Termijn van behandeling van SAB

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van vroege behandeling bij SAB-patiënten met een geruptureerd aneurysma?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvragen:

- Wat is de toegevoegde waarde van ultra-vroege aneurysma behandeling (<6 uur) versus vroege (<24 uur) of intermediate (24-72 uur) of uitgestelde (>10 dagen) aneurysma behandeling?

- Wat is de toegevoegde waarde van vroege (<24 uur) behandeling versus intermediate (24-72 uur) aneurysma behandeling?

- Wat is de toegevoegde waarde van vroege behandeling (<24 uur) versus uitgestelde (>10 dagen) aneurysma behandeling bij patiënten met een matig tot slechte klinische conditie (WFNS 4-5)

Aanbeveling

Het wordt aanbevolen om patiënten met een SAB direct over te plaatsen naar een SAB behandelcentrum, ongeacht de klinische conditie bij opname.

Behandel het geruptureerde aneurysma bij SAB-patiënten met een goede klinische conditie (WFNS 1-3) binnen 72 uur na ictus en bij voorkeur binnen 24 uur in een SAB behandelcentrum.

Overweeg bij SAB-patiënten met een matige klinische conditie (WFNS 4) eveneens behandeling binnen 72 uur, al wordt dit niet door de wetenschappelijke literatuur ondersteund.

Bij SAB-patiënten met een slechte klinische conditie (WFNS 5) kan beslissing over behandeling van het aneurysma ten minste 24 uur uitgesteld worden.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de literatuur lijkt er geen betere uitkomst te zijn wanneer de behandeling binnen 24 uur werd vergeleken met behandeling binnen 24 tot 72 uur. Gezien er in de Nederlandse SAB centra een 24/7 dekking is voor de behandeling van deze pathologie is er dan ook geen reden om een behandeling uit te stellen tenzij hiervoor specifieke redenen zijn (complex aneurysma bijvoorbeeld). Voor ultra-vroege behandeling werden weinig studies gevonden: er is niets bekend over het verschil in uitkomst tussen behandeling binnen 6 uur en na 6 uur. Er is mogelijk een hogere kans op een procedurele recidief bloeding bij behandeling binnen 6 uur, echter was de bewijskracht hiervoor zeer laag. Er bestaat veel onzekerheid rondom dit resultaat.

Voor de subgroep patiënten die er neurologisch slecht aan toe zijn door de SAB (WFNS 4-5) kan niet gesteld worden dat zij baat hadden bij een vroege behandeling (binnen 24 uur). Een verbetering van de klinische conditie na initiële slechte score geeft wel een noodzaak tot behandeling om een recidief bloeding te voorkomen. In de literatuur wordt geen onderscheid wordt gemaakt tussen een WFNS 4 en 5-patiënt. De werkgroep is echter van mening dat WNFS 4 patiënten (zeker diegenen met een GCS van 10 - 12) wel degelijk baat kunnen hebben bij behandeling binnen 24 tot 72 uur.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventtueel hun verzorgers)

Voor de patiënt geldt dat er gestreefd moet worden naar de best mogelijke neurologische uitkomst na een aneurysmatische SAB. In dit kader dienen vooraleerst risicofactoren te worden geëlimineerd die de patiënt het meest bedreigen (na neurologische resuscitatie). Bij de patiënt in een goede conditie (WFNS 1-3) is de recidief bloeding het meest bedreigend; bij de patiënt in een slechte conditie (WFNS 4-5) is dit minder duidelijk. Wellicht dat neurologische stabilisatie voor die patiënten belangrijker is.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Vroege (< 24 uur) aneurysmabehandeling gaat mogelijk met extra kosten gepaard (acute logistiek) in vergelijking met behandeling binnen 24 tot 72 uur. Maar als dit leidt tot een betere klinische uitkomst, dan leidt dat uiteindelijk tot lagere kosten, zowel direct als indirect gerelateerd aan de behandeling. Echter is daarvoor op dit moment dus te weinig bewijs.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Vroege (< 24 uur) behandeling van patiënten in een goede neurologische conditie (WFNS 1-3) is door iedereen gewenst en waarschijnlijk ook voor iedereen haalbaar. Aangezien de QNRS-registratie laat zien dat de meeste geruptureerde aneurysmata nu al binnen 24 uur behandeld worden, betreft het geen grote verandering binnen de huidige praktijk.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventie

Het bewijs is erg onzeker of vroege behandeling (< 24 uur) een betere uitkomst geeft ten opzichte van behandeling binnen 24 tot 72 uur. De mening van de werkgroep is dat behandeling < 24 uur gewenst is en binnen 72 uur noodzakelijk en waarschijnlijk ook voor iedereen haalbaar. Het vertragen van de behandeling levert ook geen aangetoond voordeel maar brengt het potentiële gevaar van een recidief bloeding mee.

Het is onzeker of behandeling van het aneurysma van de patiënt in slechte klinische conditie (WFNS 4 of 5) binnen 24 uur voordelen biedt. Enerzijds kan dit de patiënt beschermen voor een mogelijke recidief bloeding, anderzijds kan dit een behandeling zijn waarbij de patiënt geen voordeel heeft vanwege de slechte klinische conditie. Hierbij moet vermeld worden dat in de literatuur geen onderscheid wordt gemaakt tussen een WFNS 4 en 5-patiënt. De werkgroep is echter van mening dat patiënten met een WFNS 4 wel baat kunnen hebben bij behandeling binnen 24 tot 72 uur.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In Nederland presenteren patiënten met een SAB zich doorgaans snel na het begin van de klachten in het ziekenhuis. Hierdoor wordt een onderliggend geruptureerd aneurysma tegenwoordig sneller gediagnosticeerd dan vroeger. Spoedige behandeling van een aneurysma is wenselijk vanwege het risico op een nieuwe bloeding. Een dergelijke recidief bloeding heeft een hoge morbiditeit en mortaliteit. Conform de SAB-richtlijn uit 2012 werd het geruptureerde aneurysma zo spoedig mogelijk en bij voorkeur binnen 24 uur behandeld. De argumenten hierbij zijn het voorkomen van een recidief bloeding vanuit het aneurysma, alsmede de mogelijkheid om cerebrale ischemie na de behandeling van het aneurysma te kunnen behandelen.

Gezien het feit dat behandeling van geruptureerde intracraniële aneurysmata een beroep doet op de relatieve schaarste van specifieke expertise met betrekking tot het afsluiten van het geruptureerd aneurysma (endovasculaire behandeling dan wel neurochirurgisch clippen), dient er een goede indicatiestelling te zijn. Dat wil zeggen dat vermeden dient te worden dat patiënten worden behandeld die daarvan geen voordeel zullen ondervinden, bijvoorbeeld patiënten die comateus zijn bij opname en dermate ernstige hersenschade hebben opgelopen als gevolg van de initiële bloeding dat herstel tot een acceptabele functionele toestand niet te verwachten valt. Anderzijds is een afwachtend beleid bij deze patiënten, van wie bekend is dat zij ondanks een initieel comateuze toestand toch kunnen verbeteren, niet zonder risico op vroege recidief bloeding. Het is in dit kader op individuele basis echter moeilijk te voorspellen welke patiënten met een initieel slechte neurologische toestand in de uren en dagen na de bloeding nog zullen herstellen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

CRUCIAL OUTCOME MEASURE: ‘POOR’ OUTCOME (mRS or GOS)

Ultra-early (< 6 hours) treatment versus early (< 24 hours)

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that compared functional outcome after ultra-early (< 6 hours) compared to early treatment (< 24 hours) of a ruptured aneurysm. |

Early treatment (< 24 hours) compared to intermediate treatment (24 to 72 hours) after SAH

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early treatment (< 24 hours) on poor outcome when compared with intermediate treatment (24 to 72 hours) after SAH.

Sources: (Rawal, 2017; Oudshoorn ISAT&UMC, 2014; Philips, 2011; Qian, 2014) |

Early (< 24 hours) treatment versus delayed (> 10 days)

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that compared functional outcome after ultra-early (< 6 hours) compared to delayed treatment (> 10 days) of a ruptured aneurysm. |

IMPORTANT OUTCOME MEASURES: PROCEDURAL REBLEEDING/ REBLEEDING/ THROMBOEMBOLIC COMPLICATIONS

Ultra-early (< 6 hours) treatment compared to intermediate (24 to 72 hours) treatment: procedural rebleeding

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ultra-early treatment (< 6 hours) on procedural rebleed when compared with treatment > 6 hours after SAH. Ultra-early treatment (within 6 hours) may be associated with a higher risk of procedural rebleeding compared to treatment after 6 hours.

Sources: (van Lieshout, 2019) |

Ultra-early (< 6 hours) treatment compared to early (< 24 hours) or intermediate (24 to 72 hours) treatment: rebleeding

|

- GRADE |

No studies compared rebleeding in patients with ultra- early aneurysm treatment (< 6 hours) versus early (< 24 hours) or intermediate (24 to 72 hours) treatment.

Sources: - |

Early treatment (< 24 hours) compared to intermediate treatment (24 to 72 hours) after SAH:

rebleeding

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early treatment (< 24 hours) on rebleeding when compared with intermediate treatment (24 to 72 hours) after SAH.

Sources: (Oudshoorn ISAT&UMC, 2014) |

Early treatment (< 24 hours) compared to intermediate treatment (24 to 72 hours) after SAH:

procedural rebleeding or thromboembolic complications

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that compared procedural rebleeding or thromboembolic complications in patients with early aneurysm treatment (< 24 hours) compared with intermediate treatment (24 to 72 hours). |

Subgroup with WFNS 4 or 5

CRUCIAL OUTCOME MEASURE: ‘POOR’ OUTCOME (mRS or GOS)

Early treatment (< 24 hours) compared to delayed treatment (> 10 days) after SAH:

poor outcome

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that compared poor outcome in patients with early aneurysm treatment (< 24 hours) compared with delayed treatment (> 10 days). |

Early treatment (< 24 hours) compared to non-early treatment (> 24 hours) after SAH: poor outcome

|

Very low GRADE |

Early treatment (< 24 hours) may make no difference on risk of poor outcome compared with treatment > 24 hours for patients who are admitted with WFNS 4 or 5.

Sources: (Han, 2018; Chen, 2016; Luo, 2015; Sandstrom, 2013; Shirao, 2010; Tykocki, 2017; Zhao, 2015) |

IMPORTANT OUTCOME MEASURES

Early treatment (< 24 hours) compared to non-early treatment (> 24 hours) after SAH: rebleeding

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of early treatment (< 24 hours) on proportion of patients with rebleeding when compared with non-early treatment (> 24 hours) after SAH: early treatment might reduce the proportion of patients with rebleeding who are admitted with WFNS 4 or 5.

Sources: Han, 2018; Luo, 2015; Tykocki, 2017; Wong, 2017; Zhao, 2015) |

Early treatment (< 24 hours) compared to non-early treatment (> 24 hours) after SAH

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that compared complications for early treatment compared with non-early treatment. |

Early treatment (< 24 hours) compared to non-early treatment (> 24 hours) after SAH: procedural rebleed

|

- GRADE |

No studies were found that compared procedural rebleeding for early treatment compared with non-early treatment. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Two systematic reviews/meta-analyses (Han, 2018 and Rawal ,2017) and two cohort studies (van Lieshout, 2019 and Wong, 2010) were found that fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

One systematic review compared endovascular treatment within 24 hours with treatment after 24 hours (Rawal, 2017). It included studies till August 2015. Six studies focused on treatment within or after 24 hours. The main outcome was ‘poor outcome’, as defined in the included studies using mRS or GOS. Another outcome of this study was mortality which was available in one to 3 studies depending on the compared timeframes.

The other systematic review specifically looked into patients with poor grade aSAH: WFNS grade 4 or 5 and compared surgery or endovascular treatment within 24 hours with treatment after 24 hours (Han, 2018). Outcome measures described were functional outcome, mortality, rebleeding, and intraoperative technique difficulty (ITD).

Another study using both microsurgical and endovascular treatment (Wong, 2010) (not included in both previous reviews) was found. It evaluated outcome in 276 patients stratified in early (< 24 hours) or intermediate (24 to 72 hours) treatment. Primary outcomes were GOS and mRS at 6 months. Secondary outcomes were reduction in clinical rebleeding, SF-36 scores stratified for poor or good-grade at admission.

The last included study focused on ultra-early treatment within 6 hours. It included 471 patients with aSAH and the main outcome was rebleeding (van Lieshout, 2019). Secondary outcome was the mRS at 6 months.

Results

CRUCIAL OUTCOME MEASURE: ‘POOR’ OUTCOME (mRS or GOS)

Ultra-early ( <6 hours) versus early (< 24 hours) aneurysm treatment

No studies provided data for the evaluation of poor outcome for the ultra-early (< 6 hours) timeframe versus early (< 24hours).

Early (< 24 hours) versus intermediate (24 to 72 hours) aneurysm treatment

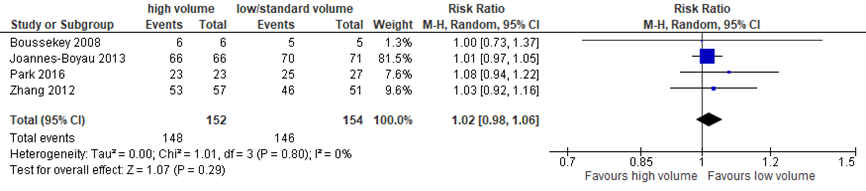

Four studies reported on these timeframes. Total number of poor outcome was 143/618 (23.1%) in the early treatment group and 283/1213 (23.3%) of the intermediate treatment group. The OR for poor outcome was 1.39 (95% CI 0.81 to 2.38) with high heterogeneity (I2=70%) when treatment performed < 24 hours was compared with treatment 24 to 72 hours post-SAH (4 cohorts, 1831 patients), see figure 1. From the original studies, data on surgical treated patients were added. One study had only endovascular treated patients. Three studies had both endovascular and surgically treated patients separately reported. Follow-up ranged from 2-9 months.

Figure 1 Poor outcome: early (< 24 hours) versus intermediate (24 to 72 hours) aneurysm treatment

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Early (< 24 hours) versus delayed (> 10 days) aneurysm treatment

No data are provided for early (< 24 hours) compared to delayed (>1 0 days) for the primary outcome “poor outcome” (mRS or GOS).

IMPORTANT OUTCOME MEASURES: PROCEDURAL REBLEED/ REBLEEDING/ THROMBOEMBOLIC COMPLICATIONS

Ultra-early (< 6 hours) aneurysm treatment versus treatment >6 hours

Procedural rebleed

One study investigated procedural rebleed in relation to timing of treatment. In an endovascularly treated cohort, procedural rebleed was investigated before and after 6 hours. Results showed that 7 out of 66 (11%) rebled when treated within 6 hours and 5 out of 405 (1.2%) rebled if treated after 6 hours (van Lieshout, 2019).

Rebleeding and thromboembolic complications

No studies reported on rebleeding or thromboembolic complications.

Early (< 24 hours) versus intermediate (24 to 72 hours) aneurysm treatment

Rebleed

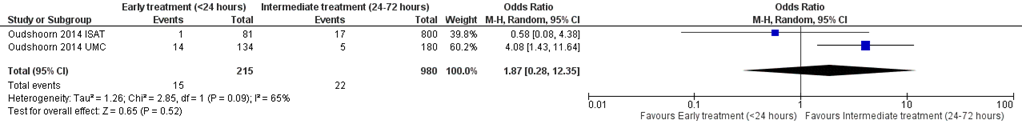

Rebleeding before aneurysm occlusion (endovascular or surgical) occurred in 14/134 patients (10%) with aneurysm treatment < 24 hours and in 5/180 patients (3%) with aneurysm treatment 24 to 72 hours after ictus in the Oudshoorn UMC cohort (Oudshoorn, 2014). Rebleeding occurred in 1/81 patient (1%) treated (endovascular or surgical) at day 0 and in 17/800 patients (2%) treated at days 1–2 (Oudshoorn ISAT). The OR for rebleeding was 1.87 (95% CI 0.28 to 12.35) with high heterogeneity (I2=65%) when treatment performed < 24 hours was compared with treatment 24 to 72 hours post-SAH (2 cohorts, 1195 patients), see figure 2.

Figure 2 Rebleeding: early (< 24 hours) versus intermediate (24 to 72 hours) aneurysm treatment

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Rebleeding and thromboembolic complications

No studies reported on procedural rebleed or thromboembolic complications.

Early (< 24 hours) versus delayed (> 10 days) aneurysm treatment

No studies reported on rebleeding, procedural rebleed or thromboembolic complications.

Subgroup WFNS 4 or 5

CRUCIAL OUTCOME MEASURE: ‘POOR’ OUTCOME (mRS or GOS)

Early (< 24 hours) versus delayed (> 10 days) aneurysm treatment

No studies evaluated early treatment (< 24 hours) versus delayed treatment (> 10 days)

Early (< 24 hours) versus non-early (> 24 hours) aneurysm treatment

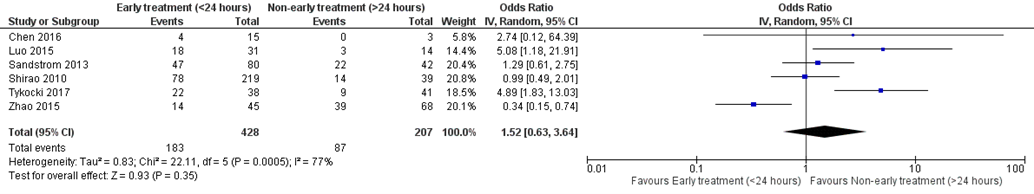

Six studies compared treatment < 24 hours versus > 24 hours, OR for poor outcome was 1.52 (95% CI 0.63 to 3.64) with substantial heterogeneity (I2=77%), see figure 3. This analysis was based on 6 cohorts with 635 patients.

Figure 3 Poor outcome: early (< 24 hours) versus non-early (> 24 hours) aneurysm treatment (subgroup WFNS 4 or 5) (adapted from Han 2018; including only cohorts with at least 6 months follow-up)

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

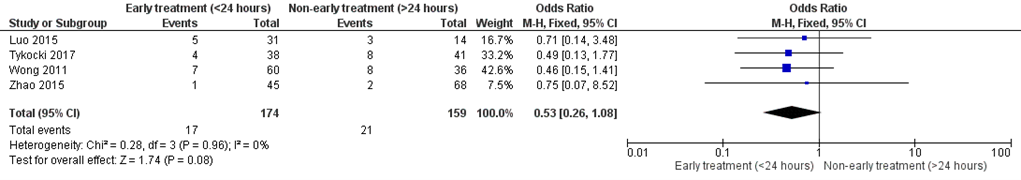

IMPORTANT OUTCOME MEASURE: REBLEEDING

For treatment performed < 24 hours post SAH versus > 24 hours, OR for rebleeding was 0.53 (95% CI 0.26; 1.08) with no heterogeneity (I2=0%), see figure 4. This analysis was based on 4 cohorts with 333 patients.

Figure 4 Rebleeding: early treatment (< 24 hours) versus non-early treatment (> 24 hours)

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect

Other outcomes: adverse events, intra-operative technique difficulty, procedural complications (procedural rebleed and thromboembolic complications for coiling) were not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

Poor outcome: aneurysm treatment within 24 hours compared to treatment 24 to 72 hours

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure poor outcome and rebleeding was very low. It was based on a meta-analyses of retrospective cohort studies which has a low level of evidence. It was further downgraded as there were conflicting results (inconsistency).

Procedural rebleed after ultra-early (< 6 hours) treatment

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure poor outcome was very low. It was based on a retrospective cohort study which has a low level of evidence. It was further downgraded as there was only one study (imprecision).

Subgroup WFNS 4 or 5

Poor outcome: treatment < 24 hours compared to treatment > 24 hours

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure poor outcome was very low. It was based on a meta-analyses of retrospective cohort studies which has a low level of evidence. It was further downgraded as there were conflicting results (inconsistency).

Subgroup WFNS 4 or 5 percentage rebleeding

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure rebleeding was low. It was based on a meta-analyses of retrospective cohort studies which has a low level of evidence. It was further downgraded as the 95% confidence interval crosses the limits of clinical difference (0.8) (imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Does early (< 24 hours after onset) or ultra-early aneurysm treatment (< 6 hours) lead to a better clinical outcome than intermediate (24 to 72 hour) or delayed aneurysm treatment (> 10 days) in patients with aSAH?

P: patients patiënts with aneurysmatic SAH (aSAH) (WFNS 1-3 and WFNS 4-5);

I: intervention ultra-early (< 6 uur after onset) and early (< 24 hour after onset) aneurysm treatment;

C: control intermediate (24 to 72 hour after onset) and delayed (> 10 days after onset) aneurysm treatment;

O: outcome poor outcome (mRankin score 3 to 6 or GOS 1 to 3), rebleeding and adverse events, procedural complications (procedural rebleed and thromboembolic complications for coiling)).

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered poor outcome as a critical outcome measure for decision making and procedural complications (procedural rebleed and thromboembolic complications for endovascular treatment) and other adverse events as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the guideline development group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Poor outcome was defined as mRS 3-6 or GOS 1-3

The guideline development group used the GRADE default limits as limits of clinical difference OR (0.80; 1,25) for minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Pubmed and Embase were searched with relevant search terms until 12th of May 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 435 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria aSAH treatment with coiling or clipping; studies that compared treatment within 6 or 24 hours compared with treatment that more than 6 or 24 hours after aSAH. 57 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening of which 4 systematic reviews. After reading the full text, it was seen that many individual studies were included in the systematic reviews and irrelevant studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), finally two systematic reviews and one cohort study were included. One additional cohort study was added by one of the guideline development group members that was not found in the systematic literature search as it had the publication type ‘letter’.

Results

Four studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- 10 - van Donkelaar CE, Bakker NA, Veeger NJ, Uyttenboogaart M, Metzemaekers JD, Eshghi O, Mazuri A, Foumani M, Luijckx GJ, Groen RJ, van Dijk JM. Prediction of outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage: timing of clinical assessment. J Neurosurg. 2017 Jan;126(1):52-59. doi: 10.3171/2016.1.JNS152136.

- 20 - Han Y, Ye F, Long X, Li A, Xu H, Zou L, Yang Y, You C. Ultra-Early Treatment for Poor-Grade Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018 Jul;115:e160-e171.

- 30 - van Lieshout JH, Verbaan D, Donders R, van den Berg R, Vandertop PWP, Klijn CJM, Steiger HJ, de Vries J, Bartels RHMA, Beseoglu K, Boogaarts HD. Periprocedural aneurysm rerupture in relation to timing of endovascular treatment and outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019 Mar;90(3):363-365.

- 40 - Rawal S, Alcaide-Leon P, Macdonald RL, Rinkel GJ, Victor JC, Krings T, Kapral MK, Laupacis A. Meta-analysis of timing of endovascular aneurysm treatment in subarachnoid haemorrhage: inconsistent results of early treatment within 1 day. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017 Mar;88(3):241-248.

- 50 - Wong GK, Boet R, Ng SC, Chan M, Gin T, Zee B, Poon WS. Ultra-early (within 24 hours) aneurysm treatment after subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2012 Feb;77(2):311-5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.09.025.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: Leidt vroege (< 24 uur) of ultra-vroege behandeling (< 6 uur) tot een betere klinische uitkomst dan behandeling binnen 24 tot 72 uur of uitgestelde behandeling (> 10 dagen) bij patiënten met een geruptureerd aneurysma? mRankin score, percentage rebleeding en adverse events, procedural complications (procedurele rebleed en bij coiling thromboembolische compl

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control I

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Han, 2018

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs and prospective and retrospective cohort and case control studies studies

Literature search up to 12 Jan 2018

A: 1st author, year B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I: .....

Study design: RCT (parallel / cross-over), cohort (prospective / retrospective), case-control

Setting and Country:

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: (commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship) |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

XX studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: XX patients, XX yrs B: C: ….

Sex: A: % Male B: C: ….

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: XX mg; once/twice daily B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I: .....

|

Describe control:

A: placebo; once/twice daily B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I: .....

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: XX days/months/years B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I: ….

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I: ….

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as.....

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference (95% CI): A: B: …

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): …. (95% CI …to…) favoring …. Heterogeneity (I2):

Outcome measure-2 ....

Outcome measure-3 ....

mRankin score, percentage rebleeding en adverse events, procedural complications (procedurele rebleed en bij coiling thromboembolische compl

|

Poor grade aSAH: H-H or wfNS IV or V; clipping or coiling

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained (subgroupanalysis) |

|

Rawal, 2017

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of (RCTs / cohort / case-control studies)

Literature search up to August, 2015

A: ApSimon, 1998 B: Baltsavias, 2000 C: Byme, 2001 D: Consoli et al, 2013 E: Dorhout Mees, 2012 F: Gu et al, 2012 G: Johansson et al, 2004 H: Lawson et al, 2010 I:Luo et al, 2015 J: Norback et al, 2005 K: Oudshoorn et al 2014 (UMC) L: Oudshoorn et al 2014 (ISAT) M: Philips et al, 2011 N: Qian et al, 2014 O: Sandstrom et al, 2013 P: Sluzewski et al, 2003 Q: Wikholm et al, 2000

.....

Study design: cohort (prospective / retrospective) studies

Setting and Country:

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: 1st author is supported by an Association of University Radiologists GE Radiology Research Academic Fellowship Award; PA-L receives grant support from Novartis. RLM receives grant support from the Physicians Services Incorporated Foundation, Brain Aneurysm Foundation, Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada; and is an employee and Chief Scientific Officer of Edge Therapeutics. MKK is supported by a Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Ontario Provincial Office.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Studies could address participants of any age/sex with proven aneurysmal SAH (diagnosed with non-contrast CT head ± lumbar puncture and CT/conventional angiography) that underwent endovascular aneurysm treatment; results had to be presented separately for endovascularly treated patients; impact of treatment timing needed to be evaluated;

Exclusion criteria SR:

15 studies included (one with two cohorts; making a total of 16)

|

Describe intervention: ‘early treatment’ (treatment within 1,2 or 3 days; within 1 day)

A: 4 days B: 2 days C: 6 days D: 2 days E: 2 days F: <24 hours G: 3 days H: 3 days I: <24 hours J: 3 K: <24 hour L:<24 hours M: <24 hours N: <24 hours O: <24 hours P: 3 days Q: 2? …..

|

Describe control: ‘late treatment’ (hours/days)

A: >4 days B: 3-30 days C: 6-30 days D: >48 hours E: >2 days F: >24 hours G: 4-21 days H: 4-10 days I: >24 hours J: 4-21 days K: 24-72 hours L: 24 – 72 hours M: >24 hours N: 24-72 hours O: >24 hours P: 4-60 days Q: 3-15 days? …..

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: XX days/months/years B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I: ….

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I: ….

|

Outcome measure-1 poor clinical/functional outcome reported as a measurement scale (eg modified Rankin scale, Glasgow outcome scale (mRS, GOS) at a specified timeframe (eg discharge, 3 months) Defined as.....

mRankin score, percentage rebleeding en adverse events, procedural complications (procedurele rebleed en bij coiling thromboembolische compl

OR for poor outcome was 1.16 (95% CI 0.47 to 2.90) with high heterogeneity (I2=81%) when treatment performed <1 day was compared with treatment 1–3 days post-SAH (4 cohorts, 1031 patients).

For treatment performed <1 day post-SAH versus >1 day, OR for poor outcome was 0.40 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.56) with no heterogeneity (I2=0%). This analysis was based on 5 cohorts with 853 patients, of which 3 cohorts with 92 patients were based on subgroups of patients selected according to age criteria or clinical condition on admission. Individual data on surgical intervention <24 hours vs 24-72 hours were deducted from the original studies of Ourdhoorn (2014) and Philips (2011).

When early treatment was defined as <2 days (3 cohorts, 1916 patients), the OR for poor outcome was 1.20 (95% CI 0.70 to 2.05, I2=73%) and when it was defined as <3 days (6 cohorts, 1232 patients), the OR was 0.71 (95% CI 0.36 to 1.37, I2=71%); both analyses showed high heterogeneity Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference (95% CI): early treatment was defined as <1 day and late treatment as >1 day was it possible to combine effect estimates. In this subset (2 studies, 141 patients), the OR for poor outcome was 0.28 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.65, I2=0%).

Adjusted odds ratios: One study demonstrated an aOR of 3.27 (95% CI 1.41 to 7.61) for poor outcome in patients treated <1 vs 1– 3 days post-SAH,20 one study demonstrated an aOR of 0.26 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.89) for poor outcome for treatment <1 vs >1 day post-SAH,15 one study demonstrated an aOR of 0.44 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.86) for poor outcome if treatment occurred at <6 days post-SAH compared with later treatment12 and one study demonstrated an aOR of 0.40 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.64) for poor outcome for treatment at <10 days post-SAH.14 One study considered time of treatment as a continuous variable, demonstrating an aOR (per day) of 0.90 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.99) for poor outcome.19 Four studies reporting adjusted analyses demonstrated no significant impact of treatment timing on outcome (aOR=1.31, 95% CI 0.62 to 2.75; aOR=0.94, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.84; aOR=0.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.01; aOR=0.33, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.49). The definition of ‘early’ treatment in these studies ranged from 1 to 3 days.

Outcome measure-2 case fatality at a specified time (e.g. discharge, 3 months) OR for case fatality was 1.80 (95% CI 0.88 to 3.67) with moderate heterogeneity (I2=34%) when treatment was performed <1 vs 1–3 days post-SAH (3 cohorts, 894 patients). Data synthesis addressing treatment <1 vs >1 day could not be performed, since only one study evaluated case fatality with this timing comparison. When early treatment was defined as <2 days (3 cohorts, 951 patients) or <3 days (2 cohorts, 629 patients), Ors for case fatality were 1.71 (95% CI 0.72 to 4.03, I2=54%) and 0.90 (95% CI 0.31 to 2.68, I2=48%), respectively, with moderate-to-high heterogeneity

Adjusted odds ratios: No significant impact of treatment timing on case fatality was demonstrated (aOR=2.19, 95% CI 0.78 to 6.18; aOR=1.65, 95% CI 0.59 to 4.60; aOR=1.49, 95% CI 0.24 to 9.03). Funnel plot suggested publication bias.

Outcome measure-3 Rebleed

Oudshoorn UMC; Rebleeding before aneurysm occlusion occurred in 14 patients (10 %) with aneurysm treatment <24 hours and in 5 patients (3 %) with aneurysm treatment 24–72 h after ictus. Oudshoord ISAT: Oudshoorn UMC: Oudshoorn ISAT: Rebleeding occurred in 1 patient (1 %) treated at day 0 and in 17 patients (2 %) treated at days 1–2.

Philips: NR Qian: NR

Outcome measure-4 Procedural rebleed Oudshoorn: NR

Philips: NR Qian: NR

Outcome measure-5 Thromboembolic complications:

Philips: NR Qian: NR |

Facultative:

Only endovascular treatment

Brief description of author’s conclusion: In only 1 of the analyses was there a statistically significant result, which favoured treatment <1 day. The inconsistent results and heterogeneity within most analyses highlight the lack of evidence for best timing of endovascular treatment in SAH patients.

Opmerkingen: Helder overzicht; zie ook tabel 2 waarin bij iedere studie de definitie van early en late is aangegeven

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control I 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Van Lieshout, 2019 |

Type of study: Cohort study

Setting and country: Neurosurgery department, The Netherlans

Funding and conflicts of interest:. One of the authors (CJMK) is supported by a clinical established investigator grant of the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant number 2012 T077), and an Aspasia grant from The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw grant 015.008.048). Two authors (HDB and JdV) are consultants for Stryker Neurovascular; no competing interests declared |

Inclusion criteria: All consecutive patients with aSAH, treated by endovascular coil embolization at the Radboud University Medical Centre (Nijmegen) and the Academic Medical Centre (Amsterdam) between January 2012 and January 2016

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Coil: 471 Early: 66 Late: 405

Mean age 56.6; SD ±13.1 years

Sex: 31 % M

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ultra-early <24 hours

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Late: >24 hours |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 12%;not included in analysis

Incomplete outcome data: Not described

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

mRs score (0-2) not reported 20

Rebleed Ultra-early 7/66= 11% Late 5/405 = 1,2%

|

|

|

Wong, 2010 |

Type of study: Cohort study

Setting and country: Neurosurgery department, Hong Kong

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study was financially supported by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (CUHK Ref. No. CUHK4183/02M). |

Inclusion criteria: patients age 18 years or older with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhages within 48 hours of ictus and with angiographic evidence 94of intracranial aneurysm as the likely source of the hemorrhage

Exclusion criteria: death within 48 hours after admission was anticipated; major hepatic, pulmonary, or cardiac disease; recent myocardial infarct (within 6 months from ictus); significant renal impairment (plasma creatinine concentration more than 200 ìmol/L); clinical indication or contraindication to magnesium infusion; pre-existing neurological disability from stroke, dementia, or other neurological diseases; or concurrent participation in another clinical trial.

N total at baseline: Coil: 149 (54%) Clip: 127 (46%) Early: 148 (54%) Late: 128 (46%)

Sex: 36 % M

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Ultra-early <24 hours

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Late: >24 hours |

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Not described

Incomplete outcome data: Not described

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Good Neurological outcome OR 1.7 (95% CI 0.9 to 3.0)

mRs score (0-2) early: 94/148 (64%) Late: 76/128 (59%)

Rebleed 6% 7% |

|

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Risk of bias table

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Chen 2016 |

unlikely |

Unlikely (6-36 months) |

unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Gu 2012 |

unlikely |

unlikely (6 months follow-up); |

unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Van Lieshout, 2019 |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Luo 2015 |

unlikely |

unlikely (6 months follow-up); |

unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Oudshoorn 2014 |

unlikely |

unlikely (2 and 3 months follow-up); |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Philips 2011 |

unlikely |

unlikely (6 months follow-up); |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Qian 2014 |

unlikely |

unlikely (9 months follow-up); |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Sandstrom 2013 |

unlikely |

Unlikely (6 months follow-up) |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Wong 2010 |

unlikely |

Unlikely (6 months follow-up) |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Zhao 2015 |

unlikely |

Unlikely (mean 12.5 months) |

unlikely |

unlikely |

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- 2 Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

An, 2019 |

Other PICO, danger of cerebral angiography within 3 hours |

|

Attenello, 2014 |

Other PICO, about health disparities |

|

Attenello, 2016 |

Other PICO |

|

Chee 2018 |

Malaysia, not comparable |

|

Dalbayrak 2011 |

Treatment within three days compared to after three days, not PICO |

|

D’Andrea 2020 |

Case series outcome vasospasm and hydrocephalus |

|

Das, 2017 |

Other PICO |

|

Dellaretti, 2018 |

Brazile, not comparable |

|

Dijkland, 2019 |

Other PICO, between centre differences SAHIT |

|

Donoho, 2018 |

Other PICO |

|

Dorhout-Mees, 2012 |

In reviews |

|

Germans and Hoogmoed, 2014 |

Other PICO |

|

Germans 2014 |

Other PICO, rebleed |

|

Golchin, 2012 |

Treatment within 4 days compared to after 7 days; other PICO |

|

Gu, 2012 |

In review Rawal 2017 |

|

Guo 2010 |

Treatment within 3 days compared to after 3 days |

|

Hashemi 2011 |

Treatment within 3 days compared to 4-7 days and after 7 days |

|

Hashemi 2019 |

Other PICO |

|

He, 2010 |

Other PICO |

|

Hoogmoed, 2018 |

Other PICO |

|

Ibrahim Ali, 2016 |

Pilot with 30 patients, follow-up only 30 days; unclear if it counted from presentation or onset (in text “24 hours of presentation”) |

|

Inamasu, 2016 |

Other PICO |

|

Jiang, 2019 |

Other PICO |

|

Kienzler, 2019 |

Other PICO |

|

Lawson, 2010 |

Within 3 days compared to after 3 days |

|

Linzey, 2018 (2x) |

Retrospective cohort study |

|

Luo, 2015 |

In review Han and Rawal |

|

Mahaney, 2011 (2x) |

Treatment day 1 and 2 compared to day 7 to 14 |

|

Matias-Guio, 2013 |

General overview |

|

Mitra, 2015 |

RCT with 8 patients |

|

Oppong, 2019 |

Predictors rupture |

|

Oudshoorn, 2014 |

In review Rawal 2017 |

|

Park 2015 |

Retrospective comparison using emergency treatment protocol |

|

Philips, 2011 |

In review Zhao |

|

Qian, 2017 |

Other PICO wide neck aneurysms |

|

Sarmiento, 2015 |

Predictors early treatment |

|

Siddiq, 2012 |

Predictors early treatment |

|

Sonig, 2018 |

Other PICO, costs |

|

Tan, 2014 |

Other PICO; aneurysm with acute hydrocephalus |

|

Taylor, 2011 |

Other PICO |

|

Tykocki, 2017 |

Other PICO, poor grade aSAB |

|

Van Donkelaar, 2020 |

Other PICO, death with or without dependency at 3 or 5 years |

|

Vergouwen, 2016 |

Other PICO, starts with in-hospital death |

|

Wang 2019 |

Other PICO |

|

Wong, 2012 |

In review Han |

|

Yao 2017 |

Compares treatment within or after three days instead of 24 hours as in the PICO |

|

Yu, 2013 |

Other PICO |

|

Zhang 2013 |

Protocol RCT |

|

Zhang, 2017 |

Other PICO |

|

Zhao 2010 |

Microsurgery within or after 3 days |

|

Zhao, 2014 |

Other PICO |

|

Zhao 2015 |

Other PICO |

|

Zhao 2016 |

Compares treatment within or after three days instead of 24 hours as in the PICO |

|

Zhao, 2017 |

SR in Turkish neurosurgery |

|

Zheng, 2016 |

Other PICO |

|

Zheng, 2018 |

Other PICO; aggressive treatment compared to palliative treatment |

|

Zhou, 2014 |

Treatment within or after 72 hours |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 07-10-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 02-08-2022

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werk- en klankbordgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met (verdenking op) subarachnoïdale bloeding.

Werkgroep

- Dr. M.D.I. Vergouwen, neuroloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, voorzitter (NVN)

- Drs. J. Manuputty, neuroloog, Elisabeth-Twee Steden Ziekenhuis, Tilburg (NVN)

- Prof. dr. G.J.E Rinkel, neuroloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (NVN)

- Dr. I.R. van den Wijngaard, neuroloog, Haaglanden MC, Den Haag (NVN)

- Dr. H.D. Boogaarts, neurochirurg, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen (NVvN)

- Prof. dr. J.M.C. van Dijk, neurochirurg, UMCG, Groningen (NVvN)

- Dr. R. van den Berg, radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam (NVvR)

- Dr. G.J. Lycklama à Nijheholt, radioloog, Haaglanden MC, Den Haag (NVvR)

- Dr. W.J.M. Schellekens, anesthesioloog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (tot okt 2020) (NVA)

- Dr. A. Akkermans, anesthesioloog, Fellow Intensive Care, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (vanaf okt 2020) (NVA)

- Dr. M. van der Werf, revalidatiearts, Rijndam revalidatie, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam (VRA)

- Dr. M. van der Jagt, neuroloog-intensivist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam (NVIC)

- J. Hennipman-Bikker, verpleegkundige, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht (tot sep 2021) (V&VN)

- J.C. Toerse, MSc, verpleegkundig specialist, Isala, Zwolle (vanaf nov 2021) (V&VN)

Klankbord

- Carola Deurwaarder, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Hersenaneurysma Patiënten Platform

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. M. Molag, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. A. Balemans, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Achternaam werkgroeplid |

Hoofdfunctie |

Neven werkzaamheden |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie |

Overige belangen |

Actie |

|

* Vergouwen |

Neuroloog UMC Utrecht, afdeling Neurologie en Neurochirurgie |

Geen |

Vergoedingen aan UMC Utrecht van: - NeuroScios (ivm reviewer van klinische data ihkv NicaPlant studie (Phase llb : randomized, - CSL Behring voor een eenmalige advisory board meeting over een eventueel nieuw onderzoek. |

Mijn wetenschappelijk onderzoek wordt gefinancieerd door de Hartstichting, Hersenstichting, ZonMw, Vrienden UMC Utrecht, Dr Rolf Schwiete stichting.

Hoofd-onderzoeker van een fase II onderzoek naar de veiligheid en werkzaamheid van eculizumab bij patienten met een subarachnoidale bloeding, mede-gefinancierd door de producent van het middel, Alexion Pharma |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen: eculizumab zal niet worden behandeld in de richtlijn |

|

Van der Werf |

Revalidatiearts bij Rijndam locatie Erasmus MC |

Werkgroep WHR, onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van den Berg |

Interventie neuro-radioloog |

Consultant bij Cerenovus neurovascular (onderdeel van Johnson & Johnson) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Lycklama à Nijeholt |

Radioloog Haaglanden MC Den Haag |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van Dijk |

Afdelingshoofd Neurochirurgie UMCG |

Voorzitter Neurovasculair Expertisecentrum UMCG (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van der Jagt |

Neuroloog-intensivist |

Voorzitter commissie richtlijnontwikkeling van de NVIC (onbetaald). Commissielid van de Adviescommissie richtlijnen SKMS2 |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Manuputty |

Neuroloog ETZ (Elisabeth TweeSteden Ziekenhuis (Tilburg) |

Bestuurslid Vereniging Nederlandse Hoofdpijncentra (VNHC) tot 2021; onbetaald |

Geen |

Deelname aan studie "Determinants of physical behaviour after SAH", |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Rinkel |

Hoogleraar neurologie, UMC Utrecht, 1.0FTE |

Geen |

Geen |

Lid van de stuurgroep van ULTRA, een door de Nederlandse Hartstichting gefinancieerd fase III onderzoek naar de effectiviteit van tranexaminezuur bij patienten met een subarachoidale bloeding |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen: eculizumab zal niet worden behandeld in de richtlijn |

|

Hennipman-Bikker |

Medium Care verpleegkundige op de Medium Care Neurologie / Neurochirurgie |

Geen |

Geen persoonlijke financiele belangen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Van den Wijngaard |

Vasculair neuroloog, Haaglanden MC & LUMC (40%) |

Bestuurslid Nederlands Neurovasculair Genootschap (onbetaald) Imaging committee MR Clean Studies (onbetaald) |

nvt |

nvt |

|

nvt |

Geen |

|

Schellekens |

Anesthesioloog, staflid UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

nvt |

Geen |

|

Boogaarts |

Neurochirurg, RadboudMC, Nijmegen |

Voorzitter stichting kwaliteit neurochirurgie (onkostenvergoeding). Voorzitter QRNS (Quality Registry Neurosurgery SAB (onbetaald). Voorzitter Nederlands Neurovasculair genootschap (onbetaald). |

Consultant Stryker Neurovascular (vergoeding gaat naar afdeling). Endovasculaire producten (coils, flow diverters, stroke). Advies tijdens proceduren, presentaties op congres, onderwijs |

SKMS subsidie voor ontwikkelen PROM SAB |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen penvoerder module over endovasculaire producten |

|

Akkermans |

Anesthesioloog / Fellow Intensive Care UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

|

Toerse |

Verpleegkundig specialist, Isala Zwolle, afdeling neurochirurgie |

Geen |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door afvaardiging van het Hersenaneurysma Patiënten Platform in de klankbordgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen en aanbevelingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan het Hersenaneurysma Patiënten Platform.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met subarachnoïdale bloeding. De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbeveling(en) uit de eerdere richtlijnmodules (NVN, 2013) op noodzaak tot revisie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen via een schriftelijke knelpuntanalyse. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Guideline development group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Guideline development group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Guideline development group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Guideline development group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/werkwijze/richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Guideline development group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Uitgangsvraag: UV3 SAB. Wat is de waarde van vroege behandeling bij patiënten met een geruptureerd aneurysma? |

|

|

Database(s): PubMed, Embase |

Datum: 12-5-2020 |

|

Periode: 2010- |

Talen: nvt |

|

Toelichting:

Alle sleutelartikelen werden gevonden. Vanwege de tijdslimiet zit het volgende artikel niet in het resultaat: Whitfield PC, Kirkpatrick PJ. Timing of surgery for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;8:CD001697 |

|

|

|

Inclusief dubbele referenties |

Ontdubbeld en tijdslimiet aangescherpt vanaf 2010 |

|

SR |

23 |

18 |

|

RCT |

178 |

89 |

|

Observationeel |

425 |

328 |

|

Totaal |

|

435 |

Zoekverantwoording

PubMed

|

Search |

Query |

Items found |

|

#31 |

Search #29 NOT #28 NOT #27 |

155 |

|

#30 |

Search #28 NOT #27 |

14 |

|

#27 |

Search #23 AND #26 |

4 |

|

#29 |

Search #25 AND #26 |

170 |

|

#28 |

Search #24 AND #26 |

15 |

|

#26 |

Search #4 AND #14 AND #21 Filters: Publication date from 2010/01/01 |

184 |

|

#22 |

Search #4 AND #14 AND #21 |

412 |

|

#25 |

Search "Epidemiologic Studies"(Mesh) OR cohort(tiab) OR (case(tiab) AND (control(tiab) OR controll*(tiab) OR comparison(tiab) OR referent(tiab))) OR risk(tiab) OR causation(tiab) OR causal(tiab) OR "odds ratio"(tiab) OR etiol*(tiab) OR aetiol*(tiab) OR "natural history"(tiab) OR predict*(tiab) OR prognos*(tiab) OR outcome(tiab) OR course(tiab) OR retrospect*(tiab) |

6606444 |

|

#24 |

Search ((random*(tiab) AND (controlled(tiab) OR control(tiab) OR placebo(tiab) OR versus(tiab) OR vs(tiab) OR group(tiab) OR groups(tiab) OR comparison(tiab) OR compared(tiab) OR arm(tiab) OR arms(tiab) OR crossover(tiab) OR cross-over(tiab)) AND (trial(tiab) OR study(tiab))) OR ((single(tiab) OR double(tiab) OR triple(tiab)) AND (masked(tiab) OR blind*(tiab)))) |

728036 |

|

#23 |

Search ("Meta-Analysis as Topic"(Mesh) OR “Meta-Analysis”(Publication Type) OR metaanaly*(tiab) OR metanaly*(tiab) OR meta-analy*(tiab) OR meta synthes*(tiab) OR metasynthes*(tiab) OR meta ethnograph*(tiab) OR metaethnograph*(tiab) OR meta summar*(tiab) OR metasummar*(tiab) OR meta-aggregation(tiab) OR metareview(tiab) OR meta-review(tiab) OR overview of reviews(tiab) OR ((systematic*(ti) OR scoping(ti) OR umbrella(ti) OR meta-narrative(ti) OR metanarrative(ti) OR evidence based(ti)) AND (review*(ti) OR overview*(ti))) OR ((evidence(ti) OR narrative(ti) OR metanarrative(ti) OR qualitative(ti)) AND synthesis(ti)) OR systematic review(pt) OR prisma(tiab) OR preferred reporting items(tiab) OR quadas*(tiab) OR systematic review*(tiab) OR systematic literature(tiab) OR structured literature search(tiab) OR systematic overview*(tiab) OR scoping review*(tiab) OR umbrella review*(tiab) OR mapping review*(tiab) OR systematic mapping(tiab) OR evidence synthes*(tiab) OR narrative synthesis(tiab) OR metanarrative synthesis(tiab) OR research synthesis(tiab) OR qualitative synthesis(tiab) OR realist synthesis(tiab) OR realist review(tiab) OR realist evaluation(tiab) OR systematic qualitative review(tiab) OR mixed studies review(tiab) OR mixed methods synthesis(tiab) OR mixed research synthesis(tiab) OR quantitative literature review(tiab) OR systematic evidence review(tiab) OR evidence-based review(tiab) OR comprehensive literature search(tiab) OR integrated review*(tiab) OR integrated literature review(tiab) OR integrative review*(tiab) OR integrative literature review*(tiab) OR structured literature review*(tiab) OR systematic search and review(tiab) OR meta-narrative review*(tiab) OR metanarrative review(tiab) OR systematic narrative review(tiab) OR systemic review(tiab) OR systematized review(tiab) OR systematic research synthesis(tiab) OR bibliographic*(tiab) OR hand-search*(tiab) OR handsearch*(tiab) OR manual search*(tiab) OR searched manually(tiab) OR manually searched(tiab) OR journal database*(tiab) OR review authors independently(tiab) OR reviewers independently(tiab) OR independent reviewers(tiab) OR independent review authors(tiab) OR electronic database search*(tiab) OR (study selection(tiab) AND data extraction(tiab)) OR (selection criteria(tiab) AND data collection(tiab)) OR (selection criteria(tiab) AND data analysis(tiab)) OR (evidence acquisition(tiab) AND evidence synthesis(tiab)) OR (pubmed(tiab) AND embase(tiab)) OR (medline(tiab) AND embase(tiab)) OR (pubmed(tiab) AND cochrane(tiab)) OR (medline(tiab) AND cochrane(tiab)) OR (embase(tiab) AND cochrane(tiab)) OR (pubmed(tiab) AND psycinfo(tiab)) OR (medline(tiab) AND psycinfo(tiab)) OR (embase(tiab) AND psycinfo(tiab)) OR (cochrane(tiab) AND psycinfo(tiab)) OR (pubmed(tiab) AND web of science(tiab)) OR (medline(tiab) AND web of science(tiab)) OR (embase(tiab) AND web of science(tiab)) OR (psycinfo(tiab) AND web of science(tiab)) OR (cochrane(tiab) AND web of science(tiab)) OR ((literature(ti) OR qualitative(ti) OR quantitative(ti) OR integrated(ti) OR integrative(tiab) OR rapid(ti) OR short(ti) OR critical*(ti) OR mixed stud*(ti) OR mixed method*(ti) OR focused(ti) OR focussed(ti) OR structured(ti) OR comparative(ti) OR comparitive(ti) OR evidence(ti) OR comprehensive(ti) OR realist(ti)) AND (review*(ti) OR overview*(ti)) AND (literature search(tiab) OR structured search(tiab) OR electronic search(tiab) OR search strategy(tiab) OR gray literature(tiab) OR grey literature(tiab) OR Review criteria(tiab) OR eligibility criteria(tiab) OR inclusion criteria(tiab) OR exclusion criteria(tiab) OR predetermined criteria(tiab) OR included studies(tiab) OR identified studies(tiab) OR (systematic search(tiab) AND literature(tiab)) OR strength of evidence(tiab) OR citation*(tiab) OR references(tiab) OR database search*(tiab) OR electronic database*(tiab) OR data base search*(tiab) OR electronic data-base*(tiab) OR search criteria(tiab) OR study selection(tiab) OR data extraction(tiab) OR methodological quality(tiab) OR methodological characteristics(tiab) OR methodologic quality(tiab) OR methodologic characteristics(tiab))) OR ((literature review(tiab) OR literature search*(tiab)) AND (structured search(tiab) OR electronic search(tiab) OR Search strategy(tiab) OR gray literature(tiab) OR grey literature(tiab) OR review criteria(tiab) OR eligibility criteria(tiab) OR inclusion criteria(tiab) OR exclusion criteria(tiab) OR predetermined criteria(tiab) OR included studies(tiab) OR identified studies(tiab) OR (systematic search(tiab) AND literature(tiab)) OR strength of evidence(tiab) OR citation*(tiab) OR references(tiab) OR database search*(tiab) OR electronic database*(tiab) OR data base search*(tiab) OR electronic data-base*(tiab) OR search criteria(tiab) OR study selection(tiab) OR data extraction(tiab) OR methodological quality(tiab) OR methodological characteristics(tiab) OR methodologic quality(tiab) OR methodologic characteristics(tiab)))) NOT ("Comment" (Publication Type) OR "Letter" (Publication Type)) NOT (“Animals”(Mesh) NOT “Humans”(Mesh)) |

343332 |

|

#21 |

Search "Time"(Mesh) OR timing(tiab) OR time(tiab) OR early treat*(tiab)OR 24 hour*(tiab) |

4236445 |

|

#14 |

Search Intracranial Aneurysm/surgery"(Mesh) OR "Intracranial Aneurysm/therapy"(Mesh) OR aneurysm resection(tiab) OR aneurysm surgery(tiab) OR aneurysma resection(tiab) OR aneurysmectomy(tiab) OR aneurysm clipping(tiab) OR aneurysma clipping(tiab) OR endovascular aneurysm repair(tiab) OR endovascular coiling(tiab) OR stent assisted coiling(tiab) |

10471 |

|

#4 |

Search "Subarachnoid Hemorrhage"(Mesh) OR subarachnoid bleed*(tiab) OR subarachnoid blood(tiab) OR subarachnoid haematoma*(tiab) OR subarachnoid haemorrhag*(tiab) OR subarachnoid hematom*(tiab) OR subarachnoid hemorrhag*(tiab) OR subarachnoidal bleed*(tiab) OR subarachnoidal haemorrhag*(tiab) OR subarachnoidal hemorrhag*(tiab) |

31051 |

Embase

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#23 |

#13 AND #22 |

2 |

|

#22 |

. AND early AND treatment AND decisions AND in AND 'poor grade' AND patients AND with AND subarachnoid AND hemorrhage AND hoogmoed |

2 |

|

#21 |

#19 NOT #18 NOT #17 |

270 |

|

#20 |

#18 NOT #17 |

164 |

|

#19 |

#11 AND #13 |

352 |

|

#18 |

#10 AND #12 |

172 |

|

#17 |

#9 AND #13 |

19 |

|

#16 |

#7 AND #12 |

6 |

|

#15 |

#7 NOT #14 |

2 |

|

#14 |

#7 AND #13 |

4 |

|

#13 |

#12 AND (2010-2020)/py NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

458 |

|

#12 |

#1 AND #2 AND #8 |

1475 |

|

#11 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

5234909 |

|

#10 |

('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it |

2340458 |

|

#9 |

('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

473856 |

|

#8 |

'time'/exp OR tim*:ti,ab,kw OR 'early treatment'/exp OR 'early treat*':ti,ab,kw OR ((24 NEAR/4 hour*):ti,ab,kw) |

5615207 |

|

#7 |

#3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 |

6 |

|

#6 |

timing AND of AND surgery AND for AND aneurysmal AND subarachnoid AND hemorrhage AND yao |

1 |

|

#5 |

timing AND of AND surgery AND for AND aneurysmal AND subarachnoid AND haemorrhage AND whitfield |

3 |

|

#4 |

hyperacute AND versus AND subacute AND coiling AND of AND aneurysmal AND subarachnoid AND hemorrhage AND a AND 'short term' AND outcome AND 'single center' AND experience AND ali |

1 |

|

#3 |

aneurysm AND treatment AND 24 AND versus AND '24 72' AND h AND after AND subarachnoid AND hemorrhage AND oudshoorn |

1 |

|

#2 |

'aneurysm surgery'/exp OR 'aneurysm resection':ti,ab,kw OR 'aneurysm surgery':ti,ab,kw OR 'aneurysma resection':ti,ab,kw OR 'aneurysmectomy':ti,ab,kw OR 'aneurysm clipping':ti,ab,kw OR 'aneurysma clipping':ti,ab,kw OR 'endovascular aneurysm repair':ti,ab,kw OR 'endovascular coiling':ti,ab,kw OR 'stent assisted coiling':ti,ab,kw OR ((surg* NEAR/4 aneurysm*):ti,ab,kw) OR 'aneurysm treatment':ti,ab,kw |

41046 |

|

#1 |

'subarachnoid hemorrhage'/exp OR 'subarachnoid bleed*':ti,ab,kw OR 'subarachnoid blood':ti,ab,kw OR 'subarachnoid haematoma*':ti,ab,kw OR 'subarachnoid haemorrhag*':ti,ab,kw OR 'subarachnoid hematom*':ti,ab,kw OR 'subarachnoid hemorrhag*':ti,ab,kw OR 'subarachnoidal bleed*':ti,ab,kw OR 'subarachnoidal haemorrhag*':ti,ab,kw OR 'subarachnoidal hemorrhag*':ti,ab,kw |

49381 |