Vochtbeleid

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van behandeling gericht op vochtbeleid bij patiënten met een aneurysmatische SAB?

Aanbeveling

Houd dagelijks de vochtbalans bij, zowel op de verpleegafdeling als op de IC. Maak de balans bij voorkeur elke 6 tot 8 uur op om op dagniveau (24 uur) te kunnen bijsturen waar nodig.

Start met 3L totale vochttoediening op de dag van opname. Streef vervolgens naar een balans tussen totale vochttoediening (=alle infuusvloeistoffen, sondevoeding en vocht als oplosmiddel voor medicatietoediening) en vochtexcretie (onder andere diurese). Bij de standaard patiënt komt dit ongeveer overeen met een gemiddelde neutrale vochtbalans van 0 tot +500 ml/dag (mede in aanmerking genomen de geschatte vochtverdamping). Stem daartoe de vochttoediening af op de diurese. Bereken neutrale vochtbalansen bij voorkeur over meerdere dagen, waarbij er variaties op dagniveau kunnen zijn.

Streef bovenstaande na met zo min mogelijk vochttoediening (uitleg: neutrale vochtbalans middels een verhouding vochttoediening/vochtexcretie van 3L/3L is te prefereren boven 5L/5L).

Houd bij overname van een patiënt van de IC naar de verpleegafdeling rekening met de totale vochtbalans tijdens de IC opname bij het bepalen van acceptabele vochtbalansen in de dagen na de overplaatsing.

Overweeg invasieve hemodynamische monitoring (bijvoorbeeld met transpulmonale thermodilutie/PiCCO) toe te passen met als doel het bereiken van normovolemie bij aneurysmatische SAB patiënten met een klinische indicatie voor opname op een intensive care en/of aanwijzingen voor longoedeem of verminderde cardiale functie en/of invasieve beademing en/of spontaan sterk verhoogde diurese (> 4 L/dag welke niet een uiting is van eerdere overvulling en waarbij neutrale vochtbalans niet lukt).

Maak gebruik van kristalloïden als standaard infuusvloeistof, boven colloïdale vloeistoffen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van behandeling gericht op vochtbeleid voor patiënten met een behandelde subarachnoïdale bloeding (SAB). Er werd daarbij onderscheid gemaakt tussen geavanceerde hemodynamische monitoring (b.v. met PiCCO ofwel transpulmonale thermodilutie), versus standaardmonitoring (met alleen vochtbalansen), hypervolemie versus normovolemie en er werd een vergelijking van verschillende vloeistofsamenstellingen gedaan. Delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) en neurologische uitkomst werden gedefinieerd als cruciale uitkomstmaten. Als belangrijke uitkomstmaten werd gekeken naar mortaliteit, verblijfsduur in het ziekenhuis, cardiopulmonale complicaties en kwaliteit van leven.

Op basis van 3 gerandomiseerde studies lijkt circulatoir management (synoniem: volume status management) op basis van geavanceerde hemodynamische monitoring met PiCCO DCI te verminderen en neurologische uitkomst bij patiënten te verbeteren ten opzichte van standaard monitoring. Ook de uitkomstmaten mortaliteit, verblijfsduur in het ziekenhuis en cardiopulmonale complicaties leken in het voordeel te zijn van PiCCO monitoring. De totale bewijskracht voor de vergelijking tussen deze vormen van monitoring was laag door beperkte patiëntaantallen en brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen. Voor de vergelijking tussen niet-gekalibreerde arteriële polsgolf analyse en standaard monitoring werd slechts een pilotstudie gevonden. Er konden geen conclusies worden getrokken door de zeer lage bewijskracht.

De effectiviteit van hypervolemie (als onderdeel van HHH therapy) ten opzichte van standaardzorg werd beschreven in een systematische review die 3 RCT’s includeerde. Voor deze vergelijking gold dat de bewijskracht voor de cruciale en belangrijke uitkomstmaten op zeer laag uitkwam door heterogeniteit in de interventies, beperkte patiëntaantallen en brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen die de grenzen van klinische besluitvorming overschreden. Concluderend lijkten zowel hypervolemie als Triple-H therapie obsoleet, want onvoldoende onderzocht en wordt het daarom niet geadviseerd door de werkgroep. Daarbij dient wel opgemerkt te worden dat hypovolemie geassocieerd is met cerebrale ischemie en een slechtere neurologische uitkomst en dus vermeden dient te worden.

Voor de vergelijking van verschillende vloeistofsamenstellingen werd 1 gerandomiseerde studie gevonden. In deze studie leek euvolemische behandeling met een colloïd (HES 130/0.4 ofwel Voluven) om de kans op een slechte neurologische uitkomst te verminderen ten opzichte van behandeling met een Ringer lactaat oplossing geen voordeel te hebben. Op het gebied van mortaliteit werden geen verschillen gevonden tussen de behandelingen. De andere uitkomstmaten werden niet gerapporteerd. Door het ontbreken van informatie over de cruciale uitkomstmaat DCI was de overall bewijskracht van deze studie zeer laag.

Van alle vergelijkingen was de overall bewijskracht laag (voor hemodynamische monitoring middels PiCCO) tot zeer laag. Hier ligt een kennislacune. De aanbevelingen zullen daarom gebaseerd worden op aanvullende argumenten waaronder expert opinion, waar mogelijk onderbouwd met (indirecte) literatuur.

Het is inmiddels algemeen aanvaard dat hypovolemie moet worden vermeden in patiënten met een aneurysmatische subarachnoïdale bloeding (vdJagt, 2016). Hypervolemie kan echter ook nadelige effecten hebben zoals decompensatio cordis en pulmonale complicaties. Mogelijk heeft hypervolemie eveneens een nadelig effect op de neurologische uitkomst na een SAB (vdJagt, 2016). De definitie van hypervolemie in deze is lastig, zeker aangezien een volume-overbelasting van het brein (met cerebraal oedeem) moeilijk in de dagelijkse klinische praktijk vast te stellen is. Van oudsher wordt gestreefd naar een positieve vochtbalans. De totale vochtbalans zegt helaas weinig over de daadwerkelijke volumestatus van de patiënt (Hoff, 2008). De werkgroep is van mening dat bij overmatige diurese (of noodzaak tot toediening van meer dan 4 liter totaal vocht intake per dag voor het bereiken van een neutrale vochtbalans) invasieve hemodynamische monitoring overwogen kan worden, zeker indien de patiënt al op de IC ligt.

De AHA/ASA richtlijn over subarachnoïdale bloedingen uit 2012 (Connolly, 2012) vermeldt dat monitoring van de volume status middels een combinatie van centraal veneuze druk, wiggedruk en vochtbalans kan worden overwegen met als doel euvolemie te bewerkstelligen. Profylactische hypervolemie wordt afgeraden. De Neurocritical Care Society suggereert in hun richtlijn uit 2011 (Diringer, 2011) ook dat diverse manieren van monitoring van de volumestatus kunnen worden overwogen om euvolemie te bereiken. Er kon geen aanbeveling worden gemaakt met betrekking tot een voorkeur voor het type monitoring (invasief danwel non-invasief). Hierbij werd volume-management zuiver gebaseerd op een centraal veneuze druk afgeraden. Het gebruik van een swan-ganz catheter brengt aanvullende risico zoals een longinfarct met zich mee en hierover bestaan geen goede studies. Een consensus statement over multimodale monitoring geformuleerd door de Neurocritical Care Society en de European Society of Intensive Care Medicine uit 2014 vult dit verder aan (Le Roux, 2014). Hierin wordt geadviseerd aanvullende monitoring te gebruiken bij hemodynamisch instabiele patiënten zonder een specifieke voorkeur voor het type monitoring.

Transpulmonale thermodilutie (PiCCO) lijkt een betrouwbare invasieve hemodynamische monitortechniek die niet gepaard gaat met grote, relevante risico’s. Mogelijk kan deze techniek de neurologische uitkomsten van SAB-patiënten verbeteren (Mutoh, 2009; Mutoh, 2014; vdJagt, 2016; Anetsberger, 2020), zoals reeds eerder beschreven. Een prospectieve studie van Tagami (2014) bepaalde bij 180 SAB-patiënten een globaal eind-diastolisch volume index (GEDVI) door middel van transpulmonale thermodilutie (PiCCO) en vond dat een GEDVI net boven de normaalwaarde (> 822 ml/m2, normale range 680- tot 00 ml/m2) geassocieerd was met een afname in DCI, waarbij een ruim verhoogde GEDVI (> 921 ml/m2) geassocieerd was met longoedeem. Yoneda (2013) vond in een multicenter prospectief cohort van 204 SAB-patiënten dat zowel de extravasculaire longwater index (ELWI), de pulmonale vasculaire permeabiliteit index (PVPI) en systematische vaatweerstand index (SVRI) veel hoger waren bij patiënten met een ernstige SAB terwijl de cardiac index lager was in deze groep. Patiënten die DCI ontwikkelden hadden een lagere GEDVI. Aanvullende studies zijn nodig om deze referentiewaarden verder te onderbouwen, maar wellicht kunnen waardes verkregen met transpulmonale thermodilutitie helpen euvolemie bij SAB patiënten te bewerkstelligen en te behouden.

Transpulmonale thermodilutie is daarnaast een veilige en betrouwbare hemodynamische monitoring techniek gebleken in een verscheidenheid aan patiëntpopulaties (Vinciguerra, 2017; Slagt, 2014). Al met al lijkt zowel de bestaande evidentie op basis van 3 trials in het voordeel van het gebruik van PiCCO, en tevens lijkt er een gunstig effect te bestaan voor het terugdringen van vochtintake (Mutoh, 2009; Mutoh, 2014; Anetsberger, 2020 en Vergouw, 2020). Dit lijkt te suggereren dat hemodynamische monitoring ertoe bijdraagt dat zowel hypo- als hypervolemie kan worden voorkomen en dat de negatieve consequenties van beiden op de perfusie en oxygenatie van de hersenen wordt beperkt. Alternatieve manieren van hemodynamische monitoring (bv uncalibrated wave form analyse) kunnen eventueel, afhankelijk van de lokale gebruiken, worden overwogen mits dezelfde doelen worden nagestreefd ten aanzien van de volume status (normovolemie). Echter goed onderzoek daarover ontbreekt, maar aangezien de principes van de monitoring sterk overlappen met die van PiCCO methode, zijn dergelijke alternatieven te overwegen.

Enkele studies vonden een associatie tussen de cumulatieve vochttoediening en DCI/neurologische uitkomst (Vergouw, 2020; Rass, 2019), waarbij er geen associatie bestond met de totale vochtbalans. Van belang is te melden dat er in de studies van Egge en Lennihan een duidelijk verhoogde centraal veneuze druk bestond in de hypervolemie groep die meer vocht kregen toegediend, ondanks gelijke vochtbalans, hetgeen gedeeltelijk een verklaring zou kunnen vormen voor de verhoogde kans op complicaties (namelijk: verhoogde veneuze drukken). Echter, het staat wel vast dat invasieve hemodynamische monitoring de vochtinname kan beperken (Mutoh, 2014; Anetsberger, 2020; Vergouw, 2020) zonder nadelige effecten en waarschijnlijk voordeel op uitkomsten.

Dit alles in ogenschouw nemend is de werkgroep van mening dat aanvullende (non)invasieve hemodynamische monitoring aangewezen is in hemodynamisch instabiele SAB-patiënten, of patiënten met ernstige complicaties zoals stress cardiomyopathie of neurogeen longoedeem en kan worden overwogen bij SAB-patiënten die een verhoogd risico lopen op complicaties en slechtere uitkomst (met name patiënten met een opname-indicatie op de intensive care, waar hemodynamische monitoring tot de routine zorg behoort, of bijvoorbeeld de ernstig cardiaal belaste SAB-patiënt of ‘poor grade’ patiënt); ondanks dat er slechts een lage (voor PiCCO) tot zeer lage bewijskracht (niet-gekalibreerde arteriële polsgolf analyse) werd gevonden voor het gebruik van hemodynamische monitoring in de analyses uitgevoerd binnen deze richtlijn.

De werkgroep kan daarbij op basis van de huidige literatuur geen sterk advies geven over de te hanteren aanvullende monitortechniek. Echter, het valt te overwegen een transpulmonale thermodilutie techniek (meest gebruikt is de PiCCO monitor) te gebruiken, gezien de uitgebreide ervaring hiermee in de huidige literatuur zoals boven beschreven, de bewezen betrouwbaarheid in andere patiëntpopulaties en de relatief lage risico’s die met deze techniek gepaard gaan (bijvoorbeeld minder invasief dan een Swan-Ganz catheter).

De werkgroep beveelt aan crystalloiden te gebruiken en colloiden te vermijden (MacDonald, 2008). Voor het gebruik van albumine (ook een colloidale vloeistof) werd geen bewijs gevonden.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Invasieve hemodynamische monitoring (middels een PiCCO) betekent voor patiënten dat er een speciale katheter nodig is (bij voorkeur in de a. femoralis) en een centraal veneuze lijn. SAB-patiënten die een indicatie hebben voor dergelijke hemodynamische monitoring hebben eveneens een indicatie voor opname op de Intensive Care, alwaar een centraal veneuze lijn en aan arterielijn over het algemeen überhaupt geïndiceerd zijn. De extra belasting voor de patiënt is daarmee beperkt en op basis van de huidige literatuur lijkt er een meerwaarde voor aanvullende invasieve hemodynamische monitoring te bestaan om de (neurologische) uitkomst te verbeteren. Ook voor niet-gekalibreerde arteriële polsgolf analyse is een arterielijn nodig, echter is daar vooralsnog geen eenduidig bewijs dat het de uitkomst verbetert.

De werkgroep is van mening dat de interventie opweegt tegen de belasting van de patiënt indien er sprake is van een hemodynamisch instabiele SAB patiënt, danwel SAB patiënten met een hoog risico op complicaties of een slechte uitkomst (zoals de cardiaal belaste patiënt). Bij een hemodynamische stabiele, neurologische goede SAB patiënt waarvoor geen IC opname indicatie bestaat, weegt de belasting voor de patiënt niet op tegen de baten zoals gevonden in de huidige literatuur. Voor reeds op een IC opgenomen patiënten geldt dit niet en spelen andere overwegingen, waardoor laagdrempeliger PiCCO monitoring kan worden toegepast.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het gebruik van PiCCO apparatuur gaat gepaard met substantiële (aanschaf) kosten. In veel centra in Nederland is dergelijke apparatuur echter al aanwezig. De werkgroep is van mening dat er ook voor alternatieve, vergelijkbare methodes kan worden gekozen als die ter beschikking zijn en bijvoorbeeld PiCCO apparatuur niet. Er zijn geen vergelijkende studies beschikbaar die het effect van het gebruiken van een PiCCO afzetten tegen het effect van hemodynamische monitoring middels een Swan Ganz, ter optimalisatie van de (neurologische) uitkomst bij SAB patiënten. De werkgroep is van mening dat vooral ervaring met de gebruikte hemodynamische monitoringtechniek binnen het behandelteam essentieel is. Verder is het van belang deze technieken alleen, zoals boven beschreven, toe te passen bij geselecteerde patiënten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Voor zowel het gebruik en de interpretatie van invasieve hemodynamische monitoring gegevens (PiCCO) als niet-gekalibreerde arteriële polsgolf analyse is het van belang dat er ervaring bestaat binnen het behandelteam. Beide technieken worden enkel op de Intensive Care en operatiekamers gebruikt en de werkgroep adviseert dan ook alleen in deze setting hiervan gebruik te maken. In de meeste SAB behandelcentra zijn dergelijke technieken aanwezig, maar worden deze ogenschijnlijk beperkt ingezet bij deze patiëntencategorie, mogelijk door onvoldoende realisatie van het belang van het voorkomen van niet alleen hypo- maar vooral ook hypervolemie. De werkgroep is van mening dat de huidige bewijskracht voor invasieve hemodynamische monitoring dusdanig sterk is dat gebruik overwogen dient te worden bij geselecteerde SAB patiënten op de Intensive Care en patiënten waarbij een verhoogd risico bestaat op complicaties door volumetherapie, overmatige diurese of verminderde cardiale functie of vermoeden daarop.

Praktische toepassing

In verband met de verhoogde neiging tot diurese (onder andere in het kader van ‘cerebral salt wasting’ syndroom) bij veel patiënten na een aneurysmatisch SAB, wordt aanbevolen te starten met een totale vochtintake van 3L bij opname om hypovolemie vroeg in het beloop te kunnen ondervangen. Echter, na de eerste dag kan beter worden gevaren op gemiddeld neutrale vochtbalansen in het streven naar normovolemie. Hierbij dient rekening te worden gehouden met variaties per dag: een vochtbalans op een dag waarop de patiënt is geopereerd kan bijvoorbeeld inclusief de vochttoediening op de operatiekamer, fors positief uitvallen, en het is dan als fysiologisch te beschouwen dat de patiënt na de operatie het teveel aan toegediend vocht weer gaat uitplassen en de dag na de operatie een negatieve vochtbalans behaalt. Juist als de fysiologisch verhoogde diurese agressief gaat worden gecompenseerd door verhoogde vochttoediening, kan sprake zijn van ‘overcompensatie’ met als gevolg overvulling, wat onwenselijk is, getuige de bestaande evidentie. In zo’n situatie is een operatiedag met vochtbalans +2 L, gevolgd door twee dagen met vochtbalans -500 ml dus niet als problematisch te beschouwen. Hierna dient dan weer naar neutrale vochtbalansen te worden gestreefd en dit wordt bedoeld met ‘over meerdere dagen gemiddeld een neutrale vochtbalans, rekening houdend met variaties per dag’, zoals verwoord in de aanbevelingen. In het verlengde hiervan dient na overname van een patiënt van de IC naar de verpleegafdeling rekening te worden gehouden met de totale vochtbalans tijdens de IC opname. Indien deze (sterk) positief is, dan is een negatieve vochtbalans in de dagen na opname op de afdeling niet per se problematisch en eerder fysiologisch. Bedenk hierbij ook dat beademing leidt tot forse vochtretentie ten gevolge van de positieve druk in de longen en de verminderde terugstroom naar het hart van veneus bloed (veneuze stuwing). Dit is de reden dat veel patiënten tijdens beademing ‘opzwellen’. Na verwijderen van de beademing zal de vochtretentie die zo is opgebouwd door het lichaam (en de nier in het bijzonder) weer worden uitgeplast.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De voordelen (gunstige effecten op relevante uitkomsten) lijken op te wegen tegen eventuele nadelen van hemodynamische monitoring. Hierbij speelt mee dat de monitoring waar de meeste evidentie voor is (transpulmonale thermodilutie, bijvoorbeeld middels PiCCO) een veelgebruikte manier van hemodynamische monitoring betreft in de dagelijkse praktijk op veel Intensive Care afdelingen.

De aanbevelingen hebben als invalshoek dat bepaalde zaken op basis van de aanwezige evidentie beter voorkómen dienen te worden. Ongewenst zijn: 1) actieve vochtbeperking met als gevolg ondervulling (hypovolemie); 2) onnodig (dat wil zeggen zonder duidelijke klinische indicatie) vocht toedienen, wat op basis van bestaande literatuur eerder schadelijk dan onschadelijk lijkt te zijn; 3) aangezien vochtbalansen een onnauwkeurige representatie kunnen zijn voor volume status (normovolemie), dient hemodynamische monitoring middels invasieve technieken te worden overwogen. De aanbevelingen hebben ten doel deze uitgangspunten te operationaliseren voor de praktijk.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Normovolemie, ofwel de juiste hoeveelheid bloed en vocht in de bloedvaten om de bloeddoorstroming en zuurstofvoorziening van alle vitale organen inclusief de hersenen te garanderen, is een van de peilers van het standaardbeleid bij patiënten met een aneurysmatische SAB. Echter, lange tijd zijn ook ‘hypervolemie’ en verdunning van het bloed middels infuusvloeistoffen ter verlaging van de viscositeit van bloed, voor zowel preventieve als curatieve behandeling voor cerebrale vaatspasmen/delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI), in zwang geweest met het idee dat daarmee de doorbloeding van de hersenen ondanks vaatspasmen zou kunnen verbeteren. Samen met bloeddrukverhoging (geïnduceerde hypertensie) wordt dit beleid ‘Triple-H’ (hypervolemie, hemodilutie, hypertensie) therapie genoemd. Echter, de laatste jaren wordt meer duidelijk dat zowel hypovolemie (intravasculaire ondervulling) als hypervolemie (de definitie hiervan betreft eigenlijk zodanige vochttoediening dat vocht uittreedt uit de vaten met als gevolg oedeem en/of veneuze stuwing) schadelijk kunnen zijn. Evenmin zijn er kwalitatief goede studies gedaan naar de effecten van triple-H op neurologische uitkomsten. Daarnaast zijn er aanwijzingen dat het optimaliseren van de ‘volumestatus’, zoals de intravasculaire vullingsstatus vaak wordt genoemd, middels invasieve vormen van monitoring (waaronder het hartminuutvolume, of ‘cardiac output’) gunstige effecten kan hebben op neurologische uitkomsten waarbij met name opvalt dat bij nauwkeurigere monitoring de hoeveelheid vochttoediening kan worden beperkt. Deze bevindingen suggereren samen met meerdere observationele studies, dat er een neiging bestaat bij veel behandelaren om te veel vocht aan de patiënten toe te dienen en dat dit een negatieve invloed kan hebben op klinische uitkomsten. De interpretatie en implementatie van deze kennis ten aanzien van optimalisatie van volumestatus lijkt nog wisselend te zijn. Mogelijk wordt hypervolemie (ook als strategie om in elk geval hypovolemie te kunnen voorkómen) nog steeds beschouwd als therapeutisch, terwijl hypervolemie waarschijnlijk: 1) schadelijk is en 2) mogelijk te voorkómen is, mits bewustwording daarover toeneemt.

Anderzijds hebben SAB patiënten vaak de neiging overmatige diurese te vertonen, welke, zeker in combinatie met hyponatriëmie, een verhoogd risico inhoudt voor het ontwikkelen van DCI. Diverse studies hebben laten zien dat hyponatriëmie en overmatige diurese kunnen afnemen na toediening van mineralocorticoïden (hydrocortison of fludrocortison) en op die wijze gunstige effecten kunnen hebben. Of echter een duidelijk effect op uitkomsten bestaat is onzeker.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

2.1 Hemodynamic monitoring

|

Low GRADE |

Circulatory management guided by PiCCO may prevent delayed cerebral ischemia compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Sources: (Anetsberger, 2020; Simonassi, 2020: Mutoh, 2009; Mutoh, 2014) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether circulatory management guided by uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis monitoring prevents delayed cerebral ischemia compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Sources: (Chui, 2020) |

|

Low GRADE |

Circulatory management guided by PiCCO may improve neurological outcome compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Sources: (Anetsberger, 2020; Simonassi, 2020: Mutoh, 2009; Mutoh, 2014) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether circulatory management guided by uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis monitoring affects neurological outcome compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Sources: (Chui, 2020) |

|

Low GRADE |

Circulatory management guided by PiCCO may reduce mortality compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Sources: (Anetsberger, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether circulatory management guided by uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis monitoring reduces mortality compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Chui, 2020) |

|

Low GRADE |

Circulatory management guided by PiCCO may reduce hospital length of stay compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Sources: (Anetsberger, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether circulatory management guided by uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis monitoring reduces hospital length of stay compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Chui, 2020) |

|

Low GRADE |

Circulatory management guided by PiCCO may prevent pulmonary edema compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Sources: (Anetsberger, 2020; Simonassi, 2020: Mutoh, 2009; Mutoh, 2014) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether circulatory management guided by uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis monitoring prevents pulmonary edema compared to standard monitoring in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Chui, 2020) |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome quality of life, due to the absence of data. |

2.2 Hypervolemia and hemodilution

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether hypervolemia affects delayed cerebral ischemia compared to non-hypervolemia in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Lennihan, 2000; Egge, 2001; Togashi, 2015) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether hypervolemia affects neurological outcome compared to non-hypervolemia in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Lennihan, 2000; Egge, 2001; Togashi, 2015) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether hypervolemia affects cardiopulmonary complications compared to non-hypervolemia in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Lennihan, 2000; Egge, 2001; Togashi, 2015) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether hypervolemia affects complications in general compared to non-hypervolemia in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: hypervolemia might be associated with higher risk of complications in general.

Sources: (Lennihan, 2000; Egge, 2001; Togashi, 2015) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether hypervolemia affects mortality compared to non-hypervolemia in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Lennihan, 2000; Egge, 2001; Togashi, 2015) |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome hospital length of stay, due to the absence of data. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome quality of life, due to the absence of data. |

2.3 Fluid composition

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for fluid composition and the outcome delayed cerebral ischemia, due to the absence of data. |

|

Low GRADE |

Euvolemic treatment with hydroxyethyl starch solution may not affect neurological outcome compared to treatment with Ringer’s lactate solution in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Gál, 2020) |

|

Low GRADE |

Euvolemic treatment with hydroxyethyl starch solution may not affect mortality compared to treatment with Ringer’s lactate solution in patients with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sources: (Gál, 2020) |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome cardiopulmonary events, due to the absence of data. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome hospital length of stay, due to the absence of data. |

|

- GRADE |

It was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence for the outcome quality of life, due to the absence of data. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The included studies compared different types of interventions. Below, they are outlined per intervention type.

1.1 Hemodynamic monitoring

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Simonassi (2020) aimed to assess whether a clinical strategy guided by advanced versus standard hemodynamic monitoring can reduce systemic and cerebral complications, as well as improving patient outcomes after aneurysmal SAH. Three RCTs (Hoff, 2009; Mutoh, 2009; Mutoh, 2014) with in total 362 patients were included in the meta-analysis, in which delayed cerebral ischemia, neurological outcome and pulmonary edema were reported. The systematic review had a low risk of bias, but considered the level of evidence very low, due to the inherent limitations, heterogeneous monitoring techniques, imprecision, and risk of bias in all included studies. Of note, the study of Hoff (2009) was excluded from the current analysis, because it was not considered a RCT.

Two additional studies investigated advanced monitoring. Chui (2020) performed a pilot RCT to determine the feasibility and efficacy of a goal-directed therapy algorithm during coiling of a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Forty adult patients who presented with WFNS grade I to IV aneurysmal SAH and who were scheduled for an endovascular aneurysm coiling procedure within 5 days of aneurysm rupture were randomized to receive either goal-directed therapy or standard care. The study intervention was intraoperative hemodynamic optimization using a noninvasive cardiac output monitoring (NICOM) device (FloTrac Edwards EV1000, Edwards Lifesciences, Canada) connected via an arterial catheter (by means of uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis). For patients in the intervention group, the attending anesthesiologist used the information obtained from the NICOM to manage fluid balance and hemodynamics during the coiling procedure according to a predefined treatment algorithm. This American study with a follow-up of 3 months reported symptomatic vasospasm, ischemic stroke, neurological outcome, hospital length of stay and specific cardiopulmonary events, including pulmonary edema. Risk of bias was high for outcomes without objective end points, because physicians, nurses, and investigators could not be blinded for the treatment. Furthermore, since this pilot study was designed to investigate the feasibility of GDT during endovascular treatment in aneurysmal SAH patients, it was not powered to demonstrate a reduction in vasospasm with GDT.

The RCT by Anetsberger (2020) compared advanced hemodynamic monitoring including transpulmonary thermodilution to direct the volume therapy with standard clinical care. In both groups, the treatment goals included enteral nimodipine, normothermia, avoidance of hypo- or hyperglycemia, electrolyte balance, and adequate ventilation. Adult patients with an aneurysmal SAH diagnosed by CT and confirmed by angiography were randomized to the intervention or control group (both N=54). This German study with a follow-up of 3 months reported DCI, neurological outcome, mortality, hospital length of stay and specific cardiopulmonary events, including pulmonary edema. Risk of bias was high for outcomes without objective end points, because physicians, nurses, and investigators could not be blinded for the treatment.

Table 1. Study characteristics for RCTs about hemodynamic monitoring

|

Study |

Population |

Intervention |

N |

Country |

Follow-up |

|

Mutoh, 2009* |

Aneurysmal SAH patients treated with clipping |

Transpulmonary thermodilution-based hemodynamic monitoring (PiCCO) Duration: 14 days. |

100 |

Japan |

3 months |

|

Mutoh, 2014* |

Aneurysmal SAH patients treated with clipping or coiling |

Transpulmonary thermodilution-based hemodynamic monitoring (PiCCO) Duration: 14 days. |

160 |

Japan |

3 months |

|

Chui, 2020 |

Adult aneurysmal SAH patients treated with coiling |

Hemodynamic optimization using a noninvasive cardiac output monitoring device (FloTrac) Duration: only during coiling. |

40 |

USA |

3 months |

|

Anetsberger, 2020 |

Adult aneurysmal SAH patients treated with clipping or coiling |

Advanced hemodynamic monitoring including transpulmonary thermodilution (PiCCO2) Duration: 14 days or until discharge. |

108 |

Germany |

3 months |

*reported in the meta-analysis by Simonassi, 2020; PiCCO: Pulse index Continuous Cardiac Output

1.2. Hypervolemia (and hemodilution)

Loan (2018) performed a systematic review to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to guide practice in use of medically induced hypertension, hypervolemia and hemodilution (HHH) for the treatment and prophylaxis of vasospasm following aneurysmal SAH. RCTs and cohort studies in adult patients with radiographic or biochemical evidence of SAH, comparing HHH or an element of HHH with any alternative management strategy were included. The authors identified 4 RCTs and 4 observational studies, but stated that it was not possible to attempt meaningful meta-analysis due to the methodological heterogeneity between the studies. In the current analysis, only RCTs were considered. The studies by Lennihan (2000), Egge (2001) and Togashi (2015) were included. The main study characteristics are outlined in figure 2, mainly patients after clipping were included. The intervention in the RCT by Gathier (2015) reported in the systematic review was induced hypertension. As this is analysed in module 15, cerebral ischemia, that study was not included in the present analysis. If possible, data reported by Loan (2018) were used. Outcomes not reported in the systematic review were retrieved from the original papers.

Table 2 Study characteristics for RCTs about hemodilution and hypervolemia (may be reported as part of HHH)

|

Study |

Population |

Intervention |

N |

Setting, country |

Follow-up |

|

Egge, 2001 |

Patients with confirmed aneurysmal SAH who underwent surgical clipping < 3 days post-ictus. |

Prophylactic HHH (12 days). Randomization after clipping. |

32 |

ICU, Norway |

12 months |

|

Lennihan, 2000 |

Patients with aneurysmal SAH who underwent surgical clipping <6 days post-ictus |

Prophylactic hypervolemic fluid management (14 days). Randomization after clipping. |

82 |

NeuroICU, USA |

12 months |

|

Togashi, 2015 |

Patients with angiographically proven aneurysmal SAH, who underwent clipping or coiling <72 h post-ictus |

2x2 factorial design, hyper- versus normovolemia and conventional versus augmented blood pressure (10 days or until ICU discharge) Randomization after coiling/clipping. |

20 |

NeuroICU, USA |

6 months |

HHH: induced hypertension, hypervolaemia and haemodilution; neuroICU: specialist neurointensive care unit

1.3. Fluid composition

The RCT by Gál (2020) compared the effect of two prophylactic euvolemic fluid strategy regimens on the incidence of cerebral vasospasm and clinical outcomes in patients with SAH. Patients diagnosed with aneurysmal SAH based on clinical findings and CT followed by cerebral angiography, presenting at the Neurosurgical ICU between February 2014 and March 2015 were included. All patients received nimodipine (6x60 mg) and 40 mg/day simvastatin orally. A basic fluid intake of 15 mL/kg/day Ringer’s lactate solution was administered intravenously in all patients. To reach the target MAP values, an additional amount of 15 to 50 mL/kg/day Ringer’s lactate (control group) or hydroxyethyl starch (HES) 130/0.4 solution (intervention group) was administered intravenously. Relevant outcomes reported by the RCT were (un)favourable neurological outcome and mortality. The study had a low risk of bias.

Results

2.1 Hemodynamic monitoring

Delayed cerebral ischemia (critical)

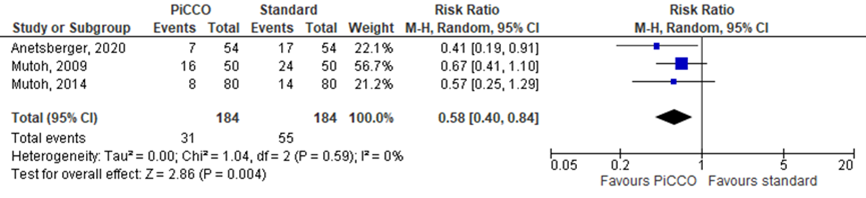

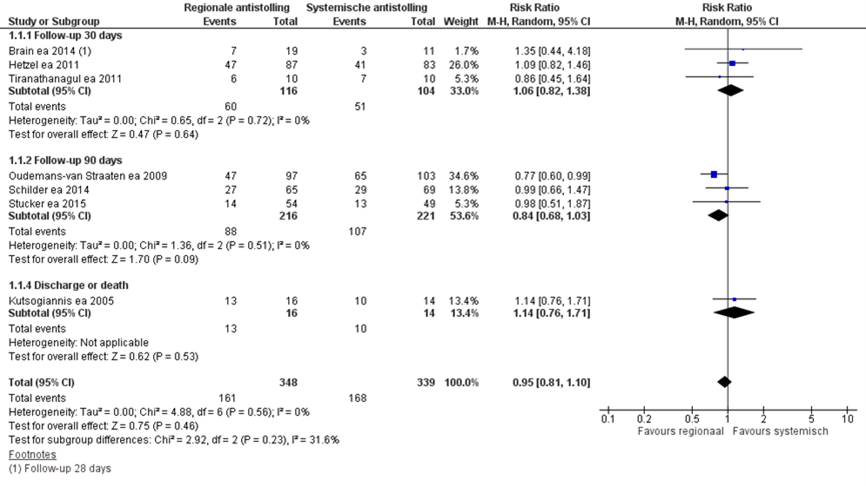

Three studies compared PiCCO advanced monitoring with standard monitoring and reported delayed cerebral ischemia, as presented in figure 14.1.3 With 31 events in 184 patients (17%) after PiCCO monitoring versus 55 events in 184 patients (30%) after standard monitoring, the pooled relative risk (RR) was 0.58, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from 0.40 to 0.84 in favour of PiCCO monitoring, a clinically relevant and statistically significant difference. One study compared uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis (using a FloTrac transducer) with standard monitoring during coiling procedures. The study by Chui (2020) reported ischemic stroke and found 3/21 events in the group monitored with FloTrac versus 1/19 in the group with standard monitoring. The difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 3 Delayed cerebral ischemia in SAH patients with PiCCO versus standard monitoring

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Neurological outcome (critical)

Clinical or neurological outcome, as determined by mRS of GOS, was reported in 4 studies. As presented in figure 14.1.4, 60 out of 183 patients (33%) reported poor outcome after PiCCO monitoring, as opposed to 94 out of 184 patients (51%) after standard monitoring, resulting in a RR of 0.73 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.92). This was a clinically relevant and statistically significant difference in favour of PiCCO monitoring. No statistically significant or clinically relevant differences were found between uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis and standard monitoring.

Figure 4 Neurological outcome at 3 months in SAH patients with PiCCO versus standard monitoring

Events indicate poor neurological outcome, defined as mRS > 3, unless indicated otherwise. Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Mortality

The systematic review by Simonassi (2020) did not report mortality. Anetsberger (2020) reported mortality at 3 months. In the PiCCO monitoring group, mortality was 9% (5/54), versus 17% (9/54) in the standard monitoring group. This difference (RR 0.56; 95% CI 0.20 to 1.55; N=108) was considered clinically relevant but not statistically significant (P=0.267).

Length of stay

The systematic review by Simonassi (2020) did not report length of stay. Two studies reported hospital length of stay. Anetsberger (2020) found a median of 22 days for PiCCO monitoring (N=54), with an interquartile range (IQR) from 18 to 31, versus 24 days (IQR 17 to 32) in the standard monitoring group (N=54). Chui (2020) reported a hospital length of stay of 23±18 days with uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis monitoring (N=21) versus 21±24 days with standard monitoring (N=19). These differences were considered clinically relevant but not statistically significant (P=0.946 and P=0.696, respectively).

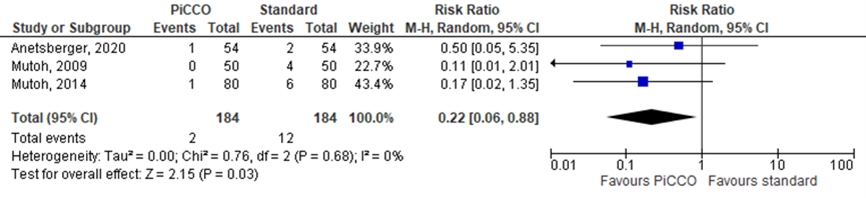

Cardiopulmonary events

Cardiopulmonary events were reported in all included studies. Due to the different cardiovascular and pulmonary events reported in the studies, a general risk ratio could not be determined. However, pulmonary edema was reported in 4 studies. Taken together from 3 studies, the RR was 0.22 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.88) in favour of PiCCO monitoring (figure 14.1.5), with 2 events in 184 patients (1%) in the PiCCO monitoring group versus 12 events in184 patients in the standard monitoring group (7%), as presented in figure 3. The difference was considered clinically relevant and statistically significant. Comparing uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis with standard monitoring, Chui (2020) reported no events in both groups.

Figure 5 Pulmonary edema in SAH patients with PiCCO versus standard monitoring

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Quality of life

The outcome quality of life was not reported in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials. For the comparison between PiCCO and standard monitoring, the level of evidence for the outcomes “DCI”, “neurological outcome”, “mortality”, “hospital length of stay ”, and “cardiopulmonary events” was downgraded by two levels to low because of the limited study population size and the fact that the confidence intervals crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (both imprecision).

For the comparison between uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis and standard monitoring, the level of evidence for all outcomes was downgraded to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, pilot study), limited study population size and the fact that the confidence intervals crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (both imprecision).

The level of evidence for the outcome “quality of life” could not be determined due to a lack of data.

2.2 Hypervolemia and hemodilution

Results for the different outcomes are described below. Due to heterogeneity in the study interventions, results could not be pooled.

Delayed cerebral ischemia (critical)

Three RCTs reported symptomatic vasospasm and/or DCI. Lennihan (2000) reported an occurrence of symptomatic vasospasm in 8 out of 41 cases (20%), both in the hypervolemic fluid management and in the control group (both N=41). In that study, 7 patients (17%) had a cerebral infarction with hypervolemic treatment versus 4 patients (10%) with normovolemic treatment. Egge (2001) reported 4/16 patients (25%) with symptomatic vasospasm in the HHH group, versus 5/16 patients (31%) in the control group. When comparing hypervolemia and normovolemia, Togashi (2015) found 1 case of DCI in 10 patients (10%) versus 0/10 (0%), respectively. Induced hypertension is analysed in module 15.2)

Neurological outcome (critical)

Two studies reported poor neurological/clinical outcome, defined as GOS≤4. Lennihan (2000) reported poor outcome at 3 months in 10/40 patients (25%) treated with hypervolemia versus 10/39 patients (26%) treated with normovolemia. The differences were not significant. Egge (2001) reported 7/16 patients (44%) with poor outcome at 12 months after HHH therapy versus 4/16 (25%) in the control group. Statistical analysis was not reported for this outcome.

Togashi (2015) did not report poor outcome, but reported a mean ± SD mRS at 6 months: hypervolemia 1.6 ± 1.84 (N=10) versus normovolemia 1.7 ± 0.67 (N=10; P = 0.87).

Mortality

Mortality was reported in 3 RCTs. Mortality at 3 months was 2/41 (5%) in patients with induced hypervolemia versus 3/41 (7%) in the normovolemic group in the study by Lennihan (2000). Egge (2001) found 1/16 (6%) mortality at 1 year both in the HHH group and in the control group. Togashi reported a 6-month mortality of 1/10 (10%) for hypervolemic treatment verus 0/10 (0%) for normovolemic treatment. Statistical analysis was not reported.

Length of stay

The outcome “hospital length of stay” was not reported in the included studies.

Cardiopulmonary events

Three studies reported cardiopulmonary events. Lennihan (2000) reported congestive heart failure in 1/41 patients (3%) in the hypervolemic group versus 0/41 (0%) in the control group (P=N.S.). Egge (2001) reported congestive heart failure combined with arrhythmia and pulmonary edema in 2/16 patients (12.5%) in the HHH group, versus 0/16 (0%) in the control group. Togashi (2015) reported serious adverse events. Myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure and arrhythmia did not occur in any treatment group. Pulmonary edema was reported in 2/10 patients (20%) treated with hypervolemia versus 1/10 (10%) in the normovolemia group. No statistical analysis was described.

Complications

Three studies reported complications. Complications occurred similarly frequently between groups (Lennihan, 2000). Egge (2001) reported complications including extradural hematomas, hemorrhagic diathesis and infections. The frequency of all complications combined, including haemorrhagic diathesis and congestive cardiac failure, was significantly higher in the HHH group (P < 0.001) (Egge, 2001). A non-significant trend towards increased serious adverse events in the hypervolaemic groups was demonstrated (risk ratio 4.0; 95% confidence interval 0.5–29.8; p=0 .12) in the study of Togashi (2015).

Quality of life

The outcome “quality of life” was not reported in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcomes “delayed cerebral ischemia”, “neurological outcome”, “mortality”, “cardiopulmonary events” and “complications" started at high as it was based on randomized controlled trials. For all these outcomes, the level of evidence was downgraded to very low because of clinical heterogeneity in the interventions, the limited study population size and the fact that the confidence intervals crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (both imprecision).

The level of evidence for the outcomes “hospital length of stay” and “quality of life” could not be determined due to a lack of data.

2.3 Fluid composition

Delayed cerebral ischemia (critical)

Delayed cerebral ischemia was not reported in the included study.

Neurological outcome (critical)

Gál (2020) reported unfavourable outcome, defined as GOS 1-3, at 30 days and found 14/48 patients (29%) in the Hydroxy-Ethyl Starch (HES) group versus 9/48 patients (19%) in the Ringer’s lactate solution group. The RR was 1.56 (95% CI 0.75 to 3.25) for an unfavourable outcome after treatment with HES. The differences were not statistically significant (Chi-square 1.43).

Mortality

Mortality at 30 days was 2/48 (4%) both for patients treated with HES and patients treated with Ringer’s lactate solution in the RCT by Gál (2020).

Other outcomes

The outcomes “hospital length of stay”, “cardiopulmonary events” and “quality of life” were not reported in the included study.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcomes “neurological outcome” and “mortality” started at high as it was based on a randomized controlled trial. For these outcomes, the level of evidence was downgraded to low because of the limited study population size and the fact that the confidence intervals crossed the limit of clinical decision-making (both imprecision).

The level of evidence for the outcomes “delayed cerebral ischemia”, “hospital length of stay”, “cardiopulmonary events”, and “quality of life” could not be determined due to a lack of data.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favourable effects of treatment aimed at fluid management, monitoring of volume status/circulation/cardiac output or fluid composition compared to usual care in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)

P:patients patients with an aneurysmal SAH;

I: intervention interventions targeting volume status, type of fluid therapy or hemodynamic monitoring;

C: control usual care;

O: outcome delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI), neurological/clinical outcome, mortality, hospital length of stay, cardiopulmonary complications, quality of life.

Relevant outcomes

The guideline development group considered delayed cerebral ischemia and neurological/clinical outcome to be critical outcomes for decision-making; and mortality, hospital length of stay, cardiopulmonary complications, and quality of life to be important outcomes for decision-making.

For neurological/clinical outcome, the guideline development group followed the definitions of favourable or poor outcome as reported in literature, expressed with the modified Rankin scale (mRS, score from 0: perfect health to 6: death) and Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS, score from 1: death to 5: good recovery). For the other outcomes, the guideline development group followed the definitions used in the studies.

The guideline development group defined 5% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for mortality, the standard GRADE limit of 25% for other dichotomous outcomes, 10% of the maximum score for outcome scores and quality of life scores, and 1 day for hospital length of stay.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until September 22, 2020. The detailed search strategy is outlined under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 206 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: (systematic reviews of) randomized controlled trials in patients with a SAH, comparing an intervention or interventions based on the volume, composition and/or monitoring of administered fluid with usual care, in which patient-relevant outcomes were reported. Based on title and abstract screening, 15 studies were initially selected. After reading the full text, 10 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 5 studies were included.

Results

Two systematic reviews and three RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- 10 - Anetsberger A, Gempt J, Blobner M, Ringel F, Bogdanski R, Heim M, Schneider G, Meyer B, Schmid S, Ryang YM, Wostrack M, Schneider J, Martin J, Ehrhardt M, Jungwirth B. Impact of Goal-Directed Therapy on Delayed Ischemia After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke. 2020 Aug;51(8):2287-2296. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029279. Epub 2020 Jul 9. Erratum in: Stroke. 2020 Sep;51(9):e272. PMID: 32640940.

- 20 - Chui J, Craen R, Dy-Valdez C, Alamri R, Boulton M, Pandey S, Herrick I. Early Goal-directed Therapy During Endovascular Coiling Procedures Following Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Pilot Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2020 Jun 2. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000700. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32496448.

- 30 - Connolly ES, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, Derdeyn CP, Dion J, Higashida RT, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart

- 40 - Diringer MN, Bleck TP, Hemphill JC, Menon D, Shutter L, Vespa P, et al. Critical care management of patients following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Recommendations from the neurocritical care society’s multidisciplinary consensus conference. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15(2):211–40.

- 50 - Gál J, Fülesdi B, Varga D, Fodor B, Varga E, Siró P, Bereczki D, Szabó S, Molnár C. Assessment of two prophylactic fluid strategies in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A randomized trial. J Int Med Res. 2020 Jul;48(7):300060520927526. doi: 10.1177/0300060520927526. PMID: 32689849; PMCID: PMC7375726.

- 60 - Hoff RG, Rinkel GJE, Verweij BH, Algra A, Kalkman CJ. Nurses’ prediction of volume status after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: A prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2008;12(6):1–5.

- 70 - Egge A, Waterloo K, Sjøholm H, Solberg T, Ingebrigtsen T, Romner B. Prophylactic hyperdynamic postoperative fluid therapy after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a clinical, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Neurosurgery. 2001 Sep;49(3):593-605; discussion 605-6. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200109000-00012. PMID: 11523669.

- 80 - Lennihan L, Mayer SA, Fink ME, Beckford A, Paik MC, Zhang H, Wu YC, Klebanoff LM, Raps EC, Solomon RA. Effect of hypervolemic therapy on cerebral blood flow after subarachnoid hemorrhage : a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2000 Feb;31(2):383-91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.2.383. PMID: 10657410.

- 90 - Le Roux P, Menon DK, Citerio G, Vespa P, Bader MK, Brophy G, et al. Consensus summary statement of the International Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference on Multimodality Monitoring in Neurocritical Care: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and the European Society of Intensive Car. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(9):1189–209.

- 100 - Loan JJM, Wiggins AN, Brennan PM. Medically induced hypertension, hypervolaemia and haemodilution for the treatment and prophylaxis of vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: systematic review. Br J Neurosurg. 2018 Apr;32(2):157-164. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2018.1426720. Epub 2018 Jan 17. PMID: 29338431.

- 110 - Macdonald RL, Kassell NF, Mayer S, Ruefenacht D, Schmiedek P, Weidauer S, Frey A, Roux S, Pasqualin A; CONSCIOUS-1 Investigators. Clazosentan to overcome neurological ischemia and infarction occurring after subarachnoid hemorrhage (CONSCIOUS-1): randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 dose-finding trial. Stroke. 2008 Nov;39(11):3015-21.

- 120 - Rass V, Gaasch M, Kofler M, Schiefecker AJ, Ianosi B, Steinkohl F et al. Fluid intake but not fluid balance is associated with poor outcome in nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. Crit Care Med. 2019:47(7):e555-e562

- 130 - Simonassi F, Ball L, Badenes R, Millone M, Citerio G, Zona G, Pelosi P, Robba C. Hemodynamic Monitoring in Patients With Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2020 Jan 31. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000679. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32011413.

- 140 - Slagt C, Malagon I, Groeneveld AB. Systematic review of uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis to determine cardiac output and stroke volume variation. Br J Anaesth. 2014 Apr;112(4):626-37.

- 150 - Tagami T, Kuwamoto K, Watanabe A, Unemoto K, Yokobori S, Matsumoto G, et al. Optimal range of global end-diastolic volume for fluid management after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(6):1348–56.

- 160 - Togashi K, Joffe AM, Sekhar L, Kim L, Lam A, Yanez D, Broeckel-Elrod JA, Moore A, Deem S, Khandelwal N, Souter MJ, Treggiari MM. Randomized pilot trial of intensive management of blood pressure or volume expansion in subarachnoid hemorrhage (IMPROVES). Neurosurgery. 2015 Feb;76(2):125-34; discussion 134-5; quiz 135. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000592. PMID: 25549192.

- 170 - Van der Jagt M, Fluid Management of the neurological patient: a concise review. Crit Care. 2016; 20(1):126.

- 180 - Vergouw LJM, Egal M, Bergmans B, Dippel DWJ, Lingsma HF, Vergouwen MDI et al. High early fluid input after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: combined report of association with delaed cerebral ischema and feasibility of cardiac output-guided fluid restriction. J Intensive Care Med. 2020:35(2);161-169.

- 190 - Vinciguerra L, Bösel J. Noninvasive Neuromonitoring: Current Utility in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, Traumatic Brain Injury, and Stroke. Neurocrit Care. 2017 Aug;27(1):122-140.

- 200 - Yoneda H, Nakamura T, Shirao S, Tanaka N, Ishihara H, Suehiro E, et al. Multicenter prospective cohort study on volume management after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Hemodynamic changes according to severity of subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral vasospasm. Stroke. 2013;44(8):2155–61

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What are the (un)favourable effects of treatment based on fluid volume, monitoring or composition compared to usual care in patients with a ruptured SAH

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Loan, 2018 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes. Reasons for exclusion are indicated, but not with references |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

No. Therefore, a meta-analysis was not performed. |

Yes |

Unclear. Not specified for included studies. |

|

Simonassi, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes. Reasons for exclusion are indicated, but not with references |

No |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear. Not specified for included studies. |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: What are the (un)favourable effects of treatment based on fluid volume, monitoring or composition compared to usual care in patients with a ruptured SAH

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome accessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Anetsberger, 2020 |

Patients were randomized using a computer-generated list into either the GDHT group or the control group. |

Unlikely |

unlikely |

Likely for outcomes without objective end points.

Physicians and nurses were aware of the group assignment. |

Likely for outcomes without objective end points |

unlikely

|

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Chui, 2020 |

The randomization sequence was generated by an independent statistician using block randomization with a variable block size of 4 to 6. The allocation was placed in sealed opaque envelopes and stored in a locker. The allocation was only disclosed by the research assistant after the participant was transferred into the neuroangiography suite. |

Unlikely.

Allocation concealment was not possible during the intervention, but it is unlikely that this affected study outcomes. |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Gál, 2020

|

We used permuted block randomization. We labeled 48 cards with R and another 48 cards with V, and then we mixed them and put them into opaque envelopes. Four-item blocks were generated based on a random number generator followed by permuted block generation for all possible variations. During inclusion, the next labeled card among the arranged blocks was selected. |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Dankbaar, 2010 |

No comparison between interventions |

|

Joffe, 2015 |

No patiënt-relevant oucomes reported |

|

Kunze, 2016 |

Observational study |

|

Lehmann, 2013 |

No patiënt-relevant oucomes reported |

|

Mutoh, 2014 |

Described in SR |

|

Rabinstein, 2011 |

No meta-analysis |

|

Suarez, 2012 |

Observational study |

|

Suarez, 2014 |

Observational study |

|

Togashi, 2015 |

Described in SR |

|

Wolf, 2011 |

No systematic search performed |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-10-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 02-08-2022

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werk- en klankbordgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met (verdenking op) subarachnoïdale bloeding.

Werkgroep

- Dr. M.D.I. Vergouwen, neuroloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, voorzitter (NVN)

- Drs. J. Manuputty, neuroloog, Elisabeth-Twee Steden Ziekenhuis, Tilburg (NVN)

- Prof. dr. G.J.E Rinkel, neuroloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (NVN)

- Dr. I.R. van den Wijngaard, neuroloog, Haaglanden MC, Den Haag (NVN)

- Dr. H.D. Boogaarts, neurochirurg, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen (NVvN)

- Prof. dr. J.M.C. van Dijk, neurochirurg, UMCG, Groningen (NVvN)

- Dr. R. van den Berg, radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam (NVvR)

- Dr. G.J. Lycklama à Nijheholt, radioloog, Haaglanden MC, Den Haag (NVvR)

- Dr. W.J.M. Schellekens, anesthesioloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (tot okt 2020) (NVA)

- Dr. A. Akkermans, anesthesioloog, Fellow Intensive Care, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (vanaf okt 2020) (NVA)

- Dr. M. van der Werf, revalidatiearts, Rijndam revalidatie, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam (VRA)

- Dr. M. van der Jagt, neuroloog-intensivist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam (NVIC)

- J. Hennipman-Bikker, verpleegkundige, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (tot sep 2021) (V&VN)

- J.C. Toerse, MSc, verpleegkundig specialist, Isala, Zwolle (vanaf nov 2021) (V&VN)

Klankbord

- Carola Deurwaarder, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Hersenaneurysma Patiënten Platform

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. M. Molag, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. A. Balemans, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Achternaam werkgroeplid |

Hoofdfunctie |

Neven werkzaamheden |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie |

Overige belangen |

Actie |

|

* Vergouwen |

Neuroloog UMC Utrecht, afdeling Neurologie en Neurochirurgie |

Geen |

Vergoedingen aan UMC Utrecht van: - NeuroScios (ivm reviewer van klinische data ihkv NicaPlant studie (Phase llb : randomized, - CSL Behring voor een eenmalige advisory board meeting over een eventueel nieuw onderzoek. |

Mijn wetenschappelijk onderzoek wordt gefinancieerd door de Hartstichting, Hersenstichting, ZonMw, Vrienden UMC Utrecht, Dr Rolf Schwiete stichting.

Hoofd-onderzoeker van een fase II onderzoek naar de veiligheid en werkzaamheid van eculizumab bij patienten met een subarachnoidale bloeding, mede-gefinancierd door de producent van het middel, Alexion Pharma |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen: eculizumab zal niet worden behandeld in de richtlijn |

|

Van der Werf |

Revalidatiearts bij Rijndam locatie Erasmus MC |

Werkgroep WHR, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van den Berg |

Interventie neuro-radioloog |

Consultant bij Cerenovus neurovascular (onderdeel van Johnson & Johnson) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Lycklama à Nijeholt |

Radioloog Haaglanden MC Den Haag |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Dijk |

Afdelingshoofd Neurochirurgie UMCG |

Voorzitter Neurovasculair Expertisecentrum UMCG (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van der Jagt |

Neuroloog-intensivist |

Voorzitter commissie richtlijnontwikkeling van de NVIC (onbetaald). Commissielid van de Adviescommissie richtlijnen SKMS2 |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Manuputty |

Neuroloog ETZ (Elisabeth TweeSteden Ziekenhuis (Tilburg) |

Bestuurslid Vereniging Nederlandse Hoofdpijncentra (VNHC) tot 2021; onbetaald |

Geen |

Deelname aan studie "Determinants of physical behaviour after SAH", |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Rinkel |

Hoogleraar neurologie, UMC Utrecht, 1.0FTE |

Geen |

Geen |

Lid van de stuurgroep van ULTRA, een door de Nederlandse Hartstichting gefinancieerd fase III onderzoek naar de effectiviteit van tranexaminezuur bij patienten met een subarachoidale bloeding |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen: eculizumab zal niet worden behandeld in de richtlijn |

|

Hennipman-Bikker |

Medium Care verpleegkundige op de Medium Care Neurologie / Neurochirurgie |

Geen |

Geen persoonlijke financiele belangen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van den Wijngaard |

Vasculair neuroloog, Haaglanden MC & LUMC (40%) |

Bestuurslid Nederlands Neurovasculair Genootschap (onbetaald) Imaging committee MR Clean Studies (onbetaald) |

nvt |

nvt |

|

nvt |

Geen |

|

Schellekens |

Anesthesioloog, staflid UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

nvt |

Geen |

|

Boogaarts |

Neurochirurg, RadboudMC, Nijmegen |

Voorzitter stichting kwaliteit neurochirurgie (onkostenvergoeding). Voorzitter QRNS (Quality Registry Neurosurgery SAB (onbetaald). Voorzitter Nederlands Neurovasculair genootschap (onbetaald). |

Consultant Stryker Neurovascular (vergoeding gaat naar afdeling). Endovasculaire producten (coils, flow diverters, stroke). Advies tijdens proceduren, presentaties op congres, onderwijs |

SKMS subsidie voor ontwikkelen PROM SAB |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen penvoerder module over endovasculaire producten |

|

Akkermans |

Anesthesioloog / Fellow Intensive Care UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

|

Toerse |

Verpleegkundig specialist, Isala Zwolle, afdeling neurochirurgie |

Geen |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door afvaardiging van het Hersenaneurysma Patiënten Platform in de klankbordgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen en aanbevelingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan het Hersenaneurysma Patiënten Platform.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met subarachnoïdale bloeding. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodules (NVN, 2013) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen via een schriftelijke knelpuntanalyse. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Guideline development group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.