Type graft bij behandeling VKB-letsel

Uitgangsvraag

Welke soort graft geeft het beste resultaat bij voorste kruisband-reconstructie?

Aanbeveling

Kies bij een primaire VKB-reconstructie voor een autograft, waarbij zowel een bone-patellar-tendon-bone of hamstring graft kan worden gebruikt.

Verricht een VKB-reconstructie met een single-bundel of dubbel-bundel techniek.

Gebruik geen synthetische grafts in verband met inferieure resultaten en nadelige complicerende factoren op lange termijn.

Er kan geen wetenschappelijk onderbouwde aanbeveling worden gegeven over de keuze van het type fixatie van de diverse grafts.

Er kan geen wetenschappelijk onderbouwde aanbeveling worden gegeven over het gebruik van een hedendaagse (wel of niet geaugmenteerde) VKB-hechttechniek bij operatieve behandeling van acuut VKB-letsel.

Overwegingen

Autograft of Allograft

Het gebruik van een allograft bij de VKB-reconstructie heeft als voordeel dat er geen sprake is van donorplaats morbiditeit, maar een belangrijk nadeel is een inferieure mechanische kwaliteit van de allograft ten opzichte van een autograft. Andere nadelen zijn het beperkte aanbod van allograftweefsel en de hoge kosten. Vanwege bovenstaande nadelen wordt een allograft ondanks het feit dat de resultaten van een allograft bij een primaire reconstructie vergelijkbaar zijn met een de resultaten van een autograft in Nederland zelden gebruikt bij primaire reconstructie, maar is te overwegen indien een autograft niet mogelijk/wenselijk is.

Double-bundle (DB) versus Single-bundle (SB)

Een DB-reconstructie met HT is te overwegen gezien de mogelijk superieure biomechanische clinimetrische uitkomsten (Zhu, 2013; Karikis, 2016; Ventura, 2013). Echter, studies laten tot nu toe geen superieure uitkomsten zien ten aanzien van failure (Liu, 2016; Zhang, 2014; Soumalainen, 2012) en klinische uitkomsten (Zhu, 2013; Zhang, 2014; Soumalainen, 2012; Lee, 2012).

Anatomisch versus niet-anatomisch

De laatste jaren is er bij de reconstructie van de VKB een verschuiving gaande van een niet-anatomische naar een meer anatomische plaatsing van de graft. Een onlangs gepubliceerde systematische review Chen, (2017) bestaande uit vijf RCT’s concludeerde dat de uitkomst van een single bundle anatomische reconstructie beter is dan de niet-anatomische techniek qua stabiliteit en functioneel herstel van de geopereerde knie. Omdat vier van de vijf geïncludeerde RCTs geen follow-up van tenminste twee jaar hadden, kunnen we bij de revisie van deze richtlijn de anatomische techniek (nog) niet aanbevelen, maar is gezien de resultaten van de systematische review van Chen wel te overwegen.

Fixatietechniek

Vanwege de grote heterogeniteit in studies met betrekking tot de gebruikte graft types, operatietechnieken en fixatietechnieken kon het effect van fixatietechniek niet worden geanalyseerd, en blijft de aanbeveling uit de oude richtlijn staan.

Primary repair

Hooggradig bewijs voor de effectiviteit van het hechten van de geruptureerde voorste kruisband in de acute fase ontbreekt Van Eck, (2017). Hoewel in biomechanische studies bij het hechten van de geruptureerde voorste kruisband alleen dynamische augmentatie leidde tot normalisatie van de anterieure tibiale translatie (Hoogeslag, 2018; Schliemann, 2017) zijn er resultaten van meerdere retrospectieve en prospectieve klinische series na hedendaagse arthroscopische, niet-, statisch- en dynamisch-geaugmenteerde voorste kruisband hechttechnieken beschreven (Achtning, 2016; Ateschrang, 2017; Buchler, 2016; DiFelice, 2018; Eggli, 2016; Evangelopoulos, 2017; Henle, 2015; Kohl, 2016; Kosters, 2015; Mackay, 2015; Meister, 2017; Murray, 2016; Schliemann, 2017; Van der List, 2017). Over het algemeen betreft het studies met korte of hooguit middellange follow-up. Hoewel de resultaten van patiënt gerapporteerde uitkomstmaten over het algemeen goed tot uitstekend lijken te zijn, wordt er met name een hoge frequentie van heringrepen vanwege zwelling of strekbeperking gerapporteerd (Ateschrang, 2016; Buchler, 2016; Eggli, 2016; Haberli, 2018; Henle, 2015; Kohl, 2013; Kosters, 2015; Meister, 2017). Daarnaast lijkt er een associatie te bestaan tussen de lokalisatie van het letsel en de kans op failure/re-ruptuur, waarbij proximale rupturen een betere prognose lijken te hebben in vergelijking met midsubstance of distale rupturen (DiFelice, 2018; Evangelopoulos, 2017; Henle, 2017; Krismer, 2017; Mackay, 2015; Van der List, 2017). Het toevoegen van een letsel-overbruggende collageen bioscaffold lijkt de kans op failure/re-rupturen te verkleinen, en mogelijk wordt ook het resultaat na het hechten van proximaal VKB-letsel hierdoor ook in positieve zin beïnvloed. Hierover zijn echter slechts twee studies beschreven (Evangelopoulos, 2017; Murray, 2016). Eén prospectieve cohortstudie van patiënten die een dynamisch geaugmenteerde VKB-hechting ondergingen bij midsubstance VKB-letsel, van wie bij een deel wel en bij een deel geen letsel overbruggende bioscaffold werd geplaatst. Het complicatie risico daalde van 79% zonder bioscaffold naar 9% met bioscaffold binnen twee jaar postoperatief Evangelopoulos, (2017). En één prospectieve (met VKB-reconstructie vergelijkende) cohortstudie van patiënten die een statisch geaugmenteerde VKB-hechting ondergingen bij proximaal VKB-letsel, bij wie ook een letsel overbruggende bioscaffold werd geplaatst; dit betrof een veiligheidsstudie van het gebruik van een dergelijke bioscaffold bij de mens Murray, (2016). Er werd geen verschil gevonden tussen beide groepen, binnen 3 maanden postoperatief.

Er is slechts één RCT gepubliceerd die een hedendaagse VKB-hechttechniek vergeleek met de gouden standaard, de VKB-reconstructie Schliemann, (2017). Hoewel er ook nu op basis van patiënt gerapporteerde uitkomst maten een goed tot uitstekend resultaat werd bereikt binnen 1 jaar postoperatief, zonder verschil tussen beide groepen, werden geen adverse events (zoals complicaties, operatieve heringrepen of failure/re-rupturen) gerapporteerd.

Geconcludeerd kan worden dat hedendaagse hechttechnieken van de acute VKB, met alleen korte(re) termijn resultaten op het eerste oog goed zijn. Mogelijk bieden deze een belofte van een alternatieve behandeling naast of in plaats van de huidige gouden standaard, de VKB-reconstructie. Echter, ondanks dat hedendaagse VKB-hechttechnieken op dit moment bij patiënten worden toegepast, ontbreekt het aan hooggradige bewijslast betreffende de effectiviteit hiervan en aan langere termijn follow-up. Derhalve zou toepassing binnen een METC-goedgekeurd studieverband kunnen worden overwogen, totdat er sufficiënt hooggradig en lange(re) termijn bewijs is over de effectiviteit van dergelijke hedendaagse VKB-hechttechnieken.

Synthetische grafts

Vanwege het gebrek aan nieuwe studies voor synthetische grafts blijft de aanbeveling uit de oude richtlijn staan.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In the past twenty-five years, there have been many developments surrounding anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction using different graft types. Various types of research have been performed into outcomes using different grafts. However, until now this has not yet led to the definition of one graft as the superior graft. Therefore, the working group investigated the advantages and disadvantages of various graft types in order to reach a recommendation for graft selection. Moreover, nowadays there is trend to repair acute ACL ruptures without or with statistic of dynamic augmentation.

1. Type of grafts

Autologous Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone (BPTB) graft or Hamstrings tendon (HT) graft or Quadriceps tendon (QT) graft

The BPTB grafts and HT grafts are the most commonly used graft types in reconstructive ACL surgery. Initially, BPTB reconstructions were the first choice, but the choice has shifted more and more towards the use of HT grafts. The advantage of BPTB grafts is that they may lead to less laxity, the disadvantage is that a subset of patients suffers from pain in the knee (anterior knee pain). The risk of anterior knee pain is lower after HT reconstructions (RR 0.49) Poolman, (2007), which is thereby the greatest advantage of this technique.

The QT graft with or without bone block from the patella is used much less often, but this might be a good alternative for the BPTB or HT grafts.

Autograft or Allograft

The use of allograft in ACL reconstruction (for example BPTB, HT, QT, tibialis anterior or Achilles tendon graft) has the advantage that there is no morbidity of the donor site, such as pain or weakness of the muscle group from which the tendon is harvested. A major disadvantage is an inferior mechanical quality of the allograft when compared to an autograft due to the fact that it has undergone a sterilisation process, as well as the fact that the tissue is often from older donors. Other disadvantages are the risk of infection or rejection of the graft, the limited availability of allograft and the higher costs. Due to the aforementioned disadvantages, allografts are rarely used in the Netherlands in primary ACL reconstructions.

2. Types of surgical techniques

Double-bundle (DB) or Single-bundle (SB) Hamstrings tendon (HT) graft

Generally, the ACL is described as having two bundles, the anteromedial and the posterolateral bundle. To restore the original anatomy as much as possible, a DB hamstring reconstruction could be performed. This guideline text has chosen to use the common English nomenclature: the two grafts (semitendinosus and gracilis tendon) are placed in one of the two positions of the original bundles, usually in two femoral and one or two tibial tunnels. In a SB reconstruction, both grafts are placed together as one bundle in one femoral and one tibial tunnel.

The main advantage of the DB reconstruction might be that it is comparable to the original anatomy, which possibly results in more stability (and possibly in better long-term effects). Advantages of SB reconstruction might be that it is less complicated and a less time-consuming procedure. Strong evidence supports that in patients undergoing intra-articular ACL reconstruction the practitioner should use either single bundle or double bundle technique, because the measured outcomes are similar Shea, (2015).

3. Type of Fixation

There have been many developments around fixation of the selected graft. Mechanically, the point of fixation is the weakest link. Therefore, it is important that the selected fixation technique is sufficiently strong to enable a functional post-treatment. For both proximal and distal fixation, there is a great diversity of fixation techniques. The fixation greatly depends on the graft that is used.

4. Primary repair

The concept of primary repair of the ruptured ACL is not new. Late in the last century multiple clinical series were published, mostly on open repair of acute ruptures of the ACL. Eventually ACL suture repair was abandoned in favour of ACL reconstruction because of disappointing results.

Nevertheless, suture repair of the ruptured ACL has reawakened in recent years. Pre-clinical animal model studies led to good results. Moreover, some promising short to medium term results have been reported using non-augmented, as well as static or -mostly- dynamic augmented ACL suture repair techniques. Contrary to static augmentation, in dynamic augmentation a braid is fixed to an additional elastic link (spring-in-screw mechanism) on the tibial side, instead of fixation to the tibial and the femoral bone directly.

However, the body of evidence for clinical studies using contemporary ACL suture techniques is rather small and there is a lack of high-quality evidence. Therefore, the working group researched the evidence about the efficacy of this treatment modality in patients with an ACL rupture.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. Graft types

Hamstrings tendon (HT) autograft versus Bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) autograft

Failure

|

Very low GRADE |

The probability of graft failure is similar after an ACL injury reconstruction with a HT or BPTB autograft.

Sources (Li, 2012; Kautzner, 2015) |

Clinimetrics (Pivot shift test)

|

Low GRADE |

The probability of a positive pivot shift test is higher after a reconstruction with an HT autograft compared with a BPTB autograft.

Sources (Li, 2012; Mohtadi, 2015 and 2016; Razi, 2014) |

Clinimetrics (Lachman test)

|

Very low GRADE |

The probability of a positive Lachman test after an ACL injury reconstruction with a BPTB autograft seems to be similar to a reconstruction with an HT autograft.

Sources (Konrads, 2016; Kautzner, 2015; Razi, 2014) |

Clinimetrics (IKDC score)

|

Moderate GRADE |

The probability for a (nearly) Normal IKDC Physical Examination score is similar after an ACL injury reconstruction with an HT or BPTB autograft.

Sources (Li, 2012) |

Adverse events

|

Very low GRADE |

The probability of experiencing an adverse event is likely to be lower after an HT autograft compared to a BPTB autograft reconstruction.

Sources (Li, 2012; Kautzner, 2015; Razi, 2014) |

PROMs (Lysholm score)

|

Low GRADE |

There is no difference in average Lysholm score between patients with an HT autograft or BPTB autograft reconstruction.

Sources (Razi, 2015) |

Autograft versus allograft

Failure

|

Very low GRADE |

The risk of failure is lower in autograft compared to allograft ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Zeng, 2016) |

Clinimetrics (Pivot shift test)

|

Moderate GRADE |

The probability of a positive pivot shift test after an ACL reconstruction with an autograft is similar to the probability after reconstruction with an allograft.

Sources (Zeng, 2016) |

Clinimetrics (Lachman test)

|

Low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in a positive Lachman test between patients with an allograft or autograft after a reconstruction.

Sources (Zeng, 2016) |

Clinimetrics (Instrumented laxity test)

|

Very low GRADE |

The mean score measured with an instrumented anterior laxity test is likely to be closer to normal in autograft compared to allograft ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Zeng, 2016) |

Clinimetrics (IKDC Physical Examimation score)

|

Moderate GRADE |

The probability for a (nearly) Normal (grade A and B) overall IKDC Physical Examination score is similar for patients with autograft or allograft ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Zeng, 2016) |

Adverse events

|

- GRADE |

As no data on adverse events were reported, no conclusion could be drawn on the risk of an adverse event with an allograft or autograft. |

PROMs (Lysholm score)

|

Low GRADE |

There is no difference in average Lysholm score between patients with an autograft or allograft after an ACL injury.

Sources (Zeng, 2016) |

2. Type of surgical techniques

Failure

|

Very low GRADE |

The probability of failure seems to be similar for a double-bundle and single-bundle ACL reconstructions.

Sources (Liu, 2016; Zhang, 2014; Soumalainen, 2012) |

Clinimetrics (Pivot shift test)

|

Low GRADE |

The probability of a positive pivot shift test is lower after a double-bundle ACL reconstruction compared to a single-bundle autograft.

Sources (Zhu, 2013; Liu, 2016; Karikis, 2016; Koken, 2014; Ventura, 2013; Soumalainen, 2012; Lee, 2012) |

Clinimetrics (Lachman test)

|

Low GRADE |

The probability of a positive Lachman test is lower after a double-bundle ACL reconstruction compared to a single-bundle reconstruction.

Sources (Zhu, 2013; Karikis, 2016; Zhang, 2014; Ventura, 2013; Lee, 2012) |

Clinimetrics (IKDC score)

|

Low GRADE |

There is no difference in IKDC Physical Examination score between a double-bundle or single-bundle ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Zhu, 2013; Koken, 2014; Soumalainen, 2012; Lee, 2012) |

Adverse events

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in the risk of adverse events between a double-bundle or single-bundle ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Zhu, 2013; Liu, 2016) |

PROMs (Lysholm score)

|

Moderate GRADE |

There is no difference in Lysholm score between a double-bundle or single-bundle ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Zhu, 2013; Zhang, 2014; Soumalainen, 2012; Lee, 2012) |

3. Type of fixation

Because of the large heterogeneity in graft types used, surgery techniques and fixation techniques of the published studies, the effect of type of fixation could not be analysed.

4. Primary repair

Failure

|

- GRADE |

As no data with a high level of evidence on the risk of failure were reported, no conclusion could be drawn on failure after contemporary primary ACL suture repair. |

Adverse events

|

- GRADE |

As no data with a high level of evidence on adverse events were reported, no conclusion could be drawn on the risk of adverse events with a contemporary primary ACL suture repair. |

Clinimetrics

Lachman test

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in anterior tibial translation as measured with the Lachman test between those having contemporary primary ACL suture repair compared to those having ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Schliemann, 2017) |

Pivot shift test

|

- GRADE |

As no data with a high level of evidence on the pivot shift test were reported, no conclusion could be drawn on rate of a positive pivot shift test with a contemporary primary ACL suture repair. |

PROMs

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no difference in PROMs (Lysholm and IKDC score) between those having contemporary primary ACL suture repair compared to those having ACL reconstruction.

Sources (Schliemann, 2017) |

Samenvatting literatuur

1. Graft types

Hamstrings tendon (HT) autograft versus Bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) autograft

Description of included studies

Li (2012) evaluated the effectiveness of ACL reconstruction using either HT autografts or BPTB autografts. Authors systematically searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and EMBASE up to December 2011. Only RCTs comparing HT with BTPB autografts among patients with unilateral ACL injury were included. Quasi-RCTs or RCTs with follow-up time less than 24 months were excluded. Nine RCTs in eleven reports were included. Study-specific estimates were not reported for all outcomes of interest.

Five RCTs published after the search date of Li were included, from which two RCTs contained the same population (Mohtadi, 2015; Mohtadi, 2016). Therefore, the data of four RCTs were included (Konrads, 2016; Mohtadi, 2016; Kautzner, 2015; Razi, 2014). The number of patients in these studies ranged from 62 to 230, and the follow-up ranged from two to ten years. The mean age ranged from 26 to 30 years, and most participants were males (range 55 to 83%). Failure rate was reported in only one of these studies Kautzner, (2015) and the pivot shift test was also only reported in one of these studies Razi, (2014).

Meta-analyses were performed for the outcomes failure, clinimetrics, PROMs and adverse events including the nine RCTs by Li and the four additional RCTs.

Results

1. Failure

Li (2012) reported a pooled relative risk for post-operative graft failure, without reporting the results of individual trials and/or a definition of graft failure. Therefore, the reported failure of the study by Kautzner (2015) could not be added to the meta-analysis. The pooled estimate for HT autograft in the meta-analysis by Li et al. was RR 1.37 (95%CI 0.67 to 2.81), meaning that the probability of graft failure is not statistically significantly different between an HT autograft or a BPTB autograft. The study by Kautzner also found no statistically significant difference in graft failure between HT autograft and BPTB autograft (RR 2.00; 95% CI 0.38 to 10.59).

2. Clinimetrics

The results for the pivot shift test, the Lachman test and the IKDC physical examination were used as indicators for clinimetrics.

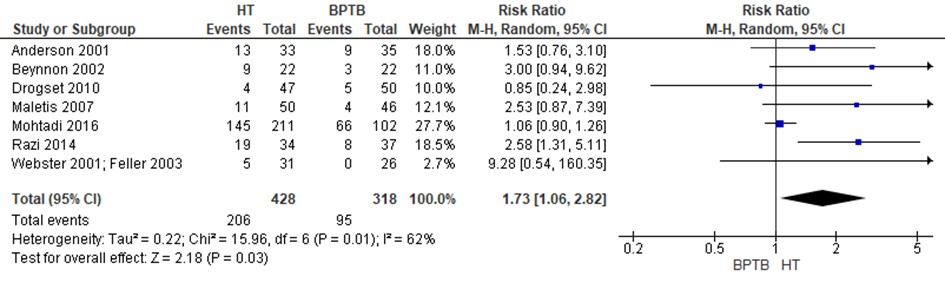

Five studies included in the review by Li and two of the additional trials reported data on the pivot shift test. Li used a negative pivot shift test as outcome in their meta-analysis, therefore the results of the included individual studies were transformed to a positive pivot shift test outcome. The results of the final meta-analysis are depicted in figure 1. The pooled estimate for HT autograft was RR 1.73 (95%CI 1.06 to 2.82), meaning that the rate of a positive pivot shift test (indicating knee joint instability) is 73% higher after a reconstruction with an HT autograft compared with a BPTB autograft. Thus, the results on knee stability measured with the pivot shift test are better using BPTB autograft compared to HT autograft.

Five studies included in the review by Li and three of the additional trials reported data on the pivot shift test. Li (2012) reported only pooled data of the Lachman test. Therefore, the reported Lachman test of the three additional studies (Konrads, 2016; Kautzner, 2015; Razi, 2014) could not be added to the meta-analysis. The pooled RR for HT autograft in the meta-analysis of Li was 0.65 (95% CI 0.18 to 2.34), meaning that the rate of a negative Lachman test is not statistically significantly different between an HT autograft or a BPTB autograft. In the study by Konrads (2016) the RR for HT autograft of a negative Lachman test was 0.78 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.27) and in the study by Razi (2014) the RR for HT autograft was 0.52 (95% CI 0.30 to 0.90). The study by Kautzner (2015) reported the mean Lachman test. The mean Lachman test laxity after 2 years follow-up was 1.3 mm (range 0 to 10) in the HT group and 1 mm (range 0 to 12) in the BPTB group (P=0.624). Due to the limited data, no meta-analysis was performed for the Lachman test.

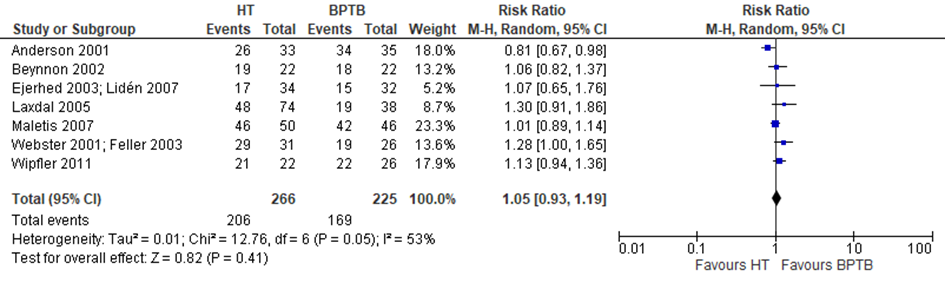

Seven trials in the review by Li (2012) reported data on the IKDC Physical Examination score. The additional trials did not report IKDC scores. A meta-analysis was performed and depicted in figure 2. The probability of a (nearly) Normal (grade A and B) overall IKDC score does not differ between an HT autograft or a BPTB autograft (RR 1.05 95% CI: 0.93-1.19).

Figure 1 Meta-analysis HT versus BPTB of the outcome positive pivot

Figure 2 Meta-analysis HT versus BPTB of the outcome IKDC Physical Examination score

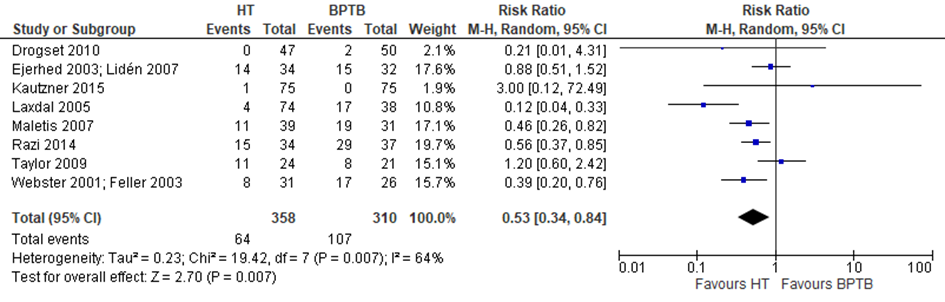

3. Adverse events

Li reported data on adverse events, defined by kneeling pain. The studies by Kautzner (2015) and Razi (2014) both reported postoperative complications (wound infection), these were considered as adverse events as well and included in the meta-analysis (figure 3). The probabily of experiencing an adverse event is 47% lower after a reconstruction with an HT autograft compared to a BPTB autograft (RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.84).

Figure 3 Meta-analysis HT versus BPTB of the outcome adverse events

4. PROMs

The results of the Lysholm score were considered as an indicator of PROMs.

The Lysholm score was reported in only one of the included trials Razi, (2014). The mean Lysholm score after 2 years follow-up was 90 (SD 7.6) in the HT autograft group and 88 (SD 7.5) in the BPTB autograft group, which was not a statistically significant difference (P=0.30).

Level of evidence

Failure: The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method) and imprecision (too few patients with a failure and in total included in the meta-analysis).

Clinimetrics: The level of evidence of the outcome pivot shift test was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method) and imprecision (confidence interval crossed the boundary of a clinically meaningful difference). The level of evidence of the outcome Lachman test was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method), inconsistency (large heterogeneity) and imprecision (too few patients). The level of evidence of the outcome IKDC Physical Examination score was downgraded by one level because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method).

Adverse events: The level of evidence of the outcome adverse events was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method), inconsistency (minimal or no overlap of confidence intervals), indirectness (differences in outcomes measures) and imprecision (too few patients with an event).

PROMs: The level of evidence of the outcome Lysholm score was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method) and imprecision (too few patients).

Quadriceps graft

Only one RCT was found comparing quadriceps grafts with BPTB graft in 26 patients Lund, (2014). The working group interpreted this as insufficient evidence to assess the effect of quadriceps graft.

Autograft versus allograft

Description of included studies

Zeng (2016) undertook a meta-analysis of RCTs to compare autografts with allograft in ACL reconstruction. Medline, Embase and the Cochrane Library were searched from 1 January 1966 till 28 June 2014. RCTs, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses concerning primary ACL reconstruction patients were included. The reconstruction had to be arthroscopically assisted, whereby autograft was compared to allograft. The methodological quality scores of RCTs had to be 2 or greater, assessed by the Modified Oxford Scale. Inclusion criterium for follow-up was a minimum of 2 years and the minimum sample size of RCTs was 20 participants per group.

For this clinical question, only the data from RCTs will be described. Nine RCTs were included in the meta-analysis of Zeng. The meta-analysis was not updated with studies published from June 2014 till February 2017.

Results

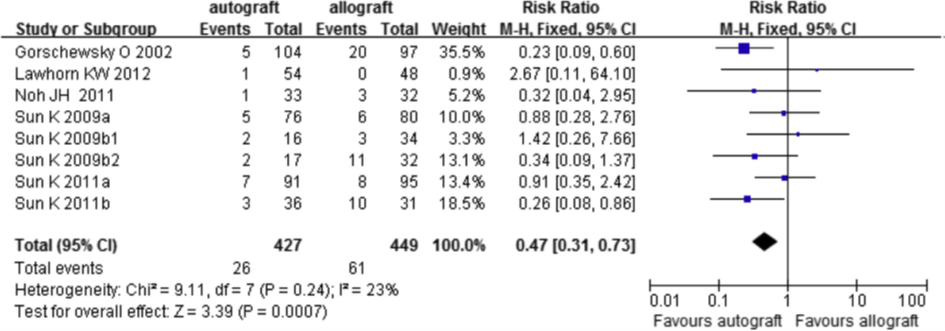

1. Failure

Clinical failure of the graft included revision surgery, graft rupture, +2 pivot shift or higher, and side-to-side arthrometer difference >5 mm). Seven out of nine trials reported data on failure. The individual study effect estimates and the pooled estimate are given in figure 4. The risk of failure is 53% lower with an autograft compared with an allograft (RR 0.47; 95%CI 0.31 to 0.73).

Figure 4 Meta-analysis autograft versus allograft of the outcome failure (Zeng, 2016)

2. Clinimetrics

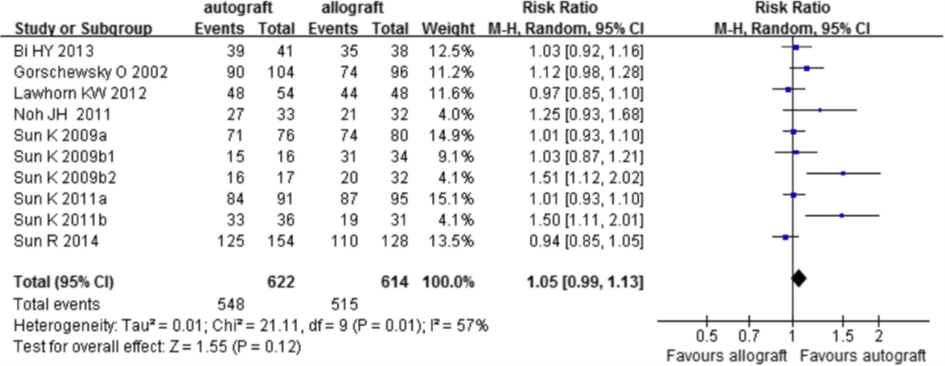

As an indicator for clinimetrics, the results from the pivot shift test, the Lachman test and the IKDC Physical Examination score and were used. All nine included trials reported data on the pivot shift test. The results are depicted in figure 5. There was no difference in a positive pivot shift test between an autograft or an allograft (RR 1.05; 95%CI 0.99 to 1.13).

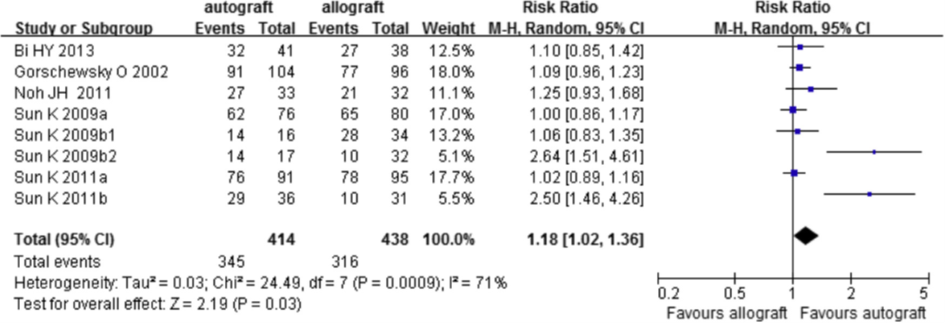

Seven out of nine trials reported results on the Lachman test (figure 6). The pooled estimate was RR 1.18 (95%CI 1.02 to 1.36) meaning that the risk of a negative Lachman test is 18% higher after a reconstruction with an autograft compared to an allograft. Because of insufficient description of the analysis method in the review of Zeng, the working group could not interpret the clinical relevance of this difference.

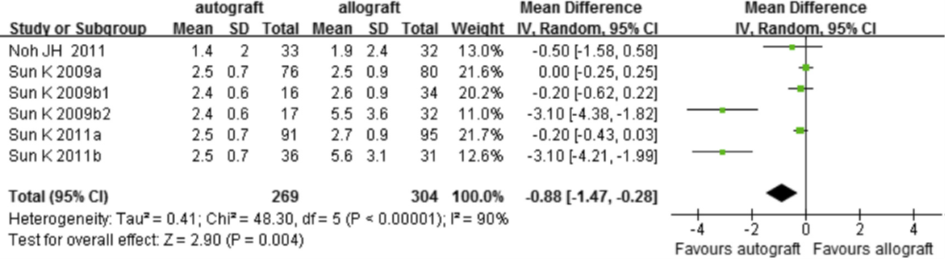

Five out of nine trials used an instrumented anterior laxity test (figure 7). The pooled weighted mean difference was -0.88 (95%CI -1.47 to -0.28), which was interpreted by the working group as a non-clinically relevant difference.

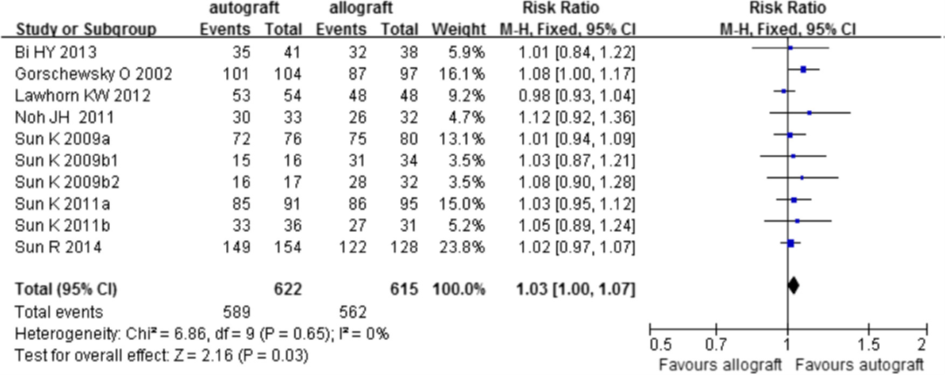

All nine trials reported data on the IKDC Physical Examination score. The meta-analysis is depicted in figure 8. The probability of a (nearly) Normal (grade A and B) overall IKDC score is not different between an allograft or an autograft (RR 1.03; 95%CI 1.00 to 1.07).

Figure 5 Meta-analysis allograft versus autograft of the outcome pivot shift test (Zeng, 2016)

Figure 6 Meta-analysis allograft versus autograft of the outcome Lachman test (Zeng, 2016)

Figure 7 Meta-analysis autograft versus allograft of the outcome instrumented laxity test (Zeng, 2016)

Figure 8 Meta-analysis allograft versus autograft of the outcome IKDC Physical Examination score (Zeng, 2016)

3. Adverse events

Zeng (2016) reported no data on adverse events.

4. PROMs

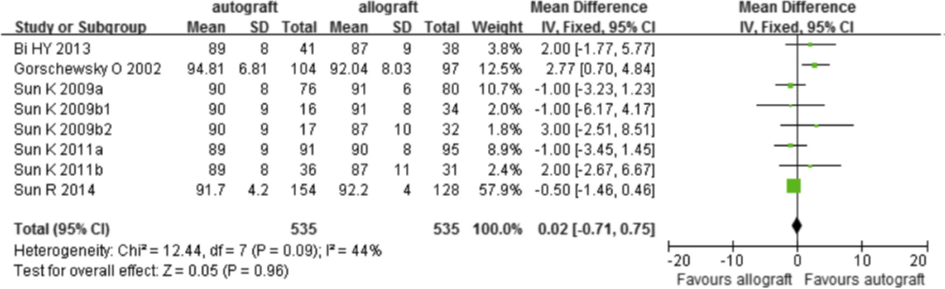

The results of the Lysholm score were considered as an indicator of PROMs. Seven out of nine trials used the Lysholm questionnaire as an indicator for knee instability (Figure 9). The Lysholm score was no different between patients with an allograft or patients with an autograft (mean difference in score 0.02; 95%CI -0.71 to 0.75).

Figure 9 Meta-analysis of the outcome Lysholm score (Zeng, 2016)

Level of evidence

Failure: The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method), unexplained inconsistency (four trials reported a reduced risk of failure, while four studies reported either a null effect or an increased risk of failure) and imprecision (in total less than 100 failures were included in the meta-analysis).

Clinimetrics: The level of evidence of the outcome pivot shift test was downgraded by one level because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method). The level of evidence of the outcome Lachman test was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method) and imprecision (confidence interval crossed the boundary of a clinically meaningful difference). The level of evidence of the outcome instrumented laxity test was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method), inconsistency and imprecision (confidence interval crossed the boundary of a clinically meaningful difference). The level of evidence of the outcome IKDC Physical Examination score was downgraded by one level because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method).

Adverse events: Due to a lack of data, the level of evidence for adverse events could not be graded.

PROMs: The level of evidence of the outcome Lysholm score was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method) and imprecision (too few patients).

2. Type of surgical techniques

Double-bundle (DB) versus Single-bundle (SB)

Description of included studies

Zhu (2013) performed a meta-analysis of RCTs to compare double-bundle (DB) with single-bundle (SB) ACL reconstruction. PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library were searched from 1 January 1966 till September 2011. Only prospective and randomised studies comparing the clinical outcomes of DB versus SB ACL reconstruction, with patients over 18 years were included. Trails with non-clinical outcomes and without a follow-up were excluded.

A total of 18 trials were included in the meta-analysis of Zhu, of which 9 trials were prospective randomised trials with a minimum mean follow-up of two years and will be described.

An additional eight studies were included in the meta-analysis published after the search date (September 2011) by Zhu (Liu, 2016; Karikis, 2016; Zhang, 2014; Koken, 2014; Ventura, 2013; Suomalainen, 2012; Nunez, 2012; Lee, 2012). The number of patients in these studies ranged from 42 to 108 and the follow-up ranged from 2 to 6.7 years. The mean age ranged from 25 to 30 years and most participants were males (range 66 to 97%). Adverse events were only reported in one of the studies Liu, (2016).

Results

1. Failure

Zhu reported no data on failure of the graft. Three of the additional trials reported data on failures. The study by Liu (2016) identified two traumatic failures at the final follow-up in the DB group and zero in the SB groups (RR 5.00; 95% CI 0.25 to 101.0). In the study by Zhang (2014), one patient in the DB and two patients in the SB group (2% and 3% respectively) had a re-rupture (RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.05 to 6.21). In the study by Soumalainen (2012), one patient in the DB group (3%) and ten in the SB group (17%) required an ACL revision surgery (RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.03 to 1.49). No meta-analysis was performed, due to the limited data.

2. Clinimetrics

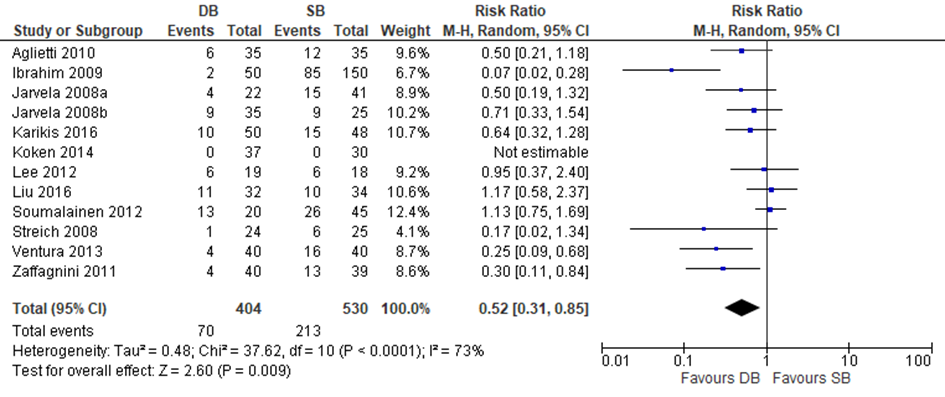

The results from the pivot shift test, the Lachman test and the IKDC Physical Examination score were used as an indicator for clinimetrics. Six trials included in Zhu and six out of the nine additional trials reported data on the pivot shift test. Zhu used a negative pivot shift test as outcome in their meta-analysis, therefore the results of the included individual studies were transformed to a positive pivot shift test outcome. The results of the final meta-analysis with the twelve studies are depicted in figure 10. The pooled estimate for DB reconstruction was RR 0.52 (0.31 to 0.85), meaning that the rate of a positive pivot shift test (indicating worse knee joint stability) is 47% lower after a DB reconstruction compared with a SB reconstruction. Thus, the results on knee stability measured with the pivot shift test are better using DB compared to SB.

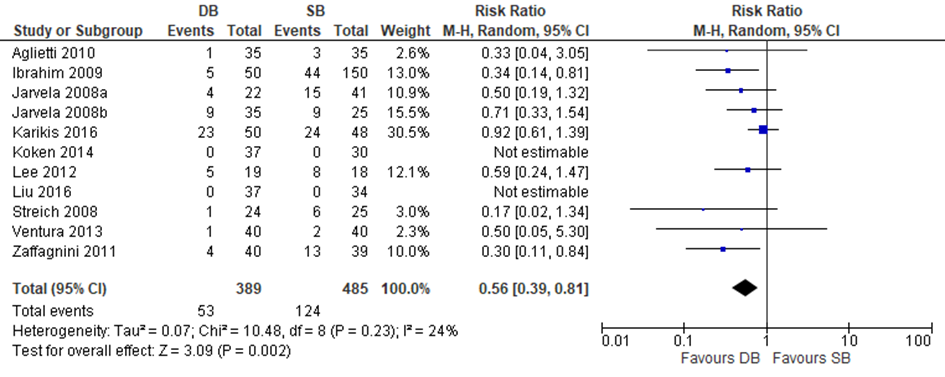

Two trials included in Zhu and four out of the nine additional trials reported data on the Lachman test. Zhu used a negative Lachman test as outcome in their meta-analysis, therefore the results of the included individual studies were transformed to a positive Lachman test outcome. A meta-analysis was performed with these seven studies. The results are depicted in figure 11. The pooled estimate was RR 0.56 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.81), meaning that the probability of increased anterior laxity as measured by a positive Lachman test was 44% lower after a reconstruction with a DB compared to SB graft.

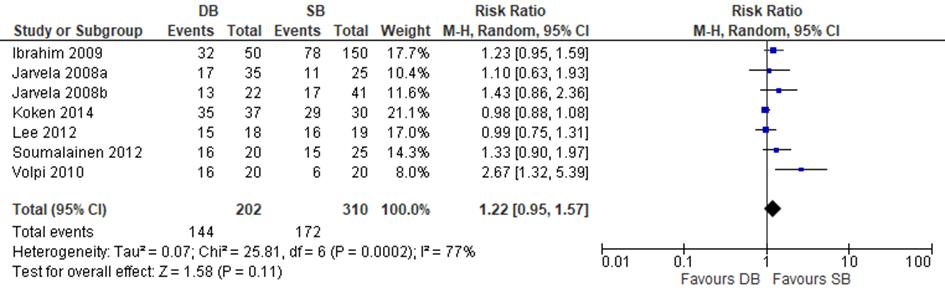

Four trials included in Zhu and three of the additional trials reported dichotomous data on the IKDC score (normal/nearly normal versus abnormal/severely) and could be included in a meta-analysis to pool the risk ratio. The results of the meta-analysis are depicted in figure 12. The pooled estimate for (nearly) normal IKDC was RR 1.22 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.57), meaning that there was no statistically significant difference in the IKDC Physical Examination score between a reconstruction with a DB graft compared to a reconstruction with a SB graft.

Figure 10 Meta-analysis DB versus SB of the outcome positive pivot shift test

Figure 11 Meta-analysis DB versus SB of the outcome positive Lachman test

Figure 12 Meta-analysis DB versus SB of the outcome IKDC Physical Examination score (normal versus abnormal/severely)

3. Adverse events

Complications were reported in the review by Zhu and were taken as an indicator for adverse events. Zhu reported that complications are the composite of secondary meniscal

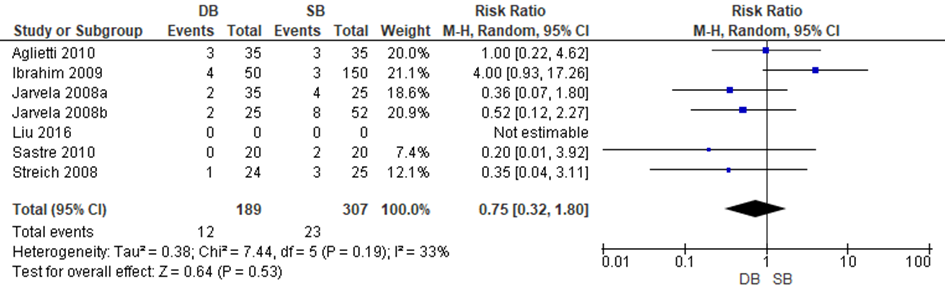

tears or unhealed meniscal fixation requiring a second arthroscopy, deep infections, graft failures, cyclops lesions, thrombosis as well as pain and swelling. Six trials included in Zhu reported data to allow a meta-analysis of the results. Liu reported that no participants developed intra-operative or post-operative complications. The results of the meta-analysis are depicted in figure 13. Pooled estimates indicated that the risk of complications is slightly lower with a DB reconstruction compared to an SB reconstruction, but the difference was not statistically significant (RR 0.73 95%CI: 0.32-1.80).

Figure 13 Meta-analysis DB versus SB of the outcome adverse events

4. PROMs

The results from the Lysholm scores were used as an indicator for PROMs.

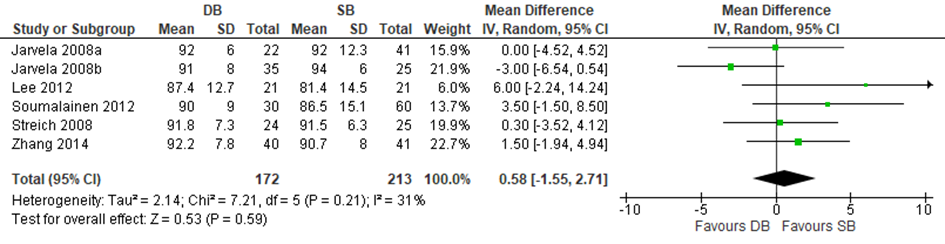

Three trials included in Zhu and three of the additional trials reported mean differences in Lysholm scores and could be included in a meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis are depicted in figure 14. The pooled mean difference was 0.58 (95% CI -1.55 to 2.71), meaning that there was no statistically significant difference in the Lysholm score between a reconstruction with a DB graft compared and a reconstruction with an SB graft.

Figure 14 Meta-analysis DB versus SB of the outcome Lysholm score

Level of evidence

Failure: The level of evidence of the outcome failure was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method), indirectness (differences in outcomes measures) and imprecision (too few patients with an event).

Clinimetrics: The level of evidence of the outcome pivot shift test was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method), inconsistency (large heterogeneity). The level of evidence of the outcome Lachman test was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method) and imprecision (confidence interval crossed the boundary of a clinically meaningful difference). The level of evidence of the outcome IKDC Physical Examination score was downgraded by two levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method) and inconsistency (large heterogeneity).

Adverse events: The level of evidence of the outcome adverse events was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method), indirectness (differences in outcomes measures) and imprecision (too few patients with an event).

PROMs: The level of evidence of the outcome Lysholm score was downgraded by one level because of the risk of bias (none of the included trials used a blinding method).

3. Type of fixation

Because of the large heterogeneity in graft types used, surgery techniques and fixation techniques of the published studies, the effect of type of fixation could not be analysed.

4. Primary repair

Description of included studies

Only one of the included studies, Schliemann (2017), reported a contemporary ACL suture repair technique) and performed a randomised controlled trial in 60 patients with acute ACL tears. Thirty patients (mean age 28.2±11.4 yr) were randomised to the intervention group and underwent a contemporary arthroscopic ACL suture repair technique (dynamic intra-ligamentary stabilisation (DIS)) and 30 patients (mean age 29.1±12.0 yr) were randomised to the control group, undergoing an anatomic semitendinosus autograft ACL reconstruction. After both procedures, the knee was placed in a knee immobiliser for four days. Afterwards, patients underwent a brace-free rehabilitation programme. Follow-up time was twelve months. Outcomes were based on the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score and Lysholm score.

Meunier (2007) described the long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial in 100 patients with an acute and total rupture of the ACL who were treated between 1980 and 1983. A total of 44 patients (mean age 22 yr; range 14-30) were randomised to the intervention group and underwent surgical repair (proximal ruptures non-augmented, mid-substance ruptures augmented with ITB) and 56 patients (mean age 21 yr; range 14-30) were randomised to the control group, undergoing conservative treatment. After repair, the limb was immobilised in a long leg cast and no weight bearing was allowed until the cast was removed after six weeks. An intensive rehabilitation programme was then instituted. The rehabilitation of the conservative group was not described. Follow-up time was 15 years. Outcomes were having secondary treatment, Lachman test, pivot shift test, osteoarthritis and Lysholm score. The analyses were stratified afterwards, whereby the repair group was divided into those without augmentation (Sr) and those with augmentation (Sar). The conservative group was divided into those without surgery (NSns) and those who underwent late reconstruction (NSrec). For our literature analysis, the groups were combined (Sr/Sar versus NSns/NSrec).

Results

1. Failure/ re-rupture

In the RCT of Meunier (2007), there was no statistically significant difference in having secondary treatment of meniscus injury between the repair group and the conservative group (RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.17 to 1.04; P=0.06).

Schliemann did not report the outcome failure/re-rupture rate.

2. Clinimetrics

Lachman test

In the RCT by Meunier (2007), there was no statistically significant difference in a positive Lachman test between the repair group and the conservative group after 15-yr follow-up (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.61 to 1.24; P=0.44).

In the RCT by Schliemann (2017) it was reported that the difference in anterior tibial translation between the injured and the contralateral knee was 7.6 mm in the DIS group and 8.4 mm in the ACLR group prior to the intervention. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups after 12-month follow-up (DIS: 1.7 mm, ACLR: 1.4 mm: NS).

Pivot shift test

In the RCT by Meunier (2007), there was no statistically significant difference in a positive pivot shift test between the repair group and the conservative group after 15-yr follow-up (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.39 to 1.22; P=0.20).

Schliemann did not report the outcome pivot shift.

3. Adverse events

Adverse events were not reported as outcome in the included studies.

4. PROMs

Lysholm score

In the RCT by Meunier (2007), there was no difference between the repair group and the conservative group in Lysholm score (good/excellent versus fair) after 15-yr follow-up (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.29 to 1.80; P=0.27).

In the RCT by Schliemann (2017), the mean Lysholm score after 1-yr follow-up was 89.8 (SD 11.0) in the repair group and 89.9 (SD 15.5) in the reconstruction group, which was not a statistically significant difference (MD 0.1; 95% CI -6.85 to 7.05; P=0.98).

IKDC score

In the RCT by Schliemann (2017), the mean IKDC score after 1-yr follow-up was 85.7 (SD 12.4) in the repair group and 84.8 (SD 19.4) in the reconstruction group, which was not a statistically significant difference (MD 0.9; 95% CI -9.32 to 7.51; P=0.83).

Meunier (2007) did not report the outcome IKDC score.

Level of evidence

Failure/re-rupture: Because of limited data, the level of evidence for failure/re-rupture could not be graded.

Clinimetrics: The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment, unclear if a blinding method was used and bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis), imprecision (too few patients) and indirectness (conservative treatment instead of reconstruction as comparison).

Adverse events: Because of limited data, the level of evidence for adverse events could not be graded.

PROMs: The level of evidence for the outcome PROMs was downgraded by three levels because of the risk of bias (unclear or inadequate blinding and bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis) and indirectness (difference in outcome measures).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

- What is the effectiveness of different autografts (BPTB, QT) compared to HT autograft in ACL reconstruction?

- What is the effectiveness of autograft compared to allograft in ACL reconstruction?

- What is the effectiveness of SB hamstring compared to DB hamstring in ACL reconstruction?

- What is the effectiveness of different fixation methods in ACL reconstruction (bio-absorbable versus metallic, suspensory versus aperture, cortical button versus transfemoral suspensory, inter-tunnel versus extra-tunnel)?

- What is the effectiveness of a repair compared to reconstruction in patients with ACL injury?

P: patients with ACL reconstruction;

I: 1. Graft type (BPTB, HT, QT);

2. Use of autograft;

3. SB HT reconstruction;

4. Fixation technique (screw (metal, bio-absorbable), button, et cetera);

5. Non-augmented or augmented primary suture repair.

C: 1. One (or more) other graft types;

2. Use of allograft;

3. DB HT reconstruction;

4. One (or more) of other fixation techniques;

5. Reconstruction;

O: Failure, clinimetrics, adverse event and PROMs.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered failure, clinimetrics, adverse event and PROMs as critical outcome measures for decision-making.

The working group did not define the outcome measures a priori, but applied the definitions used in the studies.

The working group did not define clinical (patient) relevant differences a priori.

Search and select (Method)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms. For the update of the literature, both databases were searched from the previous search date (December 2009) till February 2017. A separate search was performed for the question of repair. Therefore, both databases were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 till September 2017. The detailed strategy of both searches is depicted under the tab Methods. The updated systematic literature search resulted in 469 hits, and the literature search for repair resulted in 308 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review with evidence tables, risk of bias evaluation and a detailed search strategy.

- Prospective randomised controlled trials of patients with ACL injury evaluating the effect of different grafts (BPTB, HT (DB – SB), QT, allograft, artificial), different graft techniques (tunnel variation, double bundle – single bundle) different fixation techniques and non-augmented or augmented primary suture repair on PROMs or failure after a minimum follow-up of 2 years.

Initially, 149 studies were selected from the updated reconstruction search based on title and abstract by one or both reviewers. After reading the full text, 132 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 17 studies were included.

Seventeen studies were included in the literature analysis, three systematic reviews and fourteen additional RCTs.

Nine studies were selected by one or both reviewers from the repair search, based on title and abstract. After reading the full text, seven studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and two studies were included in the literature analysis, both RCTs (Schliemann, 2017; Meunier, 2007). Important study characteristics and results are depicted in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is depicted in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Achtnich A, Herbst E, Forkel P, et al. Acute Proximal Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears: Outcomes After Arthroscopic Suture Anchor Repair Versus Anatomic Single-Bundle Reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(12):2562-2569.

- Ahlden M, Sernert N, Karlsson J, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing double- and single-bundle techniques for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2484-91.

- Ateschrang A, Ahmad SS, Stockle U, et al. Recovery of ACL function after dynamic intraligamentary stabilization is resultant to restoration of ACL integrity and scar tissue formation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017.

- Buchler L, Regli D, Evangelopoulos DS, et al. Functional recovery following primary ACL repair with dynamic intraligamentary stabilization. Knee. 2016;23(3):549-553.

- Chen H, Tie K, Qi Y,et al. Anteromedial versus transtibial technique in single-bundle autologous hamstring ACL reconstruction: a meta-analysis of prospective randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s13018-017-0671-3. Review. PubMed PMID: 29115973; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5678560.

- DiFelice GS, van der List JP. Clinical Outcomes of Arthroscopic Primary Repair of Proximal Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears Are Maintained at Midterm Follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2018. 29373290.

- Eggli S, Roder C, Perler G,et al. Five year results of the first ten ACL patients treated with dynamic intraligamentary stabilisation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:105.

- Evangelopoulos DS, Kohl S, Schwienbacher S, et al. Collagen application reduces complication rates of mid-substance ACL tears treated with dynamic intraligamentary stabilization. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(8):2414-2419.

- Henle P, Bieri KS, Brand M, et al. Patient and surgical characteristics that affect revision risk in dynamic intraligamentary stabilization of the anterior cruciate ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017.

- Henle P, Roder C, Perler G, et al. Dynamic Intraligamentary Stabilization (DIS) for treatment of acute anterior cruciate ligament ruptures: case series experience of the first three years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:27.

- Hoogeslag RAG, Brouwer RW, Huis In 't Veld R,et al. Dynamic augmentation restores anterior tibial translation in ACL suture repair: a biomechanical comparison of non-, static and dynamic augmentation techniques. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018.

- Karikis I, Desai N, Sernert N, et al. Comparison of Anatomic Double- and Single-Bundle Techniques for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Using Hamstring Tendon Autografts: A Prospective Randomized Study With 5-Year Clinical and Radiographic Follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1225-36.

- Kautzner J, Kos P, Hanus M, et al. A comparison of ACL reconstruction using patellar tendon versus hamstring autograft in female patients: a prospective randomised study. Int Orthop. 2015;39(1):125-30.

- Kohl S, Evangelopoulos DS, Kohlhof H, et al. Anterior crucial ligament rupture: self-healing through dynamic intraligamentary stabilization technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(3):599-605.

- Kohl S, Evangelopoulos DS, Schar MO, et al. Dynamic intraligamentary stabilisation: initial experience with treatment of acute ACL ruptures. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(6):793-798.

- Koken M, Akan B, Kaya A, et al. Comparing the anatomic single-bundle versus the anatomic double-bundle for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective, randomized, single blind, clinical study. European Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 2014;5(3):247-52.

- Konrads C, Reppenhagen S, Plumhoff P, et al. No significant difference in clinical outcome and knee stability between patellar tendon and semitendinosus tendon in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(4):521-5.

- Kosters C, Herbort M, Schliemann B, et al. Dynamic intraligamentary stabilization of the anterior cruciate ligament. Operative technique and short-term clinical results. Unfallchirurg. 2015;118(4):364-371.

- Krismer AM, Gousopoulos L, Kohl S,et al. Factors influencing the success of anterior cruciate ligament repair with dynamic intraligamentary stabilisation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(12):3923-3928.

- Lee S, Kim H, Jang J, et.al. Comparison of anterior and rotatory laxity using navigation between single- and double-bundle ACL reconstruction: prospective randomized trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(4):752-61.

- Li S, Chen Y, Lin Z, et al. A systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials comparing hamstring autografts versus bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts for the reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(9):1287-97.

- Liu Y, Cui G, Yan H, et al. Comparison Between Single- and Double-Bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With 6- to 8-Stranded Hamstring Autograft: A Prospective, Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(9):2314-22.

- Mackay GM, Blyth MJ, Anthony I, et al. A review of ligament augmentation with the InternalBrace: the surgical principle is described for the lateral ankle ligament and ACL repair in particular, and a comprehensive review of other surgical applications and techniques is presented. Surg Technol Int. 2015;26:239-255.

- Meister M, Koch J, Amsler F, et al. ACL suturing using dynamic intraligamentary stabilisation showing good clinical outcome but a high reoperation rate: a retrospective independent study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017.

- Mohtadi N, Chan D, Barber R,et al. Reruptures, Reinjuries, and Revisions at a Minimum 2-Year Follow-up: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing 3 Graft Types for ACL Reconstruction. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26(2):96-107.

- Mohtadi N, Chan D, Barber R, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Patellar Tendon, Hamstring Tendon, and Double-Bundle ACL Reconstructions: Patient-Reported and Clinical Outcomes at a Minimal 2-Year Follow-up. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25(4):321-31.

- Murray MM, Flutie BM, Kalish LA, et al. The Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair (BEAR) Procedure: An Early Feasibility Cohort Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(11):2325967116672176.

- Nunez M, Sastre S, Nunez E, et al. Health-related quality of life and direct costs in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury: single-bundle versus double-bundle reconstruction in a low-demand cohort--a randomized trial with 2 years of follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):929-35.

- Razi M, Sarzaeem MM, Kazemian GH, et al. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: a comparison between bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts and fourstrand hamstring grafts. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014;28:134.

- Shea KG, Carey JL, Richmond J, et al. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Evidence-Based Guideline on Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. JBJS. 2015;97(8):672674

- Schliemann B, Glasbrenner J, Rosenbaum D, et al. Changes in gait pattern and early functional results after ACL repair are comparable to those of ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017.

- Schliemann B, Lenschow S, Domnick C, et al. Knee joint kinematics after dynamic intraligamentary stabilization: cadaveric study on a novel anterior cruciate ligament repair technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(4):1184-1190.

- Suomalainen P, Jarvela T, Paakkala A, et al. Double-bundle versus single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective randomized study with 5-year results. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1511-8.

- Van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Range of motion and complications following primary repair versus reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Knee. 2017;24(4):798-807.

- Van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Role of tear location on outcomes of open primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament: A systematic review of historical studies. Knee. 2017;24(5):898-908. 28803759.

- van Eck CF, Limpisvasti O, ElAttrache NS. Is There a Role for Internal Bracing and Repair of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament? A Systematic Literature Review. Am J Sports Med. 2017:363546517717956.

- Ventura A, Iori S, Legnani C, et al. Single-bundle versus double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: assessment with vertical jump test. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(7):1201-10.

- Zeng C, Gao SG, Li H, et al. Autograft Versus Allograft in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials and Systematic Review of Overlapping Systematic Reviews. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(1):153-63.e18.

- Zhang Z, Gu B, Zhu W, et al. Double-bundle versus single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions: a prospective, randomized study with 2-year follow-up. Eur. 2014;24(4):559-65.

- Zhu Y, Tang RK, Zhao P,et al. Double-bundle reconstruction results in superior clinical outcome than single-bundle reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(5):1085-96.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

HS autograft versus BPTB autograft |

|||||||

|

Li, 2012 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to December 2011

A: Anderson, 2001 B: Beynnon, 2002 C: Ejerhed, 2003/ Lidén, 2007 D: Webster 2001/ Feller, 2003 E: Laxdal, 2005 F: Maletis, 2007 G: Taylor, 2009 H: Drogset, 2010 I: Wipfler, 2011

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: not reported

Source of funding: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

9 studies included

N, mean age A: 70 patients, 14-44 yr B: 56 patients, 18-52 yr C: 71 patients, 14-59 yr D: 65 patients, 18-40 yr E: 134 patients, 12-52 yr F: 99 patients, 14-48 yr G: 64 patients, 17-45 yr H: 115 patients, 18-45 yr I: 62 patients, 25-64 yr |

HS autograft

|

BPTB autograft

|

A: 35 months B: 36 months C: 86 months D: 36 months E: 24 months F: 24 months G: 36 months H: 24 months I: 105 months

Incomplete outcome data, N (intervention/control) A: 2/0 B: 6/6 C: 3/2 D: 3/5 E: 12/4 F: 3/0 G: 5/3 H: 10/8 I: 9/5

|

1. Failure No definition reported

Individual trials results were not reported. Total n/N HT: 17/340 BPTB: 11/293

Pooled RR: 1.37 (95% CI 0.67 to 2.81) favouring BPTB Heterogeneity (I2): 23%

2. Clinimetrics Pivot shift test, Lachman test

Pivot shift test (negative) Effect measure: RR (95%CI) A: 0.82 (0.58 till1.14) B: 0.68 (0.47 till 1.01) D: 0.84 (0.71 till 1.00) F: 0.85 (0.72 till 1.01) H: 1.02 (0.90 till 1.15)

Pooled RR: 0.87 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.96) favouring HT Heterogeneity (I2): 47%

Lachman test (negative) Individual trials results were not reported. Total n/N HT: 40/85 BPTB: 44/78

Pooled RR: 0.65 (95% CI 0.18 to 2.34) favouring HT Heterogeneity (I2): ? (P<0.0001)

3. Adverse events Anterior knee pain

Anterior knee pain Individual trials results were not reported. Total n/N HT: 35/161 BPTB: 41/118

Pooled RR: 0.66 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.96) favouring HT Heterogeneity (I2): ? (P=0.88)

Kneeling pain Effect measure: RR (95%CI) C: 0.88 (0.51 till 1.52) D: 0.39 (0.20 till 0.76) E: 0.12 (0.04 till 0.33) F: 0.46 (0.26 till 0.82) G: 1.20 (0.60 till 2.42) H: 0.21 (0.01-4.31)

Pooled RR: 0.49 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.91) favouring HT Heterogeneity (I2): 73%

4. PROMS IKDC score

IKDC (normal/nearly normal versus abnormal/severely) Effect measure: RR (95%CI) A: 0.81 (0.67 till 0.98) B: 1.06 (0.82 till 1.37) C: 1.07 (0.65 till 1.76) D: 1.28 (1.00 till 1.65) E: 1.30 (0.91 till 1.86) F: 1.01 (0.89 till 1.14) I: 1.13 (0.94 till 1.36)

Pooled RR: 1.05 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.19) favouring BPTB Heterogeneity (I2): 53% |

Brief description of author’s conclusion: There was a statistically significant lower rate of negative Pivot test, anterior knee pain and kneeling pain in the HT group than in the BPTB group.

Level of evidence: 1. Failure: VERY LOW Due to risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment) and imprecision (too few patients with a failure and in total included in the meta-analysis)

2. Clinimetrics: Pivot shift test: MODERATE Due to risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment) Lachman test: VERY LOW Due to risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment), inconsistency (based on a p-value of <0.0001) and imprecision (too few patients with an event)

3. Adverse event: Anterior knee pain: LOW Due to risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment) and imprecision (too few patients with an event) Kneeling pain: VERY LOW Due to risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment), inconsistency (two studies reported no effect and three studies a decreased effect) and imprecision (too few patients with an event)

4. PROMS: MODERATE Due to risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment)

|

|

Autograft versus allograft |

|||||||

|

Zeng, 2016 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs and SRs

Literature search up to June 2014

A: Lawhorn, 2012 B: Sun, 2011a C: Sun, 2011b D: Noh, 2011 E: Sun 2009a F: Sun 2009b G: Gorschewsky, 2002 H: Bi, 2013 I: Sun, 2014

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: not reported

Source of funding: Non-commercial

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

9 RCT’s included

N, mean age, sex (auto/allograft) A: 102 patients, 30.3/33.3 yr, 59/79% male B: 186 patients, 29.6/31.2 yr, 78/82% male C: 67 patients, 30.9/30.3 yr, 78/77% male D: 64 patients, 32/22 yr, 81/81% male E: 156 patients, 31.7/32.8 yr, 80/79% male F: 67 patients, 29.7/31.8 yr, 73/65% male G: 301 patients, 31.6/34.4 yr, 76/73% male H: 79 patients, 33/34 yr, sex NR I: 282 patients, 27.5/27.1 yr, 69/73% male

|

Autograft A: hamstring tendon (HT) B: HT C: HT D: HT E: bone-patellar-tendon-bone (BPTB) F: BPTB G: BPTB H: HT I: HT

|

Allograft A: Anterior tibialis, freshfrozen, nonirradiated, nonechemically treated B: HT, fresh-frozen, nonirradiated C: HT, fresh-frozen, irradiated, dose of 2.5 Mrad, thawed in sterile physiological fluid at room temperature D: Free-tendon Achilles, fresh-frozen E: BPTB, fresh-frozen, nonirradiated F: BPTB, fresh-frozen, nonirradiated, and BPTB, fresh-frozen, irradiated, dose of 2.5 Mrad, thawed in sterile physiological fluid at room temperature G: BPTB, irradiated, gamma ray, 1.5 Mrad and 15 kGy, osmotic treatment, oxidation, solvent drying H: Soft-tissue graft, Co-60 ray, -80°C preservation, unfreezing at room temperature, washed by gentamicin saline solution, soaking in povidone-iodine (0.2 g/L) for 10 min I: Deep-frozen tibialis anterior tendon nonirradiated

|

End of follow-up A: >24 months B: range 72-120 months C: range 30-56 months D: auto 28.1/ allo 31.6 months E: range 48 till 96 months F: range 13 till 24 months G: range 10 till 32 months H: range 36 till 57 months I: >36 months

|

1. Failure Including revision surgery, graft rupture, +2 pivot shift or higher, and side-to-side arthrometer difference >5 mm)

Effect measure: RR (95%CI) A: 2.67 (0.11-64.10) B: 0.91 (0.35 till 2.42) C: 0.26 (0.08 till 0.86) D: 0.32 (0.04 till 2.95) E: 0.88 (0.28 till 2.76) F: 1.42 (0.26 till 7.66 & 0.34 (0.09 till 1.37) G: 0.23 (0.09-0.60)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR: 0.47 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.73) favouring autograft Heterogeneity (I2): 23% (p=0.24)

2. Clinimetrics Pivot shift test, Lachman test; instrumented laxity test)

Pivot-shift test Effect measure: RR (95%CI) A: 0.97 (0.85 till 1.10) B: 1.01 (0.93 till 1.10) C: 1.50 (1.11 till 2.01) D: 1.25 (0.93 till 1.68) E: 1.01 (0.93 till 1.10) F: 1.03 (0.87 till 1.21) & 1.51 (1.12 till 2.02) G: 1.12 (0.98 till 1.28) H: 1.03 (0.92 till 1.16) I: 0.94 (0.85till 1.05)

Pooled RR: 1.05 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.13) favouring autograft Heterogeneity (I2): 57%

Lachman test Effect measure: RR (95%CI) B: 1.02 (0.89 till 1.16) C: 2.50 (1.46 till 4.26) D: 1.25 (0.93 till 1.68) E: 1.00 (0.86 till1.17) F: 1.06 (0.83till 1.35) & 2.64 (1.51 till 4.61) G: 1.09 (0.96 till 1.23) H: 1.10 (0.85 till 1.42)

Pooled RR: 1.18 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.36) favouring autograft Heterogeneity (I2): 71%

Instrumented laxity test Effect measure: MD (95%CI) B: -0.20 (-0.43 to 0.03) C: -3.10 (-4.21 to -1.99) D: -0.50 (-1.58 to 0.58) E: 0.00 (-0.25 to 0.25) F: -0.20 (-0.62 to 0.22 & -3.10 (-4.38 to -1.82)

Pooled MD: -0.88 (-1.47 to -0.28) favouring autograft Heterogeneity (I2): 90%

3. Adverse events Not reported

4. PROMS Overall IKDC score, Lysholm score

Overall IKDC Effect measure: RR (95%CI) A: 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) B: 1.03 (0.92 to 1.12) C: 1.05 (0.89 to 1.24) D: 1.12 (0.92 to 1.36) E: 1.01 (0.94 to 1.09) F: 1.03 (0.87 to 1.21) G: 1.08 (0.90 to 1.28) H: 1.01 (0.84 to 1.22) I: 1.02 (0.97 to 1.07)

Pooled RR: 1.03 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.07) favouring autograft Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Lysholm score Effect measure: MD (95%CI) B: -1.00 (-3.45 to 1.45) C: 2.00 (-2.67 to 6.67) E: -1.00 (-3.23 to 1.23) F: -1.00 (-6.17 to 4.17) & 3.00 (-2.51 to 8.51) G: 2.77 (0.70-4.84) H: 2.00 (-1.77 to 5.77) I: -0.50 (-1.46 to 0.46)

Pooled mean difference: 0.02 (95% CI -0.71 to 0.75) Heterogeneity (I2): 44% |

Subgroup analyses for (non)irradiated allograft reported.

Brief description of author’s conclusion: statistically significant differences in favour of autograft observed for clinical failure, Lachman test, instrumented laxity test and Tegner score. In subgroup analyses outcomes only significant for autograft versus irradiated allograft.

Level of evidence: 1. Failure: VERY LOW Due to risk of bias (none used a blinding method), heterogeneity (four studies reduced risk, four studies no effect or potential increased risk), imprecision (low number of events)

2. Clinimetrics: Pivot-shift test: MODERATE Due to risk of bias (none used a blinding method) Lachman test: LOW Due to risk of bias (none used a blinding method) and imprecision (CI crosses clinical meaningful difference boundary) Instrumented laxity test: VERY LOW Due to risk of bias (none used a blinding method), inconsistency and imprecision (CI crosses clinical meaningful difference boundary)

4. PROMS: Overall IKDC score: MODERATE Due to risk of bias (none used a blinding method) Lysholm score: LOW Due to risk of bias (none used a blinding method) and imprecision (too few patients)

|

|

Double bundle versus single bundle |

|||||||

|

Zhu, 2013 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to September 2011

A: Adachi, 2004 B: Jarvela, 2008 C: Streich, 2008 D: Jarvela, 2008 E: Ibrahim, 2009 F: Volpi, 2010 G: Aglietti, 2010 H: Sastre, 2010 I: Zaffagnini, 2011

Study design: RCT’s

Setting and Country: Not stated

Source of funding: The following was reported: “There are no further sources of funding for the study, authors, or preparation of the manuscript.” It is unclear to which other sources of funding are eluded.

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

18 trials included of which 9 trials were prospective randomized trials with a mean follow-up≥ 2 yr, which will be described.

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age DB/SB, % male DB/SB A: 108 patients 29/29 years; 62/58% B: 60 patiënt 35/30 years; 69/76% C: 49 patiënt 30/29 years; 100/100% D: 77 patients 33.0 years; NA E: 200 patients 28 years; 100% F: 40 patients 30/27 years; 75/85% G: 70 patients 28/28 years; 80/71% H: 40 patients 31/29 years; 70/60% I: 79 patients 27/26 years; 55/51% |

Double bundle

|

Single bundle

|

End-point of follow-up (mean, mo (range)):

A: 32 (24 to 36) B: 27 (24 to 36) C: 24 (23 to 25) D: 24 (24 to 35) E: 29 (25 to 38) F: 30 (21 to 37) G: 24 (NA) H: 24 (NA) I: 103 (96 to 120)

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) Not reported

|

1. Failure Not reported

2. Clinimetrics Pivot shift test, Lachman test, instrumental laxity test (KT-1000 arthrometer)

Pivot shift test Effect measure: RR (95% CI): B: 1.29 (0.95 to 1.75) C: 1.26 (1.00 to 1.60) D: 1.16 (0.82 to 1.65) E: 2.22 (1.83 to 2.68) G: 1.26 (0.95 to 1.67) I: 1.35 (1.06 to 1.72)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model) RR 1.50 (95% CI 1.35 to 1.66) favoring SB Heterogeneity (I2): 79% (0.000)

Lachman test Effect measure: RR (95% CI): E: 1.27 (1.11 to 1.46) G: 1.06 (0.95 to 1.19)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 1.14 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.24) favoring SB Heterogeneity (I2): 75% (p=0.046)

Instrumental laxity test Effect measure: MD (95% CI): B: -0.90 (-2.06 to 0.26) C: 0.20 (-0.75 to 1.15) D: -0.40 (-1.57 to 0.77) G: -1.00 (-1.63 to -0.37)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): MD -0.64 (95% CI- 1.08 to -0.20) favoring DB Heterogeneity (I2):350% (p=0.20)

3. Adverse events Complications

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): B: 0.48 (0.09 to 2.44) C: 0.32 (0.03 to 3.30) D: 0.32 (0.05 to 1.89) E: 4.26 (0.92 to 19.74) G: 1.00 (0.19 to 5.33) H: 0.18 (0.01 to 4.01)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 0.80 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.70) favoring DB Heterogeneity (I2): 34% (p=0.19)

4. PROMS IKDC score, Lysholm score

IKDC score Effect measure: RR (95% CI): D: 1.10 (0.63 to 1.93) E: 1.23 (1.03 to 1.83) F: 2.67 (1.32 to 5.39) I: 1.31 (1.02 to 1.69)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model):

Lysholm score Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): B: 0.00 (-4.52 to 4.52) C: 0.30 (-3.52 to 4.12) D: -3.00 (-6.54 to 0.54)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): MD -1.11 (95% CI –3.36 to -1.14) favoring SB Heterogeneity (I2): 0% (p=0.397) |

Level of evidence: As this review could be updated with 7 trails published after 2011, the level of evidence was not graded for the outcomes reported in this review. |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

BPTB versus HS autograft |

|||||||

|

Mohtadi, 2016 & Mohtadi, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: patients presenting with isolated ACL deficiency

Country: Canada

Source of funding: Commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 110 Control:220

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 28 (9.7) C: 28 (9.8)

Sex: I: 57% M C: 55% M

|

Patellor Tendon

|

Quadrupled hamstring tendon and double-bundle hamstring tendon

|

Length of follow-up: 2 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 4 (4%) Reasons (Lost to follow-up (n=1); withdrawals (n=3))

Control: N = 4 (%) Reasons (Lost to follow-up (n=3); moved, unable to return for follow-up (n=1))

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 4 (4%) Reasons (Lost to follow-up (n=1); withdrawals (n=3))

Control: N = 4 (%) Reasons (Lost to follow-up (n=3); moved, unable to return for follow-up (n=1))

|

Not reported.

Pivot shift test (negative) at two years follow-up, n/N

I: 36/102 C: 66/211 RR (HS versus BPTB) 0.89 (95%CI: 0.64-1.23)

Lachman test Not reported

Not reported

Not reported |

|

|

Konrads, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Consecutive patients received ACL reconstruction

Country: Germany

Source of funding: Unclear |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 31 Control: 31

Important prognostic factors2: Were not reported per group Age (min, max): 29 years (18, 44)

Sex: 73% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Unclear

|

BPTB - the middle third of the ipsilateral patellar tendon in bone–patellar tendon–bone technique (BPTB group) with interference screw fixation at femoral and tibial

|

ST - ipsilateral semitendinosus tendon (ST group), with endobutton fixation at the femur and suture-disc fixation at the tibia. The semitendinosus tendon was prepared as a quadruple or triple graft according to its length.

|

Length of follow-up: 10 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 7 (23%)

Control: N = 8 (26%) Reasons (traumatic transplant tear (n=1))

Overall, five could not be located and nine refused to attend the follow-up because of business reasons or unwillingness.

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 7 (23%)

Control: N = 8 (26%) Reasons (traumatic transplant tear (n=1))

Overall, five could not be located and nine refused to attend the follow-up because of business reasons or unwillingness. |

Not reported.

Pivot shift test, not reported

Lachman test (negative) at ten years follow-up, n/N I: 16/24 C: 12/23 RR (HS versus BPTB) 0.78 (95%CI 0.48-1.27)

Not reported

Lysholm score, mean (min, max) I: 92.0 (63, 98) C: 91.8 (62, 98) P=0.66 |

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. However, it is unclear whether this trial received funding.

Pivot shift test was mentioned in the methods section, but not among the results. |

|

Kautzner, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: patients presenting with ACL deficiency

Country: Czech Republic

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 75 Control: 75

Important prognostic factors2: Were not reported per group Mean age (min, max): 26 years (17, 47)

Sex: not reported

|

BTB (bone-patellar tendon-bone) Authors used a combination of crosspin femoral and interference-screw tibial fixation |

HT (hamstring)

Authors used a suspension femoral fixation and interference-screw tibial fixation |

Length of follow-up: Two years with a minimum of one year

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 1 (2%) Reasons (not reported)

Control: N = 2 (3%) Reasons (not reported)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 1 (2%) Reasons (not reported)

Control: N = 2 (3%) Reasons (not reported)

|

Defined as graft rupture or failure determined during arthroscopy

I: 2 (2.7%) C: 4 (5.3%) RR (HS versus BPTB): 2.00 (95%CI: 0.38-10.59)

Pivot shift test, not reported

Lachman test (positive) at two years follow-up, mean (min, max) I: 1 mm (0-12) C: 1.3 mm (0-10)

Defined as postoperative complication (DVT, wound infection)

DVT I: 4 (6%) C: 4 (6%) RR: 1.00 (95%CI: 0.26-3.85)

Wound infection I: 0 (0%) C: 1 (1%) RR (HS versus BPTB): 3.00 (95%CI: 0.12-72.5)

Lysholm score at two years follow-up, mean (SD) I: 88 (7.5) C: 90 (7.6) P=0.30 MD (HS versus BPTB) -2.0 (95%CI: -4.44 to 0.44) |

Surgery was performed by three surgeons experienced with ACL reconstructions. All patients were clinically evaluated by a single surgeon according to a standardised protocol. |

|

Razi, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: patients presenting with ACL tearing

Country: Iran

Source of funding: Not reported |

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 46 Control: 41

Important prognostic factors2: Age (SD): I: 30 (4.5) C: 28 (3.7)

Sex: I: 83% M C: 88% M

|

BPTB (Bone patellar bone autograft) |

ST (semitendinosus-gracilis) |

Length of follow-up: Three years

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 9 (20%) Reasons (not reported)

Control: N = 7 (17%) Reasons (not reported)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 9 (20%) Reasons (not reported)

Control: N = 7 (17%) Reasons (not reported)

|

Not reported

Pivot shift test (negative) at three years follow-up, n/N

I: 29/37 C: 15/34 RR (HS versus BPTB) 0.56 (95%CI: 0.37-0.85)

Lachman test (negative) at three years follow-up, n/N I: 23/37 C: 11/34 RR (HS versus BPTB) 0.52 (95%CI: 0.30-0.90)

Defined as postoperative complication (DVT, wound infection)

Deep infection I: 1 (3%) C: 2 (6%)

Wound infection I: 3 (8%) C: 2 (6%) RR (HS versus BPTB) 0.75 (95%CI: 0.13-4.26)

Patellar fracture I: 1 (3%) C: 0 (0%)

Not reported |

IKDC score is reported, unclear whether objective or subjective |

|

Double bundle versus single bundle |

|||||||

|

Liu, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Consecutive patients with complete, isolated chronic ACL lesions

Country: China

Source of funding: Not stated

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: Examination under anesthesia or intraoperative findings did not meet inclusion criteria

N total at baseline: Intervention: 40 Control: 40

Important prognostic factors2: Age (range): I: 25 (16 to 45) C: 29 (17 to 47)

Sex: I: 80% M C: 85% M

|

Double bundle |

Single bundle |

Length of follow-up: Average of 80 months (range: 74-86 months)

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 6 (15%) Reasons (not reported)

Control: N = 8 (20%) Reasons (n=1 revision ACL surgery; n=1 unable to receive revision surgery; n=6 not reported)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 6 (15%) Reasons (not reported)

Control: N = 8 (20%) Reasons (n=1 revision ACL surgery; n=1 unable to receive revision surgery; n=6 not reported)

|

The following was reported in the article:

“We identified 2 traumatic failures for instability at the final follow-up in the double bundle group.”

Based on this information: I: 2 (5%) C: 0 (0%) RR: 5.00 (95%CI: 0.25-101.0)

Pivot shift test at end of follow-up, n/N

I: 11/32 C: 10/34 RR 1.17 (95%CI: 0.58-2.37)

Lachman test (positive) at end of follow-up, n/N I: 0/37 C: 0/34

Defined as intra- and postoperative complication

I: 0 (0%) C: 0 (0%) RR: 1.00 (0.02 to 49.2)

IKDC and Lysholm

IKDC score at the end of follow-up, mean (range) I: 92.2 (71.6-100) C: 93.4 (59.8-100)

Lysholm score at the end of follow-up, mean (range) I: 95.4 (76 to 100) C: 95.7 (66 to 100) P=0.438 |

|

|

Karikis, 2016

Two-year follow-up data from Ahlden, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: unselected group of patients without regard to age (if >18 years), sex, or activity level.

Country: Sweden

Source of funding: None commercial

|

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 53 Control: 52

Important prognostic factors2: Age (SD): I: 30 (9) C: 28 (9)

Sex: I: 66% M C: 70% M |

Double bundle |

Single bundle |

Length of follow-up: Five years

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 7 (13%) Reasons (n=6 lost to follow-up; n=1 sustained contralateral femur fracture)

Control: N = 11 (21%) Reasons (n=2 did not receive allocated intervention; n=9 lost to follow-up)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 7 (13%) Reasons (n=6 lost to follow-up; n=1 sustained contralateral femur fracture)

Control: N = 11 (21%) Reasons (n=2 did not receive allocated intervention; n=9 lost to follow-up)

|

Not reported

Pivot shift test (positive) at end of follow-up, n/N

Two year follow-up I: 10/50 C: 15/48 RR 0.64 (95%CI: 0.32-1.28)

Five year follow-up I: 7/45 C: 4/36 RR 1.40 (95%CI: 0.44-4.41)

Lachman test (positive) at end of follow-up, n/N

Two year follow-up I: 23/50 C: 24/48 RR 0.92 (95%CI: 0.61-1.39)