Type vaginale kunstverlossing

Uitgangsvraag

Uitgangsvraag 3a1

Welk type kunstverlossing heeft de voorkeur bij een indicatie voor een vaginale kunstverlossing in de à terme periode: de vacuümcup of de forceps?

Uitgangsvraag3a2

Welk type vacuümcup heeft de voorkeur bij een indicatie voor een vacuümextractie in de à terme periode: de soft cup of de harde cup?

Uitgangsvraag 3b1

Welk type kunstverlossing heeft de voorkeur bij een indicatie voor een vaginale kunstverlossing in de preterme periode: de vacuümcup of de forceps?

Uitgangsvraag 3b2

Welk type vacuümcup heeft de voorkeur bij een indicatie voor een vacuüm extractie in de preterme periode: de soft cup of de harde cup?

Aanbeveling

Verricht bij een indicatie voor een vaginale kunstverlossing in de à terme periode in principe een vacuümextractie, tenzij hiervoor een contra-indicatie bestaat.

Laat de keuze voor het te gebruiken instrument bij een indicatie voor een vaginale kunstverlossing in de preterme periode afhangen van de voorkeur en ervaring van de parteur en eventuele contra-indicaties voor een van de instrumenten.

Overwegingen

In de literatuur zijn er in gerandomiseerde studies aanwijzingen voor geringe verschillen tussen de effectiviteit en veiligheid van de vacuümpomp en de forceps bij een vaginale kunstverlossing in de à terme periode. De overall bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten perinatale sterfte, keizersnede en succesvolle vaginale bevalling is zeer laag. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten is er bewijs van hoge kwaliteit dat er bij gebruik van een forceps ten opzichte van een vacuümpomp een grotere kans bestaat op (ernstige) perineumschade (RR 1,89; 95%CI 1,51 tot 2,37). Hoewel geen uitkomstmaat in deze literatuuranalyse rapporteert O’Mahony (2010) een grotere kans op verwondingen aan het gelaat of faciale parese bij de neonaat bij gebruik van een forceps (RR 5,10; 95%CI 1,12 tot 23,25).

Er wordt een trend gezien naar een grotere kans op een sectio caesarea na een mislukte forcipale extractie dan na een vacuümextractie (RR 1.76, 95% CI 0.95 tot 3.23) met een zeer lage bewijskracht, terwijl bij gebruik van de forceps de kans op niet slagen van de interventie kleiner lijkt dan na een vacuümextractie. Dit zou kunnen verklaard kunnen worden doordat na falen van een vacuümextractie soms wordt overgegaan tot een forcipale extractie en meestal niet omgekeerd.

Internationaal bestaan er verschillen in de voorkeur voor het gebruik van de verschillende instrumenten. Het is onduidelijk of de invloed van het gekozen instrument hetzelfde is in verschillende populaties. De ervaring van de parteur zou bij gebruik van een forceps mogelijk van grotere invloed kunnen zijn op de effectiviteit en veiligheid dan bij een vacuümextractie. In landen waar veel ervaring is met het gebruik van de forceps is de kans op complicaties daarom mogelijk lager.

Er is bewijs van redelijke kwaliteit dat het gebruik van een softcup de kans op een niet succesvolle baring door middel van het gekozen instrument verhoogt en dat het de kans op een cefaal hematoom verlaagt ten opzichte van een harde cup. Er zijn geen significante verschillen gevonden in de andere kritieke uitkomstmaten, te weten kans op een sectio caesarea en neonatale mortaliteit.

In de preterme periode zijn er geen gerandomiseerde onderzoeken die rapporteren over de effectiviteit en veiligheid van het gebruikte instrument. Er is één cohortstudie waaruit op basis van bewijs van zeer lage kwaliteit geconcludeerd kan worden dat het onduidelijk is of er een voorkeur bestaat voor gebruik van een harde of zachte vacuüm cup of een forceps.

Doel van een vaginale kunstverlossing is een vaginale baring met een goede uitkomst voor moeder en kind. Op grond van de beschikbare literatuur bestaat er in de à terme periode een voorkeur voor een vacuümextractie, tenzij hiervoor contra-indicaties zijn. Aangezien er in de preterme periode op grond van de literatuur geen duidelijke voorkeur bestaat voor de ene boven de andere methode zullen maternale en neonatale belangen per casus tegen elkaar afgewogen moeten worden. De keuze van het instrument dient daarom af te hangen van het oordeel en de expertise van de zorgverlener, de aanwezigheid van eventuele contra-indicaties en na counseling en met toestemming van de individuele patiënt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen gegevens betreffende de kosteneffectiviteit van beide behandelingen, maar de verwachting is niet dat dit grote consequenties zal hebben voor de maatschappij en het ziekenhuis-/ afdelingsbudget in de Nederlandse setting.

Aanvaardbaarheid voor de overige relevante stakeholders

Bezwaren worden niet verwacht.

Haalbaarheid en implementatie

De aanbevelingen zijn conform de reeds geldende richtlijnen en klinische praktijk. Belemmerende factoren worden daarom niet verwacht. Er is geen onderzoek gedaan naar de haalbaarheid.

Ervaring met het verrichten van een forcipale extractie neemt af, mede vanwege de hogere kans op maternale perineum en/of sfincter laesies. Het is aannemelijk dat de veiligheid en effectiviteit van deze methode daardoor zal afnemen. Toch blijven er situaties bestaan waarbij de forceps de voorkeur geniet boven een vacuümextractie (onder andere mogelijke stollingsstoornissen bij de neonaat, skeletdysplasie, aangezichtsligging). Blijvende aandacht voor (fantoom) onderwijs en aandacht voor deze interventie zijn daarom wenselijk.

Rationale/ balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Er is bewijs van hoge kwaliteit dat er meer bekkenbodemschade voorkomt bij gebruik van een forceps ten aanzien van een vacuümpomp. De kans op neonatale morbiditeit lijkt wat hoger bij een forcipale extractie echter het bewijs hiervoor is niet solide. Een forcipale extractie lijkt wat vaker succesvol dan een vacuümextractie, maar met een grotere kans op perineumschade en geboortetraumata. Er is geen bewijs voor een uniforme manier waarop deze factoren ten opzichte van elkaar gewogen dienen te worden. Dit zal geïndividualiseerd dienen te worden.

Een softcup verdient wellicht de voorkeur indien geen moeizame kunstverlossing wordt verwacht of in geval van een premature partus, maar dat is een overweging, geen harde aanbeveling.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Een instrumentele vaginale kunstverlossing, door middel van een vacuümcup of forceps, is geassocieerd met een verhoogde frequentie van geboortetraumata en totaalrupturen. Bij een vaginale kunstverlossing wordt de keuze van het instrument, behalve door de genoemde foetale en maternale risico's, in belangrijke mate bepaald door het niveau van training en ervaring van de arts met het betreffende instrument. In Nederland is het percentage forcipale extracties de afgelopen decennia afgenomen en het percentage vacuümextracties toegenomen (referentie). Daarnaast bestaan ook Internationaal bestaan verschillen tussen de voorkeur voor en ervaring met het gebruik van de verschillende instrumenten. Het is onduidelijk welk instrument het meest veilig en effectief is in de à terme en in de preterme periode.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

First comparison (3a1): any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term

|

Moderate GRADE |

In term assisted vaginal deliveries the use of forceps likely reduces the risk of failed delivery with the allocated instrument compared to ventouse.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010; Shekhar, 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of forceps compared to ventouse in term assisted vaginal deliveries on the risk of neonatal death.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010; Shekhar, 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of forceps compared to ventouse in term assisted vaginal deliveries on the risk of any neonatal injury.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Low GRADE |

In term assisted vaginal deliveries the use of ventouse may reduce the risk of the need for a Caesarean Section compared to forceps.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

High GRADE |

In term assisted vaginal deliveries the use of ventouse reduces the risk of third- or fourth-degree perineal tear (with or without episiotomy) or severe maternal soft tissue trauma compared to forceps.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010; Shekhar, 2013) |

|

Low GRADE |

In term assisted vaginal deliveries the use of forceps may result in little to no difference in the risk of low Apgar score at 5 minutes compared to ventouse.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Low GRADE |

In term assisted vaginal deliveries the use of ventouse may reduce the risk of scalp injury compared to forceps.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Low GRADE |

In term assisted vaginal deliveries the use of forceps may result in little to no effect on the need for admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit compared to ventouse.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn for the outcome measures infections, mother-child attachment, breast feeding, patient satisfaction regarding the delivery and maternal PTSS due to lack of studies reporting these outcomes. |

Second comparison (3a2): use of soft cup versus rigid cup ventouse at term

|

Moderate GRADE |

In term ventouse deliveries the use of a metal cup likely reduces the risk of failed delivery with the allocated instrument compared to a soft cup.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a metal cup compared to a soft cup in term ventouse deliveries on the risk of neonatal death.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a metal cup compared to a soft cup in term ventouse deliveries on the need for Caesarean Section.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a metal cup compared to a soft cup in term ventouse deliveries on the risk of low Apgar score at 5 minutes.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Low GRADE |

In term ventouse deliveries use of a soft cup may result in a reduction in the risk of admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit compared to a metal cup.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

In term ventouse deliveries the use of a soft cup likely reduces the risk of scalp injury or scalp abrasion compared to a metal cup.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

Low GRADE |

In term ventouse deliveries the use of a metal cup may result in little to no difference in the risk of a third- or fourth-degree perineal tear compared to a soft cup.

Bronnen: (O’Mahony, 2010) |

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions could be drawn for the outcomes infections, mother-child attachment, breast feeding, patient satisfaction with regard to the delivery and maternal Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome due to lack of studies reporting these outcomes. |

First comparison (3b1): any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse preterm

|

Very low GRADE |

In preterm assisted vaginal deliveries the evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of forceps compared to ventouse on the chance of delivery with the allocated instrument.

Bronnen: (Corcoran, 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

In preterm assisted vaginal deliveries the evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of forceps compared to ventouse on the risk of neonatal death.

Bronnen: (Corcoran, 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

In preterm assisted vaginal deliveries the evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of forceps compared to ventouse on low Apgar score at 5 minutes.

Bronnen: (Corcoran, 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

In preterm assisted vaginal deliveries the evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of forceps compared to ventouse on the risk of admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

Bronnen: (Corcoran, 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

In preterm assisted vaginal deliveries the evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of forceps compared to ventouse on the risk of intraventricular haemorrhage.

Bronnen: (Corcoran, 2013) |

|

- GRADE |

No conclusions were formulated for the neonatal outcomes or any maternal outcomes due to lack of studies reporting these outcomes. |

Second comparison (3b2): soft cup versus metal cup ventouse

|

- GRADE |

No grade assessment for this comparison due to lack of studies reporting this comparison in the study population preterm deliveries. |

Samenvatting literatuur

One systematic review was selected (O’Mahony, 2010), including 32 RCTs (n=6506) published between 1964 and 2008, and one RCT (n=100) (Shekhar, 2013).

The systematic review (O’Mahony, 2010) only included RCTs, but gestational age was not specified as an inclusion criterion. Several comparisons were reported, of which two are presented here, i.e. 1) any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse, and 2) soft cup versus metal cup. Since the publication of this SR one RCT was identified (Shekhar, 2013), only including women with term labour (n=100). Shekhar (2013) compared the Bird modification of the Malmstrom instrument with Das variety of long curved forceps and Wrigley’s outlet forceps in India with regard to the following outcomes: delivery with the intended instrument, severe maternal soft tissue trauma (extension to fornix, 3rd degree perineal tear, cervical tear, paraurethral tear), cephalhematoma, facial palsy, and neonatal death.

Results

Results 3a1: any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term.

This comparison was addressed by O’Mahony et al. 2010 and by Shekhar, 2013.

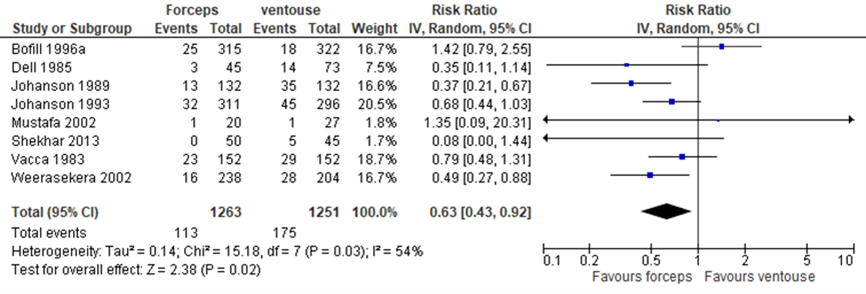

1. Failed delivery with allocated instrument (Fig. 3.1). For this outcome the pooled RR (95% CI) was 0.63 (0.43 to 0.92) favouring forceps over ventouse (heterogeneity (I2): 54%) (O’Mahony, 2010; Shekhar, 2013). From the information on primary studies presented in the SR by O’Mahoney et al. the cause of heterogeneity is not clear.

Figure 3.1 Comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term; outcome failed delivery with allocated instrument. Adapted from O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure failed delivery with allocated instrument started high and was downgraded by 1 level because of conflicting results (inconsistency) (I2) = 54%).

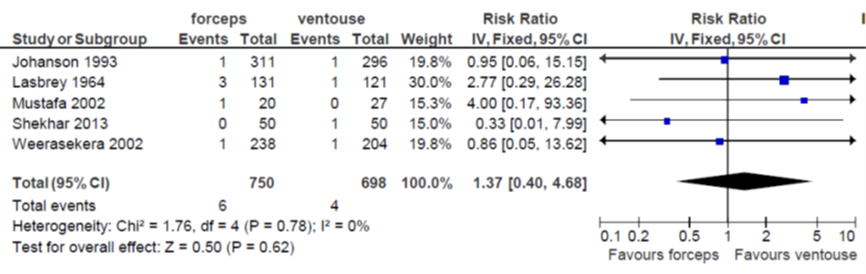

2. Neonatal death (Fig. 3.2). The pooled RR (95% CI) reported by O’Mahony (2010) was 1.75 (0.46 to 6.68) favouring ventouse (heterogeneity (I2): 0%). Shekhar (2013) reported a RR (95% CI) of 0.33 (0.01 to 7.99) in favour of forceps. The combined pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.37 (0.40 to 4.68) in favour of ventouse over forceps (O’Mahony, 2010; Shekhar, 2013).

Figure 3.2. Comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term; outcome neonatal death. Adapted from O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal death started high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low; 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision) since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions, and 1 level because of inconsistency (the power of the test for heterogeneity is low in case of few studies and few events; point estimates of individual studies vary considerably).

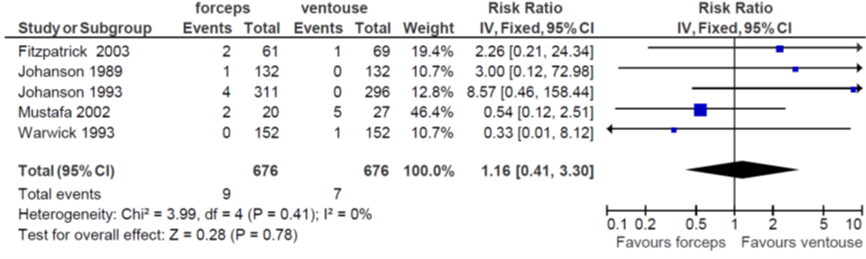

3. Any neonatal injury (Fig. 3.3). The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.16 (95% CI 0.41 to 3.30) favouring ventouse over forceps (heterogeneity (I2): 0%) (O’Mahony, 2010).

Figure 3.3 Comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term; outcome any neonatal injury. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure any neonatal injury started high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low; 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision), since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions, and 1 level because of inconsistency (the power of the test for heterogeneity is low in case of few studies and few events; point estimates of individual studies vary considerably).

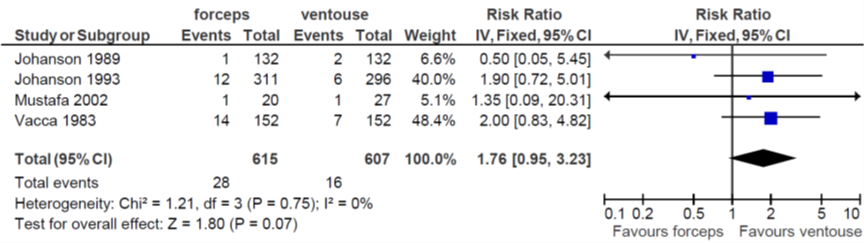

4. Caesarean section (Fig. 3.4). The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.76 (0.95 to 3.23) favouring ventouse over forceps (heterogeneity (I2): 0%) (O’Mahony, 2010).

Figure 3.4 Comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term; outcome Caesarean section. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure caesarean section started high and was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of number of included patients (imprecision), since the 95% CI exceeds the boundary of statistical significance and the boundary of clinical relevance.

5. Third- or fourth-degree perineal tear or severe maternal soft tissue trauma (Fig. 3.5).

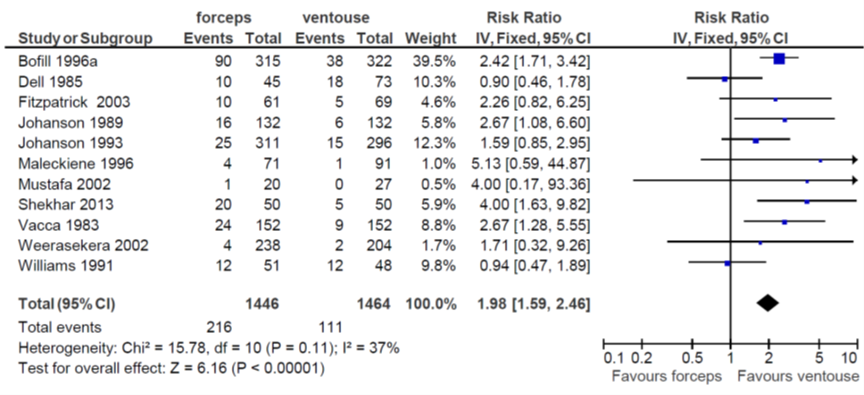

The pooled RR (95% CI) for third- or fourth-degree perineal tear (with or without episiotomy) was reported by O’Mahony (2010) as 1.89 (1.51 to 2.37) favouring ventouse over forceps (heterogeneity (I2): 32%), and the RR (95% CI) reported by Shekhar (2013) for severe maternal soft tissue trauma (extension to fornix, 3rd degree perineal tear, cervical tear, paraurethral tear) was 4.00 (1.63 to 9.82) favouring ventouse over forceps. The combined pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.98 (1.59 to 2.46) (heterogeneity (I2): 37%).

Figure 3.5 Comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term; outcome third- or fourth-degree perineal tear or severe maternal soft tissue trauma. Adapted from O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure third or fourth degree perineal tear or severe maternal soft tissue trauma started high and was not downgraded.

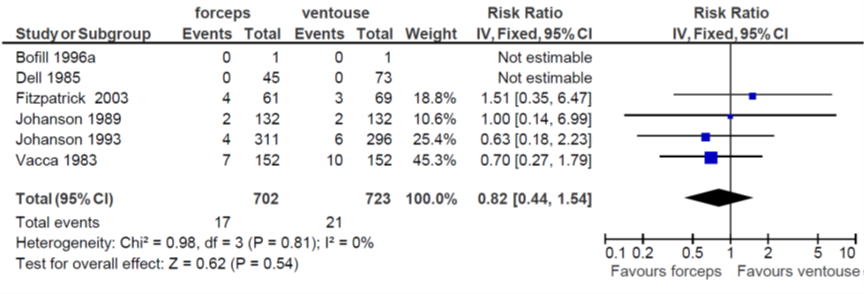

6. Low Apgar score at 5 minutes (Fig. 3.6). The pooled RR (95% CI) was 0.82 (0.44 to 1.54) favouring forceps over ventouse (heterogeneity (I2): 0%) (O’Mahony 2010).

Figure 3.6 Comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term; outcome low Apgar score at 5 minutes. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure low Apgar score at 5 minutes was downgraded by 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision) since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions.

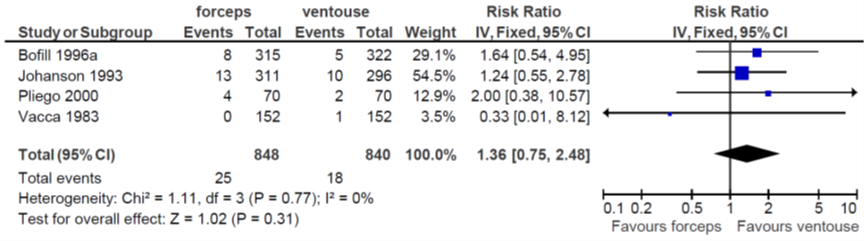

7. Scalp injury (Fig. 3.7). The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.36 (0.75 to 2.48) favouring ventouse over forceps (heterogeneity (I2): 0%) (O’Mahony 2010

Figure 3.7 Comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term; outcome scalp injury. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure scalp injury was downgraded by 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision)since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions.

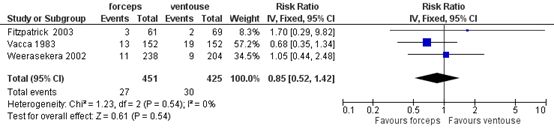

8. Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (Fig. 3.8). O’Mahony (2010) reported a pooled RR (95% CI) of 0.85 (0.52 to 1.42) favouring forceps over ventouse (heterogeneity (I2): 0%).

Figure 3.8 Comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse at term; outcome admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure admission to NICU was downgraded by 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision) since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions.

Results 3a2: soft versus rigid cup ventouse at term

This comparison was only addressed by O’Mahony (2010).

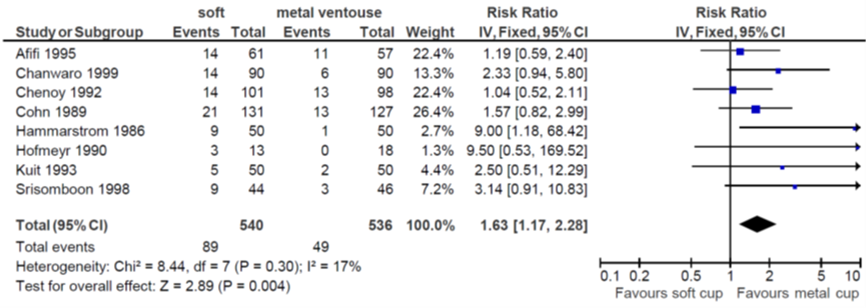

1. Failed delivery with allocated instrument (Fig. 3.9). The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.63 (1.17 to 2.28) favouring metal cup over soft cup (heterogeneity (I2): 17%).

Figure 3.9 Comparison soft versus metal cup ventouse at term; outcome failed delivery with allocated instrument. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure failed delivery with allocated instrument started high and was downgraded by 1 level because of number of patients (imprecision) since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference.

2. Neonatal death. O’Mahony (2010) reported an RR (95% CI) of 1.25 (95% CI 0.08 to 19.22) favouring metal cup over soft cup based on one RCT (n=72) (Lee, 1996).

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal death started high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of number of included patients (imprecision) since there was only 1 study reporting this outcome, the number of events was very small (1/32 vs 1/40), and the 95% CI exceeded the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions.

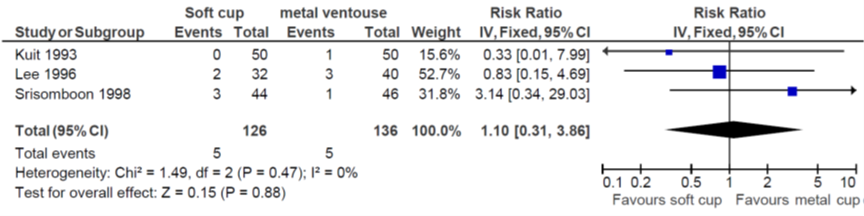

3. Caesarean section (Fig. 3.10). The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.10 (0.31 to 3.86) favouring metal cup over soft cup (heterogeneity (I2): 0% (O’Mahony, 2010).

Figure 3.10 Comparison soft versus metal cup ventouse at term; outcome Caesarean Section. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure caesarean section started high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low, 1 level because of inconsistency and 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision) since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions.

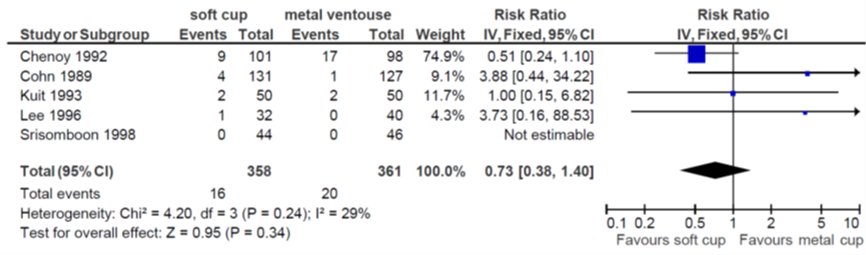

4. Low Apgar score at 5 minutes (< 7 or as defined by trial authors)(Fig. 3.11). Pooled RR (95% CI) was 0.73 (0.38 to 1.40) (heterogeneity 29%) in favour of the soft cup (O’Mahoney, 2010).

Figure 3.11 Comparison soft versus metal cup ventouse at term; outcome low Apgar Score at 5 minutes. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure low Apgar score at 5 minutes started high and was downgraded by 3 levels, 1 level because of inconsistency and 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision) since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions.

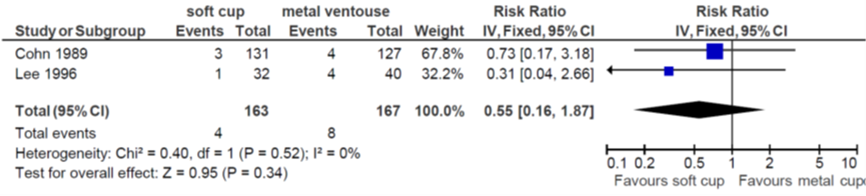

5. Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (Fig. 3.12). O’Mahony (2010) reported a pooled RR (95% CI) of 0.55 (0.16 to 1.87) favouring soft cup over metal cup (heterogeneity (I2): 0%).

Figure 3.12 Comparison soft versus metal cup ventouse at term; outcome admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure admission to NICU started high and was downgraded by 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision) since the 95% CI exceeds the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions.

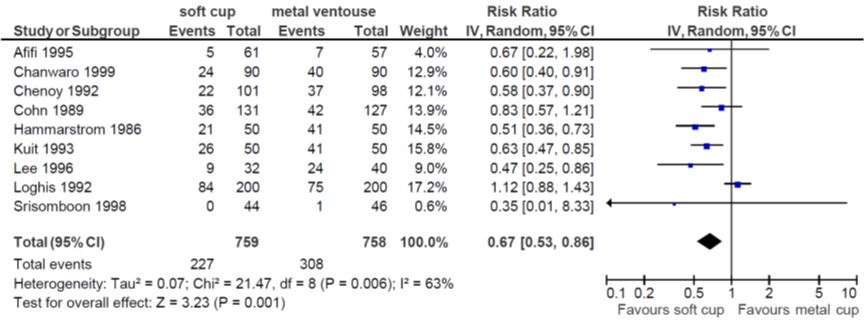

6. Scalp injury (Fig. 3.13). O’Mahony (2010) reported a pooled RR (95% CI) of 0.67 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.86) favouring soft cup over metal cup (heterogeneity (I2): 63%). From the information on primary studies presented in the SR by O’Mahoney et al. the cause of heterogeneity is not clear.

Figure 3.13 Comparison soft versus metal cup ventouse at term; outcome scalp injury. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure scalp injury/scalp abrasion started high and was downgraded by 1 level because of conflicting results (inconsistency) (I2 = 63%).

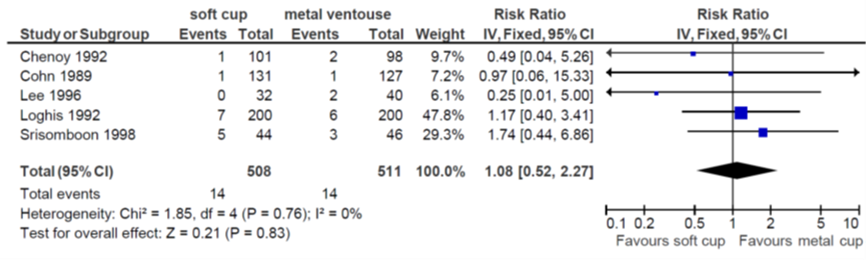

7. Third- or fourth-degree perineal tear (with or without episiotomy)(Fig 3.14). O’Mahony (2010) reported a pooled RR (95% CI) of 1.08 (0.52 to 2.27) favouring metal cup over soft cup (heterogeneity (I2): 0%).

Figure 3.14 Comparison soft versus metal cup ventouse at term; outcome third- or fourth-degree perineal tear. From O’Mahoney et al. 2010.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure third or fourth degree perineal tear was downgraded by 2 levels because of number of included patients (imprecision) since the 95% CI exceeded the minimal clinically relevant difference in both directions.

Description of studies

For the comparison any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse (3b1) one observational study was included (Corcoran, 2013).

Corcoran (2013) is a retrospective observational study, that reviewed 64 cases of preterm instrumental vaginal deliveries. The study was conducted in a stand-alone maternity unit of approximately 9000 deliveries per year in Ireland. The charts of mothers and babies delivered by forceps or vacuum at < 35 weeks gestation from 1999 to 2008 were reviewed. Singleton and twin pregnancies < 35 weeks’ gestation at delivery were included. Vacuum deliveries included both metal cups, and kiwi cups (n=22), and Neville Barnes forceps (n=42). Deliveries of babies with major congenital, and chromosomal anomalies were excluded.

For the second comparison, type of vacuum (3b2), no studies were included.

Results 3b1: any type of forceps versus any type of ventouse preterm

1. Delivery with the allocated instrument. Corcoran (2013) reported two infants for which a failed vacuum delivery was converted to a forceps delivery (2/22).

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure delivery with allocated instrument was downgraded by 2 levels because study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision) to very low.

2. Neonatal death. Corcoran (2013) reported neonatal deaths in the first 28 days of life. Corcoran reported one case of neonatal death (5%) in the ventouse group and 2 in the forceps group (5%). None of these deaths was related to the mode of delivery.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal death started low and was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision) to very low.

3. Low Apgar score at 5 minutes (< 7 or as defined by trial authors). Corcoran (2013) reported Apgar scores < 3 at 5 minutes. In the forceps group no cases of Apgar scores < 3 at 5 minutes were reported (0/42) and one in the ventouse group (1/20).

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure low Apgar score at 5 minutes was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision) to very low.

4. Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Corcoran (2013) reported 90% (18/20) NICU admissions in the group ventouse delivery, and 100% (42/42) admissions in the group forceps delivery.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure admission to NICU started low and was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision) to very low.

5. Intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH). Corcoran (2013) reported intraventricular haemorrhage. In the forceps group (24 + 0 to 30 + 6) all eight infants had cranial ultrasound scanning. Four (50 %) of these were found to have an IVH. In the other forceps group (31 + 0 to 34 + 6), 12 of the 34 infants had cranial ultrasound scanning and two (6 %) were found to have IVH. No IVH was recorded in the vacuum delivery group; however, only three of these infants underwent cranial ultrasound scanning.

Level of evidence

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure intraventricular hemorrhage started low and was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision) to very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

P: woman in labour with an indication for instrumental vaginal delivery at term (3a1)/ preterm (3b1);

I: forceps;

C: ventouse;

O: maternal: successful vaginal delivery with the allocated instrument, caesarean section, perineal trauma, mother-child attachment, breastfeeding, patient satisfaction, maternal post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSS).

neonatal: cephalic lacerations, cephalic hematoma, intracranial haematoma, perinatal death, NICU admission, infections, Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

P: woman in labour with an indication for ventouse delivery at term (3a2)/ preterm (3b2);

I: rigid cup;

C: soft cup;

O: maternal: successful vaginal delivery with the allocated instrument, caesarean section, perineal trauma, mother-child attachment, breastfeeding, patient satisfaction, maternal post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSS).

neonatal: cephalic lacerations, cephalic hematoma, intracranial haematoma, perinatal death, NICU admission, infections, Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered successful vaginal delivery with the allocated instrument, caesarean section and perinatal death as a crucial outcome measures for decision making. Perineal trauma, cephalic lacerations, cephalic hematoma, intracranial haematoma, NICU admission, infections, Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes, mother-child attachment, breastfeeding, patient satisfaction and PTSS were considered as important outcome measures for decision making.

Preterm birth was defined as birth before 37 weeks of gestation. A priori, the working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. The handheld ventouse cup was not analysed separately from the metal cup.

For the critical outcome measures the working group used the following RR values as minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- Perinatal death: any difference;

- Successful vaginal delivery with the allocated instrument: RR < 0.95 or > 1.05;

- Caesarean section: RR < 0.95 or > 1.05.

For the other outcome measures the working group used the GRADE-recommendation of RR < 0.80 or > 1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until April 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 558 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: Systematic reviews or RCTs in which a comparison was made of maternal and neonatal outcomes between either ventouse versus forceps or different types of ventouse cups applied in women in labour in need of an instrumental vaginal delivery. 75 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract. After reading the full text, 72 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three studies were included, two for question 3a (type of instrument for term assisted vaginal delivery) and one for question 3b (type of instrument for preterm assisted vaginal delivery).

Results 3a. Type of instrument for assisted vaginal term delivery

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature. One of these reported term labour as one of the inclusion criteria; in the other study, a systematic review, no clear in- or exclusion criteria were reported regarding gestational age. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- O'Mahony, F., Hofmeyr, G. J., & Menon, V. (2010). Choice of instruments for assisted vaginaldelivery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (11).

- Shekhar, S., Rana, N., & Jaswal, R. S. (2013). A prospective randomized study comparing maternal and fetal effects of forceps delivery and vacuum extraction. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India, 63(2), 116-119.

- Corcoran, S., Daly, N., Eogan, M., Holohan, M., Clarke, T., & Geary, M. (2013). How safe is preterm operative vaginal delivery and which is the instrument of choice?. Journal of perinatal medicine, 41(1), 57-60.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

O’Mahony, 2010

study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to May 2010

B: Attilakos, 2005 C: Bofill, 1996 D: Carmody, 1986 E: Chanwaro, 1999 F: Chenoy, 1992 G: Cohn, 1998 H: Dell, 1985 I: Fall, 1986 J: Fitzpatrick, 2003 K: Groom 2006 L: Hammarstrom 1986 M: Hebertson, 1985 N: Hofmeyr 1990 O: Johanson 1989 P: Johanson, 1993 Q: Kuit 1993 R: Lasbrey, 1964 S: Lee, 1996 T: Lim, 1997 U: Loghis 1992 V: Maleckiene, 1996 W: Mustafa, 2002 X: Nor Azlin, 2008 Z: Roshan, 2005 AA: Srisomboon, 1998 AB: Thiery, 1987 AC: Vacca, 1983 AD: Warwick 1993 AE: Weerasekera, 2002 AF: Williams, 1991

Study design: all RCTs

Setting and Country: A: single setting SaudiArabia B: two centres, Bristol C: single centre, Mississippi D: St Mary’s Portsmouth E:? F: single centre, Kathmandu G: 4 centres in UK H: single centre Louisiana I: single centre, Sweden J: National Maternity Hospital, Dublin K: Queen Charlotte & Chelsea, London L: single centre, Stockholm M: single centre, Salt Lake City N: 3 centres in Johannesburg O: 2 centres, UK P: 4 centres, UK Q: 2 centres, Netherlands R: single centre, South Africa S: single centre, Kuala Lumpur T: single centre, the Hague U: single centre, Athens V: Lithuania W: single centre, Karachi X:? Z: single centre, Russia AA: single centre, Thailand AB: single centre, Ghent AC: St Mary’s Portsmouth AD: 2 centres UK AE: single centre, Sri Lanka AF: single centre, Florida

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported in SR for individual included studies; SR funded by: University Hospital of North Staffordshire, UK, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, HRP-UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World bank special programme in human reproduction

|

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs Women in second stage of labour due for instrumental vaginal delivery

Exclusion criteria SR: any design other than RCT

32 studies included

N A: 57 I, 61 C B: 100 I, 100 C C: 322 I, 315 C D: 60 I, 63 C E: 90 I, 90 C F: 98 I, 101 C G: 137 I, 131 C H: 73 I, 45 C I: 20 I, 16 C J: 69 I, 61 C K: 198 I, 206 C L: 50 I, 50 C M: 29 I, 22 C, 26 left blade padded, 28 right blade padded N: 18 I, 13 C O: 135 I, 135 C P: 296 I, 311 C Q: 50 I, 50 C R: 121 I, 131 C S: 40 I, 32 C T: 47 I, 47 C U: 200 I, 200 C V: 91 I, 71 C W: 27 I, 23 C X: 79 I, 85 C Z: 51 I, 45 C AA: 46 I, 44 C AB: 210 I, 200 C AC: 152 I, 152 C AD: 50 I, 55 C AE: 204 I, 238 C AF: 51 I, 48 C

|

Describe intervention:

A: metal cup B: Kiwi (handheld) C: M-cup vacuum D: new generation metal cup E: metal cup F: metal cup G: metal cup H: soft cup vacuum I: vacuum J: vacuum K: conventional cup L: Malmstrom cup M: conventional forceps N: rigid cup O: silicone cup P: Silicone cup or Bird ventouse Q: rigid cup R: Malmstrom S: metal cup T: rapid application of vacuum under Malmstrom U: metal cup V: vacuum extractor W: Bird’s cup

X: Malmstrom metal cup Z: regular forceps AA: metal cup AB: Malmstrom AC: anterior and posterior cup Bird vacuum extractor cups AD: silicone (soft) AE: vacuum AF: polyethylene vacuum cup

|

Describe control:

A: silicone cup B: conventional vacuum cup C: forceps D: original Bird cup

E: Silastic cup F: silicone cup G: silicone cup H: forceps I: forceps J: forceps K: Kiwi cup L: silastic cup M: padded forceps N: soft cup O: forceps P: Neville Barnes or Kiellands forceps Q: silastic cup R: forceps S: silicone cup T: stepwise application of vacuum under O’Neil U: silicone cup V: Kielland forceps W: Wrigley’s or Neville-Barnes forceps X: Kiwi omnicup

Z: soft forceps AA: soft cup AB: O’Neil AC: Haig Ferguson’s and Kielland’s forceps

AD: Santoprene (soft) AE: forceps AF: forceps

|

End-point of follow-up:

not reported in SR

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control)

Not reported in SR

|

COMPARISON: ANY TYPE OF FORCEPS VERSUS ANY TYPE OF VENTOUSE

Outcome measure-1 Defined as failed delivery with allocated instrument

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): C: 1.42 (0.79,2.55) H: 0.35 (0.11, 1,14) O: 0.37 (0.21, 0.67) P: 0.68 (0.44, 1.03) W: 1.35 (0.09, 20.31) AC: 0.79 (0.48, 1.31) AE: 0.49 (0.27, 0.88) Pooled effect (random effects model: 0.65 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.94) favouring forceps over ventouse Heterogeneity (I2): 54%

Outcome measure-2 Defined as any neonatal injury (Outcome 3)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): J: 2.26 (0.21, 24.34) O: 3.00 (0.12, 72.98) P: 8.57 (0.46, 158.44) W: 0.54 (0.12, 2.51) AD: 0.33 (0.001, 8.12) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.16 (95% CI 0.41 to 3.30) favouring ventouse over forceps Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-3 Defined as Caesarean section (outcome 4)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): O: 0.50 (0.05, 5.45) P: 1.90 (0.72, 5.01) W: 1.35, 0.09, 20.31) AC: 2.00 (0.83, 4.82) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.76 (95% CI 0.95 to 3.23) favouring ventouse over forceps Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-4 Defined as third- or fourth-degree perineal tear (with or without episiotomy)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): C: 2.42 (1.71, 3.42) H: 0.90 (0.46, 1.78) J: 2.26 (0.82, 6.25) O: 2.67 (1.08, 6.60) P: 1.59 (1.59 (0.85, 2.95) V: 5.13 (0.59, 44.87) W: 4.00 (0.17, 93.36) AC: 2.67 (1.28, 2.55) AE: 1.71 (0.32, 9.26) AF: 0.94 (0.47, 1.89) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.89 (95% CI 1.51 to 2.37) favouring ventouse over forceps Heterogeneity (I2): 32%

Outcome measure-5 Defined as Flatus incontinence/altered continence (outcome 17)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): J: 1.77 (1.19, 2.62) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.77 (95% CI 1.19 to 2.62) favouring ventouse over forceps Heterogeneity (I2): not applicable

Outcome measure-6 Defined as low Apgar score at 5 minutes (<7 or as defined by trial authors) (outcome 21)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): C: not estimable H: not estimable J: 1.51 (0.35, 6.47) O: 1.00 (0.14, 6.99) P: 0.63 (0.18, 2.23) AC: 0.70 (0.27, 1.79) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.82 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.54) favouring forceps over ventouse Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-7 Defined as scalp injury (outcome 23)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): C: 1.64 (0.54, 4.95) P: 1.24 (055, 2.78) Y: 2.00 (0.38, 10.57) AC: 0.33 (0.01, 8,12) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.36 (95% CI 0.75 to 2.48) favouring ventouse over forceps Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-8 Defined as Facial injury (outcome 24)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): O: 9.00 (0.49, 165.52) P: 4.76 (0.56, 40.49) AC: 3.00 (0.12, 73.07) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 5.10 (95% CI 1.12 to 23.25) favouring ventouse Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-9 Defined as intracranial injury (outcome 25)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): H: 4.83 (0.20, 1115.98) Y: not estimable Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 4.83 (95% CI 0.20 to 115.98) favouring ventouse Heterogeneity (I2): not applicable

Outcome measure-10 Defined as cephalhaematoma (outcome 26)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): C: 0.52 (0.31, 0.89) H: 1.47 (0.68, 3.19) P: 0.28 (0.13, 0.61) V: 2.35 (0.91, 6.05) W: 4.00 (0.17, 93.36) Y: 0.33 (0.07, 1.60) AC: 0.57 (0.25, 1.32) AE: 0.14 (0.03, 0.63) AF: 0.67 (0.23, 1.98) Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.64 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.11) favouring forceps over ventouse Heterogeneity (I2): 65%

Outcome measure-11 Defined as neonatal death (outcome 35)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): P: 0.95 (0.06, 15.15) R: 2.77 (0.29, 26.28) W: 4.00 (0.17, 93.36) AE: 0.86 (0.05, 13.62) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.75 (95% CI 0.46 to 6.68) favouring ventouse Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-12 Defined as admission to neonatal intensive care unit (outcome 48)

Effect measure: RR, (95% CI): J: 1.70 (0.29, 9.82) AC: 0.68 (0.35, 1.34) AE: 1.05 (0.44, 2.48) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.85 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.42) favouring forceps over ventouse Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

COMPARISON: SOFT CUP (ANTERIOR) VERSUS METAL CUP

Outcome measure-13 Defined as failed delivery with allocated instrument (outcome 1)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: 1.19 (0.59, 2.40) E: 2.33 (0.94, 5.80) F: 1.04 (0.52, 2.11) G: 1.57 (0.82, 2.99) L: 9.00 (1.18, 68.42) N: 9.50 (0.53, 169.52) Q: 2.50 (0.51, 12.29) AA: 3.14 (0.91, 10.83) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.63 (95% CI 1.17 to 2.28) favouring metal cup over soft cup Heterogeneity (I2): 17%

Outcome measure-14 Defined as caesarean section (outcome 4)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): Q: 0.33 (0.01, 7.99) S: 0.83 (0.15, 4.69) AA: 3.14 (0.34, 29.03) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.10 (95% CI 0.31 to 3.86) favouring metal cup over soft cup Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-15 Defined as cephalhaematoma (outcome 5)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: 0.23 (0.03, 2.03) G: 0.76 (0.43, 1.34) N: 0.45 (0.02, 10.30) Q: 0.33 (0.12, 0.96) S: 0.83 (0.26, 2.70) AA: 0.21 (0.01, 4.23) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.61 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.95) favouring soft cup over metal cup Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-16 Defined as low Apgar score at 5 minutes (<7 or as defined by trial authors)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): F: 0.51 (0.24, 1.10) G: 3.88 (0.44, 34.22) Q: 1.00 (0.15, 6.82) S: 3.73 (0.16, 88.53) AA: not estimable Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.73 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.40) favouring soft cup over metal cup Heterogeneity (I2): 29%

Outcome measure-17 Defined as admission to neonatal intensive care unit (outcome 9)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): G: 0.73 (0.17, 3.18) S: 0.31 (0.04, 2.66) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.55 (95% CI 0.16 to 1.87) favouring soft cup over metal cup Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-18 Defined as scalp injury (outcome 13)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: 0.67 (0.22, 1.98) E: 0.60 (0.40, 0.91) F: 0.58 (0.37, 0.90) G: 0.83 (0.57, 1.21) L: 0.51 (0.36, 0.73) Q: 0.63 (0.47, 0.85) S: 0.47 (0.25, 0.86) U: 1.12 (0.88, 1.43) AA: 0.35 (0.01, 8.33) Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.67 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.86) favouring soft cup over metal cup Heterogeneity (I2): 63%

Outcome measure-19 Defined as intracranial injury (outcome 14)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): A: 0.31 (0.01, 7.50) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.31 (95% CI 0.01 to 7.50) favouring soft cup over metal cup Heterogeneity (I2): not applicable

Outcome measure-20 Defined as third- or fourth-degree perineal tear (with or without episiotomy)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): F: 0.49 (0.04, 5.26) G: 0.97 (0.06, 15.33) S: 0.25 (0.01, 5.00) U: 1.17 (0.40, 3.41) AA: 1.74 (0.44, 6.86) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.08 (95% CI 0.52 to 2.27) favouring metal cup over soft cup Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-21 Defined as (neonatal) death (outcome 23)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): S: 1.25 (0.08, 19.22) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1.25 (95% CI 0.08 to 19.22) favouring metal cup over soft cup Heterogeneity (I2): not applicable. |

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained (subgroupanalysis) |

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Shekhar, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT Setting and country: India

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: - singleton - gestation ≥ 37 completed weeks - indication for instrumental assistance

Exclusion criteria: not reported N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Bird modification of the Malmstrom instrument

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Das variety of long curved forceps and Wrigley’s outlet forceps

|

Length of follow-up: immediately after delivery(?)

Loss-to-follow-up: none

Incomplete outcome data: none

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Delivery with the intended instrument 90% (I) versus 100% (C)

Severe maternal soft tissue trauma (extension to fornix, 3rd degree perineal tear, cervical tear, paraurethral tear) 10% (I) versus 40% (C), p<0.001

Cephalhaematoma 12% (I) versus 4% (C), p>0.05

facial palsy 0% (I) versus 2% (C) neonatal death 2% (I) versus 0% (C)

|

No effect estimates, only Chi2 tests

External validity? Study performed in India |

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Type of study: Observational, retrospective

Setting and country: Single center, standalone maternity unit, Ireland

Funding and conflicts of interest: ‘The authors stated that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.’ |

Inclusion criteria: The charts of mothers and babies delivered by forceps or vacuum at < 35 weeks gestation from 1999 to 2008, inclusive, were identified and systematically reviewed to extract the data. Singleton and twin pregnancies < 35 weeks’ gestation at delivery were included.

Exclusion criteria: Delivery of babies with major congenital and chromosomal anomalies were excluded.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 20 Control: 42

Important prognostic factors2: Not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? GA differed between the groups. To address gestational age as a confounding factor, the groups were stratified by gestational age. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Both metal cups and “kiwi” cups are in use in this unit.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Keillands forceps were not used in any of the deliveries, only Neville Barnes forceps. |

Length of follow-up: Not described

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: - Control: - Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: - Control: -

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality Total 1/20 (5%) Late (31 + 0 to 34 + 6) 1/20 (5%)

C: total 2/43 Early (24 + 0 to 30 + 6) 2/8 Late (31 + 0 to 34 + 6) 0/34

Occurrence of IVH I:0/20 C: 6/43 Early (24 + 0 to 30 + 6) 4/8 Late (31 + 0 to 34 + 6) 2/34

<3 at 5 min I: 1/20 C: 0/42

admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) I: 18/20 (90%) C: 42/42 (100%)

culture- proven sepsis (only recorded in database if sepsis occurred on or before day 3 of life)

I:0/20 C: 6/42 Early (24 + 0 to 30 + 6) 5/8 Late (31 + 0 to 34 + 6) 1/34

There were two infants for which a failed vacuum delivery was converted to a forceps delivery. |

N= 64 were included in the study. Of the cases reviewed, there were 11 twin pregnancies.

|

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

O’Mahony |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

not applicable |

yes |

yes |

unclear |

yes |

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Shekhar, 2013 |

box of serially numbered envelopes |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikey |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Corcoran, 2013 |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

likely |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Dall’Asta 2016 |

O different from PICO |

|

Huhn 2017 |

secondary analysis of RCT with different comparison |

|

Equy 2015 |

I and C different from PICO |

|

Johanson 2000a |

SR was updated by O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Johanson 2000b |

SR was updated by O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Johanson 2014 |

reprint of Johanson 1999 |

|

Khalid 2013 |

quasi-experimental |

|

Ismail 2008 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Senanayake 2006 |

comment, no original data |

|

Groom 2006 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Attilakos 2005 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Fitzpatrick 2003 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Mustafa 2002 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Johanson 1999 |

5-year follow-up of Johanson 1993, with >50% Loss to Follow-Up |

|

Srisomboon 1998 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Bofill 1997 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Lee 1996 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Bofill 1996 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Williams 1991 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Hofmeyr 1990 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Johanson 1989 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Cohn 1998 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Hammarstrom 1986 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Carmody 1986 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Dell 1985 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Vacca 1983a |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Vacca 1983b |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Weerasekera 2002 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Kuit 1993 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Johanson 1993 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Chenoy 1992 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Leng 2019 |

O different from PICO |

|

Hobson 2019 |

no original data reported |

|

Li 2017 |

etiologic SR; no direct comparison forceps - ventouse |

|

Watts 2013 |

etiologic SR; no direct comparison forceps - ventouse |

|

Kettle 2011 |

No addition to SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Kettle 2008 |

Earlier version of Kettle 2011 |

|

Johnson 2007 |

no direct comparison forceps - ventouse |

|

SOG Canada 2005 |

Guideline |

|

Vacca 2002 |

narrative review |

|

Hankins 1996 |

earlier than SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Usman 2019 |

O different from PICO |

|

García-Mejido, 2019 |

observational study |

|

Ramphul 2015 |

I and C different from PICO |

|

Hirsch 2014 |

I different from PICO |

|

Hehir 2013 |

observational study |

|

Waheed 2012 |

No full text available |

|

Lewis 2012 |

no distinction forceps - ventouse |

|

Mola 2010 |

I and C different from PICO |

|

Contag 2010 |

I and C different from PICO |

|

Backe 2008 |

I and C different from PICO |

|

Andrews 2006 |

no direct comparison forceps - ventouse |

|

Fitzpatrick 2004 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Gebremariam 1999 |

no direct comparison forceps - ventouse |

|

Foldspang 1999 |

no distinction forceps - ventouse |

|

Bofill 1997 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Sultan 1996 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Williams 1995 |

narrative review |

|

Vacca 1994 |

comment |

|

Thorp 1994 |

comment |

|

Warwick 1993 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Johanson 1993 |

I and C different from PICO |

|

Gleeson, 1992 |

observational study |

|

Johanson 1991 |

comment |

|

Thiery 1987 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Galvan, 1987 |

observational study |

|

Broekhuizen 1987 |

P different from PICO |

|

Fall 1986 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

Carmody 1986 |

in SR O’Mahony 2010 |

|

anonymous 1984 |

editorial |

|

Murphy 2011 |

I different from PICO |

|

Pelosi 1992 |

comment |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 23-01-2023

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 23-01-2023

Geldigheid en Onderhoud

|

Module |

Regiehouder(s) |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling |

|

Vaginale kunstverlossing |

NVOG |

2021 |

2026 |

Elke 5 jaar |

NVOG |

Nieuwe literatuur |

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS)

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangeren.

Werkgroep

- Dr. C.J. (Caroline) Bax, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVOG, voorzitter stuurgroep

- Dr. A.C.C. (Annemiek) Evers, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, NVOG, voorzitter stuurgroep tot 2019

- Dr. S.V. (Steven) Koenen, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis, NVOG, lid stuurgroep

- Dr. J.J. (Hans) Duvekot, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC, NVOG, lid stuurgroep

- Dr. M.T.M. (Maureen) Franssen, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, NVOG

- Dr. I.P.M. (Ingrid) Gaugler-Senden, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, NVOG

- M.A. (Marleen) van Driel, gastdocent en gezondheidsvoorlichter, Stichting Zelfbewustzwanger

- J.C. (Anne) Mooij, MSc, adviseur, Patientenfederatie Nederland

- A.M. (Sandra) Oomen van Dun, MSc, Physician assistant/klinisch verloskunde, werkzaam in het Elisabeth TweeSteden Ziekenhuis te Tilburg, KNOV

- H. (Hannah) de Klerk, MSc, zelfstandig waarnemend verloskundige, KNOV

- D.C. (Lianne) Zondag, MSc, beleidsmedewerker en eerstelijns verloskundige, KNOV

Meelezers

• Leden van de Otterlo-werkgroep (2019-2021)

Met ondersteuning van

• Dr. L. (Laura) Viester, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

• Dr. J.H. (Hanneke) van der Lee, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Actie |

|

Bax * (voorzitter stuurgroep 2020) |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog Amsterdam UMC 0,8 fte |

Allen niet betaald: Seceretaris werkgroep Otterlo NVOG Lid commissie kwaliteitsdocumenten NVOG Voorzitter stuurgroep 50 modules project geboortezorg NVOG Penningmeester werkgroep infectieziekten NVOG Lid kernteam NIPS consortium Vrijwillger hospice Xenia |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Evers * (voorzitter stuurgroep tot 2019) |

Gynaecoloog, UMCU |

"Lid van Ciekwal, voorzitter 50 geboortemodules NVOG Werkgroep multidisciplinaire richtlijn extreme vroeggeboorte, NVOG" |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Duvekot (lid stuurgroep) |

Gynaecoloog, Erasmus MC (full time) |

Directeur 'medisch advies en expertise bureau Duvekot', Ridderkerk, ZZP'er |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Koenen (lid stuurgroep) |

gynaecoloog, ETZ , Tilburg |

incidenteel juridische expertise (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Gaugler-Senden |

Gynaecoloog, vrijgevestigd 0,8fte geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Franssen |

Gynaecoloog-Perinatoloog UMCG |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Driel |

Gastdocent en gezondheidsvoorlichter, freelance |

Voorlichting geven op middelbaar onderwijs en MBO betreffende seksualiteit, bloed/stamcel/orgaan donatie en beroepsgerichte verdieping op de MBO kraam opleiding. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

De Klerk |

Zelfstandig waarnemend verloskundige, 1fte |

PhD-student Vumc afdeling Midwifery Science, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Oomen-van Dun |

Physician assistant/klinisch verloskunde Elisabeth TweeSteden Ziekenhuis te Tilburg, 0,83fte |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen actie. |

|

Mooij |

adviseur Patientenbelang, Patientenfederatie Nederland |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Zondag |

Beleidsmedewerker KNOV - 0,5fte Eerstelijns verloskundige – medepraktijk eigenaar verloskundige praktijk De Toekomst Geldermalsen 0,8fte |

Begeleider literatuurstudies en MSc thesis bij MSc Klinische Verloskunde aan de Hogeschool Rotterdam (betaald) Bestuurslid Netwerk Rivierenland (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door vertegenwoordigers van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Zelfbewustzwanger af te vaardigen in de werkgroep.

Implementatie

Implementatieplan

|

Aanbeveling |

Tijdspad voor implementatie: < 1 jaar, 1 tot 3 jaar of > 3 jaar |

Verwacht effect op kosten |

Randvoorwaarden voor implementatie (binnen aangegeven tijdspad) |

Mogelijke barrières voor implementatie1 |

Te ondernemen acties voor implementatie2 |

Verantwoordelijken voor acties3 |

Overige opmerkingen |

|

1e en 2e |

< 1 jaar |

Nihil |

Tijdig publiceren op richtlijnendatabase |

Geen, is conform het reeds geldende beleid |

Publicatie in de richtlijnendatabase |

NVOG |

|

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de geboortezorg. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen middels een invitational conference in november 2018. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten. Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten. Tevens is er een knelpunteninventarisatie gedaan in november 2018 middels een invitational conference.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

|

Medline (OVID)

1980 – april 2019

|

1 exp *Pregnancy/ or exp Delivery, Obstetric/ or (pregnan* or delivery or gestation* or labor* or labour* or birth*).ti,ab,kw. (1722954) 2 exp Vacuum Extraction, Obstetrical/ or ((vacuum adj3 (extract* or delivery)) or 'vacuum assisted').ti,ab,kw. (5470) 3 exp Obstetrical Forceps/ or (forceps or cup* or omnicup* or kiwi or malmstrom or ventouse).ti,ab,kw. (48794) 4 1 and 2 and 3 (1021) 5 limit 4 to (english language and yr="1980- 2019") (742) 6 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1851143) 7 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (390892) 8 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ (Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies) (3168474) 9 5 and 7 (37) 10 5 and 6 (139) 11 10 not 9 (118) 12 5 and 8 (392) 13 12 not 9 not 11 (319) 14 9 or 11 or 13 (474)

= 474 (470 uniek) |

558 |

|

Embase (Elsevier) |

('pregnancy'/exp/mj OR 'obstetric delivery'/exp OR pregnan*:ti,ab OR delivery:ti,ab OR gestation*:ti,ab OR labor*:ti,ab OR labour*:ti,ab OR birth*:ti,ab)

AND ('vacuum extraction'/exp/mj OR ((vacuum NEAR/3 (extract* OR delivery)):ti,ab) OR 'vacuum assisted':ti,ab)

AND ('obstetric forceps'/exp OR forceps:ti,ab OR cup*:ti,ab OR omnicup*:ti,ab OR kiwi:ti,ab OR malmstrom:ti,ab OR ventouse:ti,ab)

AND (english)/lim AND (1980-2019)/py NOT 'conference abstract':it

Gebruikte filters:

Systematische reviews: ('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp)

RCT’s: ('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it

Observationeel onderzoek: ‘major clinical study’/exp OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR ('prospective study'/de NOT 'randomized controlled trial'/de) OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (case:ab,ti AND ((control NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti)) OR (follow:ab,ti AND ((up NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti)) OR ((observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti)

= 452 (437 uniek) |