Methode van beademing - Buikligging

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van buikligging bij beademde patiënten met matig-ernstige ARDS?

Aanbeveling

Pas beademing in buikligging toe bij ARDS-patiënten die gecontroleerd worden beademd en een PaO2/FiO2 ratio <150 mmHg hebben, en géén absolute contra-indicatie hebben voor buikligging (instabiele wervelfractuur):

- Start direct na het optreden van PaO2/FiO2 ratio <150 mmHg, tenzij dit om logistieke of praktische redenen niet haalbaar is.

- Pas minimaal 16 uur per dag buikligging toe, en niet langer dan 20 uur per sessie.

- Wees alert op het optreden van complicaties (denk aan decubitus en endotracheale tube obstructie, maar ook aan schouder luxatie).

- Continueer beademing met lage teugvolumes (zie module ‘Methode van beademing - Volumina’ voor optimalisatie van beademings instellingen).

- Evalueer de veranderingen in respiratoire mechanica, d.w.z. een reductie in plateaudruk en driving pressure (in volume-gecontroleerde modus, of druk-gecontroleerde modus met streef teugvolume) en toename in teugvolume (druk-gecontroleerde modus) aan het einde van de eerste sessie van de buikligging.

Verlaag de pressure control indien het teugvolume in buikligging is toegenomen. - Overweeg de verandering in PaO2/FiO2 ratio tijdens buikligging te gebruiken om de beademingsinstellingen te optimaliseren (afbouwen FiO2 en PEEP indien mogelijk).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd naar het effect van mechanische ventilatie in buikligging vergeleken met rugligging bij patiënten met ARDS.

Beademing in buikligging bij een patiënt met matig-ernstige ARDS waarbij buikligging binnen 48 uur na het starten van de invasieve gecontroleerde beademing en tenminste voor 16 uur per dag wordt toegepast, geeft waarschijnlijk een lagere mortaliteit (cruciale uitkomstmaat) vergeleken met beademing in rugligging (redelijke bewijskracht). De overweging om te starten met buikligging in patiënten met matig-ernstige ARDS is met name is gebaseerd op de PROSEVA-trial (Guerin, 2013). Het grootste effect van buikligging is te verwachten in patiënten met ernstige hypoxemie, omdat in de PROSEVA-trial (Guerin, 2013) alleen ARDS-patiënten met PaO2/FiO2 ratio <150 mmHg zijn geïncludeerd.

Voor mild-matige ARDS-patiënten, patiënten die later starten met buikligging, en patiënten die korter dan 16 uur per dag in buikligging worden beademd is het effect van buikligging op het verbeteren van de uitkomst onduidelijk (zeer lage/geen bewijskracht). De zeer lage bewijskracht werd vooral veroorzaakt door het risico op bias door de studieopzet en de brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen. De PaO2/FiO2 ratio op dag 7 tot 10 (belangrijke uitkomstmaat) was klinisch relevant verschillend voor de groep patiënten die in buikligging werd beademd vergeleken met de groep die in rugligging werd beademd (lage bewijskracht). De uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven werd niet gerapporteerd in de geïncludeerde studies.

Verder zijn er in de literatuur meerdere complicaties beschreven. Deze werden, door de werkgroep, allen aangemerkt als belangrijke uitkomstmaat voor de besluitvorming.

Het risico op ongeplande extubatie van de endotracheale tube is waarschijnlijk niet verschillend bij patiënten die worden beademd in buikligging in vergelijking met patiënten die worden beademd in rugligging (redelijke bewijskracht). Endotracheale tube obstructie lijkt wel vaker voor te komen bij patiënten die op de buik gedraaid worden (lage bewijskracht). Er lijkt een verschil te zijn in het optreden van drukplekken, met een hogere incidentie in buikligging (lage bewijskracht). Ondanks de lage bewijskracht is de werkgroep van mening dat preventieve maatregelen noodzakelijk zijn om het risico op (of het verergeren van) decubitus te verminderen. Het effect van beademing in buikligging op ongeplande centraal veneuze katheter verwijdering en pneumonie is onduidelijk (zeer lage bewijskracht). Belangrijk is dat het team alert is op het ontstaan van mogelijke complicaties bij de buikligging en tijdens het draaien, en voorzorgsmaatregelen neemt (zie paragraaf Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie).

Hoewel op basis van de uitgevoerde sensitiviteitsanalyses niet goed bepaald kan worden of factoren zoals moment van starten en de duur van buikligging een causaal verband laten zien met de uitkomst, lijken met name patiënten waarbij vroegtijdig gestart is met buikligging en buikligging voor meer dan 16 uur per dag heeft plaatsgevonden baat te hebben bij buikligging Dit wordt niet duidelijk aangetoond bij andere subgroepen (start en duur buikligging).

Op basis van de PROSEVA trial (Guerin, 2013) zou buikligging in ieder geval binnen 48 uur na het optreden van PaO2/FiO2 ratio <150 mmHg moeten gebeuren. Deze tijdsperiode van 48 uur die in de literatuur staat beschreven is met name het resultaat van het uitvoeren van wetenschappelijk onderzoek (denk aan de tijd benodigd voor het verkrijgen van informed consent voor studiedeelname). Het te verwachten effect van buikligging is volgens de werkgroep echter het grootst als er zo snel mogelijk wordt gestart met buikligging, om daarmee de kans op het optreden van additionele longschade zoveel mogelijk te verminderen (Guerin, 2020). Om die reden is de werkgroep van mening dat er na het instellen van de beademing zo snel mogelijk gestart zou moeten worden met buikligging tenzij dit om klinische of logistieke redenen niet mogelijk is of het te verwachten is dat de oxygenatie na het instellen van de beademing binnen enkele uren dermate verbetert dat buikligging niet meer geïndiceerd is.

Buikligging laat daarnaast een positief effect op de uitkomst zien wanneer buikligging langer dan 16 uur per dag wordt toegepast. De optimale duur van buikligging is echter discutabel en meta-analyses en internationale richtlijnen rapporteren zowel afkappunten van 12 als 16 uur. In studies waarin buikligging werd toegepast voor <16 uur, was de duur van buikligging <12 uur. Vice versa, in studies waarin buikligging werd toegepast voor >12 uur, was de duur van buikligging >16 uur. De werkgroep heeft de aanbeveling van een minimale duur van 16 uur overgenomen vanuit een recente meta-analyse (Bloomfield, 2015). Er zijn geen gerandomiseerde studies verricht naar het effect van langere opeenvolgende periodes (> 24 uur) van behandeling in buikligging. Een recente review heeft de resultaten van observationele studies naar de effecten van langere ligduur in buikligging samengevat (Walter, 2023). Op basis van fysiologisch onderzoek is het aannemelijk dat de positieve effecten van buikligging langer aanhouden bij langere ligduur in buikligging. Potentiële nadelen zijn toename van decubitus, plexopathie en mogelijk toename van centraal veneuze katheter gerelateerde infecties. Omdat er nog geen gerandomiseerde studies zijn gedaan naar de uitkomsten van een langere behandelduur in buikligging lijkt het schappelijk de maximale duur in buikligging gelijk te houden aan de maximale ligduur in buikligging die in de PROSEVA trial (Guerin, 2013) is toegepast. Daar werd gestimuleerd om sessies tenminste 16 uur te laten duren, wat resulteerde in een gemiddelde ligduur in buikligging van 17 +/- 3 uur; waardoor de patient dus na 20 uur weer terug gedraaid zou moeten worden. De werkgroep is van mening dat indien een langere ligduur in buikligging (>20 uur) wordt toegepast er voldoende alertheid moet zijn op het ontwikkelen van complicaties zodat deze tijdig kunnen worden behandeld.

De verbetering van PaO2/FiO2 ratio op dag 7 tot 10 (lange termijn) suggereert dat buikligging heeft geresulteerd in long-protectieve beademing. Het is echter belangrijk om op te merken dat de PaO2/FiO2 ratio verandering op dag 7 tot 10 een andere parameter is dan de verandering in PaO2/FiO2 ratio binnen enkele uren na het toepassen van buikligging. De verbetering van PaO2/FiO2 ratio direct na het toepassen van buikligging is geen voorspeller voor survival in ARDS (Albert, 2014), maar het geeft een mogelijkheid om beademingsinstellingen verder te optimaliseren (zoals het afbouwen van FiO2 en PEEP). Ook is belangrijk te noemen dat patiënten die geen directe oxygenatie verbetering tonen nog steeds voordelige effecten van buikligging kunnen ervaren (in lijn met positieve uitkomsten van de PROSEVA-trial). Dit komt waarschijnlijk door verbeterde respiratoire mechanica waardoor de kans op ventilator-induced lung injury vermindert. Dit benadrukt tevens dat de voordelige effecten van buikligging bij ernstige ARDS primair het resultaat zijn van verbetering in long homogeniteit (compliantie) en de geassocieerde reductie in regionale stress en strain. En secundair daaraan de verbetering in oxygenatie gemeten als de PaO2/FiO2 ratio op dag 7 tot 10. Omdat de directe effecten van buikligging tijdsafhankelijk zijn kunnen deze het beste aan het einde van de buikligging sessie worden gemeten. Deze directe effecten zijn eenvoudig te meten als een reductie in plateaudruk en driving pressure (in volume-gecontroleerde modus, of druk-gecontroleerde modus met streef teugvolume) en toename in teugvolume (druk-gecontroleerde modus) bij responders.

Het continueren van long-protectieve beademing is ook van belang in buikligging, en daarom wordt aanbevolen om lage teugvolumes te handhaven. Voor de onderbouwing en uitvoering hiervan verwijst de werkgroep naar de module ‘Methode van beademing – Volumina’. Dit is met name van belang tijdens pressure control beademing waar tijdens buikligging het teugvolume kan toenemen. In dit geval dient de inspiratoire druk in pressure control te worden verlaagd.

De term responder wordt volgens de APRONET trial (Guerin, 2018) gebruikt om de indicatie voor een vervolgbehandeling in buikligging. De term responder slaat op verbetering in PaO2/FiO2 ratio of op verlaging van plateaudruk bij gelijkblijvend teugvolume. In de PROSEVA trial (Guerin, 2013) werden aanvullende behandelingen in buikligging verricht zolang de indicatie voor buikligging (PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 150 mmHg) bleef bestaan. Buikligging werd pas gestopt bij een PaO2/FiO2 ratio > 150 mmHg bij PEEP ≤ 10 cm H2O en FiO2 ≤ 60%. Er is geen literatuur die de waarde van onderscheid tussen responder en non-responder beschrijft zodat dit als kennishiaat kan worden aangemerkt.

De enige absolute contra-indicatie voor het toepassen van buikligging is een instabiele wervelfractuur. Het toepassen van buikligging in situaties van relatieve contra-indicaties (zoals bijv. hemodynamische instabiliteit, zwangerschap, instabiele bekkenfracturen, open thorax en open buikwonden) dient op individueel patiënt niveau besproken te worden door het behandelend team. Obesitas moet niet worden gezien als een relatieve contra-indicatie, deze patiënten hebben vaak juist baat bij buikligging. In geval van verslechtering van oxygenatie of toename van plateaudruk bij patiënten met centrale obesitas kan worden overwogen buikligging in een zandbed toe te passen.

Naast de in de literatuursamenvatting gerapporteerde adverse events, zijn er ook andere complicaties mogelijk, zoals schouderluxatie en chronische nekklachten. De werkgroep is van mening dat complicaties mogelijk gerelateerd zijn aan de ervaring van het draaiteam. Nekklachten zijn mogelijk gerelateerd aan de lange behandelduur in buikligging (>20 uur per dag).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Beademing in buikligging t.o.v. in rugligging suggereert een verbeterde kans op overleving door het verminderen van (de risico’s op) secundaire longschade tijdens de kunstmatige beademing. Dit is de belangrijkste reden om buikligging toe te passen. Buikligging is een eenvoudige en relatief veilige interventie. Potentiële relevante nadelige gevolgen voor de patiënt zijn het optreden van decubitus en het risico op schouderproblemen en chronische nekklachten, wat ook na afloop van de IC opname zorg kan behoeven. Met de juiste maatregelen (wisselligging, speciaal matras) kan verergering van decubitus worden voorkomen.

Beademing van patiënten in buikligging is een interventie die veel impact heeft op de patiënt en zijn/haar naasten. Het is noodzakelijk hier pro-actief aandacht en begeleiding aan te schenken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn in principe geen additionele kosten verbonden aan het toepassen van buikligging, tenzij er speciale zandbedden of hoofdkussens worden gebruikt (dit is naar eigen invulling van de afdeling). Hierover kan de werkgroep geen aanbevelingen doen, behalve dat een zandbed voordelen heeft bij patiënten met ernstige decubitus om verdere schade te voorkomen, maar ook bij patiënten met ernstige obesitas waarbij een zandbed een verlaging van de intra-abdominale/thoracale druk kan geven.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep is van mening dat zorgmedewerkers die buikligging uitvoeren getraind moeten zijn in deze procedure en kennis moeten hebben van bekende complicaties zodat voorzorgsmaatregelen worden genomen om complicaties te voorkomen. Hierbij kan gedacht worden aan maatregelen vooraf aan het draaien, zoals het verwijderen van ECG-plakkers op de kant waar de patiënt op komt te liggen, maatregelen tijdens het draaien zoals fixatie van de endotracheale tube en centraal veneuze katheters, correcte houding van armen ter preventie van schouderluxatie en maatregelen na het draaien zoals het vrij leggen van de tube en de maagsonde, en regelmatige wisselligging ter preventie van decubitus. Daarnaast dient bij de implementatie ook gekeken te worden naar het arbeidstechnische aspect en haalbaarheid voor het draaiteam (m.n. bij ernstige obesitas).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de overwegingen en resultaten uit de literatuur (positief effect van buikligging op overleving indien buikligging >16 uur wordt toegepast en er vroeg gestart wordt bij ernstige ARDS (<48 uur na optreden PaO2/FiO2 ratio <150 mmHg), zonder ernstige complicaties) heeft de werkgroep besloten tot het formuleren van de volgende aanbevelingen. In deze besluitvorming is meegenomen dat buikligging een eenvoudige, goedkope en relatief veilige interventie is die de risico’s op (het verergeren van) ventilator-induced lung injury kan verminderen en daarmee de uitkomst (mortaliteit) kan verbeteren bij ernstige ARDS.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Kunstmatige beademing in buikligging wordt al vele jaren toegepast bij patiënten met ARDS. De fysiologische mechanismen waardoor patiënten baat kunnen hebben bij buikligging zijn een verbeterde ventilatie-perfusie match, een vergroting van het eind-expiratoire longvolume met daarbij een meer homogene distributie van teugvolumina door long recruitment en veranderingen in thoraxwand mechanica. De LUNG SAFE studie (Bellani, 2016) en de APRONET-studie (Guérin, 2018) hebben laten zien dat in het pre-COVID tijdperk buikligging slechts in beperkte mate werd toegepast bij ernstige ARDS. De APRONET-studie laat tevens zien dat de belangrijkste reden hiervoor is dat in de praktijk buikligging vaak nog als rescue-therapie wordt gezien en de ernst van de hypoxemie vaak niet ernstig genoeg wordt geacht voor het toepassen hiervan. Dit suggereert dat de identificatie van patiënten met ernstig ARDS door middel van de PaO2/FiO2 ratio weinig wordt gebruikt voor het starten van buikligging of dat er onvoldoende awareness is dat buikligging het risico op (of het verergeren van) ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) vermindert (Guerin, 2018). Het beoordelen van het nut van buikligging met het oog op herhaling van toepassing van buikligging wordt verschillend gedaan. In de PROSEVA trial werd vooraf aan een nieuwe sessie de indicatie beoordeeld op basis van de P/F-ratio in rugligging conform de situatie vooraf aan de eerste poging (Guerin 2013). De APRONET studie laat zien dat ook andere argumenten gebruikt worden zoals verbetering van oxygenatie in buikligging ten opzichte van rugligging (Guerin 2018). Ook de duur van buikligging is variabel tussen verschillende centra.

Deze module geeft een samenvatting van het bewijs van de mogelijke klinische voordelen van beademing in buikligging, en wanneer en hoe lang buikligging wordt aanbevolen. Deze module focust zich op matig-ernstige ARDS-patiënten die gecontroleerd beademd worden.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of mechanical ventilation in the prone position that started within 48 hours for <16 hours per day, after meeting entry criteria/ventilation on short term mortality compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with all (mild, moderate and severe) ARDS.

Sources: - |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical ventilation in the prone position that started within 48 hours for < 16 hours per day, after meeting entry criteria/ventilation on long term mortality compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with all (mild, moderate and severe) ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical ventilation in the prone position that started after 48 hours for <16 hours per day, after meeting entry criteria/ventilation on short- and long-term mortality compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with all (mild, moderate and severe) ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Mechanical ventilation in the prone position that started within 48 hours for >16 hours per day, after meeting entry criteria/ventilation probably results in a reduction in short- and long-term mortality compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with moderate-severe ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical ventilation in the prone position that started after 48 hours for >16 hours per day, after meeting entry criteria/ventilation on short- and long-term mortality compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with moderate-severe ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015 |

|

Low GRADE |

Mechanical ventilation in the prone position may result in an increase in PaO2/FiO2 ratio reported at 7 to 10 days compared to mechanical ventilation in supine position in patients with ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015 |

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of mechanical ventilation in the prone position on Quality of Life compared to mechanical ventilation in supine position in patients with ARDS.

Sources: - |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical ventilation in the prone position on unplanned catheter removal compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with ARDS.

Sources: Munshi, 2017 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Mechanical ventilation in the prone position probably results in little to no difference in unplanned extubation compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015; Munshi 2017 |

|

Low GRADE |

Mechanical ventilation in the prone position may result in higher risk of endotracheal tube obstruction compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mechanical ventilation in the prone position on ventilator-associated pneumonia compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015; Munshi, 2017 |

|

Low GRADE |

Mechanical ventilation in the prone position may result in more pressure sores compared to mechanical ventilation in the supine position in patients with ARDS.

Sources: Bloomfield, 2015; Girard, 2014 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Bloomfield (2015) conducted a Cochrane systematic literature review and meta-analysis regarding the effect of mechanical ventilation in the prone positioning compared with mechanical ventilation in the supine position for adult patients with acute respiratory failure, but most included studies focused on adult patients with ARDS. The search of Bloomfield (2015) was updated in 2014 using CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and LILACS in Ovid MEDLINE for eligible randomized controlled trials. In total 9 RCTs and a study reporting follow-up subgroup analyses of one of the RCTs were included. For the current review we excluded one RCT (Leal, 1997) as the intervention period was less than two days and the study was published prior to 2000 (being two of our exclusion criteria) and we excluded the subgroup analysis (Chiumello, 2012). Table 1 shows an overview of the RCTs that were included in the current review.

Note that Bloomfield (2015) mentioned three studies reporting (additional) results of RCTs who were waiting for classification. Two of these studies could not be included in the current literature review (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), but data of Girard (2014), reporting a secondary outcome measure (pressure sores) of Guerins (2013) RCT, will be included in the current literature review.

Munshi (2017) conducted a systematic literature review with the same papers as included in Bloomfield (2015). In the current review, Munshi (2017) was only used for the outcome measure unplanned catheter removal as this measure was not reported by Bloomfield (2015).

Table 1. Study characteristics of included studies

|

Author, year |

N P=prone S=supine |

Criteria for enrollment* |

Mean or median duration of prone position |

Lung-protective ventilation mandated (low tidal volume)# |

Quit early¶ |

|

Gattinoni, 2001 |

P: n=152 S: n=152 |

Mild, moderate, severe ARDS |

7 hrs daily for 4.7 days |

no |

Yes |

|

Guerin 2004 |

P: n=413 S: n=378 |

ARF (mild, moderate, severe ARDS in 791/802 patients) |

8 hrs daily for 4 days‡ |

no |

No |

|

Voggenreiter 2005 |

P: n=21 S: n=19 |

Mild ARDS for >24 hrs or moderate-severe ARDS for >8 hrs |

11 hrs daily for 7 days |

yes |

Yes |

|

Mancebo 2006 |

P: n=76 S: n=60 |

Moderate-severe ARDS, four quadrant infiltrates on chest X-ray |

17 hrs daily for 10 days |

no |

Yes |

|

Chan 2007 |

P: n=11 S: n=11 |

Moderate-severe ARDS due to CAP |

24 hrs daily for 4.4 days |

yes |

Yes |

|

Fernandez 2008 |

P: n=21 S: n=19 |

Moderate-severe ARDS |

18 hrs daily for NR number of days |

yes |

Yes |

|

Taccone 2009 |

P: n=168 S: n=174 |

Moderate-severe ARDS |

18 hrs daily for 8 days |

yes |

No |

|

Guerin 2013

|

P: n=237 S: n=229 |

Moderate-severe ARDS with PaO2/FiO2 < 150 mmHg and FiO2 >60% after 12–24 hrs of optimal management |

17 hrs daily for 4 days |

yes |

No |

‡median; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF = acute respiratory failure; CAP = community-acquired pneumonia; NR=Not Reported

*ARDS severity according to Berlin definition: PaO2/FiO2 200–300 mmHg as mild, PaO2/FiO2 100–200 mmHg as moderate, and PaO2/FiO2 <100 mmHg as severe ARDS.

# Lung-protective ventilation <8 ml/kg predicted body weight.

¶ All “yes” results were due to slow enrollment.

Results

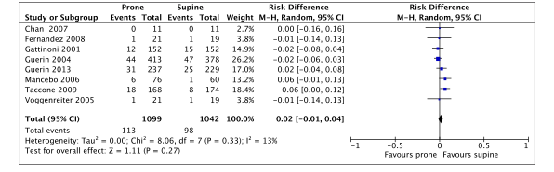

Mortality, short term (10-30 days or ICU-mortality)

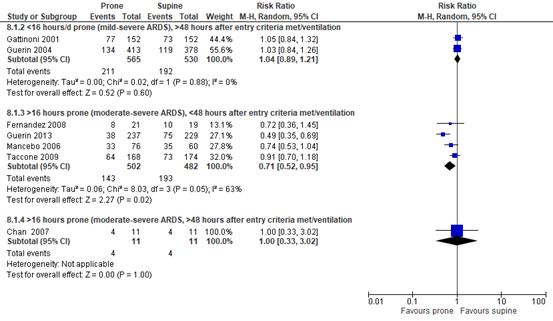

Seven of the included RCTs (Chan, 2007; Fernandez, 2008; Gattinoni, 2001; Guerin, 2004; Guerin, 2013; Mancebo, 2006; Taccone, 2009) in Bloomfield (2015) that were selected for the current review reported short term mortality. Because of heterogeneity within studies, results in the current review are reported for subgroups (duration of proning, disease severity and hours after meeting entry criteria or starting ventilation, see figure 1).

Mild-severe ARDS, <16 hours proning, starting after 48 hours:

211 out of 565 (37.3%) proned patients died compared to 192 out of 530 (36.2%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 1.04; 95%CI 0.89 to 1.21). This difference was not clinically relevant.

Moderate-severe ARDS, >16 hours proning, starting within 48 hours:

143 out of 502 (28.5%) proned patients died compared to 193 out of 482 (40.0%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 0.71; 95%CI 0.52 to 0.95). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of proned patients.

Moderate-severe ARDS, >16 hours proning, starting after 48 hours:

4 out of 11 (36.4%) proned patients died compared to 4 out of 11 (36.4%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 1.00; 95%CI 0.33 to 3.02). This difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Forest plot: Short-term mortality#

# Short-term mortality: 10-30-day mortality or IC mortality.

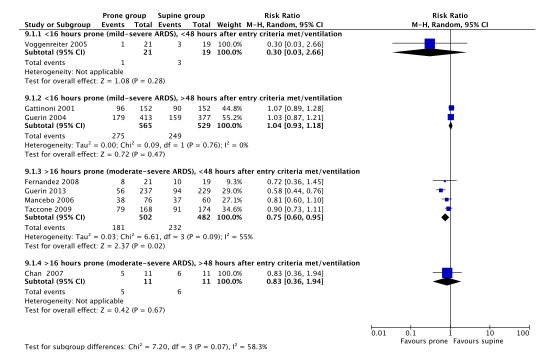

Mortality, long term (>30 days)

Eight of the included RCTs (Chan, 2007; Fernandez, 2008; Gattinoni, 2001; Guerin, 2004; Guerin, 2013; Mancebo, 2006; Taccone, 2009; Voggenreiter, 2005) in Bloomfield (2015) that were selected for the current review reported long term mortality. Because of heterogeneity within studies, results in the current review are reported for subgroups (duration of proning, disease severity and hours after meeting entry criteria or starting ventilation, see figure 2).

Mild-severe ARDS, <16 hours proning, starting within 48 hours:

1 out of 21 (4.8%) proned patients died compared to 3 out of 19 (15.8%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 0.30; 95%CI 0.03 to 2.66). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of proned patients.

Mild-severe ARDS, <16 hours proning, starting after 48 hours:

275 out of 565 (48.7%) proned patients died compared to 249 out of 529 (47.1%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 1.04; 95%CI 0.93 to 1.18). This difference was not clinically relevant.

Moderate-severe ARDS, >16 hours proning, starting within 48 hours:

181 out of 502 (36.1%) proned patients died compared to 232 out of 482 (48.3%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 0.75; 95%CI 0.60 to 0.95). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of proned patients.

Moderate-severe ARDS, >16 hours proning, starting after 48 hours:

5 out of 11 (45.5%) proned patients died compared to 6 out of 11 (54.5%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 0.83; 95%CI 0.36 to 1.94). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of proned patients.

Figure 2. Forest plot: Long-term mortality#

# Long-term mortality: >30-day mortality or in-hospital mortality

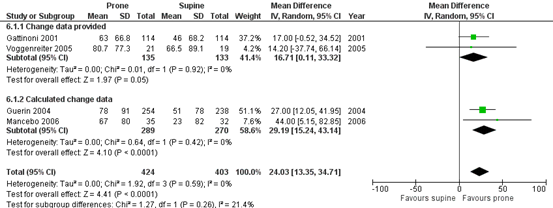

PaO2/FiO2 ratio at day 7 to 10

Four of the included RCTs (Guerin, 2004; Guerin, 2013; Mancebo, 2006) reported the PaO2/FiO2 ratio at day 7 or 10. Note that Taccone (2009) also reported this quotient, but baseline PaO2/FiO2 ratio was measured when the patient was already in prone position. Therefore, this study was not included in this analysis. Two of the included RCTs (Gattinoni, 2001; Voggenreiter, 2005) in Bloomfield (2015) that were selected for the current review reported the change in PaO2/FiO2 ratio. 1169 patients (prone, n=592; supine, n=577) were included in the meta-analysis of change data (figure 3). Change data from Guerin (2004) and Mancebo (2006) was calculated as the difference between first day/baseline data and day 7 or 10 data. For variance, the standard deviation at day 7 or 10 was used. Bloomfield (2015) mentioned that inflating the entered standard deviations with approximately 50% had no impact on interferences. Guerin (2013) was not included in the meta-analysis as formally mandated reduction in PEEP during proning would negatively impact oxygenation and would confound the results.

The PaO2/FiO2 ratio was more increased (MD 24.03; 95%CI 13.35 to 34.71) in patients with ARDS who were mechanically ventilated in prone position compared to patients with ARDS who were mechanically ventilated in supine position. This difference was clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Forest plot: Mean increase in PaO2/FIO2 ratio (mmHg) at 7 or 10 days

Quality of Life

No studies reporting quality of life were included in the summary of literature.

Adverse Events

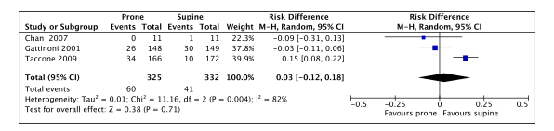

Unplanned central catheter removal

Three of the included RCTs (Chan, 2007; Gattinoni, 2001; Taccone, 2009) in Munshi (2017) that were selected for the current review reported unplanned central catheter removal. 657 patients were included in the meta-analysis (figure 4).

60 out of 325 (18.5%) proned patients had unplanned central catheter removal compared to 41 out of 332 (12.3%) patients who were treated in supine position (RD 0.03; 95%CI -0.12 to 0.18). This difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Forest plot: Unplanned central catheter removal

Unplanned extubation

Eight of the included RCTs (Chan, 2007; Fernandez, 2008, Gattinoni, 2001; Guerin, 2004; Guerin, 2013; Mancebo, 2006; Taccone, 2009; Voggenreiter, 2005) in Bloomfield (2015) and Munshi (2017) that were selected for the current review reported unplanned endotracheal tube extubation. 2141 patients were included in the meta-analysis (figure 5).

113 out of 1099 (10.3%) proned patients had unplanned endotracheal tube extubation compared to 98 out of 1042 (9.4%) patients who were treated in supine position (RD 0.02; 95%CI -0.01 to 0.04). This difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 5. Forest plot: Unplanned extubation

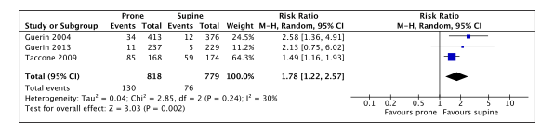

Endotracheal tube obstruction

Three of the included RCTs (Guerin, 2004; Guerin, 2013; Taccone, 2009) in Bloomfield (2015) that were selected for the current review reported endotracheal tube obstruction. 1597 patients were included in the meta-analysis (figure 6).

130 out of 818 (15.9%) proned patients had endotracheal tube obstruction compared to 76 out of 779 (9.8%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 1.78; 95%CI 1.22 to 2.57). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of the supine group.

Figure 6. Forest plot: Endotracheal tube obstruction

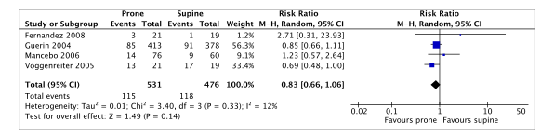

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

Four of the included RCTs (Fernandez, 2008, Guerin, 2004; Mancebo, 2006; Voggenreiter, 2005) in Bloomfield (2015) and Munshi (2017) that were selected for the current review reported ventilator-associated pneumonia. 1007 patients were included in the meta-analysis (figure 7).

115 out of 531 (21.7%) proned patients had ventilator-associated pneumonia compared to 118 out of 476 (24.8%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 0.83; 95%CI 0.66 to 1.06). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of the prone group.

Figure 7. Forest plot: Ventilator-associated pneumonia

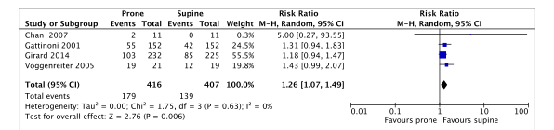

Pressure sores

Three of the included RCTs (Chan, 2007; Gattinoni, 2001; Voggenreiter, 2005) in Bloomfield (2015) that were selected for the current review and Girard (2014) reported pressure sores. Guerin (2004) was not included as this study reported events per day instead of the number of patients with pressure sores. 823 patients were included in the meta-analysis (figure 8).

179 out of 416 (43.0%) proned patients had pressure sores compared to 139 out of 407 (34.1%) patients who were treated in supine position (RR 1.26; 95%CI 1.07 to 1.49). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of the supine group.

Figure 8. Forest plot: Pressure sores

Level of evidence of the literature

The majority of studies were terminated early due to slow enrollment. We decided not to lower the level of evidence because of slow enrollment on itself, since this is not a reason for probable bias.

Mortality (short term)

For the subgroup “mild-severe ARDS, <16 hours proning, starting after 48 hours”, the level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to very low level because of risk of bias (one level, many patients crossed over from intervention groups) and imprecision (two levels, 95% CI crossing both borders of clinical relevance).

For the subgroup “moderate-severe ARDS, >16 hours proning, starting within 48 hours”, the level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to a moderate level because of imprecision (one level, 95% CI crossing border of clinical relevance).

For the subgroup “moderate-severe ARDS, >16 hours proning, starting after 48 hours”, the level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to a very low level because of risk of bias (one level, allocation bias) and imprecision (two levels, 95% CI crossing both borders of clinical relevance).

Mortality (long term)

For the subgroup “mild-severe ARDS, <16 hours proning, starting within 48 hours”, the level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to very low level because of risk of bias (one level, differential use of co-intervention) and imprecision (two levels, 95% CI crossing both borders of clinical relevance).

For the subgroup “mild-severe ARDS, <16 hours proning, starting after 48 hours”, the level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to very low level because of risk of bias (one level, many patients crossed over from intervention groups) and imprecision (two levels, 95% CI crossing both borders of clinical relevance).

For the subgroup “moderate-severe ARDS, >16 hours proning, starting within 48 hours”, the level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to moderate level because of imprecision (one levels, 95% CI crossing border of clinical relevance).

For the subgroup “moderate-severe ARDS, >16 hours proning, starting after 48 hours”, the level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to very low level because of risk of bias (one level, allocation bias) and imprecision (two levels, 95% CI crossing both borders of clinical relevance).

PaO2/FiO2 ratio or quotient at day 7 to 10

The level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to low level because of risk of bias (one level, see risk of bias table) and inconsistency (one level, clinical heterogeneity between patients).

Quality of Life

As Chiumello (2012) did not meet inclusion criteria of the current review, results were not graded.

Adverse events

Unplanned central catheter removal

The level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to very low level because of risk of bias (one level, see risk of bias table), inconsistency (one level, clinical heterogeneity between patients) and imprecision (one level, low number of events).

Unplanned extubation

The level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to moderate level because of risk of bias (one level, see risk of bias table).

Endotracheal tube obstruction

The level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to low level because of risk of bias (one level, see risk of bias table) and imprecision (low number of events).

(Ventilator-associated) pneumonia

The level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to very low level because of risk of bias (one level, see risk of bias table), inconsistency (one level) and imprecision (low number of events).

Pressure sores

The level of evidence started at high and was downgraded to low level because of risk of bias (one level, see risk of bias table) and imprecision (one level, crossing the border of clinical relevance).

Zoeken en selecteren

Search and select

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effectivity of mechanical ventilation in the prone position in comparison to mechanical ventilation in supine position on mortality, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, Quality of Life (QoL) and adverse events in patients with ARDS?

P: Adult patients with ARDS receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at the ICU

I: Mechanical ventilation in the prone position

C: Mechanical ventilation in the supine position

O: Mortality, PaO2/FIO2 ratio on day 7 to 10, QoL, adverse events (unplanned central catheter removal, unplanned extubation, endotracheal tube obstruction, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and pressure sores)

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and PaO2/FiO2 ratio, QoL and adverse events as important outcome measures for clinical decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

Short-term mortality: 10-30-day mortality or IC mortality (according to Bloomfield 2015)

Long-term mortality: 31-180-day mortality or in-hospital mortality (according to Bloomfield 2015)

PaO2/FiO2 ratio on day 7 to 10: according to definitions used in the studies

QoL: according to definitions used in the studies.

Adverse events: according to definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following values as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

Mortality: 0.95≥RR≥1.05 -0.05≥RD≥0.05

PaO2/FiO2 ratio: MD≥10%

QoL: MD≥10% of maximum score from a validated questionnaire

Adverse events: 0.91≥RR≥1.10, or if RR is not available: -0.10≥RD≥0.10

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 17-11-2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 360 articles. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review or RCT

- Published ≥ 2000

- Mechanically ventilated patients with ARDS admitted to the ICU

- Comparison between prone and supine position

- Intervention period for more than two days

- Outcome measures as described in PICO

23 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 21 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included.

Results

One systematic review (Bloomfield, 2015) was included in the analysis of the literature. A second systematic review (Munshi, 2017) was included for one outcome measure.

Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Albert RK, Keniston A, Baboi L, Ayzac L, Guérin C; Proseva Investigators. Prone position-induced improvement in gas exchange does not predict improved survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 Feb 15;189(4):494-6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-2056LE. PMID: 24528322.

- Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld G, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):788-800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. Erratum in: JAMA. 2016 Jul 19;316(3):350. Erratum in: JAMA. 2016 Jul 19;316(3):350. PMID: 26903337.

- Bloomfield, R., Noble, D. W., & Sudlow, A. (2015). Prone position for acute respiratory failure in adults. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (11).

- Chan, M. C., Hsu, J. Y., Liu, H. H., Lee, Y. L., Pong, S. C., Chang, L. Y., ... & Wu, C. L. (2007). Effects of prone position on inflammatory markers in patients with ARDS due to community-acquired pneumonia. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 106(9), 708-716.

- Chiumello, D., Taccone, P., Berto, V., Marino, A., Migliara, G., Lazzerini, M., & Gattinoni, L. (2012). Long-term outcomes in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated in supine or prone position. Intensive Care medicine, 38(2), 221-229.

- Fernandez, R., Trenchs, X., Klamburg, J., Castedo, J., Serrano, J. M., Besso, G., ... & Lopez, M. J. (2008). Prone positioning in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care medicine, 34(8), 1487-1491.

- Gattinoni, L., Tognoni, G., Pesenti, A., Taccone, P., Mascheroni, D., Labarta, V., ... & Latini, R. (2001). Effect of prone positioning on the survival of patients with acute respiratory failure. New England Journal of Medicine, 345(8), 568-573.

- Guérin C, Beuret P, Constantin JM, Bellani G, Garcia-Olivares P, Roca O, Meertens JH, Maia PA, Becher T, Peterson J, Larsson A, Gurjar M, Hajjej Z, Kovari F, Assiri AH, Mainas E, Hasan MS, Morocho-Tutillo DR, Baboi L, Chrétien JM, François G, Ayzac L, Chen L, Brochard L, Mercat A; investigators of the APRONET Study Group, the REVA Network, the Réseau recherche de la Société Française d'Anesthésie-Réanimation (SFAR-recherche) and the ESICM Trials Group. A prospective international observational prevalence study on prone positioning of ARDS patients: the APRONET (ARDS Prone Position Network) study. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Jan;44(1):22-37. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4996-5. Epub 2017 Dec 7. PMID: 29218379.

- Guérin, C., Gaillard, S., Lemasson, S., Ayzac, L., Girard, R., Beuret, P., ... & Kaidomar, M. (2004). Effects of systematic prone positioning in hypoxemic acute respiratory failure: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 292(19), 2379-2387.

- Guérin, C., Reignier, J., Richard, J. C., Beuret, P., Gacouin, A., Boulain, T., ... & Ayzac, L. (2013). Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(23), 2159-2168.

- Guérin, C., Albert, R.K., Beitler, J., Gattinoni, L., Jaber, S., Marini, J.J., . & Mancebo J. (2020). Prone position in ARDS patients: why, when, how and for whom. Intensive Care Med, 46(12), 2385-2396.

- Leal, R. P., Gonzalez, R., Gaona, C., Garcia, G., Maldanado, A., & Dominguez-Cherit, G. (1997). Randomized trial compare prone vs supine position in patients with ARDS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 155, A745.

- Mancebo, J., Fernández, R., Blanch, L., Rialp, G., Gordo, F., Ferrer, M., ... & Albert, R. K. (2006). A multicenter trial of prolonged prone ventilation in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 173(11), 1233-1239.

- Munshi, L., Del Sorbo, L., Adhikari, N. K., Hodgson, C. L., Wunsch, H., Meade, M. O., ... & Fan, E. (2017). Prone position for acute respiratory distress syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 14(Supplement 4), S280-S288.

- Taccone, P., Pesenti, A., Latini, R., Polli, F., Vagginelli, F., Mietto, C., ... & Prone-Supine II Study Group. (2009). Prone positioning in patients with moderate and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 302(18), 1977- 1984.

- Voggenreiter, G., Aufmkolk, M., Stiletto, R. J., Baacke, M. G., Waydhas, C., Ose, C., ... & Nast- Kolb, D. (2005). Prone positioning improves oxygenation in post-traumatic lung injury-a prospective randomized trial. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 59(2), 333-343.

- Walter T, Ricard JD. Extended prone positioning for intubated ARDS: a review. Crit Care. 2023 Jul 5;27(1):264. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04526-2. PMID: 37408074; PMCID: PMC10320968.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Bloomfield, 2015

*1 Munshi (2017)

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to August 2016

A: Gattinoni, 2001 B: Guerin 2004 C: Voggenreiter 2005 D: Mancebo 2006 E: Chan 2007 F: Fernandez 2008 G: Taccone 2009 H: Guerin 2013 *Leal 1997 and chiumelli not included in the current literature review

Study design: A: RCT [cross-over] B: RCT [cross-over] in case of severe hypoxemia C: RCT [parallel] D: RCT [cross-over] E: RCT [parallel] F: RCT [cross-over] in case of severe or life-threatening hypoxemia G: RCT [parallel] H: RCT [cross-over] in case of severe or life-threatening hypoxemia I: post-hoc analysis from RCT ‘G’

Setting: all IC Country: A: NR B: NR C: NR D: NR E: NR F: NR G: NR H: France and Spain

Source of funding: No conflicts of interests reported |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs that compared mechanical ventilation in the prone position to ventilation in the supine position in adults with ARDS any trials that enrolled patients who, in hindsight, met the more recently defined Berlin criteria for ARDS were included

Exclusion criteria SR: Prone position <2 days

8 studies included (n=2,129)

N A: 304 B: 802 C: 40 D: 142 E: 22 F: 42 G: 344 H: 466

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Age and sex not reported in SR

Criteria for enrollment* A: Mild, moderate, severe ARDS B: ARF (mild, moderate, severe ARDS in 791 patients) C: Mild ARDS for >24 h or moderate to severe ARDS for >8 h on PEEP > 5 cm H2O D: Moderate to severe ARDS, four quadrant infiltrates on chest X-ray E: Moderate to severe ARDS due to CAP F: Moderate to severe ARDS G: Moderate to severe ARDS on PEEP > 5 cmH2O H: Moderate to severe ARDS with PaO2/FiO2 , 150 mmHg, PEEP > 5 cm H2O and FIO2 > 60% after 12–24 h optimal management

PaO2/FiO2 ratio, mean A: I=125; C=130 B: I=150; C=155 C: I=215; C=228 D: I=132; C=161 E: I=111; C=118 F: I=114; C=122 G: I=113; C=113 H: I=100; C=100

Lung-protective ventilation A: no B: no C: yes D: no E: yes F: yes G: yes H: yes

Weaning protocol: A: no B: yes C: no D: yes E: no F: yes G: no H: yes

Studies A,C,D,E,F were stopped early due to slow enrollment.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes (unclear for age and sex and other non-medical characteristics) |

Describe intervention: mechanical ventilation in the prone position

Hours prone/day, mean or median‡ A: 7.0 B: 8.0‡ C: 11.0 D: 17.0 E: 24.0 F: 18.0 G: 18.0 H: 17.0

No. of days prone, mean or median‡ A: 4.7 B: 4.0‡ C: 7.0 D: 10.0 E: 4.4 F: NR G: 8.0 H: 4.0

|

Describe control: mechanical ventilation in the supine position

|

End-point of follow-up: Mortality was determined at hospital discharge or a minimum of 90 days, if not available, the longest duration of follow-up

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (only available for mortality) (intervention/control) A: n=0 B: mortality unknown for 7/385 in supine group, 4/417 in prone group C: n=0 D: mortality unknown for 2/62 in supine group, 4/80 in prone group E: n=0 F: mortality unknown for 1/20 in supine group, 1/22 in prone group G: mortality unknown for 1/175 in supine group, 1/169 in prone group H: n=0

|

Outcome measure-1 Effect measure: RR [95% CI]:

Short term mortality A: 1.05 (0.84 to 1.32) B: 1.03 (0.84 to 1.26) D: 0.74 (0.53 to 1.04) E: 1.00 (0.33 to 3.02) F: 0.72 (0.36 to 1.45) G: 0.91 (0.70 to 1.18) H: 0.49 (0.35 to 0.69)

Pooled effect (random effects model) of early mortality: RR 0.84 [95% CI 0.69 to 1.02] favoring prone positioning Heterogeneity (I2): 53%

Long term mortality A: 1.07 (0.89 to 1.28) B: 1.03 (0.87 to 1.21) C: 0.3 (0.03 to 2.66) D: 0.81 (0.6 to 1.1) E: 0.83 (0.36 to 1.94) F: 0.72 (0.36 to 1.45) G: 0.9 (0.73 to 1.11) H: 0.58 (0.44 to 0.76)

Pooled effect (random effects model) of early mortality: RR 0.86 [95% CI 0.72 to 1.03] favoring prone positioning Heterogeneity (I2): 61.21%

Reported by *1 Defined as 28/30 day mortality unless stated otherwise A: 1.04 (0.82 to 1.34) B: 1.03 (0.84 to 1.26) B^: 1.03 (0.87 to 1.21)^ C: 0.30 (0.03 to 2.66)^ D: 0.81 (0.60 to 1.10)$ E: 1.00 (0.33 to 3.02) F: 0.72 (0.36 to 1.45)# G: 0.94 (0.69 to 1.29) H: 0.49 (0.35 to 0.69) H^: 0.58 (0.44 to 0.76)^

# 60 day mortality $ in-hospital mortality ^ 90 day mortality

Pooled effect (random effects model) of early mortality: RR 0.84 [95% CI 0.68 to 1.04] favoring prone positioning Heterogeneity (I2): 59%

Outcome measure-2 Defined as PaO2/FiO2 ratio change on Day 7-10 Effect measure: MD [95% CI]:

A: 17.00 (-0.52 to 34.52) B: 27.00 (12.05 to 41.95) C: 14.2 (--37.74 to 66.14) D: 44.00 (5.15 to 82.85)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 24.03 [95% CI 13.35 to 34.71 ] favoring prone position Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Calculated from G: Prone: 44 (91)

Outcome measure-3 (Adverse Events)

3.1 Defined as unplanned central venous catheter removal *1

Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: A: 0.87 (0.54 to 1.40) E: 0.33 (0.02 to 7.39) G: 3.52 (1.80 to 6.90)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.41 [95% CI 0.41 to 4.86 ] favoring supine position Heterogeneity (I2): 83%

3.2 Defined as unplanned extubation Effect measure: RR [95% CI]:

Reported as tracheal tube displacement) A: 0.80 (0.39 to 1.65) B: 0.86 (0.58 to 1.26) C: 0.90 (0.06 to 13.48) E: N/A F:0.90 (0.06 to 13.48) G: 2.33 (1.04 to 5.21) H: 1.19 (0.76 to 1.86)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.09 [95% CI 0.85 to 1.39 ] favoring supine position Heterogeneity (I2): 19.78%

Reported by *1 A: 0.81 (0.39 to 1.66) B: 0.97 (0.67 to 1.41) C: 0.90 (0.06 to 13.48) D: 4.74 (0.59 to 38.29) E: 0.33 (0.02 to 7.39) F:0.90 (0.06 to 13.48) G: 2.33 (1.04 to 5.21) H: 1.20 (0.73 to 1.96)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.12 [95% CI 0.86 to 1.45 ] favoring supine position Heterogeneity (I2): 2%

3.3 Defined as Endotracheal tube obstruction Effect measure: RR [95% CI]:

B: 2.58 (1.36 to 4.91) G: 1.49 (1.16 to 1.93) H: 2.13 (0.75 to 6.02)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.72 [95% CI 1.35 to 2.18 ] favoring supine position Heterogeneity (I2): 29.86%

Reported by *1 B: 2.59 (1.36 to 4.92) G: 1.49 (1.16 to 1.93) H: 2.13 (0.75 to 6.02)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.76 [95% CI 1.24 to 2.50 ] favoring supine position Heterogeneity (I2): 26%

3.4 Defined as ventilator associated pneumonia Effect measure: RR [95% CI]:

B: 0.85 (0.66 to 1.11) C: 0.70 (0.40 to 1.20) D: 1.23 (0.57 to 2.64) F:2.71 (0.31 to 23.93)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.88 [95% CI 0.71 to 1.11 ] favoring prone position Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Reported by *1 B: 0.85 (0.66 to 1.11) C: 0.69 (0.48 to 1.00) D: 1.23 (0.57 to 2.64) F:2.71 (0.31 to 23.93)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.83 [95% CI 0.66 to 1.06 ] favoring prone position Heterogeneity (I2): 12%

3.5 Defined as pressure sores Effect measure: RR [95% CI]:

Reported by *2 A: 1.31 (0.94 to 1.83) C: 1.43 (0.99 to 2.07) E: 5.00 (0.27 to 93.55)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.37 [95% CI 1.05 to 1.79 ] favoring supine position Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Reported by *1 A: 1.29 (0.84 to 2.01) B: 1.21 (1.06 to 1.41) E: 5.00 (0.27 to 93.55)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.22 [95% CI 1.06 to 1.41 ] favoring supine position Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Reported by *2 Day 7: Prone: 116/204

ICU discharge:

3.6 Quality of Life Not reported by studies included in the current review. |

Brief description of author’s conclusion: We found no convincing evidence of benefit nor harm from universal application of PP in adults with hypoxaemia mechanically ventilated in Intensive Care units (ICUs). Three subgroups (early implementation of PP, prolonged adoption of PP and severe hypoxaemia at study entry) suggested that prone positioning may confer a statistically significant mortality advantage. Additional adequately powered studies would be required to confirm or refute these possibilities of subgroup benefit but are unlikely, given results of the most recent study and recommendations derived from several published subgroup analyses. Meta-analysis of individual patient data could be useful for further data exploration in this regard. Complications such as tracheal obstruction are increased with use of prone ventilation. Long-term mortality data (12 months and beyond), as well as functional, neuro-psychological and quality of life data, are required if future studies are to better inform the role of PP in the management of hypoxaemic respiratory failure in the ICU.

Sensitivity analyses were performed for lung protective ventilation, duration of prone position and severity of ARDS.

|

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF = acute respiratory failure; RCT=Randomized Controlled Trial; CAP = community-acquired pneumonia; NR=Not Reported; PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure

**ARDS according to Berlin definition, ARDS PaO2/FI O2 , 300 mmHg; mild, 200–300 mmHg; moderate to severe, ,200 mmHg

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Bloomfield, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes* |

Yes

Where appropriate pre-planned subgroup analyses were performed |

Yes, visual inspection of the funnel plot did not suggest major publication bias |

No

|

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Chiumello, 2012 |

Study in SR of Bloomfield, but excuded because subgroup analyses of Taccone, 2009 were performed |

|

Gainnier, 2003 |

Does not answer PICO |

|

Gattinoni, 2001 |

Study in SR of Bloomfield and this literature analyses |

|

Voggenreiter, 2005 |

Study in SR of Bloomfield and this literature analyses |

|

Mancebo, 2006 |

Study in SR of Bloomfield and this literature analyses |

|

Chan, 2007 |

Study in SR of Bloomfield and this literature analyses |

|

Fernandez, 2008 |

Study in SR of Bloomfield and this literature analyses |

|

Taccone, 2009 |

Study in SR of Bloomfield and this literature analyses |

|

Guerin, 2013 |

Study in SR of Bloomfield and this literature analyses |

|

Sud, 2014 |

More recent SR available; Curley (pediatric), Beuret (majority not ALI/ARDS only 7/326), Watanabe (no mortality data and quasi RCT) were excluded from this SR |

|

Lee, 2014 |

More recent SR available; all refs are included in literature analysis; except Papazian and Demory (<2 days prone positioning), Beuret (majority not ALI/ARDS only 7/326) were excluded |

|

Aoyama, 2019 |

Does not answer PICO: compares multiple strategies (no new studies compared to Munshi) |

|

Sud, 2008 |

More recent SR available; all refs are included in literature analysis; except Leal, Papazian, Demory (short-term <2 days prone positioning), Curley (pediatric), Beuret (majority not ALI/ARDS only 7/326), Watanabe (no mortality data and quasi RCT) were excluded from this SR |

|

Alsaghir, 2008 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis; Papazian (<2 days prone positioning) was excluded |

|

Abroug, 2008 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis except Curley (pediatric) |

|

Tiruvoipati, 2008 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis, except Watanabe (no mortality data and quasi RCT) |

|

Kopterides, 2009 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis |

|

Mounier, 2010 |

Wrong study design: prospective observational study |

|

Abroug, 2011 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis |

|

Hu, 2014 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis except Curley (pediatric) |

|

Beitler, 2014 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis |

|

Park, 2015 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis |

|

Mora-Arteaga, 2015 |

More recent SR available, all refs are included in literature analysis |

|

Dalmedico, 2017 |

Review of reviews, not enough information available |

|

Abroug, 2009 |

More recent SR available |

|

Bloomfield, 2009 |

More recent SR available (update form Cochrane) |

|

Del Sorbo, 2017 |

Clinical guideline |

|

Fan, 2017 |

Clinical guideline |

|

Fan, 2018 |

Clinical guideline |

|

Gattinoni, 2010 |

More recent SR available |

|

Mebazaa, 2007 |

French language, more recent SR available |

|

Qureshi, 2012 |

More recent SR available |

|

Tonelli, 2014 |

More recent SR available, umbrella review, not only on proning |

|

Yue, 2017 |

Chinese language |

|

Chan, 2007 |

No RCT, wrong outcome measures |

|

Fessler, 2010 |

Narrative review |

|

Jochmans, 2020 |

No RCT |

|

Offner, 2000 |

No RCT |

|

Robak, 2011 |

Does not answer PICO: combining upright and prone position and wrong outcome measures |

|

Studies waiting for classification in Bloomfield (2015) |

Ayzac, 2014: abstract Zhou, 2014: Chinese language |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 05-03-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financierder heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met ARDS.

Werkgroep

- Dr. H. Endeman, internist-intensivist, NVIC

- Dr. R.M. Determann, internist-intensivist, NIV

- Drs. R. Pauw, longarts-intensivist, NVALT

- Drs. M. Samuels, anesthesioloog-intensivist, NVA

- Dr. A.H. Jonkman, klinisch technoloog, NVvTG

- J.W.M. Snoep, ventilation practitioner/IC-verpleegkundige, V&VN

- Drs. M.A.E.A. Brackel, patiëntvertegenwoordiger (tot 1-1-2022 bestuurslid FCIC/Voorzitter IC Connect), FCIC/IC Connect

Meelezers:

- Drs. F.Z. Ramjankhan, Cardio-thoracaal chirurg, NVT

- Dr. R.R.M. Vogels, Radioloog, NVvR

- Drs. R. ter Wee, Klinisch fysicus, NVKF

Met ondersteuning van:

- Drs. I. van Dusseldorp, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinsitituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. S.N. Hofstede, senior-adviseur, Kennisinsitituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. J.C. Maas, adviseur, Kennisinsitituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Endeman |

Internist-intensivist, opleider Intensive Care, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Secretaris GIC, lid sectie IC NIV aanpassing juli 2022:

|

Travelgrant/speakers fee voor IC-symposium Kenya augustus 2018 door GETINGE

Advanced mechanical ventilation is een speerpunt van wetenschappelijk onderzoek van de Intensive Care van het Erasmus MC aanpassing juli 2022: gesponsord door Ventinova. Dat is een beademingsmachine. Open Lung Concept 2.0: Flow Controlled Ventilation |

Bij modules die specifiek gaan over apparatuur ontwikkeld door GETINGE: Wanneer dit onderwerp geprioriteerd wordt zal een vice-voorzitter worden aangewezen en werkgroeplid niet meebeslissen over dit onderwerp |

|

Pauw |

Intensivist longarts Martini Ziekenhuis Groningen |

Secretaris sectie IC NVALT (onbetaald), instructeur FCCS-cursus NVIC (vergoeding per gegeven cursus, gemiddeld 1-2x/jaar) |

Maart 2023: Spreker congres pulmonologie vogelvlucht: pulmonary year in review m.b.t. IC-onderwerpen |

Geen |

|

Jonkman |

* Technisch geneeskundige (klinisch technoloog), PhD kandidaat en research manager, afdeling Intensive Care Volwassenen, Amsterdam UMC, locatie Vumc (t/m 2021) * Research fellow dept. Critical Care Medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Canada (gedetacheerd vanuit VUmc voor periode jan-dec 2020)

aanpassing juli 2022: |

Bestuurslid Nederlandse Vereniging voor Technische Geneeskunde (NVvTG), vice-voorzitter t/m mei 2021 |

Adviesfunctie (consultancy) bij Liberate Medical LLC (Kentucky, USA), een medical device company dat een niet-invasieve elektrische spierstimulator ontwikkelt voor het trainen van de expiratiespieren (buikspieren) tijdens kunstmatige beademing. Betaald consultancy werk, ongeveer 1-2 dagdelen per jaar (2018 -2020)

Deelname aan diverse nationale en internationale investigator-initiated wetenschappelijke onderzoeken naar gepersonaliseerde kunstmatige beademing middels advanced respiratory monitoring (o.a. ademspierfunctie en electrische impedantie tomografie) bij de IC-patiënt. Deels in het kader van voormalig promotieonderzoek Waaronder: * lid stuurgroep CAVIARDS-trial (Careful Ventilation in (COVID-19-induced) Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, NCT03963622), internationale investigator-initiated studie naar gepersonaliseerde beademingsstrategie bij ARDS, geen persoonlijke financiële vergoeding |

Onderwerpen niet-invasieve elektrische spierstimulatie en gepersonaliseerde kunstmatige beademing middels advanced respiratory monitoring worden niet behandeld in de richtijn. Mochten deze toch worden toegevoegd, dan zal werkgroep lid niet als auteur van deze specifieke modules worden aangesteld. |

|

Samuels |

Anesthesioloog – Intensivist, te Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland

aanpassing Juli 2022: Anesthesioloog-lntensivist, te HMC |

* MICU intensivist – betaald * FCCS teacher – betaald * bestuurslid sectie IC NVA

aanpassing Juli 2022: Waarnemer als lntensivist op de IC (betaald) Voorzitter sectie IC, NVA (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

De Graaff |

Intensivist – Internist, St Antonius ziekenhuis Nieuwegein, fulltime |

Bestuurslid Stichting NICE, vrijwilligerswerk |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Determann |

Intensivist OLVG |

Gastdocent Amstelacademie (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Brackel-Welten |

* Voorzitter patiëntenorganisatie IC Connect, onbetaald, tot 1-1-2022 * Bestuurslid Stichting Family en patient centered Intensive Care (Stichting FCIC), onbetaald, tot 1-1-2022 * Jeugdarts KNMG, niet praktiserend * voormalig IC-patiënte |

Geen |

Voorzitterschap IC Connect, bestuurslid Stichting FCIC, tot 1-1-2022 |

Geen |

|

Snoep |

* Ventilation Practitioner 25% * IC-verpleegkundige 75%

aanpassing juli 2022: Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum

|

Hamilton Medicai expert panel Netherlands, sinds 2022. Onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Ramjankhan |

Cardio-thoracaal chirurg UMCU |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Ter Wee |

Klinisch Fysicus in opleiding - Medisch Spectrum Twente |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Vogels |

*Radioloog met aandachtsgebied thoracale en abdominale radiologie * Fellow Thoraxradiologie

Maatschap Radiologie Oost Nederland (MRON) locatie MST Enschede

Toevoeging juli 2022: Radioloog met als aandachtsgebied thoracale en abdominale readiologie als maatschapslid bij MRON licatie ZGT Almelo/Hengelo |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting FCIC, IC Connect en het Longfonds voor deelname aan de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en deelname van een afgevaardigde van Stichting FCIC en IC Connect in de werkgroep. De resultaten van de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarsiatie zijn besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting FCIC, IC Connect en het Longfonds. De eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Methode van beademing – Buikligging |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven.

|

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met ARDS. Tevens zijn IGJ, NFU, NHG, NVZ, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, STZ, V&VN, NVIC, NVA, NIV, NVALT, NVvTG, NVVC, NVN, NVKF, Longfonds, FCIC/IC Connect en ventilation practitioners uitgenodigd om knelpunten aan te dragen via een enquête. Een overzicht hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties uit de werkgroep voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.