Vroege effecten bij het kind door gebruik van SSRI’s tijdens de zwangerschap

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de effecten van het gebruik van antidepressiva Selective Serontonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI’s) in de zwangerschap op het functioneren van het kind in de eerste week postpartum met betrekking tot neonatale symptomen, onthoudingsverschijnselen en het risico op NICU-opname (en hoe is de monitoring van de neonaat?)

Aanbeveling

Bespreek het risico op PPHN en PNAS met de zwangere die SSRI’s gebruikt.

Observeer neonaten geboren uit vrouwen die SSRI tijdens de zwangerschap hebben gebruikt minimaal 12 uur in een klinische setting onder verantwoordelijkheid van de kinderarts.

Pas bij gebruik van een hoge dosis, meerdere psychotrope medicaties of prematuriteit een geïndividualiseerd beleid toe ten aanzien van de duur van de observatie.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er werden geen RCT’s gevonden die gebruik van SSRI’s vergeleken met geen gebruik van SSRI’s. De beschikbare observationele studies waren van wisselende kwaliteit, de overall bewijskracht was zeer laag (bewijskracht cruciale uitkomstmaat mortaliteit zeer laag). Een probleem is dat in veel studies zwangere vrouwen met depressie en SSRI-gebruik werden vergeleken met zwangere vrouwen zonder depressie en SSRI-gebruik.

Vanuit grote observationele studies is er een matig bewijs dat kinderen geboren uit moeders die SSRI gebruiken een verhoogde kans hebben op PPHN en PNAS. De adaptatiestoornissen komen bij 25 tot 30% van de kinderen voor.

Voor de overige uitkomstmaten zoals mortaliteit, Apgar score, geboortegewicht, foetale groei restrictie is er geen bewijs of er een verhoogd risico is bij gebruik van SSRI in de zwangerschap. Dit gebrek aan bewijs komt met name doordat er nauwelijks studies gedaan zijn naar deze uitkomstmaten.

In andere landen zoals de Verenigde Staten en het Verenigd Koninkrijk zijn er geen landelijke richtlijnen die uitspraken doen over de controle van de moeder of de opvang van haar kind.

In Nederland vermeldt het LAREB (TIS) dat na langdurig gebruik van antidepressiva (tot aan de bevalling) het pasgeboren kind onthoudingsverschijnselen kan krijgen. Het optreden van persisterende pulmonale hypertensie bij de neonaat (PPHN) is beschreven bij het gebruik van SSRI’s. Het advies van het LAREB is om het kind na de geboorte voor alle zekerheid te controleren op verschijnselen van PPHN, zoals blauwe verkleuring en ademhalingsproblemen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De manier en inhoud van de voorlichting aan patiënten heeft grote invloed op de keuze al dan niet door te gaan met medicatie. In de praktijk blijkt vaak dat huisartsen of behandelaars met minder ervaring in de psychiatrie eerder geneigd zijn te adviseren om te stoppen met psychofarmaca. Vanuit de POP poli is na goede counseling de ervaring dat patiënten juist wel doorgaan hiermee. In de afweging om te stoppen of door te gaan met de psychofarmaca is de balans tussen de toxicologische risico’s voor het kind, de kans op een terugval danwel exacerbatie van de ziekte en de gevolgen hiervan voor het kind belangrijke afwegingen.

Vermeld moet worden dat er weinig evidence is en dat het niet altijd duidelijk is of sommige neonatale problemen, bijvoorbeeld respiratoire problemen, komen door medicatiegebruik of niet.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Omdat er toch aanwijzingen zijn dat er een vergrote kans is op PPHN en PNAS, ook vanuit farmacologisch oogpunt, is het de aanbeveling om de geboorte te laten plaatsvinden daar waar opvang voor het kind is, met name voor observatie van de transitiefase. Het absolute risico op PPHN is weliswaar laag, maar PPHN is een ernstige aandoening met een hoge morbiditeit en mortaliteit die spoedbehandeling vereist. De behandeling bestaat uit kunstmatige ventilatie, ondersteuning van de systemische bloeddruk met vulling en inotropica en toediening van NO via inhalatie. Wanneer deze therapie faalt, is extra corporele membraan oxygenatie (ECMO) nodig. Zelfs met deze geavanceerde zorg ligt de mortaliteit nog tussen de 10 en 20% (Masarwa, 2019; Silvani, 2007).

De precieze relatie tussen SSRI’s en PPHN is nog niet opgehelderd. Hogere serumwaarden van serotonine in de foetus zouden mogelijk kunnen leiden tot vasoconstrictie en proliferatie van gladde spiercellen, wat karakteristiek is voor PPHN. Een andere voorgesteld mechanisme is vroegtijdige constrictie van de ductus arteriosus, beschreven in aan SSRI blootgestelde foetale muizen. Verdere studies zijn echter nodig om de potentiele relatie tussen SSRI’s en PPHN te duiden (Huybrechts, 2015; Ulbrich, 2021).

De meest voorkomende symptomen van adaptatiestoornissen zijn: respiratoire problemen, tremoren, hypotonie, gastro-intestinale stoornissen, hoog huilen en slaapstoornissen. De stoornissen ontwikkelen zich meestal binnen de eerste twee dagen na de geboorte en zijn meestal binnen 14 dagen postpartum zonder specifieke interventies verdwenen. Een extra risicofactor voor het ontwikkelen van matige neonatale adaptatie is prematuriteit (Ferreira, 2007). Van alle blootgestelde neonaten ontwikkelt 20-30% in meer of mindere mate adaptatie symptomen. Of deze ontstaan is mede afhankelijk van de aanwezigheid van maternale angst- en depressieve klachten tijdens de zwangerschap en genetische kwetsbaarheid. De dosering van SSRI’s heeft geen relatie met het ontstaan van adaptatie symptomen. Borstvoeding beschermt tegen deze ontwenningssymptomen na maternaal SSRI gebruik (Kieviet, 2016).

Respiratoire problemen bij neonaten na intrauterine SSRI-blootstelling kunnen varieren van milde tachypnoe tot ernstige respiratoire insufficientie en beademingsbehoefte (Moses-Kolko, 2005). In de praktijk worden met enige regelmaat aterme kinderen gezien met respiratoire distress of zuurstofbehoefte zonder duidelijke verklaring, voor wie respiratoire ondersteuning in de vorm van cpap of flow nodig is. Soms is maternaal SSRI-gebruik dan de enige potentieel geassocieerde factor. De meeste kinderen knappen over het algemeen in de loop van 1 tot 2 dagen op, maar zouden mogelijk zonder snelle interventie middels respiratoire ondersteuning verder verslechterd zijn. Het is om die reden niet ondenkbaar dat een deel van de kinderen met PNAS-symptomen, i.e. de kinderen met respiratoire problemen, toch een milde vorm van pulmonale hypertensie hebben, die snel ondervangen en behandeld is. Deze overlap tussen kinderen met PNAS en PPHN kan tot een onderschatting hebben geleid van het aantal kinderen met PPHN in de geïncludeerde studies. Op grond van de verhoogde kans op PPHN, waarvan de behandeling alleen klinisch mogelijk is, is het het veiligst om zwangere vrouwen die in het laatste trimester een SSRI gebruikt hebben de overweging mee te geven poliklinisch te bevallen en daarna de pasgeborene gedurende minimaal twaalf uur klinisch te observeren op symptomen van PPHN. Deze observatie kan op de kraamafdeling onder de verantwoordelijkheid van de kinderarts. Ten aanzien van symptomen van PPHN is het zinvol om te observeren op tachypnoe, dyspnoe en bij vooerkeur de pre- en postductale O2-saturatie te meten. Ten aanzien van pNAS kan ter objectivering van de symptomen overwogen worden om de verkorte Finnegan-scorelijst (voor neonatale adaptatie na intra-uterien blootstelling aan antidepressiva) bij te houden (Kieviet, 2014). Na de eerste 12 uur observatie zou dit dus ook thuis kunnen mits de kraamverzorgende goed geinstrueerd is (let wel: symptomen van neonatale ontwenning kunnen aspecifiek zijn en deels overlap vertonen met die van een beginnende infectie). Bij gebruik van een hoge dosis van de SSRI, meerdere psychotrope medicaties of prematuriteit kan geïndividualiseerd beleid ten aanzien van de duur van de observatie van toepassing zijn.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Update richtlijn module 2012: Wanneer tijdens het gebruik van SSRI’s een zwangerschap optreedt of als het voorschrijven van SSRI’s noodzakelijk is tijdens zwangerschap en/of kraambed, is er bij zwangere- en kraamvrouwen en zorgverleners behoefte aan informatie over het gebruik van deze medicatie en de effecten ervan op moeder en kind.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Very low GRADE |

Neonatal mortality within 28 days of birth

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prenatal exposure to SSRIs on neonatal mortality within 28 days of birth.

Sources: (Jimenez-Solem, 2013; Stephansson, 2013) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension (PPHN)

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prenatal exposure to SSRIs on the risk of PPHN.

Sources: (Andrade, 2009; Bérard, 2017; Chambers, 2006; Colvin, 2012; Hammad, 2009; Huybrechts, 2015; Kieler, 2012; Nörby, 2016; Wilson, 2011) |

|

Low GRADE |

Poor Neonatal Adaptation Syndrome (PNAS)

The evidence suggests prenatal exposure to SSRIs increases the risk of PNAS.

Sources: (Malm, 2015; Costei, 2002; Davis, 2007; Laine, 2003; Wen, 2006) |

|

Very low GRADE |

5 minute Apgar score < 7

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prenatal exposure to SSRIs on the risk of a 5 minute Apgar score < 7.

Sources: (Malm, 2015; Bakaysa, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Low birthweight (< 2500 g)

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prenatal exposure to SSRIs on the risk of low birthweight.

Sources: (Grzeskowiak, 2012; Klieger-Grossmann, 2012; Wen, 2006) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Small for gestational age (SGA)

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prenatal SSRI exposure on the risk of SGA.

Sources: (Grzeskowiak, 2012; Malm, 2015; Sujan, 2017; Toh, 2009) |

|

Very low GRADE |

NICU admission

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of prenatal exposure to SSRIs on the risk of NICU admission.

Sources: (Casper, 2003; Grzeskowiak, 2012; Malm, 2015; Altamura, 2013; Klieger-Grossmann, 2012; Sivojelezova, 2005) |

|

- GRADE |

Due to a lack of research data, no conclusions can be drawn on the effects of prenatal SSRI exposure on the risk of non-NICU admission, umbilical cord pH, or prolonged QT c-interval.

Sources: (Heikkinen, 2002) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women with depression

Studies included from national guideline (published October 2012):

Casper (2003) conducted a case control study in a women’s wellness clinic in the US. They included pregnant women who met DSM-IV criteria for Major Depressive Disorder during pregnancy and gave informed consent to participate in the study (n=44). They compared the proportion of neonates who were admitted to NICU between women with major depressive disorder who were exposed to SSRIs (sertraline, fluoxetine, paroxetine) during pregnancy (n=31) and women with major depressive disorder who were not exposed to SSRI during pregnancy (n=13). Of the women who were exposed to SSRIs, 45% took SSRIs throughout the pregnancy, 71% took SSRIs during the first trimester, and 74% took SSRIs during the third trimester.

Studies included from new search (2019):

Grzeskowiak (2012) conducted a retrospective cohort study using linked records from the Women’s and Children’s Health Network in South Australia. They included pregnant women who gave birth to singleton, live-born infants between September 2000 and December 2008 (n = 33,965). They excluded women exposed to antidepressants other than SSRIs or antipsychotics. Women whose pharmacy records indicated dispensation of SSRIs during pregnancy were compared with women with psychiatric illness who had no dispensation of SSRIs during pregnancy. Outcomes were low birthweight (< 2500 g), SGA, and NICU admission.

Malm (2015) conducted a registry study with data from the Finnish national Medical Birth Register. They included all live singleton births in Finland between January 1, 1996, and December 31, 2010. Children born to women who had purchased SSRIs between 30 days before gestation and the end of pregnancy were considered exposed to SSRIs. Children born to women with any diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder related to SSRI use between 1 year before gestation and discharge from hospital after delivery, who did not purchase antidepressants or antipsychotics between 3 months before gestation and delivery were considered unexposed to SSRIs. A total of 25,381 children were included. Outcomes were SGA, 5-minute Apgar score below 7, NICU admission, and PNAS (breathing problems).

Viktorin (2016) conducted a registry study using data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register. Their dataset included all children born in Sweden between April 1, 2006 and December 31, 2009 (n=392,029), excluding stillbirths and twins. Children born to women with more than one SSRI dispensation between conception and delivery, or one dispensation within the pregnancy period and at least one more dispensation within 6 months before or after the dispensation during pregnancy were considered exposed to SSRIs. Children born to women with depression but no SSRI dispensation during pregnancy were considered unexposed to SSRIs. Outcome was birthweight.

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women without depression

Systematic reviews:

Masarwa (2019) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the association between exposure to SSRIs and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) during pregnancy and the risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the new-born (PPHN). They searched MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane databases up to July 2017 for manuscripts and abstracts reporting results from cohort and case control studies with outcomes reported as ORs or RRs. They excluded cross-sectional studies, case reports, case series, guidelines, expert opinions, editorials, letters to the editor, comments, and studies including data reported in a more recent publication. Of the primary articles included in the review (n=11), one article included exposure to antidepressants other than SSRIs (venlafaxine and other antidepressants), and one study included samples that were also reported for the same outcome in Kieler (2012). Nine primary articles (Hammad, 2009; Andrade, 2009; Kieler, 2012; Colvin, 2012; Huybrechts, 205; Nörby, 2016; Bérard, 2017; Chambers, 2006; Wilson, 2011)) with only SSRI exposure not reported in another article were included (n=6,201,922).

Grigoriadis (2013) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis with the aim to evaluate the association between prenatal antidepressant exposure and poor neonatal adaptation syndrome (PNAS). Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, EMBASE, Scopus were searched up to June 30, 2010, cohort and case-control studies published in English reporting original data on neonatal effects following prenatal exposure to any antidepressant were included if they reported effect size or sufficient data to calculate an effect size. Abstracts, conference proceedings, and unpublished data were not included. Of the primary articles included in the review (n=12), two articles (Costei, 2002; Laine, 2003) with only SSRI exposure were included in this guideline (n=122).

McDonagh (2014) performed a systematic review to evaluate the benefits and harms of pharmacological therapy for depression in women during pregnancy or the postpartum period. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Scientific Information Packets from pharmaceutical manufacturers were searched up to July 2013 for studies reporting results from pregnant women and women during the first 12 months after delivery, who received treatment for a depressive episode, either meeting DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder or with depressive symptoms that received clinical attention. They excluded reports on bipolar depression, psychotic depression, mood disorders secondary to a general medical condition, and mood disorders secondary to substance abuse (DSM-IV criteria). Of the primary articles included in the review with neonatal mortality as outcome, three articles reported mortality in the first year and were excluded, two articles (Jimenez-Solem, 2013; Stephansson, 2013) reported neonatal mortality up to 28 days after birth as outcome and were included in this guideline (n=2,577,697).

Studies from current guideline (published October 2012):

Heikkinen (2002) conducted a case control study in a hospital maternity unit in Finland. They included 21 pregnant women. They compared mean 5-minute Apgar score, mean umbilical cord pH, and mean birthweight between children born to mothers with depression or panic disorder exposed to citalopram during pregnancy (median 20mg per day) and women who took no medications during pregnancy. They did not report if the control group had any psychiatric disorders.

Sivojelezova (2005) conducted a prospective case control study derived from the Canadian Motherisk program, using data on women who gave birth between 1999 and 2002 (n=221 ). They compared rate of NICU admission in children born to mothers with depression exposed to citalopram in the third trimester to children to unexposed mothers without depression.

Toh (2009) conducted a multicentre case control study in the US. They included women who participated in the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study between 1998 and 2008 study (n=5902). They compared rate of SGA in children born to mothers who used SSRIs from 2 months before conception through at least the first trimester, with children born to mothers who did not use SSRIs during pregnancy.

Wen (2006) conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the Saskatchewan Health databases in Canada. They included women who gave birth between 1990 and 2000 (n=972). They compared rate of low birthweight (< 2500g) and PNAS (seizures) between children born to mothers with at least one SSRI prescription dispensed in the 1-year period before delivery with children born to mothers with no SSRI prescriptions, with or without depression.

From new search (February 2019):

Altamura (2013) conducted a case control study in a hospital in Italy. They included pregnant women with major depressive disorder who received a prescription for SSRIs during their first visit and compared them to a control group without major depressive disorder who were not prescribed SSRIs (total n=56). Outcomes were mean Apgar score, mean birthweight, and rate of NICU admissions.

Bakaysa (2016) conducted a retrospective cohort study in the US . They included women who gave birth in a tertiary care center (not further specified) between 2009 and 2014, who reported SSRI use on admission and matched controls who did not report SSRI use in admission (total n=336). Outcomes were Apgar score below 7 after 1 and 5 minutes.

Klieger-Grossmann (2012) conducted a prospective multicentre cohort study in Canada, Switzerland, and Italy. They included women exposed to Escitalopram during pregnancy, and a control group with non-teratogenic exposures (total n=637). Outcomes were rate of NICU admission, low birthweight (< 2500g), and mean birthweight.

Sujan (2017) conducted a retrospective cohort study using Swedish registry data. They included women who gave birth in Sweden between 1996 and 2012 (n=1,580,629). They compared the rate of SGA among children born to mothers exposed to SSRIs in the first trimester to children born to mothers without SSRI exposure.

Results

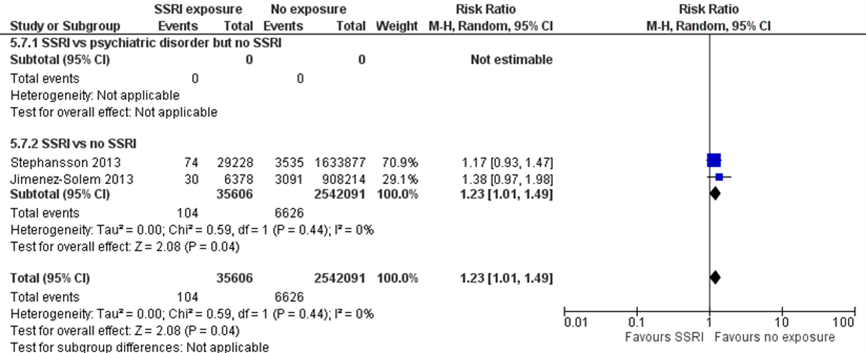

Neonatal mortality within 28 days of birth (critical outcome)

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with women with depression unexposed to SSRIs

No studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women with depression reported on the outcome measure mortality within 28 days of birth.

Studies comparing women exposed to SSRIs with women unexposed to SSRIs

Jimenez-Solem (2013) and Stephansson (2013), both included in the systematic review by McDonagh (2014), reported the rate of neonatal mortality within 28 days of birth. Jimenez-Solem (2013) found that children with prenatal exposure to SSRIs had a 38% higher risk of dying within 28 days of birth (RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.98). This difference translates into a number needed-to-harm (NNH) of -773, which does not fulfil the threshold for a clinically relevant effect on mortality as defined by the working group (NNH > -100; see the section ‘Search and select’) and is therefore likely not clinically relevant. Furthermore, the effect estimate was broad (95% CI 9794 to -300), resulting in serious imprecision.

Stephansson (2013) found that children with prenatal exposure to SSRIs had a 38% higher risk of dying within 28 days of birth (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.47). This difference translates into a number needed-to-harm (NNH) of -2719, which does not fulfil the threshold for a clinically relevant effect on mortality as defined by the working group (NNH > -100; see the section ‘Search and select’) and is therefore likely not clinically relevant. Here, the effect estimate was also broad (95% CI 6603 to -983), resulting in serious imprecision. Overall, the results from Jimenez-Solem (2013) and Stephansson (2013) do not provide evidence of a clinically important increase in risk of neonatal mortality following prenatal exposure to SSRIs. The overall absolute risk of mortality was 0.3% among both exposed and unexposed infants. Both studies compared SSRI exposure in depressed women to women who were not exposed to SSRIs and also were not depressed, resulting in indirectness.

Figure 1.1 Neonatal mortality

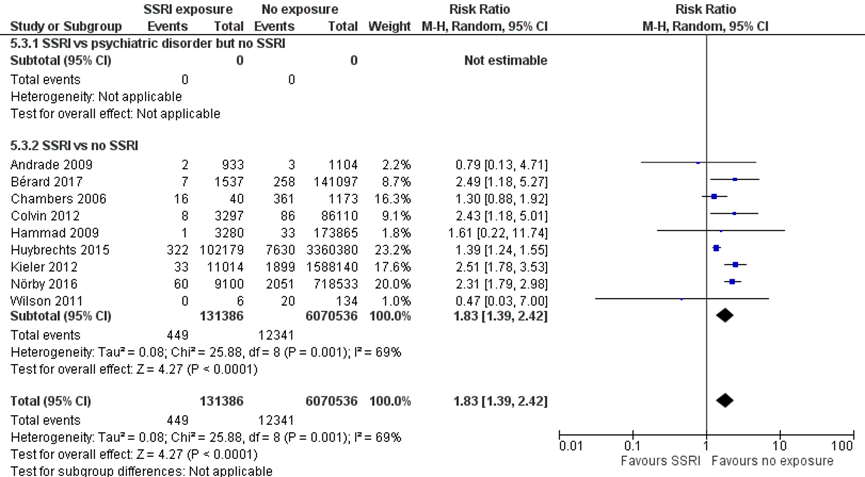

Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension (PPHN) (important outcome)

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with women with depression unexposed to SSRIs

No studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women with depression reported on the outcome measure PPHN.

Studies comparing women exposed to SSRIs with women unexposed to SSRIs

Nine studies comparing children exposed to SSRIs to unexposed children reported results on the outcome PPHN (Andrade, 2009; Bérard, 2017; Chambers, 2006; Colvin, 2012; Hammad, 2009; Huybrechts, 2015; Kieler, 2012; Nörby, 2016; Wilson, 2011). The pooled estimate showed an 83% higher risk of PPHN after SSRI exposure (RR1.83, 95% CI 1.39 to 2.42). This difference translates into a number needed-to-harm (NNH) of -726 (95% CI 885 to 616), which does not fulfil the threshold for a clinically relevant effect on the risk of PPHN as defined by the working group (NNH > -100; see the section ‘Search and select’) and is therefore likely not clinically relevant. The overall absolute risk of PPHN was 0.3% among both exposed infants and 0.2% among unexposed infants, with an absolute risk difference of 0.1%. All studies compared SSRI exposure in depressed women to women who were not exposed to SSRIs and also were not depressed, resulting in indirectness.

Figure 1.2 PPHN

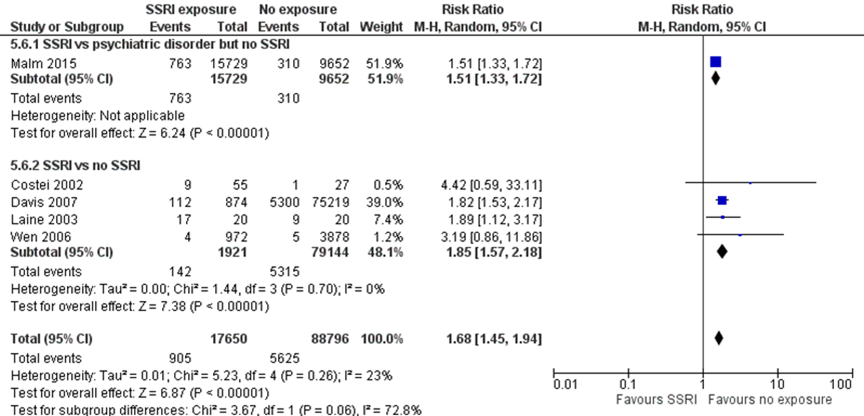

Poor Neonatal Adaptation Syndrome (PNAS) (important outcome)

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with women with depression unexposed to SSRIs

No studies reported the risk of PNAS ) in children born to mothers with depression exposed to SSRIs as compared with children of unexposed women with depression. One study (Malm, 2015) reported a 51% higher risk of breathing problems (one symptom of PNAS) (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.72) in children born to mothers with depression exposed to SSRIs as compared with children of unexposed women with depression. This difference fulfils the threshold for a clinically important effect on the outcome PNAS as defined by the working group (a 25 % difference in relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes; see the section ‘Search and select’) and is therefore likely clinically relevant. Data were derived from registry data without blinding of outcome assessment, which could introduce bias.

Studies comparing women exposed to SSRIs with women unexposed to SSRIs

Four studies comparing children exposed to SSRIs to unexposed children reported results on aspects of the outcome PNAS (Costei, 2002, respiratory distress; Davis, 2007, respiratory distress; Laine, 2003, serotonergic symptoms; Wen, 2006, seizures). The pooled data showed an 85% higher risk of PNAS after SSRI exposure (RR 1.85, 95% CI 1.57 to 2.18), a clinically relevant effect.

The overall pooled estimate showed a 68% higher risk of PNAS (RR 1.68, 95% CI 1.45 to 1.94) in children exposed to SSRIs. This difference fulfils the threshold for a clinically important effect on the outcome PNAS as defined by the working group and is likely clinically important.

Figure 1.3 PNAS

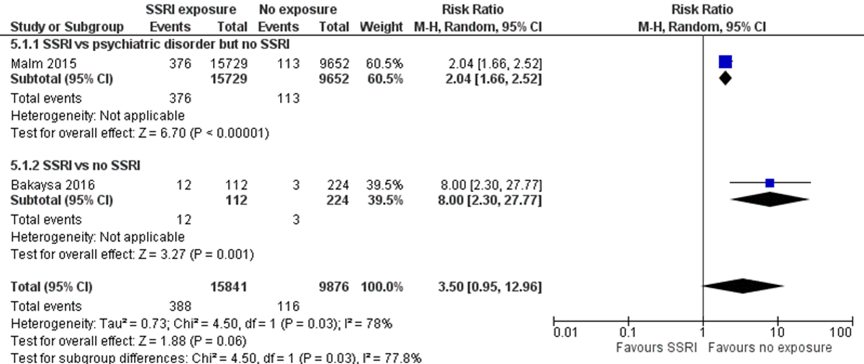

5 minute Apgar score < 7 (important outcome)

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with women with depression unexposed to SSRIs

Malm (2015) reported an 104% higher risk of a 5 minute Apgar score below 7 (RR 2.04, 95% CI 1.66 to 2.52) in children born to mothers with depression exposed to SSRIs as compared with children of unexposed women with depression. This difference fulfils the threshold for a clinically important effect on the outcome 5 minute Apgar score < 7 as defined by the working group (a 25 % difference in relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes; see the section ‘Search and select’) and is therefore likely clinically relevant. However, data were derived from registry data without blinding of outcome assessment, which could introduce bias.

Studies comparing women exposed to SSRIs with women unexposed to SSRIs

Bakaysa (2016) reported an 800% higher risk of a 5 minute Apgar score below 7 (RR 8.00, 95% CI 2.30-27.77) in children with prenatal exposure to SSRIs. This difference fulfils the threshold for a clinically important effect on the outcome 5 minute Apgar score < 7 as defined by the working group and is likely clinically relevant. However, the effect estimate was very broad, resulting in imprecision.

The overall pooled estimate showed a 350% higher risk of 5 minute Apgar score < 7 (RR 3.50, 95% CI 0.95-27.77) in children exposed to SSRIs. This difference fulfils the threshold for a clinically important effect on the outcome 5 minute Apgar score below 7 as defined by the working group and is likely clinically important. However, the effect estimate is very broad, covering both a small decrease in a risk and a very large increase in risk, resulting in serious imprecision.

Figure 1.4 5 minute Apgar score < 7

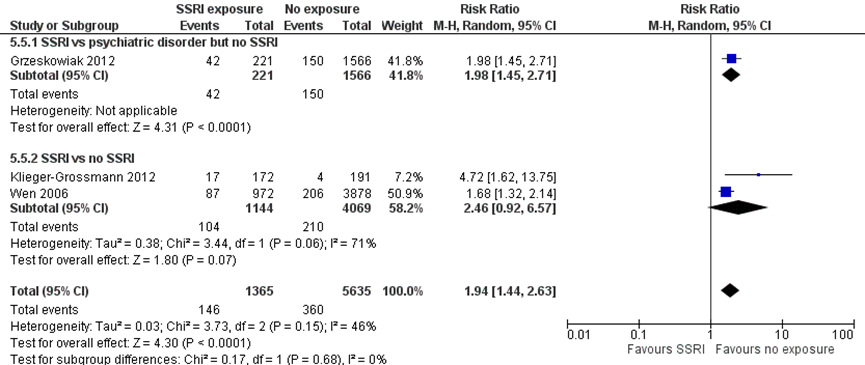

Low birthweight (< 2500 g) (important outcome)

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with women with depression unexposed to SSRIs

Grzeskowiak (2012) reported a 98% higher risk of unadjusted low birthweight (RR 1.98, 95% CI 1.45 to 2.71) in children born to mothers with depression exposed to SSRIs as compared with children of unexposed women with depression. This difference fulfils the threshold for a clinically important effect on the outcome low birthweight as defined by the working group (a 25 % difference in relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes; see the section ‘Search and select’) and is therefore likely clinically relevant.

Studies comparing women exposed to SSRIs with women unexposed to SSRIs

Two studies comparing children exposed to SSRIs to unexposed children reported results on the outcome unadjusted low birthweight (Klieger-Grossmann, 2012; Wen, 2006). The pooled data showed 246% higher risk of low birthweight after SSRI exposure (RR 2.46, 95% CI 0.92 to 6.57), a clinically relevant effect. Comparing SSRI exposure in depressed women to women who were not exposed to SSRIs and also were not depressed results in indirectness.

The overall pooled estimate showed a 94% higher risk of low birthweight (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.44 to 2.63) in children exposed to SSRIs. This difference fulfils the threshold for a clinically important effect on the outcome low birthweight as defined by the working group and is likely clinically important. However, birthweights were unadjusted for prematurity, resulting in risk of bias.

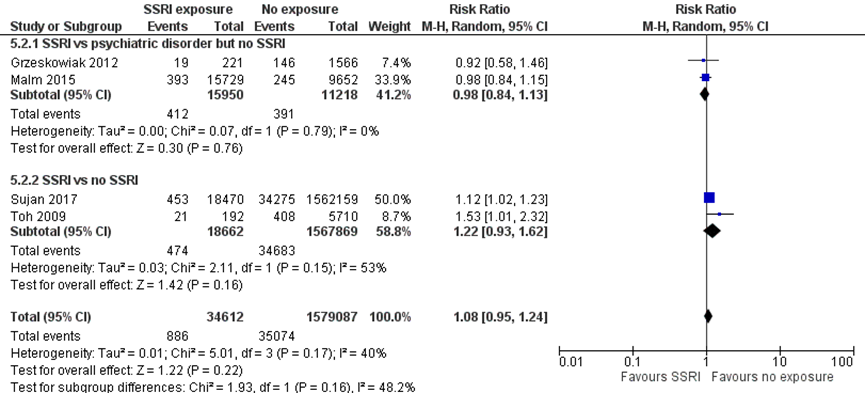

Small for gestational age (SGA) (important outcome)

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with women with depression unexposed to SSRIs

Two studies (Grzeskowiak, 2012; Malm, 2015) comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women with depression reported the outcome SGA. The pooled effect showed a 2% lower risk of SGA in children exposed to SSRIs (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.13). The difference does not fulfil the threshold of a clinically important effect, however the effect estimate overlaps an effect that is not deemed relevant.

Studies comparing women exposed to SSRIs with women unexposed to SSRIs

Two studies (Sujan, 2017; Toh, 2009) comparing SSRI exposure to no exposure reported the outcome SGA. The pooled effect estimate showed a 22% higher risk of SGA in children exposed to SSRIs. This difference does not fulfil the threshold of a clinically important effect. Furthermore, the effect estimate was broad and covered both a small risk reduction and a clinically relevant risk increase, resulting in serious imprecision.

The overall pooled estimate showed an 8% higher risk of low SGA (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.24) in children exposed to SSRIs. This difference does not fulfil the threshold for a clinically important effect on the outcome SGA as defined by the working group. Further, the overall confidence interval overlaps both an increased and decreased risk of SGA, resulting in imprecision.

Figure 1.6 SGA

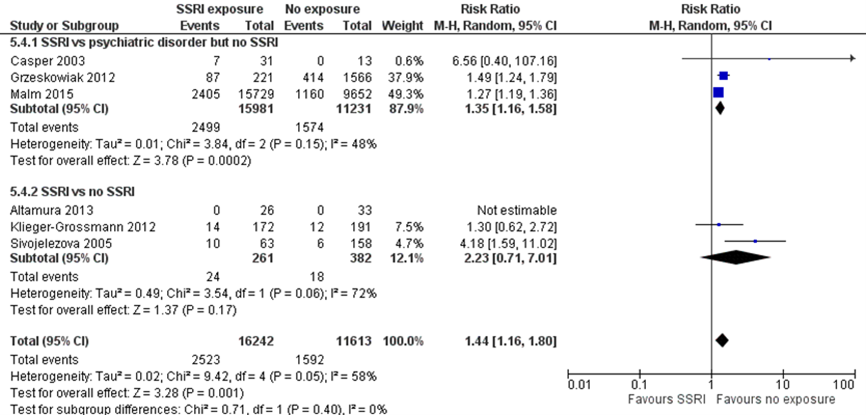

NICU admission (important outcome)

Studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with women with depression unexposed to SSRIs

Rate of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission was reported in three studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women with depression (Casper, 2003; Grzeskowiak, 2012; Malm, 2015). NICU was not further specified. The pooled effect showed a 35% higher risk of NICU admission in children exposed to SSRIs (RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.58). The difference fulfils the threshold of a clinically important effect, however the effect estimate overlaps an effect that is not deemed relevant, resulting in imprecision.

Studies comparing women exposed to SSRIs with women unexposed to SSRIs

Rate of NICU admission was reported in three studies comparing SSRI exposure to no exposure (Altamura, 2013; Klieger-Grossmann, 2012; Sivojelezova, 2005). The pooled effect showed a 223% higher risk of NICU admission in infants exposed to SSRIs. The difference fulfils the threshold of a clinically important effect, however the effect estimate overlaps a clinically important increase as well as a clinically important decrease in risk, resulting in serious imprecision.

When all six studies were pooled, the exposed children had a 44% higher risk of NICU admission, a clinically important difference. However, the effect estimate overlaps an effect that may not be clinically relevant, resulting in imprecision.

Figure 1.7 NICU admission

Non-NICU admission

No studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women with or without depression reported on the outcome measure non-NICU admission.

Umbilical artery pH

No studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women with depression reported on the outcome measure umbilical cord pH.

Heikkinen (2002) reported a mean umbilical artery pH of 7.27 (range 7.15;7.40) in children who were exposed to SSRIs during pregnancy and 7.33 (range 7.22;7.47) in unexposed children. The difference was not statistically significant (p=.22 and is probably not of clinical importance. Furthermore, the study was very small (total n=21) and does not provide convincing evidence of either the presence or the absence of an effect on umbilical cord pH from prenatal exposure to SSRIs.

Prolonged QT c-interval

No studies comparing women with depression exposed to SSRIs with unexposed women with or without depression reported on the outcome measure prolonged QT c-interval.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure PPHN started at LOW (observational data) and was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias due to indirectness.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure PNAS started at LOW (observational data) and was not downgraded.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neonatal mortality within 28 days of birth started at LOW (observational data) and was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias due to indirectness.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 5 minute Apgar score < 7 started at LOW (observational data) and was downgraded by 1 level because of imprecision.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure Low birthweight (< 2500 g) started at LOW (observational data) and was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias due to risk of bias (birthweight unadjusted for prematurity).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure Small for gestational age (SGA) started at LOW (observational data) and was downgraded by 1 level because of risk of bias due to imprecision.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure NICU-admission started at LOW (observational data) and was downgraded by 1 level because of imprecision.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures non-NICU admission, umbilical cord pH, and prolonged QT c-interval could not be graded due to a lack of research data.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

P: patients pregnant women;

I: intervention exposure to SSRIs during pregnancy;

C: control no exposure to SSRIs during pregnancy;

O: outcome measures neonatal mortality (Neonatal mortality within 28 days of birth), child safety postpartum (neonatal symptoms up to 7 days postpartum: Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension (PPHN), 5 minute Apgar score < 7, Low birthweight (< 2500 g), Small for gestational age (SGA)), neonatal adaptation (Poor Neonatal Adaptation Syndrome (PNAS)), NICU admission.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered neonatal mortality as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and all other outcome measures as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

For the hard outcome measure neonatal mortality and Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension (PPHN), the working group defined a number needed to harm (NNH) of 100 as the threshold for clinical decision making. For all other outcome measures, the default thresholds proposed by the international GRADE working group were used: a 25 % difference in relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes, and 0.5 standard deviations (SD) for continuous outcomes.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2011 until December 5, 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 400 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: (systematic reviews of) studies comparing pregnant women exposed to SSRI’s to unexposed pregnant women. Twenty-six studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 14 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 12 studies were included. Furthermore, 4 studies were included from the national guideline published in October 2012.

Results

Fifteen studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Altamura, A. C., De Gaspari, I. F., Rovera, C., Colombo, E. M., Mauri, M. C., & Fedele, L. (2013). Safety of SSRIs during pregnancy: a controlled study. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 28(1), 25-28.

- Bakaysa, S. L., Kelly, J., & Urato, A. (2016). Does SSRI antidepressant use influence APGAR scores?[29N]. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127, 122S.

- Casper, R. C., Fleisher, B. E., Lee-Ancajas, J. C., Gilles, A., Gaylor, E., DeBattista, A., & Hoyme, H. E. (2003). Follow-up of children of depressed mothers exposed or not exposed to antidepressant drugs during pregnancy. The Journal of pediatrics, 142(4), 402-408.

- Grigoriadis, S., VonderPorten, E. H., Mamisashvili, L., Eady, A., Tomlinson, G., Dennis, C. L., ... & Cheung, A. (2013). The effect of prenatal antidepressant exposure on neonatal adaptation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 74(4), 309-320.

- Grzeskowiak, L. E., Gilbert, A. L., & Morrison, J. L. (2012). Neonatal outcomes after late-gestation exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 32(5), 615-621.

- Heikkinen, T., Ekblad, U., Kero, P., Ekblad, S., & Laine, K. (2002). Citalopram in pregnancy and lactation. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 72(2), 184-191.

- Huybrechts, K. F., Bateman, B. T., Palmsten, K., Desai, R. J., Patorno, E., Gopalakrishnan, C., ... & Hernandez-Diaz, S. (2015). Antidepressant use late in pregnancy and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Jama, 313(21), 2142-2151.

- Kieviet, N., Van Ravenhorst, M., Dolman, K. M., Van De Ven, P. M., Heres, M., Wennink, H., & Honig, A. (2015). Adapted Finnegan scoring list for observation of anti-depressant exposed infants. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 28(17), 2010-2014.

- Klieger‐Grossmann, C., Weitzner, B., Panchaud, A., Pistelli, A., Einarson, T., Koren, G., & Einarson, A. (2012). Pregnancy outcomes following use of escitalopram: a prospective comparative cohort study. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 52(5), 766-770.

- Malm, H., Sourander, A., Gissler, M., Gyllenberg, D., Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S., McKeague, I. W., ... & Brown, A. S. (2015). Pregnancy complications following prenatal exposure to SSRIs or maternal psychiatric disorders: results from population-based national register data. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(12), 1224-1232.

- Masarwa, R., Bar-Oz, B., Gorelik, E., Reif, S., Perlman, A., & Matok, I. (2019). Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and risk for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and network meta-analysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 220(1), 57-e1.

- McDonagh, M., Matthews, A., Phillipi, C., Romm, J., Peterson, K., Thakurta, S., & Guise, J. M. (2014). Antidepressant Treatment of Depression During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Evidence report/technology assessment, (216), 1-308.

- Moses-Kolko, E. L., Bogen, D., Perel, J., Bregar, A., Uhl, K., Levin, B., & Wisner, K. L. (2005). Neonatal signs after late in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: literature review and implications for clinical applications. Jama, 293(19), 2372-2383.

- Silvani, P., & Camporesi, A. (2007). Drug-induced pulmonary hypertension in newborns: a review. Current Vascular Pharmacology, 5(2), 129-133.

- Sivojelezova, A., Shuhaiber, S., Sarkissian, L., Einarson, A., & Koren, G. (2005). Citalopram use in pregnancy: prospective comparative evaluation of pregnancy and fetal outcome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 193(6), 2004-2009.

- Sujan, A. C., Rickert, M. E., Öberg, A. S., Quinn, P. D., Hernández-Díaz, S., Almqvist, C., ... & D’Onofrio, B. M. (2017). Associations of maternal antidepressant use during the first trimester of pregnancy with preterm birth, small for gestational age, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. Jama, 317(15), 1553-1562.

- Toh, S., Mitchell, A. A., Louik, C., Werler, M. M., Chambers, C. D., & Hernández-Díaz, S. (2009). Antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery and fetal growth restriction. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology, 29(6), 555.

- Ulbrich, K. A., Zumpf, K., Ciolino, J. D., Shah, M., Miller, E. S., & Wisner, K. L. (2021). Acute Delivery Room Resuscitation of Neonates Exposed to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. The Journal of Pediatrics, 232, 103-108.

- Viktorin, A., Lichtenstein, P., Lundholm, C., Almqvist, C., D’Onofrio, B. M., Larsson, H., ... & Magnusson, P. K. (2016). Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor use during pregnancy: association with offspring birth size and gestational age. International journal of epidemiology, 45(1), 170-177.

- Wen, S. W., Yang, Q., Garner, P., Fraser, W., Olatunbosun, O., Nimrod, C., & Walker, M. (2006). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse pregnancy outcomes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 194(4), 961-966.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Grigoriadis, 2013 |

SR and meta-analysis of [RCTs / cohort / case-control studies]

Literature search up to June 2010

A: Costei, 2002 B: Laine, 2003

Study design: cohort [prospective & retrospective], case-control

Setting and Country: Women’s mood and anxiety clinic, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Canada

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: [commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship]

Funded by Research synthesis grant from the CIHR (KRS-83127), Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care through the Drug Innovation Fund (2008-0005), CIHR and Ontario Women’s Health Council (NOW-88207 and NOW-84656).

Grigoriadis: honoraria as consultant or for lectures: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Servier, Eli Lilly Canada, Lundbeck, research support from CIHR, Ontario Ministry of Health, Ontario Mental Health Foundation, CR Younger Foundation. Steiner: consultant to AstraZeneca, Azevan, Servier, Bayer Canada, Lundbeck, research support from CIHR, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Society for Women’s Health Research, AstraZeneca. No other conflicts of interest reported. |

Inclusion criteria SR: - Cohort and case-control studies - Published in English - Original data - Neonatal effects following any antidepressant exposure - Sufficient data to calculate effect size (if not reported)

Exclusion criteria SR: - Abstracts - Conference proceedings - Unpublished data (no search)

12 studies included (2 met criteria for this review)

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: 55 case and 27 controls, age not reported B: 20 cases and 20 controls, age not reported

Sex: A: 0 % Male B: 0 % Male

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: Paroxetine (SSRI) B: SSRIs

|

Describe control:

A: Nonteratogenic exposure, matched for maternal age, gravidity, parity, alcohol use, smoking, nonteratogenic drug use B: No SSRIs, cases and controls matched for maternal age, gravidity, parity, pregnancy duration, time of delivery, delivery mode

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: Birth/neonatal control B: Birth/neonatal control

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: Not reported (retrospective) B: Not reported (retrospective)

|

Neonatal Adaptation Syndrome (PNAS) Defined as presence of 1 or more of the following signs: tremors or shaking, jitteriness, shivering, agitation, irritability, increased or decreased muscle tone, poor feeding, excessive weight loss, seizures, tachypnea or respiratory distress.

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95% CI]: A: RR 4.42 [0.59, 33.11] (OR from SR 7.26 [0.89-59.09]) B: RR 1.89 [1.12, 3.17] (OR from SR 6.93 [1.53-31.38])

|

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained (subgroupanalysis) |

|

Masarwa, 2019 |

SR and meta-analysis of cohort / case-control studies

Literature search up to July 2017

A: Hammad, 2009 B: Andrade, 2009 C: Kieler, 2012 D: Colvin, 2012 E: Huybrechts, 2015 F: Nörby, 2016 G: Bérard, 2017 H: Chambers, 2006

I: Wilson, 2011

Study design: cohort [retrospective], case-control

Setting and Country: University, Israel

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: [commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship]

Funding not reported.

The authors report no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria SR: - Manuscripts and abstracts - Cohort and case-control studies - Outcome PPHN - Prenatal exposure to SSRIs or SNRIs - Reporting RR or

Exclusion criteria SR: - Studies already reported in more recent publication - Cross-sectional studies, case reports, case series, guidelines, expert opinions, editorials, letters to the editor, comments

11 studies included (9 in current review)

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: XX patients, XX yrs B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I: J: K:

Sex: A: % Male B: C: ….

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: SSRIs B: Second and third trimesters: SSRIs C: Second and third trimesters: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram D: All trimesters: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine E: Second and third trimesters: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine F: Second and third trimesters G: Second and third trimesters: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, fluvoxamine H: Second and third trimesters: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline I:

|

Describe control:

A: Not exposed B: Not exposed C: Not exposed D: Not exposed E: Not exposed F: Not exposed G: Not exposed H: Not exposed I:

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: XX days/months/years B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) Retrospective studies A: B: C: D: E: F: G: H: I:

|

Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of the new-born (PPHN) Defined as.....

Effect measure: RR [95% CI], SSRI vs no SSRI:

A: SSRI vs no SSRI RR 0.80 [0.11, 5.86] B: Any SSRI 3rd trimester vs no antidepressant RR 0.79 [0.13, 4.71] C: Exposed vs unexposed RR 2.51 [1.78, 3.53] (Late SSRI vs Unexposed RR 2.46 [1.74, 3.47] Early exposed vs unexposed Early exposed vs Late exposed RR 0.63 [0.39, 1.02]) D: SSRI vs no SSRI RR 2.43 [1.18, 5.01] E: 1.39 [1.24, 1.55] F: 2.31 [1.79, 2.98] G: 2.49 [1.18, 5.27] H: Any SSRI vs no SSRI 1.30 [0.88, 1.92], early SSRI vs no SSRI I: 3.48 [1.44, 8.40] K: SSRI Exposed Late (>20 wks) =6 (PPHN n=0), SSRI Unexposed (>20 wks) =134 (PPHN n=20) …

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): …. [95% CI …to…] favoring …. Heterogeneity (I2):

Outcome measure-2 ....

Outcome measure-3 ....

|

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained (subgroupanalysis) |

|

McDonagh, 2014 |

SR and meta-analysis of [RCTs / cohort / case-control studies]

Literature search up to [month/year]

A: Jimenez-Solem, 2013 B: Stephansson, 2013

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over], cohort [prospective / retrospective], case-control

Setting and Country: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: [commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship]

Report prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services

The authors reported no conflicting affiliations or financial involvement. |

Inclusion criteria SR: - Pregnant women and women during the first 12 months after delivery, who received treatment for a depressive episode, either meeting DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder or with depressive symptoms that received clinical attention Exclusion criteria SR: - Bipolar depression, psychotic depression, mood disorders secondary to a general medical condition, mood disorders secondary to substance abuse (DSM-IV criteria)

5 studies included (2 in current review)

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: XX patients, XX yrs B:

Sex: A: % Male B:

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: XX mg; once/twice daily B:

|

Describe control:

A: placebo; once/twice daily B:

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: XX days/months/years B:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: B:

|

Neonatal mortality Defined as death within 28 days of birth (Table 4)

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95% CI]: A: Any SSRI: 1.27 (0.82 to 1.99) Citalopram: 2.49 (1.33 to 4.65) Escitalopram: 2.07 (0.29 to 14.85) Fluoxetine: 0.63 (0.24 to 1.69) Paroxetine: 1.95 (0.73 to 5.23) Sertraline: 0.26 (0.04 to 1.81) B: Adjusted OR (95% CI) for any SSRI Neonatal death (0-27 days): 1.23 (0.96 to 1.57) from SR, no frequencies

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): …. [95% CI …to…] favoring …. Heterogeneity (I2):

Outcome measure-2 PNAS defined as reported jitteriness, tachypnea, hypoglycemia, hypothermia, poor tone, respiratory distress, weak or absent cry, or desaturation on feeding.

Outcome measure-3 ....

|

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion

Personal remarks on study quality, conclusions, and other issues (potentially) relevant to the research question

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses); mention only analyses which are of potential importance to the research question

Heterogeneity: clinical and statistical heterogeneity; explained versus unexplained (subgroupanalysis) |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy - otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question:

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Current guideline |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Casper 2003 |

Type of study: Case control

Setting and country: Women’s wellness clinic, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding and conflict of interest were not reported |

Inclusion criteria: - Women who met DSM-IV criteria for Major Depressive Disorder during pregnancy - Informed consent

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 44 Intervention: 31 Control: 13

Important prognostic factors2: Age at delivery ± SD: I: 36.6 ± 3.5 C: 34.9 ± 3.8

Sex: I: 0% M C: 0% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): (Major depressive disorder)

SSRI’s during pregnancy. The average daily doses of sertraline, fluoxetine, and paroxetine were 113.2 ± 72.3 mg, 20 ± 11.9 mg, and 17.2 ± 10.1 mg, respectively; 45% of the women took SSRIs throughout the pregnancy, 71% took SSRIs during the first trimester, and 74% took SSRIs during the third trimester. Psychotherapy. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): (Major depressive disorder)

No SSRI, psychotherapy. |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe) |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

NICU admission I: 23% (7 of 31) C: 0% (0 of 13) RR 6.56 (0.40;107.16) |

|

|

Heikkinen 2002

|

Type of study: prospective case control study

Setting and country: maternity unit, hospital, Finland

Funding and conflicts of interest: Drug concentrations analysed by Lundbeck AB |

Inclusion criteria: - pregnant women

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 21 Intervention: 11 Control: 10

Important prognostic factors2: Median age (range): I: 34 (25-42) C:31 (25-37

Sex: I: 0% M C: 0% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): (Depression or panic disorder)

Citalopram, median 20 mg (range 20-40 mg) per day. Indication depression (n=6) or panic disorder (n=5)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): (Psychiatric disorders not reported)

No medication during pregnancy. |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe) |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Apgar 5 minutes, birth weight, only means

Umbilical cord pH I: 7.27 (7.15;7.40) C: 7.33 (7.22;7.47) p=.22

Birth weight, g (SD) I:3.460 (2.830-4.380) C:3.560 (3.220-4.260) p=.62 |

|

|

Sivojelezova 2005 |

Type of study: prospective case-control

Setting and country: Motherisk program, Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: Grant from Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation

Conflicts of interest not reported |

Inclusion criteria: - 1999-2002

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 221 Intervention: 63 Control: 158

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: C: Not reported for women exposed/unexposed to citalopram in the third trimester

Sex: I: 0% M C: 0% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Unclear |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): (depression)

Citalopram in the third trimester

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): (no depression)

No citalopram in the third trimester |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe) |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

NICU admission I: 16% (10 of 63) C: 4% (6 of 158) RR 4.18 [1.59, 11.02] |

|

|

Toh 2009 |

Type of study: case-control study

Setting and country: multi-center study, US, Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: No direct funding.

AM, CL, SH-D received grant R01 HD046595 from the National Institute of Child and Human Development (NICHD). AM has contract support from Gilead Sciences and consulting fees from Merck and Biogen-Idec. MW has served as a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, and Sanofi Aventis. CC has received research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi Aventis, Sanofi Pasteur, Barr Laboratories, Teva, Sandoz, Kali Laboratories, and Apotex. SH-D has served as a consultant to Novartis and AstraZeneca and has received research or training grants from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Wyeth. |

Inclusion criteria: - participant in the Slone Epidemiology Center Birth Defects Study (BDS) between 1998 and 2008

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 5902 Intervention: 192 Control: 5710

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: C:

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test): (Probably with depression)

SSRI use from 2 months before conception through at least the first trimester |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test): (Probably without depression)

No SSRI use during pregnancy |

Length of follow-up: retrospective

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): SGA I: 11% (21 of 192) C: 7% (408 of 5710) RR 1.53 [1.01, 2.32] |

|

|

Wen 2006

|

Type of study: retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Registry study, Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: Grants from The Hospital for Sick Kids Foundation (grant #XG-02-098), research and development Research Allowance from The Canadian Institutes for Health Research (SWW)

Conflicts of interest not reported.

|

Inclusion criteria: - registered in the Saskatchewan Health databases between 1990 and 2000

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 4.850 Intervention: 972 Control: 3.878

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age (y) I: 7% <19, 51% 20-29, 42% ≥30 C: 8% <19, 56% 20-29, 36% ≥30

Sex: I: 0% M C: 0% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Differences in social assistance (I: 23%, C: 12%) |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

At least 1 SSRI prescription that was dispensed in the 1-year period before delivery were selected as the exposed group.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No SSRI prescription (depression status/diagnosis not taken into account) |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available): Low birth weight (<2500g) I: 9% (87 of 972) C: 5% (206 of 3878) RR 1.68 [1.32, 2.14]

Seizures (added to PNAS outcome in revman) I: 0.4% (4 of 972) C: 0.1% (5 of 3878) RR 3.19 [0.86, 11.86] |

|

|

Search 2019 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Altamura, 2013 revman |

Type of study: case control study

Setting and country: Hospital, Italy

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding not mentioned.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: - Pregnant women - Major depressive disorder (DSM-IV TR criteria, assessed in structured interview) in intervention group - No depression in control group

Exclusion criteria: - None

N total at baseline: 56 pregnancies, 59 live births Intervention: 26 Control: 30 pregnancies, 33 live births

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 35.5 ± 4.6 C: 33.2 ± 5.9

Sex: I: 0 % M C: 0 % M

Parity ± SD: I: 1.6 ± 0.8 C: 1.5 ± 0.7

Gravidity ± SD: I: 3.5 ± 0.7 C:2.4 ± 0.4

Substance abuse, %: I: 6% C: 3%

Personality disorder, % I: 48% C: 19%

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

SSRIs prescribed from the first visit (52% first trimester, 19% second trimester and 28% third trimester)

Citalopram 20–30 mg/day (n = 8), escitalopram 10–15 mg/day, (n=2), fluoxetine 20–30 mg/day (n=2), paroxetine 20–40 mg/day (n = 8) and sertraline 50–100mg/day (n=10).

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No SSRI treatment (and no major depressive disorder) |

Length of follow-up: Until conception

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N 0 (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N 0 (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N 0 (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N 0 (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Apgar score

Birth weight

NICU admission

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Apgar score 1 minute I: 9.3 ± 0.5 C: 9.5 ± 0.5 p=.02, F-test

5 minutes I: 9.5 ± 0.5 C: 9.4 ± 0.5 p=.77, F-test

Birth weight, g I: 2961 ± 389 C:2920 ± 246 Not statistically different, p not reported

NICU admission I: 0 of 26 C: 0 of 33

|

|

|

Bakaysa, 2016 (conference poster) revman |

Type of study: retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Hospital, US

Funding and conflicts of interest: AU was retained as an expert witness in litigation involving SSRIs. The other authors did not report potential conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: - Delivery in a tertiary care center 2009-2014 - SSRI use on admission (matched to controls 2:1 fashion by completed weeks of gestation and mode of delivery)

Exclusion criteria: - Fetal anomalies - Stillbirths - Multiple gestations

N total at baseline: 336 Intervention: 112 Control: 224

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: C:

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

SSRI use reported on admission

Citalopram (n=23), escitalopram (n=4), paroxetine (n=2), fluoxetine (n=34), and sertraline (n=49).

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No SSRI use reported on admission |

Length of follow-up: Retrospective, until conception

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Apgar score

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Apgar score <7 at 1 minute, % I: 24% C: 14% OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.1-3.5, p=.02

Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes, % I: 11% of 112 (12) C: 1% of 224 (3) OR 8.8, 95% CI 2.4-32.0, p=.0009 |

|

|

Grzeskowiak, 2012 (revman) |

Type of study: retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: registry study, Australia

Funding and conflicts of interest: JM supported by a Heart Foundation South Australian Cardiovascular Research Network Fellowship (CR10A4988).

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: - Singleton live births

Exclusion criteria: - antidepressants other than SSRI - antipsychotics

N total at baseline: 33.965 Intervention: 221 Control 1: 1.566 Control 2: 32.004

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 29.5 ± 5.9 C1: 28.5 ± 6.2 C2: 29.2 ± 5.8

Sex: I: 0 % M C1: 0 % M C2: 0 % M

Parity, n (%): I: 69 (32%) C1: 692 (44%) C2: 14.098 (44%)

Socioeconomic status, n (%) highest I: 42 (19%) C1: 296 (19%) C2: 6264 (20%)

Non-smoker, n (%) I: 141 (66%) C1: 983 (65%) C2: 25.647 (84%)

Anxiolytic use, n (%) I: 28 (12.7%) C1: 41 (2.6%) C2: 189 (0.6%)

Substance use, n (%) I: 21 (9.5) C1: 152 (9.7) C2: 808 (2.5)

Alcohol abuse, n (%) I: 4 (1.8) C1: 28 (1.8) C2: 101 (0.3)

Groups comparable at baseline? Differences in anxiolytic use (more in I), smoking (less in C2), parity (less in I)

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Dispensing of SSRI during pregnancy (pharmacy record)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

C1: Women with psychiatric illness but no SSRI

C2: No psychiatric illness, no SSRI |

Length of follow-up: Until discharge from hospital

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Low birth weight <2500 g

SGA Defined as percentage of optimal birth weight (POBW) below the 10th percentile

NICU admission (neonate admission to hospital)

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Low birth weight I: 42 of 221 (19.0%) C1: 150 of 1566 (9.6%) C2: 2734 of 32.004 (8.6%) I vs C1 adj OR 2.26 (1.31;3.91) I vs C2 adj OR 2.57 (1.57;4.21) [C1 vs C2 adj OR 1.05 (0.83;1.34)]

SGA I: 19 of 221 (12.8%) C1: 146 of 1566 (13.0%) C2: 2205 of 32.004 (9.8%) I vs C1 adj OR 1.13 (0.65;1.94) I vs C2 adj OR 1.17 (0.71;1.94) [C1 vs C2 adj OR 1.06 (0.88;1.28)]

NICU admission I: 87 of 221 (39.4%) C1: 414 of 1566 (26.4%) C2: 6114 of 32.004 (19.1%) I vs C1 adj OR 1.92 (1.39;2.65) I vs C2 adj OR 2.37 (1.76;3.19) [C1 vs C2 adj OR 1.21 (1.07;1.38)]

Odds ratios adjusted for maternal age, socioeconomic status, smoking status, race, asthma, pre-existing diabetes, alcohol abuse, substance abuse, hypertension, parity, epilepsy, thyroid disorder, and anxiolytic use. |

|

|

Klieger-Grossmann, 2012 revman |

Type of study: prospective cohort

Setting and country: multicenter cohort study, Canada, Switzerland, Italy (The Motherisk Program in Toronto, the Swiss Teratogen Information Service, and the Florence Teratogen Information Service)

Funding and conflicts of interest: A.E.: grant from Eli Lilly Canada to study the safety of Cymbalta during pregnancy. No further mention of funding or conflicts of interest.

|

Inclusion criteria: - exposure to Escilatopram, other antidepressants, or nonteratogenics Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 637 Intervention: 213 (172 live births) Control 1: 212 (167 live births) Control 2: 212 (191 live births)

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: C1: C2: Mean age entire sample: 33.1 ± 2.3 years.

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, C1 and C2 matched to I for age, smoking, and alcohol use |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I: Exposure to Escitalopram during pregnancy

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

C1: exposure to other antidepressants during pregnancy

C2: Nonteratogenic exposure during pregnancy (acetaminophen, antibiotics, antihistamines, etc)

|

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

NICU admission I: 14 of 172 (8.1%) C1: 15 of 167 (9.0%) C2: 12 of 191 (6.3%) p=.989 I vs C2 RR 1.30 [0.62, 2.72]

Low birth weight (<2500 g) I: 17 of 172 (9.9%) C2: 4 of 191 (2.1%) p=.009 I vs C2 RR 4.72 [1.62, 13.75]

Birth weight I: 3198 ± 594 C2: 3458 ± 540 p<.001

|

|

|

Malm, 2015 revman |

Type of study: registry study

Setting and country: national Medical Birth Register, Finland

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: - all singleton live births in Finland between Jan. 1, 1996, and Dec. 31, 2010

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 15.729 Control 1: 9.652 Control 2: 31.394

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: C:

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I: All women who purchased SSRIs (ATC code N06AB, including fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, and escitalopram) during the period from 30 days before the beginning of gestation until the end of pregnancy were considered exposed.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

C1: Any diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder related to SSRI use from 1 year before the beginning of gestation until discharge (≤3 weeks) from hospital after delivery but no purchases of antidepressants or antipsychotics from 3 months before the beginning of gestation until delivery.

C2: No purchases of antidepressants or antipsychotics and no psychiatric diagnoses related to SSRI use at any time prior to or during pregnancy. |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Small for gestational age I: 393 of 15.729 (2.5%) C1: 245 of 9.652 (2.5%) C2: 673 of 31.394 (2.2%) I vs C1 RR 0.98 [0.84, 1.15] I vs C2 RR 1.17 [1.03, 1.32]

5-minute Apgar score <7 I: 376 of 15.729 (3.9%) C1: 113 of 9.652 (2.3%) C2: 383 of 31.394 (2.1%) I vs C1 RR 2.04 [1.66, 2.52] I vs C2 RR 2.66 [2.28, 3.10]

NICU Neonatal care unit monitoring I: 2405 of 15729 (15.3%) C1: 1160 of 9652 (12%) C2: 3002 of 31394 (9.7%) I vs C1 RR 1.27 [1.19, 1.36] I vs C2 RR 1.60 [1.52, 1.68]

PNAS (breathing problems) I: 763 of 15729 (4.9%) C1: 310 of 9652 (3.2%) C2: 874 of 31394 2.8%) I vs C1 RR 1.51 [1.33, 1.72] I vs C2 RR 1.78 [1.61, 1.97] |

|

|

Sujan, 2017 revman |

Type of study: retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Registry study, Sweden

Funding and conflicts of interest: National Institute of Mental Health of the NIH T32MH103213 and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the NIH K99DA040727, National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship [1342962], Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute: Pediatric Project Development Team, the Swedish Initiative for Research on Microdata in the Social and Medical Sciences (SIMSAM) framework [340-2013-5867], the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE) [50623213], and the Swedish Research Council [2014-38313831].

All other [sic] authors declared no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: - Delivery between 1996 and 2012

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: 1.580.629 Intervention: 18.470 Control: 1.562.159

Important prognostic factors2: Maternal age at birth, I/C <20: 2%/2% 20-24: 12%/13% 25-29: 28%/31% 30-34: 33%/34% 35-39: 21%/16% ≥40: 5%/3%

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

SSRI exposure during 1st trimester

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No SSRI exposure (not further defined) |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Retrospective study |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

SSRI 1st trimester Small for gestational age I: 453 of 18.470 (2.5%) C: 34275 of 1562159 (2.2%) RR 1.12 [1.02, 1.23] Adj OR 1.13 (95% CI 1.03-1.23)

OR adjusted for parity and year of birth and maternal and paternal country of birth, age at childbearing, highest level of completed education, history of any criminal convictions, history of severe psychiatric problems, and history of any suicide attempts |

|

|

Viktorin, 2016 |

Type of study: registry study

Setting and country: Registry study, Sweden

Funding and conflicts of interest: the Swedish Research Council through the Swedish Initiative for research on Microdata in the Social And Medical Sciences (SIMSAM) framework [340-2013-5867]; the Swedish Medical Research Council [K2014-62X-14647-12-51 and K2010-61P-21568-01-4]; the Swedish foundation for Strategic Research; and the Swedish Brain foundation. Conflict of interest: H.L. served as a speaker for Eli Lilly and has received a research grant from Shire, both outside the submitted work. M.L. declares that, over the past 36 months, he has received lecture honoraria from Biophausia, Servier Sweden and AstraZeneca, and served on advisory board for Lundbeck pharmaceuticals. |

Inclusion criteria: - All children born in Sweden between 1 April 2006 and 31 December 2009

Exclusion criteria: - Stillbirths - Twins

N total at baseline: Intervention: Control:

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: C:

Sex: I: % M C: % M

Groups comparable at baseline?

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

I: SSRI exposure (more than one dispensation between conception and delivery, or one dispensation within the pregnancy period and at least one more dispensation within 6 months before or after the dispensation during pregnancy)

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

C1: No SSRI exposure (no dispensations from 3 weeks before pregnancy to delivery)

C2: Depression without SSRI exposure |

Length of follow-up:

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Retrospective cohort |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Birth Weight SSRI I Exposure -.01 (95% CI -0.04;0.02) vs reference group C1 C2 Depression without SSRI exposure .03 (95% CI -0.026;0.01) vs reference group C1

The outcome variable is a standardized value adjusted for gestational age (see Methods). Standardized values for birth weight, birth length, and birth head circumference above or below five standard deviations from the sample mean (N=465) were considered outliers and excluded from the analyses. |

|

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Bromley 2012 |

Narrative review |

|

Byatt 2013 |

does not conform to PICO (wrong outcome) |

|

Casper 2011 |

Does not conform to PICO (wrong drug) |

|

Corti 2019 |

Does not conform to PICO (wrong drug) |

|

Fenger-Gron 2011 |

does not conform to PICO (wrong outcome) |

|

Gentile 2011 |

does not conform to PICO (wrong outcome) |

|

Jensen 2013 |

does not conform to PICO (wrong outcome) |

|

Malm 2012 |

does not conform to PICO (wrong outcome) |

|

Michielsen 2014 |

Does not conform to PICO (wrong drug) |

|

Nezvalova-Henriksen 2017 |

does not conform to PICO (wrong outcome) |

|

Ogunyemi 2018 |

Does not conform to PICO (wrong drug) |

|

Smith 2013 |

Does not conform to PICO (wrong drug) |

|

Sparla 2017 |

Does not conform to PICO (wrong drug) |

|

Viktorin 2016 |

does not conform to PICO (wrong outcome) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 23-01-2023

Geldigheid en Onderhoud

|

Module |

Regiehouder(s) |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling |

|

1 |

NVOG |

2022 |

2027 |

5 jaar |

NVOG |

|

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Samenstelling werkgroep