Cholinesteraseremmers bij dementie

Uitgangsvraag

Aanbeveling

Bespreek en overweeg het starten van cholinesteraseremmers voor de symptomatische behandeling van lichte tot matig ernstige dementie op basis van de ziekte van Alzheimer.

Overweeg het starten van cholinesteraseremmers bij Parkinsondementie of Lewy Body Dementie als symptomatische behandeling of als behandeling voor neuropsychiatrische symptomen.

Gebruik geen cholinesteraseremmers voor de symptomatische behandeling van vasculaire dementie, frontotemporale dementie of ernstige vormen van de ziekte van Alzheimer.

Gebruiken van cholinesteraseremmers

- Gebruik bij voorkeur rivastigmine in pleistervorm of galantamine in vertraagde afgifte. Gebruik bij voorkeur eenmaal daagse dosering.

- Bouw de behandeling zorgvuldig op en evalueer de behandeling op effecten en bijwerkingen. Bespreek dit met de patiënt.

- Vanwege het risico op syncope en ritme- of geleidingsstoornissen is het voorschrijven van cholinesteraseremmers gecontra-indiceerd in geval van ernstig hartfalen, ‘sick sinus syndrome’, sinoatriaal en atrioventriculair block, en syncope ten gevolge van ritmeproblemen in de voorgeschiedenis (tenzij hier al een pacemaker voor is gegeven).

Stoppen van cholinesteraseremmers

- Overweeg het continueren van cholinesteraseremmers bij ziekteprogressie binnen indicatiegebied van lichte tot matig ernstige dementie gezien het mogelijke risico op achteruitgang van functioneren na het stoppen.

- Overweeg het stoppen van cholinesteraseremmers bij vergevorderd stadium van dementie buiten indicatiegebied van lichte tot matige dementie waarbij de voor- en nadelen van voortzetting van de behandeling besproken worden met de patiënt.

- Stop de behandeling van cholinesteraseremmers bij hinderlijke bijwerkingen in overleg met patiënt.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het doel van deze uitgangsvraag was om de toegevoegde waarde van cholinesteraseremmers in de behandeling van volwassen patiënten met dementie te evalueren. Deze module betreft een update van de richtlijn uit 2014 (zie Appendix 1). Er is daarom gezocht naar nieuwe studies gepubliceerd na de search verricht voor de oude richtlijn.

In totaal zijn vier nieuwe systematische reviews gevonden, met daarin zestien relevante RCTs, die behandeling met cholinesteraseremmers vergeleken met placebo in volwassenen met dementie. De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten cognitief functioneren, algemeen dagelijks functioneren en neuropsychiatrische symptomen is beoordeeld als laag voor patiënten met AD en (zeer) laag voor patiënten met PDD/DLB. Dit werd veroorzaakt door een risico op bias, brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen, conflicterende resultaten en missende waarden. De overall bewijskracht blijft hierdoor laag. Er kunnen op basis van alleen deze literatuur dus geen sterke aanbevelingen geformuleerd worden over de waarde van cholinesteraseremmers bij volwassen patiënten met dementie.

Elf van de zestien RCTs onderzochten het effect van donepezil, wat in Nederland weinig wordt voorgeschreven. Slechts vijf van de zestien RCTs onderzochten het effect van galantamine en rivastigmine. Er is dus weinig nieuwe literatuur beschikbaar over de inzet van cholinesteraseremmers (met name de frequent gebruikte rivastigmine en galantamine), welke ook een lage bewijskracht heeft. De conclusies uit deze literatuur verschillen niet aanzienlijk van de literatuuranalyse verricht in 2014 (zie Appendix 1). Hierdoor biedt deze literatuurupdate geen reden om de aanbevelingen zoals gedaan in 2014 te wijzigen. Naast bovenstaande resultaten, zijn ook de conclusies uit de oude versie van deze module (uit 2014) (zie Appendix 1) vergeleken met de meest recente versie van de NICE guideline (2018). De overeenstemming hiertussen bevestigt dat de conclusies uit 2014 nog geldend en relevant zijn voor de huidige module.

Het advies blijft dus om starten met cholinesteraseremmers te overwegen bij lichte tot matige Alzheimer dementie. In de meeste studies die onderzoek deden naar het effect van cholinesteraseremmers werd een lichte tot matige dementie gedefinieerd op basis van een MMSE score van 10-26. In de praktijk zal dit overeenkomen met een dementie ernst CDR 1-2. Omdat in de praktijk ook veel andere cognitieve screeners gebruikt worden en vervolgen van het functioneren in de praktijk passender is dan het vervolgen van een cognitieve screener, adviseren we de CDR classificatie te gebruiken voor het bepalen van de indicatie tot starten met cholinesteraseremmers.

Stoppen

In de praktijk ontstaan ook vragen hoe lang door te gaan met behandeling met cholinesteraseremmers, met name bij progressie van de dementie. Er is beperkt onderzoek gedaan naar het effect van stoppen van cholinesteraseremmers op het beloop van de ziekte. In 2021 is een Cochrane Review uitgevoerd die keek naar het effect van stoppen danwel continueren van cholinesteraseremmers op cognitie, functioneren en neuropsychiatrische symptomen (Parsons, 2021). Er werden zes studies met in totaal 955 patiënten met Alzheimer dementie gevonden die het effect van stoppen van cholinesteraseremmers onderzochten. Hieruit komt naar voren dat stoppen met cholinesteraseremmers mogelijk leidt tot een slechter cognitief functioneren, toename van neuropsychiatrische symptomen en slechtere functionele status. Echter, de verschillen zijn klein en de bewijskracht is laag. Op basis hiervan kan conform de NICE guideline 2018 geconcludeerd worden dat alleen progressie van de dementie binnen het indicatiegebied van de cholinesteraseremmers (lichte tot matig ernstige Alzheimer dementie) geen reden is om cholinesteraseremmers te stoppen. Wanneer er echter sprake is van een vergevorderde dementie Alzheimer dementie wordt niet meer voldaan aan het indicatiegebied van de cholinesteraseremmers en kan overwogen worden de cholinesteraseremmer te stoppen. Los van progressie van de dementie kunnen hinderlijke bijwerkingen natuurlijk een reden zijn om in overleg met de patiënt te stoppen met de medicatie.

Bijwerkingen

De literatuuranalyse toont dat bijwerkingen bij cholinesteraseremmers vaker voorkomen dan bij placebo (interventie: 57.7-74.8%, placebo: 47.4%-70.7%), maar de verschillen zijn klein. De meeste bijwerkingen zijn mild en reversibel na staken. Een potentieel ernstige bijwerking is het optreden van syncope. Daarom is het gebruik van cholinesteraseremmers gecontra-indiceerd bij ernstig hartfalen, ‘sick sinus syndrome’, sinoatriaal en atrioventriculair block, en syncope ten gevolge van ritmeproblemen in de voorgeschiedenis (tenzij hier al een pacemaker voor is gegeven). Op basis van de huidige literatuurupdate kunnen we geen conclusies trekken over verschillen in bijwerkingenprofiel tussen de verschillende cholinesteraseremmers. Uit de vorige literatuuranalyse kwam naar voren dat bij orale toediening van rivastigmine vaker gastro-intestinale bijwerkingen werden gerapporteerd dan bij de pleistervorm. Bij de pleistervorm komt echter regelmatig huiduitslag voor, namelijk bij 10.4% van de patiënten die de pleister van 9.6 mg/dag gebruikt.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Gezien de geringe effecten van cholinesteraseremmers en mogelijke bijwerkingen dient met de patiënt afgewogen te worden of deze wenst te starten met behandeling. Wanneer de patiënt kiest voor behandeling met cholinesteraseremmers dienen de voorkeuren van de patiënt meegenomen te worden in de keuze voor toediening in tabletvorm of pleistervorm, op basis van ervaren gebruiksgemak en mogelijke bijwerkingen. Een eenmaal daagse dosering vergroot het gebruiksgemak en daarmee vermoedelijk de therapietrouw.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is beperkt onderzoek gedaan naar de kosteneffectiviteit van cholinesteraseremmers. Een systematic review vond drie studies naar de kosteneffectiviteit van donepezil, één naar galantamine en één naar rivastigmine (Huo, 2022). Behandeling met cholinesteraseremmers leidt in deze review tot een toename van kosten. Echter wanneer ook mantelzorg wordt meegenomen, leiden deze middelen tot een (niet-significante) kostenbesparing op maatschappelijk niveau bij verbetering van dementie gerelateerde symptomen.

Er zijn geen grote verschillen in kosten tussen de verschillende cholinesteraseremmers. Wanneer gebruikt in de hoogste dosering van 1x/dag 10 mg, is donepezil iets duurder dan rivastigmine of galantamine (Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas, medicijnkosten.nl).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Gezien de aanbevelingen ongewijzigd zijn ten opzichte van de richtlijn uit 2014, zullen deze aanbevelingen al breed geïmplementeerd zijn. Het cluster voorziet dan ook geen barrières op het gebied van aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Hoewel het effect van cholinesteraseremmers op de verschillende uitkomstmaten bij Alzheimer dementie gering is, is het in relatief grote studiepopulaties onderzocht en is het effect consistent. Daarbij zijn de bijwerkingen meestal mild. Daarom wordt geadviseerd het starten van cholinesteraseremmers te overwegen en te bespreken met patiënt bij lichte tot matige dementie (CDR 1-2).

Ook bij Parkinsondementie en Lewy Body Dementie is het effect van cholinesteraseremmers aangetoond. In de praktijk worden in deze groep vaak gunstige effecten gezien van cholinesteraseremmers op neuropsychiatrische symptomen, zoals hallucinaties en waanideeën. Waardoor cholinesteraseremmers bij patiënten met neuropsychiatrische symptomen bij Parkinsondementie of Lewy Body Dementie zeker te overwegen zijn.

Op basis van de literatuur is er geen voorkeur uit te spreken voor één van de cholinesteraseremmers. Vanwege het gebruiksgemak wordt een eenmaal daags dosering aanbevolen. Daarbij geeft de orale rivastigmine, welke tweemaal daags gedoseerd wordt, mogelijk meer gastro-intestinale bijwerkingen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

A multifactorial approach focused on the needs of the individual patient and caregiver is paramount in the treatment of dementia. Cholinesterase inhibitors may be part of the symptomatic treatment of mild-to-moderate dementia. However, the effects of medications differ per person and are not well investigated to date. This module evaluates the role of cholinesterase inhibitors as a treatment option for patients with dementia.

Conclusies

1. Cognitive function (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

1.1 Use of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine may result in little to no difference in cognitive function when compared with placebo in adults with AD.

Source: Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Frölich, 2011; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016; Nakamura, 2011; Jia, 2017; Hager, 2014; Iranmanesh, 2012. |

|

Low GRADE |

1.2 Use of donepezil may result in little to no difference in cognitive function when compared with placebo in adults with PDD/DLB.

Source: Dubois, 2012; Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015. |

2. Functional performance in activities of daily living (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

2.1 Use of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine may result in little to no difference in functional performance in activities of daily living when compared with placebo in adults with AD.

Source: Maher-Edwards, 2011; Frölich, 2011; Nakamura, 2011; Hager, 2014; Haig, 2014; Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016. |

|

Low GRADE |

2.2 Use of donepezil may result in little to no difference in functional performance in activities of daily living when compared with placebo in adults with PDD/DLB.

Source: Dubois, 2012. |

3. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

3.1 Use of donepezil may result in little to no difference in neuropsychiatric symptoms when compared with placebo in adults with AD.

Source: Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Marek, 2014; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016. |

|

Very low GRADE |

3.2 The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of donepezil on neuropsychiatric symptoms when compared with placebo in adults with PDD/DLB.

Source: Dubois, 2012; Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015. |

4. Caregiver burden (important)

|

No GRADE |

4.1 No evidence was found regarding the effect of cholinesterase inhibitors on caregiver burden compared with placebo or no cholinesterase inhibitor treatment in adults with AD.

Source: - |

|

Very low GRADE |

4.2 The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of donepezil on caregiver burden when compared with placebo in adults with PDD/DLB.

Source: Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015. |

5. Quality of life (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

5.1 The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of donepezil on quality of life when compared with placebo in adults with AD.

Source: Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Marek, 2014, Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016. |

|

No GRADE |

5.2 No evidence was found regarding the effect of cholinesterase inhibitors on quality of life compared with placebo or no cholinesterase inhibitor treatment in adults with PDD/DLB.

Source: - |

6. Adverse events (important)

|

Low GRADE |

6.1 Use of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine may result in little to no difference in adverse events when compared with placebo in adults with AD.

Source: Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Jia, 2017; Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Frölich, 2011; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016; Nakamura, 2011, Hager, 2014. |

|

Low GRADE |

6.2 Use of donepezil may result in little to no difference in adverse events when compared with placebo in adults with PDD/DLB.

Source: Dubois, 2012; Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Watts (2023) performed a systematic review of the literature that investigated the efficacy of different pharmacological interventions for managing people with Lewy body dementia (LBD) and Parkinson’s Disease dementia (PDD). Fifteen databases were searched until 1 July 2020. Quality assessment of the individual studies was performed by using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. A total of 135 studies with a variety of designs were included in the systematic review. Three RCTs were conform our PICO and were extracted and analyzed in this literature analysis (Dubois, 2012; Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015). The RCTs compared different doses of donepezil treatment with placebo. The studies included in Watts (2023) that investigated the effectiveness of galantamine and rivastigmine did not meet our selection criteria. Study characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 826 participants were included in the three studies, with sample sizes ranging from 138 to 550. Mean age ranged from 70.8 to 79.6 years, and follow-up varied from 12 to 24 weeks.

Jin (2019) performed a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of different pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for people with dementia. The databases PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane library, and CINAHL were searched from inception to 1 August 2018. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool was used to assess the risk of bias and quality of each individual study. In total, 146 RCTs were included in this systematic review. Three RCTs were conform our PICO and were extracted and analyzed in this literature analysis (Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Jia, 2017). All three studies compared donepezil treatment with placebo in an Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) population. The studies included in Jin (2019) that investigated the effectiveness of galantamine and rivastigmine did not meet our selection criteria. Study characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 564 participants were included in the selected studies, with sample sizes ranging from 123 to 313. Mean age ranged from 70.0 to 71.6 years, and follow-up varied from 12 to 24 weeks.

Knight (2018) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effectiveness of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI) and memantine in individuals diagnosed with dementia. The databases Web of Science, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and CINAHL were searched prior to March 2017. The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. In total, 80 RCTs met the inclusion criteria. Eight were conform our PICO and were included in the current literature analysis (Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Iranmanesh, 2012; Frölich, 2011; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016; Koch, 2014; Likitjaroen, 2011). Five trials compared donepezil treatment with placebo (Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Frölich, 2011; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016), two studies investigated rivastigmine treatment (Iranmanesh, 2012; Koch, 2014), and one study compared galantamine treatment with placebo in an AD population (Likitjaroen, 2011). Study characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 1127 participants were included in the selected studies, with sample sizes ranging from 16 to 163. Mean age ranged from 66.9 to 76.4 years, and follow-up varied from 4 to 26 weeks.

Dou (2018) performed a network meta-analysis of RCTs to compare the efficacy and tolerability of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine for management of AD. PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Embase were searched for RCTs published from inception to 21 July 2017. Quality assessment of the individual studies was performed by using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. A total of 41 RCTs were included, of which two were conform our PICO and analyzed in the current literature analysis (Hager, 2014; Nakamura, 2011). Hager (2014) compared galantamine treatment with placebo, whereas Nakamura (2011) compared two different doses of rivastigmine with placebo. Study characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 2900 participants were included in the selected studies, with sample sizes ranging from 282 to 1024. Mean age ranged from 73.0 to 75.1 years, and follow-up varied from 24 to 104 weeks.

Table 1: Characteristics of included studies

|

Study |

Condition |

Severity of dementia |

Intervention |

Comparison |

Outcomes of interest reported |

Follow-up |

||

|

Type |

Characteristics |

Type |

Characteristics |

|

|

|||

|

Watts, 2023 |

||||||||

|

Dubois, 2012a,c USA |

PDD

|

MMSE ≥10 and ≤26 |

Donepezil (5 mg) |

n = 195 Mean age (SD): 72.0 (6.8) years Male (%): 65% Mean duration of dementia (SD): 0.7 (0.9) years |

Placebo

|

n = 173 Mean age (SD): 72.9 (6.5) years Male (%): 65% Mean duration of dementia (SD): 0.7 (1.2) years |

|

24 weeks |

|

Donepezil (10 mg)

|

n = 182 Mean age (SD): 70.8 (7.5) years Male (%): 75% Mean duration of dementia (SD): 0.9 (1.4) years |

|||||||

|

Mori, 2012a,c Japan |

DLB

|

MMSE ≥10 and ≤26 |

Donepezil (5 mg)

|

n = 32 Mean age (SD): 77.9 (6.8) years Male (%): 50.0% |

Placebo

|

n = 35 Mean age (SD): 78.6 (4.7) years Male (%): 28.1% |

|

12 weeks |

|

Donepezil (10 mg)

|

n = 36 Mean age (SD): 78.6 (6.1) years Male (%): 11.1% |

|||||||

|

Ikeda, 2015c Japan |

DLB

|

MMSE ≥10 and ≤26 |

Donepezil (5 mg)

|

n = 45 Mean age (SD): 78.8 (5.1) years Male (%): 44.4% Mean duration of dementia (SD): 2.7 (1.8) years |

Placebo

|

n = 44 Mean age (SD): 77.2 (6.1) years Male (%): 38.6% Mean duration of dementia (SD): 2.0 (2.3) years |

|

12 weeks |

|

Donepezil (10 mg)

|

n = 49 Mean age (SD): 77.7 (6.8) years Male (%): 42.9% |

|||||||

|

Jin, 2019 |

||||||||

|

Maher-Edwards, 2011b,c UK |

AD

|

MMSE ≥12 and ≤24 |

Donepezil (10 mg)

|

n = 67 Mean age (SD): 71.1 (8.4) years Male (%): 37% Median duration since first diagnosis (min, max): 0.7 (0.1-8.2) years |

Placebo

|

n = 61 Mean age (SD): 71.6 (6.7) years Male (%): 30% Median duration since first diagnosis (min, max): 0.9 (0.1-6.7) years |

|

24 weeks |

|

Haig, 2014c USA |

AD

|

MMSE ≥10 and ≤24 |

Donepezil (10 mg)

|

n = 60 Mean age (SD): 70.5 (8.3) years Male (%): 40.0% Mean duration since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.1 (1.7) years |

Placebo

|

n = 63 Mean age (SD): 70.3 (7.8) years Male (%): 38.1% Mean duration since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.1 (1.6) years |

|

12 weeks |

|

Jia, 2017c China |

AD |

MMSE score ≥1 and ≤12 |

Donepezil (10 mg)

|

n = 157 Mean age (SD): 71.6 (8.6) years Male (%): 32.5% |

Placebo

|

n = 156 Mean age (SD): 70.0 (9.6) years Male (%): 37.8% |

|

24 weeks |

|

Knight, 2018 |

||||||||

|

Marek, 2014 UK, Russia, South-Africa, Ukraine |

AD

|

MMSE ≥10 and ≤24 |

Donepezil (10 mg) |

n = 66 Mean age (SD): 71.8 (8.4) years Male (%): 47% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.2 (2.3) years |

Placebo |

n = 66 Mean age (SD): 71.7 (9.0) years Male (%): 39.4% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.2 (1.7) years |

|

12 weeks |

|

Maher-Edwards, 2015 Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Italy, Korea, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Spain, South Africa, USA |

AD

|

MMSE ≥10 and ≤26 |

Donepezil (5-10 mg) |

n = 147 Mean age (SD): 71.1 (7.5) years Male (%): 35% Median time since first diagnosis: 0.9 years |

Placebo |

n = 135 Mean age (SD): 73.3 (6.8) years Male (%): 36% Median time since first diagnosis: 1.1 years |

|

24 weeks |

|

Frölich, 2011 Germany |

AD |

MMSE ≥12 and ≤26 |

Donepezil (10 mg) |

n = 158 Mean age (SD): 73.9 (6.5) years Male (%): 34.2% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 0.9 (1.2) years |

Placebo |

n = 163 Mean age (SD): 73.5 (6.4) years Male (%): 44.8% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 0.8 (1.5) years |

|

12 weeks |

|

Gault, 2015 USA, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovakia, South Africa, UK |

AD |

MMSE ≥10 and ≤24 |

Donepezil (10 mg) |

n = 68 Mean age (SD): 73.9 (7.9) years Male (%): 54.4% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.1 (1.3) years |

Placebo |

n = 68 Mean age (SD): 73.6 (8.2) years Male (%): 38.2% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.3 (1.6) years |

|

12 weeks |

|

Gault, 2016 USA, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Ukraine, UK |

AD |

MMSE ≥10 and ≤24 |

Donepezil (10 mg) |

n = 75 Mean age (SD): 75.1 (7.8) years Male (%): 46.7% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.6 (1.9) years |

Placebo |

n = 104 Mean age (SD): 73.2 (7.4) years Male (%): 37.5% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.1 (1.8) years |

|

24 weeks |

|

Iranmanesh, 2012 Iran |

AD

|

NR |

Rivastigmine (3 mg) |

n = 16 Male mean age (SD): 75.3 (2.3) years* Female mean age (SD): 77.2 (2.3) years* Male (%): 50%* |

Placebo |

n = 16 Male mean age (SD): 75.3 (2.3) years* Female mean age (SD): 77.2 (2.3) years* Male (%): 50%* |

|

12 weeks |

|

Koch, 2014 Italy |

AD |

NR |

Rivastigmine (4.6 mg) |

n = 10 Mean age (SD): 70.5 (4.8) years Male (%): 50% |

Placebo |

n = 10 Mean age (SD): 66.9 (6.1) years Male (%): 40% |

|

12 weeks |

|

Likitjaroen, 2011 Germany |

AD |

|

Galantamine (16 mg) |

n = 14 Mean age (SD): 73.5 (7.2) years Male (%): 43% |

Placebo |

n = 11 Mean age (SD): 76.4 (7.9) years Male (%): 36% |

|

12 months |

|

Dou, 2018 |

||||||||

|

Hager, 2014c Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine |

AD

|

MMSE ≥10 and ≤26 |

Galantamine (24 mg) |

n = 1024 Mean age (SD): 73.0 (8.9) years Male (%): 34.5% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 0.8 (1.5) years |

Placebo |

n = 1021 Mean age (SD): 73.0 (8.7) years Male (%): 35.9% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 0.8 (1.6) years |

|

104 weeks |

|

Nakamura, 2011 Japan |

AD

|

MMSE ≥10 and ≤20 |

Rivastigmine patch (5 cm2) |

n = 282 Mean age (SD): 74.3 (7.5) years Male (%): 31.2% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.6 (1.7) years |

Placebo |

n = 286 Mean age (SD): 74.5 (7.4) years Male (%): 31.8% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.7 (1.9) years |

|

24 weeks |

|

Rivastigmine patch (10 cm2) |

n = 287 Mean age (SD): 75.1 (6.9) years Male (%): 32.1% Mean time since AD diagnosis (SD): 1.7 (1.8) years |

|||||||

Abbreviations: ACQLI = Alzheimer Carer’s Quality of Life Instrument; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; ADAS-cog = Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale; ADCS-ADL = Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activity of Daily Living; CSDD = Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; DAD = Disability Assessment for Dementia; DEMQOL = DEMentia Quality of Life; DLB = Dementia with Lewy bodies; MHIS = Modified Hachinski Ischemic Scale; MMSE = Mini-Mental Status Examination; NPI = Neuropsychiatric Inventory; PDD = Parkinson’s Disease Dementia; QoL-AD = Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s disease; SD = standard deviation; SE = Schwab and England; ZBI = Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview. a Included in Jin (2019) as well; b Included in Dou (2018) as well; c Included in Knight (2018) as well; * Values reported are for the total population

Results

1. Cognitive function

1.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

Thirteen studies reported on cognitive function in an AD population, assessed by using either the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) or the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (ADAS-cog: Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Frölich, 2011; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016; Nakamura, 2011; MMSE: Jia, 2017; Hager, 2014; Iranmanesh, 2012; Koch, 2014; Likitjaroen, 2011). The ADAS-cog consists of 11 items with maximum scores ranging from 0 to 70, in which lower scores indicate better cognitive function. The MMSE ranges from 0 to 30 in which a higher score represents better cognitive function. As cognitive function is measured using two different instruments with different scales, standardized mean differences (SMD) are reported. SMD is used as a summary statistic when the studies all assess the same outcome but measure it in a variety of ways. Data of eight studies could be pooled. All pooled studies reported an (adjusted/LS) mean change score from baseline to follow-up.

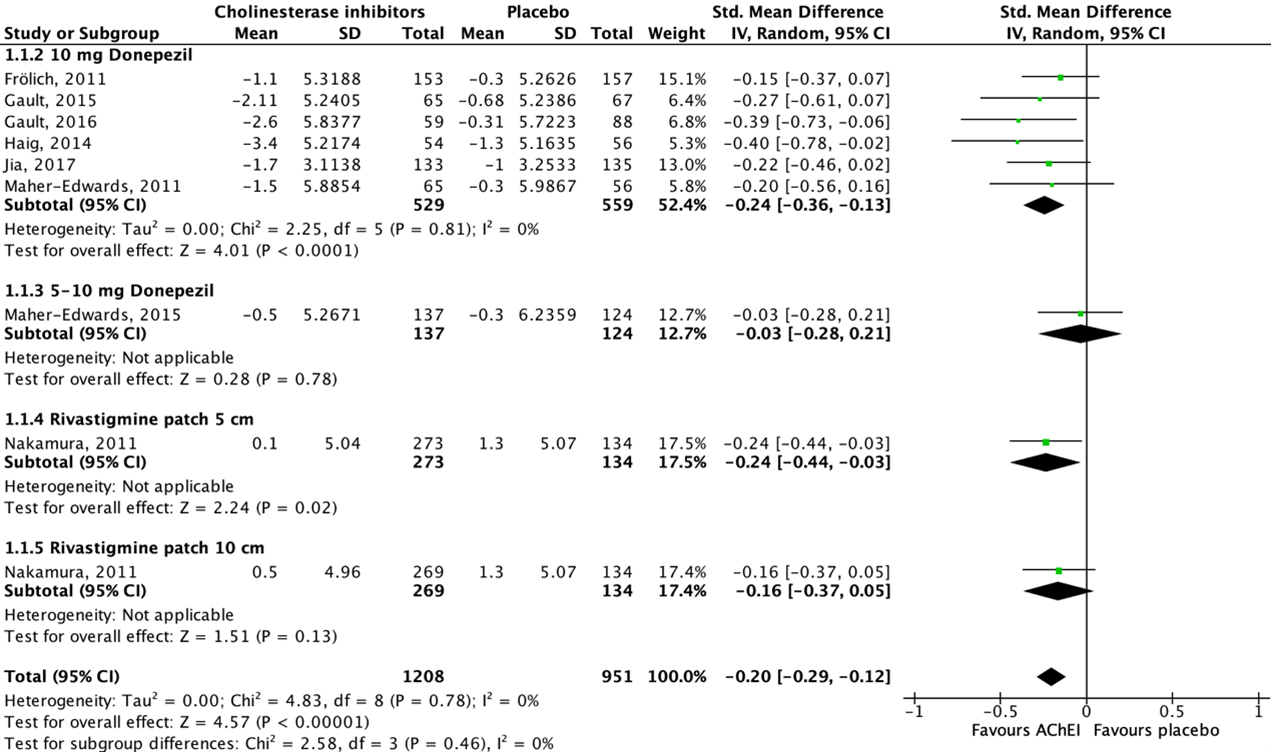

Figure 1 shows that seven studies reported on donepezil and one study reported on rivastigmine. All studies showed a beneficial effect for acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment when compared to placebo. The overall pooled data show an SMD of -0.20 (95%CI -0.29 to -0.12) favoring acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment, which was considered not clinically relevant.

Data of five studies could not be pooled because of missing dispersion measures (SE/SD) (Hager, 2014), variety in the way of reporting the outcome measure (Koch, 2014; Likitjaroen, 2011) and/or missing (absolute) change values (Marek, 2014; Iranmanesh, 2012).

- Marek (2014) reported improvement in donepezil subjects at weeks 8 and 12 on the 11-item ADAS-Cog.

- Hager (2014) reported a mean change in MMSE score from baseline to month 24 of -1.41 for the galantamine group (n=874) and -2.14 for the placebo group (n=891).

- Koch (2014) reported posttreatment average (SD) MMSE scores of 23.0 (2.8) for the rivastigmine group (n=10) and 22.8 (3.4) for the placebo group (n=10). Mean difference was 0.2 (95%CI -2.53 to 2.93) in favor of rivastigmine treatment. This difference was considered not clinically relevant.

- Likitjaroen (2011) reported posttreatment average (SD) MMSE scores of 20.4 (1.9) for the galantamine group (n=7) and 22.0 (3.5) for the placebo group (n=8). Mean difference was -1.60 (95%CI -4.40 to 1.20) in favor of placebo. This difference was considered not clinically relevant.

- Iranmanesh (2012) reported posttreatment average MMSE scores of 18/3750 (3/36403) and 14/1250 (3/87943), respectively. The values cannot be traced and are therefore not interpretable.

Figure 1: The effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors treatment on cognitive function in an AD population with subgroups for different treatments/doses.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

1.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

Three studies reported on cognitive function in a PDD/DLB population, assessed by using either the ADAS-cog (Dubois, 2012) or the MMSE (Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015). All studies reported an (adjusted/LS) mean change score from baseline to follow-up. As one study did not report dispersion measures (SE/SD) (Dubois, 2012), data could not be pooled.

- Dubois (2012) reported an adjusted mean change in ADAS-cog score from baseline to week 24 of -2.43 for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=173), -2.43 for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=168), and -0.98 for the placebo group (n=166).

- Mori (2012) reported a mean change (SD) in MMSE score from baseline to week 12 of 3.4 (3.2) for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=32), 2.0 (3.3) for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=36), and -0.4 (2.7) for the placebo group (n=32). Mean difference was 3.80 (95%CI 2.35 to 5.25) in favor of the 5-mg donepezil group, and 2.40 (95%CI 0.97 to 3.83) in favor of the 10-mg donepezil group. These differences were both considered clinically relevant.

- Ikeda (2015) reported a mean change (SD) in MMSE score from baseline to week 12 of 1.4 (3.4) for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=45), 2.2 (2.9) for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=49), and 0.6 (3.0) for the placebo group (n=44). Mean difference was 0.80 (95%CI -0.53 to 2.13) in favor of the 5-mg donepezil group, and 1.60 (95%CI 0.40 to 2.80) in favor of the 10-mg donepezil group. These differences were both considered not clinically relevant.

2. Functional performance in activities of daily living

2.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

Nine studies reported on functional performance in activities of daily living in an AD population, assessed by using the Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) scale (Maher-Edwards, 2011; Frölich, 2011; Nakamura, 2011; Hager, 2014) or the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activity of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL) scale (Haig, 2014; Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016). Higher scores reflect greater functional performance for both scales. As functional performance is measured using two different instruments with different scales, SMD are reported. Data of seven studies could be pooled.

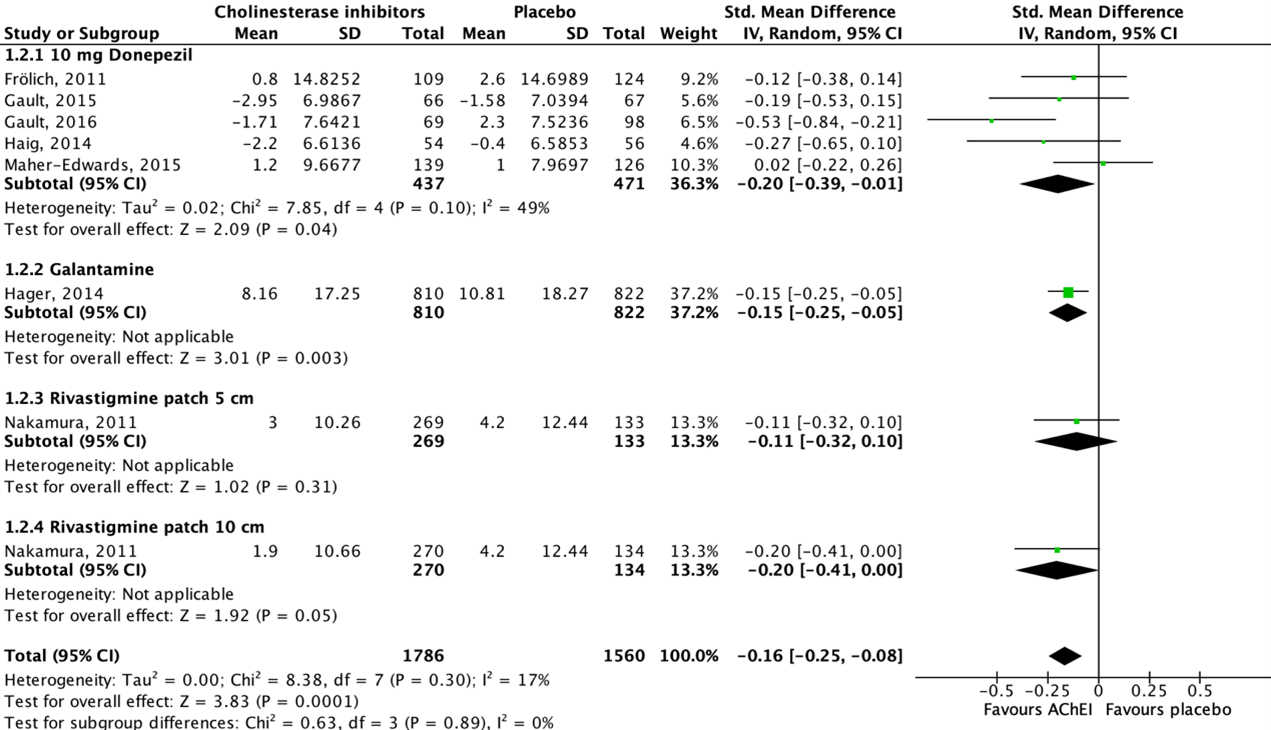

Figure 2 shows that five studies reported on donepezil, one study reported on galantamine and another study reported on rivastigmine. Seven out of eight studies showed a beneficial effect for acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment when compared to placebo, whereas one study showed a beneficial effect for placebo treatment. The overall pooled data show an SMD of -0.16 (95%CI -0.25 to -0.08) favoring acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment, which was considered not clinically relevant.

Data of two studies could not be pooled due to missing absolute values (Maher-Edwards, 2011; Marek, 2014).

- Maher-Edwards (2011) reported no absolute values but mentioned that the difference from placebo for the donepezil group was small for the DAD scale.

- Marek (2014) reported no improvement for the donepezil group on the ADCS-ADL scale compared with placebo.

Figure 2: The effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors treatment on functional performance in activities of daily living in an AD population with subgroups for different treatments/doses.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

2.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

One study reported on functional performance in activities of daily living in a PDD/DLB population, assessed by using the DAD scale (Dubois, 2012) and the Schwab and England (SE) scale (Dubois, 2012). Higher scores reflect greater functional performance for both scales. Data could not be pooled due to missing dispersion measures (SE/SD).

- Dubois (2012) reported an adjusted mean change in DAD score from baseline to week 24 of 0.28 for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=181), 0.25 for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=170), and -1.99 for the placebo group (n=170). In addition, the authors reported an adjusted mean change in SE score from baseline to week 24 of -1.34 for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=183), -1.00 for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=171), and -0.66 for the placebo group (n=170).

3. Neuropsychiatric symptoms

3.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

Five studies reported on neuropsychiatric symptoms in an AD population, assessed by the 10-item (Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016) or 12-item (Marek, 2014) Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). The higher the NPI total score, the more severe the neuropsychiatric symptoms. Studies reported an (adjusted/LS) mean change score from baseline to follow-up. Data of three studies could be pooled.

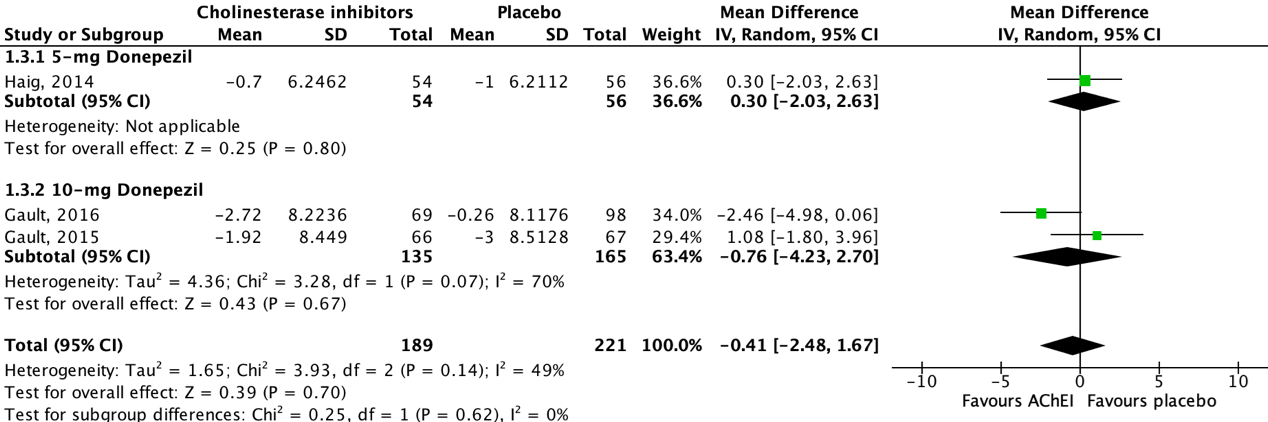

Figure 3 shows that all studies reported on donepezil. One out of three studies showed a beneficial effect for acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment when compared to placebo, whereas the other two studies showed a beneficial effect for placebo treatment. The overall pooled data show a mean difference of -0.41 (95%CI -2.48 to 1.67) favoring acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment, which was considered not clinically relevant.

Data of two studies could not be pooled due to missing dispersion measures (SE/SD) (Marek, 2014) and missing absolute values (Maher-Edwards, 2011).

- Maher-Edwards (2011) reported that the difference from placebo for the donepezil group was small for the NPI-10 scale.

- Marek (2014) reported an LS mean change in NPI-12 score from baseline to week 12 of -2.13 for the donepezil group (n=66) and 0.35 for the placebo group (n=66).

Figure 3: The effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors treatment on neuropsychiatric symptoms in an AD population with subgroups for different doses.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

3.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

Three studies reported on neuropsychiatric symptoms in a PDD/DLB population, assessed by the 10-item NPI (Dubois, 2012; Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015). Studies reported an (adjusted/LS) mean change score from baseline to follow-up. As one study did not report dispersion measures (SE/SD) (Dubois, 2012), data could not be pooled.

- Dubois (2012) reported an adjusted mean change in NPI-10 score from baseline to week 24 of -1.87 for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=182), -1.49 for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=172), and -0.34 for the placebo group (n=170).

- Mori (2012) reported a mean (SD) change in NPI-10 score from baseline to week 12 of -5.5 (6.7) for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=32), -8.0 (12.8) for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=35), and 0.3 (17.5) for the placebo group (n=32). Mean differences were -5.80 (95%CI -12.29 to 0.69) in favor of the 5-mg donepezil group, and -8.30 (95%CI -15.70 to -0.90) in favor of the 10-mg donepezil group. These differences were considered not clinically relevant.

- Ikeda (2015) reported a mean (SD) change in NPI-10 score from baseline to week 12 of -3.3 (9.4) for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=45), -5.5 (9.8) for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=49), and -6.4 (9.9) for the placebo group (n=44). Mean differences were 3.10 (95%CI -0.92 to 7.12) in favor of placebo, and 0.90 (95%CI -3.12 to 4.92) in favor of donepezil 10-mg. These differences were considered not clinically relevant.

4. Caregiver burden

4.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

No studies reported on caregiver burden in an AD population.

4.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

Two studies reported on caregiver burden in a PDD/DLB population, assessed by using the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (ZBI) (Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015). The ZBI contains 22 items scored from 0 (best) to 4 (worst) resulting in a total score between 0 and 88.

- Mori (2012) reported a mean (SD) change in ZBI score from baseline to week 12 of -0.7 (15.7) for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=31), -5.0 (13.6) for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=31), and 4.2 (10.4) for the placebo group (n=31). Mean differences were -4.9 (95%CI -12.53 to 2.73) and -9.20 (95%CI -16.19 to -2.21) which were both not clinically relevant.

- Ikeda (2015) reported a mean (SD) change in ZBI score from baseline to week 12 of -5.0 (12.1) for the 5-mg donepezil group (n=45), -0.8 (11.9) for the 10-mg donepezil group (n=49), and -0.1 (8.4) for the placebo group (n=44). Mean differences were -4.9 (95%CI -9.89 to 0.09) and -0.7 (95%CI -5.55 to 4.15) in favor of the donepezil groups. These differences were not considered clinically relevant.

5. Quality of life

5.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

Five studies reported on quality of life in an AD population, assessed by using the Alzheimer Carer’s Quality of Life Instrument (ACQLI) (Maher-Edwards, 2011), DEMentia Quality of Life (DEMQOL) (Gault, 2016), and the Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) score (Haig, 2014; Marek, 2014, Gault, 2015). The maximum score of the ACQLI ranges from 0 to 30 in which higher scores indicate worse quality of life. The 13-item QoL-AD ranges from 13 to 52 in which higher scores represent better quality of life. DEMQOL contains 28 items scored on a four-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating better health-related quality of life.

Data could not be pooled due to missing absolute values (Maher-Edwards, 2011; Gault, 2016; Marek, 2014), and data availability of only two studies.

- Maher-Edwards (2011) reported no absolute values but mentioned that the difference from placebo for the donepezil group was small for the ACQLI score.

- Haig (2014) reported an LS mean (SD) change in QoL-AD total subject score from baseline to week 12 of 0.6 (4.4) for the donepezil group (n=54) and 0.2 (4.6) for the placebo group (n=56). Mean difference was 0.4 (95%CI -1.29 to 2.09) in favor of donepezil treatment. This difference is not clinically relevant. In addition, the authors reported an LS mean (SD) change in QoL-AD total caregiver score from baseline to week 12 of -0.3 (3.7) for the donepezil group (n=54) and 0.3 (3.7) for the placebo group (n=56). Mean difference was -0.60 (95%CI -1.99 to 0.79) in favor of placebo, which was not considered clinically relevant.

- Gault (2015) reported an LS mean (SD) change in QoL-AD total subject score from baseline to week 12 of 0.24 (4.1) for the donepezil group (n=63) and 1.19 (4.2) for the placebo group (n=63). Mean difference was -0.95 (95%CI -2.41 to 0.51) in favor of placebo. This difference is not clinically relevant. Additionally, the authors reported an LS mean (SD) change in QoL-AD total caregiver score from baseline to week 12 of 0.02 (3.8) for the donepezil group (n=63) and 0.44 (3.8) for the placebo group (n=66). Mean difference was -0.42 (95%CI -1.74 to 0.90) favoring placebo. This difference is not clinically relevant.

- Gault (2016) mentioned that no differences in DEMQOL between the donepezil treatment group and placebo group at final evaluation were observed.

- Marek (2014) reported that the donepezil treatment group showed no improvement on the QoL-AD subject or caregiver total scores compared with placebo.

5.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

None of the studies reported on quality of life in an PDD/DLB population.

6. Adverse events

6.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

Ten studies reported on adverse events in an AD population, defined as the proportion of participants that experienced any adverse event (e.g., nausea, tremor, diarrhea, fall, insomnia, vomiting, hallucination, anorexia, confusional state, urinary tract infection, weight loss, back pain, dizziness, constipation) (Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Jia, 2017; Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Frölich, 2011; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016; Nakamura, 2011; Hager, 2014).

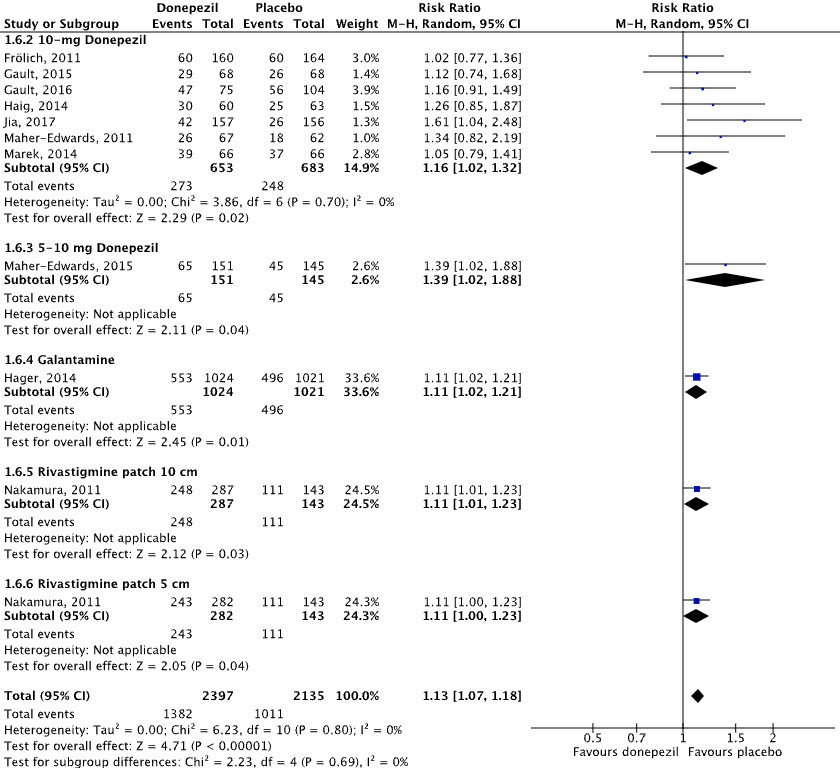

Figure 4.1 shows that adverse events were reported in 57.7% (1382/2397) of patients in the intervention group and in 47.4% (1011/2135) of patients in the placebo group. The overall pooled data show a risk ratio of 1.13 (95%CI 1.07 to 1.18), favoring placebo. This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

6.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

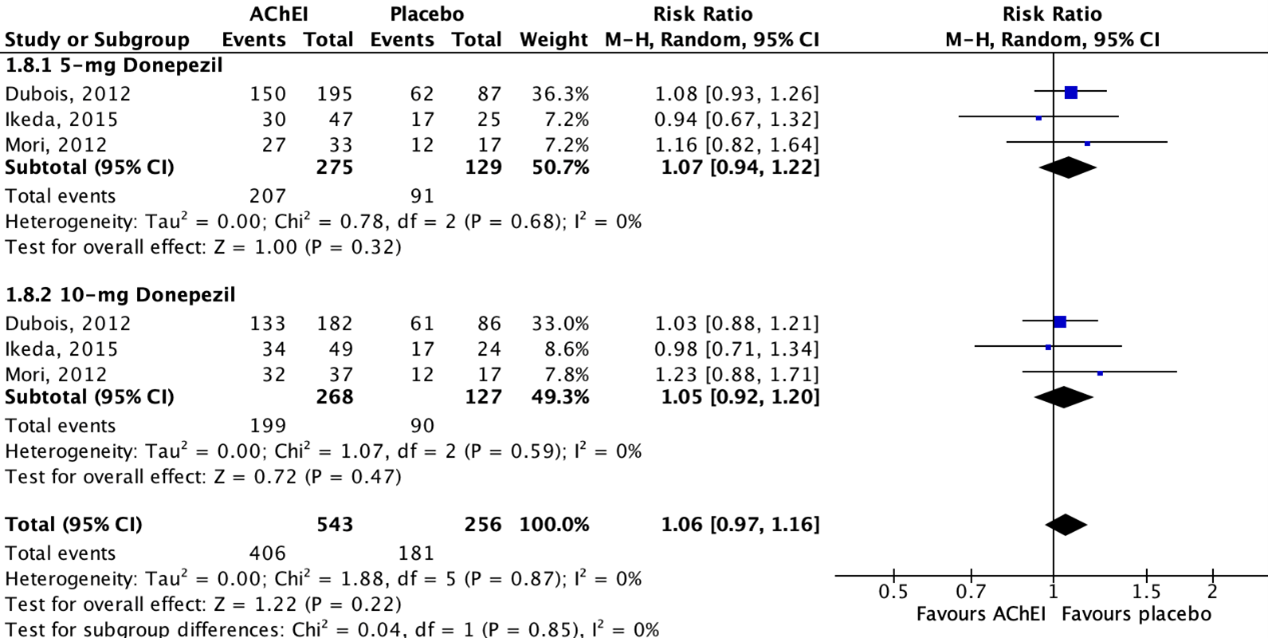

Three studies reported on adverse events in a PDD/DLB population, defined as the proportion of participants that experienced any adverse event (e.g., nausea, tremor, diarrhea, fall, insomnia, vomiting, hallucination, anorexia, confusional state, urinary tract infection, weight loss, back pain, dizziness, constipation) (Dubois, 2012; Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015).

Figure 4.2 shows that adverse events were reported in 74.8% (406/543) of patients in the intervention group and in 70.7% (181/256) of patients in the placebo group. The overall pooled data show a risk ratio of 1.06 (95%CI 0.97 to 1.16), favoring placebo. This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 4.1: The effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors treatment on adverse events in an AD population with subgroups for different treatments/doses.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 4.2: The effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors treatment on adverse events in a PDD/DLB population with subgroups for different treatments/doses.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Level of evidence of the literature

Additionally, the conclusions that dated from 2014 (see Appendix 1) were compared to the latest version of the NICE guideline (2018) and remained valid.

1. Cognitive function

1.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

The level of evidence regarding cognitive function was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1) and the confidence interval is crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

1.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

The level of evidence regarding cognitive function was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1) and the confidence interval is crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

2. Functional performance in activities of daily living

2.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

The level of evidence regarding functional performance in activities of daily living was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1) and the confidence interval is crossing the border of clinical relevance (imprecision: -1).

2.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

The level of evidence regarding functional performance in activities of daily living was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), and missing dispersion measures resulting in the inability to calculate effect measures (imprecision: -1).

3. Neuropsychiatric symptoms

3.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

The level of evidence regarding neuropsychiatric symptoms was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1) and conflicting results (inconsistency: -1).

3.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

The level of evidence regarding neuropsychiatric symptoms was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1) and due to the wide confidence intervals of the individual studies (imprecision: -2).

4. Caregiver burden

4.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

None of the studies reported on caregiver burden in an AD population and could therefore not be graded.

4.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

The level of evidence regarding caregiver burden was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), the low number of included patients, and the wide confidence intervals of the individual studies (imprecision: -2).

5. Quality of life

5.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

The level of evidence regarding quality of life was downgraded by two levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), the low number of included patients, and missing absolute values in more than half of the studies (imprecision: -2).

5.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

None of the studies reported on quality of life in a PDD/DLB population and could therefore not be graded.

6. Adverse events

6.1 Alzheimer’s Disease

The level of evidence regarding adverse events was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), the wide confidence intervals of the individual studies for donepezil and the low number of included patients for galantamine and rivastigmine (imprecision: -1).

6.2 Parkinson’s Disease Dementia/Lewy Body Dementia

The level of evidence regarding adverse events was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias: -1), and the broad confidence intervals of the individual studies (imprecision: -1).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors compared with placebo for patients with dementia?

P: Adults with dementia

I: Cholinesterase inhibitors (rivastigmine, galantamine, donepezil)

C: Placebo, no cholinesterase inhibitors

O: Cognitive function, functional performance in activities of daily living, neuropsychiatric symptoms, caregiver burden, quality of life, adverse events

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered cognitive function, functional performance in activities of daily living, and neuropsychiatric symptoms as critical outcome measures for decision making and caregiver burden, quality of life and adverse events as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

Cognitive function, as assessed by:

- Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog): ≥2 points (Landsdall, 2023)

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): ≥2 points (Landsdall, 2023)

In all other cases, the working group defined a 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (0.8 ≥ RR ≥ 1.25) and 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. For standardized mean differences (SMD), results were clinically relevant if they were smaller than -0.5 or higher than 0.5.

Search and select (Methods)

In 2014, this module was based on the NICE guideline (NICE, 2011) and supplemented with four trials (Burns, 2009; Cummings, 2012; Howard, 2012; Roman, 2010) and two systematic reviews (Kim, 2011; Farrimond, 2012) that were found through an additional literature search. The literature summary and conclusions including references are shown in Appendix 1. In 2023, the search was updated. The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2011 (last search) until 20 June 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 502 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews (search date from 2017, searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available);

- Studies including at least twenty participants (ten per arm);

- Full-text English language publication;

- Studies according to the PICO.

Twenty-seven studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, twenty-three studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and four systematic reviews (Jin, 2019; Watts, 2023; Knight, 2018; Dou, 2018) were included. Considering the broad search strategy in these systematic reviews, only RCTs that were conform our PICO and selection criteria were extracted and analyzed. Thus, sixteen RCTs (Dubois, 2012; Mori, 2012; Ikeda, 2015; Maher-Edwards, 2011; Haig, 2014; Jia, 2017; Marek, 2014; Maher-Edwards, 2015; Frölich, 2011; Gault, 2015; Gault, 2016; Iranmanesh, 2012; Koch, 2014; Likitjaroen, 2011; Hager, 2014; Nakamura, 2011) were included from the four systematic reviews.

Results

Four systematic reviews, including sixteen relevant RCTs, were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Additionally, the conclusions that dated from 2014 (see Appendix 1) [as well as the results from the updated search in 2023] were compared to the latest version of the NICE guideline (2018) and were considered (still) valid. Dubois (2012), Mori (2012) and Ikeda (2015) were included in the NICE guideline (2018) as well.

Referenties

- Dou KX, Tan MS, Tan CC, Cao XP, Hou XH, Guo QH, Tan L, Mok V, Yu JT. Comparative safety and effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for Alzheimer's disease: a network meta-analysis of 41 randomized controlled trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018 Dec 27;10(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0457-9. PMID: 30591071; PMCID: PMC6309083.

- Dubois B, Tolosa E, Katzenschlager R, Emre M, Lees AJ, Schumann G, Pourcher E, Gray J, Thomas G, Swartz J, Hsu T, Moline ML. Donepezil in Parkinson's disease dementia: a randomized, double-blind efficacy and safety study. Mov Disord. 2012 Sep 1;27(10):1230-8. doi: 10.1002/mds.25098. Epub 2012 Aug 22. PMID: 22915447.

- Frölich L, Ashwood T, Nilsson J, Eckerwall G; Sirocco Investigators. Effects of AZD3480 on cognition in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: a phase IIb dose-finding study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(2):363-74. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101554. PMID: 21258153.

- Gault LM, Ritchie CW, Robieson WZ, Pritchett Y, Othman AA, Lenz RA. A phase 2 randomized, controlled trial of the ?7 agonist ABT-126 in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's dementia. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2015 Jun 23;1(1):81-90. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.06.001. PMID: 29854928; PMCID: PMC5974973.

- Gault LM, Lenz RA, Ritchie CW, Meier A, Othman AA, Tang Q, Berry S, Pritchett Y, Robieson WZ. ABT-126 monotherapy in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's dementia: randomized double-blind, placebo and active controlled adaptive trial and open-label extension. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016 Oct 18;8(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0210-1. PMID: 27756421; PMCID: PMC5067903.

- Hager K, Baseman AS, Nye JS, Brashear HR, Han J, Sano M, Davis B, Richards HM. Effects of galantamine in a 2-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014 Feb 21;10:391-401. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S57909. Erratum in: Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1997. PMID: 24591834; PMCID: PMC3937252.

- Haig GM, Pritchett Y, Meier A, Othman AA, Hall C, Gault LM, Lenz RA. A randomized study of H3 antagonist ABT-288 in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(3):959-71. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140291. PMID: 25024314.

- Huo Z, Lin J, Bat BKK, Chan TK, Yip BHK, Tsoi KKF. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacological therapies for people with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2022 Apr 20;20(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12962-022-00354-3. PMID: 35443684; PMCID: PMC9022294.

- Ikeda M, Mori E, Matsuo K, Nakagawa M, Kosaka K. Donepezil for dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized, placebo-controlled, confirmatory phase III trial. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015 Feb 3;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0083-0. PMID: 25713599; PMCID: PMC4338565.

- Iranmanesh F, Vakilian A, Gadari F, Sayyadi A, Mehrabian M, Moradi M et al . Piracetam, Rivastigmine and Their Joint Consumption Effects on MMSE Score Status in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease. 3 2012; 11 (2) :60-0 URL: http://ijpt.iums.ac.ir/article-1-244-en.html

- Jia J, Wei C, Jia L, Tang Y, Liang J, Zhou A, Li F, Shi L, Doody RS. Efficacy and Safety of Donepezil in Chinese Patients with Severe Alzheimer's Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56(4):1495-1504. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161117. PMID: 28157100.

- Jin B, Liu H. Comparative efficacy and safety of therapy for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systemic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2019 Oct;266(10):2363-2375. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09200-8. Epub 2019 Jan 21. PMID: 30666436.

- Knight R, Khondoker M, Magill N, Stewart R, Landau S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine in Treating the Cognitive Symptoms of Dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2018;45(3-4):131-151. doi: 10.1159/000486546. Epub 2018 May 7. PMID: 29734182.

- Koch G, Di Lorenzo F, Bonnì S, Giacobbe V, Bozzali M, Caltagirone C, Martorana A. Dopaminergic modulation of cortical plasticity in Alzheimer's disease patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014 Oct;39(11):2654-61. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.119. Epub 2014 May 26. PMID: 24859851; PMCID: PMC4207345.

- Lansdall, C.J., McDougall, F., Butler, L.M. et al. Establishing Clinically Meaningful Change on Outcome Assessments Frequently Used in Trials of Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer's Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 10, 9-18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2022.102

- Likitjaroen Y, Meindl T, Friese U, Wagner M, Buerger K, Hampel H, Teipel SJ. Longitudinal changes of fractional anisotropy in Alzheimer's disease patients treated with galantamine: a 12-month randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012 Jun;262(4):341-50. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0234-2. Epub 2011 Aug 5. PMID: 21818628.

- Maher-Edwards G, Dixon R, Hunter J, Gold M, Hopton G, Jacobs G, Hunter J, Williams P. SB-742457 and donepezil in Alzheimer disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011 May;26(5):536-44. doi: 10.1002/gps.2562. Epub 2010 Sep 24. PMID: 20872778.

- Maher-Edwards G, Watson C, Ascher J, Barnett C, Boswell D, Davies J, Fernandez M, Kurz A, Zanetti O, Safirstein B, Schronen JP, Zvartau-Hind M, Gold M. Two randomized controlled trials of SB742457 in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2015 May 7;1(1):23-36. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.04.001. PMID: 29854923; PMCID: PMC5974972.

- Marek GJ, Katz DA, Meier A, Greco N 4th, Zhang W, Liu W, Lenz RA. Efficacy and safety evaluation of HSD-1 inhibitor ABT-384 in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 Oct;10(5 Suppl):S364-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.09.010. Epub 2014 Jan 10. PMID: 24418055.

- Mori E, Ikeda M, Kosaka K; Donepezil-DLB Study Investigators. Donepezil for dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Neurol. 2012 Jul;72(1):41-52. doi: 10.1002/ana.23557. PMID: 22829268; PMCID: PMC3504981.

- Nakamura Y, Imai Y, Shigeta M, Graf A, Shirahase T, Kim H, Fujii A, Mori J, Homma A. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of the rivastigmine patch in Japanese patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2011 Jan;1(1):163-79. doi: 10.1159/000328929. Epub 2011 Jun 24. PMID: 22163242; PMCID: PMC3199883.

- NICE guideline [NG97]. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. Published 20 June 2018. URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97

- Parsons C, Lim WY, Loy C, McGuinness B, Passmore P, Ward SA, Hughes C. Withdrawal or continuation of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine or both, in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Feb 3;2(2):CD009081. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009081.pub2. PMID: 35608903; PMCID: PMC8094886.

- Medicijnkosten.nl. https://www.medicijnkosten.nl (geraadpleegd op 20 november 2023).

- Watts KE, Storr NJ, Barr PG, Rajkumar AP. Systematic review of pharmacological interventions for people with Lewy body dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2023 Feb;27(2):203-216. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2022.2032601. Epub 2022 Feb 2. PMID: 35109724.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Watts, 2023 |

SR of RCTs

Literature search up to 1 July 2020

A: Dubois, 2012 B: Mori, 2012 C: Ikeda, 2015

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over]

Setting and Country: Nottingham, UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The SR was completed as a part of MSc mental health research. No specific grants from any funding source, commercial or not-for-profit sectors were received. No potential conflict of interest was reported. |

Inclusion criteria SR: - Participants had clinical diagnoses of DLB or PDD. - Study investigated the efficacy of at least one pharmacological intervention. - At least one of the primary or secondary study outcomes was changes in cognition, motor symptoms, activities of daily living, neuropsychiatric symptoms, QoL, hospitalisation, institutionalisation, mortality, carers’ burden or adverse effects.

Exclusion criteria SR: - Study investigating only people with PD without dementia. - Study did not report LBD data separately. - Opinion papers or reviews. - Not published in English.

135 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, mean (SD) age A: I1: 195 patients, 72.0 (6.83) years I2: 182 patients, 70.8 (7.46) years C: 173 patients, 72.9 (6.48) years

B: I1: 32 patients, 77.9 (6.8) years I2: 36 patients, 78.6 (6.1) years C: 35 patients, 78.6 (4.7) years

C: I1: 45 patients, 78.8 (5.1) years I2: 49 patients, 77.7 (6.8) years C: 44 patients, 77.2 (6.1) years

Sex (%male): A: I1: 65% I2: 75% C: 65%

B: I1: 50.0% I2: 11.1% C: 28.1%

C: I1: 44.4% I2: 42.9% C: 38.6%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. |

Describe intervention: A: I1: Donepezil 5 mg plus placebo once daily I2: Donepezil 10 mg once daily

B: I1: Donepezil 5 mg plus placebo once daily I2: Donepezil 10 mg once daily

C: I1: Donepezil 5 mg plus placebo once daily I2: Donepezil 10 mg once daily

|

Describe control: A: Two placebo tablets once daily

B: Two placebo tablets once daily

C: Two placebo tablets once daily

|

Endpoint of follow-up: A: 24 weeks B: 12 weeks C: 12 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: I1: 48 patients (24.1%) I2: 43 patients (23.6%) C: 31 patients (17.9%)

B: I1: 2 patients (6.1%) I2: 6 patients (16.2%) C: 5 patients (14.3%)

C: I1: 16 patients (34.0%) I2: 6 patients (12.2%) C: 9 patients (19.6%)

|

Cognitive function Assessed using ADAS-cog or MMSE A: I1: -2.43 I2: -2.43 C: -0.98 B: I1: 3.4 (3.2) I2: 2 (3.3) C: -0.4 (2.7) C: I1: 1.4 (3.4) I2: 2.2 (2.9) C: 0.6 (3)

Performance of activities in daily living Assessed using DAD and SE scales A: I1: 0.28 (DAD), -1.34 (SE) I2: 0.25 (DAD), -1.00 (SE) C: -1.99 (DAD), -0.66 (SE)

Neuropsychiatric symptoms Assessed using NPI A: I1: -1.87 I2: -1.49 C:-0.34 B: I1: -5.5 (6.7) I2: -8 (12.8) C: 0.3 (17.5) C: I1: -3.3 (9.4) I2: -5.5 (9.8) C: -6.4 (7.0)

Caregiver burden Assessed using ZBI B: I1: -0.7 (15.7) I2: -5.0 (13.6) C: 4.2 (10.4) C: I1: -5.0 (12.1) I2: -0.8 (11.9) C: -0.1 (8.4)

Adverse events A: I1: 150/195 I2: 133/182 C: 123/173 B: I1: 27/33 I2: 32/37 C: 24/34 C: I1: 30/47 I2: 34/49 C: 34/49 |

Risk of bias Tool used by authors: Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies

A: Some concerns B: Low C: Some concerns |

|

Jin, 2019 |

SR and Bayesian network meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to 1 August 2018

A: Maher-Edwards, 2011 B: Haig, 2014 C: Jia, 2017

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over]

Setting and Country: Shenyang, China

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by the national natural science foundation of Liaoning province (20170541036). The authors declare no competing interest. |

Inclusion criteria: - Patients with a diagnosis of dementia. - Study investigated the efficacy and safety of pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatments of BPSD. - Placebo, usual care, and any other corresponding (non-)pharmacological intervention were eligible. - Efficacy had to be assessed by using NPI or CMAI.

Exclusion criteria: - Observational studies, single arm noncomparative studies, review articles, nonhuman studies, and studies with incorrect comparator.

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, mean (SD) age A: I: 67 patients, 71.1 (8.4) years C: 61 patients, 71.6 (6.7) years

B: I: 60 patients, 70.5 (8.3) years C: 63 patients, 70.3 (7.8) years

C: I: 157 patients, 71.6 (8.6) years C: 156 patients, 70.0 (9.6) years

Sex (%male) A: I: 37% C: 30%

B: I: 40.0% C: 38.1%

C: I: 32.5% C: 37.8% |

Describe intervention: A: Donepezil 10 mg plus placebo once daily

B: Donepezil 10 mg plus placebo once daily

C: Donepezil 10 mg plus placebo once daily

|

Describe control: A: Placebo orally once daily

B: Placebo orally once daily

C: Placebo orally once daily

|

Endpoint of follow-up: A: 24 weeks B: 12 weeks C: 24 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: I: 10 patients (15%) C: 15 patients (25%)

B: I: 19 patients (31.7%) C: 25 patients (39.7%)

C: I: 29 patients (18.5%) C: 30 patients (19.2%) |

Cognitive function Assessed using ADAS-cog and MMSE A: I: -1.5 (5.9) C: -0.3 (6.0) B: I: -3.4 (5.2) C: -1.3 (5.2) C: I: 1.7 (3.1) C: 1 (3.3)

Performance of activities in daily living Assessed using ADCS-ADL B: I: -2.2 (6.6) C: -0.4 (6.6)

Neuropsychiatric symptoms Assessed using NPI B: I: -0.7 (6.2) C: -1 (6.2)

Quality of life Assessed using QoL-AD B: Subject score I: 0.6 (4.4) C: 0.2 (4.6)

Caregiver score I: -0.3 (3.7) C: 0.3 (3.7)

Adverse events A: I: 26/67 C: 18/62 B: I: 30/60 C: 25/63 C: I: 42/157 C: 26/156 |

Risk of bias Tool used by authors: Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

A: Some concerns B: Some concerns C: Some concerns |

|

Dou, 2018 |

Network meta-analysis

Literature search up to 21 July 2017

A: Hager, 2014 B: Nakamura, 2011

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over]

Setting and Country: Qingdao, China

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors was received. The authors declare to have no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria: - Completed double-blind RCTs with follow-up of 12-104 weeks with English language publication. - Comparison of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, or memantine alone or in combination with placebo or other treatments. - Drug dosages were specific and within the therapeutic range. - Eligible participants had a clinical diagnosis for dementia. - Criteria for disease severity classification were reasonable. - At least one of the five outcomes of cognition, function, behavior, global assessment, or adverse events was covered.

Exclusion criteria: - Quasi-randomized trials, trials with too short-term or too long-term follow-up. - Trials that included patients with mixed dementia or neuropsychiatric symptoms. - Trials that recruited fewer than 10 participants per group.

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, mean (SD) age A: I: 1024, 73.0 (8.9) years C: 1021, 73.0 (8.7) years B: I (5cm2): 282, 74.3 (7.5) years I (10cm2): 287, 75.1 (6.9) years C: 286, 74.5 (7.4) years

Sex (%male) A: I: 34.5% C: 35.9% B: I (5cm2): 31.2% I (10cm2): 32.1% C: 31.8% |

Describe intervention: A: Galantamine oral extended release capsule of 24 mg with matching placebo

B: I (5 cm2): 5 cm2 rivastigmine patch, 9 mg loading dose; 4.6 mg/24h delivery rate I (10 cm2): 10 cm2 rivastigmine patch, 18 mg loading dose; 9.5 mg/24h delivery rate |

Describe control: A: Placebo

B: Placebo

|

Endpoint of follow-up: A: 104 weeks B: 24 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: I: 689 (68%) C: 701 patients (69%)

B: I (5 cm2): 64 patients (22.5%) I (10 cm2): 59 patients (20.6%) C: 46 patients (16%) |

Cognitive function Assessed using ADAS-cog and MMSE A: I: -1.41 C: -2.14 B: I (5 cm2): 0.1 (5.0) I (10 cm2): 0.5 (5.0) C: 1.3 (5.1)

Performance of activities in daily living Assessed using DAD scale A: I: 8.16 (17.25) C: 10.81 (18.27) B: I (5 cm2): 3 (10.26) I (10 cm2): 1.9 (10.66) C: 4.2 (12.44)

Adverse events A: I: 553/1024 C: 496/1021 B: I (5 cm2): 243/282 I (10 cm2): 248/287 C: 222/286

|

Risk of bias Tool used by authors: Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

A: Some concerns B: Some concerns

|

|

Knight, 2018 |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to March 2017

A: Marek, 2014 B: Maher-Edwards, 2015 C: Iranmanesh, 2012 D: Frölich, 2011 E: Gault, 2015 F: Gault, 2016 G: Koch, 2014 H: Likitjaroen, 2011

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over]

Setting and Country: London, UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The authors declare to have no conflicts of interests. |

Inclusion criteria: - Randomized trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of AChEI monotherapy, memantine monotherapy, or memantine treatment in a group of patients some, but not all, who received a concurrent AChEI. - Treatments compared to a control group receiving placebo or no treatment. - Participants in the trial diagnosed with AD, VaD, PDD, DLB or FTD. - Either the MMSE or the ADAS-cog or both used as an outcome. - Sufficient data provided.

Exclusion criteria: Not further specified.

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, mean (SD) age A: I: 66, 71.8 (8.4) years C: 66, 71.7 (9.0) years B: I: 147, 71.1 (7.5) years C: 135, 73.3 (6.8) years C: 16, 75.3 (2.3) years D: I: 158, 73.9 (6.5) years C: 163, 73.5 (6.4) years E: I: 68, 73.9 (7.9) years C: 68, 73.6 (8.2) years F: I: 75, 75.1 (7.8) years C: 104, 73.2 (7.4) years G: I: 10, 70.5 (4.8) C: 10, 66.9 (6.1) H: I: 14, 73.5 (7.2) C: 11, 76.4 (7.9)

Sex (%male) A: I: 47% C: 39.4% B: I: 35% C: 36% C: 50% D: I: 34.2% C: 44.8% E: I: 54.4% C: 38.2% F: I: 46.7% C: 37.5% G: I: 50% C: 40% H: I: 43% C: 36% |

Describe intervention A: Donepezil 10 mg

B: Donepezil 5-10 mg

C: Rivastigmine 3 mg

D: Donepezil 10 mg

E: Donepezil 10 mg

F: Donepezil 10 mg

G: Rivastigmine 4.6 mg

H: Galantamine 16 mg |

Describe control A: Placebo

B: Placebo

C: Placebo

D: Placebo

E: Placebo

F: Placebo

G: Placebo

H: Placebo |

Endpoint of follow-up: A: 12 weeks B: 24 weeks C: 12 weeks D: 12 weeks E: 12 weeks F: 24 weeks G: 12 weeks H: 12 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: I: 29 patients (43.9%) C: 22 patients (33.3%) B: I: 21 patients (13.8%) C: 27 patients (18.6%) C: I: NR C: NR D: I: 22 patients (13.8%) C: 19 patients (11.6%) E: I: 6 patients (8.8%) C: 6 patients (8.6%) F: I: 15 patients (19.7%) C: 15 patients (14.4%) G: I: NR C: NR H: I: 7 patients (50%) C: 3 patients (27.3%)

|

Cognitive function Assessed using ADAS-cog and MMSE B: I: -0.5 (5.3) C: -0.3 (6.2) C: I: 18/3750 (3/36403) C: 14/1250 (3/87943) D: I: -1.1 (5.3) C: -0.3 (5.3) E: I: -2.11 (5.2) C: -0.68 (5.2) F: I: -2.6 (5.8) C: -0.31 (5.7) G: I: 23.0 (8.2) C: 22.8 (3.4) H: I: 20.4 (1.9) C: 22.0 (3.5)

Performance of activities in daily living Assessed using ADCS-ADL and DAD scale B: I: 1.2 (9.7) C: 1 (8.0) D: I: 0.8 (14.8) C: 2.6 (14.7) E: I: -2.95 (7.0) C: -1.58 (7.0) F: I: -1.71 (7.6) C: 2.3 (7.5)

Neuropsychiatric symptoms Assessed using NPI A: I: -2.13 C: 0.35 E: I: -1.92 (8.4) C: -3 (8.5) F: I: -2.72 (8.2) C: -0.26 (8.1)

Quality of life Assessed using QoL-AD E: Subject score I: 0.24 (4.1) C: 1.19 (4.2)

Caregiver score I: 0.02 (3.8) C: 0.44 (3.8)

Adverse events A: I: 39/66 C: 37/66 B: I: 65/151 C: 45/145 D: I: 60/160 C: 60/164 E: I: 29/68 C: 26/68 F: I: 47/75 C: 56/104 |

Risk of bias Tool used by authors: Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

A: High B: High C: Some concerns D: Some concerns E: Low F: Some concerns G: Some concerns H: Some concerns

|

Table of excluded studies

Full-text selection

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Takramah WK, Asem L. The efficacy of pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive and behavior symptoms in people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci Rep. 2022 Nov 6;5(6):e913. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.913. PMID: 36381407; PMCID: PMC9637987. |

Search period is unknown |

|

Veroniki AA, Ashoor HM, Rios P, Seitidis G, Stewart L, Clarke M, Tudur-Smith C, Mavridis D, Hemmelgarn BR, Holroyd-Leduc J, Straus SE, Tricco AC. Comparative safety and efficacy of cognitive enhancers for Alzheimer's dementia: a systematic review with individual patient data network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022 Apr 26;12(4):e053012. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053012. PMID: 35473731; PMCID: PMC9045061. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Battle CE, Abdul-Rahim AH, Shenkin SD, Hewitt J, Quinn TJ. Cholinesterase inhibitors for vascular dementia and other vascular cognitive impairments: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Feb 22;2(2):CD013306. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013306.pub2. PMID: 33704781; PMCID: PMC8407366. |

All relevant studies (according to PICO: Mok, 2007) are published before 2011 |

|

Seibert M, Mühlbauer V, Holbrook J, Voigt-Radloff S, Brefka S, Dallmeier D, Denkinger M, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C, Klöppel S, von Arnim CAF. Efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy for Alzheimer's disease and for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in older patients with moderate and severe functional impairments: a systematic review of controlled trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021 Jul 16;13(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00867-8. PMID: 34271969; PMCID: PMC8285815. |

All relevant studies (according to PICO: Burns, 2009; Tariot, 2001) are published before 2011 |

|

Chu CS, Yang FC, Tseng PT, Stubbs B, Dag A, Carvalho AF, Thompson T, Tu YK, Yeh TC, Li DJ, Tsai CK, Chen TY, Ikeda M, Liang CS, Su KP. Treatment Efficacy and Acceptabilityof Pharmacotherapies for Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021 Sep-Oct;96:104474. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104474. Epub 2021 Jul 2. PMID: 34256210. |

Includes the same studies as Watts (2023) which has a more recent search period |

|

Trieu C, Gossink F, Stek ML, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YAL, Dols A. Effectiveness of Pharmacological Interventions for Symptoms of Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia: A Systematic Review. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020 Mar;33(1):1-15. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0000000000000217. PMID: 32132398. |

Includes one relevant study (according to PICO) but is published before 2011 |

|

Fink HA, Hemmy LS, Linskens EJ, Silverman PC, MacDonald R, McCarten JR, Talley KMC, Desai PJ, Forte ML, Miller MA, Brasure M, Nelson VA, Taylor BC, Ng W, Ouellette JM, Greer NL, Sheets KM, Wilt TJ, Butler M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Clinical Alzheimer’s-Type Dementia: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2020 Apr. Report No.: 20-EHC003. PMID: 32369312. |

Wrong population (probable AD) |

|

Li DD, Zhang YH, Zhang W, Zhao P. Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials on the Efficacy and Safety of Donepezil, Galantamine, Rivastigmine, and Memantine for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci. 2019 May 15;13:472. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00472. PMID: 31156366; PMCID: PMC6529534. |

No risk of bias assessment performed, and relevant studies (Frölich, 2011; Haig, 2014; Gault, 2015/6; Jia, 2017; Maher-Edwards, 2011) are included in Knight (2018) as well |

|

Meng YH, Wang PP, Song YX, Wang JH. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for Parkinson's disease dementia and Lewy body dementia: A meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2019 Mar;17(3):1611-1624. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.7129. Epub 2018 Dec 24. PMID: 30783428; PMCID: PMC6364145. |

All relevant studies (according to PICO: Ravina, 2005; McKeith, 2000; Leroi, 2004; Emre, 2004) are published before 2011 |

|

Chen YD, Zhang J, Wang Y, Yuan JL, Hu WL. Efficacy of Cholinesterase Inhibitors in Vascular Dementia: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Eur Neurol. 2016;75(3-4):132-41. doi: 10.1159/000444253. Epub 2016 Feb 27. PMID: 26918649. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Zhang, Xiaoli & Shao, Junhui & Wei, Yawei & Zhang, Hui. (2016). Efficacy of galantamine in treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: An update meta-analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 9. 7423-7430. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Kobayashi H, Ohnishi T, Nakagawa R, Yoshizawa K. The comparative efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 Aug;31(8):892-904. doi: 10.1002/gps.4405. Epub 2015 Dec 17. PMID: 26680338; PMCID: PMC6084309. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Stinton C, McKeith I, Taylor JP, Lafortune L, Mioshi E, Mak E, Cambridge V, Mason J, Thomas A, O'Brien JT. Pharmacological Management of Lewy Body Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Aug 1;172(8):731-42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121582. Epub 2015 Jun 18. PMID: 26085043. |

Includes the same studies as Watts (2023) which has a more recent search period |

|

Jiang D, Yang X, Li M, Wang Y, Wang Y. Efficacy and safety of galantamine treatment for patients with Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2015 Aug;122(8):1157-66. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1358-0. Epub 2014 Dec 30. PMID: 25547862. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Tan CC, Yu JT, Wang HF, Tan MS, Meng XF, Wang C, Jiang T, Zhu XC, Tan L. Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(2):615-31. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132690. PMID: 24662102. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Wang HF, Yu JT, Tang SW, Jiang T, Tan CC, Meng XF, Wang C, Tan MS, Tan L. Efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease, Parkinson's disease dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015 Feb;86(2):135-43. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307659. Epub 2014 May 14. PMID: 24828899. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Wang J, Yu JT, Wang HF, Meng XF, Wang C, Tan CC, Tan L. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015 Jan;86(1):101-9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308112. Epub 2014 May 29. PMID: 24876182. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Di Santo SG, Prinelli F, Adorni F, Caltagirone C, Musicco M. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, and memantine in relation to severity of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35(2):349-61. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122140. PMID: 23411693. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Rolinski M, Fox C, Maidment I, McShane R. Cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease dementia and cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Mar 14;2012(3):CD006504. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006504.pub2. PMID: 22419314; PMCID: PMC8985413. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Herrmann N, Chau SA, Kircanski I, Lanctôt KL. Current and emerging drug treatment options for Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Drugs. 2011 Oct 22;71(15):2031-65. doi: 10.2165/11595870-000000000-00000. PMID: 21985169. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Su J, Liu Y, Liu Y, Ren L. Long-term effectiveness of rivastigmine patch or capsule for mild-to-severe Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15(9):1093-103. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1068120. Epub 2015 Aug 6. PMID: 26289489. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Zhao J, Gou YJ, Peng, XL, Yan W, Xie SP, Fan CX. Donepezil in the treatment of senile vascular dementia: a systematic review. Chinese Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011;11(11):1280-89. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

|

Ma Z, Chen Y, Feng WY. A system review of efficacy of donepezil in treatment of vascular dementia. Chinese Journal of New Drugs. 2013;22(5):569-76. |

Search period is prior to 2017 |

Study selection from systematic reviews

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Watts, 2023 |

|

|

Beversdorf, 2004 |

Published prior to 2011 |

|

Leroi, 2004 |

Published prior to 2011 |

|

Ravina, 2005 |

Published prior to 2011 |

|

McKeith, 2000 |

Published prior to 2011 |

|

Emre, 2004 |

Published prior to 2011 |

|

Poewe, 2006 |

Published prior to 2011 |

|

Litvinenko, 2008 |

Published prior to 2011 |

|

Jin, 2019 |

|

|