Anesthetica – Dampvormige Anesthesie versus TIVA

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van dampvormige anesthesie ten opzichte van totaal intraveneuze anesthesie (TIVA) bij patiënten met obesitas die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan onder algehele anesthesie?

Aanbeveling

Baseer de keuze voor intraveneuze of dampvormige anesthesie op duurzaamheid en eventuele patiëntfactoren (zie NVA Leidraad ‘Perioperatieve Zorg’, module 2.5: Duurzame anesthesie).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De werkgroep heeft een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van inhalatie anesthesie in vergelijking met intraveneuze anesthesie in patiënten met obesitas die een chirurgische ingreep moeten ondergaan onder algehele anesthesie. Er werden drie gerandomiseerde studies en één systematische review geïncludeerd.

De cruciale uitkomstmaten waren awareness en postoperatieve misselijkheid en braken en postoperatieve pijnscore (vroeg (binnen één uur) en na 24 uur). Voor awareness en postoperatieve misselijkheid en braken kan er geen eenduidige conclusie gegeven worden over het effect van inhalatie anesthesie in vergelijking met intraveneuze anesthesie bij mensen met obesitas (GRADE zeer laag). Er lijkt geen verschil te zijn in vroege postoperatieve pijn (GRADE laag). Voor postoperatieve pijn na 24 uur zijn twee verschillende conclusies getrokken, omdat de controlegroepen uiteenlopende anesthesieregimes hanteerden. Voor de vergelijking inhalatie anesthesie versus TIVA is er mogelijk niet tot nauwelijks voordeel voor het gebruiken van inhalatie anesthesie voor pijnscores op 24 uur (GRADE laag). Voor de vergelijking inhalatie anesthesie versus TIVA met toevoeging van Dexmedetomedine was het bewijs erg onzeker (GRADE zeer laag).

De totale bewijskracht is zeer laag. Dit wordt met name veroorzaakt door risk of bias vanwege gebrek aan blindering en imprecieze (brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen) resultaten.

De belangrijke uitkomstmaat was patiënttevredenheid. Er werden geen studies gevonden over patiënttevredenheid, waardoor er geen conclusie getrokken kan worden over het effect van inhalatie anesthesie in vergelijking met intraveneuze anesthesie op tevredenheid. Deze belangrijke uitkomstmaat kon dan ook geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming. Er bestaat een kennislacune ten aanzien van de effecten van inhalatie anesthesie in vergelijking met intraveneuze anesthesie bij mensen met obesitas die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan onder algehele anesthesie.

TIVA of inhalatie-anesthetica worden gebruikt als anestheticum tijdens algehele anesthesie. TIVA bestaat uit continue toediening van Propofol vaak op basis van een toedieningsprotocol (Schnider, 1998; Eleveld, 2018), eventueel samen met de continue toediening van een opioïd (bijvoorbeeld Remifentanil, zoals in Van Kralingen, 2011), en soms in combinatie met adjuncten zoals Dexmedetomedine en/of magnesium en/of Ketamine, etc. Van de inhalatieanesthetica (Halothaan, Isofluraan, Desfluraan, Sevofluraan) wordt in praktijk eigenlijk alleen maar Sevofluraan gebruikt.

Duurzaamheid

Er vindt binnen de anesthesie een discussie plaats over de toepassing van TIVA/Propofol infusie in vergelijking met dampvormige anesthetica en het effect van het gebruik op het milieu. De werkgroep vindt dat duurzaamheid een rol mag en moet spelen in het toepassen en de keuze van middelen en materiaalgebruik op het operatiecentrum. De werkgroep verwijst hiervoor naar de literatuur en de NVA Leidraad ‘Perioperatieve Zorg’ (module 2.5: Duurzame anesthesie) om op de hoogte te blijven van de meest recente ontwikkelingen en aanbevelingen omtrent duurzaamheid.

Postoperatieve misselijkheid en braken

In het algemeen zijn de geïncludeerde studies lastig te vergelijken door de variatie binnen zowel de TIVA- als inhalatieanesthetica-groepen ten aanzien van het gebruik van eventuele adjuncten als keuze van postoperatieve misselijkheid en braken (POMB) profylaxe.

Er was een trend richting een verbetering van POMB-klachten in de TIVA-groep ten opzichte van de inhalatie anesthetica groep in de geïncludeerde studies in deze richtlijn. De bewijskracht hiervoor is echter zeer laag, en de geïncludeerde studies weerspiegelen vermoedelijk de Nederlandse praktijk niet, aangezien er in Demirel (2021), Honca (2017) en Juvin (2000) geen standaard POMB-profylaxe werd toegediend, terwijl veel van deze patiënten risicofactoren voor POMB gehad zullen hebben (op zijn minst opioïd gebruik postoperatief, inhalatie anesthetica en eventueel nog vrouwelijk geslacht en niet-roker als risicofactoren). De consensus richtlijn over POMB, die ook erkend is door de Europese Society of Anesthesiology, adviseert ook om bij patiënten met een middelhoog tot hoog risico op POMB twee of drie klassen van anti-emetica te gebruiken (Gan, 2020). Het is niet zeker in welke mate het verschil tussen de groepen nog aanwezig zal zijn indien POMB-profylaxe routinematig gebruikt wordt bij risicofactoren. De reductie van POMB-klachten in een algemene populatie door gebruik van TIVA ten opzichte van inhalatie anesthetica is onder andere aangetoond in de landmark IMPACT studie (Apfel, 2004). Aangezien BMI het risico op POMB-klachten niet lijkt te beïnvloeden (Shaikh, 2016; Kranke, 2001) is het wel aannemelijk voor de werkgroep dat TIVA in een patiëntenpopulatie met obesitas ook zal leiden tot een vermindering van POMB-klachten ondanks dat er in de voorliggende analyse ten behoeve van deze richtlijn geen klinische relevantie kon worden aangetoond.

Postoperatieve pijnscores

Postoperatieve pijnscores leken niet verschillend in de groepen behoudens in de studie van Elbakry (2018), waar echter ook Dexmedetomidine werd gebruikt als adjunct. In een niet-obese populatie werd er in twee heterogene meta-analyses mogelijk enkel een niet-klinisch relevant verschil gezien in patiënten die Propofol kregen ten opzichte van inhalatie-anesthetica met een verschil van -0.134 op een 0 – 10 VAS-score (Peng, 2016; Qiu, 2016). De werkgroep is van mening dat er geen klinisch relevant verschil is ten aanzien van postoperatieve pijnklachten bij gebruik van TIVA ten opzichte van inhalatieanesthetica in patiënten met obesitas blijkens deze studie.

De keuze welk middel gebruikt wordt voor onderhoud van de anesthesie kan ook een effect hebben op de uitleidingstijd. Echter is er door de werkgroep voor gekozen om dit niet op te nemen in de literatuuranalyse als uitkomstmaat, omdat deze in grote mate afhankelijk is van externe factoren, zoals de ervaring van het anesthesiepersoneel. Studies geven geen eenduidige resultaten over de uitleidingstijd (Honca, 2017; Juvin, 2000; Siampalioti, 2021). De uitleidingstijd is echter lastig te vergelijken doordat de studies verschilden in gebruik van type inhalatie-anestheticum en in het gebruik van wel of geen ‘Depth-of-Anesthesia monitoring devices’ zoals de BIS™ monitor.

Het grootste gedeelte van de studies gebruikte nog Desfluraan en een kleiner aandeel van de studies Sevofluraan en een enkele Isofluraan. Het vermeende voordeel van Desfluraan is de snellere uitleiding ten gevolge van een voordeliger oplosbaarheidsprofiel. Dit lijkt ook zo te zijn in één gepubliceerde meta-analyse waar Desfluraan in de algemene populatie werd vergeleken met de andere inhalatie-anesthetica en met twee studies waarin Propofol werd gebruikt (Liu, 2015). De studies varieerden echter in chirurgische procedure en anesthesieprotocollen, wat generalisatie moeilijk maakt. Het gebruik van ‘Depth-of-Anesthesia monitoring devices’ zoals de BIS™ monitor gecombineerd met duidelijkere protocollen in de tegenwoordige praktijk kunnen die verschillen al verkleinen. De werkgroep is van mening dat het gebruik van Desfluraan niet meer te verantwoorden is gezien de 25-50 maal hogere CO2 uitstoot ten opzichte van Sevofluraan (Gaya da Costa, 2021; Hanna, 2019; Ryan, 2010) met mogelijk enkel een geringe snellere uitleidingstijd (zie Duurzaamheid).

Awareness

Awareness met recall komt zeer infrequent (1 tot 2 per 1000, Myles, 2004; Avidan, 2008) voor en is om die reden lastig te onderzoeken (Sebel, 2004). De enige geïncludeerde studie waarin awareness werd geëvalueerd (Gaszyński, 2016) in een bariatrische populatie toonde geen gevallen aan van intra-operatieve awareness met recall. Interessant genoeg hadden patiënten in beide studiegroepen frequente BIS-waarden boven de 60 (90% van de TIVA-groep, 91.7% Sevofluraan groep), waarvan 37% boven de 80 in de TIVA-groep ten opzichte van 8.3% in de Sevofluraan groep. Awareness met recall kan in deze studie verbloemd zijn door het gebruik van Midazolam. Deze studie doseerde volgens de Servin formule: gecorrigeerde lichaamsgewicht (Adjusted Body Weight) = ideaal lichaamsgewicht + [0.4 x (totaal lichaamsgewicht – IBW)] (Servin, 1993). Deze methode overschat vermoedelijk de plasmaspiegels van Propofol in patiënten met obesitas waardoor daadwerkelijke Propofolspiegels lager zijn dan gedacht (Albertin, 2007). Farmacokinetische modellen die totaal lichaamsgewicht (TBW) in allometrische formules gebruiken voor Propofol lijken een betere concordantie te hebben met de plasmaspiegels. Voorbeeldformules zijn: doseergewicht = (70 kg × [TBW/70]0.72) of 0.75 (Cortínez, 2010; van Kralingen, 2011). Alhoewel het te gebruiken doseergewicht bij patiënten met obesitas geen zoekvraag was van deze richtlijn adviseert de werkgroep wel een doseergewicht te gebruiken dat gebaseerd is op wetenschappelijk bewijs zoals bij Cortínez (2010) en Van Kralingen (2011). Daarbij verwijst de werkgroep ook naar module BIS-monitoring.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Vanuit een patiëntenperspectief hangt tevredenheid na algehele anesthesie af van meerdere factoren. Persisterende misselijkheid en pijnklachten zijn belangrijke voorspellers van een verminderde tevredenheid na chirurgie. Andere factoren zoals de preoperatieve verwachtingen en de chirurgische uitkomst kunnen de tevredenheid verder beïnvloeden (Royse, 2013).

De huidige literatuuranalyse kan geen eenduidige uitspraken doen ten aanzien van postoperatieve pijnklachten tussen TIVA en inhalatie anesthetica. Een lagere incidentie van POMB-klachten, zoals eerder beschreven, kan aansluiten bij de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het peroperatief gebruik van TIVA is waarschijnlijk duurder dan gebruik van inhalatieanesthetica. De kosten liggen niet alleen aan de prijs van het medicijn, maar ook aan de benodigde apparatuur (perfusorpompen, eventueel TCI-systemen, plastic spuiten). Het gebruik van inhalatieanesthetica vereist ook een verdamper en eventueel een dampopvanger.

In een oudere Nederlandse studie waren de kosten van TIVA $28.98 hoger voor klinische patiënten en $14.87 voor ambulante chirurgie ten opzichte van Isofluraan. POMB werd minder vaak gezien in de TIVA-groep met een NNT van 6. Deze studie was verricht voordat het octrooi op Propofol verlopen was in Nederland. De kosten van Propofol zijn nadien tot wel 75% gedaald, waardoor het prijsverschil wellicht afgenomen is (Visser, 2001).

De reductie van POMB-klachten door Propofol leidt echter niet alleen tot een kostenbesparing van anti-emetica maar mogelijk ook tot kortere opnameduur op de PACU/recovery. In zijn totaliteit kan dit zelfs een kostenbesparing opleveren van TIVA ten opzichte van inhalatieanesthetica van $11.41 per patiënt (Kampmeier, 2021).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Anesthesiologen in Nederland werken met zowel intraveneuze (TIVA) als dampvormige (inhalatie) anesthetica. Voor de keuze tussen het gebruik van deze twee vormen van anesthetica in het kader van duurzame anesthesie wordt verwezen naar module 2.5 van de NVA Leidraad ‘Perioperatieve Zorg’.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is veel variatie tussen de studies, wat het maken van een gegeneraliseerde aanbeveling bemoeilijkt. Er geen hoogwaardig bewijs dat een verschil tussen TIVA en inhalatie-anesthetica aantoont ten aanzien van postoperatieve pijn en awareness in patiënten met obesitas.

Hoewel de bewijskracht zeer laag is, ziet de werkgroep dat de bestaande studies wel de suggestie wekken dat POMB-klachten minder vaak voorkomen in de TIVA-groep.

De keuze tussen TIVA of dampvormige anesthetica dient gebaseerd te worden op andere factoren dan het lichaamsgewicht van de patiënt vanwege de reeds vermelde gebrekkige bewijsvoering. Factoren die kunnen meegewogen worden zijn bijvoorbeeld patiëntfactoren, duurzaamheid, kosten, lokale ervaring en beleid.

Daarbij adviseert de werkgroep om TIVA te doseren op basis van een doseergewicht en doseerschema’s die onderbouwd zijn door middel van farmacokinetische en farmacodynamische studies zoals Cortínez (2010) en Van Kralingen (2011).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Onderhoud van anesthesie wordt bereikt middels dampvormige anesthetica of TIVA. Dampvormige anesthetica worden van oudsher gebruikt en zijn goed te titreren op basis van alveolaire concentraties. In de algemene populatie zal TIVA minder postoperatieve misselijkheid en braken (POMB) veroorzaken, echter is er mogelijk meer risico op awareness (waarvan het a priori risico zeer laag is) en blijft continu goedlopende intraveneuze toegang noodzakelijk (Absalom, 2017). Doseren bij patiënten met obesitas vergt extra aandacht in verband met een mogelijk veranderde farmacokinetiek en farmacodynamiek ten gevolge van obesitas.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of inhalation anesthesia in comparison to total intravenous anesthesia on awareness in patients with obesity undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia.

Source: Gaszyński, 2016 |

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of inhalation anesthesia in comparison to total intravenous anesthesia on postoperative nausea in patients with obesity undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia.

Source: Demirel, 2021; Elbakry, 2018; Honca, 2017; Juvin, 2000; Tanaka, 2017. |

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of inhalation anesthesia in comparison to total intravenous anesthesia on postoperative vomiting in patients with obesity undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia.

Source: Demirel, 2021; Elbakry, 2018; Honca, 2017; Juvin, 2000; Tanaka, 2017. |

|

Low GRADE

|

Inhalation anesthesia may result in little to no difference in early postoperative pain in comparison with intravenous anesthesia in patients with obesity undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia.

Source: Juvin, 2000; Siampalioti, 2021; Tanaka, 2017. |

|

Low GRADE

|

Inhalation anesthesia may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain at 24 hours in comparison with intravenous anesthesia in patients with obesity undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia.

Source: Aftab, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE

|

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of inhalation anesthesia in comparison to total intravenous anesthesia with Dexmedetomidine on postoperative pain at 24 hours in patients with obesity undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia.

Source: Elbakry, 2018 |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of inhalation anesthesia in comparison with total intravenous anesthesia on patient satisfaction in patients with obesity undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Ahmed (2021) performed a systematic review comparing inhalation anesthesia with total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA). Out of the seven RCTs included in Ahmed (2021), two studies were excluded in the current analysis of the literature (Spaniolas, 2020; Ziemann-Gimmel, 2014). Spaniolas (2020) was excluded as no outcomes of interest were reported. Ziemann-Gimmel (2014) was excluded as the intervention group received intraoperative opioids and the control group did not.

An overview of the characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review of Ahmed (2021) is presented in Table 1. Elbakry (2018), was judged with a low risk of bias. For Honca (2017), risk of bias was considered high due to a lack of blinding and no reporting of allocation concealment. For Aftab (2019), Siampalioti (2015) and Juvin (2000) there were some concerns regarding risk of bias due to incomplete reporting/lack of blinding and no/incomplete reporting of randomization and/or allocation concealment.

Table 1. Overview of the RCTs included in the systematic review of Ahmed (2021).

|

Author, year |

N (I/C) |

Population |

Intervention (Inhalation anesthesia) |

Control (TIVA) |

Outcome measures |

|

Elbakry, 2018

|

50/50 |

Patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy

BMI ± SD: I: 42.6 ± 4.4 C: 41.6 ± 4.4

Age ± SD: I: 35.3 ± 10.4 C: 34.4 ± 11.1

Sex: I: 70.0% F C: 66.0% F |

Induction: see other drugs

Maintenance: desflurane 60/40% oxygen air mixture

BIS was maintained between 40 and 60 by using boluses of 0.5 μg/kg remifentanil.

|

Induction: see other drugs

Maintenance: Propofol 100–200 μg/kg/min and Dexmedetomidine 0.5–1.0 μg/kg/h

BIS was maintained between 40 and 60 by using boluses of 0.5 μg/kg remifentanil.

|

PONV

Pain scores (VAS 0-10)

|

|

Honca, 2017

|

30/31 |

Patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy

BMI ± SD: I: 43.5 ± 4.5 C: 44.5 ± 4.6

Age ± SD: I: 40.0 ± 10.1 C: 35.9 ± 11.1

Sex: I: 70.0% F C: 93.6% F |

Induction: see other drugs

Maintenance: desflurane BIS was maintained between 45 and 55 by desflurane administration.

|

Induction: see other drugs

Maintenance: Propofol 21 mg/ kg CBW for 5 min, 12 mg/kg CBW for 10 min, and then 6 mg/kg CBW

BIS was maintained between 45 and 55 by Propofol administration.

|

PONV

|

|

Aftab, 2019

2 groups per arm: Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and RYGB

These groups are combined in the result section of the literature analysis. |

49+44/ 52+38

|

Patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or RYGB

BMI ± SD: I: 43.0 ± 6.0 C: 41.0 ± 5.6

Age ± SD: I: 43.0 ± 11 C: 46.0 ± 11.0

Sex: I: 76.0% F C: 78.0% F |

Induction: Propofol and remifentanil

Maintenance: Desflurane and remifentanil |

Induction: Propofol and fentanyl

Maintenance: Propofol and remifentanil

|

Pain (measured on a VAS)

|

|

Siampalioti, 2015

4 groups: 1) Sevoflurane with BIS monitoring (S-BIS) 2) Sevoflurane without BIS monitoring (S) 3) Propofol with BIS (P-BIS) 4) Propofol without BIS (P)

Groups 1 & 2 and 3 & 4 are combined in the result section of the literature analysis |

25/25/25/ 25 |

Patients undergoing Biliopancreatic diversion variant

BMI ± SD: I (S): 42.0 ± 8.0 I (S-BIS): 36.0 ± 10.0 C (P): 36.0 ± 9.0 C (P-BIS): 37.0 ± 9.0

Age ± SD: I (S): 61.10 ± 10.0 I (S-BIS): 57.0 ± 9.0 C (P): 59.0 ± 11.0 C (P-BIS): 55.0 ± 6.0

Sex: I (S): 60.0% F I (S-BIS): 72.0% F C (P): 68.0% F C (P-BIS): 76.0% F |

Induction: Propofol 2 mg/kg CBW with bolus remifentanil 1 μg/kg IBW and succinylcholine 1 μg/kg IBW

Maintenance in S-group: end-tidal sevoflurane concentrations of 1–3% via fresh gas flow 6 L/min, semi-closed circuit. Bolus 8% sevoflurane for every rise in BP/HR>15% baseline. Nifedipine 10 mg SL if HR<70/min and diltiazem 10–20 mg if HR > 70/min IV In the S-BIS group, BIS was maintained between 40 and 55.

|

Induction: Propofol 21 mg/kg CBW for 5 min, 12 mg/kg CBW for 10 min and then 6 mg/ kg CBW with bolus remifentanil 1 μg/kg IBW, succinylcholine 1 μg/kg IBW

Induction: remifentanil

Maintenance in P-group: Propofol 6–10 mg/kg/h CBW and remifentanil 0.1–1.0 μg/kg/min. Bolus remifentanil 1 μg/kg IBW for every rise in BP/HR > 15% baseline with continuous infusion remifentanil 1.0 μg/ kg/min.

Reduction in remifentanil for any decrease in BP < 15% of baseline with etilerine as needed In the P-BIS group, BIS was maintained between 40 and 55. |

VAS score for pain (scale 0-10)

|

|

Juvin, 2000

3 groups: 1) desflurane 2) isoflurane 3) Propofol

Groups 1 & 2 are combined in the result section of the literature analysis |

24/12

|

Patients undergoing Laparoscopic gastroplasty

BMI ± SD: I (D): 46.5 ± 5.3 I (I): 47.5 ± 4.9 C: 44.3 ± 4.0

Age ± SD: I (D): 40.1 ± 7.0 I (I): 36.5 ± 8.5 C: 39.7 ± 10.4

Sex: I (D): 75.0% F I (I): 83.3% F C: 83.3% F |

Induction: see other drugs

Maintenance: desflurane (12 patients) or isoflurane (12 patients). The Propofol TCI was stopped after induction.

BIS was maintained between 45 and 55.

|

Induction: see other drugs

Maintenance: Propofol

BIS was maintained between 45 and 55.

|

PONV (events for nausea – vomiting – patients who received antiemetic)

Pain scores (30, 60 and 120 min postoperative) (0-10 scale) |

BIS: bispectral index, BMI: body mass index, BP: blood pressure, CBW: corrected body weight, HR: heart rate, IBW: ideal body weight, RCT: randomized controlled trial, SD: standard deviation, PONV: postoperative nausea and vomiting, PSI: Patient State Index, RYGB: Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass, VAS: visual analogue scale.

Additionally, to the review of Ahmed (2021), three RCTs were included.

Gaszyński (2016) performed an RCT to compare intraoperative awareness after sevoflurane-based inhalation anesthesia and Propofol-based TIVA in 120 patients with severe obesity. Awareness was assessed 2 hours postoperatively. For risk of bias, there are some concerns due to incomplete reporting of blinding, randomization and allocation concealment.

Demirel (2011) assigned 120 patients with severe obesity randomly to four groups: 1) desflurane-based inhalation anesthesia with PSI monitoring (group D-PSI), 2) desflurane-based inhalation anesthesia without PSI monitoring (group D), 3) Propofol-based TIVA with PSI monitoring (group P-PSI), and 4) Propofol-based TIVA without PSI monitoring (group P) to evaluate PONV. For risk of bias, there are some concerns due to incomplete reporting of blinding, randomization and allocation concealment.

Tanaka (2017) assigned 100 patients with obesity undergoing total knee replacement randomly into two groups, receiving maintenance anesthesia with either Propofol or desflurane to study the effects on pain and PONV. For risk of bias, there are some concerns due to incomplete reporting of the randomization method and allocation concealment and a high number of dropouts in the study. Further, interpretation of the study results is hard since it is not clear whether results were reported as means and confidence intervals or other types of values.

An overview of characteristics of the included RCTs is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of the included RCTs.

|

Author, year |

N (I/C) |

Population |

Intervention (Inhalation anesthesia) |

Control (TIVA) |

Relevant reported outcome measures |

|

Gaszyński, 2016

|

60/60 |

Patients with obesity (BMI > 33) undergoing bariatric surgery

BMI (range) (SD not reported): I: 45.1 (33.8 to 57.4) C: 42.7 (35 to 58.1)

Age (range) (SD not reported): I: 40.0 (18 to 65) C: 35.9 (17 to 64)

Sex: I: 80.0% F C: 66.7% F |

Sevoflurane concentration according to patients age and modified based on clinical parameters (in order to maintain hemodynamic stability).

Fresh gas flow was set at: - 4 L/min in the beginning of anesthesia - 1 L/min after 10 minutes - 2 L/min after 1 hour |

The following concentrations of Propofol infusions were used:

Induction: 1.5−2.0 mg kg-2 of corrected body weight (calculated as: IBW [ideal body weight] + 0.4 × [total body weight–ideal body weight]);

Infusion concentration was: - 10 mg/kg/h in the beginning of anesthesia - 8 mg/kg/h after 10 minutes - 6 mg/kg/h to end the administration of anesthesia |

Awareness (nr events) |

|

Demirel, 2021

4 groups: 1) desflurane with PSI monitoring (D-PSI) 2) desflurane without PSI monitoring (D) 3) Propofol with PSI (P-PSI) 4) Propofol without PSI (P) |

30/30/ 30/ 30 |

Patients with obesity (BMI>40) undergoing elective-sleeve gastrectomy

BMI ± SD: I (D-PSI): 45.6±5.6 I (D): 50.1±16.4 C (P-PSI): 50.5±14.7 C (P): 45.5±3.9

Age ± SD: I (D-PSI): 35.0±13.0 I (D): 34.4±11.6 C (P-PSI): 37±10.6 C (P): 34.4±10.4

Sex: I (D-PSI): 73.3% I (D): 70% C (P-PSI): 70% C (P): 53.3% |

Induction in groups D-PSI and group D: 2 mg/kg of Propofol in accordance with CBW. About 1 mcg/kg bolus dose of remifentanil according to IBW was administered for more than 30 to 60 seconds. About 0.6 mg/kg of rocuronium was administered to optimize endotracheal intubation in line with IBW.

Maintenance of anesthesia: - In group D-PSI, desflurane concentration was adjusted to maintain a PSI value of 25 to 50 - Group D was treated to have an end-tidal desflurane concentration of approximately 6%.

|

Induction in groups P-PSI and P: 2 mg/kg of Propofol in accordance with CBW. About 1 mcg/kg bolus dose of remifentanil according to IBW was administered for more than 30 to 60 seconds, and 0.6 mg/kg of rocuronium, based on IBW, was to optimize endotracheal intubation.

Maintenance of anesthesia: - Group P-PSI received a Propofol infusion to maintain a PSI level of 25 to 50 - Group P received a 6 to 10 mg/kg/h Propofol infusion according to CBW. |

PONV: scored as present or absent (events for no PONV – nausea – Gagging – Vomiting)

|

|

Tanaka, 2017

|

45/45 |

Patients with obesity (BMI>30) > 65 years old undergoing elective total knee arthroplasty.

BMI (mean): I: 36.5 C: 34.0

Age (mean): I: 69.8 C: 70.6

Sex: I: 44.4% F C: 66.7% F |

Anesthesia was maintained with desflurane.

The maintenance agent was titrated to a PSI of 30–50 using the algorithm described in the supplemental con- tent.

Following surgery, a continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 6 ml/h was initiated in the recovery room and adjusted to a maximum of 10 ml/h for the next 48 h. |

Anesthesia was maintained with Propofol.

The maintenance agent was titrated to a PSI of 30–50 using the algorithm described in the supplemental con- tent.

Following surgery, a continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 6 ml/h was initiated in the recovery room and adjusted to a maximum of 10 ml/h for the next 48 h. |

postoperatively) PONV

Pain (1 hour and 6-8 hours |

BMI: body mass index, RCT: randomized controlled trial, SD: standard deviation, CBW: corrected body weight, IBW: ideal body weight, HR: heart rate, BP: blood pressure, BIS: bispectral index, PSI: Patient State Index

All studies that were included in the analysis of the literature varied in terms of used medication and its concentration in both the intervention and control groups. Most studies included monitoring via Bispectral Index (BIS) or Patient State Index (PSI) or monitoring of the alveolar concentration in both the intervention and control group, with exception of Gaszyński (2016) and Aftab (2019). Further, in most studies, other drugs were administered to all participants of both the intervention and control group during and after anesthesia. Information about these drugs is provided in the evidence table.

Results

1. Awareness

One study included in the literature analysis reported on the outcome awareness (Gaszyński, 2016). Awareness was evaluated using a questionnaire consisting of 16 questions in which memories of anesthesia were evaluated. None of the participants in both the intervention group (0/60, 0%) and the TIVA-group (0/60, 0%) reported intraoperative awareness when asked in the postoperative period (RD 0.0, 95%CI -0.03 to 0.03).

2. Postoperative nausea and vomiting

Five studies reported the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (Demirel, 2021; Elbakry, 2018; Honca, 2017; Juvin, 2000; Tanaka, 2017).

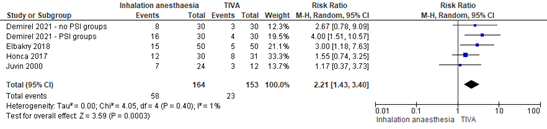

Meta-analyses for postoperative nausea (Figure 1) and postoperative vomiting (Figure 2) were performed. Note that Tanaka (2017) was not included in the meta-analyses because of missing information (see reported results in Table 4). Demirel (2021) reported the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting separately for groups with and without PSI monitoring.

Postoperative nausea was reported in 58/164 (35.4%) patients receiving inhalation anesthesia and in 23/153 (15.0%) patients receiving TIVA. The relative risk (RR) was 2.21 (95% CI 1.43 to 3.40).

A sensitivity analysis was performed by removing Elbakry (2018) from the analysis, because Dexmedetomidine was added to TIVA. The sensitivity analysis did not affect the conclusions.

Figure 1. Postoperative nausea. Source: Ahmed (2021), Demirel (2021).

95% CI: 95% confidence interval

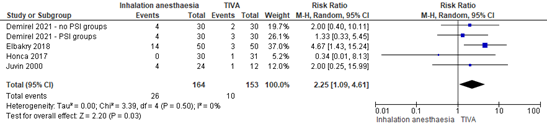

Postoperative vomiting was reported in 26/164 (15.9%) patients receiving inhalation anesthesia and in 10/153 (6.5%) patients in the TIVA group (Figure 2). The RR was 2.25 (95% CI 1.09 to 4.61).

Again, a sensitivity analysis was performed by removing Elbakry (2018) from the analysis, due to the addition of Dexmedetomidine to TIVA. The sensitivity analysis did not affect the conclusions.

Figure 2. Postoperative vomiting. Source: Ahmed (2021), Demirel (2021).

95% CI: 95% confidence interval

The results by Tanaka (2017) could not be included in the meta-analyses, as the number of events were not reported. We were not able to calculate the number of events based on the limited information and therefore no relative risk is reported in the current analysis. The percentage of patients experiencing nausea and vomiting was reported (Table 3).

Table 3. Postoperative nausea and vomiting as reported by Tanaka (2017).

|

|

Inhalation anesthesia (desflurane) |

TIVA (Propofol) |

Risk Difference (95% CI) |

|

|

Nausea |

1 hour postoperatively |

7.32% |

4.88% |

2.44% (unknown*), p=0.045 |

|

6-8 hours postoperatively |

12.2% |

12.2% |

0% (unknown*), P=1.00 |

|

|

Vomiting |

1 hour postoperatively |

4.88% |

0% |

4.88% (unknown*), p=0.153 |

|

6-8 hours postoperatively |

7.32% |

2.44% |

4.88% (unknown*), p=0.306 |

|

*As the number of missing participants per group was not reported, we were not able to calculate the absolute number of events and the 95% confidence interval of the risk difference.

Overall, patients in the TIVA group experienced less postoperative nausea and vomiting. This difference was clinically relevant.

3. Postoperative pain score (early and at 24 h postoperative)

Four studies included in the systematic review of Ahmed (2021) (Elbakry, 2018; Juvin, 2000; Siampalioti, 2015; Aftab, 2019) and one additional RCT (Tanaka, 2017) reported postoperative pain scores on a 0-10 VAS.

Pain scores were reported at 30 minutes postoperatively (Juvin, 2000; Siampalioti, 2015), at 60 minutes postoperatively (Tanaka, 2017) and at 24 hours postoperatively (Aftab, 2019; Elbakry, 2018). Pain scores are presented in Table 4. Note that it was not clear whether reported values of Tanaka (2017) were means and 95% confidence intervals. Therefore, results were not pooled.

Table 4. Early postoperative pain scores and 24h postoperative pain scores.

|

|

Author, year |

Inhalation anesthesia |

TIVA |

Mean Difference (95% CI) |

|

Early postoperative pain scores |

Juvin, 2000 |

4.1 ± 2.5 |

4.4 ± 2.1 |

-0.3 (-1.9, 1.32) |

|

Siampalioti, 2015 |

3.8 ± 2.7 |

3.5 ± 2.1 |

0.30 (-0.63, 1.23) |

|

|

Tanaka, 2017 |

3.68 ± 3.40 |

3.7 ± 2.86 |

-0.02 (-1.32, 1.28) |

|

|

24h postoperative pain scores |

Aftab, 2019 |

1.2 ± 1.7 |

1.2 ± 1.9 |

-0.0 (-0.6, 0.5) |

|

Elbakry, 2018 |

3.0 ± 1.7 |

0.8 ± 1.9 |

2.2 (0.0, 4.5) |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Source: Ahmed (2021), Tanaka (2017) 95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval

Overall, mean differences in early postoperative pain scores were not clinically relevant. Postoperative pain scores at 24 hours showed inconclusive results, as the scores in Aftab (2019) were similar in both groups, but Elbakry (2018) showed a clinically relevant lower scores in the TIVA group. Results by Elbakry (2018) may differ due to the addition of Dexmedetomidine to TIVA. As this anesthetic regimen differs from the other studies, the level of evidence for pain scores by Elbakry (2018) was graded separately.

4. Patient satisfaction

None of the included studies reported the outcome ‘patient satisfaction’.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of all outcome measures started as high, as the included studies were RCTs.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure awareness was downgraded by three levels, because of lack of blinding (-1; risk of bias) and a low number of events in a small population (-2; imprecision). The level of evidence for awareness is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative nausea was downgraded by three levels, because of a lack of blinding (-1; risk of bias) and a low number of events in a small population (-2; imprecision). The level of evidence for postoperative nausea is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative vomiting was downgraded by three levels, because of a lack of blinding (-1; risk of bias) and wide confidence intervals crossing one threshold of clinical relevance and a low number of events in a small population (-2; imprecision). The level of evidence for postoperative vomiting is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure early postoperative pain was downgraded by two levels, because of lack of blinding (-1; risk of bias) and because of wide or unclear confidence intervals reported by the individual studies (-1; imprecision). The level of evidence for early postoperative pain is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 24h for inhalation anesthesia versus TIVA was downgraded by two levels, because of a lack of blinding (-2; risk of bias),. The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 24h for inhalation anesthesia versus TIVA and Dexmedetomidine was downgraded by three levels, because of a lack of blinding (-1; risk of bias), indirectness (-1; applicability bias due to adding Dexmedetomidine in the control group) and because of wide confidence interval crossing the thresholds of clinical relevance (-1; imprecision). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction could not be graded as none of the included studies reported this outcome measure.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favorable effects of inhalation anesthesia versus TIVA during surgery in patients with obesity undergoing a chirurgical procedure requiring general anesthesia?

P: Patients with obesity undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia

I: Inhalation anesthesia (sevoflurane, desflurane)

C: Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA)

O: Awareness, postoperative nausea and/or vomiting (PONV), pain scores (early postoperative and at 24 hours postoperative), patient satisfaction

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered awareness, PONV and postoperative pain scores, as critical outcome measures for decision making; and patient satisfaction as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group defined PONV as the proportion of patients experiencing postoperative nausea and/or vomiting.

Postoperative pain score was defined as pain score assessed by a visual analogue scale (VAS) or numeric rating scale (NRS). Early postoperative pain was defined as a score assessed within 60 minutes post-surgery.

The working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference:

- Awareness: 0.91≥RR≥1.10, -0.1≥RD≥0.1

- Postoperative nausea and/or vomiting (PONV): 0.8≥RR≥1.25, -0.25>RD>0.25

- Postoperative pain score: MD (mean difference) >10% of the maximum score on the VAS or NRS

- Patient satisfaction: 0.8≥RR≥1.25

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 23-02-2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 355 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: 1) a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and/or observational comparative studies, an RCT or an observational comparative study (case control or cohort study), 2) published after 2000, 3) including patients with obesity (BMI≥30) undergoing a surgical procedure under general anesthesia, 4) comparing inhalational anesthesia with TIVA, and 5) reporting at least one of the previously defined outcome measures.

A total of 45 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 41 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

Results

Three RCTs and one systematic review were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Absalom, A. R., & Mason, K. P. (2017). Total intravenous anesthesia and target controlled infusions. Springer.

- Ahmed MM, Tian C, Lu J, Lee Y. Total Intravenous Anesthesia Versus Inhalation Anesthesia on Postoperative Analgesia and Nausea and Vomiting After Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian J Anesthesiol. 2021 Dec 1;59(4):135-151. Doi: 10.6859/aja.202112_59(4).0002. Epub 2021 Nov 19. PMID: 34856740.

- Albertin A, Poli D, La Colla L, Gonfalini M, Turi S, Pasculli N, La Colla G, Bergonzi PC, Dedola E, Fermo I. Predictive performance of ‘Servin’s formula’ during BIS-guided propofol-remifentanil target-controlled infusion in morbidly obese patients. Br J Anaesth. 2007 Jan;98(1):66-75. Doi: 10.1093/bja/ael321. Epub 2006 Nov 27. PMID: 17132644.

- Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, Zernak C, Danner K, Jokela R, Pocock SJ, Trenkler S, Kredel M, Biedler A, Sessler DI, Roewer N; IMPACT Investigators. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004 Jun 10;350(24):2441-51. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032196. PMID: 15190136; PMCID: PMC1307533.

- Avidan MS, Mashour GA. Prevention of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall: making sense of the evidence. Anesthesiology. 2013 Feb;118(2):449-56. Doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31827ddd2c. PMID: 23263014.

- Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al. Anesthesia awareness and the bispectral index. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1097-1108.

- Cortínez LI, Anderson BJ, Penna A, Olivares L, Muñoz HR, Holford NH, Struys MM, Sepulveda P. Influence of obesity on propofol pharmacokinetics: derivation of a pharmacokinetic model. Br J Anaesth. 2010 Oct;105(4):448-56. Doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq195. Epub 2010 Aug 14. PMID: 20710020.

- Demirel I, Yildiz Altun A, Bolat E, Kilinc M, Deniz A, Aksu A, Bestas A. Effect of Patient State Index Monitoring on the Recovery Characteristics in Morbidly Obese Patients: Comparison of Inhalation Anesthesia and Total Intravenous Anesthesia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021 Feb;36(1):69-74. Doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2020.07.005. Epub 2020 Oct 1. PMID: 33012596.

- Eleveld DJ, Colin P, Absolom AR, Struys MMRF. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model for propofol for broad application in anaesthesia and sedation. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:942-959

- Gan TJ, Belani KG, Bergese S, et al. Fourth consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(2):411-448.

- Gaszyński T, Wieczorek A. A comparison of BIS recordings during propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia and sevoflurane-based inhalational anesthesia in obese patients. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2016;48(4):239-247. Doi: 10.5603/AIT.2016.0044. PMID: 27797096.

- Gaya da Costa M, Kalmar AF, Struys MMRF. Inhaled Anesthetics: Environmental Role, Occupational Risk, and Clinical Use. J Clin Med. 2021 Mar 22;10(6):1306. Doi: 10.3390/jcm10061306. PMID: 33810063; PMCID: PMC8004846.

- Hanna M, Bryson GL. A long way to go: minimizing the carbon footprint from anesthetic gases. Can J Anaesth. 2019 Jul;66(7):838-839. Doi: 10.1007/s12630-019-01348-1. Epub 2019 Mar 15. PMID: 30877589.

- Hu X, Pierce JT, Taylor T, Morrissey K. The carbon footprint of general anaesthetics: A case study in the UK. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2021;167:105411.

- Kampmeier T, Rehberg S, Omar Alsaleh AJ, Schraag S, Pham J, Westphal M. Cost-Effectiveness of Propofol (Diprivan) Versus Inhalational Anesthetics to Maintain General Anesthesia in Noncardiac Surgery in the United States. Value Health. 2021 Jul;24(7):939-947. Doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.01.008. Epub 2021 Apr 1. PMID: 34243837.

- Kranke P, Apefel CC, Papenfuss T, Rauch S, Löbmann U, Rübsam B, Greim CA, Roewer N. An increased body mass index is no risk factor for postoperative nausea and vomiting. A systematic review and results of original data. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001 Feb;45(2):160-6. PMID: 11167160.

- Liu FL, Cherng YG, Chen SY, Su YH, Huang SY, Lo PH, Lee YY, Tam KW. Postoperative recovery after anesthesia in morbidly obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2015 Aug;62(8):907-17. Doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0405-0. Epub 2015 May 22. PMID: 26001751.

- Myles PS, Leslie K, McNeil J, Forbes A, Chan MTV. Bispectral index monitoring to prevent awareness during anaesthesia: the B-Aware randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9423):1757-1763.

- Peng K, Liu HY, Wu SR, Liu H, Zhang ZC, Ji FH. Does Propofol Anesthesia Lead to Less Postoperative Pain Compared With Inhalational Anesthesia?: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2016 Oct;123(4):846-58. Doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001504. PMID: 27636574.

- Qiu Q, Choi SW, Wong SS, Irwin MG, Cheung CW. Effects of intra-operative maintenance of general anesthesia with propofol on postoperative pain outcomes – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesia. 2016 Oct;71(10):1222-33. Doi: 10.1111/anae.13578. Epub 2016 Aug 10. PMID: 27506326.

- Royse CF, Chung F, Newman S, Stygall J, Wilkinson DJ. Predictors of patient satisfaction with anesthesia and surgery care: a cohort study using the Postoperative Quality of Recovery Scale. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013 Mar;30(3):106-10. Doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328357e584. PMID: 22907610.

- Ryan SM, Nielsen CJ. Global warming potential of inhaled anesthetics: application to clinical use. Anesth Analg. 2010 Jul;111(1):92-8. Doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e058d7. Epub 2010 Jun 2. PMID: 20519425.

- Sebel PS, Bowdle TA, Ghoneim MM, Rampil IJ, Padilla RE, Gan TJ, Domino KB. The incidence of awareness during anesthesia: a multicenter United States study. Anesth Analg. 2004 Sep;99(3):833-839. Doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000130261.90896.6C. PMID: 15333419.

- Servin F, Farinotti R, Haberer JP, Desmonts JM. Propofol infusion for maintenance of anesthesia in morbidly obese patients receiving nitrous oxide. A clinical and pharmacokinetic study. Anesthesiology. 1993 Apr;78(4):657-65. Doi: 10.1097/00000542-199304000-00008. PMID: 8466066.

- Shaikh SI, Nagarekha D, Hegade G, Marutheesh M. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: A simple yet complex problem. Anesth Essays Res. 2016 Sep-Dec;10(3):388-396. Doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.179310. PMID: 27746521; PMCID: PMC5062207.

- Snider TW, Minto CF, Gambus PL, Andresen C, Goodale DB, Shafer SL, Youngs EJ. The Influence of Method of Administration and Covariates of the Pharmacokinetics of Propofol in Adult Volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1998; 88:1170-1182.

- Tanaka P, Goodman S, Sommer BR, Maloney W, Huddleston J, Lemmens HJ. The effect of desflurane versus propofol anesthesia on postoperative delirium in elderly obese patients undergoing total knee replacement: A randomized, controlled, double-blinded clinical trial. J Clin Anesth. 2017 Jun;39:17-22. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.03.015. Epub 2017 Mar 14. PMID: 28494898.

- Van Kralingen S, Diepstraten J, Peeters MY, Deneer VH, van Ramshorst B, Wiezer RJ, van Dongen EP, Danhof M, Knibbe CA. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of propofol in morbidly obese patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011 Nov 1;50(11):739-50. Doi: 10.2165/11592890-000000000-00000. PMID: 21973271.

- Van Lonkhuyzen, L. (2023, April 4). Ziekenhuizen willen narcosegassen sterk terugdringen, maar niet alle artsen doen mee. NRC. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2023/04/03/ziekenhuizen-willen-vervuilende-narcosegassen-sterk-terugdringen-maar-niet-alle-artsen-doen-mee-a4161181

- Visser K, Hassink EA, Bonsel GJ, Moen J, Kalkman CJ. Randomized controlled trial of total intravenous anesthesia with propofol versus inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane-nitrous oxide: postoperative nausea with vomiting and economic analysis. Anesthesiology. 2001 Sep;95(3):616-26. Doi: 10.1097/00000542-200109000-00012. PMID: 11575532.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What are the (un)favorable effects of inhalation anesthesia vs. TIVA during surgery in obese patients undergoing a chirurgical procedure?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Ahmed, 2021

[individual study characteristics deduced from Ahmed, 2021)

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to July 22, 2020

A: Elbakry, 2018 B: Honca, 2017 C: Aftab, 2019 D: Siampalioti, 2015 E: Juvin, 2000

Study design for all included studies: RCT

Setting and Country: A: Egypt B: Turkey C: Norway D: Greece E: France

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: No COI, no funding from pharmaceutical industry B: No competing financial interest C: Grants received and lecture honoraria from Novartis, Bayer, and Pfizer/BMS, and lecture and advisory board honoraria from MSD, Novartis, and Amgen. None of these grants or honoraria is relevant to the submitted work. D: No COI E: Financial support was provided by the De ́le ́gation a` la Recherche Clinique, Assistance Publique-Hoˆpitaux de Paris, Hoˆpital Saint- Louis (Paris, France). |

Inclusion criteria SR: Comparison of TIVA vs inhalation anesthesia in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Only RCTs as identified by the authors of each study.

Exclusion criteria SR: 1) letters, editorials, review articles; 2) nonhuman studies; 3) pediatric populations; 4) studies without mention of intravenous or inhalation anesthesia.

7 studies included by Ahmed (2021), 5 studies included in the current analysis

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N (I/C) A: 50/50 B: 30/31 C: 49+44/52+38 D: 25+25/25+25 E: 12/12/12 (desflurane/ isoflurane/ Propofol)

Age A: I: 35.3 ± 10.4 C: 34.4 ± 11.1 B: I: 40.0 ± 10.1 C: 35.9 ± 11.1 C: I: 43.0 ± 9.8 + 43.0 ± 12.0 C: 44.0 ± 13.0 + 47.0 ± 7.8 D: I: 61.10 ± 10.0 I (BIS): 57.0 ± 9.0 C: 59.0 ± 11.0 C (BIS): 55.0 ± 6.0 E: I (D): 40.1 ± 7.0 I (I): 36.5 ± 8.5 C: 39.7 ± 10.4

BMI A: I: 42.6 ± 4.4 C: 41.6 ± 4.4 B: I: 43.5 ± 4.5 C: 44.5 ± 4.6 C: I: 43.0 ± 7.0 + 43.0 ± 4.8 C: 41.0 ± 5.9 + 41.0 ± 5.3 D: I: 42.0 ± 8.0 I (BIS): 36.0 ± 10.0 C: 36.0 ± 9.0 C (BIS): 37.0 ± 9.0 E: I (D): 46.5 ± 5.3 I (I): 47.5 ± 4.9 C: 44.3 ± 4.0

Sex: A: I: 70.0% F C: 66.0% F B: I: 70.0% F C: 93.6% F C: I: 80.0% + 73.0% F C: 79.0% + 76.0% F D: Sex: I: 60.0% F I (BIS): 72.0% F C: 68.0% F C (BIS): 76.0% F E: Sex: I (D): 75.0% F I (I): 83.3% F C: 83.3% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

A: desflurane 60/40% oxygen air mixture BIS: 40–60 with 0.5 μg/kg remifentanil B: Maintenance: desflurane C: remifentanil and desflurane D: end-tidal sevoflurane concentrations of 1–3% via fresh gas flow 6 L/ E: desflurane (12 patients) or isoflurane (12 patients). The Propofol TCI was stopped after induction. BIS: 45–55

|

Describe control:

A: Propofol 100–200 μg/kg/min and Dexmedetomidine 0.5–1.0 μg/kg/h BIS: 40–60 with 0.5 μg/ kg remifentanil B: Propofol 21 mg/ kg CBW for 5 min, 12 mg/kg CBW for 10 min and then 6 mg/kg CBW BIS: 45–55 C: Propofol and remifentanil D: Propofol 6–10 mg/kg/h CBW and remifentanil 0.1–1.0 μg/kg/min. Bolus remifentanil 1 μg/kg IBW for every rise in BP/HR > 15% baseline with continuous infusion remifentanil 1.0 μg/ kg/min. BIS: 40–55 E: Propofol BIS: 45–55

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 24 hours B: postoperative C: 24 hours D: postoperative E: postoperative

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: 0/0 B: 1/0 C: 0/0 D: 0/0 E: 0/1/1

|

Outcome measure-1: Pain scores 1a. Immediate postoperative pain scores (30 min)

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95% CI]: A: - B: - C: - D: 0.30 [-0.63 to 1.23] E: Desflurane vs Propofol: -0.37 [-2.21 to 1.47] Isoflurane vs Propofol: 1.03 [-0.94 to 3.00]

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.11 [95% CI 0.88 to 0.66] favoring control. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

1b. 24h postoperative pain scores

Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]: A: -2.23 [-2.93 to -1.53] B: Not reported C: 0.04 [-0.48 to 0.56] D: - E: -

Pooled effect (random effects model): -1.08 [95% CI -3.31 to 1.14] favoring control. Heterogeneity (I2): 96%

Outcome measure 2: PONV 2a. Postoperative nausea

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.33 [0.13 to 0.85] B: 0.65 [0.31 to 1.35] C: - D: - E: Desflurane vs Propofol: -1.00 [0.25 to 4.00] Isoflurane vs Propofol: 0.75 [0.21 to 2.66]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.54 [95% CI 0.31 to 0.94] favoring control. Heterogeneity (I2): 17%

2b. postoperative vomiting

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.21 [0.07 to 0.70] B: 2.91 [0.12 to 68.66] C: - D: - E: Desflurane vs Propofol: -0.50 [0.05 to 4.81] Isoflurane vs Propofol: -0.50 [0.05 to 4.81]

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.31 [95% CI 0.13 to 0.74] favoring control. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

Other drugs (identical for both groups): A: Preoperative: sodium citrate 15 mL PO, ondansetron 5 mg Induction: 0.5–1.0 μg/kg remifentanil, 2–3 mg/kg Propofol, and 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium B: Induction: Propofol 2 mg/ kg IBW and fentanyl 1 mg/kg IBW Intraoperative: crystalloid 7 mL/kg , remifentanil 0.1–1.0 u/kg/min C: Preoperative: antibiotics, thrombosis prophylaxis with LMWH, glycopyron 0.2 mg, metoclopramide 20 mg, sodium citrate 30 mL PO, dexamethasone 16 mg (ompazine 10 mg as first line). D: Induction: dose on IBW or CBW E: Induction: Propofol initial blood concentration 8 μg/mL Intraoperative: succinylcholine 1.2 mg/kg, 50 mg and 50 mg

Risk of bias (high, some concerns or low): A: Low B: High C: Some concerns D: Some concerns E: High

Author conclusion: “our systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs suggest that compared to inhalation anesthesia, TIVA reduces the occurrence of PONV in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. In a population particularly susceptible to PONV, our evidence suggests the superiority of TIVA over volatile anesthetics with moderate certainty. Future rigorous and larger randomized trials are needed to investigate the variety of measures to assess recovery after surgery in this high-risk surgical population.”

Excluded studies for the current literature review:

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

Research question: What are the (un)favorable effects of inhalation anesthesia vs. TIVA during surgery in obese patients undergoing a chirurgical procedure.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control I 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Gaszyński, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country:

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: Obese patients (BMI > 33) undergoing bariatric surgery

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 60 Control: 60

Important prognostic factors2: BMI (range) (SD not reported): I: 45.1 (33.8 to 57.4) C: 42.7 (35 to 58.1)

Age (range) (SD not reported): I: 40.0 (18 to 65) C: 35.9 (17 to 64)

Sex: I: 80.0% F C: 66.7% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Sevoflurane concentration according to patients age and modified based on clinical parameters (in order to maintain haemodynamic stability).

Fresh gas flow was set at: - 4 L/min in the beginning of anesthesia - 1 L/min after 10 minutes - 2 L/min after 1 hour

|

The following concentrations of Propofol infusions were used:

Induction: 1.5−2.0 mg kg-2 of corrected body weight (calculated as: IBV [ideal body weight] + 0.4 × [total body weight–ideal body weight]);

Infusion concentration was: - 10 mg/kg/h in the beginning of anesthesia - 8 mg/kg/h after 10 minutes - 6 mg/kg/h to end the administration of anesthesia

|

Length of follow-up: 2 hours after anesthesia

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: No loss-to-follow-up

Control: No loss-to-follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: No incomplete data

Control: No incomplete data

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

I: 0 (0%) C: 0 (0%) |

Other drugs (identical for both groups): - Rocuronium for muscle relaxation - Neuromuscular blockade was monitored using a TOF-Guard device - Sugammadex for reversing the neuromuscular block (at completion) - Midazolam (0.05 mg/kg of IBW) as premedication on arrival - Intravenous fentanyl for intraoperative analgesia |

|

Demirel, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Department of Anesthesiology and General Surgery, Fırat University Medical Faculty Hospital, Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: no financial support, no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Morbidly obese patients (BMI>40 kg/m2), between the ages of 21 and 60 years, scheduled to undergo elective-sleeve gastrectomy.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with cardiovascular, pulmonary, endocrinological, and psychiatric disorders

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30+30 Control: 30+30 (For both intervention and control: PSI and no-PSI groups)

Important prognostic factors2: BMI ± SD: I (D-PSI): 45.6±5.6 I (D): 50.1±16.4 C (P-PSI): 50.5±14.7 C (P): 45.5±3.9

Age ± SD: I (D-PSI): 35.0±13.0 I (D): 34.4±11.6 C (P-PSI): 37±10.6 C (P): 34.4±10.4

Sex: I (D-PSI): 73.3% I (D): 70% C (P-PSI): 70% C (P): 53.3%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Induction in groups D-PSI and group D: 2 mg/kg of Propofol in accordance with CBW. About 1 mcg/kg bolus dose of remifentanil according to IBW was administered for more than 30 to 60 seconds. About 0.6 mg/kg of rocuronium was administered to optimize endotracheal intubation in line with IBW.

Maintenance of anesthesia: - In group D-PSI, desflurane concentration was adjusted to maintain a PSI value of 25 to 50 - Group D was treated to have an end-tidal desflurane concentration of approximately 6%.

|

Induction in groups P-PSI and P: 2 mg/kg of Propofol in accordance with CBW. About 1 mcg/kg bolus dose of remifentanil according to IBW was administered for more than 30 to 60 seconds, and 0.6 mg/kg of rocuronium, based on IBW, was to optimize endotracheal intubation.

Maintenance of anesthesia: - Group P-PSI received a Propofol infusion to maintain a PSI level of 25 to 50 - Group P received a 6 to 10 mg/kg/h Propofol infusion according to CBW.

|

Length of follow-up: Not reported. At least until PACU discharge.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: No loss-to-follow-up

Control: No loss-to-follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: No incomplete data

Control: No incomplete data

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

1a. Nausea I (D-PSI group): 3 (10%) I (D-group): 4 (13%) C (P-PSI group): 8 (27%) C (P-group): 16 (53%) p<0.05 (group P-PSI, group P, and group D-PSI compared with group D)

1b. Vomiting I (D-PSI group): 2 (7%) I (D-group): 3 (10%) C (P-PSI group): 4 (13%) C (P-group): 4 (13%) p<0.05 (group P-PSI, group P, and group D-PSI compared with group D)

|

Other drugs (identical for both groups): - 0.1 to 1 mcg/kg/min of remifentanil infusion according to the IBW for analgesia - Rocuronium for neuromuscular blockage - in case of >20% increase in heart rate or blood pressure: a bolus of remifentanil, 1 mcg/kg of IBW, followed by an increase in the continuous infusion of remifentanil until hemodynamic parameters returned to baseline. - In case of >20% reduction in blood pressure; reduction of remifentanil - If blood pressure did not return to baselines values; 10 mg of ephedrine - If heart rate was <45/min; 0.5 mg bolus dose of atropine - The reversal of neuromuscular blockade was performed using sugammadex.

|

|

Tanaka, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: supported by a research grant from Baxter Healthcare Corporation |

Inclusion criteria: Age over 65 undergoing elective TKA, ASA physical health Class of II or III, and a body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2

Exclusion criteria: patient refusal of or failure of regional block; pre-existing neurocognitive disorders [Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≤ 23]; and known intolerance to any of the drugs

Important prognostic factors2: BMI (mean): I: 36.5 C: 34.0

Age (mean): I: 69.8 C: 70.6

Sex: I: 44.4% F C: 66.7% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Anesthesia was maintained with desflurane.

The maintenance agent was titrated to a PSI of 30–50 using the algorithm described in the supplemental con- tent.

Following surgery, a continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 6 ml/h was initiated in the recovery room and adjusted to a maximum of 10 ml/h for the next 48 h. |

Anesthesia was maintained with Propofol.

The maintenance agent was titrated to a PSI of 30–50 using the algorithm described in the supplemental con- tent.

Following surgery, a continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 6 ml/h was initiated in the recovery room and adjusted to a maximum of 10 ml/h for the next 48 h. |

Length of follow-up: Follow-up for pain, nausea and vomiting was 6 to 8 hours. Other outcomes had a longer follow-up (cognitive tests – 48 hours).

Loss-to-follow-up:

4 patients withdrew from the study because they did not want to proceed with testing*

Incomplete outcome data:

6 out of 96 patients did not complete full CAM testing due to early hospital discharge (n = 2), oversedation (n = 3), and respiratory distress (n = 1)*

Eleven of these 90 patients did not complete the battery of cognitive tests due to oversedation (n = 5) or nausea and vomiting, pain, and respiratory distress (n = 6)*

*it in not mentioned to which group the patients lost to follow-up were assigned |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain – 60 min post op (mean ± SD) I: 3.68 ± 3.40 C: 3.7 ± 2.86

Nausea 1 hour postop: I: 7.32% C: 4.88% 6-8 hours postop I: 12.2% C: 12.2%

Vomiting 1 hour postop I: 4.88% C: 0% 6-8 hours postop I: 7.32% C: 2.44% |

Author’s conclusion:

among obese elderly patients undergoing TKA, we found a very low incidence of delirium but were unable to show a difference, in the sample size studied, among the choice of desflurane or Propofol for maintenance, on the incidence of postoperative delirium, early cognitive outcomes, or wake up times. |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research question: What are the (un)favorable effects of inhalation anesthesia vs. TIVA during surgery in obese patients undergoing a chirurgical procedure.

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Aftab, 2019 (included in Ahmed 2021) |

Probably yes.

|

Probably no.

Not reported. |

Definitely yes.

The surgeons, postoperative nursing staff, anesthesiologist, and the staff at the obesity clinic were blinded to the type of anesthesia the patient was given. Patients not reported.

|

Definitely yes.

No missing data. |

Probably yes.

Study protocol is not available. Outcomes mentioned in the methods match outcomes reported in the results section. |

Definitely yes. |

SOME CONCERNS

Due to: blinding and allocation concealment not reported. No protocol available.

|

|

Honca, 2017 (included in Ahmed 2021) |

Probably yes.

Patients were randomized using a closed envelope method to one of two equal groups (Group I, Propofol, or Group II, desflurane).

|

Probably no.

Not reported. |

Probably no.

The time from discontinuation of the study drug to eye opening and extubation was recorded by a blinded study person. For all other people involved (including patients), blinding is not reported.

|

Definitely yes.

One participant lost during follow-up with reason clearly reported. |

Probably yes.

Study protocol is not available. Outcomes mentioned in the methods match outcomes reported in the results section. |

Definitely yes. |

HIGH

Due to: only minimal blinding, allocation concealment not reported. No protocol available.

|

|

Siampalioti, 2015 (included in Ahmed 2021) |

Definitely yes.

All patients were randomly divided into four groups via a computer-generated random number table.

|

Probably no.

Not reported. |

Probably yes.

Both the anesthesiologist per- forming the assessment and the patients were blinded to the general anesthetic used and the BIS monitoring Investigators are not mentioned to be blinded. |

Definitely yes.

No missing data. |

Definitely yes.

Study protocol is published on ClinicalTrials.gov and matches study results. |

Definitely yes.

|

SOME CONCERNS

Due to: no blinding of investigators, and allocation concealment not reported. |

|

Juvin, 2000 (included in Ahmed 2021) |

Probably no.

Not reported. |

Probably no.

Not reported. |

probably no.

Postoperative recovery (i.e., from PACU admission to PACU discharge) was assessed by a single investigator blinded to the patient groups, whereas the single anesthesiologist who performed anesthesia was not blinded. Patients blinding was not reported.

|

Definitely yes.

Two patients lost for follow up with reason clearly described. |

Probably yes.

Study protocol is not available. Outcomes mentioned in the methods match outcomes reported in the results section. |

Definitely yes.

|

HIGH

Due to: only minimal blinding, randomization and allocation concealment not reported. No protocol available.

|

|

Elbakry, 2018 (included in Ahmed 2021) |

Definitely yes.

A computer software program (GraphPad software QuickCalcs, Inc.California, USA) was used to randomly assign the patients into the two groups.

|

Probably no.

Not reported. |

Definitely yes.

Patients, surgeons and the research team were blinded to the randomization. An independent anaesthetist prepared the for the research team. Infusions and data collection were done by another anaesthetist who was not informed of the types of drugs being used. |

Definitely yes.

No missing data. |

Probably yes.

Study protocol is not available. Outcomes mentioned in the methods match outcomes reported in the results section. |

Definitely yes.

|

LOW |

|

Gaszyński, 2016 |

Probably yes.

Patients were randomly allocated. Method not described. |

Probably no.

Not reported. |

Probably yes.

The anesthesiologist performing the anesthesia was blinded to the BIS monitor. Whether the anesthesiologist was also blinded to the drugs that were administered is not reported.

|

Definitely yes.

No missing data. |

Probably yes.

Study protocol is not available. Outcomes mentioned in the methods match outcomes reported in the results section. |

Definitely yes.

|

SOME CONCERNS

Due to: blinding not clearly reported, method for randomization not reported, allocation concealment not reported, no study protocol available. |

|

Demirel, 2021 |

Probably yes.

|

Probably no.

Not reported. |

Probably yes.

The anesthesiologist who evaluated the patients in the PACU was blinded to the anesthesia method and the groups of patients undergoing PSI monitoring. All data were collected by a blinded investigator. Patients not reported to be blinded or not.

|

Definitely yes.

No missing data. |

Probably yes.

Study protocol is not available. Outcomes mentioned in the methods match outcomes reported in the results section. |

Definitely yes.

|

SOME CONCERNS

Due to: blinding of patients not clearly reported, method for randomization not reported, allocation concealment not reported, no study protocol available. |

|

Tanaka, 2017 |

Probably yes.

Randomization by research coordinator via computer generated random numbers. |

Probably no.

Not reported. |

Probably yes.

The anesthesiologist was not blinded, but the surgeons, study investigators, and patients were blinded to randomization.

|

Probably no.

Four patients withdrew from study participation because they did not want to proceed with testing and six patients did not complete all tests due to early discharge (n=2), oversedation (n=3), respiratory distress (n=1). |

Definitely yes.

Study protocol is published on ClinicalTrials.gov and matches study results. |

Definitely yes. |

SOME CONCERNS

Due to: Randomization method and allocation concealment are not clearly described, high number of dropouts. |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Hu ZH, Liu Z, Zheng GF, Li ZW, Liu SQ. Postoperative Recovery Outcomes for Obese Patients Undergoing General Anesthesia: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Surg. 2022 Jul 28;9:862632. Doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.862632. PMID: 35965859; PMCID: PMC9366090. |

Only four included studies match our PICO and these four studies are individually selected or included in the review of Ahmed (2021) |

|

Aftab H, Fagerland MW, Gondal G, Ghanima W, Olsen MK, Nordby T. Pain and nausea after bariatric surgery with total intravenous anesthesia versus desflurane anesthesia: a double blind, randomized, controlled trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019 Sep;15(9):1505-1512. Doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2019.05.010. Epub 2019 May 14. PMID: 31227317. |

Included in review Ahmed (2021) |

|

Arain SR, Barth CD, Shankar H, Ebert TJ. Choice of volatile anesthetic for the morbidly obese patient: sevoflurane or desflurane. J Clin Anesth. 2005 Sep;17(6):413-9. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.12.015. PMID: 16171660. |

Wrong comparison: No comparison with TIVA |

|

Ashoor TM, Kassim DY, Esmat IM. A Randomized Controlled Trial for Prevention of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Aprepitant/Dexamethasone vs. Mirtazapine/Dexamethasone. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2022 Apr 30;2022:3541073. Doi: 10.1155/2022/3541073. PMID: 35535050; PMCID: PMC9078838. |

Wrong intervention and comparison |

|

Babayiğit M, Can ME, Bulus H, Dereli N, Ozayar E, Kurtay A, & Horasanli E. Prospective Randomized trial on the effects of sevoflurane and Propofol on the intraocular pressure in bariatric surgery. Bariatric Surgical Practice and Patient Care, 2020;15(4), 216-222. |

Wrong outcome: MAP, HR, IOP |

|

Bansal T, Garg K, Katyal S, Sood D, Grewal A, Kumar A. A comparative study of desflurane versus sevoflurane in obese patients: Effect on recovery profile. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2020 Oct-Dec;36(4):541-545. Doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_307_19. Epub 2021 Jan 18. PMID: 33840938; PMCID: PMC8022057. |

Wrong comparison: no comparison with TIVA |

|

Carron M, Tessari I, Linassi F, Navalesi P. Desflurane versus Propofol for general anesthesia maintenance in obese patients: A pilot meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2021 Feb;68:110103. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.110103. Epub 2020 Oct 16. PMID: 33075628. |

Wrong publication type: Letter to the editor |

|

Cooke FE, Samuels JD, Pomp A, Gadalla F, Wu X, Afaneh C, Dakin GF, Goldstein PA. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Intravenous Acetaminophen on Hospital Length of Stay in Obese Individuals Undergoing Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2018 Oct;28(10):2998-3006. Doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3316-7. PMID: 29948869. |

Wrong comparison: no comparison with TIVA |

|

De Baerdemaeker LE, Jacobs S, Den Blauwen NM, Pattyn P, Herregods LL, Mortier EP, Struys MM. Postoperative results after desflurane or sevoflurane combined with remifentanil in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2006 Jun;16(6):728-33. Doi: 10.1381/096089206777346691. PMID: 16756732. |

Wrong comparison: no comparison with TIVA |

|

de Sousa GC, Cruz FF, Heil LB, Sobrinho CJS, Saddy F, Knibel FP, Pereira JB, Schultz MJ, Pelosi P, Gama de Abreu M, Silva PL, Rocco PRM. Intraoperative immunomodulatory effects of sevoflurane versus total intravenous anesthesia with Propofol in bariatric surgery (the OBESITA trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled pilot trial. Trials. 2019 May 28;20(1):300. Doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3399-z. PMID: 31138279; PMCID: PMC6540380. |

Wrong publication type: study protocol |

|

Dong D, Peng X, Liu J, Qian H, Li J, Wu B. Morbid Obesity Alters Both Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Propofol: Dosing Recommendation for Anesthesia Induction. Drug Metab Dispos. 2016 Oct;44(10):1579-83. Doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.071605. Epub 2016 Aug 1. PMID: 27481855. |

Wrong comparison: determination of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Propofol in two dosing regimens |

|

Elbakry AE, Sultan WE, Ibrahim E. A comparison between inhalational (Desflurane) and total intravenous anesthesia (Propofol and Dexmedetomidine) in improving postoperative recovery for morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2018 Mar;45:6-11. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.12.001. Epub 2017 Dec 8. PMID: 29223575. |

Included in review Ahmed (2021) |

|

Farid AM, Taman HI. The Impact of Sevoflurane and Propofol Anesthetic Induction on Bag Mask Ventilation in Surgical Patients with High Body Mass Index. Anesth Essays Res. 2020 Oct-Dec;14(4):594-599. Doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_20_21. Epub 2021 May 27. PMID: 34349326; PMCID: PMC8294424. |

No comparison |

|

Gaszynski TM, Strzelczyk JM, Gaszynski WP. Post-anesthesia recovery after infusion of Propofol with remifentanil or alfentanil or fentanyl in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2004 Apr;14(4):498-503; discussion 504. Doi: 10.1381/096089204323013488. PMID: 15130225. |

Wrong medication investigated |

|

Honca M, & Honca T. Comparison of Propofol with desflurane for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in morbidly obese patients: a prospective randomized trial. Bariatric Surgical Practice and Patient Care. 2017;12(2), 49-54. |

Included in review Ahmed (2021) |

|

Hussain Z, Curtain C, Mirkazemi C, Zaidi STR. Peri-operative Medication Dosing in Adult Obese Elective Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. Clin Drug Investig. 2018 Aug;38(8):673-693. Doi: 10.1007/s40261-018-0662-0. PMID: 29855999. |

Wrong comparison: different dosing regimens |

|

Juvin P, Vadam C, Malek L, Dupont H, Marmuse JP, Desmonts JM. Postoperative recovery after desflurane, Propofol, or isoflurane anesthesia among morbidly obese patients: a prospective, randomized study. Anesth Analg. 2000 Sep;91(3):714-9. Doi: 10.1097/00000539-200009000-00041. PMID: 10960406. |

Included in review Ahmed (2021) |

|

Kasputytė G, Gecevičienė P, Karbonskienė A, Macas A, Maleckas A. Comparison of Postoperative Recovery after Manual and Target-Controlled Infusion of Remifentanil in Bariatric Surgery. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021 Oct 16;57(10):1114. Doi: 10.3390/medicina57101114. PMID: 34684151; PMCID: PMC8540661. |

Wrong comparison: comparing way of administration |

|

Kaur A, Jain AK, Sehgal R, Sood J. Hemodynamics and early recovery characteristics of desflurane versus sevoflurane in bariatric surgery. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013 Jan;29(1):36-40. Doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.105792. PMID: 23493107; PMCID: PMC3590538. |

Wrong comparison: no comparison with TIVA |

|

Kaya, C, Cebeci, H, Tomak, L, & Ozbalci, GS. Prospective Randomized Trial Between Propofol Intravenous and Sevoflurane Inhaled Anesthesia on Cerebral Oximetry. Bariatric Surgical Practice and Patient Care. 2020; 15(3), 160-168. |

Wrong outcome measures |

|

Kim JW, Lee JY, Hwang SW, Kang DH, Ryu SJ, Kim DS, Kim JD. The Effects of Switching from Sevoflurane to Short-Term Desflurane prior to the End of General Anesthesia on Patient Emergence and Recovery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Biomed Res Int. 2022 Jul 6;2022:1812728. Doi: 10.1155/2022/1812728. PMID: 35845953; PMCID: PMC9279063. |

Wrong comparison: no comparison with TIVA |

|

Krieg H, Rabe B, Schroder T, Kloppick, E. and Kox, W. J. Comparison of a balanced anesthesia with desflurane, sevoflurane and intravenous anesthesia with Propofol and remifentanil in obese patients. Journal fur Anasthesie und Intensivbehandlung. 2000. |

Wrong language (German) |

|

La Colla L, Albertin A, La Colla G, Mangano A. Faster wash-out and recovery for desflurane vs sevoflurane in morbidly obese patients when no premedication is used. Br J Anaesth. 2007 Sep;99(3):353-8. Doi: 10.1093/bja/aem197. Epub 2007 Jul 9. PMID: 17621601. |

Wrong comparison: no comparison with TIVA |

|

Lam F, Liao CC, Lee YJ, Wang W, Kuo CJ, Lin CS. Different dosing regimens for Propofol induction in obese patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2013 Jun;51(2):53-7. Doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2013.06.009. Epub 2013 Aug 1. Erratum in: Asian J Anesthesiol. 2017 Jun 16;: PMID: 23968654. |

Wrong comparison: different dosing regimens |

|

Liu FL, Cherng YG, Chen SY, Su YH, Huang SY, Lo PH, Lee YY, Tam KW. Postoperative recovery after anesthesia in morbidly obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2015 Aug;62(8):907-17. Doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0405-0. Epub 2015 May 22. PMID: 26001751. |

Only two studies included that match our PICO. These two studies are individually selected or included in the review of Ahmed (2021). |

|

Malone M. Altered drug disposition in obesity and after bariatric surgery. Nutr Clin Pract. 2003 Apr;18(2):131-5. Doi: 10.1177/0115426503018002131. PMID: 16215030. |

Wrong comparison: overview of drugs that are used in obesity. |

|

Öztürk MC, Demiroluk Ö, Abitagaoglu S, Ari DE. The Effect of sevoflurane, desflurane and Propofol on respiratory mechanics and integrated pulmonary index scores in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. A randomized trial. Saudi Med J. 2019 Dec;40(12):1235-1241. Doi: 10.15537/smj.2019.12.24693. PMID: 31828275; PMCID: PMC6969621. |

Wrong comparison and wrong outcome measures |

|