Glykemische controle

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van glykemische controle bij chirurgische patiënten ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties?1

Disclaimer: Dit is een adaptatie van een origineel werk ‘Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.’ (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475). Deze adaptatie is niet uitgevoerd door de WHO. De WHO is niet verantwoordelijk voor de inhoud of nauwkeurigheid van deze adaptatie. De originele uitgave is de bindende en authentieke uitgave.

1 De WHO-richtlijn beschrijft geen uitgangsvragen. De uitgangsvragen voor deze module zijn opgesteld in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het gebruik van een matig intensief perioperatief* bloedglucosecontrole protocol voor zowel diabetische als niet-diabetische volwassen patiënten die chirurgische procedures ondergaan om het risico op postoperatieve wondinfecties te verminderen [WHO 2018].

Hanteer de streefwaarden van 6-10 mmol/l zoals in de richtlijn Diabetes mellitus (NIV).

Overweeg ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties een striktere glucose regulatie van 6,1-8,3 mmol/L maar wees bewust van een kans op hypoglykemieën. [de novo].

*Perioperatief heeft betrekking op de intra-operatieve periode en postoperatieve fase gedurende het verblijf op de verkoever, IC of PACU.

Disclaimer: This is an adaptation of an original work “Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.” (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475). This adaptation was not created by WHO. WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this adaptation. The original edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van een strikter perioperatief protocol ter controle van de bloedsuikerspiegel in vergelijking met een conventioneel protocol bij diabetische en niet-diabetische patiënten die chirurgische procedures ondergaan. Postoperatieve wondinfecties werden als cruciale uitkomstmaat gedefinieerd. Een verschil van 10% voor continue uitkomstmaten, een verschil in relatief risico kleiner 0.95 of groter dan 1.05 voor infectie-gerelateerde mortaliteit en een relatief risico kleiner dan 0.80 of groter dan 1.25 tussen beide interventies voor overige dichotome uitkomstmaten werden als klinisch relevant verschillend beschouwd.

Er werden vijftien studies geïncludeerd in de literatuuranalyse. Op basis van de literatuur lijkt het gebruik van een strikt perioperatief protocol ter controle van de bloedsuikerspiegel de kans op het verkrijgen van postoperatieve wondinfecties te reduceren (RR 0.47; 95% BI 0.33 tot 0.67). De bewijskracht werd gegradeerd als ‘laag’ vanwege het gebrek aan blindering (met name van de beoordelaars van de uitkomsten) en vanwege het indirecte bewijs. Het bewijs werd als indirect beoordeeld omdat veel van de geïncludeerde studies patiënten onderzochten die waren opgenomen op de intensive care afdeling. Hierdoor is de bewijskracht met twee niveaus afgewaardeerd.

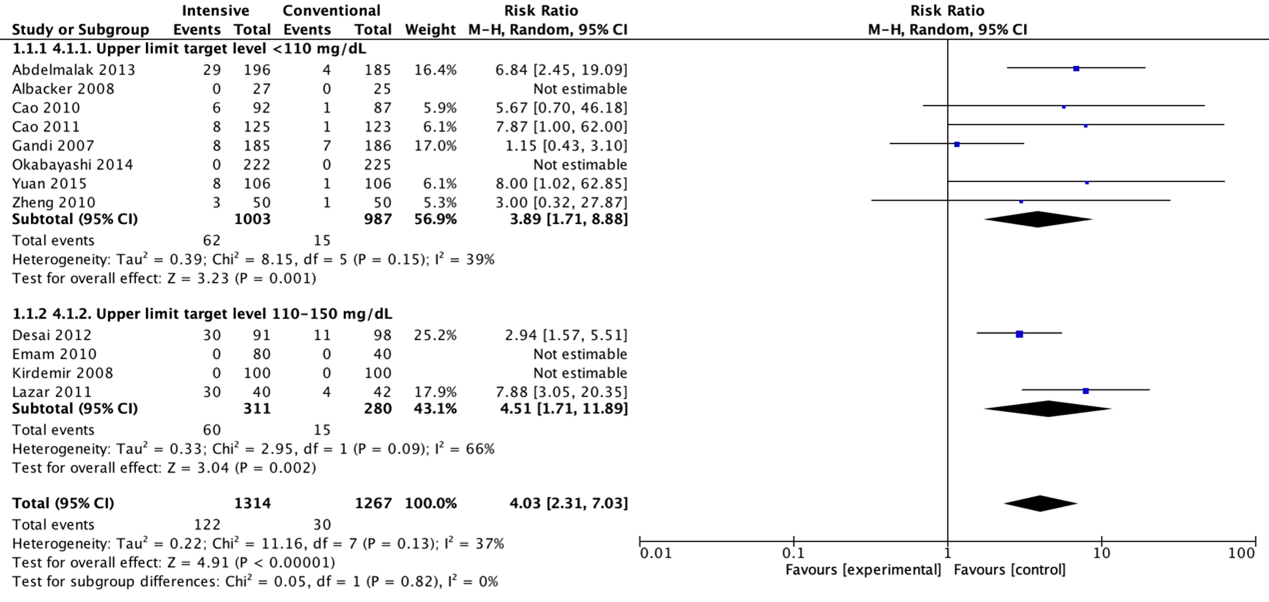

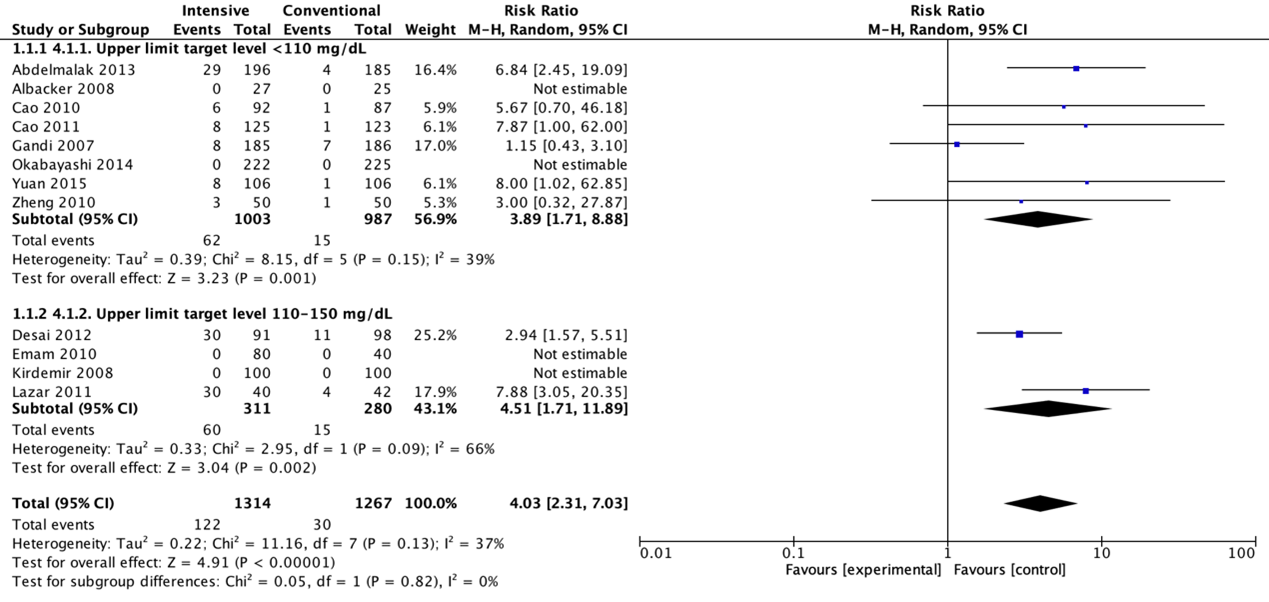

In een meta-analyse van acht studies, waarin protocol een grens van het bloedsuikerspiegelniveau van minder dan 110 mg/dl hanteerde, liet een voordeel zien in het voordeel van een strikter protocol (RR 0.53; 95% BI 0.38 tot 0.75). Dit gold eveneens in zeven studies bij patiënten met een bloedsuikerspiegel niveau tussen de 110-150 mg/dl (RR 0.31; 95% BI 0.11 tot 0.85). De resultaten lieten een klein klinisch relevant verschil zien tussen beide interventies voor wondinfectie-gerelateerde mortaliteit.

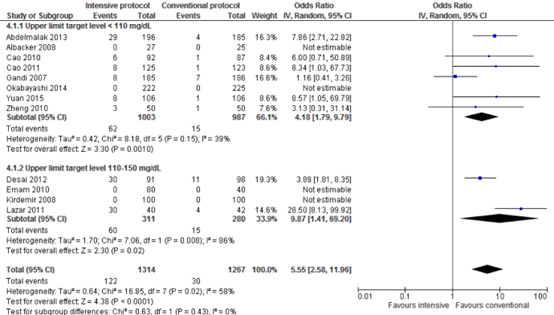

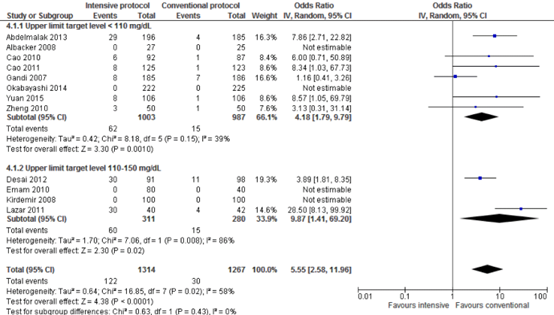

In een meta-analyse van vijftien studies, waarin een intensiever protocol ter controle van de bloedsuikerspiegel werd vergeleken met een conventioneel protocol en de relatie tot wondinfecties, werd een significant en klinisch relevant verschil gevonden in het voordeel van de intensievere protocollen ter voorkoming van wondinfecties (OR 0.43 (95% CI 0.29 tot 0.64) (de Vries, 2016). Er werd echter een groter risico gevonden op hypoglykemie gevonden voor een zeer strikt protocol met een glucose bovengrens van 6.1 mmol/l (OR 5.55 (95% CI 2.58 tot 11.96) vergeleken met een matig strikt protocol met een bovengrens tussen 6.1 en 8.3 mmol/l. Deze resultaten waren consistent in zowel patiënten met diabetes als patiënten zonder diabetes en in studies met een redelijk strikt als zeer strikt protocol ter controle van de bloedsuikerspiegel. Patiënten die ‘at risk’ zijn voor schommelingen in de glucoseniveaus komen er mogelijk voor in aanmerking gecontroleerd te worden. De aard en de ingreep zijn hierin bepalend.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Er zijn geen onderzoeken bekend naar de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten met betrekking tot deze interventie. De werkgroep is ervan overtuigd dat de meeste patiënten deze interventie prefereren om het risico op SSI te verminderen. Patiënten maken zich zorgen over het optreden van hypoglykemische incidenten en over het feit dat ze regelmatig (soms een paar keer per dag) worden gecontroleerd op de streefwaarde voor bloedglucose, wat gepaard zou kunnen gaan met frequente naaldprikken. Het is belangrijk om samen met de patiënt de voor- en nadelen van de voorgestelde interventie zorgvuldig te overwegen. Open communicatie en het bespreken van eventuele zorgen geven ruimte om een behandeling op maat te bieden die aansluit bij de individuele behoeften en voorkeuren van de patiënt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Op de intensive care setting na krijgen patiënten eerder een conventioneel protocol of geen bloedglucosecontroles als patiënten geen diabetes mellitus hebben, vanwege zorgen over de middelen en de mogelijkheden om de bloedglucose adequaat te controleren. De aankoop en opslag (koelkast) van insuline is een financiële last voor lage- en middeninkomenslanden en daarnaast kan de beschikbaarheid van insuline tegenwoordig ook in Europa een probleem zijn. De apparatuur voor de toepassing van frequente glucosecontrole is kostbaar en kan beperkt beschikbaar zijn, als alle patiënten bloedglucosecontroles ondergaan. Bovendien moet het medisch personeel zorgvuldig worden opgeleid om het bloedglucosegehalte correct te controleren en hypoglykemieën te behandelen. Er zijn geen gegevens beschikbaar om de kosteneffectiviteit van verschillende protocollen te bepalen. Praktisch navragen leert wel dat moderne bloedglucosecontroles twee tot drie minuten per patiënt kosten. Die tijd kan niet ook voor andere handelingen worden gebruikt.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Tot op heden zijn er geen studies verricht die aantonen dat strikte bloedglucosecontrole bij algemeen chirurgische (dus niet IC) patiënten leidt tot een daling van mortaliteit en morbiditeit (Feingold, 2020). De studies waarop deze richtlijn zich baseert vonden vooral in intensive care of op de verkoever plaats. In deze settingen lijkt strikte bloedglucosecontrole een meerwaarde te hebben in het voorkomen van SSIs, en ook uitvoerbaar te zijn. Vanuit de Endocrine Society en de Joint British Diabetes Society for Inpatient Care bestaan er richtlijnen voor glucosecontrole op de verpleegafdelingen. De lage waarden die in deze richtlijnen worden nagestreefd blijken in de praktijk moeilijk haalbaar, zelfs bij een hoge personeel – patiënt ratio, zonder relatief risico op ernstige hypoglykemie te induceren (NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators, 2009). In verschillende trials varieerde het optreden van ernstige hypoglykemie (< 2,2 mmol/l) op de intensive care van 5 tot 28% (Krikorian, 2010). Het is niet onredelijk om te verwachten dat dit vaker zal gebeuren op chirurgische verpleegafdelingen, waar het aantal verpleegkundigen per patiënt lager is. In hoeverre strikte bloedglucosecontrole dan ook haalbaar is op chirurgische verpleegafdelingen, waar de personeel – patiënt ratio veel lager is dan op een verkoever of intensive care, is dan ook onduidelijk, en kan op basis van deze richtlijn niet geadviseerd worden.

Duurzaamheid

Duurzaamheid is niet benoemd in de WHO-richtlijn en er is niet aanvullend naar gezocht.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De resultaten lieten een klein klinisch relevant verschil zien tussen beide interventies voor wondinfectie-gerelateerde mortaliteit ten voordele van strikte perioperatieve bloedglucosecontrole.Hoewel er diverse richtlijnen zijn die glycaemische controle beschrijven wordt er niet eenduidig geadviseerd (Dogra, 2024)”.

Het beschikbare bewijsmateriaal bestaat voornamelijk uit populaties die verblijven op de intensive care, waar de personeel – patiënt ratio relatief hoog is. Er is behoefte aan onderzoeken naar strikte perioperatieve glucosecontrole bij (niet-ICU) chirurgische patiënten, bij verschillende soorten chirurgische procedures ondergaan, en aan onderzoek bij kinderen die geopereerd worden. Tevens is er behoefte aan gerandomiseerd onderzoek waarin verschillende streefwaarden voor bloedglucose uiteen worden gezet om beter te kunnen bepalen wat het optimale bloedglucoseniveau is voor de preventie van SSI met een zo klein mogelijk risico op hypoglykemie. Voor het bepalen van het streefniveau zijn studies nodig die de optimale route voor insulinetoediening onderzoeken, evenals studies naar de duur van continue postoperatieve glucosecontrole. Er is tevens behoefte naar het onderzoeken van kosteneffectiviteit en efficiëntie. Omwille van deze kennisgebreken, en een relatief grote kans op iatrogeen geïnduceerde hypoglykemie wordt geadviseerd om te overwegen een intensief perioperatief bloedglucoseprotocol te gebruiken om het risico op postoperatieve wondinfecties te verminderen, zolang patiënt op de verkoever of op de intensive care verblijft.

Disclaimer: This is an adaptation of an original work “Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.” (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475). This adaptation was not created by WHO. WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this adaptation. The original edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De bloedsuikerspiegel stijgt tijdens en na een operatie door stress. Chirurgie veroorzaakt een stressreactie die leidt tot het vrijkomen van katabole hormonen en het afremmen van insuline. Bovendien beïnvloedt chirurgische stress de bètacelfunctie van de alvleesklier, wat resulteert in lagere plasma-insulinespiegels. Samen zorgen deze relatieve hyperinsulinemie, insulineresistentie en overmatig katabolisme door de werking van contra-regulerende hormonen ervoor dat chirurgische patiënten, zowel diabetici als niet-diabetici, een hoog risico lopen op hyperglykemische ontregeling (McAnulty, 2000). Verschillende observationele onderzoeken (Ata, 2010; Kao, 2013; Kotagal, 2015; Richards, 2014) toonden aan dat hyperglykemie geassocieerd is met een verhoogd risico op postoperatieve wondinfecties (POWI/SSI). Glykemische ontregeling is daarmee, bij zowel diabetici als niet-diabetische patiënten, geassocieerd met een verhoogd risico op morbiditeit, mortaliteit en hogere kosten voor de gezondheidszorg.

Er zijn tegenstrijdige resultaten gerapporteerd met betrekking tot de verschillende behandelingsopties ten aanzien van hyperglykemiëen, de optimale streefwaarden voor bloedglucose en de ideale timing voor glucosecontrole (intra- en/of postoperatief) bij diabetische en niet-diabetische patiënten. Bovendien hebben sommige onderzoeken, die zich richten op relatief lage perioperatieve glucosespiegels, gewezen op het risico van nadelige effecten van intensieve protocollen, omdat ze hypoglykemie kunnen veroorzaken (Blondet, 2007; Buchleitner, 2012; Griesdale, 2009; Kao, 2009). In deze module is onderzocht wat de waarde is van glykemische controle bij chirurgische patiënten ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties.

Deze module betreft een adaptatie van de module ‘Use of protocols for intensive perioperative blood glucose control’ van de WHO-richtlijn ‘Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection’ (2018). Voor een toelichting op de procedure van adapteren wordt verwezen naar de Bijlage Adapteren.

Disclaimer: This is an adaptation of an original work “Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.” (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475). This adaptation was not created by WHO. WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this adaptation. The original edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.

Conclusies

1. Surgical site infections1

|

Low GRADE |

The effect on SSI prevention of protocols for very strict perioperative blood glucose control have comparable results to protocols with moderate strict blood glucose target levels in diabetic and non-diabetic adult patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Sources: Abdelmalak (2013); Albacker (2008); Bilotta (2007); Cao (2010); Cao (2011); Chan (2009); Desai (2012); Emam (2010); Gandhi (2007); Grey (2004); Kirdemir (2008); Lazar (2011); Okabayashi (2014); Yuan (2015); Zheng (2010). |

2. SSI-attributable mortality1

|

Low GRADE |

Use of protocols for intensive perioperative blood glucose control may result in less SSI-attributable mortality when compared with conventional protocols with less stringent blood glucose target levels in diabetic and non-diabetic adult patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Sources: Abdelmalak (2013); Albacker (2008); Bilotta (2007); Cao (2010); Cao (2011); Chan (2009); Desai (2012); Gandhi (2007); Grey (2004); Kirdemir (2008); Lazar (2011); Yuan (2015); Zheng (2010). |

3. Adverse events1

3.1 Hypoglycaemic events

|

Low GRADE |

Use of protocols for very strict perioperative blood glucose control (upper limit 110 mg/dl) may result in more hypoglycaemic events when compared with moderately strict glucose control protocols (upper limit 110-150 mg/dl) in diabetic and non-diabetic adult patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Sources: Abdelmalak (2013); Albacker (2008); Bilotta (2007); Cao (2010); Cao (2011); Chan (2009); Desai (2012); Gandhi (2007); Grey (2004); Kirdemir (2008); Lazar (2011); Yuan (2015); Zheng (2010). |

3.2 Postoperative strokes

|

Very low GRADE |

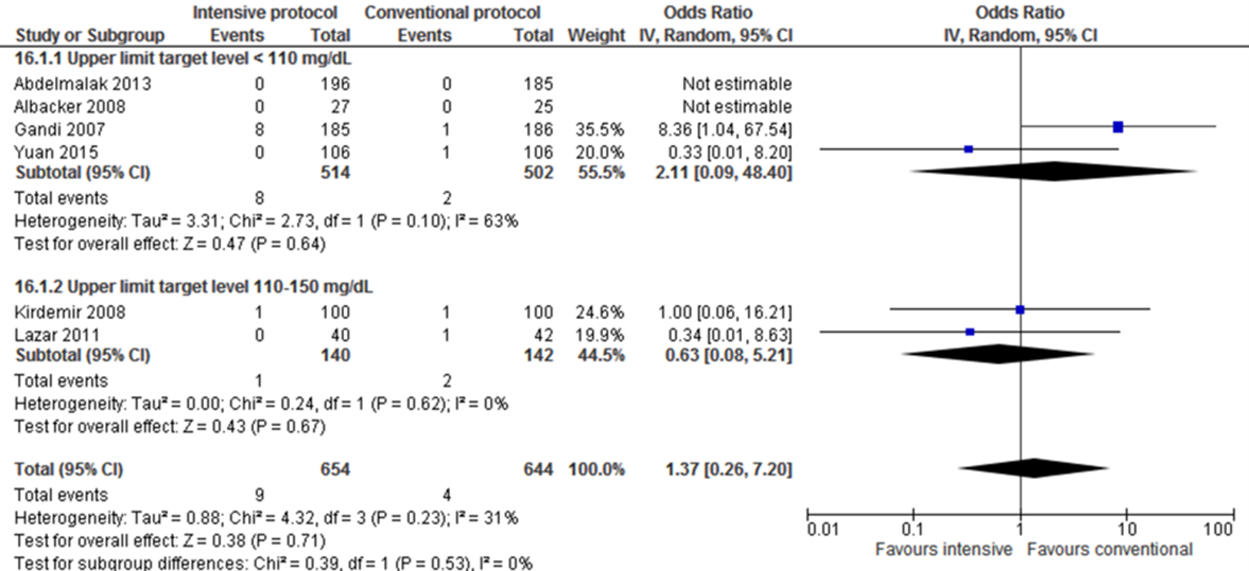

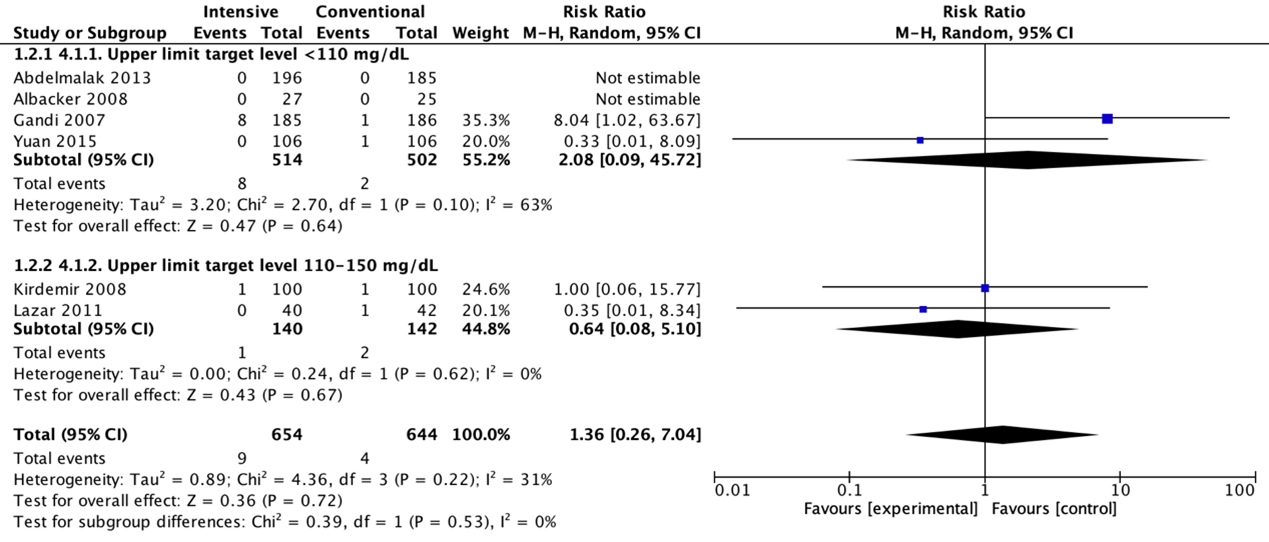

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of protocols for very strict perioperative blood glucose control (upper limit 110 mg/dl) for postoperative strokes when compared with moderately strict glucose control protocols (upper limit 110-150 mg/dl) in diabetic and non-diabetic adult patients undergoing surgical procedures.

Sources: Abdelmalak (2013); Alback (2008); Gandi (2007); Yuan (2015); Kirdemir (2008); Lazar (2011). |

Disclaimer: This is an adaptation of an original work “Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.” (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475). This adaptation was not created by WHO. WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this adaptation. The original edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.

1 The conclusions of the literature analysis were formulated in accordance with the standard procedures of the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

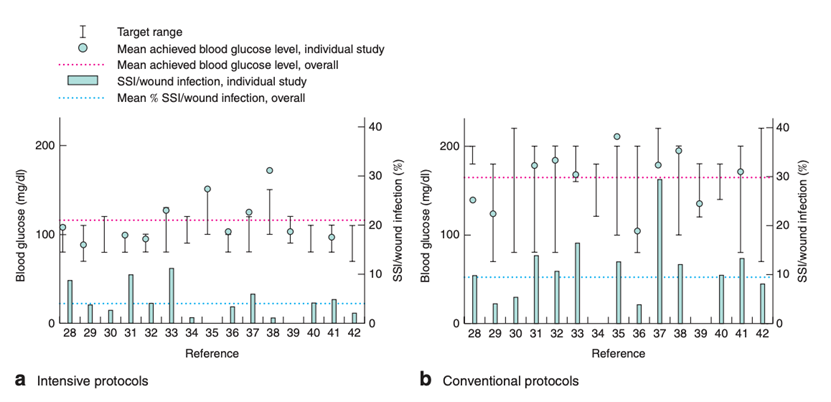

The purpose of the evidence review was to evaluate whether the use of protocols for intensive perioperative blood glucose control is more effective in reducing the risk of SSI than conventional protocols with less stringent blood glucose target levels. The population studied were patients of all ages, both diabetic and non-diabetic, and undergoing several types of surgical procedures. The primary outcome was the occurrence of SSI and SSI-attributable mortality. A total of fifteen RCTs (Abdelmalak, 2013; Albacker, 2008; Bilotta, 2007; Cao, 2010; Cao, 2011; Chan, 2009; Desai, 2012; Emam, 2010; Gandhi, 2007; Grey, 2004; Kirdemir, 2008; Lazar, 2011; Okabayashi, 2014; Yuan, 2015; Zheng, 2010) including a total of 2836 patients and comparing intensive perioperative blood glucose protocols vs. conventional protocols with less stringent blood glucose target levels were identified. Eight studies were performed in adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery (Emam, 2010; Kirdemir, 2008; Albacker, 2008; Lazar, 2011; Chan, 2009; Gandhi, 2007; Zheng, 2010), six in patients undergoing abdominal or major non-cardiac surgery (Yuan, 2015; Cao, 2011; Abdelmalak, 2013; Grey, 2004; Okabayashi, 2014; Cao, 2011), and one other study in patients undergoing emergency cerebral aneurysm clipping (Bilotta, 2007). No study was available in a paediatric population. In two studies (Albacker, 2008; Abdelmalak, 2013), glucose control was performed intraoperatively only. Eight studies (Emam, 2010; Kirdemir, 2008; Lazar, 2011; Bilotta, 2007; Chan, 2009; Gandhi, 2007; Okabayashi, 2014; Zheng, 2010) investigated intra- and postoperative glucose control and five studies (Yuan, 2015; Cao, 2011; Desai, 2012; Grey, 2004; Cao, 2011) focused on postoperative glucose control. None of the studies had SSI as their primary outcome. Most studies had a combined outcome of postoperative complications. The definition of SSI was also different in most studies. There was substantial heterogeneity among the selected studies in the population, notably regarding the timing when intensive blood glucose protocols were applied in the perioperative period and intensive blood glucose target levels. For this reason, separate meta-analyses were performed to evaluate intensive protocols vs. conventional protocols in different settings (that is, in diabetic, non-diabetic and a mixed population) with intraoperative, intra- and postoperative glucose control, and in trials with intensive blood glucose upper limit target levels of ≤110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L) and 110-150 mg/dL (6.1-8.3 mmol/L).

Results

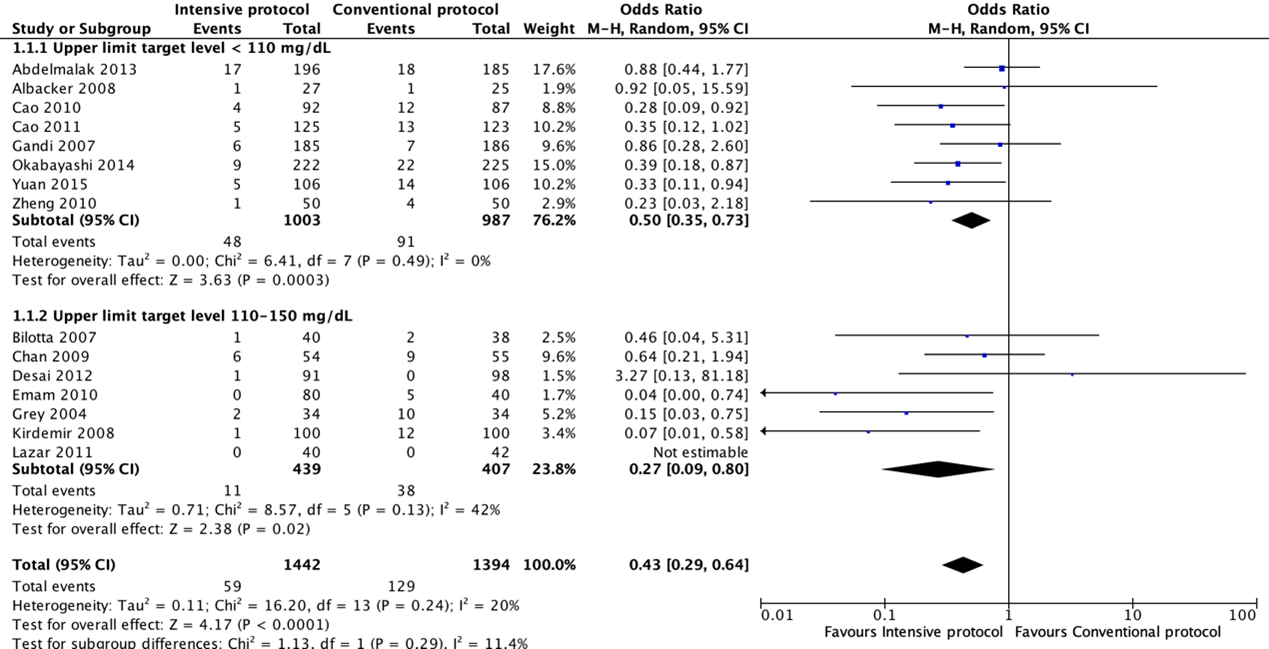

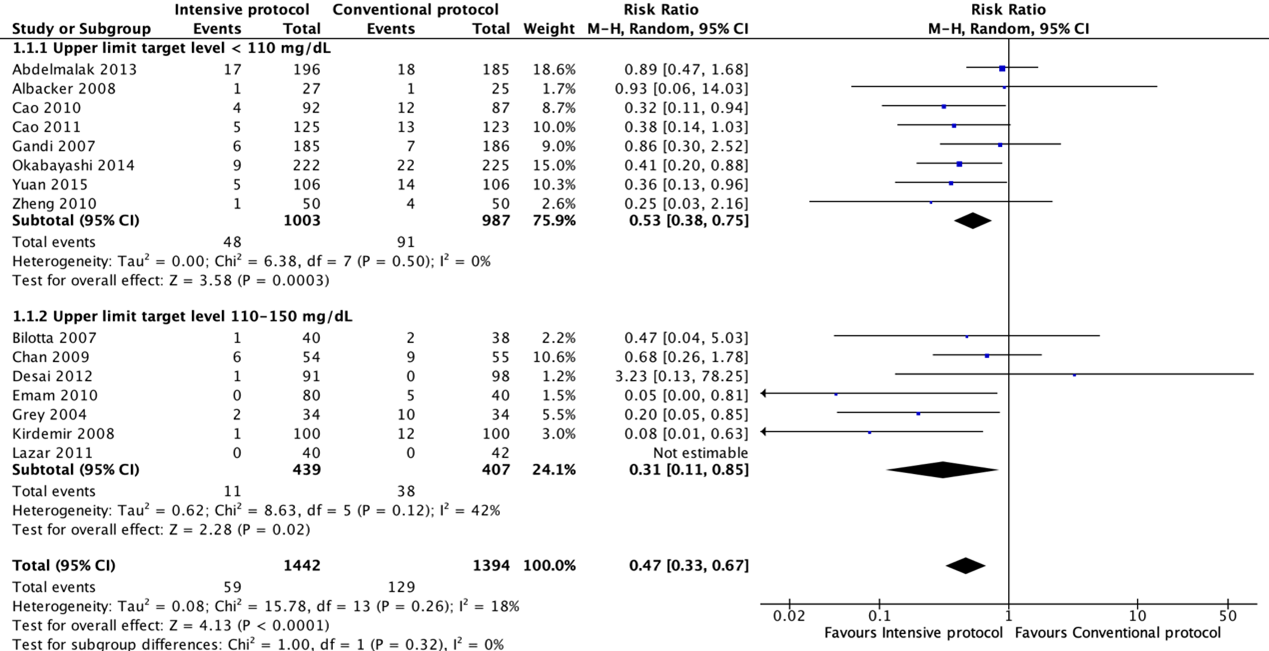

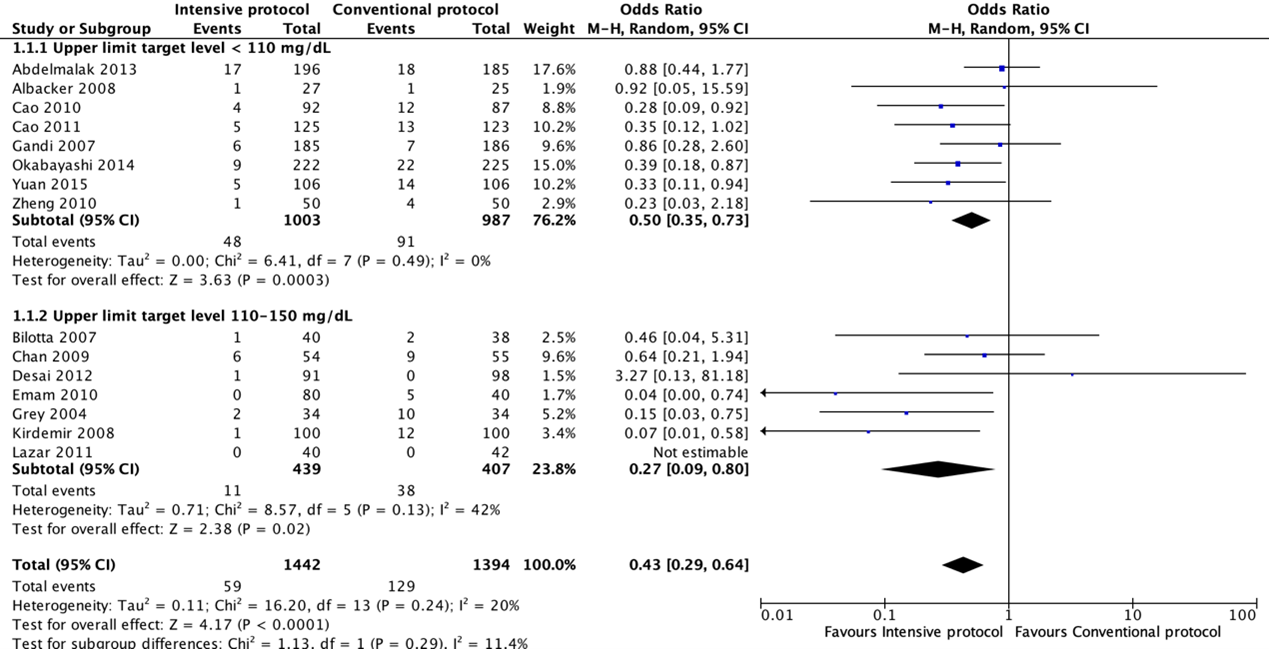

1. Surgical site infections

Fifteen RCTs compared an intensive with a conventional protocol. The meta-analysis, which included 1442 patients in the intensive group and 1394 in the control group, showed a significant benefit for intensive compared with a conventional protocol in reducing SSI (pooled odds ratio (OR) 0.43; 95% CI 0.29 to 0.64; pooled relative risk ratio (RR) 0.47; 95% CI 0.33 to 0.67). Meta-analysis of eight studies with a blood glucose target level of less than 110 mg/dl (6.1 mmol/l) in the intensive group showed a significant benefit for an intensive protocol (pooled OR 0.50; 95% CI 0.35 to 0.73; pooled RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.75) and seven studies with a blood glucose target level of 110–150 mg/dl (6.1–8.3 mmol/l) showed similar effects (pooled OR 0.27 ; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.78; pooled RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.11 to 0.85). In meta-regression analyses, there was no evidence that the effect of intensive blood glucose control differed between studies including patients with or without diabetes. There was some evidence that the effect was smaller in studies that used intensive blood glucose control during surgery only (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.74), compared with studies that used intensive blood glucose control after surgery or both during and after operation (OR 0.37; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.55). This comparison was similar in studies with very strict and moderately strict glucose control.

Forest plot showing the comparison between intensive perioperative blood glucose control to conventional protocols for surgical site infections. Pooled odds-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Forest plot showing the comparison between wound protector devices to conventional wound protection for surgical site infections. Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

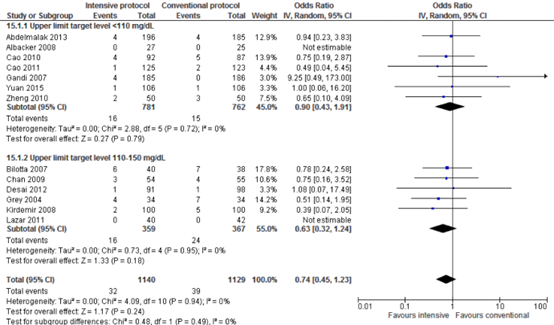

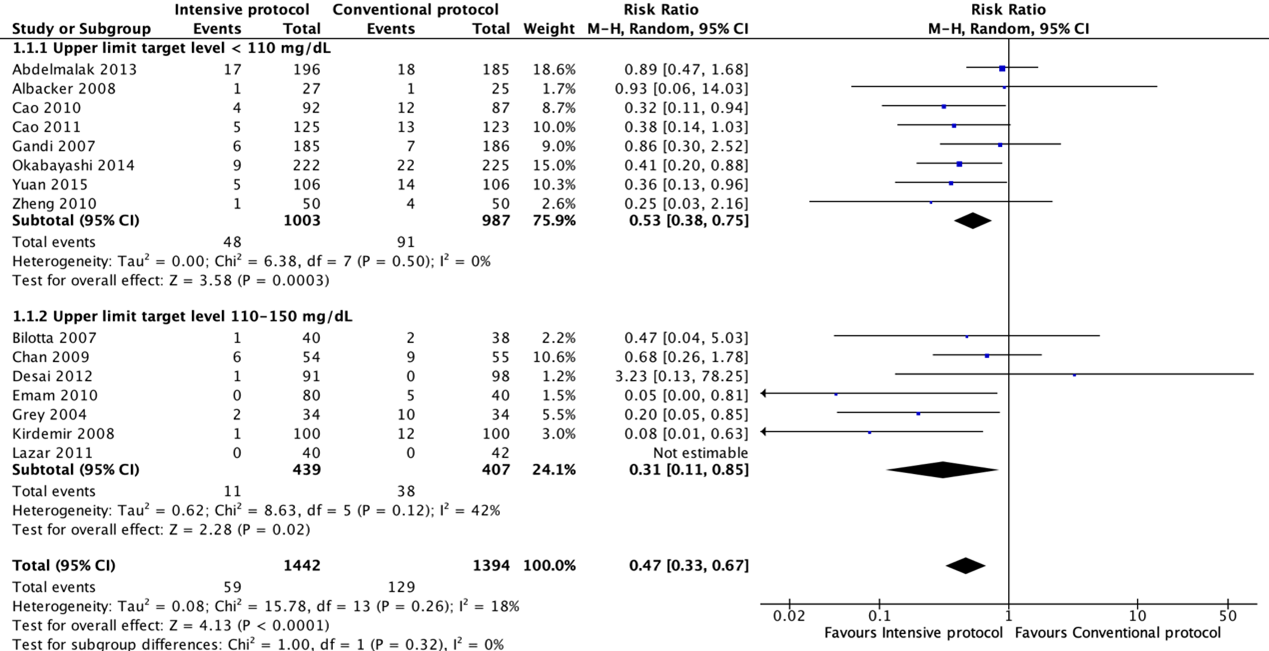

2. SSI-attributable mortality

Meta-analyses of postoperative death showed no significant differences between intensive and conventional protocols (pooled OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.23; pooled RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.20).

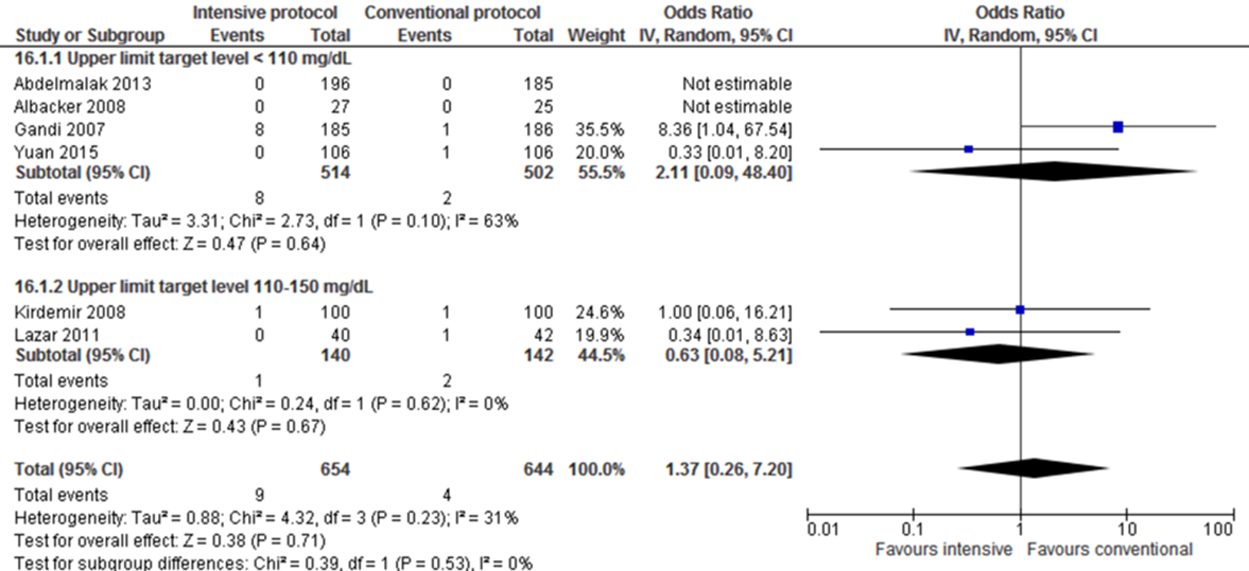

Forest plot showing the comparison between intensive perioperative blood glucose control to conventional protocols for SSI-attributable mortality. Pooled odds-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

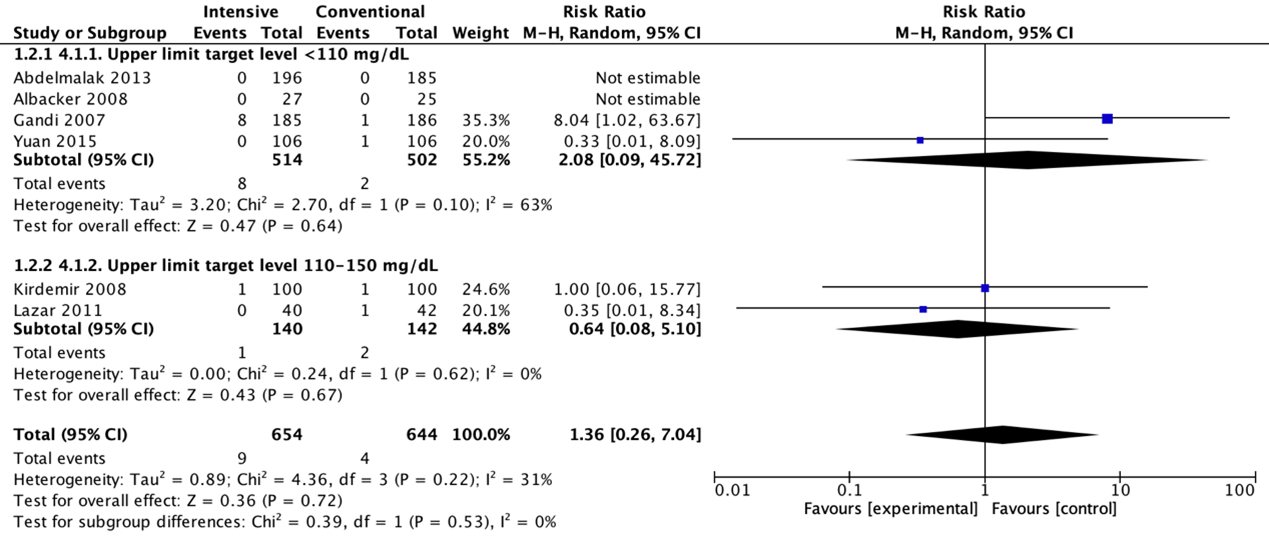

Forest plot showing the comparison between intensive perioperative blood glucose control to conventional protocols for SSI-attributable mortality. Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

3. Adverse events

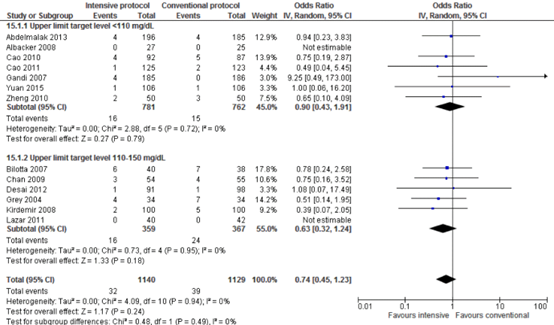

3.1 Hypoglycaemic events

Meta-analyses of hypoglycaemic events in the eight trials with a blood glucose upper limit target level lower than 110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L) showed significant harm of intensive protocols in comparison with conventional protocols (pooled OR 4.18 (95% CI 1.79 to 9.79; pooled RR 3.89 (95% CI 1.71 to 8.88)). Meta-analyses of hypoglycaemic events in the four trials with a blood glucose upper limit target level between 110 and 150 mg/dL (6.1 and 8.3 mmol/L) showed significant harm of intensive protocols in comparison with conventional protocols (pooled OR 9.87 (95% CI 1.41 to 60.20; pooled RR 4.51 (95% CI 1.71 to 11.89)).

Forest plot showing the comparison between intensive perioperative blood glucose control to conventional protocols for hypoglycaemic events for upper limit target level <110 mg/dL and upper limit target level 110-150 mg/dL. Pooled odds-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Forest plot showing the comparison between intensive perioperative blood glucose control to conventional protocols for hypoglycaemic events for upper limit target level <110 mg/dL and upper limit target level 110-150 mg/dL. Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

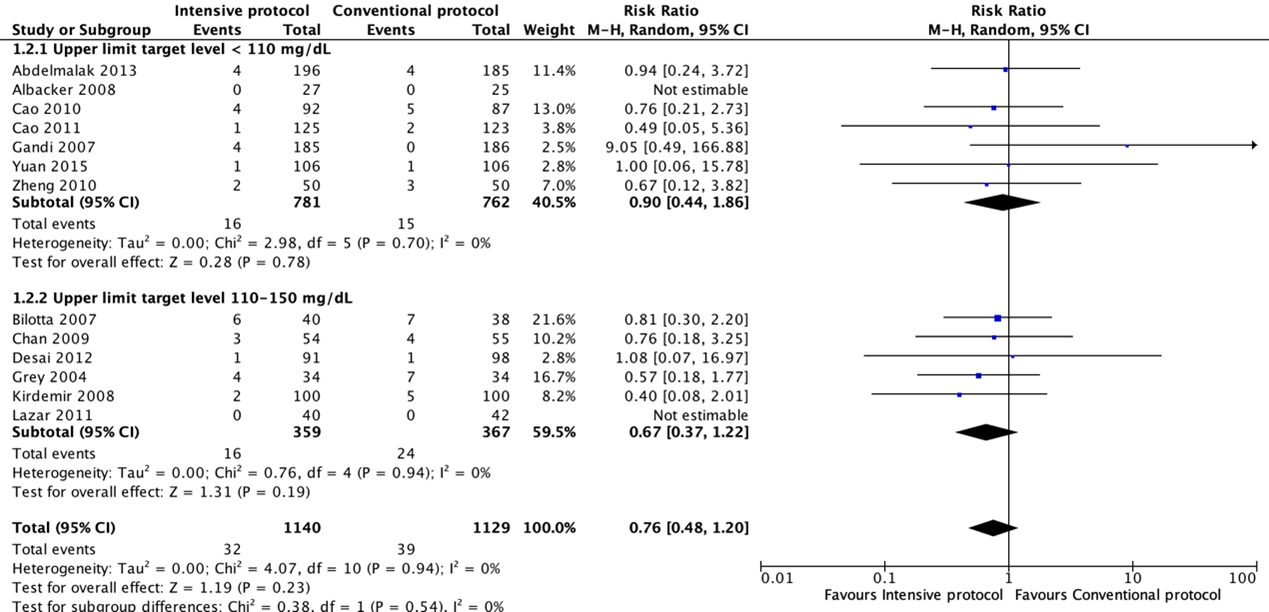

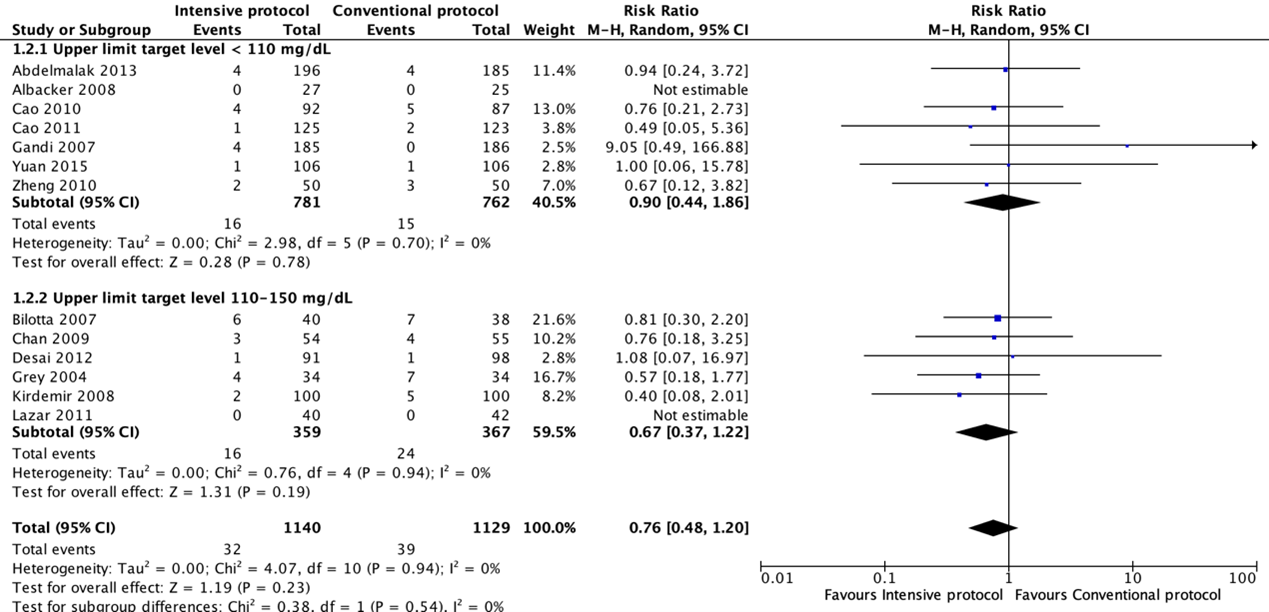

3.2 Postoperative strokes

Meta-analyses of postoperative strokes in the four trials with a blood glucose upper limit target level lower than 110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L) did not show a significant difference for intensive protocols in comparison with conventional protocols (pooled OR 2.11 (95% CI 0.09 to 48.40; pooled RR 2.08 (95% CI 0.09 to 45.72)).

Meta-analyses of postoperative strokes in the two trials with a blood glucose upper limit target level between 110 and 150 mg/dL (6.1 and 8.3 mmol/L) did not show a significant difference for intensive protocols in comparison with conventional protocols (pooled OR 0.63 (95% CI 0.08 to 5.21; pooled RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.08 to 5.10)).

Forest plot showing the comparison between intensive perioperative blood glucose control to conventional protocols for postoperative strokes for upper limit target level <110 mg/dL and upper limit target level 110-150 mg/dL. Pooled odds-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Forest plot showing the comparison between intensive perioperative blood glucose control to conventional protocols for postoperative strokes for upper limit target level <110 mg/dL and upper limit target level 110-150 mg/dL. Pooled risk-ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Level of evidence of the literature1

1. Surgical site infections

The level of evidence regarding the outcome surgical site infections was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding (especially outcome assessors) in the studies (risk of bias, -1) and because most included studies investigated patients in an ICU setting (indirectness, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low (GRADE Table).

2. SSI-attributable mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome SSI-attributable mortality was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding (especially outcome assessors) in the studies (risk of bias, -1) and because most included studies investigated patients in an ICU setting (indirectness, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low (GRADE Table).

3. Adverse events

3.1 Hypoglycaemic events

The level of evidence regarding the outcome hypoglycaemic events was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of a lack of blinding (especially outcome assessors) in the studies (risk of bias, -1) and because most included studies investigated patients in an ICU setting (indirectness, -1). The level of evidence was considered as low (GRADE Table).

3.2 Postoperative strokes

The level of evidence regarding the outcome postoperative strokes was derived from randomized controlled trials and therefore started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of a lack of blinding (especially outcome assessors) in the studies (risk of bias, -1), because most included studies investigated patients in an ICU setting (indirectness, -1), and the wide confidence interval crossing both thresholds of clinical relevance (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence was considered as very low (GRADE Table).

Disclaimer: This is an adaptation of an original work “Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.” (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475). This adaptation was not created by WHO. WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this adaptation. The original edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.

1 The WHO-guideline did not provide the level of evidence and did not formulate GRADE-conclusions for the effect of intensive perioperative blood glucose control protocols compared to conventional protocols in diabetic and non-diabetic adult patients undergoing surgical procedures for the outcome SSI-attributable mortality. The GRADE-conclusions for this module were prepared in accordance with the standard procedures of the Knowledge Institute of the Federation of Medical Specialists.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)beneficial effects of the use of protocols for intensive perioperative blood glucose control on the incidence of surgical site infections (SSI) and SSI-attributable mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic adult patients undergoing surgical procedures?1

P: Diabetic and non-diabetic adult patients undergoing surgical procedures.

I: Use of protocols for intensive perioperative blood glucose control.

C: Conventional protocols with less stringent blood glucose target levels.

O: Surgical site infections (SSI), SSI-attributable mortality.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered surgical site infections as a critical outcome for decision making; and SSI-attributable mortality as an important outcome for decision making.2

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes, a relative risk ratio (RR) of <0.95 and >1.05 for SSI-attributable mortality, and a RR of <0.80 and >1.25 for other dichotomous as minimal clinically (patient) important differences.

Search and select (Methods)

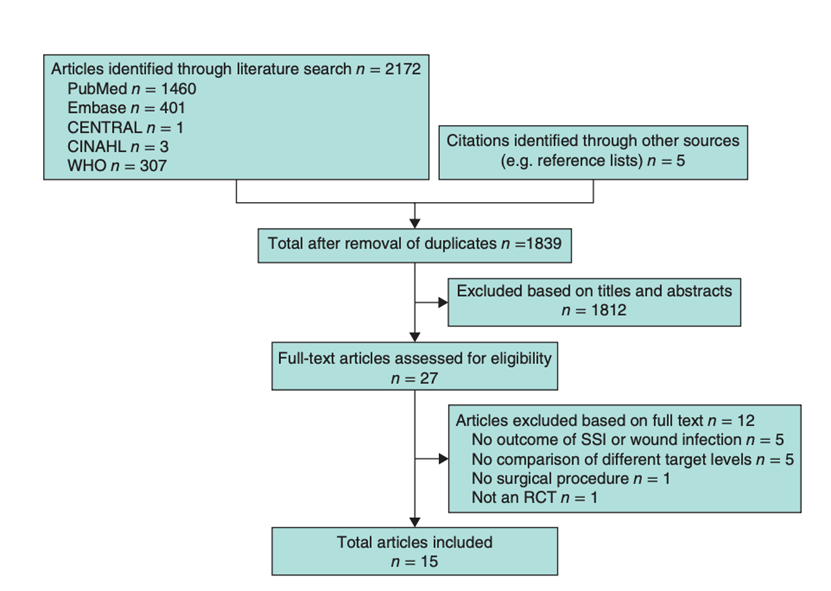

The WHO searched the following databases: PubMed, Embase (Ovid), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and WHO global and regional databases. The time limit for the review was between January 1990 and August 2015. Studies before 1990 were not included as there have been continual changes in healthcare practices and older studies would confound conclusions. Language was restricted to English, French and Spanish. Two authors independently screened all titles and abstracts. RCTs comparing a perioperative intensive glucose protocol (with stricter and lower blood glucose target levels) with a conventional glucose protocol (with more liberal and higher blood glucose target levels) in adult patients were included. The primary outcome was SSI (or wound infection). Secondary outcomes were hypoglycaemic events (both laboratory results or clinically relevant), stroke and mortality. Studies comparing different protocols or a different route of administration with comparable blood glucose target levels were excluded. References of the included studies were screened for other relevant studies. The search strategy is available under the "evidence tabellen" tab.

The WHO systematic literature search resulted in 1839 hits. Twenty-seven studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, twelve studies were excluded (Study selection) and fifteen randomized controlled trials were included. The two authors extracted data in a predefined evidence table (Evidence table) and critically appraised the retrieved studies. Quality was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool to assess the risk of bias of randomized controlled studies (RCTs). Meta-analyses of available comparisons were performed using Review Manager version 5.3 as appropriate (Comparisons). For meta-analyses, studies in the intensive group were divided into studies with a very strict glucose control (upper limit target level less than 110 mg/dl (6.1 mmol/l)) and studies with a moderately strict glucose control (upper limit target level 110–150 mg/dl (6.1–8.3 mmol/l)). The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology (GRADE Pro software) was used to assess the quality of the body of retrieved evidence. In addition to the WHO meta-analyses, relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted and pooled with a random effects model and added to the current literature analysis.3

Results

Fifteen studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Summary of literature). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables (Evidence table). The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables (Risk of bias assessment of the included studies).

Disclaimer: This is an adaptation of an original work “Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.” (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475). This adaptation was not created by WHO. WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this adaptation. The original edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.

1 The working group modified the WHO-search question by including all WHO-defined outcomes.

2 The WHO-guideline did not distinguish between crucial and important outcome measures and did not define thresholds for clinical decision making.

3 The WHO-guideline did not report risk ratios and risk differences.

Referenties

- Abdelmalak BB, Bonilla A, Mascha EJ, Maheshwari A, Tang WH, You J, et al. Dexamethasone, light anaesthesia, and tight glucose control (DeLiT) randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesthes. 2013;111(2):209-21.

- Albacker T, Carvalho G, Schricker T, Lachapelle K. High-dose insulin therapy attenuates systemic inflammatory response in coronary artery bypass grafting patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(1):20-7.Ata A, Lee J, Bestle SL, Desemone J, Stain SC. Postoperative hyperglycemia and surgical site infection in general surgery patients. Arch Surg. 2010;145(9):858-64.

- Bilotta F, Spinelli A, Giovannini F, Doronzio A, Delfini R, Rosa G. The effect of intensive insulin therapy on infection rate, vasospasm, neurologic outcome, and mortality in neurointensive care unit after intracranial aneurysm clipping in patients with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage: a randomized prospective pilot trial. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2007;19(3):156-60.Cao SG, Ren JA, Shen B, Chen D, Zhou YB, Li JS. Intensive versus conventional insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes patients undergoing D2 gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2011;35(1):85- 92.Emam IA, Allan A, Eskander K, Dhanraj K,

- Blondet JJ, Beilman GJ. Glycemic control and prevention of perioperative infection. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(4):421-7.

- Buchleitner AM, Martinez-Alonso M, Hernandez M, Sola I, Mauricio D. Perioperative glycaemic control for diabetic patients undergoing surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD007315.

- Cao S, Zhou Y, Chen D, Niu Z, Wang D, Lv L, et al. Intensive versus conventional insulin therapy in nondiabetic patients receiving parenteral nutrition after D2 gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(11):1961-8.

- Chan RP, Galas FR, Hajjar LA, Bello CN, Piccioni MA, Auler JO, Jr. Intensive perioperative glucose control does not improve outcomes of patients submitted to open-heart surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(1):51-60.

- Desai SP, Henry LL, Holmes SD, Hunt SL, Martin CT, Hebsur S, et al. Strict versus liberal target range for perioperative glucose in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(2):318-25.

- Dhatariya K, Corsino L, Umpierrez GE. Management of Diabetes and Hyperglycemia in Hospitalized Patients. 2020 Dec 30. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–. PMID: 25905318.

- Dogra P, Anastasopoulou C, Jialal I. Diabetic Perioperative Management. [Updated 2024 Jan 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540965/

- Farag el S, El-Kadi Y, et al. Our experience of controlling diabetes in the peri-operative period of patients who underwent cardiac surgery. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88(3):242-6Kao LS, Phatak UR. Glycemic control and prevention of surgical site infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14(5):437-44.

- Gandhi GY, Nuttall GA, Abel MD, Mullany CJ, Schaff HV, O'Brien PC, et al. Intensive intraoperative insulin therapy versus conventional glucose management during cardiac surgery: a randomized trial. Ann Int Med. 2007;146(4):233-43.

- Griesdale DE, de Souza RJ, van Dam RM, Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Malhotra A, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and mortality among critically ill patients: a meta-analysis including NICE-SUGAR study data. CMAJ. 2009;180(8):821-7.

- Grey NJ, Perdrizet GA. Reduction of nosocomial infections in the surgical intensive- care unit by strict glycemic control. Endocrine Pract. 2004;10(Suppl. 2):46-52.

- Kao LS, Meeks D, Moyer VA, Lally KP. Peri-operative glycaemic control regimens for preventing surgical site infections in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD006806.

- Kao LS, Phatak UR. Glycemic control and prevention of surgical site infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14(5):437-44.Kirdemir P, Yildirim V, Kiris I, Gulmen S, Kuralay E, Ibrisim E, et al. Does continuous insulin therapy reduce postoperative supraventricular tachycardia incidence after coronary artery bypass operations in diabetic patients? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22(3):383-7.

- Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, Umpierrez GE, Dellinger EP, Farrokhi ET, et al. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):97-103.

- Krikorian A, Ismail-Beigi F, Moghissi ES. Comparisons of different insulin infusion protocols: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010 Mar;13(2):198-204. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833571db. PMID: 20040862.

- Lazar HL, McDonnell MM, Chipkin S, Fitzgerald C, Bliss C, Cabral H. Effects of aggressive versus moderate glycemic control on clinical outcomes in diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3):458-63; discussion 63-4.

- McAnulty GR, Robertshaw HJ, Hall GM. Anaesthetic management of patients with diabetes mellitus. Br J Anaesthes. 2000;85(1):80-90.

- NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators; Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, Bellomo R, Cook D, Dodek P, Henderson WR, Hébert PC, Heritier S, Heyland DK, McArthur C, McDonald E, Mitchell I, Myburgh JA, Norton R, Potter J, Robinson BG, Ronco JJ. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 26;360(13):1283-97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. Epub 2009 Mar 24. PMID: 19318384.

- Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Sumiyoshi T, Kozuki A, Tokumaru T, Iiyama T, et al. Intensive versus intermediate glucose control in surgical intensive care unit patients. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1516-24.

- Richards JE, Hutchinson J, Mukherjee K, Jahangir AA, Mir HR, Evans JM, et al. Stress hyperglycemia and surgical site infection in stable nondiabetic adults with orthopedic injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(4):1070-5.

- de Vries FE, Gans SL, Solomkin JS, Allegranzi B, Egger M, Dellinger EP, Boermeester MA. Meta-analysis of lower perioperative blood glucose target levels for reduction of surgical-site infection. Br J Surg. 2017 Jan;104(2):e95-e105. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10424. Epub 2016 Nov 30. PMID: 27901264.

- Yuan J, Liu T, Zhang X, Si Y, Ye Y, Zhao C,et al. Intensive versus conventional glycemic control in patients with diabetes during enteral nutrition after gastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(8):1553-8.

- Zheng R, Gu C, Wang Y, Yang Z, Dou K, Wang J, et al. Impacts of intensive insulin therapy in patients undergoing heart valve replacement. Heart Surg Forum. 2010;13(5):E292-8.

Evidence tabellen

|

Author, year, references |

Type of surgery |

Population |

Definition of SSI |

Intervention

|

Control |

Timing |

Outcome* |

|

|

SSI |

Hypoglycaemia |

|||||||

|

Abdelmak (2013) |

Major noncardiac surgery |

Patients with and without diabetes |

Deep and organ space SSI |

Dynamic i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 80–110 (4⋅4–6⋅1) |

Dynamic i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 180–200 (10⋅0–11⋅1) |

During surgery and 2 h after surgery |

I: 17 of 196 C: 18 of 185 OR 0⋅88 (0⋅24,3⋅20); (P=0⋅72) |

At least 1 episode of BG <72⋅7 (4⋅0) I: 29 of 196 C: 4 of 185 No episodes of severe hypoglycaemia |

|

Albacker (2008) |

Cardiac surgery (CABG) |

Patients with and without diabetes |

Superficial wound infection |

Fixed high-dose i.v. insulin infusion with dextrose 20% for BG 70–110 (3⋅9–6⋅1) (‘insulin clamp’) |

i.v. insulin infusion to maintain BG |

During surgery

|

I: 1 of 27 C: 1 of 25 (P=0⋅99) |

None |

|

Bilotta (2007) |

Emergency cerebral aneurysm clipping |

Patients with and without diabetes |

Wound infections by NNIS definition |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion to maintain BG 80–120 (4⋅4–6⋅7) |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion to maintain BG 80–220 (4⋅4–12⋅2) |

During and after surgery (discharge from ICU or on day 14) |

I: 1 of 40 C: 2 of 38 |

BG <80 (4⋅4) More frequent in I group RR 3⋅0 (2⋅07, 4⋅35) |

|

Cao (2010) |

Gastrectomy

|

Patients with type 2 diabetes receiving parenteral nutrition |

Wound infection (SSI by CDC definition) |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 80–100 (4⋅4–6⋅7) |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion; target BG <200 (11⋅1) |

Postoperative until oral intake |

I: 4 of 92 C:12 of 87 |

Severe BG <40 (2⋅2) I: 6 of 92 C: 1 of 87 |

|

Cao (2011) |

Gastrectomy |

Patients without diabetes receiving parenteral nutrition |

Wound infection (SSI by CDC definition) |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 80–100 (4⋅4–6⋅7) |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion; target BG <200 (11⋅1) |

Postoperative until oral intake |

I: 5 of 125 C: 13 of 123 |

Severe BG <40 (2⋅2) I: 8 of 125 C: 1 of 123 |

|

Chan (2009) |

Cardiac surgery |

Patients with and without diabetes |

Wound infection |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion initiated at BG >130 (7⋅2); target BG 80–130 (4⋅4–7⋅2) |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion initiated if BG >200 (11⋅1); target BG 160–200 (8⋅9–11⋅1) |

During surgery and 36 h after surgery |

I: 6 of 54 C: 9 of 55 (P=0⋅09) |

BG <50 (2⋅8) No difference between groups (P=0⋅67) |

|

Desai (2012)

|

Cardiac surgery |

Patients with and without diabetes |

Deep sternal wound infection |

Target BG 90–120 (5⋅0–6⋅7) |

Target BG 121–180 (6⋅7–10⋅0) |

Postoperative for minimum of 72 h |

I: 1 of 91 C: 0 of 98 |

BG <60 (3⋅3) I: 30 of 91 C: 11 of 98 |

|

Emam (2010) |

Cardiac surgery |

Patients with type 2 diabetes |

Wound infection (superficial, deep) |

i.v. insulin infusion (Braithwaite protocol) on evening before surgery or sooner if BG ≥150 (8⋅3); target BG 100–150 (5⋅6–8⋅3) |

s.c. insulin per sliding scale; target BG <200 (11⋅1) |

During surgery and 48 h after surgery |

I: 0 of 80 C: 5 of 40 |

None BG <50 (2⋅8) |

|

Gandhi (2007) |

Cardiac surgery |

Patients with and without diabetes |

Deep sternal infections (as defined by Society of Thoracic Surgeons) |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion to maintain intraoperative BG 80–100 (4⋅4–5⋅6) |

No insulin during surgery unless BG >200 (11⋅1), then i.v. insulin infusion |

During and after surgery (not specified) |

I: 6 of 185 C: 7 of 186 RR 0⋅9 (0⋅3, 2⋅5); (P=0⋅79)

No difference when stratified by diabetic status |

BG <60 (3⋅3) Intraoperative I: 1 of 185 C: 1 of 185 RR 1⋅01 (0⋅06, 15⋅95)

During first 24 h in ICU I: 8 of 185 C: 14 of 185 |

|

Grey and Perdrizet (2004) |

Critical ill surgical patients |

All BG ≥140 (7⋅8) adult surgical ICU patients with and without diabetes |

SSI |

i.v. insulin infusion to maintain BG 80–120 (4⋅4–6⋅7) |

i.v. infusion to maintain BG 180–220 (10⋅0–12⋅2) |

Postoperative throughout ICU stay |

I: 2 of 34 C: 10 of 34 |

BG <60 (3⋅3) I: 32% C: 7⋅4% (P <0⋅001) |

|

Kirdemir (2008) |

Cardiac surgery |

Patients with diabetes |

Sternal wound infection |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 100–150 (5⋅6–8⋅3) |

s.c. insulin; target BG <200 (11⋅1) (sliding scale) |

During surgery and until day 3 after surgery |

I: 1 of 100 C: 12 of 100 (P=0⋅003) |

None |

|

Lazar (2011) |

Cardiac surgery |

Patients with diabetes |

Any sternal infection |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 90–120 (5⋅0–6⋅7) |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 120–180 (6⋅7–10⋅0) |

During surgery and 18 h after surgery |

I: 0 of 40 C: 0 of 42 |

BG <80 (4⋅4) I: 30 of 40 C: 4 of 42 |

|

Okabayashi (2014) |

Hepatobiliarypancreatic surgery |

Patients with and without diabetes |

SSI |

i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 80–110 (4⋅4–6⋅1) |

i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 140–180 (7⋅8–10⋅0) |

During and after surgery |

I: 9 of 222 C: 22 of 225 (P=0⋅028) |

None BG |

|

Yuan (2015) |

Gastrectomy |

Patients with type 2 diabetes |

SSI |

Continuous i.v. insulin infusion; target BG 80–110 (4⋅4–6⋅1) |

s.c. bolus insulin; target BG <200 (11⋅1) |

Postoperative |

I: 5 of 106 C: 14 of 106 (P <0⋅03) |

Severe BG <40 (2⋅2) I: 8 of 106 C: 1 of 106 (P=0⋅035) |

|

Zheng (2010) |

Cardiac surgery (valve replacement) |

Patients without diabetes |

Nosocomial infections of deep sternal wounds |

Continuous i.v. infusion to maintain BG 70–110 (3⋅9–6⋅1) (Portland protocol) |

Standard care, no control for BG |

During and after surgery |

I: 1 of 50 C: 4 of 50 |

I: 3 of 50 C: 1 of 50 |

**Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. Blood glucose (BG) values are shown without units (mg/dl (mmol/l)). SSI, surgical-site infection; i.v., intravenous; I, intensive; C, conventional; OR, odds ratio; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; NNISS, National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System; RR, relative risk; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; s.c., subcutaneous.

|

Reference |

Intensive group |

Conventional group |

Adverse events |

||

|

Target level (mg/dl) |

Achieved level (mg/dl) |

Target level (mg/dl) |

Achieved level (mg/dl) |

||

|

Abdelmak (2013) |

80–110 |

Mean 108 (range 100–121) |

180–200 |

Mean 139 (range 124–165) |

Hypoglycaemia: I: 29 of 196; C: 4 of 185 had at least 1 episode of moderate hypoglycaemia (< 73 mg/dl). No episodes of severe hypoglycaemia (< 40 mg/dl) Stroke: I: 0 of 196; C: 0 of 185 30-day mortality: I: 4 of 196; C: 4 of 185 |

|

Albacker (2008) |

70–110 |

Mean 88 (95% c.i. 81, 92) |

< 180 |

Mean 124 (95% c.i. 108, 137) |

Hypoglycaemia: I: 0 of 27; C: 0 of 25 Stroke: I: 0 of 27; I: 0 of 25 In-hospital mortality: I: 0 of 27; C: 0 of 25 |

|

Bilotta (2007) |

80–120 |

69% of measured levels within target value; 10.5% < 80 mg/dl, 20.5% > 120 mg/dl |

80–220 |

83% of measured levels within target value; 3.5% < 80 mg/dl, 13.5% > 220 mg/dl |

Hypoglycaemia (< 80 mg/dl) occurred more in the strict group compared with the conventional group (RR 3.0, 95% c.i. 2.07, 4.35) Stroke: n.s. 6-month mortality: I: 6 of 40; C: 7 of 38 |

|

Cao (2010) |

80–100 |

Mean(s.d.) 99(14) |

< 200 |

Mean(s.d.) 178(18) |

Hypoglycaemia (< 40 mg/dl): I: 6 of 92; C: 1 of 87 Stroke: n.s. In-hospital mortality: I: 4 of 92; C: 5 of 87 |

|

Cao (2011) |

80–100 |

Mean(s.d.) 95(15) |

< 200 |

Mean(s.d.) 184(17) |

Hypoglycaemia (< 40 mg/dl): I: 8 of 125; C: 1 of 123 Stroke: n.s. In-hospital mortality: I: 1 of 125; C: 2 of 123 |

|

Chan (2009) |

80–130 |

Mean 127 |

160–200 |

Mean 168 |

Hypoglycaemia (< 50 mg/dl) – ratio of hypoglycaemic episodes per number of glucose measurements: I: 2.1%; C: 2.9% (P = 0.67) Stroke: n.s. Mortality: I: 3 of 54; C: 4 of 55 |

|

Desai (2012)

|

90–120 |

Minimum mean(s.d.): 66.6(13.9) Maximum mean(s.d.): 213(48.2) |

121–180 |

Minimum mean(s.d.): 84.4(17.8) Maximum mean(s.d.): 218.3(46.8) |

Hypoglycaemia (< 60 mg/dl): I: 30 of 91; C: 11 of 98 Stroke: n.s. Operative mortality: I: 1 of 91; C: 1 of 98 |

|

Emam (2010) |

100–150 |

Mean(s.d.) 151.6(20.8) |

< 200 |

Mean(s.d.) 211.1(38.6) |

Hypoglycaemia (< 50 mg/dl): I: 0 of 80; C: 0 of 40 Stroke: n.s. Mortality: n.s. |

|

Gandhi (2007) |

80–100 |

Mean(s.d.) baseline in ICU: 114(29) Mean(s.d.) 24-h ICU: 103(17) |

< 200 |

Mean(s.d.) baseline in ICU: 157(42) Mean 24-h ICU: 104 |

Hypoglycaemia (< 60 mg/dl): Intraoperative: I: 1 of 185; C: 1 of 186; ICU: I: 8 of 185; C: 14 of 186 Stroke: I: 8 of 185; C: 11 of 186 Mortality: I: 4 of 185; C: 0 of 186 |

|

Grey and Perdrizet (2004) |

80–120 |

Mean(s.d.) 125(36) |

180–220 |

Mean(s.d.) 179(61) |

Hypoglycaemia (< 60 mg/dl): Hypoglycaemic events (< 60 mg/dl) occurred in 32% of patients in strict protocol and 7.4% of patients in conventional protocol group (P < 0.001) Stroke: n.s. Mortality: I: 4 of 34; C: 7 of 34 |

|

Kirdemir (2008) |

100–150 |

Mean(s.d.) 172.4(23.6) |

< 200 |

Mean(s.d.) 195.5(65.5) |

Hypoglycaemia: I: 0 of 100; C: 0 of 100 (P < 0.001) Stroke: I: 1 of 100; C: 1 of 100 Mortality: I: 2 of 100; C: 5 of 100 (P = 0.044) |

|

Lazar (2011) |

90–120 |

Mean(s.d.) 103(17) |

120–180 |

Mean(s.d.) 135(12) |

Hypoglycaemia(< 80 mg/dl): I: 30 of 40; C: 4 of 42 Stroke: I: 0 of 40; C: 1 of 42 (P = 0.47) 30-day mortality: I: 0 of 40; C: 0 of 42 |

|

Okabayashi (2014) |

80–110 |

85.8% within target range |

140–180 |

96.8% within target range |

Hypoglycaemia (< 80 mg/dl): I: 0 of 222; C: 0 of 225 Stroke: n.s. Mortality: n.s. |

|

Yuan (2015) |

80–110 |

Mean(s.d.) 97.2(21.6) |

< 200 |

Mean(s.d.) 171(32.4) |

Hypoglycaemia: I: 8 of 106; C: 1 of 106 (P = 0.035) Stroke: I: 0 of 106; C: 1 of 106 Mortality: I: 1 of 106; C: 1 of 106 |

|

Zheng (2010) |

70–110 |

Blood glucose levels significantly higher in control than in intensive group (P < 0.01) |

Standard care (n.s.) |

Blood glucose levels significantly higher in control than in intensive group (P < 0.01) |

Hypoglycaemic events: I: 3 of 50; C: 1 of 50 Stroke: n.s. Mortality: I: 2 of 50; C: 3 of 50 |

|

Reference |

Intensive group target glucose level (mg/dl (mmol/l)) and method of administration/protocol |

Conventional group target level (g/dl (mmol/l)) and method of administration |

Definition of hypoglycaemia (mg/dl (mmol/l)) |

|

Abdelmak (2013) |

80–110 (4.4–6.1); dynamic intravenous infusion |

180–200 (10.0–11.1); dynamic i.v. infusion |

Moderate < 73 (4.0) Severe < 40 (2.2) |

|

Albacker (2008) |

70 and 110 (3.9–6.1); fixed high-dose i.v. insulin infusion with dextrose 20% separately to maintain glucose level between 70 and 110 (3.9–6.1) (‘insulin clamp’) |

< 180 (< 10.0); i.v. insulin infusion per sliding scale |

n.s. |

|

Bilotta (2007) |

80–120 (4.4–6.7); continuous i.v. insulin infusion |

80–220 (4.4–12.2); continuous i.v. insulin infusion |

< 80 (4.4) |

|

Cao (2010) |

80–100 (4.4–5.6) ; continuous i.v. insulin infusion (Portland protocol) |

< 200 (< 11.1); continuous i.v. insulin infusion (Portland protocol) |

< 40 (2.2) |

|

Cao (2011) |

80–100 (4.4–5.6) ; continuous i.v. insulin infusion (Portland protocol) |

< 200 (< 11.1); continuous i.v. insulin infusion (Portland protocol) |

< 40 (2.2) |

|

Chan (2009) |

80–130 (4.4–7.2); continuous i.v. insulin infusion (Leuven modified protocol) |

160–200 (8.9–11.1); continuous i.v. insulin (Leuven modified protocol) |

< 50 (2.8) |

|

Desai (2012) |

90–120 (5.0–6.7); i.v. insulin infusion (Glucommander) |

121–180 (6.7–10.0); intravenous insulin infusion (Glucommander) |

< 60 (3.3) |

|

Emam (2010) |

100–150 (5.6–8.3); i.v. insulin infusion (Braithwaite protocol) |

< 200 (< 11.1); s.c. insulin per sliding scale |

< 50 (2.8) |

|

Gandhi (2007) |

80–100 (4.4–5.6); continuous insulin infusion |

< 200 (< 11.1); intermittent i.v. infusion |

< 60 (3.3) |

|

Grey and Perdrizet (2004) |

80–120 (4.4–6.7); intravenous infusion |

180–220 (10.0–12.2); i.v. infusion |

< 60 (3.3) |

|

Kirdemir (2008) |

100–150 (5.6–8.3); continuous i.v. infusion (Portland protocol) |

< 200 (< 11.1); s.c. insulin per sliding scale |

n.s. |

|

Lazar (2011) |

90–120 (5.0–6.7); continuous i.v. infusion |

120–180 (6.7–10.0) continuous i.v. infusion |

< 80 (4.4) |

|

Okabayashi (2014) |

80–110 (4.4–6.1); i.v. infusion (closed-loop glycaemic control) |

140–180 (7.8–10.0); i.v. infusion (closed-loop glycaemic control) |

< 80 (4.4) |

|

Yuan (2015) |

80–110 (4.4–6.1); continuous i.v. infusion |

< 200 (< 11.1); s.c. insulin |

< 40 (2.2) |

|

Zheng (2010) |

70–110 (3.9–6.1); continuous i.v. infusion (Portland protocol) |

Standard care (n.s.) |

n.s. |

Risk of bias assessment of the included studies

|

RCT Author, year, reference |

Sequence generation

|

Allocation concealment |

Participants blinded |

Care providers blinded |

Outcome assessors blinded |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective outcome reporting |

|

Abdelmak (2013) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

|

Albacker (2008) |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

High |

Unclear |

High |

|

Bilotta (2007) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Cao (2010) |

Unclear |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Cao (2011) |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

High |

|

Chan (2009) |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Desai (2012)

|

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

High |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Emam (2010) |

High |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Gandhi (2007) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Grey and Perdrizet (2004) |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

|

Kirdemir (2008) |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

|

Lazar (2011) |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

|

Okabayashi (2014) |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

|

Yuan (2015) |

Low |

Unclear |

High |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Zheng (2010) |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Comparisons

In addition to the odds ratios (OR) reported by the WHO, relative risks (RR) and risk differences (RD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted and pooled with a random effects model and added to the current literature analysis.1

Surgical site infections for the comparison of intensive perioperative glucose control protocols vs. conventional protocols (odds-ratio).

Surgical site infections for the comparison of intensive perioperative glucose control protocols vs. conventional protocols (risk-ratio).

SSI-attributable mortality for the comparison of intensive perioperative glucose control protocols vs. conventional protocols (odds-ratio).

SSI-attributable mortality for the comparison of intensive perioperative glucose control protocols vs. conventional protocols (risk-ratio).

Hypoglycaemic events for the comparison of intensive perioperative glucose control protocols vs. conventional protocols (odds-ratio).

Hypoglycaemic events for the comparison of intensive perioperative glucose control protocols vs. conventional protocols (risk-ratio).

Postoperative strokes for the comparison of intensive perioperative glucose control protocols vs. conventional protocols (odds-ratio).

Postoperative strokes for the comparison of intensive perioperative glucose control protocols vs. conventional protocols (risk-ratio).

Perioperative glucose target levels for reduction of surgical-site infection

GRADE Table

|

Quality assessment |

No. of patients |

Effect |

Quality |

||||||||

|

No. of studies |

Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency |

Indirectness |

Imprecision |

Other considerations |

Intensive perioperative glucose control protocol |

Conventional protocol |

Odds-ratio (95% CI |

Relative risk ratio (95% CI |

|

|

Surgical site infections |

|||||||||||

|

15 |

RCTs |

Serious1 |

Not serious |

Serious2 |

Not serious |

None |

59/1442 (4.1%) |

129/1394 (9.3%) |

OR: 0.43 (0.29-0.64)

|

RR: 0.47 (0.33-0.67) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ LOW |

|

Mortality |

|||||||||||

|

13 |

RCTs |

Serious1 |

Not serious |

Serious2 |

Not serious |

None |

32/1140 (2.8%) |

39/1129 (3.5%) |

OR: 0.74 (0.45-1.23) |

RR: 0.76 (0.48-1.20) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ LOW

|

|

Hypoglycaemic events |

|||||||||||

|

12 |

RCTs |

Serious1 |

Not serious |

Serious2 |

Serious3 |

None |

122/1314 (9.3%) |

30/1267 (2.4%) |

OR: 5.55 (1.41-69.20) |

OR: 4.03 (2.31-7.03) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ LOW

|

|

Postoperative strokes |

|||||||||||

|

6 |

RCTs |

Serious1 |

Not serious |

Serious2 |

Serious3 |

None |

9/654 (1.4%) |

4/644 (0.6%) |

OR: 1.37 (0.26-7.20) |

OR: 1.36 (0.26-7.04) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ Very LOW |

- Lack of blinding (especially outcome assessors).

- Indirectness since most included studies investigated patients in an ICU setting.

- Imprecision since the 95% confidence interval crosses one or both thresholds for clinical relevance.

SSI: surgical site infection; RCT: randomized controlled trial; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Study selection

Search Strategy

Disclaimer: This is an adaptation of an original work “Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.” (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475). This adaptation was not created by WHO. WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this adaptation. The original edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.

1 The WHO-guideline did not report relative risks and risk differences.

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-12-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 01-12-2024

Geplande herbeoordeling : 01-12-2026

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS) en . De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules 2 tot 16 is in 2020 op initiatief van de NVvH een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Daarnaast is in 2022 op initiatief van het Samenwerkingsverband Richtlijnen Infectiepreventie (SRI) een separate multidisciplinaire werkgroep samengesteld voor de herziening van de WIP-richtlijn over postoperatieve wondinfecties: module 17-22. De ontwikkelde modules van beide werkgroepen zijn in deze richtlijn samengevoegd.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoek financiering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Werkgroep NVvH - Module 2-16

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. prof. dr. M.A. Boermeester |

Chirurg |

* Medisch Ethische Commissie, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC * Antibiotica Commissie, Amsterdam UMC |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Hieronder staan de beroepsmatige relaties met bedrijfsleven vermeld waarbij eventuele financiële belangen via de AMC Research B.V. lopen, dus institutionele en geen persoonlijke gelden zijn: Skillslab instructeur en/of spreker (consultant) voor KCI/3M, Smith&Nephew, Johnson&Johnson, Gore, BD/Bard, TELABio, GDM, Medtronic, Molnlycke.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Institutionele grants van KCI/3M, Johnson&Johnson en New Compliance.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Ik maak me sterk voor een 100% evidence-based benadering van maken van aanbevelingen, volledig transparant en reproduceerbaar. Dat is mijn enige belang in deze, geen persoonlijk gewin.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Extra kritische commentaarronde. |

|

Dhr. dr. M.J. van der Laan |

Vaatchirurg |

Vice voorzitter Consortium Kwaliteit van Zorg NFU, onbetaald

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. W.C. van der Zwet |

Arts-microbioloog |

Lid Regionaal Coördinatie Team, Limburgs infectiepreventie & ABR Zorgnetwerk (onbetaald) |

||

|

Dhr. dr. D.R. Buis |

Neurochirurg |

Lid Hoofdredactieraad Tijdschrift voor Neurologie & Neurochirurgie - onbetaald |

||

|

Dhr. dr. J.H.M. Goosen |

Orthopaedisch Chirurg |

Inhoudelijke presentaties voor Smith&Nephew en Zimmer Biomet. Deze worden vergoed per uur. |

||

|

Mw. drs. H. Jalalzadeh |

Arts-onderzoeker |

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. N. Wolfhagen |

AIOS chirurgie |

|||

|

Mw. drs. H. Groenen |

Arts-onderzoeker |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. F.F.A. Ijpma |

Traumachirurg |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. P. Segers |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

|||

|

Mw. Y.E.M. Dreissen |

AIOS neurochirurgie |

|||

|

Dhr. R.R. Schaad |

Anesthesioloog |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt. Voor de modules 17-22 was de patiëntfederatie vertegenwoordigd in de werkgroep.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Voor module 8 (Negatieve druktherapie) geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000 - 40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Voor de overige modules en aanbevelingen geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Ook wordt geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners verwacht of een wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Zie voor de implementatie het implementatieplan in het tabblad 'Bijlagen'.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroepen de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een invitational conference. De verslagen hiervan zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Adaptatie

Een aantal modules van deze richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van modules van de World Health Organization (WHO)-richtlijn ‘Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection’ (WHO, 2018), te weten:

- Module Normothermie

- Module Immunosuppressive middelen

- Module Glykemische controle

- Module Antimicrobiële afdichtingsmiddelen

- Module Wondbeschermers bij laparotomie

- Module Preoperatief douchen

- Module Preoperatief verwijderen van haar

- Module Chirurgische handschoenen: Vervangen en type handschoenen

- Module Afdekmaterialen en operatiejassen

Methode

- Uitgangsvragen zijn opgesteld in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- De inleiding van iedere module betreft een korte uiteenzetting van het knelpunt, waarbij eventuele onduidelijkheid en praktijkvariatie voor de Nederlandse setting wordt beschreven.

- Het literatuuronderzoek is overgenomen uit de WHO-richtlijn. Afhankelijk van de beoordeling van de actualiteit van de richtlijn is een update van het literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd.

- De samenvatting van de literatuur is overgenomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij door de werkgroep onderscheid is gemaakt tussen ‘cruciale’ en ‘belangrijke’ uitkomsten. Daarnaast zijn door de werkgroep grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming gedefinieerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten, en is de interpretatie van de bevindingen primair gebaseerd op klinische relevantie van het gevonden effect, niet op statistische significantie. In de meta-analyses zijn naast odds-ratio’s ook relatief risico’s en risicoverschillen gerapporteerd.

- De beoordeling van de mate van bewijskracht is overgnomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij de beoordeling is gecontroleerd op consistentie met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (GRADE-methode; http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). Eventueel door de WHO gerapporteerde bewijskracht voor observationele studies is niet overgenomen indien ook gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies beschikbaar waren.

- De conclusies van de literatuuranalyse zijn geformuleerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- In de overwegingen heeft de werkgroep voor iedere aanbeveling het bewijs waarop de aanbeveling is gebaseerd en de aanvaardbaarheid en toepasbaarheid van de aanbeveling voor de Nederlandse klinische praktijk beoordeeld. Op basis van deze beoordeling is door de werkgroep besloten welke aanbevelingen ongewijzigd zijn overgenomen, welke aanbevelingen niet zijn overgenomen, en welke aanbevelingen (mits in overeenstemming met het bewijs) zijn aangepast naar de Nederlandse context. ‘De novo’ aanbevelingen zijn gedaan in situaties waarin de werkgroep van mening was dat een aanbeveling nodig was, maar deze niet als zodanig in de WHO-richtlijn was opgenomen. Voor elke aanbeveling is vermeld hoe deze tot stand is gekomen, te weten: ‘WHO’, ‘aangepast van WHO’ of ‘de novo’.

Voor een verdere toelichting op de procedure van adapteren wordt verwezen naar de Bijlage Adapteren.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.