Nazorg bij VKB-letsel (postoperatieve traject)

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het optimale postoperatieve traject van patiënten met voorste kruisbandletsel?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik geen brace in het postoperatieve traject na een VKB-reconstructie.

Combineer kracht- en neuromusculaire training in de postoperatieve behandeling.

Raad zwaar fysieke revalidatie belasting, pivoterende sport, knie belastend werk en risicoactiviteiten waarbij op de VKB-reconstructie vertrouwd moet kunnen worden, gedurende de eerste drie maanden af.

Overwegingen

Patiëntperspectief

Fysiotherapie is een vast onderdeel van de behandeling van patiënten met een voorste kruisbandletsel, zeker wanneer er een kruisbandreconstructie uitgevoerd wordt.

Er worden in de fysiotherapeutische behandelprogramma’s diverse modaliteiten onderscheiden. Enkele voorbeelden hiervan zijn krachttraining in open- en gesloten keten, neuromusculaire training, optimaliseren van de mobiliteit en pijnvermindering. In veel programma’s is er ook aandacht voor het verbeteren van de algehele conditie. De verschillende componenten krijgen niet bij elke therapeut en elke patiënt evenveel aandacht, de behandeling is op maat gesneden naar de mogelijkheden en behoeften van de patiënt (en behandelaar).

Professioneel perspectief

Zoals uit de literatuuranalyse blijkt is er in de afgelopen 7 jaren weinig nieuwe externe evidentie rondom de fysiotherapeutische behandeling toegevoegd. Er was en is beperkt hard wetenschappelijk bewijs voor de verschillende trainingsvormen waaruit de revalidatieprogramma’s zijn opgebouwd. Daartegenover staat de dagelijkse praktijk waarin reconstrueren zonder nabehandeling geen optie is.

In de nieuw gevonden literatuur, onder het kopje other modalities worden twee studies beschreven waarvan een studie Grant, (2010) een extensief programma (4 sessies) vergelijkt met een meer intensief programma (17 sessies). Op lange termijn is er geen verschil in effect. Door grote loss to follow up kunnen er echter geen harde uitspraken worden gedaan. Onder hetzelfde kopje is er een studie waarin groepstherapie vergeleken wordt met individueel begeleiding Revenas, (2009). Ook hier kan geen uitspraak worden gedaan omtrent verschil in effectiviteit.

Bracegebruik

Kinikli geven aan dat er een klein effect is van gebruik van braces op mechanische stabiliteit. Zij baseren zich hierbij op de studie van Moller. In de oorspronkelijke publicatie geven Moller aan dat het ogenschijnlijke verschil na interventie wordt veroorzaakt door baselineverschillen. Na correctie voor deze verschillen valt het effect weg. Derhalve concludeert men in de oorspronkelijke publicatie dat bracegebruik geen toegevoegde waarde heeft op mechanische stabiliteit. Er is dan ook geen reden om het ingenomen standpunt uit de richtlijn van 2011 over de meerwaarde van bracegebruik aan te passen

Pre-operatieve fysiotherapie is in de huidige vraag niet meegenomen. Dit betekent dat de aanbevelingen uit de vorige versie van de richtlijn met betrekking tot het preoperatief nastreven van een zo klein mogelijk krachtsverlies ten opzichte van de niet aangedane zijde en het nastreven van een volledige extensiemogelijkheid in de knie voor de operatie ook in deze richtlijnversie standhouden.

Organisatie van zorg

Communicatie tussen fysiotherapeut en behandelend medisch specialist (orthopedisch chirurg) is te allen tijde van belang.

Postoperatief zal de fysiotherapeut informatie nodig hebben over: de operatie, graft type, of er bijkomend een (partiële) meniscectomie of meniscushechting uitgevoerd is, of er sprake is van kraakbeenschade in de verschillende compartimenten (locatie, graad en grootte), of er een bone bruise aanwezig is, of er sprake is van ander ligamentair letsel, eventueel aangevuld met adviezen ten aanzien van belasting.

Voor diepgaandere informatie over de invulling en opbouw van de fysiotherapeutische

reactivatie kan het evidence statement “Revalidatie na voorste kruisbandreconstructie” geraadpleegd worden Van Melick, (2014).

In het evidence statement onderscheidt men 3 revalidatiefasen die niet tijdcontingent ingedeeld zijn. Doelstelling in fase 1 is het bereiken van een normaal functionerend ADL, met adequaat gangbeeld, een extensie van 0° en reduceren van hydrops/synovitis. Fase 2 richt zich op het klachtenvrij uitvoeren van sport specifieke activiteiten en zwaar werk. In fase 3 is volledige terugkeer naar sportactiviteiten en/of volledige participatie in fysiek zwaar werk de doelstelling.

Uit de literatuur komt onvoldoende informatie naar voren waarop met wetenschappelijke basis een voor iedere patiënt toepasbaar advies te geven is over werk/ADL en sport hervatting. Toch willen wij een globaal advies meegeven. Na een reconstructie volgt een biologisch proces van ingroei en adaptatie. Hierin bestaat per patiënt een natuurlijke variatie maar het is aannemelijk dat binnen een periode van 3 maanden postoperatief een hervatting van zwaar fysieke activiteiten in werk en of sport niet verantwoord is. Derhalve wil de commissie adviseren dat zwaar fysieke revalidatie belasting, rennen, kap en draai sport, knie belastend werk en risicoactiviteiten waarbij op de knie vertrouwd moet kunnen worden de eerste drie maanden worden ontraden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Physiotherapy (PT) treatment is important in pre-operative and post-operative management of patients with an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. A typical PT treatment programme consists of a combination of treatment modalities. Strength and neuromuscular training are important components.

Although physical therapy is commonly prescribed, evidence regarding overall use and use of different treatment modalities is scarce. Furthermore, methodological quality of studies on PT in ACL reconstruction is low, leading to potential bias. Seven years have passed since the publication of the first guideline, therefore a new review of the literature was conducted to gain insight into novel study data.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Post-operative bracing

Pain

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in pain after rehabilitation with brace compared with rehabilitation alone after ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Kinikli, 2014; Mayr, 2014) |

Muscle strength

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in muscle strength after rehabilitation with brace compared with rehabilitation alone after ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Kinikli, 2014; Mayr, 2014) |

Stability

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be a small effect on mechanical stability of bracing compared with non-bracing after ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Kinikli, 2014; Mayr, 2014) |

Return to work/sport and PROMs

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn on return to work/return to sport and PROMs for rehabilitation with brace after ACL reconstruction due to lack of data. |

Modalities of physiotherapy

Return to work/sport and pain

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in return to work and pain after neuromuscular training compared to conventional rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Kruse, 2012) |

PROMs

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in PROMs after neuromuscular training compared to conventional rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Kruse, 2012; Fu, 2013) |

Muscle strength

|

Very low GRADE |

There is inconsistent evidence about the effect of neuromuscular training on the outcome muscle strength after ACL reconstruction,

Sources (Kruse, 2012; Berschin, 2014; Costantino, 2017; Fu, 2013) |

Stability

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in stability after whole-body vibration compared to conventional rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Berschin, 2014; Fu, 2013) |

Kinetic chain strength exercises

PROMs

|

Low GRADE |

Patients undergoing a rehabilitation programme with closed kinetic chain exercises seem to have a better Lysholm score compared to those undergoing an open kinetic chain exercise programme after ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Ucar, 2014) |

Pain

|

Low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in pain after closed kinetic chain exercises compared to open kinetic chain exercise after ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Ucar, 2014) |

Return to work/return to sport, muscle strength and stability

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn on return to work/return to sport, muscle strength and stability for closed kinetic chain exercises after ACL reconstruction due to lack of data. |

Other modalities

Return to work/return to sport, PROMs, pain, muscle strength and stability

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn on return to work/return to sport, PROMs, pain, muscle strength and stability for other physiotherapy modalities after ACL reconstruction due to lack of data. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description studies

Post-operative bracing

Post-operative bracing is designed to limit or improve range of motion and to protect against varus and valgus stress. Post-operative bracing was included in the review by Kruse (2012). A more recent systematic review was published by Kinikli in 2014, which reported quantitative data of outcomes in contrast to Kruse who did not report quantitative data. Therefore, the systematic review of Kinikli was used to describe the effect of post-operative bracing. An additional RCT was included, published after Kinikli Mayr, (2014).

Kinikli (2014) performed a systematic review into the effectiveness of post-operative knee bracing on knee laxity, muscle strength, knee functional status, range of movement, pain and complications after ACL reconstruction. Authors systematically searched the AMED, CINAHL Plus, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, MEDLINE (via OVID) and Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) up to May 2012 for RCTs and quasi-randomised controlled trials that evaluated the effects of bracing as part of rehabilitation of ACL reconstruction. Methodological quality was assessed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database Scale (PEDro Score, range 0 to 10, whereby 10 is highest quality). Eleven RCTs were included. The number of patients ranged from 40 to 82 patients and the follow-up from two weeks to two years. Only the RCTs (n=7) were included in our literature analysis.

Mayr performed an RCT in 52 patients with acute ACL injury. A total of 27 patients were randomised to the brace group receiving a pre-fabricated knee-stabilising brace in addition to a pre-defined programme of rehabilitation and 25 patients to the rehabilitation programme only. The follow-up time was four years.

Modalities of physiotherapy

Kruse (2012) performed a systematic review on the effectiveness of rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction. The review focussed on Level I or II evidence, published since previous systematic reviews (till 2006). Authors systematically searched PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register from January 2006 to December 2010. High-quality RCTs were included as Level I studies and lesser-quality RCTs and prospective comparative studies as Level II studies. Case-control studies, retrospective comparative studies, and case series were excluded. A total of 29 level I or II studies were included for the topics: post-operative bracing, accelerated strengthening, home-based rehabilitation, proprioception and neuromuscular training and six miscellaneous topics investigated in single trials. Methodological quality was assessed by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist. However, results of the quality assessment were not reported in the article. Furthermore, outcomes were only described, and no quantitative data of outcomes were reported.

Neuromuscular Training

Kruse (2012) included eight RCTs about neuromuscular training. The intervention included proprioceptive and balance training, perturbation training and vibratory stimulation. The number of patients included in these studies ranged from 19 to 74. Outcomes were return to sport, IKDC, pain and muscle strength. No quantitative data of these outcomes was reported.

Additionally, three RCTs were included, evaluating the effect of whole-body vibration (Costantino, 2017; Berschin, 2014; Fu, 2013).

Costantino (2017) performed an RCT in 38 female athletes with a rupture of the ACL. Nineteen patients (mean age 25.5±2.0 yr) were randomised to the intervention group receiving a conventional rehabilitation programme plus whole-body vibration exercises and 20 patients (mean age 25.4±2.4 yr) to the conventional rehabilitation program only. The follow-up time was 20 weeks.

Berschin (2014) performed an RCT in 40 ACL patients. Twenty patients (age not reported) were randomised to the whole-body vibration exercise group and 20 patients to the control group receiving standard rehabilitation and muscle strength exercises. The follow-up time was eleven weeks.

Fu (2013) performed an RCT in 48 ACL patients. A total of 24 patients (mean age 25.2±7.3 yr) were randomised to the whole-body vibration exercise group and 24 patients (mean age 23.3±5.2 yr) to the control group following the conventional rehabilitation protocol only. The follow-up time was six months.

Kinetic chain strength exercises

Ucar (2014) performed an RCT in 58 patients having ACL reconstruction surgery. Thirty patients (mean age 27.4±10.5 yr) were randomised to the intervention group receiving closed kinetic chain exercises and 28 patients (mean age 28.1±11.9 yr) were randomised to the control group receiving open kinetic chain exercises. The follow-up time was six months.

Other modalities

Kruse (2012) included two RCTs evaluating the effects of other modalities (Grant, 2010; Revenas, 2009). In the study of Grant (2010), home-based rehabilitation with minimal therapist involvement (4 sessions) was compared to extensive physical therapist-guided rehabilitation (17 sessions). A total of 129 patients were included and followed for four years. In the RCT of Revenas (2009), a knee therapy class was compared to individual physical therapy appointments beginning six weeks after surgery. Both groups performed the same open and closed kinetic-chain exercises with progressive increases in weight. A total of 51 patients were included and followed for twelve months. The authors stated that due to performance bias (a wide range of compliance and a low threshold to be considered compliant) and attrition bias, the results of the study of Revenas must be interpreted with caution.

Results

Post-operative bracing

1. Return to work/ return to sport

Kinikli (2014) reported no data on return to work/sport.

2. PROMs

Kinikli (2014) reported no data on PROMs.

In the RCT of Mayr (2014), IKDC, Tegner and Lysholm were assessed. No statistically significant differences were found for these outcomes.

3. Pain

Five studies included in the review of Kinikli (2014) reported data on pain, assessed with visual analogue scales. None of these studies reported statistically significant differences between the brace and non-brace groups at the end of follow-up. No meta-analysis was performed.

In the RCT by Mayr (2014), a statistically significant difference was found in pain assessed with VAS (range 0 to 10) between the 2 groups after 4-yr follow-up (I: 0.3 (SD 0.7) to 1.9 (SD 1.4); C: 0.2 (SD 0.7) to 1.0 (SD 1.2); P=0.015).

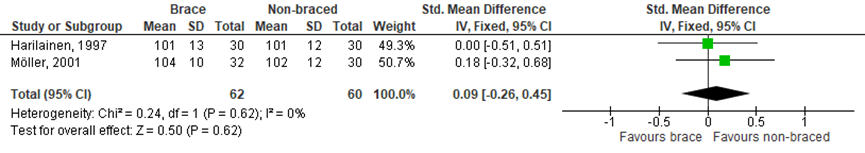

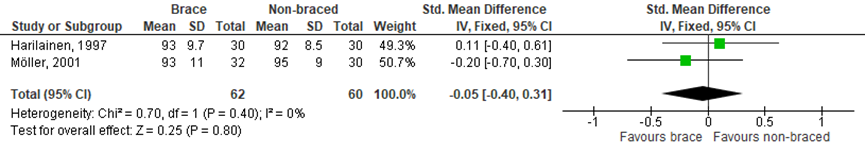

4. Muscle strength

In the SR of Kinikli muscle strength was assessed in five of the seven included RCTs. Only two of these studies had sufficient and comparable data to allow meta-analysis (Figure 1 and 2). There was no statistically significant effect on muscle strength, for both isokinetic knee flexion muscle strength measured at 180°/s (SMD 0.09; 95% CI -0.26 to 0.45) and knee extensor strength at 180°/s (SMD -0.05; 95% CI -0.40 to 0.31).

Figure 1 Meta-analysis brace versua non-braced of the outcome isokinetic knee flexion muscle strength

Figure 2 Meta-analysis brace versus non-braced of the outcome isokinetic knee extension muscle strength

In the RCT by Papandreou, quadriceps muscle strength was measured for the injured and uninjured leg. There was no statistically significant difference after nine weeks between the two intervention groups and the control group in mean percentage change in quadriceps strength for the injured leg (Intervention 1: 22.7% (SD 20.6); Intervention 2: 18.0% (SD 17.6); Control: 14.1% (SD 16.2).

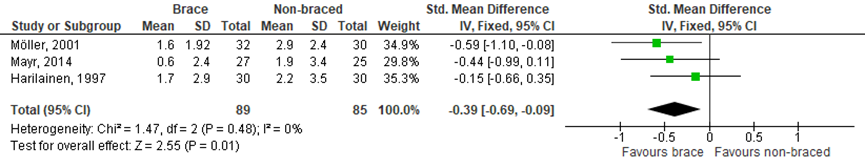

5. Stability

In the SR of Kinikli (2014), knee laxity was assessed in six of the seven included RCTs. A variety of instrumented laxity tests was used, four studies used a KT-1000 arthrometer, one study a KT-2000 arthrometer, one study an instrumented laxity test and one study a CA 4000 instrumented laxity tester. Only two studies, using the KT-1000, had sufficient and comparable data to allow meta-analysis. Additionally, the RCT by Mayr (2014) was added to the meta-analysis (Figure 3). There was a statistically significant moderate effect on knee laxity favouring brace (SMD -0.39 95% CI -0.69 to -0.09), but this overall positive effect of bracing on improved knee laxity is created by only one study Möller, (2001).

Figure 3 Meta-analysis brace versus non-braced of the outcome stability.

Level of evidence

Return to work/ return to sport: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for return to work/ sport could not be graded.

PROMs: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for PROMs could not be graded.

Pain: The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method for subjects and therapists), inconsistency (large heterogeneity) and imprecision (too few patients).

Muscle strength: The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method for subjects and therapists), indirectness (difference in outcomes) and imprecision (too few patients).

Stability: The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method for subjects and therapists), indirectness (difference in outcomes) and imprecision (too few patients).

Modalities of physiotherapy

Neuromuscular Training

1. Return to work/ sport

One RCT Hartigan, (2010) included in Kruse (2012) reported return-to-sport as outcome variable. It was stated that there were no differences between the groups in the percentage patients meeting return-to-sport criteria.

2. PROMs

One RCT Brunetti, (2006) included in Kruse (2012) reported IKDC as outcome variable. No difference was found in IKDC between a group receiving vibratory treatment and a control group in the study by Brunetti.

One RCT (Risberg, 2009 and 2007) included in Kruse (2012) reported the Cincinnati knee score as outcome variable. The neuromuscular training group had better Cincinnati knee scores at six months (I: 80.5 (SD 12.3); C: 73.4 (SD 9.6); P<0.05), but after one year (I: 85.8 (SD 11.5); C: 80.6 (SD 12.5); P=0.58) and two year follow-up (I: 88.7 (SD 10.6); C: 85.2 (SD 10.8); P>0.05) there was no statistically significant difference.

In the RCT by Fu (2013), there was no statistically significant difference after six months between the whole-body vibration group and the control group in Lachman test (Z=0.37; P=0.71) and pivot shift test (Z=-1.56; P=0.12).

3. Pain

Two RCTs (Risberg, 2009 and 2007; Benazzo, 2008) included in Kruse (2012) reported pain as outcome variable, defined by VAS pain. The neuromuscular training group had a better VAS pain score after one-year follow-up (I: 81.8 (SD 19.6); C: 65.2 (SD 28.8); P<0.05), but there was no difference at two-year follow-up (I: 82.0 (SD 23.4); C: 71.8 (SD 25.3); P=0.09). The results of the study by Benazzo on pain were not reported.

4. Muscle strength

Two RCTs (Risberg, 2009 and 2007; Hartigan, 2010) included in Kruse (2012) reported muscle strength as outcome variable. The two-year follow-up results were extracted from the original publication. The mean percentage knee flexion total work 240 deg/s was 91.5 (SD 18.9) in the neuromuscular training group and 103.9 (SD 13.4) in the strength exercise (control) group, with a mean difference of 12.4 (P=0.003). The mean percentage knee extension total work 240 deg/s was 90.1 (SD 13.9) in the neuromuscular training group and 88.5 (SD 14.1) in the strength exercise (control) group, with a mean difference of -1.6 (P=0.64). There was no difference between the groups in 60 deg/s. The review by Kruse et al. stated that there was no difference in quadriceps strength gain between the groups in the study by Hartigan (2010).

In the RCT by Berschin (2014), there was only a statistically significant difference between groups after eleven weeks in isometric quadriceps strength ratio. The mean percentage isometric quadriceps ratio was 64 (SD 9) in the whole-body vibration exercise group and 70 (SD 3) in the standard rehabilitation group, with a mean difference of 6 (P=0.007). There was no difference between the groups for the other muscle strength outcomes (isokinetic hamstring ratio, isokinetic quadriceps ratio and isometric hamstring ratio).

In the RCT by Costantino (2017), there were statistically significant differences between the whole-body vibration group and the conventional rehabilitation group in isokinetic knee extension strength at maximum power (mean difference -13.7; 95% CI -19.3 to -8.2; P<0.001) and isokinetic knee flexion strength at maximum power (mean difference -10.1; 95% CI -11.6 to -8.6; P<0.001) favouring whole-body vibration.

In the RCT by Fu (2013), there were no differences in isokinetic hamstring peak torques at speeds of 180 and 300 °/sec after 6 months between the group receiving whole-body vibration and the control group following a conventional rehabilitation protocol.

5. Stability

Kruse (2012) reported no data on stability.

In the RCT of Berschin (2014), the whole-body vibration group had better stability after 11 weeks measured by the stability index (range 0 to 10), compared to the control group (mean difference 1.60; 95% CI 0.20 to 3.00; P=0.03).

In the RCT by Fu (2013), there was no statistically significant difference after six months between the whole-body vibration group and the control group in the overall stability index, with eyes open (mean difference 0.47; 95% CI -0.15 to 1.09; P=0.13) and closed (mean difference 0.37; P=0.56).

Level of evidence

For the outcomes return to sport, PROMs, pain and stability the level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (limited blinding of subjects and therapists), inconsistency (large heterogeneity) and imprecision (too few patients).

Muscle strength: The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (limited blinding of subjects and therapists), indirectness (large heter

Kinetic chain strength exercises

1. Return to work/ sport

Ucar (2014) reported no data on return to work or sport.

2. PROMs

In the RCT by Ucar (2014) there was a statistically significant difference in Lysholm score after 6 months between the closed kinetic chain exercise group and the open kinetic chain exercise group (mean difference -9.8; 95% CI -14.4 to -5.2; P=0.0001), meaning that the closed kinetic chain group had significant improvement in Lysholm score after 6 months compared to the open kinetic chain group.

3. Pain

In the RCT by Ucar (2014) there was a trend for the closed kinetic chain exercise group in more reduction of pain after 6 months, measured with VAS 100, compared to the open kinetic chain exercise group, but the difference was not statistically significant different (mean difference 5.1; 95% CI -0.3 to 10.5; P=0.06).

4. Muscle strength

Ucar (2014) reported no data on muscle strength.

5. Stability

Ucar (2014) reported no data on stability.

Level of evidence

Return to work/ return to sport: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for return to work/ sport could not be graded.

PROMs: The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (limited blinding of subjects and therapists) and imprecision (too few patients).

Pain: The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (limited blinding of subjects and therapists) and imprecision (too few patients).

Muscle strength: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for muscle strength could not be graded.

Stability: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for stability could not be graded.

ogeneity in interventions and outcomes) and imprecision (too few patients).

Other modalities

1. Return to work/ sport

Kruse reported no data on return to work/sport.

2. PROMs

Two RCTs (Grant, 2010; Revenas, 2009) included in Kruse (2012) reported IKDC as an outcome variable. In both studies, no difference was found in IKDC between home-based rehabilitation and outpatient physical therapy after ACL reconstruction. In the study by Revenas, the Lysholm score was also evaluated. No difference was found in Lysholm score after 12 months.

3. Pain

Kruse reported no data on pain.

4. Muscle strength

Two RCTs (Grant, 2010; Revenas, 2009) included in Kruse (2012) reported muscle strength as an outcome variable. In the study by Grant, no difference was found in isokinetic hamstring and quadriceps tests after 4 years. In the study by Revenas, no difference was found in isometric strength after 12 months.

5. Stability

One RCT Grant, (2010) included in Kruse (2012) reported laxity as an outcome variable, defined with the KT-1000. No difference was found between the two groups, but no quantitative data was reported.

Level of evidence

Return to work/ return to sport: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for return to work/ sport could not be graded.

PROMs: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for PROMs could not be graded.

Pain: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for pain could not be graded.

Muscle strength: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for muscle strength could not be graded.

Stability: Because of insufficient data the level of evidence for stability could not be graded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of rehabilitation of patients treated for ACL injury compared to control therapy?

P: patients treated for ACL injury;

I: revalidation/rehabilitation: exercise, physiotherapy, bracing;

C: control therapy;

O: return to work, return to sport, PROMs (IKDC, KOOS) pain, muscle strength, stability.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered all outcome measures important for decision-making.

The working group did not define the outcome measures a priori, but applied the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined MCID 2.2 and 8.0 as a clinical patient relevant difference for KOOS-PS and KOOS-QOL Singh, (2014) and MCID between 9.9 and 20 mm as a clinical patient-relevant difference for VAS pain score (Myles, 2017; van der Wees, 2017).

Search and select (Method)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Cinahl were searched with relevant search terms. For the update of the literature, both databases were searched from the previous search date (December 2009) till August 2017. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The updated systematic literature search resulted in 243 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review with evidence tables, risk of bias evaluation and a detailed search strategy.

- Prospective randomised controlled trials of patients with ACL injury evaluating the effect of post-operative revalidation on return to work, return to sport, PROMs, pain, muscle strength, or stability.

Due to the heterogeneity of rehabilitation programmes and comparison therapies, the working group decided to exclude the following rehabilitation types, because they are considered part of a therapy or no physical therapy at all: accelerated strengthening, dry needling, kinesio taping, cryotherapy, perturbation training, treadmill training, glucosamine, dosing of training, timing of training, biofeedback and electrostimulation, comparison of braces.

Initially, 49 studies were selected based on title and abstract by one or both reviewers. After reading the full text, 38 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 11 studies were included.

Eleven studies were included in the literature analysis: 2 systematic reviews and 9 RCTs. Important study characteristics and results are depicted in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is depicted in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Berschin G, Sommer B, Behrens A, et al. Whole Body Vibration Exercise Protocol versus a Standard Exercise Protocol after ACL Reconstruction: A Clinical Randomized Controlled Trial with Short Term Follow-Up. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13(3):580-9.

- Costantino C, Bertuletti S, Romiti D. Efficacy of Whole-Body Vibration Board Training on Strength in Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Randomized Controlled Study. Clin J Sport Med. 2017;22:22.

- Fu CLA, Yung SHP, Law KYB, et al. The Effect of Early Whole-Body Vibration Therapy on Neuromuscular Control After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):804-14.

- Kim KM, Croy T, Hertel J, et al. Effects of neuromuscular electrical stimulation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on quadriceps strength, function, and patient-oriented outcomes: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(7):383-91.

- Kinikli GI, Callaghan MJ, Parkes MJ,et al. Bracing After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Turkiye Klinikleri Spor Bilimleri. 2014;6(1):28-38.

- Kruse LM, Gray B, Wright RW. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(19):1737-48.

- Mayr HO, Stueken P, Munch EO, et al. Brace or no-brace after ACL graft? Four-year results of a prospective clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(5):1156-62.

- Papandreou M, Billis E, Papathanasiou G, et al. Cross-exercise on quadriceps deficit after ACL reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2013;26(1):51-8.

- Risberg MA, Holm I. The long-term effect of 2 postoperative rehabilitation programs after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled clinical trial with 2 years of follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):1958-66.

- Ucar M, Koca I, Eroglu M, et al. Evaluation of open and closed kinetic chain exercises in rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26(12):1875-8.

- Van Melick N, Hullegie W, Brooijmans FA, et al. KNGF Evidence Statement revalidatie na voorste kruisbandreconstructie 2014

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

|

Postoperative bracing |

||||||||

|

Kinikli, 2014 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to May 2012

A: Harilainen, 1997 B: Brandsson, 2001 C: Feller, 1997 D: Möller, 2001 E: Muellner, 1988 F: Risberg, 1999 G: Hiemstra, 2009

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: not reported

Source of funding: (commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship)

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

11 studies included, from which 7 RCT’s

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N A: 60 patients, XX yrs B: 50 patients C: 40 patients D: 62 patients E: 40 patients F: 60 patients G: 82 patients

Age and sex not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

A: brace for 12 weeks B: brace for 6 weeks C:hinged passive extension brace D: brace for 6 weeks E: hinged brace at 0° and increased progressively F: rehabilitation brace for 2 weeks; functional 10 weeks G: soft, unhinged tripanel knee immobilizer with Velcro straps

|

A: no brace B: no brace C: no brace D: no brace E: neoprene sleeve for 6 weeks F: no brace G: no brace

|

A: 2 yr B: 24 months C: 4 months D: 2 years E: 52 weeks F: 24 months G: 14 days

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

|

1. Return to work/ sport Not reported.

2. PROMS No quantitative data reported.

3. Pain D, F, G: no difference (NS) B: brace mean VAS 2.3 (range 0 to 9) / non-brace VAS 1.0 (range 0 to 7) <2 weeks, but NS after 2 weeks.

4. Muscle strength Defined as isokinetic knee flexion strength ratio (%), MD (95% CI) A: 0.00 (-0.51 to 0.51) D: 0.18 (-0.32 to 0.68)

Pooled MD: 0.09 (-0.26 to 0.45) favouring non-braced Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Defined as isokinetic knee extension strength ratio (%), MD (95% CI) A: 0.11 (-0.40 to 0.61) D: -0.20 (-0.70 to 0.30)

Pooled MD: -0.05 (-0.40 to 0.31) favouring brace Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

5. Stability Defined as knee laxity, MD (95% CI) A: -0.15 (-0.66 to 0.35) D: -0.59 (-1.10 to -0.08)

Pooled MD: -0.37 (-0.73 to -0.01) favouring brace Heterogeneity (I2): 30% |

No quantitative data reported for PROMS (functional outcomes) and pain.

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained (subgroupanalysis) |

|

|

Modalities of physiotherapy |

||||||||

|

Kruse, 2012 |

SR of RCTs

Literature search from January 2006 up to December 2010

Neuromuscular Training A: Risberg, 2009/2007 B: Brunetti, 2006 C: Moezy, 2008 D: Benazzo, 2008 E: Cooper, 2005 F: Vathrakokilis, 2008 G: Hartigan, 2009 H: Hartigan, 2010

Accelerated strengthening I: Gerber, 2007a J: Gerber, 2007b/2009 K: Shaw, 2005 L: Sekir, 2010 M: Vadalà, 2007

Home-based rehabilitation N: Grant, 2010 O: Revenas, 2009

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: not reported

Source of funding: Non-commercial

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

29 studies included Neuromuscular training: 9 studies Accelerated strengthening: 5 studies Home-based rehabilitation: 2 studies

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N A: 74 patients B: 30 patients C: 23 patients D: 69 patients E: 29 patients F: 24 patients G: 19 patients H: 40 patients I: 32 patients J: 40 patients K: 103 patients L: 48 patients M: 45 patients N: 129 patients O: 51 patients

Age and sex not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

A: 6 months neuromuscular training B: vibratory C: WBVT D: PEMF E: 6 weeks proprioceptive/ balance training F: 8 weeks of balance training G: perturbation training H: perturbation training I: Eccentric strengthening J: Eccentric strengthening K: Strengthening immediately L: Isokinetic hamstring strengthening at 3 weeks M: Accelerated rehabilitation N: home-based rehabilitation with minimal therapist involvement (4 sessions) O: knee therapy class, open and closed-kinetic-chain exercises with progressive increases in weight.

|

A: strength training B: placebo treatment C: conventional therapy D: placebo E: strength training F: traditional rehabilitation G: strength training H: strength training I: Gerber, 2007 J: Gerber, 2007/2009 K: Strengthening at 2 weeks L: Isokinetic hamstring strengthening at 9 weeks M: Standard rehabilitation N: physical therapist-guided rehabilitation (17 sessions) O: Individual physical therapy appointments of open and closed-kinetic-chain exercises with progressive increases in weight, 6 weeks after surgery

|

A: 2 yr B: 270 days C: 12 weeks D: 24 months E: 6 weeks F: 8 weeks G: 6 months H: 12 months I: 14 weeks J: 1 yr K: 6 months L: 1 yr M: 10 months N: 4 yr O: 12 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? A: 14 (19%) N: 41 (32%) |

1. Return to work/ sport H: NS, no data reported

2. PROMS Defined by IKDC B: NS, no data reported D: no data reported L: NS, no data reported N: NS, no data reported O: NS, no data reported

Defined by Lysholm score O: NS, no data reported

3. Pain Defined by VAS pain A: I: 81.8; C: 65.2; P<0.05 at 1 yr I: NS after 2 yr D: no data reported I: NS, no data reported

4. Muscle strength Defined as isokinetic knee extension strength A: higher favoring strength training, no quantitative data reported K: NS, no data reported

Defined as quadriceps strength H: NS, no data reported I: increased favoring early eccentric group (P<0.01) N: NS, no data reported

Defined as isokinetic hamstring strength L: increased favoring early eccentric group (P<0.05) N: NS, no data reported

Defined as isometric strength O: NS, no data reported

5. Stability Laxity defined by KT-100 H: NS, no data reported K: NS, no data reported N: NS, no data reported |

Author’s conclusion: Neuromuscular interventions are unlikely to be harmful. Additionally, they are unlikely to make large improvements in outcomes or to help patients return to sports faster. Neuromuscular training may provide small benefits but should not be performed to the exclusion of strengthening and knee range of-motion exercises. Vibration training may lead to faster and more complete proprioceptive recovery, but further evidence is needed.

No quantitative data of outcome measures reported. No meta-analysis was performed.

|

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Berschin, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: patients who underwent ACL reconstruction

Country: Germany

Source of funding: not reported |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 20 Control: 20

Sex: I: 70% M C: 75% M

Other factors not reported |

Following exercise protocol from week 2 to 11 after surgery. Isometric exercise on WBV-platform with vibration frequency of 10 to 15Hz for one minute (2-6 series)

|

Standard rehabilitation and muscle strength exercises.

|

Length of follow-up: 11 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: 0

Incomplete outcome data: 0

|

1. Return to work/ sport Not reported.

2. PROMS Defined with Lysholm, mean (SD) at 11 weeks I: 85 C: 87 No difference between groups

3. Pain Not reported

4. Muscle strength Defined as 11-wk isokinetic hamstring ratio strength, mean % (SD) I: 76 (11) C: 72 (11) MD: -4 (95% CI: -11.0 to 3.0) P=0.25

Defined as 11-wk isokinetic quadriceps ratio strength, mean % (SD) I: 67 (18) C: 62 (18) MD: -5 (95% CI: -16.5 to 6.5) P=0.39

Defined as 11-wk isometric hamstring ratio strength, mean % (SD) I: 77 (17) C: 75 (17) MD: -2 (95% CI: -12.9 to 8.9) P=0.71

Defined as 11-wk isometric quadriceps ratio strength, mean % (SD) I: 64 (9) C: 70 (3) MD: 6 (95% CI: 1.7 to 10.3) P=0.007

5. Stability Defined by 11-weeks stability index (range 0-10), mean (SD) I: 3.1 (1.3) C: 4.7 (2.8) MD: 1.6 (95% CI: 0.20 to 3.00) P=0.03 |

|

|

Costantino, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: female volleyball/basketball players after ACL reconstruction

Country: Italy

Source of funding: not reported |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 19 Control: 20

Age ± SD: I: 25.5±2.0 C: 25.4±2.4

Sex: 100% female

Groups comparable at baseline? yes

|

Whole body vibration platform for 8 weeks at the beginning of week 13, 3 sessions per week, additional to conventional rehabilitation program. The rehabilitation protocol consisted of strength training exercises of lower limb muscles, joint and muscle flexibility exercises, balance, proprioceptive, and coordination training.

|

Conventional rehabilitation protocol, consisting of strength training exercises of lower limb muscles, joint and muscle flexibility exercises, balance, proprioceptive, and coordination training.

|

Length of follow-up: 20 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: 0

Incomplete outcome data: 0

|

1. Return to work/ sport Not reported.

2. PROMS Not reported

3. Pain Not reported

4. Muscle strength Defined as isokinetic knee extension strength, maximum power I: 149.2 (8.8) C: 135.5 (8.3) MD: -13.7 (95% CI: -19.3 to -8.2) P<0.0001

Defined as isokinetic knee flexion strength, maximum power I: 71.2 (2.4) C: 61.1 (2.2) MD: -10.1 (95% CI: -11.6 to --8.6) P<0.001

5. Stability Not reported |

Only women included in study. |

|

Fu, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: patients who underwent ACL reconstruction

Country: China

Source of funding: not reported |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 24 Control: 24

Age ± SD: I: 25.2 ± 7.3 yr C: 23.3 ± 5.2 yr

Sex: I: 58% M C: 75% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Whole body vibration therapy training starting 1 months after surgery in addition to conventional rehabilitation protocol. 2 sessions per week for a total of 16 sessions. Vibration frequencies ranged from 20 to 60 Hz.

|

Conventional rehabilitation protocol

|

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 5 (21%) Reasons: did not complete sessions, not enough time to attend.

Control: 4 (17%) Reasons: not enough time to attend.

|

1. Return to work/ sport Not reported.

2. PROMS Defined with Lachman test Z-score = 0.374 P=0.71

Defined with Pivot shift Z-score = -1.561 P=0.12

3. Pain Not reported

4. Muscle strength Defined as 6-months isokinetic quadriceps peak torques, mean % (SD) 180°/sec: I: 98.9 (22.4) C: 90.0 (22.2) MD: -8.9 (95% CI: -23.4 to 5.6) P=0.22

300°/sec: I: 65.5 (15.7) C: 56.8 (22.9) MD: -8.7 (95% CI: -21.5 to 4.1) P=0.18

Defined as 6-months isokinetic hamstring peak torques, mean % (SD) 180°/sec: I: 71.6 (16.2) C: 66.5 (21.0) MD: -5.1 (95% CI: -17.3 to 7.1) P=0.40

300°/sec: I: 58.6 (18.0) C: 51.5 (13.9) MD: -7.1 (95% CI: -17.5 to 3.3) P=0.18

5. Stability Defined by 6-month overall stability index, mean (SD) With eyes open I: 1.62 (1.00) C: 2.09 (0.90) MD: 0.47 (95% CI: -0.15 to 1.09) P=0.13

With eyes closed I: 5.20 (2.30) C: 5.57 (1.53) MD: 0.37 (95% CI: -0.89 to 1.63) P=0.56 |

|

|

Mayr, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: patients after ACL reconstruction with an ipsilateral patellar tendon autograft

Country: Germany

Source of funding: not reported |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 52 Intervention: 27 Control: 25

age ± SD: I: 40 ± 11 yr C: 35 ± 8 yr

Sex: I: 70% M C: 88% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported

|

Brace: 6 weeks treatment protocol and adjustable frame knee brace with a four-point fixation, for 24 h a day for the first 2 weeks after reconstruction. Thereafter, it could be removed at night and for physiotherapy

|

6 weeks treatment protocol, but no brace.

|

Length of follow-up: 4 yr

Loss-to-follow-up: 12 Groups and reasons not reported

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

1. Return to work/ sport Not reported.

2. PROMS Defined with IKDC, mean (SD) I: 66.6 (12.4) to 90.5 (9.0) C: 72.4 (13.2) to 93.3 (6.1) No difference between groups

Defined with Tegner, mean (range) at 4 yr I: 5 (range 4-8) C: 5 (range 4-8) No difference between groups

Defined with Lysholm, mean (SD) at 4 yr I: 87.4 (12.7) C: 92.2 (8.5) No difference between groups

3. Pain Defined with VAS range 0-10, mean (SD) I: 0.3 (0.7) to 1.9 (1.4) C: 0.2 (0.7) to 1.0 (1.2) P= 0.015

4. Muscle strength Not reported

5. Stability Measured with KT-1000, mean (SD) I: 5.2 (3.3) to 0.6 (2.4) C: 5.0 (3.1) to 1.9 (3.4) No difference between groups |

|

|

Papandreou, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: male patients soldiers in Greek army with unilateral ACL ruptures

Country: Greece

Source of funding: not reported |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

laxity or symptomatic meniscal injuries

cartilage lesions affecting the subchondral bone, fractures,

N total at baseline: Intervention 1: 14 Intervention 2: 14 Control: 14

Age ± SD: I1: 23.6±2.6 I2: 25.1±2.4 C: 23.1±2.7

Sex: 100% male

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

ACL rehabilitation program, starting 1 week after reconstruction for 8 weeks, 5 times a week. Wear functional brace for 6 weeks during daily activities. + Cross training (eccentric exercise program). Frequency: Group 1: 3 days per week Group 2: 5 days per week

|

Only the ACL rehabilitation program

|

Length of follow-up: 9 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: not reported

|

1. Return to work/ sport Not reported.

2. PROMS Not reported.

3. Pain Not reported.

4. Muscle strength Defined as quadriceps strength injured leg, mean % difference (SD) I1: 22.7 (20.6) I2: 18.0 (17.6) C: 14.1 (16.2)

5. Stability Not reported.

|

A significant difference was found for quadriceps muscle strength deficit ((preoperative QS: injured - uninjured) – (postoperative QS: injured - uninjured) /100), but not for strength in injured leg alone. |

|

Ucar, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: patients with unilateral ACL tears who underwent arthroscopically assisted ACLR

Country: Turkey

Source of funding: non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control: 28

Age ± SD: I: 27.4±10.5 C: 28.1±11.9

Sex: I: 80% M C: 82% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

Rehabiliation program, with closed kinetic chain exercises:

|

Rehabiliation program with open kinetic chain exercises, with:

|

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 3 (9%) Reason: not attending control visits

Control: 3 (11%) Reason: not attending control visits

|

1. Return to work/ sport Not reported.

2. PROMS Defined with Lysholm, mean (SD) at 6 months I: 94.1 (8.5) C: 84.3 (9.1) MD=-9.8 (95% CI -14.4 to -5.2) P=0.0001

3. Pain Defined with VAS 100 (mm), mean (SD) at 6 months I: 22.1 (10.5) C: 27.2 (9.9) MD=5.1 (95% CI -0.3 to 10.5) P=0.06

4. Muscle strength Not reported.

5. Stability Not reported.

|

CKC: closed kinetic chain; OKC: open kinetic chain

|

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Kinikli, |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

NA |

Yes |

No (only 2 studies included in meta-analyses) |

No |

No |

|

Kruse, 2012 |

Yes |

No (Medline not searched) |

No |

No |

NA |

Unclear (quality assessed, but not reported) |

Unclear |

No |

No |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Berschin, 2014 |

Randomisation using computer generated numbers, stratified on sex |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear. No mention of a trial register. However, outcomes stated in the methods section were reported in the results section. |

Unlikely, no loss to follow-up |

Unlikely |

|

Costantino, 2017 |

Randomisation using computer randomization software. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely, no blinding possible but participants did not know how treatment was performed in other group. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear. No mention of a trial register. However, outcomes stated in the methods section were reported in the results section. |

Unlikely, no loss to follow-up |

Unlikely |

|

Fu, 2013 |

Randomisation by using a block randomisation program with a block size of 6. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear. No mention of a trial register. However, outcomes stated in the methods section were reported in the results section. |

Unlikely, 21 and 17% loss to follow-up |

Unlikely |

|

Mayr, 2014 |

Randomisation by a closed envelope method. |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear. No mention of a trial register. However, outcomes stated in the methods section were reported in the results section. |

Likely. 19% of patients were lost to follow-up, but no reason was given and no specification to treatment group. |

Unclear. Not stated. |

|

Papandreou, 2013 |

Randomisation method not described: sample included in stratified random sample |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear. No mention of a trial register. However, outcomes stated in the methods section were reported in the results section. |

Unlikely, no loss to follow-up |

Unlikely |

|

Ucar, 2014 |

Randomisation by sealed envelope |

Unlikely |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear, not described |

Unclear. No mention of a trial register. However, outcomes stated in the methods section were reported in the results section. |

Unlikely, 9% and 11% lost to follow-up |

Unlikely |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 18-09-2018

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 26-10-2018

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep niet in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2023 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.kennisinstituut.nl) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn beoogt uniform beleid ten aanzien van de diagnostiek, indicatiestelling, behandeling en nazorg van patiënten met voorste kruisbandletsel.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met VKB-letsel, zoals, maar niet beperkend tot, orthopedisch chirurgen, fysiotherapeuten en andere professionals, zoals revalidatieartsen, chirurgen en sportartsen. Deze andere beroepsgroepen worden betrokken in de knelpuntenanalyse en indien van toepassing toegevoegd aan de richtlijnwerkgroep. Aangezien richtlijnen de klinische besluitvorming ondersteunen is de richtlijn ook bedoeld voor patiënten met VKB-letsel.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2016 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met voorste kruisbandletsel te maken hebben.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname.

De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

Werkgroep

- Dhr. dr. D.E. (Duncan) Meuffels, orthopaedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC te Rotterdam, (NOV) (voorzitter)

- Dhr. prof. dr. R.L. (Ron) Diercks, orthopaedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het UMCG te Groningen, (NOV)

- Dhr. dr. R. (Roy) Hoogeslag, orthopaedisch chirurg, werkzaam in de OCON Sportmedische kliniek te Hengelo, (NOV)

- Dhr. dr. R.W. (Reinoud) Brouwer, orthopaedisch chirurg, werkzaam in het Martini Ziekenhuis te Groningen, (NOV)

- Dhr. dr. R.P.A. (Rob) Janssen, orthopaedisch chirurg-traumatoloog, werkzaam in het Maxima Medisch Centrum te Eindhoven/Veldhoven, (NVA)

- Dhr. drs. P.A. (Peter) Leenhouts, traumachirurg, werkzaam in het AMC te Amsterdam, (NvVH)

- Dhr. drs. E.A. (Edwin) Goedhart, manager sportgeneeskunde, werkzaam bij de KNVB, (VSG)

- Dhr. dr. A.F. (Ton) Lenssen, coördinator onderzoek, werkzaam in het Maastricht UMC te Maastricht, (KNGF)

Meelezers:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland te Utrecht (Patiëntenfederatie Nederland)

Met ondersteuning van:

- Mw. dr. J. (Janneke) Hoogervorst-Schilp, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Mw. dr. B.H. (Bernardine) Stegeman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling” is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of ze in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatie management, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventueel belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Meuffels |

Orthopaedisch chirurg en staflid afdeling orthopaedie, Erasmus MC, Universitair Medisch Centrum Rotterdam |

Buitengewoon staflid revalidatie centrum Rijndam (onbetaald) |

Voorzitter congrescommissie en bestuurslid Nederlandse Arthoscopie Vereniging,

ZonMW: |

Geen actie (onderzoek niet gesponsord door de industrie) |

|

Diercks |

Orthopaedisch chirurg, Hoogleraar klinische sportgeneeskunde UMCG |

Redacteur, leerboek sportgeneeskunde; royalties auteur, leerboek voor orthopedie: royalties board of editors, American Jornal of Sports medicine: onbetaald reviewer voor wetenschappelijke tijdschriften, onbetaald. Bovengenoemd onderzoeksproject zou op lange termijn kunnen uitmonden in een productontwikkeling. Hiervan is op dit moment en in de nabije toekomst geen sprake |

Gezamenlijk onderzoek UT naar verbetering richtapparaat kruisbandreconstructie, geen externe relaties, geen externe financiering. |

Geen actie (valt buiten de afbakening van de richtlijn) |

|

Goedhart |

Medisch manager SportMedisch Centrum KNVB/Bondsarts |

Diverse docentschappen gericht op sportgeneeskunde |

Vicevoorzitter Vereniging voor Sportgeneeskunde. Bestuurslid College Clubartsen en Consulenten. |

Geen actie |

|

Hoogeslag |

Orthopaedisch chirurg 90% |

Hoofd medische staf BVO FC TWENTE 10%. |

Return to sports criteria bij vermoeidheid; Rct naar reconstructie versus repair (hechten) van de vkb ruptuur, repair uitgevoerd met Ligamys van de firma Mathys, reconstructie uitgevoerd met all-inside techniek van de firma Arthrex, niet betaald door de industrie; inclusie beeindigd; biomechanische studie naar vkb hechting met niet-, statisch- en dynamisch-gewrichtsoverbruggende stabilisatie, niet betaald door de industrie; Rct naar type graft te gebruiken voor VKB-reconstructie (quadriceps, patellapees, hamstringspees), niet betaald door de industrie: includerend; Prospectief cohort naar hechting van gescheurde vkb, niet betaald door de industrie: METC pending |

Geen actie |

|

Leenhouts |

Traumachirurg Academisch Medisch Centrum in Amsterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Brouwer |

Orthopaedisch chirurg Martin Ziekenhuis Groningen |

Voorzitter werkgroep knie (=DKS Dutch Knee Society onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Lenssen |

Wetenschappelijk onderzoeker afdeling fysiotherapie MUMC+ (0,8 Fte) |

Senior docent faculteit gezondheidszorg Zuyd Hogeschool tutor SOMT Kerpen (D) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Janssen |

Opleider, orthopaedisch chirurg |

Onbetaalde nevenfuncties: |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland als meelezer te betrekken in het richtlijnproces. Tijdens de oriënterende zoekactie werd gezocht op literatuur naar patiëntenperspectief (zie Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn (module) en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden bij de aanverwante producten.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt taewordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbevelingen uit de eerdere richtlijn (NOV, 2011) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens is er een knelpuntenanalyse gehouden om te inventariseren welke knelpunten er in de praktijk bestaan rondom de zorg voor patiënten met VKB-letsel. De knelpuntenanalyse vond tijdens een Invitational conference plaats, gecombineerd met de knelpuntenanalyse voor de revisie van de richtlijn artroscopie. Hiervoor werden alle belanghebbende partijen (stakeholders) uitgenodigd. Knelpunten konden zowel medisch inhoudelijk zijn, als betrekking hebben op andere aspecten zoals organisatie van zorg, informatieoverdracht of implementatie.

De volgende partijen waren aanwezig bij de Invitational conference en hebben knelpunten aangedragen: Nefemed, Zorginstituut Nederland, ZimmerBiomet Nederland, Nederlandse Vereniging van Arbeids- en Bedrijfsgeneekunde (NVAB), Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap (NHG), Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie (NVvR), Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging (NOV). Een verslag van de Invitational conference met daarin een overzicht van partijen die uitgenodigd waren, is opgenomen in de Knelpuntenanalyse.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de voorzitter en de adviseur concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Deze zijn met de werkgroep besproken waarna de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen heeft vastgesteld. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep per uitgangsvraag welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als kritiek, belangrijk (maar niet kritiek) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de kritieke uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

Er werd eerst oriënterend gezocht naar bestaande buitenlandse richtlijnen en naar systematische reviews in Medline (OVID) en Cochrane Library, en literatuur over patiëntenvoorkeuren en patiëntrelevante uitkomstmaten (patiëntenperspectief). Vervolgens werd voor de afzonderlijke uitgangsvragen aan de hand van specifieke zoektermen gezocht naar gepubliceerde wetenschappelijke studies in (verschillende) elektronische databases. Tevens werd aanvullend gezocht naar studies aan de hand van de literatuurlijsten van de geselecteerde artikelen. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar studies met de hoogste mate van bewijs. De werkgroepleden selecteerden de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria. De geselecteerde artikelen werden gebruikt om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden. De databases waarin is gezocht, de zoekstrategie en de gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag. De zoekstrategie voor de oriënterende zoekactie en patiëntenperspectief zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Individuele studies werden systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (risk of bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR – voor systematische reviews; Cochrane – voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidence-tabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie Schünemann, (2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann, 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE-criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methodiek. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (overall conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de kritieke uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een overall conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje Overwegingen.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag.

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de Kennislacunes beschreven (onder aanverwante producten).

Literatuur

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139. PubMed PMID: 18483053.

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medline (OVID)

2009-aug. 2017

Engels |