Agraves versus doorlopend sluiten van de huid bij sectio bij vrouwen met obesitas

Uitgangsvraag

Welke sluitingstechniek van de huid kan het beste worden gebruikt bij vrouwen met obesitas die een sectio ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Sluit bij een vrouw met obesitas bij een sectio bij voorkeur de huid met een intracutane doorlopende hechting.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De literatuuranalyse werd gebaseerd op de meta-analyse van Mackeen (2015) met 5 geïncludeerde studies en de individuele RCT van Zaki (2018). Mackeen (2015) heeft in een gestratificeerde analyse naar vrouwen met obesitas die een sectio ondergaan alleen de cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘wondcomplicaties’ meegenomen. De cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘wondinfecties’ en de andere belangrijke uitkomstmaten zijn dus alleen in de RCT van Zaki (2018) onderzocht.

Wondcomplicaties

Doorlopende intracutane sluiting van de huidincisie geeft waarschijnlijk een reductie van 35% (12-53%) op wondcomplicaties ten opzichte van agraves sluiting bij vrouwen met obesitas na een sectio (Mackeen 2015; Zaki. 2018). Bij een afgesproken minimale klinische relevantie van 25% (RR≤0.75), is het onduidelijk of deze reductie met een betrouwbaarheidsinterval van 12-53% ook klinisch relevant is. De overall bewijskracht voor de uitkomst ‘wondcomplicaties’ is ‘hoog’. In de geïncludeerde studies werd veelal de pfannenstiel incisie gedaan en geen mediane onderbuik-incisie.

Wondinfecties

Beide sluitingstechnieken geven mogelijk een vergelijkbaar aantal wondinfecties bij vrouwen met obesitas na sectio (Zaki, 2018). Door het zeer lage aantal opgetreden wondinfecties (slechts 5 in totaal, 3 en 2 in beide groepen) in deze RCT en de kleine onderzoekspopulatie (238 patiënten) is het onduidelijk of de verschillende hechtingsmethoden toch kunnen leiden tot een klinisch relevant effect. De overall bewijskracht voor de uitkomst wondinfecties is ‘laag’ door imprecisie (laag aantal geïncludeerde vrouwen en events).

Beide sluitingstechnieken geven mogelijk een vergelijkbaar aantal wonddehiscenties, voor diepe separatie is dit in het geheel niet beschrveven bij de doorlopende huidhechting en 3x bij de agraves bij vrouwen met obesitas na sectio. De bewijskracht was wederom ‘laag’ door de kleine onderzoekspopulatie en het lage aantal events. Wel zouden vrouwen significant vaker voor dezelfde sluitingstechniek kiezen bij sluiting van de huid met een intracutane doorlopende hechting dan bij agraves, mogelijk door het lagere aantal wondcomplicaties of omdat het operatielitteken aangenamer oogt dan bij agraves. De postoperatieve pijn en tevredenheid over het litteken waren vergelijkbaar. De bewijskracht voor patiënttevredenheid was ‘redelijk’ door de kleine onderzoekspopulatie. Tot slot zorgt een intracutane doorlopende hechting voor een toename van de operatieduur van ca. 10 minuten. De opnameduur in het ziekenhuis wordt niet beïnvloed wordt door de manier waarop de huid is gesloten. De bewijskracht voor ‘duur van de operatie’ en ‘opnameduur’ was ‘redelijk’ door de kleine onderzoekspopulatie.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten

Hoewel er geen verschil in tevredenheid werd gerapporteerd in de RCT van Zaki (2018) kiezen de vrouwen geïncludeerd in deze studie mogelijk bij een volgende sectio vaker voor intracutane doorlopende hechtingen in plaats van staples. De werkgroep achtte de beschreven vragenlijst niet representatief voor het meten van patiënt tevredenheid – bijvoorbeeld, werd de tevredenheid over wondgenezing na 7-14 dagen bevraagd, terwijl wondgenezing pas na 6-12 maanden voltooid is. De reden daarvoor wordt uit deze studie niet duidelijk.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In geen van de geïncludeerde RCT’s is een kosten-baten analyse opgenomen. Uit beide RCT’s blijkt de operatie tijd significant korter bij het gebruik van staples (dit is in de RCT van Mackeen niet apart geanalyseerd in de groep vrouwen met obesitas). Echter, in de gestratificeerde analyse van de groep vrouwen met obesitas in de RCT van Mackeen is het aantal wondcomplicaties lager bij gebruik van een intracutane doorlopende hechting. Dit zou de mogelijke kostenbesparing van een kortere OK tijd theoretisch weer teniet kunnen doen

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is geen uitspraak te doen over de aanvaardbaarheid of haalbaarheid van de aanbeveling onder patiënten of zorgverleners. Maar er zijn ook geen barrières te verwachten aangezien in Nederland intracutane doorlopend hechten de meest gangbare sluitingstechniek is bij de sectio.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bij vrouwen met obesitas is de incidentie van wondcomplicaties na sectio hoog. De techniek van sluiten van de huid zou een bijdrage kunnen leveren aan het voorkomen daarvan en daarom zijn de 2 meest gebruikte sluitingstechnieken vergeleken. Slechts een beperkt aantal studies kon worden geïncludeerd en in deze studies zijn niet alle door de werkgroep vastgestelde uitkomstmaten onderzocht.

Hoewel er slechts voor één uitkomstmaat - wondcomplicaties hoge bewijs is en voor de overige uitkomstmaten redelijke of lage bewijs, gaat de voorkeur van de werkgroep uit naar de intracutane doorlopende sluitingstechniek. Hiervoor is gekozen omdat er aanwijzingen zijn dat deze techniek wondcomplicaties vermindert (Mackeen, 2015) en er indirecte aanwijzingen zijn dat vrouwen meer tevreden zijn als de huid bij de sectio intracutaan is gesloten (Zaki, 2018). Dit is niet anders dan bij vrouwen zonder obesitas die een sectio ondergaan.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Vrouwen met obesitas hebben een verhoogd risico op wondcomplicaties na een sectio . Het is onduidelijk of het sluiten van de huid door middel van agraves het risico op complicaties verlaagt, of het genezingsproces verbetert en de of de tevredenheid van de patiënt beter is in vergelijking met doorlopend sluiten van de huid. In de huidige NVOG richtlijn Zwangerschap bij Obesitas 2009 is hierover nog geen aanbeveling gedaan.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

High GRADE |

The use of staples results in a higher risk of wound complications when compared with continuous sutures during wound closure in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section.

Sources: Mackeen, 2015; Zaki, 2018 |

|

Low GRADE |

The use of staples versus continuous sutures may not have an effect on wound infections during wound closure in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section.

Sources: Zaki, 2018 |

|

Low GRADE |

The use of staples versus continuous sutures may not have an effect on wound separation during wound closure in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section.

Sources: Zaki, 2018 |

|

Low GRADE |

Women with obesity with staples may be less satisfied about wound recovery than women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section with continuous sutures.

Sources: Zaki, 2018 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Use of staples probably results in a slight decrease in procedure time (minutes) compared to continuous sutures in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section.

Sources: Zaki, 2018 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Closure with staples probably results in no difference in the duration of the hospital stay (days) compared to closure with continuous sutures in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section.

Sources: Zaki, 2018 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of closure with staples on the outcome thrombosis when compared with closure with continuous sutures in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section.

Sources: - |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of closure with staples on the outcome readmission for operation when compared with closure with continuous sutures in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section.

Sources: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Mackeen (2015) is a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the difference between absorbable suture and metal staples on wound complications, pain perception, patient satisfaction and operating time. The review included all women who received a caesarean section, however not women with obesity in specific. The study included RCTs that compared absorbable suture with non-absorbable staples, excluding all other surgical closure techniques. The study investigated the primary outcome ‘wound complication’ stratified for obesity (BMI <30 kg/m2 nonobese vs. ≥30 kg/m2 obese). For this, the authors of the trials were contacted to obtain more details about the outcome wound complications stratified by body mass index (<30 kg/m2 [nonobese] vs. ≥30 kg/m2 [obese]). A total of 5 RCTs provided their wound complication results stratified for obesity, with a total of 627 women receiving sutures and 641 staples (Aabakke, 2013; Basha, 2010; Figueroa, 2013; Huppelschoten, 2013; Mackeen, 2014; Zaki, 2013). The postoperative follow up time to assess wound complications differed from 2-4 weeks to 12 weeks. Wound complications included the assessment of infections (all studies), wound separation (all studies), hematoma (Figueroa, 2013; Huppelschoten, 2013 and Mackeen, 2014), seroma (Figueroa, 2013; Mackeen, 2014) and readmission for wound complications (Basha, 2010) (Table 1). One study investigated suture versus staples by using each method on each lateral side of the incision (Aabakke, 2013). One study included both uterine and wound infections together in their wound infection rate (Basha, 2010).

Table 1. Wound complications reported in individual studies

|

Author, year |

Infection |

Wound complications |

Readmission for wound concern |

||

|

|

|

Separation |

Hematoma |

Seroma |

|

|

Aabakke, 2013 |

√ |

√ |

No |

No |

No |

|

Basha, 2010 |

√a |

√ |

No |

No |

√ |

|

Figueroa, 2013 |

√ |

√b |

√b |

√ |

No |

|

Huppelschoten, 2013 |

√ |

√ |

√ |

No |

No |

|

Mackeen, 2014 |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

Source: Mackeen (2015) “a Included uterine infections in definition of infection; b Hematoma and seroma numbers were not presented separately, but included as causes of skin separation”

Zaki (2018) is a RCT performed in the US comparing subcuticular suture with stainless steel staples for wound closure in women with class III obesity (BMI ≥40km/m2). The study randomized 121 women to suture and 121 to staples. All patients underwent a subcutaneous closure before receiving the subcuticular suture or staples. The mean BMI was 45.1 ≥± 4.4 kg/m2 in the staples group and 46.2 ± 5.5 kg/m2 in the suture group. The primary outcome was ‘wound complications’, defined as infection, superficial separation or deep separation (Table 2). Wound complications were assessed at hospital discharge and at 2 weeks postpartum. Besides wound complications, the study also assessed total operative time and patient satisfaction (overall and about wound appearance).

Table 2. Wound complications reported in an individual study

|

Author, year |

Infection |

Wound complications |

Readmission for wound concern |

||

|

|

|

Separation |

Hematoma |

Infection |

|

|

Zaki, 2018 |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

No |

Source: Zaki (2018)

Results

The results from the meta-analysis by Mackeen (2015) were only available for the critical outcome ‘1. wound complications’ stratified by obesity. The crucial outcome ‘2. wound infections’ and the other important outcomes were not separately assessed for women with obesity by Mackeen (2015). Therefore, only the individual RCT by Zaki (2018) could be used.

Critical outcomes

1. Wound complications

Mackeen (2015) included 5 trials (1030 women) to compare absorbable suture with staples as a closure technique in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section. Obesity was defined by Mackeen (2015) as a BMI ≥30m2. The working group has added the trial of Zaki (238 women) to this comparison, which compared absorbable suture with stainless steel staples as closure techniques as well, to combine to a total of 6 trials (1268 women). Zaki, 2018 included only women with a body mass index ≥40kg/m2. The outcome ‘wound complications’ was defined by the individual trial authors as a composite of wound infection (all studies), separation (all studies), hematoma (Figueroa 2013, Huppelschoten 2013, Mackeen 2014 and Zaki 2018), seroma (Figueroa 2013, Mackeen 2014 and Zaki 2018) and readmission for wound complications (Basha 2010) (Table 1 and 2).

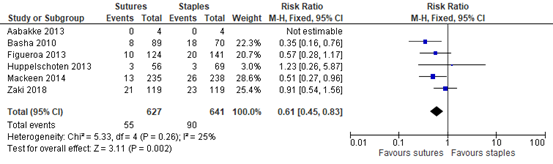

Overall, subcuticular suture reduced the risk of developing a wound complication with 39% compared to staples (6 trials, 1268 women, RR 0.61, 95%CI 0.45 to 0.83). This RR is statistically significant, and pertains a clinically relevant difference as the confidence interval does not exceed the limit of RR≤0.9.

Figure 1. Outcome wound complications, comparison sutures versus staples in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section

Source: Mackeen, 2015 & Zaki 2018 Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

2. Wound infections

Zaki (2018) assessed the outcome ‘wound infection’ in 238 women, comparing absorable sutures with stainless steel staples as a closure technique in women with obesity undergoing a cesarean section. The authors included only women with a body mass index ≥40kg/m2. Wound infections were defined as ‘those meeting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of surgical site infections and requiring antibiotic therapy’, and were assessed at hospital discharge and at two weeks postpartum.

At the postoperative wound inspection (7-14 days post partum) no significant difference in wound infection rate between sutures and staples was reported (Table 3) (Zaki 2018). The clinical relevance of the found effect is unclear, as the confidence interval is exceeding both the upper and lower limit of clinical relevance (RR≤0.75 and RR≥1.25), indicating (large) imprecizion.

Table 3. Wound infection reported in an individual study

|

|

Sutures (N=119) |

Staples (N=119) |

Risk Ratio, Fixed, 95%CI |

|

Wound infection |

2 (1.7%) |

3 (2.5%) |

0.67 (0.11 to 3.92) |

Source: Zaki (2018)

Important outcomes

3. Wound separation

Zaki (2018) assessed the outcome ‘wound separation’ in 238 women, comparing absorable sutures with stainless steel staples as a closure technique in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section. The authors included only women with a body mass index ≥40kg/m2. Wound separations were identified as either superficial (<0.5 cm deep and only involving the dermis layer) or deep (>0.5 cm in depth and requiring packing

or reclosure) resulting from hematoma or seroma (Zaki 2018).

At the postoperative wound inspection (7-14 days post partum) no significant difference in superficial or deep separation between sutures and staples was reported (Table 4) (Zaki 2018). The clinical relevance of the found effect is unclear, as the confidence interval is exceeding both the upper and lower limit of clinical relevance (RR≤0.75 and RR≥1.25), indicating (large) imprecizion.

Table 4. Wound separation reported in an individual study

|

|

Sutures (N=119) |

Staples (N=119) |

Risk Ratio, Fixed, 95%CI |

|

Superficial separation |

11 (9.2%) |

11 (9.2%) |

1.00 (0.45 to 2.22) |

|

Deep separation |

0 (0) |

3 (3.5%) |

0.14 (0.01 to 2.74) |

Source: Zaki (2018)

4. Patient satisfaction

Zaki (2018) assessed the outcome ‘patient satisfaction’ in 227 women, comparing absorable sutures with stainless steel staples as a closure technique in women with obesity undergoing a cesarean section. The authors included only women with a body mass index ≥40kg/m2. Patient satisfaction consisted of an survey assessment of pain (1=least, 10=most), wound appearance satisfaction (1=least, 10=most), concern about wound healing (1=least, 10=most), wound recovery satisfaction (‘would you have the same closure again’ percentage answering ‘yes’). The assessment was done at the 7-14 day wound follow up visit.

Table 5. Patient satisfaction reported in the individual studies

|

|

Sutures (N=114) |

Staples (N=113) |

Mann-Whitney U and ꭓ2 tests |

|

Pain level (1=least, 10=most) |

2 (1 to 3) |

2 (1 to 3) |

0.71 |

|

Wound appearance satisfaction (1=least, 10=most) |

10 (9 to 10) |

10 (9 to 10) |

0.99 |

|

Concern about wound healing (1=least, 10=most) |

1 (1 to 2) |

1 (1 to 2) |

0.22 |

|

% answering yes to the question ‘would you have the same closure again?’* |

108 (93.9) |

98 (83.1) |

0.01 |

Source: Zaki (2018). “Data were analyzed with Mann-Whitney U and c2 tests, where applicable. Data are presented as median [interquartile range] or n (%) unless otherwise noted. P value <.05 indicates significance.” *this question was not considered a relevant measure for patient satisfaction by the working group, since complete wound healing occurs after 6-12 months, the results are not representative for wound healing after 7-14 days.

In both groups women were similarly content with the pain level, wound appearance and concern about wound healing (Table 5). However, when women were asked if they would choose the same closure technique again, women with sutures choose significantly more often for the same closure again, which may indicate more wound recovery satisfaction (Table 5) (Zaki, 2018).

5. Duration of hospital stay (days)

Zaki (2018) assessed the outcome ‘duration of hospital stay (days)’ in 238 women, comparing absorable sutures with stainless steel staples as a closure technique in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section. The authors included only women with a body mass index ≥40kg/m2.

No difference between hospital stay was observed between groups, with an average stay of 5 days for both groups (4.9 days in both groups) (Independent samples T-test, p=1.00) (Zaki 2018).

6. Duration of operation / length of procedure (minutes)

Zaki (2018) assessed the outcome ‘length of procedure (minutes)’ in 238 women, comparing absorable sutures with stainless steel staples as a closure technique in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section. The authors included only women with a body mass index ≥40kg/m2.

The length of the procedure was in average 12 minutes longer in the sutures group (55.8±26.0 sutures total procedure, 43.2±21.9 staples total procedure), which was clinically significant (Independent samples T-test, p=0.001) (Zaki, 2018).

7. Thrombosis

None of the included studies reported on the outcome thrombosis.

8. Readmission for wound concern

None of the included studies reported on the outcome readmission for wound concern.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘1. wound complications’ was not further downgraded, so assessed a high GRADE.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘2. wound infections’ was downgraded by 2 levels to a low GRADE because of (large) imprecision (confidence interval exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance and upper limit of clinical relevance (RR≤0.75 and RR≥1.25).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘3. wound separation’ was downgraded by 2 levels to a low GRADE because of (large) imprecision (confidence interval exceeds both the lower limit of clinical relevance and upper limit of clinical relevance (RR≤0.75 and RR≥1.25).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘4. patient satisfaction’ was downgraded by 2 levels to a low GRADE because of imprecision (number of patients <2000) and indirectness of questions asked for actual patient satisfaction.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘5. Duration of hospital stay (days)’ was downgraded by 1 level to a moderate GRADE because of imprecision (number of patients <2000).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘6. Length of procedure (minutes)’ was downgraded by 1 level to a moderate GRADE because of imprecision (number of patients <2000).

The outcome ‘7. Thrombosis’ could not be GRADED because no studies reported on this outcome.

The outcome ‘8. Readmission for operation’ could not be GRADED because no studies reported on this outcome.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: what is the effect of skin closure with continuous sutures versus staples on wound complications, wound infections, wound separation, patient satisfaction, duration of hospital stay and thrombosis in women with obesity that undergo a caesarean section?

P: Women with obesity undergoing a cesarean section

I: Skin closure with staples

C: Skin closure with continuous sutures

O: Wound complications (separation of wound edges, seroma,

hematoma), wound infection, patient satisfaction over recovery, patient satisfaction

with scar, duration of hospital stay, duration of operation, thrombosis, readmission

for wound concern

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered wound complications and wound infections as critical outcome measures for decision making; and patient satisfaction, duration of hospital stay, readmission for wound concern, duration of operation, and thrombosis as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a relative risk difference of 10% (boundaries at 0.90 – 1.10 RR) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for the outcome wound complications. With an absolute risk of approximately 10% the working group considered a number needed to treat of 19 reasonable.

The working group defined a relative risk difference of 25% (boundaries at 0.75 – 1.25 RR) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for all other outcomes.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until December 24th, 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 317 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- At least a subgroup analysis specific for obese participants

- A comparison between staples and continuous sutures for skin closure during cesarean section

- Investigated at least one of the outcomes as reported in the PICO

- Involves the original study data

3 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 1 study was excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 2 studies were included.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Mackeen AD, Schuster M, Berghella V. Suture versus staples for skin closure after cesarean: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 May;212(5):621.e1-10.

- NVOG. Zwangerschap bij Obesitas. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie; 2009 14-1-2020.

- Zaki MN, Wing DA, McNulty JA. Comparison of staples vs subcuticular suture in

class III obese women undergoing cesarean: a randomized controlled trial. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Apr;218(4):451.e1-451.e8.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: what is the best skin closure technique (subcuticular suture or staples) in women with obesity undergoing a caesarean section?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Mackeen, 2015

P: caesarean section I: absorbable subcuticular suture C: nonabsorbable metal staples O: wound complications, pain perception, patient satisfaction, cosmesis, and operating time

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCT’s

Literature search up to July 2014

A: Aabakke 2013 B: Basha 2010 C: Figueroa 2013 D: Huppelschoten 2013 E: Mackeen 2014

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: University of Copenhagen (Denmark), 2010-2011 B: Lehigh Valley Health Network (United States), 2008-2009 C: Prasad Government Medical College and Hospital, Kangra (India), July-September 2013 D: Jeroen Bosch Hospital (The Netherlands), 2007-2009 E: Thomas Jefferson University, Lankenau Medical Center, Yale University (United States), 2010-2012

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: hospital/ university funds, no conflicts of interest B: not reported, no conflicts of interest C: NIH Women's Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) Grant, no conflicts of interest D: University hospital?, no conflicts of interest E: Ethicon, Inc., no conflicts of interest

|

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs comparing subcuticular absorbable suture with nonabsorbable metal staples for caesarean skin closure

Exclusion criteria SR: RCTs that compared absorbable staples, nonabsorbable suture, or stapling devices

5 studies included (obesitas subanalysis)

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; subcutaneous closure

N, mean age A: 145 patients, if >2.5 cm B: 430 patients, if >2.0 cm C: 398 patients, if >2.0 cm D: 145 patients, 50/50 E: 746 patients, if >2.0 cm

Groups comparable at baseline. One trial included both uterine and wound infections in their reported infection rate (B). One study compared suture vs staples by using each method on one half of the incision and randomizing the laterality of each method (A). |

Describe intervention: subcuticular absorbable suture

A: subcuticular suture on a lateral side of the skin incision (3.0 Polyglactin) B: subcuticular suture (4.0 poliglecaprone C: subcuticular suture (4.0 Monocryl sutures) D: subcuticular suture (3.0 poliglecaprone) E: subcuticular suture (4.0 poliglecaprone/ polyglactin)

|

Describe control: nonabsorbable metal staples

A: staples on a lateral side of the skin incision, removal day 3 B: staples, removal day 4 C: staples, removal day 3-4 for Pfannenstiel and 7-10 for vertical incision D: staples, removal day 4 E: staples, removal day 4-10

|

End-point of follow-up: Postoperative wound infections (weeks): A: 12 wk B: 2-4 wk C: 4-6 wk D: 6 wk E: 4-8 wk

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: the number of dropouts were stated, but an intention-to-treat analysis not performed for 2 patients who did not receive assigned closure. B: the number of dropouts were stated, but an intention-to-treat analysis not performed for 5 patients who did not receive assigned closure. C: no incomplete outcome data D: no incomplete outcome data E: no incomplete outcome data

|

1. Wound complications: Defined as a composite of wound infection (all studies), separation (all studies), hematoma (Figueroa 2013, Huppelschoten 2013, Mackeen 2014 and Zaki 2018), seroma (Figueroa 2013, Mackeen 2014 and Zaki 2018) and readmission for wound complications (Basha 2010).

Effect measure: events/total RR (<1 favours suture), [95% CI]: A: 0/4 vs. 0/4: not estimable B: 8/89 vs. 18/70: 0.35 [0.16, 0.76] C: 10/124 vs. 20/141: 0.57 [0.28, 1.17] D: 3/56 vs. 3/69: 1.23 [0.26, 5.87] E: 13/235 vs. 26/238: 0.51 [0.34, 0.75]

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.51 [95% CI 0.34 to 0.75] favoring suture Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

Facultative: “Obese patients were 49% less likely to have wound complications if their incisions were closed with suture as compared to staples.

Studies were found to be of high quality, with low risk of bias and low heterogeneity. However to low amount of participants, obese patients specifically, makes it difficult to extrapolate outcomes to the obese population. Besides this, the studies used different definitions of “wound complications” with some studies only including wound infections and wound separation (A, B) , while others also included haematoma (C, D, E), seroma (D, E) and readmission for wound concern (E)

Level of evidence: low GRADE for the outcome wound complications due to the low number of participants (<2000) and different definitions of wound complications used in different studies.”

|

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Zaki, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: 2 teaching hospitals in California, USA: University of California-Irvine Medical Center in Orange and Miller Children’s and Women’s Hospital in Long Beach

Funding and conflicts of interest: this study was funded by a grant from the Memorial Care Medical Center Foundation. The authors report no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Women undergoing planned caesarean delivery who were at least 23 weeks gestational age and with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2, or women admitted for induction of labour or in spontaneous labour who met the BMI criteria and had adequate pain control (pain scale ≤3 on a 1-10 pain scale)

Exclusion criteria: women with reported hypersensitivity to staples or potential immune suppression including infection with HIV, chronic steroid use, or active lupus.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 121 Control: 121

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age ± SD: I: 31.1 ± 5.6 C: 31.4 ± 5.3

Nulliparous (%): I: 30 (25.2%) C: 31 (26.1%)

BMI (kg/m2) ± SD: I: 45.1 ± 4.4 C: 46.2 ± 5.5

The baseline characteristics were similar across groups. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): Subcutaneous suture with either 4-0 polyglactin 910 or 3-0 poliglecaprone 25 after a standard subcutaneous closure, depending on the surgeon’s choice.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Stainless steel staples after a standard subcutaneous closure

|

Length of follow-up: 7-14 days after hospital discharge a control visit and 6-8 weeks after hospital discharge a telephone questionnaire

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%): 2/121 (1.7%) Reasons (describe): two women were lost to follow up.

Control: N (%): 1/121 (0.8%) Reasons (describe): one woman was lost to follow up

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%): 0 Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) 1/121 (0.8%) Reasons (describe): one patient in the staple group was withdrawn due to failure to follow the study protocol |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): 1. Wound complications (2 wk postpartum): Defined as infection, superficial separation or deep separation.

I: 16/119 (13.4%) O: 15/119 (12.6%) P (Fisher exact test): 0.85

2. Wound infection (2 wk postpartum): Defined as ‘those meeting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of surgical site infections and requiring antibiotic therapy’, and were assessed at two weeks postpartum.

I: 2/119 (1.7%) C: 3/119 (2.5%) P (Fisher exact test): 0.65

3. Wound margin separation (2 wk postpartum): Wound margin separations were identified as either superficial (<0.5 cm deep and only involving the dermis layer) or deep (>0.5 cm in depth and requiring packing or reclosure) resulting from hematoma or seroma (Zaki 2018).

Superficial separation I: 11/119 (9.2%) O: 11/119 (9.2%) P (Fisher exact test): 0.47

Deep separation I: 0/119 O: 3/119 (2.5%) P (Fisher exact test): 0.12

4. Patient satisfaction Patient satisfaction consisted of an survey assessment of pain (1=least, 10=most), wound appearance satisfaction (1=least, 10=most), concern about wound healing (1=least, 10=most), wound recovery satisfaction (‘would you have the same closure again’ percentage answering ‘yes’).

Patient wound appearance satisfaction (1=least, 10=most) I: 10 (9-10) (n=113) O: 10 (9-10) (n=114) P (Mann-Withney U test): 0.99

Patient wound recovery satisfaction (Would you have the same closure again?): I: 108/113 (93.9%) O: 98/114 (83.1%) P (Mann-Withney U test): 0.01

5. Length of procedure (min) I: 55.8 ± 26.0 (n=119) O: 43.4 ± 21.9 (n=119) P (chi-square test) <.001

6. Duration of hospital stay (days) I: 4.9 ± 2.1 O: 4.9 ± 0.9 P (chi-square test): 1.00

|

“There were no significant differences in wound complications, wound infections or wound separation. However, total operative time was significantly more for the suture intervention with an average of 12 minutes more. Women expressed a preference for the suture intervention.” |

Tables of quality assessment

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Mackeen, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, (in the individual studies). |

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Zaki, 2018 |

“Randomization, using predetermined computer-generated blocks of 20, was achieved using sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes, which were opened by the obstetrician at the time of surgery prior to skin preparation. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely: patients were not blinded, but this might not have had influence on outcomes such as wound complications, wound infections etc. |

Unlikely: surgeons were not blinded for the procedure, however this is not expected to influence outcomes, because outcomes were not assessed by the surgeons. |

Unlikely: the assessing nurse and study team used a standardized data collection form and objective wound assessment forms. |

Unlikely: the outcomes in the results were reported such as described in the methods section. |

Unlikely: in both groups the amount of loss to follow up was small and comparable. |

Unlikely: groups were analysed such as to which group they were assigned. |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Abbas, 2019 |

Commentary paper |

|

Alalfy, 2019 |

Commentary paper |

|

Alexander, 2006 |

Narrative review |

|

Ayres-de-Campos, 2015 |

Narrative review |

|

Caughey, 2005 |

Commentary paper |

|

Conner, 2014 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Gould, 2007 |

Narrative review |

|

Ibrahim, 2014 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Johnson, 2006 |

Wrong participants: no obese patients |

|

Kawakita, 2017 |

Narrative review |

|

Machado, 2012 |

Narrative review |

|

Maged, 2019 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Nuthalapaty, 2013 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Nuthalapaty, 2011 |

Commentary paper |

|

Pierson, 2018 |

Narrative review |

|

Ramsey, 2005 |

Wrong intervention |

|

Ripamonti, 2017 |

Narrative review |

|

Sarsam, 2005 |

Narrative review |

|

Smid, 2017 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Stapleton, 2015 |

Narrative review |

|

Subramaniam, 2014 |

Wrong participants: no obese patients |

|

Tipton, 2011 |

Narrative review |

|

Tuuli, 2016 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Tuuli, 2011 |

More recent SR available |

|

Yamasato, 2016 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Zaki, 2016 |

More recent SR and RCT available |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 27-12-2022

|

Module |

Regiehouder(s) |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling |

|

Agraves of andere hechtingsmethode na sectio bij vrouwen met obesitas |

NVOG |

2022 |

2027 |

5 jaar |

NVOG |

Nieuw wetenschappelijk onderzoek, veranderingen in organisatie van zorg |

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor vrouwen met hypertensieve aandoeningen in de zwangerschap.

Werkgroep

- Dr. C.J. (Caroline) Bax, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVOG, voorzitter stuurgroep

- Dr. S.V. (Steven) Koenen, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het ETZ, Tilburg, NVOG, lid stuurgroep

- Dr. J.J. (Hans) Duvekot, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC, NVOG, lid stuurgroep

- Dr. H.C.J. (Liesbeth), Scheepers, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Maastricht Universitair Medisch Centrum +, NVOG

- Msc. D.H. (Robert) Strigter, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Deventer Ziekenhuis, NVOG

- Dr. M.D. (Mallory) Woiski, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Radboud UMC, NVOG

- Dr. I.M. (Inge) Evers, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Meander Medisch Centrum Amersfoort, NVOG

- Dr. L. (Lia) Wijnberger, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Rijnstate Ziekenhuis Arnhem, NVOG

- Dr. I.H. (Ingeborg) Linskens, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC, NVOG

- Dr. S. (Sander) Galjaard, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC, NVOG

- Dr. R.C. (Rebecca) Painter, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam Universitair Medisch Centrum, NVOG

- Drs. I.C.M. (Ingrid) Beenakkers, anesthesioloog, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, NVA

- Drs. M.L. (Mark) van Zuylen, anesthesioloog in opleiding in het Amsterdam UMC, NVA

- Dr. S. (Sabine) Logtenberg, klinisch verloskundige, werkzaam in OLVG Oost Amsterdam en Academie Verloskunde Amsterdam Groningen, KNOV

- Msc. J. (José) Hollander-Boer, verloskundige (np), werkzaam bij Academie Verloskunde Amsterdam Groningen, KNOV.

- Dr. V.C. (Vera-Christina) Mertens, secretaris Stichting Zelfbewustzwanger

- Msc. J. (Jacobien) Wagemaker, Care4Neo

- I. (Ilse) van Ee, adviseur patiëntenbelang, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland.

- MSc. J.C. (Anne) Mooij, adviseur, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland.

Meelezers

- Leden van de Otterlo- werkgroep (2020-2021)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. I.M. (Irina) Mostovaya, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. L. (Laura) Viester, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. M.A.C. (Marleen) van Son, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- MSc. Y.J. (Yvonne) Labeur, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Bax (voorzitter stuurgroep) |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog Amsterdam UMC 0,8 fte |

Gastvrouw Hospice Xenia Leiden (onbetaald), Lid commissie kwaliteitsdocumenten NVOG, Voorzitter 50 modulenproject NVOG, Voorzitter commissie Otterlo NVOG, Penningmeester werkgroep infectieziekten NVOG, Lid kernteam NIPT consortium, Lid werkgroep voorlichting en deskundigheidsbevordering RIVM, Lid werkgroep implementatie scholing RIVM, Lid werkgroep nevenbevindingen NIPT RIVM |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Beenakkers |

Anesthesioloog UMCU/WKZ |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Duvekot (lid stuurgroep) |

Gynaecoloog, Erasmus MC (full time) |

Directeur 'medisch advies en expertise bureau Duvekot', Ridderkerk, ZZP'er |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Evers |

Gynaecoloog, Meander Medisch Centrum |

Lid van Ciekwal, Werkgroep multidisciplinaire richtlijn extreme vroeggeboorte, NVOG |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Galjaard |

Gynaecoloog ErasmusMC, Rotterdam |

Associate member Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group (DPSG, onbezoldigd) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Hollander-Boer |

Docent verloskunde -> Academie Verloskunde Amsterdam Groningen (AVAG) 0.8 Fte, (Verloskundige -> oproepcontract Verloskundige stadspraktijk Groningen (zelden)), Wijziging oktober 2021: oproepcontract laten beëindigen. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Koenen (lid stuurgroep) |

Gynaecoloog, ETZ , Tilburg |

Incidenteel juridische expertise (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Linskens |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Logtenberg |

Academie Verloskunde Amsterdam Groningen: 3 dagen docent, OLVG Oost Amsterdam 1 dag in de week klinisch verloskundige |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Mertens |

Patiëntvertegenwoordiger namens Stichting Zelfbewust zwanger (onbezoldigd) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Mooij |

Adviseur Patiëntenbelang, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Painter |

Gynaecoloog, aandachtsgebied maternale ziekte 0,8FTE, Associate Professor (voor de grootte van de aanstelling als gynaecoloog) Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC |

Voorzitter Special Invest group NVOG Zwangerschap en diabetes en obesitas onbetaald, Lid gezondheidsraad commissie Voeding en Zwangerschap vacatiegelden gaan naar mijn werkgever, lid richtlijncommissie Chirurgische behandeling van obesitas (NVVH) onbetaald, lid namens NVOG bij RIVM commissie Hielprikscreening onbetaald, Voorzitter organiserend comité congres ICHG 2019 onbetaald, cluster coördinator regio Noord-Holland NVOG Consortium 2, lid Wetenschapscommissie Pijler Obstetrie NVOG onbetaald, Lid koepel wetenschap namens Pijler Obstetrie |

Principal lnvestigator Leading the Change gefinancierd onderzoek TANGO DM. naar de afkapwaarde voor diabetes gravidarum, Project team lid Zon MW gefinancierd onderzoek SUGARDIP, naar diabetes gravidarum behandeling met orale medicatie versus insuline, Project team Nederlandse Hartstichting WOMB project naar de lange termijn uitkomsten van vrouwen die subfertiel waren en obesitas, Van geen van deze projecten wordt een belang van de financier/sponsor vermoed, Gepubliceerd op het gebied van obesitas en zwangerschap. Deze artikelen zouden genoemd kunnen worden in de richtlijn, Wetenschappelijk adviseur bij patiëntenvereniging stichting ZEHG (hyperemesis gravidarum) |

Geen betrokkenheid als schrijver of meelezer bij modules waarin de eigen artikelen van de werkgroeplid terug zouden kunnen komen in de systematische literatuuranalyse |

|

Scheepers |

Gynaecoloog/perinatoloog, MUMC |

Vicevoorzitter perinatale audit, onbetaald, Wetenschappelijk coördinator regioconsortium Limburg, onbetaald |

Projectleider SIMPLE studies, ontwikkeling keuzehulp vaginaal bevallen na eerdere keizersnede, geen huidige financiële belangen. |

Geen |

|

Stigter |

Waarnemend gynaecoloog vakgroep verloskunde & gynaecologie Deventer Ziekenhuis (0.2 FTE), waarnemend gynaecoloog vakgroep verloskunde & gynaecologie Gelre Ziekenhuizen locatie Apeldoorn (0.7 FTE) |

Lid werkgroep Otterlo tot 01-09-2020, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Ee |

Adviseur Patiëntenbelang, Patientenfederatie |

Vrijwilliger Psoriasispatiënten Nederland, - coördinator patiëntenparticipatie en onderzoek en redactie lid centrale redactie, - onbetaalde werkzaamheden (soms vacatiegelden) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Zuylen |

Anesthesioloog i.o. Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Wagemaker |

Projectleider PATH in het Maasstad Ziekenhuis Rotterdam 0,55 fte, ZZP Adviseur, trainer, onderzoeker op Family Centered en Single Room Care wisselend aantal uren 0,25 - 0,50 fte |

Vrijwilliger Vereniging van Ouders van Couveusekinderen - ervaringsexpert richtlijnontwikkeling, promotie Kwaliteitskader Kwaliteitscriteria VOC - soms vacatiegelden, Vrijwilliger V&VN kinderverpleegkunde - ondersteuning in projecten, projectadvies op opleiding en bijscholing - soms vacatiegelden |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Wijnberger |

Gynaecoloog, perinatoloog, Rijnstate ziekenhuis Arnhem |

VSV werkgroepen, medisch coördinator, NVOG: Otterlo werkgroep, commissie wetenschap (alles onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Woiski |

Gynaecoloog |

Lid werkgroep Otterlo |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van patiëntvertegenwoordigers van verschillende patiëntverenigingen voor de Invitational conference en afvaardigen van patiëntenverenigingen in de clusterwerkgroep. Het verslag hiervan is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie per module ook ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)’. De conceptrichtlijn wordt tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan de betrokken patiëntenverenigingen.

Implementatie

|

Aanbeveling |

Tijdspad voor implementatie: 1-3 jaar of >3 jaar |

Verwacht effect op kosten |

Randvoorwaarden voor implementatie (binnen aangegeven tijdspad) |

Mogelijke barrières voor implementatie1 |

Te ondernemen acties voor implementatie2 |

Verantwoordelijken voor acties3 |

Overige opmerkingen |

|

Alle aanbevelingen van deze module |

<1 jaar |

Geen |

Kennis van richtlijn |

Geen kennis van richtlijn |

Kennis nemen van richtlijn |

NVOG |

|

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vrouwen met een sectio in de voorgeschiedenis en obesitas in de zwangerschap. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door patiëntenverenigingen tijdens de Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaarden zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule wordt aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren worden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren wordt de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule wordt aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.