Behandeling sinus pilonidalis

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale behandeling voor symptomatische sinus pilonidalis?

Deze uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvragen:

- Wat is de plaats van minimale invasieve technieken bij patiënten met een symptomatische sinus pilonidalis?

- Wat is de plaats van sluiting middels verschuivingsplastieken bij patiënten met een symptomatische sinus pilonidalis?

Aanbeveling

Verricht geen chirurgische behandeling voor een asymptomatische sinus pilonidalis.

Overweeg bij patiënten met een simpele symptomatische sinus pilonidalis een minimaal invasieve behandeling als eerste modaliteit.

Wees terughoudend met het excideren en openlaten van een symptomatische sinus pilonidalis vanwege de langdurige wondgenezing.

Sluit de wond niet primair in de middellijn na excisie van een sinus pilonidalis vanwege de hoge kans op wondinfecties en recidieven.

Overweeg bij patiënten met een complexe of recidiverende symptomatische sinus pilonidalis een verschuivingsplastiek toe te passen. Verwijs de patiënt door naar een centrum met expertise indien er geen ervaring is met verschuivingsplastieken in de eigen instelling (zie module Type Verschuivingsplastiek).

Bespreek de voor- en nadelen van de beschikbare technieken met de patiënt om samen tot een behandelkeuze te komen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Minimaal invasief vs. excisie en secundaire wondgenezing

Er is één RCT gevonden die een minimaal invasieve techniek, namelijk fenol behandeling, vergelijkt met excisie en secundaire wondgenezing. In deze studie van Calikoglu (2017) leek het er op dat het aantal recidieven iets hoger is met fenol behandeling, met een gevonden risk ratio van 1.44, hetgeen klinisch relevant is. Fenol lijkt ook een klinisch relevante reductie in wondgenezing tijd van 23.9 dagen te hebben vergeleken met excisie en secundaire wondgenezing. Het bewijs van deze cruciale uitkomstmaten is echter zeer laag en daarom is de overall bewijskracht ook zeer laag. De voornaamste reden voor deze zeer lage bewijskracht is dat er maar één RCT is gevonden, die een hoog risico op bias heeft (omdat er niet geblindeerd is en er geen intention-to-treat analyses zijn uitgevoerd). Het bewijs uit deze ene studie over de belangrijke uitkomstmaten kwaliteit van leven en postoperatieve pijn is ook zeer laag. Het lijkt erop dat er geen verschil is tussen beide groepen wat betreft kwaliteit van leven en dat de fenol groep een significant lagere pijnscore had tot 48 uur na de operatie. De uitkomsten terugkeer naar dagelijkse activiteiten en chirurgische complicaties zijn niet gerapporteerd.

De studie van Pronk (2019) vergelijkt ook fenol met excisie, maar deze is niet meegenomen in de literatuuranalyse omdat bij de controlegroep na excisie de huid gesloten werd (primaire wondgenezing). De huid werd asymmetrisch buiten de middellijn gesloten. Er waren 22% wondinfecties na de excisie en 4% in de fenol groep. Ook bleek in deze studie een aanzienlijk verschil in tijd tot hervatten van dagelijks activiteiten (5 versus 14 dagen) en was de pijnscore lager voor de fenol groep. Tenslotte bleek in deze studie de tijd tot wondgenezing aanzienlijk korter dan bij de excisie en primaire wondgenezing groep (Pronk, 2019). Het recidief percentage van deze patiëntengroepen is nog niet gepubliceerd.

Hoge kwaliteit studies die andere minimaal invasieve technieken vergelijken met excisie en secundaire wondgenezing zijn er niet tot op heden. Deze andere technieken zijn de pit picking of deroofing zonder aanvullende behandeling, de pit picking met aanvullende laserbehandeling, de EPSIT (Endoscopic Pilonidal Sinus Treatment) en de Bascom 1 (pit picking, sluiten in de middenlijn en laterale drainage). Deze technieken zijn wel beschreven in verschillende retrospectieve en prospectieve cohortstudies die hieronder kort besproken zullen worden.

Garg (2016) heeft een systematische review met meta-analyse gepubliceerd waarbij deroofing een recidief percentage van slechts 4% toonde en het hervatten van dagelijkse activiteiten al na gemiddeld 8 dagen optrad. De tijd tot wondgenezing varieerde van 21-72 dagen. In 2021 hebben ze de resultaten van een eigen serie gepubliceerd. Pit picking of deroofing werd onderzocht in een retrospectieve observationele studie van 111 patiënten (Garg, 2021). Deze studie toonde een hoog percentage wondsluiting, namelijk 96%. Patiënten hervatten dagelijkse werkzaamheden na 3.6 ±2.9 dagen. Tijd tot wondgenezing was 43.8 ± 7.4 dagen. Het recidief percentage was 3.7% na een mediane follow-up van 38 maanden. Zowel simpele als complexe sinus pilonidalis werd behandeld. Het voordeel van deze techniek is dat het onder lokale anesthesie uitgevoerd kan worden.

Pit picking met laserbehandeling is onderzocht door o.a. Pappas (2018) en Dessily (2019) bij respectievelijk 237 en 200 patiënten (Dessily, 2019; Pappas, 2018). Zij rapporteerden een hoog wondsluiting percentage (90-94%), gemiddelde tijd tot wondgenezing van 19-47 dagen (range 4-70) en weinig wondinfecties (7-9%). Het recidief percentage varieerde van 10-14% na een follow up meer dan 1 jaar. Resultaten van een recent gepubliceerde Nederlandse studie (niet meegenomen in de literatuursamenvatting, omdat deze na de zoekdatum is gepubliceerd) waren minder succesvol in een groep van 311 patiënten uit drie centra van twee chirurgen. Na een mediane follow-up van tien maanden was het initiële succespercentage slechts 66%, maar na een tweede behandeling 92%. Tijd tot wondgenezing was zes weken (range 1-24). Het recidief percentage was 26% (Sluckin, 2022).

De endoscopische techniek is beschreven door Kalaiselvan (2019), die publiceerden over de EPSIT, waarbij ze concludeerden uit 1 gerandomiseerde studie en 4 case series dat deze techniek vergelijkbare resultaten heeft als andere (minimaal invasieve) technieken.

Een gezamenlijke groep patiënten die pit picking of de Bascom 1 procedure ondergingen toonden een 5 jaar recidief percentage van 15.6% (Stauffer, 2018) Dezelfde pooled data analyse van Stauffer (2018) toonde 5 jaar recidief percentages van 40.4% en 36.6% voor pit picking met aanvullend respectievelijk fenol en laserbehandeling. Deze percentages zijn aanzienlijk hoger dan de resultaten van hierboven genoemde studies.

In vergelijking met excisie en secundaire wondgenezing lijken de minimaal invasieve technieken voordelen te hebben in korte termijn uitkomsten (pijn, wondgenezing tijd, tijd tot hervatten dagelijkse bezigheden) met name vanwege de reductie van het chirurgisch trauma (Calikoglu, 2017). Echter, gezien het gebrek aan degelijk bewijs kunnen deze technieken niet krachtig worden aanbevolen vanuit de richtlijn. Ook kan uit genoemde studies niet duidelijk gemaakt worden welke categorieën sinus pilonidalis werden behandeld en of er verschil in uitkomsten was tussen de verschillende categorieën (zie tabel 2 module 1) De werkgroep is van mening dat deze procedures vooral geschikt lijken voor patiënten met een primaire en beperkte (simpele) sinus pilonidalis. De hoge kans op een recidief moet worden meegenomen in de peroperatieve besluitvorming samen met de patiënt.

Excisie met verschuivingsplastiek vs. excisie en secundaire wondgenezing

Er zijn meerdere studies gevonden die verschillende typen verschuivingsplastieken (Limberg flap, Rhomboid flap, Karydakis flap, Bascom Cleft Lift, Z-plasty repair) vergelijken met excisie en secundaire wondgenezing. Het aantal recidieven is lager met verschuivingsplastieken dan met excisie en secundaire wondgenezing. De gepoolde risk ratio na 12 maanden follow-up is 0.50 in het voordeel van verschuivingsplastieken en dit is een klinisch relevant verschil. De tijd tot complete wondgenezing is korter na verschuivingsplastieken vergeleken met excisie en secundaire wondgenezing. Het gepoolde gemiddelde verschil is 43.7 dagen kortere wondgenezing na verschuivingsplastieken, wat ook klinisch relevant is. De bewijskracht van deze uitkomstmaten is laag (recidieven) en redelijk (tijd tot complete wondgenezing), wat de overall bewijskracht laag maakt. De voornaamste redenen voor de lage bewijskracht is dat er niet geblindeerd is (hetgeen ook nagenoeg niet mogelijk is) en het aantal geïncludeerde patiënten laag is.

De tijd tot terugkeer naar dagelijkse activiteiten lijkt ook korter te zijn bij verschuivingsplastieken. Bij de uitkomstmaat chirurgische complicaties lijken de wondinfecties lager te zijn, maar wonddehiscentie en seroom lijken hoger te zijn bij verschuivingsplastieken. De laatste 2 bevindingen zijn logisch omdat een open wond niet dehiscent kan worden en nagenoeg nooit een seroom holte zal maken. Het is dan ook opmerkelijk dat er in de studie van Jamal (2009) een patiënt in de controle groep met seroom is gevonden. Daarmee zijn deze uitkomstmaten ook minder relevant voor het beantwoorden van de onderzoeksvraag. Datzelfde geldt ook voor chirurgische infecties – een open wond infecteert niet of nauwelijks in vergelijking met een wond waarbij gestreefd wordt naar primaire genezing. Ook de gehanteerde definitie van een wondinfectie is hierbij belangrijk maar is uit deze studies niet goed te achterhalen. De postoperatieve pijn is mogelijk lager bij verschuivingsplastieken, maar het bewijs is erg onzeker en inconsistent. Kwaliteit van leven en complicaties die een heroperatie nodig hebben zijn niet gerapporteerd in de studies.

Verschuivingsplastieken hebben een lagere recidiefkans, een kortere tijd tot wondgenezing en een snellere hervatting van de dagelijkse bezigheden. Ondanks dat de effectgrootte bij het recidief beperkt lijkt, kan een halvering van 7,9% naar 3,7% al aanzienlijk zijn. De vraag is of de recidiefcijfers representatief zijn bij de relatief korte follow-up. Er zijn studies die laten zien dat veel recidieven pas na 1 tot zelfs meer dan 5 jaar optreden (Doll, 2007). Ook zijn er studies die hogere recidiefpercentages tonen na excisie en secundaire wondgenezing (Stauffer, 2018). Deze pooled data analyse laat 5 en 10 jaar recidief percentages zien van 13.1% en 19.9% voor excisie en secundaire wondgenezing, 1.9% en 2.7% voor de Karydakis/Bascom en 5.2% en 11.4% voor de Limberg/Dufourmentel. Wat betreft de tijd tot wondgenezing doen de verschuivingsplastieken het toch echt beter, alhoewel het verschil in de hervatting van de dagelijkse bezigheden minder groot is.

Er zijn geen data gerapporteerd over kwaliteit van leven, een bekend probleem bij de studies over dit onderwerp. Waarschijnlijk leidt een kortere wondgenezing en minder recidieven en het sneller hervatten van het werk of studie tot een betere kwaliteit van leven. Doch dient dit nog eens goed uitgezocht te worden.

Ondanks de lage bewijskracht is de werkgroep van mening dat er grote voordelen kunnen zijn van zowel de korte als de lange termijn uitkomsten van een verschuivingsplastiek ten opzichte van een excisie met secundaire wondgenezing. De vraag is welke type sinus pilonidalis hiervoor het beste in aanmerking komt. In de studies is geen classificatie gebruikt of onderscheid gemaakt in verschillende subgroepen. De werkgroep is van mening dat het voordeel van een verschuivingsplastiek bij een complexe sinus pilonidalis, die waarschijnlijk ook een grotere excisie behoeft, of een recidief sinus pilonidalis, groter zullen zijn dan bij een primaire, simpele sinus pilonidalis. De nadelen van een verschuivingsplastiek ten opzichte van excisie met secundaire wondgenezing zijn beperkt.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De belangrijkste doelen voor de patiënt zijn het verhelpen van de klachten en het verbeteren van de kwaliteit van leven met een behandeling waarvan de patiënt zo min mogelijk last ervaart en die de kans op terugkeer van de ziekte minimaliseert. Het is mogelijk dat patiënten verschillend denken over het belang van de korte termijn (duur van de wondgenezing, pijn en hervatting van de dagelijkse bezigheden) en lange termijn (kans op recidief) uitkomsten. Deze overweging zullen door de zorgverlener met de patiënt moeten worden besproken om tot een gezamenlijk gedragen behandelplan te komen (samen beslissen).

Minimaal invasief vs. excisie en secundaire wondgenezing

Met minimaal invasieve behandelingen is het herstel sneller dan na excisie met secundaire wondgenezing. Hier lijkt wel een grotere kans op recidief tegenover te staan. De kans op een recidief is mogelijk afhankelijk van de grootte van de sinus pilonidalis dan wel het optreden van complicaties (Dessily, 2019). Het is aan de patiënt of hij/zij een sneller herstel nastreeft met het risico nog een keer geopereerd te moeten worden als de behandeling niet slaagt of als er een recidief optreedt. Het lijkt logisch om patiënten met een primaire simpele sinus pilonidalis die actief deelnemen in de maatschappij (scholieren, studenten en werknemers) een minimaal invasieve behandeling te adviseren om zo min mogelijk van het studie/arbeidsproces te missen. Hiervoor is echter geen wetenschappelijke onderbouwing.

Desondanks is de werkgroep van mening dat vooral patiënten met een simpele sinus pilonidalis voordeel kunnen hebben van een minimaal invasieve behandeling.

Excisie met verschuivingsplastiek vs. excisie en secundaire wondgenezing

Verschuivingsplastieken hebben een lagere kans op recidief, een snellere wondgenezing en een eerdere hervatting van de werkzaamheden. Er lijken weinig nadelen van een verschuivingsplastiek ten opzichte van excisie en secundaire wondgenezing. De werkgroep is van mening dat vooral patiënten met een complexe of recidiverende sinus pilonidalis voordeel zullen hebben van een verschuivingsplastiek.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Zowel de korte als de lange termijn uitkomsten kunnen invloed hebben op de kosten. Helaas is dit in de literatuur niet goed uitgezocht. Het is echter aannemelijk dat langdurige wondzorg voor traag genezende (open) wonden duurder is door benodigde verbandmiddelen, eventueel thuiszorg en herhaalde ziekenhuis bezoeken en behandelingen. Recidieven zijn duur omdat de patiënt waarschijnlijk weer een operatie zal ondergaan. Een techniek met een kortere wondgenezing en een lagere kans op een recidief zal daarom zeer waarschijnlijk kosten effectiever zijn dan een techniek waarbij de wond lang nodig heeft om te sluiten of een techniek die een hogere kans op een recidief geeft. Ook de maatschappelijke kosten moeten worden meegewogen omdat na een techniek met een sneller herstel de patiënt weer eerder mee kan doen in het arbeidsproces. De werkgroep is van mening dat de kosteneffectiviteit van de verschillende behandelingen nog moet worden uitgezocht.

Minimaal invasief vs. excisie en secundaire wondgenezing

De kosten voor een minimaal invasieve behandeling variëren. Deroofing en fenol behandeling zijn relatief goedkoop; laserbehandeling en EPSIT zijn duurder door de duurdere materialen. Een laser fiber kost bijvoorbeeld 150-200 euro per behandeling, exclusief de kosten voor de lasergenerator. De aanschaf van een endoscoop met diathermie is ook aanzienlijk. Minimaal invasieve technieken kunnen poliklinisch onder lokale verdoving plaatsvinden, hetgeen dan weer kosten bespaart op een dagopname en klinische operatiekamer (inclusief personeel). Qua kosten voor verbandmiddelen zal dit aanzienlijk minder zijn dan bij excisie en secundaire wondgenezing. Tenslotte zullen minder kosten gemaakt worden door de werkgevers/maatschappij door een sneller herstel.

Excisie met verschuivingsplastiek vs. excisie en secundaire wondgenezing

De kosten van een verschuivingsplastiek zijn mogelijk iets hoger dan die van een excisie met secundaire wondgenezing omdat de operatie langer duurt. Daar staat tegenover dat er waarschijnlijk minder kosten zijn doordat er minder wondzorg en ziekenhuisbezoeken nodig zijn, en er een lagere kans op een recidief bestaat dan bij excisie met secundaire wondgenezing.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Minimaal invasief vs. excisie en secundaire wondgenezing

Er is geen wetenschappelijk onderzoek verricht naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van de interventies (procesevaluatie), maar de werkgroep is van mening dat de implementatie van minimaal invasieve behandelingen niet ingewikkeld hoeft te zijn. De minimaal invasieve technieken zijn van een basis chirurgisch niveau, waarbij voldoende training in het gebruik van fenol, laser of EPSIT wel noodzakelijk is om verkeerd gebruik tegen te gaan. De training hiervoor lijkt echter zeer goed te passen bij elke chirurg of chirurg in opleiding, en zou ook gevolgd kunnen worden door physician assistants en verpleegkundig specialisten.

Het type minimaal invasieve behandeling hangt af van de bekendheid/voorkeur van de chirurg met een specifieke behandeling. Dit wisselt erg per ziekenhuis in Nederland (Galema, 2021). Een mogelijke belemmering voor implementatie van minimaal invasieve technieken is dat er geen passende verrichtingencode is, waardoor de extra kosten niet worden gehonoreerd. Dit is op te lossen door een dergelijke verrichtingencode in te voeren.

Excisie met verschuivingsplastiek vs. excisie en secundaire wondgenezing

Verschuivingsplastieken worden op kleine schaal uitgevoerd in Nederland. Dit zijn de Limberg/Dufourmentel, Karydakis en Bascom Cleft lift procedures. Deze plastieken worden waarschijnlijk zo weinig uitgevoerd omdat ze complexer zijn dan de traditionele excisie technieken en een langere leercurve hebben (Immerman 2021; Johnson, 2019). De learning curve van bijvoorbeeld een Karydakis procedure werd door Wysocki onderzocht. Na 10-20 ingrepen achtte hij zichzelf bekwaam (competent) en na 30-50 ingrepen vaardig (proficient). (Wysocki, 2015). Mogelijke belemmeringen voor de implementatie van verschuivingsplastieken zijn de langere operatieduur en de genoemde leercurve. Goed proctorschap kan dit laatste opvangen en is in Nederland haalbaar. Chirurgen in opleiding krijgen deze technieken momenteel nog niet geleerd tijdens de opleiding tenzij ze werken in een ziekenhuis waar verschuivingsplastieken worden toegepast. De werkgroep is van mening dat elke chirurg deze technieken kan leren en de middelen in zijn/haar ziekenhuis heeft om verschuivingsplastieken uit te voeren. Voor de haalbaarheid is behalve adequaat proctorschap niet veel anders nodig dan goede postoperatieve adviezen aan de patiënt en begeleiding op de polikliniek. Een andere belemmering voor implementatie van de techniek kan zijn dat er geen passende verrichtingencode is voor de verschuivingsplastiek waardoor de extra operatietijd niet wordt gehonoreerd. Dit is op te lossen door een dergelijke verrichtingencode in te voeren.

Er zijn geen redenen bekend waarom een patiënt een verschuivingsplastiek niet kan ondergaan. Alhoewel dit niet aangetoond is middels wetenschappelijk onderzoek, zou ook bij adolescenten en jongvolwassenen een verschuivingsplastiek voordeel kunnen hebben ten opzichte van excisie alleen. Een wondgenezingsstoornis bij een verschuivingsplastiek kan leiden tot een wonddehiscentie. De nazorg en genezingsduur van deze wond is meestal gunstiger dan een wond na excisie en secundaire wondgenezing.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De tijd tot wondgenezing is mogelijk beter na minimaal invasieve behandeling dan na excisie en secundaire wondgenezing, maar hier lijkt een hoger recidief percentage tegenover te staan. De operatieduur is korter en de behandeling kan poliklinisch plaatsvinden, hetgeen zowel voordelen voor de patiënt en werkgever als een ziekenhuis en zorgverzekeraar kan opleveren. Alle voor- en nadelen van minimaal invasieve technieken dienen met een patiënt besproken te worden en dan kan de keuze voor een minimaal invasieve behandeling voor bepaalde patiënten logisch zijn.

Verschuivingsplastieken lijken voordelen te hebben qua duur van wondgenezing en recidieven ten opzichte van excisie met secundaire wondgenezing. Door een kortere duur tot wondgenezing, een lagere recidiefkans en een snellere hervatting van de dagelijkse bezigheden is het aannemelijk dat de kwaliteit van leven stijgt en de maatschappelijke kosten lager zijn, hoewel dit niet is onderzocht. Het doel moet zijn om geen grote wonden in de bilnaad van de patiënt te maken die traag of niet genezen. Om bovengenoemde redenen beveelt de werkgroep zorgverleners aan om een verschuivingsplastiek te verkiezen boven een excisie en secundaire wondgenezing. Indien de expertise voor het verrichten van een verschuivingsplastiek niet aanwezig is wordt het aanbevolen om deze techniek op een veilige manier in de kliniek te implementeren, met aandacht voor learning curve en proctorschap, of een patiënt te verwijzen naar een centrum met expertise.

De werkgroep is van mening dat de uitgebreidheid van de sinus pilonidalis een rol zou moeten spelen bij de keuze voor het type behandeling (minimaal invasief of verschuivingsplastiek). Ook al is er in de beschikbare studies onvoldoende onderzoek gedaan naar de classificatie van de sinus pilonidalis en de keuze voor type behandeling. Bij een beperkte (simpele) sinus pilonidalis kan logischerwijs sneller gekozen worden voor een minimaal invasieve behandeling. Als de ziekte echter complex is, of recidiveert na een minimaal invasieve behandeling, kan gekozen worden voor een verschuivingsplastiek.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Een patiënt met een sinus pilonidalis kan zich presenteren met of zonder symptomen. Bij een symptomatische sinus pilonidalis is een chirurgische behandeling geïndiceerd om klachten zoals pijn, zwelling, verlies van bloederige afscheiding en jeuk weg te nemen. Indien er sprake is van een geabcedeerde sinus pilonidalis zal incisie en drainage de behandeling van keuze zijn, bij voorkeur onder een vorm van anesthesie, afhankelijk van de coleur locale van de behandelende instelling of ziekenhuis. In het geval van een asymptomatische sinus pilonidalis is het advies om dit niet chirurgisch te behandelen, maar preventieve maatregelen te adviseren zoals goede hygiëne van de bilnaad, voorkomen of verwijderen van losse haren in de bilnaad, niet roken en in geval van obesitas af te vallen (NOG TOEVOEGEN: verwijzing naar module 6).

De keuze voor het type chirurgische behandeling bij een symptomatische (niet geabcedeerde) sinus pilonidalis is een belangrijk knelpunt en er heerst veel variatie in de Nederlandse chirurgische praktijk. Ruim 50% van de Nederlandse chirurgen verricht een ‘traditionele’ excisie van de sinus met secundaire wondgenezing of sluiten in de middenlijn (80% secundaire wondgenezing, 20% sluit in de middenlijn). Verschuivingsplastieken en minimaal invasieve technieken worden in mindere mate en met veel variatie in Nederland toegepast (Galema, 2021). Het is onduidelijk waarop de keuze voor deze verschillende benaderingen is gebaseerd en welke techniek de voorkeur verdient. De traditionele excisietechnieken waarbij secundaire wondgenezing of sluiten in de middenlijn worden toegepast hebben het respectievelijke nadeel van een lange wondgenezingstijd ten gevolge van de grote wonden en een hoog percentage wondinfecties en recidieven (Al-Khamis, 2010; Iesalnieks, 2016; Iesalnieks, 2019; Johnson, 2019; McCallum, 2008; Segre, 2015; Stauffer, 2018). Sluiten in de middenlijn wordt daarom sinds ruim 10 jaar afgeraden in reviews en internationale richtlijnen (Al-Khamis, 2010; Iesalnieks, 2016; Iesalnieks, 2021; Johnson, 2019; McCallum, 2008; Milone, 2021; Stauffer, 2018; Segre, 2015). Chirurgische procedures zoals minimaal invasieve technieken (secundaire wondgenezing van kleine wonden) of verschuivingsplastieken (primaire wondgenezing) lijken voordelen te kunnen bieden voor de patiënt.

Omdat excisie met secundaire wondgenezing de meest gebruikte chirurgische techniek is, is ervoor gekozen om in deze analyse de minimaal invasieve technieken en verschuivingsplastieken met deze ‘standaard’ procedure te vergelijken.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Minimal invasive techniques vs. excision with secondary wound healing

Recurrence (crucial)

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of phenol treatment compared to excision with secondary healing on recurrence of pilonidal disease in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Source: Calikoglu, 2017 |

Time to complete wound healing (crucial)

|

low GRADE |

Phenol treatment may reduce the time to complete wound healing, compared to excision with secondary healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Source: Calikoglu, 2017 |

Return to daily activities (important)

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of minimally invasive techniques on return to daily activities when compared to excision with secondary healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Source: - |

Quality of life (important)

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of phenol treatment compared to excision with secondary healing on quality of life in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Sources: Calikoglu, 2017 |

Surgical complications (important)

Wound infection, wound dehiscence, seroma, or complications that required re-operation

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of minimally invasive techniques on surgical complications (wound infection, wound dehiscence, seroma, or complications that required re-operation) when compared to excision with secondary healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

|

Postoperative pain (important)

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of phenol treatment compared to excision with secondary healing on postoperative pain.

Sources: Calikoglu, 2017 |

Excision with flap repair vs. excision with secondary wound healing

|

low GRADE |

Flap repair may reduce recurrence, when compared to excision with secondary healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Sources: Alam, 2018; Fazeli, 2006; Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015; Maghsudi, 2020; Rashidian, 2014 |

Wound healing time (crucial)

|

moderate GRADE |

Flap repair probably has a substantially shorter time to complete wound healing, when compared to excision with secondary healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Sources: Fazeli, 2006; Keshvari, 2015; Maghsudi, 2020; Rashidian, 2014 |

Return to daily activities (important)

|

low GRADE |

Flap repair may have a shorter time to return to daily activities, when compared to excision with secondary healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Sources: Fazeli, 2006; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015; Maghsudi, 2020; Rashidian, 2014 |

Quality of life (important)

|

- GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of flap repair on quality of life when compared to excision with secondary healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease.

|

Surgical complications (important)

Wound infection

|

very low GRADE |

Flap repair may have little to no effect on wound infection compared to excision with secondary healing for symptomatic pilonidal disease, but the evidence is very uncertain.

Sources: Alam, 2018; Fazeli, 2006; Jabbar, 2018; Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015; Maghsudi, 2020; Rashidian, 2014 |

Wound dehiscence

|

low GRADE |

Flap repair entails the possibility of wound dehiscence compared to excision with secondary healing for symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Sources: Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015, Rashidian, 2014 |

Seroma

|

low GRADE |

Flap repair may have little to no effect on seroma compared to excision with secondary healing for symptomatic pilonidal disease.

Sources: Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015, Rashidian, 2014 |

Complications that required re-operation

|

- GRADE |

None of the studies reported on the outcome measure complications that required re-operation, and therefore, this outcome was not graded.

|

Postoperative pain (important)

|

very low GRADE |

Postoperative pain may be lower after excision with flap repair compared to excision with secondary healing, but the evidence is very uncertain.

Sources: Alam, 2018; Fazeli, 2006; Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015; Maghsudi, 2020 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

1. Minimal invasive techniques vs. excision with secondary wound healing

Calikoglu (2017) performed an RCT, comparing crystallized phenol injection with excision with secondary healing technique in patients diagnosed with primary or recurrent chronic pilonidal sinus disease. Patients who had chronic symptoms of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease were included. Patients were excluded from the study if they had acute pilonidal sinus abscess or induration, had abscess drainage within two months, had immunosuppressive and/or coagulation disorders, were pregnant or lactating, or had other acute surgical diseases. In total, 74 patients were randomised to crystallized phenol treatment, and 73 patients were randomised to excision with secondary healing. In total, 147 patients were randomised, but patients lost to follow-up were not analysed, so analyses were not intention-to-treat. In the phenolisation group, the mean age was 30.1 years (sd 7.4), and 54/70 (77%) were men. In the excision group, the mean age was 28.9 years (sd 7.8), and 55/70 (79%) were men. The mean follow-up period was 38.3 (sd 11.3) months (minimum 14, maximum 52 months) in the phenolisation group, and 41.6 (sd 10.6) months (minimum 14, maximum 52) in the excision group.

The following relevant outcome measures were reported: recurrence, time to complete wound healing, quality of life, surgical complications, and postoperative pain. Short-term outcomes were measured at 12, 24 and 48 hours after the procedure (pain and post-operative complications), and long-term outcomes were measured at 3 and 6 weeks, and 3, 6, 12-, 24-, 36- and 48-months follow-up (healing time, recurrence, quality of life). The outcomes were not reported for subgroups with different classification types.

Results

1. Minimal invasive techniques vs. excision with secondary wound healing

Recurrence (crucial)

Calikoglu (2017) reported the recurrence rate at 48 months. In total, 140 patients were analysed, with 70 patients in the crystallized phenol treatment group and 70 patients in the excision with secondary healing group. In the crystallized phenol treatment group, 13/70 (19%) patients had a recurrence, compared to 9/70 (13%) patients in the excision with secondary healing group. The risk ratio is 1.44 (95% CI: 0.66 to 3.16), favouring excision with secondary healing, which is clinically relevant.

Time to complete wound healing (crucial)

Calikoglu (2017) reported on wound healing. They reported the time to complete wound healing as the mean healing time in days. They analysed 140 patients, with 70 patients in the crystallized phenol treatment group and 70 patients in the excision with secondary healing group. In the crystallized phenol treatment group, the mean healing time was 16.2 days (sd 8.7), compared to 40.1 days (sd 9.7) in the excision with secondary healing group. The mean difference is 23.9 days (95% CI: 20.9 to 27.0, p<0.001), favouring crystallized phenol treatment, which is clinically relevant.

Return to daily activities (important)

No study reported the time to return to daily activities. Calikoglu (2017) did not report data on the return to daily activities but stated in the discussion: this study documented significantly improved outcomes following phenol application regarding time to resume daily activities.

Quality of life (important)

Calikoglu (2017) reported on quality of life. In total, 140 patients were analysed, with 70 patients in the crystallized phenol treatment group and 70 patients in the excision with secondary healing group. They measured quality of life with the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) and reported change scores between preoperative and 3-weeks postoperative, on the Short Form-36 Physical Component Summary (SF-36 PCS), and Mental Component Summary (SF-36 MCS). The mean change score in the SF-36 PCS was 4.67 (sd 6.50) in the crystallized phenol treatment group, and 1.71 (sd 8.31) in the excision with secondary healing group. The mean difference in change scores for the SF-36 PCS is 2.96 (85% CI: 0.49 to 5.43), favouring crystallized phenol treatment, which is clinically relevant. The mean change score for the SF-36 MSC was 2.36 (sd 8.23) for the crystallized phenol treatment group, and 0.37 (sd 5.77) for the excision with secondary healing group (p=0.06). The mean difference in change score for the SF-36 MCS is -0.30 (95% CI: -2.72 to 2.12), favouring excision with secondary healing, which is not clinically relevant.

Surgical complications (important)

Wound infection, wound dehiscence, seroma, or complications that required re-operation

No study reported the surgical complications.

Postoperative pain (important)

Calikoglu (2017) reported postoperative pain. In total, 140 patients were analysed, with 70 patients in the phenol group and 70 patients in the excision with secondary healing group. They reported: the phenol group had significantly lower pain compared to excision at 12 hours, 24 hours, and 48 hours (measured with a VAS 1-10). After 48 hours, the VAS score was 0.8 (sd 1.4) in the phenol group and 3.0 (sd 2.2) in the excision with secondary healing group. The mean difference after 48 hours is -2.20 points on the VAS (95% CI: -2.81 to -1.59), favouring phenol, which is clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Minimal invasive techniques vs. excision with secondary wound healing

Recurrence (crucial)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure recurrence was downgraded by one level for risk of bias (no intention-to-treat analyses and no blinding), and by two levels for imprecision (low number of events and patients, and the confidence interval includes ‘no effect’). The level of evidence was therefore graded as very low.

Time to complete wound healing (crucial)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure time to complete wound healing was downgraded by one level for risk of bias (no intention-to-treat analyses and no blinding), and by one level for imprecision (very small number of patients). The level of evidence was therefore graded as low.

Return to daily activities (important)

None of the studies reported on the outcome return to daily activities, and therefore, this outcome was not graded.

Quality of life (important)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life was downgraded by one level for risk of bias (no intention-to-treat analyses, and no blinding), and by two levels for imprecision (very small number of patients, and confidence intervals include ‘no effect’ for one of the subscales of the SF-36). The level of evidence was therefore graded as very low.

Surgical complications (important)

Wound infection, wound dehiscence, seroma, or complications that required re-operation

None of the studies reported on the outcome measures wound infection, wound dehiscence, seroma, or complications that required re-operation, and therefore, these outcomes were not graded.

Postoperative pain (important)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure recurrence was downgraded by one level for risk of bias (no intention-to-treat analyses, and no blinding), and by two levels for imprecision (very small number of patients). The level of evidence was therefore graded as very low.

Description of studies

Excision with flap repair vs. excision with secondary wound healing

Berthier (2019) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs, comparing excision with flap repair vs. excision with secondary healing and/or direct closure techniques in the treatment of chronic pilonidal sinus disease. The inclusion criteria were: English-language randomised controlled studies comparing flap reconstruction vs the laying open technique and/or direct closure for the treatment of chronic pilonidal sinus, with de novo and/or recurrent presentation, in patients aged 14 years or older. Exclusion criteria were: non-randomised studies, retrospective studies, studies concerning pilonidal abscess, and those on the paediatric population. The search period of the SR was from November 1998 to February 2018. The following relevant outcome measures were reported: recurrence, time to complete wound healing, return to work, surgical complications, and postoperative pain. In the systematic review 17 studies were included, of which five studies compared excision and flap repair with excision and secondary healing and met our PICO. The outcomes were not reported for subgroups with different classification types.

These five studies comprised 656 patients with chronic pilonidal disease, of which 328 patients underwent excision with flap repair and 328 patients underwent an excision with secondary healing. In 3 studies, the intervention group had a rhomboid excision with Limberg flap (Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Rashidian, 2014), in one study a Z-plasty repair (Fazeli, 2006), and in one study a Karydakis flap (Keshvari, 2015). The follow-up period ranged from 12 to 49 months. The primary outcome of the SR was recurrence rate, which was defined as the reappearance of symptoms after complete healing and an asymptomatic period. Secondary outcome measures were complete wound-healing time, duration of the incapacity to work, and quality of life and/or patient satisfaction. Wound-healing time was defined as the period of complete epithelization with the discontinuation of wound care in case of excision with secondary healing, and time for the removal of stitches in case of direct closure or flap repair. The duration of the incapacity to work was expressed in postoperative days and corresponds to the time to return to work. Studies were included if they provided data on the recurrence rate (the primary endpoint of the meta-analysis). Studies that compared one type of flap or procedure vs another were excluded.

Magshudi (2020) performed an RCT, comparing excision with flap repair with excision and secondary wound healing among patients with pilonidal cysts. A third arm with primary closure, was not taken into account in our analyses. Patients with primary pilonidal cysts or abscesses were enrolled in the study, while patients with immune deficiency disease or diabetes were excluded from the study. In total, 50 patients were randomised to excision and closure with Limberg flap reconstruction, and 50 patients were randomised to excision with secondary closure. In the Limberg flap group, the median age was 24 years (sd 4.6), and 29/50 (58%) were men. In the excision with secondary healing group, the median age was 26.7 years (sd 4.7), and 34/50 (68%) were men. Patients returned to the clinic after 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months following discharge and were evaluated for study outcomes. The following relevant outcome measures were reported: recurrence, time to complete wound healing, return to work, surgical complications, and postoperative pain. The outcomes were not reported for subgroups with different classification types.

Alam (2018) performed an RCT, comparing excision with Limberg flap with wide excision and secondary healing among patients with primary sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Inclusion criteria were not specified. Exclusion criteria were having a systemic disease affecting wound healing, presence of acute inflammation or associated with abscess formation. In total, fifteen patients underwent excision of the sinus with rhomboid skin incision and Limberg flap, and fifteen patients underwent excision with secondary healing. In the Limberg flap group, the mean age was 27.4 years (sd 6.2), and 13/15 (87%) were male. In the excision with secondary healing group, the mean age was 29.2 (sd 8.4), and 14/15 (93%) were male. Follow-up was done during regular outpatient visits, up to 3 months. The following relevant outcome measures were reported: recurrence, return to work, surgical complications, and postoperative pain. The outcomes were not reported for subgroups with different classification types.

Jabbar (2018) performed an RCT, comparing primary closure with Limberg flap procedure with an open surgical excision with secondary healing among patients with pilonidal disease. Inclusion criteria were individuals aged between 15 and 45 years, who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of chronic discharging sinus/sinuses in natal cleft with or without surrounding tissue inflammation and with associated pain and bleeding on clinical evaluation. Exclusion criteria were patients who were terminally ill, had uncontrolled diabetics, were immunocompromised and immunosuppressed, had acute pilonidal abscess or patients who had undergone multiple surgeries for this disease. In the Limberg flap group, the mean age was 27.4 years (sd 5.90), and 19/20 (95%) were male, and in the excision with secondary healing group the mean age was 28.4 years (sd 6.1), and 27/30 (90%) were male. Patients were assessed post-operatively, on the day of discharge, and at day 7, 14 and 21. The following relevant outcome was reported: surgical complications (wound infection rate). Return to work was mentioned as an outcome in the Methods section but was not reported in the Results. The outcomes were not reported for subgroups with different classification types.

Results

Excision with flap repair vs. excision with secondary wound healing

Recurrence (crucial)

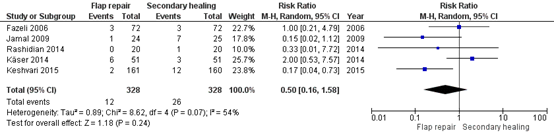

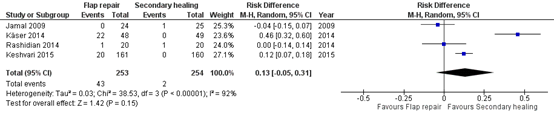

Seven studies reported the recurrence rate. Five studies reported the recurrence rate (Fazeli, 2006; Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015; Rashidian, 2014), with a mean follow-up of at least 12 months. In total, 656 patients were analysed, with 328 in the flap repair group and 328 in the excision with secondary healing group. In the flap repair group, 12/328 (3.7%) patients had a recurrence, compared to 26/328 (7.9%) patients in the excision with secondary healing group. The pooled risk ratio is 0.50 (95% CI: 0.16 to 1.58) favouring flap repair (Figure 1), which is clinically relevant.

Two studies (Alam, 2018; Maghsudi, 2020), reported the recurrence rate at 3 months follow-up. Alam (2018) reported recurrences in 1/15 (7%) patients in the flap repair group, and 5/15 (33%) patients in the excision with secondary healing group (RR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.03 – 1.51). Maghsudi (2020) reported no recurrences in both groups. These studies were not taken into account in the pooled analyses, because of the short follow-up period.

Figure 1. Outcome recurrence rate (>12 months follow-up) with excision with flap repair versus excision with secondary healing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

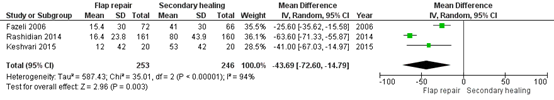

Time to complete wound healing (crucial)

Four studies reported the time to complete wound healing. Three studies reported the mean time to wound healing (Fazeli, 2006; Keshvari, 2015; Rashidian, 2014). In these three studies, 499 patients were analysed, with 253 in the flap repair group and 246 in the excision with secondary healing group. The pooled mean difference is -43.7 days (95% CI: -72.6 to -14.8 days), favouring flap repair (Figure 2), which is clinically relevant.

One study reported the median time to wound healing (Maghsudi, 2020). The median days to complete wound healing was 15.7 days (sd 1.2, range 14 – 18 days) in the intervention group, and 39.6 days (sd 2.6, range 35 – 45 days) in the control group.

Figure 2. Outcome time to complete wound healing (in days) with excision with flap repair versus excision with secondary healing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

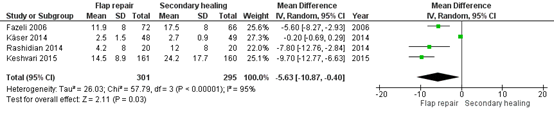

Return to daily activities (important)

Five studies reported on the return to daily activities. Four studies reported the mean time of incapacity from work (Fazeli, 2006; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015; Rashidian, 2014). In total, 596 patients were analysed, with 301 in the flap repair group and 295 in the excision with secondary healing group. The mean days of incapacity from work ranged from 2.5 to 14.5 days in the intervention group, and from 2.7 to 24.2 days in the control group. The pooled mean difference is -5.6 days (95% CI: -10.9 to -0.4 days), favouring flap repair (Figure 3), which is clinically relevant.

One study reported the median time to return to work (Maghsudi, 2020). The median days to return to work were 13.9 (sd 0.8, range 12 – 15 days) in the intervention group, and 23.7 (sd 1.4, range 20 – 26 days) in the control group.

Figure 3. Outcome return to daily activities (in days) with excision with flap repair versus excision with secondary healing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

Quality of life (important)

None of the studies reported on quality of life.

Surgical complications (important)

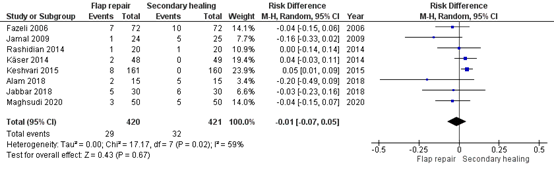

Wound infection

Eight studies reported the wound infection rate (Alam, 2018; Fazeli, 2006; Jabbar, 2018; Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015; Maghsudi, 2020; Rashidian, 2014). In total, 846 patients were analysed, with 420 in the flap repair group, and 421 in the excision with secondary healing group. In the flap repair group, there were 29 (7%) wound infections, and in the excision with secondary healing group there were 32 (8%) infections. The pooled risk difference is -0.01 (95%CI: -0.07 to 0.05), favouring flap repair (Figure 4), which is not clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Outcome wound infection (surgical complications) with excision with flap repair versus excision with secondary healing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

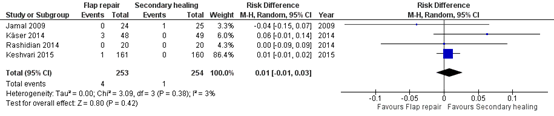

Wound dehiscence

Four studies reported on wound dehiscence (Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015, Rashidian, 2014). In total, 507 patients were analysed, with 253 in the flap repair group, and 254 in the excision with secondary healing group. In the flap repair group, there were 43 (17%) patients with wound dehiscence, and in the excision with secondary healing group there were 2 (0.8%) patients with wound dehiscence. The pooled risk difference is 0.13 (95% CI: -0.05 to 0.31), favouring excision with secondary healing (Figure 5), which is clinically relevant.

Figure 5. Outcome wound dehiscence (surgical complications) with excision with flap repair versus excision with secondary healing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

Seroma

Four studies reported on seroma (Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015, Rashidian, 2014). In total, 507 patients were analysed, with 253 in the flap repair group, and 254 in the excision with secondary healing group. In the flap repair group, there were 4 (1.6%) patients with seroma, and in the excision with secondary healing group there was 1 (0.4%) patient with seroma. The pooled risk difference is 0.01 (95% CI: -0.01 to 0.03), favouring excision with secondary healing (Figure 6), which is not clinically relevant.

Figure 6. Outcome seroma (surgical complications) with excision with flap repair versus excision with secondary healing

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom, I2: statistical heterogeneity, CI: confidence interval

Complications that required re-operation

None of the studies reported on complications that required reoperation.

Postoperative pain (important)

Six studies reported on postoperative pain (Alam, 2018; Fazeli, 2006; Jamal, 2009; Käser, 2014; Keshvari, 2015; Maghsudi, 2020). In total, 746 patients were analysed, with 373 in the flap repair group, and 373 in the excision with secondary healing group. Due to the different instruments, and timepoints at which pain was assessed, it was not possible to pool the data. The following information was reported:

Fazeli (2006): On discharge, the two groups reported similar overall degrees of pain during their stay (measured with McGill pain questionnaire).

Jamal (2009): The severity of pain was significantly lower in the intervention group (measured with verbal rating scale (VRS), not clear at which point this was measured).

Käser (2014): Mean pain score at discharge and at 3 weeks postoperative, and intake of more than one pain killer at discharge were not statistically significant different, between both groups (measured as pain intensity on a graduated scale from 0 to 10 (no pain to worst pain).

Keshvari (2015): The intervention group showed significantly higher pain on their first postoperative day and significantly less pain after 1 week. After 1 month follow-up, there was no statistically significant difference in pain scores between both groups (postoperative pain was assessed using a visual analog scale scored from 1-10).

Alam (2018): The intervention group showed significant less postoperative pain than the control group (measured with categories: mild, moderate, or severe pain).

Maghsudi (2020): The severity of pain was significantly higher in the intervention than in the control group (measures with a VAS, not clear at which point this was measured).

Because it was not possible to pool the data, it is not possible to state whether the differences in pain are clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

Excision with flap repair vs. excision with secondary wound healing

Recurrence (crucial)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure recurrence was downgraded by two levels for imprecision (low number of events and patients, and the confidence interval includes ‘no effect’). The level of evidence was therefore graded as low.

Time to complete wound healing (crucial)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure time to complete wound healing was downgraded one level for imprecision (low number of patients). The level of evidence was therefore graded as moderate.

Return to daily activities (important)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure return to daily activities was downgraded two levels for imprecision (low number of patients, and confidence interval exceeds no clinically relevant effect). The level of evidence was therefore graded as low.

Quality of life (important)

None of the studies reported on the outcome measure quality of life, and therefore, this outcome was not graded.

Surgical complications (important)

Wound infection

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure wound infection was downgraded by one level for inconsistency, and by two levels for imprecision (low number of patients, and confidence interval includes no effect). The level of evidence was therefore graded as very low.

Wound dehiscence

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure wound dehiscence was downgraded by two levels for imprecision (low number of patients, and confidence interval includes no effect). The level of evidence was therefore graded as low.

Seroma

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure seroma was downgraded by two levels for imprecision (low number of patients, and confidence interval includes no effect). The level of evidence was therefore graded as low.

Complications that required re-operation

None of the studies reported on the outcome measure complications that required re-operation, and therefore, this outcome was not graded.

Postoperative pain (important)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as the evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain was downgraded by one level for inconsistency, and by two levels for imprecision (low number of patients). The level of evidence was therefore graded as very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. What are the beneficial and harmful effects of minimally invasive techniques compared with excision with secondary wound healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal sinus?

P: Patients with symptomatic pilonidal sinus

I: Minimally invasive techniques

C: Excision with secondary wound healing

O: Time to complete wound healing, recurrence, surgical complications, postoperative pain, return to daily activities, quality of life.

2. What are the beneficial and harmful effects of excision with flap repair techniques compared with excision with secondary wound healing in patients with symptomatic pilonidal sinus?

P: Patients with symptomatic pilonidal sinus

I: Excision and primary closure using (f)lap repair techniques

C: Excision with secondary wound healing

O: Time to complete wound healing, recurrence, surgical complications, postoperative pain, return to daily activities, quality of life.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered time to complete wound healing and recurrence as crucial outcome measures for decision-making; and surgical complications, postoperative pain, return to daily activities, and quality of life as important outcome measures for decision making.

The guideline development group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Recurrence: a healed surgical site with de novo midline pits/sinus/secondary sinus opening after a symptom free period. Total recurrence rate of the study should be measured preferably with a study follow-up of at least 12 months.

- Time to complete wound healing: time to complete epidermisation with stopping of wound care in case of an open excision, or time to the removal or absorption of stitches in case of direct closure or flap repair.

- Return to daily activities: time from surgery to first day of return to daily activity (including work, sports, study or other activities).

- Quality of life: quality of life measured with a validated questionnaire.

- Surgical complications: wound infection, wound dehiscence, seroma or any complication that requires re-operation.

- Postoperative pain: postoperative pain measured with a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) or the reported use of analgesics.

If possible, subgroup analyses will be performed for specific subtypes of pilonidal sinus (see Module 1 – Classificatie [link]).

The guideline development group used the GRADE standard limits of 25% for dichotomous outcome measures as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. Risk ratios were described where possible. If studies reported no events in one of the groups, risk differences were used. A risk difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant.

The following limits were used for minimal clinically (patient) important differences per outcome:

- Recurrence: GRADE standard limits of 25% for dichotomous outcome measures (RR <0.80 or RR >1.25)

- Time to complete wound healing: 1 working week (5 days)

- Return to daily activities: 1 working week (5 days)

- Quality of life: 0.5 sd

- Surgical complications: GRADE standard limits of 25% for dichotomous outcome measures (RR <0.80 or RR >1.25)

- Postoperative pain: 2 points on a VAS-scale.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until October 1st, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 187 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: included patients with symptomatic pilonidal disease, compared minimally invasive techniques with excision and secondary healing (question 1) or compared excision and flap repair techniques with excision and secondary healing (question 2), reported at least one of the outcomes of interest, the study design is a systematic review (SR) of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or RCT, and was written in English language.

Based on title and abstract screening, 49 studies (19 SRs and 30 RCTs) were initially selected. After reading the full texts, 44 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included (one for question 1, and four for question 2). The results, level of evidence, and conclusions are presented for both questions separately.

Results

1. Minimal invasive techniques vs. excision with secondary wound healing

One RCT was included in the analysis of the literature for question 1. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

2. Excision with flap repair vs. excision with secondary wound healing

Four studies (one systematic review (with five relevant RCTs) and three RCTs) were included in the analysis of the literature for question 2. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Alam, M., Tarar, N. A., Tarar, B. A., & Alam, M. (2018). Comparative Study for Treatment of Sacrococcygeal Pilonidal Sinus with Simple Wide Excision Versus Limberg Flap. PAKISTAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES, 12(3), 911-913.

- Al-Khamis, A., McCallum, I., King, P. M., & Bruce, J. (2010). Healing by primary versus secondary intention after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus. status and date: Edited (no change to conclusions), published in, (1).

- Berthier, C., Bérard, E., Meresse, T., Grolleau, J. L., Herlin, C., & Chaput, B. (2019). A comparison of flap reconstruction vs the laying open technique or excision and direct suture for pilonidal sinus disease: A meta‐analysis of randomised studies. International wound journal, 16(5), 1119-1135.

- Calikoglu, I., Gulpinar, K., Oztuna, D., Elhan, A. H., Dogru, O., Akyol, C., ... & Kuzu, M. A. (2017). Phenol injection versus excision with open healing in pilonidal disease: a prospective randomized trial. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 60(2), 161-169.

- Dessily, M., Dziubeck, M., Chahidi, E., & Simonelli, V. (2019). The SiLaC procedure for pilonidal sinus disease: long-term outcomes of a single institution prospective study. Techniques in coloproctology, 23(12), 1133-1140.

- Doll, D., Krueger, C. M., Schrank, S., Dettmann, H., Petersen, S., & Duesel, W. (2007). Timeline of recurrence after primary and secondary pilonidal sinus surgery. Diseases of the colon & rectum, 50(11), 1928-1934.

- Fazeli, M. S., Adel, M. G., & Lebaschi, A. H. (2006). Comparison of outcomes in Z-plasty and delayed healing by secondary intention of the wound after excision of the sacral pilonidal sinus: results of a randomized, clinical trial. Diseases of the colon & rectum, 49(12), 1831-1836.

- Galema, H., Vles, W., Gosselink, M., Schouten, R., Smeenk, R., Toorenvliet, B. (2021) Huidige behandeling van sinus pilonidalis in Nederland. Ned Tijdschr v Heelkunde, 30(1), 20-23.

- Garg, P., Menon, G. R., & Gupta, V. (2016). Laying open (deroofing) and curettage of sinus as treatment of pilonidal disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. ANZ journal of surgery, 86(1-2), 27-33.

- Garg, P., & Yagnik, V. D. (2021). Laying Open and Curettage under Local Anesthesia to Treat Pilonidal Sinus: Long-Term Follow-Up in 111 Consecutively Operated Patients. Clinics and Practice, 11(2), 193-199.

- Iesalnieks, I., Ommer, A., Petersen, S., Doll, D., & Herold, A. (2016). German national guideline on the management of pilonidal disease. Langenbeck's archives of surgery, 401(5), 599-609.

- Iesalnieks, I., Ommer, A., Herold, A., & Doll, D. (2021). German National Guideline on the management of pilonidal disease: update 2020. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery, 1-12.

- Immerman, S. C. (2021). The Bascom Cleft Lift as a Solution for All Presentations of Pilonidal Disease. Cureus, 13(2).

- Jamal, A., Shamim, M., Hashmi, F., & Qureshi, M. I. (2009). Open excision with secondary healing versus rhomboid excision with Limberg transposition flap in the management of sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. J Pak Med Assoc, 59(3), 157-60.

- Johnson, E. K., Vogel, J. D., Cowan, M. L., Feingold, D. L., & Steele, S. R. (2019). The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ clinical practice guidelines for the management of pilonidal disease. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 62(2), 146-157.

- Käser, S. A., Zengaffinen, R., Uhlmann, M., Glaser, C., & Maurer, C. A. (2015). Primary wound closure with a Limberg flap vs. secondary wound healing after excision of a pilonidal sinus: a multicentre randomised controlled study. International journal of colorectal disease, 30(1), 97-103.

- Keshvari, A., Keramati, M. R., Fazeli, M. S., Kazemeini, A., Meysamie, A., & Nouritaromlou, M. K. (2015). Karydakis flap versus excision-only technique in pilonidal disease. journal of surgical research, 198(1), 260-266.

- Maghsudi, H., Almasi, H., Toomatari, S. E. M., Fasihi, M., Salamat, S. A., Toomatari, S. B. M., & Hemmati, M. (2020). Comparison of primary closure, secondary closure, and Limberg flap in the surgical treatment of pilonidal cysts. Plastic Surgical Nursing, 40(2), 81-85.

- McCallum, I. J., King, P. M., & Bruce, J. (2008). Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 336(7649), 868-871.

- Milone, M., Basso, L., Manigrasso, M., Pietroletti, R., Bondurri, A., La Torre, M., ... & Gallo, G. (2021). Consensus statement of the Italian society of colorectal surgery (SICCR): management and treatment of pilonidal disease. Techniques in Coloproctology, 25(12), 1269-1280.

- Pappas, A. F., & Christodoulou, D. K. (2018). A new minimally invasive treatment of pilonidal sinus disease with the use of a diode laser: a prospective large series of patients. Colorectal Disease, 20(8), O207-O214.

- Segre, D., Pozzo, M., Perinotti, R., & Roche, B. (2015). The treatment of pilonidal disease: guidelines of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR). Techniques in coloproctology, 19(10), 607-613.

- Sluckin, T. C., Hazen, S. M. J., Smeenk, R. M., & Schouten, R. (2022). Sinus laser-assisted closure (SiLaC®) for pilonidal disease: results of a multicentre cohort study. Techniques in Coloproctology, 1-7.

- Stauffer, V. K., Luedi, M. M., Kauf, P., Schmid, M., Diekmann, M., Wieferich, K., ... & Doll, D. (2018). Common surgical procedures in pilonidal sinus disease: a meta-analysis, merged data analysis, and comprehensive study on recurrence. Scientific reports, 8(1), 1-28.

- Pronk, A. A., Smakman, N., & Furnee, E. J. B. (2019). Short-term outcomes of radical excision vs. phenolisation of the sinus tract in primary sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease: a randomized-controlled trial. Techniques in coloproctology, 23(7), 665-673.

- Wysocki, A. P. (2015). Defining the learning curve for the modified Karydakis flap. Techniques in coloproctology, 19(12), 753-755.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What are the beneficial and harmful effects of minimally invasive techniques, compared to excision and secondary closure, in patients with symptomatic pilonidal sinus?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

||||||||||||||||

|

Calikoglu, 2017 |

Type of study: Randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Two university medical schools, Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: Financial disclosures: none reported. Conflict of interest: not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients aged 18 years and older who were diagnosed with primary or recurrent chronic pilonidal sinus disease were considered eligible. Patients who had chronic symptoms of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease were included.

Exclusion criteria: 1) had acute pilonidal sinus abscess or induration, 2) had abscess drainage within 2 months, 3) had immunosuppressive and/or coagulation disorders, 4) were pregnant or lactating, 5) had other acute surgical diseases.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 74 Control: 73

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD (min-max) I: 30.1 ± 7.4 (18–55) C: 28.9 ± 7.8 (17–50)

Sex n/N (%) men) I: 54/70 (77%) C: 55/70 (79%)

BMI kg/m2, mean ± SD (min–max) I: 25.5 ± 3.3 (19.7–36.0) C: 25.9 ± 2.7 (18.6–33.6)

Groups comparable at baseline? Both groups were comparable regarding baseline data except that daily sitting time was significantly higher in the phenol group, whereas daily standing time was significantly higher in the surgery group |

Crystallized phenol treatment

The phenol application was performed following local anesthesia with Lidocain (Jetokain, Adeka İlaç Sanayii, İstanbul, Turkey). If the sinus opening was less than 3 mm in diameter, then the opening was enlarged by use of a mosquito clamp (BH-109 Aesculap, Aescuplap Werke AG, Tutlingen, Germany). If at least one of the sinus openings was 3 mm or more in diameter, we did not perform this enlargement. Following determination of the direction of the sinus, the hair was removed with use of the same clamp. If the sinus abscess had been drained previously, then the drainage opening was usually large enough to remove the hair. After removal of the hair, a swab or large piece of cotton wool was used to protect the anus, while the rest of the area was liberally coated with nitrofurantoin ointment (Furacin Soluble Dressing Pomad, Eczacıbaşı İlaç San ve Tic A.Ş., İstanbul, Turkey) to protect the skin against possible contact with phenol. The crystallized phenol was put into the sinus with the aid of the same clamp. The crystallized phenol melted quickly at body temperature and filled the sinus. The phenol was left in situ for approximately 2 minutes and then expressed by pressure. The excess was mopped away with the debris. This maneuver was repeated 2 or 3 times, depending on the width of the sinus. Finally, the wound was closed with a gauze pack. All procedures were performed with the patient in a prone position. Necrotic debris was removed from the cavity after 24 hours. Afterward, there was no longer need for regular dressings, and ordinary sanitary napkins over the wound were enough to prevent soiling the clothes. If the patient’s wound had no leakage at the follow-up periods, then no further procedure was done. If wound leakage was observed, then the same method described above was repeated. |

Excision with open healing surgery

The surgical procedure was performed under spinal anesthesia. Patients were positioned in the prone jackknife position, and the buttocks were drawn to the side by an adhesive tape. Methylene blue was injected to define the exact borders of the disease, if required. An elliptical incision of the skin was made around the pilonidal sinus. Surgical diathermy was used for further complete excision of the sinus or cyst, if necessary, up to the level of the fasia. Following the excision, the open healing technique was performed with marsupialization, where appropriate. After hemostasis, the wound was covered with sterile gauze. |

Length of follow-up: 48 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 4 (5%) Reasons: lost to follow-up (n=3), discontinued intervention (refused to use second application) (n=1).

Control: 3 (4%) Reasons: lost to follow-u (n=3).

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 4 (5%) Reasons: lost to follow-up (n=3), discontinued intervention (refused to use second application) (n=1).

Control: 3 (4%) Reasons: lost to follow-u (n=3).

|

Recurrence Defined as detection of new orifices or discharge from the wound after complete healing. I: 13/70 (19%) C: 9/70 (13%) P=0.92

Time to complete wound healing Defined as healing time in days. Mean (sd) I: 16.2 (8.7) C: 40.1 (9.7) P<0.001

Return to daily activities Data not explicitly reported. In discussion: this study documented significantly improved outcomes following phenol application regarding time to resume daily activities.

Quality of life SF-36 Physical Component Summary Change score (preop-3 wk postop) I: 4.67 ± 6.50 C: 1.71 ± 8.31 P=0.10

SF-36 Mental Component Summary; Change score (preop-3 wk postop) I: 2.36 ± 8.23 C: 0.37 ± 5.77 P=0.06

Surgical complications Not reported.

Postoperative pain Measured with a VAS (1-10) Mean ± SD and median (minimum and maximum values)

|

- Author’s conclusion: Our prospective, randomized study assessed the effects of phenol injection in the surgical management of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease. Based on the results, we conclude that phenol injection is as effective as the excision with open healing technique.

- No intention-to-treat analyses.

- One patient in the phenol group was excluded from the analysis because of recurrence at the 18th month, and he withdrew.

- Mean recurrence-free time was 45.8 ± 1.6 months for the phenol group and 47.8 ± 1.4 months for the surgery group |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What are the beneficial and harmful effects of excision and primary closure, compared to excision and secondary closure, in patients with symptomatic pilonidal sinus?

Evidence table for intervention studies

Research question: What are the beneficial and harmful effects of excision and primary closure, compared to excision and secondary closure, in patients with symptomatic pilonidal sinus?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Maghsudi, 2020 |

Type of study: Randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Single center, Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with primary pilonidal cysts or abscesses.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with immune deficiency disease or diabetes.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: Age (Median ± SD (range)) I: 24.0 ± 4.6 (14–36) C: 26.7 ± 4.7 (14–34)

Sex: (n/N (%) men) I: 29/50 (58%) C: 34/50 (68%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported. |

Surgical repair with a Limberg flap

The skin of the involved area was incised to the subcutaneous region using two crescent-shaped incisions. The pilonidal cyst was removed together with some of the surrounding fat down to the aponeurosis layer of the erector spinae muscle. The excised tissue was thoroughly examined to ensure the cyst was completely removed. The surgical wound was then irrigated and Limberg flap reconstruction was performed. The wound was closed in two layers using 2-0 Vicryl suture (Ethicon Inc.) for the subcutaneous tissue and interrupted 2-0 Nylon sutures for skin closure. One Hemovac Evacuator drain (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN) was placed in the wound and removed 2 days after surgery. |

Secondary closure

The skin of the involved area was incised to the subcutaneous region using two crescent-shaped incisions. The pilonidal cyst was removed together with some of the surrounding fat down to the aponeurosis layer of the erector spinae muscle. The excised tissue was thoroughly examined to ensure the cyst was completely removed. The surgical wound was then irrigated and left open to heal by secondary intention. |

Length of follow-up: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Numbers and reasons were not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Numbers and reasons were not reported. |

Recurrence Recurrence of pilonidal cyst after surgery was not observed in any of the patients.

Time to complete wound healing Median ± sd (range) I: 15.7 ± 1.2 (14–18) C: 39.6 ± 2.6 (35–45)

Return to daily activities Median ± sd (range) I: 13.9 ± 0.8 (12–15) C: 23.7 ± 1.4 (20–26)

Quality of life Not reported.

Surgical complications Surgical site infection I: 6% (3/50) C: 10% (5/50)

Wound dehiscence, seroma, or complications that required re-operation were not reported.

Postoperative pain Severity of pain measured with a VAS (range of scale not reported). Median score I: 2.0 C: 5.7 The severity of pain was significantly higher in the group Flap repair than in the group with secondary healing (p < .001). Not clear at which point this was measured. |

- This study was conducted to compare simple surgical closure (group A), secondary healing (group B), and closure using a Limberg flap (group C) in the treatment of patients affected with pilonidal cysts. Only the groups with Limberg flap (intervention) and secondary healing (control) were taken into account in our analyses.

- Authors’ conclusion: Although the procedure takes longer when using a Limberg flap, it appears to be a more effective method in the surgical treatment of patients with pilonidal cyst because of the reduced healing time and improved functional status after the procedure.

- Wound dehiscence was only reported in group A and C, and was therefore not taken into account. |

|

Alam, 2018 |

Type of study: Randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Single center, Pakistan

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with primary sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Exact inclusion criteria were not reported

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded from this study, having systemic disease affecting wound healing, presence of acute inflammation or associated with abscess formation.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 15 Control: 15

Important prognostic factors2:

Age Mean ± SD (range): I: 27.4 ± 6.2 (18-40) C: 29.2 ± 8.4 (20-45)

Sex: (n/N (%) men) I: 13/15 (97%) C: 14/15 (93%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Not reported. |

Excision of the sinus with rhomboid skin incision and Limberg flap

Description: Rhomboid-shaped incision was made around the sinus which was equal in length on each side from the mouth of the sinus. The excision was at least 1cm away from the sinus. Rhomboid fascio-cutaneous flap was divided and mobilized from the underlying gluteus muscle. The flap was sutured without tension in 2 layers (subcutaneous fat with 3/0 polygalactin and closure of the skin with prolene 2/0). Suction drain was put behind the flap and removed on the fifth to seventh postoperative day. The skin stitches were removed on the 14th postop day. In the case of wound infection or hematoma, the wound was drained by removal of few sutures with regular daily dressing and covered with broad spectrum antibiotics.

|

Wide excision with secondary healing

Description: Vertical elliptical incision around the sinus was done extending to the presacral fascia. The incision was deepened extending to the presacral fascia. After making sure of good hemostasis, wound was packed with polyfex and povidone–iodine soaked gauze pieces. |

Length of follow-up: Follow up was done to all patients as per performa up to three months in regular outpatient's visits.

Loss-to-follow-up: Numbers and reasons were not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Numbers and reasons were not reported.

|

Recurrence n/N (%) I: 1/15 (6%) C: 5/15 (33%)

Time to complete wound healing Not reported.

Return to daily activities Described in Discussion: Intervention group showed significant statistical difference in comparison with control group as regards time to return to work. Data is not reported.

Quality of life Not reported.

Surgical complications Wound infection I: 2/15 (13%) C: 5/15 (33%)

Wound dehiscence, seroma, or complications that required re-operation were not reported.

Postoperative pain Not specified how it was measured. I: 2 mild, 2 moderate, 1 severe: total 5/15 (33%) C: 3 mild, 3 moderate, 4 severe: total 10/15 (67%). The intervention group showed significant less postoperative pain than the control group. |

- Authors’ conclusion: Rhomboid excision and Limberg flap repair is an advantageous and effective modality than simple excision with secondary healing in treatment of sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. In addition, it is safe and easy procedure. It may be an ideal treatment option in management of pilonidal sinus.