Additioneel plaatsen van een patellacomponent bij TKP

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van het additioneel plaatsen van een patellacomponent bij een totale knieprothese?

Aanbeveling

Plaats een primaire totale knieprothese bij voorkeur zonder patellacomponent.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is controverse over de waarde van het gebruik van een patellacomponent bij het plaatsen van een totale knieprothese. Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van het wel of niet plaatsen van een patellacomponent. Als cruciale uitkomstmaten werden heroperatie, anterieure kniepijn en complicaties gedefinieerd. Patella resurfacing leek de kans op anterieure kniepijn te verminderen. De geïncludeerde literatuur gaf helaas geen indicatie over de ernst van de pijn. Er werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden in heroperatie tussen de beide behandelopties. Voor de uitkomstmaat complicaties konden geen conclusies worden getrokken door de zeer lage bewijskracht. De belangrijke uitkomstmaat kniefunctie leek niet verschillend tussen het wel en niet plaatsen van een patellacomponent. Voor het beoordelen van de overige belangrijke uitkomstmaten patiënttevredenheid en bewegingsuitslag was onvoldoende informatie beschikbaar in de geïncludeerde literatuur. De overall bewijskracht, de laagste bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten, is zeer laag. Dat betekent dat we zeer onzeker zijn over de kwaliteit van het bewijs. Er komt derhalve uit de literatuur geen duidelijke voorkeur naar voren voor het wel of niet plaatsen van een patellacomponent. Hier ligt een kennislacune.

In het verleden werd bij patiënten met reumatoïde artritis plaatsing van een patellacomponent overwogen. Gezegd dient te worden dat hiervoor geen specifieke subgroepanalyse is uitgevoerd. De werkgroep is van mening dat door de steeds beter wordende behandeling van het ziektebeeld van de reumatoïde artritis en de daardoor steeds minder aanwezige ernstige deformiteiten en botafwijkingen, ook in het kniegewricht, alleen het aanwezig zijn van de diagnose reumatoïde artritis niet een reden is om over te gaan tot het standaard plaatsen van een patellacomponent.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Voor de patiënt is pijnreductie meestal de belangrijkste reden voor het laten plaatsen van een primaire TKP. Het plaatsen van een patellacomponent zou mogelijk het risico op postoperatieve anterieure kniepijn reduceren. Echter, er wordt geen melding in de literatuur gemaakt over de mate van de reductie van de pijn. Tevens is de bewijskracht van deze stelling ‘Low Grade’. Reden voor de werkgroep om dit niet mee te nemen in de aanbevelingen, temeer omdat dit wel degelijk een forse kostenverhoging zou brengen voor de maatschappij vanwege de grote aantallen primaire TKP’s in Nederland (meer dan 25.000 in 2018 en 2019, LROI).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Indien men bij gelijke klinische uitkomsten puur kijkt naar de directe medische kosten, dan zijn de prothesekosten bij tevens plaatsen van een patellacomponent uiteraard hoger. Immers de patellaprothese dient extra aangeschaft te worden. Het ‘preventief’ plaatsen van een patellacomponent om geen kosten te hebben van een eventuele tweede operatie voor het plaatsen van alsnog een patellacomponent in geval van aanhoudende klachten, blijkt vanuit de literatuur niet te onderbouwen. Ook is er geen goede beslisboom om te definiëren wanneer een secundaire resurfacing zinvol is. De indicatie is erg afhankelijk van de inzichten van de behandelend arts en zullen daarom waarschijnlijk per kliniek variëren. Hierover zijn helaas geen gegevens beschikbaar.

De literatuur toont geen verminderd aantal heroperaties na het direct plaatsen van een patellacomponent bij een TKP.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het niet plaatsen van een patellaprothese bij een primaire TKP heeft voor de meerderheid van de orthopedisch chirurgen in Nederland geen verandering van de hedendaagse praktijk tot gevolg. In Nederland wordt slechts in de minderheid van de gevallen een patellaprothese geplaatst (22%, LROI 2018). Er zijn landen waar in veel grotere frequenties een patellacomponent wordt geplaatst (bijvoorbeeld USA 90%, Australië 60%, Denemarken 80%). Echter er zijn ook landen waar nog veel minder patellacomponenten worden geplaatst (Zweden en Noorwegen 2%; Ali, 2016).

Ook voor de patiënt zal het geen gevolgen hebben, het peroperatieve traject, opname en revalidatie zijn niet verschillend indien wel of geen patellacomponent wordt geplaatst.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is veel literatuur aanwezig over de waarde van het wel of niet additioneel plaatsen van een patellacomponent bij een primaire TKP. Echter de meeste onderzoeken en publicaties zijn niet goed wetenschappelijk van opzet of niet goed uitgevoerd. Derhalve bleven een systematische review en twee RCT’s overeind, die echter ook niet het complete antwoord geven. Zie hiervoor de conclusies met bewijskracht. Mogelijk is er bij bepaalde subgroepen wel een indicatie voor een primaire patellaprothese, echter tot op heden is dit nog niet duidelijk.

De werkgroep heeft besloten dat er onvoldoende bewijs is om te adviseren om bij iedere patiënt die een TKP krijgt, additioneel een patellacomponent te plaatsen. Dit overwegende heeft ons gebracht tot de volgende aanbeveling.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Patellofemorale (PF) klachten na het plaatsen van een TKP zijn, na infecties, de belangrijkste reden voor revisie van de prothese. De incidentie van deze klachten varieert tussen de 4 en 49% (Popoviv, 2003) waarschijnlijk als gevolg van verschillen tussen patiëntpopulaties, verschillen in prothese-ontwerp of operatieve techniek en verschillen in meetmethode.

De precieze oorzaak van de klachten is onbekend, maar mogelijk zou het plaatsen van een patellacomponent kunnen leiden tot minder kans op patellofemorale klachten. Er zijn drie behandelstrategieën:

- sommige orthopeden gebruiken altijd een patellacomponent;

- andere op indicatie (bijvoorbeeld in geval van ernstige retropatellaire artrose);

- weer anderen gebruiken nooit een patellacomponent.

Het is de vraag welke van de drie behandelstrategieën leidt tot de beste klinische resultaten en de laagste revisie kans.

Met betrekking tot de kans op revisie is belangrijk op te merken dat strategie 1, het altijd plaatsen van een patellacomponent, waarschijnlijk leidt tot de laagste revisiekans, om de simpele reden dat als er al een patellacomponent geplaatst is, een revisie om die reden geen optie meer is. De te beantwoorden vraag is dus: Is er op grond van de huidige literatuur voldoende bewijs voor het standaard plaatsen van een patellacomponent?

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

In total knee arthroplasty, patellar resurfacing does not seem to affect reoperation rate (for any reason/for AKP/for patellofemoral complications/for other complications) compared with patellar retention.

Bronnen: (Chawla, 2019; Ha, 2019; Teel, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

In total knee arthroplasty, patellar resurfacing may reduce the risk of postoperative anterior knee pain compared with patellar retention.

Bronnen: (Chawla, 2019; Ha, 2019; Teel, 2019) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether patellar resurfacing affects complication rate after total knee arthroplasty compared with patellar retention.

Bronnen: (Chawla, 2019; Ha, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

In total knee arthroplasty, patellar resurfacing does not seem to affect the postoperative knee component of the Knee Society Score compared with patellar retention.

Bronnen: (Chawla, 2019; Ha, 2019; Teel, 2019) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

In total knee arthroplasty, patellar resurfacing probably does not affect the postoperative function component of the Knee Society Score compared with patellar retention.

Bronnen: (Chawla, 2019; Ha, 2019; Teel, 2019) |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to grade the level of evidence for the outcomes postoperative Oxford Knee Score and Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score because individual study data were not reported. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to grade the level of evidence for the outcome postoperative patient satisfaction because individual study data were not reported. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to grade the level of evidence for the outcome postoperative range of motion because individual study data were not reported. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The systematic review (SR) and meta-analysis by Teel (2019) compared patellar resurfacing with patellar retention during total knee arthroplasty (TKA). English prospective RCTs comparing TKAs performed with patellar resurfacing to TKAs performed without patellar resurfacing in adults with a minimum of 2-year follow-up were included. Studies including bilateral TKAs were also included when randomized use of resurfacing was used. Exclusion criteria were the following: non-English language literature and non-randomized or quasi-randomized trials. MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Cochrane databases, BIOSIS, and Web of Science were searched from January 1980 to July 2017. Also bibliographies were scanned, and manual searches were performed for any missed papers. Twenty studies were included (see table 1). The following outcomes were reported:

- Knee Society Score (KSS): knee component and function component separately.

- Reoperation rates: (1) reported as reoperation for any reason, (2) reoperation for AKP, (3) reoperation for patellofemoral complications other than AKP (included, but not limited to, effusion/synovitis secondary to polyethylene wear, rupture of the quadriceps or patellar tendons, malrotation of the femoral or tibial component, osteonecrosis, subluxation, soft tissue impingement, patellofemoral instability, and patellar component loosening, failure, or fracture) and (4) reoperation for complications unrelated to the patellofemoral joint (defined as reoperation for any other reason including, but not limited to, infection, stiffness, lateral pain, and tibiofemoral loosening).

- Anterior knee pain (AKP).

- Patient satisfaction.

- Oxford Knee Scores (OKS).

- Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) sub-scores.

- Range of motion (ROM).

The criteria were decided based on discussion and descriptions of patellofemoral complications from previous meta-analyses. When studies about the same patient population were found, the study with the longest follow-up period was retained. Teel (2019) used a random-effects model in case heterogeneity was significant, and a fixed-effects model in case heterogeneity was not significant.

In addition, the RCT with five year follow-up of Chawla (2019) compared the effect of patellar resurfacing (PR) versus no patellar resurfacing (NPR) in the elderly. A total of 100 patients; 80 females (PR: 41, NPR: 39) and 20 males (PR: 9, NPR: 11) were included. Patients were followed postoperatively at 6-8 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years and 5 years. The following outcome measures were reported:

- KSS: which consists of 100 points scale for clinical score and 100-point scale for function score (poor: score below 60; fair: 60 to 69; good: 70 to 79; excellent 80 to 100). The clinical score comprises of pain, total range of flexion, flexion contracture (if present), extension lag, alignment (Varus & Valgus), and stability (Antero-posterior & Medio-lateral) parameters. The function score has points for walking, stair climbing and walking aid used.

- Anterior knee pain: assessment of anterior knee pain was done using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pre- and postoperatively.

- Positioning of components (component loosening, wear and patellofemoral problems including fracture or loosening of resurfaced patella, subluxation, dislocation and wear of a non-resurfaced patella). Standard anteroposterior and lateral view X-rays were taken preoperatively in all cases to measure the outcome measures.

- Any complications which developed.

In addition, the RCT of Ha (2019) was included. This study assessed the mid-term outcomes of patients after one-stage bilateral TKA performed with and without patellar resurfacing with at least five years of follow-up. A total of 66 patients (132 knees) were included in the study. The patients received patellar resurfacing and retention, respectively, on one knee and the other, randomly selected. Ultimately, 60 patients were included in the final analysis. Patients in the study cohort were 65.2 ± 5.4 (range 58 tot 70) years old. There were 38 women and 22 men. BMI was 23.8 ± 4.3 (range 18.9 to 28.2) kg/m2. Follow-up in months was 66.4 ± 3.2 (range 58 to 70). The following outcome measures were reported:

- KSS: the system consists of a 100-point scale for clinical status and a 100-point score for function.

- Feller Score: was used to evaluate the patellar function.

- Anterior knee pain: was evaluated during a simulated activity of daily living. Pain intensity was rated using a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 10 points, with 0 being no pain and 10 representing maximum pain. A score of above 5 was defined as anterior knee pain.

- Patellar clunk and function: alignment of the TKA components was evaluated by measuring the standard anteroposterior and lateral x-rays of the knee.

- Patient satisfaction: was assessed with questionnaires at each follow-up visit.

Results

Reoperation rates

Reoperation for any reason

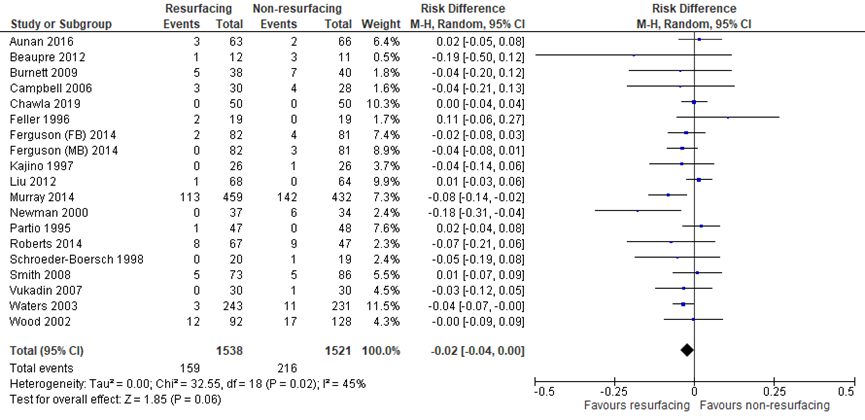

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included eighteen studies which described reoperation rates (for any reason). Burnett (2004) was removed from meta-analysis, because Burnett (2009) was a follow-up of the same population. In addition, Chawla (2019) reported reoperation rates for any reason. The pooled risk ratio (RR) for reoperation for any reason (PR: 1538, NPR: 1521) favored patellar resurfacing. The risk difference (RD) was -0.02, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from -0.04 to 0.00, was not clinically relevant (figure 1).

Figure 1 Reoperation for any reason after TKA with patellar resurfacing versus patellar non-resurfacing (risk difference)

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Sources: Teel (2019) and Chawla (2019)

Reoperation for anterior knee pain

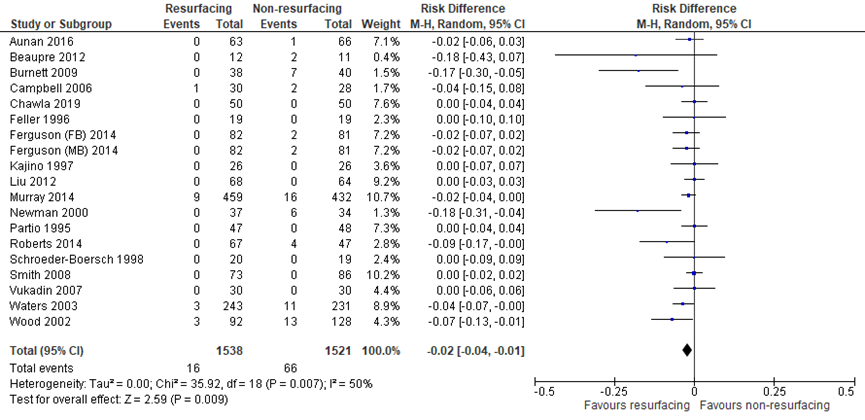

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included eighteen studies which reported reoperation for anterior knee pain (AKP). Burnett (2004) was removed from meta-analysis, because Burnett (2009) was a follow-up of the same population. In addition, Chawla (2019) reported reoperation rates for anterior knee pain. The pooled risk difference (RD) for reoperation for AKP (PR: 1538, NPR: 1521) favored patellar resurfacing (RD = -0.02, 95% CI -0.04 to -0.01). The difference (figure 2) was not clinically relevant.

Figure 2 Reoperation for anterior knee pain after TKA with patellar resurfacing versus patellar non-resurfacing (risk difference)

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Source: Teel (2019) and Chawla (2019)

Reoperation for patellofemoral complications (excluding AKP)

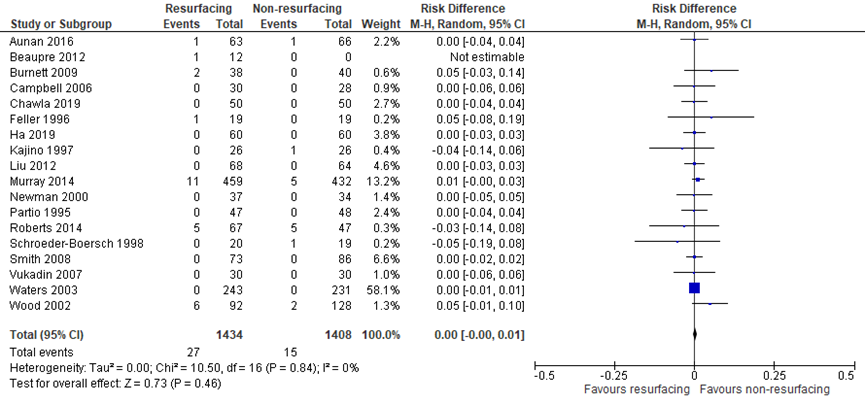

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included seventeen studies which reported the crucial outcome measure reoperation for patellofemoral complications (excluding AKP). Burnett (2004) was removed from meta-analysis, because Burnett (2009) was a follow-up of the same population. In addition, Chawla (2019) and Ha (2019) reported reoperation rates for patellofemoral complications (excluding AKP). The risk difference between the groups was not clinically relevant (PR: 1434, NPR: 1408; RD 0.00; 95% CI -0.00 to 0.01) as presented in figure 3.

Figure 3 Reoperation for patellofemoral complications (excluding AKP) after TKA with patellar resurfacing versus patellar non-resurfacing (risk difference)

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Source: Teel (2019), Chawla (2019), Ha (2019)

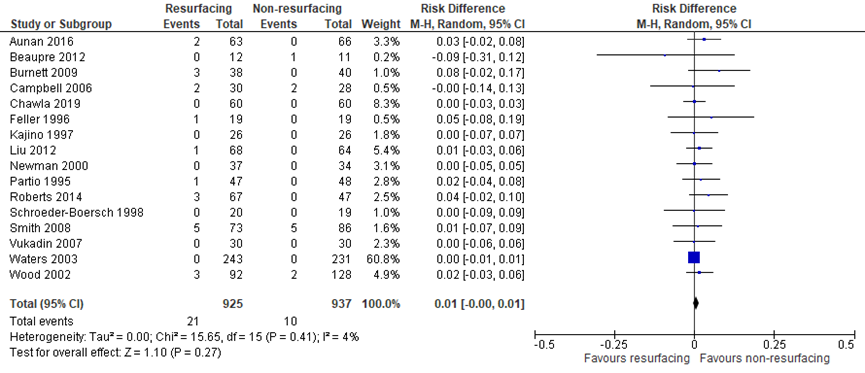

Reoperation for complications unrelated to the patellofemoral joint

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included seventeen studies which reported on the critical outcome reoperation for complications unrelated to the patellofemoral joint (figure 4). Burnett (2004) was removed from meta-analysis, because Burnett (2009) was a follow-up of the same population. In addition, Chawla (2019) reported reoperation for complications unrelated to the patellofemoral joint. The pooled risk difference (PR: 925, NPR: 937) was not clinically relevant (RD = 0.01, 95% CI -0.00 to 0.01).

Figure 4 Reoperation for complications unrelated to the patellofemoral joint after TKA with patellar resurfacing versus patellar non-resurfacing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Source: Teel (2019) and Chawla (2019)

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome reoperation (for any reason/for AKP/for patellofemoral complications/for other complications) was based on RCTs and started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels to low due to the very limited number of events (imprecision).

Anterior knee pain

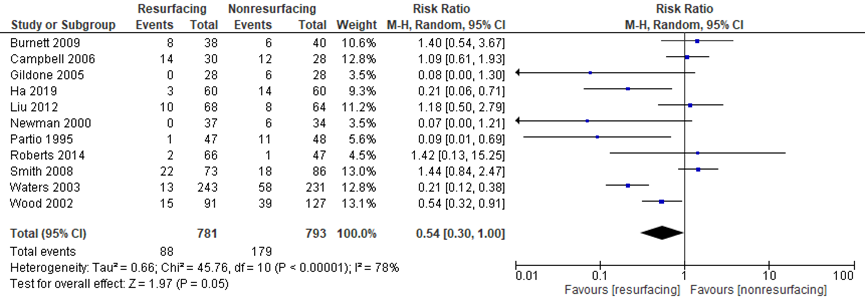

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included eleven studies which reported the important outcome anterior knee pain (AKP) as a dichotomous (yes/no) variable. Burnett (2004) was removed from meta-analysis, because Burnett (2009) was a follow-up of the same population. In addition, Ha (2019) reported anterior knee pain. The RR (PR: 800, NPR: 813) was clinically relevant (figure 5) in favor of resurfacing (RR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.00).

Figure 5 Anterior knee pain after TKA with patellar resurfacing versus patellar non-resurfacing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Source: Burnett, 2009; Campbell, 2006; Gildone, 2005; Ha, 2019; Liu, 2012; Newman, 2000; Partio, 1995; Roberts, 2014; Smith, 2008; Waters, 2003; Wood, 2002

In the study of Chawla (2019) the visual analogue scale (VAS) was used for anterior knee pain assessment pre- and postoperatively in both groups. There was no statistically significant difference in the pre- and postoperative period when compared between the two groups. Unfortunately, data were not reported. Therefore, clinical relevance could not be determined.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anterior knee pain was based on RCTs and started high. It was downgraded by two levels to low because of conflicting results (inconsistency) and due to the limited population size (imprecision).

Complications

The critical outcome measure complications were described in the study of Chawla (2019) and Ha (2019).

The study of Chawla (2019) reported no intra-operative complications in both groups. In the NPR group (50 patients): two patients developed wound dehiscence, one patient had a betadine allergy and one patient developed superficial wound infection. In the PR group (50 patients): one patient developed a superficial wound infection and one patient developed a deep wound infection in which the implant was removed an arthrodesis was done as a salvage procedure using Charnley’s clamps. In addition, Chawla (2019) reported that patellofemoral complications of patellar loosening, patellar fracture and patellar ligament rupture were not seen in either group due to short term follow up (5 years).

The study of Ha (2019) reported that there were no cases of patellar subluxation or dislocation, rupture of the quadriceps tendon, aseptic component loosening, patellar osteonecrosis, patellar fragmentation, or periprosthetic fracture in the included patients (n = 66; 132 knees).

Neither study described an effect measure (95% CI). Teel (2019) did not describe the outcome measure complications. Teel (2019) reported the outcome measure reoperation due to complications (see outcome measure reoperation).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome complications was based on RCTs and started high. It was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (short term follow up), the limited number of events and small study population (both imprecision).

Function (knee scores)

The knee component of the KSS

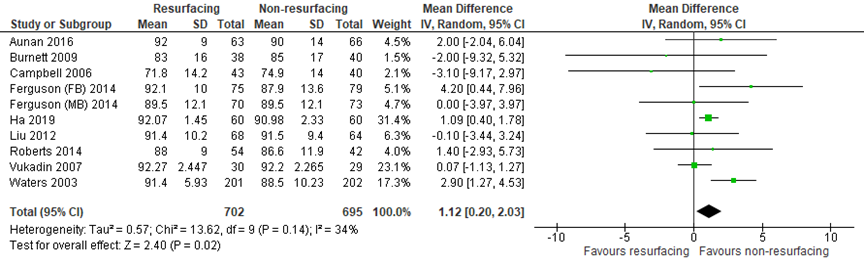

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included nine studies which described the knee component of the knee society score (KSS). Burnett (2004) was removed from meta-analysis, because Burnett (2009) was a follow-up of Burnett (2004). In addition, Chawla (2019) and Ha (2019) reported the important outcome measure.

The mean difference (MD) for the knee component of the KSS (PR: 702; NPR: 695) favored patellar resurfacing (MD = 1.12, 95% CI 0.20 to 2.03). The mean difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 6 The knee component of the KSS after TKA with patellar resurfacing versus patellar non-resurfacing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Source: Teel (2019) and Ha (2019)

Chawla (2019) also reported the mean knee component of the KSS at 5 years follow up. However, they did not report the standard deviation and mean difference (95% CI). Therefore, it was not possible to pool the results. Chawla (2019) reported that the clinical knee score improved from 28.6 to 84.14 in the PR group (n = 50), compared to 24.72 to 86.2 in the NPR group (n = 50). The difference in postoperative scores was not clinically relevant.

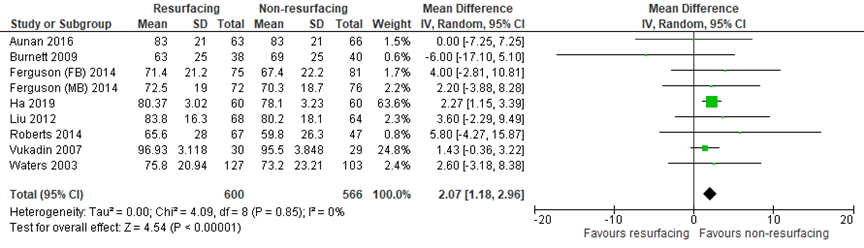

The function component of the knee society score

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included eight studies which described the function component of the KSS. Burnett (2004) was removed from meta-analysis, because Burnett (2009) was a follow-up of the same population. In addition, Chawla (2019) and Ha (2019) reported the important outcome measure.

The MD for the function component of the KSS (PR: 600; NPR: 566) favored patellar resurfacing (MD = 2.07, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.96). The MD was not clinically relevant.

Figure 7 The function component of the knee society score after TKA with patellar resurfacing versus patellar non-resurfacing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Source: Teel (2019) and Ha (2019)

Chawla (2019) also reported the mean functional knee score at 5 years follow up. However, they did not report the mean difference (95% CI). Therefore, it was not possible to pool the results. Chawla (2019) reported that the clinical knee score improved from 39.1 to 90.1 in the PR group (n = 50), compared to 45 to 92.4 in the NPR group (n = 50). The difference in the postoperative clinical knee score amongst the two groups was not clinically relevant at 5 years follow-up.

Oxford Knee Scores

The Oxford Knee Score (OKS) is a 12-item patient reported questionnaire designed and developed to assess function and pain after TKA.

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included three studies (PR = 227; NPR = 228) which reported on the important outcome OKS (Aunan, 2016; Ferguson (FB), 2014; Ferguson (MB), 2014). The MD for OKS was 1.15 (95% CI -0.46 to 2.76, P = 0.16). Teel (2019) did not report the mean (SD) per study. Chawla (2019) and Ha (2019) did not report the OKS.

Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score sub-scores

The Knee Injury Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) is a questionnaire designed to assess short and long-term patient-relevant outcomes following knee injury. The KOOS is self-administered and assesses five outcomes: pain, symptoms, activities of daily living, sport and recreation function, and knee-related quality of life.

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included two studies (PR = 96; NPR = 102) which reported the important outcome measure KOOS (Ali, 2016; Aunan, 2016). Teel (2019) reported that there was no statistically significant difference between the means for any of the KOOS sub-scores. Teel (2019) did not reported the mean (SD) per study. Chawla (2019) and Ha (2019) did not report the KOOS. Therefore, clinical relevance could not be determined.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure Knee Society Score (knee component) was based on RCTs and started high. It was downgraded by two levels to low because of conflicting results (inconsistency) and the limited population size (imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure Knee Society Score (function component) was based on RCTs and started high. It was downgraded by one level to moderate because the limited population size (imprecision). The level of evidence is considered moderate.

The level of evidence for the Oxford knee score and for Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (sub-scores) could not be determined due to lack of data from individual studies.

Patient satisfaction

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included nine studies (PR: 583; NPR: 545) which reported on the important outcome patient satisfaction (Ali, 2016; Aunan, 2016; Burnett, 2004; Burnett, 2009; Gildone, 2005; Roberts, 2015; Smith, 2008; Waters, 2003). The RR for patient satisfaction was 1.00 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.03, P = 1.00). Teel (2019) did not report the events (totals) per study.

Ha (2019) reported that 12 (20%) patients preferred the resurfaced side and six (10%) patients preferred the non-resurfaced counterpart, while 42 (70%) expressed no preference at three months after operation. However, at final follow-up (five years) 28 (47%) patients preferred the resurfaced side and 4 patients (7%) preferred the non-resurfaced side.

Chawla (2019) did not report patient satisfaction.

Level of evidence of the literature

Level of evidence for patient satisfaction could not be determined due to lack of data from individual studies.

Range of motion

The systematic review by Teel (2019) included four studies (PR = 249; NPR = 251) which reported the important outcome measure range of motion (ROM) (Burnett, 2009; Ferguson (FB), 2014; Ferguson (MB), 2014; Partio, 1995). The MD for ROM was -1.37 (95% CI -3.42 to 0.67, P = 0.19). Teel (2019) did not reported the mean (SD) per study. Chawla (2019) and Ha (2019) did not report the outcome measure range of motion.

Level of evidence of the literature

Level of evidence for range of motion could not be determined due to lack of data from individual studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of patellar resurfacing during total knee arthroplasty?

P: patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty;

I: patellar resurfacing;

C: patellar retention;

O: reoperation rates, anterior knee pain, complications, knee scores, patient satisfaction and range of motion.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered reoperation rates, anterior knee pain (AKP) and complications as critical outcomes for decision making; and function/knee scores, patient satisfaction, range of motion as important outcomes for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. As minimal clinically (patient) important differences, the working group used the GRADE-standard limit of 25% for risk ratios, 10% for VAS scales and function/knee scores and 0.5 for standardized mean differences. Risk ratios were described where possible. In case multiple studies reported no events in both groups, risk differences were used. A risk difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com), CINAHL (via EBSCO) and Pubmed (via Epubs) were searched with relevant search terms until March 23, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 480 hits: 138 SRs, 311 RCTs and 31 Epubs. SRs and RCTs about patients undergoing patellar resurfacing compared to patellar retention during total knee arthroplasty were selected. Based on title and abstract a total of 50 studies were selected. After examination of full text 47 studies were excluded and three studies, one SR (Teel, 2019) and two RCTs (Chawla, 2019; Ha, 2019) published after search date SR, were ultimately included in the literature summary.

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Ali A, Lindstrand A, Nilsdotter A, Sundberg M. Similar patient-reported outcomes and performance after total knee arthroplasty with or without patellar resurfacing. Acta Orthop. 2016 Jun;87(3):274-9. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2016.1170548. PMID: 27212102; PMCID: PMC4900081.

- Chawla L, Bandekar SM, Dixit V, Ambareesh P, Krishnamoorthi A, Mummigatti S. Functional outcome of patellar resurfacing versus non resurfacing in Total Knee Arthoplasty in elderly: A prospective five year follow-up study. Journal of arthroscopy and joint surgery. 2019;6(1): 65-69.

- Ha C, Wang B, Li W, Sun K, Wang D, Li Q. Resurfacing versus not-resurfacing the patella in one-stage bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Int Orthop. 2019;43(11):2519-2527. doi:10.1007/s00264-019-04361-7.

- LROI rapportage 2010-2018: https://www.lroi-rapportage.nl/knee-primary-knee-arthroplasty-total-knee-arthroplasty-prosthesis-characteristics-implantation-of-patella-2010-2018. October, 2020

- Teel AJ, Esposito JG, Lanting BA, Howard JL, Schemitsch EH. Patellar Resurfacing in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(12):3124-3132. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.07.019.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What is the effectiveness of patellar resurfacing during total knee arthroplasty?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Teel (2019) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search from January 1980 to July 2017

A: Ali, 2016 B: Aunan, 2016 C: Beaupre, 2012 D: Burnett, 2014 E: Burnett, 2009 F: Campbell, 2006 G: Feller, 1996 H: Ferguson, 2014 I: Ferguson, 2014 J: Gildone, 2005 K: Kajino, 1997 Study design: RCT (A – U)

Setting and Country:

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not described in systematic review for the individual studies (A-U)

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - English language literature, - minimum of 2-year follow-up, and

Exclusion criteria SR:

20 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Number of Knees Randomized (PR/NPR), mean age (PR/NPR) A: 74 patients (35/39), 68/69 B: 130 patients (64/66), 70/69 C: 38 patients (21/17), 64.9/62 D: 100 patients (50/50), 71/69 E: 118 patients (58/60), 65.3/67.1 F: 100 patients (46/56), 71/73 G: 40 patients (20/20), 70.5/71.1 H: 176 patients (88/88), 69.8 I: 176 patients (89/87), 70.2 J: 56 patients (28/28), 74.6/73.6

Sex: Not described in systematic review (A – U)

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: Stryker Triathlon B: Zimmer NexGen C: Smith & Nephew Profix D: DePuy AMK E: Zimmer Miller-Galante II F: Zimmer Miller-Galante II G: Howmedica PCA Modular H: DePuy Press Fit Condylar I: DePuy Press Fit Condylar J: Zimmer NexGen

|

Describe control:

Patellar retaining (A-U)

|

Mean Follow-Up Time

A: 6 year B: 3 year C: 10 year D: 10.8 year E: 10-12 year (range) F: 10 year G: 3.2 year H: 2 year I: 2 year J: 2.1 year K: 6.6 year For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) Not described in systematic review. There is only described that there was a low risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data in studies A-R and T-U. There was an unclear risk of bias in study R.

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as Knee Component of the KSS Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): B: 2.00 (-7.25, 7.25) D: -0.80 (-11.83, 10.23) E: -6.00 (-17.10, 5.10) F: -3.10 (-9.17, 2.97) H: 4.20 (0.44, 7.96) I: 0.00 (-3.97, 3.97) L: -0.10 (-3.44,3.24) Heterogeneity (I2): 34%

Outcome measure-2 Defined as Functional Component of the KSS

Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): B: 0.00 (-7.25, 7.25) D: -0.80 (-11,83, 10.23) E: -6.00 (-17.10, 5.10) H: 4.00 (-2.81, 10.81) I: 2.20 (-3.88, 8.28) L: 3.60 (-2.29, 9.49) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): MD 1.67 (95% CI 0.20 to 3.14) (P = 0.03) favoring patellar resurfacing Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-3 Defined as Anterior Knee Pain

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): D: 1.47 (0.56, 3.85) E: 1.40 (0.54, 3.67) F: 1.09 (0.61, 1.93) J: 0.08 (0.00, 1.30) L: 1.18 (0.50, 2.79)

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.66 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.19) (P = 0.17) favoring none of both Heterogeneity (I2): 78%

Outcome measure-4 Defined as Reoperation Relative Risk of Reoperation for any reason

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): B: 1.57 (0.27, 9.09) C: 0.31 (0.04, 2.52) D: 0.31 (0.07, 1.39) E: 0.75 (0.26, 2.17) F: 0.70 (0.17, 2.85) G: 5.00 (0.26, 97.70) H: 0.49 (0.09, 2.62) I: 0.14 (0.01, 2.69) K: 0.33 (0.01, 7.82) Pooled effect fixed effects model: RR 0.71 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.84) (P = 0.0001) favoring patellar resurfacing Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Defined as Relative Risk of Reoperation for AKP

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): B: 0.35 (0.01, 8.41) C: 0.18 (0.01, 3.47) D: 0.15 (0.01, 2.88) E: 0.07 (0.00, 1.19) F: 0.47 (0.04, 4.87) G: Not estimable H: 0.20 (0.01, 4.05) I: 0.20 (0.01, 4.05) K: Not estimable Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 0.28 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.45) (P < .00001) favoring none of both Heterogeneity (I2): 0% Defined as Relative Risk of Reoperation for patellofemoral complications (excluding AKP)

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): B: 1.05 (0.07, 16.39) C: 2.77 (0.12, 61.65) D: 3.23 (0.14, 76.98) E: 5.26 (0.26, 106.06) F: Not estimable G: 3.00 (0.13, 69.31) K: 0.33 (0.01, 7.82) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 1.55 (95% CI 0.90 to 2.67) (P =0.11) favoring none of both Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Defined as Relative Risk of Reoperation for nonpatellofemoral complications

Effect measure: RR (95% CI): B: 5.23 (0.26, 106.94) C: 0.31 (0.01, 6.85) D: 0.27 (0.03, 2.31) E: 7.36 (0.39, 137.90) F: 0.93 (0.14, 6.18) G: 3.00 (0.13, 69.31) K: Not estimable Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 1.54 (95% CI 0.84 to 2.81) (P=0.16) favoring none of both Heterogeneity (I2): 0% Patient satisfaction

Nine studies reported on patient satisfaction. The RR for patient satisfaction was not significant.

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): Heterogeneity (I2): unknown The test for heterogeneity was not significant (P = 0.47). Oxford Knee Score

Pooled effect (random effects model): Heterogeneity (I2): unknown

Outcome measure-8 Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

Outcome measure-7 Range of Motion (ROM)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): Heterogeneity (I2): unknown |

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))

Research question: What is the effectiveness of patellar resurfacing during total knee arthroplasty?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Chawla (2019) |

Type of study:

Setting and country: Hospital-based, India

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not described |

Inclusion criteria: Not described Exclusion criteria: History of patella fracture, age < 50 years, patellofemoral instability, prior patellectomy, prior knee replacement surgery, prior hip replacement surgery, patient with osteoarthritis of hip, prior history of tibial condyle or distal femoral fractures.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: Not described

Sex: I: 18 % Male C: 22 % Male

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

In cases of NRS, patelloplasty was done in which osteophytes were removed by trimming around patella and denervating it.

|

Length of follow-up: 5 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Not described

Incomplete outcome data: Not described

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mean clinical knee score (ranging form 0 to 100 points) in the PRS group improved from 28.6 to 84.14 and; from 24.72 to 86.2 in the NRS group. The difference in the clinical knee score amongst two groups was not statistically significant at 5 years follow up. However, increment in score was more in the NRS group compared to PRS group. Mean Knee Society Score: The mean knee society score (KSS) on scale ranging from 0 to 200 points in the resurfaced group improved from 67.76 to 174.24 and; went up from 69.76 to 178.6 in the non surfaced. P-value calculated using independent “t-test’with 96° of degrees of freedom is 0.9047, hence the difference in two groups is not statistically significant at 5 years follow up. It is clearly evident that increment in score was more in the NRS group compared to PRS group. Knee Score:

Resurfaced 41 (82%) Fair Poor By using simple interactive statistical analysis we found that all the sub headings in pre and postoperative groups when compared amongst resurfaced and non resurfaced groups have non significant p-value.

The statistic analysis was done using chi square test because the distribution was non normal. Zero Resurfacing 0 Non-resurfacing 0 One Non-resurfacing 0 Two Resurfacing 0 Non-resurfacing 0 Three Resurfacing 0 Non-resurfacing 0 Four Non-resurfacing 2 (4%) Five Resurfacing 3 (6%) Non-resurfacing 3 (6%) Six Non-resurfacing 9 (18%) Seven Resurfacing 13 (26%) Non-resurfacing 10 (20%) Eight Non-resurfacing 24 (46%) Nine Ten Non-resurfacing 1 (2%)

VAS postoperative: Zero Non-resurfacing 25 (50%) One Resurfacing 1 (2%) Non-resurfacing 3 (6%) Two Resurfacing 3 (6%) Non-resurfacing 4 (8%) Three Resurfacing 4 (8%) Non-resurfacing 3 (6%) Four Resurfacing 0 Non-resurfacing 0 Five Resurfacing 3 (6%) Non-resurfacing 2 (4%) Six Resurfacing 2 (4%) Non-resurfacing 2 (4%) Seven Resurfacing 3 (6%) Non-resurfacing 2 (4%) Eight Resurfacing 4 (8%) Non-resurfacing 3 (6%) Nine Resurfacing 2 (4%) Non-resurfacing 2 (4%) Ten Resurfacing 0 Non-resurfacing 0 VAS was used for the anterior knee pain assessment pre and post operatively in both groups. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the pre and post operative period when compared amongst the two groups.

Complications: There was no intra operative complication noted in either group. Two patients develop wound dishiscence, one patient had betadine allergy and one developed superficial wound infection in NRS group. In PRS group, one patient developed superficial wound infection and one developed deep wound infection in which the implant was removed an arthrodesis was done as a salvage procedure using Charnley’s clamps. The clamps were removed 3 months post operatively and weight bearing was started as tolerated. None of the patients underwent revision of total knee replacement after the primary procedure. The major patellofemoral complications of patellar loosening, patellar fracture and patellar ligament rupture was not seen in either group due to short term (5 years) follow up. Long term result and follow up are yet to be analysed. |

The arthroplasty was performed by senior surgeon following standard approach with medial parapatellar arthrotomy under combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia (CSEA). All patients received size specific femoral and tibial components. All components were cemented. Entire clinical and functional outcome was graded as following depending on the total Knee Society Score: Poor (score below 60), Fair (60 – 69), Good (70-79), Excellent (80 -100) |

|

Ha (2019) |

Type of study: a prospective randomize clinical trial

Setting and country: hospital based, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not described |

Inclusion criteria: - bilateral knee OA. Exclusion criteria: - previous patellectomy; - inflammatory arthritis; - patellar fracture; Patellar instability; -previous extensor mechanism procedures; - high tibial osteotomy; - severe valgus or varus deformity (>20°); - severe flexion contracture (>30°); - previous unicondylar knee replacement; - and history of septic arthritis or osteomyelitis.

N total at baseline: 66 Intervention: 66 knees (66 patients) Control: 66 knees (66 patients)

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I and C: 65.2 ± 5.4 (Range 58 – 70)

Gender: I and C: Male 38 (63.3) Female 22 (36.7)

BMI (kg/m2): 23.8 ± 4.3 (Range: 18.9 – 28.2)

Follow-up (months): 66.4 ± 3.2 (Range: 61 – 78)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

When resurfacing was not performed, the so-called patelloplasty was carried out, including osteophyte removal and smoothing of fibrillated cartilage. |

Length of follow-up: The patients were followed post-operatively at three months and annually thereafter (minimum 5 years analysis).

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 6 (9%) Reasons:

Control: 6 (9%) Reasons: One patient died of cerebral haemorrhage within five years of follow-up and four were lost to follow-up. Ine patient developed severe dementia and was excluded.

Incomplete outcome data: Not described

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

The lateral retinaculum was released in no patients. KSS scores: Clinical scores 3 months after operation

1 year after operation PR: 79.12 ± 3.22

2 years after operation PR: 87.32 ± 2.52

3 years after operation PR: 89.70 ± 1.81

4 years after operation PR: 90.80 ± 1.59

5 years after operation PR: 92.07 ± 1.45 t = 1.03 Time effect F = 5243,14 P < 0,001 Main effect F = 17.57, P < 0,001

Function scores 3 months after operation

1 year after operation PR: 59.73 ± 4.89

2 years after operation PR: 64.33 ± 2.94

3 years after operation PR: 69.87 ± 3.64

4 years after operation PR: 78.02 ± 3.19

5 years after operation PR: 80.37 ± 3.02 t = − 1.46 Time effect F = 2238.28, P < 0.001 Main effect F = 15.81, P < 0.001

Feller scores: Preoperation 3 months after operation

1 year after operation PR: 21.67±2.38

2 years after operation PR: 22.68±2.22

3 years after operation PR: 22.77±2.09

4 years after operation PR: 23.35±2.23

5 years after operation PR: 23.87±2.05 t=0.051 Time effect F=193.92, P <0.001 Main effect F=18.06, P <0.001

Anterior knee pain (within 3 months of surgery): PR: 3 (5%) N-PR: 14 (23%) With time, the rate of AKP gradually decreased in both groups. One patient had similar pain intensity in the bilateral knee at the last follow-up. No patients with persistent pain showed symptoms severe enough to require further surgery.

Patellar clunk syndrome rates: PR: 6 (10%) P value < 0,001

Radiographic findings: Preoperative alignment: N-PR: Varus -5.45°±0.98°

Postoperative alignment: PR: Valgus 5.82°±1.13° N-PR: Valgus 5.78°±1.04°

Preoperative Insall-Salvati index PR: 1.05 ± 0.18 N-PR: 1.04 ± 0.16

Postoperative Insall-Salvati index PR: 1.01 ± 0.09 N-PR: 1.02 ± 0.07

Preoperative patellar tilt angle PR: 6.03°± 1.12 N-PR: 5.98°± 1.24

Postoperative patellar tilt angle PR: 4.98°± 1.08 N-PR: 4.45°± 1.12

Change in joint line in reference tibial tuberosity (mm)

PR: 2.41 ± 1.22 N-PR: 2.76 ± 1.65

Complications:

Patient satisfaction: 12 (20%) patients affirmed to prefer the resurfaced side and six (10%) preferred the non-resurfaced counterpart, while 42 (70%) expressed no preference at three months after operation. However, with follow-up time, more and more patients preferred the resurfaced side (47%) and only 7% patients preferred the non-resurfaced side at the final follow-up. |

All patients were operated by a single surgeon (Kang Sun) using Scorpio NRG knee prostheses (Stryker, USA). The tourniquet was tied to the proximal thigh pre-operatively. A midline skin incision and the and the medial parapatellar approach were used, preserving the infrapatellar fat pad. Tibial bone cuts as well as distal and posterior femoral bone cuts were performed according to mechanical and anatomical axis measurements in each patient. Femoral component rotation was oriented parallel to the transepicondylar axis. The rotation reference for the tibial component was the medial half of the tibial tuberosity. The patellar cut was performed with an oscillating saw on the patellar clamp. Calipers were used to measure the patellar thickness intra-operatively in an attempt to restore the baseline composite height in all resurfacing procedures. An assessment of patellar tracking was carried out by the no thumb test; if necessary, a lateral retinaculum release was performed. Patellar thicknesses before and after resurfacing were measured. for three days to prevent infection. For thromboprophylaxis, all patients were administered subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) at a dose of 4000 AxaIU (0.4 ml)/day, starting 12 hours after the operation. All patients were administered physical rehabilitation therapy by the same rehabilitation technologist, as reported previously. |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Research question: What is the effectiveness of patellar resurfacing during total knee arthroplasty?

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?

Yes/no/unclear/ not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Teel, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

No (only a flow diagram of the searching and screening process available; not an reason of exclusion per reference available) |

Yes |

Not applicable (only RCTs included) |

Yes (Cochrane Collaborations’tool) |

Unclear ((1) implant design was variable among studies; (2) different surgeons with variation in skill level; (3) wide range of follow-up times (from 2 to 10 years, but (4) assessment of statistical heterogeneity) |

No (no test values or funnel plot included) |

Unclear (sources of support only reported for the systematic review) |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: Research question: What is the effectiveness of patellar resurfacing during total knee arthroplasty?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Chawla (2019) |

A total of 100 subjects were evaluated prospectively between June 2011 to May 2013 at Department of Orthopaedic Surgery (Goa Medical College and Hospital) followed by approval of ethical committee. Subjects were further randomized equally into two arms by using standard computer-generated random table. Each arm was designated to either PRS or NRS one day prior to surgery. |

Unclear (In Chawla (2019) was nothing described about the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process.) |

Unclear (In Chawla (2019) was nothing described about the blinding of the patients.)

|

Unlikely (In Chawla (2019) was nothing described about the blinding of the care providers. However, blinding of the care provider (attending physician) is not possible because two types of surgical treatments were compared). |

Unclear (In Chawla (2019) was nothing described about the blinding of the outcome assessors.) |

Unlikely (All outcomes described in the methods section were also reported in the results section.) |

Unclear (The number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, were not reported.) |

Unclear (For some outcomes it is unclear when they were measured.) |

|

Ha (2019) |

A statistical expert blinded to the research procedure generated a random number sequence using a computer. To conceal randomization outcomes, the allocated numbers were placed into concealed opaque envelopes. Randomization was accomplished by opening a randomly selected envelope in the operation room after femoral and tibial cuts, immediately prior to patellar preparation. The left knee received the treatment indicated by the envelope, while the contralateral knee (right knee) received the alternative treatment; either way, the surgery started with the left knee. Thus, all patients had one patella resurfaced and the contralateral patella non-resurfaced |

Unlikely (A statistical expert blinded to the research procedure generated a random number sequence using a computer.) |

Unlikely (The patients were blinded to the surgical procedure.) |

Unlikely (It was not possible to blind the surgeon, however an evaluator not involved in the study design but familiar with the assessment tools was responsible for data collection.) |

Unlikely (An evaluator not involved in the study design, but familiar with the assessment tools was responsible for data collection.) |

Unlikely (All outcomes described in the methods section were also reported in the results section.) |

Unlikely (6 patients were lot to follow-up; reasons were described in the article) |

Unclear (For some outcomes it is unclear when they were measured.) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Systematic reviews |

|

|

Grassi (2018) |

Meta-analysis of systematic reviews |

|

Tang (2018) |

More recent systematic review available (Teel, 2019) |

|

Longo (2018) |

Also other types of studies included (no RCTs) |

|

Arirachakaran (2015) |

Also quasi-experimental studies included |

|

Chen (2013) |

More recent systematic review available (Teel, 2019) |

|

Hu (2013) |

Commentary |

|

van Jongbergen (2014) |

Determinants of anterior knee pain |

|

Meijer (2015) |

Economic analysis |

|

Antholz (2015) |

More recent systematic review available (Teel, 2019) |

|

Findlay (2016) |

Erratum |

|

Michalik (2016) |

Descriptive study |

|

Frase (2017) |

Descriptive study |

|

Duan (2018) |

Determinants of anterior knee pain after total knee arthroplasty |

|

Khan (2019) |

Protocol |

|

Schindler (2012) |

Descriptive study |

|

Dunbar (2012) |

Descriptive study |

|

Schiavone Panni (2014) |

Descriptive study |

|

Park (2015) |

Descriptive study |

|

Findlay (2016) |

Effectiveness of different techniques for non-resurfacing |

|

Tishelman (2019) |

Other patients (patellofemoral syndrome; Jumper’s knee) |

|

Pilin (2012) |

More recent systematic review available (Teel, 2019) |

|

Migliorini (2019) |

Also quasi-experimental studies included |

|

Epub |

|

|

Crwaford (2019) |

Retrospective study |

|

Coory (2020) |

Observational study (data of the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry used) |

|

Feng (2020) |

Observational study |

|

RCT |

|

|

Agarwala (2018) |

No RCT (prospective comparative study) |

|

Eshnazarov (2016) |

Other outcome measures (radiologic outcomes) |

|

Hu (2013) |

Commentary |

|

Kai (2013) |

Commentary |

|

Koh (2019) |

Other comparison (new versus old implants) |

|

Liddle (2013) |

Commentary |

|

Murray (2014) |

Included in Teel (2019) |

|

Thiengwittayaporn (2019) |

Follow-up 1 year |

|

Vukadin (2017) |

Included in Teel (2019) |

|

Ye (2013) |

Commentary |

|

Zmistowski (2019) |

Systematic review (focused on costs; outcome measures: persistent postoperative, anterior knee pain, reoperation, utility scores, costs) More outcome measures decribed in Teel (2019). |

|

Aunan (2016) |

Included in Teel (2019) |

|

Aunan (2016) |

Same study as above |

|

Beaupre (2012) |

Included in Teel (2019) |

|

Kaseb (2018) |

Follow-up 6 months |

|

Roberts (2015) |

Included in Teel (2019) |

|

Ali (2016) |

Included in Teel (2019) |

|

Hernández (2018) |

No RCT |

|

Korkmaz (2019) |

No RCT |

|

Liu (2012) |

Included in Teel (2019) |

|

Chawla (2019) |

Follow-up less than 2 year (mean follow-up 9 months) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 08-09-2021

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 31-08-2021

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Deze richtlijn beoogt een leidraad te geven voor de dagelijkse praktijk van primaire totale knievervanging. In de conclusies wordt aangegeven wat de wetenschappelijke stand van zaken is. De aanbevelingen zijn gericht op optimaal medisch handelen en zijn gebaseerd op de resultaten van wetenschappelijk onderzoek en overwegingen van de werkgroep, waarbij de inbreng door patiënten is meegenomen (patiëntenperspectief). Het doel is een hogere kwaliteit en meer uniformiteit in behandelingsstrategie, en het verminderen van praktijkvariatie. Daartoe is een duidelijke indicatiestelling (tweede lijn) noodzakelijk. Doel van de richtlijn is met name ook het verminderen van postoperatieve pijn en verbeteren van de gewrichtsfunctie door optimalisatie van de zorg en het creëren van reële verwachtingen van de patiënt. Het identificeren van kennislacunes zal richting kunnen geven aan nieuw wetenschappelijk onderzoek en nieuwe ontwikkelingen. Tot slot is naar aanleiding van de noodzaak tot beheersing van de verdere groei van kosten in de gezondheidzorg aandacht besteed aan kosten en kosteneffectiviteit.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle zorgverleners die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met (indicatie voor) een TKP. De richtlijn is tevens van belang voor de patiënt, ter informatie en ten behoeve van shared-decision making.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg rondom de totale knieprothese (TKP).

Werkgroep

- Drs. H. (Hennie) Verburg, orthopedisch chirurg in Reinier Haga Orthopedisch Centrum (voorzitter), NOV

- Dr. ing. S.A.W. (Sebastiaan) van de Groes, orthopedisch chirurg in Radboudumc, NOV

- Drs. D. (Daniël) Hoornenborg, orthopedisch chirurg bij XpertOrthopedie, NOV

- Dr. D.A. (Derk) van Kampen, orthopedisch chirurg in Dijklander Ziekenhuis, NOV

- Dr. G. (Geert) van der Sluis, fysiotherapeut / programmaleider onderzoek en innovatie bij ziekenhuis Nij Smellinghe in Drachten, KNGF

- N. (Nique) Lopuhaä, beleidsmedewerker Patiëntbelangen, ReumaNederland

- mr. J.M. (Jacqueline) Otker, patiëntpartner Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland.

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. M.S. (Matthijs) Ruiter, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. S.N. (Stefanie) Hofstede, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Verburg (voorzitter) |

Orthopedisch Chirurg, Renier HAGA Groep |

Voorzitter bestuur Werkgroep Knie van de NOV |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hoornenborg |

Orthopedisch chirurg XpertOrthopedie |

Ik geef 1 keer per jaar een AIOS cursus knie voor Arthrex (dat gaat over kruisband-operaties, ik heb met Arthrex geen relatie voor knieprotheses). Hiervoor word ik betaald volgens de richtlijnen. |

geen |

Geen actie |

|

Lopuhaä |

Beleidsmedewerker Patiëntenbelangen ReumaNederland |

geen |

geen |

Geen actie |

|

Otker |

Ervaringsdeskundige Longfonds, Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland en Patientenfederatie Nederland (allen onbetaald); Cliëntenraad Ciro Horn (revalidatie centra chronische longziekten) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van de Groes |

Orthopedisch chirurg in Radboudumc |

Lid commissie wetenschap en innovatie NOV (onbetaald). Lid accreditatie commissie NOV (onbetaald), Lid raad wetenschap en innovatie FMS (onbetaald), Maatschapslid universitair orthopedisch expertise centrum Nijmegen (betaald). |

geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van der Sluis |

Programmaleider onderzoek en innovatie bij ziekenhuis Nij Smellinghe |

beroepsinhoudelijk lid regionaal tuchtcollege te Zwolle (vacatievergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Kampen |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Dijklander ziekenhuis |

Consultant voor Exactech: +/- 2 keer per jaar geef ik een cursus over deze schouder prothese. (equinoxe). Hiervoor word ik betaald volgens de richtlijnen. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en andere relevante patiëntenorganisaties uit te nodigen voor de Invitational conference. Het verslag hiervan (zie die bijlagen) is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen. Daarnaast werd het patiëntenperspectief vertegenwoordigd door afvaardiging van ReumaNederland en Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland in de werkgroep. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de relevante patiëntenorganisaties en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met een TKP. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodule (NOV, 2014) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door een Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Kunz R, Craig J, Montori VM, Bossuyt P, Guyatt GH; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008 May 17;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008 May 24;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139.

Schünemann, A Holger J (corrected to Schünemann, Holger J). PubMed PMID: 18483053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2386626.

Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016 Oct;104(4):320-324. PubMed PMID: 27822157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5079497.