Neuromodulatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van neuromodulatie in de behandeling van kinderen met functionele urine-incontinentie?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg neuromodulatie als behandeling voor kinderen met overactieve blaas na niet succesvolle urotherapie en medicamenteuze therapie (of bijvoorbeeld niet verdragen van medicatie).

Bespreek met patiënt dat de kans op verbetering van de klachten varieert (45-71%) en de resultaten niet slechter lijken te zijn ten opzichte van medicamenteuze behandeling.

Bespreek met patiënt dat het optimale behandelschema onbekend is.

Op basis van de literatuur is er geen duidelijke uitspraak te doen over de rol van neuromodulatie voor de behandeling van andere typen urine-incontinentie (anders dan overactieve blaas)

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

De werkgroep heeft een literatuurstudie verricht naar de effectiviteit van neuromodulatie in de behandeling van kinderen met functionele urine-incontinentie. Er zijn één systematische review en vier gerandomiseerde studies geïncludeerd voor analyse. Deze studies rapporteren over de uitkomstmaten: effect van de behandeling en complicaties. Er zijn geen studies gevonden die rapporteren over de uitkomstmaat kosteneffectiviteit. De bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten ‘effect van behandeling’ en ‘complicaties’ werd beoordeeld als zeer laag vanwege methodologische beperkingen. Er kunnen op basis van de literatuur alleen geen sterke aanbevelingen worden geformuleerd over de rol van neuromodulatie in de behandeling van kinderen met functionele urine-incontinentie in vergelijking met sham, oxybutinine en biofeedback. De bewijskracht werd beoordeeld als zeer laag vanwege risico op bias en imprecisie.

In de literatuur worden diverse afkortingen door elkaar heen gebruikt om de gebruikte techniek uit te drukken. Voor de duidelijkheid wordt in deze richtlijn het volgende gehanteerd; percutaan nervus tibialis posterior (PTNS), transcutaan nervus tibialis posterior (TENS), transcutaan sacrale plexus (PTENS) en sacrale neuromodulatie met behulp van een geimplanteerd device (SNM).

Naast de geincludeerde systematische review zijn er ook andere systematische reviews/ meta-analyses verricht naar het effect van neuromodulatie in de behandeling van urine- incontinentie bij kinderen. Deze zijn in de meta-analyse hierboven niet meegenomen om overlap van dezelfde RCT’s te voorkomen. Hieronder wel een samenvatting. In een meta-analyse van O’ Sullivan (2020) die 6 RCTs (234 patiënten) bevat, wordt parasacrale neuromodulatie (PTENS) +/- urotherapie vergeleken met urotherapie +/- antimuscarinica of sham behandeling. Zij beschrijven een 1.92 x hogere kans op succes ten opzichte van urotherapie alleen cq sham en 1,56 x hogere kans op succes ten opzichte van urotherapie gecombineerd met antimuscarinica. Dit was enkel het geval voor therapie-naïeve kinderen. Er werd geen verschil aangetoond indien kinderen reeds eerder behandeld waren met urotherapie en/of antimuscarinica. In een andere network meta-analyse van Qiu met 5 RCTs en 446 patiënten worden verschillende behandelingen (neuromodulatie, medicatie, urotherapie) met elkaar vergeleken met als primaire uitkomstparameter, maximale blaascapaciteit. De auteurs concluderen dat parasacrale zenuwstimulatie (PTENS) superieur was ten opzichte van urotherapie en medicamenteuze behandeling wat betreft toename in maximale blaascapaciteit, maar toonden geen verschil aan in mictiefrequentie en/of mate van urineverlies. Fernandez (2017) includeert 5 RCTs met 225 patiënten en concludeert dat neuromodulatie meer succes (> 50% verbetering) heeft ten opzichte van urotherapie RR 2.8 95% CI 1.1-7.2 maar niet voor > 90% effect, RR 8.2 95% CI (0.65-105.9). Dit betrof overigens enkel de behandelingen die in het ziekenhuis werden gegeven. Thuisbehandelingen gaven geen significant verschil ten opzichte van urotherapie.

Op basis van bovenstaande literatuur is er geringe bewijskracht voor transcutane sacrale of tibiale neuromodulatie als behandeloptie voor functionele urine-incontinentie bij kinderen ten opzichte van medicamenteuze behandeling, biofeedback en of urotherapie. De individuele studies laten zeer uiteenlopende succespercentages zien met complete respons variërend tussen de 0% (Borch 2017) en 75% (Casal-Beloy 2021) wanneer het wordt vergeleken met oxybutinine als medicamenteuze behandeling. Indien het wordt vergeleken met biofeedback worden er complete respons percentages gevonden van 61% versus 55% (p = 0.483).

Bij volwassenen met overactieve blaas tonen studies aan dat posterieure tibiale zenuwstimulatie superieur is ten opzichte van medicamenteuze behandeling wat betreft urineverlies maar niet ten opzichte van andere klachten zoals urge en mictiefrequentie (level 1a) met behoud van effect tot in ieder geval 3 jaar na behandeling. Er werd geen verschil gezien in percutane versus transcutane behandeling (level 1a) wat betreft urge, kwaliteit van leven en mictiefrequentie. De EAU guidelines adviseren om neuromodulatie te overwegen als behandeloptie voor volwassen met overactieve blaas.

In de literatuur is geen eenduidigheid in het behandelprotocol en zijn er veel verschillen in onder andere toediening (sacrale stimulatie, posterieure tibale zenuw stimulatie, transcutaan of percutaan), duur behandeling (30 minuten, uur, 2,5 uur), parameters (10 Hz-20Hz, 200-700 usec), frequentie (dagelijks, 1 x per week - 3 x per week) en totale duur behandeling (6 weken, 3 maanden). Deze heterogeniteit maakt het dus lastig om conclusies te trekken op basis van de beschikbare gegevens. Op basis van de huidige literatuur bij volwassenen wordt veelal een behandelschema met een totale duur van 12 weken aangehouden. Dit is gebaseerd op een hoger percentage van terugval voor percutane tibiale zenuwstimulatie bij een 6 weken schema (Finazzi-Agro, 2010). Er is geen literatuur beschikbaar ten aanzien van optimale totale behandelduur voor transcutane neuromodulatie. Ook is bekend dat bij volwassenen een aanzienlijk deel een onderhoudsschema nodig heeft na de initiele 12-wekelijkse behandeling. Er is beperkte literatuur hierover bij kinderen. Het percentage kinderen dat een onderhousdschema nodig heeft varieert in de literatuur tussen de 29-50% (Capitanucci, 2009).

Er is geringe literatuur bekend over sacrale stimulatie met behulp van een implantaat (SNM) bij kinderen. De weinige studies die hierover hebben gepubliceerd laten een verbetering van de klachten zien in 66-88% met complete response in 28-41%. Bij 58% was er een re-operatie nodig vanwege uiteenlopende redenen ( gebroken draad, dislocatie draad, infectie, batterij problemen) en bij 35% werd het implantaat uiteindelijk verwijderd. Gezien de hoge kosten en het hoge aantal re-interventies (met ook aanzienlijk percentage verwijdering van het implantaat) wordt deze behandeling op dit moment nog weinig uitgevoerd in Nederland.

De kans op complicaties (dermatitis) van neuromodulatie lijkt gering. De invloed van neuromodulatie op de darmmotiliteit is onduidelijk waarin sommige studies een verbetering aantonen van obstipatie, sommige een toename zien in fecale incontinentie en andere meer obstipatie zien in de groep die neuromodulatie onderging. Omdat functionele urine-incontinentie en obstipatie nauw verwant zijn, is het niet duidelijk of dit toe te schrijven is aan de aandoening zelf of specifiek het gevolg is van neuromodulatie als behandeling.

Waarden/ voorkeuren voor patiënten

Op basis van de literatuur concludeert de werkgroep dat neuromodulatie als behandel modaliteit kan worden overwogen voor functionele urine-incontinentie bij kinderen. Ondanks dat er geringe literatuur is waarin neuromodulatie wordt vergeleken met urotherapie, is de werkgroep van mening dat neuromodulatie niet aangeboden moet worden voorafgaand aan urotherapie. Indien urotherapie echter onvoldoende effect heeft en er bij ouders/ kinderen weerstand is tegen medicamenteuze behandeling en/of deze niet verdragen wordt, kan neuromodulatie als alternatief worden geboden als volgende behandelstap. Bespreek met patiënt dat neuromodulatie overwogen kan worden als urotherapie onvoldoende effect heeft met kans op verbetering van klachten tussen de 46-71%. Bespreek dat er weinig risico’s aan verbonden zijn. Ook dient te worden vermeld dat het op basis van de beschikbare literatuur niet duidelijk is wat de beste modaliteit is (transcutaan versus percutaan en/of welke instellingen het beste resultaat geven).

De behandeling met neuromodulatie is voorbehouden aan zorgverleners die betrokken zijn bij de behandeling van functionele urine-incontinentie bij kinderen

Kosten

Bij volwassen met overactieve blaas is neuromodulatie kosten effectief gebleken. Het lijkt aannemelijk dat er ook plaats is voor neuromodulatie bij kinderen met therapieresistente overactieve blaas. Neuromodulatie is vergoede zorg vanuit het Zorginstituut Nederland voor kinderen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In neuromodulation, stimulation of specific peripheral nerves or their dermatomes intend to cause an alteration of the afferent and efferent neurological pathways between the brain, brain stem and pelvic organs involved in the micturition cycle with subsequent potential normalization of abnormal function of the bladder. In children the two most common forms of neuromodulation are posterior tibial nerve stimulation (stimulated with either transcutaneous skin pads (TENS) or a with a percutaneous needle (PTNS)) and the stimulation of the parasacral plexus PTENS (through transcutaneous skin pads). Stimulation of the sacral plexus with implanted neuromodulators (SNM) is not common in children. It is yet unclear which role neuromodulation has in the treatment of urinary incontinence in children compared to other treatments.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

a. Comparison PTENS versus sham

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of PTENS/TENS compared to sham is on treatment effect in children with functional urinary incontinence. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of treatment with PTENS/TENS compared to sham on cost effectiveness in children with functional urinary incontinence. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of treatment with PTENS/TENS compared to sham on complications in children with functional urinary incontinence. |

b. Comparison (P)TENS versus oxybutynin

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of PTENS compared to oxybutynin is on treatment effect in children with functional urinary incontinence.

Source: Borch (2017); Casal-Beloy (2021) & Quintiliano (2015) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of PTENS compared to oxybutynin is on complications in children with functional urinary incontinence.

Source: Borch (2017); Casal-Beloy (2021) & Quintiliano (2015) |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of treatment with PTENS compared to oxybutynin on cost effectiveness in children with functional urinary incontinence. |

c. Comparison PTENS versus biofeedback

|

Very low GRADE |

It is uncertain what the effect of PTENS compared to biofeedback is on treatment effect in children with functional urinary incontinence.

Source: Dos-Reis (2019) |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of treatment with PTENS compared to biofeedback on cost effectiveness in children with functional urinary incontinence. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of treatment with PTENS compared to biofeedback on complications in children with functional urinary incontinence. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

a. Comparison PTENS or TENS versus sham

The SR by Cui (2020) performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of transcutaneous sacral (PTENS) or transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (TENS) on OAB symptoms in children. Databases MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases were searched until June 2019. In addition, reference lists from studies and reviews were checked. Trials that reported the effect of PTENS/ TENS treatment in children on urodynamic indexes and objective OAB symptoms were included. Exclusion criteria were not reported. In total, eight RCTs were included in the SR. Five studies reported the comparison of interest for the current analysis of literature: PTENS or TENS versus sham treatment (Borch 2017, Boudaoud, 2015; Hagstroem, 2009; Lordelo, 2010; & Patidar, 2015). Treatment duration varied between 48 hours-12 weeks. In total, 78 children received active treatment and 65 received sham treatment. Results were presented as pooled analysis of all eight included studies. Primary outcome measures were wet days per week, maximum voided volume and average voided volume. The secondary outcomes were VAS scale scores for response treatment and response rate according to the ICCS criteria.

b. Comparison PTENS versus oxybutynin

The RCT conducted by Borch (2017) evaluated whether the effect of combination therapy with sacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PTENS) and oxybutynin is a superior treatment compared to either treatment alone in children with urge incontinence. Children were eligible for inclusion if they were between five and fourteen years old, had urge incontinence more than two times per week, had more than four micturitions per day, had ongoing symptoms of overactive bladder (OAB), were refractory to more than two months of urotherapy and had a normal physical examination.

Children were randomized into three groups: group 1) active PTENS and active oxybutynin treatment (n=22), group 2) active PTENS and placebo oxybutynin treatment (n=21) and group 3) active oxybutynin and placebo PTENS treatment (n=23). For the current analysis of literature only group 2 and group 3 are considered relevant. Power analysis revealed 90 patients to be enrolled (30 in each group)

Treatment was performed at home. For PTENS an Elpha 4 Conti Nerve Stimulator (FH Service, Odense, Denmark) was used with 50 x 50 mm PALS platinum electrodes (FH Service). The electrodes were placed on the skin at level S2 to S3. A 10 Hz frequency was used with a 200-second pulse duration and biphasic waveform. Children were instructed to use the highest tolerable intensity up to a maximum of 40 mA. The manufacturer had modified the sham stimulators not to deliver any electrical current for the placebo treatment. The exteriors of the active and placebo stimulators were identical. Parents and children were instructed to use PTENS for two hours daily and note the intensity of PTENS used. The dose of oxybutynin was 5 mg twice daily for all children. Placebo and active tablets appeared identical.

Mean age of the children was 7.3 ± 1.6 years. Response to treatment was analyzed as intention to treat. Children, parents and investigators were blinded regarding the intervention. The intervention lasted for ten weeks and included three visits to an outpatient clinic (at baseline, after three weeks and after the intervention at 11 weeks). During the intervention period fifteen children were excluded from the study for various reasons (lack of compliance, appendicitis, moving away, developing post void residual and urinary tract infection). The majority of patients were male (74%).

The primary outcome was treatment effect (number of wet days weekly) and transcribed into ICCS response. Secondary outcomes were among others severity of incontinence episodes. Side effects were only seen in de oxybutynin group (35%).

The RCT conducted by Casal-Beloy (2021) aimed to compare the efficacy of sacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PTENS) versus oxybutynin therapy in children with OAB. Inclusion criteria were: children aged five to sixteen years, diagnosis of OAB according to the ICCS definition, baseline value in the dysfunctional voiding and incontinence scoring system (DVISS) questionnaire of > 8.5 points. Obtaining a normal or in hood flowmetry, without electromyographic activity, performed before receiving treatment was a mandatory criterion.

Initially, all patients were treated with standard urotherapy (dietary and voiding habits, correct posture) and constipation management (dietary measures and polyethylene glycol) for three months. Patients with persistent OAB despite these measures were included in the study. Patients were randomly assigned to group 1) PTENS treatment (n=40) or group 2) oxybutynin treatment (n=46). Power analysis revealed 118 to be enrolled (59 in each group). Treatment was performed at home. For the PTENS treatment, the electrodes were placed on the skin at level S2 to S3. A frequency of 10 Hz and a pulse width of 200 msec and a maximum tolerated pulse wave intensity without pain (individually determined per patient) were used. The instrument used during therapy was UroSTIM 2.0. Sessions took place daily and lasted for 20 minutes. Patients randomized to oxybutynin treatment received daily oral medication with a dose of 0.5mg/kg/day in three doses (every eight hours). The intervention lasted six months, and measurements were conducted at baseline, one, three and six months.

Median age of the children was 9 (IQR 7 to 12) and 8 (IQR 7 to 15.5) in the PTENS and oxybutynin group respectively. The majority of patients were female (59.3%). The primary outcome was treatment effect according to the ICCS criteria based on the difference in DVISS pre-post scores. Secondary outcome was to compare the rate of adverse effects in both treatments.

Quintiliano (2015) and colleagues performed a RCT with the objective to assess the effectiveness of sacral transcutaneous electrical stimulation (PTENS) compared to oxybutynin to treat children with OAB. Patients were between four and seventeen years old with urgency, a bell-shaped uroflowmetry curve, post-void residual urine volume less than 10% of bladder capacity expected for age or below 20 ml, DVSS score greater than normal (6 in boys and 9 in girls), voiding urgency at least three times per week and no previous treatment, were included. Children were randomized to receive either: 1) treatment with PTENS and placebo drug (n=13) or 2) treatment with oxybutynin and sham scapular electrical therapy (n=15). Power analysis was not mentioned in the article. Patients were blinded to their treatment type.

The electrical stimulation technique consisted of the application of electrical current produced by a Dualpex Uro 961 generator (Quark) using surface electrodes for a total of 20 sessions of 20 minutes each 3 times per week on alternate days. A symmetrical biphasic square current pulse was used with a frequency of 10 Hz, pulse width 700 milliseconds and intensity increased up to the level of below the motor threshold. Two surface electrodes were placed symmetrically on the parasacral region and two were placed symmetrically on one scapula. Stimulation was done using the parasacral and scapular electrodes in groups 1 and 2, respectively. Patients randomized to oxybutynin treatment received daily oral medication with a dose of 0.3mg/kg/day twice daily. Treatment lasted for three months. Mean age of the children was 6.3 ± 2.4 years and 6.5 ± 2.0 years in the PTENS and oxybutynin group respectively. The majority of patients was female in both groups (69% and 67%). Outcome measures included complete response, VAS and DVSS scores, voiding diary data and side effects.

c. Comparison PTENS vs biofeedback

Dos Reis (2019) performed a RCT to evaluate the efficacy of biofeedback and sacral transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (PTENS) for the treatment of children with lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUT). Children diagnosed with primary non-monosymptomatic enuresis aged five to sixteen years were included in the study. Children were randomized to group 1) biofeedback treatment (n=31), or group 2) PTENS treatment (n=33). Power analysis was not mentioned in the article. Of the patients included in the study, 41 were diagnosed with OAB, fourteen with dysfunctional voiding and nine had both conditions. Fifteen children had received previous treatment elsewhere.

Standard urotherapy was performed in both treatment groups. In the biofeedback group rehabilitation of the pelvic floor muscles was performed with EMG associated with uroflow (Uranus II, Alacer Biomedical, Sao Paulo, Brazil). Two EMG surface electrodes were placed on the pelvic floor muscles at 3- and 9 hours position. The training was carried out in a sitting position. Biofeedback was animated with a graphic layout on a computer screen, children were instructed to perform initial contraction and prolonged relaxation of the pelvic floor. In the PTENS group, sessions were carried out in a prone position with surface electrodes positioned in the sacral region (S2-S4). A frequency of 10Hz with a generated pulse of 700 msec and current intensity adjusted to patient sensitive threshold was used (Dualpex 961 Quark Sao Paulo, Brazil). Sessions were performed in the hospital, twice a week for 20 minutes per session. The number of sessions varied according to the progress of the treatment, with a maximum of 20 sessions. Follow-up was performed six months after baseline.

Mean age of the children was 9.2 ± 2.4 and 9.6 ± 2.9 years in the biofeedback and PTENS group respectively. Outcome measures included treatment response according to ICCS criteria, resolution of daytime and nighttime symptoms, including urinary leakage, improvements in voiding diaries parameters, dysfunctional voidig score system (DVSS) and changes in uroflow.

Results

a. Comparison PTENS/ TENS versus sham

1. Treatment effect

Five studies included in the SR (Cui, 2020) reported the comparison PTENS or TENS versus sham treatment (Borch, 2017; Boudaoud, 2015; Hagstroem, 2009; Lordelo, 2010 & Patidar, 2015). All of which reported treatment effect according to the ICCS.

One study reported data on wet days per week (Hagstroem, 2009). Thirteen patients received PTENS and twelve received sham treatment. Mean scores of wet days / week -3 ± 1.53 and 0.5 ± 0.77 were reported in the PTENS and sham condition respectively (MD -3.50 (95% CI -4.44 to 2.56)), in favour of PTENS treatment.

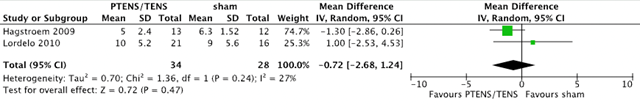

A VAS score for measuring urgency was reported by two studies (Hagstroem, 2009 & Lordelo, 2010) with 62 patients (34 PTENS/TENS and 28 sham). An urgency VAS was used (0 to 10). A mean difference of -0.72 (95% CI -2.68 to 1.24, p 0.24) was found. This is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing VAS scores (urgency) for the comparison PTENS/TENS versus sham.

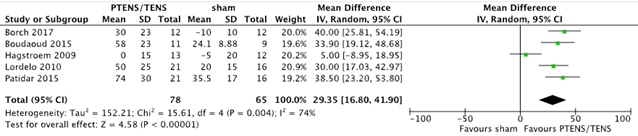

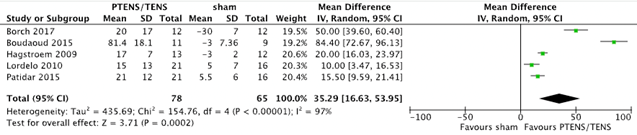

Five studies (Borch 2017; Boudaoud 2015; Hagstroem 2009; Lordelo 2010 & Patidar 2015) with 143 patients (78 PTENS/TENS and 65 sham) reported changes in maximum voided volume (MVV) and average voided volume (AVV). For MVV a mean difference of 29.35 ml (95%CI 16.80 to 41.90, p = < 0.001) in favour of PTENS/TENS was found. AVV showed a mean difference of 35.29 ml (95% CI 16.63 to 53.95, p < 0.001) in favour of PTENS/TENS. The pooled results are shown in figure 2 and figure 3. Children that received PTENS/TENS treatment had a higher MVV and AVV than children who received sham treatment.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing maximum voided volume for the comparison PTENS/TENS versus sham.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing average voided volume for the comparison PTENS/TENS versus sham.

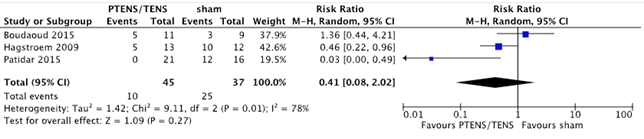

Three studies with 82 patients (45 PTENS/TENS and 37 sham) reported data on the number of patients with no response (Boudaoud, 2015; Hagstroem, 2009 & Patidar, 2015). No response occurred in 10 (22.2%) patients who received PTENS/TENS treatment and in 25 patients (67.7%) who received sham treatment (RR 0.41 (95% CI 0.08 to 2.02, p=0.27)) in favour of PTENS/TENS (figure 4). It seems that more children in the sham condition had no response, however the confidence interval is very wide.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing number of patients with no response for the comparison PTENS/TENS versus sham.

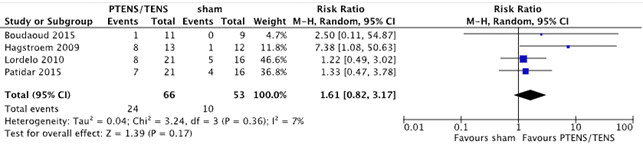

Four RCTs with 119 patients (66 PTENS/TENS and 53 sham) included data on the number of patients with a partial response (Boudaoud, 2015; Hagstroem, 2009; Lordelo, 2010 & Patidar, 2015). Of the patients treated with PTENS/TENS, 24 (36.4%) reported partial response of symptoms. In the sham treatment condition this occurred in 10 patients (18.9%) (RR 1.61 (95% CI 0.82 to 3.17, p=0.17)) in favour of PTENS/TENS (figure 5). Children who received PTENS/TENS treatment seem to have a better response.

Figure 5. Forest plot showing number of patients with partial response for the comparison PTENS/ TENS versus sham.

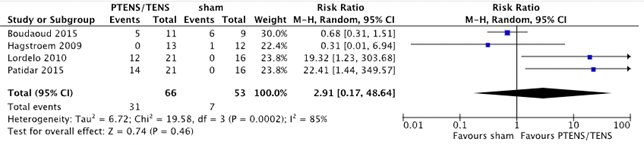

Four studies with 119 patients (66 PTENS/TENS and 53 sham) included data on the number of patients with a full response (Boudaoud, 2015; Hagstroem, 2009; Lordelo, 2010 & Patidar, 2015). Of the patients treated with PTENS/TENS, 31 (47%) experienced full response compared to 7 patients (13%) who received sham treatment (RR 2.91 (95% CI 0.17 to 48.64, p=0.46)) in favour of PTENS/TENS (figure 6). The large confidence interval makes it difficult to assess whether PTENS/TENS results in more full response compared to sham.

Figure 6. Forest plot showing number of patients with full response for the comparison PTENS/TENS versus sham.

The outcome measure daily voiding frequency was reported by one RCT (Hagstroem, 2009) with 25 patients (13 PTENS and 12 sham). A mean score of -1 ± 0.5 and -0.25 ± 0.25 was reported in the PTENS and sham condition respectively (MD -0.75 (95% CI -1.06 to -0.44)). It seems that children who received PTENS have a lower voinding frequency than children who received sham.

The outcome measure daily incontinence episodes was reported by one RCT (Hagstroem, 2009) with 25 patients (13 PTENS and 12 sham). A mean score of -1 ± 0.5 and 0 ± 0.5 was reported in the PTENS and sham condition respectively (MD -1.0 (95% CI -1.39 to -0.61)). It seems that children who received PTENS have fewer daily incontinency episodes than children who received sham.

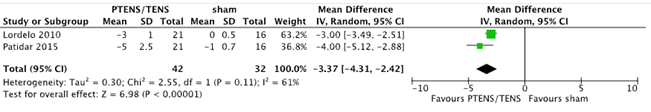

The outcome measure number of daily voids was reported by two RCTs (Lordelo, 2010 & Patidar, 2015) with 74 patients (42 PTENS/TENS and 32 sham). A mean difference of -3,37 (95% CI -4.31 to -2.42, p < 0.001) was found in favour of PTENS/TENS (figure 7). It seems that children who received PTENS/TENS have a lower number of daily voids than children who received sham treatment.

Figure 7. Forest plot showing number of daily voids for the comparison PTENS/TENS versus sham.

2. Cost effectiveness

There was no data available for this outcome measure.

3. Complications

There was no data available for this outcome measure.

b. Comparison (P)TENS versus oxybutynin

1. Treatment effect

Treatment effect was reported in three studies (Borch, 2017; Casal-Beloy, 2021; Quintilliano, 2015) It was not possible to pool the results due to various outcome measures used for treatment effect (number of wet days/ week, DVISS score, complete response) and varying follow-up time.

The study of Borch (2017) compared the effect of three treatment modalities on the number of wet days a week: group 1) active PTENS and active oxybutynin treatment (n=22), group 2) active PTENS and placebo oxybutynin treatment (n=21) and group 3) active oxybutynin and placebo PTENS treatment (n=23).

For the current analysis of literature only group 2 and group 3 are considered relevant. However, severity of UI and frequency was only reported for comparison of active PTENS and oxybutynin versus PTENS and placebo. There was no comparison of these outcomes between group 2 and 3.

Treatment effect was assessed after ten weeks of intervention (at week 11) and included number of wet days weekly. In the oxybutynin group, three out of fourteen (21%) children completing the intervention reported resolution of daytime urinary incontinence compared to zero out of nineteen completing the PTENS intervention.

Casal-Beloy (2021) reported treatment effect at six-month follow-up by means of success rate (defined as complete or partial response), parameters of a voiding diary (voiding frequency (VF), mean voided volume (MeVV) and max voided volume (MaVV) and DVISS score. Patients were treated with PTENS (n=40) or oxybutynin (n=46). Success rate was classified according to ICCS consensus: No response: <50% improvement; Partial response; 50 to 99% improvement; Complete response: 100% improvement).

The success rate was 75% and 41% in the PTENS and oxybutynin groups respectively. Both groups improved at the end of treatment with regard to VF, MeVV and MaVV. The decrease in VF (PTENS: from median 8 IQR 7.25 to 11 to 6 IQR 5 to 6.75 & Oxy: from 9 IQR 8 to 12 to 6.5 IQR 6 to 8) and increase in MeVV were significantly greater in the PTENS group (PTENS: from median 90 IQR 70 to 172.5 to 160 IQR 110 to 250 & Oxy: from 90 IQR 70 to 150 to 125 IQR 110 to 180). The increase in MaVV was not significantly different (p= 0.5) between groups (PTENS: from median 200 IQR 162.5 to 330 to 265 IQR 200 to 377.5 & Oxy: from 210 IQR 77 to 305 to 250 IQR 200 to 320).

A greater decrease in DVISS score after six months of treatment was observed in the PTENS group compared to the oxybutynin group. Median values after treatment were 6 (IQR 3 to 9) and 10 (IQR 8.75 to 13.25) in the PTENS and oxybutynin group respectively (p< 0.005).

The percentage of patients with urgency and daytime incontinence significantly improved in both groups after six months of treatment compared to baseline. However, there was no significant difference in the improvements between groups (p=0.47 for urgency and p=0.52 for daytime incontinence).

Quintiliano (2015) evaluated treatment effect after three months. Questionnaires were used inquiring about symptoms using VAS, the DVSS and voiding diaries. Rome III criteria were used to assess constipation. Patients were treated with PTENS and placebo drug (n=13) or oxybutynin and sham electrical stimulation (n=15). After treatment, six out of thirteen (46%) patients in the PTENS group showed complete symptom resolution compared to three out of fifteen (20%) in the oxybutynin group (p=0.2). Mean DVSS significantly improved in both groups from baseline to three months, however, no difference was seen between treatments. Treatment significantly improved voiding parameters in both groups (VF, MeVV and MaVV). However, no differences between groups were found. At baseline, constipation was noted in six patients in the PTENS group and in nine patients in the oxybutynin group. After treatment, all patients in the PTENS group reported improvement in constipation, compared to five patients in the oxybutynin group.

Overall, it is not clear whether PTENS is more effective in treating urinary incontinence compared to oxybutynin.

2. Cost effectiveness

There was no data available for this outcome measure.

3. Complications

Borch (2017), Casal-Beloy (2021) and Quintilliano (2015) all reported on the outcome measure complications. It was not possible to pool the results because studies reported different types of complications.

Borch (2017) reported one serious adverse event (appendicitis) in the PTENS group, not considered to be related to the study treatment.

In the study by Casal-Beloy (2021), complication rate was 15% in the PTENS group compared to 26.1% in the oxybutynin group (total n= 40 and 46 per group respectively). Reported complications in the PTENS group were dermatitis in the sacral region (n=1), fecal losses (n=5) and urgency (n=5). In the oxybutynin group constipation (n=6), abdominal pain (n=2), dry mouth (n=2) and increased post-void residual volume (n=2) were reported.

The study by Quintilliano (2015) reported no complications in the PTENS group (n=13). In the oxybutynin group (n=15), dry mouth (n=9), hyperthermia (n=4) and hyperemia (n=7) were reported.

Overall, it seems that oxybutynin has more risk of complications than PTENS in children with urinary incontinence.

c. Comparison PTENS vs biofeedback

1. Treatment effect

Dos Reis (2019) evaluated treatment effect after six months (n= 64 patients, of which 31 received biofeedback treatment and 33 received PTENS treatment). Outcome measures were change in urinary incontinence (complete or partial response in daytime and nighttime), bladder capacity, parameters of a voiding diary (urgency episodes, voiding frequency, bladder capacity), changes in uroflow and DVSS score.

The rate of complete response was 54.9% and 60.3% for daytime symptoms and 29.6% and 25% for nighttime symptoms in the biofeedback and PTENS groups respectively (p > 0.05). An improvement in other parameters was observed in both groups. Resolution of urgency (89.4% biofeedback and 93% PTENS) and an increase in bladder capacity was observed in both groups (p > 0.05). An increase in maximum flow was observed in the biofeedback group (20.49 mL/s to 26.77 mL/s), but not in the PTENS group (23.34 mL/s to 23.73 mL/s). Mean DVSS significantly improved in both groups from baseline to six months, however, no difference was seen between treatments. Overall, when comparing the results of both treatments no differences in improvement of symptoms between groups were found.

2. Cost effectiveness

There was no data available for this outcome measure.

3. Complications

There was no data available for this outcome measure.

Level of evidence of the literature

Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials start at GRADE high.

The level of evidence regarding the comparison PTENS/ TENS versus sham was downgraded to very low GRADE. For the outcome measure treatment effect: one level because of study limitations (risk of bias; blinding unclear); two levels for number of included patients (imprecision). Due to lack of evidence, no grading was possible for the outcome measures cost effectiveness and complications.

The level of evidence regarding the comparison PTENS versus oxybutynin was downgraded to very low GRADE. For the outcomes measures treatment effect and complications: Two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias; selective reporting, incomplete outcome data, allocation concealment unclear, blinding unclear, participants missing from flowchart); one level for inconsistency; and two levels for number of included patients (imprecision). Due to lack of evidence, no grading was possible for the outcome cost effectiveness.

The level of evidence regarding the comparison PTENS versus biofeedback was downgraded to very low GRADE. For the outcome measure treatment effect: one level because of study limitations (risk of bias; allocation concealment and blinding unclear); two levels for number of included patients (imprecision). Due to lack of evidence, no grading was possible for the outcome measures cost effectiveness and complications.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the efficacy of neuromodulation in the treatment of children with functional urinary incontinence?

| Patients: | Children with functional urinary incontinence (overactive bladder, dysfunctional voiding, voiding postponement, urinary urge incontinence, stress incontinence, hypotonic bladder) |

| Intervention: | Neuromodulation: Parasacral transcutaneous electrical stimulation (PTENS), percutaneous or transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS/TENS) and sacral nerve modulation/stimulation (SNM) |

| Control: | Urotherapy (including pelvic floor treatment) and/ or medication and/ or Botulinum-Toxin A and/or no therapy |

| Outcome measures: | 1) Treatment effect (subjective improvement, objective improvement, among which improvement of uroflometry (with residue determination), change in urinary incontinence (according to ICCS criteria), voiding frequency, urgency, quality of life, bladder volume), 2) cost effectiveness and 3) complications |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered treatment effect and cost-effectiveness as critical outcome measures for decision making; and complications as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Effect treatment:

- Subjective improvement

- Objective improvement: improvement of uroflowmetry values with residual determination, degree of urinary incontinence (according to ICCS criteria) micturition frequency, maximum and average bladder capacity, urgency complaints, quality of life

- Complications: pain, redness, numbness

The working group defined the following minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- Effect of treatment:

- Dichotomous (dry versus non-dry): 15% difference

- Continuous: 0.5 SD or -0.5 < SMD > 0.5

Complications: 25% difference (RR < 0.8 or > 1.25)

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 until 8th of June, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 339 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: studies reporting original data, systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies reporting on the use of neuromodulation for treatment of children with functional urinary incontinence. Eighty-nine studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 85 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included.

Results

One systematic review (SR) was included in the analysis of the literature (Cui, 2020). In addition, four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Borch 2017; Casal-Beloy 2021; Dos-Reis 2019 & Quintilliano 2015) were included. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. The results shown are divided into three groups:

a) Parasacral transcutaneous electrical stimulation (PTENS) or transcutaneous posterior nerve tibial nerve stimulation (TENS) versus sham

b) PTENS versus oxybutynin

c) PTENS versus biofeedback.

No other evidence was found comparing the effectiveness of treatment with either percutaneous forms, sacral or transcuteanous forms of neuromodulation compared to urotherapy, Botulinum-Toxin A, medication or sham treatment.

Referenties

- 1 - Blais A, Bergeron M, Nadeau G, Ramsay S, Bolduc S. Anticholinergic use in children: persistence and patterns of therapy. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2016 Mar-Apr;10(3-4):137-40. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3527. PMID 27217862

- 2 - doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3527. PMID 27217862

- 3 - Borch L, Hagstroem S, Kamperis K, Siggaard CV, Rittig S. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Combined with Oxybutynin is Superior to Monotherapy in Children with Urge Incontinence: A Randomized, Placebo Controlled Study. J Urol. 2017 Aug;198(2):430-435. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.03.117. Epub 2017 Mar 19. PMID: 28327453.

- 4 - Capitanucci ML, Camanni D, Demelas F, Mosiello G, Zaccara A, De Gennaro M. Long-term efficacy of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for different types of lower urinary tract dysfunction in children. J Urol. 2009 Oct;182(4 Suppl):2056-61. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.007. Epub 2009 Aug 20. PMID: 19695611.

- 5 - Casal-Beloy I, García-Novoa MA, García González M, Acea Nebril B, Somoza Argibay I. Transcutaneous sacral electrical stimulation versus oxibutynin for the treatment of overactive bladder in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2021 Oct;17(5):644.e1-644.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.06.011. Epub 2021 Jun 11. PMID: 34176749.

- 6 - Cui H, Yao Y, Xu Z, Gao Z, Wu J, Zhou Z, Cui Y. Role of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation in Treating Children With Overactive Bladder From Pooled Analysis of 8 Randomized Controlled Trials. Int Neurourol J. 2020 Mar;24(1):84-94. doi: 10.5213/inj.1938232.116. Epub 2020 Mar 31. PMID: 32252190; PMCID: PMC7136445.

- 7 - Dos Reis, J. N., Mello, M. F., Cabral, B. H., Mello, L. F., Saiovici, S., & Rocha, F. E. T. (2019). EMG biofeedback or parasacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with lower urinary tract dysfunction: A prospective and randomized trial. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 38(6), 1588-1594.

- 8 - Fernandez N, Chua ME, Ming JM, Silangcruz JM, Zu'bi F, Dos Santos J, Lorenzo AJ, Braga LH, Lopes RI. Neurostimulation Therapy for Non-neurogenic Overactive Bladder in Children: A Meta-analysis. Urology. 2017 Dec;110:201-207. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.08.003. Epub 2017 Aug 17. PMID: 28823638.

- 9 - Finazzi-Agrò E, Petta F, Sciobica F, Pasqualetti P, Musco S, Bove P. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation effects on detrusor overactivity incontinence are not due to a placebo effect: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2010 Nov;184(5):2001-6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.113. Epub 2010 Sep 20. PMID: 20850833.

- 10 - O'Sullivan H, Kelly G, Toale J, Cascio S. Comparing the outcomes of parasacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunction in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021 Feb;40(2):570-581. doi: 10.1002/nau.24601. Epub 2021 Jan 7. PMID: 33410536.

- 11 - Quintiliano F, Veiga ML, Moraes M, Cunha C, de Oliveira LF, Lordelo P, Bastos Netto JM, Barroso Júnior U. Transcutaneous parasacral electrical stimulation vs oxybutynin for the treatment of overactive bladder in children: a randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2015 May;193(5 Suppl):1749-53. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.12.001. Epub 2015 Mar 24. PMID: 25813563.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Borch, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Denmark

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: -Age 5 to 14 years -More than 4 micturitions per day -Normal physical examination Exclusion criteria: - Anatomical abnormalities of the urinary or gastrointestinal tract -Ongoing or prior treatment with anticholinergics -Post-void residual urine (PVR) > 20 ml† -Constipation according to Rome III criteria -Recurrent urinary tract infections within the last six months

N total at baseline: Intervention 1: 22 Intervention 2: 21 Intervention 3: 23

* 15 children dropped out during the intervention period, however baseline characteristics are represented without data of drop outs Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I1: 7.65 ± 1.77 I2: 7.47 ± 1.61 Sex: I1: 61% M I2: 100% M I3: 71% M P= 0.02 I2: 5.57 ± 1.22 I3: 4.79 ± 1.72 P= 0.01 Severity of incontinence (Dry-pie score): I2: 8.26 ± 3.63 I3: 8.14 ± 3.92 I2: 7.74 ± 2.10 I3: 7.23 ± 2.59 Groups comparable at baseline? Comparable at baseline, except sex and number of wet days/week. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I1: TENS + oxybutynin I2: TENS + placebo oxybutynin

TENS treatment: Oxybutynin treatment: *For the current analysis of literature only intervention 2 and 3 are considered relevant.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

|

Length of follow-up: 10-week intervention period, last evaluation at 11 weeks.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention 1: N (%) 4 (18) Reasons (describe) 1x postvoid residual (PVR) of 73ml 2x lack of compliance 1x moved out of study area Intervention 2: N (%) 2 (9.5) Reasons (describe) 1x lack of compliance

N (%) 9 (39) Reasons (describe) 7x PVR (mean ± SD 62 ± 34ml) Incomplete outcome data: Some outcomes are not reported fully, with data only presented graphically or for significant results only (for example, significant mean differences for number of wet days/week, severity of UI and frequency only reported for comparison of active TENS and oxybutynin vs TENS and placebo).

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Outcome 1: Treatment effect No of wet days/week:

Outcome 2: Cost-effectiveness Not reported

Outcome 3: Complications I1: None reported I2: 1x appendicitis

|

High rate of attrition, with uneven numbers between groups.

Selective outcome reporting. Outcomes are not fully reported for all interventions. Only significant results are presented.

The authors conclude: TENS in combination with oxybutynin for UI in children was superior to TENS or oxybutynin monotherapy when using intention to treat analysis. The main synergistic effect seemed to be significant reduction of oxybutynin induced side effects, ie PVR. Combination therapy with TENS and oxybutynin should be considered as second-line treatment in children with UI that is refractory to standard urotherapy and in children who experience oxybutynin induced PVR.

|

|

Casal-Beloy, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Spain

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: -Age 5 to y 16 years Exclusion criteria: -Diagnosis of an organic pathology that could justify the symptoms of OAB -Persistent constipation despite the initial measures -Flowmetry with a pathological curve during the initial study of daytime conditions (with electrical activity during urination or flat curve) -A high post-void residue (volume over 10% of bladder capacity expected for age or greater than 20 ml). -Patients who received pharmacological treatment for OAB 6 months before taking part in the study

N total at baseline: Intervention: 41 Control: 48

Important prognostic factors2:

I: 9 (7 to 12) C: 8 (7 to 15.5)

Sex: I: 35% M C: 45.5% M

I: C: Y: 91.3% (n=42)

Voiding frequency: C: 9 (8 to 12)

I: 18 (14 to 20) C: 17 (13 to 21)

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): TENS

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Oxybutynin

|

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) 1 (2.4) Reasons (describe) Discontinued treatment during follow-up Control: N (%) 2 (4.2) Reasons (describe) Rejected participation

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Outcome 1: Treatment effect Success rate (defined as complete and partial response): Voiding frequency after treatment (n/day) median (IQR): Mean voided volume (ml) median (IQR): Max voided volume (ml median (IQR)): DVSS score Urgency (% of patients where urgency disappeared after treatment) Daytime incontinence (% of patients where daytime urinary incontinence disappeared after treatment) Outcome 2: Cost-effectiveness Not reported

Outcome 3: Complications Complication rate: C: 26.1% I: Dermatitis in the sacral region (n=1) Fecal losses (n=5) Urgency (n=5) C: Constipation (n=6) Abdominal pain (n=2) Dry mouth (n=2) Increased post void residual (n=2) |

The authors conclude:

Both Oxybutynin and home TENS are effective therapeutic alternatives in the management of pediatric OAB. Nontheless, electrotherapy was significantly more effective than oxybutynin in the treatment of the OAB, with a higher percentage of complete resolution of symptoms and a lower rate of adverse effects. For these reasons TENS appears to be a safer and more effective alternative to oxybutynin in the management of pediatric patients with OAB. Therefore, after the application of standard urotherapy and the management of constipation, TENS therapy should be considered the first line of treatment for pediatric OAB.

|

|

Dos-Reis, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Hospital, monocenter, Brazil

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: -Children diagnosed with primary non-monosymptomatic enuresis between August 2012 and August 2014 -Aged 5 to 16 years

Exclusion criteria: -monosymptomatic enuresis - neurological diseases - abnormalities of the urinary tract - psychiatric diseases

N total at baseline: 77, 13 lost to follow-up. Data available from 64 children: I: 31

Important prognostic factors2:

Age: I: 9.19 ± 2.41

Sex (Male) %: I: 32.3

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Standard urotherapy was performed in both treatment groups.

Biofeedback:

Biofeedback sessions (animated with a graphic layout on a computer screen) were performed in the hospital, twice a week for 20 minutes per session. The number of sessions varied according to the progress of the treatment, with a maximum of 20 sessions. |

Describe control:

|

Length of follow-up:

6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 13, it was not reported from which treatment group

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Outcome 1: Treatment effect Success rate (defined as complete resolution of symptoms) %: Resolution of urgency (%): I: 89.4

Maximum flow (change): I: 6,28 ml (p=<0.001)

DVSS score (change): Ns between groups.

Outcome 3: Complications Not reported

|

The authors conclude:

Both biofeedback and the parassacral TENS were found to be equally effective for treating primary non-monosymptomatic enuresis. They are effective in cases with the prevalence of OAB as well as in cases of DV. |

|

Quintiliano, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Brazil Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: -Age 4 to 7 years old -Bell-shaped uroflowmetry curve -Post-void residual urine volume less than 10% of bladder capacity expected for age or greater than 20ml -DVSS greater than normal (6 in boys and 9 in girls) -Voiding urgency at least three times per week -No previous treatment

Exclusion criteria: - Signs of neurological disease -Urinary tract anatomical problems

N total at baseline: Intervention: 13 Control: 15

Important prognostic factors2:

I: 6.3 ± 2.4 C: 6.5 ± 2.0

Sex: I: 31% M C: 33% M

Voiding frequency: C: 8.5 ± 3.5

I: 11 ± 2.2 C: 12.2 ± 2.9

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): PTENS and placebo drug

Use of PTENS 20 sessions of 20 minutes each 3 times per week on alternate days. Intensity increased to threshold

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): Oxybutynin and sham scapular electrical therapy

0.3 mg/kg per day, twice daily |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) 3 (23) Reasons (describe) Fever and redness

Control: N (%) 0 (0) Reasons (describe) -

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Outcome 1: Treatment effect Success rate (defined as complete resolution of symptoms): Voiding frequency after treatment (n/day) Mean ± SD: C: 5.4 ± 2.1 ns Mean voided volume (ml) Mean ± SD: C: 152.1 ± 49.8

Max voided volume (ml) C: 239.1 ± 68.5 DVSS score C: 3.6 ± 1.8

Outcome 3: Complications Complication rate: C: unclear I: None reported C: Dry mouth (n=9) Hyperthermia (n=4) Hyperemia (n=7) |

The authors conclude:

PTENS and oxybutynin were similarly efficacious for treating OAB in children. Oxybutynin was more effective in decreasing voiding frequency and PTENS was more effective in improving constipation. Detectable side effects developed only in children who received oxybutynin. Each method was well accepted by families.

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Alcantara AC, Mello MJ, Costa e Silva EJ, Silva BB, Ribeiro Neto JP. Transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation for the treatment of urinary urgency or urge-incontinence in children and adolescents: a Phase II clinica. J Bras Nefrol. 2015 Jul-Sep;37(3):422-6. English, Portuguese. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20150065. PMID: 26398655. |

No comparison, results of a clinical trial where patients received TENS |

|

Astasio-Picado Á, García-Cano M. Neuromodulation of the Posterior Tibial Nerve for the Control of Urinary Incontinence. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Mar 17;58(3):442. doi: 10.3390/medicina58030442. PMID: 35334618; PMCID: PMC8955811. |

Wrong population, adults |

|

Bagińska J, Sadowska E, Korzeniecka-Kozerska A. An Examination of the Relationship between Urinary Neurotrophin Concentrations and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) Used in Pediatric Overactive Bladder Therapy. J Clin Med. 2021 Jul 17;10(14):3156. doi: 10.3390/jcm10143156. PMID: 34300322; PMCID: PMC8305382. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Bani-Hani AH, Vandersteen DR, Reinberg YE. Neuromodulation in pediatrics. Urol Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;32(1):101-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2004.09.002. PMID: 15698882. |

Narrative review |

|

Barroso U Jr, Lordêlo P, Lopes AA, Andrade J, Macedo A Jr, Ortiz V. Nonpharmacological treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunction using biofeedback and transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a pilot study. BJU Int. 2006 Jul;98(1):166-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06264.x. PMID: 16831163. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Barroso U Jr, Tourinho R, Lordêlo P, Hoebeke P, Chase J. Electrical stimulation for lower urinary tract dysfunction in children: a systematic review of the literature. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011 Nov;30(8):1429-36. doi: 10.1002/nau.21140. Epub 2011 Jun 29. PMID: 21717502. |

Most studies in SR were non comparative, those that were do not match PICO |

|

Barroso U Jr, Viterbo W, Bittencourt J, Farias T, Lordêlo P. Posterior tibial nerve stimulation vs parasacral transcutaneous neuromodulation for overactive bladder in children. J Urol. 2013 Aug;190(2):673-7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.034. Epub 2013 Feb 16. PMID: 23422257. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Barroso U Jr, Carvalho MT, Veiga ML, Moraes MM, Cunha CC, Lordêlo P. Urodynamic outcome of parasacral transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation for overactive bladder in children. Int Braz J Urol. 2015 Jul-Aug;41(4):739-43. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2014.0303. PMID: 26401867; PMCID: PMC4757003. |

No comparison |

|

Barroso U Jr, de Azevedo AR, Cabral M, Veiga ML, Braga AANM. Percutaneous electrical stimulation for overactive bladder in children: a pilot study. J Pediatr Urol. 2019 Feb;15(1):38.e1-38.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.10.001. Epub 2018 Oct 11. PMID: 30414712. |

Wrong study design & no comparison |

|

Barroso U Jr, Lordêlo P. Electrical nerve stimulation for overactive bladder in children. Nat Rev Urol. 2011 Jun 7;8(7):402-7. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.68. PMID: 21647183. |

Wrong study design |

|

Borch L, Rittig S, Kamperis K, Mahler B, Djurhuus JC, Hagstroem S. No immediate effect on urodynamic parameters during transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in children with overactive bladder and daytime incontinence-A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017 Sep;36(7):1788-1795. doi: 10.1002/nau.23179. Epub 2016 Nov 21. PMID: 27868230. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Boswell TC, Hollatz P, Hutcheson JC, Vandersteen DR, Reinberg YE. Device outcomes in pediatric sacral neuromodulation: A single center series of 187 patients. J Pediatr Urol. 2021 Feb;17(1):72.e1-72.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.10.010. Epub 2020 Oct 16. PMID: 33129672. |

No comparison |

|

Bower WF, Moore KH, Adams RD. A pilot study of the home application of transcutaneous neuromodulation in children with urgency or urge incontinence. J Urol. 2001 Dec;166(6):2420-2. PMID: 11696802. |

No comparison |

|

Bower WF, Yeung CK. A review of non-invasive electro neuromodulation as an intervention for non-neurogenic bladder dysfunction in children. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23(1):63-7. doi: 10.1002/nau.10171. PMID: 14694460. |

Wrong study design |

|

Buckley BS, Sanders CD, Spineli L, Deng Q, Kwong JS. Conservative interventions for treating functional daytime urinary incontinence in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Sep 18;9(9):CD012367. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012367.pub2. PMID: 31532563; PMCID: PMC6749940. |

Two out of 6 included RCT’s match PICO, these were separately included in the analysis of literature |

|

Capitanucci ML, Camanni D, Demelas F, Mosiello G, Zaccara A, De Gennaro M. Long-term efficacy of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for different types of lower urinary tract dysfunction in children. J Urol. 2009 Oct;182(4 Suppl):2056-61. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.007. Epub 2009 Aug 20. PMID: 19695611. |

No comparison |

|

Casal-Beloy I, García-Novoa MA, Casal Beloy T, García-González M, Somoza Argibay I. [Sacral electrical neurostimulation in the refractory pediatric overactive bladder]. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2020 Dec 22;43(3):417-421. Spanish. doi: 10.23938/ASSN.0879. PMID: 33180057. |

Wrong study design, wrong language |

|

Casal Beloy I, García-Novoa MA, García González M, Somoza Argibay I. Update on sacral neuromodulation and overactive bladder in pediatrics: A systematic review. Arch Esp Urol. 2021 Sep;74(7):699-708. English, Spanish. PMID: 34472439. |

Wrong language |

|

Chen H, Wu XF, Jin XY, Liu H. A pilot study of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with treatment resistant detrusor in stability. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2003;7(29): 3980-3981 |

Wrong language |

|

Clark C, Ngo T, Comiter CV, Anderson R, Kennedy W. Sacral nerve stimulator revision due to somatic growth. J Urol. 2011 Oct;186(4 Suppl):1576-80. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.098. Epub 2011 Aug 19. PMID: 21855923. |

No comparison |

|

de Abreu GE, de Souza LA, da Fonseca MLV, Barbosa TBC, de Mello ERD, Nunes ANB, Barroso UO Jr. Parasacral Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for the Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Bladder and Bowel Dysfunction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Urol. 2021 Jun;205(6):1785-1791. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001579. Epub 2021 Feb 2. PMID: 33525925. |

Wrong intervention |

|

de Azevedo RV, Oliveira EA, Vasconcelos MM, de Castro BA, Pereira FR, Duarte NF, de Jesus PM, Vaz GT, Lima EM. Impact of an interdisciplinary approach in children and adolescents with lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD). J Bras Nefrol. 2014 Oct-Dec;36(4):451-9. English, Portuguese. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20140065. PMID: 25517273. |

No comparison |

|

De Gennaro M, Capitanucci ML, Mastracci P, Silveri M, Gatti C, Mosiello G. Percutaneous tibial nerve neuromodulation is well tolerated in children and effective for treating refractory vesical dysfunction. J Urol. 2004 May;171(5):1911-3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000119961.58222.86. PMID: 15076308. |

No comparison |

|

de Paula LIDS, de Oliveira LF, Cruz BP, de Oliveira DM, Miranda LM, de Moraes Ribeiro M, Duque RO, de Figueiredo AA, de Bessa J Jr, Netto JMB. Parasacral transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation (PTENS) once a week for the treatment of overactive bladder in children: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Urol. 2017 Jun;13(3):263.e1-263.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.11.019. Epub 2016 Dec 21. Erratum in: J Pediatr Urol. 2021 Jun;17(3):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.03.015. PMID: 28089606. |

Wrong comparison |

|

de Paula LIDS, de Oliveira LF, Cruz BP, de Oliveira DM, Miranda LM, de Moraes Ribeiro M, Duque RO, Figueiredo AA, de Bessa J Jr, Netto JMB. Corrigendum to "Parasacral transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation (PTENS) once a week for the treatment of overactive bladder in children: A randomized controlled trialˮ [J Pediatr Urol 13 (2017) 263.e1-236.e6]. J Pediatr Urol. 2021 Jun;17(3):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.03.015. Epub 2021 Apr 8. Erratum for: J Pediatr Urol. 2017 Jun;13(3):263.e1-263.e6. PMID: 33839035. |

Wrong comparison, addition to other article of the same group |

|

De Wall LL, Bekker AP, Oomen L, Janssen VACT, Kortmann BBM, Heesakkers JPFA, Oerlemans AJM. Posterior Tibial Nerve Stimulation in Children with Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Experiences, Quality of Life and Treatment Effect. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jul 25;19(15):9062. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159062. PMID: 35897438; PMCID: PMC9331059. |

No comparison |

|

Dos Santos J, Marcon E, Pokarowski M, Vali R, Raveendran L, O'Kelly F, Amirabadi A, Elterman D, Foty R, Lorenzo A, Koyle M. Assessment of Needs in Children Suffering From Refractory Non-neurogenic Urinary and Fecal Incontinence and Their Caregivers' Needs and Attitudes Toward Alternative Therapies (SNM, TENS). Front Pediatr. 2020 Sep 9;8:558. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00558. PMID: 33014941; PMCID: PMC7509042. |

Wrong study design |

|

Dwyer ME, Vandersteen DR, Hollatz P, Reinberg YE. Sacral neuromodulation for the dysfunctional elimination syndrome: a 10-year single-center experience with 105 consecutive children. Urology. 2014 Oct;84(4):911-7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.03.059. Epub 2014 Aug 2. PMID: 25096339. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Ebert, K. M., & Alpert, S. A. (2018). Sacral neuromodulation: Improving bladder and bowel dysfunction in children. Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics, 4, 24-36. |

No comparison |

|

Ebert KM, Terry H, Ching CB, Dajusta DG, Fuchs ME, Jayanthi VR, McLeod DJ, Alpert SA. Effectiveness of a Practical, At-Home Regimen of Parasacral Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation in Pediatric Overactive Bladder. Urology. 2022 Jul;165:294-298. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2022.01.017. Epub 2022 Jan 21. PMID: 35065988. |

No comparison |

|

Everaert K, Van den Hombergh U. Sacral nerve stimulation for pelvic floor and bladder dysfunction in adults and children. Neuromodulation. 2005 Jul;8(3):186-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2005.05237-4.x. PMID: 22151491. |

No comparison |

|

Fernández-Pineda I, Pérez Espejo MP, Fernández Hurtado MA, Barrero Candau R, García Merino F. Biofeedback y electroestimulación como tratamiento de la enuresis no monosintomática [Biofeedback and electrostimulation in the treatment of non monosymptomatic enuresis]. Cir Pediatr. 2008 Apr;21(2):89-91. Spanish. PMID: 18624276. |

No comparison |

|

Fernandez N, Chua ME, Ming JM, Silangcruz JM, Zu'bi F, Dos Santos J, Lorenzo AJ, Braga LH, Lopes RI. Neurostimulation Therapy for Non-neurogenic Overactive Bladder in Children: A Meta-analysis. Urology. 2017 Dec;110:201-207. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.08.003. Epub 2017 Aug 17. PMID: 28823638. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Fox JA, Reinberg YE. Incontinence. Pediatric sacral neuromodulation for refractory incontinence. Nat Rev Urol. 2010 Sep;7(9):482-3. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.137. PMID: 20818324. |

No abstract |

|

Fuchs, M. E., & Alpert, S. A. (2016). Sacral Neuromodulation for Bladder Dysfunction in Children: Indications, Results and Complications. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports, 11, 195-200. |

No comparison |

|

Gaziev G, Topazio L, Iacovelli V, Asimakopoulos A, Di Santo A, De Nunzio C, Finazzi-Agrò E. Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation (PTNS) efficacy in the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunctions: a systematic review. BMC Urol. 2013 Nov 25;13:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-13-61. PMID: 24274173; PMCID: PMC4222591. |

Half of the included studies wrong P. Other half wrong comparison. |

|

Ghijselings L, Renson C, Van de Walle J, Everaert K, Spinoit AF. Clinical efficacy of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) versus sham therapy (part I) and TTNS versus percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) (part II) on the short term in children with the idiopathic overactive bladder syndrome: protocol for part I of the twofold double-blinded randomized controlled TaPaS trial. Trials. 2021 Apr 2;22(1):247. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05117-8. PMID: 33810804; PMCID: PMC8017511. |

Wrong study design |

|

Groen LA, Hoebeke P, Loret N, Van Praet C, Van Laecke E, Ann R, Vande Walle J, Everaert K. Sacral neuromodulation with an implantable pulse generator in children with lower urinary tract symptoms: 15-year experience. J Urol. 2012 Oct;188(4):1313-7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.039. Epub 2012 Aug 16. PMID: 22902022. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Haddad M, Besson R, Aubert D, Ravasse P, Lemelle J, El Ghoneimi A, Moscovici J, Hameury F, Baumstarck-Barrau K, Hery G, Guys JM. Sacral neuromodulation in children with urinary and fecal incontinence: a multicenter, open label, randomized, crossover study. J Urol. 2010 Aug;184(2):696-701. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.054. Epub 2010 Jun 18. PMID: 20561645. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Hoebeke P, Renson C, Petillon L, Vande Walle J, De Paepe H. Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with therapy resistant nonneuropathic bladder sphincter dysfunction: a pilot study. J Urol. 2002 Dec;168(6):2605-7; discussion 2607-8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64227-9. PMID: 12441995. |

No comparison |

|

Hoebeke P, Van Laecke E, Everaert K, Renson C, De Paepe H, Raes A, Vande Walle J. Transcutaneous neuromodulation for the urge syndrome in children: a pilot study. J Urol. 2001 Dec;166(6):2416-9. PMID: 11696801. |

No comparison |

|

Hoffmann A, Sampaio C, Nascimento AA, Veiga ML, Barroso U. Predictors of outcome in children and adolescents with overactive bladder treated with parasacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. J Pediatr Urol. 2018 Feb;14(1):54.e1-54.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.07.017. Epub 2017 Sep 8. PMID: 28974365. |

No comparison |

|

Hua C, Wen Y, Zhang Y, Feng Q, He X, Li Y, Wu J, Feng J, Bauer SB, Wen J. The value of synchro-cystourethrometry for evaluating the relationship between urethral instability and overactive bladder. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018 Mar;50(3):441-449. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1783-8. Epub 2018 Jan 3. PMID: 29299824. |

No comparison |

|

Humphreys MR, Vandersteen DR, Slezak JM, Hollatz P, Smith CA, Smith JE, Reinberg YE. Preliminary results of sacral neuromodulation in 23 children. J Urol. 2006 Nov;176(5):2227-31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.013. PMID: 17070300. |

No comparison |

|

Ibrahim, H., Shouman, A. M., Ela, W., Ghoneima, W., Shoukry, A. I., ElSheemy, M., ... & Kotb, S. (2019). Percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation for the treatment of the overactive bladder in children: Is it effective?. African Journal of Urology, 25, 1-5. |

No comparison |

|

Ismail, M. B., & Abdullhussein, W. Q. (2021). The safety and efficacy of sacral neuromodulation on refractory urgency urinary and fecal incontinence in Iraqi patients. Prof.(Dr) RK Sharma, 21(1), 575. |

Wrong P, adults |

|

Jafarov R, Ceyhan E, Kahraman O, Ceylan T, Dikmen ZG, Tekgul S, Dogan HS. Efficacy of transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in children with functional voiding disorders. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021 Jan;40(1):404-411. doi: 10.1002/nau.24575. Epub 2020 Nov 18. PMID: 33205852. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Johnston, A. W., & Whittam, B. M. (2022). Pediatric Overactive Bladder and the Role of Sacral Neuromodulation. Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics, 8(4), 412-422. |

Wrong study design |

|

Kajbafzadeh AM, Sharifi-Rad L, Ladi-Seyedian SS, Mozafarpour S. Transcutaneous interferential electrical stimulation for the management of non-neuropathic underactive bladder in children: a randomised clinical trial. BJU Int. 2016 May;117(5):793-800. doi: 10.1111/bju.13207. Epub 2015 Jul 18. PMID: 26086897. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Khodorovskaya, A. M., Novikov, V. A., Zvozil, A. V., Umnov, V. V., Umnov, D. V., Zharkov, D. S., & Vissarionov, S. V. (2022). Sacral neuromodulation in pediatric bladder and bowel dysfunctions: Literature review. Pediatric Traumatology, Orthopaedics and Reconstructive Surgery, 10(4), 459-470. |

No comparison |

|

Ladi-Seyedian SS, Sharifi-Rad L, Kajbafzadeh AM. Pelvic floor electrical stimulation and muscles training: a combined rehabilitative approach for management of non-neuropathic urinary incontinence in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2019 Apr;54(4):825-830. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.06.007. Epub 2018 Jun 11. PMID: 29960741. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Leão S Santos H, Caldwell P, Hussong J, von Gontard A, Estevam de Abreu G, Braga AA, Veiga ML, Hamilton S, Deshpande A, Barroso U. Quality of life and psychological aspects in children with overactive bladder treated with parasacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation - A prospective multicenter study. J Pediatr Urol. 2022 Dec;18(6):739.e1-739.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.10.011. Epub 2022 Oct 8. PMID: 36336620. |

No comparison |

|

Lordêlo P, Soares PV, Maciel I, Macedo A Jr, Barroso U Jr. Prospective study of transcutaneous parasacral electrical stimulation for overactive bladder in children: long-term results. J Urol. 2009 Dec;182(6):2900-4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.058. Epub 2009 Oct 28. PMID: 19846164. |

No comparison |

|

Malm-Buatsi E, Nepple KG, Boyt MA, Austin JC, Cooper CS. Efficacy of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with overactive bladder refractory to pharmacotherapy. Urology. 2007 Nov;70(5):980-3. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1109. Epub 2007 Oct 24. PMID: 17919697. |

No comparison |

|

Martínez-Pizarro, S. (2021). Parasacral transcutaneous stimulation to treat overactive bladder in children Estimulación transcutánea parasacral para tratar la vejiga hiperactiva en niños. Revista Mexicana de Urología, 81(1), 1-4. |

Wrong study design |

|

Mason MD, Stephany HA, Casella DP, Clayton DB, Tanaka ST, Thomas JC, Adams MC, Brock JW 3rd, Pope JC 4th. Prospective Evaluation of Sacral Neuromodulation in Children: Outcomes and Urodynamic Predictors of Success. J Urol. 2016 Apr;195(4 Pt 2):1239-44. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.11.034. Epub 2016 Feb 28. PMID: 26926536. |

No comparison |

|

McGee SM, Routh JC, Granberg CF, Roth TJ, Hollatz P, Vandersteen DR, Reinberg Y. Sacral neuromodulation in children with dysfunctional elimination syndrome: description of incisionless first stage and second stage without fluoroscopy. Urology. 2009 Mar;73(3):641-4; discussion 644. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.10.067. Epub 2009 Jan 23. PMID: 19167048. |

Wrong intervention (operative techniques) |

|

Nacif A, de Abreu GE, Bessa Junior J, Veiga ML, Barroso U. Agreement between the visual analogue scale (VAS) and the dysfunctional voiding scoring system (DVSS) in the post-treatment evaluation of electrical nerve stimulation in children and adolescents with overactive bladder. J Pediatr Urol. 2022 Dec;18(6):740.e1-740.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.07.032. Epub 2022 Aug 3. PMID: 36123285. |

Wrong comparison |

|

O'Sullivan H, Kelly G, Toale J, Cascio S. Comparing the outcomes of parasacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunction in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021 Feb;40(2):570-581. doi: 10.1002/nau.24601. Epub 2021 Jan 7. PMID: 33410536. |

Two out of 6 included RCT’s match PICO, these were separately included in the analysis of literature |

|

Pedersen N, Breinbjerg A, Thorsteinsson K, Hagstrøm S, Rittig S, Kamperis K. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation as add-on therapy in children receiving anticholinergics and/or mirabegron for refractory daytime urinary incontinence: A retrospective cohort study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2022 Jan;41(1):275-280. doi: 10.1002/nau.24812. Epub 2021 Oct 7. PMID: 34618378. |

No comparison |

|

Qiu S, Bi S, Lin T, Wu Z, Jiang Q, Geng J, Liu L, Bao Y, Tu X, He M, Yang L, Wei Q. Comparative assessment of efficacy and safety of different treatment for de novo overactive bladder children: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Asian J Urol. 2019 Oct;6(4):330-338. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2019.04.001. Epub 2019 Apr 13. PMID: 31768318; PMCID: PMC6872791. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Rashid, S., Rabani, M. W., Khawaja, A. A., Arshad, M. S., & Sarwar, K. (2011). Efficacy of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) therapy in overactive non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder (Hinman's Syndrome). Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 27(3). |

Wrong comparison |

|

Roth TJ, Vandersteen DR, Hollatz P, Inman BA, Reinberg YE. Sacral neuromodulation for the dysfunctional elimination syndrome: a single center experience with 20 children. J Urol. 2008 Jul;180(1):306-11; discussion 311. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.033. Epub 2008 May 21. PMID: 18499169. |

No comparison |

|

Santana JC, Veiga ML, Braga AANM, Boa Sorte N, Barroso U Jr. Time until maximum flow rate uroflowmetry: A new parameter for predicting failure of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in treating children and adolescents with overactive bladder. J Pediatr Urol. 2021 Aug;17(4):472.e1-472.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.05.011. Epub 2021 Jun 11. PMID: 34229976. |

No comparison |

|

Schober MS, Sulkowski JP, Lu PL, Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Teich S, Alpert SA. Sacral Nerve Stimulation for Pediatric Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction: Development of a Standardized Pathway with Objective Urodynamic Outcomes. J Urol. 2015 Dec;194(6):1721-6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.06.090. Epub 2015 Jun 30. PMID: 26141849. |

No comparison |

|

Sharifi-Rad L, Ladi Seyedian SS, Fatemi-Behbahani SM, Lotfi B, Kajbafzadeh AM. Impact of transcutaneous interferential electrical stimulation for management of primary bladder neck dysfunction in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2020 Feb;16(1):36.e1-36.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.10.004. Epub 2019 Oct 18. PMID: 31735518. |

No comparison |

|

Sharifi-Rad L, Ladi-Seyedian SS, Kajbafzadeh AM. Interferential Electrical Stimulation Efficacy in the Management of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Children: A Review of the Literature. Urol J. 2021 Jul 22;18(5):469-476. doi: 10.22037/uj.v18i.6558. PMID: 34291442. |

No comparison |

|

Sharifiaghdas F, Mirzaei M, Ahadi B. Percutaneous nerve evaluation (PNE) for treatment of non-obstructive urinary retention: urodynamic changes, placebo effects, and response rates. Urol J. 2014 Mar 4;11(1):1301-7. PMID: 24595941. |

No comparison |

|

Sillén U, Arwidsson C, Doroszkiewicz M, Antonsson H, Jansson I, Stålklint M, Abrahamsson K, Sjöström S. Effects of transcutaneous neuromodulation (TENS) on overactive bladder symptoms in children: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Urol. 2014 Dec;10(6):1100-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.03.017. Epub 2014 May 9. PMID: 24881806. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Strine, A. C., Keenan, A. C., King, S., & Whittam, B. M. (2015). Sacral neuromodulation in children. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports, 10, 332-337. |

Wrong study design |

|

Sulkowski JP, Nacion KM, Deans KJ, Minneci PC, Levitt MA, Mousa HM, Alpert SA, Teich S. Sacral nerve stimulation: a promising therapy for fecal and urinary incontinence and constipation in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Oct;50(10):1644-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.03.043. Epub 2015 Mar 26. PMID: 25858097. |

No comparison |

|

Toale J, Kelly G, Hajduk P, Cascio S. Assessing the outcomes of parasacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PTENS) in the treatment of enuresis in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Neurourol Urodyn. 2022 Nov;41(8):1659-1669. doi: 10.1002/nau.25039. Epub 2022 Sep 7. PMID: 36069167. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Tong, C. M. C., & Kitchens, D. M. (2023). Neuromodulation for Treatment of Refractory Non-neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Children: an Overview. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports, 18(1), 59-63. |

Wrong study design |

|

Trachta J, Wachter J, Kriz J. Chronic Urinary Retention due to Fowler's Syndrome. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2018 Jan;6(1):e77-e80. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1672147. Epub 2018 Oct 18. PMID: 30473987; PMCID: PMC6193800. |

Wrong study design |

|

Tugtepe H, Thomas DT, Ergun R, Kalyoncu A, Kaynak A, Kastarli C, Dagli TE. The effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation therapy in patients with urinary incontinence resistant to initial medical treatment or biofeedback. J Pediatr Urol. 2015 Jun;11(3):137.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.10.016. Epub 2015 Mar 12. PMID: 25824876. |

No comparison |

|

Unknown. TENS Effective in Children With Overactive Bladder. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2010;102(11):1108-1109 |

Wrong study design |

|

Veiga ML, Oliveira K, Batista V, Nacif A, Braga AAM, Barroso U Jr. Parasacral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with overactive bladder: comparison between sessions administered two and three times weekly. Int Braz J Urol. 2021 Jul-Aug;47(4):787-793. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2020.0372. PMID: 33848070; PMCID: PMC8321474. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Veiga ML, Queiroz AP, Carvalho MC, Braga AA, Sousa AS, Barroso U Jr. Parasacral transcutaneous electrical stimulation for overactive bladder in children: An assessment per session. J Pediatr Urol. 2016 Oct;12(5):293.e1-293.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.03.011. Epub 2016 Apr 16. PMID: 27142765. |

No comparison |

|

Wang ZH, Liu ZH. Treatment for overactive bladder: A meta-analysis of tibial versus parasacral neuromodulation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Oct 14;101(41):e31165. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000031165. PMID: 36253991; PMCID: PMC9575790. |

Wrong P, adults |

|

Wright AJ, Haddad M. Electroneurostimulation for the management of bladder bowel dysfunction in childhood. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017 Jan;21(1):67-74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2016.05.012. Epub 2016 May 27. PMID: 27328864. |

Wrong study design |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 17-07-2025

Algemene gegevens