Indicatie immobilisatie en beeldvorming

Uitgangsvraag

Welke traumapatiënten zijn verdacht voor acuut traumatisch wervelletsel, en zouden moeten worden geïmmobiliseerd voorafgaand aan beeldvorming?

Aanbeveling

Cervicale wervelkolom

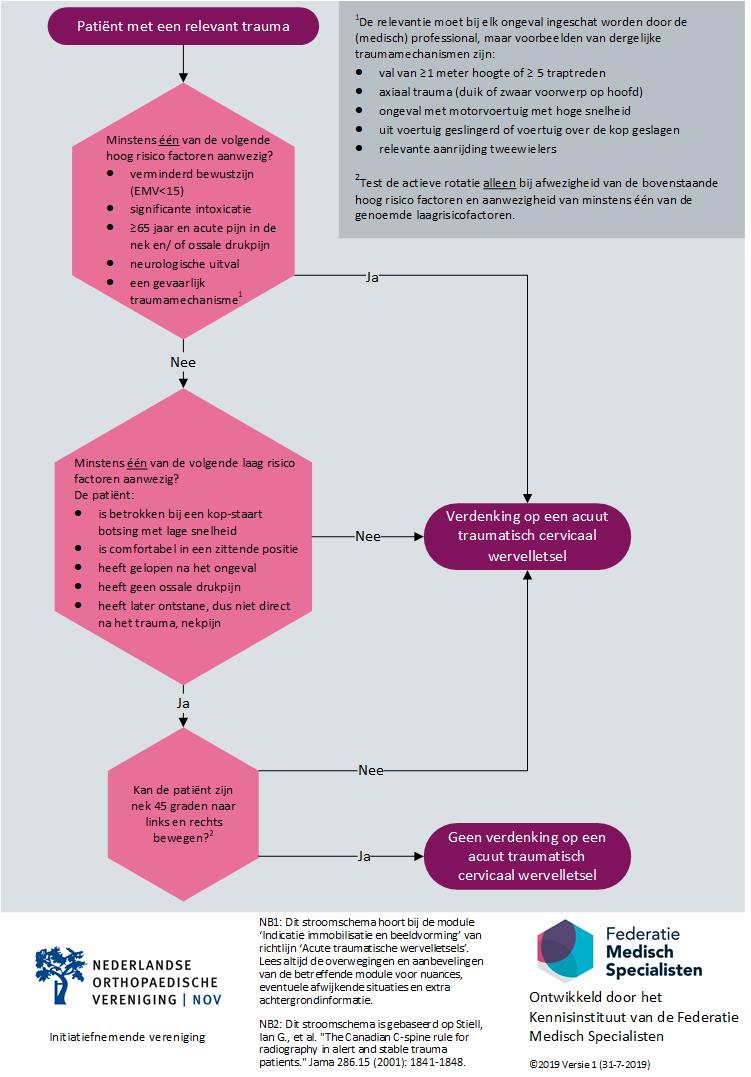

Immobiliseer een patiënt die verdacht wordt van het hebben van een cervicaal acuut traumatisch wervelletsel. Gebruik het stroomschema om te bepalen er sprake is van een verdenking op een acuut traumatisch cervicaal wervelletsel.

Bij twijfel, verdenk de patiënt van het hebben van een cervicaal acuut traumatische wervelletsel.

Verkrijg beeldvorming indien de verdenking (na eventuele herbeoordeling) op de SEH persisteert. Voor de keuze met betrekking tot de beeldvorming kan de module ‘Screening met röntgenfoto’s of CT’ worden geraadpleegd.

Immobiliseer een patiënt met een scherp, penetrerend hals-/nekletsel niet.

Thoracolumbale wervelkolom

Immobiliseer elke patiënt bij wie er een verdenking is op een thoracolumbaal acuut traumatisch wervelletsel (zie ook onderstaand).

Verdenk patiënten van een thoracolumbaal acuut traumatisch wervelletsel indien er sprake is van relevant trauma en één van de volgende factoren:

- ≥ 65 jaar en pijn in TWK/LWK;

- verminderd bewustzijn;

- neurologische uitval;

- pijn of neurologische verschijnselen bij mobiliseren;

- drukpijn TWK/LWK;

- percussie pijn over de wervelkolom;

- pijn rug bij hoesten, niesen, persen;

- verdenking op een wervelfractuur in ander deel van de wervelkolom;

- bekende risicofactoren:

- langdurig gebruik steroïden;

- osteoporose;

- ankyloserende wervelkolom;

- operatieve ingreep wervelkolom in de voorgeschiedenis, tenzij het een enkelvoudige lumbale HNP operatie betrof.

- een gevaarlijk traumamechanisme, zoals

- val van > 3m hoogte;

- axiaal trauma (duik of zwaar voorwerp op hoofd);

- ongeval met motorvoertuig met hoge snelheid;

- uit voertuig geslingerd of voertuig over de kop geslagen;

- relevante aanrijding tweewielers;

- ongeval waarbij iemand een 2 punts gordel draagt;

- in aanraking gekomen met groot dier; bijvoorbeeld een val van een paard, trap van een koe en beklemming door een groot dier.

Verkrijg beeldvorming indien de verdenking (na eventuele herbeoordeling) op de SEH persisteert.

Overwegingen

Cervicale wervelkolom

Acute, traumatische, cervicale wervelletsels zijn relatief zeldzaam, maar dragen het risico op significante morbiditeit in zich (Nijendijk, 2010). De algemene aanname is dat immobilisatie verdere neurologische schade voorkomt of vermindert. Het immobiliseren van de CWK geeft, afhankelijk van techniek en situatie, echter ook risico op complicaties (White, 2013; Sundstrøm, 2014). De patiëntvertegenwoordiger in de werkgroep heeft zich bovenal voor veiligheid uitgesproken. De overige werkgroepleden delen deze mening.

Uit de literatuursamenvatting blijkt dat het onduidelijk is of de NEXUS-criteria voldoende sensitief zijn om als beslisregel te hanteren. Er zijn aanwijzingen dat de Canadian C-spine rules (CCR) voldoende sensitief zijn, maar dat dit wel ten koste gaat van de specificiteit. De wetenschappelijke onderbouwing over dit onderwerp blijkt summier. Het risico op significante morbiditeit in ogenschouw genomen en met de CCR als startpunt, heeft de werkgroep de volgende overwegingen en aanbevelingen geformuleerd.

Men moet bij elke ongevalspatiënt te allen tijde bedacht zijn op een acuut traumatisch wervelletsel. De NEXUS en CCR zijn beide klinische beslisregels die niet gebruikt mogen worden bij patiënten met een verminderd bewustzijn (EMV <15). De werkgroep beschouwt deze patiëntengroep dus als hoogrisico patienten.

De hoogrisicofactoren voor acuut traumatisch cervicaal wervelletsel zoals beschreven in de CCR zijn 1) een leeftijd van 65 jaar of ouder; 2) neurologische uitval of 3) een gevaarlijk traumamechanisme (Stiell, 2001).

De leeftijdsgrens van 65 jaar, zonder enige nuancering, wordt door de werkgroep als niet werkbaar geacht. Daarbij wil de werkgroep niet zeggen dat er bij deze patiënten geen verhoogd risico is op acuut traumatisch CWK-letsel. Dat heeft deze patiëntcategorie wel. Echter de werkgroep acht leeftijd als opzichzelfstaand criterium om patiënten te immobiliseren en zodoende te presenteren in het ziekenhuis ongeschikt. De werkgroep heeft gekozen om ‘acute pijn in de nek en/of ossale drukpijn’ te koppelen aan de leeftijdsgrens. Is er geen acute pijn in de nek en/of ossale drukpijn? Dan doorloopt de (medisch) professional de overige stappen van de CCR.

In de CCR is een aantal gevaarlijke traumamechanismen geformuleerd: 1) een val van > 1m; 2) axiaal trauma; 3) een ongeval met een motorrijtuig met hoge snelheid, waarbij het voertuig over de kop geslagen is of waarbij de patiënt uit het voertuig is geslingerd; 4) een aanrijding op de fiets; en 5) een ongeval met een camper (Stiell, 2001). Deze mechanismen worden door de werkgroep geschikt geacht om grofweg te bepalen of er aanleiding is voor een verdenking op acuut traumatisch cervicaal wervelletsel en immobilisatie. Er is hier echter wel een nadere toelichting nodig. Als eerste is de genoemde hoge snelheid niet nader gespecificeerd. Hoewel de werkgroep inziet dat hier een grensgetal wenselijk is, heeft ze ervoor gekozen om dit aan de beoordeling van de (medisch) professional over te laten. Als tweede is een aanrijding op de fiets niet verder geformuleerd. Ook hier moet de relevantie ingeschat worden. Twee fietsen met de sturen in elkaar betreft een andere situatie dan een aanrijding van een fietser door een auto. Als derde wil de werkgroep benadrukken dat deze opsomming niet exclusief is. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan een aanrijding van een voetganger, een val van de 2e trede van de trap met het hoofd tegen een kastje, een ongeval met andere voertuigen (of hulpmiddelen), zoals met brommers, snorfietsen, e-bikes en/of speed pedelecs en een direct inwerkend trauma op de wervelkolom. De werkgroep wil benadrukken dat de (medisch) professional een inschatting moet maken van de relevantie van het trauma voor het risico op traumatisch CWK-letsel. Een klinische beslisregel kan nooit alle relevante traumamechanismen opsommen.

Bij aanwezigheid van één van de hoogrisicofactoren, waarbij bovenstaande nuanceringen en toelichtingen gelden, is immobilisatie geïndiceerd.

In de CCR worden naast hoogrisicofactoren ook laagrisicofactoren benoemd, dit zijn: 1) betrokkenheid in een kop-staart botsing met lage snelheid; 2) comfortabel in een zittende positie; 3) gelopen heeft na het ongeval; 4) geen ossale drukpijn en 5) later ontstane, dus niet direct na het trauma, nekpijn.

Bij afwezigheid van al deze vijf laagrisicofactoren is immobilisatie geïndiceerd. Bij afwezigheid van de hoogrisicofactoren maar aanwezigheid van tenminste één van deze laagrisicofactoren persisteert het risico op een acute traumatisch wervelletsel als de patiënt de nek niet zelf 45 graden kan roteren in beide richtingen. Immobilisatie is dan dus geïndiceerd. Is rotatie wel mogelijk dan kan de immobilisatie en beeldvorming achterwegen gelaten worden.

Intoxicatie is niet opgenomen in de CCR. De NEXUS criteria benoemen dit wel als hoogriscofactor. Er is gekozen om de CCR te volgen, maar de relevantie van dit criterium wordt door de werkgroep onderschreven. Denk hierbij overigens ook aan een significante intoxicatie met voorgeschreven medicijnen. Een duidelijke definitie van intoxicatie, en zodoende veranderde pijnbeleving van de patiënt, is moeilijk te geven. De werkgroep heeft er daarom voor gekozen dit te formuleren als significante intoxicatie. De werkgroep is zich er van bewust dat dit een inschatting van de (medisch) professional is, maar wil deze factor niet onbenoemd laten.

Bovenstaande wordt ook schematisch weergegeven in het stroomschema. Bij twijfel raadt de werkgroep aan om de patiënt wel te immobiliseren.

Nota bene: Bij een patiënt met een penetrerend letsel kan er sprake zijn van pijn in de nek, maar dit betreft een belangrijke uitzondering. Deze patiënten dienen - zonder immobilisatie - zo spoedig mogelijk vervoerd te worden naar een, bij voorkeur voor dit letsel geëquipeerd, ziekenhuis (Velopulos, 2017, Haut, 2010).

Indien de indicatie immobilisatie CWK (na eventuele herbeoordeling) persisteert op de SEH, is het geïndiceerd beeldvorming te laten vervaardigen. Hierbij is er, conform de vorige richtlijn (NOV, 2009), een absolute indicatie voor CT. Deze aanbevelingen zullen vermoedelijk leiden tot een lichte stijging in het aantal CT-scans. Het uiteindelijk effect op kosten is hierbij onbekend.

Denk bij het aanvragen van de CT-scan ook aan de criteria voor het vervaardigen van een CT-hersenen zoals beschreven in de richtlijn licht traumatisch hoofd/hersenletsel (LTH; NVN, 2010). Omgekeerd moet er bij een LTH ook altijd gedacht worden aan acuut traumatisch wervelletsel met bijzonder aandacht voor de CWK.

Thoracolumbale wervelkolom

In onze literatuursamenvatting is slechts één studie gevonden die zich heeft gericht op de thoracolumbale wervelkolom, en de bewijskracht is zeer laag. Zodoende volgt de werkgroep wat betreft de verdenking op acuut traumatisch wervelletsel van de thoracolumbale wervelkolom de aanbevelingen in de NICE-richtlijn (NICE Guideline NG41; National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2016). Wel is de werkgroep van mening dat de risicofactor “val van paard” algemener geformuleerd dient te worden in Nederlandse context, en stelt voor om “in aanraking gekomen met groot dier, bijvoorbeeld een val van een paard, trap van een koe en beklemming door een groot dier” op te nemen. Ook bij de beoordeling van het risico op acuut traumatisch letsel van de thoracolumbale wervelkolom is het goed om te bedenken of het gaat om een relevant mechanisme. Een oudere die op de billen valt heeft net zo’n relevant mechanisme als een 30 jarige die van hoogte valt.

Figuur 1 Indicatie verdenking acuut traumatisch cervicaal wervelletsel

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In de vorige richtlijn staan de criteria voor het verkrijgen van beeldvorming - en daarbij dus voor immobilisatie - van de (cervicale) wervelkolom beschreven (NOV, 2009). Deze richtlijn wordt in het ziekenhuis gehanteerd bij een verdenking acuut traumatisch wervelletsel. Veranderingen in het Landelijk Protocol Ambulancezorg (LPA; 2014) zorgen voor een discrepantie in strategie en indicatiestelling van de zorgprofessionals binnen en buiten het ziekenhuis omtrent de immobilisatie van de (cervicale) wervelkolom. Op het moment van schrijven is LPA 8.1. (Ambulancezorg Nederland, 2016) van kracht. De vraag naar uniformiteit en eenduidigheid in de te volgen strategie heeft geleid tot de revisie van de richtlijn(module). Dit is voor patiënt en zorgprofessional van belang.

Conclusies

PICO 1: Cervical spine (C-spine) injury

|

Very Low GRADE |

It is not clear whether the NEXUS-criteria are sufficiently sensitive to be used as a decision tool.

References: (Benayoun, 2017; Dahlquist, 2015; Denver, 2015; Duane, 2011a, Duane, 2013; Goode, 2014; Griffith, 2011; Griffith, 2013; Hoffman, 1992, Hoffman, 2000; Rose, 2012; Touger, 2002) |

|

Low GRADE |

There are indications that the CCR is sufficiently sensitive to be used as a decision tool. However, there are also indications that its specificity is very low.

References: (Benayoun, 2017; Duane, 2011b, Duane, 2013; Griffith, 2013) |

PICO 2: Thoracolumbar spine (TL-spine) injury

|

Very Low GRADE |

It is unclear whether the decision tool as presented by Inaba, is sufficiently sensitive to diagnose a TL-spine fracture.

References: (Inaba, 2015) |

Samenvatting literatuur

PICO 1: Cervical spine (C-spine) injury

Description of included studies

NICE guideline

Chapter 7 of the NICE guideline (NICE Guideline NG41; National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2016) explores the diagnostic evidence of the tools used to predict spinal injury. The authors focused on spinal cord injury and spinal column injury in children, young adults and adults. The search was performed in March 2015.

Seven of the 13 included studies in the NICE guideline were also included in this literature analysis. One of these studies was described in two publications (Hoffman, 2000 Tougher, 2002). The remaining six studies were excluded because their study population consisted of children (Ehrlich, 2009, Viccellio, 2001) or telephone follow-up was used as the reference test in a part of the population (Coffey, 2011, Dickinson, 2004, Stiell, 2001, Stiell, 2003).

See table 1 for the study characteristics of the included studies. In the NICE guideline risk of bias was assessed using the QUADAS-2 criteria, but the risk of bias table was not published. We therefore decided to evaluate the risk of bias of the studies using the original papers.

In contrast to what is mentioned in the NICE guideline, the included study of Duane, 2011a did not evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the CCR, but determined the diagnostic accuracy of the NEXUS-criteria. This group had, however, also published a study on the diagnostic accuracy of the CCR (Duane, 2011b), and this study was separately included in this literature review, see below.

Other studies

Benayoun (2017) reviewed in a retrospective cross-sectional study the data of 3753 patients who received a C-spine CT scan. 760 of these patients had a history of a ground level fall (< 3ft or 5 stairs). A secondary aim of this study was to evaluate the appropriateness of imaging by NEXUS and CCR criteria. The endpoint of this study was the presence of a C-spine fracture.

There were seven C-spine fractures, one of these fractures was unstable. There was insufficient documentation of the indication of imaging for the NEXUS-criteria in 9.3% of the patients and in 29.9% for the CCR of the patients. This might influence the results presented.

Dhalquist (2015) evaluated in a retrospective cohort study whether the NEXUS-criteria remained sensitive if a femur fractur is no longer considered as a distracting injury and thus no longer as an absolute indication for diagnostic imaging. In total, the data of 566 blunt trauma patients with at least one femur fracture and who were evaluated for C-spine injury with imaging were included. In 98% of the patients a C-spine CT scan had been made. The patients had on average a score of 18.5 on the Injury Severity Score. The authors presented the diagnostic accuracy of the test in predicting cervical spine injury, although they previously defined the presence of C-spine injury warranting an operative intervention and eventual other interventions to be the primary outcome measure.

Denver (2017) evaluated in a cohort of 169 elderly with low-mechanism injuries the diagnostic accuracy of the NEXUS-criteria. Patients were categorized as NEXUS negative or NEXUS positive based on information on a data collection sheet. This sheet was filled out if it was decided to conduct a CT scan to rule out intracranial injury. The primary outcome measure was a significant cervical spine injury. Thirty patients were screened but excluded from the analyses because of incomplete data/imaging or because they were not eligible. The authors noted that serious selection bias may be present: “A review of medical records during the study period revealed that 46 eligible patients underwent CT imaging of the brain only, and another 22 patients had undergone CT imaging of both the brain and C-spine, but data forms were not filled-out.”

Duane (2011b) was a prospective cohort study evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of the CCR when applied in severe (meeting trauma team activation criteria) blunt trauma patients. The data of 3201 patients were included in the analyses. The complete C-spine CT-scan was used as the reference test. One hundred ninety-two patients suffered at least one fracture (incidence of 6%). The study sample comprised for a major part the same patients as the study sample included in Duane (2011a), and the data of this study were likely also included in their 2013 publication.

Goode (2014) was a prospective cohort study evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of the NEXUS tool applied in severe (meeting trauma team activation criteria) blunt trauma elderly and nonelderly patients. In total, the data of 320 elderly and 2465 nonelderly were included.

Rose (2012) evaluated in a prospective cohort study the diagnostic accuracy of cervical spine injury in awake and alert (GCS≥ 14) blunt trauma patients (> 13 years; n=761) with distracting injuries. Patients were included regardless of ethanol level. When patients did not have neurological deficits, neck pain or neck tenderness, also during flexion, extension and rotation, they were clinically cleared. Still all patients underwent CT scanning of the entire spine. Distraction injuries were categorized as ‘head injuries’, ‘torso injuries’ and ‘long bone fractures’. Two-hundred ninety-seven (39%) had a positive C-spine clinical examination and 85 of these patients (29%) and one patients that had been clinical cleared (0.2%) were diagnosed with C-spine injury.

Results

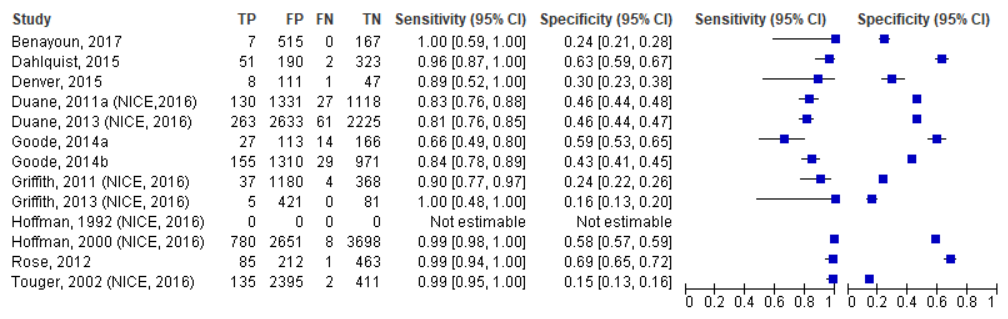

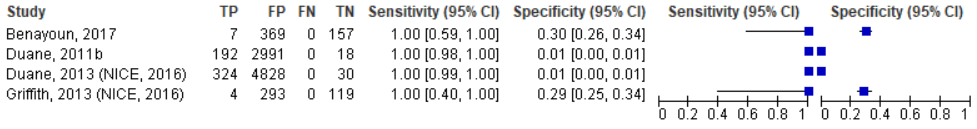

A short overview of the results is provided in table 1 and the results of the individual studies for the outcome measures ‘sensitivity’ and ‘specificity’ are also presented in the forests plots (figure 2 and 3).

Table 1 Results of the individual studies

|

Study reference |

Study design |

Nr. of patients |

Patient population |

Name test |

Reference test |

Outcome |

Sens (%),

|

Spec (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

Other remarks |

|

NEXUS-criteria |

|

||||||||||

|

Dahlquist, 2015 |

Retrospective cohort |

N=566 (children and adults) |

Blunt trauma patients with ≥ one femur fracture |

NEXUS criteria - femur fracture considered not a distracting injury |

Diagnostic imaging, (CT-scan in 98.4% of the patients) |

Cervical spine injury |

96.2 (85.9-99.3)

|

63.0 (58.6-67.1)

|

21.2 (16.3-27.0)

|

99.4 (97.5-99.9) |

|

|

Denver, 2015 |

Prospective cohort |

169 patients (>65 years of age) |

Elderly patients after a fall from standing height or less. |

NEXUS (“patients who could not be assessed for midline C-spine tenderness were considered positive”) |

CT-scan |

Clinically significant CSI (all injuries not deemed insignificant by NEXUS study) |

88.9 (50.7-99.4) |

30 |

6.7 |

98 (87.8-99.9) |

N=30 excluded due to incomplete data/imaging or did not comply with inclusion criteria. Spec and PPV are recalculated based on the provided study results (PPV: 8/120 and spec: 48/ (48+112)) |

|

Goode, 2014 |

Prospective cohort |

2785 (320≥65 years of age and 2465 between 16 to 65 years of age) |

Severe blunt trauma patients (trauma team activation) |

NEXUS |

CT |

C-spine fracture |

Non-elderly: 84.2 |

Non-elderly: 42.6

|

Non-elderly: 10.6 |

Non-elderly: 97.1 |

Only patients with completed data collection form were included. |

|

Elderly: 65.9 |

Elderly: 59.5 |

Elderly: 19.3 |

Elderly: 92.2 |

||||||||

|

Griffith, 2011 (NICE, 2016) |

Retrospective cohort |

1589 (age>18 years) |

Patients with C-spine CT examinations, documented trauma (level 1 trauma centrum) |

NEXUS |

CT or medical records |

Cervical spine injury (fracture, dislocation or subluxation) |

90.2 |

24 |

3 |

99 |

30 patients had multiple scans, these patients were counted at least double |

|

Hoffman, 1992 (NICE 2016) |

Prospective cohort |

974 (adults and children) |

Blunt trauma patients |

Pilot NEXUS (midline neck tenderness, altered level of alertness, severely painful injury, intoxication, midline neck pain) |

Radiography and possibly CT |

Fractures |

100 (87 to 100) |

12.5 (10.4-14.7) |

NR |

100 (96.9-100) |

Derivation study N=26 excluded because of incomplete data |

|

Hoffman, 2000 (NICE 2016) |

Prospective validation cohort |

31004 (adults ≥18 years only) |

Blunt trauma patients |

NEXUS |

Plain film radiography, possibly CT and/or MRI |

Fractures and cord injuries (clinical significant) |

99

|

12 |

2.8 |

99.7 |

These results could not be found in the original article, but were copied from NICE, 2016 |

|

Touger, 2002 (NICE, 2016) |

Prospective validation cohort |

2943 (age≥65 years) |

Blunt trauma patients |

NEXUS |

Plain film radiography, possibly CT and/or MRI |

Fractures and cord injuries (clinical significant) |

100 (97.1 to 100) |

14.7 (14.6-14.7)

or 14.1 according NCGC |

4.94 (4.94-5.0)

or 0.32 according NCGC |

100 (99.1-100) |

Subgroup of Hoffman, 2000. 2x2 table calculated by NCGC resulted in a PPV of 0.32%. |

|

Duanne, 2011 a (NICE, 2016) |

Prospective cohort |

2606 (age>16 years) |

Blunt trauma patients (trauma team activation). |

NEXUS |

Complete C-spine CT

|

Fractures |

82.8 |

45.7 |

8.9 |

97.6 |

Glasgow coma scale: 13.7 (4.5) for patients with fractures and 14.4 (3.6) in patients without fractures. In the NICE guideline, the CCR was reported as the index test, however, this seems to be incorrect. |

|

Rose, 2012 |

Prospective cohort |

761 (age>13 years) |

Awake and alert blunt trauma patients. (trauma team activation) |

Adapted NEXUS

(intoxication and distracting injury not included in tool). Furthermore, flexion/extension and rotation included. |

CT scanning of entire spine |

Cervical spine injury |

98.8 |

68.6 |

28.6 |

99.8% |

GCS: ≥14. Blood ethanol levels and urine drug screens outcomes were not included in index test. Diagnostic accuracy calculated using data presented in the article |

|

CCR |

|||||||||||

|

Duanne, 2011 b |

Prospective cohort |

3201 (age>16 years) |

Blunt trauma patients (Trauma team activation) |

CCR |

Complete C-spine CT |

Fractures |

100 |

0.6 |

6.03 |

100 |

Recruitment period was a little longer then in Duanne, 2011a, but patient population will overlap. This study was not included in the NICE guideline. |

|

Both |

|||||||||||

|

Duanne, 2013 (NICE, 2016) |

Prospective cohort Also included a deviation study |

5182 (age>16 years) |

Blunt trauma patients (trauma team activation) |

NEXUS CCR (Active rotation of the neck was excluded) |

Complete C-spine CT |

Fractures |

NEXUS: 81.2

|

NEXUS: 45.8

|

NEXUS: 9.1 |

NEXUS: 97.3 |

GCS<14 Data will likely partly overlap with Duanne, 2011 a and b. |

|

CCR: 100 |

CCR: 1 |

CCR: 6 |

CCR: 100 |

||||||||

|

Benayoun, 2017 |

Retrospective cohort |

N=760 (age≥16 years) |

Patients with history of ground level fall (<3ft or 5 stairs) |

NEXUS CCR |

CT-scans |

c-spine fractures |

NEXUS: 100 |

NEXUS: 24 (21.9;31.6) |

NEXUS: 1.3 (1.2;1.3) |

NEXUS: 100 |

Study evaluated the utility of CT-imaging, not specifically the diagnostic accuracy of these two tools. Insufficient documentation in 9.3% for NEXUS and 29.8% for CCR. |

|

CCR: 100 |

CCR: 29.8 (20.8;51.0) |

CCR: 1.9 (1.2;1.9) |

CCR: 100 |

||||||||

|

Griffith, 2013 (NICE 2016) |

Prospective cohort |

507 (age≥18 years) |

Blunt trauma patients (level 1 trauma center) |

NEXUS Abbreviated CCR (>65 years old, dangerous mechanism, paraesthesia in extremities, inability to rotate neck) |

CT |

Cervical spine injury (fracture, dislocation, subluxation) |

NEXUS: 100 |

NEXUS: 16 |

-

|

-

|

884 patients were excluded because of incomplete surveys |

|

CCR: 100 |

CCR: 29 |

|

|

||||||||

|

Combi: 100 |

Combi: 8 |

Combi: 1 |

Combi: 100 |

||||||||

Sensitivity

The reported sensitivity of the NEXUS criteria ranged from 65.9 (Goode, 2014) to 100% (Touger, 2002; Benayoun, 2017 and Griffith, 2013). The heterogeneity in the included patient populations might have influenced the results, with a lower sensitivity for patients meeting the criteria for trauma team activation (range: 65.9% in the elderly to 84.2 in nonelderly, Goode, 2014). Inconclusive results for the elderly have been reported (65.9% in the elderly meeting the criteria for trauma team activation, and 88.9 and 100% in the studies of Denver (2015) and Touger (2002), respectively).

Two studies (Rose, 2012; Dahlquist, 2015) focused on distraction injury, either only femur fractures (Dahlquist, 2015) or head injuries, torso injuries and/or long bone injuries (Rose, 2012). The sensitivity in these studies was relatively high (Dahlquist, 2015: 96.2%, Rose, 2012: 98.9%).

The reported sensitivity of the CCR was 100% (Benayoun, 2017; Duane, 2011; Duane, 2013; Griffith, 2013). Interesting is the difference found between the sensitivity for the NEXUS criteria and the CCR in the studies of Duane (2011a, 2011b and 2013), but it should be noted that the high sensitivity of the CCR also results in a very low specificity.

Specificity

The reported specificity of the NEXUS criteria ranged from 12% in the study of Hofmann (2002) to 63% in the retrospective cohort study of Dahlquist (2015). The reported specificity of the CCR ranged from 1-29%.

Figure 2 Sensitivity and specificity of the NEXUS criteria

Note that the patients included in Duane (2011a) were likely also included in Duane (2013). The study population described by Touger (2002) was a subsample of Hoffman (2000)

Figure 3 Sensitivity and specificity of the CCR criteria

Note that the patients included in Duane (2011a) were likely also included in Duane (2013)

PPV

See table 1.

NPV

See table 1.

Level of evidence – NEXUS-criteria

The level of evidence for the outcome measure diagnostic accuracy was downgraded by three levels due to the high risk of bias in the majority of studies (possible bias in patient selection, as in most studies only patients that underwent imaging were included), the inconsistence in results (which were probably also due to the variability in outcome measures and populations studied), and the imprecision (the wide confidence intervals, overlapping the boarder of clinical relevance).

Level of evidence - CCR

The level of evidence for the outcome measure diagnostic accuracy was downgraded by two levels due to the high risk of bias in the majority of studies (possible bias in patient selection) and the inconsistence in the results for specificity (which were probably also due to the variability in outcome measures and populations studied).

PICO 2: Thoracolumbar spine (TL-spine) injury

Description of included studies

Inaba (2015) performed a derivation study and developed a clinical decision rule for the thoracolumbar spine. Prospectively collected data of 3065 alert and eligible blunt trauma patients were included in the analyses. The endpoints were a TL-spine fracture requiring an orthoses or surgical stabilization. The reference test was a CT in the majority of the patients (93.3%), and plain films (6.3%) or MRI (0.2%) in the remaining patients. Possible components of the decision rule included clinical examination (positive in case of pain, midline tenderness to palpation, bony deformities and/or neurological deficits), injury mechanism (high risk mechanisms included falls, crush, motor vehicle collision with rollover and/or ejection, unenclosed vehicle crash and automobile versus pedestrian) and age (cut-off point: 60 years). Inaba (2015) reported that of the 3065 patients, 264 were diagnosed with a clinically significant TL-spine injury (29.2% required surgery).

Results

Sensitivity

Inaba (2015) reported a sensitivity of the physical examination of 78.4% for all clinical significant injuries. Adding the factor age ≥ 60 years and a high-risk mechanism to the rule resulted in a sensitivity of 98.8%. The specificity of this tool to predict injuries requiring surgery was 100%.

Specificity

Inaba (2015) reported a specificity of the physical examination of 72.9% for all clinical significant injuries. Adding the factor age ≥60 years and a high-risk mechanism to the decision rule resulted in a sensitivity of 29.0%. The later decision rule resulted in a specificity 27.3% for all injuries requiring surgery.

Positive predictive value

Inaba (2015) reported that when the decision rule included the factors physical examination, age and the risk mechanism, this results in a PPV of 11.6% for all clinical significant injuries. The PPV for injuries requiring surgery was 3.4%.

Negative predictive value

Inaba (2015) reported that inclusion of the factors physical examination, age and the risk mechanism resulted in a NPV for all clinical significant injuries of 99.6% and of 100% for injuries requiring surgery.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence for the outcome measure diagnostic accuracy was downgraded by three levels due to the high risk of bias (possible bias in patient selection) and the inclusion of a derivation study with a limited number of cases (imprecision, downgraded with two levels).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the diagnostic accuracy of the Canadian C-Spine Rule, the National emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS), Australian SPINEX card, the REMSSAP or a tool relevant to the thoracic or lumbosacral spine in adults (≥16 years or older) experiencing a traumatic incident?

PICO 1: Cervical spine injury

P: adults (≥ 16 years of age) experiencing a traumatic incident;

I: one of the following: Canadian C-Spine Rule (CCR), National emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS)-criteria, Australian SPINEX card or REMSSAP;

C: no test or one of the other test described above;

R: findings from imaging (X-ray, CT, MRI);

O: diagnostic accuracy.

PICO 2: Thoracolumbar injury

P: adults (≥16 years of age) experiencing a traumatic incident;

I: any tool relevant to the thoracic or lumbosacral spine;

C: no test or another test;

R: findings from imaging (X-ray, CT, MRI);

O: diagnostic accuracy.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered sensitivity a critical outcome measure for the decision-making, and the other diagnostic accuracy measures as important outcome measures for the decision-making.

The working group considered 90% as the lower limit of adequate sensitivity and strived toward a maximal specificity.

Search and select (method)

In February 2016 The National Clinical Guideline Centre published the NICE guideline ‘Spinal injury: assessment and initial management’ (NICE Guideline NG41; National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2016). One of the chapters in this guideline focusses on the diagnostic accuracy of the spinal injury assessment risk tools, and includes a review question that was similar to ours. Therefore, we decided to update the search presented in the NICE guideline, although some minor adaptations to the search strategy were made. The databases Medline (OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched for publications published between March 2015 to January 2017.

During the development of this guideline, we noticed that we had missed some possible relevant articles. After reviewing the search strategy, we noticed that we didn’t include search terms for tools relevant to the thoracic or lumbosacral spine. In August 2017 Medline (OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with an additional search strategy for articles published between 1990 and August 2017. Both search strategies are shown under the tab Methods.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews of diagnostic studies or a diagnostic study.

- Inclusion of adults (at least 85% of the sample had to be ≥ 16 years of age) who experienced a traumatic incident.

- Description of the findings from imaging.

- Report of de diagnostic accuracy (reporting at least the sensitivity and the specificity) of a tool to predict the presence of spinal injury. If a tool resembled the NEXUS or CCR, the study was included.

Studies that (partly) included follow-up by telephone as reference test or did not describe the method used for clinical clearance of the patients were excluded.

Of the 13 studies included in the NICE guideline, six studies (one of these studies was described in two publications) could be included in our systematic literature analysis. The two additional search strategies resulted in 61 and 264 hits, respectively. Based on the titles and abstracts, 53 studies were selected for further screening. After examination of the full text articles, a total of 46 studies were excluded. One additional study was identified after reading the full text articles includedin the NICE guideline. Finally, 14 studies (six of the studies included in the NICE guideline, seven resulting from the literature study, and one additional study) were included in the literature summary.

Fourteen studies were included in the literature analysis. Most studies focused on suspected cervical spine (C-spine) injury. Only one study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of a tool that focusses on suspected injury of the thoracolumbar spine, this study is described in the second part of this systematic literature analysis.

The most important study characteristics and results were included in the evidence tables. The assessment of the individual study quality (risk of bias) is included in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Ambulancezorg Nederland. (2016). Landelijke Protocol Ambulancezorg, versie 8.1. Zwolle.

- Benayoun MD, Allen JW, Lovasik BP, Uriell ML, Spandorfer RM, Holder CA. Utility of computed tomographic imaging of the cervical spine in trauma evaluation of ground-level fall. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016 Aug;81(2):339-44. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001073. PubMed PMID: 27454805.

- Dahlquist RT, Fischer PE, Desai H, Rogers A, Christmas AB, Gibbs MA, Sing RF. Femur fractures should not be considered distracting injuries for cervical spine assessment. Am J Emerg Med. 2015 Dec;33(12):1750-4. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.009. Epub 2015 Aug 10. PubMed PMID: 26346048.

- Denver D, Shetty A, Unwin D. Falls and Implementation of NEXUS in the Elderly (The FINE Study). J Emerg Med. 2015 Sep;49(3):294-300. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.03.005. Epub 2015 May 26. PubMed PMID: 26022935.

- Duane TM, Wilson SP, Mayglothling J, Wolfe LG, Aboutanos MB, Whelan JF, Malhotra AK, Ivatury RR. Canadian Cervical Spine rule compared with computed tomography: a prospective analysis. J Trauma. 2011 Aug;71(2):352-5; discussion 355-7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318220a98c. PubMed PMID: 21825938.

- Goode T, Young A, Wilson SP, Katzen J, Wolfe LG, Duane TM. Evaluation of cervical spine fracture in the elderly: can we trust our physical examination? Am Surg. 2014 Feb;80(2):182-4. PubMed PMID: 24480220.

- Haut ER, Kalish BT, Efron DT, Haider AH, Stevens KA, Kieninger AN, Cornwell EE 3rd, Chang DC. Spine immobilization in penetrating trauma: more harm than good? J Trauma. 2010 Jan;68(1):115-20; discussion 120-1. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181c9ee58. PubMed PMID: 20065766.

- Inaba K, Nosanov L, Menaker J, Bosarge P, Williams L, Turay D, Cachecho R, de Moya M, Bukur M, Carl J, Kobayashi L, Kaminski S, Beekley A, Gomez M, Skiada D; AAST TL-Spine Multicenter Study Group. Prospective derivation of a clinical decision rule for thoracolumbar spine evaluation after blunt trauma: An American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Multi-Institutional Trials Group Study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Mar;78(3):459-65; discussion 465-7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000560. PubMed PMID: 25710414.

- Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging. (2009). Richtlijn Acute traumatisch wervelletsels. ’s-Hertogenbosch: NOV.

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie. (2010). Richtlijn Licht traumatisch hoofd/hersenletsel. Utrecht: NVN.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. (2016) NICE guideline NG41: Spinal injury: assessment and initial management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- Nijendijk JH, Post MW, van Asbeck FW. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injuries in The Netherlands in 2010. Spinal Cord. 2014;52(4):258-63. doi:10.1038/sc.2013.180. Epub 2014 Jan 21. PubMed PMID: 24445971.

- Rose MK, Rosal LM, Gonzalez RP, Rostas JW, Baker JA, Simmons JD, Frotan MA, Brevard SB. Clinical clearance of the cervical spine in patients with distracting injuries: It is time to dispel the myth. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Aug;73(2):498-502. PubMed PMID: 23019677.

- Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001 Oct 17;286(15):1841-8. PubMed PMID: 11597285.

- Sundstrøm T, Asbjørnsen H, Habiba S, et al. Prehospital Use of Cervical Collars in Trauma Patients: A Critical Review. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2014;31(6):531-540. doi:10.1089/neu.2013.3094.

- Velopulos CG, Shihab HM, Lottenberg L, Feinman M, Raja A, Salomone J, Haut ER. Prehospital spine immobilization/spinal motion restriction in penetrating trauma: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018 May;84(5):736-744. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001764. PubMed PMID: 29283970.

- White CC 4th, Domeier RM, Millin MG; Standards and Clinical PracticeCommittee, National Association of EMS Physicians. EMS spinal precautions and the use of the long backboard - resource document to the position statement of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(2):306-14. doi:10.3109/10903127.2014.884197. Epub 2014 Feb 21. PubMed PMID: 24559236.

Evidence tabellen

Risk of bias assessment diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS II, 2011)

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Benayoun, 2017 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No: Only patients undergoing CT were included. Imaging and choice of imaging modality was performed at the discretion of the care providers.

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear. “all radiologic scans were independently reviewed by board-certified emergency radiologists or neuroradiologists…”. “All fractures identified during chart review were secondarily and independently reviewed by two additional neuroradiologists”. First assessment is without further knowledge, unknown for second assessment. |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NA

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? No, in 10 (NEXUS) to 30% (CCR) of the patients there was insufficient documentation of indications of imaging.

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No, although only a specific aetiology of trauma is evaluated

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

|

|

|

Inaba, 2015 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear, convenience sample

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? NO, patients that did not undergo diagnostic imaging were excluded (only 3065 of the 3863 otherwise eligible patients included).

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes. “All images obtained were interpreted by an attending radiologist who was blinded to the study case report form contents”

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NR

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No, over 6% underwent plain films and 0.2% MRI.

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No |

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Denver |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No, n=30 excluded due to incomplete data or imaging or due to exclusion criteria. Furthermore, a high number of eligible patients was missed (46 patients did not undergo CT of the spine and 22 patients had no completed data form).

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Likely, datasheet on which the patients were categorized as NEXUS positive of NEXUS negative was filled out after the decision to conduct a CT had been made.

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? unclear, not reported

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NR

Did all patients receive a reference standard? YES

Did patients receive the same reference standard? YES

Were all patients included in the analysis? Unclear patient selection

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Goode, 2014 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Unclear, only patients with a completed data collection form were included, it is unclear how many patients were excluded based on this criterium

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear, no information available

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? YES

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear, no information available

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NA

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Unclear, see patient selection |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No |

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

|

Tougher, 2002 Hoffman, 2000 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No, the study only included only patients that underwent imaging: “The ultimate decision whether to order radiography was made at the discretion of the treating physician, according to the criteria he or she ordinarily used, and was not determined in any way by participating in the study.” |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes: “the results of all the evaluation were recorded on data forms before imaging of the cervical spine”.

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? No, imaging included plain-film imaging in most cases

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes: “Neither the formal interpretation by the radiologists nor the classification of injuries was done with knowledge of findings recorded on study data forms.” |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NR

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Unclear, CT or MRI could be performed when film radiography was impractical or impossible Hoffman, (2000)

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: High |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Griffith, 2011 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No, only patients with spine CT examination were included.

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear, it is only mentioned that “An additional limitation, also related to the retrospective nature of the study, was the potential for reviewer bias because of the nonblinded review of medical records”

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes, but determination of distracting injury might have been difficult (based primarily by injuries that were radiographically apparent)

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear, it is only mentioned that “An additional limitation, also related to the retrospective nature of the study, was the potential for reviewer bias because of the nonblinded review of medical records”

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Not applicable

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes, but some patients were included multiple times |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No, although there is a risk that the medical recordings were not always complete due to the retrospective design.

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

|

|

Griffith, 2013 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No: the study only included only patients that underwent imaging.

884 (63%) patients were excluded because their surveys were not completed. A subset was retrospectively reviewed, and no statistically significant difference were found. |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NA

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR. |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

Duane, 2013, Duane, 2011b Duane, 2011a |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Unclear, of the 7904 patients, only of 5182 (66%) patients the data form was completed, and only these patients were included in the analyses Duane, (2013)

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes, the authors mention “a research nurse collected all of the forms within 24 hours of the patients’ admission and completed them by adding missing data points, followed by final CT results to avoid any introduction of bias.” Duane, (2013)

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? NA |

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NR

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: Unclear |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

Rose, 2012 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes, all CT-scans were made after the clinical examination had been performed. Yes: “Data with regard to demographics and clinical examination were prospectively collected and documented in a data study form prior to performance of indicated radiographic evaluation.”

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear, no information provided

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NR

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No, although it resembles a subpopulation

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? Not specifically NEXUS/CCR

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

Test different than classic NEXUS. Subpopulation |

|

Hoffman, 1992 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No, only patient for who radiography was ordered were included. In the discussion the authors note that physicians tended to enrol those patients with a higher likelihood of fracture.

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Unclear: “we stressed that physicians complete these forms before knowing results of cervical-spine radiography.” However, in the discussion the authors noted: “Bias in the sensitivity estimate could have occurred through misclassification of patients regarding their fracture status or by physicians changing their answers on the data forms once they were aware that the patients had a fracture.”

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? NA |

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? No, radiography

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Probably.

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NA

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes, although some might have received also CT.

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? no

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? no

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No |

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

|

Dahlquist, 2015 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? No, only patients with complete documented examinations before imaging were included. Furthermore, patients had to be evaluated for C-spine injury with imaging.

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Unclear

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? NR

Did all patients receive a reference standard? Yes

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No, a small number of paediatric patients received plain films or MRI.

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No, although quite specific.

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: HIGH |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: Unclear |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

|

Evidence table for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Prevalence and complete data |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

NICE guideline, 2016

|

SR (and meta-analysis)

Literature search up to 27-03-2015 A: Duane, 2011 B: Duane, 2013 C: Griffith, 2011 D: Griffith, 2013 E: Hoffman, 1992 F: Hoffman, 2000 G: Touger, 2002

Study design: cohort, observational (prospective / retrospective) A: Prospective study B: Prospective and deviation study C: Retrospective validation D: Prospective validation E: Prospective, deviation F: Prospective, validation G: Prospective, validation

Setting and Country: A: Level 1 trauma centre, USA B: Level 1 trauma centre, USA C: Emergency department of level 1 trauma centre, USA D: Level 1 trauma centre, USA E: UCLA emergency medicine centre, USA F: 21 centres, USA G: 21 centres, USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: None reported B: No interest or conflict of interest C: Not reported D: None reported E: Not reported F: Non-commercial G: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria SR: PICO:

P: Children, young people and adults with suspected traumatic spinal injury I: Canadian C-Spine Rules (CCR), National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS), Australian SPINEX card, American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA), REMSSAP, Any tools relevant to the thoracic or lumbosacral spine. C: later imaging findings, later surgical findings, later clinical findings, autopsy O: sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, likelihood ratios

Other inclusion criteria: English only, cohort studies

Exclusion criteria SR: People with spinal cord or column injury directly caused by a disease process without a traumatic event.

The nice guideline included 12 studies. Here the 6 studies that included children or used telephone follow-up were excluded. Six studies were included in this table.

Important patient characteristics:

N, % male A: 2606, not reported B: 5182, fracture: 67%, no fracture: 63% C: 1552, of which 30 had multiple scans, 59% D: 507, 60.9% E: 947, 59.3% F: 31004 (adults included), 58.7% (complete group) G: 2943, 47%

Mean or median age A: fracture: 43.4 years, no fracture: 37.7 years B: fracture: 43.9 No fracture: 38.4 years C: 43.4 years D: 44 years E: 25 years F: 37 years (complete group) G: Not reported, >65 years to be included

|

A: NEXUS criteria (wrongly stated CCR in NICE guideline)

B-1: NEXUS B-2: CCR (no active neck rotation)

C-1: NEXUS criteria

D-1: Nexus criteria D-2: Abbreviated Canadian C-Spine (>65 years old, dangerous mechanism, paraesthesia in extremities, inability to rotate neck)

E: Pilot NEXUS with factors: 1. Midline neck tenderness; 2. Altered level of alertness; 3. Severely painful injury; 4. Intoxication; 5 midline neck pain

F: NEXUS criteria

G: NEXUS criteria

|

A: complete C-spine CT

B: complete C-spine CT

C: CT-findings

D: CT

E: Radiography and possibly CT

F: plain film radiography and possibly CT and/or MRI

G: plain film radiography and possibly CT and/or MRI

|

Prevalence A: TP: 130, FP: 1331, FN: 27, TN: 1118 B-1: TP:263, FP: 2633, FN:61, TN: 2225 B-2: TP: 324, FP: 4828, FN: 0, TN:30 C: TP: 37, FP: 1180, FN: 4, TN: 368 D-1: TP:5, FP: 421, TN: 81, FN: 0 D-2: TP: 4, FP: 293, TN: 119, FN:0 E: NR. There were 27 fractures and 947 no fractures. F: TP: 780, FP: 26518, FN: 8, TN: 3698 G: TP: 135, FP: 2395, FN: 2, TN: 411

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Reasons: N (%) A: NR B:NR (but compliance rate was only 66%) C: 0 D: 884 did not have surveys completed, not included in patient sample. E: n=26 had incomplete forms, not included in total sample. It was estimated that 1342 cervical spine studies were performed during study period. F: NR G: NR

|

Sensitivity A: 82.8% B-1: 81.2% B-2: 100% C: 90.2% D-1: 100% D-2: 100% E: 100% (87 to 100) F: 99% G: 98.5%

Specificity A: 45.7% B-1: 45.8% B-2: 0.6% C: 24% D-1: 16% D-2: 29% E: 12.5% (10.4 to 14.7) F: 12% G: 14.6%

Positive predicting value A: 8.9% B-1: 9.1% B-2: 6.3% C: 3% D-1: NR D-2: NR E: NR F: 2.8% G: 5.3%

Negative predicting value A: 97.6% B-1: 97.3% B-2: 100% C: 99% D-1: NR D-2:NR E: 100% (96.9-100) F: 99.7% G: 99.5%

likelihood ratios Not reported

|

Study quality (ROB): QUADAS-2 criteria were used. Quality of the evidence assessed using GRADE.

Place of the index test in the clinical pathway: A: Addition (all patients had a CT) B: Addition (all patients had a CT) C: retrospective analysis (of CT examinations) D: addition (all patients had a cervical CT following blunt trauma) E: addition (all patients underwent radiography of the cervical spine following blunt trauma). No attempt to modify the physician use of cervical spine radiography. F: Addition, clinicians were cautioned against using the set of criteria as the sole determinant of whether imaging was needed. G: Addition, clinicians were cautioned against using the set of criteria as the sole determinant of whether imaging was needed

Choice of cut-off point: A: Fractures B: Fractures C: CSI (fracture, dislocation or subluxation), not further specified D: CSI (fracture, dislocation or subluxation), not further specified E: Fractures F: Fractures and cord injuries G: Fractures and cord injuries

Facultative: Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

A: Patients likely also included in B. B: The additionally performed univariate analyses identified 7 predictors of cervical spinal cord injury (tender to palpation midline, GCS<15, age≥65, paraesthesia’s, rollover motor vehicle collision, patient ejection, never in sitting position in ED). These factors resulted in a sensitivity of 99.0%, specificity of 11.5%, PPV of 6.95% and NPV of 99.47%. C: Descriptive are presented for 1552 patients, but the results are based on 1589 examination records. Some patients are counted more than once. Study designed to investigate if implementing NEXUS would lead to reduction in CT scans. D: Intermediate findings were added to the negative group; none progressed. Study aimed to investigated whether using NEXUS would lead to less unnecessary CT-scans. G: Patients were also included in D

|

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

Exclusion after reading the full article.

|

Author, year |

Reason |

|

Anderson, 2010 |

Review, also included studies with telephone call as follow-up. Did not present enough data of individual studies and did not perform a quality assessment. |

|

Armstrong, 2007 |

Not all patients underwent imaging (no imaging in patients with c-spine clearance) |

|

Boland, 2014 |

Did not focus on immobilisation |

|

Boustani, 2015 |

Abstract |

|

Braude, 2002 |

Was not available |

|

Brown, 1998 |

Did not evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of a tool |

|

Burton, 2006 |

Not clear whether all patients underwent imaging |

|

Burton, 2005 |

Not clear whether all patients underwent imaging |

|

Charters, 2004 |

Review, not systematic |

|

Clark, 2001 |

Review, not systematic, adolescents |

|

Como, 2009 |

Guideline, review performed, but not enough information of the individual studies presented. Focus on imaging |

|

Domeier, 2005 |

Not clear whether all patients received imaging |

|

Domeier, 2002 |

Not all patients underwent imaging |

|

Domeier, 1999 |

It is likely that not all patients underwent imaging |

|

Duane, 2016

|

Study included only patients meeting the criteria for trauma team alert and defined a cervical spine clearance algorithm. The results of the CT were included in the algorithm, while this question focussed on the patients before diagnostic imaging had been performed |

|

Gonzalez, 2013 |

Was not available |

|

Gonzales, 2009 |

Imaging was not performed in all patients |

|

Hong, 2014 |

In this study it was evaluated how many patients require C-spine immobilization based on three protocols. Furthermore, it was evaluated how many C-spine injuries were missed if the protocols had been followed with 100% compliance (only sensitivity). Not all patients underwent imaging |

|

Hong, 2012 |

Abstract |

|

Inaba, 2016 |

Evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of the CT-scan of the C-spine in blunt trauma patients |

|

Jin, 2007 |

All patients were diagnosed with spinal fractures with or without spinal damage |

|

Kanwar, 2015 |

Not available |

|

Kerr, 2005 |

Did not evaluate the validity of the prediction rule |

|

Klein, 2016 |

Did not focus on the diagnostic value of a tool |

|

Lukins, 2015 |

Review, focuses mainly on imaging |

|

Mahler, 2009 |

Abstract |

|

McCutcheon, 2015 |

Review, limited search, no risk of bias assessment or GRADE evaluation. Provides only a limited amount of information about the included studies |

|

McCaul, 2013 |

Abstract |

|

McDonald, 2016 |

Systematic review, but slightly different research question. Studies that enrolled patients in the prehospital setting who were assessed for spine injury according to predefined clinical criteria and either immobilized or not were included |

|

Meldon, 1998 |

Focus on agreement between emergency medical technicians and emergency physicians. Not all patients underwent imaging |

|

Moscati, 2007 |

Only patients that were deemed at risk for injury underwent radiography |

|

Myers, 2009 |

Not every patient underwent imaging |

|

Muhr, 1999 |

Not clear whether all patients did undergo imaging. |

|

Paterek, 2015 |

Study evaluates the number of patients that were not immobilized by the emergency medical services, while they met the criteria for immobilization based on the protocols (mirrors NEXUS criteria). Did not study the diagnostic accuracy of the NEXUS tool itself |

|

Paykin. 2016 |

Abstract |

|

Pitt, 2006 |

Not all patients underwent imaging |

|

Saltzherr, 2009 |

Review, not systematic |

|

Sebastian, 2001 |

No imaging, different tool for c-spine |

|

Sochor, 2013 |

Different tool for c-spine injury |

|

Stroh, 2001 |

All patients had trauma, only specificity could be calculated. Evaluates different kind of tool |

|

Stein, 2012 |

Review, not systematic |

|

Tatum, 2017 |

Different tool for c-spine injury |

|

Tran, 2016 |

Validate a modified NEXUS criteria in a low-risk elderly fall population, but telephone follow-up in 34% and 24% was admitted after the trauma and observed |

|

Uriell, 2017 |

Did not identify any spine fracture in their retrospective reviewed cohort of patients with a history of assault |

|

Vaillancourt, 2009 |

Included follow-up by telephone as reference test |

|

Werman, 2008 |

Not clear whether imaging had been performed in all patients |

|

Zakrison, 2016 |

Review, not systematic |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 15-11-2019

Laatst geautoriseerd : 15-11-2019

Geplande herbeoordeling :

|

Module |

Regiehouder(s) |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling |

|

Welke patiënten zijn verdacht voor acute traumatisch werveletsel? |

NOV |

2019 |

2024 |

Elke 5 jaar |

NOV |

- |

Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

In samenwerking met:

Ambulancezorg Nederland

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Doel van deze herziening is om weer een richtlijn te verkrijgen waarin de meeste recente medische kennis en inzichten omtrent de zorg voor patiënten met acute traumatische wervelletsels is meegenomen.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is bedoeld voor alle professionele hulpverleners in Nederland die betrokken zijn bij opvang, diagnostiek en behandeling van patiënten met (een verdenking op) een traumatisch letsel aan de wervelkolom met of zonder begeleidend neurologisch letsel. Dit betreft in eerste instantie ambulancezorgverleners, het Mobiel Medisch Team (MMT), spoedeisende hulp verpleegkundigen en -artsen, radiologen, orthopeden, neurologen, neurochirurgen, traumachirurgen, intensivisten, klinisch geriaters en revalidatieartsen.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2016 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten verdacht op het hebben van een acuut traumatisch wervelletsel, of bij de zorg voor patiënten waarbij een acuut traumatisch wervelletsel is vastgesteld. De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. F.C. Öner, orthopedisch chirurg, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, Utrecht, Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging (voorzitter)

- Prof. dr. F.W. Bloemers, traumachirurg, AmsterdamUMC, locatie VUmc, Amsterdam, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde

- Dhr. G. Brouwer, teammanager SEH, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Spoedeisende Hulp Verpleegkundigen

- Drs. G.J.A. Jacobs, spoedeisende hulp arts, Dijklander ziekenhuis, Hoorn en Purmerend, Nederlandse Vereniging van Spoedeisende Hulp Artsen

- Drs. J.M.R. Meijer, Intensivist, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep, Alkmaar, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care

- Dr. D.F.M. Pakvis, orthopedisch chirurg, OCON Orthopedische kliniek, Hengelo, Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging

- Drs. F. Penninx, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Dwarslaesie Organisatie Nederland

- Mevr. M. van Dam, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Dwarslaesie Organisatie Nederland

- Dr. S.D. Roosendaal, radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie

- Dr. H. van Santbrink, neurochirurg, Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum+, Maastricht, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurochirurgie (tot maart 2018)

- Drs. T.A.R. Sluis, Revalidatiearts, Rijndam Revalidatiecentrum, Rotterdam, Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen

- Drs. R. de Vos, anesthesioloog/Medisch Manager Ambulancezorg, Ambulancezorg Nederland

- Dr. P.E. Vos, Neuroloog, Slingerland Ziekenhuis, Doetinchem, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- Drs. P.V. ter Wengel, neurochirurg, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden, Haaglanden Medisch Centrum locaties Den Haag en Leidschendam, en Spaarne Gasthuis locaties Hoofddorp en Haarlem Zuid, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurochirurgie

Klankbordgroep

- Dhr. H.H. Wijnen, Klinisch Geriater, Rijnstate, Arnhem, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Geriatrie

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. S. Persoon, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M. Molag, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot oktober 2017)

- S. Wouters, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- M. Wessels, MSc, Medisch informatiespecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen