Evaluatie van eGFR

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe dient nierfunctie te worden gemeten voor en na jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel toediening?

Subvragen

- Wat is de beste manier om nierfunctie te meten?

- Wanneer dient een eGFR schatting te worden uitgevoerd vooraf aan toediening van jodiumhoudend contrast?

- Wanneer dient een eGFR schatting te worden uitgevoerd na toediening van jodiumhoudend contrast?

- Indien PC-AKI wordt gediagnosticeerd, hoe dient de patiënt vervolgd te worden?

- Hoe lang blijft een eGFR schatting geldig?

Aanbeveling

Aanbevelingen voor aanvragers van laboratoriumonderzoek

Bepaal de eGFR bij elke patiënt die een CT-scan of angiografie met of zonder interventie en gebruik van intravasculair jodiumhoudend CM ondergaat, voorafgaand aan dit aanvullend onderzoek.

De eGFR meting is geldig gedurende:

- maximaal 7 dagen: wanneer de patiënt een acute ziekte of een verergering van een chronische ziekte heeft;

- maximaal 3 maanden: wanneer de patiënt een chronische ziekte heeft met een stabiele nierfunctie;

- circa 12 maanden bij alle andere patiënten.

Bepaal de eGFR binnen 2 tot 7 dagen na intravasculaire jodiumhoudende CM-toediening bij elke patiënt bij wie voorzorgsmaatregelen tegen PC-AKI zijn genomen.

Indien er PC-AKI wordt gediagnostiseerd (volgens Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes criteria), vervolg de patiënt gedurende minstens 30 dagen na de diagnose en bepaal het serum-kreatinine.

Aanbevelingen voor klinisch chemici

Meet het plasma-kreatinine middels een selectieve (enzymatische) methode.

Gebruik de kreatinine-gebaseerde Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formule voor de schatting van de eGFR.

Overweeg om de eGFR berekend met de CKD-EPI-formule te corrigeren voor het lichaamsoppervlak, indien beschikbaar.

Overwegingen

Formulas

MDRD equation (Levey, 2006)

eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 175 × (Cr / 88.4)-1.154 × age-0.203 × 0.742 (if female)

× 1.210 (if African American)

CKD-EPI equation (Levey, 2009)

eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) =

Female Cr ≤ 62 µmol/l: 144 x (Cr / 62)-0.329 x 0.993Age

Female Cr > 62 µmol/l: 144 x (Cr / 62)-1.209 x 0.993Age

Male Cr ≤ 80 µmol/l: 141 x (Cr / 80)-0.411 x 0.993Age

Male Cr > 80 µmol/l: 141 x (Cr / 80)-1.209 x 0.993Age

x 1.159 (if African American).

Note that Cr denotes creatinine concentration in both plasma and serum in µmol/L.

Selected eGFR calculator links:

National Kidney Foundation (US)

https://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US)

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Currently, the measurement of creatinine using Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry (IDMS) is standardized. Worldwide standardization of creatinine measurement has been accomplished, but selectivity issues remain due to persistence of non-selective methods leading to inaccurate creatinine and eGFR results. It is the end-responsibility of the lab professional to select and implement accurate - selective - creatinine measurement methods for adequate patient care.

In addition, it should be noted that glomerular filtration rate (GFR), defined as ml/minute passing through the kidneys as a substitute for kidney function, essentially differs from creatinine clearance which is defined as: Urinary volume * ([creatinine]urine /[creatinine]plasma). In case of creatinine clearance, especially with low kidney filtration, creatinine clearance may exceed GFR up to 25% due to active tubular secretion of creatinine.

Assessment of eGFR in children is outside the scope of this guideline. Specific equations for the calculation of eGFR for children and elderly may be found elsewhere (Pottel, 2016; Schwartz, 2009; Schäffner, 2012). In addition, it is not necessary to adapt the CKD-EPI formula for patients >70 years of age.

Serum or plasma creatinine is the medical test of choice for evaluating kidney function in every laboratory in the Netherlands. Due to extensive standardization efforts both at the international and the national level, the inter-laboratory variability is far below 10%. As a result of ongoing improvements in creatinine assays, methods are now available for selective measurement of creatinine with high reproducibility and small variation. As a consequence of the low analytical (total CVa <2%) and biological variability (CVw = 4-7%), creatinine measurement is currently the most suitable test for assessment of kidney function. On the basis of its high reproducibility and low variability, the serum or plasma creatinine test is suitable for detection of minimal changes during treatment (Fraser, 2011), for monitoring kidney function after kidney transplantation or after contrast medium application, and for monitoring of disease progression.

Currently no alternative test of kidney function other than creatinine is available that is reimbursed and offers high analytical reliability and low biological variation. The use of beta-trace and Cystatin C has not been validated adequately for large cohorts and these tests are not widely available in Dutch clinical chemistry laboratories.

The current use of generic and broad reference values for creatinine covers up significant changes of kidney function within the reference interval. In addition, the use of broad reference values does not permit the follow-up of vulnerable patients with slowly deteriorating kidney function. As a consequence, it is suggested that in vulnerable patients, measurement of creatinine with increased frequency leads to early detection of kidney function deterioration. Using the formula for determination of the critical difference based upon individual and analytical variability (Fraser 2011), a deterioration of kidney function can be detected with high reliability. Applying a analytical and biological variation of 2% and 5% respectively (see above), a critical difference is detected with 95% certainty (Z value 1,96, Critical difference (%) = 1,96 * √(2)* √(√(CVa) + √(CVw))) when the two consecutive measurements of creatinine differ by at least 14,9%, e.g. when a value of 100 µmol/L increases to at least 115 µmol/L or a value of 150 µmol/L increases to at least 173 µmol/L.

Following the recent validation of the CKD-EPI formula in a large cohort by Levey et al. (Levey, 2009) and by using serum creatinine standardized to the IDMS reference system, the use of the CKD-EPI equation in Dutch hospitals has been deemed feasible. The use of additional formulas, e.g. the Lund-Malmo Revised equation is not deemed usable given the specific Swedish (Caucasian) population from which this formula was derived and validated (Nyman, 2014). As per 2015, the Dutch SKML chemistry section advises the use of the creatinine based CKD-EPI formula given its improved performance for CKD risk classification compared to the MDRD formula around the clinical decision limit of 60 ml/min/1.73m2.

In case the patient’s specific body surface area (BSA) is available, eGFR can be adjusted for BSA (also termed “absolute eGFR”) (Nyman, 2014).

Based upon a recent pilot study on differences in type and severity of comorbidity (Björk, 2010) and by using techniques of population weighted means, it can be estimated whether a patient has an eGFR <60 ml/min/1,73m2 or ≥60 ml/min/1,73m2. By stratifying patients according to their algorithms, the authors came to a preselection of patients with low or normal kidney function. In case a preselection is available of patients with increased risk for CKD or CIN follow up of these patients may be adjusted. The efficacy of these stratification studies however needs evaluation for the Dutch setting.

What is the best way to assess renal function?

Assessment of kidney function is preferable from a single measurement of an endogenous filtration marker. So far, several biomarkers have been evaluated (e.g. creatinine, Cystatin C, beta trace), although only creatinine has thus far found widespread use in most clinical chemistry laboratories. Serum creatinine measurements are the basis for creatinine-derived eGFR estimates. Historically, routine measurement of creatinine was performed using colorimetric Jaffe methods. The Jaffe method is however a chemical method affected by non-specificity since not only creatinine reacts with the alkaline picrate but also other analytes such as serum protein and glucose (Cobbaert, 2009).

The quality of the eGFR estimates is strongly dependent on serum creatinine measurement accuracy. For this reason, selective measurement of serum creatinine with analytical performance in line with desirable bias and imprecision criteria based on biological variation is paramount for guaranteeing metrological traceability. It should be kept in mind therefore that adequate risk classification using GFR critically depends on universal standardization and application of selective creatinine measurement procedures.

Following the first large study published in 1999 to estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), from creatinine (Levey, 1999), the MDRD formula was further improved by using isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS), (Levey, 2006) and is now subsequently replaced by the CKD-EPI equation (Levey, 2009; van den Brand, 2011). This succession of eGFR formula therefore illustrates an ongoing effort of methods to accurately estimate GFR rather than a defined endpoint. In brief, the advantage of the CKD-EPI equation, is the higher accuracy of eGFR predictions for normal kidney function than the MDRD equation. In addition, following the introduction of the CKD-EPI equation, a reduced number of patients is misclassified as compared with the MDRD equation, especially for eGFR values <60 ml/min/1.73m2.

Kidney function is likely stable in patients without chronic kidney disease. Extensive risk prediction model development has indicated that underlying comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease, increased age, heart failure or impaired ejection fraction, hypotension, hypertension or shock may correlate with the possible development of AKI but are not specific for PC-AKI. The applicability of current risk models in clinical practice is only modest (Silver, 2015).

With the use of an endogenous filtration marker it should be noted that any endogenous marker is influenced by several non-GFR determinants, such as body mass, diet, racial background, gender etc. Important considerations are that eGFR is unreliable in patients with acute kidney failure and may overestimate renal function in patients with a reduced muscle mass. When adapted for specific subpopulations e.g. on the basis of descend, improvements may be possible for eGFR values, this however lies outside of the scope of this guideline.

When should an eGFR calculation be performed prior to contrast administration?

Kidney function, assessed by eGFR is, according to the working group, likely stable in patients without chronic kidney disease or, underlying comorbidities such as heart failure or, hypertension and in the absence of the use of nephrotoxic medication. In these patients, considered to have normal kidney function, an eGFR measurement should be available within approximately 12 months before any CT imaging or angiography with or without intervention with the possible use of a contrast agent. Patients who are followed-up for oncological diseases are also included in this category.

It is the opinion of the working group that an eGFR result should not be more than 3 months old in patients with CKD, a known other chronic disease or the use of nephrotoxic drugs. Chronic disease is defined in analogy to WHO criteria: chronic or non-communicable diseases are of long (more than 3 months) duration and generally slow progression. The main types are cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic kidney diseases, chronic respiratory system diseases, chronic gastro-intestinal diseases, and chronic connective tissue and auto-immune diseases. (http://www.who.int/topics/noncommunicable_diseases/en/).

In patients with any acute disease or an acute deterioration of a chronic illness a recent eGFR, not more than 7 days old, is needed before CM administration. Frequently occurring examples include acute infections, acute cardiovascular diseases, acute gastro-intestinal diseases, respiratory diseases, acute kidney diseases, and acute connective tissue and auto-immune diseases. Also for all patients admitted to a hospital an eGFR <7 days old is needed before CM administration.

The nephrotoxicity of gadolinium-based contrast agents and/or microbubble contrast media and the recommendations for measurement of eGFR will be integrated with the guidelines for prevention of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. These will be published in the guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media, part 2 (due beginning of 2019).

When should an eGFR calculation be performed after the contrast administration?

There is no clear consensus guidance in the literature on this point. According to the Working Group, eGFR should be determined within 2-7 days after contrast administration in every patient with high risk for developing PC-AKI that receives preventive hydration. In patients requiring the continuation of metformin, an eGFR should be measured within 2 days. In most patients, a decreased kidney function may spontaneously resolve.

In patients without chronic kidney disease or, underlying co-morbidities such as heart failure, hypertension and not using nephrotoxic medication prior to the CM administration an eGFR determination after CM administration can be omitted.

If PC-AKI is diagnosed, how should the patient be followed-up?

In studies, eGFR was assessed after 2-3 days after CM administration to diagnose PC-AKI. In case PC-AKI is diagnosed within 2-7 days, additional follow-up is mandatory. It is the expert opinion of the Working Group that further follow-up is mandatory for patients in whom PC-AKI is diagnosed, for at least 30 days post-diagnosis with re-assessment of PC-AKI.

Emergency patients / procedures

In case of a major life-threatening medical condition requiring rapid decision-making including emergency imaging or intervention (e.g. stroke), the determination of the eGFR can be postponed or the imaging or intervention can be started while the eGFR is being determined in the laboratory. If the possibility exists to wait a short time before commencing diagnosis or intervention, without doing harm to the patient, eGFR should be determined immediately, and if indicated, individualized preventive measures should be taken before the administration of intravascular iodine-containing contrast medium.

Patient Questionnaires

In the Netherlands, for practical purposes the VMS Quality Project (VMS, 2009) has introduced to measure eGFR before every iodine-containing CM administration which has gained wide acceptance. This is not in accordance with scientific data which suggest that eGFR measurements can be performed only in patients at risk. Based on previously published risk factors (see also chapter 13 on Risk Stratification) several patient questionnaires to guide clinicians when to assess eGFR have gained popularity, especially the 6-question questionnaire (Choyke, 1998); which formed the basis for the more extensive questionnaire for multiple aspects of CM safety by the ESUR Contrast Media Safety Committee (Morcos, 2008).

For PC-AKI prevention when a contrast-enhanced examination with iodine-containing CM is planned, these questionnaires ask the patient and referring physician about: history of renal disease, history of renal surgery, and the presence of heart failure, diabetes, proteinuria, hypertension or gout. It has been shown that these simple questionnaires are sensitive in identifying patients with eGFR <45 ml/min/1.73m2 and can reduce the need for eGFR assessments via laboratory or point-of-care techniques, especially in patients younger than 70 years (Azzouz, 2014; Too, 2015; Zähringer, 2015).

Samenvatting literatuur

No literature search was performed for this chapter. The working group did not expect to find evidence for this question, since the clinical question could not be answered in a controlled study. Furthermore, the recommendations typically apply for the Dutch healthcare system.

Referenties

- Azzouz M, Rømsing J, Thomsen HS. Fluctuations in eGFR in relation to unenhanced and enhanced MRI and CT outpatients. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(6):886-92.

- Björk J, Grubb A, Sterner G, et al. A new tool for predicting the probability of chronic kidney disease from a specific value of estimated GFR. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2010;70(5):327-33.

- Choyke PL, Cady J, DePollar SL, et al. Determination of serum creatinine prior to iodine-containing contrast media: is it necessary in all patients? Tech Urol. 1998;4(2):65-9.

- Cobbaert CM, Baadenhuijsen H, Weykamp CW. Prime time for enzymatic creatinine methods in pediatrics. ClinChem. 2009;55(3):549-58.

- Fraser CG. Improved monitoring of differences in serial laboratory results. Clin Chem. 2011;57(12):1635-7.

- Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461-70.

- Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247-54.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-12.

- Morcos SK, Bellin MF, Thomsen HS, et al. Reducing the risk of iodine-based and MRI contrast media administration: recommendation for a questionnaire at the time of booking. Eu J Radiol. 2008;66(2):225-9.

- Nyman U, Grubb A, Larsson A, et al. The revised Lund-Malmö GFR estimating equation outperforms MDRD and CKD-EPI across GFR, age and BMI intervals in a large Swedish population. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52(6):815-24.

- Pottel H, Hoste L, Dubourg L, et al. An estimated glomerular filtration rate equation for the full age spectrum. Nephrol Dial Transplant.2016; 31(5), 798-806.

- Schäffner ES, Ebert N, Delanaye P, et al. Two novel equations to estimate kidney function in persons aged 70 years or older. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):471-81.

- Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(3):629-37.

- Silver SA, Shah PM, Chertow GM, et al. Risk prediction models for contrast induced nephropathy: systematic review. BMJ. 2015;351:h4395.

- Too CW, Ng WY, Tan CC, et al. Screening for impaired renal function in outpatients before iodinated contrast injection: Comparing the Choyke questionnaire with a rapid point-of-care-test. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84(7):1227-31.

- Van den Brand JA, van Boekel GA, Willems HL, et al. Introduction of the CKD-EPI equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate in a Caucasian population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(10):3176-81.

- Zähringer C, Potthast S, Tyndall AJ, et al. Serum creatinine measurements: evaluation of a questionnaire according to the ESUR guidelines. Acta Radiol. 2015;56(5):628-34.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 08-01-2018

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-11-2017

Validity

The board of the Radiological Society of the Netherlands will determine at the latest in 2023 if this guideline (per module) is still valid and applicable. If necessary, a new working group will be formed to revise the guideline. The validity of a guideline can be shorter than 5 years, if new scientific or healthcare structure developments arise, that could be seen as a reason to commence revisions. The Radiological Society of the Netherlands is considered the keeper of this guideline and thus primarily responsible for the actuality of the guideline. The other scientific societies that have participated in the guideline development share the responsibility to inform the primarily responsible scientific society about relevant developments in their field.

Initiative

Radiological Society of the Netherlands

Authorization

- The guideline is submitted for authorization to:

- Association of Surgeons of the Netherlands

- Dutch Association of Urology

- Dutch Federation of Nephrology

- Dutch Society Medical Imaging and Radiotherapy

- Dutch Society of Intensive Care

- Netherlands Association of Internal Medicine

- Netherlands Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Netherlands Society of Cardiology

- Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

- -Radiological Society of the Netherlands

Algemene gegevens

General Information

The guideline development was assisted by the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (https://www.kennisinstituut.nl) and was financed by the Quality Funds for Medical Specialists (Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten: SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Goal of the current guideline

The aim of the Part 1 of Safe Use of Iodine-containing Contrast Media guidelines is to critically review the present recent evidence with the above trend in mind, and try to formulate new practical guidelines for all hospital physicians to provide the safe use of contrast media in diagnostic and interventional studies. The ultimate goal of this guideline is to increase the quality of care, by providing efficient and expedient healthcare to the specific patient populations that may benefit from this healthcare and simultaneously guard patients from ineffective care. Furthermore, such a guideline should ideally be able to save money and reduce day-hospital waiting lists.

Users of this guideline

This guideline is intended for all hospital physicians that request or perform diagnostic or interventional radiologic or cardiologic studies for their patients in which CM are involved.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Working group members

A multidisciplinary working group was formed for the development of the guideline in 2014. The working group consisted of representatives from all relevant medical specialization fields that are involved with intravascular contrast administration.

All working group members have been officially delegated for participation in the working group by their scientific societies. The working group has developed a guideline in the period from October 2014 until July 2017.

The working group is responsible for the complete text of this guideline.

Working group

Cobbaert C., clinical chemist, Leiden University Medical Centre (member of advisory board from September 2015)

Danse P., interventional cardiologist, Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem

Dekker H.M., radiologist, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen

Geenen R.W.F., radiologist, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep (NWZ), Alkmaar/Den Helder

Hoogeveen E.K., nephrologist, Jeroen Bosch Hospital, ‘s-Hertogenbosch

Kooiman J., research physician, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden

Oudemans - van Straaten H.M., internist-intensive care specialist, Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam

Pels Rijcken T.H., interventional radiologist, Tergooi, Hilversum

Sijpkens Y.W.J., nephrologist, Haaglanden Medical Centre, The Hague

Vainas T., vascular surgeon, University Medical Centre Groningen (until September 2015)

van den Meiracker A.H., internist-vascular medicine, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam

van der Molen A.J., radiologist, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden (chairman)

Wikkeling O.R.M., vascular surgeon, Heelkunde Friesland Groep, location: Nij Smellinghe Hospital, Drachten (from September 2015)

Advisory board

Demir A.Y., clinical chemist, Meander Medical Center, Amersfoort, (member of working group until September 2015)

Hubbers R., patient representative, Dutch Kidney Patient Association

Mazel J., urologist, Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem

Moos S., resident in Radiology, HAGA Hospital, The Hague

Prantl K., Coordinator Quality & Research, Dutch Kidney Patient Association

van den Wijngaard J., resident in Clinical Chemistry, Leiden University Medical Center

Methodological support

Boschman J., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from May 2017)

Burger K., senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (until March 2015)

Harmsen W., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from May 2017)

Mostovaya I.M., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists

Persoon S., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (March 2016 – September 2016)

van Enst A., senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from January 2017)

Belangenverklaringen

Conflicts of interest

The working group members have provided written statements about (financially supported) relations with commercial companies, organisations or institutions that are related to the subject matter of the guideline. Furthermore, inquiries have been made regarding personal financial interests, interests due to personal relationships, interests related to reputation management, interest related to externally financed research and interests related to knowledge valorisation. The statements on conflict of interest can be requested at the administrative office of the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists and are summarised below.

|

Member |

Function |

Other offices |

Personal financial interests |

Personal relationships |

Reputation management |

Externally financed research |

Knowledge-valorisation |

Other potential conflicts of interest |

Signed |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Workgroup |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Van der Molen |

Chairman, radiologist |

Member Contrast Media Safety Committee of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (unpaid,CMSC meetings are partially funded by CM industry)) |

None |

None |

Secretary section of Abdominal Radiology; Radiological Society of the Netherlands (until spring of 2015) |

None |

None |

Receives Royalties for books: Contrast Media Safety, ESUR guidelines, 3rd ed. Springer, 2015 Received speaker fees for lectures on CM safety by GE Healthcare, Guerbet, Bayer Healthcare and Bracco Imaging (2015-2016) |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Geenen |

Member, radiologist |

Member Contrast Media Safety Committee of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (unpaid, meetings are partially funded by CM industry))) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Has been a public speaker during symposia organised by GE Healthcare about contrast agents (most recently in June 2014) |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dekker |

Member, radiologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pels Rijcken |

Member, interventional radiologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Danse |

Member, cardiologist |

Board member committee of Quality, Dutch society for Cardiology (unpaid) Board member Conference committee DRES (unpaid) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Oudemans – van Straaten |

Member, intensive care medical specialist Professor Intensive Care |

none |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hoogeveen |

Member, nephrologist |

Member of Guideline Committee of Dutch Federation of Nephrology |

None |

None |

Member of Guideline Committee of Dutch Society for Nephrology |

Grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation to study effect of fish oil on kidney function in post-MI patients |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sijpkens |

Member, nephrologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Van den Meiracker |

Member, internist vascular medicine |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cobbaert |

Member, physician clinical chemistry |

Head of clinical chemistry department in Leiden LUMC. Tutor for post-academic training of clinical chemists, coordinator/host for the Leiden region Member of several working groups within the Dutch Society for Clinical Chemistry and member of several international working groups for clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

Member of several working groups within the Dutch Society for Clinical Chemistry and member of several international working groups for clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wikkeling |

Member, vascular surgeon |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Vainas |

Member, vascular surgeon |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kooiman |

Member, research physician |

Resident in department of gynaecology & obstetrics |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Burger |

Advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mostovaya |

Advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Advisory Board |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Prantl |

Member, policy maker, Dutch Society of Kidney Patients |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hubbers |

Member, patient’s representative, Dutch Society of Kidney Patients |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mazel |

Member, urologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Van den Wijngaard |

Member, resident clinical chemistry |

Reviewer for several journals (such as American Journal of Physiology) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Demir |

Member, physician clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Input of patient’s perspective

Patients’ perspective was represented, firstly by membership and involvement in the advisory board of a policy maker and a patients’ representative from the Dutch Kidney Patient Association. Furthermore, an online survey was organized by the Dutch Kidney Patient Association about the subject matter of the guideline. A summary of the results of this survey has been discussed during a working group meeting at the beginning of the guideline development process. Subjects that were deemed relevant by patients were included in the outline of the guideline. The concept guideline has also been submitted for feedback during the comment process to the Dutch Patient and Consumer Federation, who have reported their feedback through the Dutch Kidney Patient Association.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In the different phases of guideline development, the implementation of the guideline and the practical enforceability of the guideline were taken into account. The factors that could facilitate or hinder the introduction of the guideline in clinical practice have been explicitly considered. The implementation plan can be found with the Related Products. Furthermore, quality indicators were developed to enhance the implementation of the guideline. The indicators can also be found with the Related Products.

Werkwijze

AGREE

This guideline has been developed conforming to the requirements of the report of Guidelines for Medical Specialists 2.0; the advisory committee of the Quality Counsel. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (www.agreetrust.org), a broadly accepted instrument in the international community and on the national quality standards for guidelines: “Guidelines for guidelines” (www.zorginstituutnederland.nl).

Identification of subject matter

During the initial phase of the guideline development, the chairman, working group and the advisor inventory the relevant subject matter for the guideline. Furthermore, an Invitational Conference was organized, where additional relevant subjects were suggested by the Dutch Kidney Patient Association, Dutch Society for Emergency Physicians, and Dutch Society for Urology. A report of this meeting can be found in Related Products.

Clinical questions and outcomes

During the initial phase of guideline development, the chairman, working group and advisor identified relevant subject matter for the guideline. Furthermore, input was acquired for the outline of the guideline during an Invitational Conference. The working group then formulated definitive clinical questions and defined relevant outcome measures (both beneficial land harmful effects). The working group rated the outcome measures as critical, important and not important. Furthermore, where applicable, the working group defined relevant clinical differences.

Strategy for search and selection of literature

For the separate clinical questions, specific search terms were formulated and published scientific articles were sought after in (several) electronic databases. Furthermore, studies were looked for by cross-referencing other included studies. The studies with potentially the highest quality of research were looked for first. The working group members selected literature in pairs (independently of each other) based on title and abstract. A second selection was performed based on full text. The databases search terms and selection criteria are described in the modules containing the clinical questions.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Individual studies were systematically assessed, based on methodological quality criteria that were determined prior to the search, so that risk of bias could be estimated. This is described in the “risk of bias” tables.

Summary of literature

The relevant research findings of all selected articles are shown in evidence tables. The most important findings in literature are described in literature summaries. When there were enough similarities between studies, the study data were pooled.

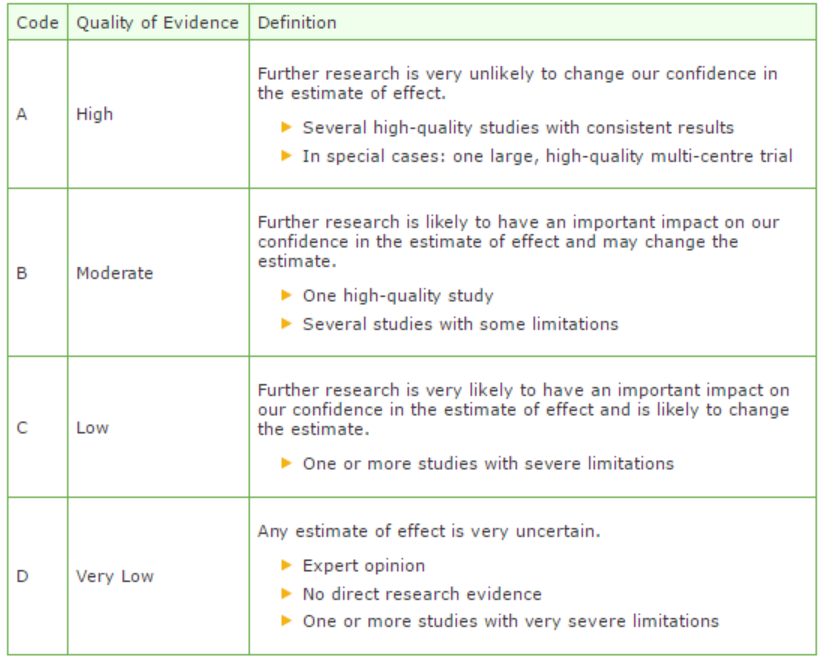

Grading the strength of scientific evidence

A) For intervention questions

The strength of the conclusions of the scientific publications was determined using the GRADE-method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/) (Atkins, 2004).

GRADE defines four gradations for the quality of scientific evidence: high, moderate, low or very low. These gradations provide information about the amount of certainty about the literature conclusions. (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook/).

B) For diagnostic, etiological, prognostic or adverse effect questions, the GRADE-methodology cannot (yet) be applied. The quality of evidence of the conclusion is determined by the EBRO method (van Everdingen, 2004)

Formulating conclusion

For diagnostic, etiological, prognostic or adverse effect questions, the evidence was summarized in one or more conclusions, and the level of the most relevant evidence was reported. For intervention questions, the conclusion was drawn based on the body of evidence (not one or several articles). The working groups weighed the beneficial and harmful effects of the intervention.

Considerations

Aspects such as expertise of working group members, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities, and organization of healthcare aspects are important to consider when formulating a recommendation. These aspects were discussed in the paragraph Considerations.

Formulating recommendations

The recommendations answer the clinical question and were based on the available scientific evidence and the most relevant considerations.

Constraints (organization of healthcare)

During the development of the outline of the guideline and the rest of the guideline development process, the organization of healthcare was explicitly taken into account. Constraints that were relevant for certain clinical questions were discussed in the Consideration paragraphs of those clinical questions. The comprehensive and additional aspects of the organization of healthcare were discussed in a separate chapter.

Development of quality indicators

Internal (meant for use by scientific society or its members) quality indicators are developed simultaneously with the guideline. Furthermore, existing indicators on this subject were critically appraised; and the working group produces an advice about such indicators. Additional information on the development of quality indicators is available by contacting the Knowledge Institute for Medical Specialists. (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl).

Knowledge Gaps

During the development of the guideline, a systematic literature search was performed the results of which help to answer the clinical questions. For each clinical question the working group determined if additional scientific research on this subject was desirable. An overview of recommendations for further research is available in the appendix Knowledge Gaps.

Comment- and authorisation phase

The concept guideline was subjected to commentaries by the involved scientific societies. The commentaries were collected and discussed with the working group. The feedback was used to improve the guideline; afterwards the working group made the guideline definitive. The final version of the guideline was offered for authorization to the involved scientific societies, and was authorized.

References

Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, et al. GRADE Working Group. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004 Dec 22;4(1):38.

Van Everdingen JJE, Burgers JS, Assendelft WJJ, et al. Evidence-based richtlijnontwikkeling. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. Houten, 2004