MRI bij elektronisch cardiaal implantaat

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zou het algemene beleid moeten zijn bij patiënten met elektronische cardiale implantaten die een MRI moeten ondergaan?

De elektronische cardiale implantaten worden in het Engels afgekort als CIED, wat staat voor Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device. Deze afkorting wordt in deze module gebruikt.

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling 1

- Scan patiënten met een MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s volgens instructie van de CIED fabrikant.

Indien dit niet kan:

- Maak bij patiënten met een niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s (ook bij combinaties van lead en generator van verschillende fabrikanten) een risico-afweging alvorens te scannen. Indien deze CIED in het af te beelden gebied ligt: neem het effect van CIED op de beeldkwaliteit mee in de overweging.

- Maak bij aanwezigheid van transveneuze draden een risico-afweging; aanwezigheid van transveneuze draden vormt geen harde contra-indicatie voor een MRI-onderzoek.

- Overweeg sterk een andere beeldvormingstechniek dan MRI indien er epicardiale draden aanwezig zijn.

- Bij MRI met de CIED in het af te beelden gebied: neem beeldkwaliteit mee in de overweging.

- Voer Diagnostisch MRI-onderzoek uit bij 1,5 T.

- Gebruik SAR ≤ 2 W/kg, bij lagere SAR minder kans op opwarming.

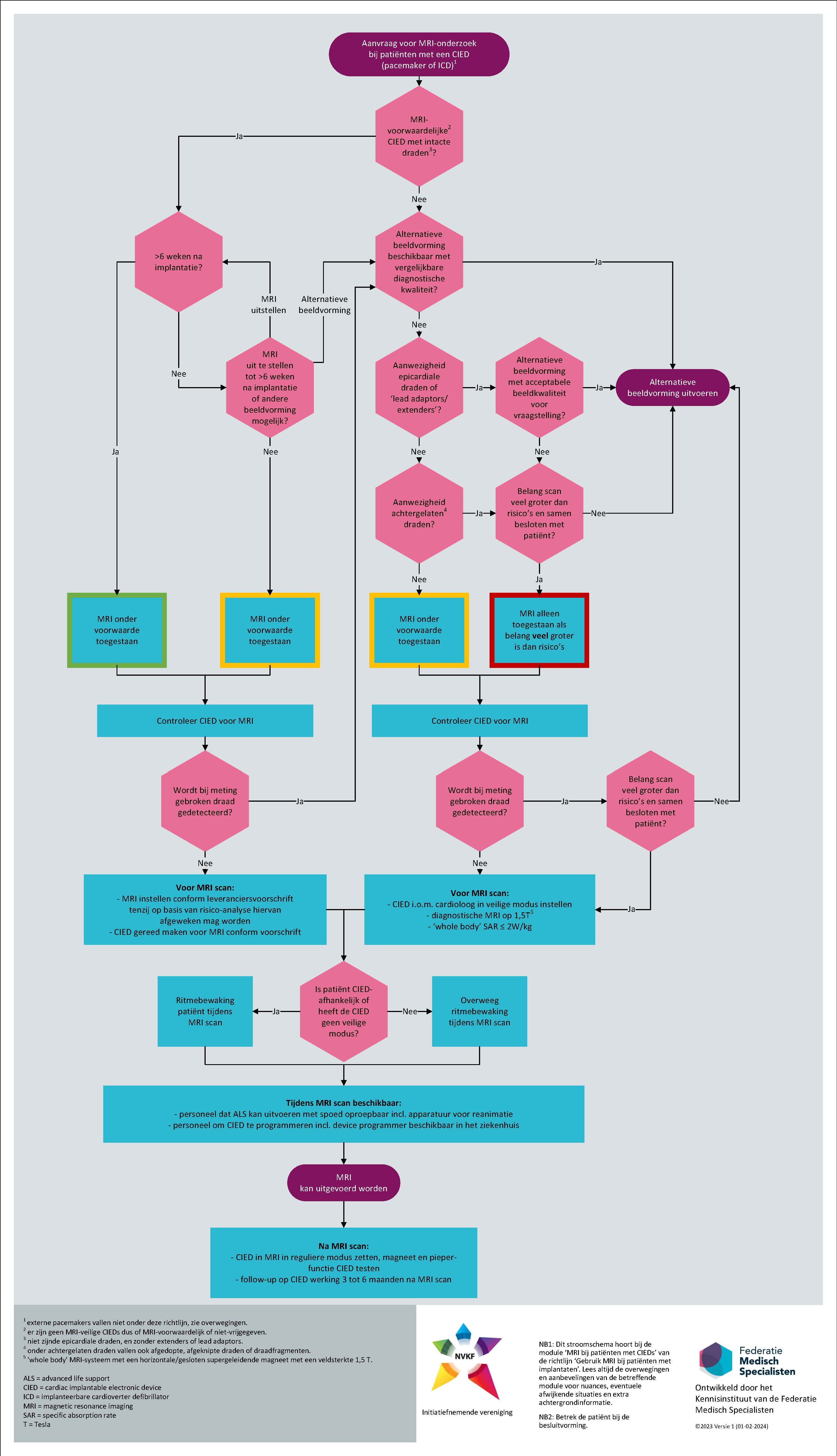

Gebruik hiervoor figuur 1 als beslisschema.

Aanbeveling 2

Stel een procedure op voor het scannen van patiënten met een CIED. Leg hierin vast wat te doen bij: MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s, niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s, metingen aan de CIED voor en na het MRI-onderzoek, en wat te doen bij een calamiteit.

Aanbeveling 3

- Ritmebewaking is noodzakelijk bij patiënten die pacemaker afhankelijk zijn, en bij niet-pacemaker afhankelijkheid indien de CIED niet in veilige modus gezet kan worden.

- Overweeg ritmebewaking bij niet-pacemaker afhankelijkheid indien de CIED in veilige modus gezet kan worden.

- Ritmebewaking is noodzakelijk voor alle patiënten met een implanteerbare cardioverter/defibrillator (ICD).

- Ritmebewaking middels pulsoxymetrie is te prefereren boven ECG bewaking.

- Het reanimatieteam is met spoed oproepbaar conform leidraad vitaal bedreigde patiënt.

- Personeel is met spoed oproepbaar om de CIED te kunnen programmeren in geval van pacemaker afhankelijke patiënten of patiënten met een ICD.

Aanbeveling 4

Laat een looprecorder uitlezen voorafgaande aan het MRI-onderzoek indien deze niet dagelijks wordt uitgelezen (kijk in tabel 10 ‘samenvatting informatie implantaatfabrikanten voor loop recorders’ of dit nodig is voor het specifieke model).

Als de patiënt van buiten de EU komt: controleer de MR-classificatie van het type loop recorder.

Overwegingen

Er zijn twee internationale consensus statements (HRS consensus statement (Indik 2017) en de ESC Guideline (Glikson 2021)) gevonden die een advies geven over omgaan met MR-voorwaardelijke en niet-voorwaardelijke CIED’s. In beide statements worden niet alleen MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s toegestaan voor MRI-onderzoek maar wordt ook voor niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s aangegeven onder welke condities toch gescand mag worden. Het is voor patiënten met CIEDS van groot belang dat ze een MRI-onderzoek kunnen ondergaan voor het stellen van een diagnose, mits de risico’s hiervan acceptabel zijn. Daarom is in het HRS consensus statement (Indik 2017) en in de ESC Guideline (Glikson 2021) veel aandacht voor een juiste medische risico-afweging van de voordelen van scannen versus de risico’s van het MRI-onderzoek op de patiënt en op de werking van de CIED (en het effect van malfunctie ervan voor de patiënt).

Er zijn zeven vergelijkende studies en een systematische review geïncludeerd die verschillende vergelijkingen maken, als toevoeging op de consensus expert opinion van Indik (2017). Door de lage aantallen die zijn gerapporteerd en sterke heterogeniteit was het niet mogelijk om de resultaten te poolen. De bewijskracht is mede hierdoor GRADE zeer laag. Er zijn 19 niet-vergelijkende studies gevonden (zie bijlage 1 voor overzicht van studies).

De conclusie die getrokken kan worden uit deze studies is dat het optreden van negatieve effecten door het ondergaan van een MRI relatief laag is, er zijn weinig ernstige complicaties waargenomen (<1% van de MRI-onderzoeken bij niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s, voornamelijk in oudere CIED’s), wel wordt incidenteel verstoring van de CIED waargenomen (<5% van de onderzochte CIED’s in de studies, in de niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s, en regelmatig treedt toename van de impedantie van de lead op. De risico’s rond gewijzigde werking van de CIED’s kunnen gemitigeerd worden door een goede procedure en het nameten van een CIED na een MRI-onderzoek.

Er zijn weinig vergelijkende studies uitgevoerd naar de mogelijk nadelige effecten van een MRI-onderzoek bij niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED waardoor een verhoogd risico niet aantoonbaar is vanuit literatuur. Echter, vanuit fysica is te onderbouwen dat risico’s voor patiënten met een niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED groter zullen zijn als ze gescand worden op een 3 T MRI dan op een 1,5 T MRI omdat de interactie en frequentie van RF op 3 T groter respectievelijk hoger zijn. Daarom is de aanbeveling bij deze patiënten het diagnostisch MRI-onderzoek op 1,5 T te laten plaatsvinden tenzij het noodzakelijk is voor de diagnostiek dat deze scan op 3 T gemaakt wordt. In dat geval moeten de grotere risico’s van 3 T versus 1,5 T meegenomen worden in de afweging van de risico’s t.o.v. de baten. Bij MRI geleide interventies is vaak niet de keus tussen 1,5 en 3T, en is 3T daarmee eerder gerechtvaardigd.

In alle consensus statements wordt benadrukt dat het van groot belang is om een aantal afspraken te maken over het medisch toezicht, de bewaking van de patiënt en de instellingen van de CIED voor en controle na een MRI-onderzoek (HRS, ESC maar ook de Franse, Canadese, Portugese landelijke consensus statements). In vrijwel ieder consensus statement is opgenomen dat de CIED indien mogelijk op een MRI veilige modus ingesteld wordt. Verder is het consensus statement doorgaans dat medisch toezicht tijdens de procedure noodzakelijk is; hiervoor moeten afspraken gemaakt worden met de afdeling cardiologie, daarnaast wordt ritmebewaking geadviseerd.

Deze overwegingen worden over het algemeen ook teruggevonden in de informatie van de implantaatfabrikanten t.a.v. voorwaarden waaronder de MRI-voorwaardelijke CIED in de MRI gescand mag worden – zie Samenvatting informatie implantaatfabrikanten.

* Bij 1,5 en 3 T geldt alleen MRI voorwaardelijk voor ‘whole body’ MRI-systeem met een horizontale/gesloten supergeleidende magneet

Tabel 10. Samenvatting informatie implantaatfabrikanten voor looprecorders.

|

Fabrikant |

Medtronic |

St Jude Medical (Abbott) |

Biotronik |

Boston Scientific |

Angel Medical Systems |

|

Modellen |

REVEAL LINQ™ LNQ11 LINQ II™ LNQ22 |

Confirm Rx Insertable Cardiac Monitor Model DM3500 |

Biomonitor 2 Biomonitor III Biomonitor IIIm |

LUX-Dx instertable cardiac monitoring system M301 |

Angelmed Guardian* |

|

MRI |

MR voorwaardelijk 1,5 T en 3 T

Risico van verlies van data. Als de patiënt geen ‘home monitor’ thuis heeft die de data dagelijks doorstuurt moet deze voor het MRI-onderzoek worden uitgelezen bij een pacemaker/ICD technicus

Gebruik geen lokale RF zendspoelen bij de romp |

MR voorwaardelijk 1,5 T en 3 T

Risico van verlies van data. Als de patiënt geen ‘home monitor’ thuis heeft die de data dagelijks doorstuurt moet deze voor het MRI-onderzoek worden uitgelezen bij een pacemaker/ICD technicus

Gebruik geen lokale RF zendspoelen bij de romp |

MR voorwaardelijk 1,5 T en 3 T

Gebruik geen lokale RF zendspoelen bij de romp |

MR voorwaardelijk 1,5 T en 3 T

Gebruik geen lokale RF zendspoelen bij de romp |

MR onveilig |

* in 2023 heeft dit systeem geen CE keurmerk, wel een FDA ‘approval’. Het zou kunnen voorkomen bij patiënten van buiten de EU.

Indeling risico’s implantaten in hoofdklassen

Over de risico’s is slechts generieke kwantitatieve informatie beschikbaar, omdat deze afhangen van de CIED maar ook scangebied en MRI-sequentie die gebruikt wordt. In Munawar (2020) wordt aangegeven dat bij niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s de kans op ernstige risico’s <1 % is, de kans op een elektrische reset 1,5%, het risico dat met een goede procedure te mitigeren is.

De risico’s van het MRI-onderzoek voor patiënten met een CIED worden samengevat in het HRS consensus statement en zijn hieronder kort samengevat:

- Risico’s als gevolg van verplaatsing en rotatie

Dit risico wordt door Indik et al. (2017) zeer klein geschat: de generator heeft enerzijds wel ferromagnetische onderdelen, echter CIED-generatorbeweging is zeer onwaarschijnlijk vanwege opsluiting in de onderhuidse weefsels en leads bevatten geen significante hoeveelheid ferromagnetische materialen. Er is weinig literatuur over gevonden, wel kan er een risico zijn op verplaatsing van de generator en een kans op ontkoppeling electrode. In het HRS statement is daarom opgenomen dat het de voorkeur heeft om een MRI uit te stellen tot minstens 6 weken na plaatsing om zo het risico op verplaatsing te verkleinen.

- Risico op opwarming van het implantaat door interactie met het RF-veld

RF-velden voor MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s zijn getest en bij scannen conform de voorwaarden zullen deze niet tot onvoorziene opwarming kunnen leiden. In CIED’s die niet MR voorwaardelijk zijn zouden RF-velden wel kunnen leiden tot CIED component opwarming en thermische schade geven aan het omliggende weefsel (functionele ablatie). Met name de opwarming van de leads en vooral van epicardiale of achtergelaten (‘abandoned’) leads en daarmee samenhangende weefselschade wordt gezien als mogelijk risico (ESC richtlijn, Glikson 2021).

Literatuur over achtergelaten leads, zie tabel 6, laat zien dat deze, indien in transveneus gebied, voldoende afkoeling kennen door de bloedstroming en gescand kunnen worden op een instelling met een SAR ≤ 2 W/kg. Een striktere SAR in stelling (≤1,5 W/kg) werd gebruikt in de systematische studie van Padmanabhan (2018). Voor epicardiale leads blijkt uit literatuur, zie tabel 6, dat er wel risico’s zijn, met name als de leads niet meer aangesloten zijn. Hoe langer de lead, hoe warmer deze kan worden en lokaal een ablatief effect kan geven. Een eerste effect van weefselbeschadiging nabij de elektroden, het lead uiteinde, is verandering in de sensing- of stimulatie-drempel. Dit effect heeft voor de achtergelaten leads geen betekenis meer, maar door de lokale opwarming kan een pijnprikkel ontstaan.

- Risico op trilling of stroominductie door de oscillerende magnetische veldgradiënt

Theoretisch kunnen gradiëntvelden stroom induceren in de leads die het hart zouden kunnen stimuleren, hetgeen zou kunnen leiden tot atriale of ventriculaire aritmieën, echter in studies naar effecten van MRI op pacemakers is hier nooit melding van gemaakt Munawar (2020). Wel kwam het voor dat pacemakers die in ‘demand’ modus stonden gradiëntveld geïnduceerde signalen verkeerd interpreteerde waardoor dit pacemaker aritmie veroorzaakte, maar dit valt onder risico 6.

- Artefact in het MRI beeld

Omdat CIED’s metaal bevatten kunnen deze artefacten geven op het moment dat het in of nabij het af te beelden gebied ligt. Dit betreft beelddistorsie en signaalverlies in en rondom de CIED. Artefacten zijn lastig van tevoren te voorspelen vanwege de vele variabelen binnen het lichaam; bijv. objectgrootte en -vorm, positie in het lichaam van de patiënt, magnetische gevoeligheid van de CIED, diëlektrische constante van het lichaam, lichaamsgrootte en -vorm van de patiënt, specifieke gebruikte pulssequentie en gekozen parameters van de pulssequentie. Wel kunnen door juiste keuzes in pulssequentie en parameters artefacten worden verminderd.

- Risico van krachten door het Lenz-effect

Als elektrisch geleidende implantaten bewegen in een extern magnetisch veld, kunnen er stromen opgewekt worden in het implantaat die resulteren in krachten op het implantaat (het Lenz-effect, gerelateerd aan Faraday’s wet van inductie en Eddy stromen). De grootte van de kracht is gerelateerd aan de temporele verandering in de magnetische flux. Dit kan voorkomen als het implantaat roteert terwijl de patiënt in de bore ligt of wanneer de patiënt door tafelbeweging de bore ingebracht wordt Graf 2006, McRobbie 2020).

Dit eerste effect is met name relevant voor hartkleppen en is in silico en in vitro bestudeerd (Edwards 2015, Golestanirad 2012, Robertson 2000, Condon 2000). Voor grotere implantaten is met name het tweede effect van belang (McRobbie 2020). Voor beide effecten hebben we geen bewijs gevonden dat deze klinisch relevant zijn voor de patiënt.

In vergelijking met hartkleppen ondervinden CIED’s relatief weinig beweging en in vergelijking met grotere implantaten (zoals heupimplantaten) zijn de krachten op de CIED ook een stuk kleiner, terwijl we verwachten dat de inkapseling van CIED’s goed is na 6 weken. Daarnaast hebben we geen bewijs gevonden in de literatuur dat het Lenz-effect op CIED’s klinisch relevante effecten geeft bij patiënten. We concluderen daarom dat de risico’s ten gevolge van het Lenz effect voor patiënten met CIED’s die MRI ondergaan op ‘whole body’ systemen met een horizontale/gesloten supergeleidende magneet met een veldsterkte van 1,5 T of 3 T verwaarloosbaar zijn.

- Risico op verstoring van de werking van het implantaat

Er bestaat een risico op verstoring van de werking van de CIED, wat risicovol voor de patiënt zou kunnen zijn:

-

- De magneet-schakelaar zorgt ervoor dat een pacemaker tijdelijk geprogrammeerd wordt in een asynchrone modus en ICD en in geval van een ICD in een ‘tachy uit’ modus. In niet-MR-voorwaardelijke pacemakers kan deze schakelaar geactiveerd worden door de magneet van de MRI, met asynchrone pacing tot mogelijk gevolg. Ook kan de magneetschakelaar worden beschadigd zo dat de magneet functie niet meer beschikbaar is.

- Er kan een power-on reset plaatsvinden die de pacing kan stoppen.

- De batterijduur kan verkort worden door de EM veldinterferentie.

- Over- en under-sensing in de CIED kunnen optreden ten gevolge van de EM velden en daarmee kan de therapie onderbroken worden of er kan juist zelfs een schok geven worden. Deze effecten worden beïnvloed door verschillende factoren, waaronder MRI veldsterkte (bepalend voor de RF frequentie), gebruikte MR pulssequentie, CIED karakteristieken en ook patiëntkarakteristieken zoals BMI, anatomie en weefselkarakteristieken.

- Verder is bekend dat de alarm waarschuwingsfuncties van de CIED (bijv. batterij bijna leeg alarm) door de pieper niet meer kunnen worden gesignaleerd. Uit vele studies is bekend dat CIED’s af en toe verstoord raken. Uit de literatuurstudie in deze richtlijn komt niet naar voren dat dit vaker zou gebeuren, nadat de CIED in en MRI is geweest dan wanneer de CIED niet in een MRI is geweest.

Voor MR-voorwaardelijke CIEDS zijn voorwaarden aan scanner instellingen gesteld door de leverancier, waardoor bovengenoemde risico’s na het volgen van deze voorwaarden minimaal zullen zijn. Voor patiënten met een CIED die niet MR voorwaardelijk is kunnen bovengenoemde risico’s niet geheel uitgesloten worden, echter zijn er in de literatuur geen duidelijke aanwijzingen gevonden dat het scannen van deze patiënten tot ernstige gevolgen voor de patiënt leidt. Er kan hierbij onderscheid gemaakt worden t.a.v. MRI-onderzoeken waarbij de CIED niet in het RF-veld komt en onderzoeken waarbij de CIED in het scangebied ligt en dus ook zeker de RF-velden ondergaat die tot opwarming kunnen leiden. Rekening moet hier ook worden gehouden met de duur van de scan – hoe langer de patiënt in een MRI-scanner ligt hoe warmer de elektroden kunnen worden. Vaak wordt in de handleiding van de CIED een maximale SAR in een maximaal tijdsinterval aangegeven waaronder opwarming in testcondities getest is. Het tijdsinterval geldt dan voor het achter elkaar scannen.

Voor achtergelaten transveneuze draden (eng: ‘abandoned leads’, d.w.z. afgescheurde, afgeknipte of afgedopte draden) is er beperkt bewijs dat MRI-onderzoeken veilig zijn. De kleine cohortstudies tonen ook niet aan dat het onveilig is, aangezien er geen verhoogd niveau van bijwerkingen werd waargenomen. Voor achtergelaten transveneuze leads zijn bij 1,5 T en een SAR van max 2 W/kg geen ernstige complicaties tijdens/na het MRI-onderzoek beschreven (Horwood 2018).

Voor epicardiale draden aangesloten aan een pacemaker worden bij 1,5 T en een SAR van max 2,5 W/kg geen ernstige complicaties tijdens/na het MRI-onderzoek beschreven. Achtergelaten epicardiale leads vormen een uitzondering in het geheel, deze draden kunnen veel warmer worden en een temperatuur van meer dan 60 graden werd waargenomen in een fantoom studie. De indicatie voor een MRI-onderzoek van patiënten met achtergelaten epicardiale leads moet zorgvuldig worden overwogen. Factoren die het opwarmeffect beïnvloeden zijn: a) magneetveldsterkte, b) SAR, c) thoracale of extra thoracale scans, d) duur van de scan, e) lengten van de draden. Indien de noodzaak van het MRI-onderzoek bij de individuele patiënt hoog is, wordt geadviseerd deze op 1,5 T uit te voeren.

In de consensusverklaring van de HRS (Indik 2017) wordt nog strikt geadviseerd geen achtergelaten draden in een MRI te scannen, echter nieuwere consensus statements, zie tabel 8, lijken geneigd hierin iets te versoepelen. Hier is het wederom van belang om de juiste afwegingen te maken tussen noodzaak van de scan en de risico’s ervan bij achtergelaten transveneuze draden en aangesloten epicardiale leads. De ESC richtlijn (Glikson 2021) gaat hierop in en geeft in het literatuuroverzicht aan dat achtergelaten draden kunnen opwarmen, maar dat er weinig bewijs ervan is in de in vivo setting, waarbij opgemerkt wordt dat effecten door opwarming niet direct meetbaar zijn en alleen ernstige klinische complicaties waargenomen kunnen worden.

In geval van verschillende fabrikanten voor CIED generator en lead (mix-brand) is in de literatuur weinig bewijsvoering gevonden, hoewel dit een veel voorkomend verschijnsel is (Levine 2007, Köning 2022). In dit geval is de combinatie niet MR voorwaardelijk. In een kleine retrospectieve single center studie (König 2022) is er geen verhoogd risico gevonden t.o.v. MRI voorwaardelijk pacemaker systemen. Ook eerdere studies, waarbij ook beperkte aantallen patiënten met verschillende fabrikanten van generator en lead waren beschouwd, vonden geen significant additionele risico’s (Shah 2017, Han 2019, Seewöster 2019). Ook in het HRS statement (Indik 2017) is dit geen exclusie van MRI. Vandaar de onderstaande aanbeveling om dit aspect mee te nemen in de risico afweging.

Externe pacemakers vallen buiten deze richtlijn, gezien het geen implantaat betreft. In het literatuuronderzoek zijn deze niet meegenomen. Zover bekend binnen de werkgroep zijn deze pacemakers niet MR voorwaardelijk, en is in de bestudeerde literatuur geen ervaring gevonden dat de risico’s beperkt zijn, zoals er wel die informatie is over de niet MR voorwaardelijk geïmplanteerde CIED’s. Tijdelijk, niet volledig geïmplanteerde, conventionele pacemaker systemen (transcutane lead met op de huid gefixeerde pacemaker), vallen ook buiten de richtlijn, ook als deze MRI voorwaardelijk zijn. De pacemakersystemen zijn in deze vorm in een MRI niet getest en de elektromagnetische interferenties bij niet volledig geïmplanteerde systemen kunnen afwijken. In de meeste gevallen wordt een externe pacemaker tijdelijk geplaatst voor korte duur, en is het aan te bevelen het MRI-onderzoek uit te stellen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten en hun naasten is het belangrijk dat zij samen met hun behandelaar een keuze kunnen maken om wel of niet een MRI-onderzoek te ondergaan (Samen beslissen). Om dat goed geïnformeerd te kunnen doen, is het van belang dat de voordelen van een MRI-onderzoek en de mogelijke risico’s besproken worden, zodat de patiënt kan begrijpen wat de gevolgen zijn van het gezamenlijke besluit om al dan niet een MRI-onderzoek te ondergaan. Voor patiënten is het ook belangrijk om te weten hoe ze erachter komen of een complicatie of risico zich voordoet, en wat eraan te doen is. Ter illustratie: bespreek het risico op een verkorte batterijduur, de manier waarop de resterende batterijduur gemeten wordt na het MRI-onderzoek, en de eventuele gevolgen en oplossingen indien er inderdaad een verkorting van de batterijduur optreedt. Zie hoofdstuk ‘risico-indeling hoofdklassen implantaten’ voor een overzicht van de te bespreken risico’s. In het stroomdiagram (figuur 1) is een beslismoment in samenspraak met de patiënt expliciet benoemd in geval van een niet-MRI-voorwaardelijke CIED.

Daarnaast is het van belang om het gehele proces herkenbaar uit te leggen, met andere woorden: wat kan de patiënt verwachten op welk moment? Benoem: het indicatiegesprek inclusief risico-afweging, de procedure (inclusief afsprakenreeks) op de dag van het MRI-onderzoek zelf, en de aanvullende meetmomenten van de CIED na afloop van het MRI-onderzoek.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Deze richtlijn zorgt niet voor hogere kosten, het geeft alleen een advies onder welke voorwaarden patiënten met een CIED toch een MRI-onderzoek kunnen krijgen. Het MRI-onderzoek wordt alleen uitgevoerd als dit in het belang is van de patiënt.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Deze richtlijn zorgt ervoor dat er een uniformer beleid gevoerd kan worden door ziekenhuizen waardoor er minder variaties komen tussen ziekenhuizen welke patiënten zij wel/niet scannen. De risico’s van het MRI-onderzoek zijn in de richtlijn benoemd en de MRI-veiligheidsexpert kan met behulp van deze richtlijn de zorgverleners adviseren over de veiligheid rond het uitvoeren van een MRI-onderzoek bij patiënten met een CIED. Deze richtlijn geeft een minimale set veiligheidsadviezen. Meer veiligheid bieden door bijvoorbeeld meer bewaking tijdens het MRI-onderzoek mag, maar wordt niet aanbevolen (‘het kan maar het moet niet’).

De implementatie van de richtlijn zal eenvoudig zijn omdat het een versoepeling is van het huidige beleid.

De aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van beleid rondom MRI bij patiënten met CIED’s is niet kwalitatief of kwantitatief onderzocht. Er worden geen problemen voorzien met de aanvaardbaarheid van deze richtlijn, aangezien de aanbeveling grotendeels is gebaseerd op de huidige praktijk.

Figuur 1. Beslisschema voor patiënt met pacemaker of ICD.

Aanbeveling 1

Rationale van de aanbeveling:

Bij MR-voorwaardelijke CIED’s wordt geadviseerd volgens de instructies van de fabrikant te scannen. Indien dit niet mogelijk is of indien het een niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED betreft moet een risico-baten afweging plaatsvinden. Voor epicardiale draden raadt de werkgroep aan alternatieve beeldvorming sterk te overwegen. Voor achtergelaten transveneuze draden lijken geen harde contra-indicatie te zijn voor MRI-onderzoek, mits het voordeel van MRI opweegt tegen het potentiële risico van opwarming èn de lead zich in een goed doorbloed weefsel bevindt. Eventuele risico's kunnen verlaagd worden door te scannen op 1,5 T en met zo laag mogelijke SAR.

Bij een MRI-onderzoek waarbij de CIED in het af te beelden gebied komt te liggen is het belangrijk om een afweging te maken om te bepalen of vooraf ingeschat kan worden of de beeldkwaliteit goed genoeg zal zijn voor diagnostiek. Indien de verwachting is dat deze dusdanig gecompromitteerd is dat deze onvoldoende zal zijn dan is een MRI af te raden, zeker als het een niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED betreft.

Aanbeveling 2

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Voor het scannen van een patiënt met een CIED moet een instelling een aparte procedure hebben met een gestandaardiseerde workflow. Indien mogelijk wordt de CIED in een MRI veilige modus gezet gedurende het MRI-onderzoek.

- Bij een MR-voorwaardelijke CIED is altijd een MR-veilige modus in te stellen.

- Bij een niet-MR-voorwaardelijke CIED: een pacemaker programmeren in veilige modus (op advies cardioloog) en de ICD functie uitprogrammeren.

- Test na het MRI-onderzoek de magneetfunctie, de pieper (waarschuwingssignaal), de batterij, etc. door een pacemaker/ICD technicus.

- Meet voorafgaand aan het MRI-onderzoek de device- en lead-functie (waaronder impedantie) om zeker te zijn dat de pacemaker/defibrillator juist functioneert.

- Leg in een procedure vast wat te doen bij een calamiteit, en hoe personeel hierin getraind is.

Aanbeveling 3

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Tijdens scannen is ritmebewaking noodzakelijk bij patiënten die pacemaker afhankelijk zijn.

Ritmebewaking is te overwegen bij niet-pacemaker afhankelijkheid indien de CIED in veilige modus gezet kan worden. Door de veilige modus is de kans op incidenten zo klein, is de ervaring uit de laatste jaren, dat ritme bewaking niet noodzakelijk is.

Ritme bewaking is noodzakelijk voor alle patiënten met een implanteerbare cardioverter/defibrillator (ICD). Ritme bewaking is noodzakelijk voor alle patiënten met een implanteerbare cardioverter/defibrillator (ICD). Patiënten met een ICD zijn per definitie afhankelijk van hun device om een mogelijk levensbedreigende ritmestoornis op te sporen en te corrigeren. De MRI modus van de ICD schakelt beide functies van het apparaat uit. Derhalve is continue ritmebewaking is essentieel om tijdig een ritmestoornis op te sporen en eventueel over te kunnen gaan tot defibrillatie.

Ritmebewaking middels pulsoxymetrie is te prefereren boven ECG bewaking, gezien het ECG signaal verstoord wordt door de signalen die opgewekt worden bij het acquireren van de MRI-scan. Daarnaast wordt het ECG signaal verstoord door het statisch magnetisch veld middels het magnetohydrodynamisch effect (Jekic 2010). Voor de volledigheid: ECG-apparatuur die aanwezig is bij de MRI-scanner (voor de ECG synchronisatie van de MR acquisitie) is in de regel niet vrijgegeven voor ritmebewaking.

Bij het scannen van een ICD en/of pacemaker afhankelijke patiënt moet personeel met spoed oproepbaar zijn om een reanimatie uit te kunnen voeren (conform leidraad vitaal bedreigde patiënt) en om de CIED te kunnen programmeren.

Aanbeveling 4

Rationale van de aanbeveling:

De meeste loop recorders zijn MR voorwaardelijk. Er is één model buiten de EU op de markt die MR onveilig is (Angelmed Guardian).

Het advies is om bij bepaalde modellen loop recorders (zie tabel 10) deze voorafgaand aan het MRI-onderzoek uit te laten lezen indien dit niet dagelijks automatisch gebeurd m.b.v. een ‘home monitor’. Dit om te voorkomende dat er geen belangrijke data voor de zorgverlening verloren gaat tijdens het MRI-onderzoek.

Na het MRI-onderzoek is het advies om de recorder te controleren, omdat er vaak veel MRI geïnduceerde ruis episoden worden opgeslagen. Meestal kan dat via remote monitoring en dit behoeft niet acuut te gebeuren.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Steeds meer patiënten hebben een pacemaker of een implanteerbare cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). Veel nieuwe systemen zijn MR voorwaardelijk, en kunnen dus onder bepaalde condities gescand worden. Er is echter ook nog een grote groep patiënten die een pacemaker/ICD hebben die niet MR voorwaardelijk is. Recent (2021) zijn nieuwepacemaker-richtlijnen van de European Society of Cardiology (ESC) verschenen waarin ook aanbevelingen voor MRI-onderzoeken worden gegeven. Deze module is enerzijds een vertaling van bestaande internationale richtlijnen naar de Nederlandse situatie. Anderzijds is er behoefte aan advies in beleid hoe wordt omgegaan met elektronische cardiale implantaten die niet MR voorwaardelijk zijn gesteld door de fabrikant. Tenslotte is er een steeds grotere groep patiënten die achtergelaten pace-draden hebben, en de vraag is wat voor die patiënten het beste beleid is.

Naast pacemakers en ICD zijn de loop recorders de derde groep van elektronische cardiale implantaten. MR voorwaarden voor deze implantaten zijn eenvoudiger, en worden voor de volledigheid in deze module meegenomen.

Conclusies

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MRI on adverse events when compared with no MRI in patients with CIEDs.

Sources: Ching (2017), Seewoster (2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of 3.0T MRI on adverse events when compared with 1.5T MRI in patients with CIEDs.

Sources: Van Dijk (2017), Blessberger (2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MRI on adverse events in patients with MRI unconditional devices when compared with patients with MRI conditional devices.

Sources: Munawar (2020), Bhuva (2021), Han (2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of MRI on adverse events in patients with abandoned leads when compared with patients with no abandoned leads.

Sources: Padmanabhan (2018) |

Samenvatting literatuur

The consensus statement of Indik (2017) was taken as the starting point. Furthermore, four studies were found comparing MRI with no MRI, and 1.5T MRI with 3T MRI in patients with CIEDs. There were four studies comparing types of CIEDs.

Indik (2017) published an international consensus statement article containing recommendations for health care professionals who have patients with CIEDs undergoing MRI scanning, CT scanning or radiation treatment. It is written by experts from the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and eleven collaborating societies. A search was done in Medline, Embase and Cochrane libraries. The class of evidence and level (quality) of evidence was reviewed. RCTs, nonrandomized observational studies (retrospective or prospective) and case studies were considered evidence. Computational modeling studies, and other ex vivo studies were only used as support of the evidence. In total, 15 studies were included for MR conditional devices, and 21 studies for MR unconditional devices.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published a guideline in 2021 on cardiac pacing with contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. In this guideline, a section on MRI in patients with implanted devices is included, also using Indik (2017) as starting point, and extending this with a paragraph on abandoned and pericardial leads. The class of evidence and level (quality) of evidence was reviewed.

Description of studies

- MRI vs no MRI

Ching (2017) conducted a prospective, multicenter, randomized study to study the safety and efficacy of the Accent MRITM conditional pacing systems (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) in patients undergoing cMRI scan. Patients were included if they had dual-chamber pacemaker implant: Accent MRITM DR 2124 (dual-chamber pulse generator) or Accent MRITM DR 2224 (dual-chamber pulse generator with RF telemetry) and were ≥18 years old. Patients were excluded if they had permanent atrial fibrillation or flutter, were medically contraindicated to undergo an MRI scan, or had pre-existing leads. In total, 140 patients (mean age: 71 ± 11 years, 82 (59%) male) were included in the intervention group (1.5T MRI General Electric (Boston, MA, USA), Siemens (Munich, Germany), and Philips (Amsterdam, the Netherlands)), and 143 patients (mean age: 67 ± 12 years, 82 (57%) male) were included in the control group (no MRI). Follow up was one month after MRI. Outcome measures of interest were complications related to device and procedure.

Seewoster (2019) performed a study on a prospective registry to investigate the effect of MRI in patients with CIEDs, in Germany. Patients were included if MR conditional or non-MR conditional pacemaker (PM), implantable loop recorder (ILR), ICD, or cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D), undergoing clinically indicated MRI. Patients were excluded if the device was implanted within the last 6 weeks, if they had epicardial, abandoned or fractured leads, or if they had any general contraindications for CMR imaging. In total, 200 patients (mean age: 64 ± 14 years, 141 (70%) male) were included in the intervention group (1.5T MRI Philips Ingenia, Best, The Netherlands) and 2487 patients (mean age: 65 ± 12 years, 1666 (67%) male) were included in the control group (no MRI). Follow up on intervention group was 6 months. Outcomes of interest include clinical evens.

- 1.5T MRI vs 3T MRI

Blessberger (2019) conducted a prospective non-randomized, single center interventional trial to study the feasibility study of the MRI compatibility of a leadless pacemaker system, in a university hospital in Austria. Patients were included if they had a Micra leadless pacemaker system (Medtronic Inc., MN, USA) implanted more than 6 weeks ago, if they were ≥18 years old, had stable pacing thresholds and ≤2.0 V at 0.24 ms pulse width, had pacing impedances between 200 and 1500 Ohms and had calculated battery life >8 years (=100%). Patients were excluded if they had a life expectancy <12 months, had scheduled cardiac surgery within 3 months, had glomerular filtration rate ≤30 mL/min/1.73 m2, were pregnant or if they had any other medical devices that may interact with the pacemaker. In total, 7 patients were included in the intervention group and 7 were included in the control group (total mean age: 77 ± 14, 12 males). Patients in the intervention group underwent 1.5 T MRI (Magnetom AvantoVR, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), while patients in the control group underwent 3 T MRI (Magnetom SkyraVR, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Follow up was 3 months. Outcomes of interest include Serious Adverse Device Effects (SADEs), pacing threshold, R-wave sensing, impedance and battery life.

Van Dijk (2017) performed two prospective, non-randomized, single-arm studies to investigate the impact of MRI on device function, lead parameters, and patient conditions in subjects with CIEDs, in two sites in the Netherlands, from June 2013 to January 2014 and August 2015 to July 2016. Patients were included in the intervention group (3 T MRI) or the control group (1.5 T MRI) if they had an ImageReady MR Conditional Pacing System, single or dual chamber and were ≥18 years old. Patients were excluded if they had pulse generator location outside of left or right pectoral regions, other cardiac-related devices or accessories other than the ImageReady System, abandoned leads or pulse generators, evidence of a fractured lead or compromised system integrity, low life expectancy (<1 year), or severe comorbidities that posed patient at risk to undergo MRI. In total, 20 patients (mean age ± sd: 67 ± 13, 13 (76%) male) were included in the control group (1.5T MRI Magnetom AvantoVR, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany); and 17 patients (mean age: 72 ± 12 years, 13 (65% male) were included in the intervention group (3T MRI Magnetom SkyraVR, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Follow up was one month after MRI scan. Outcomes of interest were adverse events, and device parameters.

- MRI conditional vs nonconditional devices

One systematic review (Munawar 2020) and two comparative studies (Bhuva 2021, Han 2019) were included for this analysis.

Munawar (2020) performed a systematic review to investigate the effect of MRI scanning on non-conditional CIEDs. On December 5th, 2018, PubMed, EMBASE and CINAHL were searched with ‘magnetic resonance imaging’ AND ‘pacemaker’ OR ‘implantable cardioverter defibrillator’ OR ‘cardiac resynchronization therapy’. Articles were included if they were in English, were human studies, reported on adverse events and enrolled patients with non-compatible CIEDs undergoing MRIs. Articles were excluded if the size was n<10, if they were case studies or if the conditionality of the CIED was not reported. The search resulted in 4609 deduplicated hits, of which 35 met inclusion criteria. All of the 35 studies were cohort studies, including 5625 patients and 7196 MRI scans. 31 of the 35 studies performed 1.5 T MRIs (n=5518), 3 studies performed >1.5T MRIs (n=561) and one study performed both (n=29). In total, there were 2622 atrial pacing leads, 3124 right ventricular pacing leads, 289 left ventricular pacing leads, and 1851 defibrillator leads. The MRIs were performed on head and neck (39%), spinal (17%), and abdomen/pelvis regions (12%).

Bhuva (2021) performed a prospective, multicenter study to study the effect of MRI on patients with non-conditional and conditional pacemaker and defibrillator leads, in the UK and the USA. All patients with pacemakers and defibrillators undergoing MRI (including patients with abandoned leads, recent implant, manufacturer date before 2001, etc) were included. No exclusion criteria were mentioned. In total, 462 patients (median age 65 (IQR 50, 75) underwent 533 scans with MRI conditional devices, and 50 patients (median age 73 (IQR 65, 79) underwent 615 scans with non-conditional devices. CIED interrogation and reprogramming took place immediately before MRI. All patients underwent 1.5 T MRI (Aera, Avanto, Avanto Fit, Espree; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Follow up was determined by clinical protocols. Outcomes of interest include adverse events, and lead parameter changes.

Han (2019) conducted a single center retrospective study to investigate interrogation data and outcomes of patients with pacemakers or implantable cardioverter defibrillators who underwent MRI, from September 2013 until December 2015 in Korea. All patients with pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) undergoing clinically indicated MRIs were included. Patients were excluded if they underwent MRI without a cardiology consult. In total, 14 patients (mean age: 71 ± 20 years) with conditional devices (n=14 (100%) pacemaker) undergoing 16 scans, and 21 patients (mean age: 70 ± 13 years) with non-conditional devices (n=14 , 66.7%) pacemaker) undergoing 27 scans were included. All patients underwent 1.5 T MRI. CIED reprogramming took place immediately before MRI. Length of follow up was 5.4 months (range 0.1-13.8). Outcomes of interest include adverse events, change and mean lead impedance, sensing and capture threshold.

- Patients with abandoned leads versus without abandoned leads

Padmanabhan (2018) performed a retrospective study of a prospective database to investigate the safety of MRI in patients with legacy pacemakers and defibrillators and abandoned leads, in the USA from 2008-2017. Patients were included in the intervention group if they had legacy non–MRI-conditional systems with abandoned leads in situ. Patients were included in the matched control group if they had legacy non–MRI-conditional systems without abandoned leads in situ. Matching occurred by age, sex, and site of MRI. In total, 80 patients (mean age 66, Q1 54, Q3 76) were included in the intervention group, undergoing 97 scans. 91 patients were included in the matching cohort (similar age due to matching). All patients received 1.5T MRI, SAR did not exceed 1.5 W/kg. Outcome of interest were adverse events, and device characteristics before and after imaging.

Results

Results are presented per comparison. Observational, noncomparative studies are reported separately in ‘Bijlage 1’.

In the HRS statement by Indik (2017) the following recommendations were given:

Table 1. MR conditional devices (Indik 2017).

|

Class of recommendation (COR) |

Level of evidence |

Recommendation |

|

I |

A |

MR conditional devices should be considered MR conditional only when the product labeling is adhered to, which includes programming the appropriate “MR mode” and scanning with the prerequisites specified for the device. |

|

I |

B-R |

MR imaging in a patient with an MR conditional system should always be performed in the context of a rigorously applied standardized institutional workflow, following the appropriate conditions of use. |

|

I |

B-R |

It is recommended for patients with an MR conditional system that personnel with the skill to perform advanced cardiac life support, including expertise in the performance of CPR, arrhythmia recognition, defibrillation, and transcutaneous pacing, be in attendance with the patient for the duration of time the patient’s device is reprogrammed, until assessed and declared stable to return to unmonitored status. |

|

I |

A |

It is recommended for patients with an MR conditional system that ECG and pulse oximetry monitoring be continued until baseline, or until other clinically appropriate CIED settings are restored. |

|

I |

C-EO |

All resuscitative efforts and emergency treatments that involve the use of a defibrillator/monitor, device programming system, or any other MRI-unsafe equipment should be performed after moving the patient outside of Zone 4. |

|

I |

C-EO |

It is recommended for patients with an MR conditional system that personnel with the skill to program the CIED be available as defined by the institutional protocol. |

|

IIa |

C-EO |

It is reasonable to perform an MR scan on a patient with an MR conditional system implanted more recently than the exempt period for conditionality of the system, based on assessment of risk and benefit for that patient. |

I = strong recommendation; IIa = moderate recommendation; A = high quality of evidence; B-R = moderate quality of evidence, randomized; C-EO = consensus of expert opinion based on clinical practice

Table 2. MR unconditional devices (Indik 2017).

|

Class of recommendation |

Level of evidence |

Recommendation |

|

IIa |

B-NR |

It is reasonable for patients with an MR nonconditional CIED system to undergo MR imaging if there are no fractured, epicardial, or abandoned leads; the MRI is the best test for the condition; and there is an institutional protocol and a designated responsible MR physician and CIED physician. |

|

IIa |

B-NR |

It is reasonable to perform an MR scan immediately after implantation of a lead or generator of an MR nonconditional CIED system if clinically warranted. |

|

IIa |

C-LD |

For patients with an MR nonconditional CIED, it is reasonable to perform repeat MRI when required, without restriction regarding the minimum interval between imaging studies or the maximum number of studies performed. |

|

I |

B-NR |

It is recommended for the patient with an MR nonconditional CIED that device evaluation be performed immediately pre- and post-MRI with documentation of pacing threshold(s), P- and R-wave amplitude, and lead impedance using a standardized protocol. |

|

I |

B-NR |

A defibrillator/monitor (with external pacing function) and a manufacturer-specific device programming system should be immediately available in the holding area adjacent to the MR scanner room while an MR nonconditional CIED is reprogrammed for imaging. |

|

I |

B-NR |

It is recommended that continuous MR conditional ECG and pulse oximetry monitoring be used while an MR nonconditional CIED is reprogrammed for imaging |

|

I |

B-NR |

It is recommended that personnel with the skill to perform advanced cardiac life support, including expertise in the performance of CPR, arrhythmia recognition, defibrillation, and transcutaneous pacing, accompany the patient with an MR nonconditional CIED for the duration of time the patient’s device is reprogrammed, until assessed and declared stable to return to unmonitored status. |

|

I |

B-NR |

For patients with an MR nonconditional CIED who are pacing-dependent (PM or ICD), it is recommended that: a) Personnel with the skill to program the CIED be in attendance during MR scanning. b) A physician with the ability to establish temporary transvenous pacing be immediately available on the premises of the imaging facility. c) A physician with the ability to direct CIED programming be immediately available on the premises of the imaging facility. |

|

I |

B-NR |

For patients with an MR nonconditional CIED who are not pacing-dependent, it is recommended that: a) Personnel with the skill to program the CIED be available on the premises of the imaging facility. b) A physician with the ability to direct CIED programming be available on the premises of the imaging facility. |

|

I |

B-NR |

It is recommended that for the patient with an MR nonconditional CIED who is pacing-dependent to program their device to an asynchronous pacing mode with deactivation of advanced or adaptive features during the MRI examination, and the pacing rate should be selected to avoid competitive pacing. |

|

I |

B-NR |

All tachyarrhythmia detections for patients with an ICD should be disabled prior to MRI. |

|

I |

C-EO |

The MR-responsible physician who is accountable for overseeing the safety of the MRI environment, including the administration of any medication and/or contrast agents (if applicable), should be made aware of the presence of a patient with an MR nonconditional CIED. |

|

I |

C-EO |

It is recommended that ECG and pulse oximetry monitoring be continued until baseline or until other clinically appropriate CIED settings are restored for patients with an MR nonconditional CIED. |

|

I |

C-EO |

All resuscitative efforts and emergency treatments that involve the use of a defibrillator/monitor, device programming system, or any other MRI-unsafe equipment should be performed after moving the patient outside of Zone 4. |

|

IIa |

B-NR |

For a patient with an MR nonconditional CIED who is not pacing-dependent, it is reasonable to program their device to either a nonpacing mode (OVO/ODO) or to an inhibited mode (DDI/VVI), with deactivation of advanced or adaptive features during the MRI examination. |

|

IIa |

C-EO |

It is reasonable to program patients with an MR nonconditional CRT device who are not pacing-dependent to an asynchronous pacing mode (VOO/DOO) with deactivation of advanced or adaptive features during the MRI examination, and with a pacing rate that avoids competitive pacing. |

|

IIa |

C-EO |

For patients with an MR nonconditional CIED, it is reasonable to schedule a complete follow-up CIED evaluation within 1 week for a pacing lead threshold increase ‡1.0 V, P-wave or R-wave amplitude decrease ‡50%, pacing lead impedance change ‡50 U, and high-voltage (shock) lead impedance change ‡5 U, and then as clinically indicated. |

I = strong recommendation; IIa = moderate recommendation; A = high quality of evidence; B-R = moderate quality of evidence, randomized; B-NR = moderate quality of evidence, nonrandomized; C-LD = limited data, observational; C-EO = consensus of expert opinion based on clinical practice

Table 3. Implantable loop recorder (Indik 2017).

|

Class of recommendation |

Level of evidence |

Recommendation |

|

I |

B-NR |

It is recommended that prior to MRI scanning patients with an implantable loop recorder (ILR) that the ILR be evaluated and that any desired recorded information be removed/downloaded from the system and cleared after the MRI. |

|

I |

C-LD |

MR scanning of MR conditional ILRs should be performed within labeled scanning prerequisites specific to each device manufacturer. |

I = strong recommendation; B-NR = moderate quality of evidence, nonrandomized; C-LD = limited data, observational

- MRI vs no MRI

Ching (2017) reported 12 adverse events that were procedure or device related. Of those, none were MRI related, since the events all occurred before the MRI took place. N=1 anaphylaxis/anaphylactoid, n=1 drug allergy, n=1 intracranial haemorrhage, n=1 pericardial effusion, n=1 RV lead dislodgement, and n=1 ventricular tachycardia requiring emergent direct current cardioversion. In the control group, 6 adverse events were reported: n=1 acute non-ST elevation MI, n=1 cardiac tamponade, n=1 Dressler's syndrome, n=2 RA lead dislodgement, and n=1 system infection. Seewoster (2019) reported one adverse event that was device or MRI related. They reported: n=3 (2.8%) ventricular tachycardia during imaging (not device or MRI related) (all ICD), and n=1 generator failure requiring immediate replacement (0.95%) (ICD). N=12 (6%) had impaired image quality.

- 1.5T MRI vs 3T MRI

Van Dijk (2017) reported 10 adverse events, but no adverse events were related to the MRI, therefore, these were excluded and the number of adverse events due to MRI scanning was 0 (0%, n=37). Blessberger (2019) also did not report any adverse events (0%, n=14).

- MRI conditional vs nonconditional devices

Few adverse events were reported in the comparison between MR-conditional devices versus non-MRI-conditional devices. One event (0.2%) of urgent generator replacement due to fault code of battery (ICD and leads) was reported in the non-conditional group (Bhuva, 2021, total scans non-conditional 615). Tachycardia and chest tightness (ICD + leads) was reported in one case (Bhuva 2021). Eight cases (1.5%) of ICD generator audible alarms were reported in the conditional group (Bhuva 2021, total scans conditional 533). This was regarded as an issue by the manufacturer and required no further action. In the study of Han (2019) no adverse events were reported (total of 43 scans).

Adverse events reported for non-conditional CIED’s in Munawar (2020) related to MRI and related to the CIED are summarized in table 4 and table 5. Munawar et al. included scientific studies from 2000 up to 2018, meaning that the CIEDs in the oldest included study were implanted in the years before 2000 and may not be representative for present-day CIEDs .

Table 4. Overview of adverse events with non-conditional CIED’s related to the MRI scanner reported in Munawar (2020).

|

Adverse event related to MRI |

N studies |

N events |

N total |

Incidence (95% CI) |

|

MRI related death |

9 |

0 |

2122 |

0% |

|

Symptom of heating or torque |

25 |

19 |

4531 |

0.71% (0.35-1.18) |

|

Electrical reset |

25 |

76 (all in older devices) |

4896 |

1.43% (0.64–2.54) |

|

Lead failure |

15 |

1 |

3995 |

0.07% (NR) |

|

Generator failure |

15 |

2 |

3995 |

0.14% (0.05–0.28) |

|

Inappropriate pacing |

16 |

6 |

2772 |

0.37% (0.09–0.53) |

|

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks |

10 |

0 |

911 |

0% |

Table 5. Overview of adverse events related to non-conditional CIED’s reported in Munawar (2020).

|

CIED parameter changes |

N studies |

N events |

N leads |

N patients |

Incidence (95% CI) |

|

Lead threshold |

12 |

|

3604 |

|

|

|

≥0.5 V |

6 |

32 |

3388 |

1577 |

1.1% (0.7–1.8%) |

|

≥1.0 V |

4 |

8 |

684 |

382 |

1.0% (0.1–2.9%) |

|

≥50% |

2 |

32 |

3915 |

1645 |

1.1% (0.2–2.8%) |

|

Lead impedance |

8 |

|

3284 (7713 leads) |

|

|

|

>50 Ω >50% in low voltage devices |

5 3 |

134 0 |

3354 4359 |

1476 1808 |

4.8% (3.3–6.4%) 0% |

|

>3 Ω In high voltage devices |

5 |

132 |

727 MRIs |

658 |

22.4% (13.7–32.5%) |

|

P-wave sensing (decrease ≥50%) |

6 |

35 |

2883 |

3274 |

1.5% (0.6–2.9%) |

|

R-wave sensing (decrease ≥50%) |

5 |

12 |

3515 |

3165 |

0.4% (0.06–1.1%) |

|

Battery voltage drop voltage drop of >0.04 V |

5 |

32 |

- |

1453 |

2.2% (0.2–6.1%) |

- Patients with abandoned leads versus without abandoned leads

Padmanabhan (2018) reported no adverse events, no complications, no inappropriate pacing, and no power-on-reset in either the patients with abandoned leads or the patients without abandoned leads undergoing MRI.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events started at Low because of the observational design and was downgraded by 1 level to Very Low because of number of included patients (imprecision).

Overige bronnen van informatie gebruikt voor deze richtlijn:

Samenvatting informatie uit incidentdatabases van implantaten.

Voor deze module zijn de volgende incidentdatabases van implantaten doorzocht:

-

- de database van de Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd (IGJ) met veiligheidsmeldingen vanaf 15 december 2015;

- het archief van Inspectie Gezondheidszorg (IGZ);

De zoekverantwoording in deze databases is te vinden in de tabel ‘Zoekverantwoording Databases van Recalls en Events’. In geen van deze databases zijn meldingen gevonden die relevant zijn voor deze richtlijn module.

Voor deze module is besloten om de FDA-incidentdatabases niet te doorzoeken. Oude incidentdatabases (>10 jaar oud) hebben beperkte waarde gezien deze implantaten typisch niet langer dan 10 jaar geïmplanteerd blijven, op leads na. Daarnaast zijn er meerdere grote studies die systematisch hebben gekeken naar de effecten van MRI op deze implantaten (Ching, 2017; Seewoster, 2019; Munawar, 2020; Van Dijk, 2017; Blessberger, 2019), en daardoor een betere inschatting geven van kans op bepaalde complicaties; iets wat in een incidentdatabase lastiger te bepalen is.

Samenvatting van de studies over abandoned leads, epicardial leads

Deze studies zijn samengevat in tabel 6 en 7, en in tabel 8 worden de consensuspaper over dit onderwerp vermeld.

Table 6. Overview non-comparative in vivo studies on abandoned or epicardial leads.

|

Author, year |

Methods |

N |

MRI scanner type |

SAR limits |

Gradient limits |

Results |

|

Gatterer 2021 |

Prospective cohort |

19/88 with temporary pacing wire

55 CMR MRI scan sessions |

1.5T CMR scanner (Avanto Fit, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) |

Normal operation mode: 2w/kg and First level: 4w/kg. (system specification) |

Maximum gradient strength of 45 mT/m and a maximum slew rate of 200 T/m/s. (system specification) |

No serious adverse event, such as arrhythmias, self-reported heating of the pacing wires, or severe pain.

One patient, with a C-shaped temporary pacing wire in situ, described a sensory event near the subcutaneous end of the retained lead during the second CMR. |

|

Morris 2018 |

Retrospective study |

231 patient, 251 MRI scans, 9 MRI scans for patients with abandoned leads |

1.5 T MRI scanner (Signa HD, GE) |

< 2 W/kg (target) |

Not mentioned |

No adverse events during or immediately after MRI, and there were no significant changes in the impedance or threshold of the connected leads.

No significant differences in impedance and threshold values in patients with abandoned leads compared to patients with CIEDs and intact leads. |

|

Nyotowidjojo 2018 |

Prospective study |

N=238, of which: Abandoned leads, n=6, Epicardial leads n=7 |

1.5T system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Magnetom Aera, Erlangen, Germany) |

Not mentioned. |

45 mT/m gradient strength, slew rate of 200 T/m/s

(system specification) |

For patients with abandoned or epicardial leads: MR scans were completed with no adverse events |

|

Vuorinen 2022 |

Retrospective cohort |

26 MRI scans on 17 patients with functioning or abandoned leads.

MRIs have been conducted following institutional MRI with CIED safety protocol (Vuorinen, 2019)

n=10 MRIs with abandoned epicardial leads, n = 5 MRIs with functioning endocardial and abandoned epicardial leads n = 5 MRIs with functioning epicardial and abandoned epicardial leads n = 3 MRIs with abandoned PM with epicardial leads n = 1 MRIs with abandoned PM with epicardial leads |

1.5T system (Siemens MAGNETOM Avanto or Siemens MAGNETOM Avantofit, both from Siemens Healthcare) |

Not mentioned |

Not mentioned |

1 AE detected for patient with old functioning epicardial pacing leads and abandoned epicardial pacing leads. |

|

Horwood 2017 |

Prospective cohort |

142 consecutive patients with a CIED.

106 patients had an implanted cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) and 36 patients had an implanted pacemaker.

A total of 46 out of 142 patients (32%) had either absolute contraindications for MRI [abandoned leads, pacemaker dependent with implanted ICD, battery depletion, or recent CIED implants] or had recalled CIED devices or leads.

There was a total of 12 abandoned leads in 10 patients, including 7 pacing leads located in the coronary venous system (n = 2), epicardium (n = 3), right atrium (n = 1), and right ventricular apex (n = 1). There were 5 abandoned ICD leads, including dual coil leads (n = 4), and a coil in the superior vena cava (n = 1).

|

1.5 Tesla MRI scanner (Signa Excite CV/i, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) |

For cardiac MRI: ≤2 W/kg |

Not mentioned |

No adverse events occurred during the MRI in the patients with abandoned leads. None of the patients with abandoned leads had chest discomfort during the scanning procedure.

NB: one incident was reported in the control group. In one pacemaker-dependent patient, the heart rate dropped during a fast spin-echo pulse sequence from 90 to 50 b.p.m. corresponding to the noise reversion rate of the ICD (Ellipse, St. Jude Medical).

|

Table 7. Overview non-comparative ex vivo and in vitro studies on abandoned or epicardial leads.

|

Author, year |

Methods |

N |

MRI |

SAR limits |

Gradient limits |

Results |

|

Balmer 2019 |

In vitro phantom study |

2 lead types

transvenous lead (5086—45 cm, Medtronic)

epicardial lead (4968—35 cm, Medtronic)

with and without connection to an MR-conditional pacemaker |

1.5T MRI scanner (Achieva, Philips) |

2 W/kg (aim) |

Not mentioned |

(1) A temperature rise of +2.5 °C was observed for the transvenous lead attached to an MRI-conditional pacemaker. The epicardial lead attached to the same pacemaker showed four times higher heating. (2) The transvenous lead without pacemaker showed four times higher heating, and the epicardial lead without pacemaker showed 30 times higher heating. (3) The epicardial lead coiled to 20 cm length without pacemaker showed 9 times higher heating. (4) Experiments with various lengths of epicardial leads showed that the shorter the leads were, the smaller was the heating effect |

Table 8. Consensus articles on abandoned, fractioned or epicardial leads.

|

|

Organization |

Consensus statement |

|

Almeida 2021 |

Portuguese Society of Cardiology and the Portuguese Society of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine |

Exclude the presence of abandoned leads or additional components, such as adapters and lead extensions. |

|

Dacher 2020 |

French Society of Cardiology (SFC) and the Société française d'imagerie cardiaque et vasculaire diagnostique et interventionnelle (SFICV) |

However, we think that these data are insufficient to recommend MRI in these cases and that the presence of epicardial, fractured, or abandoned leads should remain a contraindication for MRI. In individual cases with a life-threatening emergency, non-thoracic MRI can be discussed in nonpacing-dependent patients after careful consideration of the benefit/risk ratio and multidisciplinary discussion. |

|

Patterson 2021 |

Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance /Canadian Heart Rhythm Society |

For patients with a previous CIED undergoing MRI, we recommend reviewing all available medical information, including chest radiography, to identify lead extenders, retained epicardial leads, abandoned transvenous leads, and/or fractured leads. We recommend that patients with lead extenders or fractured leads should not undergo MRI. However, MRI might be considered in patients with epicardial or abandoned transvenous leads when the clinical need is strong and believed to outweigh potential risks (Weak Recommendation; Low-Quality Evidence). |

|

Jabehdar Maralani 2020 |

A group of 10 radiologists, from nine high-volume academic institutions. Delphi approach. |

Previous guidelines and consensus documents state that abandoned intracardiac and epicardial leads are MR Unsafe; however, studies show that they may be considered MR Conditional at 1.5T. The presence of abandoned or fractured intracardiac leads is not an absolute contraindication to MRI at 1.5T. |

|

Vigen 2021 |

International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) |

The patient should not have any abandoned leads (but see Note (A) below). Note (A): These guidelines do not address imaging in patients with abandoned leads or retained lead fragments, as minimal data are available. |

Summary

- There is limited evidence that MRI scans with abandoned leads are safe. The small cohort studies do not show that it unsafe either as no elevated level of Adverse Events was observed.

- There is limited evidence about safety of MRI scans with epicardial leads.

- SAR and gradient constraints are not systematically mentioned. For the studies which do mention constraints, SAR ≤ 2 W/kg was used.

- Consensus statements released after the Indik paper tend to loosen the strict exclusion criterion for abandoned leads.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the chance of negative events in patients with electronic cardiac implants undergoing an MRI?

P: Patients with electronic cardiac implants.

I: MRI investigation.

C: No MRI investigation, adapted MRI investigation.

O: Negative effects: harmful effects on the patient because of interactions between the implants and the MRI scanner generated magnetic fields and radiofrequent waves.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered negative effects as a critical outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the GRADE-standard limit of 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25), and 10% for continuous outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 1-1-2017 until 7-6-2022. The consensus statement and review by Indik (2017) was used as starting point for the search. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 902 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria reporting on Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIEDs), MRI and adverse effects. 138 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 110 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 8 comparative studies were included. Furthermore, we included non-comparative studies if they had a size of n=10 or larger and reported on adverse events in patients with vascular stents undergoing MRI scanning. 20 non-comparative studies were included. We excluded ex vivo and non-human studies. Guidelines were also selected, and an overview is presented in “overwegingen”.

Results

Nine studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. For evidence and risk of bias table of included studies from the systematic review, please see the article and supplementary of Munawar (2020) and Indik (2017).

Referenties

- Almeida AG, António N, Saraiva C, Ferreira AM, Reis AH, Marques H, Ferreira ND, Oliveira M. Consensus document on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac implanted electronic devices. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2021;40:41-52. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2020.05.009.

- Balmer C, Gass M, Dave H, Duru F, Luechinger R. Magnetic resonance imaging of patients with epicardial leads: in vitro evaluation of temperature changes at the lead tip. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2019;56:321-326. doi: 10.1007/s10840-019-00627-7.

- Bauer WR, Lau DH, Wollmann C, McGavigan A, Mansourati J, Reiter T, Frömer S, Ladd ME, Quick HH. Clinical safety of ProMRI implantable cardioverter-defibrillator systems during head and lower lumbar magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5 Tesla. Sci Rep 2019;9:18243. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54342-4.

- Bhuva AN, Kellman P, Graham A, Ramlall M, Boubertakh R, Feuchter P, Hawkins A, Lowe M, Lambiase PD, Sekhri N, Schilling RJ, Moon JC, Manisty CH. Clinical impact of cardiovascular magnetic resonance with optimized myocardial scar detection in patients with cardiac implantable devices. Int J Cardiol. 2019;279:72-78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.01.005.

- Bhuva AN, Moralee R, Brunker T, Lascelles K, Cash L, Patel KP, Lowe M, Sekhri N, Alpendurada F, Pennell DJ, Schilling R, Lambiase PD, Chow A, Moon JC, Litt H, Baksi AJ, Manisty CH. Evidence to support magnetic resonance conditional labelling of all pacemaker and defibrillator leads in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Eur Heart J 2022;43:2469-2478. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab350.

- Blessberger H, Kiblboeck D, Reiter C, Lambert T, Kellermair J, Schmit P, Fellner F, Lichtenauer M, Kypta A, Steinwender C, Kammler J. Monocenter Investigation Micra® MRI study (MIMICRY): feasibility study of the magnetic resonance imaging compatibility of a leadless pacemaker system. Europace 2019;21:137-141. doi: 10.1093/europace/euy143.

- Ching CK, Chakraborty RN, Kler TS, Pumprueg S, Ngarmukos T, Chan JYS, Anand S, Yadav R, Sitthisook S, Yim KW, Jaswal RK, Bhargava K. Clinical safety and performance of a MRI conditional pacing system in patients undergoing cardiac MRI. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2017;40:1389-1395. doi: 10.1111/pace.13232.

- Condon B, Hadley DM. Potential MR hazard to patients with metallic heart valves: the Lenz effect. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:171-6. doi: 10.1002/1522-586(200007)12:1<171::aid-jmri19>3.0.co;2-w.

- Dacher JN, Gandjbakhch E, Taieb J, Chauvin M, Anselme F, Bartoli A, Boyer L, Cassagnes L, Cochet H, Dubourg B, Fauchier L, Gras D, Klug D, Laurent G, Mansourati J, Marijon E, Maury P, Piot O, Pontana F, Sacher F, Sadoul N, Boveda S, Jacquier A; Working Group of Pacing, Electrophysiology of the French Society of Cardiology, Société française dimagerie cardiaque et vasculaire diagnostique et interventionnelle (SFICV). Joint Position Paper of the Working Group of Pacing and Electrophysiology of the French Society of Cardiology (SFC) and the Société française d'imagerie cardiaque et vasculaire diagnostique et interventionnelle (SFICV) on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac electronic implantable devices. Diagn Interv Imaging 2020;101:507-517. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2020.02.003.

- Edwards MB, Mclean J, Solomonidis S, Condon B, Gourlay T. In vitro assessment of the Lenz effect on heart valve prostheses at 1.5 T. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;41:74-82. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24547.

- Gatterer C, Stelzmüller ME, Kammerlander A, Zuckermann A, Krák M, Loewe C, Beitzke D. Safety and image quality of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients with retained epicardial pacing wires after heart transplantation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2021;23:24. doi: 10.1186/s12968-021-00728-1.

- Gakenheimer-Smith L, Etheridge SP, Niu MC, Ou Z, Presson AP, Whitaker P, Su J, Puchalski MD, Asaki SY, Pilcher T. MRI in pediatric and congenital heart disease patients with CIEDs and epicardial or abandoned leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2020;43:797-804. doi: 10.1111/pace.13984.

- Gillam MH, Inacio MCS, Pratt NL, Shakib S, Roughead EE. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in People With Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices: A Population Based Cohort Study. Heart Lung Circ 2018;27:748-751. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2017.09.004.

- Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J 2021;42, 3427-3520.

- Golestanirad L, Dlala E, Wright G, Mosig JR, Graham SJ. Comprehensive analysis of Lenz effect on the artificial heart valves during magnetic resonance imaging. Progress in Electromagnetic Research-PIER 2012;128:1-17.

- Gopalakrishnan PP, Gevenosky L, Biederman RWW. Feasibility of MRI in patients with non-Pacemaker/Defibrillator metallic devices and abandoned leads. J Biomed Sci Eng 2021;14:83-93. doi: 10.4236/jbise.2021.143009.

- Graf H, Lauer UA, Schick F. Eddy-current induction in extended metallic parts as a source of considerable torsional moment. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006;23:585-90. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20539.

- Gupta SK, Ya'qoub L, Wimmer AP, Fisher S, Saeed IM. Safety and Clinical Impact of MRI in Patients with Non-MRI-conditional Cardiac Devices. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2020;2:e200086. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200086.

- Han D, Kang SH, Cho Y, Oh IY. Experiences of magnetic resonance imaging scanning in patients with pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Korean J Intern Med 2019;34:99-107. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2017.251.

- Horwood L, Attili A, Luba F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac implanted electronic devices: focus on contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging protocols. EP Europace 2017;19: 812-817, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw122

- Ikeya Y, Nakai T, Kogawa R, Kurokawa S, Nagashima K, Watanabe R, Arai M, Otsuka N, Kunimoto S, Okumura Y. Current Status and Issues Concerning Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with a Magnetic Resonance Conditional Cardiac Implantable Electrical Device: A Single-center Study. Intern Med 2021;60:1813-1818. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.6517-20.

- Indik JH, Gimbel JR, Abe H, Alkmim-Teixeira R, Birgersdotter-Green U, Clarke GD, Dickfeld TL, Froelich JW, Grant J, Hayes DL, Heidbuchel H, Idriss SF, Kanal E, Lampert R, Machado CE, Mandrola JM, Nazarian S, Patton KK, Rozner MA, Russo RJ, Shen WK, Shinbane JS, Teo WS, Uribe W, Verma A, Wilkoff BL, Woodard PK. 2017 HRS expert consensus statement on magnetic resonance imaging and radiation exposure in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Heart Rhythm 2017;14:e97-e153. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.04.025.

- Jabehdar Maralani P, Schieda N, Hecht EM, Litt H, Hindman N, Heyn C, Davenport MS, Zaharchuk G, Hess CP, Weinreb J. MRI safety and devices: An update and expert consensus. J Magn Reson Imaging 2020;51:657-674. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26909.

- Jekic M, Ding Y, Dzwonczyk R, Burns P, Raman SV and Simonetti OP. Magnetic Field Threshold for Accurate Electrocardiography in the MRI Environment. Magn Reson Med 2010; 64:15861591. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22419

- König CA, Tinhofer F, Puntus T, Burger AL, Neubauer N, Langenberger H, Huber K, Nürnberg M, Zweiker D. Is diversity harmful?-Mixed-brand cardiac implantable electronic devices undergoing magnetic resonance imaging. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2022;134:286-293. doi: 10.1007/s00508-021-01924-w.

- Levine GN, Gomes AS, Arai AE, Bluemke DA, Flamm SD, Kanal E, Manning WJ, Martin ET, Smith JM, Wilke N, Shellock FS; American Heart Association Committee on Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiac Catheterization; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiovascular devices: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Committee on Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiac Catheterization, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Circulation 2007;116:2878-91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187256.

- McRobbie, DW (2020). Essentials of MRI safety. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Morris MF, Verma DR, Sheikh H, Su W and Pershad A. Outcomes after magnetic resonance imaging in patients with pacemakers and defibrillators and abandoned leads. CRM 2018. https://www.crtonline.org/crm-details/outcomes-after-magnetic-resonance-imaging-in-patie

- Munawar DA, Chan JEZ, Emami M, Kadhim K, Khokhar K, O'Shea C, Iwai S, Pitman B, Linz D, Munawar M, Roberts-Thomson K, Young GD, Mahajan R, Sanders P, Lau DH. Magnetic resonance imaging in non-conditional pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2020;22:288-298. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz343.

- Murray AS, Gilligan PJ, Bisset JM, Nolan C, Galvin JM, Murray JG. Provision of MR imaging for patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs): a single-center experience and national survey. Ir J Med Sci 2019;188:999-1004. doi: 10.1007/s11845-018-1922-y.

- Navarro-Valverde C, Ramos-Maqueda J, Romero-Reyes MJ, Esteve-Ruiz I, García-Medina D, Pavón-Jiménez R, Rodríguez-Gómez C, Leal-Del-Ojo J, Cayuela A, Molano-Casimiro FJ. Magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: A prospective study. Magn Reson Imaging 2022;91:9-15. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2022.05.004.

- Nazarian S, Cantillon DJ, Woodard PK, Mela T, Cline AM, Strickberger AS; MRI Ready Investigators. MRI Safety for Patients Implanted With the MRI Ready ICD System: MRI Ready Study Results. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:935-943. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2019.05.010.

- Nguyen TD, Sandberg SA, Durrani AK, Mitchell KW, Keith MD, Gleva MJ, Woodard PK. The cumulative effects and clinical safety of repeat magnetic resonance imaging on an MRI-conditional pacemaker system at 1.5 tesla. Heart Rhythm O2 2020;2:73-79. doi: 10.1016/j.hroo.2020.12.018.

- Nyotowidjojo IS, Skinner K, Shah AS, Bisla J, Singh S, Khoubyari R, Ott P, Kalb B, Indik JH. Thoracic versus nonthoracic MR imaging for patients with an MR nonconditional cardiac implantable electronic device. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2018;41:589-596. doi: 10.1111/pace.13340.

- Okamura H, Padmanabhan D, Watson RE Jr, Dalzell C, Acker N, Jondal M, Romme AL, Cha YM, Asirvatham SJ, Felmlee JP, Friedman PA. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Nondependent Pacemaker Patients with Pacemakers and Defibrillators with a Nearly Depleted Battery. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2017;40:476-481. doi: 10.1111/pace.13042.

- Padmanabhan D, Kella DK, Mehta R, Kapa S, Deshmukh A, Mulpuru S, Jaffe AS, Felmlee JP, Jondal ML, Dalzell CM, Asirvatham SJ, Cha YM, Watson RE Jr, Friedman PA. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with legacy pacemakers and defibrillators and abandoned leads. Heart Rhythm 2018;15:228-233. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.10.022.

- Patterson DI, White JA, Butler CR, et al. 2021 Update on Safety of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Joint Statement From Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:835-847.

- Rinaldi CA, Vitoff PJ, Nair DG, Bernstein R, Mountantonakis SE, Rapacciuolo A, Carter N, Tse HF, Green UB. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging scanning in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillators incorporating quadripolar left ventricular leads. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:2064-2071. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.08.020.

- Robertson NM, Diaz-Gomez M, Condon B. Estimation of torque on mechanical heart valves due to magnetic resonance imaging including an estimation of the significance of the Lenz effect using a computational model. Phys Med Biol 2000;45:3793-807. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/12/320.

- Schaller RD, Brunker T, Riley MP, Marchlinski FE, Nazarian S, Litt H. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients With Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices With Abandoned Leads. JAMA Cardiol 2021;6:549-556. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.7572.

- Schukro C, Puchner SB. Safety and efficiency of low-field magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac rhythm management devices. Eur J Radiol 2019;118:96-100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.07.005.

- Seewöster T, Löbe S, Hilbert S, Bollmann A, Sommer P, Lindemann F, Bacevi?ius J, Schöne K, Richter S, Döring M, Paetsch I, Hindricks G, Jahnke C. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: best practice and real-world experience. Europace 2019;21:1220-1228. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz112.

- Shah AD, Patel AU, Knezevic A, Hoskins MH, Hirsh DS, Merchant FM, et al. Clinical performance of magnetic resonance imaging conditional and nonconditional cardiac Implantable electronic devices. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2017;40:467-75.

- van Dijk VF, Delnoy PPHM, Smit JJJ, Ramdat Misier RA, Elvan A, van Es HW, Rensing BJWM, Raciti G, Boersma LVA. Preliminary findings on the safety of 1.5 and 3 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging in cardiac pacemaker patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2017;28:806-810. doi: 10.1111/jce.13231.

- Vigen KK, Reeder SB, Hood MN, Steckner M, Leiner T, Dombroski DA, Gulani V; ISMRM Safety Committee. Recommendations for Imaging Patients With Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIEDs). J Magn Reson Imaging 2021;53:1311-1317. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27320..

- Vuorinen AM, Paakkanen R, Karvonen J, Sinisalo J, Holmström M, Kivistö S, Peltonen JI, Kaasalainen T. Magnetic resonance imaging safety in patients with abandoned or functioning epicardial pacing leads. Eur Radiol 2022;32:3830-3838. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08469-6.

- Williamson BD, Gohn DC, Ramza BM, Singh B, Zhong Y, Li S, Shanahan L; SureScan Post-Approval Study Investigators. Real-World Evaluation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients With a Magnetic Resonance Imaging Conditional Pacemaker System: Results of 4-Year Prospective Follow-Up in 2,629 Patients. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2017;3:1231-1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.05.011.