Loslaten van de cup

Uitgangsvraag

Wanneer moet de poging tot vaginale kunstverlossing worden gestaakt na tweemaal loslaten van de cup?

Aanbeveling

Bespreek met de barende het ingezette beleid na tweemaal loslaten van de cup.

Overwegingen

Six studies did not meet the PICO but were considered relevant for the subject. These studies evaluated number of pulls/pop-offs and associations between the number of pulls/pop-offs and neonatal and maternal outcomes (Table 1). When more pulls are needed or more often cup detachment occurs, both the maternal and neonatal outcomes are worse. More pulls more often leads to subarachnoid hematoma and neonatal birth trauma and in the mother to haemorragia postpartum and cervical or third/fourth degree tears.

|

Study |

Study design |

Origin of the data/population |

Objective |

Outcomes of interest for the PICO |

Results of interest for the PICO |

Comments |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ekéus, 2018 |

Retrospective cohort (n=596) |

Data on the management of vacuum deliveries at 6 different birth clinics in Sweden in 2013. |

To investigate the association between complicated vacuum extraction (VE) deliveries^ and neonatal complications. |

Neonate: Neonatal adverse outcome composite* Not reported Other variables: Number of pulls |

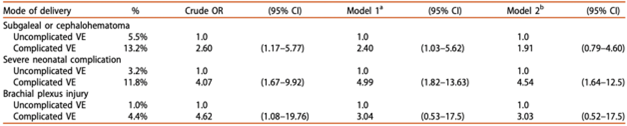

Neonate: Logistic regression for neonatal complications by complicated or uncomplicated VE copies from Ekéus (2018)

VE: vacuum extraction. a Adjusted for maternal height, parity, gestational age, birth weight and obstetric factors; fetal station, fetal presentation, indication for operative delivery and previous CS. b Same as in Model 1 adding fundal pressure.

Other variables: Number of pulls (n, %) 1-3: 361 (61) 4-6: 186 (31) >6: 36 (6)

No: 503 (84) Yes: 68 (11) Failed VE (n, %)

|

Metal cups and Omnicup device or soft cups were used.

Duration of the extraction describes the time in minutes from application of the cup until the infant's birth.

^ Extraction was defined as “complicated” if extraction time exceeded 15 min, and/or more than five pulls were used to deliver the infant, and/or more than one cup detachment occurred.

*Neonatal adverse outcome composite consisted of: Extracranial bleeding including cephalohematoma (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) Codes P12.0) and/or subgaleal hemorrhage (ICDP12.2), severe neonatal complication including; intracranial hemorrhage (ICD P10 and P52) and/or asphyxia (ICD P21) and/or convulsions of newborn (ICD P90) and/or encephalopathy (ICD P91) and/or low Apgar score (Apgar <7 at 5 min), and brachial plexus injury (ICD P14.0 and 14.1) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ghidini, 2017 |

Retrospective cohort |

Cohort of attempted vacuum-assisted vaginal deliveries at Inova Alexandria Hospital (USA) identified using ICD-9 codes between January 1, 2009 and August 31, 2012. |

To evaluate the association between the characteristics of vacuum use and the occurrence of head trauma and adverse neonatal outcomes. |

Neonate: Occurrence of head injuries (including major and minor complications*) Neonatal complications other than head injuries (APGAR score at 5 min and NICU admission)

Not reported |

Neonate: Occurrence of head injuries (median, IQR or number (%))) univariate analysis

No APGAR scores >7 at 5 min reported.

univariate analysis

Multivariate logistic regression (controlling for all variables with p <0.10 in univariate analysis): OR (95% CI) Head injuries Duration of vacuum (s): 1.004 (0.999. to 1.008) Adverse neonatal complications Number of pulls: 0.787 (0.400 to 1.545) |

Kiwi omnicup vacuum extractor (Clinical Innovations Inc., Murray, UT, USA) and Mystic II MitySoft Bell Cup (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT, USA) were used.

*Major complications: subgaleal hemorrhage, skull fracture, and intracranial hemorrhage. Minor complications: cephalohematomas, scalp laceration more extensive than simple abrasions. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kamijo, 2021 |

Retrospective cohort |

Data of pregnancies and neonates from January 2013 to May 2020 in hospital in Japan. 502 (out of 7321 = 6.9%) vacuum-assisted deliveries. 480 were eligible for inclusion in the study.

|

To determine the association between the number of pulls during vacuum-assisted deliver and neonatal and maternal complications. |

Neonate: NICU admission, low Apgar score (>7 at 5 minutes) Complications (severe perineal laceration, cerival laceration, transfusion and post partum hemorrhage ≥500ml) Other variables: Multivaliable logistic regression analysis for the association between the number of pulls and NICU admission |

Neonate: NICU admission (n, %) 3 pulls (n=52): 8 (15.4) ≥4 pulls (n=43): 12 (27.9) p= 0.03

low Apgar score (>7 at 5 minutes) (n, %) 3 pulls (n=52): 1 (1.9) ≥4 pulls (n=43): 0 (0.0) p= 0.63

Maternal: Severe perineal laceration (n, %) 3 pulls (n=52): 9 (17.3) ≥4 pulls (n=43): 9 (20.9) p= 0.28

3 pulls (n=52): 4 (7.7) ≥4 pulls (n=43): 2 (4.7) p= 0.34

Transfusion (n, %) 3 pulls (n=52): 1 (1.9) ≥4 pulls (n=43): 0 (0.0) p= 0.40

Post partum hemorrhage ≥500ml (n, %) 3 pulls (n=52): 32 (61.5) ≥4 pulls (n=43): 34 (79.1) p= 0.025

Other variables: Number of pulls NICU admission OR (95%CI) 1 Reference 2 1.45 (0.76 to 2.75) 3 1.39 (0.56 to 3.44) ≥4 3.33 (1.43 to 7.76) |

Pregnancies transitioning to cesarean section after a failed attempt at vacuum-assisted delivery were excluded.

Rigid plastic Kiwi Omni Cup extractor for all vacuum-assisted deliveries (Clinical Innovations Inc., Murray, UT, USA) were used. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Krispin, 2017 |

Retrospective cohort |

All women carrying a singleton, term (37–42 weeks) viable fetus that attempted attempting vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery in a single university afliated tertiary hospital, between January 1st 2012, and December 31th 2014. |

To determine the perinatal outcome associated with cup detachment during vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery. Comparison of neonatal outcomes of preganancies complicated by at least one cup detachment to the rest of the cohort in which the cup did not detatch. |

Neonate: Composite neonatal birth trauma* Composite neonatal outcome^

Composite maternal outcomea |

Neonate: Composite neonatal birth trauma and composite other neonatal outcome (n, %)

Logistic regression analysis: Cup detachment remained an independent risk factor for both subarachnoid hematoma (aOR = 45.44, 95% CI 6.42 to 321.62, p < 0.001) and neonatal birth trauma composite (aOR = 2.62, 95%CI 1.1 to 6.22, p = 0.03)

Composite maternal outcome (n, %)

Logistic regression analysisb: aOR = 0.583, 95% CI 0.325–1.045, p = 0.07. |

Metal cups and Kiwi cups were used. aComposite maternal outcome included any of post-partum hemorrhage, blood transfusion, and third/ fourth degree perineal tears. Women in the detachment group were characterized by (1) higher rates of prolonged second stage and maternal exhaustion as an indication for delivery (54.8 vs. 42% (total), p = 0.015]; (2) higher rates of fetal occiput posterior presentation (35.6 vs. 22.7%, p = 0.001) with no diference in head station; (3) lower rates of metal cup use (70.5 vs. 81.1%, p = 0.003); and (4) higher rates of VAVD failure (2.7 vs. 0.6%, p = 0.029). Other demographic and obstetric characteristics were similar between groups.

bLogistic regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders: birth weight, gestational age at delivery, primiparity, regional analgesia, VAVD indication, fetal head position, occiput posterior presentation, and cup type-cup. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Miller, 2019 |

Retrospective cohort |

Data analysis of a multicenter observational cohort. Women who delivered at 25 hospitals in the USA over a 3-year period were included. Women with a nonanomalous vertex singleton gestation at term who underwent an attempted operative vaginal deliveries (OVD) with a single instrument type (i.e., vacuum or forceps) were included in the analysis. |

To evaluate whether the number of vacuum pop-offs, the number of forceps pulls, or the duration of operative vaginal delivery (OVD) is associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. |

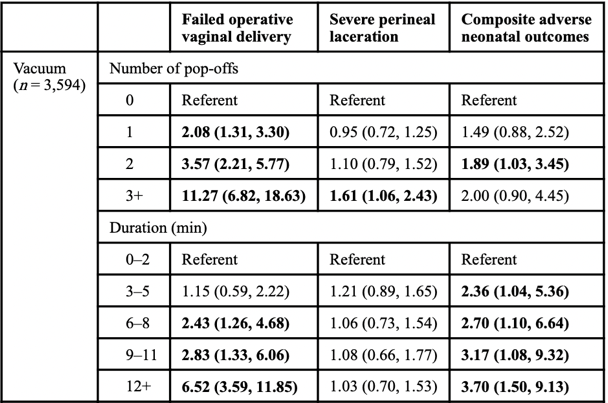

Neonate: Composite adverse neonatal outcome* Complications (severe perineal laceration (i.e. third or fourth degree) Other variables: Number of vacuum pop-offs Duration of OVD |

Neonate: Composite adverse neonatal outcome (n, %) 108 (3.0) Maternal: Severe perineal laceration ( (n, %)

Other variables: Number of vacuum pop-offs (n, %) (missing data for n=559 (15.6%)) Zero pop-offs: 1823 (60.1) 1 pop-off: 674 (22.2) 2 pop-offs: 372 (12.3) ≥3 pop-offs: 166 (5.5)

Duration of OVD (median, IQR) 4 minutes (2 to 7 minutes)

Failed OVD (n, %)

Multivariable analysis of duration of operative vaginal delivery for adverse outcomes copied from Miller (2019)

Data are reported as aOR (95% CI) after adjusting for indication for operative vaginal delivery, fetal station, and position, maternal age and race/ethnicity, chorioamnionitis, prior vaginal deliveries, prior cesareans, and maternal BMI. Emboldened text represents statistical significance. |

Women who delivered via a combination of forceps and vacuum were excluded.

The type of vacuum cups used was not reported.

The duration of OVD was defined as the time from first application of the vacuum or forceps to either time of vaginal birth or time of decision to convert to cesarean, divided into 3-minute intervals.

*Composite adverse neonatal outcome was defined to be present if any of the following occurred: brachial plexus injury, facial nerve palsy, clavicular fracture, skull fracture, other skeletal fracture, skin laceration, intracranial hemorrhage (including subgaleal), seizure requiring treatment, or neonatal death. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sakowicz, 2023 |

Retrospective cohort (n=1730) |

Women who underwent a trial of a vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery at a single tertiary care institution between October 2005 and June 2014 in the USA. |

To examine whether the number of pop-offs in a vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery was associated with adverse neonatal outcomes. |

Neonate: Severe composite adverse neonatal outcome* Not reported Other variables: Number of vacuum pop-offs

|

Neonate: Composite adverse neonatal outcome (n, %) 1 pop-off: 14 (5.8) 2 pop-offs: 7 (5.5) ≥3 pop-offs: 4 (5.8) p= 0.20 NICU admission (n, %) 1 pop-off: 55 (22.9) 2 pop-offs: 37 (28.9) ≥3 pop-offs: 19 (27.5) p= <0.001 Other variables: Number of vacuum pop-offs (n, %) Zero pop-offs: 1293 (74.7) 1 pop-off: 240 (13.9) 2 pop-offs: 128 (7.4) ≥3 pop-offs: 69 (4.0)

Cesarean delivery (n, %) 1 pop-off: 15 (6.3) 2 pop-offs: 15 (11.7) ≥3 pop-offs: 42 (60.9) p= <0.001

Multivariable analysis Number of pulls NICU admission adjusted OR (95%CI) 0 Reference 1 1.48 (1.01 to 2.16) 2 1.61 (0.98 to 2.65) ≥3 0.35 (0.08 to 1.61) |

Women who underwent sequential trials of both vacuum and forceps were excluded.

*Severe composite neonatal outcome included brachial plexus injury, intracranial hemorrhage, convulsions, and CNS depression. |

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is geen antwoord gevonden op de vraag of tot een sectio caesareamoet worden overgegaan of dat de vacuümextractie gecontinueerd moet worden nadat de cup tot twee keer heeft losgelaten. Het besluit om door te gaan met de vacuüm extractie danwel over te gaan tot een secundaire sectio ligt bij de parteur. Het besluit om tot een derde plaatsing van de cup over te gaan zal afhangen van de eerdere vordering en de stand van het caput. Tevens zal de foetale conditie hierbij een rol spelen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Een vaginale kunstverlossing waarbij er sprake is van loslaten van de cup kan ingrijpend zijn voor de barende. De motivatie van de parteur om het vacuüm opnieuw aan te leggen ofwel over te gaan tot een sectio moet met de barende besproken worden. Het is dan ook belangrijk dat er sprake is van individuele afstemming tijdens de bevalling.

Kosten (middelenbeslag) en duurzaamheid

Hier is uit de literatuur geen antwoord op te geven. Over het algemeen geldt dat een sectio meer zorgkosten met zich meebrengt en minder duurzaam is dan een vaginale kunstverlossing.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Op basis van de literatuur kan geen antwoord gegeven worden op de zoekvraag. In de praktijk zal de beslissing aan de parteur zijn of besloten wordt tot continueren van de vaginale kunstverlossing met het doel een succesvolle vaginale baring, danwel het verrichten van een sectio caesarea.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

In de literatuur werd geen antwoord op de uitgangsvraag gevonden. In de praktijk zal de parteur besluiten de vaginale kunstverlossing te continueren of over te gaan op een sectio caesarea, hierin wordt de voorkeur van de barende meegenomen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In current clinical practice, it is unclear when to halt or continue a vacuum extraction. It is relevant to gain information about consequences for both mother and child if, after two pop-offs, another attempt is made.

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

A systematic literature search was conducted but did not yield any hits that met the

selection criteria. No studies compared continuing vacuum assisted delivery to caesarean

delivery.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the effects of continuation of vacuum extraction after two pop-offs in comparison to cesarean delivery in women in labour undergoing assisted delivery?

| P (Patients): | Women in labour, indication for assisted delivery with disposable or metal cup (Malmström), no delivery after two pop-offs |

| I (Intervention): | Continuation of vacuum extraction/ vacuum assisted delivery |

| C (Control): | Caesarean delivery |

| O (Outcome measure): |

Maternal: Successful assisted vaginal birth, complications (postpartum bleeding, perineum trauma), satisfaction, post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSS), breast feeding, maternal bonding Neonatal: neonatal morbidity (Apgar score <7 after 5 minutes, sepsis, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)-admission, skin lesions, cephalohematoma) |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered successful vaginal delivery, neonatal morbidity, and complications (both maternal and neonatal) as critical outcome measures for decision making and satisfaction, post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSS), breast feeding and maternal bonding as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined a 10% difference for successful vaginal delivery and neonatal morbidity (RR < 0.9 or > 1.1) as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. For the other outcomes, a 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25) and 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes was taken as minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 13-11-2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 134 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- The study population had to meet the criteria as defined in the PICO

- The intervention had to meet the criteria as defined in the PICO

- Research type: systematic review, randomized-controlled trials and observational studies about pop-offs and pulls during vacuum assisted delivery

- Articles written in English or Dutch

No studies were selected based on title and abstract screening. All studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and no studies were included.

Results

None of the studies resulting from the literature search matched the PICO. Hence, no studies were included in the literature analysis and no evidence tables or risk of bias tables were constructed.

Referenties

- Ekéus C, Wrangsell K, Penttinen S, Åberg K. Neonatal complications among 596 infants delivered by vacuum extraction (in relation to characteristics of the extraction). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018 Sep;31(18):2402-2408. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1344631. Epub 2017 Jul 10. PMID: 28629251.

- Ghidini A, Stewart D, Pezzullo JC, Locatelli A. Neonatal complications in vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: are they associated with number of pulls, cup detachments, and duration of vacuum application? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Jan;295(1):67-73. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4206-7. Epub 2016 Sep 28. PMID: 27677283.

- Kamijo K, Shigemi D, Nakajima M, Kaszynski RH, Ohira S. Association between the number of pulls and adverse neonatal/maternal outcomes in vacuum-assisted delivery. J Perinat Med. 2021 Feb 19;49(5):583-589. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2020-0433. PMID: 33600672.

- Krispin E, Aviram A, Salman L, Chen R, Wiznitzer A, Gabbay-Benziv R. Cup detachment during vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery and birth outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Nov;296(5):877-883. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4507-5. Epub 2017 Sep 4. PMID: 28871450.

- Miller ES, Lai Y, Bailit J, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Varner MW, Thorp JM Jr, Leveno KJ, Caritis SN, Prasad M, Tita ATN, Saade GR, Sorokin Y, Rouse DJ, Blackwell SC, Tolosa JE; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network*. Duration of Operative Vaginal Delivery and Adverse Obstetric Outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2020 Apr;37(5):503-510. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683439. Epub 2019 Mar 20. PMID: 30895577; PMCID: PMC6754310.

- Sakowicz A, Zahalka SJ, Miller ES. The Association between the Number of Vacuum Pop-Offs and Adverse Neonatal Outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2023 Feb;40(3):274-278. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1728824. Epub 2021 May 3. PMID: 33940648.

Evidence tabellen

None of the studies resulting from the literature search were included in the literature analysis and hence no evidence tables or risk of bias tables were constructed.

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Cargill YM, MacKinnon CJ. No. 148-Guidelines for Operative Vaginal Birth. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Feb;40(2):e74-e80. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.11.003. PMID: 29447728. |

background article/guideline |

|

Ekéus C, Wrangsell K, Penttinen S, Åberg K. Neonatal complications among 596 infants delivered by vacuum extraction (in relation to characteristics of the extraction). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018 Sep;31(18):2402-2408. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1344631. Epub 2017 Jul 10. PMID: 28629251.

|

Wrong comparison (association study) |

|

Ghidini A, Stewart D, Pezzullo JC, Locatelli A. Neonatal complications in vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: are they associated with number of pulls, cup detachments, and duration of vacuum application? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Jan;295(1):67-73. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4206-7. Epub 2016 Sep 28. PMID: 27677283.

|

Wrong comparison (association study) |

|

Hobson, S., Cassell, K., Windrim, R., & Cargill, Y. (2019). No. 381-assisted vaginal birth. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 41(6), 870-882. |

background article/guideline |

|

Kamijo K, Shigemi D, Nakajima M, Kaszynski RH, Ohira S. Association between the number of pulls and adverse neonatal/maternal outcomes in vacuum-assisted delivery. J Perinat Med. 2021 Feb 19;49(5):583-589. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2020-0433. PMID: 33600672.

|

Wrong comparison (association study) |

|

Krispin E, Aviram A, Salman L, Chen R, Wiznitzer A, Gabbay-Benziv R. Cup detachment during vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery and birth outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Nov;296(5):877-883. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4507-5. Epub 2017 Sep 4. PMID: 28871450.

|

Wrong comparison (association study) |

|

Mastrolia SA, Wainstock T, Sheiner E, Landau D, Sergienko R, Walfisch A. Failed Vacuum and the Long-Term Neurological Impact on the Offspring. Am J Perinatol. 2017 Nov;34(13):1306-1311. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603507. Epub 2017 May 22. PMID: 28561146. |

No comparison (long term outcome cohort of children after failed vacuum procedure) |

|

Miller ES, Lai Y, Bailit J, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Varner MW, Thorp JM Jr, Leveno KJ, Caritis SN, Prasad M, Tita ATN, Saade GR, Sorokin Y, Rouse DJ, Blackwell SC, Tolosa JE; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network*. Duration of Operative Vaginal Delivery and Adverse Obstetric Outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2020 Apr;37(5):503-510. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683439. Epub 2019 Mar 20. PMID: 30895577; PMCID: PMC6754310.

|

Wrong comparison (association study) |

|

Mola GD, Amoa AB, Edilyong J. Factors associated with success or failure in trials of vacuum extraction. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 Feb;42(1):35-9. doi: 10.1111/j.0004-8666.2002.00041.x. PMID: 11930893. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Murphy DJ, Liebling RE, Patel R, Verity L, Swingler R. Cohort study of operative delivery in the second stage of labour and standard of obstetric care. BJOG. 2003 Jun;110(6):610-5. PMID: 12798481. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Pettersson KA, Westgren M, Blennow M, Ajne G. Association of traction force and adverse neonatal outcome in vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery: A prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Dec;99(12):1710-1716. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13952. Epub 2020 Sep 9. PMID: 32644188. |

Wrong comparison (association study) |

|

Polkowski M, Kuehnle E, Schippert C, Kundu S, Hillemanns P, Staboulidou I. Neonatal and Maternal Short-Term Outcome Parameters in Instrument-Assisted Vaginal Delivery Compared to Second Stage Cesarean Section in Labour: A Retrospective 11-Year Analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2018;83(1):90-98. doi: 10.1159/000458524. Epub 2017 Feb 22. PMID: 28222428. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Sakowicz A, Zahalka SJ, Miller ES. The Association between the Number of Vacuum Pop-Offs and Adverse Neonatal Outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2023 Feb;40(3):274-278. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1728824. Epub 2021 May 3. PMID: 33940648.

|

Wrong comparison (association study) |

|

Sugulle M, Halldórsdóttir E, Kvile J, Berntzen LSD, Jacobsen AF. Prospective assessment of vacuum deliveries from midpelvic station in a tertiary care university hospital: Frequency, failure rates, labor characteristics and maternal and neonatal complications. PLoS One. 2021 Nov 16;16(11):e0259926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259926. PMID: 34784382; PMCID: PMC8594828. |

Wrong comparison |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 28-08-2025

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 28-08-2025

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodules werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Sttichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg rondom een vaginale kunstverlossing.

Werkgroep

- Dr. J.J. (Hans) Duvekot, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Erasmus MC te Rotterdam, NVOG (voorzittter)

- Dr. A.B.C. (Audrey) Coumans, gynaeoloog, Maastricht UMC te Maastricht, NVOG

- Dr. I.P.M. (Ingrid) Gaugler-Senden, gynaecoloog, Jeroen Bosch ziekenhuis te 's-Hertogenbosch, NVOG

- Dr. E. (Etelka) Moll, gynaecoloog, OLVG te Amsterdam, NVOG

- Dr. H.P. (Hedwig) van de Nieuwenhof, gynaecoloog, Jeroen Bosch ziekenhuis te 's-Hertogenbosch, NVOG

- Dr. I. (Inge) de Milliano, gynaecoloog in opleiding, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVOG

- Drs. M. (Marjolein) Lansbergen-Mensink, physician assistant klinisch verloskundige, Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis te Delft, KNOV

- Drs. I. (Ilse) van Ee, adviseur patiëntenbelangen, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland te Utrecht, PFN

Klankbordgroep

- A.A. (Arend Adriaan) van der Wilt, Anesthesioloog, OLVG te Amsterdam, NVA

- R. (Rene) Kornelisse, kinderarts-neonatoloog, Erasmus MC – Sophia Ziekenhuis te Rotterdam, NVK

Met ondersteuning van

- dr. J.M. (Janneke) Schultink, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- dr. J. (Jana) Tuijtelaars, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medsich Specialisten

- dr. J.H. (Hanneke) van der Lee, senior-adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medsich Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Achternaam werkgroeplid |

Hoofdfunctie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Duvekot |

Erasmus MC, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog

|

Directeur Medisch Advies- en Expertise Bureau Duvekot |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Gaugler – Senden |

Hoofdfunctie: Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis |

Nevenfunctie: lid Werkgroep Otterlo |

Geen |

Geen |

|

de Milliano |

Gynaecoloog in opleiding Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Lansbergen – Mensink |

Vertegenwoordiger KNOV Verloskundige/ Physician Assistant, Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis Delft, 29 uur/week |

tekstredactie richtlijnen KNOV medisch redacteur website deverloskundige.nl Tekstschrijver Baby op Komst (incidenteel, betaald) Werkgroeplid NVOG Auditcommissie Maternale Sterfte en Morbiditeit (AMSM) (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

|

van Ee |

Patiëntenfederatie Nederland fulltime betaald, adviseur patiënten belang |

Ervaringsdeskundige patiënt vertegenwoordiger Psoriasis patiënten Nederland onbetaald Coördinator patienten participatie Psoriasispatiënten Nederland onbetaald - Lid centrale redactie Eupatie-fellow - mentor - Eupatie NL Onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Coumans |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, MUMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Moll |

Gynaecoloog OLVG |

SAVER cursus docent, onbetaald MOET cursus docent, onbetaald Commissie gynaecoloog en recht, schrijven van expertise rapporten, betaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

van de Nieuwenhof |

Gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis |

Secretaris WPMZ en pijler FMG |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Klankbordgroep |

||||

|

van der Wilt |

Anesthesioloog, OLVG 0,9 fte betaald. |

Promotieonderzoek MUMC, afdeling chirurgie, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Kornelisse |

kinderarts-neonatoloog |

Bestuurslid Perined |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse en een afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kopjes “Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)” per module). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Loslaten van de cup

|

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor vrouwen die in aanmerking komen voor een vaginale kunstverlossing. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen (KNOV), Nederlandse Verniging voor Anesthesiologie (NVA), Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kinderartsen (NVK), NVOG (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie) en PFNL (Patiëntenfederatie Nederland) via een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekstrategie

Search date: 13-11-2023

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#1 |

'vacuum extraction'/exp OR 'vacuum delivery'/exp OR 'kiwi omnicup'/exp OR 'obstetric vacuum delivery kit'/exp OR 'vacuum extractor'/de OR 'instrumental delivery'/de OR 'fetal extraction device'/de OR 'operative vaginal delivery'/exp OR (('obstetric delivery'/de OR 'vaginal delivery'/de OR 'obstetric procedure'/de) AND ('vacuum'/de OR vacuum*:ti,ab,kw OR ventouse*:ti,ab,kw)) OR (((vacuum OR ventouse) NEAR/3 (deliver* OR extract* OR evacuation* OR birth)):ti,ab,kw) OR kiwi:ti,ab,kw OR omnicup*:ti,ab,kw OR malmstrom:ti,ab,kw OR mityvac:ti,ab,kw |

11987 |

|

#2 |

'pop off*':ti,ab,kw OR 'pop up':ti,ab,kw OR 'pop ups':ti,ab,kw OR (((number OR many OR fewer OR dicontin*) NEAR/3 (pull* OR traction* OR vacuum* OR dislodg* OR detach*)):ti,ab,kw) OR (((cup OR vacuum* OR vavd OR traction*) NEAR/3 (dislodg* OR detach* OR pull* OR duration OR long)):ti,ab,kw) OR (((three OR 3 OR four OR 4) NEAR/3 (pull* OR traction* OR dislodg* OR detach*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((('operative vaginal' OR 'vaginal operative' OR 'assisted vaginal' OR 'vaginal assisted' OR 'vaginal instrumental' OR 'instrumental vaginal' OR vacuum OR vavd OR ovd) NEAR/3 duration):ti,ab,kw) OR (((incorrect OR correct OR adequate OR inadequate OR familiar* OR knowledge OR skill* OR training) NEAR/4 (vacuum OR procedure* OR technique OR instrument* OR equipment OR operator*)):ti,ab,kw) |

65634 |

|

#3 |

#1 AND #2 |

308 |

|

#4 |

#3 NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal'/exp OR 'animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

198 |

|

#5 |

#4 AND [1999-2024]/py |

166 |

|

#6 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

976749 |

|

#7 |

'clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti |

3911778 |

|

#8 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'comparative study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

7924097 |

|

#9 |

'case control study'/de OR 'comparative study'/exp OR 'control group'/de OR 'controlled study'/de OR 'controlled clinical trial'/de OR 'crossover procedure'/de OR 'double blind procedure'/de OR 'phase 2 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 3 clinical trial'/de OR 'phase 4 clinical trial'/de OR 'pretest posttest design'/de OR 'pretest posttest control group design'/de OR 'quasi experimental study'/de OR 'single blind procedure'/de OR 'triple blind procedure'/de OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 trial):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/6 (study OR studies)):ti,ab,kw) OR (((control OR controlled) NEAR/1 active):ti,ab,kw) OR 'open label*':ti,ab,kw OR (((double OR two OR three OR multi OR trial) NEAR/1 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((allocat* NEAR/10 (arm OR arms)):ti,ab,kw) OR placebo*:ti,ab,kw OR 'sham-control*':ti,ab,kw OR (((single OR double OR triple OR assessor) NEAR/1 (blind* OR masked)):ti,ab,kw) OR nonrandom*:ti,ab,kw OR 'non-random*':ti,ab,kw OR 'quasi-experiment*':ti,ab,kw OR crossover:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross over':ti,ab,kw OR 'parallel group*':ti,ab,kw OR 'factorial trial':ti,ab,kw OR ((phase NEAR/5 (study OR trial)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((case* NEAR/6 (matched OR control*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((match* NEAR/6 (pair OR pairs OR cohort* OR control* OR group* OR healthy OR age OR sex OR gender OR patient* OR subject* OR participant*)):ti,ab,kw) OR ((propensity NEAR/6 (scor* OR match*)):ti,ab,kw) OR versus:ti OR vs:ti OR compar*:ti OR ((compar* NEAR/1 study):ti,ab,kw) OR (('major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR 'observational study'/de OR 'cross-sectional study'/de OR 'multicenter study'/de OR 'correlational study'/de OR 'follow up'/de OR cohort*:ti,ab,kw OR 'follow up':ti,ab,kw OR followup:ti,ab,kw OR longitudinal*:ti,ab,kw OR prospective*:ti,ab,kw OR retrospective*:ti,ab,kw OR observational*:ti,ab,kw OR 'cross sectional*':ti,ab,kw OR cross?ectional*:ti,ab,kw OR multicent*:ti,ab,kw OR 'multi-cent*':ti,ab,kw OR consecutive*:ti,ab,kw) AND (group:ti,ab,kw OR groups:ti,ab,kw OR subgroup*:ti,ab,kw OR versus:ti,ab,kw OR vs:ti,ab,kw OR compar*:ti,ab,kw OR 'odds ratio*':ab OR 'relative odds':ab OR 'risk ratio*':ab OR 'relative risk*':ab OR 'rate ratio':ab OR aor:ab OR arr:ab OR rrr:ab OR ((('or' OR 'rr') NEAR/6 ci):ab))) |

14566050 |

|

#10 |

#5 AND #6 = SR |

12 |

|

#11 |

#5 AND #7 NOT #10 = RCT |

40 |

|

#12 |

#5 AND (#8 OR #9) NOT (#10 OR #11) = observationeel |

72 |

|

#13 |

#10 OR #11 OR #12 |

124 |