TENS en PTNS bij aandrangincontinentie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de effectiviteit van behandeling met TENS of PTNS bij vrouwen met aandrangincontinentie?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg TENS of PTNS als optie in de behandeling van vrouwen met aandrangincontinentie, indien blaastraining en/of medicamenteuze therapie niet werkzaam is of te veel bijwerkingen geeft.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In totaal zijn er 8 RCTs beschreven die een behandeling met TENS of PTNS bij vrouwen met aandrangincontinentie vergelijken met placebo of een medicamenteuze behandeling. Deze studies bevatten allen een kleine studie populatie en vergelijken verschillende behandelingen. Verder wordt er gebruik gemaakt van verschillende (niet gestandaardiseerde) vragenlijsten en worden uitkomstmaten niet op een eenduidige wijze gerapporteerd waardoor het poolen van uitkomsten slechts beperkt mogelijk is. Ook zijn de 95% betrouwbaarheidsintervallen zijn breed en worden er geen klinische relevante verschillen gevonden, met uitzondereling voor de vergelijking PTNS vs. placebo. In deze vergelijking wordt aangetoond dat er klinische relevant effecten zijn in het voordeel van de PTNS groep voor de uitkomstmaat incontinentiefrequentie en kwaliteit van leven. Dit wordt geradeerd met een lage bewijskracht. De overall bewijskracht is zeer laag door eerder benoemde beperkingen.

Verschillende systematische reviews die niet zijn meegenomen in de samenvatting van de literatuur (zie Table of excluded studies) concluderen dat goede kwalitatieve data over een behandeling met TENS of PTNS bij volwassenen met aandrangincontinentie ontbreekt (Booth, 2018; Levin, 2012; Moossdorff-Steinhauser, 2013; Wiboson, 2015). Deze reviews beschrijven gunstige resultaten voor TENS en/of PTNS met betrekking tot effectiviteit en veiligheid van de behandeling. Echter geven zij aan dat er meer onderzoek nodig is. De studies zijn niet meegenomen in de huidige samenvatting van de literatuur, omdat er geen onderscheid wordt gemaakt tussen mannen en vrouwen en/of omdat zij geen controle behandeling beschrijven.

Drie RCT’s zijn niet meegenomen in de huidige literatuursamenvatting, omdat zowel mannen als vrouwen werden geïncludeerd. Wel bevatten deze RCT’s belangrijke informatie voor in de overwegingen. Eén van deze RCT’s is de eerste studie die een behandeling met TENS vergelijkt met PTNS. Deze studie laat resultaten zien in lijn met de vergelijking in de huidige literatuursamenvatting. Beide behandelopties zijn effectief, zonder significante verschillen tussen de groepen (Ramirez, 2019). De twee andere RCTs vergelijken een behandeling met PTNS met sham of medicatie. De uitkomsten van deze onderzoeken zijn ook in lijn met de bevindingen van de literatuur samenvatting (Peters, 2009; 2010). De kwaliteit van deze studies is niet beoordeeld middels de eerder benoemde methodiek. Desondanks, benoemt de werkgroep dat met name de studies met een sham behandeling goed zijn opgezet en uitgevoerd. Deze studies geven objectieve informatie door gebruik van een speciale naald.

Een aanbeveling voor een behandeling met PTNS bij patiënten met aandrangincontinentie wordt gegeven in de huidige EAU-richtlijn (EAU guideline, 2021). Zij geven aan dat specialisten PTNS kunnen overwegen als optie voor verbetering van aandrangincontinentie bij vrouwen die geen baat hebben gehad bij anticholinergica (EAU guideline, 2021). Er is geen duidelijke voorkeursoptie en alle behandelopties dienen derhalve aan patiënten te worden voorgelegd. Patiënten die tevoren een urodynamisch onderzoek hebben ondergaan waarbij detrusor overactiviteit wordt gezien, hebben een lagere kans van slagen. Dit impliceert niet dat alle patiënten een urodynamisch onderzoek moeten gaan krijgen of dat PTNS bij deze groep niet kan worden geprobeerd.

Het behandelprotocol is niet hetzelfde in alle studies, één/twee/drie keer per week een behandeling gedurende 6 tot 12 weken. Er is behoefte aan een eenduidig protocol (Veeratterapillay, 2016). Dit punt wordt toegevoegd als kennislacune.

Er is geen bewijs gevonden voor het effect van een behandeling met TENS en/of PTNS op de langere termijn. Dit punt wordt toegevoegd als kennislacune.

Bij het opstellen van de PICO vraag is er geen vergelijking gemaakt met blaastraining. De werkgroep is zich hiervan bewust en zal deze vergelijking meenemen wanneer de huidige richtlijn een update krijgt. In de EAU guideline (2021) is er literatuuronderzoek gedaan naar de vergelijking tussen PTNS en blaastraining. Dit onderzoek leverde slechts één RCT over blaastraining versus PTNS/TENS plus blaastraining. Het onderzoek liet zien dat zowel PTNS als TENS effectiever waren dan alleen blaastraining (Sonmez, 2021). De resultaten zijn beschikbaar via uroweb.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Aandrangincontinentie neemt toe met de leeftijd. Om deze reden wordt het met name gezien bij oudere vrouwen. Een behandeling met TENS en/of PTNS is intensief. Frequente bezoeken voor behandeling zijn noodzakelijk. Dit kan een patiënt als belastend ervaren. TENS kan ook door patiënten zelf in de thuissituatie worden toegepast. PTNS kan na de eerste periode van +/- 12 weken eventueel naar minder frequente maintenance worden overgezet of d.m.v. TENS in thuissituatie. Momenteel lopen er vele studies ten aanzien van implantaten ten behoeve van TENS zodat patiënten thuis zelf kunnen stimuleren. De behandelaar dient de voor- en nadelen met de patiënt te bespreken, zodat er een afweging gemaakt kan worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De studie van Veeratterapillay (2016) beschrijft dat het lastig is om de kosten in kaart te brengen voor een behandeling met PTNS. De behandeling wordt namelijk in verschillende studies niet universeel uitgevoerd. Er zitten verschillen in duur en frequentie van de behandelingen. Door de genoemde verschillen en ook een ander vergoedingssysteem in Nederland is een duidelijke vertaalslag niet te maken. Voor de Nederlandse situatie bestaat een kennislacune ten aanzien van medicatie, tibialis stimulatie, sacrale neuromodulatie en Botuline toxine A injecties intravesicaal wat kosteneffectief is. Dit punt wordt toegevoegd als kennislacune.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

PTNS of TENS is over het algemeen reeds redelijk aanvaard en geïmplementeerd. De poliklinische setting en personele benodigdheden van PTNS maken het niet overal gemakkelijk te implementeren. In principe is verwijzing naar een centrum dat wel toepast mogelijk en zorg derhalve voor alle patiënten beschikbaar indien dit de wens is van de patiënt. Een langere reisafstand tot een centrum zal de belasting voor de patiënt wel doen toenemen. Bij maintenance PTNS zal dit tot een toenemende patiënt populatie leiden die therapie benodigd heeft. Mogelijk dat implantaten hier in de toekomst een rol bij kunnen gaan spelen om TENS of PTNS naar de thuissituatie te kunnen verplaatsen en daarmee de belasting in de praktijk/centra en belasting van de patiënt verminderen.

Overweeg PTNS of TENS als optie voor de behandeling van aandrangincontinentie bij vrouwen die geen baat hebben gehad bij anticholinergica/antimuscarinica. PTNS of TENS reduceert waarschijnlijk het aantal aandrangincontinentie episodes na 12 weken, vergeleken met placebo therapie. Er zijn geen ernstige bijwerkingen van PTNS of TENS bekend. Daarnaast is PTNS of TENS in Nederland over het algemeen reeds redelijk aanvaard en geïmplementeerd. Bovendien is de volgende stap in het behandeltraject - botulinetoxine - een meer invasieve behandeling. PTNS of TENS of een combinatie van beiden kan worden overwogen als maintenance therapie. Een nadeel van PTNS is de poliklinische setting en daarmee de reisafstand voor de patiënt, gezien het feit dat de behandelduur minimaal 12 weken bedraagt. Mogelijk dat implantaten voor tibialis stimulatie in de toekomst hier een rol in kunnen spelen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

PTNS wordt momenteel voorgeschreven bij vrouwen met een overactieve blaas en/of aandrangincontinentie. De behandeling bestaat uit een percutane TNS (tibial nerve stimulation) gedurende 30 min, 1x per week, voor een periode van 12 weken. Indien de behandeling effect heeft, wordt deze voortgezet, maar dan met steeds ruimere tijdsintervallen (PTNS maintenance) of met TENS (transcutane elektrostimulatie van de n. tibialis). De totale omvang van de patiëntenpopulatie neemt bij toepassing van maintenance PTNS toe en dit heeft ook impact op de (lange termijn) zorgkosten. Met TENS is een behandeling thuis mogelijk. De vraag is echter of deze behandeling net zo effectief is. Momenteel wordt research verricht naar implanteerbare TNS devices die bij de tibialis zenuw komen te liggen, waarna de zenuw vervolgens gestimuleerd kan worden.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. TENS versus PTNS

Urge incontinence episodes/ complications/ adverse events

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown what the effect of TENS, compared to PTNS in women with urge urinary incontinence is with respect to the outcome measures urge incontinence episodes, complications, and adverse events. These outcome measures were not studied in the included studies. |

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE |

Quality of life might not differ between women with urge urinary incontinence treated with TENS or PTNS.

Sources: (Ahmed, 2020) |

2. TENS versus pharmacological treatment

Urge incontinence episodes

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of TENS compared to pharmacological treatment is in women with urge incontinence on urge incontinence episodes.

Sources: (Souto, 2014) |

Complications/ adverse events

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown what the effect of TENS, compared to pharmacological treatment in women with urge incontinence is with respect to the outcome measures complications and adverse events. These outcome measures were not studied in the included studies. |

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE |

TENS therapy in women with urge incontinence might lead to higher health-related quality of life (overall score) and bladder severity symptoms (quality of life subdomain score) at 12 weeks, compared to pharmacological treatment.

Sources: (Ahmed, 2020; Souto, 2014) |

3. PTNS versus pharmacological treatment

Urge incontinence episodes

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment is in women with urge incontinence on urge incontinence episodes.

Sources: (Kizilyel, 2015; Manriquez, 2016; Preyer, 2015; Vecchioli, 2013; Vecchioli, 2018) |

Adverse events

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment is in women with urge incontinence on adverse events.

Sources: (Preyer, 2015) |

Complications

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown what the effect of PTNS, compared to pharmacological treatment in women with urge incontinence is with respect to the outcome measure complications. This outcome measure was not studied in the included studies. |

Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment is in women with urge incontinence on quality of life (i.e., health-related quality of life (overall score), bladder severity symptoms (quality of life subdomain score), global impression of improvement (quality of life subdomain), and incontinence impact (quality of life subdomain).

Sources: (Ahmed 2020; Kizilyel, 2015; Manriquez, 2016; Preyer, 2015; Vecchioli, 2013; Vecchioli, 2018) |

4. PTNS versus placebo

Urge incontinence episodes

|

Moderate GRADE |

PTNS therapy (i.e., 3 times a week for 12 weeks) in women with urge incontinence probably reduces urge incontinence episodes at 12 weeks, compared to placebo therapy.

Sources: (Finazzi, 2010) |

Complications/ adverse events

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown what the effect of PTNS, compared to placebo treatment in women with urge incontinence is with respect to the outcome measures complications and adverse events. These outcome measures were not studied in the included studies. |

Quality of life

|

Low GRADE |

PTNS therapy in women with urge incontinence might improve quality of life at 12 weeks, compared to placebo treatment.

Sources: (Finazzi, 2010) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

One RCT was performed in 60 postmenopausal women with an overactive bladder (Ahmed, 2020). These patients were randomized into three groups: 1) control group, receiving antimuscarinics daily for 12 weeks, 2) TENS group, receiving TENS 3 times/week for 12 weeks and medication (i.e., the same as control group), and 3) PTNS group, receiving PTNS 3 times/week for 12 weeks and medication (i.e., the same as control group). Outcomes between groups were presented for volume at first desire to void, maximum bladder capacity, bladder severity symptoms, and health related quality of life. The study is limited by the short duration of 12 weeks, the fact that all patients received medication, and only the patients were blinded to treatment.

One double blinded RCT was performed in 35 women with detrusor overactivity incontinence (Finazzi, 2010). These patients were randomized into two groups: 1) control group, receiving placebo (i.e., sham) treatment, and 2) PTNS group, receiving PTNS 3 times a week for 12 weeks. Outcomes between groups were presented for mean incontinence episodes/3days, mean voided volume (ml), and mean incontinence quality of life. In the intervention group 1 patient discontinued the intervention and 2 patients in de control group. The study is limited by the sample size and duration of 12 weeks.

One RCT was performed in 30 women with an overactive bladder (Kizilyel, 2015). These patients were randomized into three groups: 1) control group, receiving tolterodine 4mg daily for 12 weeks, 2) PTNS group, receiving PTNS once a week for 12 weeks, and 3) a combination of the control group and PTNS group. Data of the control group and PTNS group was used for the current summary of literature. Outcomes between groups were presented for urge incontinence, incontinence impact questionnaire, overactive bladder symptom score. Data of 6 patients was missing in the intervention group and of one patient in the control group, without reason. The study is limited by the sample size, duration of 12 weeks, and patients and/or physicians were not blinded to treatment allocation.

One RCT was performed in 70 women with an overactive bladder (Manriquez, 2016). These patients were randomized into two groups; 1) control group, receiving 10mg extended-release oxybutynin daily, and 2) PTNS group, receiving PTNS twice a week. The total study duration was 12 weeks. Outcomes between groups were presented for urge incontinence and OAB-questionnaire with 3 domains. Data was missing of 2 patients in the intervention group (due to moving and pregnancy), and of 4 patients in the control group (due to adverse events and one pregnancy). The study is limited by the duration of 12 weeks, and patients and/or physicians were not blinded to treatment allocation.

One RCT was performed in 36 women with an overactive bladder (Preyer, 2015). These patients were randomly assigned into two groups: 1) control group, receiving 2mg tolterodine twice a day, and 2) PTNS group, receiving PTNS once a week. The total study duration was 3 months. Outcomes between groups were presented for incontinence episodes in 24h, symptom impact on quality of life, and side effects. During the study, 2 patients were lost to follow-up in the intervention group (private reason, and SAE), and 2 in the control group. The study is limited by the relative low sample size, short study duration, and patients and assessors were not blinded to treatment.

One RCT was performed in 75 women with an overactive bladder (Souto, 2014). Patients were randomly allocated to a group: 1) control group, receiving 10mg oxybutynin daily, 2) TENS group, receiving TENS twice a week, and 3) a combination of the control and intervention group, all for 12 weeks. The total study duration was 24 weeks. In the current summary of literature, we select data of the control and intervention group. Outcomes between groups were presented for International Consultation on Incontinence-Short Form (ICIQ-SF), International Consultation on Incontinence-OAB (ICIQ-OAB) and symptom bother. Seven patients were lost to follow-up in the intervention group and 6 in the control group, all without reason. The study is limited by the lost to follow-up of several patients without reason, and the study was not blinded for assessors and/or patients.

One randomized controlled crossover study was performed in 40 women with overactive bladder syndrome (Vecchioli, 2013). Patients were randomly assigned to group A, receiving first 5mg solifenacin succinate for 40 days daily, second PTNS twice a week for 6 weeks after a washout period of 3 months; or group B, receiving first PTNS twice a week for 6 weeks, second receiving 5mg solifenacin daily for 40 days after a washout period of 3 months. We used only data of the first period (i.e., until wash out) in the current literature summary. Therefore, the total duration of interest will be 6 weeks. Outcomes between groups were presented for urge incontinence (voiding diary), overactive bladder questionnaire short form (OAB-SF), patient global impression of improvement questionnaire (PGI-I). Two patients in group A stopped solifenacin therapy due to adverse events during the first 6 weeks. No other patients were lost to follow-up during the first 6 weeks of interest. The study is limited by the low sample size, short duration, and the fact that patients and assessors were not blinded to treatment.

One RCT was performed in 105 women with overactive bladder syndrome (Vecchioli, 2018). Patients were randomly assigned to three groups: 1) control group, receiving 5mg solifenacin once a day for 12 weeks, 2) PTNS group, receiving PTNS once a week for 12 weeks, and 3) combination of control and PTNS group. In the current summary of literature, we will select data of the control and intervention group. The total study duration is 10 months. Outcomes between groups were presented for OABSS questionnaire (urge urinary incontinence), overactive bladder questionnaire short form (OAB-SF), patient global impression of improvement questionnaire (PGI-I). One patient in the intervention group was lost to follow-up without a reason, and 8 patients in the control group were lost to follow-up due to side effects. The study is limited by the fact that only the assessor was blinded to treatment, and patients not.

Results

To describe the results more homogenously, the included studies will be categorized into the following groups:

- TENS versus PTNS.

- TENS versus pharmacological treatment.

- PTNS versus pharmacological treatment.

- PTNS versus placebo.

Outcomes were pooled where possible.

1. TENS versus PTNS

1.1. Urge incontinence episodes

The outcome urge incontinence episodes was not reported for the comparison TENS versus PTNS.

1.2. Complications

The outcome complications was not reported for the comparison TENS versus PTNS.

1.3. Adverse events

The outcome adverse events was not reported for the comparison TENS versus PTNS.

1.4. Quality of life

One study reported the outcome measure quality of life (Ahmed (2020)) at week 12 (i.e., after intervention). It was defined as health related quality of life (HRQoL), reported as overall score (lower score is worse) and bladder severities symptoms (subdomain of overall score; higher score is worse). HRQoL was assessed via the OAB questionnaire short form.

The mean difference in overall HRQoL score was 2.58 (95%CI -3.01 to 8.17) between women with urge incontinence treated with TENS compared to PTNS.

The mean difference in bladder severity symptoms (subdomain of HRQoL) was -1.32 (95%CI -8.91 to 6.27) between women with urge incontinence treated with TENS compared to PTNS.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence (GRADE method) is determined per comparison and outcome measure and is based on results from RCTs and therefore starts at level “high”. Subsequently, the level of evidence was downgraded if there were relevant shortcomings in one of the several GRADE domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures urge incontinence, complications and adverse events could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures quality of life was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (95%CI of the mean difference includes no significant effect (mean difference=0) and no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5)).

2. TENS versus pharmacological treatment

2.1. Urge incontinence episodes

One study reported the outcome measure urge incontinence episodes over a study period of 6 months, the duration of the intervention was only 12 weeks (Souto (2014)). It was defined as percentage of patients presenting urinary incontinence episodes assessed via a voiding diary for 3 days, and as incontinence episodes assessed by the ICIQ-SF.

Urinary incontinence at 6 months was observed in 4/25 (14%) women treated with TENS compared to 9/25 (34%) women in the control group (RR 0.44 (95%CI 0.15 to 1.26)). The risk difference was -0.20 (95%CI -0.44 to 0.04) between groups.

Souto (2014) reported a reduction of episodes of incontinence in both groups after 12 weeks (i.e., directly after intervention). Although the intervention stopped, 12 weeks later an increase in incontinence episodes was shown in the control groups compared to the TENS group (mean scores at week 24; 13.3 verus 8.3). No effect size could be calculated since only means with minimum and maximum score were reported.

2.2. Complications

The outcome complications was not reported for the comparison TENS versus pharmacological treatment.

2.3. Adverse events

The outcome adverse events was not reported for the comparison TENS versus pharmacological treatment.

2.4. Quality of life

Two studies reported the outcome measure quality of life (Ahmed (2020); Souto (2014)). It was defined as health related quality of life (HRQoL; overall score (lower score is worse)) and bladder severities symptoms (subdomain score (higher score is worse)), assessed via OAB questionnaire short form in Ahmed (2020), and with ICIQ-OAB and symptom bother scores in Souto (2014). It was not possible to pool results as different questionnaires were used and because Souto (2014) did not reported means with standard deviations.

The mean difference in HRQoL was 10.69 (95%CI 6.29 to 15.09) between women treated with TENS compared to pharmacological treatment at 12 weeks.

The bladder severity symptoms (subdomain of HRQoL) decreased in the TENS group and the control group. The mean difference in bladder severity symptoms was 18.11 (95%CI 11.25 to 24.97) between women treated with TENS compared to pharmacological treatment at 12 weeks.

Souto (2014) reported that the TENS group showed a higher improvement in symptoms of OAB compared to control group (mean score TENS group 6.1 versus 9.2 in control group). In addition, Souto (2014) reported that the TENS group showed improved mean symptom bother scores compared to the control group, respectively, 4.2 versus 7.0.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures complications and adverse events could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure urge incontinence episodes at 6 months was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (1 level, since assessors and patients were both not blinded to therapy) and imprecision (2 levels, 95%CI of the mean difference includes no significant effect (RR=1) and no clinically relevant effect (RR 0.75 to 1.25)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure health-related quality of life (overall score) at 12 weeks was downgraded by 2 levels because of risk of bias (1 level, due to the lost to follow-ups, and that assessors and patients were not blinded to therapy in one study) and imprecision (1 level, optimal information size was not achieved (small sample size)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure bladder severity symptoms (quality of life subdomain) at 12 weeks was downgraded by 2 levels because of risk of bias (1 level, due to the lost to follow-ups, and that assessors and patients were not blinded to therapy in one study) and imprecision (1 level, optimal information size was not achieved (small sample size)).

3. PTNS versus pharmacological treatment

3.1 Urge incontinence

Five studies reported the outcome urge incontinence. It was defined as number of episodes of urge incontinence evaluated by a 3-day voiding diary over a study period of 6 weeks (Vecchioli, 2013) or 12 weeks (Kizilyel, 2015; Manriquez, 2016), or using a 24h-voiding diary over a period of 12 weeks (Preyer, 2015), or overactive bladder symptom score questionnaire over a period of 12 weeks (Vecchioli, 2018). Results by Manriquez (2016) and Preyer (2015) will be reported descriptively, as only median results were reported.

Vecchioli (2013) reported urge incontinence episodes at 6 weeks after an intervention of only 6 weeks. The mean difference in urge incontinence episodes was -0.90 (95%CI -2.01 to 0.21) between women with urge incontinence treated with PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment.

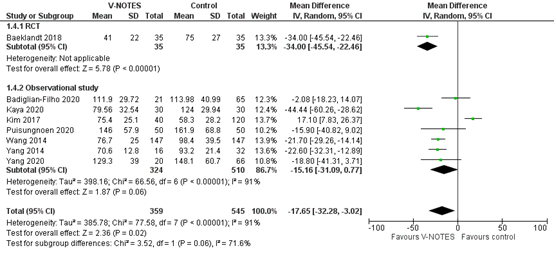

Figure 18.2.1 Urge incontinence episodes in women with urge incontinence, comparison between PTNS treatment and pharmacological treatment

Urge incontinence episodes at 12 weeks resulted in a pooled standardized mean difference of -1.13 (95%CI -2.17 to 0.47), Kizilyel (2015); Vecchioli (2018), Figure 18.2.1 Urge incontinence episodes in women with urge incontinence, comparison between PTNS treatment and pharmacological treatment.

Manriquez (2016) reported that urge incontinence episodes decreased more in the PTNS group compared to pharmacological treatment (median PTNS group 5 to 0 versus 16 to 0). Preyer (2015) reported that incontinence episodes decreased more in the PTNS group compared to pharmacological treatment (median 1.5 to 0 and 2 to 1).

3.2. Complications

The outcome complications was not reported for the comparison PTNS versus pharmacological treatment.

3.3. Adverse events

One study reported the outcome adverse events (Preyer, 2015). This was defined as side effects reported at 12 weeks, for example dry month and dizziness.

Side effects at week 12 were observed in 0/18 women treated with PTNS compared to 1/18 controls, RR 0.33 (95%CI 0.01 to 7.68). The risk difference was -0.06 (95%CI -0.20 to 0.09) between groups.

3.4 Quality of life

Six studies reported the outcome quality of life. It was defined as health related quality of life (HRQoL) and bladder severities symptoms, both assessed via OAB questionnaire short form (Ahmed (2020)), OAB short form questionnaire 6 or 13 items (higher score is worse, Vecchioli (2013); Vecchioli (2018)), patient global impression of improvement questionnaire (Vecchioli (2013)), overactive bladder symptom score (Kizilyel (2015)), incontinence impact questionnaire (Kizilyel (2015)), self-report quality of life questionnaire (Manriquez (2016)), and/or symptom impact on QoL scored on VAS (Preyer (2015)).

Vecchioli (2013) showed outcomes over a study period of 6 weeks, including an intervention of only 6 weeks. In all questionnaires quality of life improved more in women with urge incontinence treated with PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment. The mean difference was -0.20 (95%CI -0.96 to 0.56), -0.18 (-0.90 to 0.54) and -0.60 (95%CI -1.27 to 0.07), respectively for OAB short form questionnaire 6 items, 13 items and patient global improvement questionnaire.

Five studies showed outcomes over a study period of 12 weeks. In all questionnaires quality of life improved more in women with urge incontinence treated with PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment (Ahmed, 2020; Kizilyel, 2015; Manriquez, 2016; Preyer, 2015; Vecchioli, 2018). Since different questionnaires were used, outcomes will be reported separately.

Regarding overall health-related quality of life, Ahmed (2020) showed a mean difference of 13.27 (95%CI 8.26 to 18.28) between the PTNS group compared to the pharmacological group, in favour of PTNS. Vecchioli showed a mean difference of -0.20 (95%CI -0.68 to 0.28) between groups, also in favour of PTNS.

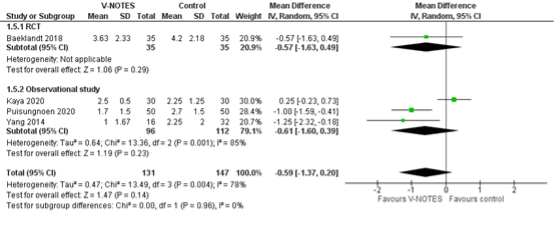

Figure 18.2.2 Overall bladder severity symptom score in women with urge incontinence, comparison between PTNS treatment and pharmacological treatment

Regarding overall bladder symptom scores, assessed in three studies (Ahmed, 2020; Kizilyel, 2015; Vecchioli, 2018), the pooled standardized mean difference was -1.27 (95%CI -2.59 to 0.06) in women with urge incontinence treated with PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment, Figure 18.2.2 Overall bladder severity symptom score in women with urge incontinence, comparison between PTNS treatment and pharmacological treatment.

The mean difference between women with urge incontinence treated with PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment for the outcome measure patient global impression of improvement questionnaire was -0.40 (95%CI -0.86 to 0.06) (Vecchioli, 2018).

The mean difference was -7.25 (95%CI -10.25 to -4.25) between women with urge incontinence treated with PTNS compared to pharmacological treatment for the outcome measure incontinence impact (Kizilyel, 2015).

Manriquez (2016) showed that outcomes of the quality of life questionnaire improved more in the PTNS group compared to the pharmacological group (mean PTNS group 33, 55, 35 to 16, 30, 20, respectively in domain 1-3 versus 33, 60, 36 to 18, 37, 23, respectively in the pharmacological group).

Preyer (2015) reported that symptom impact on QoL improved more in the PTNS group compared to the pharmacological group (median scores in PTNS group 5.1 to 1.9 versus 5.7 to 2.7 in control group).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measure was not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure urge incontinence episodes was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (1 levels, since assessors and patients were not blinded to therapy in 3 studies) and imprecision (2 level, 95%CI of the mean difference includes no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (1 levels, since assessors and patients were not blinded to therapy) and imprecision (2 level, 95%CI of mean difference includes no significant effect (RR=1) and no clinically relevant effect (RR 0.75 to 1.25)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure health-related quality of life (overall score) at 12 weeks was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (1 levels, since assessors and patients were not blinded to therapy in 3 studies) and imprecision (2 level, 95%CI of the mean difference includes no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure bladder severity symptoms (quality of life subdomain) at 12 weeks was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (1 levels, since assessors and patients were not blinded to therapy in 3 studies) and imprecision (2 level, 95%CI of the mean difference includes no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure global impression of improvement (quality of life subdomain) at 12 weeks was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (2 level, 95%CI of the mean difference includes no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5)).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure incontinence impact (quality of life subdomain) at 12 weeks was downgraded by 2 level because of risk of bias (1 level; since assessors and patients were not blinded to therapy) and imprecision (1 level; optimal information size was not achieved (small sample size)).

4. PTNS versus placebo

4.1 Urge incontinence

One study reported the outcome urge incontinence (Finazzi (2010)) at 12 weeks. It was defined as the number of incontinence episodes assessed via a voiding diary for 3 days. Incontinence episodes decreased in the PTNS group, and not in the control group (mean 4.1 to 1.8 versus 4.2 to 3.8). The mean difference was -2.00 (95%CI -2.66 to -1.34) between groups, in favour of the PTNS group.

4.2. Complications

The outcome complications was not reported for the comparison PTNS versus placebo treatment.

4.3. Adverse events

The outcome adverse events was not reported for the comparison PTNS versus placebo treatment.

4.4 Quality of life

One study reported the outcome quality of life (Finazzi (2010)) at week 12. It was defined as the incontinence quality of life score. The mean difference was 10.7 (95%CI 2.99 to 18.41) between women with urge incontinence treated with PTNS compared to a placebo.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures complications and adverse events could not be assessed with GRADE. The outcome measures were not studied in the included studies.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure urge incontinence episodes was downgraded by 1 level because of imprecision (optimal information size was not achieved (small sample size)).

The outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by 2 levels because of imprecision (2 level; 95%CI of the mean difference includes no clinically relevant effect (SMD<0.5) and not meeting the optimal information size).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of TENS or PTNS in women with urge urinary incontinence?

P: Women with urge incontinence.

I: TENS or PTNS.

C: Sham/placebo, TENS or PTNS, no treatment, drug treatment.

O: Urge incontinence episodes, complications, adverse events, quality of life.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered urge incontinence as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and complications, adverse events, and quality of life as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The GRADE default- a difference of 25% in the relative risk for dichotomous outcomes (Schünemann, 2013) and 0.5 standard deviation (reported as SMD) for continuous outcomes - was taken as a minimal clinically important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

Search strategy in 2011

The 2011 version of this guideline was an adaptation of the NICE guideline from 2006. Hence, the literature search was based on the search from the NICE Urinary incontinence guideline from 2006 (NICE, 2006) and the updated version of the ICS guideline from 2009 (Abrams, 2009), that was published during the project. The number of articles selected for title and abstract screening were not reported. In total, 1 RCT was selected (Soomro, 2001). This study does not adhere to our current PICO and is therefore excluded from the literature selection below.

Search strategy in 2021

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched (with relevant search terms until February 26th, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 399 hits.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Women with urge urinary incontinence.

- Treatment with TENS or PTNS.

- Comparison with sham/placebo, no treatment, drug treatment, or TENS/PTNS if the other is intervention.

- Investigated at least one of the outcomes as reported in the PICO.

Twenty-one studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening.

After reading the full text, 13 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 8 studies were included.

Results

Eight studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Booth J, Connelly L, Dickson S, Duncan F, Lawrence M. The effectiveness of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) for adults with overactive bladder syndrome: A systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018 Feb;37(2):528-541. doi: 10.1002/nau.23351. Epub 2017 Jul 21. PMID: 28731583.

- EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2021. ISBN 978-94-92671-13-4.

- Finazzi-Agrò E, Petta F, Sciobica F, Pasqualetti P, Musco S, Bove P. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation effects on detrusor overactivity incontinence are not due to a placebo effect: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2010 Nov;184(5):2001-6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.113. Epub 2010 Sep 20. PMID: 20850833.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, Vasavada SP; American Urological Association; Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015 May;193(5):1572-80. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.087. Epub 2015 Jan 23. PMID: 25623739.

- Kızılyel S, Karakeçi A, Ozan T, Ünüş İ, Barut O, Onur R. Role of percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation either alone or combined with an anticholinergic agent in treating patients with overactive bladder. Turk J Urol. 2015 Dec;41(4):208-14. doi: 10.5152/tud.2015.94210. PMID: 26623150; PMCID: PMC4621149.

- Levin PJ, Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Weidner AC, Amundsen CL. The efficacy of posterior tibial nerve stimulation for the treatment of overactive bladder in women: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Nov;23(11):1591-7. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1712-4. Epub 2012 Mar 13. PMID: 22411208.

- Manríquez V, Guzmán R, Naser M, Aguilera A, Narvaez S, Castro A, Swift S, Digesu GA. Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation versus extended release oxybutynin in overactive bladder patients. A prospective randomized trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016 Jan;196:6-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.09.020. Epub 2015 Oct 20. PMID: 26645117.

- Moossdorff-Steinhauser HF, Berghmans B. Effects of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation on adult patients with overactive bladder syndrome: a systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013 Mar;32(3):206-14. doi: 10.1002/nau.22296. Epub 2012 Aug 20. PMID: 22907807.

- Peters KM, Macdiarmid SA, Wooldridge LS, Leong FC, Shobeiri SA, Rovner ES, Siegel SW, Tate SB, Jarnagin BK, Rosenblatt PL, Feagins BA. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus extended-release tolterodine: results from the overactive bladder innovative therapy trial. J Urol. 2009 Sep;182(3):1055-61. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.045. Epub 2009 Jul 18. PMID: 19616802.

- Peters KM, Macdiarmid SA, Wooldridge LS, Leong FC, Shobeiri SA, Rovner ES, Siegel SW, Tate SB, Jarnagin BK, Rosenblatt PL, Feagins BA. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus extended-release tolterodine: results from the overactive bladder innovative therapy trial. J Urol. 2009 Sep;182(3):1055-61. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.045. Epub 2009 Jul 18. PMID: 19616802.

- Preyer O, Umek W, Laml T, Bjelic-Radisic V, Gabriel B, Mittlboeck M, Hanzal E. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus tolterodine for overactive bladder in women: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015 Aug;191:51-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.05.014. Epub 2015 Jun 3. PMID: 26073262.

- Ramírez-García I, Blanco-Ratto L, Kauffmann S, Carralero-Martínez A, Sánchez E. Efficacy of transcutaneous stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve compared to percutaneous stimulation in idiopathic overactive bladder syndrome: Randomized control trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019 Jan;38(1):261-268. doi: 10.1002/nau.23843. Epub 2018 Oct 12. PMID: 30311692.

- Sönmez R, Yıldız N, Alkan H. Efficacy of percutaneous and transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in women with idiopathic overactive bladder: A prospective randomised controlled trial. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2021 Jan 8:101486. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101486. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33429090.

- Soomro NA, Khadra MH, RobsonW, et al. A crossover randomized trial of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and oxybutynin in patients with detrusor instability. Journal of Urology 2001;166(1):146-9.

- Souto SC, Reis LO, Palma T, Palma P, Denardi F. Prospective and randomized comparison of electrical stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve versus oxybutynin versus their combination for treatment of women with overactive bladder syndrome. World J Urol. 2014 Feb;32(1):179-84. doi: 10.1007/s00345-013-1112-5. Epub 2013 Jun 8. PMID: 23749315.

- Teixeira Alve A, Azevedo Garcia P, Henriques Jácomo R, Batista de Sousa J, Borges Gullo Ramos Pereira L, Barbaresco Gomide Mateus L, Gomes de Oliveira Karnikoskwi M. Effectiveness of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation at two different thresholds for overactive bladder symptoms in older women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Maturitas. 2020 May;135:40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.02.008. Epub 2020 Feb 24. PMID: 32252963.

- Vecchioli-Scaldazza C, Morosetti C, Berouz A, Giannubilo W, Ferrara V. Solifenacin succinate versus percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in women with overactive bladder syndrome: results of a randomized controlled crossover study. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;75(4):230-4. doi: 10.1159/000350216. Epub 2013 Mar 28. PMID: 23548260.

- Vecchioli-Scaldazza C, Morosetti C. Effectiveness and durability of solifenacin versus percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus their combination for the treatment of women with overactive bladder syndrome: a randomized controlled study with a follow-up of ten months. Int Braz J Urol. 2018 Jan-Feb;44(1):102-108. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2016.0611. PMID: 29064651; PMCID: PMC5815539.

- Veeratterapillay, R., Lavin, V., Thorpe, A., & Harding, C. (2016). Posterior tibial nerve stimulation in adults with overactive bladder syndrome: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Urology, 9(2), 120–127.

- Wibisono E, Rahardjo HE. Effectiveness of Short Term Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation for Non-neurogenic Overactive Bladder Syndrome in Adults: A Meta-analysis. Acta Med Indones. 2015 Jul;47(3):188-200. PMID: 26586384.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What is the effect of TENS/PTNS in females with urge incontinence?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Ahmed, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: - females

Exclusion criteria: urinary tract infection, previous surgery for urinary incontinence, upper motor neuron diseases, history of genitourinary cancer, previous pelvic irradiation, pure stress urinary incontinence, genital prolapse, diabetes mellitus, pacemaker or metal implantation.

N total at baseline: Intervention: PTNS: n=20 TTNS: n=20 (i.e., TENS)

Control: n=20

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT.

|

Next to anti-Muscarinic drugs, (10 mg) once per day for 12 weeks

PTNS: 3 times/week/ 30 minutes for 12 weeks.

TTNS: 3 times/week for 12 weeks.

|

anti-Muscarinic drugs, (10 mg) once per day for 12 weeks

|

Length of follow-up: 12 weeks

Lost-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Volume at first desire to void, difference in means: PTNS (208) versus control (158.45): -49.55, p<0.01 TTNS (205) versus control (158.45): -46.55 p<0.01 PTNS (208) versus TTNS (205): -3, p=0.82

Bladder severity symptoms: PTNS (42.45) versus control (53.19): 10.74, p<0.01 TTNS (41.3) versus control (53.19): 11.89, p<0.01 PTNS (42.45) versus TTNS (41.3): 1.15, p=0.95

HRQoL: PTNS (76.19) versus control (62.92): -13.27, p<0.01 TTNS (73.61) versus control (62.92): -10.69, p<0.01 PTNS (76.19) versus TTNS (73.61): -2.58, p=0.58 |

Limitations - short duration - only patients were blinded

|

|

Finazzi, 2010 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, Italy

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not mentioned. |

Inclusion criteria: - females - age above 18 - OAB *more information appendix article

Exclusion criteria: - pregnancy - diabetes mellitus - pacemaker *more information appendix article

N total at baseline: Intervention: PTNS, n=18 Control:n=17

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT

|

PTNS, 30 minutes sessions, 3 times a week for 12 weeks.

|

Sham stimulation, 30 minutes sessions, 3 time a week for 12 weeks.

|

Length of follow-up: 12 weeks

Lost-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=1 Reason, discontinued intervention

Control: N=2 Reasons, personal

|

Mean incontinence episodes/3 days (range): Intervention: 1.8 (1.2-2.2) Placebo: 3.8 (3.0-4.5)

Mean ml voided vol (range): Intervention:186.5 (160.9-212.0) Placebo: 150.4 (125.8-175.1)

Mean I-QoL score (range): Intervention: 81.3 (73.4-89.2) Placebo: 70.6 (62.2-79.1) |

Double blinded, placebo

Limited sample size |

|

Kizilyel, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: - females - OAB - insufficient responders on previous conservative treatment.

Exclusion criteria: any known or determined urinary retention or urinary tract obstruction; history of bladder augmentation surgery; presence of a metabolic disease; any neurogenic disease causing urinary incontinence, refractory, or recurrent urinary tract infection; interstitial cystitis; bladder cancer; spinal cord injury; Alzheimer’s disease or dementia; neuropathic disorders; uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma; permanent pacemaker; bleeding diathesis; presence, suspicion of, or planning pregnancy; hypersensitivity to tolterodine and its contents; and superficial and/or deep skin infection where intervention is required

N total at baseline: Intervention: PTNS: n=10 PTNS+ACD: n=10

Control: ACD: n=10

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT. |

PTNS: 30min/week for 12 weeks PTNS+ACD: combination PTNS (30min/week) and ACD (4mg day tolterodine) for 12 weeks.

|

Anticholinergic agent (ACD): tolterodine 4mg, once a day for 12 weeks

|

Length of follow-up: 12 weeks

Lost-to-follow-up: Not mentioned.

Incomplete outcome data: Yes, outcome urge incontinence.

Intervention: PTNS, 6 missing PTNS+ACD, 6 missing, Reason not described.

Control: ACD, 1 missing. Reason not described.

|

Urge incontinence, mean (SD): PTNS= 0.13 (0.23) PTNS+ACD= 0.33 (0.57) ACD= 1.93 (0.86)

IlQ-7, mean (SD): PTNS= 5.75 (0.95) PTNS+ACD= 4.75 (1.70) ACD= 13 (4.74)

OABSS, mean (SD): PTNS= 6.5 (2.83) PTNS+ACD= 16.5 (5.33) ACD= 17.4 (3.47)

|

Missing data for one outcome without reason

Small sample size |

|

Manríquez, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, Chile

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: - female - OAB according to criteria - having a negative urine culture within 2 weeks of randomization

Exclusion criteria: - pregnancy

N total at baseline: Intervention: 36 Control:34

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT.

|

Twice a week PTNS

|

10mg extended-release oxybutynin (E.R.O.) daily

|

Length of follow-up: 12 weeks

Lost-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=2 Reasons: one changed city and one become pregnant.

Control: N=4 Reasons: three adverse event and one became pregnant. |

Difference in medians:

Urge incontinence: PTNS (0) versus E.R.O. (0); 0, p=0.23

OAB-q domain 1: PTNS (16) versus E.R.O (18); -2, p=0.89

OAB-q domain 2: PTNS (30) versus E.R.O (37); -7, p=0.04

OAB-q domain 3: PTNS (20) versus E.R.O (23); -2.5, p=0.14

*- = favour PTNS |

*”To our knowledge, this is the first trial to evaluate the effectiveness of T.C. PTNS in controlling patients’ OAB symptoms and improving quality of life”* |

|

Preyer, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, Germany and Austria

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: - female - OAB according to criteria - no prior treatment with PTNS or anticholinergics

Exclusion criteria: pregnancy or intention to become pregnant during the study period; active or recurrent urinary tract infections (more than 4 per year); residual urine of more than 100 ml; history of urinary fistula, bladder or kidney stones, interstitial cystitis; history of cystoscopic abnormalities or possible malignancy, diabetes mellitus, cardiac pacemaker or implanted defibrillator; history of anatomic or posttraumatic malformations of the lower limbs; immobility; contraindications for anticholinergics or PTNS; disability to understand the study requirements and procedures, advantages and possible side effects.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 18 Control: 18

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT |

Once a week 30-min session with PTNS

|

2mg twice a day p.o. tolterodine.

|

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Lost-to-follow-up: Intervention: N=2 Reasons; private reasons 1 (partner died), recurrent AP-symptoms with no proven context to PTNS 1 (SAE notice to EC).

Control: N=2 Reasons, pain at puncture site 2.

|

Symptom impact on QoL, difference in mean: PTNS (1.9) versus tolterodine (2.7); -0.08, p=0.07.

Side effects, difference in median: PTNS (0) versus tolterodine (1); -1, n.s.

24h-incontinence episodes, difference in median: PTNS (0) versus tolterodine (1); -1, p=0.89 |

Limited sample size No blinding |

|

Souto, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, Brazil

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: - females - OAB

Exclusion criteria: previous treatment, residual urine, cognitive and psychiatric deficits, pregnancy, glaucoma, stress urinary incontinence, any pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POPQ) C grade II, neurogenic OAB, those using anticholinergic drugs, calcium antagonists, b-antagonists, and dopamine antagonists.

N total at baseline: Intervention: TENS: n= 25 TENS + oxybutynin: n=25

Control: Oxybutynin: n=25

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT. |

TENS: twice a week 30 min. tense, for 12 weeks TENS + oxybutynin: twice a week 30 min. tense + 10mg oxybutynin, for 12 weeks

|

10mg oxybutynin, for 12 weeks

|

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Lost-to-follow-up: Intervention: TENS: n=7, reason not mentioned. TENS + oxybutynin: n=4, reason not mentioned.

Control: N=6, reason not mentioned.

|

mean scores ICIQ-SF, 3 months: TENS: 7.2 TENS+ oxy: 7.9 Oxy: 9.8

ICIQ-OAB, 3 months: TENS: 5.9 TENS+ oxy: 2.9 Oxy: 4.6

ICIQ-SF, 6 months: TENS: 8.3 TENS+ oxy: 7.4 Oxy: 13.3

ICIQ-OAB, 6 months: TENS: 6.1 TENS+ oxy: 3.0 Oxy: 9.2

|

*ICIQ-SF, represents episodes of incontinence

Small sample size, Lost to follow up without reason

No blinding.

12 weeks intervention + 12 week follow up. |

|

Vecchioli-Scaldazza, 2013 |

Type of study: RC crossover Study

Setting and country: Hospital, Italy

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not mentioned. |

Inclusion criteria: - female - OAB

Exclusion criteria: Not described in detail, patients underwent clinical evaluation before inclusion.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 20 Control:20

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT

|

Group B: PTNS twice a week for 30 min. over 6 weeks. Three months after end of treatment (wash out period) they received solifenacin succinate (SS) 5mg daily for 40 days.

|

Group A SS 5 mg daily for 40 days, washout period, PTNS twice a week for 30 min. over 6 weeks.

|

Length of follow-up: 9 months or 6 weeks?

Lost-to-follow-up: Group B: N=4 Reasons, did not start the next treatment due to the continuing improved state of symptoms (3), or refused to undergo further therapy (1).

Group A: N= 6 Reasons, suspended therapy with SS because of side effects (2), and did not start the next treatment due to the continuing improved state of symptoms (2), or refused to undergo further therapy (2).

|

Urge incontinence, mean: Group B; 1.7 Group A; 2.6 *post first intervention

Group B; 2.7 Group A; 1.7 *post second intervention

OAB-qSF, 6items, mean: Group B; 3.0 Group A; 3.2 *post first intervention

Group B; 3.5 Group A; 2.7 *post second intervention

OAB-qSF, 13 items, mean: Group B; 2.9 Group A; 3.3 *post first intervention

Group B; 2.9 Group A; 3.4 *post second intervention

PGI-I, 13 items, mean: Group B; 2.9 Group A; 2.3 *post first intervention

Group B; 3.1 Group A; 2.1 *post second intervention |

Limited sample size

* cross over design; only first 6 weeks?. |

|

Vecchioli-Scaldazza, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, Italy

Funding and conflicts of interest: None. |

Inclusion criteria: - females - OAB

Exclusion criteria: urinary tract infection, neurological disease, bladder lithiasis, genital prolapse higher than stageII on POP-Q system, uncontrolled narrow angle glaucoma, pelvic tumours, post void residual urine ≥100mL, previously treated with radiation therapy, antimuscarinic agents, antidepressants and antianxiety agents

N total at baseline: Intervention: PTNS: n=34 PTNS+SS: n=33

Control: n=27

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, RCT.

|

PTNS: once a week for 30 min. for a total of 12 weeks

PTNS+SS: PTNS + SS5mg once a day, both for 8 weeks.

|

Solifenacin Succinate (SS) 5mg once a day for 12 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: 12 weeks, 10 monhts

Lost-to-follow-up: Intervention: PTNS: n=1, no specific reason. PTNS+SS: 2, one due to side effects and one without specific reason.

Control: N =8 Reasons: side effects (dry mouth, constipation)

|

OABSS

Urge Incontinence, mean score (0-5): PTNS (2.24) versus control (2.67): -0.43, p=0.37 PTNS+SS (0.56) versus control (2.67): -2.11, p<0.01 PTNS+SS (0.56) versus PTNS (2.24): -1.68, p<0.01.

OAB-q SF 13: PTNS (2.96) versus control (3.16): -0.24, p=0.53 PTNS+SS (2.27) versus control (3.16): 0.90, p<0.01 PTNS+SS (2.27) versus PTNS (2.96): 0.69, p=0.04.

PGI-I, mean score: PTNS (2.41) versus control (2.81): 0.40, p=0.20 PTNS+SS (1.83) versus control (2.81): 0.98, p<0.01 PTNS+SS (1.83) versus PTNS (2.41): 0.58, p=0.05.

10 months: OAB-SS: PTNS (2.50) versus control (0.93): 1.57, p<0.01 PTNS+SS (5.88) versus control (0.93): 4.95, p<0.01 PTNS+SS (5.88) versus PTNS (2.50): 3.88, p<0.01.

PGI-I, mean score: PTNS (2.10) versus control (0.71): 1.39, p<0.01 PTNS+SS (5.63) versus control (0.71): 4.92, p<0.01 PTNS+SS (5.63) versus PTNS (2.10): 3.53, p<0.01. |

|

Risk of bias table

Research question: What is the effect of TENS/PTNS in females with urge incontinence?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was lost to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Ahmed, 2020 |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Central randomization with using sealed envelope system by an independent person; the envelope contained a letter indicating whether the women would be allocated to control, TTNS (i.e., TENS) or PTNS group. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Central randomization with using sealed envelope system by an independent person; the envelope contained a letter indicating whether the women would be allocated to control, TTNS or PTNS group. |

Probably no.

Reason: only patients were blinded. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: no lost to follow up.

|

Definitely yes.

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

Some concerns

Reason: only patients were blinded to allocation group. |

|

Finazzi, 2010 |

Definitely yes.

Reason: randomly assigned following a computer generated randomization list. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: randomly assigned following a computer generated randomization list. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: double blinded, placebo controlled study. |

Probably yes.

Reason: in total 3 patients were lost to follow up, reason described. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

LOW

Reason: double blinded placebo control study. Only 3 patients were lost to follow up with reason. |

|

Kizilyel, 2015 |

Probably yes.

Reason: randomly assigned but method not described |

Probably yes.

Reason: randomly assigned but method not described |

Definitely no.

Reason: patients and assessors not blinded. |

Definitely no.

Reason: 13 of 30 patients were lost to follow up without reason. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

probably yes.

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

HIGH

Reason: patients and assessors not blinded, many patients lost to follow up. |

|

Manríquez, 2016 |

Definitely yes.

Reason: randomized by permuted blocks. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: randomized by permuted blocks. |

Definitely no.

Reason: patients and assessors not blinded. |

Probably no.

Reason: 6 patients were lost to follow up with reason. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes.

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

HIGH

Reason: patients and assessors not blinded, some patients lost to follow up. |

|

Preyer, 2015 |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Randomisation was centralised by telephone and the random allocation sequence was generated by computer assistance using a method of adaptive randomisation. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: Randomisation was centralised by telephone and the random allocation sequence was generated by computer assistance using a method of adaptive randomisation. |

Definitely no.

Reason: patients and assessors not blinded. |

Probably no.

Reason: 4 patients were lost to follow up with reason. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes.

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

HIGH

Reason: patients and assessors not blinded, some patients lost to follow up. |

|

Souto, 2014 |

Definitely yes.

Reason: randomly assigned into three groups using online randomization (http:// www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1/) |

Definitely yes.

Reason: randomly assigned into three groups using online randomization (http:// www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1/) |

Definitely no.

Reason: patients and assessors not blinded. |

Probably no.

Reason: 17 patients were lost to follow up without reason. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes.

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

HIGH

Reason: patients and assessors not blinded, some patients lost to follow up. |

|

Vecchioli-Scaldazza, 2013 |

Probably yes.

Reason: randomly assigned but method not described |

Probably yes.

Reason: randomly assigned but method not described |

Definitely no.

Reason: crossover design. |

Probably no.

Reason: 10 patients were lost to follow up with reason. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes.

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

HIGH

Reason: crossover design. |

|

Vecchioli-Scaldazza, 2018 |

Definitely yes:

Reason: randomly assigned using online randomization (Graph Pad Quick Calcs software: http://www. graphad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1) by an independent biostatistician.

|

Definitely yes:

Reason: randomly assigned using online randomization (Graph Pad Quick Calcs software: http://www. graphad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1) by an independent biostatistician.

|

Probably no.

Reason: only assessors were blinded. |

Probably no.

Reason: 11 patients were lost to follow up with(out) reason. |

Definitely yes.

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported. |

Probably yes.

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

Some concerns

Reason: patients were not blinded to treatment, and some patients were lost to follow up without reason. |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Schreiner, 2010 |

Wrong comparison: bladder retraining and pelvic floor muscle exercises, and 25 were randomly selected to receive TENS in addition to the standard therapy. |

|

Schreiner, 2021 |

Wrong comparison: Kegel exercises and bladder retraining were performed alone or in combination with TENS |

|

Booth, 2018 |

SR TENS, no distinction between males/females. |

|

Veeratterapillay, 2016 |

Not in line with PICO; no distinction between males/females. For considerations. |

|

Padilha, 2020 |

Not in line with PICO |

|

Wibisono, 2015 |

SR PTNS, no distinction between males/females. For considerations. |

|

Gormley, 2015 |

AUA guideline. For considerations. |

|

Moosdorff, 2013 |

SR PTNS, no distinction between males/females. For considerations, key article. |

|

Rai, 2012 |

Cochrane review, only 1 question according to our PICO. For considerations. |

|

Levin, 2012 |

SR PTNS, only females, but not all studies included an intervention/control group. For considerations. |

|

Vecchioli, 2017 |

Wrong comparison; PTNS versus ES+PFMT |

|

Peters, 2009 |

No distinction between males/females. For considerations. |

|

Peters, 2010 |

No distinction between males/females. For considerations. |

|

Ramírez, 2021 |

No distinction between males/females. For considerations. |

|

Teixeira, 2020 |

Used 2 different TENS therapies |

|

Sönmez, 2021 |

In line with PICO but table with outcomes not available |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 14-07-2023

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 30-06-2023

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodules.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules zijn in 2020 per module schrijvers en meelezers benoemd. Deze personen werden aangewezen als vertegenwoordigers door de relevante beroepsgroepen die betrokken zijn bij de in de module beschreven zorg (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep). Alle schrijvers van modules vallend onder één richtlijn vormden samen een schrijfgroep. Alle meelezers van modules vallend onder één richtlijn vormden samen een clusterwerkgroep. In totaal resulteerde dit dus in zes werkgroep en zes clusterwerkgroepen.

Voorzitter project (technisch voorzitter)

Timmermans A. (Anne), gynaecoloog, AmsterdamUMC, NVOG

Werkgroep Urine-incontinentie bij vrouwen

Engberts M.K. (Marian), urogynaecoloog, Isala Ziekenhuis te Zwolle, NVOG

Klerkx W.M. (Wenche), urogynaecoloog, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis te Utrecht, NVOG

Koldewijn E.L. (Evert), uroloog, Catharina Ziekenhuis te Eindhoven, NVU

Labrie J. (Julien), gynaecoloog, Spaarne Gasthuis te Haarlem, NVOG

Steures P. (Pieternel), urogynaecoloog, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis te Den Bosch, NVOG

Clusterwerkgroep Urine-incontinentie bij vrouwen

Adamse C. (Corine), bekkenfysiotherapeut en klinisch epidemioloog, Antonius Ziekenhuis te Sneek, NVFB/KNGF

Bosch M. (Marlies), patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Bekkenbodem4all

Dos Santos A. (Ana), bekkenfysiotherapeut, NVFB/KNGF

Lagro-Janssen A.L.M. (Toine), prof, huisarts n.p., RadboudUMC Nijmegen, NHG

Teunissen T.A.M. (Doreth), huisarts, RadboudUMC te Nijmegen, NHG

Ondersteuning project

Abdollahi M. (Mohammadreza), adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Labeur Y.J. (Yvonne), junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Olthuis-van Essen H. (Hanneke), adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Sussenbach A.E. (Annelotte), junior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Verhoeven M. (Maxime), adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Projectleiding

Augustus 2022- nu Mostovaya I.M. (Irina) (projectleider), senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

April 2020 tot augustus 2021: Bijlsma-Rutte A. (Anne), adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

September 2021 tot januari 2022: Venhorst K. (Kristie), adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Februari 2022 tot juni 2022: Göthlin M. (Mattias), adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie van Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoek financiering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Timmermans (technisch voorzitter van het project) |

Gynaecoloog, Amsterdam UMC (0.5 fte) |

Commissie kwaliteitsdocumenten NVOG (onbetaald); projectgroep Gynae Goes Green NVOG (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Urine-incontinentie bij vrouwen - werkgroep |

||||

|

Engberts |

Urogynaecoloog ISALA |

Trainer Altis ® Sling voor Coloplast, betaald |

Geen |

Niet betrokken bij de besluitvorming rondom (fasci)slings. |

|

Klerkx |

Urogynaecoloog, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Koldewijn |

Uroloog 100% Catharina ziekenhuis Eindhoven |

Voorzitter Stichting Opleidingen Medici (SOM). Stichting acquireert gelden voor promotieonderzoek: onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Labrie |

Gynaecoloog Spaarne Gasthuis |

Medisch Manager vakgroep gynaecologie gevaceerd |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Martens |

Uroloog, Radboudumc |

Geen |

OASIS trial, implantaat PTNS, BlueWind, multicenter, PI Nijmegen. |

Geen trekker van module over PTNS/TENS. |

|

Steures |

Urogynaecoloog Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, Den Bosch |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Urine-incontinentie bij vrouwen - clusterwerkgroep |

||||

|

Adamse |

Geregistreerd bekkenfysiotherapeut en klinisch epidemioloog, Antonius Ziekenhuis Sneek. |

Commissielid Wetenschapscommissie NVFB Commissielid Richtlijn chronische bekkenpijn FMS Docent Master opleiding Bekkenfysiotherapie, SOMT Amersfoort |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Bosch |

Stichting Bekkenbodem4All. PR | Belangenbehartiging |

Fotograaf Bisdom Groningen-Leeuwarden. Deels betaald, deels vrijwilligerswerk |

Functie Belangenbehartiging Patiënten organisatie |

Geen |

|

Dos Santos |

Geregistreerd bekkenfysiotherapeut MSc bij PelviCentrum - Centrum voor Bekkenfysiotherapie Leiden |

Lid van NVFB Wetenschappelijke Commissie. Vergoeding van de reiskosten en bijwonen van vergaderingen. |

Deelname aan het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn kan ervoor zorgen dat collega’s vaker gaan verwijzen naar mijn praktijk vanwege meer bekendheid. Mogelijk belangen bij bescherming positie bekkenfysiotherapie. |

Geen actie |

|

Lagro-Janssen |

Geen werkgever |

Adviseur centrum Seksueel Geweld Gelderland-Zuid en Midden (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Teunissen |

Huisarts, zelfstandig 0,6 fte Docent, senior onderzoeker Radboudumc afdeling eerstelijnsgeneeskunde 0,4 fte |

Huisarts -> huisartswerkzaamheden (betaald) Radboudumc -> docent senior onderzoeker (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en Stichting Bekkenbodem4All voor de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie en voor deelname aan de clusterwerkgroepen. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en Stichting Bekkenbodem4All en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren worden bekeken en verwerkt.

Implementatie

|

Aanbeveling |

Tijdspad voor implementatie: 1 tot 3 jaar of > 3 jaar |

Verwacht effect op kosten |

Randvoorwaarden voor implementatie (binnen aangegeven tijdspad) |

Mogelijke barrières voor implementatie1 |

Te ondernemen acties voor implementatie2 |

Verantwoordelijken voor acties3 |

Overige opmerkingen |

|

1e |

< 1 jaar |

Blijven gelijk aan de vorige situatie |

Disseminatie van de richtlijn |

Onbekend |

Disseminatie van de richtlijn |

NVOG |

De aanbeveling zal naar verwachting niet resulteren in grote veranderingen t.o.v. de huidige praktijk. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld volgens de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg en de actualiteit van de aanbevelingen beschreven in de te reviseren modules. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie (NVOG), de Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen (NVMDL), Vereniging Klinische Genetica Nederland (VKGN), Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd (IGJ), Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen (KNOV), Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap (NHG), Nederlandse Vereniging voor Bekkenfysiotherapie en Pré- en Postpartum Gezondheidszorg, Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuizen (NVZ), Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Zorginstituut Nederland (ZiNL), Zelfstandige Klinieken Nederland (ZKN) en Zorgverzekeraars Nederland (ZN) via een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Ook definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Hultcrantz, 2017; Schünemann, 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nul effect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen