Hydratie en complicaties

Uitgangsvraag

Welke hydratiestrategie dient te worden toegepast bij patiënten die intravasculair jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel (CM)-toediening ondergaan en een hoog PC-AKI risico hebben?

Subvragen:

- Is er een significant verschil in de incidentie van PC-AKI bij hydratie versus geen hydratie?

- Is er een significant verschil in de incidentie van PC-AKI bij intraveneuze NaCl versus NaHCO3?

- Is er een significant verschil in de incidentie van PC-AKI bij intraveneuze prehydratie (alleen) versus pre- en posthydratie (gecombineerd)?

- Is er een significant verschil in de incidentie van PC-AKI bij orale versus intraveneuze pre- en posthydratie?

- Is er een significant verschil in de incidentie van PC-AKI bij patiënten die gecontroleerde diurese ondergaan versus standaard hydratieschema’s?

Aanbeveling

Aanbeveling-1

Zorg voor een normale hydratie status voorafgaand aan toediening van jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel, ongeacht de eGFR. Corrigeer hypovolemie met intraveneuze NaCl 0.9% of Ringer’s lactaat.

Vermijd zo veel mogelijk de toediening van intravasculair jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel bij patiënten met dehydratie/hypovolemie.

Overweeg posthydratie bij twijfel over adequate hydratiestatus (1 ml/kg/uur gedurende 4 – 6 uur, of 500 ml, na contrasttoediening, bijv. NaHCO3 1.4%).

Aanbeveling-2

Voer zonder vertraging acute, niet uitstelbare diagnostiek uit bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten. Laat beeldvorming in deze situatie voorgaan boven prehydratie, of afronding van ingezette prehydratie, ter preventie van PC-AKI.

Start hydratie vóór de procedure bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten met eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 die intra-arterieel jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel krijgen.

Als starten vóór de procedure niet mogelijk is, begin dan de hydratie bij aanvang van de procedure.

Continueer hydratie tot het eindpunt van het hydratieschema, volgens de overige aanbevelingen in deze module.

Aanbeveling-3

Beschouw het risico op PC-AKI verhoogd bij intra-arteriële contrastmiddel toediening met first-pass renale blootstelling aan jodiumhoudende contrastmiddelen.

Definieer first-pass renale blootstelling als intra-arteriële contrasttoediening binnen:

- Linkerharthelft en kransslagaders.

- aorta thoracalis.

- suprarenale aorta abdominalis.

- arteria renalis.

Beschouw overige vormen van intra-arteriële jodiumhoudende contrasttoediening als second-pass renale blootstelling, met een PC-AKI risico vergelijkbaar met intraveneuze contrasttoediening.

Aanbeveling-4

Pas bij patiënten met een eGFR ≥30 ml/min/1.73m2 geen hydratie toe ter preventie van PC-AKI bij intravasculaire toediening van jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel.

Aanbeveling-5

Kies bij patiënten met eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2 voor een alternatief onderzoek zonder jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel als de diagnostische waarde daarvan even goed is.

Pas bij patiënten met eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2 die een intravasculaire procedure ondergaan beschikbare technieken toe om de totale dosis jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel te minimaliseren.

Aanbeveling-6

Pas bij niet-dialyse-afhankelijke patiënten met eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 profylactische hydratie toe ter preventie van PC-AKI bij intraveneuze, of intra-arteriële toediening van jodiumhoudende contrastmiddelen met second-pass renale blootstelling.

Hydreer niet-dialyse-afhankelijke patiënten met eGFR < 30 ml/min/1,73 m² ter preventie van PC-AKI bij geplande intraveneuze of intra-arteriële toediening van jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel met second-pass renale blootstelling volgens één van de volgende schema’s:

- NaHCO₃ 1,4% 3 ml/kg/uur gedurende 1 uur (of 250 ml) vóór contrasttoediening; of

- NaHCO₃ 1,4% 3 ml/kg/uur gedurende 1 uur (of 250 ml) vóór contrasttoediening en NaHCO₃ 1,4% 1 ml/kg/uur gedurende 4–6 uur (of 500 ml) na contrasttoediening.

Aanbeveling-7

Overweeg bij niet-dialyse-afhankelijke patiënten met eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 rondom intra-arteriële toediening van jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel met first-pass renale blootstelling laagdrempelig naast prehydratie ook posthydratie met NaHCO3 toe te passen:

- Vóór contrasttoediening: NaHCO3 1.4% 3 ml/kg/uur gedurende 1 uur (of 250 ml)

- Na contrasttoediening: NaHCO3 1.4% 1 ml/kg/uur gedurende 4 – 6 uur (of 500 ml)

Overweeg te volstaan met prehydratie alleen bij patiënten met goede hydratiestatus, in electieve setting en bij naar verwachting een beperkte totale dosis jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel.

Aanbeveling-8

Pas bij patiënten met chronische nierschade G5 (eGFR <15 ml/min/1.73m2) het hydratieschema individueel aan in overleg met de nefroloog.

Individualiseer in overleg met de cardioloog het hydratieschema bij patiënten met hartfalen, rekening houdend met de actuele hydratietoestand en het risico op decompensatio cordis.

Aanbeveling-9

Pas bij dialyse-afhankelijkheid (hemodialyse of peritoneaal dialyse) géén hydratie toe. Wijzig het dialyseschema niet rondom contrasttoediening; voer géén extra dialyse uit na contrasttoediening, behalve bij aanwijzing voor overhydratie.

Aanbeveling-10

Pas geen hydratie met gecontroleerde diurese toe ter preventie van PC-AKI bij patiënten die (cardiale) angiografie - met of zonder interventie - ondergaan, tenzij in studieverband.

Aanbeveling-11

Pas geen orale hydratie toe als enige preventiemaatregel tegen PC-AKI.

Zie stroomschema

Overwegingen

Balance between desired and undesired effects

All studies

In risk stratification of patients, it is essential to discriminate between CA-AKI (correlative diagnosis) and CI-AKI (causative diagnosis), which requires studies with control populations in which no contrast medium is administered (Davenport, Rad 2020; McDonald RJ, Rad Clin North Am 2024). In addition, the risk might be influenced by the route of iodine-based contrast medium administration: for intravenous (CT-scan) and intra-arterial contrast medium administration with second-pass renal exposure the risk of CI-AKI is similar. For intra-arterial contrast medium administration with first-pass renal exposure, the risk has been suggested to be higher. However, the increased incidence of AKI in this population is likely partly due to comorbidity (Van Der Molen, 2018).

The number of patients with eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2 is absent or very low in most described studies. Only Chen 2008 studied a relatively large subgroup with an average eGFR 28±2 ml/min/1.73m2. Subanalyses for this group were not performed.

In addition to prevention of PC-AKI, optimal nephrology care is important to prevent AKI in patients with impaired renal function. Currently, end stage renal disease (ESRD) is most often caused by atherosclerotic vascular disease, hypertension and type 2 diabetes. The goal in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3 to 5 (non-dialysis) is to slow down deterioration of renal function and prevent or postpone cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. According to the guideline Care of the Patient with Chronic Renal Damage (Chronische nierschade (CNS); 2018) of the Dutch Federation of Nephrology (NFN), the following advice for optimal nephrology care are relevant for the present guideline: avoid nephrotoxic medications, avoid dehydration and hypovolemia, and refer patients to a nephrologist in accordance to section 5.1 of the guideline Care of the Patient with Chronic Renal Damage (Chronische nierschade (CNS); 2018).

Furthermore, independent of eGFR, all patients receiving CM should have a normal hydration status. Apart from preventive hydration, patients should receive adequate volume replacement therapy (with normal saline or Ringer’s lactate) if they have clinical signs of hypovolemia, i.e. hypotension, tachycardia, oliguria and / or loss of renal function.

Q1 Hydration versus no hydration

Three available RCTs comparing hydration with no hydration were performed in the Netherlands and one RCT with two subgroups in China.

Intravenous and intra-arterial iodine-based contrast medium with second pass renal exposure in patients with eGFR 30-60 ml/min/1.73m2

In the larger two Dutch studies (Nijssen 2017 & Timal 2020) iodine-based contrast medium was administered mainly intravenously in stable patients. In the smaller study of Kooiman 2014, contrast medium was administered intravenously in the urgent setting of CTA for suspected pulmonary embolism in patients with eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. For prophylactic hydration, Nijssen 2017 used a short or long pre- and posthydration protocol with NaCl 0.9%, whereas Kooiman 2014 and Timal 2020 from the same study group only used short, one-hour prehydration with NaHCO3 1.4%.

In the available studies with contrast medium administration in elective settings (Nijssen 2017 & Timal 2020), the risk of PC-AKI in the control group without prehydration was relatively low with 2.6%, and 2.7%, respectively which support the notion that the risk of PC-AKI is relatively low in patients with eGFR 30-60 ml/min/1.73m2 when iodine containing contrast medium is administered intravenously or intra-arterially with second-pass renal exposure. Of note, in Nijssen 2017 approximately 50% of the patients nephrotoxic medications including mainly diuretics were temporarily interrupted.

In the setting of urgent CTA for suspected pulmonary embolism, the incidence of PC-AKI was somewhat higher with 9.2% in the control group without prophylaxis.

In the study of Nijssen prophylactic pre- and posthydration with NaCl 0.9% did not decrease the relatively low incidence of PC-AKI (2.7% vs. 2.6%). Subgroup analysis of Nijssen also could not demonstrate an advantage of prophylactic hydration in patients with diabetes, lower eGFR 30-44 ml/min/1.73m2 or intracoronary administration of contrast medium. This study also demonstrated that pre- and posthydration with NaCl 0.9% led to cardiac side effects in 5.5% of the patients (4.0% heart failure, 1.2% arrhythmia, and 0.3% hyponatremia). This risk of serious cardiac problems, combined with the absence of a clear protective effect, makes pre- and posthydration with NaCl 0.9% in these patients an undesirable procedure.

In the studies of Kooiman 2014 and Timal 2020 only prehydration with NaHCO3 1.4% resulted in a slightly, but not significantly lower incidence of PC-AKI after urgent or elective intravenous contrast medium (7.1% vs 9.5% and 1.5% vs 2.7% in the two studies respectively). In Timal 2020 only in the group without prehydration 4 out of 262 (1.5%) had a persistent mean decline of eGFR of 3 ml/min/1.73m2. Because of the small sample size, a type 2 error cannot be excluded. None of the patients receiving prehydration with NaHCO3 developed heart failure. Because of these results, it cannot be fully excluded that prophylactic prehydration for elective or urgent intravenous administration of iodine containing contrast medium has a (very) small protective effect against PC-AKI and irreversible loss of renal function without obvious side effects.

Intra-arterial contrast medium with first pass renal exposure in patients with eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2

Iodine-based contrast medium was given intra-arterially with risk of first pass of contrast medium through the kidneys in approximately 50% of the patients in Nijssen 2017 for predominantly elective CAG or PCI and in Chen 2008 in all patients for elective PCI. For prophylactic hydration, Chen 2008 used a long pre- and posthydration protocol with hypotonic NaCl 0.45%. Nijssen 2017 used a short or long pre- and posthydration protocol with NaCl 0.9%. In the subgroup with low eGFR in Chen 2008, pre-and posthydration with NaCl 0.45% had a significant protective effect against PC-AKI (21.3% vs. 34.04% without hydration) but could not prevent it in the majority of patients (6.67% vs. 6.97%).

In one meta-analysis (Wang, 2019) including 3 RCTs with only a small percentage (13-31%) of patients with renal impairment, hydration with NaCl 0.9% pre- and/or during and after the PCI significantly reduced the risk of PC-AKI in these not always hemodynamically stable STEMI patients (RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.50-0.82). Hydration also tended to reduce the need for renal replacement therapy (RR 0.30; 95% CI 0.08-1.08) and mortality (RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.31-1.08). In all these studies, the infusion rate of hydration was reduced in patients with reduced left ventricular function. In this meta-analysis only the effect of hydration with NaCl 0.9% of the study of Maioli (Maioli, 2011: see below) was included.

Further relevant details of the studies in the meta-analysis are described below (Wang, 2019):

In the RCT of Maioli 2011 with three groups of 150 patients each with 23-31% eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2, one hour pre- and 12 hour posthydration with isotonic NaHCO3 resulted in a significantly lower incidence of PC-AKI (12%) than 12 hours posthydration with NaCl 0.9% (22.5%) and the control group without hydration (27.3%, P for trend =0.001). There was no significant difference between posthydration with saline and no hydration. The risk of PC-AKI was especially lower with hydration volumes >960 ml.

The RCT of Luo 2014 (Luo, 2014) with two groups of 108 patients each, 12 hours posthydration with NaCl 0.9% significantly reduced PC-AKI only in the high and very high Mehran risk groups.

Q2 sodium chloride versus bicarbonate

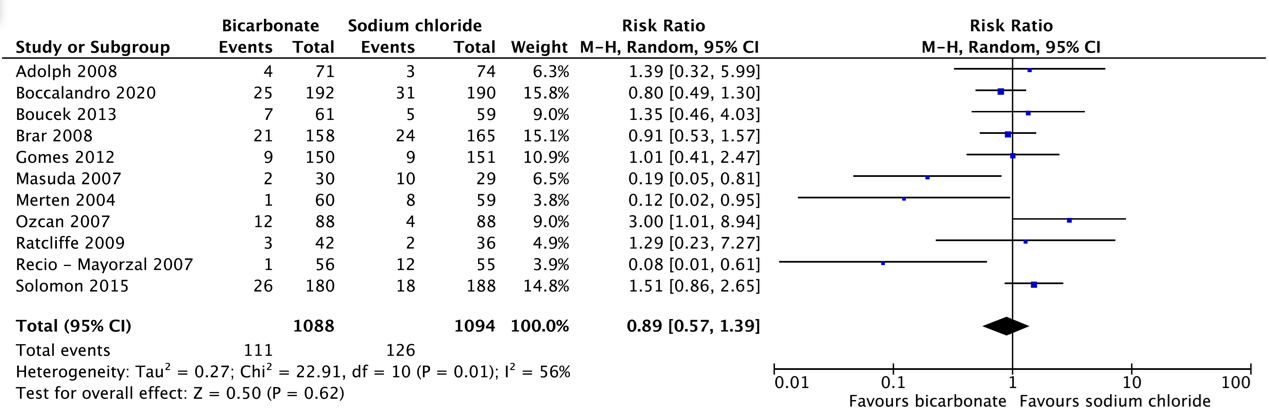

Pooled analysis of all older studies and the new study of Boccolandro 2020 in patients with moderate to severe renal failure indicated that short pre- and post-hydration with isotonic NaHCO3 1.4% or NaCl 0.9% resulted in a comparable incidence of PC-AKI after CAG/PCI (10.1% vs. 11.4%, respectively).

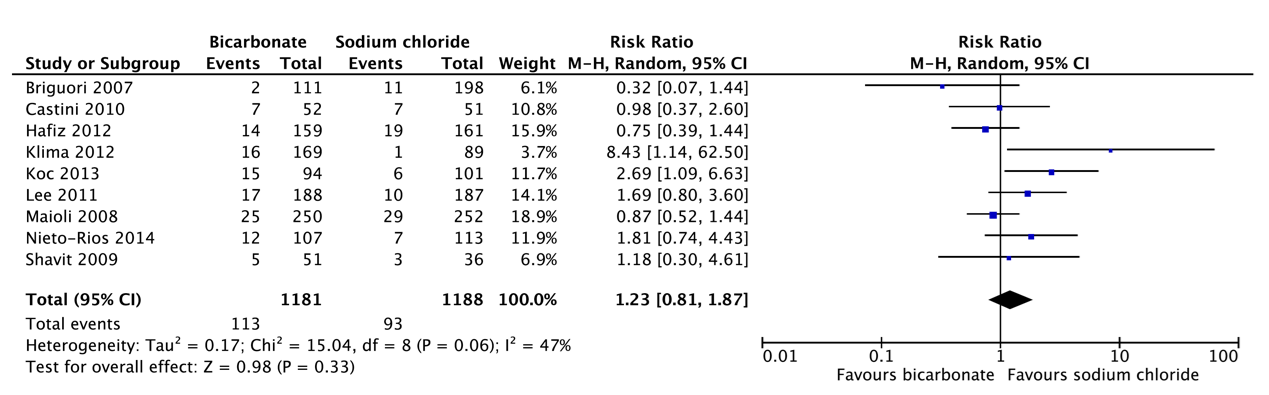

Pooled analysis of older studies in patients with moderate to severe renal failure indicated that short pre- and post-hydration with NaHCO3 1.4% resulted in a slightly, but not significantly higher incidence of PC-AKI after CAG/PCI (9.4%) than long pre- and posthydration with NaCl 0.9% (6.8%).

Additionally, the very large recent RCT of Weisbord 2018 compared the incidence of PC-AKI after CAG between pre- and posthydration with NaHCO3 1.4% or NaCl 0.9% with the same specified minimum required volume and variable, but identical short to long infusion durations in both arms depending on the local policies in the different participating centers. In this RCT the incidence of PC-AKI was comparable after bicarbonate (9.5%) and saline (8.3%). Also, in the sub study of Garcia 2018 of patients who underwent PCI, the incidence of PC-AKI did not differ between bicarbonate (11.3%) and saline (12.0%).

Although the quality of evidence for the effectiveness of short sodium bicarbonate pre- and post-hydration versus short or long sodium chloride pre- and post-hydration for preventing PC-AKI after CAG/PCI and need for renal replacement therapy is very low to low, for practical reasons the short pre- and post-hydration with NaHCO3 seems more attractive. Moreover, despite the similar incidence of heart failure or pulmonary edema in the studies included in this analysis (see table 5) the RCT of Nijssen 2017 (AMACING) indicated that short and long duration of hydration with NaCl 0.9% in relatively low risk procedures in patients with CKD stage 3 resulted in 5.5% major cardiologic adverse events. Outside the research setting, it is likely that especially long duration of NaCl 0.9% hydration will have an inherent risk of fluid overloading in daily practice. Therefore, also in view of the probable risks of hydration with larger volumes of NaCl 0.9%, a short pre- and posthydration with NaHCO3 is to be preferred.

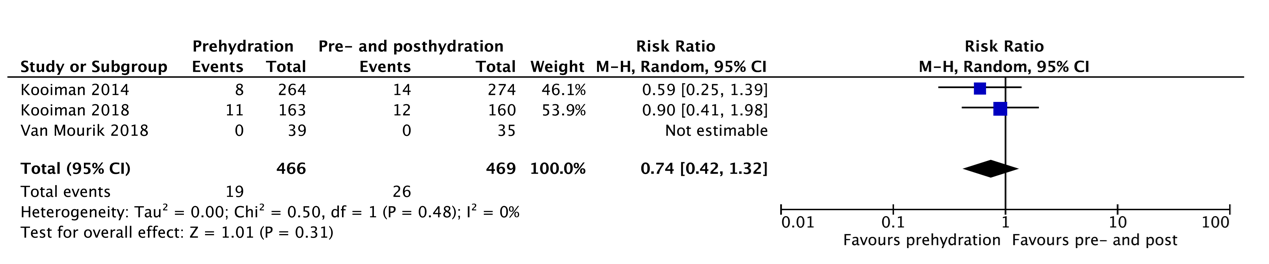

Q3 Pre-hydration only versus pre- and posthydration

Studies comparing prehydration to pre- and posthydration are limited and only focus on prehydration with bicarbonate versus pre- and posthydration with NaCl 0,9% in relatively low-risk populations (>90% eGFR 30-60ml/min/1,73m2) (Kooiman 2014, 2018, van Mourik 2018). Kooiman 2014 and van Mourik 2018 included patients undergoing an elective CT scan, whereas Kooiman 2018 focused on procedures with intra-arterial contrast medium administration, which in ~20% of the patients entailed CAG or PCI with first-pass renal exposure. There was no difference in the incidence of PC-AKI between the prehydration only and the pre- and posthydration group in these studies. A subgroup analysis for first pass versus second-pass renal exposure was not performed. Of note, van Mourik 2018 reported 0% incidence of PC-AKI in both groups. In total, only 78 patients with an eGFR <30ml/min/1,73m2 were included in these studies, and there are no studies focusing specifically on patients with an eGFR <30ml/min/1,73m2. The evidence for prehydration only in high-risk populations is therefore limited. This has, however, been applied broadly in the Netherlands since 2017 without reports of adverse effects, but these results have not been confirmed by other studies.

In contrast, in international guidelines pre-and posthydration is often recommended based on the expert opinion that the amount of urine output is the most important factor regardless how this is achieved. This may especially be valid for intra-arterial CM administration with first pass renal exposure such as coronary angiography or PCI (Solomon, Intervent Cardiol Clin 2023). However, studies investigating PC-AKI in patients undergoing emergent CAG or PCI (such as in STEMI) are inherently prone to bias, since the myocardial infarction is an important independent risk factor for AKI.

Given the fact that Nijssen 2017 showed an elevated risk of cardiac complications following NaCl 0.9% pre- and posthydration, lack of evidence for NaCl 0.9% prehydration alone, reduced patient and healthcare burden of 1 hour prehydration with bicarbonate 1.4% compared to pre- and posthydration with NaCl 0,9%, the Working Group has an expert-based preference for bicarbonate prehydration.

Q4 Oral versus intravenous hydration

The quality of evidence for the effectivity of oral hydration for the prevention of PC-AKI is low. Furthermore, the oral intake of patients could not be quantified and could therefore lead to PC-AKI due to lack of adherence to oral hydration instructions. Therefore, it is the recommendation of the working group that oral hydration should not be used in the prevention of PC-AKI. However, the encouragement of patients using oral fluids unrestrictedly on the day of CM exposure, besides other preventive measures, is advisable.

Q5 Hydration with controlled diuresis

The ratio behind this technique is to increase renal blood flow and urinary output in a controlled environment, based on patient’s parameters, such as central venous pressure, left ventricular end diastolic pressure or urinary output. The amount of additional intravenous fluids and, if necessary, a low dose diuretic, is individualized by the abovementioned parameters. These techniques can only be applied in an in-patient setting as intravenous or intra-arterial catheters are necessary, combined with a urinary catheter for monitoring urinary production. This makes these techniques applicable for a subgroup of patients. The Working Group thinks that controlled diuresis is a promising new invasive strategy to prevent PC-AKI in hospitalized patients undergoing (cardiac) angiography with or without intervention. Which technique is optimal is unknown. Outside of the scope of the current modular revision, a recent meta-analysis of Cossette 2025 demonstrated that tailored hydration based on left-ventricular end-diastolic pressure significantly reduced the incidence of PC-AKI after CAG/PCI as compared to standard hydration (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.41-0.90). Showing comparable efficacy to aforementioned urinary flow rate solutions, with the advantage of a possible reduced barrier to implementation in clinical practice. However, more information and research are needed before reliable conclusions can be drawn regarding the effectiveness and preferred type of controlled diuresis, or its application in an outpatient setting. Therefore, the Working Group recommends that, for now, this technique should be reserved for research setting only.

Quality of evidence

Q1 Hydration versus no hydration

The overall quality of evidence is very low. This means that we are very uncertain about the estimated effect found for the crucial outcome measures.

Downgraded due to (very) serious:

- Risk of bias: methodological limitations, due to loss to follow-up

- Inconsistency: inconsistency of results

- Imprecision: inaccuracy, because the confidence interval exceeds both limits of clinical relevance and because of a very small number of events with a small sample size

Q2 Sodium chloride versus bicarbonate

The overall quality of evidence is very low. This means that we are very uncertain about the estimated effect found for the crucial outcome measures.

Downgraded due to (very) serious:

- Inconsistency: inconsistency of results

- Imprecision: inaccuracy because the confidence interval exceeds the limit/both limits of clinical relevance

Q3 Pre-hydration only versus pre- and posthydration

The overall quality of evidence is very low. This means that we are very uncertain about the estimated effect found for the crucial outcome measures.

Downgraded due to (very) serious:

- Inconsistency: inconsistency of results

- Indirectness: Indirectness of evidence, due to differences in the type of hydration used for pre- and post-hydration

- Imprecision: inaccuracy, due to failure to achieve the optimal sample size or a very small number of events with a small sample size

Q4 Oral versus intravenous hydration

For the comparison of oral versus intravenous hydration in all patients the level of evidence was graded as low due to imprecision and heterogeneity of included studies.

Q5 Hydration with controlled diuresis

For the comparison of controlled diuresis versus IV hydration in all patients the level of evidence was graded as low due to imprecision and heterogeneity of included studies.

Values and preferences of patients (and possibly their relatives/caregivers)

For patients, it is very important that the use of iodine-based contrast agents does not cause PC-AKI or worsen kidney function. To reduce this risk, patients are willing to stay longer in the hospital for hydration. Current medical knowledge suggests that hydration lowers the chance of kidney problems and, as recommended, does not lead to serious side effects. Patients do not want unnecessarily long hydration schedules. It is important for patients to receive a good explanation of the reasons for applying hydration during diagnostics and procedures.

For critically ill patients, receiving treatment quickly and without delays in imaging is a priority. At the same time, preventing kidney problems remains important. These patients therefore want hydration (if it is effective) to be started as soon as possible when iodine-based contrast agents are used.

Cost aspects

The hydration interventions increase the costs of the imaging study slightly. However, these costs are low in comparison to the cost of treatment of clinically relevant CI-AKI or even CA-AKI. Per equal infusion quantity, NaCl 0.9% comes at reduced cost in comparison to NaHCO3 1.4% according to the Zorginstituut Nederland provided data on www.medicijnkosten.nl. A cost-impact analysis has not been part of the current modular revision, and as such differences in cost-effectiveness between NaCl 0.9% versus NaHCO3 1.4% cannot be provided.

Equality ((health) equity/equitable)

The intervention has no expected impact on health equity.

Acceptability

Ethical acceptability

The Working Group expects no ethical concerns with regard to the proposed hydration strategies. Comparable hydration strategies are part of current routine clinical practice, with a low burden as well as a low risk to the patient, whilst providing possible protection against iodine contrast-medium associated risk of kidney injury.

Sustainability

Although any form of hydration strategy will have an environmental impact, environmental sustainability has not been part of the considerations for an optimal hydration strategy.

Feasibility

The feasibility of the provided recommendations is considered high. Hydration strategies consisting of either NaCl 0.9% or NaHCO 1.4% are part of current routine clinical care. Supply chain availability of either products is generally well. And application of hydration strategies is generally well accepted on a national level.

Rationale van aanbeveling-1: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De preventie van PC-AKI kent als randvoorwaarde een adequate hydratie status ongeacht eGFR (zie ook: 2.3 Evaluatie van eGFR). Aanbevelingen met oogpunt op PC-AKI preventie worden gedaan in veronderstelling van een normale hydratie status.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-2: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

In geval van 1) acute, niet uitstelbare diagnostiek, of 2) behandeling, van een vitaal bedreigde patiënt, prevaleert het belang van beeldvorming en eventuele behandeling boven hydratie. Hydratie in het kader van PC-AKI preventie dient derhalve geen reden te zijn voor vertraging in het diagnostisch traject of aanvang van eventuele interventies bij vitaal bedreigde patiënten.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-3: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Geraadpleegde literatuur toont een verhoogde incidentie van PC-AKI binnen patiënten populaties met intra-arteriële toediening van jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel met first-pass renale blootstelling.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-4: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er bestaat onvoldoende evidentie om bij eGFR ≥30 ml/min/1.73m2 hydratie aan te bevelen voor PC-AKI profylaxe na intravasculaire toediening van jodiumhoudend contrast. Daarnaast zijn er aanwijzingen dat gecombineerde pre- en posthydratieschema’s met NaCl 0.9% het risico op hyponatriëmie, aritmie en hartfalen verhogen, waardoor deze schema’s gecontra-indiceerd zijn. Bij gebrek aan bewijs vanuit zowel de literatuur als de praktijk, is het niet doelmatig om mensen en middelen in te zetten om deze extra hydratie behandeling uit te voeren in deze groep patiënten.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling tegen (Niet doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-5: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bij patiënten met een eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2 toont geraadpleegde literatuur een verhoogde incidentie aan PC-AKI met mogelijke relatie tot de toegediende contrastdosis. Vervang jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel of verminder contrastdosis waar mogelijk. Maak tijdens intravasculaire procedures gebruik van aanwezige beschikbare technieken om jodiumhoudend contrastdosis te beperken.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-6: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De geraadpleegde literatuur toont een zeer beperkte evaluatie van het mogelijk gunstige effect van hydratie bij patiënten met een eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2. Voor intra-arteriële toediening van jodiumhoudend contrast met first-pass van de nieren toont de beperkt beschikbare literatuur een mogelijke meerwaarde voor hydratie en in deze setting is aangetoond dat de ernst van de nierfunctiestoornis een belangrijke voorspeller is van het risico op PC-AKI. De beschikbare literatuur maakt aannemelijk dat hydratieschema’s met pre- en korte posthydratie met NaHCO3 1.4% even effectief zijn als schema’s met pre- en korte of lange posthydratie met NaCl 0.9% zodat er een voorkeur is voor hydratieschema’s met NaHCO3 gezien het eerdergenoemde verhoogde risico op hartfalen bij hydratie met NaCl 0.9%. Het effect van alleen prehydratie met NaHCO3 1.4% is helaas niet goed onderzocht in patiënten met eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2.

Voor intraveneuze contrasttoediening en intra-arteriële contrasttoediening met second-pass van de nieren bestaat er op dit moment onvoldoende bewijsvoering van hoge kwaliteit binnen de geraadpleegde literatuur om meerwaarde van hydratie te bevestigen noch te ontkrachten.

Gezien deze bovenstaande overwegingen is het cluster van mening om bij alle patiënten met een eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2 enige vorm van hydratie ter PC-AKI preventie toe te passen.

Ondanks zeer beperkt wetenschappelijk bewijs wordt door een groot deel van de Nederlandse centra een voorkeur gegeven aan een hydratieschema met alleen prehydratie met NaHCO3 1.4%, doch zonder prospectieve evaluatie op de incidentie van PC-AKI en eventuele vervroeging van indicatie tot start van nierfunctie-vervangende therapie.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen).

Zwakke aanbeveling voor (Doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-7: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Binnen de geraadpleegde literatuur is er géén bewijs dat alleen prehydratie met NaHCO3 1.4% even effectief als NaCl 0.9% hydratie voor preventie van PC-AKI bij intra-arteriële onderzoeken met first-pass van jodiumhoudend contrast. Deze wetenschappelijke basis ontbreekt ook volledig voor prehydratie alleen met NaCl 0.9%. Pre- en korte posthydratie met NaHCO3 1.4% wordt op basis van de literatuur bij deze patiënten als equivalent beschouwd aan korte en lange hydratieschema’s met NaCl 0.9%.

Toevoegen van korte 4-6 uur posthydratie met NaHCO3 1.4% heeft (of naar verwachting) minimale logistieke of financiële implicaties na interventies met arteriële contrasttoediening met first-pass effect. Gezien deze overwegingen is het cluster van mening dat posthydratie bij deze patiëntengroep vooralsnog laagdrempelig toegepast dient te worden.

Gelet op logistieke overwegingen, kostenoverwegingen en verhoogde risico op hartfalen bij NaCl 0.9% schema’s wordt bij voorkeur een hydratieschema met prehydratie en korte posthydratie met NaHCO3 1.4% aanbevolen.

Eindoordeel:

Zwakke aanbeveling voor (Doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-8: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Patiënten met chronische nierschade G5 (eGFR < 15 ml/min/1.73m2) en patiënten met hartfalen kennen een verhoogd risico op zowel PC-AKI en hydratie gerelateerde complicaties. Individualiseer hydratie waar nodig. Consulteer laagdrempelig relevante specialismen, denk hierbij aan respectievelijk nefrologie en cardiologie. Bij reeds dialyse-afhankelijkheid toont beschikbare literatuur geen meerwaarde voor hydratie of aanpassing van het dialyseschema.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling voor (Doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-9: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bij reeds dialyse-afhankelijkheid toont beschikbare literatuur geen meerwaarde voor hydratie of aanpassing van het dialyseschema.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling tegen (Niet Doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-10: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling tegen (Niet doen).

Rationale van aanbeveling-11: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er bestaat onvoldoende evidentie om alleen orale hydratie aan te bevelen bij patiënten met een verhoogd risico op PC-AKI. Bij gebrek aan bewijs vanuit zowel de literatuur als de praktijk, is het niet doelmatig om mensen en middelen in te zetten om deze extra handeling uit te voeren.

Eindoordeel:

Sterke aanbeveling tegen (Niet doen).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Current protocols using pre/post hydration with Bicarbonate 1.4% IV or NaCl 0.9% IV are functioning well in practice. However, it is necessary to compare the recommended hydration protocols for patients with impaired renal function in the guideline to newly published approaches and evaluate if the recommendations have to be updated. In addition, an investigation of the possibility to adapt protocols for specific situations in interventional radiology or cardiology, and tailor prehydration dependent on the route of CM administration (intravenous or intra-arterial with second pass renal exposure vs. intra-arterial with first pass renal exposure) is required.

In the current module, the following possible strategies are compared:

- Hydration versus no hydration

- Sodium chloride (NaCl) versus sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) hydration

- Pre-hydration only versus pre- and posthydration

- Oral versus intravenous hydration

- Hydration with controlled diuresis

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Table 3. Summary of Findings

Population: Patients with impaired renal function (chronic kidney disease, chronic renal failure, CKD stage 3 or higher, eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2) undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media.

Intervention: Hydration

Comparator: No hydration

Click here to see this table in a document

|

Outcome Timeframe |

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Conclusions |

|

|

No hydration |

Hydration |

||||

|

Post-contrast acute kidney injury (critical) |

Based on data from 4 studies |

Kooiman (2014) reported a risk difference of -0.02 (95%CI -0.11 to 0.07). Nijssen (2017) reported a risk difference of 0.00 (95%CI -0.02 to 0.03). Timal (2020) reported a risk difference of -0.01 (95%CI -0.04 to 0.01). Chen (2008) reported a risk difference of -0.20 (95%CI -0.33 to -0.08) for patients with moderate to severely impaired renal function and -0.00 (95%CI -0.04 to 0.04) for normal or mildly impaired renal function. |

Very low Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision1 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on post-contrast acute kidney injury when compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Start renal replacement therapy (RRT) |

|||||

|

Start renal replacement therapy (critical) |

Based on data from 3 studies |

Kooiman (2014), Nijssen (2017) and Timal (2020) reported that none of the patients who either received hydration or no hydration had to start RRT. |

Very low Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision2 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on the start of renal replacement therapy when compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Start renal replacement therapy at 1 year follow-up (critical) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Nijssen (2018) reported a risk difference of 0.00 (95%CI -0.01 to 0.01). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision3 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on the start of renal replacement therapy at 1 year follow-up when compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Acute renal failure (important) |

- |

- |

No GRADE (no evidence was found) |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of hydration on acute renal failure when compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function (chronic kidney disease, chronic renal failure, CKD stage 3 or higher, eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2) undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Irreversible loss of kidney function |

|||||

|

Irreversible loss in kidney function – persisting decline in renal function at 2 months follow-up (important) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Timal (2020) reported a risk difference of -0.43 (95%CI -0.86 to 0.00). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision4 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on irreversible loss in kidney function (defined as persisting decline in renal function at 2 months follow-up) when compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media.

|

|

|

Irreversible loss in kidney function – >10 eGFR decline (important) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Nijssen (2017) reported a risk difference of -0.02 (95%CI -0.05 to 0.02). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision4 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on irreversible loss in kidney function (defined as >10 eGFR decline) as compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Irreversible loss in kidney function – >10 eGFR decline at 1 year follow-up (important) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Nijssen (2018) reported a risk difference of -0.00 (95%CI -0.05 to 0.05). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision4 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on irreversible loss in kidney function (defined as >10 eGFR decline) at 1 year follow-up when compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Irreversible loss in kidney function – decline to <30 mL per min/1.73m2 (important) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Nijssen (2017) reported a risk difference of 0.00 (95%CI -0.02 to 0.03). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision4 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on irreversible loss in kidney function (defined as decline to <30 mL per min/1.73m2) when compared to no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Irreversible loss in kidney function – decline to <30 mL per min/1.73m2 at 1 year follow-up (important) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Nijssen (2018) reported a risk difference of 0.00 (95%CI -0.02 to 0.02). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious risk of bias, due to very serious imprecision4 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on irreversible loss in kidney function (defined as decline to <30 mL per min/1.73m2) at 1 year follow-up when compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Adverse events (important) |

Based on data from 2 studies |

Nijssen (2018) reported a risk difference of 0.04 (95%CI 0.02 to 0.06). Timal (2020) reported that none of the patients who either received hydration or no hydration had adverse events. |

Very low GRADE Due to serious risk of bias, due to serious inconsistency, due to serious imprecision5 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hydration on adverse events when compared with no hydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

1. Inconsistency: serious. Due to conflicting results and differences in the type of hydration.

Imprecision: very serious. Due to overlap of the lower and upper limit of the 95% confidence interval with the minimal clinically important difference.

2. Inconsistency: serious. Due to differences in the type of hydration.

Imprecision: very serious. Due to no events occurred and the optimal information size was not achieved.

3. Risk of bias: serious. Due to lack of blinding.

Imprecision: very serious. Due to overlap of the lower and upper limit of the 95% confidence interval with the minimal clinically important difference.

4. Risk of bias: serious. Due to loss to follow-up

Imprecision: very serious. Due to overlap of the lower and upper limit of the 95% confidence interval with the minimal clinically important difference.

5. Risk of bias: serious. Due to lack of blinding.

Inconsistency: serious. Due to conflicting results and differences in the type of hydration.

Imprecision: serious. Due to the low number of events.

Table 6. Summary of Findings

Population: Patients with impaired renal function (chronic kidney disease, chronic renal failure, CKD stage 3 or higher, eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2) undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media.

Intervention: NaCl

Comparator: NaHCO3

Click here to see this table in a document

|

Outcome Timeframe |

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Conclusions |

|

|

NaCl |

NaHCO3 |

||||

|

Post-contrast acute kidney injury |

|||||

|

PC-AKI: Short schedule NaHCO3 vs. short schedule NaCl |

Relative risk: 0.89 (CI 95% 0.57 – 1.39) Based on data from 2192 participants in 11 studies |

115 per 1000 |

102 per 1000 |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision1 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of NaCl on post-contrast acute kidney injury when compared with NaHCO3 in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

Difference: 13 fewer per 1000 (CI 95% 49 fewer – 45 more) |

|||||

|

PC-AKI: Short schedule NaHCO3 vs. long schedule NaCl |

Relative risk: 1.23 (CI 95% 0.81 – 1.87) Based on data from 2369 participants in 9 studies |

78 per 1000 |

96 per 1000 |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision1 |

|

|

Difference: 18 more per 1000 (CI 95% 15 fewer – 68 more) |

|||||

|

PC-AKI: All other hydration schedules comparing bicarbonate plus sodium chloride or bicarbonate only to either sodium chloride or bicarbonate only |

Based on data from 6 studies |

Studies identified before 2017 varied in their estimates (see results above). Weisbord (2018) reported a risk difference of -0.01 (95%CI -0.03 to 0.00). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision1 |

||

|

PC-AKI: NaHCO3 (ultrashort schedule) precontrast versus pre- and post-CM hydration with NaCl

|

Based on data from 1 study |

Kooiman (2014) reported a risk difference of -0.02 (95%CI -0.05 to 0.01) |

Very low GRADE Due to serious indirectness, due to very serious imprecision2 |

||

|

Start renal replacement therapy (RRT) |

|||||

|

Start RRT: Short schedule NaHCO3 vs. short schedule NaCl |

Based on data from 9 studies |

Studies identified before 2017 varied in their estimates (see table 5) Boccalandro (2020) reported a risk difference of -0.01 (95%CI -0.05 to 0.03)

|

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision3 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of NaCl on the start of renal replacement therapy when compared with NaHCO3 in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Start RRT: Short schedule NaHCO3 vs. long schedule NaCl |

Based on data from 7 studies |

Studies identified before 2017 varied in their estimates (see table 5) |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision3 |

||

|

Start RRT: All other hydration schedules comparing bicarbonate plus sodium chloride or bicarbonate only to either sodium chloride or bicarbonate only |

Based on data from 5 studies |

Studies identified before 2017 varied in their estimates (see table 5) Weisbord (2018) reported a risk difference of -0.00 |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision3 |

||

|

Start RRT: NaHCO3 (ultrashort schedule) precontrast versus pre- and post-CM hydration with NaCl |

Based on data from 1 study |

Kooiman (2014) reported that none of the patients who either received prehydration or pre-and posthydration had to start renal replacement therapy. |

Very low GRADE Due to serious indirectness, due to very serious imprecision2 |

||

|

Start renal replacement therapy – 1 year (important) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Boccalandro (2020) reported a risk difference of -0.02 (95%CI -0.04 to 0.01) |

Very low GRADE Due to very serious imprecision4 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of NaCl on the start of renal replacement therapy at 1 year follow-up when compared with NaHCO3 in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Start renal replacement therapy – 5 year (important) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Boccalandro (2020) reported a risk difference of 0.02 (-0.05 to 0.08) |

Very low GRADE Due to very serious imprecision4 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of NaCl on the start of renal replacement therapy at 5 year follow-up when compared with NaHCO3 in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Acute renal failure (important) |

- |

- |

No GRADE (no evidence was found) |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of NaCl on acute renal failure when compared with NaHCO3 in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Irreversible loss of kidney function (important) |

Based on data from 1 study |

Weisbord (2018) reported a risk difference of 0.00 (95%CI -0.00 to 0.01) |

Very low GRADE Due to very serious imprecision4 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of NaCl on irreversible loss of kidney function when compared with NaHCO3 in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Adverse events |

|||||

|

Adverse events: Short schedule NaHCO3 vs. short schedule NaCl |

Based on data from 5 studies |

Studies identified before 2017 varied in their estimates (see table 5). Boccalandro (2020) reported a risk difference of 0.01 (95%CI -0.06 to 0.08). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision5 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of NaCl on adverse events when compared with NaHCO3 in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media |

|

|

Adverse events: Short schedule NaHCO3 vs. long schedule NaCl |

Based on data from 4 studies |

Studies identified before 2017 varied in their estimates (see table 5). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision5 |

||

|

Adverse events: All other hydration schedules comparing bicarbonate plus sodium chloride or bicarbonate only to either sodium chloride or bicarbonate only |

Based on data from 4 studies |

Studies identified before 2017 varied in their estimates (see table 5). Weisbord (2018) reported a risk difference of -0.01 |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision5 |

||

|

Adverse events: NaHCO3 (ultrashort schedule) precontrast versus pre- and post-CM hydration with NaCl |

Based on data from 1 study |

Kooiman (2014) reported a risk difference of -0.03 (95%CI -0.10 to 0.05). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious inconsistency, due to very serious imprecision6 |

||

1. Inconsistency: serious. Due to conflicting results and heterogeneity

Imprecision: very serious. Due to overlap of the upper and lower limit of the 95% confidence interval with the minimal clinically important difference

2. Indirectness: serious. Due to differences in the hydration type (pre- versus pre- and posthydration)

Imprecision: very serious. Due to overlap of the upper and lower limit of the 95% confidence interval with the minimal clinically important difference

3. Inconsistency: serious. Due to conflicting results and heterogeneity

Imprecision: very serious. Due to the optimal information size which was not achieved and the low number of events

4. Imprecision: very serious. Due to overlap of the upper and lower limit of the 95% confidence interval with the minimal clinically important difference and the optimal information size was not achieved.

5. Inconsistency: serious. Due to heterogeneity between the studies

Imprecision: very serious. Due to the optimal information size which was not achieved and the low number of events

6. Inconsistency: serious. Due to differences in the hydration type (pre- versus pre- and posthydration)

Imprecision: very serious. Due to the optimal information size which was not achieved and the low number of events

Table 8. Summary of Findings

Population: Patients with impaired renal function (chronic kidney disease, chronic renal failure, CKD stage 3 or higher, eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2) undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media.

Intervention: Prehydration

Comparator: Pre- and posthydration

Click here to see this table in a document

|

Outcome Timeframe |

Study results and measurements |

Absolute effect estimates |

Certainty of the evidence (Quality of evidence) |

Conclusions |

|

|

Pre- and posthydration |

Prehydration |

||||

|

Post-contrast acute kidney injury (critical) |

Relative risk: 0.74 (CI 95% 0.42 – 1.32) Based on data from 935 participants in 3 studies |

75 per 1000 |

56 per 1000 |

Very low GRADE Due to serious indirectness, due to very serious imprecision1 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prehydration on post-contrast acute kidney injury when compared with pre- and posthydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

Difference: 19 fewer per 1000 (CI 95% 43 fewer – 24 more) |

|||||

|

Start renal replacement therapy (critical) |

Based on data from 3 studies |

Kooiman (2014), Kooiman (2018) and Van Mourik (2018) reported that none of the patients who either received prehydration or pre-and posthydration had to start renal replacement therapy. |

Very low GRADE Due to serious indirectness, due to very serious imprecision2 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prehydration on the start of dialysis when compared with pre- and posthydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Acute renal failure (important) |

- |

- |

No GRADE (no evidence was found) |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of prehydration on acute renal failure when compared with pre- and posthydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Irreversible loss of kidney function (important) |

- |

- |

No GRADE (no evidence was found) |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of prehydration on irreversible loss of kidney function when compared with pre- and posthydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

|

Adverse events (important) |

Based on data from 2 studies |

Kooiman (2014) reported a risk difference of -0.02 (95%CI -0.04 to -0.00). Van Mourik (2018) reported a risk difference of -0.03 (95%CI -0.10 to 0.05). |

Very low GRADE Due to serious indirectness, due to very serious imprecision1 |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prehydration on adverse events when compared with pre- and posthydration in patients with impaired renal function undergoing radiological or cardiological examinations with iodine-containing contrast media. |

|

1. Indirectness: serious. Due to differences in the hydration type used for pre- and posthydration

Imprecision: very serious. Due to overlap of the upper and lower limit of the 95% confidence interval with the minimal clinically important difference

2. Indirectness: serious. Due to differences in the hydration type used for pre- and posthydration

Imprecision: very serious. Due to no events occurred and the optimal information size which was not achieved

Samenvatting literatuur

Question 1-3 update 2025.

Question 1: hydration versus no hydration

Description of studies

A total of four studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Three RCTs were found in the search of 2017 and two studies were added in 2025. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in table 2. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables (under the tab ‘Evidence tabellen’).

Chen (2008) performed a prospective, randomized, parallel-group, open label study in three centers in China to study the effect of pre- and posthydration with 0.45% saline on major clinical endpoints after 6 months and the incidence of PC-AKI after elective PCI. They studied all consecutive patients with myocardial ischemia scheduled for elective PCI, divided into a group of 660 patients (mean age 60±8 years) with normal or mildly impaired renal function (creatinine <133, mean 114±26 umol/l and eGFR 53±16 ml/min/1.73m2) and a group of 276 patients (mean age 63±11 years) with moderate to severely impaired renal function (creatinine >133; mean creatinine 220±9 umol/l and eGFR 28±2 ml/min/1.73m2). Patients were excluded if (1) the coronary anatomy not suitable for PCI; (2) emergency coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) being required; (3) patients in chronic peritoneal or hemodialytic treatment; (4) acute myocardial infarction (AMI) at admission. In both groups, hydration was given with hypotonic NaCl 0.45% at a rate of 1 ml/kg/min for 12 hours before and 6 hours after PCI. In patients with reduced left ventricular function (ejection fraction <40%), infusion rate was reduced to 0.8 ml/kg/min. Only in the group with moderate to severely impaired renal function, all patients received a loading dose of 1200 mg N-Acetyl Cysteine 12 hours before PCI. Primary endpoint consisted of clinical driven revascularization (either PCI or CABG), death from all causes and requiring emergency renal-replacement therapy during the 6 months follow-up. They further studied adverse events such as acute pulmonary edema during 6 months follow-up and the incidence of PC-AKI defined as an absolute increase of serum creatinine >44 umol/L at 48 hours after PCI in the two groups.

Kooiman (2014) described 138 patients with eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 undergoing chest CT for suspected pulmonary embolism. Sixty-seven patients received no hydration, and the remaining 71 patients received 250ml NaHCO3 1.4% within one hour prior to CT.

Nijssen (2017) performed a prospective, randomised, phase 3, single centre, parallel-group, open-label, non-inferiority trial (AMACING) in the Netherlands to determine whether giving no prophylaxis is non-inferior to standard care prophylactic hydration. Patients aged 18 years and older (mean age 72±9 years) who received an elective procedure requiring intravascular iodinated contrast material with known eGFR lower than 60 mL per min/1.73m2 were eligible. Inclusion criteria were patients with an eGFR between 45 and 59 mL per min/1.73 m² combined with either diabetes, or at least two predefined risk factors (age >75 years; anaemia defined as haematocrit values <0.39 L/L for men, and <0.36 L/L for women; cardiovascular disease; non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or diuretic nephrotoxic medication); or eGFR between 30 and 45 mL per min/1.73 m²; or multiple myeloma or lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma with small chain proteinuria. In total, 328 patients received hydration with 0.9% NaCl (52% short protocol and 48% long protocol of respectively 4 hours and 12 hours before and after contrast) and 332 patients received no hydration. Groups were comparable at baseline. Mean eGFR was 47±8 ml/min/1.73m2 and 35% had an eGFR 30-45 ml/min/1.73m2. 48% of the patients received intra-arterial contrast (of these 60% coronary catheterisations, 30% percutaneous coronary interventions and 10% other). Serum creatinine was measured immediately before, at 2-6 days, and at 26-35 days after contrast administration. PC-AKI was defined as an increase of serum creatinine >25% or >44 µmol/L 2-6 days after contrast (instead of the usual 48-72 hours after contrast). Outcomes of interest were incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy, renal failure, dialysis and renal function decline.

Nijssen (2018) presented the 1-year follow-up results of the study of Nijssen (2017). For inclusion criteria see above. Outcomes of interest were renal function decline and dialysis.

Timal (2020) performed a multicentre, noninferiority, randomized clinical trial (KOMPAS) in the Netherlands to determine the safety of omitting prophylactic prehydration prior to iodine-based contrast media administration in the setting of elective contrast-enhanced CT. Inclusion criteria were patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 to 44 mL/min/1.73 m2 (CKD stage 3B) or with an eGFR of 45 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 (CKD stage 3A) in the presence of diabetes or at least 2 of the following risk factors: peripheral artery disease, congestive heart failure, age older than 75 years, anemia, contrast medium volume greater than 150 mL, or use of nephrotoxic medication (e.g., diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cyclosporin, tacrolimus, antiviral medication, amphotericin B, aminoglycosides, cisplatin, vancomycin). In total, 261 patients received prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate administered in a 1-hour infusion and 262 patients received no prehydration. Groups were comparable at baseline with amongst others 40% diabetes and approximately 15% heart failure in both groups. About half of the patients had an eGFR 30-45 ml/min/1.73m2. Approximately 50% of the patients were using diuretics, which could be interrupted before contrast administration. Serum creatinine was measured before hydration and contrast, at 2-5 days, and at 7-14 days after contrast administration in all patients and was repeated after 2 months in the patients who had developed PC-AKI. PC-AKI was defined as an increase of serum creatinine >25% or >44 µmol/L 2-5 days after contrast. Outcomes of interest were incidence of postcontrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI), irreversible loss of kidney function and dialysis.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies

|

Study |

Participants |

Comparison |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures |

Comments |

Risk of bias (per outcome measure)* |

|

Individual studies |

||||||

|

Chen, 2008 |

N at baseline:

Normal serum creatinine group Intervention: 330 Control: 330

Abnormal serum creatinine group Intervention: 188 Control: 188

Baseline characteristics not reported |

Intervention: Hydration (treated by 0.45% saline given intravenously at a rate of 1 ml/kg/h starting from 12 h before scheduled time for coronary angiogram) Control: nonhydration

All patients in abnormal group took twice orally loading dose of 1200 mg NAC at 12 h before scheduled time for coronary angiogram and immediately after procedure.

|

6 months |

CIN |

Source of funding and conflicts of interest not reported. |

High (all outcomes) |

|

Kooiman, 2014 |

N at baseline Intervention: 71 Control: 67

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 71 years (SD=13) Control: 70 years (SD=12)

Sex (male) Intervention: 34 (48%) Control: 35 (52%)

|

Intervention: 250 mL iv 1.4% sodium bicarbonate 1 hour before CTPA Control: Withholding hydration prior to CTPA |

96 hours |

CI-AKI, need for dialysis |

Non-commercial source of funding. |

LOW (CI-AKI, dialysis)** |

|

Nijssen, 2017 |

N at baseline Intervention: 328 Control: 332

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 71.9 years (SD=9.3) Control: 72.6 years (SD=9.3)

Sex (male) Intervention: 194 (59%) Control: 213 (64%)

|

Intervention: intravenous 0.9% NaCl Control: no prophylaxis |

Up to 35 days |

Incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy, renal failure, renal function decline, dialysis, adverse events |

The funder was not involved in trial design, patient recruitment, data collection, analysis, interpretation or presentation, writing or editing. The authors declare no competing interests. |

LOW (dialysis, adverse events)

Some concerns (incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy, renal failure, renal function decline) |

|

Nijssen, 2018 (follow-up of Nijssen, 2017) |

N at baseline Intervention: 328 Control: 332

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 71.9 years (SD=9.3) Control: 72.6 years (SD=9.3)

Sex (male) Intervention: 194 (59%) Control: 213 (64%)

|

Intervention: intravenous 0.9% NaCl Control: no prophylaxis |

1 year |

Renal function decline, dialysis |

Funding by Stichting de Weijerhorst. The authors declare no competing interests.

|

Some concerns (end-stage renal failure, decrease in residual kidney function)

Low (dialysis) |

|

Timal, 2020 |

N at baseline Intervention: 261 Control: 262

Age (median, IQR) Intervention: 73 years (67-78) Control: 74 years (67-80)

Sex (male) Intervention: 166 (63.6%) Control: 213 (64.9%)

|

Intervention: prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate administered in a 1-hour infusion Control: no prehydration

|

Up to 1 year |

Incidence of PC-AKI, decrease in residual kidney function, and dialysis |

Not reported |

Low (incidence of PC-AKI, end-stage renal failure, dialysis, adverse events)

Some concerns (decrease in residual kidney function) |

*For further details, see risk of bias table in the appendix

** The risk of bias was based on the risk of bias assessment performed in the guideline of 2017

Results

1. Post-contrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI) (critical)

Four studies reported the incidence of PC-AKI for the comparison between hydration and no hydration (Chen, 2008; Kooiman, 2014; Nijssen, 2017; Timal, 2020). Because of heterogeneity between these studies in terms of type of hydration, the results were not pooled.

Chen (2008) reported that 22 of the 330 patients (6.67%) in the group with normal or mildly impaired renal function (eGFR 53±16 ml/min/1.73m2) who received hydration with 0.45% NaCl had PC-AKI as compared to 23 of the 330 (6.97%) who received no hydration (RR=0.89, 95%CI 0.58 to 1.35). In the group with moderate to severely impaired renal function (eGFR 28±2 ml/min/1.73m2), 40 of the 188 patients (21.28%) who received hydration had PC-AKI as compared to 64 of the 188 patients (34.04%) who received no hydration (RR=0.63, 95%CI 0.46 to 0.84).

Kooiman (2014) reported that 5 of the 70 patients (7.1%) who received 1-hour pre-hydration with 250ml NaHCO3 had PC-AKI as compared to 6 of the 65 patients (9.2%) in the group withholding hydration (RR=0.77, 95%CI 0.25 to 2.41).

Nijssen (2017) reported that 8 of the 296 patients (2.7%) who received hydration had contrast-induced nephropathy as compared to 8 of the 307 patients (2.6%) who did not receive hydration (RR=1.04, 95%CI 0.39 to 2.73).

Timal (2020) reported that 4 of the 261 patients (1.5%) who received hydration had PC-AKI 2 to 5 days after contrast enhanced CT as compared to 7 of the 262 patients (2.7%) who did not receive hydration (RR=0.57, 95%CI 0.17 to 1.94).

2. Start renal replacement therapy (RRT) (critical)

Three studies reported the start of renal replacement therapy for the comparison between hydration and no hydration (Nijssen, 2014; Nijssen, 2017; Timal, 2020). Because of heterogeneity between these studies in terms of type of hydration and since no events occurred, the results were not pooled.

Nijssen (2014) reported that none of the PC-AKI patients who either received hydration or no hydration developed need for dialysis.

Nijssen (2017) reported that no patients who received either hydration or did not receive hydration required dialysis within 35 days post-contrast.

Timal (2020) reported that during the at least one-year follow-up, no patients who received either hydration or did not receive hydration required dialysis.

At 1-year follow-up

Nijssen (2018), the 1-year follow-up study of Nijssen (2017), reported that within 365 days, 2 of the 328 patients (0.6%) who received hydration required dialysis as compared to 2 of the 332 patients (0.6%) who did not receive contrast (RR=1.01, 95%CI 0.14 to 7.14).

3. Acute renal failure (important)

Not reported.

4. Irreversible loss of kidney function (important)

Timal (2020) reported that after 2 months of follow-up, 3 of the 7 patients (43%) with PC-AKI who did not receive hydration had a persisting decline of renal function (mean decrease in eGFR, 3 mL/min/1.73 m2) while this did not occur in the 4 patients who developed PC-AKI despite hydration (RR=0.23, 95%CI 0.01 to 3.56).

4.1. >10 ml/min/1.73m2 eGFR decline

Nijssen (2017) reported that 7 of the 260 patients (2.7%) who received hydration had >10 ml/min/1.73m2 renal function decline from baseline as compared to 11 of the 260 patients (4.2%) who did not receive hydration (RR=0.64, 95%CI 0.25 to 1.62). This difference is clinically relevant favoring hydration.

1-year follow-up

Nijssen (2018), the 1-year follow-up study of Nijssen (2017), reported that 28 of the 297 patients (9.4%) who received hydration had >10 ml/min/1.73m2 renal function decline from baseline as compared to 28 of the 292 patients (9.6%) who did not receive hydration (RR=0.98, 95%CI 0.60 to 1.62). This difference is not clinically relevant.

4.2. Decline to <30 mL per min/1.73m2

Nijssen (2017) reported that 7 of the 260 patients (2.7%) who received hydration had a renal function decline to eGFR < 30 mL per min/1.73m2 as compared to 6 of the 260 patients (2.3%) who did not receive hydration (RR=1.17, 95%CI 0.40 to 3.42).

1-year follow-up

Nijssen (2018), the 1-year follow-up study of Nijssen (2017), reported that 9 of the 297 patients (3.0%) who received hydration had a renal function decline to eGFR

< 30 mL per min/1.73m2 as compared to 8 of the 292 patients (2.7%) who did not receive hydration (RR=1.11, 95%CI 0.43 to 2.83).

5. Adverse events (important)

Nijssen (2017) reported that 13 of the 328 patients (4.0%) who received short or long hydration with NaCl 0.9% had symptomatic heart failure, while this did not occur in patients who did not receive hydration (RR=27.33, 95%CI 1.63 to 457.82).

Timal (2020) reported that no patients who received either hydration (n=261) or did not receive hydration (n=262) developed heart failure.

Q2: NaCl versus NaHCO3

Description of studies

A total of 27 studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Twenty-four RCTs were found and described in the search of 2017. This was updated in 2025 with the description of three additional studies. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in table 4. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables (under the tab ‘Evidence tabellen’).

Description of three studies from update 2025

Boccalandro (2020) performed a prospective, single-centre, randomized, double-blinded

study in the USA to compare the effect of a short schedule of sodium bicarbonate with NaCl on long-term outcomes of clinically stable patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) undergoing non-emergent coronary angiography and when indicated percutaneous coronary intervention. It included elective cases and urgent cases defined as requiring angiography within 24-hours from hospital admission with CKD Stage III-IV (eGFR 15-59 ml/min/1.73 m2). In total, 190 patients received NaCl (154mEq/l NaCl with 5% dextrose solution for 1 h before and during the angiographic procedure at a rate of 3ml/kg/h followed by 1 ml kg/h for 6 h post-procedure ) and 192 patients received sodium bicarbonate (150 mEq/l SB with 5% dextrose solution at 3 ml/kg/h for 1 h before and during the angiographic procedure, followed by 1 ml/kg/h for 6 h post-procedure). Diuretics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were discontinued 24-hours prior to the procedure and at least for 72-hours after the procedure. Groups were comparable at baseline. Gender was equally distributed with 53% and 51% male in the sodium bicarbonate group and sodium chloride group, respectively. Within the sodium bicarbonate group, 60% were of Caucasian descent, 30% of Hispanic descent and 10% of African American descent. These figures were comparable within the sodium chloride group, being 62%, 29% and 8%, respectively. Baseline eGFR was 40±18 ml/min/1.73m2 and 63% had diabetes mellitus. Outcomes of interest were iodine containing contrast associated acute kidney injury (CA-AKI) defined by an absolute increase in creatinine >0.5 mg/dl (>44 µmol/l) or relative increase >25% within 48 hours and need to start renal replacement therapy after 1 and 5 years based on telephone interview of randomized patients.

Weisbord (2018) performed a double-blind, placebo- and comparator-controlled, multicentre, international randomized clinical trial with a 2 by 2 factorial design comparing intravenous sodium bicarbonate with intravenous sodium chloride and oral acetylcysteine with oral placebo for the prevention of major adverse outcomes and acute kidney injury in a large population of high-risk patients undergoing coronary or noncoronary angiography. Patients were enrolled at 53 medical centres in the United States of America (35 Veteran Affairs sites), 13 sites in Australia, 3 sites in Malaysia, and 2 sites in New Zealand. For the purpose of this guideline, only the comparison between sodium chloride and sodium bicarbonate were analysed. Patients (93.6% male; 80.9% with diabetes) undergoing non-emergency coronary or non-coronary angiography who had a baseline eGFR of 15 to 44.9 ml/min/1.73 m2 or both an eGFR of 45 to 59.9 ml/min/1.73 m2 and diabetes were included. In total, 2482 patients received isotonic 0.9% sodium chloride (154 mmol/l) and 2511 patients received isotonic 1.26% sodium bicarbonate (150 mmol/l). The infusion protocol allowed different volume and duration of infusion in the protocols of the participating centers with a specified minimum required volume and duration of administration of ≥3 ml/kg over 1-12 hours (1-3 ml/kg/hour) before angiographic procedure, 1–1.5 ml/kg/hour during angiography, and ≥6 ml/kg over 4-12 hours (1–1.5 ml/kg/hour) after the procedure. Blood samples were collected before, 3-5 days and 90-104 days after angiography and serum creatinine levels in these samples were measured simultaneously for each patient in the trial laboratory. Groups were comparable at baseline. The outcomes of interest were CA-AKI (increase of serum creatinine ≥25% and/or ≥0.5 mg/dl (44 µmol/l) at 96 hours) and need for dialysis or persistent decline in kidney function (increase of creatinine >50% from baseline) at 90 days. The trial was stopped prematurely because of futility after the preplanned interim analysis after inclusion of 4993 patients.

Garcia (2018) performed a subgroup analysis of the study of Weisbord (2018) to assess the effect of intravenous sodium bicarbonate and intravenous sodium chloride in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) during the angiographic examination. Patients were excluded in the case of emergency angiography (e.g., those with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction); unstable baseline levels of serum creatinine (≥ 25% variation within 3 days prior to angiograph); decompensated heart failure requiring IV inotropic support, ultrafiltration, or intra-aortic balloon pump; recent exposure to contrast media. In total, 593 patients received sodium chloride, and 568 patients received sodium bicarbonate. Groups were comparable at baseline. Baseline median eGFR was 50.7 ml/min/1.73m2 (IQR 41.7 – 60.1). Patients undergoing PCI received a median contrast volume of 160 ml (IQR 115 – 220) versus non-PCI median 75 ml (IQR 50 – 105) in the overall cohort of Weisbord 2018. The outcome of interest was CA-AKI.

Description of all current and previous studies

Depending on the design, the RCTs comparing sodium to bicarbonate hydration were categorized into several groups:

- Short schedule NaHCO3 vs. short schedule NaCl in patients with impaired kidney function undergoing coronary angiography (CAG) and/or PCI. A total of 11 RCTs (Adolph, 2008; Boccalandro, 2020; Boucek, 2013; Brar, 2008; Gomes, 2012; Masuda, 2007; Merten, 2004; Ozcan, 2007; Ratcliffe, 2009; Recio-Mayoral, 2007; Solomon 2015) with 2,192 patients were identified, that compared bicarbonate and sodium chloride hydration in a similar hydration scheme for coronary angiography. All the studies were performed in patients with impaired kidney function;

- Short schedule NaHCO3 vs. long schedule NaCl (1ml/kg/h for 12h pre- and 12h post-CM administration) in patients with impaired kidney function undergoing CAG and/or PCI. A total of 9 RCTs (Briguori, 2007; Castini, 2010; Hafiz, 2012; Klima, 2012; Koc, 2013; Lee, 2011; Maioli, 2008; Nieto-Rios, 2014; Shavit, 2009) with 3,026 patients were identified that compared bicarbonate hydration to sodium chloride pre- and posthydration (1ml/kg, 12hour pre- and post) for coronary angiography;

- All other hydration schedules comparing bicarbonate plus sodium chloride or bicarbonate only to either sodium chloride or bicarbonate only. Four RCTs (Chong, 2015; Motohiro, 2011; Tamuro, 2009; Ueda, 2011) with 358 patients compared bicarbonate to sodium chloride hydration with divergent hydration schemes for coronary angiography, like adding a bolus NaHCO3 to sodium chloride hydration or exchanging sodium chloride by NaHCO3 hydration for multiple hours. One study (Weisbord, 2018) with 4,993 patients compared bicarbonate to sodium chloride hydration with an infusion protocol allowing different volume and duration of infusion in the protocols of the participating centers with a specified minimum required volume and duration of administration (see above) for coronary angiography and Garcia (2018) performed a subgroup analysis for 1,161 patients receiving PCI;

- One RCT compared in a non-inferiority trial, a 1-hour schedule of 250ml NaHCO3 1.4% versus 1000 ml NaCl 0,9% in 4-12h pre- and 4-12h post-CM administration in 548 CT patients. (Kooiman, 2014).

Table 4. Characteristics of included studies

|

Study |

Participants |

Comparison |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures |

Comments |

Risk of bias (per outcome measure)* |

|

Individual studies |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Adolph, 2008 |

N at baseline Intervention: 71 Control: 74

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 70 years (SD=8) Control: 73 years (SD=7)

Sex (male) Intervention: 53 (75%) Control: 60 (81%) |

Intervention: Sodium bicarbonate 154mEq/L in 5% dextrose solution 2ml/kg body weight/hour for 2 hours before And 1ml/kg body weight/hour during and for 6 hours after contrast administration Control: Sodium chloride 154 mEq/L in 5% dextrose solution 2ml/kg body weight/hour for 2 hours before And 1ml/kg body weight/hour during and for 6 hours after contrast administration |

2 days |

CIN, dialysis |

Source of funding not reported |

Unclear** |

|

Boccalandro, 2020 |

N at baseline Intervention: 190 Control: 192

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 68 years (SD=10) Control: 67 years (SD=13)

Sex (male) Intervention: 96 (51%) Control: 102 (53%)

|

Intervention: sodium chloride (154mEq/l NaCl with 5% dextrose solution) Control: sodium bicarbonate (150 mEq/l of sodium bicarbonate with 5% dextrose solution) Both administered at 3 ml/kg/h for 1 h before and during the angiographic procedure, followed by 1 ml/kg/h for 6 h post-procedure) |

Up to 60 months |

CA-AKI, renal replacement therapy, adverse events

|

No relation with industry and no financial support

In multivariate analysis significantly higher incidence of CA-AKI with diabetes, higher baseline creatinine, advanced age, and history of heart failure |

Low (all outcomes) |

|

Boucek, 2013 |

N at baseline Intervention: 61 Control: 59

Age (mean, SD) Intervention: 63 years (SD=11) Control: 67 years (SD=10)

Mean eGFR 44±18.

Planned procedure of CAG/PCI (35%) or lower limb angiography/angioplasty (60%)

Sex (male) Intervention: 46 (75%) Control: 44 (75%) |

Intervention: 1.4% sodium bicarbonate in 5% glucose 3ml/kg/hour 1 hour before contrast administration (limited to a maximum of 330mL) 1mL/kg/hour 6 hours after contrast administration (limited to a maximum of 660mL) Control: 0.9% sodium chloride in 5% glucose 3ml/kg/hour 1 hour before contrast administration (limited to a maximum of 330mL) 1mL/kg/hour 6 hours after contrast administration (limited to a maximum of 660mL)

|

2 days – laboratory parameters 1 month – clinical parameters

|

CIN defined by >25% increase of creatinine or >44 umol/l within 2 days after contrast, dialysis |

Commercial source of funding |

Low** |

|

Brar, 2008 |

N at baseline Intervention: 175 Control: 178