Profylactische antibiotica

Uitgangsvraag

Is het noodzakelijk om profylactische antibiotica te geven bij patiënten met acute traumatische wonden?

Aanbeveling

Spoel een wond altijd met lauwwarm kraanwater om een infectie te voorkomen.

Informeer de patiënt over de nadelen van preventief antibioticagebruik.

Geef niet routinematig systemische antibiotica aan patiënten met éénvoudige (wondcategorie 1 en 2), acute traumatische wonden.

Geef geen topicale antibiotica aan patiënten met éénvoudige (wondcategorie 1 en 2), acute traumatische wonden.

Instrueer patiënten met eenvoudige (wondcategorie 1 en 2), acute traumatische wonden om bij tekenen van infectie laagdrempelig contact op te nemen met de zorgverlener.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar de verschillen in uitkomsten tussen behandeling met en zonder systemische profylactische antibiotica bij patiënten met acute, traumatische wonden. Wondinfectie werd gedefinieerd als cruciale uitkomstmaat. Pijn, wondgenezing en andere adverse events werden gedefinieerd als belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

Op basis van de gevonden studies kan worden geconcludeerd dat de incidentie van wondinfecties iets lager is na behandeling met profylactische antibiotica in vergelijking met de placebo groep dan wel de groep die niet werd behandeld met antibiotica (Altergott, 2008; Berwald, 2014; Halhalli, 2018; Zehtabchi, 2007). Echter, het betrouwbaarheidsinterval omvat de waarde van geen effect, daarom is het ook zeker mogelijk dat deze bevinding op toeval berust. In zowel de groepen met en zonder systemische profylactische antibiotica werden geen ernstige wondinfecties gerapporteerd. Dat wil zeggen dat de infecties die optreden goed te behandelen zijn en de patiënt hier op de lange termijn hoogstwaarschijnlijk geen nadelige effecten van zal ondervinden. De overall bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaat wondinfecties komt uit op laag. Er ligt hier een kennislacune.

Het type antibioticum dat wordt gegeven in de geïncludeerde studies betreft in veel gevallen cefalexine (Altergott, 2008; Berwald, 2014; Halhalli, 2018). In Nederland zou men eerder kiezen voor een middel als flucloxacilline of claritromycine. De werkgroep schat in dat het gebruik van deze antibiotica dezelfde resultaten geeft als het gebruik van cefalexine gezien een redelijk vergelijkbaar werkingsspectrum. Ook keken de geïncludeerde studies met name naar wonden aan de handen. Het is onbekend of de lagere kans op wondinfecties ook geldt voor toepassing van profylactische antibiotica bij wonden op andere lichaamsdelen. Er ligt hier een kennislacune.

Topicale antibiotica

Op basis van het optreden van antibioticaresistentie is de werkgroep van mening dat het gebruik van topicale antibiotica geen plaats heeft binnen de wondzorg van acute traumatische wonden (Banerjee, 2017).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Het niet voorschrijven van antibiotica kan leiden tot onenigheid of ongerustheid bij de patiënt wanneer deze wél antibiotica denkt nodig te hebben. Het goed uitleggen van de nadelen van antibiotica maakt gedeelde besluitvorming mogelijk. Informeer patiënten daarom over de nadelen van preventieve antibiotica toediening, waarom profylactische antibiotica niet noodzakelijk zijn, en bespreek eventuele symptomen of signalen van een mogelijk geïnfecteerde wond.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van antibiotica hangen af van het type antibiotica wat men voorschrijft.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In eerste instantie is een goede wondverzorging belangrijk in het voorkomen van wondinfecties. Het spoelen onder lauwwarm kraanwater volstaat, zie module wond reiniging: kraanwater of zoutoplossing. Verder is het belangrijk om visuele verontreiniging en mogelijk niet vitaal weefsel te verwijderen. Ook is een tetanusbooster/ -vaccinatie aanbevolen voor de patiënten bij wie deze verlopen is of deze nog nooit hebben gehad.

De werkgroep is van mening dat de potentiële voordelen van profylactische antibiotica (het voorkomen van een wondinfectie) te gering zijn, en niet opwegen tegen de nadelen (mogelijke bijwerkingen en het risico op antibioticaresistentie). Vandaar dat de werkgroep ervoor kiest om het gebruik van profylactische antibiotica niet routinematig aan te bevelen.

Vanuit de literatuur komt geen bewijs naar voren dat het daadwerkelijk beter is om patiënten met vieze (niet-chirurgische) handwonden systemische antibiotica voor te schrijven. Bij deze patiënten is een goede follow-up belangrijk zodat een eventuele infectie tijdig kan worden opgemerkt en behandeld. Het is belangrijk om patiënten goed te instrueren om bij roodheid van de wond en / of pus laagdrempelig contact op te nemen met een arts. De gevolgen van een infectie kunnen namelijk ernstig zijn waardoor men functieverlies van bijvoorbeeld de hand riskeert. De arts kan in dit geval beoordelen of het starten met systemische antibiotica alsnog gewenst is. De werkgroep adviseert om de lokale protocollen te gebruiken voor het besluit welk antibioticum te geven.

Ook bij patiënten met een co-morbiditeit of een hoger risico op een infectie (bijvoorbeeld vanwege een verminderde lokale of systemische afweer) is het belangrijk om een goede follow-up te doen en deze patiënten duidelijke instructies mee te geven.

De werkgroep ziet geen grote bezwaren wat betreft de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie van de aanbeveling. In Nederland is men terughoudend wat betreft het voorschrijven van profylactische antibiotica, om antibioticaresistentie zoveel mogelijk te voorkomen. Als alternatief voor het toedienen van profylactische antibiotica is het belangrijk dat de zorgverlener de patiënt met een acute wond goed instrueert om bij tekenen van wondinfectie laagdrempelig contact op te nemen met de zorgverlener zodat deze infectie op tijd behandeld kan worden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De werkgroep is van mening dat de potentiële voordelen van profylactische antibiotica (voorkomen van een wondinfectie) te gering zijn, en niet opwegen tegen de nadelen (mogelijke bijwerkingen en het risico op antibioticaresistentie). Het is daarbij belangrijk om patiënten goed te informeren over de nadelen van preventief antibioticagebruik om gedeelde besluitvorming mogelijk te maken.

Het is belangrijk dat de zorgverlener de patiënt met een acute wond goed instrueert om bij tekenen van wondinfectie contact op te nemen met de zorgverlener zodat deze infectie op tijd behandeld kan worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het is op dit moment onduidelijk of profylactische antibiotica gegeven dient te worden bij patiënten met acute traumatische wonden. Er heerst op dit moment praktijkvariatie omtrent het gebruik van systemische antibiotica. De werkgroep wil uitzoeken of het geven van profylactische antibiotica bijdraagt aan de wondgenezing en het voorkomen van infecties bij eenvoudige acute traumatische wonden. Chirurgische wonden worden hierbij buiten beschouwing gelaten omdat deze niet vergelijkbaar zijn met eenvoudige acute traumatische wonden.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Adults

Wound infection

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with systemic prophylactic antibiotics may result in little to no difference in wound infections when compared with no systemic prophylactic antibiotics in adults with acute wounds.

Sources: (Berwald, 2014; Halhalli, 2018; Zehtabchi, 2007). |

Wound healing

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with systemic prophylactic antibiotics may hamper wound healing when compared with no systemic prophylactic antibiotics in adults with acute wounds.

Sources: (Zehtabchi, 2007) |

Adverse events

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with systemic prophylactic antibiotics may increase adverse events when compared with no systemic prophylactic antibiotics in adults with acute wounds.

Sources: (Berwald, 2014; Halhalli, 2018) |

Patient satisfaction

|

Low GRADE |

Treatment with systemic prophylactic antibiotics may result in little to no difference in patient satisfaction compared with no systemic prophylactic antibiotics in adults with acute wounds.

Sources: (Halhalli, 2018) |

Pain

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of systemic prophylactic antibiotics on pain when compared with no systemic prophylactic antibiotics in adults with acute wounds. |

Children

Wound infection

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic prophylactic antibiotics on wound infection when compared with no systemic prophylactic antibiotics in children with acute wounds.

Sources: (Altergott, 2008) |

Wound healing, adverse events, pain, and patient satisfaction

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of systemic prophylactic antibiotics on wound healing, adverse events, pain, and patient satisfaction when compared with no systemic prophylactic antibiotics in children with acute wounds. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Adults

The systematic review of Zehtabchi (2007) described clinical trials that compared administration of systemic antibiotics of any type for any duration in addition to standard wound care, to standard wound care alone for emergency department patients with simple hand lacerations presenting within 12 hours of injury. The search in the study of Zehtabchi (2007) was limited to randomized clinical trials or systematic reviews using prophylactic antibiotics to prevent wound infection in hand lacerations. Studies that included patients with bite and burn wounds or wounds involving special structures (i.e., tendons, bones, large vessels, and nerves) were excluded. Lacerations that contained foreign bodies easily removed in the emergency department were considered uncomplicated. Four randomized trials, involving a total of 1187 patients, met the inclusion criteria (Beesley 1975; Grossman, 1981; Haughey, 1981; Roberts and Teddy, 1977). All four trials tested the use of prophylactic antibiotics for prevention of simple hand lacerations compared to a control group (placebo or no intervention). The authors excluded the study from Haughey (1981) (Zehtabchi, 2007) from the final analysis as they rated this study as highly susceptible to bias. The other three studies were included in a meta-analysis. The following outcome measures were included: wound infection and wound healing.

Berwald (2014) described a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial in 2 urban academic emergency departments. Adult (≥ 18 years old) patients with simple hand lacerations were randomized to either 500 mg cephalexin (n=25), 300 mg clindamycin (n=24), or placebo (n=24). Placebo was 2 gram of granulated sugar in the study capsule. All medications were prescribed every six hours for seven days. Five patients were lost to follow-up. The maximum length of follow-up was 30 days. The following outcome measure was included: wound infection.

Halhalli (2018) described a prospective, single-center, randomized, double- blind clinical trial conducted in patients who presented to the emergency department with simple hand lacerations. Adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with simple hand lacerations were randomized to receive either 500 mg cephalexin monohydrate (n=109) or wound cleaning with an antiseptic and dressing in a blinded fashion (n=110). The maximum length of follow-up was seven days. The following outcome measures were included: wound infection, adverse events and patient satisfaction.

Children

Altergott (2008) performed a prospective randomized control trial of pediatric patients who presented to an urban children’s hospital with trauma to the distal fingertip, requiring repair. Patients were randomized in two groups. Patients in group one (n=66) received no antibiotics after fingertip repair, while patients in group two (n=69) received 50 mg/kg cephalexin (divided three times daily) upon discharge for seven days. Repairs were performed in a standardized fashion, and all patients were reevaluated in the same emergency department in 48 hours and again by phone 7 days after repair. The following outcome measures were included: wound infection.

Results

Adults

Wound infection

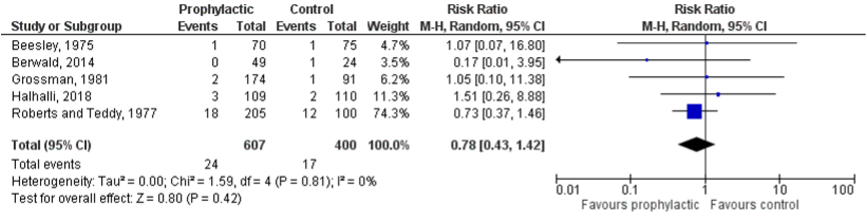

The outcome measure wound infection was reported in three studies (Berwald, 2014; Halhalli, 2018; Zehtabchi, 2007). The pooled incidence of wound infections in the intervention group was 24/607 (4.0%), compared to 17/400 (4.3%) in the control group. This results in a pooled weighted risk ratio (RR) of 0.78 (95% CI 0.43 to 1.42) (see Figure 1). Patients who received prophylactic antibiotics had a 0.3% lower risk of developing a wound infection compared to patients who did not receive antibiotics. This was not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Wound infections in patients with simple, acute, traumatic wounds

Z: test of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Wound healing

The outcome measure wound healing was reported in one study (Zehtabchi, 2007). Roberts and Teddy (1997) (Zehtabchi, 2007) reported imperfect wound healing in 46/205 of the patients who received prophylactic antibiotics (22%), compared to 12/100 of patients who received a placebo (12%). This results in a RR of 1.87 (95% CI 1.04 to 3.37). This means that patients who received prophylactic antibiotics had an almost 2 times higher risk of imperfect wound healing compared to patients who did not receive antibiotics. The risk difference was 10%, which results in a number needed to treat (NNT) of 10 patients. This was considered clinically relevant.

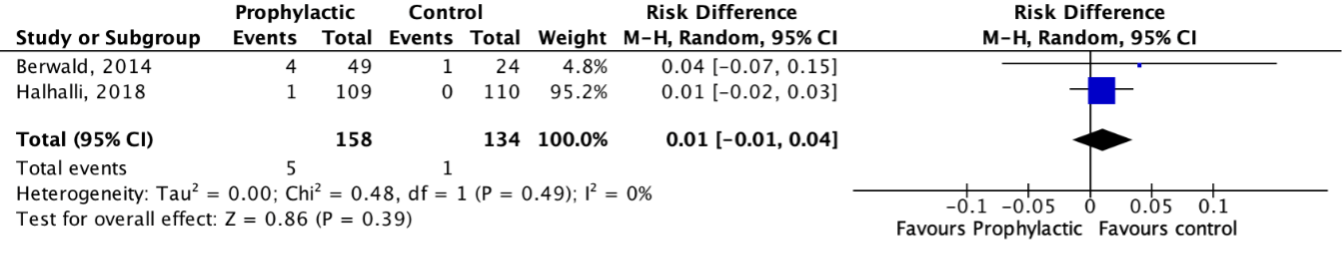

Adverse events

Adverse events were reported in two studies (Berwald, 2014; Halhalli, 2018). The results were pooled in a meta-analysis. The pooled incidence of adverse events in the intervention group was 5/158 (3.2%), compared to 1/134 (0.7%) in the control group. This resulted in a pooled RD of 0.01 (95%CI -0.01 to 0.04) (see Figure 2). This is not considered a clinically relevant difference. The adverse events reported in the group who received prophylactic antibiotics were: diarrhea, dizziness, palpitation, after-taste in mouth and nausea, versus diarrhea in the control group.

Figure 2. Adverse events in patients with simple, acute, traumatic wounds

Z: test of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Patient satisfaction

Halhalli (2018) reported patient satisfaction (measured on a 10-point numeric rating scale (NRS; 0=not satisfied; 10=satisfied)). The mean patient satisfaction rates were similar in the prophylaxis group (9.25, 95% CI 9.06 to 9.44); and in the group with no prophylaxis (9.46, 95% CI 9.30 to 9.62). These differences were not considered clinically relevant.

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures: antibiotic resistance, pain and costs in adult patients with acute wounds.

Children

Wound infection

The outcome measure wound infection was reported in one study (Altergott, 2008). The incidence of wound infection in children in the study of Altergott (2008) in the intervention group was 1/66 (1.5%), compared to 1/69 (1.4%) in the control group. This results in an RR of 1.05 (95 % CI 0.07 to 16.37). Children who receive prophylactic antibiotics have a 0.1% increased risk of developing a wound infection, compared to children who did not receive prophylactic antibiotics. This was not considered clinically relevant.

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures: wound healing, adverse events, pain, patient satisfaction, and costs in children with acute wounds.

Level of evidence of the literature

Adults

Wound infection

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure wound infection comes from randomised clinical trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the small number of patients (imprecision, -1) and the confidence interval crosses the boundary of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

Wound healing, adverse events and patient satisfaction

The level of evidence regarding these outcome measures comes from randomised clinical trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence regarding was downgraded by two levels because of the small number of patients (imprecision, -1), and because the confidence interval crosses both boundaries of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence could not be graded for the outcome measure pain, as this was not reported in the included studies.

Children

Wound infection

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure wound infection comes from a randomised clinical trial and therefore starts high. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure wound infection was downgraded by three levels because of lack of blinding (risk of bias, -1), the small number of patients (imprecision, -1), and because the confidence interval crosses both boundaries of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence could not be graded for the outcome measures: wound healing, adverse events, pain, and patient satisfaction as these were not reported in the included studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

Search and select

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Are systemic prophylactic antibiotics beneficial in reducing the number of wound infections compared to no use of systemic prophylactic antibiotics in patients with acute wounds?

P: patients with acute wounds (traumatic);

I: systemic prophylactic antibiotics;

C: no systemic prophylactic antibiotics;

O: wound infection; wound healing; adverse events; pain; patient satisfaction; costs.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered wound infection as critical outcome measures for decision making. Wound healing, adverse events, patient satisfaction, and costs were considered important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the guideline development group did not define the outcome measure ‘costs’ but used the definitions used in the studies. The outcome measure ‘costs’ was only reported in a descriptive manner; clinically relevant differences and GRADE were not applied. Table 1 shows the definition of the remaining outcome measures, including the clinically relevant differences.

Table 1. Clinically relevant differences

|

Outcome measure |

Definition |

measurement instrument |

Clinically relevant differences |

|

Wound infection |

Infection rate (%)

|

Subjective: clinical suspicion Objective: culture, biopsy, number of bacteria, CRP, BSE or infection parameters. |

RR<0.9 or RR>1.0 |

|

Wound healing |

Complete wound healing (%) |

|

≥10% difference in healed wounds (NNT≤10) |

|

Adverse events |

Caused by the intervention (%) |

|

RR<0.95 or RR>1.05 |

|

Pain |

During dressing change |

VAS, NRS, VRS, COMFORT/FLACC |

≥2 points |

|

Patient satisfaction |

|

PSQ-18 and PSQ-36, COPS, NIVEL, CAHPS®, Responsiveness of health systems (WHO), QUOTE |

≥2 points |

Search and select (Methods)

The databases of Medline (via OVID and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 9 February 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 441 hits. Only systematic reviews and randomized clinical trials (RCT) were included when they compared the use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with acute wounds with no use of prophylactic antibiotics or placebo. Sixteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, twelve studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

Referenties

- Altergott C, Garcia FJ, Nager AL. Pediatric fingertip injuries: do prophylactic antibiotics alter infection rates? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008 Mar;24(3):148-52. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181666f5d. PMID: 18347491.

- Banerjee S, Argáez C. Topical Antibiotics for Infection Prevention: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2017 Mar 30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK487430/

- Berwald N, Khan F, Zehtabchi S. Antibiotic prophylaxis for ED patients with simple hand lacerations: a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2014 Jul;32(7):768-71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.03.043. Epub 2014 Apr 2. PMID: 24792937.

- Halhalli, H. C., Yigit, Y., Karakayali, O., & Yilmaz, S. (2018). Antibiotic prophylaxis regimes for simple hand lacerations. Notfall+ Rettungsmedizin, 21(4), 303-307.

- Tong QJ, Hammer KD, Johnson EM, Zegarra M, Goto M, Lo TS. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of prophylactic topical antibiotics for the prevention of uncomplicated wound infections. Infect Drug Resist. 2018 Mar 16;11:417-425. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S151293. PMID: 29588605; PMCID: PMC5858851.

- Zehtabchi, S. (2007). The role of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of infection in patients with simple hand lacerations. Annals of emergency medicine, 49(5), 682-689.

Evidence tabellen

Systematic review(s)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

|

Zehtabchi, 2007 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to December 2005.

A: Grossman (1981) B: Haughey (1981) C: Roberts and Teddy (1977) D: Beesley (1975)

Study design: Randomized controlled trials

Setting and Country: A: USA B: USA C: England D: England

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The author reports this study received no outside funding or support. |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

4 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N patients A: N=265 B: N=394 C: N=368 D: N=145

Mean age: A: Not reported B: Not reported C: Not reported D: Not reported

Sex: A: Not reported B: Not reported C: Not reported D: Not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention

A: I: Single dose of IM cefazolin (1 g); II: oral cephalexin 250 mg every 6h for 6 days

B: Oral cephalexin for 5 days (250 mg every 6h for adults and 6.25 mg/kg/d for children

C: I: 7 day course or oral flucloxacillin (1 g/d for adults and 0.5 g/d for children <5y, divided in 4 doses/day); II: single IM dose (1 vial for adults, ½ vial for children 2-10y, and ¼ vial for children <2y) of a combination of procaine, benethamine, and benzyl penicillin patients;

D: 5 day course of oral magnapen (flucloxacillin and ampicillin), 500 mg 4 times a day for 5 days.

|

Describe control

A: Single IM dose of placebo B: No treatment C: No treatment D: Placebo capsules 4 times a day for 5 days |

End-point of follow-up A: not reported B: 7-10 days C: 7 days postinjury D: 5 days postinjury |

Wound infection, rate of infection; n/N

A: Rate of infection intervention: 1.15%; 2/174 Rate of infection control: 1.10%; 1/91 RR= 1.05 (95% CI= 0.09 to 11.38)

C: Rate of infection intervention: 8.80%; 18/205 Rate of infection control: 12.0%; 12/100 RR= 0.73 (95% CI= 0.37 to 1.46)

D: Rate of infection intervention: 1.40%; 1/70 Rate of infection control: 1.30%; 1/75 RR= 1.07 (95% CI= 0.07 to 16.80)

*The study of Haughey was excluded from the analysis. This trial was highly susceptible to bias because of use of pseudorandomization according to medical record number. There was also a complete absence of concealment of randomization and of blinding, the lack of the use of a placebo, and a clear violation of intention-to-treat phenomenon involving 20% of the patients initially assigned to active therapy. Furthermore, patients who were lost to follow-up were simply excluded from the study and their numbers were not reported, rendering it impossible to assess the impact of this potential source of bias. These factors make the validity of this trial highly questionable. |

Randomized controlled trials

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison/ control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

|

Halhalli, 2018 |

Type of study: A prospective, single-center, randomized, double-blind clinical trial.

Setting and country: The study site was an academic tertiary hospital in Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: H.C.Halhalli, Y. Yigit, O. Karakayali and S. Yilmaz declare that they have no competing interest.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

|

Inclusion criteria: Adult patients aged 18 years and older; Patients with simple hand lacerations.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with injuries to more than one body site; Patients with accompanying fractures; Patients with an incision length of more than 5 cm; Patients who had blunt injuries; Patients who had more than 12h prior to admission; Patients with injuries from animal and human bites; Patients with contaminated injuries; Patients who used antibiotics prior to admission (within 72h); Patients who had a disease that could have affected wound healing (diabetes mellitus, immune deficiency, transplantation, HIV/AIDS, and cancer); Patients who refused to give consent.

N total at baseline: Intervention: N=109 Control: N=110

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age I: 36.44 C: 35.44

Sex: I: 77/109 (70.6%) M C: 75/110 (68.2%) M

Laceration length (cm): I: 3.1 cm C: 3.4 cm

Suturing (yes/no): I: 18/89 (20.2%) C: 21/89 (23.6%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Oral 500 mg cephalexin monohydrate

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Wound cleaning with antiseptic and dressing in a blinded fashion. |

Length of follow-up: 7 days

Loss-to-follow-up: N=37 did not come to the control examination. The number of patients per treatment group were not further specified.

|

Wound infection, n/N (%) Intervention I: 3/109 (2.7%) Control: 2/110 (1.8%)

Adverse events, n/N (%) Intervention I: 1/109 (0.9%) (nausea) Control: 0/110 (0%)

Patient satisfaction, mean (95% C) Intervention I: 92.5 (95% CI= 95% to 90.6 to 94.4) Control: 94.6 (95% CI= 93 to 96.2)

|

|

Berwald, 2014 |

Type of study: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial

Setting and country: 2 urban academic centers, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with simple hand lacerations requiring repair (by sutures, staples, or tissue adhesives).

Exclusion criteria: Immunocompromised patients; Current or recent use of any antibiotics; Gross infection as determined by the treating clinician; Grossly contaminated wounds by dirt or other foreign substances; Allergy to clindamycin or cephalexin; Bites; Crushed injuries; Lacerations inflicted more than 12 hours before ED visit; Pregnant or breast-feeding women; Diabetics.

N total at baseline: I-1: N=25 I2: N=24 Control: N=24

Important prognostic factors2: Median (IQR) age: I1: 39 (26 to 56) I2: 42 (32 to 58) C: 40 (29 to 52) P=0.851

Sex, n (%, 95% CI): I: N=15 (60%, 41% to 77%) I2: N=18 (75%, 55% to 88%) C: N=19 (79%, 59% to 91%) P=0.295

Length of the wound, median (IQR): I1: 2 (2 to 2.5) I2: 1.5 (1.25 to 2) C: 2 (1.5 to 2.5) P=0.222

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I: Cephalexin 500 mg II: Clindamycin 300 mg

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Placebo |

Length of follow-up: 14 days Satisfaction 30 days

Loss-to-follow-up: Three patients were noncompliant and did not complete the medication course (4%; 95% CI, 1%-11%) but they were analyzed in the same groups that they were allocated to.

Incomplete outcome data: None.

|

Wound infection n/N (%, 95% CI)

Intervention: 0/49 (0%) Control: 1/24 (4.2%) Total: 1% (95% CI= 0.01 to 8%)

(minor) adverse events, n/N (%, 95% CI)

Intervention: 3/49 (6.1%) Control: 1/24 (4.2%) Total: 5% (95% CI= 2% to 13%)

(serious) adverse events, n/N (%, 95% CI)

No serious adverse events were reported.

Wound appearance satisfaction, median (IQR)

Total: 8 (9 to 10).

|

|

Altergott, 2008 |

Type of study: Prospective randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Urban children’s hospital emergency department, USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, and General Clinical Research Center Grant MO1 RR00046 and was performed at the General Clinical Research Center at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles. Computational assistance was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, and General Clinical Research Center Grant MO1 RR00046 and was performed at the General Clinical Research Center at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients aged <18 years; Patients presenting to the emergency department with a fingertip injury distal toe the distal interphalangeal joint.

Exclusion criteria: Time from injury to repair greater than 8 hours; Patients with diabetes; Patients with an immune deficiency; Patients with a bleeding disorder; Patients who used steroids regularly; Patients presenting with a grossly contaminated wound; Patients who were currently taking antibiotics; Patients who had pevious allergic reactions to cephalosporins.

N total at baseline: Intervention: N=66 Control: N=69

Important prognostic factors2: Mean (SD) age: I: 3.2 (2.9) C: 3.0 (2.5)

Sex, n/N (%): I: 34/66 (51.5%) M C: 43/69 (62.3%) M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided 3 times daily upon discharge for 7 days

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No antibiotics |

Length of follow-up: 7 days

Loss-to-follow-up: N=11 N=4 could not be reached for phone follow-up; N=3 received antibiotics during the study period for a reason other than infection of the fingertip; N=2 for whom insufficient data were available for analysis; N=1 received antibiotics for repair; N=1 requested to be withdrawn from the study before completion.

Subjects were equally distributed between the 2 groups: 6 (8%) of 75 from no-antibiotic group and 5 (7%) of 71 from antibiotic group (P = 1.0).

|

Wound infection, n/N (%)

At 7 days, a total of 7 patients had positive findings on phone follow-up (4 in the control group and 3 in the intervention group). These 7 patients returned to the emergency department for visual examination by one of the 3 primary investigators. One subject in each treatment group was found to have a true infection

Intervention: 1/66 (1.5%) Control: 1/69 ( 1.4%) Infection rate intervention= 1.52% (95% CI= 0.04$ to 8.16%) Infection rate control= 1.45% (95% CI= 0.04% to 7.81% P=1.000

After the completion of the study, chart review revealed 4 infections presenting beyond the 7-day window (days 7 to 14), 3 in the antibiotic group and 1 in the no-antibiotic group. Including these patients to the infected group brings the overall infection rate to 4.4%. Again, although the infection rate was lower in the group not treated with antibiotics (2.9% versus 6.1%), the difference was not statistically significant.

Intervention: 3/66 (4.5%) Control: 1/69 (1.4%) Overall infection rate= 4.4% |

Systematic review(s)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Zehtabchi, 2007 |

Yes

Does the use of prophylactic antibiotics after repair of uncomplicated hand lacerations lead to a reduced incidence of wound infection? |

Yes

The author searched the MEDLINE database with the OVID interface from 1966 to December 2005 and EMBASE from 1980 to December 2005, using search terms “wound,” “laceration,” “injury,” “hand,” “fingers,” “antibiotics,” “antibacterial agents,” and “prophylaxis.”. The MEDLINE search, but not other searches, was limited to randomized trials or systematic reviews using prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection in hand lacerations. The author also scanned the databases of the Cochrane Library through 2005, Emergency Medical Abstracts1 from 1977 through December 2005, and online resources including BestBETS, using the search words “hand laceration,” “hand wound,” and “antibiotic prophylaxis.” He reviewed the bibliographies of the eligible trials for citations of additional eligible studies.

|

Yes |

Yes

Table 1 summarizes the key features of the 4 trials. Two of the studies were conducted in EDs in the United States, and the other 29,10 were conducted in EDs in England. All 4 trials tested the use of prophylactic antibiotics for prevention of simple hand lacerations compared to a control group (placebo or no intervention). All excluded bite wounds and lacerations involving special structures, such as bone, nerve, large vessels, and tendons, and described a reasonable method of wound care (eg, irrigation and debridement) and closure technique (suturing) for all the study subjects |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Randomized controlled trials

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomization1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Berwald, 2014 |

Patients were randomized, using computer-generated block randomization, to 1 of 3 groups

|

Unlikely

|

Unlikely

Capsules were prepared by the research pharmacist and stored in coded bottles. All capsules were the same color and size. Investigators, subjects, and outcome assessors were blinded to the content of the capsules and bottles |

Unlikely

Capsules were prepared by the research pharmacist and stored in coded bottles. All capsules were the same color and size. Investigators, subjects, and outcome assessors were blinded to the content of the capsules and bottles |

Unlikely

Capsules were prepared by the research pharmacist and stored in coded bottles. All capsules were the same color and size. Investigators, subjects, and outcome assessors were blinded to the content of the capsules and bottles |

Unlikely

All predefined outcome measures were reported |

Unlikely

Three patients were noncompliant and did not complete the medication course (4%; 95% CI, 1%-11%) but they were analyzed in the same groups that they were allocated to.

|

Unlikely

Intention-to-treat analysis was observed during group comparisons

|

|

Halhalli, 2018 |

The patients were allocated in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive an oral 500 mg cephalexin monohydrate (Sef; Mustafa Nevzat İlaç San, İstanbul, Turkey) or topical pomade including 2% mupirocin (Bactroban; Glaxo Smith Kline, İstanbul, Turkey), or wound cleaning with antiseptic and dressing in a blinded fashion The randomization schedule was generated with http://www.randomization.com.

|

Unlikely

The randomization number generated by the responsible investigator using www.randomization.com was determined for the patient. The responsible investigator then telephoned the supervising nurse and relayed the patient’s randomization number

|

Unlikely

The senior emergency medical resident in charge of patient care and the emergency medical specialist in charge of the control examination were blinded to the implemented treatment; the statistician was also blinded to treatment allocation during statistical analyses. |

Unlikely

The senior emergency medical resident in charge of patient care and the emergency medical specialist in charge of the control examination were blinded to the implemented treatment; the statistician was also blinded to treatment allocation during statistical analyses. |

Unlikely

The senior emergency medical resident in charge of patient care and the emergency medical specialist in charge of the control examination were blinded to the implemented treatment; the statistician was also blinded to treatment allocation during statistical analyses. |

Unlikely

All predefined outcome measures were reported |

Unclear

37 patients did not come to the control examination.

Not further specified

|

Unlikely

An intention-to-treat analysis was performed to avoid overestimation of clinical effectiveness. All randomized patients were included in the statistical analysis regardless of the treatment implemented and regardless of the withdrawal status of the patient

|

|

Altergott, 2008 |

Participants were randomized to 1 of 2 groups using a randomization list prepared in advance with PROC PLAN within the Statistical Analysis System

|

Likely

Patient enrollment was at the discretion of the emergency department attending physician working at the time of repair. He or she may have been reluctant to enroll more complicated fingertip lacerations (ie, complete avulsions) or may have been too busy or distracted to enroll all eligible patients. |

Unclear

Blinding in relation to treatment allocation not described. |

Unclear

Blinding in relation to care providers not described. |

Likely

Follow-up was not blinded. This could have introduced bias in the reporting of infection

|

Unlikely

All predefined outcome measures were reported |

Unlikely

Eleven participants were withdrawn before study completion. Those not completing the study included 4 subjects who could not be reached for phone follow-up, 3 subjects who received antibiotics during the study period for a reason other than infection of the fingertip, 2 subjects for whom insufficient data were available for analysis, 1 subject who received antibiotics before repair, and 1 subject who requested to be withdrawn from the study before completion. These 11 subjects were significantly older than those who completed the study (6.0 T 3.8 years versus 3.1 T 2.7 years; P = 0.001) but were similar on all other baseline characteristics. In addition, subjects were equally distributed between the 2 groups: 6 (8%) of 75 from no-antibiotic group and 5 (7%) of 71 from antibiotic group (P = 1.0). |

Unlikely |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 31-05-2022

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met acute wonden.

Werkgroep

- Drs. M (Michiel) Schreve, chirurg, NVvH (voorzitter)

- Dr. M.E.N. (Maurice) Pierie, chirurg, NVvH

- Drs. S. (Stijn) Westerbos, orthopeed, NOV

- Dr. M.A.M. (Miriam) Loots, dermatoloog, NVDV

- Dr. F.E. (Fleur) Brölmann, plastisch chirurg, NVPC

- Drs. E. (Ellie) Lenselink, wondconsulent, V&VN

- Drs. K. (Katja) Reiding, huisarts, NHG

- Drs. L.F.J. (Lucas) Teeven, spoedeisende hulp arts i.o., NVSHA

- Dr. M.W.F. (Martin) van Leen, specialist ouderengeneeskunde, Verenso

- Prof. D. T. (Dirk) Ubbink, Hoogleraar Evidence-based medicine en shared decision-making

Meelezers

- Dr. A. (Adinda) Klijn, spoedeisende hulp arts, NVSHA

- Drs. C.J. (Christel) de Kuiper, verpleegkundig specialist wondmasters, V&VN

- Dr. A.T. (Sandra) Bernards, arts-microbioloog, NVMM

Met ondersteuning van

- Drs. M. (Mitchel) Griekspoor, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. W.J. (Wouter) Harmsen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. R. (Romy) Zwarts - van de Putte, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Schreve |

Vaatchirurg |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Pierie |

Vaatchirurg |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Westerbos |

Orthopeed |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Loots |

Dermatoloog |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Brölmann |

Plastisch chirurg |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Lenselink |

Wondconsulent |

Begeleider opleiding wondverpleegkundige, Bestuurslid V&VN, CZO opleidingscommissie, Lid stuurgroep wondopleidingen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Reiding |

Huisarts |

Lid commissie transmurale afspraken wondzorg voor de HOZK |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Teeven |

Spoedeisende hulp arts i.o., |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Leen |

Specialist ouderengeneeskunde |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Ubbink |

Arts en klinisch epidemioloog. Hoogleraar Evidence-based medicine en shared decision-making |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

De Kuiper |

Verpleegkundig specialist |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Bernards |

arts-microbioloog |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de Invitational conference. De Patiëntenfederatie Nederland is niet op deze uitnodiging ingegaan. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met acute wonden. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodules (2013) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een digitale Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.