Nefrotoxische medicatie en PC-AKI

Uitgangsvraag

Dient nefrotoxische medicatie te worden gestaakt vooraf aan intravasculaire jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel (CM)-toediening om het risico van PC-AKI te verkleinen?

Aanbeveling

Staak ACE-remmers, angiotensine-II-receptorantagonisten of diuretica niet routinematig vooraf aan intravasculaire jodiumhoudend CM-toediening.

Staak NSAID’s vooraf aan toediening van intravasculair jodiumhoudend CM.

De werkgroep beveelt een nefrologisch consult aan, vooraf aan jodiumhoudend CM-toediening, bij patiënten met een eGFR <30 ml/kg/1,73m2, zodat er op individuele basis kan worden besloten om ACE-remmers, angiotensine II receptorantagonisten, diuretica of nefrotoxische medicatie te continueren of te staken, en de potentiële voor- en nadelen van jodiumhoudend CM-toediening tegen elkaar af te wegen.

Overwegingen

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers has been associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury following intravascular iodine-containing contrast administration. This has led to the perception that withholding these agents is a useful strategy to prevent acute kidney injury. However, there is insufficient scientific evidence to support this hypothesis.

ACE-inhibitors and Angiotensin-II Receptor Blockers.

First of all, the only two randomized controlled trials regarding this research question address discontinuation of ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin-II receptor blockers.

Second, the two RCTs that have been performed included a small number of patients and restricted their inclusion to patients undergoing coronary angiography/catheterization. Hence, no information is available on the effect of withholding or continuing ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers in chronic kidney disease patients undergoing intravenous contrast enhanced-CT.

An important aspect that should be taken into consideration is the fact that observational studies showing an association between the risk of PC-AKI and the use of diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers might have been confounded by the indication for the use of these drugs. Patients with congestive heart failure, for instance, are at increased risk of developing PC-AKI and are likely to use ACE-inhibitors.

Finally, and most importantly, ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are not nephrotoxic, although they are referred to as nephrotoxic drugs by guidelines and in literature. ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers inhibit angiotensin-induced post-glomerular vasoconstriction. As a result, these drugs may improve medullary perfusion and may therefore be nephroprotective under certain conditions. However, post-glomerular vasoconstriction increases filtration pressure. Thus, if glomerular filtration depends on post-glomerular filtration, which may be the case in patients with renal artery stenosis, hypovolemia or very poor cardiac output, the use ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers can reduce glomerular filtration, a fully reversible process. Thus, patients with very low glomerular reserve capacity which are dependent of post-glomerular vasoconstriction may benefit from a temporary discontinuation of ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers regarding maintenance of glomerular filtration. Anyway, hypovolemia should always be corrected before administering iodine-containing CM. The working group therefore considers nephrology consultation before administering iodine-containing CM in patients with eGFR <30 ml/kg/1.73m2 crucial to individualize continuation or discontinuation of ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers.

NSAIDs

To our knowledge, no RCTs have been performed on cessation of diuretics or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Thus, an evidence based recommendation cannot be given. However, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have proven to be nephrotoxic, because they inhibit compensatory post-glomerular vasodilation, on which medullary perfusion is dependent in conditions with diminished glomerular flow such as heart failure. Despite the lack of evidence, it may be considered to discontinue non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing contrast administration. The working group therefore considers nephrology consultation before administering iodine-containing CM in patients with eGFR <30 ml/kg/1.73m2 crucial to individualize continuation or discontinuation of NSAIDs.

Diuretics

No RCTs were found comparing the discontinuation of diuretics to continuation of diuretics as sole intervention in the setting of intravascular contrast. However, several RCTs have been published comparing the use of diuretics in combination with different types of controlled hydration to hydration alone in patients receiving intra-arterial contrast for CAG and or PCI. These studies are reported in the chapter on optimal hydration strategy. In most of the studies, the combination of diuretics and controlled hydration was superior in preventing the risk of PC-AKI indirectly supporting the concept that the use of diuretics before using intravascular contrast does not increase the risk of PC-AKI if adequate hydration is performed.

Of note, diuretics are not nephrotoxic per se. However, the use of diuretics may hamper glomerular filtration if their use causes hypovolemia and glomerular reserves are diminished. In these cases, the additional use of iodine-containing CM may reduce glomerular filtration. Finally, withholding diuretics might increase the risk of acute heart failure in chronic users of these agents, especially in the setting of preventive hydration that is given to patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing intravascular contrast administration. The working group therefore considers nephrological consultation before administering iodine-containing CM in patients with eGFR <30 ml/kg/1.73m2 crucial to individualize continuation or discontinuation of diuretics.

Other nephrotoxic drugs

No RCT’s have been published on the effect of discontinuation of PC-AKI on the reduction of PC-AKI. Thus, there is no evidence whether discontinuation of nephrotoxic drugs will reduce the incidence of PC-AKI. Their combined use with iodine-containing CM could however increase the risk of harm to the kidney. The working group therefore recommends to consider other imaging techniques that avoid the use of iodine-containing CM and recommends nephrological consultation before administering iodine-containing CM in patients with eGFR <30 ml/kg/1.73m2 to individualize continuation or discontinuation of nephrotoxic drugs and weigh this against the potential benefits and harm of the administration of iodine-containing CM.

In summary, the lack of evidence of a protective effect of withholding diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, combined with the fact that withholding diuretics or ACE-inhibitors might be associated with an increased risk of acute heart failure, has resulted in the recommendation not to withhold these drugs in chronic kidney disease patients receiving intravascular contrast agents. However, the working group considers nephrological consultation before administering iodine-containing CM in patients with eGFR <30 ml/kg/1.73m2 crucial to individualize continuation or discontinuation of these specific medications.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers has been associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury in patients receiving intravascular iodine-containing contrast. Several international guidelines therefore advise to withhold these drugs in patients undergoing elective procedures requiring intravascular contrast administration. Implementation is however difficult, discontinuation is not without risk and whether withholding these agents in the day(s) prior to or following iodine-containing contrast administration protects patients from developing adverse renal outcomes such as acute kidney injury, long term renal injury, or a need for dialysis is an issue of debate.

The present literature search aims to answer the following questions:

- Do withholding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers 24-48 hours prior to CM-enhanced CT reduce the risk of adverse renal outcomes?

- Do withholding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers 24-48 hours following CM-enhanced CT reduce the risk of adverse renal outcomes?

- Do withholding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers 24-48 hours prior to elective cardiovascular diagnostic or therapeutic contrast procedures reduce the risk of adverse renal outcomes?

- Do withholding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers 24-48 hours following elective cardiovascular diagnostic or therapeutic contrast procedures reduce the risk of adverse renal outcomes?

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

There is a low level of evidence that discontinuation of ACE-inhibitors (on day of procedure up to 24 hours after procedure) does not reduce the risk of post contrast acute kidney injury compared to continuing ACE-inhibitor use around angiography in patients with chronic kidney disease.

(Rosenstock, 2008) |

|

Low GRADE |

There is a low level of evidence that discontinuation of Angiotensin-II receptor blockers (24 hours before procedure up to 96 hours after procedure) does not reduce the risk of post contrast acute kidney injury compared with continuing Angiotensin II receptor blocker use around cardiac catheterization in patients with moderate kidney insufficiency.

(Bainey, 2015) |

|

Very Low GRADE |

There is a very low level of evidence that continuation of Angiotensin II receptor blockers (24 hours before procedure up to 96 hours after procedure) could be associated with more adverse events compared to discontinuation of Angiotensin II blocker use around cardiac catheterization in patients with moderate kidney insufficiency.

(Bainey, 2015) |

|

There is no evidence that discontinuation of NSAIDs or diuretics before the administration of intravascular contrast in euvolemic patients reduces the risk of post contrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI) compared with continuation of diuretics. |

Samenvatting literatuur

ACE inhibitors and Angiotensin-II Receptor Blockers

Description of studies

This literature summary describes 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Bainey, 2015; Rosenstock, 2008).

Rosenstock, 2008 compared discontinuation of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitors to continuation of ACE-inhibitors prior to coronary angiography in terms of kidney damage. A total of 283 patients were enrolled in this study of whom 220 patients were randomized: 113 chronic (>2 months) ACE-inhibitor users who continued their therapy; 107 chronic ACE-inhibitor users who discontinued ACE-inhibitors (withheld the morning of procedure to 24 hours after procedure. A third group of 68 patients who were not using ACE-inhibitors was also followed. All patients had chronic kidney disease (eGFR 15-60ml/min/1.73m2). Patients were hydrated based on the institution’s policies and medication such as metformin and diuretics were held prior to the procedure in all patients. Creatinine values were measured at baseline and 24 hours post-procedure; further measurements were at the discretion of the treating physician.

Bainey, 2015 compared discontinuation of Angiotensin II blockade medication (combination of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB)) versus continuation of Angiotensin II blockade medication prior to cardiac catheterization in terms of kidney damage.

Bainey, 2015 included 208 patients with moderate renal insufficiency (≥ 150 µmol/l within 3 months or ≥ 132 µmol/l within one week of cardiac catheterisation). Use of Angiotensin II blockers were stopped in 106 patients and continued in 102 patients. In the discontinuation group, Angiotensin II medication was stopped at least 24 hours prior to catheterisation and restarted 96 hours post procedurally. Both groups received intravenous normal saline at 3 mL/kg/hour for at least an hour before contrast injection, intravenous normal saline at 1 mL/kg/hour during contrast exposure and 6 hours after the procedure or until discharge. Serum creatinine levels were obtained 72±24 hours post procedurally.

No literature was found describing discontinuation of NSAIDs or diuretics prior to CM-enhanced CT in patients with impaired kidney function.

Results

Rosenstock, 2008

The incidence of PC-AKI in the 113 ACE-inhibitor users in whom medication was continued was 6.2% (95% CI: 2.5 to 12%). The incidence of PC-AKI was 3.7% (95% CI: 1 to 9%) in the discontinuation group (n=107) and 6.3% in the ACE-inhibitor naïve group (n=68). The differences in incidences were not significant (p=0.66).

Bainey, 2015

PC-AKI occurred in 18.4% of the patients who continued Angiotensin II blockers and in 10.9% of the patients in whom Angiotensin II receptor blockers were discontinued (hazard ratio (HR) of discontinuation group: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.30 to 1.19; p=0.16). The change in mean serum creatinine was 27 (SD 44) µmol/L in the group that continued Angiotensin II blockers and 9 (SD 27) µmol/L, in the patients who discontinued the drug, p=0.03. There was 1 death (1%), 1 ischemic stroke (1%) and 3 patients were re-hospitalized for cardiovascular cause (3%) in the group where ACE-inhibitors were continued; versus no clinical events in the discontinuation group (p=0.03, study size not powered for this analysis).

Quality of evidence

For Rosenstock, 2008 the quality of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels due to indirectness (only kidney function after 24 hours available).

For Bainey, 2015 the quality of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels due to imprecision and limitations in study design and further downgraded for the outcomes mortality, dialysis and cardiovascular events for 1 more level for imprecision (study underpowered to draw conclusions about this outcome).

Due to heterogeneity in types of medications and interventions for which contrast administration was used, it was not possible to pool the study results.

Zoeken en selecteren

To answer our clinical question a systematic literature analysis was performed for the following research questions:

- Do withholding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers 24-48 hours prior to CE-CT reduce the risk of adverse renal outcomes?

- Do withholding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers 24-48 hours following CE-CT reduce the risk of adverse renal outcomes?

- Do withholding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers 24-48 hours prior to elective cardiovascular diagnostic or therapeutic contrast procedures reduce the risk of adverse renal outcomes?

- Do withholding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers 24-48 hours following elective cardiovascular diagnostic or therapeutic contrast procedures reduce the risk of adverse renal outcomes?

P (patient category) Patients with mild to moderate chronic kidney disease undergoing radiological examinations with intravascular contrast media and using diuretics, NSAIDS, angiotensin receptor blockers, or ACE-inhibitors).

I (intervention) Cessation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers prior and/or after radiological examinations with contrast media.

C (comparison) Continuation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers prior and/or after radiological examinations with contrast media.

O (outcome) Post-contrast acute kidney injury, start dialysis, decrease in residual kidney function, adverse events, mortality.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered PC-AKI, mortality, start dialysis, decrease in residual kidney function, critical outcome measures for the decision making process and adverse effects of withholding medication important outcome measures for the decision making process.

A difference of at least 10% in relative risk was defined as a clinically relevant difference; by expert opinion of the working group (no literature was available to substantiate the decision). To illustrate, if PC-AKI occurs with an incidence of 10% in the patient population, a difference of 10% of relative risk would mean a difference of 1% in absolute risk. Thus the number needed to treat would be 100, ergo: a doctor would need to treat 100 patients to prevent one case of PC-AKI. When the incidence of PC-AKI is 5%, a difference of 10% in relative risk would mean a difference of 0.5% in absolute risk, and a number needed to treat of 200.

Search and select (method)

The data bases Medline (OVID), Embase and the Cochrane Library were searched from January 2000 to 27th of August 2015 using relevant search terms for systematic reviews (SRs), randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies (OBS). A search update was performed on the 3rd of May 2017. Search terms are shown under the Tab “Verantwoording”. The literature search procured 379 hits. The initial search contained 320 hits, and the search update produced another 49 hits.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Adult patients who underwent diagnostic or therapeutic procedures requiring intravascular administration of contrast media (CE-CT and elective cardiovascular diagnostic or therapeutic contrast procedures) and who were using diuretics, NSAIDs, angiotensin receptor blockers, or ACE-inhibitors.

- Patients with impaired kidney function, at least eGFR <60 ml/min/1,73m2 or serum creatinine ≥ 132 µmol/l.

- The use of NSAIDs, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers was stopped at least 24 hours prior to radiological examination using contrast media OR nephrotoxic medication was discontinued at least 24 hours following radiological examination using contrast media.

- At least one of the outcome measures was described: PC-AKI, start dialysis, decrease in residual kidney function, mortality.

Based on title and abstract a total of 39 studies were selected, all from the initial search After examination of full text a total of 37 studies were excluded and 2 studies definitely included in the literature summary.

Two studies were included in the final literature analysis, the most important study characteristics and results were included in the evidence tables. The evidence tables and assessment of individual study quality are included.

Referenties

- Bainey KR, Rahim S, Etherington K, Et al. Effects of withdrawing vs continuing renin-angiotensin blockers on incidence of acute kidney injury in patients with renal insufficiency undergoing cardiac catheterization: Results from the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor/Angiotensin Receptor Blocker and Contrast Induced Nephropathy in Patients Receiving Cardiac Catheterization (CAPTAIN) trial. Am Heart J. 2015; Jul;170(1):110-6.

- Rosenstock JL, Bruno R, Kim JK, et al. The effect of withdrawal of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers prior to coronary angiography on the incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40(3):749-55.

Evidence tabellen

Table: exclusion after examination of full text

|

Author and year |

Reasons for exclusion |

|

Aspelin, 2014 |

Exam questions, not an original article |

|

Baris, 2013 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Cirit, 2006 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Del Veccio |

Narrative review |

|

Diogo, 2010 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Duan, 2015 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Goo, 2014 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Gu, 2013 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Gu, 2015 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Jo, 2015 |

Only abstract available (full tekst nogmaals aangevraagd bij Sanne, aan de hand hiervan alsnog inclusie mogelijk) |

|

Kalyesubula, 2014 |

Narrative review |

|

Kellum, 2001 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Kiski, 2010 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Lapi, 2014 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Li, 2011 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Li, 2012 |

Narrative review |

|

Li, 2012b |

Only abstract available (full tekst nogmaals aangevraagd bij Sanne, aan de hand hiervan alsnog inclusie mogelijk) |

|

Marenzi, 2012 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Mauer, 2002 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Oguzhan, 2013 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Onuigbo, 2008 |

No control group |

|

Onuigbo, 2009 |

Narrative review |

|

Onuigbo, 2012 |

Narrative review |

|

Onuigbo, 2015 |

Editorial comment, not an original article |

|

Patel, 2011 |

Narrative review |

|

Peng, 2015 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Rim, 2012 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Rim, 2013 |

Erratum of Rim, 2012; not an original article |

|

Ryan, 2008 |

Narrative review |

|

Saudan, 2008 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination but started, with the hypothesis that this will prevent kidney injury) |

|

Schetz, 2004 |

Narrative review |

|

Shehata, 2015 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Shemirani, 2012 |

Patients with normal kidney function |

|

Spatz, 2012 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Umruddin, 2012 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Wolak, 2013 |

Patients with normal kidney function |

|

Wu, 2015 |

Does not fulfill selection criteria (nephrotoxic medication is not stopped prior to radiological examination with intravasal contrast) |

|

Zhou, 2013 |

Narrative review |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question:

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Bainey, 2015 |

Permuted block-randomization; computerized intractive voice-response system |

Unlikely |

Unlikelu |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

|

Rosenstock, 2008 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules..

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question:

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Bainey, 2015 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial (pilot)

Setting: outpatients and inpatients

Country: Canada

Source of funding: both commercial and non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria: 1) presented for cardiac catheterization 2) using an ACEi or ARB 3) moderate chronic kidney disease (≥1.7 mg/dL within 3 months or ≥1.5 within one week of cardiac catheterisation)

Exclusion criteria: 1) end-stage renal disease 2) emergency cardiac catheterisation with insufficient time to hold ACEi 3) pulmonary oedema

N total at baseline: 208 Intervention: 106 Control: 102

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 73 ± 9 C: 72 ± 8

Sex: I: 74% M C: 73 % M

Groups comparable at baseline? yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Angiotensin II blockade medication was stopped at least 24 hours prior to catheterisation and restarted after up to 96 hours after.

Intravenous normal saline at 3 mL/kg/hour for at least an hour before contrast injection, intravebous normal saline at 1 mL/kg/hour during contrast exposure and 6 hours after the procedure or until discharge.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No discontinuation of angiotensin II blockade medication

Intravenous normal saline at 3 mL/kg/hour for at least an hour before contrast injection, intravebous normal saline at 1 mL/kg/hour during contrast exposure and 6 hours after the procedure or until discharge.

|

Length of follow-up: 72±24 hours

Loss-to-follow-up: not reported

Incomplete outcome data: not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mean serum creatinine change I: 0.1±0.3 C: 0.3±0.5 P=0.03

Contrast induced AKI: I: 10.9% C: 18.4% HR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.30 – 1.19, p=0.16

Mortality: I: 0 (0%) C: 1 (1%)

Ischemic stroke: I: 0 (0%) C: 1 (1%)

Rehospitalization for cardiovascular cause: I: 0 (0%) C: 3 (2%)

|

Contrast induced AKI defined as an absolute rize in serum creatinine of ≥25% (44µmol/L) from baseline and/or a relative rise of serum creatinine of ≥25% compared with baseline at any time between 48 and 96 hours post procedure.

|

|

Rosenstock, 2008 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting: unclear

Country: unclear

Source of funding: unclear |

Inclusion criteria: 1) patients undergoing coronary angiography 2) chronic use (>2 months) of ACE-inhibitor

Exclusion criteria: unclear

N total at baseline: Intervention: 107 Control: 113 ACE-naïve patients: 68

Important prognostic factors2: unclear For example age ± SD: I: C:

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline? Incidence of diabetes and hypertension was significantly lower in the ACE-naïve group |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Discontinuation of ACE inhibitor use Morning of procedure up to 24 hours after coronary angiography

Patients were hydrated based on the institution’s policies and medications such as diuretics and metformin were held prior to procedure |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

1) No Discontinuation of ACE inhibitor use around coronary angiography

2) ACE-inhibitor naïve patients undergoing coronary angiography

Patients were hydrated based on the institution’s policies and medications such as diuretics and metformin were held prior to procedure |

Length of follow-up: 24 hours

Loss-to-follow-up: unclear

Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: unclear

Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Incidence of CIN

ACE-inhibitors discontinued: 3.7% ACE-inhibitors not discontinued: 6.2% ACE-inhibitor naïve group: 6.3% P=0.66 |

Measurements of creatinine 24 hours post-procedure; various ACE-inhibitor subgroups not compared due to small sample size. |

|

1st author, year of publication |

Type of study:

Setting:

Country:

Source of funding: |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: Control:

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: C:

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

|

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe) |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

|

|

|

1st author, year of publication |

Type of study:

Setting:

Country:

Source of funding: |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: Control:

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: C:

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

|

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe) |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

|

|

ACEi: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; AKI: acute kidney injury; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; CIN: contrast induced nephropathy; HR: hazard ratio

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 08-01-2018

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-11-2017

Validity

The board of the Radiological Society of the Netherlands will determine at the latest in 2023 if this guideline (per module) is still valid and applicable. If necessary, a new working group will be formed to revise the guideline. The validity of a guideline can be shorter than 5 years, if new scientific or healthcare structure developments arise, that could be seen as a reason to commence revisions. The Radiological Society of the Netherlands is considered the keeper of this guideline and thus primarily responsible for the actuality of the guideline. The other scientific societies that have participated in the guideline development share the responsibility to inform the primarily responsible scientific society about relevant developments in their field.

Initiative

Radiological Society of the Netherlands

Authorization

The guideline is submitted for authorization to:

- Association of Surgeons of the Netherlands

- Dutch Association of Urology

- Dutch Federation of Nephrology

- Dutch Society Medical Imaging and Radiotherapy

- Dutch Society of Intensive Care

- Netherlands Association of Internal Medici

- Netherlands Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Netherlands Society of Cardiology

- Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

- Radiological Society of the Netherlands

Algemene gegevens

General Information

The guideline development was assisted by the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (https://www.kennisinstituut.nl) and was financed by the Quality Funds for Medical Specialists (Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten: SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Goal of the current guideline

The aim of the Part 1 of Safe Use of Iodine-containing Contrast Media guidelines is to critically review the present recent evidence with the above trend in mind, and try to formulate new practical guidelines for all hospital physicians to provide the safe use of contrast media in diagnostic and interventional studies. The ultimate goal of this guideline is to increase the quality of care, by providing efficient and expedient healthcare to the specific patient populations that may benefit from this healthcare and simultaneously guard patients from ineffective care. Furthermore, such a guideline should ideally be able to save money and reduce day-hospital waiting lists.

Users of this guideline

This guideline is intended for all hospital physicians that request or perform diagnostic or interventional radiologic or cardiologic studies for their patients in which CM are involved.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Working group

Cobbaert C., clinical chemist, Leiden University Medical Centre (member of advisory board from September 2015)

Danse P., interventional cardiologist, Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem

Dekker H.M., radiologist, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen

Geenen R.W.F., radiologist, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep (NWZ), Alkmaar/Den Helder

Hoogeveen E.K., nephrologist, Jeroen Bosch Hospital, ‘s-Hertogenbosch

Kooiman J., research physician, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden

Oudemans - van Straaten H.M., internist-intensive care specialist, Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam

Pels Rijcken T.H., interventional radiologist, Tergooi, Hilversum

Sijpkens Y.W.J., nephrologist, Haaglanden Medical Centre, The Hague

Vainas T., vascular surgeon, University Medical Centre Groningen (until September 2015)

van den Meiracker A.H., internist-vascular medicine, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam

van der Molen A.J., radiologist, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden (chairman)

Wikkeling O.R.M., vascular surgeon, Heelkunde Friesland Groep, location: Nij Smellinghe Hospital, Drachten (from September 2015)

Advisory board

Demir A.Y., clinical chemist, Meander Medical Center, Amersfoort, (member of working group until September 2015)

Hubbers R., patient representative, Dutch Kidney Patient Association

Mazel J., urologist, Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem

Moos S., resident in Radiology, HAGA Hospital, The Hague

Prantl K., Coordinator Quality & Research, Dutch Kidney Patient Association

van den Wijngaard J., resident in Clinical Chemistry, Leiden University Medical Center

Methodological support

Boschman J., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from May 2017)

Burger K., senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (until March 2015)

Harmsen W., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from May 2017)

Mostovaya I.M., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists

Persoon S., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (March 2016 – September 2016)

van Enst A., senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from January 2017)

Belangenverklaringen

Conflicts of interest

The working group members have provided written statements about (financially supported) relations with commercial companies, organisations or institutions that are related to the subject matter of the guideline. Furthermore, inquiries have been made regarding personal financial interests, interests due to personal relationships, interests related to reputation management, interest related to externally financed research and interests related to knowledge valorisation. The statements on conflict of interest can be requested at the administrative office of the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists and are summarised below.

|

Member |

Function |

Other offices |

Personal financial interests |

Personal relationships |

Reputation management |

Externally financed research |

Knowledge-valorisation |

Other potential conflicts of interest |

Signed |

|

Workgroup |

|||||||||

|

Burger |

Advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Cobbaert |

Member, physician clinical chemistry |

Head of clinical chemistry department in Leiden LUMC. Tutor for post-academic training of clinical chemists, coordinator/host for the Leiden region Member of several working groups within the Dutch Society for Clinical Chemistry and member of several international working groups for clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

Member of several working groups within the Dutch Society for Clinical Chemistry and member of several international working groups for clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Danse |

Member, cardiologist |

Board member committee of Quality, Dutch society for Cardiology (unpaid) Board member Conference committee DRES (unpaid) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Dekker |

Member, radiologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Geenen |

Member, radiologist |

Member Contrast Media Safety Committee of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (unpaid, meetings are partially funded by CM industry))) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Has been a public speaker during symposia organised by GE Healthcare about contrast agents (most recently in June 2014) |

Yes |

|

Hoogeveen |

Member, nephrologist |

Member of Guideline Committee of Dutch Federation of Nephrology |

None |

None |

Member of Guideline Committee of Dutch Society for Nephrology |

Grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation to study effect of fish oil on kidney function in post-MI patients |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Kooiman |

Member, research physician |

Resident in department of gynaecology & obstetrics |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Mostovaya |

Advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Oudemans – van Straaten |

Member, intensive care medical specialist Professor Intensive Care |

none |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Pels Rijcken |

Member, interventional radiologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Sijpkens |

Member, nephrologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Vainas |

Member, vascular surgeon |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Van den Meiracker |

Member, internist vascular medicine |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Van der Molen |

Chairman, radiologist |

Member Contrast Media Safety Committee of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (unpaid,CMSC meetings are partially funded by CM industry)) |

None |

None |

Secretary section of Abdominal Radiology; Radiological Society of the Netherlands (until spring of 2015) |

None |

None |

Receives Royalties for books: Contrast Media Safety, ESUR guidelines, 3rd ed. Springer, 2015 Received speaker fees for lectures on CM safety by GE Healthcare, Guerbet, Bayer Healthcare and Bracco Imaging (2015-2016) |

Yes |

|

Wikkeling |

Member, vascular surgeon |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Advisory Board |

|||||||||

|

Demir |

Member, physician clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Hubbers |

Member, patient’s representative, Dutch Society of Kidney Patients |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Mazel |

Member, urologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Prantl |

Member, policy maker, Dutch Society of Kidney Patients |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Van den Wijngaard |

Member, resident clinical chemistry |

Reviewer for several journals (such as American Journal of Physiology) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Patients’ perspective was represented, firstly by membership and involvement in the advisory board of a policy maker and a patients’ representative from the Dutch Kidney Patient Association. Furthermore, an online survey was organized by the Dutch Kidney Patient Association about the subject matter of the guideline. A summary of the results of this survey has been discussed during a working group meeting at the beginning of the guideline development process. Subjects that were deemed relevant by patients were included in the outline of the guideline. The concept guideline has also been submitted for feedback during the comment process to the Dutch Patient and Consumer Federation, who have reported their feedback through the Dutch Kidney Patient Association.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In the different phases of guideline development, the implementation of the guideline and the practical enforceability of the guideline were taken into account. The factors that could facilitate or hinder the introduction of the guideline in clinical practice have been explicitly considered. The implementation plan can be found with the Related Products. Furthermore, quality indicators were developed to enhance the implementation of the guideline. The indicators can also be found with the Related Products.

Werkwijze

AGREE

This guideline has been developed conforming to the requirements of the report of Guidelines for Medical Specialists 2.0; the advisory committee of the Quality Counsel. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (www.agreetrust.org), a broadly accepted instrument in the international community and on the national quality standards for guidelines: “Guidelines for guidelines” (www.zorginstituutnederland.nl).

Identification of subject matter

During the initial phase of the guideline development, the chairman, working group and the advisor inventory the relevant subject matter for the guideline. Furthermore, an Invitational Conference was organized, where additional relevant subjects were suggested by the Dutch Kidney Patient Association, Dutch Society for Emergency Physicians, and Dutch Society for Urology. A report of this meeting can be found in Related Products.

Clinical questions and outcomes

During the initial phase of guideline development, the chairman, working group and advisor identified relevant subject matter for the guideline. Furthermore, input was acquired for the outline of the guideline during an Invitational Conference. The working group then formulated definitive clinical questions and defined relevant outcome measures (both beneficial land harmful effects). The working group rated the outcome measures as critical, important and not important. Furthermore, where applicable, the working group defined relevant clinical differences.

Strategy for search and selection of literature

For the separate clinical questions, specific search terms were formulated and published scientific articles were sought after in (several) electronic databases. Furthermore, studies were looked for by cross-referencing other included studies. The studies with potentially the highest quality of research were looked for first. The working group members selected literature in pairs (independently of each other) based on title and abstract. A second selection was performed based on full text. The databases search terms and selection criteria are described in the modules containing the clinical questions.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Individual studies were systematically assessed, based on methodological quality criteria that were determined prior to the search, so that risk of bias could be estimated. This is described in the “risk of bias” tables.

Summary of literature

The relevant research findings of all selected articles are shown in evidence tables. The most important findings in literature are described in literature summaries. When there were enough similarities between studies, the study data were pooled.

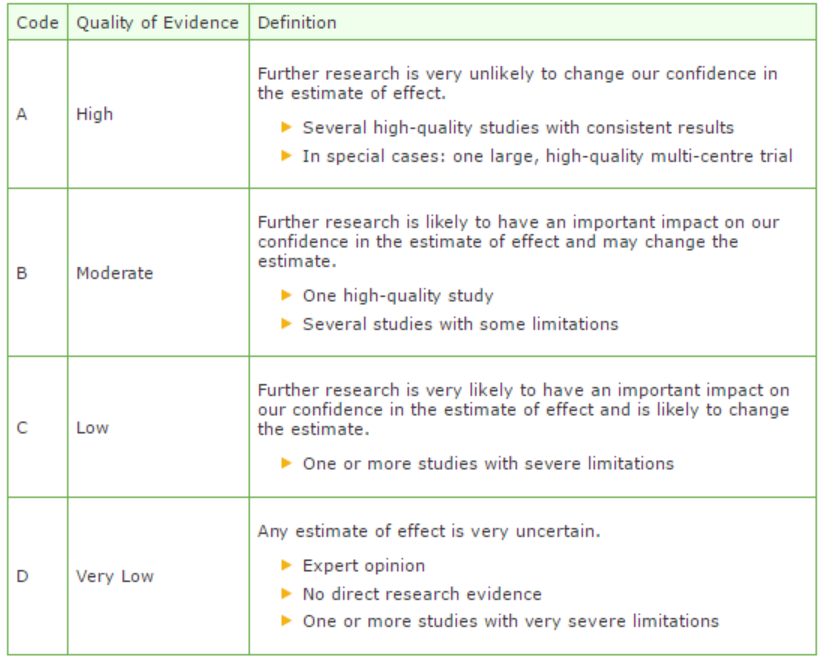

Grading the strength of scientific evidence

A) For intervention questions

The strength of the conclusions of the scientific publications was determined using the GRADE-method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/) (Atkins, 2004).

GRADE defines four gradations for the quality of scientific evidence: high, moderate, low or very low. These gradations provide information about the amount of certainty about the literature conclusions. (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook/).

B) For diagnostic, etiological, prognostic or adverse effect questions, the GRADE-methodology cannot (yet) be applied. The quality of evidence of the conclusion is determined by the EBRO method (van Everdingen, 2004)

Formulating conclusion

For diagnostic, etiological, prognostic or adverse effect questions, the evidence was summarized in one or more conclusions, and the level of the most relevant evidence was reported. For intervention questions, the conclusion was drawn based on the body of evidence (not one or several articles). The working groups weighed the beneficial and harmful effects of the intervention.

Considerations

Aspects such as expertise of working group members, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities, and organization of healthcare aspects are important to consider when formulating a recommendation. These aspects were discussed in the paragraph Considerations.

Formulating recommendations

The recommendations answer the clinical question and were based on the available scientific evidence and the most relevant considerations.

Constraints (organization of healthcare)

During the development of the outline of the guideline and the rest of the guideline development process, the organization of healthcare was explicitly taken into account. Constraints that were relevant for certain clinical questions were discussed in the Consideration paragraphs of those clinical questions. The comprehensive and additional aspects of the organization of healthcare were discussed in a separate chapter.

Development of quality indicators

Internal (meant for use by scientific society or its members) quality indicators are developed simultaneously with the guideline. Furthermore, existing indicators on this subject were critically appraised; and the working group produces an advice about such indicators. Additional information on the development of quality indicators is available by contacting the Knowledge Institute for Medical Specialists. (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl).

Knowledge Gaps

During the development of the guideline, a systematic literature search was performed the results of which help to answer the clinical questions. For each clinical question the working group determined if additional scientific research on this subject was desirable. An overview of recommendations for further research is available in the appendix Knowledge Gaps.

Comment- and authorisation phase

The concept guideline was subjected to commentaries by the involved scientific societies. The commentaries were collected and discussed with the working group. The feedback was used to improve the guideline; afterwards the working group made the guideline definitive. The final version of the guideline was offered for authorization to the involved scientific societies, and was authorized.

References

Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, et al. GRADE Working Group. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004 Dec 22;4(1):38.

Van Everdingen JJE, Burgers JS, Assendelft WJJ, et al. Evidence-based richtlijnontwikkeling. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. Houten, 2004

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Search terms |

Total |

|

|

1 exp Contrast Media/ or ((contrast adj3 iodine) or (contrast adj3 medi*)).ti,ab. (112523) 2 exp Kidney Diseases/ or (((kidney or renal) adj2 (disease* or injur* or failure*)) or nephropath* or (renal adj2 (insufficienc* or function* or disease* or failure*))).ti,ab. (537836) 3 (((contrast* or ci) adj2 (nephropath* or 'kidney injury' or aki or nephrotoxicity)) or cin or ciaki).ti,ab. (9122) 4 1 and 2 (8979) 10 3 or 4 (16547) 12 exp "Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists"/ (18363) 13 exp Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/ (40094) 14 exp Diuretics/ (72995) 15 exp Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal/ (164802) 16 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 (279958) 17 ((Angiotensin* adj3 (Antagonist or Inhibitor* or blocker*)) or Diuretic* or "Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Agent*" or NSAID* or (nephrotoxic adj3 medic*)).ti,ab. (74424) 18 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 17 (307695) 19 10 and 18 (641) 20 limit 19 to (yr="2000 -Current" and (dutch or english)) (266) 21 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (249387) 22 20 and 21 (26) - 25 uniek 23 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1512514) 24 20 and 23 (75) 25 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective.tw. or prospective.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ [Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies] (2216587) 26 20 and 25 (81) 27 24 or 26 (128) 28 27 not 22 (109) – 107 uniek |

320 |

|

|

'contrast induced nephropathy'/exp/dm_pc OR ((contrast* OR ci) NEAR/2 (nephropath* OR 'kidney injury' OR aki OR nephrotoxicity)):ab,ti OR ciaki:ab,ti OR ('contrast medium'/exp OR (contrast NEAR/3 iodine):ab,ti OR (contrast NEAR/3 medi*):ab,ti AND ('kidney disease'/exp OR 'kidney function'/exp OR (kidney NEAR/2 (disease* OR injur* OR failure*)):ab,ti OR nephropath*:ab,ti OR (renal NEAR/2 (insufficienc* OR function* OR disease* OR failure*)):ab,ti))

AND ('angiotensin receptor antagonist'/exp/mj OR 'dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase inhibitor'/exp/mj OR 'diuretic agent'/exp/mj OR 'nonsteroid antiinflammatory agent'/exp/mj OR (angiotensin* NEAR/3 (antagonist OR inhibitor* OR blocker*)):ab,ti OR diuretic*:ab,ti OR 'non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent':ab,ti OR 'non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents':ab,ti OR nsaids:ab,ti OR (nephrotoxic NEAR/3 medic*):ab,ti)

AND ([dutch]/lim OR [english]/lim) AND [embase]/lim AND [2000-2015]/py

'meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psychlit:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR (systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti OR (meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de NOT ('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp NOT 'human'/exp)) (38) – 26 uniek

'clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it

OR 'clinical study'/exp NOT 'conference abstract':it (225) – 162 uniek |