Beweging/lichamelijke activiteit bij vermoeidheid bij kanker

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de effecten van beweging/lichamelijke training op vermoeidheid, kwaliteit van leven en (fysiek) functioneren in vergelijking met geen beweging/lichamelijke training bij patiënten met vermoeidheid bij kanker in de palliatieve fase?

Aanbeveling

Bij patiënten met vermoeidheid bij kanker in de palliatieve fase:

- Adviseer patiënten dagelijks te bewegen op geleide van de individuele fysieke mogelijkheden en de adviezen in de Nederlandse Norm Gezond Bewegen.

- Overweeg een verwijzing naar een fysiotherapeut voor een aerobe bewegingsinterventie in geval van vermoeidheid en functionele beperking bij inspanning in de vroege periode van ziektegerichte palliatie.

- Verwijs bij voorkeur naar een fysiotherapeut met specifieke kennis, ervaring en vaardigheden die is opgenomen in de Verwijsgids Kanker.

- Adviseer voeding met voldoende calorieën, eiwit en overige voedingsstoffen ter ondersteuning van de bewegingsinterventie. Overweeg een verwijzing naar een diëtist, opgenomen in de Verwijsgids Kanker, voor ondersteuning van de beweeginterventie met gezonde en eiwitrijke voeding.

- Overweeg een verwijzing naar een revalidatiearts in geval van vermoeidheid en complexe functionele beperking (meervoudige problematiek) in de vroege periode van ziektegerichte palliatie.

Overwegingen

Vanuit de beschreven literatuur is het niet mogelijk om een eenduidig antwoord te geven op de vraag of beweging/lichamelijke training een gunstig effect heeft op vermoeidheid, kwaliteit van leven en functioneren bij patiënten met kanker in de palliatieve fase. Belangrijke knelpunten zijn de grote heterogeniteit in de bestudeerde interventies, zowel wat betreft type als duur en intensiteit. Daarnaast hebben veel studies, mede door voortijdig uitval, onvoldoende power bereikt, dan wel zijn meerdere studies opgezet als pilot studie. Ook hebben de meeste studies vermoeidheid niet als inclusiecriterium gebruikt, waardoor niet alle patiënten bij start matig-ernstig vermoeid waren.

In zo’n 30-50% van de studies is er een significant effect gevonden van beweging/lichamelijk activiteit op vermoeidheid, kwaliteit van leven en fysiek functioneren. Een Cochrane review naar het effect van bewegingstherapie tijdens en na een, veelal in opzet curatieve, behandeling van kanker toonde een positief effect van met name fysieke training op vermoeidheid [Cramp 2012].

Een andere Cochrane review toonde een positief effect van een bewegingsinterventie op kwaliteit van leven in een heterogene groep patiënten tijdens actieve behandeling van kanker [Mishra 2012]. Deze review bevatte zowel studies die verricht zijn in de curatieve als de palliatieve setting.

De richtlijn Medische Specialistische Revalidatie bij Oncologie adviseert bewegingstherapie bij patiënten tijdens en na in opzet curatieve behandeling. De richtlijn sluit daarbij aan bij de adviezen van de American College of Sports Medicine [Schmitz 2010]. Met de hedendaagse oncologische behandelingen kan de periode van ziektegerichte palliatie vele jaren duren. Vanwege de genoemde beperkingen van de beschreven studies is het niet mogelijk alleen de studies te selecteren in een vroege ziektegerichte periode van de palliatieve fase. De werkgroep is dan ook van mening dat extrapolatie van de richtlijn Medisch specialistische revalidatie te verdedigen is voor patiënten met vermoeidheid in de vroege periode van de ziektegerichte palliatie. Voor patiënten met vermoeidheid en functionele beperking op het gebied van inspanning, zoals bijvoorbeeld lopen of traplopen, adviseert de werkgroep aerobe training; voor patiënten met meervoudige problematiek verwijzing naar een revalidatiearts. Daarnaast adviseert de werkgroep patiënten om dagelijks te bewegen op geleide van de individuele fysieke mogelijkheden en de adviezen in de Nederlandse Norm Gezond Bewegen. De werkgroep adviseert te verwijzen naar hulpverleners met specifieke kennis, ervaring en vaardigheden; zij zijn (deels) opgenomen in de Verwijsgids Kanker.

Ter ondersteuning van een beweeginterventie of lichamelijke activiteit adviseert de werkgroep gebruik te maken van gezonde voeding. Specifieke adviezen voor energie, koolhydraten, eiwit en vitamine D bij beweging en training zijn terug te vinden in de richtlijn Algemene Voedings- en Dieetbehandeling op Oncoline, onder het kopje Beweging en training.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bewegen tijdens de behandeling van kanker in de palliatieve fase staat al geruime tijd in de belangstelling om de conditie en mogelijk klachten van vermoeidheid, kwaliteit van leven en functioneren van patiënten te verbeteren. In het wetenschappelijk onderzoek staat de definiëring van beweging en/of training vaak ter discussie.

In de literatuur wordt er veelal gebruik gemaakt van interventies zoals aerobe training en krachttraining, maar er worden ook andere interventies toegepast, zoals loopinterventies. Ook in de uitvoering van deze interventies zien we een grote verscheidenheid. Een groot voordeel van de beweeginterventies is de laagdrempelige toegankelijkheid.

De Nederlandse Norm Gezond Bewegen definieert welke inspanning er minimaal moet worden geleverd om een bijdrage te leveren aan de gezondheid. Deze norm kan worden behaald middels dagelijkse activiteiten, zoals wandelen en fietsen. Het meetbaar maken van het effect van bewegen op vermoeidheid, kwaliteit van leven en functioneren is complexer. In deze module bespreekt de werkgroep de inzet van bewegingsinterventies bij patiënten met kanker in de palliatieve fase ter verbetering van de specifieke uitkomstmaten vermoeidheid, kwaliteit van leven en functioneren. De werkgroep heeft daarvoor een specifieke keuze gemaakt voor bewegingsinterventies onder supervisie.

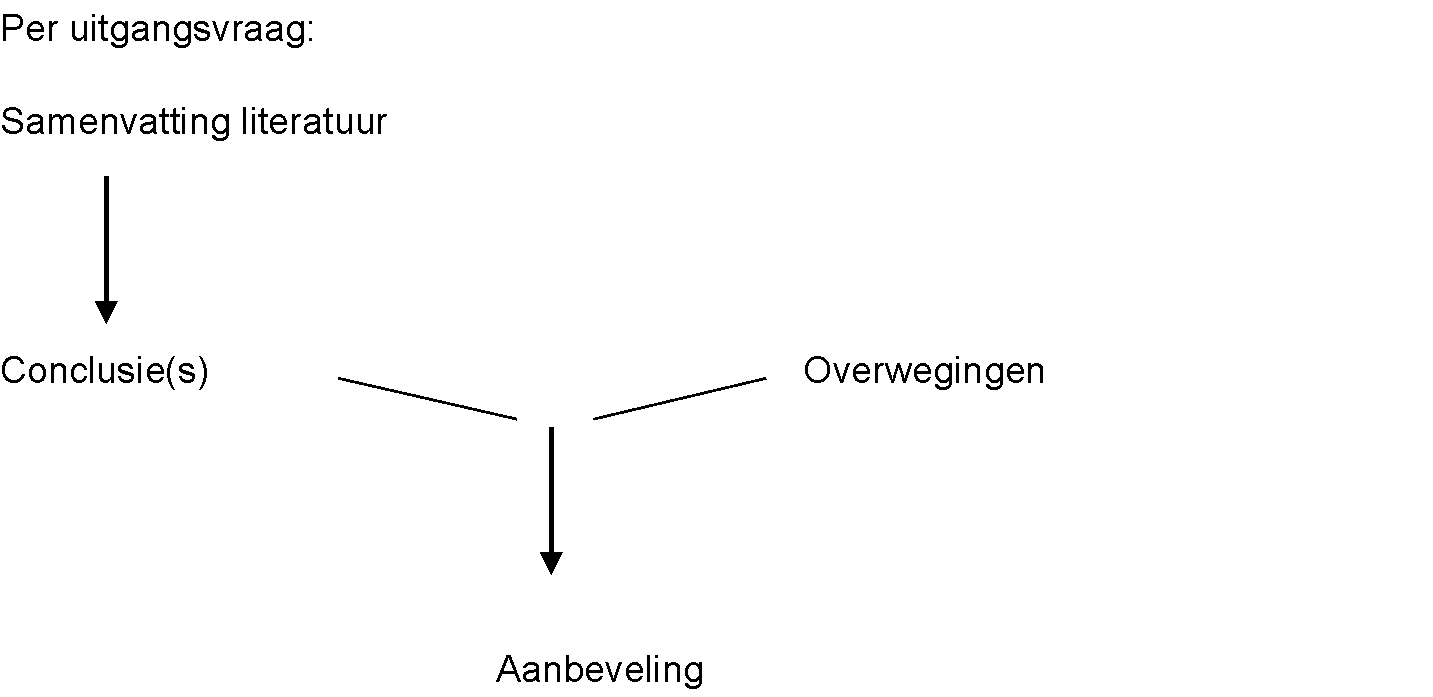

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Er is conflicterend bewijs van zeer lage kwaliteit (inconsistentie, risk of bias en imprecisie) over het effect van fysieke training en/of krachttraining in vergelijking met standaardzorg op vermoeidheid bij patiënten met kanker in de palliatieve fase in het algemeen en ook specifiek in de periode van ziektegerichte palliatie.

[Rief 2014, Bourke 2014, Dittus 2017, Pyszora 2017, Dhillon 2017, Uster 2017, Mayo 2014]

Er is conflicterend bewijs van zeer lage kwaliteit (inconsistentie, risk of bias en imprecisie) over het effect van fysieke training en/of krachttraining in vergelijking met standaardzorg op kwaliteit van leven bij patiënten met kanker in de palliatieve fase in het algemeen en ook specifiek in de periode van ziektegerichte palliatie.

[Dittus 2017, Rief 2014, Bourke 2014, Vanderbyl 2017, Dhillon 2017, Uster 2017, Mayo 2014]

Er is geen literatuur voorhanden die het effect analyseert van fysieke training en/of krachttraining in vergelijking met standaard zorg op kwaliteit van leven bij patiënten met kanker in specifiek de periode van symptoomgerichte palliatie.

Er is conflicterend bewijs van zeer lage kwaliteit (inconsistentie, risk of bias en imprecisie) over het effect van fysieke training en/of krachttraining in vergelijking met standaardzorg op fysiek functioneren bij patiënten met kanker in de palliatieve fase in het algemeen en ook specifiek in de periode van ziektegerichte palliatie.

[Dittus 2017, Vanderbyl 2017, Dhillon 2017, Uster 2017, Mayo 2014]

Er is geen literatuur voorhanden die het effect analyseert van een interventie met fysieke training en/of krachttraining in vergelijking met standaard zorg op fysiek functioneren bij patiënten met kanker in specifiek de periode van symptoomgerichte palliatie.

Algehele kwaliteit van bewijs = zeer laag.

Samenvatting literatuur

Beschrijving van de studies

Systematische reviews

Er werden 5 systematische reviews gevonden [Albrecht 2012, Beaton 2009, Dittus 2017, Lowe 2009, Salakari 2015]. De review van Albrecht (2012) geeft geen systematische beschrijving van de studies. De review van Lowe (2009) beschrijft 6 studies waarvan slechts één een gerandomiseerde studie (RCT) betreft. De review van Beaton (2009) beschrijft 8 studies waarvan 3 een RCT. De review van Salakari (2015) is primair gericht op rehabilitatie en bevat studies over beweging, maar ook over zelfmanagement en psychosociale interventies. De review van Dittus (2017) richt zich primair op bewegingsinterventies. De review includeerde 19 studies, waarvan 14 RCTs [Adamsen 2009, Brown 2006, Cheville 2010, Cheville 2013, Cormie 2013, Headly 2004, Henke 2014, Hwang 2012, Jensen 2014, Ligibel 2016, Litterini 2013, Oldervoll 2011, Schuler 2017, Tsianakas 2017].

De review van Dittus (2017) zal dan ook gebruikt worden in deze richtlijn. De studies in deze review includeerden patiënten met verschillende soorten kanker in een vergevorderd stadium waarvoor de behandeling niet meer curatief was gericht. Bij de analyse werd geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen de verschillende perioden van palliatie. In 12 van de 14 RCT’s werd een bewegingsinterventie vergeleken met standaard zorg; 2 RCT’s vergeleken het effect van aerobe training en krachttraining [Jensen 2014, Litterini 2013].

Additioneel gevonden gerandomiseerde studies

Tussen 2012 en 2017 zijn acht additionele gerandomiseerde studies (RCT’s) gepubliceerd waarin het effect van bewegingsinterventies bij patiënten met kanker in de palliatieve fase is bestudeerd [Bourke 2014, Dhillon 2017, Lopez-Sendin 2012, Mayo 2014, Pyszora 2017, Rief 2014, Uster 2017, Vanderbyl 2017]. Vier studies includeerden patiënten in de periode van ziektegerichte palliatie: [Bourke 2014, Dhillon 2017, Rief 2014, Vanderbyl 2017], één in de periode van symptoomgerichte palliatie [Pyszora 2017], drie studies konden niet worden ingedeeld [Lopez-Sendin 2012, Mayo 2014, Uster 2017].

Deze studies vergeleken een variatie aan interventies. De meeste interventies bestonden uit aerobe oefeningen en/of krachttraining en werden vergeleken met standaard zorg. Twee studies vergeleken 2 actieve interventies: Vanderbyl (2017) vergeleek Qigong met inspannings- en krachttraining, Mayo (2014) vergeleek het toevoegen van een 8 weken loopinterventie tijdens en na de standaard revalidatie met elkaar en met een controlegroep met alleen de revalidatie.

De controlebehandelingen waren in het algemeen standaard zorg. Twee studies gebruikten een sham interventie: Lopez-Sendin (2012) gebruikte simpel hand contact of ‘simple touch’ als controle voor fysiotherapie en Rief (2014) gebruikte ademhalingsoefeningen als controle voor krachttraining.

De duur van de interventies varieerde van 2 weken tot 6 maanden.

Kwaliteit van het bewijs

De review van Dittus (2017) scoorde positief op 4/11 AMSTAR-criteria. De review beschrijft onvoldoende het gehanteerde protocol, geeft geen kwaliteitsbeoordeling van de geïncludeerde studies en geen beoordeling van publicatiebias en includeerde geen grijze literatuur.

De additionele RCT’s scoorden low risk of bias op 2 tot 4 Cochrane criteria. Vanwege de aard van de interventies scoorden alle studies laag op blinderen. Vijf studies scoorden laag op incomplete uitkomsten vanwege een hoog aantal drop-outs [Dhillon 2017, Lopez-Sendin 2012, Rief 2014, Uster 2017, Vanderbyl 2017]. Mayo (2014) rapporteerde geen groepsgemiddelden, enkel percentages patiënten boven een klinisch relevant verschil. Eén studie had een risico op bias vanwege een onduidelijke randomisatieprocedure [Mayo 2014].

Effect op vermoeidheid

Systematische review

Dittus (2017) vergeleek de vermoeidheid na beweging/lichamelijke training met vermoeidheid na standaard zorg in tien RCT’s. In vier van deze 10 RCT’s werd een significant effect van bewegingstherapie ten opzichte van standaardzorg op de mate van vermoeidheid gevonden. Drie van de RCT’s gebruikten daarvoor inspanningsoefeningen [Adamsen 2009. Hwang 2012, Cheville 2013] en 1 RCT oefeningen op een stoel [Headley 2004]. Zes RCT’s vonden geen effect van bewegingstherapie op vermoeidheid [Brown 2006, Cheville 2010, Oldervoll 2011, Cormie 2013, Schuler 2017, Tsianakas 2017]. De review van Dittus (2017) verrichtte geen meta-analyse.

Additioneel gevonden gerandomiseerde studies

Zes RCT’s vergeleken vermoeidheid na beweging/lichamelijke training met vermoeidheid na standaard zorg of een controle-interventie. In twee RCT’s was vermoeidheid gedefinieerd als inclusiecriterium.

De studies gebruikten een diversiteit aan vermoeidheidsinstrumenten (EORTC-QLQ-FA 13, FACT-F, ESAS, EORTC QLQ-C30-fatigue, LASA-vermoeidheid, VAS vermoeidheid).

Drie RCT’s includeerden patiënten in de periode van ziektegerichte palliatie:

- Rief includeerde 60 patiënten die vanwege metastasen in de thoracale, lumbale of sacrale wervelkolom gedurende 2 weken behandeld werden met radiotherapie [Rief 2014]. De patiënten werden gerandomiseerd tussen een begeleide krachttraining op de dagen van de bestraling of passieve fysiotherapie. Patiënten in de interventiegroep werden geïnstrueerd de oefeningen thuis gedurende zes maanden voort te zetten in een frequentie van drie keer per week. Na 3 maanden werd er geen significant effect gevonden op fysieke vermoeidheid (EORTC QLQ-FA 13, effect size -0.04, p=0.637), maar na 6 maanden was dit wel het geval (Effect size -0.71, p=0.013). Er werden geen verschillen gevonden in emotionele en cognitieve vermoeidheid.

- Bourke includeerde 100 patiënten met lokaal gevorderde of gemetastaseerde prostaatkanker die langdurig androgeen-deprivatie therapie gebruikten [Bourke 2014]. Deze patiënten werden gerandomiseerd tussen een 12 weken durende inspannings- en krachttraining in combinatie met voedingsadviezen of standaard zorg. Er werd een statistisch significant effect op vermoeidheid gemeten na 12 weken (FACT-F, gecorrigeerde MD: 5.3 points; 95%CI 2.7–7.9, p<0.001) en na 6 maanden (gecorrigeerde MD: 3.9 points, 95%CI 1.1–6.8, p=0.007).

- Dhillon randomiseerde 112 patiënten met een stadium III/IV-longkanker tussen een 8 weken durende fysieke activiteitentraining en standaard zorg [Dhillon 2017]. Hij vond geen verschil in vermoeidheid na 2, 4 en 6 maanden (FACT-F, verschil 1.2, 95%CI -3.5 - 5.8, p=0.62).

Slechts 1 studie includeerde patiënten in de periode van symptoomgerichte palliatie:

- Pyszora randomiseerde 60 patiënten met vermoeidheid (score ≥4 op een 0-10 numerieke schaal) bij kanker in een vergevorderd stadium die verwezen waren voor een palliatieve zorg voorziening tussen een 2 weken durend fysiotherapie programma of standaard zorg [Pyszora 2017]. De studie toonde een significant effect op vermoeidheid na 2 weken (ESAS fatigue, fysiotherapie: 4.6 (1.6), Standaard zorg: 6.3 (1.2), p<0.01).

Twee studies konden niet worden ingedeeld naar periode van palliatie:

- Uster randomiseerde 58 patiënten met lokaal vergevorderde of gemetastaseerde kanker van de longen of de gastro-intestinale tractus tussen een 3 maanden durende interventie bestaande uit krachttraining gecombineerd met voedingsadviezen en standaard zorg [Uster 2017]. Na 3 en 6 maanden was het beloop in vermoeidheid t.o.v. de uitgangssituatie niet verschillend tussen de groepen (EORTC QLQ-C30-fatigue, 3 maanden Interventiegroep: -1.5 (4.4), Standaard zorg: 2.2 (5.2); 6 maanden: Interventiegroep -1.3 (4.7), Standaard zorg: -4.9 (5.3); p=0.75).

- Mayo vergeleek het toevoegen van een 8 weken loopinterventie tijdens en na de standaard revalidatie met elkaar en met een controlegroep met alleen de revalidatie bij 26 patiënten met kanker in een vergevorderd stadium die bij inclusie vermoeid waren (intensiteit ≥4 op een visueel-analoge schaal) [Mayo 2014]. Er werden geen kwantitatieve effect-analyses verricht. Per groep werd het percentage patiënten met een klinische significante vermindering van vermoeidheid berekend uitgaande van bekende minimal clinically important differences gemeten met de FACIT-F (Person Fatigue Measures (PFM): Respons Tijdens groep: 43%, Na groep: 68%, Controle: 25%).

Samenvattend: de studies laten een variabel en soms tegenstrijdig effect zien van beweging/lichamelijke activiteit op vermoeidheid, met een positief effect in drie van de vijf additioneel geïncludeerde studies waarin de mate van vermoeidheid is vergeleken tussen een bewegingsinterventie en standaard zorg of een controle interventie. Kanttekening hierbij is dat vooral de interventies zeer heterogeen zijn met programmaduren tussen 2 weken en 12 maanden, dat ze soms bestaan uit inspanningsoefeningen (lichamelijke beweging, fysiotherapie looptraining) en soms uit krachttrainingen of een combinatie.

Effect op kwaliteit van leven

Systematische review

Dittus vergeleek kwaliteit van leven na beweging/lichamelijke training met kwaliteit van leven na standaard zorg in negen RCT’s [Dittus 2017]. In drie van deze negen RCT’s werd een significant effect van bewegingstherapie ten opzichte van Standaard zorg op kwaliteit van leven gemeten [Adamsen 2009, Brown 2006, Henke 2014]. Zes RCT’s vonden geen effect van bewegingstherapie op kwaliteit van leven [Cheville 2013, Cormie 2013, Headly 2004, Hwang 2012, Ligibel 2016, Tsianakas 2017].

Additioneel gevonden gerandomiseerde studies

Zes RCT’s vergeleken kwaliteit van leven na beweging/lichamelijke training met kwaliteit van leven na standaard zorg of een controle-interventie.

De studies gebruikten verschillende instrumenten om kwaliteit van leven te meten: EORTC-QLQ-BM-22, EORTC-QLQ-C30-Global QoL, EQ-5D VAS.

Vier RCT’s includeerden patiënten in de periode van ziektegerichte palliatie

- Rief vond een significant effect van krachttraining op psychosociale aspecten van kwaliteit van leven (EORTC QLQ-BM 22, effect na 3 maanden -0.79, p=0.001; effect na 6 maanden -0.77, p=0.010), maar niet op andere subschalen [Rief 2014].

- Bourke vond een significant effect van inspannings- en krachttraining in combinatie met voedingsadviezen op kwaliteit van leven na 12 weken (FACT-G, gecorrigeerde MD: 8.9 points; 95%CI 3.7–14.2, p=0.001), maar niet na 6 maanden (gecorrigeerde MD: 3.3 points; 95%CI 2.6 to 9.3, p=0.27) [Bourke 2014].

- Dhillon vond geen effect van fysieke activiteitentraining op kwaliteit van leven na 6 maanden (EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global QOL, Fysieke activiteit: 61.21, Standaard zorg: 54.42 (verschil 6.79; 95%CI -4.39 to 17.97; p=0.23) [Dhillon 2017].

- Vanderbyl vergeleek standaard fysieke trainingen met Qigong bij 36 patiënten met longkanker of kanker vanuit de gastro-intestinale tractus [Vanderbyl 2017]. Na 6 weken vond hij geen verschil in kwaliteit van leven (FACT-G: verandering ten opzichte van baseline: standaard training: 3.5 (14.1), Qigong: 3.6 (6.6), p=0.98).

De twee studies die niet konden worden ingedeeld naar periode van palliatieve zorg rapporteerden eveneens de kwaliteit van leven:

- Uster vond geen effect van krachttraining op het beloop van Global health gedurende 3 en 6 maanden na start (EORTC QLQ-C30, beloop gedurende 3 maanden, Interventiegroep: 4.5 (3.4)), Standaard zorg: 2.7 (4.0); gedurende 6 maanden, 5.7 (3.7), Standaard zorg: 2.7 (4.1); p=0.72) [Uster 2017].

- Mayo berekende het percentage patiënten met een klinisch relevante verbetering in kwaliteit van leven voor de groepen met en zonder loopinterventie zonder het verschil te testen (EQ-5D VAS; respons, Tijdens groep: 64%, Na groep: 33%, Controle: 28%) [Mayo 2014].

Samenvattend: twee van de vijf additioneel geïncludeerde studies waarin een bewegingsinterventie kwantitatief werd vergeleken (en getoetst) met standaard zorg of een controle interventie vonden een gunstig effect op kwaliteit van leven.

Effect op fysiek functioneren

Systematische review

Dittus vergeleek functioneren na beweging/lichamelijke training met standaard zorg en vond 4 RCT’s [Adamsen 2009, Oldervoll 2011, Cormie 2013, Henke 2014], [Dittus 2017]. Al deze vier RCT’s toonden een significant effect van bewegingstherapie ten opzichte van standaard zorg op fysiek functioneren.

Additioneel gevonden gerandomiseerde studies

Vier RCT’s vergeleken functioneren na beweging/lichamelijke training met functioneren na standaard zorg. De studies gebruikten hiervoor de QLQ-C30-Fysieke activiteit (2 studies), de activity short form of de 6 minuten looptest (1 studie).

Twee RCT’s includeerden patiënten in de periode van ziektegerichte palliatie:

- Dhillon vond geen effect van fysieke activiteitentraining op fysiek functioneren na 6 maanden (EORTC-QLQ-C30 Fysieke activiteit 76.67, Standaard zorg: 73.07; verschil 3.6; 95%CI -5.8 to 12.99; p=0.45) [Dhillon 2017].

- Vanderbyl vond een significante verbetering in fysiek functioneren ten opzichte van baseline na 6 maanden (Standaard training: 73.3 (60.1), Qigong: -4.0 (45.7), p=0.002; andere fysieke testen waren niet verschillend (speed walk, sit-to-stand, reach forward, reach up) [Vanderbyl 2017].

De twee studies die niet konden worden ingedeeld naar de periode van palliatie rapporteerden fysiek functioneren:

- Uster vond geen effect van krachttraining op het beloop van fysiek functioneren gedurende 3 en 6 maanden na start (fysiek functioneren, beloop gedurende 3 maanden: fysieke training: 0 (3.3), Standaard zorg: -8.7 (3.8); gedurende 6 maanden: Fysieke training: -1.2 (3.6), Standaard zorg: -2.0 (4.0); p=0.34) [Uster 2017].

- Mayo berekende het percentage patiënten met een klinisch relevante verbetering in fysiek functioneren voor de groepen met en zonder loopinterventie zonder het verschil te testen (2 minuten looptest, adapted CHAMPS, RAND-36; respons Tijdens groep: 39%, Na groep: 67%, Controle: 50%) [Mayo 2014].

Samenvattend: één van de drie additioneel geïncludeerde studies waarin een bewegingsinterventie kwantitatief werd vergeleken (en getoetst) met standaard zorg of een controle interventie vond een positief effect op fysiek functioneren.

Zoeken en selecteren

Wat zijn de effecten van beweging/lichamelijke training op vermoeidheid, kwaliteit van leven en (fysiek) functioneren in vergelijking met geen beweging/lichamelijke training bij patiënten met vermoeidheid bij kanker in de palliatieve fase?

Patiënten Patiënten met vermoeidheid bij kanker in de palliatieve fase

Interventie Beweging/lichamelijke training

Comparator Geen beweging/lichamelijke training

Outcome Vermoeidheid, kwaliteit van leven en (fysiek) functioneren

Referenties

- 1 - Adamsen L, Quist M, Andersen C, et al. Effect of a multimodal high intensity exercise intervention in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;339:b3410

- 2 - Albrecht TA, Taylor AG. Physical activity in patients with advanced-stage cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(3):293-300.

- 3 - Beaton R, Pagdin-Friesen W, Robertson C, et al. Effects of exercise intervention on persons with metastatic cancer: a systematic review. Physiother Can. 2009;61(3):141-53.

- 4 - Bourke L, Gilbert S, Hooper R, et al. Lifestyle changes for improving disease-specific quality of life in sedentary men on long-term androgen-deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2014;65(5):865-72.

- 5 - Brown P, Clark MM, Atherton P, et al., 2006. Will improvement in quality of life (QOL) impact fatigue in patients receiving radiation therapy for advanced cancer? Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;29, 52–58.

- 6 - Cheville AL, Girardi J, Clark MM, et al. Therapeutic exercise during outpatient radiation therapy for advanced cancer: Feasibility and impact on physical well-being. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(8):611-9.

- 7 - Cheville AL, Kollasch J, Vandenberg J, et al. A home-based exercise program to improve function, fatigue, and sleep quality in patients with Stage IV lung and colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(5):811-21.

- 8 - Cormie P, Newton RU, Spry N,et al. Safety and efficacy of resistance exercise in prostate cancer patients with bone metastases. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases. 2013;16(4):328-35.

- 9 - Cramp F, Byron-Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;Nov 14 (11).: CD006145.

- 10 - Dhillon HM, Bell ML, van der Ploeg HP, et al. Impact of Physical Activity on Fatigue and Quality of Life in People with Advanced Lung Cancer: a Randomised Controlled Trial. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2017.

- 11 - Dittus KL, Gramling RE, Ades PA. Exercise interventions for individuals with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2017;104:124-132.

- 12 - Headly JA, Ownby KK, John LD. The effect of seated exercise on fatigue and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(5):977-983.

- 13 - Henke CC, Cabri J, Fricke L, et al. Strength and endurance training in the treatment of lung cancer patients in stages IIIA/IIIB/IV. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:95–101.

- 14 - Hwang CL, Yu CJ, Shih JY, Yang, PC, Wu YT. Effects of exercise training on exercise capacity in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving targeted therapy. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:3169–3177.

- 15 - Jensen W, Baumann FT, Stein A, et al. Exercise training in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer undergoing palliative chemotherapy: a pilot study. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22(7):1797-806.

- 16 - Ligibel JA, Giobbie-Hurder A, Shockro L, et al. Randomized trial of a physical activity intervention in women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(8):1169-77.

- 17 - Litterini AJ, Fieler VK, Cavanaugh JT,et al. Differential effects of cardiovascular and resistance exercise on functional mobility in individuals with advanced cancer: a randomized trial. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2013;94(12):2329-35.

- 18 - Lopez-Sendin N, Alburquerque-Sendin F, Cleland JA, et al. Effects of physical therapy on pain and mood in patients with terminal cancer: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med (New York, NY). 2012;18(5):480-6.

- 19 - Lowe SS, Watanabe SM, Courneya KS. Physical activity as a supportive care intervention in palliative cancer patients: a systematic review. J. Support Oncol. 2009;7(1):27-34.

- 20 - Mayo NE, Moriello C, Scott SC, et al. Pedometer-facilitated walking intervention shows promising effectiveness for reducing cancer fatigue: a pilot randomized trial. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(12):1198-209.

- 21 - Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Snyder C, Geigle PM, Berlanstein DR, Topaloglu O. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012, Aug 15 (8): CD008465.

- 22 - Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Lydersen S, et al. Physical exercise for cancer patients with advanced disease: a randomized controlled trial. The oncologist. 2011;16(11):1649-57.

- 23 - Pyszora A, Budzynski J, Wojcik A, et al. Physiotherapy programme reduces fatigue in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care: randomized controlled trial. Supportive care in cancer : Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2899-908.

- 24 - Rief H, Akbar M, Keller M, et al. Quality of life and fatigue of patients with spinal bone metastases under combined treatment with resistance training and radiation therapy- a randomized pilot trial. Radiat Oncol Investig. 2014;9:151.

- 25 - Salakari MR, Surakka T, Nurminen R, et al. Effects of rehabilitation among patients with advances cancer: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):618-28.

- 26 - Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise 1662 guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409-26.

- 27 - Schuler MK, Hentschel L, Kisel W, et al. 017. Impact of different exercise programs on severe fatigue in patients undergoing anticancer treatment - a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53:57–66.

- 28 - Tsianakas V, Harris J, Ream E, et al. CanWalk: a feasibility study with embedded randomised controlled trial pilot of a walking intervention for people with recurrent or metastatic cancer. BMJ Open 2017;7(2):e013719.

- 29 - Uster A, Ruehlin M, Mey S, et al. Effects of nutrition and physical exercise intervention in palliative cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2017.

- 30 - Vanderbyl B, Mayer M, Nash C, et al. A comparison of the effects of medical Qigong and standard exercise therapy on symptoms and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(6):1749-58.

Evidence tabellen

Systematic reviews

|

I Study ID |

II Method |

III Patient characteristics |

IV Intervention(s) |

V Results primary outcome |

VI Results secondary and all other outcomes |

VII Critical appraisal of study quality |

|

1. Reference

|

1. Study design 2. Source of funding/conflicts of interest 3. Setting 4. Sample size 5. Duration of the Study |

1. Eligibility criteria 2. Patient characteristics 3. Group comparability

|

1. Intervention(s) 2. Intervention 2 2. Comparator(s)

|

1. Effect size primary outcome

|

1. Effect size secondary outcome(s) 2. Effect size all other outcomes, endpoints

|

1.Level of evidence 2. Dropouts 3. Results critical appraisal

|

|

First author Journal Publication year

|

Specify the type of study Registration number Specify the source of funding presence of declaration of interest. Databases Study designs Setting Included studies Search date |

Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria Age Gender (M:F) Tumor Stage Palliative stage

|

including dose, length, regimen and timing if relevant

|

Functioning Fatigue Quality of life Participation Other (primary as defined in the study)

|

Brief description of secondary outcome(s) and p values. including adverse effects, toxicity

|

Amstar score

|

|

Dittus Preventive Medicine 2017

|

Design: Systematic review (Non-Cochrane) NR Funding: Government NIH Databases: PubMed, Ovid Medline and CINHAL Study designs: RCTs, single-arm pre/post interventions, pragmatic studies and prospective cohort studies evaluating programs Setting NR N included studies: 26 (14 RCT) Search date: March 2017

|

Eligibility criteria: English language articles; RCTs, single-arm pre/post interventions, pragmatic studies and prospective cohort studies; evaluating programs; testing an intervention with a component of exercise and where at least one third of the sample population had advanced cancer; parameters of physical capacity including aerobe fitness, strength and standard measures of physical function, fatigue and overall QOL. Excluded: NR Mean age: NR NR Tumor types: Mixed population of advanced cancer patients 58% of studies (n=15), single cancer type 42% of studies (n = 11, of which 7 lung) Tumor stages: advanced stage Palliative stage: NR No information about group comparability

|

Interventions: Sixteen focused on exercise (62%) and ten (38%) were multi-modality interventions that included exercise. Interventions varied in length, intensity, exercise activity included, location, and supervision.

NR or 6-16 weeks Control: diverse, mostly usual care

|

Three RCTs showed significant improvement in functional tests compared to controls, not significantly different between groups in one RCT, Another RCT reported significantly better self-reports of physical function compared to control (not tested) Three RCTs identified a significant reduction in fatigue between groups who did and did not receive an exercise intervention; One RCT, in individuals with metastatic breast cancer receiving chemotherapy, identified a significant difference in fatigue between the two groups, using chair exercise; Six RCTs observed no significant difference in fatigue between groups. In summary RCT trials did not clearly identify improved fatigue with exercise interventions compared to controls Three RCTs (n=367 participants) identified significant improvements in QOL compared to controls; Six RCTs (n = 231 participants) reported no improvements in QOL compared to controls. |

NR NR

|

Systematic review Dropouts: NR Amstar score: 4/11 (downgraded for lack of protocol, descriptions, quality assessment, publication bias, grey literature)

|

|

Salakari Acta Oncologica 2015

|

Design: Systematic review (Non-Cochrane) NR Funding: NR NR Databases: Medline, Cochrane Study designs: RCT Setting NR N included studies: 13 RCT Search date: September 2014

|

Eligibility criteria: Advanced cancer or palliative care and rehabilitation; 2009-2014; RCT; adults; abstract and full text available Excluded: Incomplete studies; non-English; non-controlled; non-randomized; case reports; clinical practice presentation; treatment protocols and models Mean age: NR NR Tumor types: all Tumor stages (RCTs): Advanced cancer and palliative care and rehabilitation Palliative stage: NR No information about group comparability |

Intervention: Physical exercise; Physical exercise and massage; football training; Resistance training and aerobe exercise

NR Control: Variable, but not systematically reported

|

Exercise improves physical performance and has positive effects on several other domains of QoL. Effective rehabilitation also improves the overall QoL.

|

NR We found no adverse effects related to or caused by rehabilitation.

|

Systematic review NR Amstar score 5/11 downgraded for lack of protocol, grey literature, quality assessment, assessment of publication bias, and conflict of interest information

|

|

Albrecht CLIN J Oncol Nurs 2012

|

Design: Systematic review (Non-Cochrane) NR Funding: Public research funds, government National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the National Institutes of Health (#5-K07-AT002943). Databases: Ovid, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PubMed Study designs: retrospective chart reviews, feasibility studies, case studies, and randomized trials Setting NR N included studies: 16 (2 RCT) Search date: NR |

Eligibility criteria: English, published after 1991, and focus on adult participants with advanced-stage cancer, and examine the effects of a form of PA. No exclusion criteria Mean age: NR NR Tumor types: all types Tumor stages: advanced stage Palliative stage: NR Group comparability not reported

|

Intervention: Any form of additional physical movement that resulted in increased energy expenditure (e.g., physical aerobe activity, group exercise, rehabilitation exercises)

NR Comparators: None or Usual care

|

Seated exercise intervention showed statistically lower fatigue scores compared to the usual care group Seated exercise had a slower decrease in reported HRQOL through four cycles of chemotherapy, with trends toward significance than usual care (p=0.07; 1 study)

|

The intervention group was more likely to be discharged home (p= 0.05; 1 study) and die at home (p=0.01; 1 study).

|

Systematic review Amstar score: 4/11 (downgraded for lack of protocol, descriptions, quality assessment, publication bias, grey literature)

|

|

Beaton Physiotherapy Canada 2009

|

Design: Systematic review (Non-Cochrane) NR Funding: NR No conflict of interest (stated) Databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Databases of Systematic Reviews (EBM Reviews—Ovid), and PEDro Study designs: Case series and RCT Setting NR N included studies: 8 (3 RCT) Search date: May 2008

|

Eligibility criteria: (1) population: persons with metastatic, advanced, or palliative cancer; (2) intervention: exercise as the intervention or a component of the intervention; (3) publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Excluded: Studies of persons with lymphoma, melanoma, or myeloma (these are not considered to be metastatic cancers) and studies in which results of those with metastatic cancer could not be separated from those with non-metastatic cancer; Studies in languages other than English or French, newspaper editorials, critical reviews of individual articles, and qualitative research studies; less than one-third of the sample had metastatic or advanced cancer. Mean age: NR NR Tumor types: all types Tumor stages (RCTs): Advanced and palliative intent Palliative stage: NR Group comparability not reported |

Intervention: Either (2 studies) 12 weeks exercise, as seated repetitive motion exercises based on a fitness video at home; individualized resistance program with warm-up and cool-down periods, in public facility, or (1 study) 3 weeks, 2-3 /per week Exercise interventions in cancer center involved group-based conditioning and relaxation combined with cognitive, social, emotional, and spiritual interventions.

3 weeks (1 study); 12 weeks (2 studies) Control intervention: usual level of care (3 studies); plus, waitlisted with an offer to participate in the exercise intervention at a later date (1 study).

|

No aggregate analysis

|

No aggregate analysis Three of the eight studies specifically reported on adverse effects, and no adverse effects occurred.

|

Systematic review

Amstar score 7/11 downgraded for lack of protocol, grey literature, publication bias. Included RCT scores 8/11

|

|

Lowe Journal of Supportive Oncology 2009

|

Design: Systematic review (Non-Cochrane) NR Funding: NR No conflict of interest (stated) Databases: NR Study designs: all Setting NR N included studies: 6 (1 RCT) Search date: NR

|

Eligibility criteria: examine physical activity intervention; palliative care patients; >18 years; PROMs QoL physical functioning or fatigue Excluded: mixed populations without subgroup analysis Mean age: NR NR Tumor types: all Tumor stages: NR Palliative stage: NR No information about group comparability |

Interventions: Aerobe exercise interventions, mix of aerobe and resistance training

4-52 weeks Control: NR

|

No significant difference (1 RCT) NR Slower decrease of well-being for intervention (1 RCT) NR NR

|

NR NR

|

Systematic review Dropouts: NR Amstar score 6/11 downgraded for lack of protocol, search information, grey literature, publication bias.

|

Primary studies

|

I Study ID |

II Method |

III Patient characteristics |

IV Intervention(s)

|

V Results primary outcome

|

VI Results secondary and all other outcomes |

VII Critical appraisal of study quality

|

|

1. Reference

|

1. Study design

2. Source of funding/conflicts of interest

3. Setting

4. Sample size 5. Duration of the Study

|

1. Eligibility criteria

2. Patient characteristics

3. Group comparability

|

1. Intervention(s) 2. Intervention 2

2. Comparator(s)

|

1. Effect size primary outcome

|

1. Effect size secondary outcome(s) 2. Effect size all other outcomes, endpoints

|

1.Level of evidence 2. Dropouts 3. Results critical appraisal

|

|

First author Journal Publication year

|

Specify the type of study Trial number Specify the source of funding presence of declaration of interest. Number of centers Countries Setting Randomized Inclusion dates

|

Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria Age Gender (M:F) Tumor Stage Palliative stage p for group comparability.

|

including dose, length, regimen and timing if relevant

Duration of intervention

|

Functioning Fatigue Quality of life Participation Other (primary as defined in the study)

|

Brief description of secondary outcome(s) and p values. including adverse effects, toxicity

|

Classification of intervention studies. Number of dropouts/withdrawals in each group Cochrane Score

|

|

Bourke European Urology 2014

|

Design: RCT ISRCTN88605738 Funding: None No conflict of interest (stated) Number of centers: NR Country: UK Setting NR n=100 Inclusion dates: 2008 to 2011

|

Eligibility criteria: ADT; locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer; sedentary (ie, exercising < 90 min per week at a moderate intensity); receiving continuous ADT for a minimum of 6 mo prior to recruitment; planned long-term retention on ADT Excluded: Unstable angina; uncontrolled hypertension; recent myocardial infarction; pacemakers; painful or unstable bony metastases Mean age: 71 M:F: 100:0 Tumor types: Prostate cancer Tumor stages: Locally advanced or metastatic Palliative stage: Disease directed treatment There were no significant differences between groups at baseline (p > 0.05 for all variables).

|

Intervention: Combined tapered (ie, a tapering of supervised support for behaviour change) 30 min aerobe (stationary cycles, rowing ergometers, and treadmills) and resistance exercise and dietary advice intervention delivered with integrated behaviour change support; supervised by an exercise physiologist. Twice a week from weeks 1–6, and once per week from weeks 7–12. self-directed independent exercise session once a week from weeks 1–6, and twice per week from weeks 7–12. Small-group healthy eating seminars, lasting approximately 20 min, were carried out every 2 w.

12 weeks Control: Usual care

|

FACT-F: 12 weeks adjusted MD: 5.3 points; 95%CI, 2.7–7.9, p<0.001; 6 months: adjusted MD: 3.9 points; 95%CI, 1.1–6.8, p=0.007 FACT-G: 12 weeks adjusted MD: 8.9 points; 95%CI, 3.7–14.2, p=0.001; 6 months: adjusted MD: 3.3 points; 95%CI, 2.6 to 9.3, p=0.27

|

No other differences for other secondary outcomes, except better aerobe exercise tolerance at 6 months for intervention group Ex: atrial fibrillation (n=1); C: death (n=1); no skeletal related adverse events

|

RCT Dropouts: 85% of the cohort completing 12-wk follow-up and 68% of men attending follow-up at 6 mo. Cochrane Score 4/7 downgraded for blinding and possible selective reporting

|

|

Cheville Cancer 2010

|

Design: RCT NR Funding: NR No conflict of interest (stated) Number of centers: 1 Country: US Setting: Mixed n=103 Inclusion dates: NR

|

Eligibility criteria: Adult advanced cancer patients; scheduled to undergo radiation therapy; diagnosis within the last 12 months; an expected survival time of at least 6 months; a 5-year survival probability of no more than 50%; and a treatment recommendation of radiation therapy of at least 2 weeks Excluded: previous radiation therapy; recurrent disease after a disease-free period of greater than 6 months; previous cancer diagnosis within 5 years; Mini Mental Status Examination score of less than 20; ECOG performance score of 3 or more; active alcohol or substance dependence (except nicotine); active thought disorder; suicidal plans; were participating in another psychosocial research trial Mean age: 59.5 (range 31-85) M:F: 66:37 Tumor types: all types Tumor stages: advanced stage Palliative stage: Disease directed treatment There were no significant differences between the groups at baseline

|

Intervention: Structured, multidisciplinary intervention; 8 sessions delivered by a PT and a psychiatrist or psychologist with cofacilitation provided by an advanced practice nurse, licensed social worker, or certified hospital chaplain depending on the theme; 3-day-per week schedule for 90 mins; truncal and upper-limb strengthening exercises; Lower limb strengthening activities

4 weeks Control: Usual care

|

LASA fatigue (change from baseline): 4 weeks: Ex: -8.3 (23.2), C: 6.3 (29.9), p=0.72; 8 weeks: Ex: -6.6 (27.1), C: -5.1 (28.8), p=0.96; 27 weeks Ex: -9.5 (27.1), C: -6.5 (26.27), p=0.92 LASA overall QoL (mean): 4 weeks: Ex: 72.8 (20.62), C: 64.1 (22.53), p=0.0469; 8 weeks: Ex: 71.9 (19.41), C: 68.4 (23.48), p=0.42; 27 weeks Ex: 72.1 (19.49), C: 72.1 (18.97), p=0.99

|

NR NR

|

RCT Dropouts: Ex: 6 lost; C: 3 lost Cochrane score 3/7 downgraded for randomization, allocation concealment and blinding

|

|

Cheville Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2013

|

Design: RCT NCT01334983 Funding: Government National Institutes of Health grant KL2 RR024151-01. Number of centers: 1 Country: US Setting: Oncology clinic (Urban) n=66 Inclusion dates: May 2010 to July 2010

|

Eligibility criteria: Patients with pathology-confirmed Stage IV lung and colorectal cancers; Ambulatory Post Acute Care (AM-PAC) Computer Adaptive Test (CAT) scores between 50 and 75 Excluded: Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination score of 25 or less; inadequate English proficiency, hospice enrollment; an average pain numeric rating scale score of>= 6 of 10 Mean age: Ex: 63.8 (12.5; C: 65.5 (8.9) M:F: 35:31 Tumor types: lung and colorectal Tumor stages: IV Palliative stage: Mixed The groups were well balanced with respect to demographic, cancer type, and treatment characteristics

|

Intervention: Instructional session in REST as well as a pedometer-based walking program; bimonthly telephone calls; delivered by two PTs; wo sets of five-exercise routines, one targeting the upper and the other the lower body; participants were instructed to perform 10 repetitions of each REST exercise in the upper and lower body routines at least twice a week for a total of four sessions (two upper and two lower body); participants gradually increased their repetitions to 15; pedometers; participants were instructed to walk briskly.

8 weeks Control: Nothing

|

There was no difference in activity short form (mean change from 0 to 8 week): Ex: 1.56 (5.53) 95%CI -0.72 to 3.84); C: 0.94 (5.91) 95%CI -1.26 to 3.14; p=0.74 FACT-F favored the intervention group (mean change from 0 to 8 week): Ex: 4.46 (8.56) 95%CI0.81 to 8.11); C: -0.79 (9.11) 95%CI -4.26 to 2.67; p=0.03 There was no difference in FACT-G (mean change from 0 to 8 week): Ex: 1.07 (11.60) 95%CI -5.97 to 3.83); C: 0.12 (10.22) 95%CI -3.19 to 4.74; p=0.54

Mobility short form favored the intervention group (mean change from 0 to 8 week): Ex: 4.88 (4.66) 95%CI 2.96 to 6.80); C: 0.23 (5.22) 95%CI -1.76 to 2.22; p=0.002

|

Sleep favored the intervention group (mean change from 0 to 8 week): Ex: 1.46 (1.88) 95%CI 0.70 to 2.22); C: -0.10 (1.71) 95%CI -0.74 to 0.54; p=0.002; There was no difference in pain (mean change from 0 to 8 week): Ex: -0.62 (2.59) 95%CI -1.66 to 0.43); C: -0.50 (2.01) 95%CI -1.25 to 0.25; p=0.87 Deaths Ex: 5, C: 2; no adverse events occurred during or within hours of performing the REST exercises or the walking program.

|

RCT Dropouts: Ex: 7 lost (5 died); C: 3 lost (2 died) Cochrane score 5/7 downgraded for blinding

|

|

Cormie Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Disease 2013

|

Design: RCT NR Funding: Government Cancer Council of Western Australia. Author supported by Movember through the Prostate Cancer Foundation Number of centers: 1 Country: Australia Setting: Urban n=20 Inclusion dates: July 2011 to July 2012

|

Eligibility criteria: Histological diagnosis of prostate cancer, established bone metastatic disease as determined by a whole-body bone scan Excluded: Moderate–severe bone pain that limited activities of daily living (i.e., National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grade 2–3 bone pain19) or had musculoskeletal, cardiovascular and/or neurological disorders that could inhibit them from exercising Mean age: Ex: 73.1 (7.5), C: 71.2 (6.9) M:F: 20:0 Tumor types: Prostate cancer Tumor stages: Bone Metastases Palliative stage: NR The two groups were well balanced, with no significant differences in characteristics at baseline or in any of the outcome measures assessed.

|

Intervention: Twice-weekly resistance exercise sessions for 12 weeks in an exercise clinic; small groups of one to five participants; supervised by accredited exercise physiologists; 60 min sessions, eight exercises that target the major muscle groups of the upper and lower body

12 weeks Control: Usual care

|

SF-36 physical functioning (group difference in mean change): 0.0 (95%CI -4.2 to 4.2), p=0.996 Fatigue (MFSI-SF) (group difference in mean change): -4.2 (95%CI -17.6 to 9.2), p=0.521 SF-36 general health (group difference in mean change): 1.9 (95%CI -4.1 to 7.9), p=0.508; SF-36 physical health composite (group difference in mean change): -0.1 (95%CI -4.6 to 4.4), p=0.957; SF-36 mental health composite (group difference in mean change): 2.8 (95%CI -5.3 to 11.0), p=0.475

|

No differences in other SF-36, fatigue outcomes (MSFI-SF), BSI; Significant difference in leg extension (p=0.016), 400m walk (p=0.010), 6m walk (p=<0.001); whole body lean mass (p=0.026), appendicular lean mass (p=0.003) No adverse events or skeletal complications occurred during the exercise sessions; Ex: 1 fracture due to fall; Ex: 3 (advancing disease requiring chemotherapy, increased bone pain and fall); C: 1 (advancing disease requiring chemotherapy); P=0.264 |

RCT Dropouts: Only some assessments missing Cochrane score 5/7 downgraded for blinding

|

|

Dhillon Annals of Oncology 2017

|

Design: RCT ACTRN12609000971235 Funding: Non-governmental organization Lance Armstrong Foundation/National Lung Cancer Alliance Partnership as a Young Investigator Award (no grant number) to JV; the Vojakovic Fellowship from Slater and Gordon Asbestos Research Fund (no grant number); Cancer Institute NSW Clinical Fellowships (05/CRF/1-06, 2006; 09/RIG1-13, 2010) to JV; the ALTG to HD (no grant number), and PoCoG to HD (no grant number) Number of centers: 5 Country: Australia Setting: Hospitals (Urban) n=112 Inclusion dates: July 2009 to October 2014 |

Eligibility criteria: Histological diagnosis of cancer; an ECOG performance status (PS) 2; life expectancy>6 months; sufficient English to complete questionnaires; and assessed medically fit by treating physician and Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Excluded: NR Median age: 64 (34-80) M:F: 61:50 Tumor types: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) or small cell lung cancer (SCLC) Tumor stages: III/IV Palliative stage: Mixed Group comparability not reported

|

Intervention: Cancer-specific individualized, 8-week supervised Physical Activity (PA) intervention exercise (Move Your Body, behaviour change sessions) and nutrition (Eat for Health) education materials plus General health education materials. Individualized to baseline fitness and interests. It included a behaviour change program based on Theory of Planned Behaviour. week. Sessions lasted 1h: 45-min PA; 15-min behaviour support. PA was predominantly aerobe, and home-based PA was encouraged. EX participants received a pedometer, PA diary, and workbook.

8 weeks Control: Usual care (UC) (nutrition and PA education materials)

|

EORTC-QLQ-C30 physical functioning (6 months): EX: 76.67, C: 73.07 (diff 3.6; 95%CI -5.8 to 12.99; p=0.45) FACT Fatigue (6 months, adjusted): EX: 37.07, C: 35.76 (diff 1.31; 95%CI -3.51 to 6.12; p=0.59) EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global QOL (6 months) EX: 61.21, C: 54.42 (diff 6.79; 95%CI -4.39 to 17.97; p=0.23)

|

No differences at any other EORTC-QLQ-C30 QOL domains (Role functioning, Social functioning); GHQ, Pittsburg Sleep inventory; San Diego shortness of breath Questionnaire; (independent) Activities of daily living. Social cognitive determinants of exercise: EX: 26.64, C: 22.07 (diff 4.57, 95%CI 1.34 to 7.80, p=0.006) No SAE; Other AE: EX: 4 musculoskeletal events likely related to exercise (back or muscle soreness) resolving without treatment, 4 minor adverse events, which resolved without intervention.

|

RCT Dropouts: Missing’s/too unwell/deceased: Intervention (n=56): 2/6/12, control (n=55): 6/12/8 Cochrane score 4/7 (downgraded due to lack of blinding and incomplete outcome assessment)

|

|

Galvao Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010

|

Design: RCT ACTRN12607000263493 Funding: Government Cancer Council of Western Australia. Number of centers: 1 Country: Australia Setting: Urban n=57 Inclusion dates: July 2007 to September 2008

|

Eligibility criteria: Histologically documented prostate cancer; minimum prior exposure to AST longer than 2 months; without PSA evidence of disease activity; anticipated to remain hypogonadal for the subsequent 6 months. Excluded: Bone metastatic disease; musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, or neurological disorders that could inhibit them from exercising; inability to walk 400 meters or undertake upper and lower limb exercise; and resistance training in the previous 3 months Mean age: Ex: 69.5 (7.3); C: 70.1 (7.3) M:F: 57:0 Tumor types: Prostate cancer Tumor stages: localized and nodal metastases Palliative stage: NR There were no significant differences between groups at baseline.

|

Intervention: Combined progressive resistance (chest press, seated row, shoulder press, triceps extension, leg press, leg extension and leg curl, with abdominal crunches) and aerobe training (15 to 20 minutes of cardiovascular exercises (cycling and walking/ jogging) at 65% to 80% maximum heart rate and perceived exertion at 11 to 13 (6 to 20 point, Borg scale) twice a week for 12 weeks; one to five participants under direct supervision of an exercise physiologist.

12 weeks Control: Usual care

|

No difference in SF36 Physical functioning from 0-12 weeks: Ex: 81.7 (14.8) to 82.9 (17.3); C: 74.0 (28.9) to 77.5 (18.7); p=0.441 QLQ-C30-fatigue favored exercise from 0-12 weeks, p=0.021 SF-36 general health favored exercise from 0-12 weeks: Ex from 66.0 (23.1) to 71.4 (17.5); C: from 67.3 (23.1) to 60.2 (26.7), p=0.022

No differences for whole body fat, trunk fat, %fat mass, whole body weight

|

Soft tissue composition and dynamic muscle strength favored the exercise group. Quality of life assessed by the SF-36 (Table 6) showed better change scores for vitality (P .019), and the physical health composite scores (P .020) for the EX group. Assessments using the QLQ-C30 identified better change scores for EX in role (P .001), cognitive (P .007), nausea (P .025), and dyspnea (P .017), and a borderline difference for physical (P .062), emotional (P .098), pain (P .092), and insomnia (P .055). There were no adverse events during testing or the exercise intervention. |

RCT Dropouts: 4 patients in each group had missing data Cochrane score 5/7 downgraded for blinding

|

|

Hojan Polish Archives of Internal Medicine 2017

|

Design: RCT ISRCTN80765858 Funding: NR No conflict of interest (stated) Number of centers: 1 Country: Poland Setting: Regional cancer center n=72 Inclusion dates: December 2012 to December 2014

|

Eligibility criteria: Histologically confirmed diagnosis of high-risk or intermediate-risk PCa; ADT scheduled for a total period of 36 months; patients before RT (a total dose of 76 Gy in 38 fractions); ECOG 0–1; >= 18 years Excluded: Distant metastases and/or disease progression resulting in RT or the introduction of chemotherapy; with insufficiently controlled arterial hypertension or cardiac diseases resulting in circulation failure (heart failure above class II according to the New York Heart Association classification) or uncontrolled asthma; with insufficiently controlled metabolic diseases or endocrine, rheumatic, and absorption disorders, as well as other tumors; with preexisting bone metastases at high risk for fracture; or with a psychiatric illness or dementia or organic brain disease. Mean age: 66.2 (4.94) M:F: 72:0 Tumor types: Prostate cancer Tumor stages: NR Palliative stage: NR There were no significant differences between groups at baseline.

|

Intervention: 5 exercise sessions/wk for 8 weeks (during RT—between assessments I and II), and 3 d/wk for the next 10 months; either individually (strength training performed with the assistance of a physiotherapist) or in groups (exercises on treadmills or cycle ergometers, supervised by a therapist); brisk walking, running indoors or on a treadmill, various cycling activities (30 min); 25-minute resistance exercises; 65 to 70 minutes total; workout of 60 minutes

12 months Control: Usual care

|

QLQ-C30 physical functioning at baseline ex: 79.7 (18.9) C: 81.9 (15.4); 12 months Ex: 78.4 (17.8) C: 65.1 (19.5), p<0.01 FACT-F at baseline ex 113.4 (3.5) C:112.9 (3.9); 12 months Ex: 105.8 (7.7) C: 75.5 (8.1), p<0.001 QLQ-C30 global health at baseline ex: 53.7 (18.2) C: 54.1 (23.0); 12 months Ex: 57.4 (19.7) C: 52.3 (17.8), p=0.11

Significant advantage of exercise for distance 6min walk test (p<0.001), significant differences in blood markers only for total Psa, Il-6

|

Significant advantage of exercise for weight, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio (p<0.001) NR

|

RCT Dropouts: Ex: 1, C: 5 Cochrane score 5/7 downgraded for blinding

|

|

Jensen Support Care Cancer 2014

|

Design: RCT NR Funding: Non-governmental organization foundation “Stiftung Leben mit Krebs” Number of centers: 1 Country: Germany Setting: Outpatient oncology clinic, University hospital n=26 Inclusion dates: NR

|

Eligibility criteria: Advanced gastrointestinal cancer, including gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancer; ≥18 years; life expectancy ≥6 months; beginning of a new palliative treatment line Excluded: Symptomatic brain metastases; uncontrolled cardiovascular diseases; higher grades of osteoporosis; peripheral arterial insufficiency; insufficiently controlled coronary heart disease; arterial hypertension; metabolic diseases Mean age: 55 (13.1) M:F: 11:10 Tumor types: gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancer Tumor stages: advanced stage Palliative stage: Disease directed treatment There were no significant differences between groups at baseline.

|

Intervention: RET: resistance exercise training: supervised training sessions over 45 min; twice a week until a total of 24 sessions; 12 weeks; Resistance training of large muscle groups, including the legs, arms, back, and knees, was performed; Strength exercises were performed at 60–80 % of the one repetition maximum (1-RM) and consisted of two to three sets of 15–25 repetitions each. Intervention: AET: aerobe exercise training; supervised sessions lasting 45 min on a bicycle ergometer twice a week for 12 weeks. Starting with 60 % of their predetermined pulse rate in week 1–4, the working load was intensified to 70–80 % in week 5– 12. The exercise duration started with 10 min in week one and was increased up to 30 min in week 12. 12 weeks

|

QLQ-C30-physical functioning (change from baseline) RET: -2.4 (95%CI -8.5 to 3.7), AET: -3.3 (95%CI -9.8 to 3.3) QLQ-C30-fatigue (change from baseline) RET: 24.2 (95%CI 0.2 to 48.3), AET: 21.1 (2.5 to 39.6) QLQ-C30-global health status (change from baseline) RET: -14.4 (95%CI -31.6 to 2.8), AET: -13.3 (-26.2 to -0.3)

|

NR NR

|

RCT Dropouts: RET: 2 AET: 3 Cochrane score 2/7 (downgraded due to unclear randomization, lack of blinding and incomplete outcome assessment)

|

|

Ligibel Cancer 2016

|

Design: RCT NCT00405782 Funding: Non-governmental organization McMackin Foundation. Number of centers: 2 Country: US Setting: Cancer centers (Urban) n=101 Inclusion dates: September 2006 to March 2011

|

Eligibility criteria: Metastatic breast cancer or locally advanced disease not amenable to surgical resection, a life expectancy of 12 months, baseline performance of 150 minutes of recreational physical activity per week, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1 Excluded: Untreated brain metastases, uncontrolled cardiac disease, or other contraindications to moderate-intensity exercise. Mean age: 49 M:F: 0:101 Tumor types: Metastatic breast cancer or locally advanced disease not amenable to surgical resection Tumor stages: NR Palliative stage: Disease directed treatment “Baseline characteristics were distributed similarly”

|

Intervention: 16-week, moderate-intensity aerobe exercise program, delivered through a series of in-person (4 weeks monthly) and telephone contacts (weekly) by an exercise physiologist. Sessions focused on building exercise self-efficacy, overcoming barriers to exercise, documenting any injuries, and reviewing safe exercise practices. Heart rate monitor, a pedometer, and an exercise journal; 6-week membership to a gym in their local area.

16 weeks Control: Usual care for 16 weeks and was then offered participation in the exercise intervention

|

EORTC-QLQ-C30 physical functioning (16 weeks, change from baseline): EX: 4.79 (SD 2.4), C: 0.93 (SD 2.1), p=0.23 FACIT-fatigue (16 weeks, change from baseline): EX: 2.7 (SD 8.4), C: 2.7 (SD 9.3) p=0.63 EORTC-QLQ-C30 Global QOL (16 weeks, change from baseline) EX: 6.0 (SD 17.5), C: -1.0 (SD 21.5), p=0.17

Treadmill test (16 weeks, min. change from baseline): EX: 0.61 (SD 0.2), C: 0.37 (SD 0.2), p=0.35

|

No differences at any other EORTC-QLQ-C30 QOL domains (Role functioning, Emotional functioning, Cognitive functioning, Social functioning); Nausea/vomiting; Pain; Insomnia; Appetite loss; constipation; Diarrhea. Dyspnea (16 weeks, change from baseline): EX: -6.3 (SD 23.1), C: 4.0 (SD 19.8), p=0.04 No injuries or other adverse events were reported

|

RCT Dropouts: Missings/discontinued/never started: Intervention (n=48): 10/10/1, control (n=53): 7/3/2 Cochrane score 2/7 (downgraded due to unclear randomization, lack of blinding and incomplete outcome assessment)

|

|

Litterini Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2013

|

Design: RCT NR Funding: Non-governmental organization Northern New England Clinical Oncology Society and Exeter Hospital Number of centers: 1 Country: US Setting: Cancer center, palliative care service, rehabilitation department, and a local hospice. n=66 Inclusion dates: February 2010-March 2012 |

Eligibility criteria; >=18 years; advanced cancer Excluded: debilitating psychiatric illness; mental confusion; decreased mental capacity; difficulty communicating in English; lacked medical clearance. Mean age: 62.35 (12.49) M: F: 30:36 Tumor types: All: most with breast, lung, or colorectal cancer Tumor stages: advanced stage Palliative stage: Terminal phase There were no significant differences in age or seks between groups.

|

Intervention: Resistance exercises on circuit weight training equipment; Amount of resistance, repetitions, and sets were as tolerated. Intervention: Intervention: Cardiovascular exercises; >1 machine; duration and intensity were progressed as tolerated. 10 weeks

|

VAS Fatigue (mean difference in change from baseline): 9.03 (95%CI -0.02 to 18.08), p=0.050

SPPB total score (mean difference in change from baseline): 0.75 (95%CI 0.44 to 1.06, p<0.001

|

VAS pain (Mean difference in change from baseline): 1.71 (95%CI -3.39 to 6.81), p=0.50 No adverse events were reported

|

RCT Dropouts: Resistance: 11, Cardio: 3 Cochrane score 3/5 downgraded for allocation concealment, blinding and incomplete outcome data

|

|

Lopez-Sendin Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine 2012

|

Design: RCT NR Funding: NR No conflict of interest (stated) Number of centers: 1 Country: Spain Setting: Oncology department, university hospital (Urban) n=24 Inclusion dates: NR

|

Eligibility criteria: >18 years old; any type of tumor in stage III-IV; intensity of pain > 4 on a numerical pain rate scale Excluded: fragile tissue (skin, hair, or bone); systemic status (e.g., neutropenia, hypercalcemia, hypothyroidism, or anemia); unconscious; unable to complete the questionnaires used; projected to have less than 20 days to live; undergone manual therapy within the past 4 weeks Mean age: Ex: 55 (21), C: 54 (8) M:F: 18:6 Tumor types: all (lung, melanoma, sarcoma, pancreas, breast) Tumor stages: III/IV Palliative stage: Terminal phase No significant differences on baseline characteristics between both groups were found |

Intervention: physiotherapy: several different therapeutic massage techniques: effleurage, petrissage, and strain/counter strain techniques over the tender points; passive mobilization; active-assisted or active-resisted exercises, and local- and global-resisted exercises, as well as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) applied over joints and tight/painful muscles; six sessions of 30–35 minutes in duration over a 2-week period.

2 weeks Control: Sham: simple hand contact or ‘‘simple touch,’’ six sessions of 30–35 minutes in duration over a 2-week period

|

BPI (2 weeks, difference in change from baseline) worst pain: -1.5 (95%CI -3.08 to -0.08); BPI index: -2.68 (95%CI -4.17 to -1.18); BPI least pain 1.1 (95%CI -1.64 to 3.64); BPI pain on the average -1.33 (95%CI -3.26 to 0.6); BPI pain right now -2.0 (95%CI -3.9 to -0.1)

|

NR NR

|

RCT Dropouts: Ex: 4 (2 sedation, 1 refused, 1 died), C: 5 (1 sedated, 1 chemotherapy, 2 refused, 1 died) Cochrane score 3/5 downgraded for allocation concealment, blinding and incomplete outcome data

|

|

Mayo Clinical Rehabilitation 2014

|

Design: RCT NR Funding: Non-governmental organization MUHC and Research Institute of Pilot Project Competition. Number of centers: 1 Country: Canada Setting: University hospital (Urban) n=26 Inclusion dates: NR

|

Eligibility criteria: Adults, advanced cancer, undergoing interdisciplinary assessment and rehabilitation, moderate to severe rating of fatigue (VAS≥ 4/10, Cramp et al) Excluded: Unable to walk 100m unaided, waiting for a bone marrow transplant or surgery, uncontrolled pelvic or lower extremity metastatic disease. Mean age: Group 1: 59.6 (11.4) [44–78] Group 2: 57.1 (14.9) [34–88] Group 3: 54.4(12.2) [38–71] M:F: 14:12 Tumor types: all Tumor stages: 2-5 Palliative stage: NR Group comparability not reported

|

Intervention: During: Individualized 8 weeks walking program based on the participants’ current walking status and progressed according to fatigue level; pedometer; weekly standardized telephone call, during cancer rehabilitation program Intervention: After: Individualized 8 weeks walking program based on the participants’ current walking status and progressed according to fatigue level; pedometer; weekly standardized telephone call, after cancer rehabilitation program 8 weeks Control: Only the cancer rehabilitation program, daily fatigue diary, weekly standardized telephone call |

Physical function (2min walktest,adapted CHAMPS, RAND-36) Response: During group: 39%, after group: 67%, Control: 50% Person Fatigue Measures (PFM): Response During Group: 43%, After Group: 68%, Control: 25% EQ-5D VAS response: During group: 64%, after group: 33%, Control: 28%

|

NR NR

|

RCT Dropouts: Loss n=12, ITT performed Cochrane score 2/7 (downgraded due to unclear randomization, lack of blinding and selective reporting)

|

|

Oldervoll The Oncologist 2011

|

Design: RCT NCT00397774 Funding: Non-governmental organization Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation and the Norwegian Cancer Society Number of centers: 6 Country: Norway Setting: Palliative care units, local/regional hospitals (Mixed) n=231 Inclusion dates: October 2006 and May 2009.

|

Eligibility criteria: Incurable and metastatic cancer (either locoregional or distant metastases); a life expectancy of 3 months to 2 years; a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score 60; adequate pain relief (pain intensity 3 on a 0–10 numerical rating scale); the ability to walk; and unimpaired cognitive function Excluded: NR Mean age: Ex: 62.6 (11.3), C: 62.2 (10.7) M:F: 87:143 Tumor types: Gastrointestinal, Lung, Breast, Urological, Gynecological, other Tumor stages: metastatic (100%) Palliative stage: Symptom oriented palliation At baseline, the groups were well balanced with respect to demographics, level of physical activity over the past year, and medical characteristics such as diagnosis, ongoing chemotherapy and radiation treatment, and comorbidities

|

Intervention: Six circuit stations: exercise for 2 minutes; continuing for 30 minutes in total; lower and upper limb muscle strength, standing balance, and aerobe endurance; Strengthening of the lower limb; Balance: stand on either a trampoline or a thick mat; Strengthening of the upper limb; General functioning: start in the standing position, descend to the floor, lie on back, then roll from side to side, and stand up again; Aerobe endurance: stationary bicycling or treadmill walking.

8 weeks Control: Usual care

|

Fatigue questionnaire (difference in change from baseline) total fatigue: -0.5 (95%CI -2.0 to 1.0), p=0.53; physical fatigue -0.3 (95%CI -1.6 to 1.0), p=0.62; mental fatigue -0.3 (95%CI -0.6 to 0.3), p=0.53

|

Other (difference in change from baseline) SWT 60 (95%CI 16 to 103.4), p=0.008; sit to stand 0.5 (95%CI -0.5 to 1.5), p=0.34; maximal stepping 3.0 (95%CI -1.9 to 7.7), p=0.22; handgrip strength 2.0 (95%CI 0.4 to 3.5), p=0.01 NR

|

RCT Dropouts: Ex: 43 (5 death, 27 disease progression, 11 other), C: 25 (5 death, 16 disease progression, 4 other) Cochrane score 3/5 downgraded for allocation concealment, blinding and incomplete outcome data

|

|

Pyszora Support Care Cancer 2017

|

Design: RCT NR Funding: Non-governmental organization Nicolaus Copernicus University CollegiumMedicum, Bydgoszcz, Poland Number of centers: 1 Country: Poland Setting: Palliative care department, University hospital n=60 Inclusion dates: January 2010 - May 2011

|

Eligibility criteria: Advanced cancer; intensity of fatigue ≥4 in a 10- point NRS (Numerical Rating Scale); survival expectancy of a month at the very least; functional status allowing the patient to participate in the proposed therapy; ≥18 years old Excluded: anaemia (haemoglobin ≤8 g/dl); the existence of comorbidities causing fatigue (e.g. multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, heart failure); infection requiring antibiotics; age <18; inability to understand written and spoken Polish. Mean age: Ex: 72.4 (9.5), C: 69.3 (13.7) M:F: 21:39 Tumor types: alimentary system, urogenital system, lung, CNS, mammary gland, hematological, indefinite Tumor stages: advanced stage Palliative stage: Symptom oriented palliation Study groups did not differ significantly with respect to age, tumor location and the study site. However, a significant gender difference was observed (p=0.03).

|

Intervention: Physiotherapy program. 2-weeks; six therapy sessions (three per week); 30 min per session; active exercises of the upper and lower limbs; selected techniques of myofascial release (MFR); selected techniques of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF); dedicated therapist, licensed in PNF method and trained in the application of myofascial release techniques.

2 weeks Control: no exercise

|

ESS fatigue Ex: 4.6 (1.6), C: 6.3 (1.2), p<0.01

ESAS (12 days): Pain Ex: 1.2 (1.5), C: 1.7 (2.0), p=0.2; nausea Ex: 0.3 (0.8), C: 0.9 (2.0), p=0.1; depression Ex: 2.7 (2.1), C: 2.8 (2.6), p=0.8; anxiety Ex: 2.5 (2.1), C: 2.5 (2.5), p=0.9; drowsiness Ex: 2.3 (2.5), C: 3.8 (2.7), p=<0.05; appetite 3.1 (2.5), C: 3.8 (2.8), p=0.4; well-being Ex: 3.0 (1.2), C: 5.0 (1.3),p=<0.01; breathlessness Ex 0.8 (1.5), 0.9 (1.6), p=0.7

|

NR NR

|

RCT Dropouts: Ex: 1 death: C: 1 death Cochrane score 4/7 downgraded for blinding, unclear allocation concealment

|

|

Rief Radiation Oncology 2014

|

Design: RCT NCT01409720 Funding: NR NR Number of centers: 1 Country: Germany Setting: Radio oncology department, university hospital (Urban) n=60 Inclusion dates: September 2011-March 2013

|

Eligibility criteria: Histologically confirmed cancer of any primary and bone metastases of the thoracic or lumbar segments of the vertebral column, or of the os sacrum; age of 18 to 80 years; a Karnofsky performance score ≥ 70; already initiated bisphosphonate therapy Excluded: NR Mean age: Ex: 61.3 (10.1), C: 64.1 (10.9) M:F: 33:27 Tumor types: spinal metastases of any origin Tumor stages: metastatic Palliative stage: Disease directed treatment No information about group comparability

|

Intervention: RT: resistance training; 2 weeks; 30 min. under the guidance of a physiotherapist; practice at homes three times a week and continued the resistance training themselves until the last investigation after six months.

2 weeks Control: Sham-like PT: physical therapy; 2 weeks; 15 min. passive physical therapy in form of breathing exercises for a period of two weeks.

|

EORTC QLQ-FA 13: Physical fatigue: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p= 0.637, (t0-t3) after 6 month p=0.013; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.04, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.71; Emotional fatigue: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p= 0.796, (t0-t3) after 6 month p=0.156; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.14, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.35; Cognitive fatigue: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p=0.248, (t0-t3) after 6 month p=0.433; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.24, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.19; Interference with daily life: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p=0.093, (t0-t3) after 6 month p=0.006; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.48, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.91; Social sequelae: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p=0.129, (t0-t3) after 6 month p=0.363; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.40, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.37 EORTC QLQ-BM 22: Painful sites: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p=0.399, (t0-t3) after 6 month p=0.445; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.24, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.43; Pain characteristics: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p=0.905, (t0-t3) after 6 month p= 0.761; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.09, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.24; Functional interference: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p=0.285, (t0-t3) after 6 month p=0.081; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.21, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.56; Psychosocial aspects: Treatment effect (t0-t2) after 3 month p=0.001, (t0-t3) after 6 month p=0.010; Effect size (t0-t2) after 3 month -0.79, (t0-t3) after 6 month -0.77

|

NR During the trial there were no adverse events.

|

RCT Dropouts: 3 months Ex: 5, C: 8; 6 months Ex: 12, C: 12 Cochrane score 4/7 (downgraded due to lack of blinding and incomplete outcome assessment)

|

|

Taaffe European Urology 2017

|

Design: RCT ACTRN12609000200280 Funding: Public research funds, government National Health and Medical Research Council 534409, Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia, Cancer Council of Western Australia, and Cancer Council of Queensland. Number of centers: NR Country: Australia Setting: Urban n=163 Inclusion dates: 2009 to September 2012

|

Eligibility criteria: Histologically documented PCa; minimum exposure to ADT of 2 mo; without prostate-specific antigen (PSA) evidence of disease activity; anticipated to receive ADT for the subsequent 12 mo Excluded: Bone metastatic disease; musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, or neurological conditions that could inhibit them from exercising; inability to walk 400m or undertake exercise; structured resistance and aerobe training in the previous 3 mo. Mean age: ILRT 68.9 (9.1); ART 69.0 (9.3); 68.4 (9.1) M:F: 163:0 Tumor types: Prostate cancer Tumor stages: localized and nodal metastases Palliative stage: Disease directed treatment There were no significant differences among groups at baseline

|

Intervention: ILRT month 1-12 (impact loading (bounding, skipping, drop jumping, hopping, and leaping activities) + resistance training (chest press, seated row, shoulder press, leg press, leg extension, and leg curl)): twice weekly in University-affiliated exercise clinics; supervised (up to 10 participants); home training twice weekly that consisted of two to four rotations of skipping/hopping/ leaping/drop jumping. Intervention: ART month 1-6: (aerobe (20–30 min of exercise at 60–75% of estimated maximal heart rate using various modes which included walking/jogging and cycling or rowing) + resistance training (as in ILRT)): supervised exercise in the clinic twice weekly; home-based aerobe activity such as walking or cycling with the goal to accumulate 150 min/wk of aerobe activity; month 7-12: home-based maintenance program 12 months Control: DEL month 1-6: (usual care/delayed exercise) were provided with a printed booklet with information about exercise; month 7-12: twice weekly supervised exercise on a cycle ergometer at an intensity of 70% maximal heart rate and flexibility exercises in the clinic.

|

From 0 to 12 months: ILRT 27.9 (20.7) to 22.5 (16.6), ART: 23.4 (18.1) to 17.7 (15.0), DEL: 25.8 (20.2) to 20.3 (15.3)

Vitality: With training, there was no significant interaction (p=0.525); from 0-12 months: ILRT 50.0 (10.8) to 22.5 (16.6), ART: 51.5 (10.7) to 17.7 (15.0), DEL: 50.3 (10.0) to 20.3 (15.3)

|

No other differences for cardiorespiratory fitness. For muscle strength there was a significant interaction with treatment No withdrawals due to adverse effects from exercise; ILRT compressed spinal discs (n=1); ILRT shoulder issues (n=1); ART cardiovascular problems (n=2), with one requiring heart bypass surgery; ART back pain (n=1); DEL difficulty walking (n=1); DEL back surgery (n=1).

|

RCT Dropouts: Three men had missing data for fatigue and one participant had missing data for vitality Cochrane score 3/7 downgraded for blinding, unclear allocation concealment, selective reporting

|

|

Uster Clinical Nutrition 2017

|

Design: RCT NCT01540968 Funding: Non-governmental organization Krebsliga Schweiz (Swiss Cancer Foundation, Switzerland), Number: KFS- 2833-08-2011; Werner und Hedy Berger-Janser Stiftung Number of centers: 1 Country: Switzerland Setting: Cancer center n=58 Inclusion dates: March 2012-October 2014

|

Eligibility criteria: Metastatic or locally advanced tumors; gastrointestinal or lung tract cancer; ECOG <= 2; Life expectancy >6 months Excluded: enteral tube feeding or parenteral nutrition; brain metastases or symptomatic bone metastases; ileus within the last month Mean age: 63.0 (10.1) M:F: 40:18 Tumor types: Metastatic after Colorectal; Oesophago-gastric; NSCLC; SCLC; Pancreas; Others Tumor stages: III/IV Palliative stage: NR At baseline, the groups were well-balanced with regard to demographics, diagnoses, medical characteristics and primary endpoint (p > 0.05).

|