High flex of conventionele knieprothese

Uitgangsvraag

Welk type knieprothese verdient de voorkeur: “high flex knieprothese” of conventionele knieprothese?

Aanbeveling

Er bestaat geen voorkeur voor het gebruik van de high-flex of conventionele totale knieprothese.

Overwegingen

Zowel uit de literatuur als uit de ervaringen uit de dagelijkse praktijk blijkt dat de klinische resultaten van de high-flex totale knieprothese vergelijkbaar zijn met die van de conventionele totale knieprothese. De high-flex TKP heeft een vergelijkbaar klinisch resultaat, in termen van kniefunctie, pijnklachten, patiënttevredenheid en complicaties.

De high-flex TKP biedt een, in vergelijking tot een standaard knieprothese, marginaal hoger bewegingsbereik. Uit de literatuuranalyse blijkt dat bij de high-flex knieprothese, de flexie van de knie weliswaar toeneemt, maar de toename gering is en waarschijnlijk klinisch niet relevant. Dat met een high-flex TKP een significante postoperatieve diepere flexie mogelijk is zoals bij de introductie van dit type prothese werd aangegeven (155 in plaats van 120 graden), is naar de mening van de werkgroep niet aantoonbaar.

Het is onjuist om dit type prothese op die gronden te promoten bij de veeleisende actieve en steeds jonger wordende patiënt met artrose van de knie. Het mogelijk beoogde voordeel van een veilige diepe flexie, waarbij door toename van het contactoppervlak minder hoge piekbelasting zou ontstaan op de achterzijde van de insert is in potentie een sterk argument om te kiezen voor een high-flex TKP. Om dit aan te tonen zou er een significant verschil in survival moeten worden bewezen als gevolg van de verminderde slijtage (wear) van de posterieure insert.

Echter, middellange termijn resultaten zijn schaars, en lange termijn resultaten onbekend. In de enige studie met een follow-up van tenminste tien jaar (Kim 2012) wordt geen statistisch significant verschil gemeten in overleving tussen high-flex en standaard knieprothese, maar de omvang (power) van deze studie is onvoldoende. Op dit moment kan slechts geconcludeerd worden dat met de huidige (korte) follow-up de high-flex TKP een vergelijkbare levensduur lijkt te hebben als de conventionele TKP.

Uit de literatuuranalyse kunnen geen conclusies worden getrokken met betrekking tot de kosteneffectiviteit van het gebruik van de high-flex TKP. Kosten van de prothese en operatietijd zijn vergelijkbaar. Het is maar de vraag of elke doorontwikkeling in prothese design, met de daarbij vaak toegenomen kosten, zich laat vertalen in een beter klinisch resultaat voor de patiënt met knie artrose.

Alles aanschouwend is op grond van de huidige kennis uit de relevante literatuur en de expert-opinie van de werkgroep geen voorkeur uit te spreken voor het gebruik van de high-flex totale knieprothese, ten opzichte van de conventionele totale knieprothese.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De huidige tendens in TKP design is het gebruik van “high flex” totale knieprotheses.

Beoogde voordelen bestaan uit mogelijk grotere postoperatieve flexie ROM en minder impingement en peak belasting van de posterieure femurcondylen bij diepe flexie, met als gevolg minder slijtage (wear) van de posterieure insert.

De meerderheid van de firma’s brengt deze high-flex protheses momenteel op de markt, vaak in combinatie met het “gender knee” concept. In de recente wetenschappelijke literatuur worden wisselende resultaten beschreven ten aanzien van bovengenoemde beoogde effecten.

Voor patiënten en behandelaars is het zeer relevant of het plaatsen van een high-flex knieprothese beter is dan een conventionele prothese. Hiervoor zijn gecontroleerde studies nodig met een lange follow-up. Tenminste zal moeten worden aangetoond dat een high-flex prothese net zo veilig is en niet leidt tot een hoger percentage loslating.

Is er op grond van de huidige literatuur voldoende bewijs voor de keuze voor dit type prothese? Hoe zijn de klinische resultaten vergeleken met de conventionele TKP?

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Matig GRADE |

Een high-flex knieprothese biedt geen klinisch relevant hoger bewegingsbereik dan een standaard knieprothese.

Bronnen: Luo (2011), Choi (2010), Kim (2012), Nutton (2012), Seng (2011), Singh (2011), Hamilton (2011a), Endres (2011) |

|

Matig GRADE |

Een high-flex knieprothese en een standaard knieprothese hebben een vergelijkbaar klinisch resultaat, in termen van kniefunctie, pijnklachten, patiënttevredenheid, milde bijwerkingen en complicaties. Lange termijn resultaten zijn nog grotendeels onbekend.

Bronnen: Luo (2011), Choi (2010), Kim (2012), Nutton (2012), Seng (2011), Singh (2011), Hamilton (2011a), Endres (2011) |

|

Laag GRADE |

Een high-flex knieprothese en standaard knieprothese lijken een vergelijkbare levensduur te hebben op de middellange termijn. Lange termijn resultaten zijn nog onbekend.

Bronnen: Kim (2012) |

Samenvatting literatuur

De systematische review van Luo (2011) is van zeer goede kwaliteit (zie tabel quality assessment for systematic reviews) en includeert vijf RCT’s en zes cohortstudies. De inclusiecriteria en de belangrijkste karakteristieken van de geselecteerde studies zijn te vinden in de evidence-tabel. In alle gevallen gaat het om een primaire knieprothese bij patiënten met ernstige gonartrose, de groepsgrootte varieert tussen elf en negentig patiënten, met een leeftijd van vijfenzestig tot tweeënzeventig jaar. De studieduur varieert tussen één en drie jaar. Een zevental studies betreft kruisbandopofferende knieprotheses (PS, posterior stabilized), en vergelijkt een high-flex met een standaard knieprothese. De overige vier studies vergelijken een high-flex met een standaard ontwerp van een kruisbandsparende knieprothese (CR, cruciate retaining).

Bewegingsbereik van de knie (ROM)

De primaire uitkomstmaat is het bewegingsbereik van de geopereerde knie (ROM, range of motion) aan het einde van de studie. Bij meta-analyse bedraagt het gemiddelde verschil (mean difference, MD) in ROM tussen de high-flex en standaard knieprotheses: PS-Flex versus PS, MD=2,50o (95% betrouwbaarheidsinterval, BI=[1,13; 3,88]; 7 studies, n=370 patiënten) in het voordeel van het high-flex ontwerp; en CR Flex versus CR, MD=2,06o [-0,06; 4,17] (vier studies, n=208), eveneens in het voordeel van het high-flex ontwerp. Als geen onderscheid wordt gemaakt tussen kruisbandsparende en –opofferende knieprotheses is het overall gemiddelde verschil tussen high-flex en standaard ontwerp, MD=2,37o [1,22; 3,53] (n=578; matige statistische heterogeniteit [I2=33%]). Deze meta-analyses geven aan dat het bewegingsbereik van de knie bij gebruik van een high-flex knieprothese hoger is dan bij gebruik van een standaard knieprothese. Het gemiddelde verschil in bewegingsbereik bedraagt echter minder dan 5o en is daarmee klinisch niet relevant.

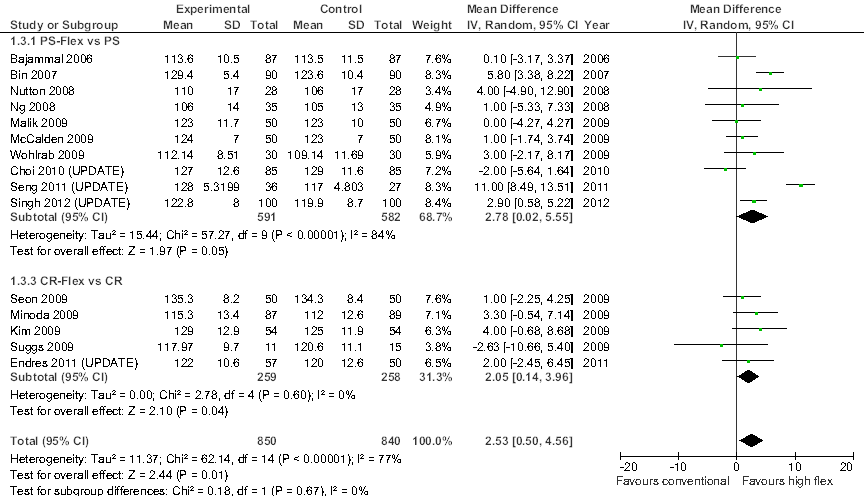

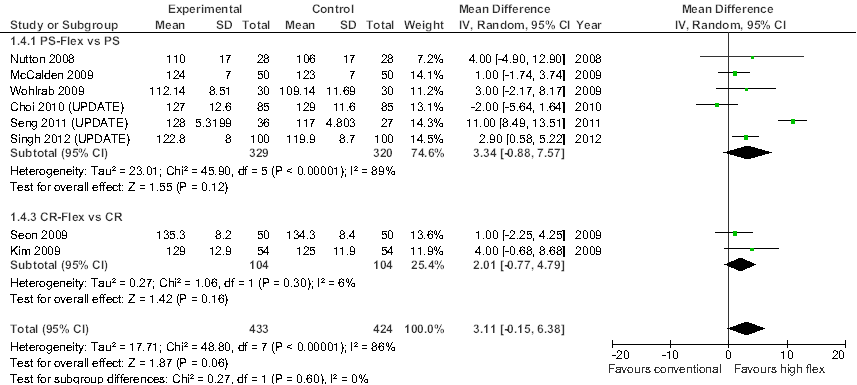

Dit beeld verandert niet na een update van de meta-analyses (Figuur 1.1), of bij exclusie van observationeel onderzoek (Figuur 1.2). Na inclusie van de recentere onderzoeken die de ROM in voldoende detail rapporteren (vier van de zeven studies; Seng et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2011; Endres, 2011; Choi et al., 2010), bedraagt het overall gemiddelde verschil in bewegingsbereik van de knie, MD= 2,53o [0,50; 4,56] (Figuur 1.1; 15 studies, n=840). Inclusie van de recente studies leidt overigens wel tot een aanzienlijke toename in studieheterogeniteit (I2=77%), grotendeels veroorzaakt door de studie van Seng et al (2011). Bij exclusie van observationeel onderzoek, en daarmee beperking van de meta-analyses tot RCT’s, is het overall gemiddelde verschil in bewegingsbereik van de knie, MD= 3,11o [-0,15; 6,38] (Figuur 1.2; acht studies, n=428), een klein en statistisch niet significant verschil in het voordeel van de high-flex prothese.

De drie overige recente studies rapporteren ROM-waardes, maar zonder een maat van betrouwbaarheid (Kim et al., 2012; Hamilton et al., 2011), of vergelijken prothese-ontwerpen die in meer dan één opzicht van elkaar verschillen (Nutton et al., 2012). Kim (2012) richt zich op patiënten die in aanmerking komen voor een bilaterale knieprothese, en randomiseert de linkerknie naar een high-flex of standaard knieprothese, terwijl bij de contralaterale knie het alternatieve ontwerp wordt toegepast. Na een gemiddelde duur van follow-up van ruim tien jaar, wordt geen statistisch significant verschil gemeten in ROM tussen linker- en rechterknie. Dit geldt zowel voor het bewegingsbereik van de belaste als onbelaste knie (high-flex versus standaard; belast, ROM= 121o versus 118o met p=0,18; onbelast, ROM=135o versus 133o met p=0,19). Hamilton (2011) randomiseert patiënten met primaire osteoartritis naar een high-flex of standaard knieprothese (respectievelijk, n= 66 en n=62) en vindt na een gemiddelde follow-up van één jaar, geen verschil in bewegingsbereik van de knie (respectievelijk, ROM= 124,2o en ROM=124,0o; p=0,95). Nutton (2012) randomiseert patiënten naar een kruisbandopofferende high-flex knieprothese of een kruisbandsparende standaard knieprothese (respectievelijk, n= 36 en n=41). Na een gemiddelde follow-up van één jaar, wordt een statistisch significant verschil in bewegingsbereik van de onbelaste knie waargenomen in het voordeel van het kruisbandopofferende high-flex ontwerp (respectievelijk, ROM= 113o [109;117] versus 107o [104;110]; p=0,03). Metingen van het bewegingsbereik van de knie met behulp van electrogoniometrie tijdens diverse loopactiviteiten laten echter geen verhoogde knie flexie zien bij patiënten met de high-flex prothese.

Samenvattend geven bovenstaande studies aan dat bij gebruik van een high-flex knieprothese in plaats van standaard knieprothese, het bewegingsbereik van de knie weliswaar toeneemt, maar de toename gering is en klinisch niet relevant.

Een vergelijkbare conclusie wordt bereikt in de systematische review van Sumino (Sumino et al., 2012), op basis van een vergelijking van de toename in het bewegingsbereik van de knie na plaatsing van een knieprothese (postoperatieve ROM minus preoperatieve ROM). In een meta-analyse bedraagt de gemiddelde toename in ROM bij gebruik van een high-flex of standaard knieprothese, respectievelijk, MD=4,81o [2.01;7,61] (zeven studies; n=502) en 4,70o [2,50;6,91] (16 studies; n=2096]; het verschil in toename in ROM tussen de behandelgroepen is statistisch niet significant. De review is van mindere kwaliteit, met name door inclusie van niet-vergelijkend observationeel onderzoek (zie tabel quality assessment systematic reviews). In een subgroepanalyse concluderen de auteurs dat er onder Westerse patiënten wel sprake zou zijn van een significant grotere toename in bewegingsbereik van de knie bij gebruik van de high-flex prothese (MD=2,75o). Een nadere analyse (zie evidence-tabel) leert echter dat dit verschil in bewegingsbereik statistisch niet significant is.

Kniescores en complicaties

Van de kritische uitkomstmaten worden, naast het bewegingsbereik (ROM), met name samengestelde kniescores (Knee Society Score, KSS; Hospital Specific Score, HSS) en complicaties geanalyseerd. Luo (2011) rapporteert een overall gemiddeld verschil in KSS, MD=1,59 [-0,42; 3,60] in het voordeel van de high-flex prothese (vier studies, n=206). Voor HSS bedraagt dit verschil, MD=0,84 [-0,37; 2,04] (3 studies; n=194). Voor beide kniescores geldt dat de verschillen tussen high-flex en standaard knieprothese klein zijn, statistisch niet significant en klinisch niet relevant. Negen van de elf studies geïncludeerd in Luo (2011) vermelden complicaties (onder andere noodzaak tot revisie, anterieure kniepijn, stijfheid van de knie, radiolucente lijn), er worden geen statistisch relevante verschillen waargenomen tussen de behandelgroepen. Hierbij dient wel rekening te worden gehouden met de korte studieduur van de geïncludeerde onderzoeken (één tot drie jaar), en het feit dat de studieomvang (power) is afgestemd op de primaire uitkomstmaten (ROM, kniescores), en onvoldoende is voor een betrouwbare analyse van zeldzame uitkomsten (ernstige complicaties; noodzaak tot revisie).

Dit beeld verandert niet na een update van de systematische review met de zeven recentere onderzoeken. In de RCT van Kim (2012), worden na een gemiddelde follow-up van 10,3 jaar (range [10,0; 10,6]), geen statistisch significante verschillen gevonden in KSS (totaal, functie en pijn subscore), mate van pijn, WOMAC, patiënttevredenheid, patiëntvoorkeur voor type prothese, radiografische en CT indicaties voor osteolyse. In deze tot op heden enige studie met middellange follow-up, wordt geen statistisch significant verschil gemeten in overleving van de prothese. Met revisie als eindpunt, bedraagt de overleving van high-flex en standaard prothese na tien jaar, respectievelijk 99% (95%BI, [93; 100]) en 100% ([94; 100]). Met aseptische loslating als eindpunt is de overleving van de prothese 100% in beide groepen (95%BI, [95; 100]). In de RCT van Nutton (2012) wordt na een follow-up van één jaar, geen significant verschil gemeten in KSS (functie en knie subscore), kwaliteit van leven (SF36; fysieke en mentale subscore), en de WOMAC subscores voor stijfheid en functie. Voor WOMAC-pijn wordt wel een statistisch significant hogere score gemeten in de high-flex groep (4,2 [2,9; 5,5] versus 2,5 [1,5; 3,5]; p=0,04). In de RCT van Seng (2011) wordt na een follow-up van vijf jaar, geen statistische significant verschil gemeten in KSS (functie en knie subscore) en OKS. Wel worden statistisch significant hogere SF-36 scores gerapporteerd voor algemene gezondheid, vitaliteit en fysiek functioneren in de high-flex groep. Studiekwaliteit is echter laag, en opmerkelijk is dat bij een follow-up duur van twee jaar geen verschillen worden waargenomen tussen de behandelgroepen in algemene gezondheid, vitaliteit en fysiek functioneren. De RCT van Singh (2012) vindt na een follow-up van twee jaar, geen statistisch significante verschillen in KSS (totaal, functie en pijn subscore), HSS en in het voorkomen van complicaties en revisies. Endres (2011) is een retrospectieve cohortstudie. Na een gemiddelde follow-up van ruim vijf jaar, wordt geen verschil gerapporteerd in KSS. De RCT van Hamilton (2011a) vindt na een gemiddelde follow-up van één jaar, geen statistisch significant verschil in KSS, OKS en patiënttevredenheid. De meest frequente complicatie, patellar crepitus, komt statistisch significant vaker voor bij toepassing van de high-flex knieprothese (bij 17% van de patiënten versus 3% in controle groep). Tenslotte, rapporteert Choi (2010) na een gemiddelde follow-up van 28 maanden, geen statistische significant verschillen tussen high-flex en standaard knieprothese, in KSS, HSS, WOMAC (pijn, stijfheid en functie subscore), of radiografische indicaties voor osteolyse. Eveneens worden geen significante verschillen waargenomen met betrekking tot patiënttevredenheid, en het vermogen om te knielen, squatten, zitten met gekruiste benen, of opstaan na zitten op de grond (gemeten aan de hand van vragenlijsten).

Doordat de high-flex totale knieprothese nog te kort en te infrequent wordt toegepast, is in nationale protheseregisters nog geen zinvolle vergelijking mogelijk van de levensduur tussen de high-flex en conventionele totale knieprothese.

Samenvattend geven bovenstaande studies aan dat met high-flex knieprotheses en standaard knieprotheses vergelijkbare klinische resultaten worden bereikt, en dat patiënttevredenheid, bijwerkingen en complicaties niet significant verschillen. Wel lijken patella-crepitaties vaker voor te komen bij toepassing van de high-flex knieprothese. Er zijn nog weinig gegevens beschikbaar met betrekking tot de levensduur van de high-flex prothese-ontwerpen. In de enige studie met een follow-up van tenminste tien jaar (Kim 2012) wordt geen statistisch significant verschil gemeten in overleving tussen high-flex en standaard knieprothese, maar de studieomvang (power) is niet afgestemd op een analyse van zeldzame uitkomsten (ernstige complicaties; noodzaak tot revisie). De geïncludeerde studies bevatten geen data met betrekking tot kosteneffectiviteit.

Figuur 1.1 Meta-analyse van de vergelijking tussen high-flex en conventionele knieprotheses met betrekking tot bewegingsbereik van de knie (range of motion, ROM). Random effects model (update van Luo et al., 2011).

Figuur 1.2 Meta-analyse van de vergelijking tussen high-flex en conventionele knieprotheses met betrekking tot bewegingsbereik van de knie (range of motion, ROM). Sensitiviteitsanalyse: analyse beperkt tot RCT’s; random effects model (update van Luo et al., 2011).

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat bewegingsbereik van de knie (ROM) is met één niveau verlaagd vanwege beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet (van de acht geïncludeerde RCT’s zijn er slechts drie van goede kwaliteit). De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat klinisch resultaat, in termen van kniefunctie, pijnklachten, patiënttevredenheid, en milde (niet zeldzame) bijwerkingen en complicaties, is eveneens verlaagd met één niveau verlaagd vanwege beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet. De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat levensduur, is verlaagd met twee niveaus vanwege ernstige imprecisie (slechts één studie met een voldoende lange follow-up, geringe studieomvang).

Zoeken en selecteren

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende wetenschappelijke vraagstelling: wat zijn de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van het gebruik van een high-flex totale knieprothese in plaats van een conventionele totale knieprothese bij patiënten met gonartrose?

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte de klinische resultaten (pijn [VAS]; samengestelde scores [KSS, HSS, IKS, WOMAC, OKS, KOOS]), gewrichtsfunctie (bewegingsbereik [ROM; toename ten opzichte van preoperatieve ROM], buigen, strekken, stabiliteit), activiteiten van dagelijks leven (ADL), bijwerkingen en complicaties (revisies; levensduur van de prothese) voor de besluitvorming kritieke uitkomstmaten; en patiënttevredenheid en kosteneffectiviteit voor de besluitvorming belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

De werkgroep definieerde een klinisch relevant verschil als een verschil van tenminste: 5o (ROM), 10 punten (KSS; maximum score is 100), 10 punten (HSS; maximum score is 100), 10 punten (WOMAC; maximum score is 100), 1 punt (pijn [VAS]; maximum score is 10; Kelly 2001) 1% (revisie; middellange termijn [5-10 jaar]), en 2% (revisie; lange termijn [> 10 jaar]).

Zoeken en selecteren (Methode)

In de databases Medline (OVID), Embase and Cochrane is met relevante zoektermen gezocht vanaf 2005 naar de toepassing van high-flex totale knieprotheses bij patiënten met gonartrose. De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad verantwoording. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria: (systematisch review van) vergelijkend onderzoek, vergelijking van high-flex versus conventionele totale knieprothese, volwassen patiënten met een primaire of secundaire artrose van de knie, met klinische resultaten (pijn, samengestelde scores), gewrichtsfunctie, activiteiten van dagelijks leven, bijwerkingen en complicaties (revisies), patiënttevredenheid en kosteneffectiviteit als uitkomstmaten. De initiële literatuurzoekactie was gericht op systematische reviews en leverde vijftien treffers op. Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie zes studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens vier studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel), en twee studies definitief geselecteerd. De geselecteerde systematische reviews dekken de literatuur tot januari 2010, en zijn in een tweede zoekactie aangevuld met relevante recentere studies. In deze tweede literatuurzoekactie werd niet beperkt op studiedesign en gezocht vanaf 2010. De aanvullende zoekactie leverde 170 treffers op. Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 18 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens elf studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel), en zeven studies definitief geselecteerd.

In totaal zijn negen onderzoeken (twee systematische reviews en zeven originele onderzoeken) opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse. De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken en resultaten zijn samengevat in de evidencetabel.

Voor de uitkomstmaat levensduur van de prothese (ernstige complicaties, revisies) zijn tevens de landelijke prothese-registers van Zweden, Noorwegen, Denemarken, Groot Brittannië en Australië geraadpleegd.

Referenties

- Choi WC, Lee S, Seong SC, et al. Comparison between standard and high-flexion posterior-stabilized rotating-platform mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasties: a randomized controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:2634-42.

- Endres S. High-flexion versus conventional total knee arthroplasty: a 5-year study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2011;19:226-9.

- Hamilton WG, Sritulanondha S, Engh CA. Prospective randomized comparison of high-flex and standard rotating platform total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011;26(6 Suppl):28-34.

- Kelly AM. The minimum clinically significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score does not differ with severity of pain. Emerg Med J 2001;18:205-7.

- Kim YH, Park JW, Kim JS. High-flexion total knee arthroplasty: survivorship and prevalence of osteolysis: results after a minimum of ten years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:1378-84.

- Luo SX, Su W, Zhao JM, et al. High-flexion vs conventional prostheses total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:847-54.

- Nutton RW, Wade FA, Coutts FJ, et al. Does a mobile-bearing, high-flexion design increase knee flexion after total knee replacement? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012;94:1051-7.

- Seng C, Yeo SJ, Wee JL, et al. Improved clinical outcomes after high-flexion total knee arthroplasty: a 5-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:1025-30.

- Singh H, Mittal V, Nadkarni B, et al. Gender-specific high-flexion knee prosthesis in Indian women: a prospective randomised study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2012;20:153-6.

- Sumino T, Gadikota HR, Varadarajan KM, et al. Do high flexion posterior stabilised total knee arthroplasty designs increase knee flexion? A meta analysis. Int Orthop 2011;35:1309-19.

Evidence tabellen

Tabel 1 Quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCT’s and observational studies

based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Research question: what is the optimum design of a total knee replacement prosthesis: high flexion versus conventional prostheses

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Luo, 2011 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No* |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Sumino, 2011 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No** |

Yes |

No*** |

No |

Unclear |

|

Hamilton, 2011b |

Yes |

Yes |

No**** |

No**** |

Not applicable |

No |

Unclear |

No |

Unclear |

*Out of 11 studies included in the meta-analyses, 5 studies were RCT’s, and the remaining 6 were observational studies without adjustment for potential confounders

** Out of 18 studies included in the meta-analyses, 8 studies were RCT’s, and the remaining 10 were observational studies without adjustment for potential confounders; in addition, some studies did not directly compare conventional and high-flexion prostheses (: indirect comparison)

***Meta-analyses was performed despite large to extreme statistical heterogeneity

****Only included studies are described, and relatively few study details are provided (baseline data are lacking)

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCT’s)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Tabel 2 Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: what is the optimum design of a total knee replacement prosthesis: high flexion versus conventional prostheses

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Choi et al, 2010 |

Computer-generated block randomization |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear* |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Kim et al, 2012 |

Table of random numbers |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear* |

Unlikely** |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Nutton et al, 2012 |

Computer-generated block randomization |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear* |

Unlikely |

Unlikely*** |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Seng et al, 2011 |

‘randomly issued sealed envelopes’ |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear* |

Unlikely |

Likely**** |

Likely***** |

Likely***** |

|

Singh et al, 2011 |

Not stated |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear* |

Unclear****** |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Hamilton et al, 2011a |

Not stated |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear* |

Unclear******* |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

*Care providers were not blinded to treatment allocation, but risk of bias is not likely

**For most outcome measures, outcome assessors were blinded, for some outcome measures (radiography, CT) not, but risk of bias is unlikely

***No evidence for selective outcome reporting, but multiple outcome measures are used without statistical correction for multiple testing

****Multiple outcome measures (score items, timepoints), selective reporting

*****Differential loss to follow-up (12% vs 23%) at small group size (no ITT analysis)

******No statement on blinding assessor

******Outcome assessors were not blinded, but risk of bias is not likely

- randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules..

- blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear

- participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Tabel 3 Risk of bias table for intervention studies (observational: non-randomized clinical trials, cohort and case-control studies)

Research question:what is the optimum design of a total knee replacement prosthesis: high flexion versus conventional prostheses

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Endres et al, 2011 |

Unlikely |

Unclear* |

Unlikely |

Unclear** |

*Unclear whether there was no loss to follow-up, or patients lost to follow-up were excluded

**Treatment groups differ in bmi and KSS (data are not adjusted)

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Tabel 4 Evidence table for systematic review of RCT’s and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: what is the optimum design of a total knee replacement prosthesis: high flexion versus conventional prostheses

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Luo et al, 2011

[individual study characteristics deduced from Luo et al, 2011; unless stated otherwise] |

SR and meta-analysis of RCT’s and cohort studies

Literature search up to jan 2010

A: Bajammal 2006 B: Bin 2007 C: Ng 2008 D: Nutton 2008 E: Malik 2009 F: McCalden 2009 G: Kim 2009 H: Minoda 2009 I: Seon 2009 J: Suggs 2009 K: Wohlrab 2009

Study design: RCT (D,F,G,I,K); retrosp cohort (A,B,E,J); prosp cohort (C,H)

Source of funding: No outside funding or grants (A, E, F, G, H, I); authors SR declare ‘no benefits or funds received’

|

Inclusion criteria SR: controlled clinical trials; high-flex vs conventional; advanced or end-stage arthritis; primary TKA; ROM as outcome; at least 1-year fup

Exclusion criteria SR: history septic arthritis; studies with insufficient data (no SD)

11 studies included (1204 knees; 561 high flex, 563 conventional)

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N; mean age (yrs) Knees; I/C A: 87/87; 70/70 B: 90/90; 67/66 C: 35/35; 68/68 D: 28/28; 71/68 E: 50/50; 65/67 F: 50/50; 70/72 G: 54/54; 70/70 H: 87/89; 71/70 I: 50/50; 69/68 J: 11/15; 67/69 K: 30/30; 67/66

Sex(% male); BMI: I/C A: 38/38; 34/33 B: 93/94; 27/28 C: 20/20; 33/33 D: 61/43; ?/? E: 71/69; 31/31 F: 46/50; 33/32 G: 9/9; 27/27 H: 10/21;?/? I: 12/20;26/27 J: 82/80; ?/? K: 47/40; 24/24

Pre-operative ROM Mean (o); I/C A: 110.6 / 113.1 B: 117.9 / 115.3 C: 104 / 105 D: 108 / 107 E: 125 / 122 F: 111 / 114 G: 128/ 128 H: 98.9/ 101.2 I: 124.1 / 125.9 J: ? / ? (not stated) K: 108.5 / 105.6

|

A: PS-Flex B: PS-Flex C: PS-Flex D: PS-Flex E: PS-Flex F: PS-Flex G: CR-Flex H: CR-Flex I: CR-Flex J: CR-Flex K: PS-Flex

subgroups PS-Flex (A-F, K) CR-Flex (G-J)

PS = posterior stabilized CR = cruciate retaining ROM = range of motion

|

A: PS B: PS C: PS D: PS E: PS F: PS G: CR H: CR I: CR J: CR K: PS

subgroups PS (A-F, K) CR (G-J)

|

A: 12 months B: 12 C: 35 D: 12 E: 12 F: 31 G: 12 H: 12 I: 24 J: 15 K:36

Note: follow-up varies between 1-3 years

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control)

Not stated

|

ROM (o) Post-operative ROM at ≥ 1 year follow-up; WMD [95% CI]

PS-Flex vs PS (7 studies; 740 knees) A: 0.10 [-3.17;3.37] B: 5.80 [3.38;8.22] C: 1.00 [-5.33;7.33] D: 4.00 [-4.90;12.90] E: 0.00 [-4.27;4.27] F: 1.00 [-1.74;3.74] K:3.00 [-2.17;8.17] Pooled: 2.50 [1.13;3.88] favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 50% fixed effects model

Authors remove study-B to reduce heterogeneity (6 studies; 560 knees): Pooled: 0.93 [-0.75;2.60] favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

CR-Flex vs CR (4 studies, 410 knees) G: 4.00 [-0.68;8.68] H: 3.30 [-0.54;7.14] I: -2.63 [-10.66;5.40] J: 1.00 [-2.25;4.25] Pooled: 2.06 [-0.06;4.17] favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 0% fixed effects model

Other outcome measures (below): no subgroup analyses i.e. PS-Flex vs PS, and CR-Flex vs CR analyzed together

Weigh-bearing flexion (o) G: 5.00 [-0.47;10.47] I: 1.10 [-2.70;4.90] J: -3.40 [-16.21;9.41] Pooled: 2.05 [-0.99;5.08] favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 3% Fixed effects model

Knee Society Scores (KSS) A: 1.80 [-1.16;4.76] G: 0.20 [-4.01;4.41] H: 3.00 [-0.88;6.88] J: -1.90 [-11.43;7.63] Pooled: 1.59 [-0.42;3.60] favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 0% Fixed effects model

Hospital Special Surgery Scores (HSS) B: 0.40 [-1.04;1.84] G: 1.00 [-3.82;5.82] I: 2.10 [-0.39;4.59] Pooled: 0.84 [-0.37;2.04] favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 0% Fixed effects model

Complications I vs C (kind of complication) A:1/87 vs 0/87 (stifness) F: 2/50 vs 2/50 (ant knee pain) H: 1/87 vs 0/89 (supracon. fr) K: 1/30 vs 1/30 (revision) H+K: 5/117 vs 7/119 (radiolucent line) all p-values non-significant; No infection, loosening, and osteolysis were found |

Authors conclude that current evidence cannot confirm that high-flexion prostheses are superior to conventional prostheses (in knee ROM, weightbearing flexion, knee scores, and complications with at least 1-year follow-up); more high-quality studies are required, and with longer follow-up to determine whether there are any differences in risk of adverse events

Clinically relevant difference: ‘a difference of at least 5o in ROM’ (Chaudhary et al, 2008, JBJS Am 90: 2579)

Methodological quality (as reported in SR) Sequence generation / allocation concealment / assessor blinding / incomplete outcome / Selective reporting / Other bias; N [No]; Y [Yes]; U [Unclear] A: NNUUUY (retrosp cohort) B: NNNYUU (retrosp cohort) C: NNUYUU (prosp cohort) D: YYYYYU (RCT) E: NNNNYY (retrosp cohort) F: UUYYYY (RCT) G: YYYYYY (RCT) H: NNNNYY (prosp cohort) I: UYYYYY (RCT) J: NNUUYU (retrosp cohort) K: YUYYUU (RCT) No evidence suggesting publication bias (: funnel plot; but not that the number of studies is low)

Note: knee flexion > 90° is essential; 105° to 110° fulfills the needs in daily live except squatting; however, some people may need more knee flexion, for some Islamic and Oriental patients, squatting, bending, and sitting are essential for their daily lives (Mulholland and Wyss, 2001, Int J Rehabil Res 24: 191)

Note: RCT’s and observational studies included; observational studies not corrected for confounders |

|

Sumino et al, 2011

[individual study characteristics deduced from Sumino et al, 2011; unless stated otherwise]

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCT’s and observational studies

Literature search up to jan 2010

A: Maloney 1992 B: Parsley 2006 C: Malik 2009 D: Nutton 2008 E: Cheng 2010 F: McCalden 2010 G: Chaudhary 2008 H: Tanzer 2002 I: Wohlrab 2009 J: Victor 2005 K: Gioe 2009 L: Zeh 2009 M: Bozic 2005 N: Bin 2007 O: Maruyama 2008 P: Hasegawa 2008 Q: Ng 2008 R: Watanabe 2009

Study design: RCT (D,G,H,I,J,K,P,Q); Observational (A,B,C,D,E,F,L,M,N,O,R); includes studies not comparing standard and high-flex

Setting and Country: USA/Canada/Europe (A-M); South Korea / Japan / China (N-R)

Source of funding: Authors SR declare ‘no conflicts of interest’; no info on funding in the individual studies

|

Inclusion criteria SR: prim TKA; traditional PS and/or H-F PS; osteoarthritis and other non-traumatic Diseases; at least 1 year fup; single fixed-bearing PS prosthesis design; reporting of knee flexions with SD (pre and post)

18 studies included (2622 knees; 518 high flex, 2104 conventional)

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N; mean age (yrs) Knees; I/C A: 53; 68 B: 121; 68 C: 50/50; 67/65 D: 28/28; 68/71 E: 144; 70 F: 1177/179; 68/66 G: 38; 70 H: 20; 66 I: 30; 67 J: 7; 70 K: 136; 73 L: 63; 68 M: 130; 66 N: 90/90 ;66/67 O: 20; 74 P: 25; 73 Q: 35/35; 68/68 R: 28/27; 71/71

Sex(% male); BMI: Overall 32% male Overall bmi 29.7

|

A: Total-condylar vs I-B I B: PS vs ultracongruent C: Conv PS vs H-F PS D: Conv PS vs H-F PS E: Pre-op vs no pre-op F: PS, H-F PS and CR G: PS vs CR H: PS vs CR I: Conv fix bear vs H-F MBPS J: PS vs CR K: PS vs MB PS L: Genesis II PS H-F M: PS vs CR

N: Conv PS vs H-F PS O: PS vs CR P: PS vs MB PS Q: Conv PS vs H-F PS R: MIS vs conventional

subgroups Western (A-M) Asian (N-R)

|

See intervention: mean difference between pre- and post-operative flexion were pooled, for conventional, and high-flex designs

|

A: 21 months B: ‘minimal 1 year’ C: 1 year D: 1 year E: 12 year F: 5.4 year G: 22.7 months H: 2 years I: 5 years J: 21 months K:42 months L: 16.3 months M: 5.9 months

N: 1 year O: 30.6 months P: 40 months Q: 35 months R: 2.6 year

Note: follow-up varies between 1-12 years

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? In total, 8 lost to final follow-up for conventional PS and 16 for H-F PS implants

|

Gain in ROM (o) Difference between pre- and post-operative ROM; MD [95% CI]

Conventional PS (16 studies; 2096 knees) Pooled: 4.70 [2.50;6.91] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 77% random effects model note high heterogeneity

High-Flex PS (7 studies, 502 knees) Pooled: 4.81 [2.01;7.61] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 56% random effects model note high heterogeneity

Per subgroup (Wester/Asian) Western Conventional PS (12 studies; 1926 knees) Pooled: 4.51 [2.04;6.99] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 79% random effects model note high heterogeneity

High-Flex PS (4 studies, 322 knees) Pooled: 7.26 [4.39;10.14] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 29% random effects model

Asian Conventional PS (4 studies; 170 knees) Pooled: 5.61 [-0.56;11.77] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 76% random effects model note high heterogeneity

High-Flex PS (3 studies, 180 knees) Pooled: 2.00 [-2.97;6.97] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 61% random effects model note high heterogeneity

|

Authors conclude that that improvement of preoperative flexion after TKA using current H-F PS prostheses is similar to that of conventional PS prostheses

Authors also state that Western group showed a significant difference in improvement of knee flexion with conventional PS versus H-F PS groups (H-F PS showed 3° higher improvement in knee flexion

However, p-values are not reported for these subgroup comparisons, and EXTRA calculations show that there are NO STATISTICALLY SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CONVENTIONAL AND H-F

Extra calculations (RevMan):

(1) Overall (Western+Asian; conv + high-flex) Pooled: 4.68 [2.98; 6.37] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 72% random effects model note high heterogeneity

(2) Western: test for subgroup difference (conv versus high-flex) Pooled: 5.05 [3.04;7.06] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 75% random effects model note high heterogeneity test for subgroup difference: p = 0.15 (not significant)

(3) Asian: test for subgroup difference (conv versus high-flex) Pooled: 3.73 [0.24;7.22] favoring post-operative ROM Heterogeneity (I2): 65% random effects model note high heterogeneity test for subgroup difference: p = 0.37 (not significant)

Methodological quality (as reported in SR) Modified Coleman Methodology score (MCDS); based on CONSORT, max 100 (<50 poor; 50-69 moderate; 70-84 good; >85 excellent)

A: 53 / B: 49 / C: 41 / D: 86 E: 67 / F: 69 / G: 86 / H: 63 I: 64 / J: 69 / K: 92 / L: 61 M: 62 / N: 64 / O: 58 / P: 70 Q: 33 / R: 56; i.e. excellent (3 studies), good (1), moderate (11), and poor (3)

Note: RCT’s and observational studies included; observational studies not corrected for confounders; in addition several of the included studies do not compare conventional and high-flex prostheses (in the meta-analyses, gain in ROM is pooled per prothesis type, and pooled results are compared), this is an indirect comparison; finally, pooling is very questionable given the large to extreme statistical heterogeneity (unexplained) |

|

Choi et al, 2010

|

RCT

Setting and country: Dept Orthop Surgery, University Hospital, South Korea

Source of funding: no outside funding or grants; no payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity |

Inclusion criteria: consecutive patients; primary TKA

Exclusion criteria: diagnosis other than primary osteoarthritis; previous open knee surgery

N total at baseline: Interv: 85 knees Control: 85 knees Mean ± SD Age I: 71.1 ± 6.0 C: 70.1 ± 5.8 Sex I: 7.1 % M C: 3.5 % M BMI I: 26.5 ± 3.5 C: 26.6 ± 3.2 Flexion contr I: 16 ± 8.5 C: 15 ± 7.4 Active max flexion I: 126 ± 13.4 C: 127 ± 14.5 Total ROM I: 110 ± 18.0 C: 112 ± 18.3 KS-score-Knee I: 36 ± 17.2 C: 37 ± 12.1 KS-score -Function I: 36 ± 15.5 C: 38 ± 15.3 HSS-score I: 43 ± 13.3 C: 47 ± 11.2 WOMAC-Pain I: 12 ± 3.9 C: 12 ± 3.8 WOMAC-Stiffness I: 5 ± 1.7 C: 5 ± 2.3 WOMAC-Function I: 43 ± 12.2 C: 42 ± 12.8

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

High-flexion PS rotating-platform mobile-bearing TKA (P.F.C. Sigma RP-F) N= 85 knees (ITT) N=76 knees (PP)

All surgical procedures by same experienced surgeon; both cruciate ligaments resected; all prostheses fixed with cement

|

Standard version (P.F.C. Sigma RP)

N= 85 knees (ITT) N=74 knees (PP) |

Length of follow-up: minimum 2 years; mean 28 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 9(11%) Reasons <2 years fup (4) Deaths at < 2 years fup (1) Additional surgery needed (4): Periprosth infection (1) Patell clunk / crepitat (3)

Control: 11(13%) Reasons <2 years fup (4) Additional surgery needed (7): Periprosth infection (1) Patell clunk / crepitat (6)

ITT = 85/85 (I/C) using last observation carried forward

PP = 76/74 (I/C)

Note: in the current table, only ITT results are shown (similar results were obtained with PP) |

ROM active maximal knee-flexion angle, flexion contracture, total ROM; goniometer with patient in supine position (non-weight-bearing); at 2 yrs fup (?)

Functional status KSS, HSS, WOMAC (Likert 3.1 version) at 2 years fup(?); questionnaire at 2 y fup (abilities to kneel, squat, sit cross-legged,and arise after sitting on the floor)

Patient satisfaction questionnaire (5-point Likert scale; fully satisfied, 5; very dissatisfied, 1); at 2 years fup(?)

Radiographic indices preoperatively and at time final fup; Tibiofemoral angles on full-length standing anteroposterior radiographs

ROM (o) Post-operative ROM at 2 year follow-up (?); mean, SD (p)

Flexion contracture 2 ±3.6 vs 2 ±3.9 (p=0.71)

Active maximal flexion 128 ±11.1 vs 130 ±10.4 (p=0.28)

Total range of motion 127±12.6 vs 129±11.6 (p=0.28)

Functional status KSS-knee 94 ± 9.0 vs 95 ± 6.9 (p=0.39) KSS-function 91 ± 8.8 vs 92 ± 7.7 (p=0.60)

HSS 92 ± 7.5 vs 93 ± 5.9 (p=0.38)

WOMAC-pain 2 ± 1.6 vs 2 ± 2.2 (p=0.39) WOMAC-stiffness 1 ± 1.6 vs 1 ± 1.4 (p=0.76) WOMAC-function 9 ± 5.8 vs 9 ± 6.6 (p=0.53)

Flexion-Related Activity kneeling 70 vs 74% (p=0.53) squatting 67 vs 67% (p=0.77), sitting X-leg 72 vs78% (p=0.39) arising after sitting on floor 87 vs 87% (p=0.45)

Patient satisfaction fully satisfactory or satisfactory outcomes 91 vs 91% (p = 0.96)

Radiographic indices No statistically significant differences; no obvious radiolucent line around a prosthesis or any sign of osteolysis was observed |

Authors conclude that there were no significant differences between standard and high-flexion posterior-stabilized rotating-platform mobile-bearing total knee prostheses in terms of clinical or radiographic outcomes or range of motion at a minimum of two years postoperatively

22 patients had standard prosthesis in one knee and high-flexion in the other [which might jeopardize reliability of the observations because of non-independence of results], however, sensitivity analyses that excluded the bilateral cases were in accordance with the overall results

female predominance, relatively good preoperative motion, and low bmi might have influenced findings;

knee ROM measured with patients in supine position, rather than under weight-bearing conditions; however, patients’ abilities to perform activities that required weight-bearing knee flexion were similar in the two groups

NCT00954954; prim outcome measures according to register (ClinicalTrials.gov): range of knee motion, knee scores, patients' abilities to perform deep knee flexion related activities, patient satisfaction and radiographic indices

Power calculation: 64 per group required to detect clinically relevant differ- ence in the range of motion (assumed to be 5°) with SD 10° (a = 0.05 and b = 0.8)

Note: not completely clear whether all outcome measures were obtained at 2 years followup; excludingthe 22 bilateral patients with 2 different prostheses decreases powerto borderline

For comment, see Delanois et al (2010), J Bone Joint Surg Am 92:e29(1-2) |

|

Kim et al, 2012

|

RCT

Setting and Country: Joint Replacement Center, University Hospital, South Korea

Source of funding: no outside funding or grants; no payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity |

Inclusion criteria: consecutive prim bilateral TKA patients; end-stage osteoarthritis

Exclusion criteria: Inflammatory disease;lower extremity disease; neurologic disease effecting patients lower extremity; revision surgery

111 patients recruited (222 knees), 5 patients died of unrelated causes, 6 patients were followed for <2 years and excluded post-randomization; study population, N=100 patients (200 knees)

N total at baseline: Interv: 100 knees Control: 100 knees Mean [range] Age 65 [48-85] Sex 25% male BMI 26 [24-27] KSS-total I: 28 [4;44] C: 25 [4;47] KSS-function I: 50 [-8;68] C: 50 [-7;68] Degree of pain None: 0 vs 0% Mild: 0 vs 0% Moder: 14 vs 10% Severe: 86 vs 90% WOMAC 67.3 vs 65.2 Activity 1.7 vs 1.6 ROM Total arc motion; weight-bearing I: 110 [80;130] C: 113 [70;135] Non-weight-bearing I: 125 [80;150] C: 128 [75;150]

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes; each patient is its own control (bilateral TKA with both types of prostheses)

|

High-flex PS (NexGen LPS-Flex,(Zimmer)

N= 100 knees (PP)

Each patient received both types of prostheses

All surgical procedures by senior author; both cruciate ligaments resected; all patellae resurfaced with polyethylene patellar prosthesis; all prostheses fixed with cement

33 patients (33%) had undergone bilateral arthroscopic debridement previously

|

Standard version (NexGen LPS, Zimmer)

N= 100 knees (PP)

Each patient received both types of prostheses

|

Length of follow-up: mean [range] 10.3 y [10.0- 10.6]

Loss-to-follow-up: 11/111 patients (9.9%) excluded post-randomization; % loss to fup identical in intervention and control (each patient received both types of prostheses)

|

Functional status Separately for each knee (!) at 10 years fup; KSS (total, function, pain); degree of pain; WOMAC; activity scores of Tegner and Lysholm

ROM Weight-bearing; using goniometer with patient in supine position; active maximal knee-flexion angle (arc of motion), flexion contracture

Patient satisfaction and preferrence

Radiographic indices Anteroposterior radiographs, lateral radiographs, and skyline patellarradiographs

CT evaluation To assess osteolysis

Results (intervention versus control)

Functional status At final followup (10 years) KSS-total (mean) 92 vs 93 (p=0.87) KSS-function 82 vs 85 (p=0.83) KSS-pain 43 vs 45 (p=0.64)

Degree of pain None: 71 vs 75% Mild: 28 vs 25% Moderate: 1 versus 0% Severe: 0 vs 0%

WOMAC 32.3 vs 28.9 (p=0.93)

Activity(Tegner Lysholm) 5.9 vs 5.7

ROM (o) At final followup (10 years) Total arc of motion; mean [range] weight-bearing 121 [70;135] vs 118 [75;130] P=0.18 Non-weight-bearing 135 [80;140] vs 133 [90;140] P=0.19

Patient satisfaction and preferrence fully satisfied 72 vs 75% satisfied 27 vs 25% dissatisfied 1 vs 0%

no preference 87% LPS-Flex 6% LPS-standard 7%

Radiographic indices No statistically significant differences for: alignment (varus; valgus); femoral angle; tibial angle; joint line level; condylar offset

Radioluscent lines: Femoral 9 vs 5% Tibial 9 vs 7%

CT evaluation Osteolysis 0 vs 0% |

Authors conclude that after a minimum duration of follow-up of ten years, there were no significant differences with regard to implant survivorship, functional outcome, knee motion, or prevalence of osteolysis

Authors believe that the extra bone removed to allow for the NexGen LPS-Flex prosthesis (particularly in patients with small bones) may affect femoral component fixation and may be a concern should revision arthroplasty be necessary

NCT 01422642; in register (ClinicalTrials.gov) KSS as prim Outcome, and ROM as sec outcome (other outcome measures are not mentioned)

Complication rate was low and similar:1 knee in each group exhibited deep infection

Survivorship Analysis: with revision end point, 100% implant-survival rate for LPS (95% CI, 94 to 100) and 99% forLPS-Flex (95% CI, 93 to 100) at 10 years fup

with aseptic loosening as end point, survival rate was 100% (95 to 100) in both groups at ten years postoperatively

Note: bilateral TKA with patients receiving both types of prosthesis; paired analysis (paired t-test); authors report that patient could distinguish pain and degree of stiffness in each knee, this was more difficult for knee function

Note: in trial register, only KSS and ROM mentioned as outcomes; 11 patients were excluded post-randomization (i.e. not an ITT analysis); 75% of patients are women

Note: absence of osteolysis may be related to preponderance of female patients

|

|

Nutton et al., 2012

|

RCT

Setting and Country:Orthop Dept, UK

Source of funding: no benefits received

|

Inclusion criteria:; osteoarthritis; unilateral primary TKR; minimum range of flexion of 90°; fit enough for electrogoniometry assessment

Exclusion criteria: inflammatory arthritis; osteoarthritis hip causing pain or restricting mobility; foot ankle disorders limiting walking; dementia and neurological disorders affecting mobility

Aug 2007 - Dec 2009

90 patients recruited, 13 patients not randomized (7 cancelled surgery, 6 had a non-participating surgeon); 77 patients (77 knees) randomized; 1 patient died of unrelated cause (lost to fup from control group))

N total at baseline: Interv: 36 knees Control: 41 knees Interv vs Control Mean [95%CI]

Age 68.3 vs 69.8 F:M 18:18 vs 21:19 bmi 29.1 vs 29.8 Act flex 114 vs 113 Steps/d 6284 vs 5771

WOMAC Pain 9.8 vs 9.8 Stiffn 4.3 vs 4.6 Funct 31.3 vs 31.9

'weight-bearing' Peak flex (°) Sit down 89 vs 87 Max standing 102 vs 97 Squat 83 vs 85 Asc stairs 77 vs 76 Desc stairs 74 vs 72 Asc slope 56 vs 53 Desc slope 58 vs 55

ROM (°) Asc stairs 71 vs 69 Desc 68 vs 65 Asc slope 52 vs 47 Desc 54 vs 50 Level walk 53 vs 49

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes;but note tendency towards higher weight-bearing flexion and ROM in intervention (flex) group |

High-flex PS Non-CR

rotating-platform PCL-sacrificing high-flexion design femoral component (PFC-Sigma RP-F High-Flex)

Note: >1 difference in design between intervention and control

N= 36 knees (ITT)

All implants were cemented; no patellar resurfacing; all surgery by two surgeons; identical post-operative care

|

Standard CR

Fixed-bearing PCL conserving knee replacement with a standard femoral component (PFC Sigma)

N=41 knees (ITT) N=40 knees (PP)

|

Length of follow-up: 1 year

mean [range] 375 days [349- 399]

Loss-to-follow-up: 1/77 patients (1%); 1 died of unrelated causes (control group) |

ROM Non-weight bearing Active flexion using manual goniometer; measured on the plinth

Functional status Steps per day (n); WOMAC (pain, stiffness, function); KSS (function, knee); SF-36 (physical, mental)

Weight-bearing flexion/ROM Using electrogoniometry Peak flexion (sit down standard chair; Max while standing, squat, asc stairs, desc stairs, asc slope, desc slope); ROM (asc stairs, desc stairs, asc slope, desc slope, level walking)

Results (intervention versus control) At final followup (1 year) Mean [95%CI]

ROM Active flexion (°) I: 113 [109;117] C: 107 [104;110] P=0.032

Functional status

Steps per day (n) I: 6947 [5849;8045] C: 6303 [5457;7149] P=0.402

WOMAC Pain I: 4.2 [2.9; 5.5] C: 2.5 [1.5;3.5] P= 0.043 Stiffness I: 2.5 [1.9;3.1] C: 2.2 [1.7;2.7] P= 0.386 Function I: 13.6 [9.8;17.4] C: 10.8 [7.6;14.0] P= 0.289

Knee Society score Function I: 80.8 [74.2;87.4] C: 80.6 [74.9;86.3] P= 0.618 Knee I: 73.9 [68.4;79.4] C: 78.5 [75.1;81.9] P=0.310

Short-Form 36v2 Physical I: 46 [43;49] C: 47 [45; 50] P= 0.636 Mental I: 54 [51; 57] C: 55 [53;57] P=0.327

Weight-bearing flexion/ROM

Peak flexion sit down standard chair 84 vs 90 (p=0.153) Max while standing 93 vs 96 (p=0.440) Squat 84 vs 91 (p=0.150) asc stairs 79 vs 82 (p=0.222) desc stairs 77 vs 81 (p=0.276) asc slope 54 vs 57 (p=0.173) desc slope 58 vs 61 (p=0.164)

ROM asc stairs 73 vs 75 (p=0.468) desc stairs 72 vs 76 (p=0.151) asc slope 52 vs 56 (p=0.044) desc slope 56 vs 60 (p=0.103) level walking 54 vs 58 (p= 0.019) |

Authors conclude that the mean post-operative non-weight-bearing flexion was higher for the high-flex prosthesis 113° versus 107° (p = 0.032), however, weight-bearing ROM during both level walking and ascending a slope was a mean of 4° lower in the RP-F group than in the FB-S group (respectively p = 0.019 and p = 0.044), and the mean WOMAC-pain score was significantly higher in the RP-F group (p = 0.043).

‘Although the RP-F group achieved higher non-weight-bearing knee flexion, patients in this group did not use this during activities of daily living and reported more pain one year after surgery’

Clinically relevant difference: ‘differences < 4o are unlikely to be functionally significant’

Power calculation Based on 8o difference (!), 36 patients per group required

Note: patients of white European origin >> ‘other ethnic populations might achieve better flexion with the RP-F design’

Note that postoperative flexion/ROM depends on preoperative flexion/ROM; in an analysis of gain in flexion/ROM (post- minus pre-operative), the flex prosthesis (RP-F) did not show an increased gain in flexion/ROM as compared to FB-S:

Peak flexion Intervention vs Control sit down standard chair -4 vs 2 (p=0.022) asc slope -1 vs 5 (p=0.005) desc slope 0 vs 6 (p= 0.004) level walking -1 vs 5 (p= 0.003) ROM asc slope 0 vs 9 (p< 0.001) desc slope 1 vs 10 (p< 0.001) level walking 0 vs 9 (p=0.001) Other group differences were not statistically significant

Note that the same procedure (post minus pre) resulted in non-significant differences in ROM (non-weight bearing flexion) and WOMAC-pain

Note: Radiographic indices not determined, and complications not reported

|

|

Seng et al., 2011

|

RCT

Setting and Country:Orthop Dept, general hospital, Singapore, Malaysia

Source of funding: no benefits or funds received

|

Inclusion criteria:; degenerative joint disease; minimum preoperative ROM of 90°

Exclusion criteria: inflammatory arthritis; history septic arthritis; previous ipsilateral knee surgery

Nov 2001 to Sept 2003

76 patients recruited, 13 lost to fup (8 from control group); 63 analysed

N total at baseline: Interv: 41 knees Control: 35 knees Interv vs Control Mean [SD]

Age 67 vs 68 F:M 34:7 vs 24:11 bmi 27 vs 28

ROM Extens 3 vs 3 Flex 123 vs 122

KSS Funct 48 vs 48 Knee 42 vs 42

Oxford Knee Sc 36 vs 36

SF-36 Phys C 39 vs 38 Ment C 48 vs 51

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes;but note more women in intervention group (83% vs 69% w/o taking loss to fup into account [sex not specified]) |

High-flex Zimmer NexGen LPS-Flex

nonmobile, fixed-bearing

N= 36 knees (PP)

all implants were cemented; all patellae were resurfaced; 2 surgeons; postoperatively, all patients managed the same

|

Standard DePuy PFC

nonmobile, fixed-bearing

N=27 knees (PP)

Note: per protocol analysis

|

Length of follow-up: 5 year

Loss-to-follow-up: 13 patients; 5 patients intervention (12%) vs 8 patients control (23%); 4 died during the study period, 1 refused follow-up, the remainder not contactable

Reasons not specified per group |

by physiotherapists (blinded);

ROM Non-weight bearing; passively with a standard goniometer

Functional status KSS (function, knee); Oxford Knee score; SF-36 (physical, mental; others)

Complications, revision ..

Results (intervention versus control) at 6 m, 2 y and 5 y follow-up Mean [95%CI]

ROM 6 m/ 2 y/ 5 y I: 124/128/128 C: 115/116/117 P<0.05 (all timepoints)

Functional status

KSS-Knee I: 87/86/84 C: 84/85/87 P>0.05 (all timepoints)

KSS-Function I: 64/69/69 C: 61/74/62 P>0.05 (all timepoints)

SF-36-Phys Function I: 57/63/63 C: 61/68/53 P=0.03 (5 y)

SF-36-Phys Comp I: 61/48/47 C: 61/49/44 P>0.05 (all timepoints)

SF-36-Mental Comp I: 32/55/57 C: 31/55/51 P>0.05 (all timepoints)

SF-others (selectively reported):

SF-36-Gen Health 79 vs 62 P<0.001

SF-36-Vitality 74 vs 62 P=0.03

Oxford Knee score I: 22/21/18 C: 23/20/20 P>0.05 (all timepoints)

Complications, revision 1 case deep infection that required a 2-stage revision; survival rate 98.7% (1 case of revision TKA); no cases of femoral or tibia implant aseptic loosening on radiological imaging at the 5-year follow-up |

Authors conclude that high-flexion group achieved significant sustainable increase in postoperative knee flexion angle (128o ± 2o versus 117 o ± 2o ; p<0.05)

Authors also conclude a significant improvement in General Health, Vitality, and Physical Functioning scales of SF-36 at 5 years; however, these SF-36 items are reported selectively, and there is no difference in aggregated Physical Component score, and Mental Component score; in addition, there is no difference in General Health, Vitality, and Physical Functioning scales of SF-36 at 2 years (there is an unexplained drop in scores of the control group after 2 years)

Note: predominantly Asian patients >> results may not apply to Western populations; also note high % women

Note: study has considerable (and differential) loss to follow-up, and appears to lack power (cf Nutton et al, 2012)

Note: in update of meta-analysis, ROM at 5 years was used, assuming that error bars reflect 95% CI (I: 128 [126.2; 129.8], versus C: 117 [115.1; 118.9])

Author’s note: several studies concluded no significant differences in clinical outcome, however, mean postoperative flexion angles achieved by the high-flexion groups in these studies were usually <125° >> ‘high-flexion implant would likely yield best outcomes only when used in patients who would benefit most from the gains in physical function that the high-flexion implant is capable of delivering’

|

|

Singh et al., 2012

|

RCT

Setting and Country:Orthop Dept, Delhi, India

Source of funding: no statement on funding or benefits, nor on potential conflicts of interests

|

Inclusion criteria: Women; bilateral prim osteoarthritis; >60 years with varus deformity of 2º to 19º and an arc of flexion ≥ 90o

Exclusion criteria: rheumatoid arthritis, post-septic arthritis, previous surgical intervention in any knee, or psychiatric and neurological illnesses

Aug 2008 to July 2009

246 patients recruited; after exclusion, 100 randomized

N total at baseline: Interv: 50 (100 knees) Control: 50 (100 knees)

Interv vs Control Mean [SD]

Age 64 vs 68 Women only bmi 31 vs 31

ROM 112 vs 111

KSS 34 vs 36 Pain 16 vs 15 Funct 38 vs 39

HSS 56 vs 57

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

High-flex gender-specific NexGen LPS

Note: >1 difference in design between intervention and control

N= 100 knees (ITT)

patellae not resurfaced

|

Standard standard NexGen LPS

N=100 knees (ITT)

patellae not resurfaced

|

Length of follow-up: 2 year Mean [range] 2.1 [1.6-2.5] y

Loss-to-follow-up: None |

ROM Non-weight bearing; Active range in supine position using a goniometer

Functional status KSS (function, knee); HSS

Complications, revision

Results (intervention versus control) at latest follow-up Mean [SD]

ROM I: 122.8 [8.0] C: 119.9 [8.7] P=0.007

Functional status

KSS I: 94.9 [4.7] C: 95.8 [3.6] P=0.061

KSS-Knee Not stated

KSS-Function I: 80.2 [10.6] C: 79.9 [13.0] P=0.429

KSS-Pain I: 47.4 [3.5] C: 47.6 [3.1]] P=0.336

HSS I: 91.5 [4.8] C: 91.9 [4.1] P=0.313

Complications, revision Comparable in both groups (anterior knee pain, delayed wound healing)

|

Authors conclude that gender-specific high-flex group gained 3o more in ROM (p=0.007), KSS and HSS were not significantly different; the perceived advantage of a genderspecific high-flex over a standard prosthesis did not translate into better clinical and functional outcome

Note: study concern Indian women with relatively high bmi (~31 kg/m2)

|

|

Endres et al., 2011

|

Cohort, retrospective

Setting and Country:Orthop Dept, Olsberg, Germany

Source of funding: no statement on funding or benefits, nor on potential conflicts of interests

|

Inclusion criteria: consecutive patients; TKA for prim osteoarthritis

Single surgeon

Exclusion criteria: None stated

Jan 2005 to Jan 2006

107 patients; review of patient records

N total at baseline: Interv: 57 patients Control: 50

Number of knees not stated

Interv vs Control Mean [SD]

Age 65 vs 67 Male 37 vs 36% bmi 27 vs 29

ROM Max flexion 82 vs 85o Flexion contr 8.9 vs 10.1o

Function KSS 99 vs 89 Not clear which score is reported (KSS-knee, -function, -total?)

Groups comparable at baseline? Unclear; all p-values >0.05, but note lower bmi and higher baseline KSS in intervention group |

High-flex NexGen CR-Flex Mobile (Zimmer)

N= 57 patients

Mobile platform Cruciate retaining Patellae not resurfaced Cemented (fem+tib)

Note: intervention and control prosthesis from different manufacturers

|

Standard Genesis II (Smith & Nephew)

N=50 patients

Mobile platform Cruciate retaining Patellae not resurfaced Cemented (fem+tib)

|

Length of follow-up: Mean [range] 68 [51-70] months

Loss-to-follow-up: None stated (excluded from study?) |

ROM Non-weight bearing; max passive flexion; flexion contracture; using a goniometer

Functional status KSS (function, knee, total?)

Complications, revision radiolucent lines (radiographs) complications

ROM Mean [SD]

Max flexion I: 122 [10.6] C: 120 [12.6] P=NS

Flexion contracture I: 3.9 [6.6] C: 1.8 [8.9] P=NS

Functional status KSS; Mean [SD]

I: 167 [21] C: 159 [19] P=NS not clear which score is reported (KSS-knee, -function, -total?)

Complications, revision Comparable between groups

2 vs 1 developed deep vein thrombosis

1 vs 5 had unsatisfactory ROM (<60º) in week 1 (resolved with mobilisation under general anaesthesia)

No implant-specific complications such as aseptic loosening or dislocation of polyethylene insert

|

Authors conclude that high-flexion prosthes revealed no significant advantages over conventional prosthesis in terms of KSS andROM; long-term studies are needed to determine whether high-flexion implant is superior to conventional in terms of polyethylene wear and aseptic loosening

Note: retrospective study; implants from 2 different companies; KSS is a less responsivefunctional outcome measure then WOMAC or SF-36 |

|

Hamilton et al., 2011a

|

RCT

Setting and Country: Orthop Res Institute, Virginia, USA

Source of funding: supported by Depuy

|

Inclusion criteria: 40-70 years; prim. osteoarthritis;; good candidates for cemented, RP TKA; ability to meet followup Requirements (in investigator's opinion)

Exclusion criteria: bmi >40; fixed flexion contraction > 20°; posttraum. or inflamm arthritis; advanced hip, ankle, or spine disease; pregnancy or lactating

Aug 2007 to Apr 2009

142 patients randomized; 14 lost/excluded/withdrawn: 128 analyzed

N total at baseline: Interv: 71 Control: 69

Interv vs Control Mean [SD]

Age 65 vs 62 Male 48 vs 39% bmi 31 vs 30

ROM Clinical flexion 119 vs 120 Radiogr flexion 117 vs 117

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes (except for a difference in sex distribution)

|

High-flex Sigma RP-F (Depuy)

N= 66 patients (PP)

cemented patellae resurfaced

|

Standard Sigma PF-C (Depuy)

N=62 patients (PP)

cemented patellae resurfaced

|

Length of follow-up: 1 year Mean [range] 1 [0.8-1.8] y

Outcome measured at 1 year follow-up

Loss-to-follow-up:

I: 5/71 (7%) C: 7/69 (10%) 2 withdrawn, 2 excluded postrandomization (infection), 6 considered lost to follow-up

Not specified per group |

ROM Non-weight bearing; Active max flexion and extension with patient supine; goniometer (clin flexion), and using cross-table lateral radiograph (radiogr flexion); gain in flexion (post minus pre-operative flexion)

Functional status KSS (function, knee); OKS

Complications

Results (intervention versus control) at 1 year follow-up Mean [SD]

ROM

Clinical flexion I: 124.2 C: 124.0 P=0.95

Radiographic flexion I: 117.6 C: 117.9 P=0.99

Gain in flexion post minus pre-oper flexion no statistically significant differences between treatment groups

Subgroup analysis: pre-op flexion <105 vs 105-120 vs >120: no statistically significant differences between treatment groups

Functional status KSS and OKS

No statistical differences any of the scores between groups

‘Satisfaction scores’ I: 81.8% C: 88.7% P=NS

Complications, revision 2 withdrawn because of infection;4 underwent manipulation for stiffness (2/group); patellar crepitus was most frequent complication with 11 in intervention (17%) and 2 in control group (3%; P = .017) |

Authors conclude that study failed to show any clear benefit to the RP high-flex design; furthermore, there was a higher incidence of patellar crepitus in the high-flex group; costs were higher using high-flex implant

Authors state that for the reasons mentioned above they no longer routinely use the RP-F design

Power analysis: clinically important difference in mean flexion = 6°; α = .05 (2-sided); power = 80% >> 64 patients needed in each group, 71 patients per group assuming 10% attrtion

Note: short follow-up; only patients blinded to treatment; non-weight bearing ROM |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 18-02-2015

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 31-08-2021

Uiterlijk in 2019 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging (NOV) of deze richtlijn nog actueel is. Zo nodig wordt een nieuwe werkgroep geïnstalleerd om de richtlijn te herzien. De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

De Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging is als houder van deze richtlijn de eerstverantwoordelijke voor de actualiteit van deze richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijk verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de eerstverantwoordelijke over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn beoogt een leidraad te geven voor de dagelijkse praktijk van totale knievervanging. In de conclusies wordt aangegeven wat de wetenschappelijke stand van zaken is. De aanbevelingen zijn gericht op optimaal medisch handelen en zijn gebaseerd op de resultaten van wetenschappelijk onderzoek en overwegingen van de werkgroep, waarbij voor zover mogelijk de inbreng door patiënten is meegenomen (patiëntenperspectief). Het doel is een hogere kwaliteit en meer uniformiteit in behandelingsstrategie, en het verminderen van praktijkvariatie. Daartoe is een duidelijke indicatiestelling (tweede lijn) noodzakelijk. Doel van de richtlijn is met name ook het verminderen van postoperatieve pijn en verbeteren van de gewrichtsfunctie door optimalisatie van de zorg. Het identificeren van kennislacunes zal richting kunnen geven aan nieuw wetenschappelijk onderzoek en nieuwe ontwikkelingen. Tot slot is naar aanleiding van de noodzaak tot beheersing van de verdere groei van kosten in de gezondheidzorg aandacht besteed aan kosten en kosteneffectiviteit.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met (indicatie voor) een totale knieprothese: orthopedisch chirurgen en Physician Assistents, assistenten in opleiding tot orthopedisch chirurg, anesthesiologen, fysiotherapeuten, Huisartsen. De richtlijn is tevens van belang voor de patiënt, ter informatie en ten behoeve van shared-decision making.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2012 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een totale knieprothese.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. De werkgroep werkte gedurende twee jaar aan de totstandkoming van de richtlijn en is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

- Dr. M.C. de Waal Malefijt, NOV, orthopedisch chirurg in Radboudumc Nijmegen (voorzitter).

- Dr. R.D.A. Gaasbeek, NOV, orthopedisch chirurg in Meander Medisch Centrum in Amersfoort.

- Dr. S. Köeter, NOV, orthopedisch chirurg in Canisius Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis Nijmegen.

- Drs. L.N. Marting, NOV, orthopedisch chirurg in St. Antonius Ziekenhuis Nieuwegein.

- Drs. H. Verburg, NOV, orthopedisch chirurg in Reinier de Graaf Groep Delft.

- Dr. P.J. Hennis, NVA, anesthesioloog in Zuwehofpoort Ziekenhuis Woerden.

- Dr. W. Hullegie, KNGF, fysiotherapeut, lector, THIM Hogeschool voor Fysiotherapie Nieuwegein, FysioGym Twente, Enschede.

- Drs. G. van der Sluis, KNGF, fysiotherapeut in Nij Smellinghe Ziekenhuis Drachten.

- Dr. C.J. Kalisvaart, NVKG, klinisch geriater in Kennemer Gasthuis Haarlem.

- Drs. A. Kyriazopoulos, NVvR, radioloog in de St. Maartenskliniek Nijmegen.

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. K.N.J. Burger, epidemioloog, adviseur Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

- Mw. drs. M. Wessels, informatiespecialist Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

- Mw. S.K. Josso, secretariaat, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

- Mw. N.F. Bullock, secretariaat, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Met dank aan:

- Mw. drs. K.E.M. Harmelink, fysiotherapeut en fysiotherapiewetenschapper FysioGym Twente te Enschede en Fysiotherapiepraktijk Flex-s te Goor, promovendus aan Radboud Universiteit en HAN, Nijmegen.

- De Commissie Orthopedische Implantaten Classificatie (COIC) van de Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereninging, in het bijzonder R. Brouwer en G. van Hellemondt.

- Auteurs van recente Cochrane reviews naar prothese-ontwerp, in het bijzonder W.C. Verra, W. Jacobs, R.J.K. Khan, en R.G.H.H. Nelissen.

Belangenverklaringen

De werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of ze in de laatste vijf jaar een (financieel ondersteunde) betrekking onderhielden met commerciële bedrijven, organisaties of instellingen die in verband staan met het onderwerp van de richtlijn. Tevens is navraag gedaan naar persoonlijke financiële belangen, belangen door persoonlijke relaties, belangen door middel van reputatiemanagement, belangen vanwege extern gefinancierd onderzoek, en belangen door kennisvalorisatie. De belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten, een overzicht hiervan vindt u hieronder:

Tabel 1 Belangenverklaring

|

Werkgroep-lid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen |

Persoonlijke relaties |

Reputatie management |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Kennis-valorisatie |

Overige belangen |

|

Hennis |

anesthesio-loog, namens de NVA |

geen, geen belangen-verstrengeling op enigerlei terrein |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

|

Gaasbeek |

orthopedisch chirurg, namens NOV |

|

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |

|

Koëter |

orthopedisch chirurg, namens NOV |

0 aanstelling UMCN St Radboud ivm onderzoek |

n.v.t. |

n.v.t. |