend oefenprogramma (met VAS pijn ≤ 3) ten opzichte van een dagelijks provocatief excentrisch trainingsprogramma zien. Omdat de resultaten na 29 maart 2020 zijn gepubliceerd en zodoende niet in de zoekstrategie zijn geïdentificeerd, kan deze studie alleen in de overwegingen worden meegenomen. De werkgroep adviseert daarom in deze fase te kiezen voor langzame en zware oefeningen waarbij afhankelijk van de reactie van de kniepees gekozen kan worden voor een of meerdere contractievormen. Gebaseerd op de klinische ervaring van de werkgroep hebben dynamische oefeningen hierbij de voorkeur indien deze getolereerd worden (pijn tijdens en na afloop van de oefeningen VAS ≤ 3). Isometrische oefeningen kunnen een alternatief zijn in het geval van een pijnscore hoger dan drie punten (0 tot 10) bij het doen van dynamische oefeningen. Zowel Frohm (2007), als Visnes (2005) adviseerden extra gewicht toe te voegen bij een VAS van 3 (0 tot 10) of lager. De ervaring van de werkgroep is dat isometrische oefeningen bij een deel van de patiënten minder pijn provoceren. Bij de oefeningen waar een éénbenige uitvoering mogelijk is, adviseert de werkgroep dit te doen om compensatie door het andere been te voorkomen. De studie van Kongsgaard (2009) heeft aangetoond dat patiënten die drie keer per week een oefensessie (HSR) moesten doen meer tevreden waren over de behandeling dan patiënten die het Alfredson protocol (dagelijks oefenen) volgden, ondanks dat er geen verschil in pijnscore werd waargenomen. Mede gelet op de therapietrouw geeft de werkgroep derhalve de voorkeur aan een programma (met een langzame en zware belasting van de quadriceps) waarbij er drie keer per week wordt geoefend. Een eenduidige definitie van “langzaam en zwaar” bestaat nog niet, de werkgroep adviseert als richtlijn op basis van de bestaande studies en ervaring om de concentrische en excentrische onderdelen van de oefening beide 3 tot 4 seconden te laten duren (Kongsgaard, 2010; Van Ark, 2016) rond het 8 Repetition Maximum (Kongsgaard, 2010; Van Ark, 2016). Er is meer onderzoek nodig om dit advies verder te kunnen onderbouwen.

Een goede afstemming tussen oefentherapie en sportbeoefening/werkbelasting lijkt wel van belang. De oefentherapievorm speelt hierbij een rol. De meeste van de eerste (pilot) studies naar het bekendste excentrische single leg decline squat protocol (Alfredson) laten zien dat deze provocatieve oefeningen alleen effect hebben wanneer patiënten ook stoppen met sportparticipatie (Visnes, 2006; Jonsson, 2005; Young, 2005; Purdam, 2004).

Ook liet een studie die dit protocol preventief toepaste bij een groep voetballers in voorbereiding op het seizoen zien dat in geval van al aanwezige afwijkingen op echobeelden het risico op een patella tendinopathie juist toeneemt (Fredberg, 2007). Gezien de provocatieve belasting van het single leg decline squat protocol (Alfredson protocol, Young, 2005) adviseert de werkgroep dit niet te combineren met (volledige) sportbeoefening.

Ondanks de zeer lage bewijslast kan in aanvulling op de krachtoefeningen in individuele gevallen, met name wanneer er sprake is van een verkorting van de hamstrings, quadriceps en musculus triceps surae, stretching worden overwogen (Sprague, 2018; Stasinopoulos, 2012).

In de praktijk wordt bij het inrichten van oefentherapie ook aandacht geschonken aan de kinetische keten en eventuele aanpak van lacunes hierin. De kinetische keten is het geheel van spieren en gewrichten in het hele lichaam, waarbij verschillende spieren/gewrichten invloed uitoefenen op elkaar. Een zwakte in een andere spier/gewricht kan mogelijk verklarend zijn voor het ontstaan van een patella tendinopathie. Er is slechts beperkt onderzoek gedaan naar risicofactoren in de kinetische keten voor het ontstaan van een patella tendinopathie. Er zijn geen gepubliceerde onderzoeken naar de effectiviteit van correcties op de kinetische keten bij een patella tendinopathie. De werkgroep heeft dit daarom niet opgenomen in de aanbevelingen.

3. Opbouw explosiviteit/ plyometrie

De werkgroep adviseert een geleidelijke opbouw van explosieve/ plyometrische activiteiten gedurende de revalidatie, zoals ook gepostuleerd door Rudavsky (2014) en Breda (2021). Voorbeelden hiervan zijn springen en snelle richtingsveranderingen. Deze activiteiten worden gezien als meest belastend voor de kniepees. Zoals eerder genoemd, is de balans tussen belasting en belastbaarheid van belang in de opbouw. Afhankelijk van de (pijn)reactie op explosieve (sport)activiteiten dient dit eerder of later in de revalidatie te worden opgebouwd. Hierbij kan gedacht worden aan opbouw door middel van sprongoefeningen, maar ook aan een (gedeeltelijke) sportterugkeer. In de opbouw van deze activiteiten zal de mate van pijn tijdens en na de oefeningen steeds leidend zijn in de progressie (een pijnscore VAS van drie of minder kan worden geaccepteerd). Afhankelijk van de benodigde capaciteit voor de patiënt (een topsporter in een explosieve sport heeft veel meer capaciteit nodig dan een recreatieve sporter in een niet explosieve sport) dient meer of minder aandacht aan deze fase te worden besteed.

4. Onderhoud

De werkgroep is op basis van klinische ervaring van mening dat na volledige terugkeer in de sport of het werk, de patiënt geadviseerd moet worden om (minder frequent) krachttraining van de quadriceps te blijven doen en daarnaast rekening te blijven houden met de belasting van de kniepees door snelle toenames in belasting te voorkomen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Om meer inzicht te krijgen in de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten met patella tendinopathie is er in samenwerking met Patiëntenfederatie Nederland een vragenlijst opgesteld en uitgezet.

Alle patiënten (n=9) die de vragenlijst hebben ingevuld, hebben een vorm van oefentherapie gehad. De belangrijkste doelen voor de patiënt waren om weer pijnvrij de dagelijkse activiteiten te kunnen uitoefenen en pijnvrij te kunnen sporten, bij voorkeur op het oude niveau.

De werkgroep adviseert oefentherapie (deels) onder begeleiding van een fysio- of oefentherapeut. Genoemd voordeel is onder andere het toezicht op een juiste uitvoering van de oefeningen, waardoor op een veilige en verantwoorde manier de belasting verder kan worden uitgebreid of tijdig kan worden ingegrepen bij een dreigende overbelasting. Daarnaast speelt therapietrouw een belangrijke rol wanneer het gaat om de kans op herstel. Uit de ingevulde vragenlijst komt naar voren dat shared-decision-making een gunstige invloed heeft op de therapietrouw, er is hierover nog weinig bekend in de wetenschappelijk literatuur (Joosten, 2008; Tousignant-Laflamme, 2017). Verder adviseert de werkgroep om in samenspraak met de patiënt het oefenprogramma regelmatig en op gestructureerde wijze (VAS en VISA-P) te evalueren. Overleg tussen zorgverleners, en dan met name de afstemming tussen arts en fysio- of oefentherapeut, wordt door de patiënt als zeer waardevol ervaren.

Genoemde nadelen zijn de tijdsinvestering (meerdere keren per week oefenen) en de duur tot verbetering/herstel. Bekend is dat de behandeling van patella tendinopathie over het algemeen veel geduld en een geïntegreerde aanpak vergt. Het is belangrijk dat de arts/fysio- of oefentherapeut en de patiënt onderkennen dat bij een tendinopathie die al maanden bestaat soms een lange revalidatieperiode nodig is voordat de klachten zijn verdwenen. De eerdergenoemde patiënteducatie met uitleg over de aandoening en de prognose speelt hierbij een belangrijke rol. De werkgroep is van mening dat mondelinge informatie goed kan worden ondersteund door een andere vorm van informatie, bijvoorbeeld een informatiefolder of relevante informatie op betrouwbare internetbronnen (bijvoorbeeld www.thuisarts.nl en www.sportzorg.nl).

In geval van een patella tendinopathie is de beschikking tot (medische) fitness wenselijk in de uitvoering van oefentherapie. De werkgroep is van mening dat oefentherapie met behulp van fitnessapparatuur, met name voor patiënten die willen terugkeren naar een explosieve sport, de voorkeur heeft boven een thuisoefenschema. Fitnessapparatuur maakt het mogelijk om de belasting geleidelijk op te voeren en de quadriceps beter te isoleren (met behulp van leg extension apparaat of een leg press apparaat), zodat compensatie door andere spiergroepen wordt voorkomen. Overigens is niet bij elke oefensessie fysiotherapeutische begeleiding noodzakelijk. Patiënten die niet sporten of recreatieve sporters die een niet-explosieve sport beoefenen kan, uit kostenoverweging, een thuisoefenschema worden aangeboden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen studies uitgevoerd naar de (kosten)effectiviteit van het geven van patiënteducatie, belastingsadviezen en adviseren en begeleiden van oefentherapie. Bij oefentherapie voor patiënten met patella tendinopathie wordt geadviseerd dit deels onder begeleiding van de fysio- of oefentherapeut uit te voeren. Het is waarschijnlijk dat patiënten waarbij risicofactoren (bijvoorbeeld genetisch profiel en hypercholesterolemie) aanwezig zijn en hoge functie-eisen (bijvoorbeeld terugkeer naar een explosieve sport) meer contacten met de fysio- of oefentherapeut hebben dan patiënten met een gunstiger prognostisch profiel en lagere functie-eisen. De directe kosten voor fysiotherapeutische begeleiding zijn voor de patiënt. Indien de patiënt over een aanvullende zorgverzekering beschikt en de fysio- of oefentherapeut gecontracteerde zorg levert, zal de begeleiding ten laste van de aanvullende zorgverzekering zijn. In de afgelopen jaren is de omvang van fysiotherapeutische begeleiding vanuit de aanvullende zorgverzekering sterk afgenomen, waardoor het door de zorgverzekering vergoedde contact vaak beperkt is tot zes of negen behandelingen. Bij patiënten met een gunstig prognostisch profiel en lagere functie-eisen kan dit middels een combinatie van gerichte oefentherapie onder begeleiding van de fysio- of oefentherapeuten zelfstandig uitgevoerde oefentherapie (thuis of in de sportschool) voldoende zijn. Bij patiënten met een ongunstig prognostisch profiel en hogere functie-eisen zijn zes of negen behandelingen over het algemeen onvoldoende. Patiënten moeten in deze situatie de fysiotherapeutische zorg zelf betalen. Daarnaast zal een patiënt de mogelijk aanvullende medische fitness of het sportschoolabonnement zelf moeten betalen. Dit zal in de praktijk vaak tot niet-optimale zorg en uitblijven van therapie-effecten leiden, omdat niet elke patiënt over de financiële middelen beschikt om dit te bekostigen. Dit is een onwenselijke situatie.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De volgende factoren zouden van invloed kunnen zijn op de implementatie van de aanbevelingen:

- Oefentherapie voor patiënten met patella tendinopathie wordt (deels) onder begeleiding van de fysio- of oefentherapeut uitgevoerd. Fysiotherapie/oefentherapie wordt niet vanuit de basisverzekering, maar vanuit de aanvullende verzekering vergoed. Het aantal vergoede behandelingen verschilt per zorgverzekeraar en type aanvullende verzekering. Patiënten zonder een aanvullende verzekering of met een beperkt aantal vergoede behandelingen, zullen (een gedeelte) zelf moeten betalen.

- De kosten voor eventuele medische fitness of een sportschoolabonnement komen eveneens voor rekening van de patiënt.

- Therapietrouw speelt een belangrijke rol wanneer het gaat om de kans op herstel, omdat de patiënt gedurende langere tijd onder begeleiding dan wel zelfstandig oefeningen moet uitvoeren. In de context van oefentherapie bij patella tendinopathie kunnen de volgende factoren van invloed zijn op de therapietrouw; educatie van patiënten over de reden voor oefeningen en doseringen, tijdsbestek waarover effecten verwacht kunnen worden en de mogelijke toename van anterieure kniepijn door de oefentherapie (verwachtingsmanagement).

Voor het verstrekken van volledige en gestandaardiseerde informatie en educatie omtrent de aandoening en de advisering en uitvoering van oefentherapie is het wenselijk dat er overeenstemming is tussen de verschillende zorgverleners. Voor de Nederlandse situatie, waar veel disciplines betrokken zijn bij de behandeling van patella tendinopathie, is nadere uitwerking daarvan waarschijnlijk bevorderlijk voor de implementatie

De werkgroep is van mening dat er voldoende geschoolde zorgverleners (o.a. fysio- of oefentherapeut) en sportscholen beschikbaar zijn voor een succesvolle implementatie van de aanbevelingen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Het beperkte aantal studies van relatief lage kwaliteit maken een aanbeveling voor een specifiek oefenprogramma niet mogelijk. Daarbij zorgen individuele verschillen ervoor dat de behandeling van patella tendinopathie niet een ‘one size fits all recept’ is. Mede doordat de belasting van de kniepees een belangrijke rol speelt bij een patella tendinopathie zijn patiënteducatie en belastingsadviezen cruciaal; door dit toe te passen kan een patiënt zijn belasting beter “managen”. Gezien de patiënt tevredenheid ten opzichte van een dagelijks oefenprogramma en er eerder een provocatie is te verwachten bij toepassing van het Alfredson protocol, gaat de voorkeur uit naar oefentherapie met langzame en zware oefeningen (3x per week). Bij het opstellen van de aanbevelingen is rekening gehouden met de (beperkt) beschikbare literatuur en klinische ervaring van de werkgroep.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Patella tendinopathie is een blessure die langdurig klachten kan geven en moeilijk te behandelen is. In de praktijk worden veel verschillende soorten behandelingen toegepast. Voor een behandeling door middel van oefentherapie is de meeste evidentie en indien een andere vorm van behandeling wordt ingezet, wordt deze praktisch altijd gecombineerd met oefentherapie. Er is echter nog onduidelijkheid over de exacte invulling van oefentherapie, waarbij niet elke vorm per definitie tot verbetering leidt.

Knelpunten:

- Er is onvoldoende kennis over de effectiviteit van de verschillende vormen van oefentherapie ten opzichte van elkaar. Mede hierdoor is er veel praktijkvariatie.

- Er is onvoldoende kennis over de FITT (Frequency, Intensity, Type, Time) factoren. Mede hierdoor wordt een revalidatieprogramma vaak te snel opgebouwd of te snel gestaakt.

- De revalidatie/oefentherapie stopt vaak wanneer weer met trainen/werken wordt begonnen in plaats van het continueren van dit programma tijdens de opbouw.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Pain (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect of different training types (eccentric, isometric, and isotonic/ heavy slow resistance) is over one another on pain.

Sources: (Frohm, 2007; Kongsgaard, 2009; Van Ark, 2016; Visnes, 2005) |

2. Function (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect of different training types (eccentric, isometric, and isotonic/ heavy slow resistance) is over one another on function.

Sources: (Frohm, 2007; Kongsgaard, 2009; Stasinopoulos, 2012; Van Ark, 2016; Visnes, 2005) |

3. Return to sport/work (important)

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measure return to sport/ work was not reported in the included studies. |

4. Duration of absenteeism (important)

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measure duration of absenteeism was not reported in the included studies. |

5. Patient satisfaction (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of exercise therapy on patient satisfaction.

Sources: (Kongsgaard, 2009) |

6. Patient recovery (important)

|

Low GRADE |

The outcome measure patient recovery was not reported in the included studies. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Frohm (2007) described a pilot randomized clinical trial (RCT) with 20 athletes with patellar tendinopathy. Athletes were included in the study if they had the clinical diagnosis of patellar tendinopathy verified by MRI or ultrasound imaging, and symptoms for at least 3 months. Participants were randomized in two groups: the group performing eccentric overload training with the Bromsman device (n=11) or the standard eccentric training group using a decline board (n=9). The sessions for both groups consisted of a standardized warming up, eccentric training alternated with trunk and foot stability training and each session was rounded off with stretching exercises of the quadriceps and hamstrings. The eccentric overload training group used the Bromsman device, which consists of a barbell (320 kg) suspended from wires that can be moved up and down along a chosen distance and at a preset speed by a hydraulic machine. The descending distance was individually set from a standing straight position to approximately 110 of knee flexion, and the speed was set to 0.11 m/s. The patients resisted the movement of the barbell using both legs: 4 sets of 4 repetitions (initial set for warm‐up, then maximal effort for next 3 sets). The other group performed unilateral squats on a 25○ decline board with 3 sets of 15 repetitions, and daily home exercises (3 sets of 15 reps/day). If the VAS score was < 3 for a set, the load was increased in 5 kg increments, and if the VAS exceeded > 5, the load was reduced. The principal investigator supervised all the training sessions for all patients in both groups at the clinic. The effectiveness of the training was evaluated with the VISA-P score after 12 weeks. Secondary outcome measures were isokinetic muscle torque, dynamic function and muscle flexibility, as well as pain level estimations using visual analogue scale (VAS).

The RCT of Kongsgaard (2009) consisted of three arms: eccentric decline squat training (n=13), heavy slow resistance training (n=13), and peritendinous corticosteroid injections (n=13). Corticosteroid injections are not included in the current search question, and this study condition is therefore excluded from this summary. The eccentric training group performed three sets of 15 slow repetitions of eccentric unilateral squats on a 25o decline board, twice a day for 12 weeks. Once a week the participants had a supervised training. Load was increased as pain diminished, using a backpack with increasing load. The heavy slow resistance (HSR) training consisted of three weekly sessions, including one supervised session. Every training consisted of four sets of squats, leg press and hack squats. All exercises were performed from extension to 90o knee flexion, and patients were instructed to perform the exercise in 6 seconds per repetition (3s in eccentric phase and 3s in concentric phase). All participants could perform their sporting activities during the intervention period, if these activities could be performed with a maximum VAS-score of 30 (range 0 to 100). All participants performed at least 75% of the sessions, the average compliance in the eccentric group was 89 ± 8% and in the HSR group 91 ± 5%. The effectiveness of the interventions was evaluated after 12 weeks intervention and after six months with the VISA-P and the VAS, further satisfaction was measured as “satisfied” or “not satisfied”.

Stasinopoulos (2012) compared eccentric training and stretching (n=22) with eccentric training alone (n=21). They included patients who had patellar tendinopathy for at least 3 months. The training consisted of unilateral squats on a 25o decline board. The squat was performed at a slow speed in three sets of 15 repetitions. The patients were told to go ahead with the exercise even if they experienced mild pain. When the squat was pain-free, the load was increased by holding weights in their hands. The group with stretching exercises performed static stretching of quadriceps and hamstrings before and after the eccentric training, each stretch lasted 30 seconds and there was a one-minute rest between each stretch. The training was performed five times per week for four weeks and was individualized based on the patient’s description of pain experienced during the training. The effectiveness of the training was evaluated with the VISA-P score after four and 24 weeks.

The randomized clinical trial of Van Ark (2016) described the effects of isometric and isotonic training in jumping athletes with patellar tendinopathy. The isometric group (n=13) used the leg extension machine to perform five sets of 45s isometric contractions of each leg hold at knee angle 60° flexion at 80% MVC. The isotonic group (n=16) used the leg extension machine to perform four sets of eight repetitions, with 3s concentric phase immediately followed by 4s eccentric phase per repetition performed on 80% of 8RM. After performing the exercises for each leg, all participants rested for 15s before continuing with the first leg again. Weight was increased by 2.5% every week if possible. The program was demonstrated (including repetition maximum testing) at the gym where they were going to perform their exercises. Every week participants were followed-up in person or by phone, asking participants if they encountered any problems with the exercise program. The intervention consisted of four sessions per week for four weeks. The median number of sessions performed per week (compliance) in the isometric group was 3 (IQR 2.5 to 3.9) and in the isotonic group was 3 (IQR2.75 to 3.75). The effectiveness of the training was evaluated measuring pain during a single leg decline squat (SLDS) scored on a numeric rating scale (NRS), besides the VISA-P score was used to evaluate pain and function of the knee after four weeks.

Visnes (2005) conducted a RCT with volleyball players with patellar and/or quadriceps tendinopathy for at least three months and a VISA-P score < 80. A total of 29 patients participated, 24 of them had patellar tendinopathy, 2 patients had quadriceps tendinopathy only, and 3 patients had both quadriceps and patellar tendinopathy. The participants were randomized to a training group (n=13) or a control group (n=16). The training consisted of eccentric home exercises (squats) on a 25° decline board. The squat went to 90° of knee flexion, which ensured that the subjects went past 60° of knee flexion, the joint angle thought to place maximal load on the patellar tendon. If pain on the VAS score was < 3 or 4 extra weight was recommended, the load was increased in 5 kg increments, and if VAS exceeded 6 or 7, it was recommended to reduce the load. Only 6 of the 13 players in this group did exercises with an additional external load, and the final load these players reported having used was 4.2 ± 4.9 kg. Patients were followed up by telephone when the training period started, and the training program was described and discussed in detail by the investigators. The training group was instructed to perform the eccentric training program twice a day (14 sessions per week), and the mean value reported was 8.2 ± 4.6 sessions per week. In addition, each player was instructed in person during the first half of the training period (2 to 6 weeks into the program) to ensure proper execution of the program and exercises. The players in the training group were encouraged to continue the eccentric training if they still had knee pain at the end of the 12-week treatment period. The control group did not receive a training intervention, however, both groups received an information package. The effectiveness of the training was evaluated with the VISA-P score 6 weeks after the 12 weeks intervention period and after 6 months, further global knee function and jumping performance were measured.

Results

1. Pain (critical)

Pain was measured by a visual analogue scale (VAS) in the studies of Frohm (2007), Kongsgaard (2009) and Visnes (2005), and by using the numerical rating scale (NRS) in the study of Van Ark (2016). Both tools range from 0 to 10 or 100, where 0 is equal to no pain and 10 or 100 is the worst pain.

Frohm (2007) reported pain after 12 weeks of training. The eccentric overload training group scored a median of 4 (IQR 4 to 6) on the VAS at baseline and a median of 0 (IQR 0 to 1) after 12 weeks (n=11), the standardized eccentric training group scored a median of 5 (IQR 4 to 5) at baseline and a median of 1 (IQR 1 to 2) after 12 weeks (n=9). No between group analyses were performed by Frohm (2007).

Kongsgaard (2009) showed a mean VAS-score of 31 ± 26 in the eccentric group and 19 ± 15 in the HSR group after 12 weeks. After 6 months, the mean VAS-score was 22 ± 17 in the eccentric group and 13 ± 16 in the HSR group. No significant differences were found in the relative improvement of the VAS between baseline and 6 months between the groups.

Visnes (2005) reported a mean VAS-score of 5.1 ± 8.1 during the eccentric training, however no information is provided about the pain levels of the control group.

Van Ark (2016) presented pain during a single leg decline squat. The isometric group scored a median of 6.3 (IQR 5.3 to 7.0) on the NRS at baseline and a median of 4.0 (IQR 2.0 to 5.0) after 4 weeks (n=8), the isotonic group scored a median of 5.5 (IQR 4.0 to 6.0) at baseline and a median of 2.0 (IQR 1.0 to 3.0) after 4 weeks (n=11). There was no statistically significant difference in the NRS pain score change between the groups (p=0.208).

Due to heterogeneity in the studies and interventions it was not possible to pool these data.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome pain started at high as it was based on RCTs but was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The final level is very low.

2. Function (critical)

Pain and function were measured with the VISA-P questionnaire in patients with patellar tendinopathy. The VISA-P ranged from 0 to 100, where a score of 100 means being a completely asymptomatic and fully functioning athlete. This questionnaire was used in all five studies (Frohm, 2007; Kongsgaard, 2009; Stasinopoulos, 2012; Van Ark, 2016; Visnes, 2005).

Frohm (2007) reported the VISA-P score after 12 weeks of training. The eccentric overload training group scored a median of 86 (95%CI: 71 to 92) after 12 weeks (n=11), the standardized eccentric training group scored a median of 75 (95%CI 46 to 83) after 12 weeks (n=9). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups.

Kongsgaard (2009) showed a VISA-P score of 75 ± 3 in the eccentric group (n=12) and 78 ± 18 in the HSR group (n=13) after 12 weeks. After 6 months, the mean VISA-P score was 76 ± 16 in the eccentric group and 86 ± 12 in the HSR group. No statistically significant differences between these groups were reported.

Stasinopoulos (2012) reported the VISA-P after 4 and 24 weeks. The eccentric training group with static stretching (n=22) scored 86 (95%CI: 70 to 94) after 4 weeks, and 94 (95%CI 75 to 100) after 24 weeks. The eccentric training group without stretching (n=21) scored 74 (95%CI 58 to 82) after 4 weeks, and 77 (95%CI 68 to 84) after 24 weeks. The change in the VISA-P scores between groups showed significant more improvement in the eccentric training group with static stretching at 4 weeks and at 24 weeks (p<0.05).

Van Ark (2016) presented a median score of 75.0 (IQR 72.5 to 87.0) after 4 weeks in the isometric group (n=8), and a median score of 79.0 (IQR 67.0 to 86.0) after 4 weeks the isotonic group (n=10). There was no significant difference in VISA-P score change (p=0.965) between the groups.

Visnes (2005) showed no significant differences between the training group (n=13) and the control group (n=16) in the VISA-P score from baseline to 12 weeks (post intervention), further no significant between-group differences were found at 6 weeks (p=0.71) or at 6 months (p=0.99). The VISA-P score at 12 weeks was 70.2 ± 15.4 for the eccentric training group and 75.4 ± 16.7 for the control group.

Due to heterogeneity in the studies and interventions it was not possible to pool these data.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome function started at high as it was based on RCTs but was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The final level is very low.

3. Return to sport/work (important)

Return to sport/work was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome return to sport/work was not assessed due to lack of studies.

4. Duration of absenteeism (important)

Duration of absenteeism was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome duration of absenteeism was not assessed due to lack of studies.

5. Patient satisfaction (important)

Patient satisfaction was described by Kongsgaard (2009). After 12 weeks intervention, 42% (n=5) of the patients in the eccentric training group were satisfied with their clinical outcome and 70% (n=9) of the patients in the HSR group. After 6 months, 22% (n=2) of the patients in the eccentric training group were satisfied, and 73% (n=8) of the patients in the HSR group.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient satisfaction started at high as it was based on a RCT trial but was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The final level is very low.

6. Patient recovery (important)

Patient recovery was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient recovery was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with patellar tendinopathy when compared to other types of exercise therapy or a control group (standard care/ placebo/ wait and see policy) on pain, function, return to sport/ work, duration of absenteeism, patient satisfaction, and patient recovery?

P: patients with patellar tendinopathy (adults).

I: exercise therapy.

C: other type of exercise therapy or control group/ standard care/ placebo/ wait and see policy.

O: pain, function, return to sport/ work, duration of absenteeism, patient satisfaction, and patient recovery.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain and function as critical outcome measures for decision making; and return to sport/ work, duration of absenteeism, patient satisfaction, and patient recovery as important outcome measures for decision making.

For the outcome pain the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) were used. The VISA-P score is a questionnaire developed to measure pain and function in patients with patellar tendinopathy. Return to sport/ work was measured with the Tegner score. Satisfaction with the result of treatment and recovery were usually measured on a Likert scale.

The working group defined a difference of 2 cm (out of 10 cm) on the VAS or 2 points on the NRS score as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference, in line with Crossley (2004). A difference of 13 points on the VISA-P score is seen as a minimal clinically important difference (Hernandez-Sanchez, 2014). A minimal clinically important difference for return to sport/ work, duration of absenteeism, patient satisfaction and patient recovery was not predefined.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Pubmed and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until March 29th, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 316 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of the individual studies available) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included at least 20 patients with patellar tendinopathy, compared exercise therapy with another exercise therapy or a control condition, and included at least one of the defined outcome measures. Nine RCT studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening, seven of these RCT studies were part of a systematic review. The systematic review (Lim, 2018) provided an overview of the effects of isometric, eccentric, and heavy slow resistance (HSR) exercises on pain and function in patients with patellar tendinopathy, however it did not provide a meta-analysis of the included studies. Therefore, the systematic review was excluded. From the seven individual RCTs, three studies were excluded due to the small study population (n< 20) (see exclusion table). One study of two the initially selected RCT studies was excluded because it was written in Spanish (see also the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods).

Results

Five RCT studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Of these five articles, one study was about isometric and isotonic (heavy slow resistance) training (van Ark, 2016), and four studies were about eccentric training (Frohm, 2007; Kongsgaard, 2009; Stasinopoulos, 2012; Visnes, 2005). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence table. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Breda, S. J., Oei, E. H., Zwerver, J., Visser, E., Waarsing, E., Krestin, G. P., & de Vos, R. J. (2021). Effectiveness of progressive tendon-loading exercise therapy in patients with patellar tendinopathy: a randomised clinical trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine;55(9):501-509.

- Cook, J. L., Rio, E., Purdam, C. R., & Docking, S. I. (2016). Revisiting the continuum model of tendon pathology: What is its merit in clinical practice and research? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(19), 1187–1191.

- Couppé, C., Svensson, R. B., Silbernagel, K. G., Langberg, H., & Magnusson, S. P. (2015). Eccentric or concentric exercises for the treatment of tendinopathies?. Journal of Orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 45(11), 853-863.

- Davenport, T. E., Kulig, K., Matharu, Y., & Blanco, C. E. (2005). The EdUReP model for nonsurgical management of tendinopathy. Phys Ther, 85(10), 1093-1103.

- Fredberg, U., Bolvig, L., & Andersen, N. T. (2008). Prophylactic training in asymptomatic soccer players with ultrasonographic abnormalities in Achilles and patellar tendons: the Danish Super League Study. The American journal of sports medicine, 36(3), 451-460.

- Frohm, A., Saartok, T., Halvorsen, K., & Renström, P. (2007). Eccentric treatment for patellar tendinopathy: A prospective randomised shortterm pilot study of two rehabilitation protocols. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(7), e7.

- Holden, S., Lyng, K., Graven-Nielsen, T., Riel, H., Olesen, J. L., Larsen, L. H., & Rathleff, M. S. (2020). Isometric exercise and pain in patellar tendinopathy: A randomized crossover trial. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(3), 208-214.

- Joosten, E. A., DeFuentes-Merillas, L., De Weert, G. H., Sensky, T., Van Der Staak, C. P. F., & de Jong, C. A. (2008). Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 77(4), 219-226.

- Jonsson, P., & Alfredson, H. (2005). Superior results with eccentric compared to concentric quadriceps training in patients with jumper’s knee: a prospective randomised study. British journal of sports medicine, 39(11), 847-850.

- Kjær, M., Langberg, H., Heinemeier, K., Bayer, M. L., Hansen, M., Holm, L.,... & Magnusson, S. P. (2009). From mechanical loading to collagen synthesis, structural changes and function in human tendon. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 19(4), 500-510.

- Kongsgaard, M., Kovanen, V., Aagaard, P., et al. (2009). Corticosteroid injections, eccentric decline squat training and heavy slow resistance training in patellar tendinopathy. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 19: 790–802

- Louw, A., Diener, I., Landers, M. R., & Puentedura, E. J. (2014). Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 39(18), 1449-1457.

- Mellor, R., Bennell, K., Grimaldi, A., Nicolson, P., Kasza, J., Hodges, P.,... Vicenzino, B. (2018). Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. BMJ, 361, k1662.

- O’Neill, S., Radia, J., Bird, K., Rathleff, M. S., Bandholm, T., Jorgensen, M., & Thorborg, K. (2019). Acute sensory and motor response to 45-S heavy isometric holds for the plantar flexors in patients with Achilles tendinopathy. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 27(9), 2765-2773.

- Purdam, C. R., Jonsson, P., Alfredson, H., Lorentzon, R., Cook, J. L., & Khan, K. M. (2004). A pilot study of the eccentric decline squat in the management of painful chronic patellar tendinopathy. British journal of sports medicine, 38(4), 395-397.

- Rio, E., Moseley, L., Purdam, C., Samiric, T., Kidgell, D., Pearce, A. J.,... Cook, J. (2014). The pain of tendinopathy: physiological or pathophysiological? Sports Med, 44(1), 9-23.

- Rio, E., Van Ark, M., Docking, S., Moseley, G. L., Kidgell, D., Gaida, J. E.,... & Cook, J. (2017). Isometric contractions are more analgesic than isotonic contractions for patellar tendon pain: an in-season randomized clinical trial. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 27(3), 253-259.

- Rudavsky, A., & Cook, J. (2014). Physiotherapy management of patellar tendinopathy (jumper's knee). Journal of physiotherapy, 60(3), 122-129.

- Silbernagel KG, Thomeé R, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J. (2007). Continued sports activity, using a pain-monitoring model, during rehabilitation in patients with Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled study. Am J Sports Med.;35(6):897-906.

- Sprague, A. L., Smith, A. H., Knox, P., Pohlig, R. T., & Silbernagel, K. G. (2018). Modifiable risk factors for patellar tendinopathy in athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine, 52(24), 1575-1585.

- Stasinopoulos, D., Manias, P., & Stasinopoulou, K. (2012). Comparing the effects of eccentric training with eccentric training and static stretching exercises in the treatment of patellar tendinopathy. A controlled clinical trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 26(5), 423–430.

- Tousignant-Laflamme, Y., Christopher, S., Clewley, D., Ledbetter, L., Cook, C. J., & Cook, C. E. (2017). Does shared decision making results in better health related outcomes for individuals with painful musculoskeletal disorders? A systematic review. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 25(3), 144-150.

- van Ark, M., Cook, J., Docking, S., Zwerver, J., Gaida, J., van den Akker‐Scheek, I., & Rio, E. (2016). Do isometric and isotonic exercise programs reduce pain in athletes with patellar tendinopathy in‐season? A randomised clinical trial. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 19(9), 702–706.

- van Rijn, D., van den Akker-Scheek, I., Steunebrink, M., Diercks, R. L., Zwerver, J., & van der Worp, H. (2019). Comparison of the effect of 5 different treatment options for managing patellar tendinopathy: a secondary analysis. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 29(3), 181-187.

- Visnes, H., Hoksrud, A., Cook, J., & Bahr, R. (2005). No effect of eccentric training on jumper's knee in volleyball players during the competitive season: A randomized clinical trial. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 16(3), 227–234.

- Young, M. A., Cook, J. L., Purdam, C. R., Kiss, Z. S., & Alfredson, H. (2005). Eccentric decline squat protocol offers superior results at 12 months compared with traditional eccentric protocol for patellar tendinopathy in volleyball players. British journal of sports medicine, 39(2), 102-105.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy - otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question: Wat is de optimale vorm van oefentherapie bij patiënten met patella tendinopathie?

n.r.: not reported, IQR: inter quartile range, MVC: maximal voluntary contraction, RM: repetition maximum

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: Wat is de optimale vorm van oefentherapie bij patiënten met patella tendinopathie?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Frohm, 2007 |

The patients were allocated to either of the two treatment groups by random draw of a sealed, opaque envelope that contained the group assignment. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely

All patients were examined, trained and tested by the principal investigator (AF), except for the range of motion examinations, which were assessed by two other physiotherapists. |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Kongsgaard, 2009 |

A computer-generated minimization randomization procedure was used. The minimization randomization procedure was performed according to activity level, symptom duration and age. |

Unlikely |

Unclear

Participants applied for trial submission, self-selection following advertisement |

Unclear |

Unclear

The ultrasound and MRIs are conducted by a blinded investigator, however, it is not clear if the other outcomes were blinded evaluated. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Stasinopoulos, 2012 |

Patients were allocated to two groups by sequential, alternate allocation: the first patient was assigned to the eccentric training and static stretching exercises group, the second to the eccentric training group, and so on. |

Likely |

Unclear

All patients received a written explanation of the trial before entry into the study and then gave signed consent to participate |

Unclear |

Unlikely

All assessments were conducted by PM who was blind to the patients’ therapy group |

Unlikely |

Unlikely

There were no dropouts |

Unlikely |

|

Van Ark, 2016 |

Participants were randomised to an exercise program by the draw of a sealed opaque envelope from 40 identical envelopes that were randomised using a randomisation table created by computer software |

Unlikely |

Unlikely

Participants were not blinded, however it seems unlikely that it lead to bias |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Unclear |

|

Visnes, 2005 |

Randomization by a statistician who was blinded to player identity. Players from the same teams were randomized in blocks to different groups. (32 teams) |

Unlikely |

Unclear

Blinding subjects to group allocation was not possible. |

Likely

Participants were followed up by telephone when the training period started, and the training program was described and discussed in detail by 2 of the investigators (H.V. and A.H.). In addition, each player was instructed in person during the first half of the training period (2–6 weeks into the program) to ensure proper execution of the program and exercises. |

Unclear

Self-recorded by subjects. Weekly diary mailed to investigators who maintained weekly contact with subjects and monitored continuously. |

Unclear

Pain is not reported in the results of both groups at baseline and after 12 weeks |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Cannell, 2001 |

Small study population (n<20) |

|

Jonsson, 2005 |

Small study population (n<20) |

|

Lim, 2018 |

Review without meta-analysis, studies were individually reviewed |

|

Rosety-Rodriquez, 2006 |

Language Spanish |

|

Young, 2004 |

Small study population (n<20) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 09-05-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 25-01-2022

|

Module[1] |

Regiehouder(s)[2] |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn[3] |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit[4] |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit[5] |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling[6] |

|

Oefentherapie patella tendinopathie |

VSG |

2022 |

2027 |

1x per 5 jaar |

VSG |

- |

[1] Naam van de module

[2] Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

[3] Maximaal na vijf jaar

[4] (half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

[5] regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

[6] Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Deze richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie

- Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie

- Nederlandse Vereniging van Podotherapeuten

- Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Arbeids- en Bedrijfsgeneeskunde

De richtlijn is goedgekeurd door:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland (en ReumaNederland)

Het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap heeft een verklaring van geen bezwaar afgegeven.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met anterieure kniepijn.

Werkgroep

- Dr. S. van Berkel, sportarts, Isala Zwolle, VSG (voorzitter)

- Dr. M. van Ark, fysiotherapeut, bewegingswetenschapper, Hanzehogeschool Groningen, Peescentrum ECEZG, KNGF

- Drs. G.P.G. Boots, bedrijfsarts, zelfstandig werkzaam, NVAB

- Drs. S. Ilbrink, sportarts, Jessica Gal Sportartsen en Sport- en Beweegkliniek, VSG

- Dr. S. Koëter, orthopedisch chirurg, CWZ, NOV

- Dr. N. Aerts-Lankhorst, waarnemend huisarts, NHG

- Dr. R. van Linschoten, sportarts, zelfstandig werkzaam, VSG

- Bsc. L.M. van Ooijen, (sport)podotherapeut en manueel therapeut, Profysic Sportpodotherapie, NVvP

- MSc. M.J. Ophey, (sport)fysiotherapeut, YsveldFysio, KNGF

- Dr. T.M. Piscaer, Orthopedisch chirurg-traumatoloog, Erasmus MC, NOV

- Drs. M. Vestering, radioloog, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, NVvR

Met methodologische ondersteuning van

- Drs. Florien Ham, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. Mirre den Ouden - Vierwind, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. Saskia Persoon, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. Miriam van der Maten, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Ilbrink |

Sportarts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Ooijen |

Sportpodotherapeut bij Profysic Sportpodotherapie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Linschoten |

Sportarts, zelfstandig werkzaam |

Hoofdredacteur Sport&Geneeskunde |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Piscaer |

Orthopedisch chirurg-traumatoloog, ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Boots |

Bedrijfsarts, zelfstandig werkend voor Stichting Volandis (het kennis- en adviescentrum voor duurzame inzetbaarheid in de Bouw & Infra) en de arbodiensten Human Capital Care en Bedrijfsartsen5. |

Sportkeuringen bij Stichting SMA Gorinchem (betaald), commissie medische zaken "Dordtse Reddingsbrigade" (onbetaald) en |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vestering |

Radioloog Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Ark |

Docent - Hanzehogeschool Groningen opleiding fysiotherapie |

Bij- en nascholing op het thema peesblessures voor verschillende organisaties (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ophey |

In deeltijd als fysiotherapeut werkzaam bij 1e lijns praktijk voor fysiotherapie "YsveldFysio" in Nijmegen, https://www.ysveldfysio.nl/ |

Bij- en nascholing van fysiotherapeuten voor verschillende organisaties in binnen-en buitenland), waarbij een enkele scholingsdag ook betrekking heeft op het thema "patellofemorale pijn". (betaald; gastdocent). |

Wetenschappelijk onderzoek gericht op mobiliteit in de kinetische keten bij patiënten met patellofemorale pijn (risicofactor) en op homeostase verstoringen in het strekapparaat (niet gesubsidieerd). |

Geen actie |

|

Van Berkel* |

Sportarts, Isala Zwolle |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Aerts - Lankhorst |

Waarnemend huisarts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Koëter |

Orthopaedisch chirurg CWZ |

Deelopleider Sportgeneeskunde CWZ Hoofd research support office CWZ |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een vragenlijst uit te zetten onder patiënten. De respons op de vragenlijst is besproken in de werkgroep en de verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie waarden en voorkeuren voor patiënten). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek PT |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Oefentherapie Patellofemorale pijn (PFP) |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen PFP |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Medicamenteuze behandelingen bij PFP |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Open chirurgie PT en PFP |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Oefentherapie patella tendinopathie (PT) |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen PT |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Medicamenteuze behandelingen PT |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met anterieure kniepijn. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie, Nederlandse Vereniging van Podotherapeuten, Stichting LOOP, Vereniging voor Sportgeneeskunde en Zorginstituut Nederland via een schriftelijke Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlage.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.