Vezels

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van het toevoegen van vezels aan de voedingsbehandeling van patiënten op de IC?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het gebruik van een sondevoeding met vezels op de intensive care.

Zorg daarbij dat het eiwit- en energiedoel de prioriteit behouden.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effectiviteit van vezelverrijking in vergelijking met geen vezelverrijking bij patiënten op de IC. Hierbij zijn tien RCT’s geïncludeerd. Als cruciale uitkomstmaten voor de besluitvorming zijn diarree en obstipatie meegenomen. Daarnaast werden IC-opnameduur, mortaliteit, aspiratie, abdominale distensie, braken en ileus als belangrijke uitkomstmaten meegenomen.

Voor de adverse events diarree en obstipatie lijkt er een effect te zijn in het voordeel van vezelverrijking. Er werd voor beide wel afgewaardeerd vanwege risico op bias en brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen, maar er werd ook een klinisch relevant verschil gevonden. De GRADE beoordeling komt uit op laag.

Daarmee is de overall bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaten laag.

Het effect van vezels op opnamedagen op de IC is erg onzeker. Dit komt door risico op bias, conflicterende resultaten en brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen. Daarom is er geen eenduidige conclusie te trekken en is de GRADE beoordeling zeer laag.

Ook het effect van vezels op mortaliteit tijdens de IC en met lange follow-up is onzeker. Beide vanwege risico op bias, brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen en een laag aantal events. De GRADE beoordeling is zeer laag.

Voor aspiratie lijkt er niet tot nauwelijks effect te zijn van vezels. Er werd afgewaardeerd vanwege een risico op bias en zeer laag aantal events. De GRADE beoordeling was laag en er werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gezien.

Voor de uitkomstmaat abdominale distensie en braken is het effect van vezels onduidelijk. De GRADE beoordeling is zeer laag. Er is afgewaardeerd vanwege conflicterende resultaten, brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen en een laag aantal events.

Voor de uitkomstmaat ileus zijn geen studies gevonden die dit rapporteerden en kan er geen conclusie en GRADE beoordeling gemaakt worden.

De belangrijke uitkomstmaten konden geen verdere richting geven aan de besluitvorming.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het doel van het toevoegen van vezels is de preventie van diarree en obstipatie (gekozen als belangrijkste uitkomstmaat) en daarnaast het behalen van de eiwitdoelen. Voordelen voor de patiënt kunnen zijn minder kans op buikpijn, ongemak, uitdroging, malabsorptie, decubitus, gebruik van medicatie (laxantia, diarreeremmers) en door het behalen van de eiwitdoelen mogelijk sneller herstel. Als voordeel voor de verzorger kan gedacht worden aan minder handelingen in het toedienen van medicatie (laxantia, diarreeremmers), in de verzorgbaarheid van de patiënt (vervuiling beddengoed, inbrengen flexi-seal, verzorgen decubitus). Uit de literatuuranalyse blijkt dat mogelijk minder klachten van diarree of obstipatie optreden (GRADE: laag). De populatie kan bestaan uit zowel gesedeerde patiënten als patiënten die bij bewustzijn zijn. Patiënten die bij bewustzijn zijn kunnen een groter nadeel ervaren aan het optreden van diarree en obstipatie en hebben in dat opzicht meer voordeel van de interventie. Bij de overweging om vezels toe te voegen is er geen gezamenlijk beslismoment met de patiënt.

Indien de vezels door de fabrikant reeds zijn toegevoegd aan de sondevoeding is er geen verschil in belastbaarheid voor zowel de patiënt als de verzorger. Indien de vezels als supplement worden toegediend is de interventie een extra handeling voor de verzorger, wat extra tijd kost. Daarnaast kan bij een separaat vezelsupplement contaminatie optreden, waar de patiënt zieker van wordt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van de interventie (prijs voor sondevoeding met vezels of vezelsupplement) zijn deels afhankelijk van de onderhandelingen van het ziekenhuis met de facilitaire bedrijven. Over het algemeen zijn de kosten voor een sondevoeding met vezel iets duurder dan zonder vezels. De kosten voor het gebruik van een separaat vezelpreparaat naast een standaard sondevoeding zullen ongeveer overeenkomen.

Echter indien hiermee kosten bespaard kunnen worden, die kunnen optreden bij het ontstaan van diarree en obstipatie (medicatie, materiaal, tijd, complicaties), zullen deze kosten waarschijnlijk niet opwegen tegen de nadelen. Er lijkt op basis van de literatuur geen effect te zijn op kosten van bijvoorbeeld een langere IC-opname. Er is met name sprake van een besparing op kleinere kosten zoals medicatie en materialen (bijv. flexi-seal). Concluderend lijken de kosten geen reden om het al dan niet te implementeren.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is een verschil in de vorm van vezels die gebruikt is in de haalbaarheid van de interventie.

Indien er gekozen wordt voor een sondevoeding met vezels (versus sondevoeding zonder vezel) dan heeft dat geen impact op het proces zoals werkwijze en tijd. Indien er gekozen wordt voor een separaat vezelpreparaat, dan moet deze handmatig door de sondevoeding gemengd worden of separaat door de sonde toegediend worden. Deze handeling kost extra tijd voor de verzorger en geeft risico op complicaties, zoals verstopping van de sonde en contaminatie van de sondevoeding. Dit kan weer gevolgen hebben voor de patiënt, omdat er bijvoorbeeld een nieuwe sonde geplaatst moet worden of de patiënt ziek(er) wordt van de contaminatie.

Concluderend is het gebruik van een sondevoeding met reeds toegevoegde vezels logischerwijs aanvaardbaar en haalbaar en is dit voor een vezelpreparaat niet vanzelfsprekend en zou moeten worden nagekeken in de literatuur.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is mogelijk een voordeel bij het gebruik van sondevoeding met vezels in de preventie van diarree en obstipatie, zo blijkt uit de literatuur. De kosten van sondevoeding met vezels vormen geen belemmering voor de mogelijke implementatie.

De sondevoeding is voor iedereen te gebruiken en goed verkrijgbaar op de Nederlandse markt.

Naar aanleiding van een subgroepanalyse lijkt er geen klinisch relevant verschil in het gebruik van een los vezelpreparaat ten opzichte van een sondevoeding met vezels. Daarom wordt aangeraden te kiezen voor een sondevoeding met vezels gezien de voordelen op haalbaarheid, toepasbaarheid in de dagelijkse praktijk (tijd en kunde van de verzorgers) en het ontbreken van de risico’s ten opzichte van separate vezeltoediening.

NB. Het behalen van het energie- en/of eiwitdoel heeft prioriteit boven het gebruik van vezels. Dat wil zeggen: als de patiënt beter gevoed kan worden met een sondevoeding zonder vezels, dan heeft dat altijd de voorkeur.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De patiënt op de IC heeft veelal een verstoorde darmflora en darmwerking door onder andere medicatie (antibiotica, zuurremmers etc.), ernst van ziekte (orgaanfalen, ischemie etc.) en bijvoorbeeld veranderde motiliteit (door medicatie, immobiliteit en niet-natuurlijk voeden). Het gebruik van vezels bij de patiënten op de IC heeft mogelijk een ander effect dan bij patienten met een “normale” darmflora. In de huidige situatie is er praktijkvariatie in het gebruik van vezels in de voedingsbehandeling van de IC-patiënt en is er onduidelijkheid over het effect hiervan.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Diarrhea and constipation

|

Low GRADE |

Enteral nutrition with fiber may decrease the incidence of diarrhea and constipation, as compared to no fiber enteral nutrition in ICU patients.

Source: Belknap, 1997; Chittawatanarat, 2010; Dobb, 1990; Emery, 1997; Rushdi, 2004; Spapen, 2001; Tuncay, 2018; Yagmurdur, 2016. |

Length of ICU stay

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect is of enteral nutrition with fiber on length of ICU stay, as compared to no fiber enteral nutrition.

Source: Caparros, 2001; Chittawatanarat, 2010; Spapen, 2001; Spindler-Vesel, 2007. |

Mortality

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect is of enteral nutrition with fiber on ICU and long-term mortality, as compared to no fiber enteral nutrition.

Source: Caparros, 2001; Chittawatanarat, 2010; Spapen, 2001; Spindler-Vesel, 2007. |

Aspiration

|

Low GRADE |

Enteral nutrition with fiber may result in little to no difference in the incidence of aspiration when compared with no fiber enteral nutrition in ICU patients.

Source: Caparros, 2001; Chittawatanarat, 2010; Yagmurdur, 2016. |

Abdominal distention and vomiting

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect is of enteral nutrition with fiber on abdominal distention and vomiting, as compared to no fiber enteral nutrition in ICU patients.

Source: Caparros, 2001; Rushdi, 2004; Yagmurdur, 2016. |

Ileus

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure ileus in ICU patients.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Cara (2021) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the outcomes of diet with fiber versus no fiber enriched diet. They searched Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Web of Science Core Collection databases until April 2020.

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials were used for quality assessment. Out of the 19 studies included by Cara (2021), 10 were included in our literature analysis. Seven studies were excluded as they did not meet our inclusion criteria (10 observational studies, one open-label RCT) and one study because of no access to publication. Main outcomes were length of ICU stay and adverse events including incidence of diarrhea, incidence of constipation, bronchial aspiration, vomiting, abdominal distension, and mortality. Studies that included ranged from 30 to 398 patients aged 18 to 93 years. Intervention duration ranged between 3 and 36 days. In Table 1, an overview of the main study characteristics is presented.

Table 1. Study characteristics of included studies.

|

Author, year |

Patients |

Intervention |

Comparison |

Feed type |

N |

|

Belknap 1997 |

Postoperative and nonoperative; various diagnoses |

fiber free formula + psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid (PHM); 14 g/day, soluble

|

fiber-free (no PHM) formula

Ensure, Ensure Plus, Osmolite (Ross Laboratories), or Isocal (Mead-Johnson).

|

Fiber supplement (psyllium)

|

I: 37 C: 23 |

|

Caparros 2001 |

Critical illness |

multifiber formula (Arabic gum, cellulose, FOS, inulin, resistant starch, and soy polysaccharides: Stresson Multifibre; Nutricia) enriched with vitamins; 8.9 g/L, soluble and insoluble

|

fiber-free formula not enriched with vitamins (Nutrison Protein Plus; Nutricia).

|

Fiber in formula

|

I: 105 C: 85 |

|

Chittawatanarat 2010 |

Surgical septic patients |

mixed fiber formula (Nutren Fibre®, Nestlé Suisse S.A.) 15.1 g/L of dietary fiber which was produced by yellow pea fiber mixed with fructo-oligosaccharide, soluble and insoluble |

standard formula without combined fiber (Nutren Optimum) |

Fiber in formula (not available in NLs)

|

I: 17 C: 17 |

|

Dobb and Towler 1990 |

Postoperative and nonoperative; various diagnoses |

iso-osmolar lactose-free feed with soy polysaccharide; 21 g/L, soluble

|

iso-osmolar lactose-free feed without soy polysaccharide (Abbott) |

Fiber in formula (not available in NLs)

|

I: 45 C: 46 |

|

Emery 1997 |

Critical illness |

lactose-free, fiber-free formulas plus pectin from banana flakes; 33.8 g/L, soluble

|

lactose-free, fiber-free formulas plus routine medical treatment for diarrhea

|

Fiber supplement

|

I: 14 C: 17 |

|

Rushdi 2004 |

ICU patients on enteral nutrition with persistent diarrhea |

enteral nutrition enriched with guar gum; 22g/L, soluble

(Sando-source GI Control, Novartis Nutrition GmbH, Munchen, Germany) |

fiber-free enteral nutrition

(Propeptidet, Prime, Nutrition Medical, Inc. USA) |

Fiber in formula

|

I: 10 C: 10 |

|

Spapen 2001 |

Mechanically ventilated ICU patients with severe sepsis/septic shock |

enteral formula with partially hydrolyzed guar supp; 22 g/L, soluble

(Benefiber, Novartis Nutrition, the Netherlands) |

isocaloric isonitroge-nous control feed without fiber

|

Fiber supplement

|

I: 13 C: 12 |

|

Spindler-Vesel 2007 |

Trauma patients (multiple injured patients with an Injury Severity Score of >18) |

1 (B). medical nutrition with fermentable guar gum; 22 g/L, soluble 2 (D) standard formula plus symbiotic supp (β-glucan, inulin, pectin, and resistant starch); 100 g/L, soluble bioactive fibers |

1 standard nonfiber formula(Alitraq Abbot)

|

B = Sondevoeding met vezels, D = los vezel supplement

|

I1: 29 I2: 26 C1: 32 |

|

Tuncay 2018 |

Neurocritical care patients |

enteral formula fortified with prebiotic (FOS); 5.3 g/day total diet fiber with 3.5 g/day, soluble

(Jevity®) |

standard enteral formula

(Osmolite®) |

Fiber in formula

|

I: 23 C: 23 |

|

Yagmurdur 2016 |

Acute cerebrovas-cular disease requiring mechanical ventilation |

fiber- enriched nutrition solution with α-cellulose, Arabic gum, inulin, FOS, soy polysaccharides, and resistant starch; 15 g/L, soluble and insoluble

Nutrison multifibre (500 mL, Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition) |

fiber-free nutrition solution

Nutrison (500 mL, Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition) |

Fiber in formula

|

I: 60 C: 60 |

FOS, Fructooligosaccharides; ICU, intensive care unit

¹Not included in this analysis

Results

- Diarrhea

Cara (2021) included five studies that reported on diarrhea events using the Hart and Dobb scale (Chittawatanarat (2010), Dobb (1990), Emery (1997), Spapen (2001), Yagmurdur (2016)).

Chittawatanarat (2010) defined diarrhea as at least one day with diarrhea score ³12. Dobb (1990) defined diarrhea as patients with diarrhea score >12. Emery (1997) defined diarrhea on last study date. Spapen (2001) and Yagmurdur (2016) defined diarrhea as at least one day with diarrhea.

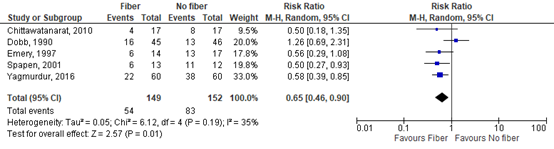

The pooled relative risk (RR) was 0.65 (95% CI 0.46 to 0.90; Figure 1). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of fiber.

Figure 1: The effect of enteral nutrition with fiber on diarrhea incidence defined using the Hart and Dobb (1988) scale.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

Two studies reported on diarrhea events using other scales than the Hart and Dobb scale (Belknap (1997), Tuncay (2018)).

Belknap (1997) reported diarrhea in 8 out of 37 (21.6%) patients in the fiber group and 7 out of 23 (30.4%) in the nonfiber group (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.30 to 1.70).

Tuncay (2018) reported diarrhea in 2 out of 23 (8.7%) patients in the fiber group and 13 out of 23 (56.5%) in the nonfiber group (RR 0.15; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.61).

One study in Cara (2021), Caparros (2001), reported diarrhea episodes per 1000 days of enteral nutrition. In the fiber group, they reported 50 episodes, and in the no fiber group 15.8 episodes (RR 3.15; 95% CI 1.89 to 5.27).

- Constipation

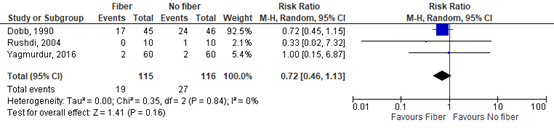

Three studies reported on constipation (Dobb (1990), Rushdi (2004), Yagmurdur (2016)). The pooled RR was 0.72 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.13; Figure 2). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of fiber.

Figure 2: The effect of enteral nutrition with fiber on constipation.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

One study included in Cara (2021), Caparros (2001), reported constipation episodes per 1000 days of enteral nutrition. In the fiber group, they reported 4.7 episodes, and in the no fiber group 15.9 episodes (RR 0.29; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.70).

- Length of ICU stay

Cara (2021) included four studies that reported on length of ICU stay (Caparros (2001), Chittawatanarat (2010), Spapen (2001), Spindler-Vesel (2007)).

The results could not be pooled since limited data was reported.

Caparros (2001) reported a mean days of ICU in the fiber group of 18.58 (SD 11.65) and in the no fiber group 15.1 days (SD 8.3). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of no fiber (MD 3.48; 95% CI 0.64 to 6.32).

Chittawatanarat (2010) reported a mean days of ICU in the fiber group of 16.8 (SD 8) and in the no fiber group 25.5 (SD 13). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of fiber (MD -8.70; 95% CI -15.96 to -1.44).

The studies by Spapen (2001) and Spindler-Vesel (2007) did not report standard deviations. Spapen (2001) reported a nonsignificant difference in length of ICU stay between the fiber and no fiber group. Mean duration in the fiber group and no fiber group was 19 days (range 11 to 51 days) and 17 days (range 10 to 30 days), respectively.

Spindler-Vesel (2007) reported 16 ICU days (range 10 to 21) in the fiber group, 12 ICU days (range 8.5 to 21.3) in the fiber group + lactobacilli, and 14 ICU days (range 8.3 to 23) in the no fiber group. Nonsignificant differences were found (soluble vs. no fiber, P=0.92; soluble + lactobacilli vs. no fiber, P=0.61).

- Mortality

4.1 ICU mortality

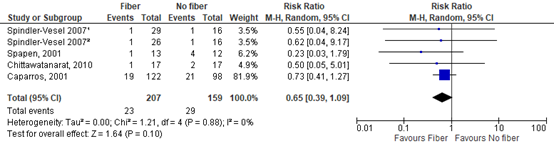

Four studies reported on ICU mortality (Caparros (2001), Chittawatanarat (2010), Spapen (2001), Spindler-Vesel (2007)). The pooled RR was 0.65 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.09; Figure 3). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of the fiber group.

Figure 3: The effect of enteral nutrition with fiber on ICU mortality.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

¹ medical nutrition with guar gum vs. no fiber

² standard formula plus symbiotic supp vs. no fiber

4.2 Long term follow-up of mortality

One study reported on follow-up of more than 29 days on mortality (Caparros (2001)). Long term mortality was reported in 20 out of 122 (16.4%) patients in the fiber group and 31 out of 98 (31.6%) patients in the nonfiber group. The RR was 0.78 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.19) in favor of the fiber group.

- Aspiration

Cara (2021) included two studies that reported on aspiration (Chittawatanarat (2010), Yagmurdur (2016)).

Chittawatanarat (2010) reported aspiration in 0 out of 17 patients in the fiber group and 0 out of 17 patients in the no fiber group (risk difference (RD) 0.00; 95% CI -0.11 to 0.11).

Yagmurdur (2016) reported aspiration in 10 out of 60 patients (16.7%) in the fiber group and 9 out of 60 patients (15.0%) in the no fiber group (RD 0.02; 95% CI -0.11 to 0.15).

One study included in Cara (2021), Caparros (2001), reported bronchial aspiration episodes per 1000 days of enteral nutrition. In the fiber group, they reported 0.7 episodes, and in the no fiber group 0.9 episodes (RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.05 to 12.1).

- Abdominal distention

Cara (2021) included two studies that reported on abdominal distention (Rushdi (2004), Yagmurdur (2016)).

Rushdi (2004) reported abdominal distention in 2 out of 10 patients (20%) in the fiber group and 4 out of 10 patients (40%) in the no fiber group (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.12 to 2.14). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of fiber.

Yagmurdur (2016) reported abdominal distention in 25 out of 60 patients (41.7%) in the fiber group and 18 out of 60 (30%) in the no fiber group (RR 1.39; 95% CI 0.85 to 2.26). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of no fiber.

One study included in Cara (2021), Caparros (2001), reported abdominal distention episodes per 1000 days of enteral nutrition. In the fiber group, they reported 9.3 episodes, and in the no fiber group 11.4 episodes (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.38 to 1.73).

- Vomiting

Two studies reported on vomiting (Rushdi (2004), Yagmurdur (2016)).

Rushdi (2004) reported vomiting in 0 out of 10 patients in the fiber group and 2 out of 10 patients in the no fiber group (RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.01 to 3.70). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of fiber.

Yagmurdur (2016) reported vomiting in 9 out of 60 patients (15.0%) in the fiber group and 10 out of 60 patients (16.7%) in the no fiber group (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.39 to 2.06). This difference was clinically relevant in favor of fiber.

One study included in Cara (2021), Caparros (2001), reported vomiting episodes per 1000 days of enteral nutrition. In the fiber group, they reported 8.7 episodes, and in the no fiber group 11.4 episodes (RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.35 to 1.63).

- Ileus

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure ileus.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of the literature was assessed per outcome, using the GRADE-methodology. Evidence from RCTs started at HIGH certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to moderate, low or very low certainty, in case of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, or publication bias.

Diarrhea

The level of evidence for diarrhea starts high, as the included studies were RCTs. It was downgraded by 2 levels due to study limitations (risk of bias; -1), and conflicting results (inconsistency, -1). Reason of downgrading for bias was due to deviations from intended intervention, bias due to missing outcome data and measurement of the outcome. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure diarrhea is low.

Constipation

The level of evidence for constipation starts high, as the included studies were RCTs. It was downgraded by 2 levels due to study limitations (risk of bias; -1), and imprecision (-1). Reason of downgrading for bias was due to missing outcome data and measurement of the outcome. Reason of downgrading for imprecision was overlap with the threshold for clinical relevance. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure of constipation is low.

Length of ICU stay

The level of evidence for length of ICU starts high, as the included studies were RCTs. It was downgraded by 3 levels due to study limitations (risk of bias; -1), conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and imprecision (-1). Reason of downgrading for bias was missing outcome data. Reason of downgrading for imprecision was overlap with the threshold for clinical relevance. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure length of ICU stay is very low.

ICU mortality

The level of evidence for ICU mortality starts high, as the included studies were RCTs. It was downgraded by 3 levels due study limitations (risk of bias; -1), and imprecision (-2). Reason of downgrading for bias was deviations from intended intervention and bias in the measurement of the outcome. Reason of downgrading for imprecision was overlap with the threshold for clinical relevance and a low number of events and patients per study. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure of ICU mortality is very low.

Long-term follow-up of mortality

The level of evidence for long-term follow-up of mortality starts high, as the included studies were RCTs. It was downgraded by 3 levels due to study limitations (risk of bias; -1), and imprecision (-2). Reason of downgrading for bias was deviations from intended intervention and bias the measurement of the outcome. Reason of downgrading for imprecision was overlap with the threshold(s) for clinical relevance and a low number of events and patients per study. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure of long-term follow-up of mortality is very low.

Aspiration

The level of evidence for aspiration starts high, as the included studies were RCTs. It was downgraded by 2 levels due to study limitations (risk of bias; -1), imprecision (-1). The 95%CI of the effect estimate did not cross the threshold for clinical relevance, but number of events was very low. This was the reason that we downgraded for imprecision. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure aspiration is low.

Abdominal distention

The level of evidence for abdominal distention starts high, as the included studies were RCTs. It was downgraded by 3 levels due to conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and imprecision (-2). The 95% CI of the effect estimate crossed both thresholds for clinical relevance and the number of events was low. This was the reason that we downgraded for imprecision. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure abdominal distention is very low.

Vomiting

The level of evidence for abdominal distention starts high, as the included studies were RCTs. It was downgraded by 3 levels due to conflicting results (inconsistency, -1) and imprecision (-2). The 95% CI of the effect estimate crossed both thresholds for clinical relevance, and the number of events was low. This was the reason that we downgraded for imprecision. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure vomiting is very low.

Ileus

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure ileus.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)favorable effects of adding fiber compared to not adding fiber to the diet of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU)?

| P (Patients): | Patients admitted to the ICU |

| I (Intervention): | Soluble, insoluble and mixed fiber diet |

| C (Comparison): | No fiber enriched diet |

| O (Outcomes): | Incidence of diarrhea, incidence of constipation, length of ICU stay, mortality, ileus, aspiration, vomiting, abdominal distension |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered incidence of diarrhea and incidence of constipation as critical outcome measures for decision making; and length of ICU stay, mortality, ileus, aspiration, vomiting and abdominal distention as important outcome measures for decision making.

The guideline development group defined the following as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference:

Incidence of diarrhea, incidence of constipation: a 10% difference in relative risk: 0.91≤RR≥1.10 or -0.10≤RD≥0.10

Length of ICU stay: >1 day

Mortality: a 5% difference relative risk: 0.95≤RR≥1.05

Ileus, bronchial aspiration, vomiting, abdominal distension: a 10% difference in relative risk: 0.91≤RR≥1.10 or -0.10≤RD≥0.10

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 01-02-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 215 hits. Fourteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, twelve studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included.

Results

One systematic review included in the analysis of the literature (Cara, 2021). Ten RCTs (out of 19) from the systematic review were included as they met the inclusion criteria. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Belknap D, Davidson LJ, Smith CR. The effects of psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid on diarrhea in enterally fed patients. Heart Lung. 1997 May-Jun;26(3):229-37. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90060-1. PMID: 9176691.

- Caparrós T, Lopez J, Grau T. Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients with a high-protein diet enriched with arginine, fiber, and antioxidants compared with a standard high-protein diet. The effect on nosocomial infections and outcome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2001 Nov-Dec;25(6):299-308; discussion 308-9. doi: 10.1177/0148607101025006299. PMID: 11688933.

- Cara KC, Beauchesne AR, Wallace TC, Chung M. Safety of Using Enteral Nutrition Formulations Containing Dietary Fiber in Hospitalized Critical Care Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2021 Jul;45(5):882-906. doi: 10.1002/jpen.2210. Epub 2021 Jul 26. PMID: 34165812.

- Chittawatanarat K, Pokawinpudisnun P, Polbhakdee Y. Mixed fibers diet in surgical ICU septic patients. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19(4):458-64. PMID: 21147705.

- Dobb GJ, Towler SC. Diarrhoea during enteral feeding in the critically ill: a comparison of feeds with and without fibre. Intensive Care Med. 1990;16(4):252-5. doi: 10.1007/BF01705161. PMID: 2162867.

- Emery EA, Ahmad S, Koethe JD, Skipper A, Perlmutter S, Paskin DL. Banana flakes control diarrhea in enterally fed patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 1997 Apr;12(2):72-5. doi: 10.1177/011542659701200272. PMID: 9155405.

- Rushdi TA, Pichard C, Khater YH. Control of diarrhea by fiber-enriched diet in ICU patients on enteral nutrition: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2004 Dec;23(6):1344-52. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.04.008. PMID: 15556256.

- Spapen H, Diltoer M, Van Malderen C, Opdenacker G, Suys E, Huyghens L. Soluble fiber reduces the incidence of diarrhea in septic patients receiving total enteral nutrition: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2001 Aug;20(4):301-5. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2001.0399. PMID: 11478826.

- Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Alhazzani W, Calder PC, Casaer MP, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):48-79.

- Spindler-Vesel A, Bengmark S, Vovk I, Cerovic O, Kompan L. Synbiotics, prebiotics, glutamine, or peptide in early enteral nutrition: a randomized study in trauma patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2007 Mar-Apr;31(2):119-26. doi: 10.1177/0148607107031002119. PMID: 17308252.

- Tuncay P, Arpaci F, Doganay M, Erdem D, Sahna A, Ergun H, Atabey D. Use of standard enteral formula versus enteric formula with prebiotic content in nutrition therapy: A randomized controlled study among neuro-critical care patients. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018 Jun;25:26-36. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.03.123. Epub 2018 Mar 30. PMID: 29779815.

- Yagmurdur H, Leblebici F. Enteral nutrition preference in critical care: fibre-enriched or fibre-free? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016 Dec;25(4):740-746. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.122015.12. PMID: 27702716.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What is the role of adding fiber to the nutritional treatment of patients in the ICU?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Cara, 2021

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to [month/year]

A: Belknap, 1997 B: Caparros, 2001 C: Chittawatanarat,2010 D: Dobb, 1990 E: Emery, 1997 F: Rushdi, 2004 G: Schultz, 2000 H: Spapen, 2001 I: Spindler-Vesel 2007 J: Tuncay 2018 K: Xi, 2017 L: Yagmurdur, 2016

Setting and Country: Tufts University, USA Source of funding: unrestricted educational grant from Nestlé Health Science to Think Healthy Group Conflicts of interest: None

|

Inclusion criteria SR: -100% ICU patients or critically ill patients -No disease restriction

Exclusion criteria SR: Articles not published in peer-reviewed journals, including unpublished data, manuscript reports, abstracts, pre-prints, and conference proceedings -Languages other than English -Non-ICU patients or non- critically ill patients

Twelve studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients: ranged in size from 30 to 398 participants Age: ranged from 18 to 93 years N (number of patients analyzed), mean age A: n=60, 65 (IQR:7.53, 12.65) B: n=220, 54.12 [34–69] C: n=34, 50.55 (IQR: 17.4-20.5) D: n=91, 46 (SD:19) E: n=31, range (41-87) F: n=20, 57.5 (IQR: 12-14) G: n=44, 65.6 (SD:16.3) H: n=25, 68 (SD:11.15) I: n=113, 41.0 (18.9) J: n=46, 72.85 (IQR:15.3-20) K: n=125, 48.4 (IQR:10.7-13.7) L: n=120, 70.5 (14-15)

Sex: % Male A: 96.7 B: 72.3 C: 35.3 D: 67.0 E: not reported F: 55.0 G: 54.5 H: 52.0 I: 77.9 J: 50.0 K: 56.8 L: 41.7

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported

|

Describe intervention:

A: fiber-free formula plus psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid (CPHM: continuous vs BPHM: bolus); 14 g/day, soluble B: multifiber formula (Arabic gum, cellulose, FOS, inulin, resistant starch, and soy polysac- charides) enriched with vitamins; 8.9 g/L, soluble and insoluble C: mixed-fiber formula containing yellow pea fiber (pectin, cellulose, lignin, hemi- celluloses) mixed with FOS; 15.1 g/L, soluble and insoluble (∼1:1) D: iso-osmolar lactose-free feed with soy polysaccha- ride (methylcellu- lose); 21 g/L, soluble E: Group B: full-strength, lactose-free, fiber-free formulas plus pectin from banana F: guar gum– enriched enteral feeds; 22 g/L, soluble G: Fiber/pectin: fiber formula plus pectin; 174 g/day, soluble and insoluble Fiber/placebo: fiber formula with gelatin placebo; 190 g/day, soluble and insoluble H: Soluble fiber: entral formula with partially hydrolyzed guar supp; 22 g/L, soluble I: Group B: medical nutrition with fermentable guar gum; 22 g/L, soluble Group D: standard nonfiber peptide formula Cumulative infections: D <A=C<B(P=.02 for all groups; NR for individual comparisons) formula plus synbiotic supp (β-glucan, inulin, pectin, and resistant starch); 100 g/L, soluble J: EFPC: enteral formula fortified with prebiotic (FOS); 5.3 g/day total diet fiber with 3.5 g/day FOS [range, 2.5 ± 0.2 g/day to 12.9 ± 2.4 g/day], soluble K: PEC/EN: EN with pectin supp dissolved in water; 24 g/day (days 2–6), soluble L: FE: fiber- enriched nutrition solution with α-cellulose, Arabic gum, inulin, FOS, soy polysac- charides, and resistant starch; 15 g/L, soluble and insoluble (0.7 g/100 ml and 0.8 g/100 ml, respectively)

|

Describe control:

A: fiber-free formula B: fiber-free formula not enriched with vitamins C: standard formula without combined fiber D: iso-osmolar lactose-free feed without soy polysac- charide E: Group A: full-strength, lactose-free, fiber-free formulas plus routine medical treatment for diarrhea F: fiber-free enteral feeds G: Fiber- free/pectin: fiber-free formula with pectin Fiber- free/placebo: fiber-free formula with gelatin placebo H: Control: isocaloric isonitroge- nous control feed without fiber I: Group A: standard nonfiber formula Group C: nonfiber peptide formula J: SEF: standard enteral formula K: EN: EN without pectin L: FF: fiber-free nutrition solution

|

Intervention/exposure duration; longest follow-up (days):

A: 7;7 B: Median [IQR]: study diet =10 [6–18], control diet = 9 [6–14]; 7 (follow-up for mortality at 6 months) C: 5–14; 14 D: 3–18; 15 E: Average: group A = 5.24 ± 1.52, group B=4.93± 1.00; 7 F: 4; 4 G: 6;8 H: Mean: soluble fiber group =11±4, control group = 12 ±5;21 I: Not reported;7 J: Not reported;21 K: 6; 30 L: 5; 5

|

Outcome measure-1

Diarrhea events (hart and Dobb scale) Effect measure: RR. [95% CI]:

C: 1+ day diarrhea score >12 0.50 (0.18-1.35) D: Patients with diarrhea score >12 1.26 (0.69-2.31) E: Diarhea on last study day 0.56 (0.29-1.08) G: 2+ days of diarrhea scores >12 (fiber/nonfiber + placebo) 6.0 (0.86-41.96) H: At least 1 day with diarrhea 0.50 (0.27-0.93) L: At least 1 day with diarrhea 0.58 (0.39-0.85)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.65 [95% CI 0.46 to 0.90] favoring the fiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 35%

Diarrhea events (other scales than the hart and Dobb scale) Effect measure: RR. [95% CI]:

A: 0.71 (0.30-1.70) J: 0.15 (0.04-0.61) K: 0.44 (0.20-1.01)

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): 0.42 95% CI [0.20 to 0.90] favoring the fiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 44%

Outcome measure-3 Incidence of constipation Effect measure: RR. [95% CI]:

D: 0.72 (0.45-1.15) F: 0.33 (0.02-7.32) K: 0.29 (0.06-1.34) L: 1.00 (0.15-6.87)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.67 95% CI (0.44-1.04) favoring the fiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-4 Bronchial aspiration Effect measure: RR. [95% CI]:

C: not estimable K: 0.60 (0.15-2.44) L: 1.11 (0.49-2.54)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.95 95% CI (0.47-1.93) favoring the fiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-5 Mortality

ICU mortality Effect measure: RR. [95% CI]:

B: 0.73 (0.41-1.27) C: 0.50 [0.05. 5.0) H: 0.23 (0.03. 1.79)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.66 95% CI (0.39-1.12) favoring the fiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Long term follow-up of mortality

B: 0.78 (0.51-1.19) K: 0.34 (0.04-3.17) Freedberg (see table below) 0.50 (0.12-2.14)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.73 95% CI (0.49-1.09) favoring the fiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-6 Abdominal distention Effect measure: RR. [95% CI]:

F: 0.50 (0.12- 2.14) K: 0.81 (0.23-2.89) L: 1.39 (0.85-2.26)

Pooled effect (random effects model: 1.16 95% CI (0.72-1.87) favoring the nonfiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 6%

Outcome measure-7 Vomiting Effect measure: RR. [95% CI]:

F: 0.20 (0.01-3.70) K: 0.68 (0.12-3.92) L: 0.90 (0.39-2.06)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.78 95% CI (0.38-1.61) favoring the nonfiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-8 Length of ICU stay Mean difference 95% CI: B: 3.48 (0.64-6.32) K:-4.10 (-7.31—0.89)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.65 95% CI (0.46-0.90) favoring the fiber group

Heterogeneity (I2): 35%

Outcome measure-9 ileus No data available

|

Author’s conclusion: EN formulas with fiber may help reduce incidence and severity of diarrhea and GI complications overall in critically ill patients, without increased risk of other adverse events

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained (subgroupanalysis) |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question: What is the role of adding fiber to the nutritional treatment of patients in the ICU?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Freedberg, 2020

|

Type of study: open label RCT

Setting and country: Columbia University Medical Center, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Dr. Freedberg was funded in part by NIH K23 DK111847 and by a Department of Defense Peer-Reviewed Medical Research Program Clinical Trial Award. Dr. Abrams was funded in part by NIH U54 |

Inclusion criteria: Adults 18-years-old or more at the time of medical ICU admission who received 3 or more days of enteral nutrition and had received a broad-spectrum IV antibiotic for sepsis within the previous 24 hours.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they lacked capacity and had no health surrogate, had surgery involving the intestinal lumen within 30 days, or had limited treatment goals (i.e., do not resuscitate/do not intubate).

N total at baseline:n=20 Intervention: n=10 Control:n=10

Important prognostic factors2: age (tertiles) I:<50 (40%), 50-70 (40%), >70 (20%) C: <50 (30%), 50-70 (30%), >70 (40%)

Sex: I: 50% M C: 70 % M

BMI: median (IQR) I: 26.5 (IQR: 23.5-31.2) C: 24.2 (IQR:19.1-28.5)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Mixed soy- and oat-derived fiber (14.3 g fiber/L)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Calorie- and micronutrient-identical enteral nutrition with 0 g/L fiber

|

Length of follow-up:

30 days

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Effect measure: RR, [95% CI]:

Mortality 0.50 (0.12-2.14)

|

Author’s conclusion: no differences in deaths between the fiber and no fiber group.

Personal comments: very small study with 10 patients in each arm. Study was not powered to detect difference in mortality between the intervention and control group.

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Table of quality assessment for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Cara, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes (none) |

Table of quality assessment for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason of exclusion |

|

Maruyama M, Goshi S, Kashima Y, Mizuhara A, Higashiguchi T. Clinical Effects of a Pectin-Containing Oligomeric Formula in Tube Feeding Patients: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020 Jun;35(3):464-470. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10392. Epub 2019 Oct 13. PMID: 31606903. |

Not conform PICO (P)

|

|

Chittawatanarat K, Surawang S, Simapaisan P, Judprasong K. Jerusalem Artichoke Powder Mixed in Enteral Feeding for Patients Who have Diarrhea in Surgical Intensive Care Unit: A Method of Preparation and a Pilot Study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020 Nov;24(11):1051-1056. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23575. PMID: 33384510; PMCID: PMC7751032. |

Not conform PICO (C) |

|

Sripongpun P, Lertpipopmetha K, Chamroonkul N, Kongkamol C. Diarrhea in tube-fed hospitalized patients: Feeding formula is not the most common cause. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep;36(9):2441-2447. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15484. Epub 2021 Mar 20. PMID: 33682192. |

Not conform PICO (P) |

|

Nasimi, S, Aberoomand, L, Mousavi-Shirazifard, Z, Masjedi, M, Nikbakht jam, I, Sabetian, G, Zand, F, Edrisi, F (2018). Evaluation of Patient's Energy Intake between Different Types of Formulas in the First Week of Starting Enteral Feeding in Intensive Care Unit Patients. Razavi International Journal of Medicine, 6(3), 31-35. doi: 10.30483/rijm.2018.21 |

Wrong study design (prospective observational study) |

|

Nakamura K, Inokuchi R, Fukushima K, Naraba H, Takahashi Y, Sonoo T, Hashimoto H, Doi K, Morimura N. Pectin-containing liquid enteral nutrition for critical care: a historical control and propensity score matched study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2019;28(1):57-63. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.201903_28(1).0009. PMID: 30896415. |

Wrong study design (retrospective case control study) |

|

Fu Y, Moscoso DI, Porter J, Krishnareddy S, Abrams JA, Seres D, Chong DH, Freedberg DE. Relationship Between Dietary Fiber Intake and Short-Chain Fatty Acid-Producing Bacteria During Critical Illness: A Prospective Cohort Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020 Mar;44(3):463-471. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1682. Epub 2019 Aug 6. PMID: 31385326; PMCID: PMC7002227. |

Wrong study design (retrospective observational study) |

|

Pérez-Sánchez J, Fernández-Boronat J, Martínez-Méndez E, Marín-Cagigas ML, Mota-Puerto D, Pérez-Román MC, Martínez-Estalella G. Evaluation and handling of constipation in critical patients. Enferm Intensiva. 2017 Oct-Dec;28(4):160-168. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.enfi.2017.01.001. Epub 2017 Jun 7. PMID: 28601441. |

Wrong study design (observational study) |

|

Kamarul Zaman M, Chin KF, Rai V, Majid HA. Fiber and prebiotic supplementation in enteral nutrition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015 May 7;21(17):5372-81. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5372. PMID: 25954112; PMCID: PMC4419079. |

Not conform PICO (P) |

|

Reis AMD, Fruchtenicht AV, Loss SH, Moreira LF. Use of dietary fibers in enteral nutrition of critically ill patients: a systematic review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018 Jul-Sept;30(3):358-365. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20180050. PMID: 30328989; PMCID: PMC6180475. |

Not the most recent SR |

|

Chittawatanarat K, Pokawinpudisnun P, Polbhakdee Y. Mixed fibers diet in surgical ICU septic patients. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010;19(4):458-64. PMID: 21147705. |

Included in the SR of Cara |

|

Xi F, Xu X, Tan S, Gao T, Shi J, Kong Y, Yu W, Li J, Li N. Efficacy and safety of pectin-supplemented enteral nutrition in intensive care: a randomized controlled trial. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26(5):798-803. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.082016.07. PMID: 28802288. |

Included in the SR of Cara |

|

Yagmurdur H, Leblebici F. Enteral nutrition preference in critical care: fibre-enriched or fibre-free? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016 Dec;25(4):740-746. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.122015.12. PMID: 27702716. |

Included in the SR of Cara |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-03-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 05-03-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de

samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten die gevoed worden op de intensive care.

Werkgroep

dr. R. (Robert) Tepaske, intensivist, (voorzitter) NVIC

Prof. dr. A.R.H. (Arthur) van Zanten, intensivist, NVIC

dr. M.C.G. (Marcel) van de Poll, intensivist, NVIC

drs. B. (Ben) van der Hoven, internist, NIV

drs. E.J. (Lisa) Mijzen, anesthesioloog-intensivist, NVA

dr. F.J. (Jeannette) Schoonderbeek, chirurg-intensivist, NVvH

L. (Lea) van Duijvenbode - den Dekker, MSc, intensive care verpleegkundige, V&VN Intensive Care

M. (Manon) Mensink, diëtist, NVD

Ir. S. (Suzanne) ten Dam, diëtist, NVD

I. (Idske) Dotinga, ervaringsdeskundige, FCIC/IC Connect

Klankbordgroep

Mevr. E.R. (Elske) van Liere, logopedist, NVLF

Met ondersteuning van

Dr. F. Willeboordse, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

I. van Dijk, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Achternaam werkgroeplid |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen |

Persoonlijke relaties |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie |

Overige belangen |

Actie |

|

* Voorzitter werkgroep Tepaske |

Anesthesioloog-Intensivist Begeleider Nurse practitioners profielen circulation & ventilation apotheek |

Allen onbezoldigd:

|

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

Eenmalig vergoeding voor deelname aan masterclass 'meten van metabolisme' van Hamilton, Zwitserland |

Geen actie vereist. |

|

Van Zanten |

lnternist-intensivist |

Onbetaald: |

Geen aandelen, opties, patenten of producten |

Echtgenote leidt Congres- en Organisatiebureau Interactie dat voor vele wetenschappelijke |

Precise trial (MUMC+), MC RCT, ZonMW/KCE NL/Belgie. studie naar hoog-eiwit vs. normaal eiwit voor |

richtlijnmaker van ESPEN richtlijn |

geen |

Besproken tijdens werkgroepvergadering. We verwachten geen adviezen te geven over individuele producten (en mogelijk dus bepaalde fabrikanten). Zodra er wel modules worden uitgewerkt waarin specifieke aanbevelingen en / of adviezen worden gegeven t.a.v. bepaalde producten zal dit worden gedaan door andere werkgroepleden. Dhr. van Zanten zal dan niet participeren als trekker en bij het opstellen van aanbevelingen. |

|

Mensink |

Diëtist Rijnstate Arnhem |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

Geen actie vereist. |

|

Schoonderbeek |

Chirurg-intensivist staflid Intensive Care |

medisch adviseur, freelance |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

Mevr. Schoonderbeek werkt als freelance medisch adviseur voor Veduma in Zaltbommel. Ze adviseert voornamelijk in letselschade zaken (na aanrijdingen e.d.). Dit heeft nooit iets met voeding te maken. Waardoor geen restricties hoeven worden opgelegd. |

|

Van Duijvenbode-Den Dekker |

Intensive care verpleegkundige - Amphia ziekenhuis Breda |

Visitatie commissie NVIC via V&VN IC |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

Geen actie vereist. |

|

Mijzen |

Anesthesioloog- Intensivist Beatrix ziekenhuis Gorinchem |

FCCS- instructeur, betaald Bestuurslid sectie IC-NVA, onbetaald. |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

Geen actie vereist. |

|

Dotinga |

Functienaam: Trainee beleid en management in zorg en welzijn |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

nvt |

|

Geen actie vereist. |

|

van de Poll |

Chirurg-intensivist, Staflid Maastricht UMC |

geen |

geen |

geen |

Contractant:ZONMW (Doelmatigheid): INCEPTION trial (multicenter RCT naar ECPR bij OHCA), ZONMW/KCE (BeNeFIT) PRECISe trial (multicenter RCT naar hoog vs normaal eiwit in enterale voeding bij IC patienten), Fresenius-kabi: traceronderzoek naar glutaminemetabolisme in sepsis, Cytosorb CYTATION trial (single center RCT naar gebruik van cytosorb bij vasoplegie), Getinge: co-financiering INCEPTION trial, Nutricia:co-financiering (in-kind) PRECISe trial, NUTRICIA research foundation/Nestle ESICM research grant: single center RCT naar elementaire voeding bij diarree. Consultancy Bayer R&D (data based algorithm development in ARDS) |

geen |

geen |

Besproken tijdens werkgroepvergadering. We verwachten geen adviezen te geven over individuele producten (en mogelijk dus bepaalde fabrikanten). Zodra er wel modules worden uitgewerkt waarin specifieke aanbevelingen en / of adviezen worden gegeven t.a.v. bepaalde producten zal dit worden gedaan door andere werkgroepleden. Dhr. van der Poll zal dan niet participeren als trekker en bij het opstellen van aanbevelingen. |

|

van der Hoven |

Internist-intensivist, staflid IC Volwassenen, Erasmus MC te Rotterdam |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

geen |

Geen actie vereist. |

|

ten Dam |

Diëtist-onderzoeker OPRAH studie, Amsterdam UMC |

Bestuurslid NVO (Nederlandse Voedingsteam Overleg), onbetaald. Docent Focus op Voeding, VBNU, betaald, Docent Master Health Sciences, VU, onbetaald.

|

geen |

geen |

OPRAH_CT studie; RCT effect sarcopenie op fysiek functioneren. Subsidie AMS. OPRAH_PRO studie; haalbaarheidsstudie OPRAH RCT. Subsidie CCA. |

geen |

geen |

Geen actie vereist. |

|

van Liere |

Logopedist, Adrz |

nvt |

Logopedist in dienst van ziekenhuis, o.a. ICU |

nvt |

nvt |

Nvt |

nvt |

Geen actie vereist. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van FCIC/IC Connect voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie, en afvaardiging van FCIC/IC Connect in de werkgroep. Het verslag van de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie [zie aanverwante producten] is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan FCIC/IC Connect en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Vezels |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en/of het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die voeding op de intensive care krijgen. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door relevante partijen via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en deze worden daarom meegewogen. Voorbeelden zijn: Aanvullende argumenten uit de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’. Deze overwegingen kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag. Zij zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt van toepassing zijn.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: Alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur) zijn in de overwegingen meegenomen. Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

Algemene informatie

|

Richtlijn: Voeding op de IC |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: Wat is de plaats van het toevoegen van vezels aan de voedingsbehandeling van patiënten op de IC? |

|

|

Database(s): Ovid/Medline, Embase |

Datum: 01-02-2022 |

|

Periode: 2010 - heden |

Talen: Engels, Nederlands |

|

BMI-zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting:

|

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

75 |

11 |

76 |

|

RCT |

60 |

27 |

63 |

|

Observationele studies |

70 |

11 |

76 |

|

Totaal |

205 |

49 |

215 |

Zoekstrategie

Embase

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#16 |

#13 OR #14 OR #15 |

205 |

|

#15 |

#9 AND #12 NOT (#13 OR #14) = observationeel |

70 |

|

#14 |

#9 AND #11 NOT #13 = RCT |

60 |

|

#13 |

#9 AND #10 = SR |

75 |

|

#12 |

'comparative study'/exp OR 'control group'/de OR 'controlled study'/de OR 'controlled clinical trial'/de OR 'crossover procedure'/de OR 'double blind procedure'/de OR 'phase 2 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 3 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 4 clinical trial'/de OR 'pretest posttest design'/de OR 'pretest posttest control group design'/de OR 'quasi experimental study'/de OR 'single blind procedure'/de OR 'triple blind procedure'/de OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 trial):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 (study OR studies)):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/1 active):ti,ab,kw) OR 'open label*':ti,ab,kw OR (((double OR two OR three OR multi OR trial) NEAR/1 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((allocat* NEAR/10 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR placebo*:ti,ab,kw OR 'sham-control*':ti,ab,kw OR (((single OR double OR triple OR assessor) NEAR/1 (blind* OR masked)):ti,ab,kw) OR nonrandom*:ti,ab,kw OR 'non-random*':ti,ab,kw OR 'quasi-experiment*':ti,ab,kw OR crossover:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross over':ti,ab,kw OR 'parallel group*':ti,ab,kw OR 'factorial trial':ti,ab,kw OR ((phase NEAR/5 (study OR trial)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((case* NEAR/6 (matched OR control*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((match* NEAR/6 (pair OR pairs OR cohort* OR control* OR group* OR healthy OR age OR sex OR gender OR patient* OR subject* OR participant*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((propensity NEAR/6 (scor* OR match*)):ti,ab,kw) OR versus:ti OR vs:ti OR compar*:ti OR ((compar* NEAR/1 study):ti,ab,kw) OR (('major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR 'observational study'/de OR 'cross-sectional study'/de OR 'multicenter study'/de OR 'correlational study'/de OR 'follow up'/de OR cohort*:ti,ab,kw OR 'follow up':ti,ab,kw OR followup:ti,ab,kw OR longitudinal*:ti,ab,kw OR prospective*:ti,ab,kw OR retrospective*:ti,ab,kw OR observational*:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross sectional*':ti,ab,kw OR cross?ectional*:ti,ab,kw OR multicent*:ti,ab,kw OR 'multi-cent*':ti,ab,kw OR consecutive*:ti,ab,kw) AND (group:ti,ab,kw OR groups:ti,ab,kw OR subgroup*:ti,ab,kw OR versus:ti,ab,kw OR vs:ti,ab,kw OR compar*:ti,ab,kw OR 'odds ratio*':ab OR 'relative odds':ab OR 'risk ratio*':ab OR 'relative risk*':ab OR 'rate ratio':ab OR aor:ab OR arr:ab OR rrr:ab OR ((('or' OR 'rr') NEAR/6 ci):ab))) OR 'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'comparative study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

14550467 |

|

#11 |

'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR random*:ti,ab OR (((pragmatic OR practical) NEAR/1 'clinical trial*'):ti,ab) OR ((('non inferiority' OR noninferiority OR superiority OR equivalence) NEAR/3 trial*):ti,ab) OR rct:ti,ab,kw |

1839814 |

|

#10 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

733409 |

|

#9 |

#6 AND #7 AND #8 AND ([english]/lim OR [dutch]/lim) AND [2010-2022]/py NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

380 |

|

#8 |

'enteric feeding'/exp OR (((enteral OR enteric) NEAR/3 (feeding OR nutrition)):ti,ab,kw) |

43740 |

|

#7 |

'dietary fiber'/exp OR fiber*:ti,ab,kw OR 'ispagula'/exp OR 'ispagula':ti,ab,kw OR psyllium:ti,ab,kw OR 'pectin'/exp OR pectin*:ti,ab,kw OR 'inulin'/exp OR inulin*:ti,ab,kw OR 'resistant starch'/exp OR (((resistant OR alant) NEAR/3 starch*):ti,ab,kw) OR 'guar gum'/exp OR guar:ti,ab,kw OR guaran:ti,ab,kw OR 'cellulose'/exp OR cellulose:ti,ab,kw OR 'lignin'/exp OR lignin*:ti,ab,kw OR 'hemicellulose'/exp OR 'hemicellulose':ti,ab,kw OR 'fructose oligosaccharide'/exp OR 'fructo* oligosaccharide':ti,ab,kw OR fos:ti,ab,kw OR fructooligosaccharide:ti,ab,kw OR oligofructose:ti,ab,kw |

525329 |

|

#6 |

'critically ill patient'/exp OR 'intensive care'/exp OR 'intensive care unit'/exp OR 'critical illness'/exp OR (((intensive OR critical*) NEAR/3 (care OR patient* OR ill*)):ti,ab,kw) OR icu:ti,ab,kw OR 'pneumonia'/exp OR 'burn'/exp OR 'respiratory failure'/exp OR 'head injury'/exp OR 'pancreatitis'/exp OR pneumonia:ti,ab,kw OR burn*:ti,ab,kw OR pancreatitis:ti,ab,kw OR trauma:ti,ab,kw OR injur*:ti,ab,kw OR failure*:ti,ab,kw OR severe:ti,ab,kw |

5185657 |

|

# |

Searches |

Results |

|

12 |

9 or 10 or 11 |

49 |

|

11 |

(5 and 8) not (9 or 10) = observationeel |

11 |

|

10 |

(5 and 7) not 9 = RCT |

27 |

|

9 |

5 and 6 = SR |

11 |

|

8 |

controlled clinical trial/ or Control groups/ or Cross-Over Studies/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or (((control or controlled) adj6 trial) or ((control or controlled) adj6 study) or ((control or controlled) adj1 active) or "open label*" or ((double or two or three or multi or trial) adj (arm or arms)) or (allocat* adj10 (arm or arms)) or placebo* or "sham-control*" or ((single or double or triple or assessor) adj1 (blind* or masked)) or nonrandom* or "non-random*" or "quasi-experiment*" or crossover or "cross over" or "parallel group*" or "factorial trial").ti,ab,kf. or clinical trial, phase ii/ or clinical trial, phase iii/ or clinical trial, phase iv/ or (phase adj5 (study or trial)).ti,ab,kf. or (Case-Control Studies/ or Matched-Pair Analysis/ or ((case* adj6 (matched or control*)) or (match* adj6 (pair or pairs or cohort* or control* or group* or healthy or age or sex or gender or patient* or subject* or participant*))).ti,ab,kf. or (propensity adj6 (scor* or match*)).ti,ab,kf.) or ((exp cohort studies/ or observational study/ or cross-sectional studies/ or multicenter study/ or (cohort* or 'follow up' or followup or longitudinal* or prospective* or retrospective* or observational* or cross sectional* or cross?ectional* or multicent* or 'multi-cent*' or consecutive*).ti,ab,kf.) and ((group or groups or subgroup* or versus or vs or compar*).ti,ab,kf. or ('odds ratio*' or 'relative odds' or 'risk ratio*' or 'relative risk*' or aor or arr or rrr).ab. or (("OR" or "RR") adj6 CI).ab.)) or (versus or vs or compar*).ti. or Comparative study/ or (compar* adj study).ti,ab,kf. or historically controlled study/ or Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or cohort*.tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ |

6714422 |

|

7 |

exp randomized controlled trial/ or random*.ti,ab,kf. or ((pragmatic or practical) adj clinical trial*).ti,ab,kf. or ((non-inferiority or noninferiority or superiority or equivalence) adj3 trial*).ti,ab,kf. or rct.ti,ab,kf. |

1426020 |

|

6 |