Revalidatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van revalidatie na chirurgische of conservatieve behandeling van een primaire Achillespeesruptuur?

Aanbeveling

Bespreek een revalidatieprogramma met de patiënt.

Overweeg de volgende componenten in een revalidatieprogramma toe te passen en individualiseer op basis van specifieke patiëntkarakteristieken en de voortgang van de revalidatie:

- Twee tot twaalf weken: opbouwende range of motion oefeningen van de enkel tot een neutrale enkelpositie (indien het gekozen beschermingsmiddel dit toelaat).

- Drie tot zes weken: opbouwende isometrische krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren met de enkel in plantairflexie en opbouwen naar een neutrale enkelpositie.

- Zes tot twaalf weken: opbouwende krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren in enkel plantairflexie en neutrale enkelhoek voor het stimuleren van hypertrofie.

- Vanaf twaalf weken: opbouwende krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren met opbouwende range of motion oefeningen van de enkel in dorsaalflexie voor het stimuleren van hypertrofie en functie.

Adviseer sporters om het revalidatieprogramma na twaalf weken verder op te bouwen.

Individualiseer op basis van de vereisten van de sport en de voortgang van de revalidatie. Voeg de volgende oefeningen toe aan het revalidatieprogramma:

- Progressieve krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren

- Plyometrische oefeningen

- Sport-specifieke oefeningen

Bespreek samen met de patiënt het meest passende tijdstip van het starten met belasten na zowel operatieve als conservatieve behandeling, waarbij het veilig is:

- Nul tot twee weken: opbouwend belasten, op geleide van de pijn met krukken.

- Vanaf week drie: volledig belasten op geleide van de pijn.

Gebruik een brace of walker gedurende zes tot acht weken.

Gebruik een hakverhoging die binnen zes tot acht weken in hoogte wordt afgebouwd naar een neutrale positie van de enkel.

Geef voldoende voorlichting aan de patiënt over het te verwachten beloop. Overweeg de volgende gegevens te bespreken voor een realistische verwachting van het beloop, waarbij een zekere spreiding te verwachten is, na een achillespeesruptuur (initieel operatief of conservatief behandeld):

- Binnen drie tot zes maanden kunnen de meeste patiënten normaal functioneren in ADL

- De kans op complicaties binnen een jaar is klein (zie module 'chirurgische behandeling').

- Ongeveer de helft (52%) van de sporters is na een jaar teruggekeerd in sport. Van de sporters die binnen een jaar zijn teruggekeerd, is de gemiddelde tijd tot initiële terugkeer 26 weken. De terugkeer in de sport is afhankelijk van het type sport en gewenste niveau van terugkeer.

De overgrote meerderheid (78%) keert na twee tot drie maanden volledig terug naar werk. De gemiddelde tijd tot terugkeer naar werk is bijna drie weken; deze tijd is sterk afhankelijk van het type werk en de vereiste belastbaarheid.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is voor de module revalidatie literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van actieve revalidatie versus geen revalidatie na een chirurgische of conservatieve behandeling van een achillespeesruptuur. Ook is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van vroeg belasten versus laat belasten na chirurgische of conservatieve behandeling van een achillespeesruptuur. Dagelijks functioneren werd gedefinieerd als een cruciale uitkomstmaat voor besluitvorming. Re-rupturen, kwaliteit van leven, spierkracht, torsie, complicaties (elongatie van de achillespees en diep veneuze trombose), terugkeer naar sport en/of werk en de tijd van terugkeer naar sport en/of werk werden als belangrijke uitkomstmaten gedefinieerd.

PICO 1: Actieve revalidatie versus geen revalidatie

De werkgroep heeft ‘actieve revalidatie’ gedefinieerd als het toepassen van actieve oefentherapie en een opbouw in belasting. Een afwachtend beleid of het toepassen van passieve modaliteiten werd geclassificeerd als ‘geen revalidatie’.

Uit het literatuuronderzoek kwamen geen studies naar voren die rapporteerden over actieve revalidatie na een chirurgisch of conservatief behandelde achillespeesruptuur in vergelijking met geen revalidatie. Er kon zodoende geen literatuuranalyse worden uitgevoerd en er konden geen GRADE-conclusies worden opgesteld voor deze vergelijking.

Deze bevindingen zijn in lijn met de bestaande beschrijvende literatuuronderzoeken, waarin de onderbelichting van componenten van actieve revalidatie worden gerapporteerd (Christensen, 2020). Indien een actief revalidatieprogramma wordt beschreven, dan is dit vaak alleen gedaan in de vroege fase van de revalidatie (<8 weken) en niet over een langere periode. Gezien het feit dat de gemiddelde terugkeer naar sporten en bewegen zes maanden is, is het wenselijk om componenten van een actieve revalidatie over een langere periode te beschrijven.

In een recente internationale consensus meeting met chirurgen (n=4) en een fysiotherapeut (n=1) werd overeenstemming bereikt over componenten van actieve revalidatie (na een operatieve ingreep) bij patiënten met een primaire achillespeesruptuur (Saxena, 2022). De belangrijkste bevindingen waren als volgt:

- Na twee tot drie weken kan worden gestart met fietsen op een hometrainer, waarbij de hiel op het pedaal wordt geplaatst.

- Na drie weken kan worden gestart met range of motion oefeningen van de enkel tot een neutrale enkelpositie.

- Na zes weken kan worden gestart met tweebenige concentrische heel raises.

- Na twaalf weken kan worden gestart met tweebenige excentrische oefeningen, indien de concentrische oefeningen goed kunnen worden uitgevoerd.

- Na twaalf weken kunnen passieve rekoefeningen in enkel-dorsaalflexie worden geïnitieerd.

- Terugkeer in hardloop activiteiten kan worden geïnitieerd op basis van de eenbenige heel raise endurance test. Er werd daarbij geen waarde benoemd die leidend is om een veilige terugkeer naar sport te starten.

- De gemiddelde terugkeer naar sport is 24 weken (range 22-26 weken). Hierbij wordt benadrukt dat het gaat om initiële participatie in sport (dus nog geen sport in competitieverband). De duur en invulling van de revalidatie is ook afhankelijk van de gewenste sport (mate van benodigde explosieve spierkracht) en sportniveau. Benadrukt moet worden dat dit gemiddelde en de spreiding is gebaseerd op basis van ervaring en consensus. De wetenschappelijke literatuur toont andere getallen, waarbij vooral de spreiding groter is (zie verderop in de overwegingen).

Deze aspecten kunnen een leidraad vormen voor een actief revalidatieprogramma. Hierbij kan het doel van de patiënt als uitgangspunt worden genomen. Opbouw van de specifieke achillespees-belastende oefeningen kan helpen om de belastbaarheid van de pees te verhogen (Aspenberg, 2007). Ook kan het gunstige psychologische effecten hebben. Een recent Nederlands onderzoek laat zien dat een actieve revalidatie leidt tot minder kinesiofobie en patiënten met een primaire achillespeesruptuur voelen zich meer gereed om terug te keren naar hun sport dan aan het begin van hun revalidatie (Slagers, 2021). Op basis van expertise heeft de werkgroep een aantal toevoegingen. Omdat de belasting met lichaamsgewicht al volledig kan zijn na twee weken en de achillespees dan in plantairflexie hoeken wordt belast, is de werkgroep van mening dat oefeningen in deze fase al op geleide van de pijnklachten kunnen worden uitgebreid met isometrische vormen in plantairflexie hoeken (en opbouw naar een neutrale enkelhoek). Daarnaast is de werkgroep van mening dat, in geval van een revalidatiedoel met terugkeer in de sport, vormen van plyometrie in de revalidatie een rol zouden moeten hebben, om zo de brug te vormen in belastingopbouw vanuit excentrische vormen naar terugkeer in sport. Dit geldt voor sporten waar hardloopvormen en/of sprongvormen worden toegepast. Dit is op basis van klinische expertise en ook op basis van de richtlijn ‘achilles tendinopathie’, waarin een vergelijkbare opbouw wordt gehanteerd (de Vos, 2021).

De exacte invulling van de revalidatie hangt af van de doelen van een patiënt. Een belangrijke subgroep van patiënten is de sporter. Daar waar de inactieve patiënt na gemiddeld twaalf weken revalidatie voldoende functie heeft opgebouwd voor het uitvoeren van ADL activiteiten, is het voor de sporter een overweging om middels gerichte oefeningen (zwaardere isotonische krachttraining, excentrische krachtoefeningen, plyometrie en sport-specifieke oefeningen) naar een sportief doel toe te werken.

PICO 2: vroeg belasten versus verlaat belasten

De werkgroep definieerde vroeg belasten op voorhand als volledig belasten binnen nul tot drie weken en definieerde laat belasten als belasten na drie weken. Er zijn twee studies (Aufwerber, 2020; Eliasson, 2018) opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse waarin onzekerheid is over de categorisering van de interventie. De studie van Aufwerber (2020) instrueerde patiënten in de interventiegroep om direct te belasten, terwijl de controlegroep na twee weken mocht starten met volledig belasten. De studie van Eliasson (2018) instrueerde patiënten in de interventiegroep om vanaf dag één te belasten en op te bouwen naar volledig belasten in vijf weken, terwijl de controlegroep werd geïnstrueerd om de aangedane zijde volledig te ontlasten tot aan de zevende week. In de studie van Okoroha (2020) werden de patiënten in de interventiegroep geïnstrueerd om binnen de eerste 6 weken te belasten op basis van wat getolereerd werd door de patiënt. Ook in deze studie is dus niet met zekerheid aan te geven of de patiënten in de interventiegroep binnen de eerste drie weken tot volledige belasting zijn gekomen. Ondanks dat bovengenoemde interventies niet zuiver binnen de vooropgestelde definities van vroeg en laat belasten voldeden, werden deze studies opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse van de module. De reden hiervoor is dat de criteria voor vroeg en laat belasten in bovengenoemde studies een onzekerheid houden. Het is op basis van de data namelijk niet te achterhalen hoe de patiënten de adviezen voor belasting daadwerkelijk hebben ingevuld. Aangezien er in alle bovengenoemde studies een duidelijk contrast is voor het moment waarop patiënten geadviseerd werden om te starten met belasten van de aangedane zijde (rond het vooraf geformuleerde afkappunt), is de werkgroep van mening dat deze studies relevant zijn voor de beantwoording van PICO 2.

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat dagelijks functioneren werden er geen klinisch relevante verschillen in de gemiddelde Achilles Tendon Rupture Score gevonden. Daardoor lijkt er weinig tot geen verschil in het niveau van dagelijks functioneren te zijn als er vroeg wordt gestart met belasten in vergelijking met verlaat belasten. Ook in de vroege fase na de achillespeesruptuur (nul tot zes maanden follow-up) was er in de meerderheid van de onderzoeken geen verschil in de gemiddelde Achilles Tendon Rupture Score tussen vroeg belasten en verlaat belasten (Aufwerber, 2019; Eliasson, 2018; Okoroha, 2020; Meampel, 2020). Deze bevindingen gelden zowel na een chirurgisch als conservatief behandelde achillespeesruptuur. De bewijskracht voor deze bevindingen is laag. Ditzelfde geldt voor de belangrijke uitkomsten re-rupturen en terugkeer naar sport. De literatuur is erg onzeker over het effect van vroeg belasten in vergelijking met verlaat belasten voor complicaties (zoals diep veneuze trombose), terugkeer naar werk, tijd tot terugkeer naar sport, ‘heel raise height’ en kwaliteit van leven (zeer lage bewijskracht). Er kon geen uitspraak worden gedaan voor de uitkomsten spierkracht, torsie en achillespees elongatie, omdat in geen van de geïncludeerde studies één van deze uitkomsten werd gerapporteerd. Alleen op de uitkomstmaat tijd tot terugkeer naar werk lijkt er een klinisch relevant verschil te zijn (gemiddeld bijna twee weken snellere terugkeer) in het voordeel van een vroege functionele belasting. De bewijskracht hiervoor is laag.

Een subgroep patiënten waarbij er meer voordeel van vroeg belasten lijkt te zijn, is de werkende populatie. Dit is vooral doordat er een eerdere terugkeer naar werk lijkt te zijn bij vroeg belasten versus laat belasten. Andersom betekent dit dat de niet werkende, veelal oudere, populatie dit voordeel niet heeft. Bij deze groep kan er een andere afweging worden gemaakt. Vooral als een patiënt minder goed ter been is en er een hoger valrisico is, kan er worden gekozen voor het toepassen voor een latere initiëring van de belasting.

Sinds het einde van de jaren tachtig is er een toegenomen gebruik van vroege belasting gedurende de immobilisatiefase van een achillespeesruptuur. Deze multimodale strategie heeft elementen die variëren van gewichtsdragende en algemene oefeningen tot specifieke oefeningen bedoeld om de achillespees te belasten. De theorie is dat vroege belasting de nadelige effecten van immobilisatie (zoals kuitspier atrofie met verminderde functie en kans op complicaties) minimaliseert en voldoende rekkrachten genereert om peesherstel te stimuleren (Zellers, 2019). Anderzijds kan vroege belasting theoretisch leiden tot negatieve effecten, zoals een hoger risico op elongatie van de pees en het ontstaan van re-rupturen. De wetenschappelijke literatuur laat voor deze theorieën geen bewijs zien, al is hierover wel onzekerheid door de beperkte bewijskracht. Er lijkt wel een gunstig effect te zijn van vroeg belasten op tijd tot terugkeer naar werk, en er lijken geen negatieve effecten te zijn. Ook op kinesiofobie kan vroeg belasten theoretisch een gunstig effect hebben; dit is van belang aangezien een verhoogde kinesiofobie een negatief effect op de revalidatie kan hebben (Slagers, 2021). Om deze redenen geeft de werkgroep aan dat vroeg belasten te overwegen is bij de behandeling van een primaire achillespeesruptuur.

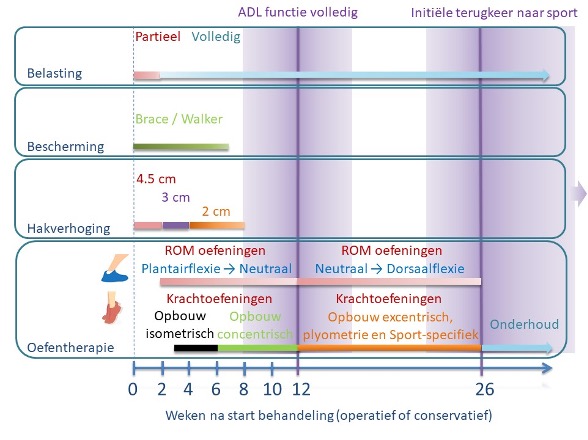

De exacte timing en inhoud van het vroege belasten is heel variabel beschreven in de literatuur (Zellers, 2019). Daar komt bij dat de beschrijving vaak heel beperkt is (Christensen, 2020). Dit maakt het uitvoeren van een synthese van de literatuur complex. Grofweg kan de vroege revalidatie in twee componenten worden ingedeeld: het belasten van het aangedane been in de dagelijkse activiteiten en het uitvoeren van gerichte oefeningen. Daarnaast worden in de praktijk nog aanvullende behandelingen toegevoegd, zoals bescherming met een brace of walker en een hakverhoging. De werkgroep is van mening dat een algemene leidraad voor de componenten van deze vroege belasting wenselijk is. Op basis van de bestaande literatuur en expertise van de werkgroep is een overzicht van deze leidraad weergegeven in Figuur 8.

Belasting

De belasting wordt in sommige studies direct na de initiële interventie (operatief of conservatief) geadviseerd om volledig uit te voeren met gebruik van krukken (Aufwerber, 2019; Costa, 2003; Costa, 2006; de la Fuente, 2016; Kastoft, 2018; Korkmaz, 2015, Maempel, 2020, Schepull, 2013, Valkering, 2017, Young, 2014). In andere studies is er sprake van een periode van partiele belasting met krukken (Aufwerber, 2021; Eliasson, 2018; Okoroha, 2020; Porter and Shadbolt, 2014) en in weer een aantal andere studies wordt een periode van onbelaste activiteiten geadviseerd of er werd hierover niet duidelijk gerapporteerd (Barfod, 2020; Kangas, 2003; Lantto, 2015; Kauranen, 2002).

Oefeningen

Oefeningen kunnen dienen om de patiënt fit te houden, mobiliteit van gewrichten te onderhouden, spiergroepen sterker te maken om belasting van het been beter te kunnen ondersteunen en/of de achillespees en kuitspieren te versterken. In de geïncludeerde artikelen worden range of motion oefeningen van de enkel en weerstandsoefeningen van de onderste extremiteiten beschreven als onderdeel van de vroege belasting. Weerstandsoefeningen lijken van cruciaal belang in de context van peesgenezing (Martin, 2018). Oefenprogramma's bevatten normaliter descriptoren zoals aantal herhalingen, aantal sets, gebruik van externe gewichten en tijd onder spanning. Het is aannemelijk dat deze parameters relevant zijn voor het stimuleren van peesgenezing. Echter, ook hier is er veel variabiliteit in de timing en beschrijving van de oefeningen. Een ander nadeel is dat deze oefeningen vaak slecht zijn beschreven in de literatuur (Christensen, 2020). De meest voor de hand liggende en in de literatuur meest genoemde oefening voor de achillespees is de standing heel raise. Daarnaast is de seated heel raise een oefening die goed ingezet kan worden. Eventueel kan in de eerste weken gebruik gemaakt worden van een weerstandsband (elastiek). Vanuit de ervaring van de werkgroep adviseren we om de in ieder geval vanaf 8 weken de oefenparameters te richten op hypertrofie. De patiënt kan via deze weg een opbouw maken naar uitvoer van ADL activiteiten. Voor sporters is het een overweging om middels zwaardere isotonische krachttraining, plyometrie en sport-specifieke oefeningen naar het sportieve doel toe te werken. Ook adviseert de werkgroep een onderhoud van isotonische oefeningen in de fase na terugkeer naar sport.

Figuur 8 – de opbouw van de belasting, gebruik van externe bescherming, toepassing van hakverhoging en opbouw van de oefentherapie in de loop van de tijd voor patiënten met een doorgemaakte achillespeesruptuur (initieel operatief of conservatief behandeld) staat in dit figuur overzichtelijk weergegeven. De uitleg van deze specifieke elementen van revalidatie wordt in de overwegingen nader besproken. Dit overzicht vormt een leidraad en het laat ook al zien dat er spreiding is tussen individuen. Personalisering op basis van specifieke patiënt karakteristieken en de voortgang van de revalidatie is noodzakelijk. ADL = Algemeen Dagelijks Leven. ROM = Range of Motion.

Bescherming

Externe support door brace of gips wordt in vrijwel alle geïncludeerde studies beschreven. Er is veel variabiliteit in het gebruik van het type brace of gips en de duur van het gebruik. Een walker (Maempel, 2020; Korkmaz, 2015; Suchak, 2008; Costa, 2006, Costa, 2003), dynamische brace (Aufwerber, 2021; Aufwerber, 2019), aircast (Barfod, 2020), achillotrain, gips (Groetelaers, 2014; Young, 2014) of een combinatie van verschillende soorten externe support is beschreven. Gezien de heterogeniteit van de studies en het ontbreken van studies die een dynamische brace (ROM mogelijk binnen toegestane plantairflexie) vergelijken met andere braces die lichaamsbelasting direct tolereren, heeft de werkgroep geen voorkeur voor het gebruik van een specifieke brace. De duur van het gebruik van externe support varieerde in de onderzoeken van 5 tot en met 8 weken.

Hakverhoging

Het doel van een hakverhoging is om de rekbelasting op de achillespees te verminderen. Theoretisch kan dit het initiële herstel bevorderen en de kans op elongatie verminderen. Het gebruik van hakverhogingen in de eerste fase van de revalidatie is ook heel heterogeen beschreven in de literatuur. In de meerderheid van de onderzoeken werd het gebruik van een hakverhoging wel beschreven (Aufwerber, 2021; Aufwerber, 2019; Barfod, 2020; Costa, 2006; Costa, 2003; Groetelaers, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015; Maempel, 2020 Young, 2014). De heterogeniteit geldt ook voor de duur van het gebruik en de hoogte van de hakverhoging. De duur van het gebruik van een hakverhoging varieerde in de onderzoeken van 5 tot en met 12 weken. De hoogte van de hakverhoging varieerde van 4.5 cm tot en met 2 cm met een geleidelijke afbouw in de loop van de weken.

Door de grote heterogeniteit in de toepassingen van externe support en hakverhogingen, is het niet mogelijk om een uitspraak te doen over de effectiviteit en dus om een specifieke brace of hakverhoging te adviseren. In de Nederlandse situatie worden zowel een externe support als een hakverhoging vaak gedurende 6-8 weken geadviseerd.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Er is geen onderzoek verricht naar de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten bij het vroege belasten en het uitvoeren van oefeningen in het kader van de revalidatie. Een vroegere terugkeer naar werk zal in het algemeen als een belangrijk effect worden beschouwd door de werkende patiëntenpopulatie. Het is ook aannemelijk dat patiënten wel meer mobiliteit en vertrouwen zullen ervaren door vroege belasting.

Vanuit de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland kwam naar voren dat er wens is voor een adequate voorlichting over de verwachting van het herstel van een achillespeesruptuur. Vanuit de uitkomstmaten gericht op het domein functie komt naar voren dat binnen drie tot zes maanden een klinisch relevant verschil kan worden verwacht. Dit betekent dat patiënten na een achillespeesruptuur (initieel operatief of conservatief behandeld) gemiddeld genomen na drie maanden kunnen merken dat ze in ADL weer beter kunnen functioneren. De kans op complicaties is klein (de kans op een re-ruptuur binnen een jaar is voor zowel patiënten die vroeg belasten als patiënten die laat belasten gemiddeld ongeveer 2-10% en op diep veneuze trombose ongeveer 1-2%). Meer dan de helft (ongeveer 52%) van de patiënten keert terug in sport na een jaar, met een gemiddelde tijd tot initiële terugkeer van 26 weken. Dit is vaak nog niet op het niveau van voor de blessure. De spreiding van de gemiddelde initiële terugkeer naar sport is echter groot tussen de verschillende onderzoeken (17 tot 39 weken). Het overgrote deel van de patiënten (ongeveer 78%) is na twee tot drie maanden teruggekeerd naar het werk, met een gemiddelde tijd tot terugkeer van bijna drie weken. De percentages van terugkeer naar werk en sport zullen in de praktijk sterk afhangen van het type werk en sport. Dit wordt ook zichtbaar in de spreiding rondom deze gemiddelde waarden.

Bij de uitvoering van oefentherapie wordt er gevraagd om een tijdsbelasting voor de patiënt. Een deel van de patiënten zal gemotiveerd zijn om zelf aan hun herstel te kunnen bijdragen. Een groot deel van de oefeningen kan zelfstandig worden gedaan, wat patiënten in het algemeen als prettig ervaren. Er zal echter ook een deel van de patiënten zijn die moeite heeft met deze investering door gebrek aan tijd, motivatie, angst of een combinatie van deze factoren. Het is onbekend welk percentage van patiënten na een primaire achillespeesruptuur een goede motivatie heeft om oefeningen te doen. Ook zijn er geen onderzoeken geïdentificeerd die het effect van actieve revalidatie hebben onderzocht ten opzichte van afwachtend beleid (ook niet in subgroepen, zoals sporters). Er is dus veel onzekerheid over de waarden en voorkeuren omtrent het uitvoeren van oefentherapie.

Er is één kwalitatief onderzoek naar de factoren die van belang zijn voor actieve patiënten die een achillespeesruptuur hebben opgelopen (Peterson, 2020). De hoofdthema’s die van belang blijken voor patiënten zijn persoonlijke motivatie, verandering van focus en vertrouwen in het zorgteam. Deze thema’s hebben het grootste belang voor patiënten bij de terugkeer naar de sport. Zorgverleners kunnen patiënten helpen bij het stellen van de juiste verwachtingen voor terugkeer naar sport en hen aanmoedigen door de uitdagingen te bespreken die ze tijdens hun revalidatie kunnen ervaren. Deze facetten zijn van cruciaal belang voor het faciliteren van een positieve ervaring en bereiken van hun doelen. De studie laat zien dat een sporter mogelijk niet terugkeert naar het sport type, niveau en de frequentie van vóór de blessure, maar dat er toch een bevredigende uitkomst kan zijn.

De sporter behoort tot een subgroep waar waarden en voorkeuren kunnen afwijken van de algemene populatie. Het minimale klinisch relevante verschil in tijd tot terugkeer naar sport dat door de werkgroep werd bepaald (4 weken) zal voor deze groep waarschijnlijk anders zijn. Waarschijnlijk geldt voor de sporter een korter klinisch relevant verschil. Doordat er vrijwel geen verschil was in tijd tot terugkeer in sport tussen vroeg en laat belasten, zal dit geen invloed hebben op de huidige besluitvorming. Wel is het goed om rekening te houden met de specifieke waarden en voorkeuren van deze subgroep.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Verwacht wordt dat de kosten voor de uitvoering van oefentherapie laag zijn, aangezien deze grotendeels zelfstandig uitgevoerd kunnen worden. De werkgroep geeft aan dat het kan worden overwogen om de voorlichting, belasting opbouw en instructies van de oefeningen te laten begeleiden door een gekwalificeerde zorgverlener, zoals een fysiotherapeut of sportarts. De informatievoorziening kan dan mondeling worden gedaan en er is mogelijkheid tot het stellen van vragen. In samenspraak met patiënten kan besloten worden of begeleiding wenselijk is en hoe deze begeleiding het beste kan worden ingevuld. Informatie via folders, een website of een applicatie kunnen dit ondersteunen en de noodzaak tot extra contacten met zorgverleners verminderen.

Er zijn geen studies uitgevoerd naar de (kosten)effectiviteit van het vroege belasten en adviseren en begeleiden van oefentherapie. Het vroege belasten kan direct minder zorgkosten opleveren, als hierbij specifieke type braces of walkers worden gebruikt in vergelijking met het gebruik van gips dat meerdere malen in een verschillende enkelhoek moet worden aangelegd (Costa, 2020). Om die reden heeft de werkgroep een voorkeur voor het gebruik van een brace of walker. Het belasten zelf zal voor de meeste patiënten geen extra kosten opleveren, omdat dit in veel gevallen zelfstandig kan worden uitgevoerd zonder aanvullende begeleiding. Daarnaast kunnen indirecte kosten lager zijn, doordat de patiënt eerder kan terugkeren naar werk.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Onderzoek naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van het uitvoeren van een oefenprogramma in het kader van revalidatie is afwezig. Overeenstemming over de invulling van het revalidatieprogramma tussen de verschillende (para)medische zorgverleners is van belang. Het huidige kennisniveau is daarbij een mogelijke barrière. Implementatie van de huidige richtlijn en adequate nascholing lijkt een belangrijke facilitator. Een andere belangrijke barrière die kan worden verwacht, is de therapietrouw van de patiënt. Er zal tijd moeten worden geïnvesteerd in een revalidatietraject, waarbij de patiënt ook zal moeten reizen voor begeleiding als hiervoor wordt gekozen. Een individuele benadering is hierbij van belang, waarbij rekening wordt gehouden met de waarden en voorkeuren van de individuele patiënt. Aangezien dit vaak trajecten van meerdere maanden zijn, is motivatie en discipline voor langere duur benodigd. Begeleiding door een (para)medische zorgprofessional kan een facilitator zijn voor dit potentiële probleem.

Onderzoek naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van vroege belasting en revalidatie bij patiënten met een achillespeesruptuur is momenteel ook afwezig. Voor het verstrekken van volledige en gestandaardiseerde informatie en voorlichting over de aandoening, toepassen van vroege belasting op een veilige manier en de instructies van oefentherapie is het wenselijk dat er overeenstemming is tussen de verschillende zorgverleners. Er kunnen specifieke gewoontes zijn in de geleverde zorg die een keuze aanvaardbaarder kunnen maken. In de Nederlandse situatie wordt externe support door een brace of walker en een hakverhoging normaliter zes tot acht weken toegepast. Dit valt binnen de grenzen die in de literatuur staan beschreven en daarom is deze termijn van zes tot acht weken sterk te overwegen. In de Nederlandse situatie is het minder gebruikelijk om direct te starten met volledige belasting. Implementatie van direct volledig belasten kan daardoor bemoeilijkt worden. De werkgroep is daarom van menig dat een periode van twee weken partieel belasten te overwegen is.

Het huidige kennisniveau en de aanvaardbaarheid van de interventie is daarbij een mogelijke barrière. Implementatie van de huidige richtlijn is daarbij belangrijk. Dit kan worden bekrachtigd door het opnemen van de resultaten van deze richtlijn in standaard onderwijs en nascholing voor de zorgverleners die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor achillespeesrupturen. In de Nederlandse situatie zijn multipele (para)medische disciplines betrokken bij de behandeling van een achillespeesruptuur. Een mogelijke barrière in de zorg voor patiënten met een achillespeesruptuur is de interdisciplinaire communicatie. Door directe communicatie tussen zorgverleners zal er meer overeenstemming zijn in het gepersonaliseerde behandelplan en daardoor ook meer vertrouwen bij de patiënt. Daarom is nadere uitwerking en afstemming waarschijnlijk bevorderlijk voor de implementatie.

Hoewel patiënten met een achillespeesruptuur in Nederland allen een gelijke toegang hebben tot de zorg, kan de vergoeding van fysiotherapeutische begeleiding afhankelijk zijn van de initiële keuze om een operatieve of conservatieve behandeling te starten. Deze initiële keuze kan dus een barrière vormen voor gewenste begeleiding in het traject, doordat dit voor de patiënt leidt tot hogere kosten. Dit kan leiden tot een onwenselijke ongelijkheid in zorg. Overleg met zorgverzekeraars is nodig om deze ongelijkheid te reduceren.

Rationale van de aanbeveling actieve revalidatie versus geen revalidatie: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Uit het literatuuronderzoek kwamen geen studies naar voren die rapporteerden over actieve revalidatie na een chirurgisch of conservatief behandelde achillespeesruptuur. De werkgroep is van mening dat actieve oefeningen bij kunnen dragen aan een optimaal herstel van een achillespeesruptuur. Dit is voornamelijk gebaseerd op klinische expertise. Het uitvoeren van actieve oefentherapie kan ook gunstige psychologische effecten hebben. In een recente internationale consensus meeting werd overeenstemming bereikt over componenten van actieve revalidatie na een operatie van een achillespeesruptuur. Belangrijke aspecten in deze consensus meeting waren de opbouw van range of motion oefeningen naar concentrische krachtoefeningen en vervolgens excentrische krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren. De werkgroep is van mening dat kan worden overwogen om ook isometrische krachtoefeningen in een vroeg stadium toe te passen om zo de belastbaarheid van de achillespees op een gecontroleerde manier op te bouwen. Ook is de werkgroep van mening dat het toepassen van range of motion oefeningen in dorsaalflexiehoeken van de enkel pas te overwegen zijn na twaalf weken. Dit kan theoretisch de kans op een onwenselijke elongatie van de achillespees verminderen. In de praktijk is een verminderde dorsaalflexie van de enkel bij de revalidatie geen relevant probleem, terwijl de elongatie wel tot significante problemen kan leiden. Na twaalf weken kan worden overwogen om isotonische (concentrische en excentrische) krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren voort te zetten. Gezien de kuitspieratrofie die nog op langere termijn na een achillespeesruptuur wordt gezien, is het voor het verkrijgen van een optimale functie een overweging om dit onderhoud voor ten minste een jaar na het letsel toe te passen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie voor sporters

De initiële belasting, bescherming en hakverhoging is voor alle patiënten hetzelfde. De invulling van het revalidatieprogramma hangt af van de doelen van de individuele patiënt. De sporter is vaak een subgroep met specifieke doelen. Deze doelen liggen voorbij de periode van drie tot zes maanden revalidatie, waarin een deel van de patiënten al voldoende ADL functie heeft verkregen. Omdat de gemiddelde sporter meer functionele capaciteit van de achillespees vereist, acht de werkgroep het zinvol om met patiënten uit deze subgroep een uitgebreidere revalidatie te bespreken. Voor de sporter is het een overweging om middels gerichte oefeningen (isotonische krachtoefeningen van de kuitspieren, plyometrie en sport-specifieke oefeningen) naar een sportief doel toe te werken. Dit is in de klinische praktijk gangbaar en het heeft in het algemeen ook gunstige effecten op psychologische uitkomstmaten. Bovendien is dit conform de hoofdthema’s die sportende patiënten hebben gedefinieerd bij de behandeling van een achillespeesruptuur.

Rationale van de aanbeveling vroeg belasten versus laat belasten: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Voor het verschil tussen vroeg of laat belasten werden er nauwelijks klinisch relevante verschillen gevonden op de cruciale en belangrijke uitkomstmaten tussen, en voor meerdere uitkomstmaten is onduidelijk wat het effect is door een gebrek aan bewijs. Alleen op de uitkomstmaat tijd tot terugkeer naar werk lijkt er een klinisch relevant verschil te zijn in het voordeel van een vroege functionele belasting met behulp van een externe support. Omdat er in de huidige dagelijkse praktijk zelden met volledige belasting wordt gestart en de patiënt vertrouwen zal moeten krijgen in het opbouwen van de belasting, adviseert de werkgroep om te overwegen om de patiënt de eerste twee weken partieel te laten belasten met krukken. Een brace of walker kan voor een periode van zes tot acht weken worden gebruikt, omdat dit eenmalig kan worden aangemeten en voldoende bescherming en ondersteuning biedt. Een hakverhoging kan vanaf het begin worden toegepast en in de loop van zes tot acht weken worden afgebouwd. Dit correspondeert met zowel de data uit de wetenschappelijke studies alsook de klinische praktijk in Nederland. Er wordt in deze aanbeveling geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen sporters en niet-sporters.

Voorlichting van de patiënt is van meerwaarde om een realistisch beeld over het beloop van het herstel van een achillespeesruptuur weer te geven. De werkgroep heeft de ervaring dat patiënten veel vraag hebben naar duidelijke informatie. Kwalitatief onderzoek laat zien dat patiënten waarde hechten aan persoonlijke motivatie en vertrouwen in het zorgteam (Peterson, 2020). Door concrete informatie kan dit vertrouwen verder toenemen, met als gevolg een wenselijke uitkomst voor de patiënt. Omdat deze informatievoorziening relatief weinig tijd kost en geen verwachte nadelen heeft, is de werkgroep van mening dat een volledige voorlichting sterk overwogen kan worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Revalidatie kan worden overwogen als onderdeel van de behandeling van een achillespeesruptuur. Revalidatie kan plaatsvinden na zowel een initiële operatieve als conservatieve behandeling. Revalidatie is een breed begrip, maar in dit kader wordt in deze module een component van actieve oefentherapie met een opbouw van belasting verstaan. De manier hoe de revalidatie als behandeling kan worden ingezet kan divers zijn. De revalidatie kan worden begeleid door een (para)medisch zorgverlener, maar er kan ook worden gedacht aan het inzetten van folders, een website of een applicatie ter ondersteuning. Gedacht wordt dat krachtoefeningen en gebalanceerde opbouw van de belasting van de kuitspieren tot een beter functioneel herstel van de achillespees leiden, maar te agressieve oefentherapie in de eerste fase van de behandeling kan leiden tot ongewenste elongatie van de achillespees. Het is onbekend wat een optimale opbouw is van een revalidatieprogramma en er is veel praktijkvariatie op dit gebied (Dams, 2019).

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

PICO 1: active rehabilitation versus no rehabilitation

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature it was not possible to draw any conclusion with regards to the outcomes daily functioning, re-ruptures, complications (such as deep venous thrombosis, tendon elongation), time to return to sport, return to sports, time to return to work, return to work, heel raise height, quality of life, and plantar flexor torque for the comparison of active rehabilitation compared with no rehabilitation in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Source(s): - |

PICO 2: early weightbearing versus late weightbearing

1. Daily functioning

|

Low GRADE |

Early weightbearing may result in little to no improvement in daily functioning when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Aufwerber (2020); Eliasson (2018); Kastoft (2018); Maempel (2020); Okoroha (2020). |

2. Re-ruptures

|

Low GRADE |

Early weightbearing may result in little to no reduction in the number of re-ruptures when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2003; Costa, 2006; De la Fuente, 2016; Groetelaers, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015; Suchak, 2008; Valkering, 2016; Young, 2014); Kastoft (2018); Maempel (2020); Okoroha (2020). |

Complications

3.a. Deep venous thrombosis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early weightbearing on deep venous thrombosis when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Costa, 2006; Groetelaers, 2014; Suchak, 2008); Maempel (2020); Okoroha (2020). |

3.b. Tendon elongation

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of statistical information, it was not possible to draw any conclusion with regards to the outcome tendon elongation for the comparison of early weightbearing compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Okoroha (2020). |

4. Time to return to sport

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early weightbearing on the time to return to sport when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Costa, 2003; Costa, 2006; Porter and Shadbolt, 2015). |

5. Return to sport

|

Low GRADE |

Early weightbearing may result in little to no increased rate of return to sports when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2006; Groetelaers, 2014; Suchak, 2008); Kastoft (2018). |

6. Time to return to work

|

Low GRADE |

Early weightbearing may result in a shorter time to return to work when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Lu (2019) (Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2006; De la Fuente, 2016; Groetelaers, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015; Young, 2014). |

7. Return to work

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early weightbearing on return to work when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Lu (2019) (Groetelaers, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015); Kastoft (2018). |

8. Heel raise height

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early weightbearing on heel raise height when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Sources: Eliasson (2018); Kastoft (2018). |

9. Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early weightbearing on quality of life when compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Source(s): Aufwerber (2020) |

10. Plantar flexor torque

|

No GRADE |

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw any conclusion with regards to the outcome plantar flexor torque for the comparison of early weightbearing compared with late weightbearing in patients with a primary, acute Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

Source(s): - |

Samenvatting literatuur

PICO 1: What is the value of rehabilitation after surgical or conservative treatment of a primary Achilles tendon rupture?

Due to the absence of studies meeting the selection criteria, no studies were included in the literature analysis.

PICO 2: What is the value of early weightbearing after surgical or conservative treatment of a primary Achilles tendon rupture?

Description of studies

Systematic review

The systematic review of Lu (2019) aimed to compare early functional rehabilitation with conventional cast immobilization in patients with acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Lu (2019) searched PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library, without language restrictions, until the 4th of May 2017. The eligibility criteria for inclusion in this systematic review were (I) randomized controlled trials; (II) studies dealing with cases of acute Achilles tendon ruptures receiving surgery or conservative treatment; (III) an intervention group, in which participants received early functional rehabilitation, and a control, in which participants received conventional cast immobilization; and (IV) studies that reported at least one of the following outcomes: complication rate, patient satisfaction rate, rehabilitation duration (time taken to return to work and sports), and the total number of patients returning to work or sports. Studies with incomplete data or data that could not be used for statistical analysis or reviews, letters or comments were excluded. In total, eleven trials from the systematic review of Lu (2019), involving 667 participants (546 males and 121 females), were included for the purpose of this guideline (Barfod, 2014; Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2003; Costa, 2006; De la Fuente, 2016; Groetelaers, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015; Porter and Shadbolt, 2015; Suchak, 2008; Valkering, 2017 and Young, 2014). Eight studies compared outcomes in patients who were treated surgically (Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2003; De la Fuente, 2016; Groetelaers, 2014; Porter and Shadbolt, 2015; Suckak, 2008 and Valkering, 2017) and three studies compared the outcomes after non-surgical treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture (Barfod, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015 and Young, 2014). One study included patients with acute Achilles tendon rupture treated surgically and patients receiving non-surgical treatment (Costa, 2006). The follow-up between the studies ranged from three to twelve months. The risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane risk assessment tool. The included outcomes in Lu (2019) were complications (such as re-rupture, and deep venous thrombosis), participation (time taken to return to work and sports, number of patients returning to work and sports), and patient satisfaction. The individual study characteristics of the included studies are described in the evidence table of this guideline.

Randomized controlled trials

Aufwerber (2020) conducted a randomized controlled trial that aimed to assess the efficacy of early functional mobilization compared with standard treatment in patients with an Achilles tendon rupture. In total, 149 patients were randomized in two groups. Patients in the intervention group (n=98) underwent early functional mobilization in a dynamic orthosis with adjustable range of motion. Patients could bear weight as tolerated directly after surgery. At two weeks, the range of motion of plantarflexion was increased for the following four weeks. Full weightbearing was allowed. Patients in the control group (n=51) received standard treatment with immobilization in a below-knee plaster cast for two weeks and were non-weightbearing with crutches. After removal of the cast, at two weeks postoperatively, the patients received a stable orthosis fixed at the ankle joint. Full weightbearing was allowed. Nine patients (9.2%) in the intervention group were lost to follow-up compared to seven patients (13.7%) in the control group at final analysis at twelve months. The reported outcomes in the study were patient-reported outcomes that assessed function (Achilles Tendon Rupture Score) and quality of life (RAND-36).

The randomized controlled trial of Maempel (2020) aimed to compare patient-reported outcomes after functional rehabilitation and early weightbearing in a walking boot compared with traditional cast immobilization with prolonged non-weightbearing in adult patients who were treated non-operatively for an Achilles tendon rupture. In total, 140 patients were randomized in two groups. Patients in the intervention group (n=69) received a walking boot with a three-centimeter internal heel raise and were advised to perform immediate full weightbearing with the aid of crutches for balance as needed. The walking boot was removed after eight weeks, and physical therapy commenced upon removal of the boot. Patients in the control group (n=71) had the injured side placed into a complete below-knee cast with the ankle in full equinus and were instructed to remain non-weightbearing on the affected side. After four weeks, patients received a complete below-knee cast in a semi-equinus position for a further four weeks and were instructed to remain non-weightbearing. After eight weeks, the limb was placed into a cast with the ankle in a plantigrade (neutral) position and the patient was advised to perform full weightbearing. After ten weeks, the cast was removed, and physical therapy was commenced. The length of follow-up was one year. The reported outcomes in the study assessed function (Achilles Tendon Rupture Score, Foot and Ankle Questionnaire, and the Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment), physical function capacity (single- and double heel raise), and complications (such as re-ruptures and deep venous thrombosis).

The randomized controlled trial of Okoroha (2020) aimed to determine whether accelerated rehabilitation results in better outcomes compared with traditional rehabilitation protocols. All patients underwent surgery in a modified Krackow technique. After the procedure, eighteen patients were randomized to either the accelerated or traditional rehabilitation protocols. Patients in the intervention group (N=10) were placed in a splint with the injured side in 20° of plantarflexion and remained non-weightbearing for two weeks. After two weeks, patients were instructed to use a boot with two heel wedges and were allowed to perform weightbearing as tolerated. At four weeks, patients were instructed to use one wedge, and at six weeks patients were allowed to perform weightbearing as tolerated in a flat shoe. Patients in the control group (N=8) were placed in a non-weightbearing cast with the injured side in 20° of plantarflexion after the procedure. They were instructed to remain non-weightbearing for six weeks with crutches followed by weightbearing as tolerated. After six weeks, both groups underwent an identical rehabilitation regimen using a standardized protocol. The maximum length of follow-up was 12 weeks. The reported outcomes in the study assessed function (Achilles Tendon Rupture Scores), range of motion (tendon elongation), and complications (such as re-ruptures, or deep venous thrombosis).

The randomized controlled trial of Eliasson (2018) aimed to examine the effect of different rehabilitation regimens in the first eight weeks in patients with surgically repaired Achilles tendon ruptures. In total, 75 patients were randomized in three different treatment groups. Patients in the intervention group (N=25) were instructed to perform partial weightbearing from day one and full weightbearing from week five. For this guideline, we combined both late weightbearing groups (n=50). Patients in both late weightbearing groups were completely restricted from weightbearing until week seven. Partial weightbearing with the use of crutches was allowed from week seven or eight and full weightbearing after week eight. One of these groups were instructed to perform additional unloaded ankle joint range of motion exercises from week three. Patients in all groups received the same instructions for standardized home exercise starting from week nine. Patients were allowed heel-rise exercises after sixteen weeks, jogging after 22 weeks and return to sports 34 weeks after surgery. The maximum length of follow-up was 52 weeks. The reported outcomes in the study were range of motion (tendon elongation, ankle range of motion), physical function capacity (plantar flexion heel raise height), and patient-reported outcomes that assessed function (Achilles Tendon Rupture Score and the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles questionnaire (VISA-A)).

The randomized controlled trial of Kastoft (2018) aimed to investigate the influence of early weightbearing on clinical outcomes compared to treatment without early weightbearing in patients treated non-operatively. The study reported long-term outcomes (4.5 years follow-up) from the randomized controlled trial of Barfod (2014), which is included in the systematic review of Lu (2019). Patients in the intervention group were allowed to perform full weightbearing from day 1 on the injured side. The control group was instructed to remain non-weightbearing for the first six weeks of treatment. In total, nineteen participants in the intervention group and eighteen participants in the control group were analyzed at 4.5 years follow-up. The reported outcome measures in the study were assessed function (Achilles Tendon Ruptures Scores), physical function capacity (heel rise height and heel raise work) and participation (return to work and return to sports).

Results

PICO 1: active rehabilitation versus no rehabilitation

Due to the absence of studies meeting the selection criteria, no studies were included that reported information regarding the outcomes daily functioning, re-ruptures, complications (such as deep venous thrombosis, or tendon elongation), return to sport, time to return to sport, return to work, time to return to work, heel raise height, quality of life, or plantar flexor torque in patients undergoing active rehabilitation compared to no rehabilitation.

Results

PICO 2: early weightbearing versus late weightbearing

1. Daily functioning

Achilles Tendon Rupture Score

The Achilles Tendon Rupture Score (ATRS) is a disease-specific, self-administered PROM that can be used to quantify functional outcomes related to symptoms and physical activity after treatment in patients with an Achilles tendon rupture (10 questions using an 11-point (0-10) Likert scale, in which zero means maximum disability and 100 points means no symptoms and full function/recovery).

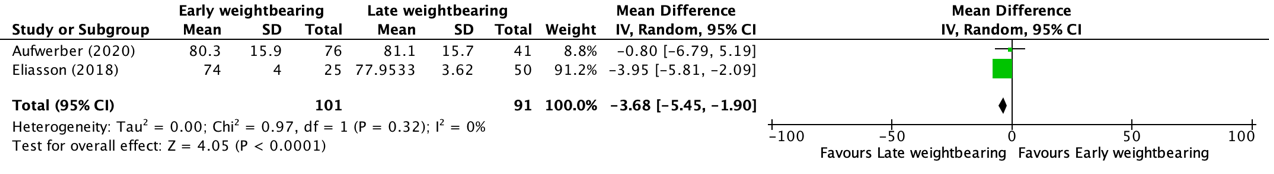

The ATRS was reported in five studies (Aufwerber, 2020; Eliasson, 2018; Maempel, 2020; Okoroha, 2020 and Kastoft, 2018) of which four with follow-up up to one year (Aufwerber, 2020; Eliasson, 2018; Maempel, 2020; Okoroha, 2020) and one study with follow-up at 4.5 years (Kastoft, 2018). The studies of Aufwerber (2020) and Eliasson (2018) both reported the mean (SD) Achilles Tendon Rupture Score, while Maempel (2020) reported the median (IQR) score and Okoroha (2020) only reported the mean score without a standard deviation. Kastoft (2018) reported the mean (SD) Achilles Tendon Rupture Score at 4.5 years follow-up. The results of Aufwerber (2020) and Eliasson (2018) were pooled in a meta-analysis. This resulted in a pooled mean difference (MD) of -3.68 (95% CI -5.46 to -1.90), in favor of the late weightbearing group (Figure 1). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between early weightbearing to late weightbearing for daily functioning (measured with the Achilles Tendon Rupture Score; 0-100 points). Pooled mean difference, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; SD: standard deviation; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Maempel (2020) reported the median Achilles Tendon Rupture Score and reported a median (IQR) score of 92 (72.50 to 96) for the early weightbearing group (n=65), compared to a score of 87.5 (66 to 94.75) for the late weightbearing group (n=60), in favor of the early weightbearing group. This is not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Okoroha (2020) reported the mean Achilles Tendon Rupture Score and reported a mean score of 85.4 for the early weightbearing group (n=10), compared to a score of 80.5 for the late weightbearing group (n=8). Due to the absence of a standard deviation, it is not possible to draw a conclusion regarding clinical relevance.

Kastoft (2018) reported the mean (SD) Achilles Tendon Rupture Score at 4.5 years follow-up. The mean (SD) score in the early weightbearing group was 82.8 (13.1), compared to 78.0 (23.6) in the late weightbearing group. This resulted in a mean difference (MD) of 4.80 (95% CI -7.59 to 17.19), in favor of the early weightbearing group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

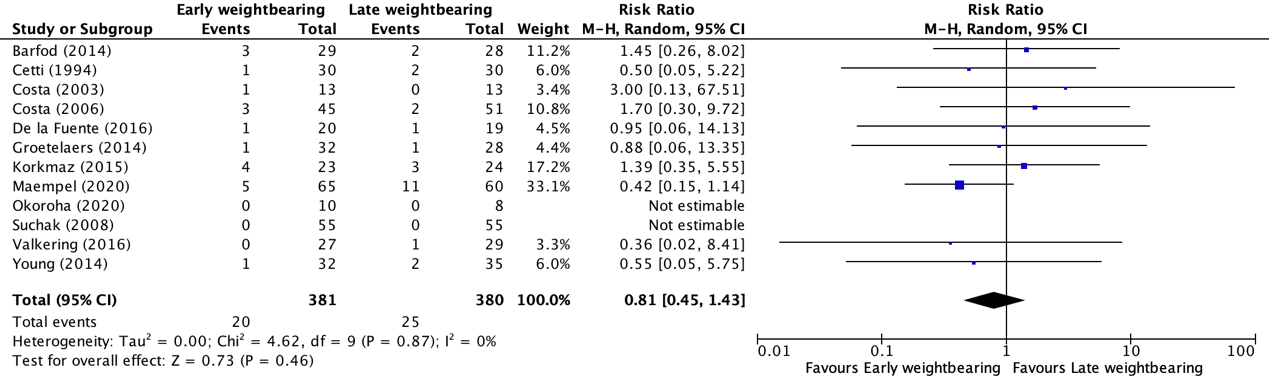

2. Re-ruptures

Re-ruptures within one year follow-up were reported in ten studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2003; Costa, 2006; De la Fuente, 2016; Groetelaers, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015; Suchak, 2008; Valkering, 2016 and Young, 2014) and two additional RCTs (Maempel, 2020 and Okoroha, 2020). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of patients with re-ruptures in the early weightbearing group was 20/381 (5.2%), compared to 25/380 (6.6%) in the late weightbearing group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.81 (95% CI 0.45 to 1.43) and a number needed to treat of 71.4, in favor of the early weightbearing group (Figure 2). This means that on average, 71 patients would have to undergo early weightbearing (instead of late weightbearing) for the prevention of one re-rupture. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the comparison between early weightbearing to late weightbearing for re-ruptures. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Kastoft (2018) reported the number of patients with re-ruptures but reported the results from one year up to 4.5 years follow-up. The number of patients with re-ruptures between one- and 4.5-years follow-up in the early weightbearing group was 0/19 (0%), compared to 0/18 (0%) in the control group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

3. Complications

Complications were reported in nine studies, of which seven studies were retrieved from the systematic review of Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2003; Costa, 2006; Groetelaers, 2014; Suchak, 2008 and Young, 2014) and two additional RCTs (Maempel, 2020 and Okoroha, 2020). Complications were defined as deep venous thrombosis and tendon elongation.

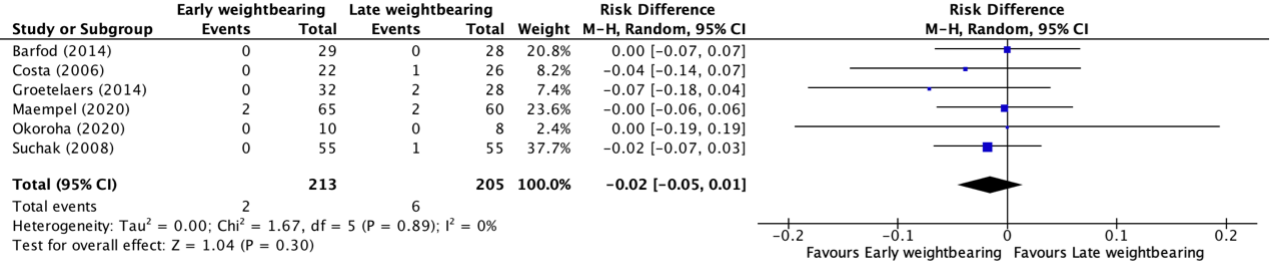

3.a. Deep venous thrombosis

Deep venous thrombosis up to one year follow-up was reported in four studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Costa, 2006; Groetelaers, 2014 and Suchak, 2008) and two additional RCTs (Maempel, 2020 and Okoroha, 2020). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of patients with deep venous thrombosis in the early weightbearing group was 2/213 (0.9%), compared to 6/205 (2.9%) in the late weightbearing group. This resulted in a pooled risk difference (RD) of -0.02 (95% CI -0.05 to 0.01), in favor of the early weightbearing group (Figure 3). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the comparison between early weightbearing to late weightbearing for deep venous thrombosis. Pooled risk difference, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

3.b. Tendon elongation

Tendon elongation up to one year follow-up was reported in one study (Okoroha, 2020). Okoroha (2020) reported the difference in tendon lengthening in millimeters. The mean tendon length in the study of Okaroha (2020) in the early weightbearing group (n=10) was 16.4 millimeter, compared to 15.3 millimeter in the late weightbearing group (n=8). Due to the absence of a standard deviation, it is not possible to draw a conclusion regarding clinical relevance.

4. Time to return to sport

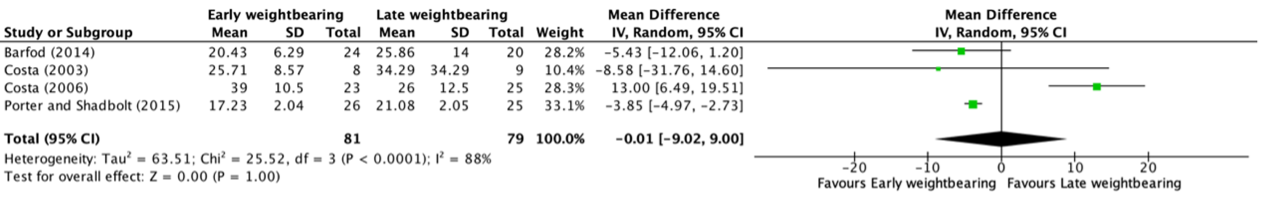

Time to return to sport up to one year follow-up was reported in four studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Costa, 2003; Costa, 2006; Porter and Shadbolt, 2015). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. This resulted in a pooled mean difference (MD) of -0.01 (95% CI -9.02 to 9.00) weeks, in favor of the early weightbearing group (Figure 4). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the comparison between early weightbearing to late weightbearing for time taken to return to sport. Pooled mean difference, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

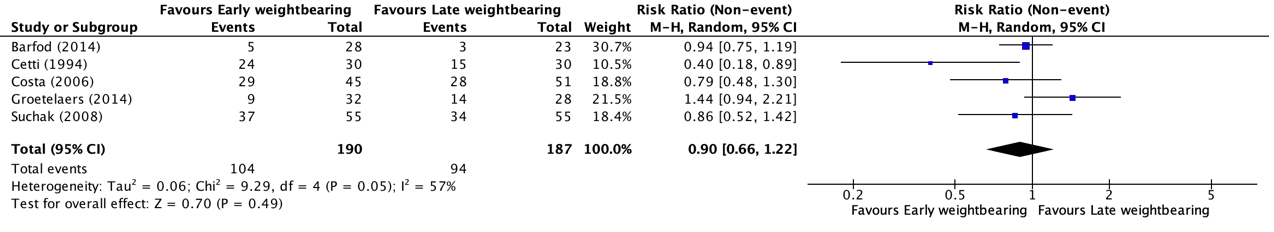

5. Return to sports

Return to sports up to one year follow-up was reported in five studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Lu (2019) (Barfod, 2014; Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2006; Groetelaers, 2014 and Suchak, 2008). One study reported 6-month results of return to sports (Suchak, 2008) and the other studies described one-year follow-up results. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of patients that returned to sports in the early weightbearing group was 104/190 (54.7%), compared to 94/187 (50.3%) in the late weightbearing group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.90 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.22), in favor of the early weightbearing group (Figure 5). This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 5. Forest plot showing the comparison between early weightbearing to late weightbearing for return to sports. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Kastoft (2018) reported the number of patients that returned to sports from one year up to 4.5 years follow-up. The number of patients in the early weightbearing group that returned to sports was 17/19 (89.5%), compared to 16/18 (88.9%) in the late weightbearing group. This resulted in a relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.95 (95% CI 0.15 to 6.03), in favor of the early weightbearing group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

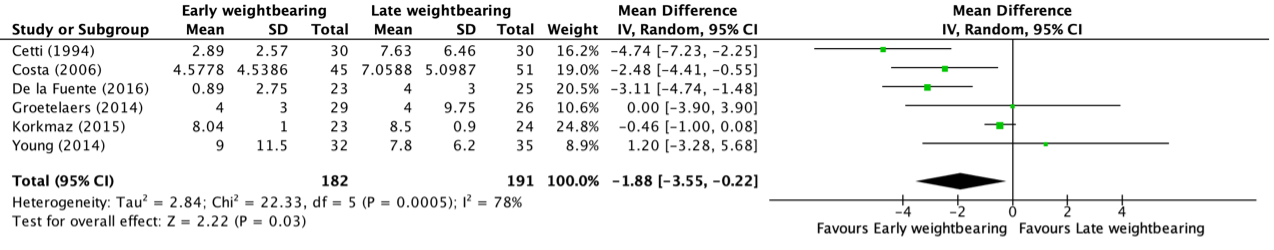

6. Time to return to work

Time to return to work up to one year follow-up was reported in six studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Lu (2019) (Cetti, 1994; Costa, 2006; De la Fuente, 2016; Groetelaers, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015; Young, 2014). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. This resulted in a pooled mean difference (MD) of -1.88 (95% CI -3.55 to -0.22) weeks, in favor of the early weightbearing group (Figure 6). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 6. Forest plot showing the comparison between early weightbearing to late weightbearing for time taken to return to work. Pooled mean difference, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

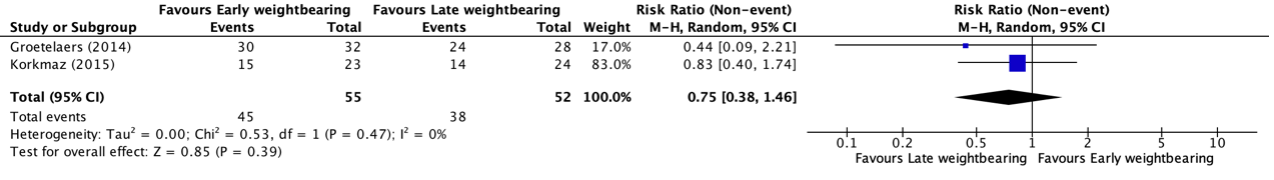

7. Return to work

Return to work was reported in two studies, retrieved from the systematic review of Lu (2019) (Groetelaers, 2014; Korkmaz, 2015). The studies reported return to work at different timepoints. Groetelaers (2014) reported the results at three months follow-up. Korkmaz (2015) reported return to work after two months follow-up. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled number of patients that returned to work in the early weightbearing group was 45/55 (81.8%), compared to 38/52 (73.1%) in the late weightbearing group. This resulted in a pooled relative risk ratio (RR) of 0.75 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.46), in favor of the early weightbearing group (Figure 7). This was considered as a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 7. Forest plot showing the comparison between early weightbearing to late weightbearing for return to work. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Kastoft (2018) reported the number of patients that returned to work from one year up to 4.5 years follow-up. The number of patients in the early weightbearing group that returned to sports was 19/19 (100%), compared to 18/18 (100%). This resulted in a relative risk ratio (RR) of 1.00 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.11), not favoring one of the treatment groups.

8. Heel raise height

Heel raise height was reported in two studies (Eliasson, 2018; Kastoft, 2018). Both studies reported the difference in heel raise height compared with the uninjured side; reported as a percentage. However, Eliasson (2018) reported the results at one year follow-up, while Kastoft (2018) reported long-term results at 4.5 years follow-up.

The mean (SD) heel raise height (difference with uninjured side; reported as percentage) in the study of Eliasson (2018) in the early weightbearing group (n=25) was 76.0 (4.0) percent, compared to 81.4 (3.2) percent in the late weightbearing group (n=50). This resulted in a mean difference (MD) of -5.40 percent (95% CI -7.20 to -3.59), in favor of the late weightbearing group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

The mean (SD) heel raise height (difference with uninjured side; reported as percentage) in the study of Kastoft (2018) in the early weightbearing group (n=19) was 79.7 (11.0) percent, compared to 85.1 (13.3) percent in the late weightbearing group (n=18). This resulted in a mean difference (MD) of -5.40 percent (95% CI -13.29 to 2.49), in favor of the late weightbearing group. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

9. Quality of life

Quality of life was reported in one study (Aufwerber, 2020). Quality of life was assessed with the RAND-36, which is a health-related quality of life questionnaire that consists of 36 items on physical and psychosocial health. It is divided into 8 subscales and scored on a verbal rating scale with different scoring alternatives with a range of total score from zero to 100. A higher score indicates better health status.

The mean (SD) RAND-36 score for the subscale ‘general health’ in the study of Aufwerber (2020) in the intervention group was 82.6 (16.9) points, compared to 77.1 (17.0) points in the control group. This resulted in a mean difference (MD) of 5.50 (95% CI -0.96 to 11.96) points. This was not considered as a clinically relevant difference.

10. Plantar flexor torque

None of the included studies for this guideline reported information with regards to the outcome plantar flexor torque in patients with an Achilles tendon rupture undergoing early weightbearing compared to late weightbearing.

Level of evidence of the literature

PICO 1: active rehabilitation versus no rehabilitation

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the predefined outcomes in patients with an Achilles tendon rupture undergoing active rehabilitation compared to no rehabilitation.

Level of evidence of the literature

PICO 2: early weightbearing versus late weightbearing

1. Daily functioning

The level of evidence regarding the outcome daily functioning was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding in the studies (risk of bias, -1) and the small number of patients in the studies (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

2. Re-ruptures

The level of evidence regarding the outcome re-ruptures was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the wide confidence interval crossing both borders of clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was low.

3. Complications

3.a. Deep venous thrombosis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome deep venous thrombosis was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the studies (risk of bias, -1), the wide confidence interval crossing both borders of clinical relevance and the small number of events (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

3.b. Tendon elongation

Due to a lack of relevant literature, it was not possible to draw any conclusion with regards to the outcome tendon elongation in patients with acute Achilles tendon ruptures undergoing early weightbearing compared to late weightbearing.

4. Time to return to sport

The level of evidence regarding the outcome time to return to sport was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the studies (risk of bias, -1), heterogeneity in the study results (inconsistency, -1), and the small number of patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is very low.

5. Return to sports

The level of evidence regarding the outcome return to sports was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding in the studies (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing both borders of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was low.

6. Time to return to work

The level of evidence regarding the outcome time to return to work was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding in the studies (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing the lowest border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence was low.

7. Return to work

The level of evidence regarding the outcome return to work was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the studies (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing both borders of clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was very low.

8. Heel raise height

The level of evidence regarding the outcome heel raise height was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the studies (risk of bias, -1) and the wide confidence interval crossing the lower and upper border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was very low.

9. Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome quality of life was derived from a randomized controlled trial and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding in the studies (risk of bias, -1), the small number of patients in the study, and the wide confidence interval crossing the upper border of clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

10. Plantar flexor torque

Because of a lack of data, it was not possible to grade the literature for the outcome torque in patients with acute Achilles tendon ruptures undergoing early weightbearing compared to late weightbearing.

Zoeken en selecteren

PICO 1

What is the value of rehabilitation after surgical or conservative treatment of a primary Achilles tendon rupture?

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the value of active rehabilitation after surgical or conservative treatment of a primary Achilles tendon rupture?

P: Patients with a primary Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

I: Active rehabilitation (with at least active exercise therapy and gradually increased load).

C: No active rehabilitation (wait and see or passive treatment).

O: Daily functioning; re-ruptures; quality of life; heel raise height; plantar flexor torque; elongation of the Achilles tendon; deep venous thrombosis; return to sport and/or work (dichotomous; yes/no); time to return to sport and/or work.

PICO 2

What is the value of early weightbearing after surgical or conservative treatment of a primary Achilles tendon rupture?

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the value of early weightbearing after surgical or conservative treatment of a primary Achilles tendon rupture?

P: Patients with a primary Achilles tendon rupture (who were treated surgically or conservatively).

I: Early weightbearing (start full weightbearing on the affected leg within 0-3 weeks after surgical treatment or the start of conservative treatment).

C: Late weight-bearing (start weightbearing after 4 weeks or later) / no complete full weight bearing on affected leg within 0-3 weeks after surgical treatment or start of conservative treatment.

O: Daily functioning; re-ruptures; quality of life; heel raise height; plantar flexor torque; elongation of the Achilles tendon; deep venous thrombosis; return to sport and/or work; time to return to sport and/or work.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered daily functioning as a critical outcome for decision making. Re-ruptures, quality of life, heel raise height, plantar flexor torque, complications (such as elongation of the Achilles tendon and deep venous thrombosis), return to sport and/or work, time to return to sport and/or work were regarded as important outcomes for decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. The outcomes return to sports, return to work, tendon elongation and heel raise height have not been validated and no clinically relevant differences are available for these outcomes. The working group predefined clinically important differences of these outcome measures based on clinical expertise with the aim to improve interpretability of the findings. For time to return to sports, a difference of four weeks was considered relevant for the general population. For time to return to work, the socio-economic impact was substantially higher and therefore a difference of one week was considered relevant for this outcome measure. There are different ways to measure tendon elongation, making it harder to define a relevant difference. One study showed 1.7 cm difference between affected and unaffected legs after 4.5 years follow-up without an associated difference in gait biomechanics (Kastoft, 2022). Another study showed a difference of 1.9 cm between a healthy population and individuals with chronic symptomatic Achilles tendon rupture (Nordenholm, 2022). The working group agreed that a value of 1.5 cm could be a relevant difference, based on the above-mentioned values. A difference of 20% in heel raise height (expressed as difference between affected and unaffected leg) was considered as relevant, based on a previous study (Nordenholm, 2022).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 21st of December 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 251 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials regarding the value of rehabilitation after surgical or conservative treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. Forty-five studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 39 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and six studies were included.

Results

Six studies were included in the analysis of the literature; none of these studies were included for PICO 1 and six studies were included for PICO 2. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Aspenberg P. Stimulation of tendon repair: mechanical loading, GDFs and platelets. A mini-review. Int Orthop. 2007 Dec;31(6):783-9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0398-6. Epub 2007 Jun 22. PMID: 17583812; PMCID: PMC2266668.

- Aufwerber S, Heijne A, Edman G, Grävare Silbernagel K, Ackermann PW. Early mobilization does not reduce the risk of deep venous thrombosis after Achilles tendon rupture: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020 Jan;28(1):312-319. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05767-x. Epub 2019 Nov 2. PMID: 31679069; PMCID: PMC6971132.

- Aufwerber S, Heijne A, Edman G, Silbernagel KG, Ackermann PW. Does Early Functional Mobilization Affect Long-Term Outcomes After an Achilles Tendon Rupture? A Randomized Clinical Trial. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020 Mar 16;8(3):2325967120906522. doi: 10.1177/2325967120906522. PMID: 32206673; PMCID: PMC7076581.

- Barfod KW, Nielsen EG, Olsen BH, Vinicoff PG, Troelsen A, Holmich P. Risk of Deep Vein Thrombosis After Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Early Controlled Motion of the Ankle Versus Immobilization. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020 Apr 28;8(4):2325967120915909. doi: 10.1177/2325967120915909. PMID: 32426409; PMCID: PMC7222258.

- Christensen M, Zellers JA, Kjær IL, Silbernagel KG, Rathleff MS. Resistance Exercises in Early Functional Rehabilitation for Achilles Tendon Ruptures Are Poorly Described: A Scoping Review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Dec;50(12):681-690. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.9463. Epub 2020 Oct 23. PMID: 33094667; PMCID: PMC8168134.

- Costa ML, Achten J, Marian IR, Dutton SJ, Lamb SE, Ollivere B, Maredza M, Petrou S, Kearney RS; UKSTAR trial collaborators. Plaster cast versus functional brace for non-surgical treatment of Achilles tendon rupture (UKSTAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. Lancet. 2020 Feb 8;395(10222):441-448. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32942-3. PMID: 32035553; PMCID: PMC7016510.

- Costa ML, Shepstone L, Darrah C, Marshall T, Donell ST. Immediate full-weight-bearing mobilisation for repaired Achilles tendon ruptures: a pilot study. Injury. 2003 Nov;34(11):874-6. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00205-x. PMID: 14580826.

- Costa ML, MacMillan K, Halliday D, Chester R, Shepstone L, Robinson AH, Donell ST. Randomised controlled trials of immediate weight-bearing mobilisation for rupture of the tendo Achillis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006 Jan;88(1):69-77. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B1.16549. PMID: 16365124.

- De la Fuente C, Peña y Lillo R, Carreño G, Marambio H. Prospective randomized clinical trial of aggressive rehabilitation after acute Achilles tendon ruptures repaired with Dresden technique. Foot (Edinb). 2016 Mar;26:15-22. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2015.10.003. Epub 2015 Oct 24. PMID: 26802945.

- de Vos RJ, van der Vlist AC, Zwerver J, Meuffels DE, Smithuis F, van Ingen R, van der Giesen F, Visser E, Balemans A, Pols M, Veen N, den Ouden M, Weir A. Dutch multidisciplinary guideline on Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2021 Oct;55(20):1125-1134. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103867. Epub 2021 Jun 29. PMID: 34187784; PMCID: PMC8479731.

- Eliasson P, Agergaard AS, Couppé C, Svensson R, Hoeffner R, Warming S, Warming N, Holm C, Jensen MH, Krogsgaard M, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP. The Ruptured Achilles Tendon Elongates for 6 Months After Surgical Repair Regardless of Early or Late Weightbearing in Combination With Ankle Mobilization: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2018 Aug;46(10):2492-2502. doi: 10.1177/0363546518781826. Epub 2018 Jul 2. PMID: 29965789.

- Groetelaers RP, Janssen L, van der Velden J, Wieland AW, Amendt AG, Geelen PH, Janzing HM. Functional Treatment or Cast Immobilization After Minimally Invasive Repair of an Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: Prospective, Randomized Trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2014 Aug;35(8):771-778. doi: 10.1177/1071100714536167. Epub 2014 May 21. PMID: 24850161.

- Kauranen K, Kangas J, Leppilahti J. Recovering motor performance of the foot after Achilles rupture repair: a randomized clinical study about early functional treatment vs. early immobilization of Achilles tendon in tension. Foot Ankle Int. 2002 Jul;23(7):600-5. doi: 10.1177/107110070202300703. PMID: 12146769.

- Kangas J, Pajala A, Siira P, Hämäläinen M, Leppilahti J. Early functional treatment versus early immobilization in tension of the musculotendinous unit after Achilles rupture repair: a prospective, randomized, clinical study. J Trauma. 2003 Jun;54(6):1171-80; discussion 1180-1. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000047945.20863.A2. PMID: 12813340.

- Kastoft R, Barfod K, Bencke J, Speedtsberg MB, Hansen SB, Penny JØ. 1.7 cm elongated Achilles tendon did not alter walking gait kinematics 4.5 years after non-surgical treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022 Mar 2. doi: 10.1007/s00167-022-06874-y. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35234975.

- Korkmaz M, Erkoc MF, Yolcu S, Balbaloglu O, Öztemur Z, Karaaslan F. Weight bearing the same day versus non-weight bearing for 4 weeks in Achilles tendon rupture. J Orthop Sci. 2015 May;20(3):513-6. doi: 10.1007/s00776-015-0710-z. Epub 2015 Mar 14. PMID: 25773309.

- Lantto I, Heikkinen J, Flinkkila T, Ohtonen P, Siira P, Laine V, Leppilahti J. A Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Surgical and Nonsurgical Treatments of Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Sep;44(9):2406-14. doi: 10.1177/0363546516651060. Epub 2016 Jun 15. PMID: 27307495.

- Martin RL, Chimenti R, Cuddeford T, Houck J, Matheson JW, McDonough CM, Paulseth S, Wukich DK, Carcia CR. Achilles Pain, Stiffness, and Muscle Power Deficits: Midportion Achilles Tendinopathy Revision 2018. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018 May;48(5):A1-A38. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.0302. PMID: 29712543.

- Maempel JF, Clement ND, Duckworth AD, Keenan OJF, White TO, Biant LC. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Traditional Plaster Cast Rehabilitation With Functional Walking Boot Rehabilitation for Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 2020 Sep;48(11):2755-2764. doi: 10.1177/0363546520944905. Epub 2020 Aug 20. PMID: 32816521.