Risicofactoren en preventie van NSF

Uitgangsvraag

a) Welke patiënten hebben en verhoogd risico op het ontwikkelen van Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF)?

b) Welke maatregelen zijn nodig om NSF te voorkomen?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik laag-risico (ionisch en non-ionisch) macrocyclische GBCAs voor medische beeldvorming bij alle patiënten. Lineaire GBCA is geassocieerd met NSF, daarom dient lineaire GBCA enkel overwogen te worden indien een macrocyclisch GBCA de diagnostische vraag niet kan beantwoorden.

Maak een individuele risico-voordeel analyse met de aanvragend arts van de patiënt en met een nefroloog om verzekerd te zijn van een strikte indicatie voor MRI met lineaire GBCA bij patiënten met eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2.

Voor preventie van NSF bij patiënten die al afhankelijk zijn van hemodialyse of peritoneale dialyse, hoeft de toediening van macrocyclische GBCA niet direct gevolgd te worden door een hemodialyse sessie.

Om de hoeveelheid circulerend GBCA te minimaliseren, dient bij patiënten die al chronische hemodialyse ondergaan de toediening van lineaire GBCA direct te worden gevolgd door een (high-flux) hemodialyse sessie, wat herhaald wordt in de twee opeenvolgende dagen.

Bij predialyse patiënten (eGFR<15 ml/min/1.73m2) en peritoneaal dialyse patiënten dient het risico op NSF door lineaire GBCA te worden afgewogen tegen het risico van het plaatsen van een tijdelijke centraal veneuze toegang voor hemodialyse.

Overwegingen

Prevalence and risk of NSF and type of GBCA

The majority of histology proven NSF cases has been described between 1997 and 2007, which largely consisted of cases with a temporal relation with high dose linear gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) administrations (Attari, 2019). Several meta-analysis have shown a positive correlation between GBCA and NSF, predominantly based on studies using linear GBCA (Agarwal, 2009; Zhang, 2015). The risk of NSF relate to the administered dose and physiochemical characteristics of GBCAs, including pharmacodynamic stability, kinetic stability, and the amount of excess ligand (Khawaja, 2015).

In a risk-factor analysis of 370 biopsy-proven published NSF cases following use of linear GBCA it was concluded that reductions in risk may be attained with: 1) avoiding high doses of GBCA (> 0.1 mmol/kg); 2) avoiding nonionic linear GBCA in patients undergoing dialysis and patients with eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2, especially in the setting of pro-inflammatory conditions; 3) dialyzing quickly after GBCA administration for patients already on dialysis; and 4) avoiding GBCA in acute renal failure (Zou, 2011).

By combining pharmacovigilance (Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)) and legal databases, a total of 382 biopsy-proven, product-specific cases of NSF were analysed. Of these, 279 cases were unconfounded and all involved a linear GBCA, nonionic more than ionic, and most frequently gadodiamide. No unconfounded cases were found for gadoteridol or gadobenate (Edwards, 2014).

A very recent study based on a legal database containing biopsy-proven, unconfounded NSF cases has estimated that a total of 197 and 8 cases have been reported for the linear GBCAs gadodiamide and gadoversetamide, respectively. Estimated incidences of NSF based on the FAERS analysis are 13.1/million and 5.0/million administrations for the linear non-ionic GBCAs gadodiamide and gadoversetamide worldwide (Semelka, 2019).

Considering the hypothesized pathophysiology of NSF involving free circulating gadolinium ions, macrocyclic GBCAs are considered to have a higher thermodynamic and kinetic stability and thus less associated with the risk of NSF (Sherry, 2009).

The prevalence of NSF after use of macrocyclic GBCA is very low. No cases of NSF have been found in large studies using gadobenate (Bruce, 2016), gadobutrol (Michaely, 2017), and gadoteridol or gadobenate (Soulez, 2015). Using the Girardi criteria for diagnosis, the worldwide total number of unconfounded cases for gadobutrol is 3 (Elmholdt, 2010; Endrikat, 2018), while there were no cases for gadoteridol (Reilly, 2008; Edwards, 2014), or gadoterate (Soyer, 2017).

In addition, there have been no unconfounded cases reported for the hepatobiliary linear GBCA gadobenate (Edwards, 2014) and gadoxetate (Endrikat, 2018). Patients with chronic liver diseases that are awaiting or undergoing liver transplantation are no longer consider to be an independent risk factor for NSF (Smorodinsky, 2015).

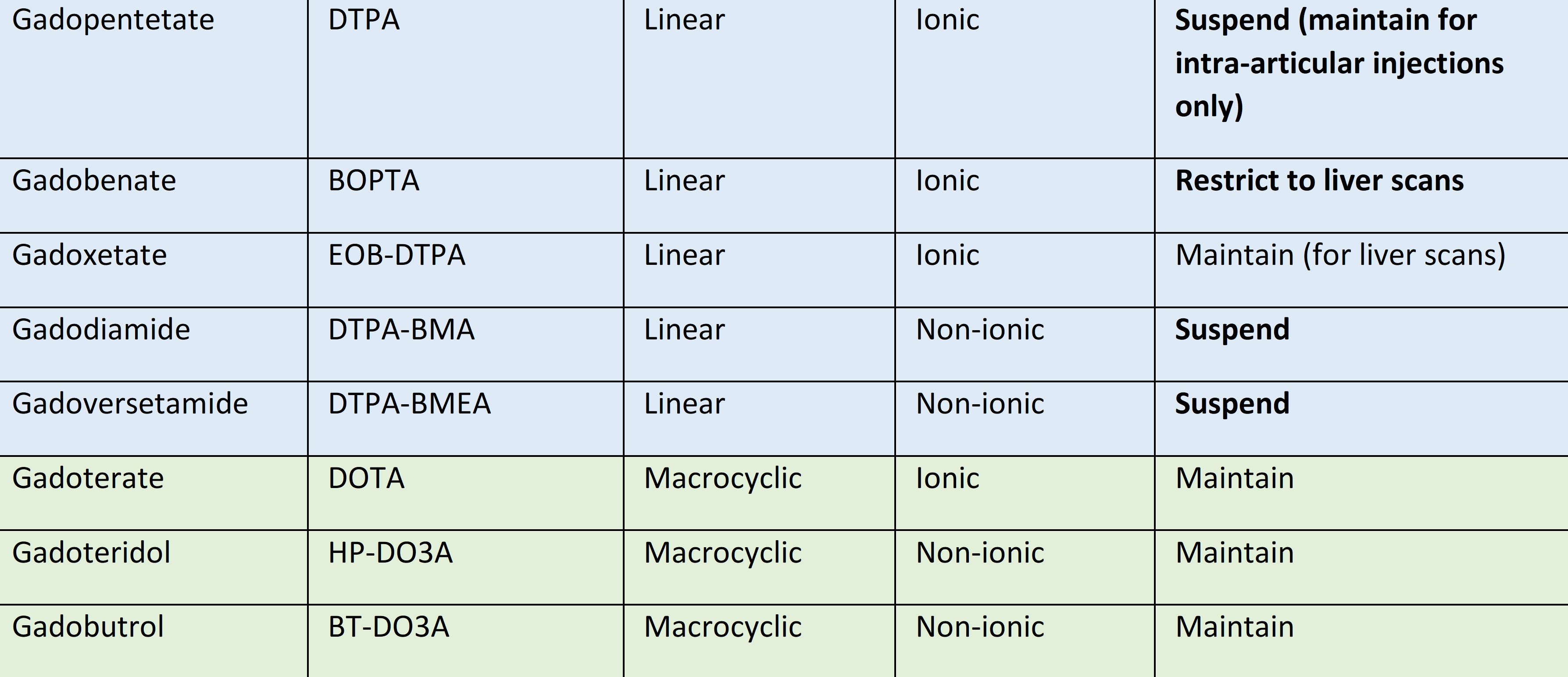

On March 17, 2016, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) initiated a review of the risk of gadolinium deposition in brain tissue following the repeated use of GBCAs in patients undergoing contrast-enhanced MRI scans. Following an in-depth review, the EMA issued its final recommendations on July 21, 2017, endorsed by the European Commission on November 23, 2017, and now applicable in all EU Member States limiting the use of GBCAs to macrocyclic GBCAs and restricting the use of linear GBCAs to selected indications, such as hepatobiliary MRI or MR arthrography (EMA, 2017; Dekkers, 2018). See Table 1 for overview of GBCAs and recommendations of the EMA.

Table 1 Overview of available GBCAs and the EMA recommendation (Dekkers, 2018)

Considering these new regulations, previous perceived risks for NSF based on linear GBCAs should be differentiated from the risks that apply to macrocyclic GBCAs. From the data currently available, for the GBCA currently allowable in Europe the risk of NSF is extremely low, even in patients with eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2 and patients on dialysis.

Haemodialysis to prevent NSF

Several studies have been performed to investigate the dialysability of GBCAs. These studies have shown that a single haemodialysis session can remove around 65-97% of circulating GBCA, whereby success depends on dialysis technique (high flux, large pore membranes (Ueda 1999)). Approximately 98% is eliminated after three consecutive dialysis sessions (Joffe 1998; Tombach 2002; Gheuens 2014). Based on these data, early haemodialysis would be an effective treatment for preventing NSF. However, this hasn’t been proven. For example, a retrospective chart review described ten haemodialysis patients who developed NSF after administration of GBCA. In none of these patients, immediate haemodialysis after injection with GBCA could prevent NSF (Broome 2007).

Based on the dialysability of GBCAs and the fact that NSF is a potential lethal condition, many guidelines recommend scheduling GBCA administration shortly before the next haemodialysis session (ACR Manual 10.3; ESUR Guideline v10).

Peritoneal dialysis does not effectively remove gadolinium (Rodby 2018). However, instituting haemodialysis in a peritoneal dialysis patient without a functioning vascular access goes with a significant risk, as it is an invasive treatment that requires placement of a temporary haemodialysis catheter. The same accounts for predialysis patients (eGFR<15 ml/min/1.73m2).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a very rare, idiopathic, progressive, systemic fibrosis disease that has been associated with renal insufficiency and could result in significant disability due to scleromyxedema-like cutaneous manifestations and mortality. Since there is currently no consistently effective treatment, NSF prevention would be essential, ideally by confirming risk factors for the disease.

Risk factors for NSF

Little is known about the pathophysiology of NSF and it has been postulated that the deposition of free gadolinium causes fibrous connective tissue formation (Ting, 2003). It has been described to occur after exposure to linear gadolinium based contrast agents (GBCA) in particular. Literature published prior to 2007 has not only suggested that free gadolinium, particularly gadodiamide, is a trigger of NSF, but has reported a strong causal relationship between gadolinium exposure and the development of NSF (Thomsen, 2016). However, this association may be affected by other factors or cofactors, such as dosage or type of GBCA, dialysis modality, renal disease severity, liver transplantation, chronic inflammation, or accelerated atherosclerosis.

Prevention of NSF

Several measures to prevent the development of NSF can be taken. As such, the use of high risk and high dose GBCAs should be avoided. An alternative to scanning with GBCA is to scan with the use of iodinated contrast media, however this carries the risk of post-contrast acute kidney injury (see Module 6). Since the connection between NSF and GBCA has become known, changes in CM administration protocols with lower GBCA concentration and use of macrocyclic GBCAs has led to a decrease in NSF incidence. Reports are showing virtually no new NSF cases since 2008 in both patients with normal renal function and patients with renal impairment, in spite of continued use of GBCA, albeit at lower doses and by using preferentially the macrocyclic preparations.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

There seems to be no association between co-morbidities (history of hypothyroidism or deep venous thrombosis, and dependent oedema) and risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients on dialysis receiving linear GBCAs.

Source: (Kallen, 2008)) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Research question a: Risk factors for NSF

Studies that assessed risk factors related to administration of type and dose of gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCA) have been described in the module nephrotoxicity of gadolinium-based contrast agents. There was 1 additional study included investigating other potential factors associated to NSF. Kallen (2008) performed a matched case-control study (19 cases and 57 controls), however this study was restricted to linear GBCAs only. Participants were dialysis patients with and without a diagnosis of NSF treated at an academic medical centre.

Results

Outcome- comorbidities

In a multivariate analysis Kallen (2008) found no association between NSF and selected exposures (history of hypothyroidism (OR, 95% CI: 4.18 0.66 to 26.57); history of deep venous thrombosis (OR, 95% CI: 3.37 0.60-18.85), and dependent oedema (OR, 95% CI: 3.15 0.67 to 14.77).

Quality of evidence

The quality of certainty of evidence was downgraded from high to very low: downgraded by two levels due to imprecision (small number of patients), and indirectness (NB. only linear GBCAs were administered to the patients in the study which are no longer available on the European Market).

Research question b: Prevention of NSF

Not applicable. There were no studies investigating the research question and meeting the selection criteria.

Zoeken en selecteren

Research question a: Risk factors for NSF

To answer the clinical question a systematic literature analysis was performed:

Search question: What factors are related to an increased risk on Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis?

P (Patient): Patients with reduced kidney function or other potential risk factors that are scheduled to receive intravascular contrast media.

I (Intervention): Patients with potential risk factors for NSF: Patient-related, pre-existing chronic kidney disease, Renal insufficiency, chronic CKD, Age 70 years and older, Liver transplantation, Liver failure, Kidney transplantation, Chronic inflammation, Atherosclerosis, Peripheral arterial disease, Dialysis, Renal replacement therapy, Diabetes Mellitus, type 1 or type 2, Congestive heart failure NYHA grade III-IV, Dehydration, Multimorbidity, Concurrent use of nephrotoxic medications: NSAIDs, Cox-2 inhibitors, ACE-inhibitor, ARB-blocker, other Dialysis modality (Peritoneal or haemodialysis), Recent dialysis shunt / PD catheter, Acidosis, EPO use, Dose of contrast and type of contrast (GBCA).

C (Comparison): Patients without potential risk factors for NSF.

O (Outcomes): Frequency of NSF, systemic fibrosis, scleroderma, dialysis-associated systemic fibrosis.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered nephrogenic systemic fibrosis as a critical outcome measure for the decision making process.

Methods

The databases Medline (OVID) and Embase were searched from January 2000 till February 23th 2018 using relevant search terms for systematic reviews (SRs), randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies (OBS).

The literature search procured 228 hits: 22 SR, 20 RCTs and 186 OBS. Based on title and abstract a total of 20 studies were selected. After examination of full text 19 studies were excluded and 1 study involving linear GBCAs was included in the literature summary. No studies were identified involving macrocyclic GBCAs, which are currently the only agents available in the European market.

Research question b: Prevention of NSF

To answer the clinical question a systematic literature analysis was performed for the search question: What is the effect of the different measures to prevent nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients who have an increased risk of developing nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and who receive contrast with gadolinium?

P (Patient): Patients exposed to gadolinium-based contrast agents who have an increased risk of developing nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF).

I (Intervention): Measures for prevention of NSF.

C (Comparison): No measures or other measures for prevention of NSF.

O (Outcomes): Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF), mortality.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) and mortality as critical outcome measures for the decision making process.

Methods

The databases Medline (OVID) and Embase were searched from January 1996 till March 23th 2018 using relevant search terms for systematic reviews (SRs), randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies (OBS).

The literature search procured 142 hits. 7 SR, 10 RCTs, 43 OBS, and 82 other types of studies. Based on title and abstract a total of 29 studies were selected. After examination of full text all studies were excluded and no studies have definitely been included in the literature summary.

Referenties

- American College of Radiology. ACR Manual on contrast media, v10.3. Available at: www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Contrast-Manual. Accessed: 11 july 2019

- Agarwal R, Brunelli SM, Williams K, Mitchell MD, Feldman HI, Umscheid CA. Gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24: 856-863.

- Attari H, Cao Y, Elmholdt TR, Zhao Y, Prince MR. A systematic review of 639 patients with biopsy-confirmed Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. Radiology 2019; in press. Doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019182916

- Broome DR, Girguis MS, Baron PW, Cottrell AC, Kjellin I, Kirk GA. Gadodiamide-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: why radiologists should be concerned. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188: 586-592 (see also correspondence)

- Bruce R, Wentland AL, Haemel AK, Garrett RW, Sadowski DR, Djamali A, et al. Incidence of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis using gadobenate dimeglumine in 1423 patients with renal insufficiency compared with gadodiamide. Invest Radiol 2016; 51:701-705

- Dekkers IA, Roos R, van der Molen AJ. Gadolinium retention after administration of contrast agents based on linear chelators and the recommendations of the European Medicines Agency. Eur Radiol 2018; 28:1579-1584

- Edwards BJ, Laumann AE, Nardone B, Miller FH, Restaino J, Raisch DW, et al. Advancing pharmacovigilance through academic-legal collaboration: the case of gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis-a Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports (RADAR) report. Br J Radiol 2014; 87(1042): 20140307

- Elmholdt TR, Jørgensen B, Ramsing M, Pedersen M, Olesen AB. Two cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to the macrocyclic compound gadobutrol. NDT Plus. 2010; 3: 285-287 (Correspondence in NDT Plus. 2010; 3: 501-504)

- Endrikat J, Dohanish S, Schleyer N, Schwenke S, Agarwal S, Balzer T. 10 years of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a comprehensive analysis of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis reports received by a pharmaceutical company from 2006 to 2016. Invest Radiol 2018; 53: 541-550

- European Medicines Agency. EMA’s final opinion confirms restrictions on use of linear gadolinium agents in body scans (21 july 2017). Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/gadolinium-article-31-referral-emas-final-opinion-confirms-restrictions-use-linear-gadolinium-agents_en-0.pdf

- European Society of Urogenital Radiology Contrast Media Safety Committee. ESUR Guidelines on contrast safety, v10. Available at: www.esur-cm.org. Accessed: 11 july 2019

- Haustein J, Schuhmann-Giampieri G. Elimination of Gd-DTPA by means of hemodialysis. Eur J Radiol 1990; 11: 227-229.

- Joffe P, Thomsen HS, Meusel M. Pharmacokinetics of gadodiamide injection in patients with severe renal insufficiency and patients undergoing hemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Acta Radiol 1998; 5: 491–502.

- Kallen AJ, Jhung MA, Cheng S, Hess T, Turabelidze G, Abramova L, et al. Gadolinium-containing magnetic resonance imaging contrast and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case-control study. Am J Kidney Dis 2008; 51: 966-975.

- Khawaja AZ, Cassidy DB, Al Shakarchi J, McGrogan DG, Inston NG, Jones RG. Revisiting the risks of MRI with Gadolinium based contrast agents - review of literature and guidelines. Insights Imaging 2015; 6: 553-558.

- Michaely HJ, Aschauer M, Deutschmann H, Bongartz G, Gutberlet M, Woitek R, et al. Gadobutrol in renally impaired patients: results of the GRIP Study. Invest Radiol 2017; 52: 55-60

- Reilly RF. Risk for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with gadoteridol (ProHance) in patients who are on long-term hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3: 747-751.

- Rodby RA. Dialytic therapies to prevent NSF following gadolinium exposure in high-risk patients. Semin Dial 2008; 21: 145-149

- Semelka RC, Prybylski JP, Ramalho M. Influence of excess ligand on Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis associated with nonionic, linear gadolinium-based contrast agents. Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 58: 174-178.

- Sherry AD, Caravan P, Lenkinski RE. Primer on gadolinium chemistry. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 30: 1240–1248.

- Soulez G, Bloomgarden DC, Rofsky NM, Smith MP, Abujudeh HH, Morgan DE, et al. Prospective cohort study of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease undergoing MRI with injected gadobenate dimeglumine or gadoteridol. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 205: 469-478.

- Smorodinsky E, Ansdell DS, Foster ZW, Mazhar SM, Cruite I, Wolfson T, et al. Risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is low in patients with chronic liver disease exposed to gadolinium‐based contrast agents. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 41: 1259-1267.

- Soyer P, Dohan A, Patkar D, Gottschalk A. Observational study on the safety profile of gadoterate meglumine in 35,499 patients: The SECURE study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017 Apr;45(4):988-997.

- Thomsen HS, Morcos SK, Almén T, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and gadolinium-based contrast media: updated ESUR Contrast Medium Safety Committee guidelines. Eur Radiol 2013; 23: 307-318.

- Thomsen HS. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a serious adverse reaction to gadolinium – 1997-2006-2016. Part 1 Acta Radiol 2016; 57: 515-520.

- Thomsen HS. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a serious adverse reaction to gadolinium – 1997-2006-2016. Part 2 Acta Radiol 2016; 57: 643-648.

- Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, Kurtz K. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol 2003; 139: 903-906.

- Tombach B, Bremer C, Reimer P, Matzkies F, Schaefer RM, Ebert W, et al. Using highly concentrated gadobutrol as an MR contrast agent in patients also requiring hemodialysis: safety and dialysability. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 178: 105-109

- Ueda J, Furukawa T, Higashino K, Yamamoto T, Ujita H, Sakaguchi K, Araki Y. Permeability of iodinated and MR contrast media through two types of hemodialysis membrane. Eur J Radiol. 1999; 31: 76-80

- Zhang B, Liang L, Chen W, Liang C, Zhang S.An Updated Study to Determine Association between Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents and Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0129720.

Evidence tabellen

a) Exclusion Table after full text review

|

Author, year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Agarwal 2009 |

Does not fulfil PICO criteria: no prognostic factors included |

|

Bahrami 2009 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (univariate) |

|

Bernstein 2014 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (univariate) |

|

Bruce 2016 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis |

|

Deray 2014 |

Does not fulfil PICO criteria: no prognostic factors included |

|

Elmholdt 2011 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (univariate) |

|

Lauenstein 2015 |

Does not fulfil PICO criteria: no prognostic factors included |

|

Marckmann 2007 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (univariate) |

|

Martin 2010 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis |

|

Mazhar 2009 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (descriptive statistics) |

|

Michaely 2017 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (descriptive statistics) |

|

Nacif 2012 |

Does not fulfil PICO criteria: no prognostic factors included |

|

Othersen 2007 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (descriptive statistics) |

|

Rydahl 2008 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (descriptive statistics) |

|

Soulez 2015 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (descriptive statistics) |

|

Todd 2007 |

Does not fulfil PICO criteria: no prognostic factors NSF included |

|

Wang 2011 |

Does not fulfil selection criteria: no multivariate analysis (univariate) |

|

Zhang 2015 |

Does not fulfil PICO criteria: no rognostic factors included |

b) Exclusion Table after full text review

|

Author (year) |

Reasons for exclusion |

|

Andrews (2008) |

Not original research: comment |

|

Broome (2007) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention/measures |

|

Coletti (2008) |

Not original research: comment |

|

Dawson (2008) |

Not original research: narrative |

|

Dawson (2008) |

Not original research: comment |

|

Gheuens (2014) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention NSF |

|

Kitajima (2012) |

No original research: narrative |

|

Knopp (2008) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention/measures |

|

Murashima (2008) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention NSF |

|

Nicolas (2012) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention/measures comparative research |

|

Panesar (2010) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention |

|

Perazella (2008) |

Not original research: guideline |

|

Perazella (2009) |

Not original research: narrative |

|

Prince (2008) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention/measures |

|

Prince (2009) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention/measures |

|

Rodby (2008) |

Not original research: narrative |

|

Saab (2007) |

Not original research: comment |

|

Sena (2010) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention NSF |

|

Silberzweig (2009) |

Not original research: narrative |

|

Swaminathan (2007) |

Not original research: narrative |

|

Thomsen (2007) |

Not original research: guideline |

|

Thomsen (2008) |

Not original research: narrative |

|

Thomsen (2013) |

Not original research: guideline |

|

Tran (2009) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no prevention |

|

Wiginton (2008) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention/measures |

|

Yantasee (2010) |

Not original research: narrative |

|

Yee (2017) |

Not original research: editorial |

|

Zhang (2015) |

Does not meet PICO criteria: no intervention/measures |

|

Zou (2011) |

No original research: narrative |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 06-03-2020

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 24-06-2020

Validity

The board of the Radiological Society of the Netherlands will determine at the latest in 2024 if this guideline (per module) is still valid and applicable. If necessary, a new working group will be formed to revise the guideline. The validity of a guideline can be shorter than 5 years, if new scientific or healthcare structure developments arise, that could be seen as a reason to commence revisions. The Radiological Society of the Netherlands is considered the keeper of this guideline and thus primarily responsible for the actuality of the guideline. The other scientific societies that have participated in the guideline development share the responsibility to inform the primarily responsible scientific society about relevant developments in their field.

Initiative

Radiological Society of the Netherlands

Authorization

The guideline is submitted for authorization to:

- Association of Surgeons of the Netherlands

- Dutch Association of Hospital Pharmacists

- Dutch Federation of Nephrology

- Dutch Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology

- Dutch Society for Dermatology and Venereology

- Dutch Society of Intensive Care

- Netherlands Association of Internal Medicine

- Netherlands Society of Cardiology

- Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

- Netherlands Society of Intensive Care

- Radiological Society of the Netherlands

Algemene gegevens

General Information

The guideline development was assisted by the Knowledge Institute of the Federation Medical Specialists (www.kennisinstituut.nl) and was financed by the Quality Funds for Medical Specialists (Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten: SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Goal

The aim of the Part 2 of Safe Use of Contrast Media guidelines is to critically review the present recent evidence with the above trend in mind and tries to formulate new practical guidelines for all hospital physicians to provide the safe use of contrast media in diagnostic and interventional studies. The ultimate goal of this guideline is to increase the quality of care, by providing efficient and expedient healthcare to the specific patient populations that may benefit from this healthcare and simultaneously guard patients from ineffective care. Furthermore, such a guideline should ideally be able to save money and reduce day-hospital waiting lists.

Users

This guideline is intended for all hospital physicians that request or perform diagnostic or interventional radiologic or cardiologic studies for their patients in which CM are involved.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Working group members

A multidisciplinary working group was formed for the development of the guideline in 2016. The working group consisted of representatives from all relevant medical specialization fields that are involved with intravascular contrast administration.

All working group members have been officially delegated for participation in the working group by their scientific societies. The working group has developed a guideline in the period from May 2016 until July 2019.

The working group is responsible for the complete text of this guideline.

Working group

Brummer I., emergency physician, Treant Healthcare Group, Emmen

de Geus H.R.H., internist-intensivist, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam

de Monchy J.G.R., allergologist, DC-Klinieken, Amsterdam

Dekker H.M., radiologist, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen

Dekkers I.A., clinical epidemiologist and radiologist in training, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden

Geenen R.W.F., radiologist, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep (NWZ), Alkmaar

Gotte M., cardiologist, Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam (from July 2018)

Kardaun S.H., dermatologist, University Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen (until March, 2018)

Leiner T., radiologist, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht (until November 2018)

van der Molen A.J., radiologist, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden (chairman)

van der Putten K., nephrologist, Tergooi, Hilversum

van der Vlugt M., cardiologist, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen (until April 2018)

Wikkeling O.R.M., vascular surgeon, Heelkunde Friesland Groep, location: Nij Smellinghe Hospital, Drachten

Zielhuis S.W., hospital pharmacist, Medical Centre Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden

Methodological support

Buddeke J., advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Federation Medical Specialists (from April 2018)

Harmsen W., advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Federation Medical Specialists (from April 2018)

Mostovaya I.M., senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of the Federation Medical Specialists

Belangenverklaringen

Conflicts of interest

The working group members have provided written statements about (financially supported) relations with commercial companies, organisations or institutions that are related to the subject matter of the guideline. Furthermore, inquiries have been made regarding personal financial interests, interests due to personal relationships, interests related to reputation management, interest related to externally financed research and interests related to knowledge valorisation. The statements on conflict of interest can be requested at the administrative office of the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists and are summarised below.

|

Last name |

Function |

Other positions |

Personal financial interests |

Personal relations |

Reputation management |

Externally financed research |

Knowledge valorisation |

Other interests |

Signed |

|

Brummer |

Emergency physician |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

February 23rd, 2018 |

|

De Geus |

Internist-Intensivist Erasmus MC Rotterdam |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

March 31st, 2016 |

|

Dekker |

Radiologist |

None |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

July 10th, 2016 |

|

Dekkers |

Radiologist in training and PhD-candidate |

None |

None |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

July 8th, 2016 |

|

Geenen |

Radiologist |

Member of commission prevention of PC-AKI |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Has held several presentation about contrast media on invitation (GE, BAYER) |

March 25th, 2016 |

|

Kardaun |

Dermatologist – researcher Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen: unpaid |

Replacing dermatologist in clinical practice - unpaid |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

February 24th, 2016 |

|

Roodheuvel |

Emergency physician |

Instructor OSG/VvAA for courses on echography – paid position Member of department for burn treatment – unpaid. |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

December 21st, 2015 |

|

Van der Molen |

Chairman |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Not applicable |

One-off royalties Springer Verlag (2014) Incidental payments for presentations or being day chairman at contrast safety congress (2016 Netherlands + Europe |

September 6th, 2016 |

|

Van der Putten |

Internist nephrologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

October 14th, 2015 |

|

Van der Vlugt |

Cardiologist |

None |

None |

None |

Chairman of the working group Cardiac MRI & CT and Nuclear imaging of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology |

None |

None |

None |

March 1st, 2016 |

|

Wikkeling |

Vascular surgeon |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Not applicable |

July 19th, 2016 |

|

Zielhuis |

Hospital pharmacist |

None |

In the past (2013-2015) has participated in an advisory panel on expensive medication for the companies AbbVie and Novartis. Has received an expense allowance for this. Both forms do not produce contrast media that this guideline is about. Currently not active in an advisory panel. |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

January 8th, 2016 |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Input of patient’s perspective

It was challenging to find representation for the patient’s perspective, since the guideline does not discuss a specific group of patients with a disease. The Dutch Kidney Patients Association was invited to participate in an advisory board to the working group, but declined since this subject was not specific enough for them to give adequate input; The Dutch Kidney Patients Association did provide written feedback for specific modules during the commentary phase. The Dutch Kidney Patients Association and the Patient Federation of the Netherlands was invited to participate in the invitational conference in which the framework of the guideline was discussed. Furthermore, the concept guideline has been submitted for feedback during the comment process to the Patient Federation of the Netherlands and the Dutch Kidney Patient Association.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Implementation

In the different phases of guideline development, the implementation of the guideline, and the practical enforceability of the guideline were taken into account. The factors that could facilitate or hinder the introduction of the guideline in clinical practice have been explicitly considered. The implementation plan can be found with the Related Products. Furthermore, quality indicators were developed to enhance the implementation of the guideline. The indicators can also be found with the Related Products.

Werkwijze

Methodology

AGREE

This guideline has been developed conforming to the requirements of the report of Guidelines for Medical Specialists 2.0 by the advisory committee of the Quality Counsel (www.kwaliteitskoepel.nl). This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (www.agreetrust.org), a broadly accepted instrument in the international community and on the national quality standards for guidelines: “Guidelines for guidelines” (www.zorginstituutnederland.nl).

Identification of subject matter

During the initial phase of the guideline development, the chairman, working group and the advisor inventory the relevant subject matter for the guideline. Furthermore, an Invitational Conference was organized, where additional relevant subjects were discussed. A report of this meeting can be found in Related Products.

Clinical questions and outcomes

During the initial phase of guideline development, the chairman, working group and advisor identified relevant subject matter for the guideline. Furthermore, input was acquired for the outline of the guideline during an Invitational Conference. The working group then formulated definitive clinical questions and defined relevant outcome measures (both beneficial land harmful effects). The working group rated the outcome measures as critical, important and not important. Furthermore, where applicable, the working group defined relevant clinical differences.

Strategy for search and selection of literature

For the separate clinical questions, specific search terms were formulated and published scientific articles were sought after in (several) electronic databases. Furthermore, studies were scrutinized by cross-referencing for other included studies. The studies with potentially the highest quality of research were looked for first. The working group members selected literature in pairs (independently of each other) based on title and abstract. A second selection was performed based on full text. The databases, search terms and selection criteria are described in the modules containing the clinical questions.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Individual studies were systematically assessed, based on methodological quality criteria that were determined prior to the search, so that risk of bias could be estimated. This is described in the “risk of bias” tables.

Summary of literature

The relevant research findings of all selected articles are shown in evidence tables. The most important findings in literature are described in literature summaries. When there were enough similarities between studies, the study data were pooled.

Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations

The strength of the conclusions of the scientific publications was determined using the GRADE-method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/) (Atkins, 2004).

GRADE defines four gradations for the quality of scientific evidence: high, moderate, low or very low. These gradations provide information about the amount of certainty about the literature conclusions. (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook/).

Formulating conclusions

For diagnostic, etiological, prognostic or adverse effect questions, the evidence was summarized in one or more conclusions, and the level of the most relevant evidence was reported. For intervention questions, the conclusion was drawn based on the body of evidence (not one or several articles). The working groups weighed the beneficial and harmful effects of the intervention.

Considerations

Aspects such as expertise of working group members, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities and organisation of healthcare aspects are important to consider when formulating a recommendation. These aspects were discussed in the paragraph Considerations.

Formulating recommendations

The recommendation answers the clinical question and was based on the available scientific evidence and the most relevant considerations.

Constraints (Organisation of healthcare)

During the development of the outline of the guideline and the rest of the guideline development process, the Organisation of healthcare was explicitly taken into account. Constraints that were relevant for certain clinical questions were discussed in the Consideration paragraphs of those clinical questions. The comprehensive and additional aspects of the Organisation of healthcare were discussed in a separate chapter.

Development of quality indicators

Internal (meant for use by scientific society or its members) quality indicators are developed simultaneously with the guideline. Furthermore, existing indicators on this subject were critically appraised; and the working group produces an advice about such indicators. Additional information on the development of quality indicators is available by contacting the Knowledge Institute for the Federation Medical Specialists. (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl).

Knowledge Gaps

During the development of the guideline, a systematic literature search was performed the results of which help to answer the clinical questions. For each clinical question the working group determined if additional scientific research on this subject was desirable. An overview of recommendations for further research is available in the appendix Knowledge Gaps.

Comment- and authorisation phase

The concept guideline was subjected to commentaries by the involved scientific societies. The commentaries were collected and discussed with the working group. The feedback was used to improve the guideline; afterwards the working group made the guideline definitive. The final version of the guideline was offered for authorization to the involved scientific societies and was authorized.

References

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-E842.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0. Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit, 2012. Available at: http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available at: http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1106-10. Erratum published in: BMJ 2008;336(7654).

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Zoekverantwoording

Question 7a

|

Database |

Search String |

Total |

|

PubMed 2000 – February 2018 |

(('contrast medium'/exp OR 'contrast medi*':ti,ab OR 'contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'contrast material*':ti,ab OR 'contrast induced':ti,ab OR 'contrast related':ti,ab OR 'contrast exposure':ti,ab OR 'contrast dosage':ti,ab OR 'contrast dose*':ti,ab OR 'contrast enhanced':ti,ab OR 'contrast administration':ti,ab OR 'gadolinium'/exp OR gadolinium*:ti,ab OR gbca*:ti,ab OR primovist:ti,ab OR eovist:ti,ab OR omniscan:ti,ab OR magnevist:ti,ab OR optimark:ti,ab OR prohance:ti,ab OR multihance:ti,ab OR dotarem:ti,ab OR gadovist:ti,ab OR gadodiamide:ti,ab OR gadopentetat*:ti,ab OR gadoversetamide:ti,ab OR gadoteridol:ti,ab OR gadobenate:ti,ab OR gadoterate:ti,ab OR 'gadofosveset trisodium':ti,ab OR gadobutrol:ti,ab OR 'gadoxetic acid':ti,ab OR 'gadoxetate disodium':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa':ti,ab OR 'gd hp do3a':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa bma':ti,ab OR 'gd dota':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa bmea':ti,ab OR 'gd bopta':ti,ab OR 'gd bt do3a':ti,ab OR 'gd eob dtpa':ti,ab OR meglumine:ti,ab OR dimeglumine:ti,ab OR 'ultrasound contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'us contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'ultrasound contrast medi*':ti,ab OR sonovue:ti,ab OR optison:ti,ab OR perflutren:ti,ab OR hexafluoride:ti,ab OR 'barium'/exp OR barium:ti,ab OR micropaque:ti,ab OR 'e z cat':ti,ab OR polibar:ti,ab OR barite:ti,ab OR baritop:ti,ab) AND ('nephrogenic systemic fibrosis'/exp/mj OR 'nephrogenic systemic fibros*':ti OR nsf:ti OR 'nephrogenic fibrosing dermopath*':ti OR nfd:ti)) AND ([dutch]/lim OR [english]/lim) NOT [conference abstract]/lim AND [2000-2018]/py Filter SR: ('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) = 11 Filter RCT: ((random*[tiab] AND (controlled[tiab] OR control[tiab] OR placebo[tiab] OR versus[tiab] OR versus[tiab] OR group[tiab] OR groups[tiab] OR comparison[tiab] OR compared[tiab] OR arm[tiab] OR arms[tiab] OR crossover[tiab] OR cross-over[tiab]) AND (trial[tiab] OR study[tiab])) OR ((single[tiab] OR double[tiab] OR triple[tiab]) AND (masked[tiab] OR blind*[tiab]))) OR ((random*[ot] AND (controlled[ot] OR control[ot] OR placebo[ot] OR versus[ot] OR versus[ot] OR group[ot] OR groups[ot] OR comparison[ot] OR compared[ot] OR arm[ot] OR arms[ot] OR crossover[ot] OR cross-over[ot]) AND (trial[ot] OR study[ot])) OR ((single[ot] OR double[ot] OR triple[ot]) AND (masked[ot] OR blind*[ot]))) = 7 Filter observationele studies: "cohort studies"[mesh] OR "case-control studies"[mesh] OR "comparative study"[pt] OR "risk factors"[mesh] OR "cohort"[tw] OR "compared"[tw] OR "groups"[tw] OR "case control"[tw] OR "multivariate"[tw] = 205 = 211 uniek |

228 |

|

Embase (Elsevier) |

(('contrast medium'/exp OR 'contrast medi*':ti,ab OR 'contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'contrast material*':ti,ab OR 'contrast induced':ti,ab OR 'contrast related':ti,ab OR 'contrast exposure':ti,ab OR 'contrast dosage':ti,ab OR 'contrast dose*':ti,ab OR 'contrast enhanced':ti,ab OR 'contrast administration':ti,ab OR 'gadolinium'/exp OR gadolinium*:ti,ab OR gbca*:ti,ab OR primovist:ti,ab OR eovist:ti,ab OR omniscan:ti,ab OR magnevist:ti,ab OR optimark:ti,ab OR prohance:ti,ab OR multihance:ti,ab OR dotarem:ti,ab OR gadovist:ti,ab OR gadodiamide:ti,ab OR gadopentetat*:ti,ab OR gadoversetamide:ti,ab OR gadoteridol:ti,ab OR gadobenate:ti,ab OR gadoterate:ti,ab OR 'gadofosveset trisodium':ti,ab OR gadobutrol:ti,ab OR 'gadoxetic acid':ti,ab OR 'gadoxetate disodium':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa':ti,ab OR 'gd hp do3a':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa bma':ti,ab OR 'gd dota':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa bmea':ti,ab OR 'gd bopta':ti,ab OR 'gd bt do3a':ti,ab OR 'gd eob dtpa':ti,ab OR meglumine:ti,ab OR dimeglumine:ti,ab OR 'ultrasound contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'us contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'ultrasound contrast medi*':ti,ab OR sonovue:ti,ab OR optison:ti,ab OR perflutren:ti,ab OR hexafluoride:ti,ab OR 'barium'/exp OR barium:ti,ab OR micropaque:ti,ab OR 'e z cat':ti,ab OR polibar:ti,ab OR barite:ti,ab OR baritop:ti,ab) AND ('nephrogenic systemic fibrosis'/exp/mj OR 'nephrogenic systemic fibros*':ti OR nsf:ti OR 'nephrogenic fibrosing dermopath*':ti OR nfd:ti)) AND ([dutch]/lim OR [english]/lim) NOT [conference abstract]/lim AND [2000-2018]/py Filter SR: ('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) = 11 Filter RCT: ('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it = 23 Filter observationele studies: 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR ('prospective study'/de NOT 'randomized controlled trial'/de) OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (case:ab,ti AND ((control NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti)) OR (follow:ab,ti AND ((up NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti)) OR ((observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) = 59 = 82 uniek |

Question 7b

|

Database |

Search String |

Total |

|

PubMed 1996 – March 2018

|

((Gadolinium-based[tiab] OR "Gadolinium"[Mesh] OR gadolinium[tiab] OR magnetic resonance contrast agent*[tiab] OR MR contrast agent*[tiab] OR magnetic resonance contrast media[tiab] OR MR contrast media[tiab] OR MRI contrast agent*[tiab] OR MRI contrast medium[tiab] OR MRI contrast media[tiab] OR GBCA*[tiab] OR Primovist[tiab] OR Eovist[tiab] OR Omniscan[tiab] OR Magnevist[tiab] OR Optimark[tiab] OR Prohance[tiab] OR Multihance[tiab] OR Dotarem[tiab] OR Gadovist[tiab] OR gadodiamide[tiab] OR gadopentetate[tiab] OR gadoversetamide[tiab] OR gadoteridol[tiab] OR gadobenate[tiab] OR gadoterate[tiab] OR gadobutrol[tiab] OR gadoxetic acid[tiab] OR gadoxetate disodium[tiab] OR "Gadolinium DTPA"[Mesh] OR Gd-DTPA[tiab] OR Gd-HP-DO3A[tiab] OR Gd-DTPA-BMA[tiab] OR Gd-DOTA[tiab] OR Gd-DTPA-BMEA[tiab] OR Gd-BOPTA[tiab] OR Gd-BT-DO3A[tiab] OR Gd-EOB-DTPA[tiab] OR meglumine[tiab] OR dimeglumine[tiab] OR ultrasound contrast agent*[tiab] OR US contrast agent*[tiab] OR ultrasound contrast medi*[tiab] OR Sonovue[tiab] OR Optison[tiab] OR perflutren[tiab] OR hexafluoride[tiab] OR "Barium"[Mesh] OR Barium[tiab] OR Micropaque[tiab] OR E-Z-CAT[tiab] OR E Z CAT[tiab] OR Polibar[tiab] OR Barite[tiab] OR Baritop[tiab]) AND ("Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy"[Mesh] OR Nephrogenic systemic fibros* [tiab] OR NSF [tiab] OR Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopath* [tiab] OR NFD[tiab]) AND (prevent*[tiab] OR "prevention and control" [Subheading]) AND (("1996/01/01"[PDat] : "3000/12/31"[PDat]) AND English[lang])) NOT (animals[mh] NOT humans[mh]) = 109 |

142 |

|

Embase (Elsevier) |

(('gadolinium-based':ti,ab OR 'gadolinium'/exp OR gadolinium:ti,ab OR 'magnetic resonance contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'mr contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'magnetic resonance contrast media':ti,ab OR 'mr contrast media':ti,ab OR 'mri contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'mri contrast medium':ti,ab OR 'mri contrast media':ti,ab OR gbca*:ti,ab OR primovist:ti,ab OR eovist:ti,ab OR omniscan:ti,ab OR magnevist:ti,ab OR optimark:ti,ab OR prohance:ti,ab OR multihance:ti,ab OR dotarem:ti,ab OR gadovist:ti,ab OR gadodiamide:ti,ab OR gadopentetate:ti,ab OR gadoversetamide:ti,ab OR gadoteridol:ti,ab OR gadobenate:ti,ab OR gadoterate:ti,ab OR gadobutrol:ti,ab OR 'gadoxetic acid':ti,ab OR 'gadoxetate disodium':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa':ti,ab OR 'gd hp do3a':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa bma':ti,ab OR 'gd dota':ti,ab OR 'gd dtpa bmea':ti,ab OR 'gd bopta':ti,ab OR 'gd bt do3a':ti,ab OR 'gd eob dtpa':ti,ab OR meglumine:ti,ab OR dimeglumine:ti,ab OR 'ultrasound contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'us contrast agent*':ti,ab OR 'ultrasound contrast medi*':ti,ab OR sonovue:ti,ab OR optison:ti,ab OR perflutren:ti,ab OR hexafluoride:ti,ab OR 'barium'/exp OR barium:ti,ab OR micropaque:ti,ab OR 'e z cat':ti,ab OR polibar:ti,ab OR barite:ti,ab OR baritop:ti,ab) AND ('nephrogenic systemic fibrosis'/exp OR 'nephrogenic systemic fibros*':ti,ab OR nsf:ti,ab OR 'nephrogenic fibrosing dermopath*':ti,ab OR nfd:ti,ab) AND (prevent*:ti,ab OR 'prevention and control'/exp)) AND [english]/lim AND [1996-2018]/py NOT 'conference abstract':it NOT ([animals]/lim NOT [humans]/lim) = 84 |

|