Niet-medicamenteuze interventies

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van niet-medicamenteuze interventies als vervanging van of in aanvulling op medicamenteuze sedatie?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het toevoegen van niet-medicamenteuze interventies, die afleiden van pijn en angst, aan medicamenteuze PSA om hiermee het comfort vergroten.

Overweeg hierbij met name de minimaal belastende interventies, zoals muziek, video of virtual reality beleving.

Bespreek met de patiënt welke niet-medicamenteuze mogelijkheden er zijn en beslis samen welke niet-medicamenteuze behandeling het beste bij de patiënt en de situatie past.

Overweeg om het effect bij het gebruik van de niet-medicamenteuze interventies te meten en documenteren door middel van objectieve scores voor patiënttevredenheid, pijnbeleving en duur van de procedure.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In de literatuur wordt geen overtuigend bewijs gevonden voor het toevoegen van afleiding aan PSA. De bewijskracht is zeer laag. Dit komt voornamelijk omdat de studies niet geblindeerd zijn, er veel verschillende patiëntenpopulaties worden onderzocht en de studieresultaten niet eenduidig dezelfde kant op wijzen. Er ligt hier een kennislacune.

Daarnaast wordt er in de literatuur ook geen overtuigend bewijs gevonden voor toevoegen van hypnose aan PSA. De studies suggereren een kortere duur van de procedure. De studieresultaten voor de uitkomstmaat pijn wijzen niet eenduidig dezelfde kant op. De bewijskracht is laag tot zeer laag. Dit komt voornamelijk omdat de studies niet geblindeerd zijn en er veel verschillende patiëntpopulaties worden onderzocht. Voor de uitkomstmaat patiënttevredenheid ontbreekt het überhaupt aan wetenschappelijke onderbouwing. Er ligt hier een kennislacune. Van de andere kant impliceert “absence of evidence” niet altijd ook “evidence of absence”. Een multimodale benadering van pijn en angst kan soms meer effect hebben dan de som der delen. Betreffende de mogelijke uitkomsten van niet-medicamenteuze interventies bij het toedienen van PSA, is het belangrijk te realiseren dat een (verschil in) dosering van een sedativum weliswaar goed te meten is, maar daarmee niet vanzelfsprekend klinisch relevant hoeft te zijn.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Vanuit de pragmatische invalshoek, klinkt het logisch dat comfort verhogende omstandigheden gepaard zouden kunnen gaan met meer patiënttevredenheid en daaraan gekoppeld angstreductie. Deze uitspraak is gebaseerd op ervaring in de praktijk en niet onderbouwd in de literatuur. Goede informatie vooraf over een procedure en sedatie kan angst verminderen.

Daarnaast is voor het ervaren van pijn essentieel dat er een koppeling is tussen een nociceptieve prikkel en de bewuste beleving hiervan (corticaal proces).

Indien een niet-medicamenteuze interventie kan leiden tot verlaagde aandacht/awareness/bewustzijn (afleiding, verleggen van focus) van een nociceptieve prikkel, is het aannemelijk dat deze als minder/niet pijnlijk kan worden ervaren door een patiënt, ook als er nog reflexmatige reacties (bijvoorbeeld bewegen, terugtrekken, verhoogde hartslag, ademhaling of bloeddruk) zichtbaar zijn. Bespreek met de patiënt welke niet-medicamenteuze mogelijkheden er zijn en beslis samen welke niet-medicamenteuze behandeling het beste bij de patiënt en de situatie past.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het zou wenselijk zijn als aannames en veronderstellingen onderbouwd worden door sterke wetenschappelijke data en kosten/baten analyse. Dit is niet altijd haalbaar en gangbare werkwijze is dat, zolang niet-medicamenteuze interventies gepaard gaan met beperkte kosten en minimale belasting voor een patiënt en procedure, empirische data verkregen wordt uit de praktijk. Belangrijk kader m.b.t. kostenbeheersing, is het voorkomen van inzet van extra personeel en/of dure materialen voor het bewerkstelligen van een niet-medicamenteuze interventie. Als er hoge aanschafkosten van materialen (bijv. VR-bril vs. koptelefoon) zijn en/of aanzienlijke tijdsinvesteringen nodig (bijv. EMDR) rondom een niet-medicamenteuze interventie, terwijl er geen verschil in uitkomst is, dan kunnen deze lasten meegenomen worden in de afweging om de niet-medicamenteuze interventie te implementeren.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Pragmatische en empirische afwegingen zullen leidend moeten zijn om een goede balans in de voor- en nadelen van een implementatie te kunnen onderbouwen. Door praktijkvariatie van zowel interventies als PSA (middelen), zijn de lokale PSA-teams de meest aangewezen betrokkenen, om de haalbaarheid en kosten-baten balans op te maken en af te stemmen met de lokale sedatie commissies.

Rationale van aanbeveling 1: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De werkgroep ziet potentiële meerwaarde in het gebruik van niet-medicamenteuze interventies, mits deze op lokaal niveau wenselijk en haalbaar worden geacht en voldoende afgewogen worden onderbouwd.

Gezien de beperkte level of evidence voor de verschillende methoden, dienen deze interventies als aanvullend te worden beschouwd, niet ter vervanging van PSA.

Minimaal invasieve technieken (bijv. muziek, video of VR) kunnen geïntegreerd worden met medicamenteuze PSA.

Rationale van aanbeveling 2: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Indien niet-medicamenteuze interventies worden toegepast, is het belangrijk om hierbij te overwegen de relevante uitkomst criteria te formuleren en deze te registreren.

Door praktijkvariatie van zowel interventies als PSA (middelen), zijn de lokale PSA-teams de meest aangewezen betrokkenen, om deze te formuleren en te integreren in het patiëntendossier. Objectieve scores voor patiënttevredenheid, pijnbeleving, duur van de procedures en medicatie doseringen, kunnen indicatief zijn voor de uitkomst van een interventie. Hoewel deze scores niet altijd even klinisch relevant of significant zijn, kan er wel een indicatieve interpretatie aan gegeven worden en kunnen ze gebruikt worden voor follow up.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij procedurele sedatie en analgesie (PSA) wordt primair gedacht aan medicamenteuze behandeling, terwijl anxiolyse en pijnervaring ook gedempt kunnen worden door niet-medicamenteuze interventies. Zo bestaan er naast het toedienen van hypnotische en/of analgetische middelen voor PSA ook veel niet-medicamenteuze interventies, zoals virtual reality, video’s, neuro linguïstisch programmeren, hypnose, cognitieve therapie, EMDR, muziek, ademhalingsoefeningen of een prikkelarme omgeving. Deze kunnen in plaats van sedatiemiddelen of als adjuvans aan medicamenteuze sedatie worden ingezet.

Op dit moment is er veel onduidelijk over welke niet-medicamenteuze technieken bewezen van meerwaarde zijn bij de PSA van volwassenen. Er zijn wel lokale initiatieven die nieuwe technieken proberen, maar er bestaat nog geen landelijke richtlijn over. Daarnaast bestaat er grote praktijkvariatie op zowel het gebied van de soorten technieken als hoe deze technieken worden ingezet.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Conclusions (1. Distraction)

Patient satisfaction (crucial)

|

low GRADE |

Distraction may increase patient satisfaction when compared with standard care in adult patients undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia.

Sources: Bechtold, 2006; Moon, 2018; Wang, 2014 |

Pain (crucial)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of distraction on pain when compared with standard care in adult patients undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia.

Sources: Bechtold, 2006; De Silva, 2016; Ebrahimi, 2020; Kang, 2006; Sjölander, 2019; Wang, 2014 |

Procedure duration (important)

|

low GRADE |

Distraction may decrease the procedure duration when compared with standard care in adult patients undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia.

Sources: Akdoğan, 2021; Bechtold, 2006; De Silva, 2016; Fang, 2016; Kang, 2006; Kukreja, 2020; Kulkarni, 2012; Moon, 2018; Wang, 2014 |

Conclusions (2. Breathing exercises, relaxation techniques)

Patient satisfaction (crucial)

|

no GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of hypnosis in addition to standard care on patient satisfaction when compared with standard care in adult patients undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia. Sources: - |

Pain (crucial)

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of hypnosis in addition to standard care on pain when compared with standard care alone in adult patients undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia. Sources: Izanloo, 2015; Mackey, 2018; Noergaard, 2019 |

Procedure duration (important)

|

low GRADE |

Hypnosis in addition to standard care may result in little to no difference in procedure duration when compared with standard care in adult patients undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia. Sources: Noergaard, 2019 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

1. Distraction

Wang (2014) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine effects of music during several types of endoscopies. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included that executed these procedures with and without music. Several databases were searched for RCTs published up to July 2013, including the Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Embase. Twenty-one RCTs comparing patients undergoing various endoscopic examinations with and without music were included, with a total sample size of 2,134. In all trials, standard care was used as the control (no music) condition. The music was self-selected in ten of the trials, and selected by the researchers in eleven trials. In two studies, patients aged younger than 18 years old were included, and in two studies age was not reported. The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs was used assess quality of the studies. Overall, the authors report low risk of bias in the included studies. The reported outcome measures in the study were: patient satisfaction, pain, sedative dose, and procedure duration.

Akdoğan (2021) performed an RCT to compare music therapy with a non-music condition in patients undergoing elective non-oncological orthopedic surgery under spinal anesthesia. No information about the time and setting of the study was reported. Exclusion criteria were hearing loss, professional music practitioners, patients using medication that could affect the hypothalamo-hypophyseal and sympathetic system, patients who did not like the type of music. Note that new patients were recruited in place of patients who were excluded for any reason to reach the planned sample size. Fifty patients were included in the study, of which 25 to the music group (mean age: 41.96, SD: 11.41 y) and 25 to the no music group (mean age: 43.00, SD: 11.26 y). Propofol infusion was started at 1 mg/kg/hour in patients who underwent spinal anesthesia in the operation room. The reported outcome measure in the study was: procedure duration. The study has a high risk of bias as the study was not blinded.

Bashiri (2018) performed a randomized controlled double-blinded study to assess effects of music therapy in addition to sedation administered during endoscopy and colonoscopy in adult patients. The study was conducted between June and October 2017 in a hospital gastroenterology unit in Ankara, Turkey. Patients with endoscopic ultrasound and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography were excluded from the study. Patients were randomized to one of four groups:

- conscious sedation with music (n=33, median age: 44, age range 28-65);

- conscious sedation without music (n=25, median age: 46, age range 28-69);

- deep sedation with music (n=41, median age: 42, age range 24-65);

- deep sedation without music (n=55, median age: 44, range 28-60).

Patients were sedated either by gastroenterologists (conscious sedation) or by anesthesiologists (deep sedation). In the conscious sedation groups, 2 mg of midazolam was administered. In the deep sedation groups, patients were administered 1-2 mg of midazolam, 0.1-0.3 mg/kg of ketamine, and 1-3 mg/kg of propofol. Incremental 20 mg of propofol was administered when the patient moved or felt pain. Music was applied through headphones. In the control groups, no music was played through the headphones. Patients chose their favorite music. The reported outcome measure in the study was: sedation dose. The study has a risk of bias due to baseline differences between the groups.

Bechtold (2006) performed and RCT to compare effects of relaxing music versus no music during colonoscopy under low-dose conscious sedation in 116 patients. No information about the time and setting of the study was reported. Eighty-five patients were randomized the music group (mean age: 58.5 y, SD: not reported), and 81 to the no music group (mean age: 54.1 y, SD: not reported). Exclusion criteria were: patients with a history of prior colon resection, patients scheduled to undergo same-day esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, and inability to give informed consent. In the music group, a CD player was playing relaxing music upon the entrance of the patient into the procedure room. Procedures were started after the patient received 50 mg of meperidine and 1 or 2 mg of midazolam. Additional medication was given at the discretion of the endoscopist. The reported outcome measures in the study were: patient satisfaction, pain, procedure duration and sedation dose. The study has a risk of bias as only the patients were blinded.

De Silva (2016) performed an RCT to compare the effects of audio (AD) and visual distraction (VD) compared to standard care in reducing discomfort and the need for sedation during colonoscopy. The study was carried out in the Professorial Endoscopy Unit, Colombo North Teaching Hospital, Ragama, Sri Lanka, from May 2014 to May 2015. Exclusion criteria were: visual or hearing impairment, allergies or hypersensitivity to premedication, patients who had had abdominal surgery or colectomy, personal history of anxiety or psychiatric disorder, and pregnancy. Two-hundred patients were randomized to one of three groups: 66 patients with a mean age of 54.4 (SD: 12.5) listened to music of their choice, 67 patients with a mean age of 51.5 (SD: 14.6) watched a movie of their choice, and 67 patients with a mean age of 56.5 (SD: 13.8) did not listen to music or watched a movie. Patient controlled analgesia and sedation were administered to all three groups. Sedation consisted of 25 mg of pethidine in 5-mg aliquots and 2.5mg of midazolam in 0.5-mg aliquots. The reported outcome measures in the study were: pain, procedure duration and sedation dose. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not double blinded.

Ebrahimi (2020) performed a prospective pilot study to assess the effect of music on the use of opiates and benzodiazepines and levels of pain and anxiety in adult patients undergoing invasive coronary angiography. The study was conducted between November 2017 and May 2018 in a medical and nursing department Los Angeles, USA. Exclusion criteria included acute myocardial infarction requiring emergency ICA, documented history of major hearing problems or deafness, and contraindication to standard care medications. Seventy-two patients were randomized and enrolled in the study, with 35 randomized to the music group (mean age: 69.57, SD: 8.92) and 37 to the standard care control group (mean age: 68.51, SD: 6.48). All patients received local anesthesia with two percent lidocaine subcutaneously. Midazolam (0.5-1.0 mg) and/or fentanyl (25-50 μg) were administered intravenously to all subjects who requested pharmacologic sedation. Thus, not all patients were sedated pre-emptively. In the music group, music was self-selected and played prior, during, and after the procedure. Music was delivered through a portable media player with single-use, disposable ear buds. Note that patients and caregivers were not blind to the intervention. The reported outcome measures in the study were: pain and sedation dose. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not double blinded.

Fang (2016) performed a study in adult patients (≥ 18 y) to investigate clinical efficacy, safety, and feasibility of wearing video glasses during elective interventional radiologic (IR) procedures. The study was conducted between August 2012 and August 2013 in New York, USA. Exclusion criteria were patients undergoing emergency procedures, requirement of general anesthesia, history of hearing difficulties, visual difficulties, or epileptic seizures. Eighty-three patients were randomized, of which 39 to the experimental group wearing video glasses, and 44 to the control group without video glasses. During the IR procedure, all patients in the experimental group were fitted with video glasses and earpieces. The patient chose a video from a preset list of videos, which included documentaries and general audience–rated movies. Total doses of sedation (intravenous midazolam) and analgesia (intravenous fentanyl) used during the procedure were recorded for both groups. Mean age in the experimental group was 53.1 (SD: 15.2), and 56.4 (SD: 13.5) in the control group. The reported outcome measure in the study was: procedure duration. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not blinded and the groups of patients were very heterogeneous.

Huang (2020) performed a single-center, randomized controlled trial on the effects of immersive virtual reality therapy (IVR) on intravenous patient-controlled sedation during elective total knee and total hip arthroplasty under regional anesthesia. The study was conducted at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, Australia between February and June 2016. Twenty-five patients were randomized to the experimental group (median age: 65, IQR: 57, 68), which received immersive virtual reality (a form of distraction therapy) and propofol patient-controlled sedation (PCS). Twenty-five control patients received propofol PCS alone (median age: 70, IQR: 64, 72). Both groups were able to control their intra-operative sedation using propofol, with instruction to use it whenever they felt too aware or anxious. Each press of the PCS supplied a propofol bolus of 400mcg/kg Ideal Body Weight with a 5-minute lockout period. The reported outcome measure in the study was: sedation dose. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not blinded.

Kang (2008) performed and RCT to determine whether playing music can reduce bispectral index (BIS) values during 1.2 μg/mL propofol sedation in patients undergoing total knee replacement under spinal-epidural anesthesia. The study was conducted in the operating room of a hospital in Seoul, South Korea. Exclusion criteria were: contraindication to regional anesthesia, patients taking herbal medicines or steroid drugs at least 6 months before surgery, or who had a history of chronic psychiatric drug use, poor auditory, renal, or liver function, and cardiopulmonary disease. Sixty-three patients were randomized to one of three groups: 20 to the noise group (standard operating room noise; mean age: 69.2, SD: 7.3 y), 19 to the silence group (ambient noise was blocked; mean age: 68.0, SD: 6.3 y), and 20 to the music group (self-selected music was played through headphones; mean age: 67.8, SD: 7.0 y). The reported outcome measures in the study were: pain and procedure duration. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not double blinded and only performed in the elderly.

Kukreja (2020) performed an RCT to assess effects of music therapy compared with a no music control group on sedation requirements, anxiety levels, and patient satisfaction for adult patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty under spinal anesthesia. The study was conducted between October 2018 and December 2019 in the UAB Highlands Hospital in Birmingham, USA. Exclusion criteria included hearing impairment secondary to age or disease, and any contraindications for spinal anesthesia. Fifty-seven patients were randomized and enrolled in the study, with 29 randomized to the music group (mean age: 65.14, SD: 1.82 y) and 28 to the standard care control group (mean age: 61.68, SD: 2.27 y). Intraoperatively, all patients were given a standardized dose of 1 mg midazolam and 50 mcg fentanyl, as well as started on a propofol infusion. The Bispectral Index Monitor was used to confirm moderate sedation (65-75), where a reading of 70 is labeled as a general representation of moderate sedation. Preoperatively, all patients in both groups received continuous adductor canal block for postoperative analgesia. Music was self-selected and delivered through a pair of study-provided headphones. Note that patients in the control group did not wear headphones during the operation. The reported outcome measures in the study were: procedure duration and sedation dose. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not blinded and a high proportion of the controls did not complete the study.

Kulkarni (2012) performed an RCT on the effects of playing patient-selected music during interventional radiological (IR) procedures on the doses of sedation and analgesia and anxiety levels of adult patients. The study was conducted at the Department of Radiology, Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow, UK. Patients were not included in the study in case of emergency procedures, procedures under general anesthesia, inability to consent, or when they had difficulty hearing. Note that 17 patients declined participation in the study because they insisted on listening to music during the procedure. During the IR procedure, headphones were applied to all patients. The 50 patients in the experimental group (mean age: 57, SD: 16) had self-selected music played to them and the 50 control patients (mean age: 59, SD: 15) had no music played during the procedure. Patient sedation and analgesia were administered as required following the departmental protocol. Note that sedation and/or analgesia were not administered pre-emptively in all procedures. The primary outcomes were reductions in the doses of drugs for sedation (midazolam) and analgesia (fentanyl). The reported outcome measures in the study were: procedure duration and sedation dose. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not double blinded.

Moon (2018) performed a prospective parallel non-crossover single-blind RCT to investigate effects of virtual reality (VR) distraction during endoscopic urologic surgery under spinal anesthesia. The study was conducted at the Seoul National University Hospital in Korea between March and November 2017. Inclusion criteria were scheduled endoscopic urologic surgery, including holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HOLLEP) or transurethral resection of bladder tumor), and an ASA physical status classification of I–III. Patients with a history of chronic use of sedatives or narcotics (>6 months), alcohol or drug abuse, baseline pulse oximetry saturation of less than 90%, and baseline hemodynamic or respiratory instability were excluded. Thirty-seven patients were randomized, of which 18 to the VR group without sedative and 19 to the pharmacologic sedation group. The patients assigned to the VR group were subjected to a 30-min VR program. Patients watched an underwater view of the ocean while listening to narrations designed to induce relaxation and meditation. Sedation in the control group consisted of repeat doses of midazolam 1–2 mg every 30 min during the procedure. Median age in the VR group was: 69 (IQR: 65-70), and 69 (IQR: 63-72) in the control group. The reported outcome measures in the study were: patient satisfaction and procedure time. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not completely blinded.

Sjolander (2019) performed a single-blind RCT to examine whether patients’ experiences could be improved during colonoscopy by designing the examination room to include a digital screen showing calm nature films. The study was conducted at an endoscopy unit in Sweden between 2015 and 2017. Patients were randomized to the intervention group (i.e., the room showing films) or the control group (standard room). Mean age and SD of the 68 patients in the intervention group was 60 y (SD: 2.0), and 61 y (SD: 1.8) of the 69 control patients. In the intervention group, a loudspeaker playing nature sounds such as birdsong or flowing water was placed under the pillow on the examination bed. Five different films of calm nature scenes were randomly shown on the screen. All the colonoscopies were performed according to clinical routine. Each patient was offered an intravenous injection of a sedative drug (midazolam) and an analgesic drug (alfentanil). The reported outcome measure in the study was: pain. The study has a risk of bias as the study was not completely blinded.

Results (distraction)

Patient satisfaction (crucial)

This outcome measure was reported in three studies (Bechtold, 2006; Moon, 2018; Wang, 2014).

Five studies included in the SR from Wang (2014) reported patient satisfaction during endoscopy procedures. The satisfaction score was measured by different methods, therefore the standardized mean difference (SMD) was used for the meta-analysis. Individual study data, as well as the total number of patients included in this meta-analysis was not reported. The level of satisfaction was improved in the music group (SMD = 1.83, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.91). This means that the addition of music results in a higher patient satisfaction compared to the standard procedure. This is considered clinically relevant.

In the RCT performed by Bechtold (2006), 85 patients listened to relaxing music during a colonoscopy, 81 patients did not hear music during their procedure. Patient satisfaction was measured using three different scales: Experience I scale (1 = pleasant, 2 = tolerable, 3 = difficult, 4 = unacceptable); Experience II scale (1 = much better than I expected, 2 = somewhat better than I expected, 3 = about what I expected, 4 = somewhat worse than I expected, 5 = much worse than I expected); Experience III scale (100 mm scale where 0 represents pleasant and 100 represents worst experience I ever have). Patients in both the intervention and control group reported a tolerable patient satisfaction, using the Experience I scale. This means that the patient satisfaction was similar in both groups. When patient satisfaction is measured using the Experience II scale, the intervention group reported a median score of 1 (much better than I expected), and the control group reported a median score of 2 (somewhat better than I expected). This means that patients in the intervention group have a higher patient satisfaction compared to the control group. This difference is clinically relevant. When patient satisfaction is measured using the Experience III scale, the intervention group reported a mean satisfaction of 22.5, compared to 28.1 in the control group. This means that patients in the intervention group have a higher patient satisfaction (mean difference 5.6), however this difference is not considered clinically relevant.

In the RCT performed by Moon (2018), 18 patients received virtual reality distraction during endoscopic prostatectomy under spinal anesthesia, and 19 patients received pharmacological sedation. Patient satisfaction was measured on a 5-point Likert-like verbal rating scale according to a prespecified score-defining table (1 = extremely dissatisfied, 2 = dissatisfied, 3 = undecided, 4 = satisfied, 5 = extremely satisfied). Both groups reported a median patient satisfaction of 5, indicating that patients were extremely satisfied in both groups.

Pain (crucial)

The outcome measure was reported in six studies (Bechtold, 2006; De Silva, 2016; Ebrahimi, 2020; Kang, 2006; Sjölander, 2019; Wang, 2014). Due to heterogeneity in study populations and reporting of outcome measures, the study results were not pooled.

In the SR from Wang (2014) patient’s perception of pain during the procedures was measured on a linear analog scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximal pain) or a VAS scale ranging from 0 (maxima pain) to 100 (no pain). Individual study data, as well as the total number of patients included in this meta-analysis was not reported. The overall effect of the meta-analysis based on the LAS favored music for pain reduction (weighted mean difference (WMD) -1.53, 95% CI -2.53 to -0.53). This means that the addition of music results in more pain reduction compared to the standard procedure, however the effect was small.

In the RCT performed by Bechtold (2006), 85 patients listened to relaxing music during a colonoscopy, and 81 patients did not hear music during their procedure. Pain was reported on a 100 mm scale where 0 represents not painful at all and 100 represents unbearable. It is unclear whether the patients were rating postoperative pain or pain experienced during the procedure. Standard deviations were not reported in this study. Patients who listened to music reported a mean pain intensity of 25.3 mm, while patients in the control group reported a mean pain intensity of 28.1 mm. The mean difference was 2.8 mm, in favour of the intervention group. However, this difference was not considered clinically relevant.

In the RCT performed by De Silva (2016), 66 patients listened to music during a colonoscopy in addition to standard treatment, and 67 patients received standard treatment only. Pain perceived by the patient during the procedure was reported on a 10-point VAS scale. Patients who listened to music reported a median pain intensity of 3 (IQR 2-4), while patients in the control group reported a pain intensity of 5 (IQR 3-8). This means that patients who listened to music had a lower pain score. This difference was clinically relevant.

In the RCT performed by Ebrahimi (2020), 35 patients listened to music during invasive coronary angiography without preplanned standard conscious sedation, and 37 patients received standard conscious sedation. Patients reported the periprocedural pain levels according to the Wong-Baker Faces analog pain rating scale. Patients who listened to music reported a mean pain of 0.96 (SD 1.40), whilst patients in the standard sedation group reported a mean pain of 0.92 (SD 2.18). The mean difference was 0.04 (95% CI -0.59 to 0.17). This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

In the RCT performed by Kang (2006), 20 patients listened to music during a total knee replacement, and 20 patients received standard care. Patients reported their postprocedure pain levels based on a 100-point VAS scale. Patients who listened to music reported a median pain level of 10 (IQR 0 to 66), patients in the control group reported a median pain level of 23 (IQR 0 to 70). This means that patients in the intervention group had a lower median pain score compared to the control group. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

In the RCT performed by Sjölander (2019), 68 patients received video distraction during colonoscopy, and 69 patients did not receive video distraction. The pain score was reported on a 10-point VAS scale, 15 minutes after the procedure. Patients who received distraction reported a mean pain intensity of 0.87 (SEM 0.17) and patients who did not receive distraction reported a mean pain intensity of 0.82 (SEM 0.17). This means that patients in the distraction group had on average a higher pain score (mean difference 0.05, 95% CI -0.42 to 0.52). However, this difference was not considered clinically relevant.

In the RCT performed by De Silva (2016), 67 patients watched a movie during a colonoscopy in addition to standard treatment, and 67 patients received standard treatment only. Pain was reported on a 10-point VAS scale. Patients who watched a movie reported a pain intensity of 4 (IQR 2-6), while patients in the control group reported a pain intensity of 5 (IQR 3-8). This means that patients who watched a movie have a lower pain score. This difference was clinically relevant.

Procedure duration (important)

This outcome measure was reported in eight studies (Akdoğan, 2021; Bechtold, 2006; De Silva, 2016; Fang, 2016; Kang, 2006; Kukreja, 2020; Kulkarni, 2012; Moon, 2018; Wang, 2014).

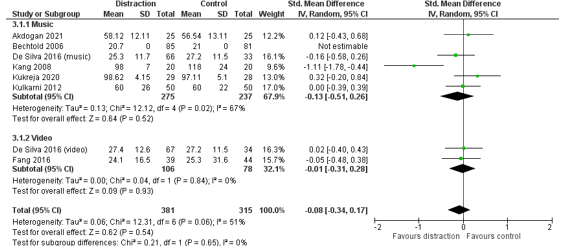

In total, 381 patients had distraction during their procedure, and 315 patients received standard care (control group) (Figure 1). The pooled effect estimate was SMD -0.08 (95% CI -0.34 to 0.17) in favour of distraction. This effect is somewhat larger in the subgroup of music distraction (SMD -0.13, 95% CI -0.51 to 0.26). This means that distraction, and specifically music distraction, results in a slightly shorter procedure duration, but the effect is small.

Figure 1. Outcome measure procedure duration for het comparison distraction versus standard care

Z: p-value pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Wang (2014) did not report individual study data or the number of patients included in their meta-analysis. They included nine studies in their meta-analysis and report a shorter procedure duration in the intervention group, compared to the control group (WMD -0.88, 95% CI -2.52 to 0.75), however the effect is small.

Moon (2018) did not report the mean procedure duration with standard deviation, and was therefore not included in this meta-analysis. In the RCT performed by Moon (2018), 18 patients received virtual reality distraction during endoscopic prostatectomy under spinal anesthesia, and 19 patients received pharmacological sedation. The procedure took 40 minutes in the VR group (IQR 35 to 75) and 45 minutes in the control group (IQR 30 to 60). This means that the procedure took 5 minutes shorter when patients received VR distraction. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature (distraction)

Patient satisfaction (crucial)

The level of evidence regarding this outcome measure comes from randomized clinical trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because the studies were not blinded and lack of reporting individual study data and / or confidence intervals (risk of bias, 1 level); heterogeneity in study results (inconsistency, 1 level). The level of evidence is low.

Pain (crucial)

The level of evidence regarding this outcome measure comes from randomized clinical trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because the studies were not blinded (risk of bias, 1 level); heterogeneity in study results (inconsistency, 1 level); and because the confidence intervals of the control and intervention group show a great amount of overlap (imprecision, 1 level). The level of evidence is very low.

Procedure duration (important)

The level of evidence regarding this outcome measure comes from randomized clinical trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of limitations in study design (risk of bias, 1 level) and heterogeneity in study results (inconsistency, 1 level).

2. Breathing exercises, relaxation techniques

None of the studies investigated effects of breathing exercises or relaxation techniques during/preceding PSA in patients that (will) undergo PSA.

3. Hypnosis, neuro-linguistic programming

Noergaard (2019) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine effects of hypnotic analgesia in management of pain, anxiety, analgesic consumption, procedure length and adverse events in adults (18 years or older) undergoing minimally invasive procedures. Clinically controlled trials in which hypnosis was used together with pharmacological analgesia compared to pharmacological analgesia alone during invasive procedures were included. Several databases were searched for published and unpublished studies in July 2018, including MEDLINE via PubMed, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, JBI Library, Scopus, Swemed+ and PsycINFO. Ten studies were included with a total sample size of 1,365 participants. Nine RCTs (Hizli, 2015; Lang, 2000, 2006, 2008; Lang, Joyce, Spiegel, Hamilton, & Lee, 1996; Marc, 2008, 2007; Shenefelt, 2013; Slack, 2009) and one quasi‐experimental study were included (Norgaard, 2013). The studies were published between 1996–2015 from four different countries: Six from the USA, two from Canada, one from Turkey and one from Denmark. The procedures in the studies included first‐trimester pregnancy termination, needle myography, biopsies, tumor treatments, angiographies, ablations, and skin lesion excisions. In all studies, patients were conscious during the procedure. Hypnotic analgesia was compared to standard care in all studies. In five studies, an extra arm in the randomization process was used, which was not included in the review: empathetic attention behavior, recorded hypnosis, or hypnosis without pain suggestion, respectively. Duration of the intervention differed between the studies but the content of the intervention was comparable, since all studies used an induction, guided imagery with analgesia suggestions and progressive muscle relaxation. In five studies, the intervention was provided periprocedural, in three studies the intervention started up to 20 min before the procedure and lasted throughout the procedure, and in two studies the intervention was provided before the procedure for 10–20 min and not during the procedure. In one study, participants listened to a 20‐min audio program, using a CD player with headphones. The intervention was provided to patients by a research assistant or an extra physician in all but one study. In one study, the intervention was provided by one of the procedure nurses in the procedure room. Risk of bias was assessed by the authors using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. Overall risk of bias across studies was moderate to high, due to performance and detection bias, which occurred in most of the studies. The reported outcome measures in the study were: pain, sedative dose, and procedure duration.

Izanloo (2015) performed a quasi-experimental trial (open-label, simple randomization) on the effects of conversational hypnosis compared with a control group receiving standard care on anxiety, endoscopy-related complications, and patient satisfaction during upper GI endoscopy. The study was conducted at the endoscopy unit of Razavi hospital in Mashhad, Iran between October and January 2013. In both groups, patients were sedated with 30-50 mg propofol until the desired level of sedation was achieved. In addition, continuous infusions of 100 - 300 mg/h were administered. The conversational hypnosis group consisted of 93 patients with a mean age of 50.46 (SD: 13.12) years. The control group consisted of 47 patients with a mean age of 54.89 (SD: 14.26) years. Outcome measures were: systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean blood pressure, pulse oximetry, heart rate, questionnaires of vital signs, degree of pain, satisfaction from the procedure (10-point scale), nausea, vomiting, and hiccups. All measures were collected before and after the procedure. The study has a high risk of performance bias. The reported outcome measures in the study were: patient satisfaction and pain.

Mackey (2018) performed a RCTs on the effects of hypnosis as an adjunct to intravenous sedation in patients between 18 and 25 years old undergoing third molar extraction in an outpatient setting (dental office) in Pennsylvania, USA. In total, 143 patients were randomly assigned to the treatment or control group. The treatment group consisted of 71 patients who listened to a rapid conversational induction and therapeutic suggestions via headphones throughout the entire surgical procedure along with a standard sedation dose of intravenous anesthetic. Standard sedation consisted of 50 mcg Fentanyl, 3 mg Midazolam, and 100 mg Propofol. This was given intravenously along with 8 mg Decadron. The control group consisted of 72 patients. The control patients also received intravenous anesthesia but listened to music without any hypnotic intervention. Mean age was not reported per group. Twenty-four patients were excluded for having a body weight greater than 100 kg (n=8), for having previous hypnotic experience (n=6), or because they were younger than 18 or older than 25 years old (n=10). The study has a high risk of performance bias. The reported outcome measures in the study were: pain and sedation dose.

Results (hypnosis, NLP etc)

Patient satisfaction (crucial)

None of the included studies reported the outcome measure patient satisfaction.

Pain (crucial)

The outcome measure pain was reported in three studies (Izanloo, 2015; Mackey, 2018; Noergaard, 2019).

In the RCT performed by Izanloo (2015), 93 patients received hypnosis in addition to standard treatment and 47 patients received standard treatment alone. Pain was collected based on a 10-point scale (0-10). Patients who received hypnosis reported a mean pain score of 0.28 (SD 0.89), patients who received standard treatment reported a mean pain score of 0.49 (SD 1.17). The mean difference is 0.21 (95% CI -0.17 to 0.59), in favour of standard treatment with hypnosis. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

In the RCT performed by Mackey (2018) 71 patients received hypnosis in addition to standard treatment and 72 patients received standard treatment only. Patients that underwent hypnosis had a mean pain score of 2.69 (SD 1.56) during the procedure, while patients who only received standard care received had a mean pain score of 4.49 (SD 1.46). The mean difference was 1.80 (95% CI 1.30 to 2.30), in favour of the intervention group. This is considered clinically relevant.

Ten studies included in the SR from Noergaard (2019) reported pain. Even though nine out of ten studies used the same validated instrument to assess pain intensity (VAS scale 0-10 or 0-100), the results were calculated and reported differently, precluding a meta-analysis. Results of patient-related pain intensity were difficult to summarize because the pain was measured at different times. In eight individual studies, no statistically significant differences in patient-related pain intensity between control and intervention group in general were found. The results of the individual studies are shown in the Evidence Table. The studies indicate less pain intensity in the groups of patients that received hypnosis, however the differences were small. This is not considered clinically relevant.

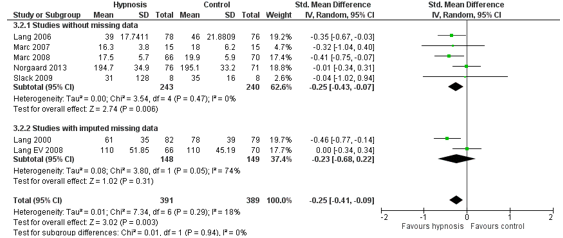

Procedure duration (important)

The outcome measure procedure duration was reported in one SR (Noergaard, 2019). This SR included seven RCT’s in the meta-analysis. In total, 391 patients received hypnotic analgesia in addition to standard care (experimental group), and 389 patients received standard care only (control group). The heterogeneity between these studies was 18% (Figure 2). The pooled effect estimate was SMD -0.25 (95% CI -0.41 to – 0.09) in favour of the addition of hypnotic analgesia. This means that the addition of hypnotic analgesia results in a shorter procedure duration, but the effect is small.

Figure 2. Outcome measure procedure duration hypnotic analgesia in addition to standard care versus standard care alone.

Z: p-value pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Level of evidence of the literature (hypnosis, NLP etc)

Patient satisfaction (crucial)

The level of evidence could not be graded as this outcome measure was not reported in the included studies.

Pain(crucial)

The level of evidence regarding this outcome measure comes from randomized clinical trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of lack of blinding (risk of bias, 1 level); differences in included patients and reporting of outcome measures (inconsistency, 1 level); and because the confidence interval exceeds the values of clinical relevance (imprecision, 1 level). The level of evidence is very low.

Procedure duration (important)

The level of evidence regarding this outcome measure comes from randomized clinical trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of lack of blinding (risk of bias, 1 level); and because the effect size exceeds the boundaries of clinical relevance (imprecision, 1 level). The level of evidence is low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of non-pharmacological interventions during/preceding PSA in patients that (will) undergo PSA on effectiveness of PSA and patient satisfaction?

| P (Patients): | adult patients undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) (>18 years old) |

| I (Intervention): |

non-pharmacological intervention (instead of or in addition to pharmacological intervention), namely:

|

| C (Comparison): | pharmacological intervention only (no non-pharmacological intervention), standard care, or placebo intervention (potentially in addition to pharmacological intervention) |

| O (Outcomes): | patient satisfaction, pain, procedure duration |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered patient satisfaction and pain as critical outcome measures for decision making. Procedure duration and sedation dose were considered as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not further define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined the following differences as minimal clinically important differences:

- Patient satisfaction: 10% for continuous outcomes, 1 point on 7-point Likert, 25% difference in relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes.

- Pain: 10% for continuous outcomes (VAS 1/10 or 10/100)

- Procedure duration: to decide by the health care professional, based on type of procedure; for the current summary, 25% of the procedure time was used

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until April 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. Studies published before 2005 were excluded. The systematic literature search resulted in 817 hits.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials on non-pharmacological interventions and sedation in adults. In total, 44 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 28 studies were excluded (see table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 16 studies were included.

Results

Sixteen studies were included in the analysis of the literature: two systematic reviews and seventeen randomized clinical trials. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Akdogan A, Arslan M, Erceyes N. The effect of sufi music on sedation in patients under spinal anesthesia during orthopedic surgery. Ann Clin Anal Med 2021;12(2):204-207

- Bashiri M, Akçal? D, Co?kun D, Cindoruk M, Dikmen A, Çifdalöz BU. Evaluation of pain and patient satisfaction by music therapy in patients with endoscopy/colonoscopy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018 Sep;29(5):574-579. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2018.18200. PMID: 30260780; PMCID: PMC6284616.

- Bechtold ML, Perez RA, Puli SR, Marshall JB. Effect of music on patients undergoing outpatient colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Dec 7;12(45):7309-12. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7309. PMID: 17143946; PMCID: PMC4087488.

- De Silva AP, Niriella MA, Nandamuni Y, Nanayakkara SD, Perera KR, Kodisinghe SK, Subasinghe KC, Pathmeswaran A, de Silva HJ. Effect of audio and visual distraction on patients undergoing colonoscopy: a randomized controlled study. Endosc Int Open. 2016 Nov;4(11):E1211-E1214. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-117630. Epub 2016 Oct 20. PMID: 27853748; PMCID: PMC5110335.

- Ebrahimi R, Shroyer AL, Dennis P, Currier J, Lendvai Wischik D. Music Can Reduce the Need for Pharmacologic Conscious Sedation During Invasive Coronary Angiography. J Invasive Cardiol. 2020 Nov;32(11):440-444. Epub 2020 Oct 22. PMID: 33087584.

- Fang AS, Movva L, Ahmed S, Waldman D, Xue J. Clinical Efficacy, Safety, and Feasibility of Using Video Glasses during Interventional Radiologic Procedures: A Randomized Trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016 Feb;27(2):260-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.09.023. Epub 2015 Nov 25. PMID: 26626861.

- Huang MY, Scharf S, Chan PY. Effects of immersive virtual reality therapy on intravenouspatient-controlled sedation during orthopaedic surgery under regional anesthesia: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2020 Feb 24;15(2):e0229320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229320. PMID: 32092098; PMCID: PMC7039521.

- Izanloo A, Fathi M, Izanloo S, Vosooghinia H, Hashemian A, Sadrzadeh SM, Ghaffarzadehgan K. Efficacy of Conversational Hypnosis and Propofol in Reducing Adverse Effects of Endoscopy. Anesth Pain Med. 2015 Oct 24;5(5):e27695. doi: 10.5812/aapm.27695. PMID: 26587402; PMCID: PMC4644316.

- Kang JG, Lee JJ, Kim DM, Kim JA, Kim CS, Hahm TS, Lee BD. Blocking noise but not music lowers bispectral index scores during sedation in noisy operating rooms. J Clin Anesth. 2008 Feb;20(1):12-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2007.06.005. PMID: 18346603.

- Kukreja P, Talbott K, MacBeth L, Ghanem E, Sturdivant AB, Woods A, Potter WA, Kalagara H. Effects of Music Therapy During Total Knee Arthroplasty Under Spinal Anesthesia: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Cureus. 2020 Mar 24;12(3):e7396. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7396. PMID: 32337122; PMCID: PMC7179990.

- Kulkarni S, Johnson PC, Kettles S, Kasthuri RS. Music during interventional radiological procedures, effect on sedation, pain and anxiety: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Radiol. 2012 Aug;85(1016):1059-63. doi: 10.1259/bjr/71897605. Epub 2012 Mar 14. PMID: 22422386; PMCID: PMC3587064.

- Mackey EF. An Extension Study Using Hypnotic Suggestion as an Adjunct to Intravenous Sedation. Am J Clin Hypn. 2018 Apr;60(4):378-385. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2017.1416279. Erratum in: Am J Clin Hypn. 2020 Apr;62(4):427-428. PMID: 29485375.

- Moon JY, Shin J, Chung J, Ji SH, Ro S, Kim WH. Virtual Reality Distraction during Endoscopic Urologic Surgery under Spinal Anesthesia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2018 Dec 20;8(1):2. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010002. PMID: 30577461; PMCID: PMC6352098.

- Noergaard MW, Håkonsen SJ, Bjerrum M, Pedersen PU. The effectiveness of hypnotic analgesia in the management of procedural pain in minimally invasive procedures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2019 Dec;28(23-24):4207-4224. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15025. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31410922.

- Sjölander A, Jakobsson Ung E, Theorell T, Nilsson Å, Ung KA. Hospital Design with Nature Films Reduces Stress-Related Variables in Patients Undergoing Colonoscopy. HERD. 2019 Oct;12(4):186-196. doi: 10.1177/1937586719837754. Epub 2019 Mar 26. PMID: 30913926.

- Wang MC, Zhang LY, Zhang YL, Zhang YW, Xu XD, Zhang YC. Effect of music in endoscopy procedures: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Med. 2014 Oct;15(10):1786-94. doi: 10.1111/pme.12514. Epub 2014 Aug 19. PMID: 25139786.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Noergaard, 2019

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs and nonrandomized controlled trials were included in this review.

Literature search up to July 2018.

A: Lang, 2000 B: Lang, 2008 C: Lang, 1996 D: Lang, 2006 E: Marc, 2008 F: Marc, 2007 G: Slack, 2009 H: Shenefelt, 2013 I: Hizli, 2015 J: Norgaard, 2013

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: outpatients, USA B: outpatients, USA C: inpatients, USA D: outpatients, USA E: outpatients, Canada F: outpatients, Canada G: outpatients, USA H: outpatients, USA I: outpatients, Turkey J: inpatients, Denmark

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: None identified.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - Quantitative randomised or nonrandomised controlled trials in English, Danish, Swedish and Norwegian. - Studies with adult patients (18 years and older) - interventions: studies that evaluated hypnotic analgesia provided together with usual pain medication used during minimally invasive procedures. - hypnosis could be provided either face to face or as a pre-recorded version without limits on the length of the intervention. - Comparators in the included studies were usual analgesics or usual care typical for the institution. - studies

Exclusion criteria SR: Studies were excluded if hypnotic analgesia had been used during open surgery, during dental procedures, labour, during burn treatment and other noninvasive procedures. In addition, studies where hypnotic analgesia was used for children and adolescents were excluded.

10 studies included.

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients A: 241 B: 201 C: 30 D: 236 E: 350 F: 30 G: 26 H: 39 I: 64 J: 147

Age (years) A: median 56 B: median 50 C: mean 66.5 D: median 49 E: mean 26.3/24.2 F: mean 27.0/25.6 G: mean 51 H: 59.2/66.1/55.9 I: 63.5 J: 59.9 / 59.5

Sex (% male): A: 47% B: 36.8% C: 100% D: 0.5% E: 0% F: 0% G: 65.4% H: 59% I: 100% J: 71% / 66%

Groups comparable at baseline? In all studies, the intervention and control group were similar and treated identically except for the exposure of the intervention. |

Describe intervention:

A: self-hypnotic relaxation together with empathic attentive behaviour in addition to control, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

B: self-hypnotic relaxation together with empathic attentive behaviour in addition to control, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

C: hypnosis with combined elements of relaxation training and guided imagery for induction of self-hypnotic process, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

D: self-hypnotic relaxation together with empathic attentive behaviour

E: hypnotic relaxation, session 20 minutes before the procedure guided by 1 or 2 hypnotherapists, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

F: hypnotic relaxation session 20 minutes before the procedure and throughout the procedure guided by hypnotist practitioner, access to pain medication (not described), access to N2O.

G: listened to an audio programme for 20 minutes in duration with hypnotic induction with analgesic suggestion just before the procedure, no access to pain medication.

H: hypnotic induction followed by self-guided imagery from the start and throughout the procedure, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

I: hypnosis sessions were standardised to last 10 minutes before the procedure guided by a physician.

J: structured attentive behaviour together with standardized guidance to self-hypnotic relaxation, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

|

Describe control:

A: usual care, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

B: usual care, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

C: usual care, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

D: usual care, no pain medication used but local anaesthetic

E: usual care, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

F: usual care, access to pain medication (not described), access to N2O

G: usual care, no access to pain medication

H: usual care, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam

I: usual care

J: usual care, access to intravenous analgesia with Fentanyl and Midazolam (patient push button to require pain medication)

|

End-point of follow-up: Not reported.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported.

|

Seven studies were included in the meta-analysis: Lang, 2000; Lang, 2006; Lang, 2008; Marc, 2008; Marc 2007; Norgaard, 2013; Slack, 2019.

Outcome measure-1: patient satisfaction Not reported.

Outcome measure-2: procedure duration Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.25 (CI 95%: -0.41, -0.09). favoring the intervention. Heterogeneity (I2): 18%

Outcome measure-3: pain/discomfort Results were calculated and reported differently even though nine out of ten studies used the same validated instrument to assess pain intensity; a VAS scale 0–10 or 0–100.

A: Lang (2000): Pain intensity: NRS -=10 every 15 minutes and calculation of slopes: slope 0.03 versus slope 0.09

B: Lang (2008) Pain intensity, NRS every 0-10 every 15 minutes and calculation in slopes; median (IQR): 15-30 minutes: 0 (0-2) versus 1 (0-3); and 30-45 minutes: 0 (0-2) versus 2 (0-4)

C: Lang (1996): pain intensity NRS 0-10 every 20 minutes; median; time average rating: intervention 1.2 (1.0-8.3) versus control 2.5 (1.0-6.3); max average rating intervention: 2.0 (0-10) versus 5.0 (2-9)

D: Lang (2006): pain intensity NRS every 10 minutes and calculation of slopes: slope 0.34 versus 0.53

E: Marc (2008): Pain intensity NRS 0-10 Pain I: 11.8 (17.4) vs. 12.9 (17.4) Pain II: 9.9 (17.0) vs. 13.6 (19.0) Pain III: 39.7 (25.4) vs. 42.1 (27.9) pain IV: 14.4 (19.5) vs. 16.2 (20.3)

F: Marc (2006) Not significant (no data)

G: Slack (2009): VAS 0-100, mean (SD) worst pain: 49 (30) vs 67 (25) average pain 25 (22) vs 35 (26)

H: Shenefelt (2013) Not significant (no data)

I: Hizli (2015) pain intensity (VAS 0-10) mean (range) postintervention, preprocedure 1 (0-8) versus 3 (0-9).

J: Norgaard (2013) number of spontaneous expressed pain: intervention mean 1.4 (SD 1.2) versus control mean 2.8 (SD 1.8)

Outcome measure-4: sedation dose In five out of ten studies, the amount of Fentanyl and Midazolam (pain medication) used periprocedural was measured as an outcome and was calculated to be significantly less in the intervention group compared to the control group (Lang, 2000, 2008, 1996; Marc, 2008; Norgaard, 2013). In all but one study, the results were reported without SD, precluding a meta-analysis.

Fentanyl µg/Midazolam mg A: mean 22.50/0.45 intervention versus 47.50/0.95 control. B: mean 50(25-100)/1(0.50-2) intervention versus 75 (37.50-125)/1.5(0.75-2.50) control. C: mean 7(0-75)/0.14(0-1.50) intervention versus mean 50.39(0-125)/1.05(0-2.50) control. E: mean 39.39/1.08 intervention versus mean 49.71/1.62 F: 36% (CI 95% 16–61) of patients in the hypnosis group chose N20 sedation periprocedural compared to 87% (CI 95% 61–97) in the control group (p < .01). J: mean 220.70 (93) /0 intervention versus 292 (107) / 0 control

The consumption of pain medication was reduced between 21%–86% in these five individual studies in the intervention group. |

Facultative:

The majority of the studies were evaluated weak. The overall risk of bias across studies evaluated moderate to high. The two most common risk of bias among the studies were performance and detection bias, which occurred in most of the studies. The nature of the intervention prohibited blinding of the treatment to the participants and the majority of the studies had weaknesses due to the criteria about blinding of those assessing outcomes.

|

|

Wang, 2014

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCT’s.

Literature search up to July 2013.

A: Bampton, 1997 B: Björkman, 2013 C: Chan, 2003 D: Chlan, 2000 E: Colt, 1999 F: Costa, 2020 G: Danhauer, 2007 H: Dubois, 1995 I: El-Hassan, 2009 J: Harikumar, 2006 K: Hayes, 2003 L: Kotwal, 1998 M: Lee, 2002 N: Lopez, 2004 O: Ovayolu, 2006 P: Palakanis, 1994 Q: Schiemann, 2002 R: Smolen, 2002 S: Triller, 2006 T: Uedo, 2004 U: Yeo, 2013

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: Australia B: Sweden C: China D: USA E: USA F: Italy G: USA H: USA I: UK J: Kerala K: USA L: India M: China N: Spain O: Turkey P: USA Q: Germany R: USA S: Slovenia T: Japan U: Korea

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: There is no any potential conflict of interest in the article. The study is not supported by any financial grants. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Patients undergoing various endoscopic examinations. Intervention and control as described in the next columns.

Exclusion criteria SR: Studies were excluded if the raw data could not be extracted.

21 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N intervention /control A: 28/31 B: 60/60 C: 112/108 D: 30/34 E: 30/30 F: 56/53 G: 56/58 H: 21/28 I: 92/88 J: 38/40 K: 100/98 L: 54/50 M: 55/55 N: 63/55 O: 30/30 P: 25/25 Q: 59/60 R: 16/16 S: 93/107 T: 15/14 U: 35/35

Age: A: >18 B: 18-80 C: 18-65 D: >18 E: >18 F: 18-75 G: 18-60 H: NR I: ≥18 J: 15-60 K: ≥18 L: NR M: 16-75 N: 18-75 O: 18-75 P: 20-76 Q: 18-80 R: >18 S: >18 T: 40-69 U: >20

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

All subjects in the intervention group listened to music before and/or during the procedure, played on a compact disc (CD) player or other modalities with or without earphones and the style of music was not

A: relaxation music, before and during procedure B: Sedative music, during procedure C: slow-rhythm music, during procedure D: self-selected music, during procedure E: self-selected music, during procedure F: self-selected music, during procedure G: relaxation music, during procedure H: new wave music, during procedure I: self-selected music, 15 minutes before the procedure J: self-selected music, during procedure K: self-selected music, 15 minutes before the procedure L: Indian classical music, before and during procedure M: self-selected music, during procedure N: classical tracks, during procedure O: Turkish classical music, before and during procedure P: sedative music, during procedure Q: self-selected music, during procedure R: self-selected music, during procedure S: self-selected music, during procedure T: easy listening style, during procedure U: classical music, before and during procedure

|

Describe control:

The usual care group underwent the procedure as typically conducted without music

|

End-point of follow-up: Not reported.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported

|

Outcome measure-1: patient satisfaction Satisfaction score was measured by different methods, and the SMD was used in this meta-analysis. Overall, the level of satisfaction was improved in the music group (SMD = 1.83, 95% CI [0.76, 2.91]).

Outcome measure-2: pain The overall effect of the meta-analysis based on the LAS favored music for pain reduction (WMD = - 1.53, 95% CI [- 2.53, - 0.53]).

utcome measure-3: procedure duration There was no significant difference in duration of procedure between groups (WMD = -0.08, 95% CI [- 2.52, 0.75]).

Outcome measure-3: sedation dose The meta-analysis showed that music did not reduce the dose used of sedative medications during examinations (WMD -0.53 (-1.39 to 0.33).

|

Facultative:

Our meta-analysis suggested that music may offer benefit for patients undergoing endoscopy.

Individual study results and forest plots are not reported in the study. |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Noergaard, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, all ten studies that met the criteria for this SR were included. |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes, JBI-MAStARI |

Yes

|

Yes

To minimise publication bias, we did a comprehensive search for unpublished or grey literature (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011) without finding any. |

No, only for the SR, not for the individual studies. |

|

Wang, 2014 |

Yes |

Yes |

No, potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection were not referenced with reasons. |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes, risk of bias tabel included for all studies. |

Unclear, they report that they use a random model when I² is > 50%.

The procedures and type of intervention have some differences. Subgroup analyses may have been more appropriate. |

Yes

Funnel plot was included. |

No, only for the SR, not for the individual studies. |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Akdoğan, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: None of the authors received any type of financial support that could be considered potential conflict of interest regarding the manuscript or its submission. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients in the ASA I-II risk group, aged 18-60, who will undergo elective non oncologic orthopedic surgery, with the approval of the local ethics committee and informed consent from the patients.

Exclusion criteria: Those who have hearing loss, are professional music practitioners, are using medications that can affect the hypothalamo-hypophyseal and sympathetic system. In addition, patients who did not like this type of music and stated that they did not want to listen were not included in the study.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 25 Control: 25

Important prognostic factors2:

Age (years): I: 41.96 (+/- 11.41) C: 43.00 (+/- 11.26)

Sex: F/M I: 11/14 C: 13/12

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

The patients were made listen to works from Turkish Sufi Music Hüseyni Mode with an mp3 player (SONY NVZ-B172), using headsets. The patients were told to adjust the volume of the music according to their preferences.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No music. |

Length of follow-up: 30 minutes postoperative.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: None.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Procedure duration: I: 58.12 (+/- 12.11) min. C: 56.54 (+/- 13.11) min. |

|

|

Bashiri, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients who were 18-70 years old, American Anesthesiologist Association (ASA) status I-III, and scheduled For endoscopy/ colonoscopy were included in the study after verbal and written approval was obtained.

Exclusion criteria: Patients scheduled for endoscopic ultrasound or endoscopic retrograde colangiopancreaticography and having difficulty in communication were excluded from the study.

N total at baseline: Group 1: 25 Group 2: 33 Group 3: 55 Group 4: 41

Important prognostic factors2: Age median (min-max) Group 1: 46 (28-69) Group 2: 44 (28-65) Group 3: 44 (28-60) Group 4: 42 (24-65)

Male/female Group 1: 4/21 Group 2: 13/21 Group 3: 26/29 Group 4: 15/26

Groups comparable at baseline? There were more women than men in all groups.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

In the music group, patients listened to a 30-minute recording of their favorite music.

Group 2) conscious sedation Group 4) deep sedation

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

In the control group, the headphone was on without any music.

Group 1) conscious sedation Group 3) deep sedation

|

Length of follow-up: Until after the intervention.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Patient satisfaction: Satisfaction was assessed by Likert scale (1, very satisfied; 2, satisfied; 3, undetermined; and 4, not satisfied). Data was not provided.

In the sedation and music groups, patients were satisfied with their procedure and declared that they would prefer the same method for their next endoscopy. No significant difference was found in patient satisfaction between the groups.

Sedation dose (propofol (mg)): Group 3: 204.54 (SD 42.24) Group 4: 146.34 (SD 32.38)

Sedation dose (midazolam (mg)): Group 3: 2 (SD 0) Group 4: 1.3 (SD 0.48)

Sedation dose (ketamine (mg)): Group 3: 19.63 (SD 2.69) Group 4: 16.12 (SD 4.45)

Data was not provided for Group 1 and 2.

|

The study included conscious and deep sedation. |

|

Bechtold, 2006 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria: Patients presenting for elective outpatient colonoscopy.

Exclusion criteria: history of prior colon resection, patients scheduled to undergo same-day esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, and inability to give informed consent.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 85 Control: 81

Important prognostic factors2: Age I: 58.5 C: 54.1

Sex: I: 51.8 % F C: 48.1 % F

Groups comparable at baseline? They were similar in terms of gender (51.8% females for the music group vs 48.1% for the non-music group, P = 0.64) and history of prior colonoscopy (36.5% vs 30.9%, P = 0.45). The music group was slightly older (58.5 years vs 54.1 years, P = 0.036), and reported less pre-procedural anxiety (36.3-mm vs 45.1-mm, borderline significance at P = 0.053). |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

In the music group, a CD player was playing relaxing music upon the entrance of the patient into the procedure room. We played the same music for all patients in the music group: “Watermark” by Enya (Reprise Records, a Time Warner Company, 1988), which contains 12 tracks (ranging from 1:59 to 4:25 in length). The CD was set on repeat.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

No music. |

Length of follow-up: Post procedure.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Experience I scale (1-4): I: 2 C: 2

Experience 2 scale (1-5) I: 1 C: 2

Experience 3 scale (100 mm scale) I: 22.5 C: 28.1

Pain: (100 mm VAS scale) I: 25.3 mm C: 25.4 mm

Procedure time: I: 20.7 minutes C: 21 minutes

Sedation dose (Meperidine) I: 57 mg C: 54.6 mg

Sedation dose (Midazolam) I: 1.92 mg C: 1.85 mg

|

|

|

De Silva, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: teaching hospital, Sri Lanka.

Funding and conflicts of interest: none. |

Inclusion criteria: Consecutive patients with an indication to undergo elective day-case colonoscopy for medical indications were enrolled in the study in the absence of exclusion criteria.

Exclusion criteria: The exclusion criteria included visual or hearing impairment, allergies or hypersensitivity to premedication, patients who had had abdominal surgery or colectomy, personal history of anxiety or psychiatric disorder, and pregnancy.

N total at baseline: Intervention AD: 66 Intervention VD: 67 Control: 67

Important prognostic factors2: Age (years) I - AD: 54.4 (SD 12.5) I – VD: 51.5 (SD 14.6) C: 56.5 (SD 13.8)

Sex: I - AD: 49% M I – VD: 64% M C: 52% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

All patients were administered midazolam and pethidine for sedation and analgesia, respectively, irrespective of the study group to which they were allocated.

Audio distraction (AD): The AD group was allowed to listen to the music of their choice during colonoscopy. The AD group listened to their choice of music through the SONY head mounted set.

Visual distraction: The VD group was allowed to watch a film of their choice with sound using a SONY head mounted display.

The duration of the movie or video clip and the play list were more than 20 minutes to cover the maximum predicted duration for the colonoscopy. |

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

All patients were administered midazolam and pethidine for sedation and analgesia, respectively, irrespective of the study group to which they were allocated.

The control group only received standard sedation during the colonoscopy. The control group had the SONY head mounted set on but with nothing playing for the duration of the procedure. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: No loss to follow-up.

Incomplete outcome data: Data was complete.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain (10-point VAS scale): Median + IQR AD: 3 (2-4) VD: 4 (2-6) C:5 (3-8)

Duration of the procedure: Total procedure time (SD) in minutes (from setting up of intervention and premedication to recovery from premedication) was similar among the three groups: 25.3 (11.7) for AD, 27.4 (12.6) for VD, 27.2 (11.5) for group C, respectively (P=0.593).

Sedation dose (pethidine): AD: 10 (5-15) VD: 10 (10-15) C: 15 (5-20)

Sedation dose (midazolam): AD: 1.5 (1.0 – 2.0) VD: 1.5 (1.5 – 2.0) C: 2 (1.0 – 2.5)

|

|

|

Ebrahimi, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT (pilot)

Setting and country: USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) age >18 years old; (2) non-emergent ICA; and (3) ability and willingness to participate in the study and sign the informed consent form

Exclusion criteria: (1) acute myocardial infarction requiring emergency ICA; (2) documented history of major hearing problems or deafness; (3) contraindication to SCS medications; and (4) unwillingness to comply with study procedures and requirements.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 35 Control: 37

Important prognostic factors2: Age, years (SD) I: 69.57 (8.92) C: 68.51 (6.48)

Sex: I: 2.9% F C: 8.1% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes.

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

For those randomized to the Music group, music was started approximately 20 minutes prior to arrival in the cardiac catheterization laboratory (CCL), and continued throughout the procedure and during the recovery period up to 1 hour. Choice of music was based on each subject’s stated preferences (specific genre, artists, or songs were searched in one of the mainstream digital music libraries). Music was delivered through a portable media player with single-use, disposable ear buds. The appropriate volume was adjusted by CCL nursing staff per patient request. Ear buds were used in only 1 ear of each subject to ensure adequate communication between the subject and the attending provider and CCL staff.