Propofol

Uitgangsvraag

Aanbeveling

Maak de keuze voor target-controlled infusion, manual infusion of intermitterende bolustoediening van propofol voor matig/diepe sedatie op basis van ervaring, beschikbaarheid en lokale protocollen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In deze literatuursamenvatting is gekeken naar het gebruik van target-controlled infusion (TCI) ten opzichte van intermitterende bolussen of continue intraveneuze toediening bij propofol sedatie ten behoeve van PSA. Tijd tot sedatie en propofol dosering werden door de werkgroep als cruciale uitkomsten gezien, hypotensie, respiratoire depressie en patiënttevredenheid als belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

De bewijskracht van de geïncludeerde studies was laag tot zeer laag. De studies hadden methodologische beperkingen. Procedures met betrekking tot de randomisatie werden in een aantal gevallen niet uitgevoerd of niet (voldoende) beschreven, blindering vond niet altijd plaats en in één studie werden niet alle studie-uitkomsten beschreven. Daarnaast was er sprake van inconsistentie van studieresultaten en includeerden de studies relatief kleine aantallen patiënten. Ook dient opgemerkt te worden dat de ASA-klasse in het merendeel van de trials ASA I-II was, en dat ouderen in het merendeel van de trials ondervertegenwoordigd zijn.

De literatuur over de cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘tijd tot sedatie’, suggereert dat TCI met propofol mogelijk niet leidt tot een verschil in tijd tot sedatie in vergelijking met het toedienen van propofol met bolussen of continue intraveneuze toediening.

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘propofol dosering’ was de bewijskracht zeer laag, waardoor op basis van de literatuur geen uitspraak kan worden gedaan over het mogelijke effect van toedieningswijze op deze uitkomstmaat.

De patiënttevredenheid is mogelijk vergelijkbaar na TCI met propofol in vergelijking met het toedienen van propofol met bolussen of continue intraveneuze toediening. De literatuur was onzeker over het effect van TCI dan wel manuele toediening op hypotensie en respiratoire depressie.

Deze bevindingen impliceren dat er op basis van de gevonden literatuur geen voorkeur is voor het gebruik van TCI ten opzichte van intermitterende bolussen of continue intraveneuze toediening voor propofol sedatie bij volwassenen.

Bovengenoemde bevindingen geven aan dat er geen evident verschil bestaat tussen verschillende toedieningsvormen van propofol bij matige tot diepe sedatie. Ondanks de lage bewijsgraad lijken er wel iets meer respiratoire complicaties te zijn bij de manuele vorm van propofol toediening. Dit zal zeker te verklaren zijn doordat er gewerkt wordt met bolussen en er bij TCI veel geleidelijker propofol wordt toegediend. Mogelijk dat baserend hierop TCI in gebruik voor de sedatiedeskundige makkelijker kan zijn. Chang (2013) geeft aan dat patiënten sneller wakker zijn na gebruik TCI en in 2015 geeft Chang (2013) aan dat er mogelijk wel een betere sedatie kwaliteit zou zijn, echter is dit verschil niet significant. Franzen (2016) zegt dat bij gebruik TCI minder luchtweg en hemodynamische interventies nodig zijn, wat een voordeel kan zijn als een sedatiedeskundige alleen op een buitenlocatie werkzaam is.

Echter gezien bovenstaande is er geen duidelijke voorkeur aan te geven vanuit de werkgroep en kan de gebruiker kiezen voor datgenen waarmee hij of zij de meeste ervaring heeft.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Gezien de uitkomstmaten van de RCT’s lijken de patiënten over het algemeen tevreden met alle genoemde toedieningsvormen. Bespreek de voor- en nadelen van de verschillende toedieningsvormen met de patiënt en maak samen met de patiënt een keuze over de toedieningsvorm, rekening houdend met ervaring, beschikbaarheid en lokale protocollen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Met betrekking tot de kosten moet de aanschaf van speciale TCI perfusorpompen meegenomen worden in de overwegingen. De kosten voor de medicatie zelf zijn vergelijkbaar, echter voor TCI zijn duurdere pompen nodig.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Met betrekking tot bovenstaande vragen verwacht de werkgroep geen extra maatregelen, behoudens de aanschaf van TCI perfusorpompen wanneer men besluit over te gaan op deze toedieningsvorm. TCI is een toedieningsvorm die veel toegepast wordt op het operatiecomplex, maar zeker niet in alle ziekenhuizen of zorginstellingen. Wanneer er geen bekendheid is met TCI toedieningsvorm zal er speciale scholing georganiseerd moeten worden voor de betrokken sedatiedeskundigen. Voor de patiënt geeft de sedatietoedieningsvorm geen verandering in comfort en tevredenheid.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de gevonden literatuur is er geen voorkeur voor het gebruik van TCI ten opzichte van intermitterende bolussen of continue intraveneuze toediening voor propofol sedatie bij volwassenen.

Aanname is dat in het merendeel van de klinieken de matige tot diepe sedatie wordt gedaan middels continue intraveneuze toediening van propofol of intermitterende bolussen propofol. Echter de TCI is een mooi alternatief waarbij de effectiviteit, veiligheid en patiënt tevredenheid vergelijkbaar zijn met andere toedieningen. Mogelijk dat minder interventies en een snellere recovery nog zouden kunnen pleiten voor het gebruik van target-controlled infusion. De kosten voor de medicatie zelf zijn vergelijkbaar, echter voor TCI zijn duurdere pompen nodig. Tevens is scholing nodig wanneer er geen bekendheid is met het TCI -principe.

Gebruik van target-controlled infusion met propofol is een even effectieve en even veilige methode voor het geven van matig tot diepe sedatie bij PSA vergeleken met manual infusion of intermitterende bolustoediening. De keuze is daarom afhankelijk van de beschikbaarheid van de pompen en de voorkeur van de behandelaar.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Propofol is het meest gebruikt sedativum in de anesthesiologische praktijk. Ook de matig tot diepe sedaties vinden met name plaats door middel van propofol, met of zonder opioïden en/of ketamine. In deskundige handen lijkt het dan het meest veilige middel waarmee veel ervaring is opgedaan. De werkgroep is van mening dat propofol zijn plaats verdient als sedativum voor matig tot diepe sedaties. Propofol is een middel met een smalle therapeutische breedte, waardoor de kans op (pulmonale en cardiovasculaire) bijwerkingen of complicaties aanwezig is. Daarnaast zijn er diverse manieren om propofol toe te dienen, denk aan intermitterende bolussen, continue intraveneuze toediening, target controlled infusion en patiënt controlled infusion.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

Target-controlled infusion of propofol may result in little to no difference in time to sedation compared with manual administration of propofol in an adult population undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia.

Sources: Chiang (2013); Vučićević (2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of target-controlled infusion of propofol on propofol-dose compared with manual administration of propofol in an adult population undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia

Sources: Chang (2015); Chiang (2013); De Vito (2017); Franzen (2016); Sakaguchi (2011); Vučićević (2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of target-controlled infusion of propofol on the occurrence of hypotension compared with manual administration of propofol in an adult population undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia.

Sources: Chang (2015); De Vito (2017); Franzen (2016); Sakaguchi (2011); Wang (2016) |

|

Very Low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of target-controlled infusion of propofol on the occurrence of respiratory depression when compared with manual administration of propofol in an adult population undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia.

Sources: Chang (2015); Chiang (2013); De Vito (2017); Franzen (2016); Sakaguchi (2011); Wang (2016) |

|

Low GRADE |

Target-controlled infusion of propofol may result in little to no difference in patient satisfaction when compared with manual administration of propofol in an adult population undergoing procedural sedation and analgesia.

Sources: Chiang (2013); Wang (2016) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Chang (2015) performed an RCT comparing TCI with manual administration of propofol in 100 patients undergoing upper/lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. A total of 50 patients was included in the intervention group (age 50.0 ± 13.5 years, 46% males), 50 patients were included in the control group (age 51.4 ± 14.2 years, 50% males). The TCI was programmed with an initial target effect-site concentration of 4 μg/mL of propofol. After loss of consciousness the target effect-site concentration was changed to 2.5 μg/mL. Patients in the control group received doses of 20-30 mg propofol to reach the desired sedation effect. Thereafter propofol was empirically administered by the nurse anaesthetist. The outcomes assessed were propofol consumption, hypotension, and respiratory depression.

Chiang (2013) performed an RCT comparing TCI with manual controlled infusion (MCI) of propofol in 220 patients undergoing bidirectional endoscopy. A total of 110 patients was included in the intervention group (age 50.5 ± 11.4 years, 55% males), 110 patients were included in the control group (age 51.1 ± 10.2 years, 54% males). The TCI was programmed at a target effect-site concentration of 4 μg/mL of propofol. Patients in the control group received a dose of 1.5 mg/kg propofol followed by maintenance doses of 6-12 mg/kg. The outcomes assessed were time to sedation, propofol consumption, respiratory depression, and patient satisfaction.

De Vito (2017) performed an RCT comparing TCI with MCI of propofol in 173 patients undergoing sleep endoscopy. A total of 123 patients was included in the intervention group (age 51 ± 11 years, 91% males), 50 patients were included in the control group (age 48 ± 12 years, 86% males). The TCI starting dose was 1.5 µg/mL of propofol with increments of 0.2 µg/mL when new cerebral concentration of propofol was reached. Patients in the control group received 1 mg/kg propofol as induction bolus and 20 mg boluses were repeated every 2 minutes. The outcomes assessed were propofol consumption, hypotension, and respiratory depression.

Franzen (2016) performed a non-inferiority RCT comparing TCI with fractionated propofol administration in 77 patients undergoing flexible bronchoscopy. A total of 39 patients was included in the intervention group (age 65.6 ± 11.3 years, 63% males), 38 patients were included in the control group (age 64.0 ± 11.6 years, 59% males). The TCI was programmed with an initial targeted effect-site concentration 2.5 µg/mL propofol. Thereafter, the target effect-site concentration could be adjusted depending on the clinical effect by increments of 0.2 µg/mL. Patients in the control group received an initial bolus of 30-40 mg of propofol, followed by boluses of 10-20 mg of propofol based on clinical response. The outcomes assessed were propofol dose, hypotension, and respiratory depression.

Sakaguchi (2011) performed an RCT comparing bispectral-index (BIS)-guided TCI with MCI of propofol in 40 patients undergoing dental treatment. A total of 20 patients was included in the intervention group (age 30.5 ± 11.2 years, 60% males), 20 patients were included in the control group (age 30.5 ± 10.8 years, 75% males). The BIS-TCI was set at a target concentration of 1.5 µg/mL. Patients in the control group received several starting boluses of 10 mg propofol until patient achieved the Assessment of Behavior Reactions (ABR) score 2. Thereafter, propofol was continuously infused at a rate of 4.0 mg/kg/r, using a TCI pump in manual infusion mode. The outcomes assessed were propofol consumption, hypotension, and respiratory depression.

Vučićević (2016) performed an RCT comparing TCI with manual intravenous titration technique of propofol in 90 patients undergoing colonoscopy. A total of 45 patients was included in the intervention group (age 50.4 ± 11.2 years, 33% males), 45 patients were included in the control group (age 49.0 ± 11.9 years, 42% males). The TCI was programmed with an initial target effect-site of 2.5 µg/mL, the concentration was increased or decreased by 0.5-1 µg/mL until the deep level of sedation was achieved. Patients in the control group received intravenous 10 mg/mL propofol in a bolus of 0.5 mg/kg, and then 10-20 mg was titrated every 1-2 minutes. The outcomes assessed were time to sedation and propofol consumption.

Wang (2016) performed an RCT comparing TCI with MCI of propofol in 72 patients undergoing colonoscopy. A total of 36 patients was included in the intervention group (age 42.6 ± 7.6 years, 58% males), 36 patients were included in the control group (age 40.2 ± 6.9 years, 64% males). The TCI was programmed with a primary plasma concentration of 3.0 µg/mL with adjustment of 0.2 µg/mL based on the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Score. Patients in the control group received injections of 1.5 mg/kg and then continuously infused at 6 mg/kg/h. A bolus of 0.5 mg/kg propofol was injected as required. The outcomes assessed were hypotension, respiratory depression, and patient satisfaction.

Results

Effectiveness - Time to sedation (crucial)

Chiang (2013) and Vučićević (2016) reported the mean ± SD time to sedation.

Chiang (2013) reported that the mean time to sedation was 2.93 ± 2.61 minutes in the intervention group versus 2.43 ± 1.78 minutes in the control group. The mean difference (MD) was 0.50 minutes (95%CI -0.09 to 1.09) in favour of the control group. Vučićević (2016) reported that the mean time to sedation was 3.28 ± 0.62 minutes in the intervention group versus 3.31 ± 0.55 minutes in the control group. The MD was -0.03 minutes (95%CI -0.27 to 0.21).

The pooled MD of time to sedation was 0.16 minutes (95%CI -0.34 to 0.66), which is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure time to sedation came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: unclear procedure of allocation concealment and blinding was not reported); small number of included patients (1 level for imprecision).

Effectiveness - Propofol dose (crucial)

Chang (2015), Chiang (2013), De Vito (2017), Franzen (2016), Sakaguchi (2011) and Vučićević (2016) reported on the propofol dose.

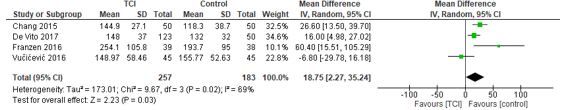

Four studies reported the average propofol dose in mg. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis (Figure 1).

The MD for propofol dose in mg of the pooled results was 18.75 mg (95% CI 2.27 to 35.24), meaning a higher overall propofol consumption in the intervention groups. This result is in favour of the control group and is not a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 1: Meta-analysis of four studies reporting on propofol dose (mg)

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

One study reported the average propofol dose in mL. Chiang (2013) reported a mean propofol dose of 32.02 ± 12.09 mL in the intervention group compared with a mean propofol dose of 34.22 ± 9.19 mL in the control group. The MD was -2.20 mL (95%CI -5.04 to 0.64), in favour of TCI. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

One study reported the average propofol dose in µg/kg/min. Sakaguchi (2011) reported a mean propofol dose of 144.9 ± 27.1 µg/kg/min in the intervention group compared with a mean propofol dose of 118.3 ± 38.7 µg/kg/min in the control group. The MD was 26.60 µg/kg/min (95%CI 13.50 to 39.70), in favour of the control group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure propofol dose came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: unclear procedures of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding, no information on comparison of groups), conflicting results (1 level for inconsistency); small number of included patients and crossing the threshold for clinical relevance (1 level for imprecision).

Hypotension (important)

Chang (2015), De Vito (2017), Franzen (2016), Sakaguchi (2011), and Wang (2016) reported on hypotension. Hypotension was not defined in all studies except in the study of Franzen (2016), where hypotension was defined as a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg.

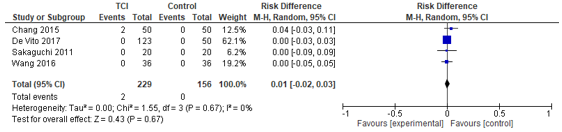

Four studies reported the number of events of hypotension. The results were pooled in a meta-analysis (Figure 2). In total, 2 of the 229 (%) patients in the intervention group experiences hypotension, compared to 0 of the 156 (0%) patients in the control group. The risk difference (RD) was 0.01 (95%CI -0.02 to 0.03), which is not a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2: Meta-analysis of four studies reporting on number of events of hypotension

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Franzen (2016) reported the mean number of events of hypotension per minute. In the intervention group, the mean number of events per minute was 0.02 ± 0.05 compared to 0.01 ± 0.03 in the control group. The MD was 0.01 (95%CI -0.01 to 0.03), which is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypotension came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: unclear procedures of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding, no information on comparison of groups); small number of participants and small number of events (2 levels for imprecision).

Respiratory depression (important)

Chang (2015), Chiang (2013), De Vito (2017), Franzen (2016), Sakaguchi (2011), and Wang (2016) reported on respiratory depression.

Different definitions were used in the studies. Chang (2015) defined respiratory depression as mean end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) >60 mmHg or assisted ventilation (oxygen saturation SpO2 <95%). Chiang (2013) defined respiratory depression as SpO2 <90% (mild) or SpO2 <85% (moderate). Franzen (2016) and Wang (2016) defined respiratory depression as SpO2 < 90%. De Vito (2017) and Sakaguchi (2011) did not report a definition of respiratory depression. Because of the different definitions used, the data were not pooled in a meta-analysis.

Chang (2015) reported a total of 19 events of respiratory depression, of which 7 events occurred in the intervention group (7/50, 14%) and 12 events occurred in the control group(12/50, 24%). The risk ratio (RR) was 0.58 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.36) in favour of TCI. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Chiang (2013) reported a total of 83 events of respiratory depression, of which 34 events occurred in the intervention group (34/110, 30.9%) and 49 events occurred in the control group(49/110, 44.5%) , resulting in a RR of 0.69 (95%CI 0.49 to 0.98) in favour of TCI. This is a clinically relevant difference.

De Vito (2017) reported a total of 8 events of respiratory depression, no events occurred in the intervention group (0%) and 8 events occurred in the control group (8/50, 16%), resulting in a RD of -0.16 (95% CI -0.26 to -0.06) in favour of TCI. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Sakaguchi (2011) and Wang (2016) did not report any events of respiratory depression in both the intervention and the control group.

Franzen (2016) reported the mean number of events of respiratory depression per minute. In the intervention group, the mean number of events per minute was 0.13 ± 0.10 compared to 0.17 ± 0.14 in the control group. The MD was -0.04 (95%CI -0.09 to 0.01), in favour of TCI. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure respiratory depression came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: unclear procedures of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding, no information on comparison of groups); inconsistent definitions and study results (1 level for inconsistency); small number of included patients (1 level for imprecision).

Patient satisfaction (important)

Chiang (2013) and Wang (2016) reported on patient satisfaction.

Chiang (2013) used a questionnaire containing three questions with a 7-point Likert scale. On the first question, ‘I feel comfortable and relaxed’, the intervention group scored a median of 7 (interquartile range (IQR) 7-7) compared to 7 (7-7) in the control group. On the second question, ‘I am free of nausea and vomiting’, the intervention group scored 7 (7-7) compared to 7 (7-7) in the control group. On the third question, ‘In the event that I need the exam again, I hope to have the same sedative quality’, the intervention group scores 7 (7-7) compared to 7 (7-7) in the control group.

No differences between scores on patient satisfaction in the intervention versus control group were found.

Wang (2016) used a 100-mm visual analogue scale to assess patient satisfaction. On this scale, the intervention group scored 77.2 ± 6.7 compared to 76.8 ± 7.8 in the control group (p=0.808). The MD was 0.40 (95%CI -2.96 to 3.76), which is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (1 level for risk of bias: no randomization, no information on allocation concealment); small number of included patients (1 level for imprecision). Publication bias could not be assessed.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the added value of target-controlled infusion (TCI) compared to intermitted boluses and continuous intravenous administration in propofol sedation on effectiveness, safety and patient satisfaction in adult patients undergoing Procedural Sedation and Analgesia (PSA)?

P: adult patients undergoing PSA

I: TCI with propofol

C: intermitted boluses or continuous intravenous administration of propofol

O: effectiveness (dosage, time to sedation), complications (hypotension; respiratory depression), patient satisfaction.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered effectiveness as a crucial outcome measure for decision making; and complications and patient satisfaction as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but handled the definitions used in the retrieved studies.

The working group defined a minimal clinically relevant difference as a difference in time to sedation of 1 minute and a difference in propofol dose of 50 mg, 5 mL (propofol 10%) or 16 µg/kg/min. For dichotomous outcomes (hypotension or respiratory depression), a difference of 25 % (RR ≤0.8 or ≥1.25) was used. For VAS scales of 100mm (patient satisfaction), a difference of 10mm and for ordinal scales (7-point Likert scale for patient satisfaction) a difference of 1 point was considered clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until February 15, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 220 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (SR) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing TCI propofol sedation with intermitted boluses of continuous intravenous administration of propofol sedation in patients undergoing PSA, published after 2005. A total of 70 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 59 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and five studies were included. In addition, one SR partly met de PICO. Studies from this SR meeting the PICO were also included (n=2). In total eight RCTs were included for the literature summary.

Results

Seven RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Chang YT, Tsai TC, Hsu H, Chen YM, Chi KP, Peng SY. Sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy with the application of target-controlled infusion. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015;26(5):417-22. Epub 2015/09/10. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2015.0206. PubMed PMID: 26350688.

- Chiang MH, Wu SC, You CH, Wu KL, Chiu YC, Ma CW, et al. Target-controlled infusion vs. manually controlled infusion of propofol with alfentanil for bidirectional endoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2013;45(11):907-14. Epub 2013/10/30. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344645. PubMed PMID: 24165817.

- De Vito A, Agnoletti V, Zani G, Corso RM, D'Agostino G, Firinu E, et al. The importance of drug-induced sedation endoscopy (D.I.S.E.) techniques in surgical decision making: conventional versus target controlled infusion techniques-a prospective randomized controlled study and a retrospective surgical outcomes analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(5):2307-17. Epub 2017/02/19. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4447-x. PubMed PMID: 28213776.

- Franzen D, Bratton DJ, Clarenbach CF, Freitag L, Kohler M. Target-controlled versus fractionated propofol sedation in flexible bronchoscopy: A randomized noninferiority trial. Respirology. 2016;21(8):1445-51. Epub 2016/06/16. doi: 10.1111/resp.12830. PubMed PMID: 27302000.

- Sakaguchi M, Higuchi H, Maeda S, Miyawaki T. Dental sedation for patients with intellectual disability: a prospective study of manual control versus Bispectral Index-guided target-controlled infusion of propofol. J Clin Anesth. 2011;23(8):636-42. Epub 2011/12/06. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.04.008. PubMed PMID: 22137516.

- Vučićević V, Milakovi? B, Tešić M, Djordjevi? J, Djuranovic S. Manual versus target-controlled infusion of balanced propofol during diagnostic colonoscopy - A prospective randomized controlled trial. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2016;144(9-10):514-20. Epub 2016/09/01. PubMed PMID: 29653037.

- Wang JF, Li B, Yang YG, Fan XH, Li JB, Deng XM. Target-Controlled Infusion of Propofol in Training Anesthesiology Residents in Colonoscopy Sedation: A Prospective Randomized Crossover Trial. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:206-10. Epub 2016/01/21. doi: 10.12659/msm.895295. PubMed PMID: 26787637; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4727496.

Evidence tabellen

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Chang, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Taiwan

Funding and conflicts of interest: No financial support; no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: adult patients undergoing upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy

Exclusion criteria: an allergic reaction history to any of the study drugs, eggs, or soybeans; chronic exposure to opioid analgesics or sedative medication; inpatient status; a history of obstructive sleep apnea; seizure disorders; and gross obesity [a body mass index (BMI) greater than 42 in males or 35 in females).

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 patients Control: 50 patients

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 50.0 ± 13.5 C: 51.4 ± 14.2

Sex: I: 46% M C: 50% M |

TCI for upper/lower gastrointestinal endoscopy In the TCI group, the patients were given a dose of 2–2.5 mg of midazolam. Subsequently, we administrated propofol and alfentanil through an intravenous cannula utilizing a TCI system. The TCI system included two-unit infusion pumps controlled by a microprocessor system. The pharmacokinetic data distribution and elimination of propofol and alfentanil were programmed in the TCI system. We used the pharmacokinetic model proposed by Schnider et al. for propofol and the model proposed by Scott et al. for alfentanil. The patients received an initial target effect-site concentration of 4 μg/mL for propofol until loss of consciousness (loss of verbal contact) was achieved. This was immediately followed by a target effect-site concentration of 2.5 μg/mL. During the endoscopy procedures, the maintenance concentration was adjusted to 0.5 μg/mL higher or lower when needed.

|

Manual administration of propofol for upper/lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. In the control group, patients were administered a dose of 0.27 mg of alfentanil and a dose of 2–2.5 mg midazolam based on their age and body weight. After 3 min, propofol was administered and titrated to the desired sedation effect with a dose of 20–30 mg. If necessary, the nurse anesthetist empirically administered additional doses of alfentanil and propofol based on the patient’s response during the procedure.

|

All outcomes are measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Effectivity Time to sedation Not reported Propofol consumption I: 144.9 ± 27.1 mg C: 118.3 ± 38.7 mg (p<0.05) Absolute mean difference: 26.60 mg [95%CI 13.50; 39.70]

Adverse events Hypotension: Two patients in the TCI group were treated with low doses of ephedrine because of severe hypotension Respiratory depression (Mean EtCO2 >60 mmHg or assisted ventilation (SpO2 <95%)): I: 7 (14%) C: 12 (24%) (Overall p=0.44)

Patient satisfaction Not reported

|

Author conclusions: In summary, our study showed that sedation using TCI for GI endoscopy provided effective and safe sedation and was associated with better sedation quality. The depth of sedation appeared to be appropriate and allowed the patients to be easily maneuvered during the procedures. We believe that TCI can be used to provide routine sedation for patients undergoing GI endoscopy. |

|

Chiang, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Taiwan

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding reported, no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Patients undergoing bidirectional endoscopy and ASA physical status 1 or 2.

Exclusion criteria: a history of known allergy to propofol or its lipid emulsion, or drug or alcohol abuse

N total at baseline: Intervention: 110 Control: 110

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 50.51 ± 11.44 years C: 51.14 ± 10.19 years

Sex: I: 55% M C: 54% M

|

TCI for bidirectional endoscopy The propofol TCI group was set with the Model of TCI Effect (Schneider pharmacokinetic model, maximal flow rate <700mL/h) at an initial concentration (Ce) of 4.0 μg/mL. |

MCI for bidirectional endoscopy The MCI group were inducted by a bolus propofol dose of 1.5mg/kg with the same rate limitation (<700mL/h) followed by a maintenance dose at 6–12mg/kg/h as previously reported |

All outcomes are measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Effectivity Time to sedation I: 2.93 ± 2.61 min C: 2.43 ± 1.78 min (p=0.091) Propofol consumption I: 32.02 ± 12.09 mL C: 34.22 ± 9.19 mL (p=0.119) Absolute mean difference: -2.20 mL [95%CI -5.04; 0.64]

Adverse events Mild oxygen desaturation (SpO2 <90%) I: 34 (30.9%) C: 49 (44.5%) RR 0.694 (95%CI 0.490-0.983) (p=0.037) Moderate oxygen desaturation (SpO2 <85%) I: 17 (15.5%) C: 34 (30.9%) RR 0.50 (95%CI 0.298-0.840) (p=0.007) Hypotension Not reported

Patient satisfaction (comfortable) I: 7 (7-7) C: 7 (7-7) (p=0.276) Patient satisfaction (free of nausea) I: 7 (7-7) C: 7 (7-7) (p=0.407) Patient satisfaction (same sedative quality next time) I: 7 (7-7) C: 7 (7-7) (p=0.090)

|

Author conclusions: the current study demonstrated that TCI using propofol with alfentanil presented faster recovery, better hemodynamic and respiratory stability, and fewer adverse events than MCI in same-day bidirectional endoscopy with targeted deep sedation. In addition, patients in the MCI group had more concerns and required more assistance to maintain upper airway patency during this bidirectional endoscopic procedure. |

|

De Vito, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Italy

Funding and conflicts of interest: No reporting on funding; no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients, Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) of 15-30, men and women, age 18-65 years, BMI <30, awake oxygen saturation >85% and able to read and sign consent form.

Exclusion criteria: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), liver disease (Child Pugh 1–3), history of chronic use of sedatives, narcotics, alcohol or illicit drugs, history of 1st and 2nd degree heart block (not paced), left ventricular Ejection Fraction (EF) <50, allergy to propofol or to any medications, OSHAS surgical failure patients and pregnant women.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 123 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 51 ± 11 years C: 48 ± 12 years

Sex: I: 91% M C: 86% M

|

Sleep endoscopy was performed by a TCI system using Schnider model in effect-site (cerebral) targeted infusion 50-ml prefilled syringe of 1% propofol. The starting dose of propofol was 1.5 mcg ml−1 and increments of 0.2 mcg ml−1 took place when the new cerebral concentration of propofol was reached. In this way, we realized a slow technique of TCI propofol infusion.

|

A sleep endoscopy was manually performed using 1 mg kg−1 of propofol as induction bolus and 20 mg of boluses was repeated every 2 min, with a 20-ml syringe.

|

All outcomes are measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Effectivity Time to sedation Not reported Propofol consumption I: 148 ± 37 mg C: 132 ± 32 mg (p<0.05) Absolute mean difference: 16.00 mg [95%CI 4.98; 27.02]

Adverse events Severe oxygen desaturation I: 0 (0%) C: 8 (16%) (p<0.05) Hypotension I: 0 (0%) C: 0 (0%)

Patient satisfaction Not reported |

Author conclusions: Even in experienced hands, conventional DISE can potentially be ineffective and dangerous. Our results suggest that the DISE-TCI technique should be the first choice in performing sleep-endoscopy because of its increased accuracy, stability and safety, even though a clear polysomnografic analysis is imperative to allow us to differentiate OSA patients in whom UA anatomical abnormalities are predominant in comparison with not-anatomical pathophysiologic factors.

Randomization was not 1:1, intervention was performed up to jan 2015, while control was performed up to jan 2011. Unclear how this study was performed exactly. |

|

Franzen, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT (noninferiority)

Setting and country: Switzerland

Funding and conflicts of interest: No reporting of funding or conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: patients undergoing flexible bronchoscopy

Exclusion criteria: Any contraindication to use propofol for sedation; Body mass index > 35 kg/m2; Immunosuppressive therapy after organ transplantation; Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection; Known or suspected drug or alcohol abuse; Inability to follow the procedures of the study ; Participation in another study with either an investigational drug within 30 days preceding and during the present study; Previous enrolment into the current study; Enrolment of the investigator, his/her family members, employees and other dependent persons; bronchoscopy in attendance of an anaesthesiologist; Age below 18 or above 85 years.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 39 patients Control: 38 patients

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 65.6 ± 11.3 yrs C: 64.0 ± 11.6 yrs

Sex: I: 63% M C: 59% M

|

TCI for flexible bronchoscopy

TCI of propofol. Bronchoscopy was started after reaching the initial targeted effect site concentration (Ce) of 2.5 μg/mL propofol using the Schnider pharmacokinetic model described elsewhere, which is based on certain biometric values as total weight, lean body mass and height.6,13–16 Thereafter, Ce could be adjusted depending on the clinical effect by increments of 0.2 μg/mL, in order to maintain the required level of sedation

|

Fractionated propofol administration for flexible bronchoscopy

Fractionated propofol administration using non-anaesthesiologist administration of propofol. The loading doses of propofol were titrated in order to achieve the adequate sedation level (onset of ptosis). Patients received an initial bolus of 30–40mg of propofol, followed by a carefully titrated dose of 10–20mg of propofol based on the clinical response. Between each bolus, a pause lasting more than 20 s had to be observed. |

All outcomes are measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Effectivity Time to sedation Not reported Propofol dose I: 254.1 ± 105.8 mg C: 193.7 ± 95.0 mg (p=0.003) Absolute mean difference: 60.40 mg [95%CI 15.51; 105.29]

Adverse events Oxygen desaturation (SpO2 <90%) (mean number events/min) I: 0.13 ± 0.10 C: 0.17 ± 0.14 (p=0.35) Hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg) (mean number events/min I: 0.02 ± 0.05 C: 0.01 ± 0.03 (p=0.27)

Patient satisfaction Not reported

|

Author conclusions: In conclusion, we suggest that TCI of propofol is a favourable sedation technique for FB. Safety issues (oxygenation, ventilation and blood pressure), cough frequency and procedure times are comparable with FPA. Using TCI, fewer interventions are needed to induce and maintain sedation. However, the cumulative dose of propofol is higher with the use of TCI, which is maybe negligible, particularly when Ce is adapted to different stages of FB.

A per-protocol analysis was performed were about 20% of patients were excluded. Patients who received a maximum of more than 10 L/min of oxygen or an intervention via a nasopharyngeal airway insertion during the procedure were excluded from this analysis. |

|

Sakaguchi, 2011 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded by non-commercial grant, no statement on conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: age 16 years or older; ASA physical status 1 or 2; treatment for dental caries, endodontics, periodontics, and prosthesis; moderate or severe intellectual disability

Exclusion criteria: a cooperating patient who could communicate; premedication; uncontrolled or severe medical condition

N total at baseline: Intervention: 20 patients Control: 20 patients

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 30.5 ± 11.2 C: 30.5 ± 10.8

Sex: I: 60% M C: 75% M

|

Bispectral index (BIS)-guided TCI for dental treatment

Propofol was infused with a TCI pump at a target concentration of 1.5 µg/ml.

|

Manually controlled infusion of propofol without BIS monitoring for dental treatment

Several bolus injections of 10 mg propofol were given at 20-second intervals until patients achieved assessment of Behavior Reactions (ABR) score 2. Thereafter propofol was continuously infused at a rate of 4.0 mg/kg/r, using a TCI pump in manual infusion mode.

|

All outcomes are measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Effectivity Time to sedation Not reported Average propofol consumption (mean ± SD): I: 76.1 ± 18.8 µg/kg/min C: 93.3 ± 18.8 µg/kg/min (p=0.0061) Absolute mean difference: -17.20 µg/kg/min [95%CI -28.85; -5.55]

Adverse events Hypotension I: 0 (0%) C: 0 (0%) Oxygen deprivation I: 0 (0%) C: 0 (0%)

Patient satisfaction Not reported |

Author conclusions: In conclusion, BIS-guided TCI over conventional manual control 1) reduced the dose requirement of propofol and 2) promoted quicker recovery from sedation.

Authors state that there were no significant complications. |

|

Vučićević, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Serbia

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding or conflict of interest reported |

Inclusion criteria: patients of both sexes, 18-65 years old, classified into group 1 or 2 of ASA scheduled for diagnostic outpatient colonoscopy with deep sedation.

Exclusion criteria: those allergic to the study drugs, patients with previous problems with anesthesia or sedation, patients with history of stridor, snoring or sleep apnea, patients with neck abnormalities, and those classified into groups III or IV of Mallampati classification [12], patient with neuropsychiatric, cardiac, respiratory, renal disorders, those in pregnant state, and with history of large-bowel surgery.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 45 Control: 45

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 50.35 ± 11.21 years C: 49.02 ± 11.91 years

Sex: I: 33% M C: 42% M

|

TCI propofol for colonoscopy

Patients received propofol with TCI pump according to the Schnider’s pharmacokinetic model, with the initial Ce of 2.5 μg/ml. This concentration was increased or decreased by 0.5–1 μg/ml until the deep level of sedation was achieved. |

Manual intravenous titration technique of propofol for colonoscopy

Patients received propofol intravenously (10 mg/ml), in a bolus of 0.5 mg/kg, and then 10–20 mg were titrated every one to two minutes. |

All outcomes are measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Effectivity Time to sedation (induction time) I: 3.28 ± 0.62 min C: 3.31 ± 0.55 min (p=0.859) Propofol consumption I: 148.97 ± 58.46 mg C: 155.77 ± 52.63 mg (p=0.563) Absolute mean difference: -6.80 mg [95%CI -29.78; 16.18]

Adverse events Severe oxygen desaturation Not reported Hypotension Not reported

Patient satisfaction Not reported |

Oxygen and blood pressure levels were reported, however not above/under certain thresholds. This was stated in the methods, but was not reported in the results. |

|

Wang, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: China

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial funding from Changhai Hospital; no conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: patients meeting indication of elective colonoscopy, age >18 years old, ASA status 1 or 2

Exclusion criteria: morbid obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2); predicted difficult airway; hypertension; known cardiac diseases; acute or chronic hepatic and renal dysfunction; long-term use of anesthetics or opioids; and patients undergoing invasive procedures under colonoscopy.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 36 patients Control: 36 patients

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 42.6 ± 7.6 yrs C: 40.2 ± 6.9 yrs

Sex: I: 58% M C: 64% M

|

TCI propofol for colonoscopy

In the TCI group, propofol was infused through the Module DPS TCI system using the Marsh model. The primary plasma concentration was set as 3.0 μg/ml and an adjustment of 0.2 μg/ml was made upon the patients’ response based on the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (OAAS) Score.

|

Manually-controlled infusion (MCI) propofol for colonoscopy.

In the MCI group, propofol was injected at a bolus of 1.5 mg/kg and then continuously infused at 6 mg/kg/h using the conventional continuous microinfusion pump. A bolus of 0.5 mg/kg propofol was be injected as required.

|

All outcomes are measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Effectivity Time to sedation Not reported Propofol dose Not reported

Adverse events Oxygen desaturation (SpO2 <90%) I: 0 (0%) C: 0 (0%) Hypotension (mean blood pressure <55 mmHg) I: 0 (0%) C: 0 (0%)

Patient satisfaction I: 77.2 ± 6.7 C: 76.8 ± 7.8 (p=0.808)

|

Author conclusions: Given the fact that training residents of anesthesiology were less experienced in colonoscopy sedation, propofol TCI is an ideal infusion mode for them to improve sedation quality and promote stable cardiovascular and respiratory status.

Cross over was performed on the 18 training residents in anaesthesiology, they first received TCI or MCI training for one month, and then vice versa for the second month. The last two patients of each month of each training resident were used in this study. |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Risk of Bias tables

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research question: What is the added value of target-controlled infusion (TCI) compared to intermitted boluses and continuous intravenous administration in propofol sedation (and pain relief) on effectiveness, safety and patient satisfaction in adult patients undergoing Procedural Sedation and Analgesia (PSA)?

|

Study reference

|

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely ye Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Chang, 2015 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Computer-generated randomization blocks. |

No information

Reason: - |

Definitely no

Reason: Health care providers not blinded, blinding of patients, outcome assessors blinded, data collectors and analysts not reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes were measured during or on the same day as the procedure |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (propofol consumption, adverse events)

Reason: potential problems with concealment of randomization and blinding. |

|

Chiang, 2013 |

Definitely yes

Reason: computer-generated number table for a single-factor complete randomization |

Definitely yes

Reason: randomization performed by independent data manager not involved in study analysis. Opaque envelops were used and opened just before each procedure. |

Probably yes

Reason: patients, health care providers and outcome assessors were blinded. Anaesthesiologists were not blinded, but their infusion protocols were controlled. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes were measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW (propofol consumption, adverse events, patient satisfaction) |

|

De Vito, 2017 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Computer-generated schedule for random allocation |

Probably yes

Reason: Sealed in numbered envelopes |

Probably no

Reason: Blinding was not reported, but a blinded revision was conducted on reported outcomes |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes were measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably no

Reason: there was no information on the comparability of the study groups at baseline. |

HIGH (propofol consumption, adverse events)

Reason: potential problems with blinding, no information on comparability of study groups. |

|

Franzen, 2016 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Randomized using sequentially numbered sealed opaque enveloped |

No information

Reason: - |

Probably no

Reason: Patients blinded, health care providers and outcome assessors not blinded (blinding of data collectors and data analysis not reported.) |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes were measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW (propofol consumption, adverse events) |

|

Sakaguchi, 2011 |

Definitely no

Reason: Allocation based on clinical record number |

Probably no

Reason: Allocation performed by non-investigator at hospital registration |

Probably no

Reason: Health care providers and outcome assessors blinded, anestesiologist not blinded, patients were probably not blinded (blinding of data collectors and analysts not reported) |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes were measured during or on the same day as the procedure |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (propofol consumption, adverse events)

Reason: potential problems with randomization and blinding. |

|

Vučićević, 2016 |

Probably yes

Reason: randomization based on random-numbers table |

No information

Reason: - |

Probably no

Reason: Blinding was not reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All outcomes were measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Definitely no

Reason: Adverse events were not reported in result section. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns (time to sedation, propofol consumption)

Reason: no information on allocation concealement, blinding was not reported

|

|

HIGH (adverse events)

Reason: Adverse events were not reported in result section, while they were mentioned as outcomes. |

|||||||

|

Wang, 2016 |

Probably no

Reason: No information on randomization of patients, only randomization of anaesthesiology residents (randomly allocated based on computer-generated numbers) |

No information

Reason: - |

Probably no

Reason: Endoscopists and patients were blinded, anesthesiologists, outcome assessors were not blinded. (blinding of data collectors and analysts not reported) |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All outcomes were measured during or on the same day as the procedure

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

HIGH (adverse events, patient satisfaction)

Reason: patients were not randomized, there was no information on allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors was not performed. |

- Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules..

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body. Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

- Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Lu 2015 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Kreienbühl 2018 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Burton 2020 |

Relevant studies included individually |

|

Singh 2008 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Hewson 2021 |

Study design |

|

Leslie 2008 |

Withdrawn publication |

|

Crepeau 2005 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Takuma 2005 |

Foreign language |

|

Alhashemi 2006 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Stonell 2006 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Park 2007 |

Study design |

|

Poon 2007 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Telletxea 2008 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Yun 2008 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Liu 2009 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Bell 2010 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Mandel 2010 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Clouzeau 2011 |

No control group |

|

Mazanikov 2011 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Lin 2013 |

Study design |

|

Maurice-Szamburski 2013 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Chan 2014 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Song 2014 |

Foreign language |

|

Fanti 2015 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Hsu 2015 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Nilsson 2015 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Gemma 2016 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Heiser 2017 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Jokelainen 2017 |

Study design |

|

Jokelainen 2018 |

Study design |

|

Burton 2019 |

Study design |

|

Burton 2020 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Grossmann 2019 |

Study design |

|

Grossman 2020 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Hong 2005 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Azdemir 2005 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Singh 2005 |

Conference abstract |

|

Barakat 2007 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Jee 2008 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Mahon 2008 |

Study design |

|

Nilsson 2008 |

Study design |

|

Oka 2008 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Keyl 2009 |

Study design |

|

Kwon 2009 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Oka 2009 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Joo 2012 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Mazanikov 2012 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Nilsson 2012 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Hsu 2013 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Nagels 2014 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Cascella 2017 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

De Vito 2017 |

Study design |

|

Sprinks 2019 |

Study design |

|

Lin 2020 |

Does not fit PICO (C) |

|

Wahlen 2008 |

Does not fit PICO (I) |

|

Laosuwan 2011 |

No full text available |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 23-05-2024

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij sedatie en/of analgesie bij volwassen patiënten.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. B. Preckel (voorzitter), anesthesioloog, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVA

- dr. C.R.M. Barends, anesthesioloog, UMCG, NVA

- L.R.M. Braam, BSc. Sedatie Praktijk Specialist, Catharina Ziekenhuis, NVAM

- drs. R. Brethouwer, abortusarts, Beahuis & Bloemenhovekliniek Heemstede, NGvA

- dr. J.M. van Dantzig, cardioloog, Catharina Ziekenhuis, NVVC

- drs. V.A.A. Heldens, anesthesioloog, Maxima MC, NVA

-

dr. C. Heringhaus, SEH-arts/anesthesioloog, LUMC (t/m 12-2022), Medisch manager Hyperbare Zuurstoftherapie Goes, MCHZ (vanaf 01-2023), NVSHA

- T. Jonkergouw, MA. Adviseur Patiëntbelang, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland (tot april 2023)

- Broere, M. Junior beleidsadviseur, Patiëntenfederatie Nederland (vanaf april 2023)

- dr. M. Klemt-Kropp, MDL-arts, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep, NVMDL

- drs. B.M.F. van der Leeuw, anesthesioloog, Albert Schweitzer ziekenhuis, NVA

- S. Reumkens, MSc. Physician Assistant, Diakonessenhuis, NAPA

Klankbordgroep

- drs. T.E.A. Geeraedts, radioloog, Erasmus MC, NVvR

- drs. J. Friederich, gynaecoloog, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep, NVOG

- dr. E.H.F.M. van der Heijden, longarts, Radboud UMC, NVALT

- drs. J. de Hoog, oogarts, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NOG

- drs. A. Kanninga, arts voor verstandelijk gehandicapten, Cordaan, NVAVG

- drs. H.W.N. van der Pas, tandarts, UMC Utrecht, VMBZ

- dr. ir. C. van Pul, klinisch fysicus, Maxima MC, NVKF

- dr. R.J. Robijn, MDL-arts, Rijnstate, NVMDL

- drs. W.S. Segers, klinisch Geriater, Catharina Ziekenhuis, NVKG

- Prof. dr. A. Visser, hoogleraar geriatrische tandheelkunde, UMCG en Radboud UMC, KNMT

Met ondersteuning van:

- dr. L. Wesselman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- dr. S.N. Hofstede, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

- drs. I. van Dusseldorp, senior literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Preckel |

Anesthesioloog, hoogleraar anesthesiologie (in het bijzonder veiligheid in het perioperatieve proces) Amsterdam Universitair Medische Centra locatie AMC |

Onbetaalde nevenwerkzaamheden – commissie-werkzaamheden:

Lid Patient Safety and Quality Committee of the European Society of Anesthesiologists;

Lid Patient Safety Committee van de World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists;

Lid Raad Wetenschap en Innovatie van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten FMS;

Lid Commissie Wetenschap & Innovatie van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie NVA

Representative Council European Association of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology and Intensive Care (EACTAIC)

Hoger leidinggevend personeel (penningmeester) van de “Stichting ter bevordering van de wetenschap en opleiding in de anesthesiologie”;

|

Research grants: European Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care ESAIC ZonMw NovoNordisk Netherland

Advisory board Sensium Healthcare United Kingdom

Geen van de gemelde belangen heeft relatie met het onderwerp van het advies/de richtlijn

|

Geen actie vereist |

|

Barends |

Anesthesioloog in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Braam |

Sedatiepraktijkspecialist Catharina Ziekenhuis Eindhoven |

Lid sedatie commissie NVAM (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Brethouwer |

Abortusarts te Beahuis & Bloemenhovekliniek (0,56 fte) en SAA (0,22 fte), Medisch coördinator Beahuis&Bloemenhovekliniek (0,33 fte) |

Penningmeester van het Nederlands Genootschap van Abortusartsen (onbetaald) Voorzitter landelijke werkgroep PSA van het NGvA (onbetaald) Bestuurslid van FIAPAC, een Europese abortus organisatie (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Broere |

Junior beleidsadviseur Patiëntenbelang - fulltime |

geen |

geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

van Dantzig |

Cardioloog vrij gevestigd, Catharina Ziekenhuis 100% |

Lid Plenaire Visitatie Commissie NVVC (onbetaald) |

Op onze afdeling wordt extern gefinancierd onderzoek uitgevoerd maar niet op het gebied van de werkgroep. |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Heldens |

Anesthesioloog Maxima MC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Heringhaus |

Vanaf 01-2023 Medisch manager Hyperbare Zuurstoftherapie Goes, MCHZ

t/m 12-2022 SEH-arts KNMG |

Trainingen voor verschillende onderwerpen gerelateerd aan acute zorg, hyperbare geneeskunde, PSA |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Jonkergouw |

Junior beleidsadviseur - Patiëntenfederatie Nederland - 32 tot 36 uur per week |

Vrijwilliger activiteiten - Diabetes Vereniging Nederland - Zeer incidenteel |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Klemt-Kropp |

MDL-arts, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep Alkmaar - Schagen - Den Helder (0.9 fte) |

Secretaris Concilium Gastroenterologicum, NVMDL tot 11 april 2022 (niet betaald) Voorzitter PSA commissie NVMDL (niet betaald) Docent Teach the Teacher AUMC en Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep cursussen voor aios en medisch specialisten (betaalde functie, ongeveer 40 Std. per jaar)

Voorzitter Stichting MDL Holland-Noord (KvK 56261225) vanaf okt. 2012 t/m 31-12-2019. De stichting heeft in de laatste 3 jaar grants ontvangen van de farmaceutische industrie en van de farmaceutische industrie gesponsorde onderzoeken gefaciliteerd:

1. Ondersteuning optimalisering van zorg voor IBD-patiënten. Therapeutic drugmonitoring en PROMs bij patiënten met IBD. Zorgverbetertraject. PhD student, looptijd van 2015 tot op heden. Tot 2018 grant van Dr. Falk Pharma. vanaf 2018 grant van Janssen Cilag Geen relatie met sedatie 2.Retrieval of patients chronically infected with Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C in Northern Holland. Afgesloten 2018. Project gefinancierd met grant van Gilead. Geen relatie met sedatie 3. SIPI. Screening op Infectieuze aandoeningen in Penitentiaire Inrichtingen. Project gefinancierd met grants van AbbVie, MSD en Gilead. Project begin 2019 afgesloten. Geen relatie met sedatie 4. 3DUTCH trial. Een observationeel onderzoek naar de effectiviteit van een behandeling van chronische hepatitis C met een combinatie van de antivirale middelen ombitasvir - paritaprevir /ritonavir, ± dasabuvir, ± ribavirine. Sponsor AbbVie. Studie afgesloten Jan. 2018 Geen relatie met sedatie 5. Remsima switch IFX9501 - An open-label, multicenter, non- inferiority monitoring program to investigate the quality of life, efficacy and safety in subjects with Crohn’s Disease (CD), Ulcerative Colitis (UC) in stable remission after switching from Remicade® (infliximab) to Remsima® (infliximab biosimilar) L016-048. Sponsor: Munipharma. Afgelsoten augustus 2018. Geen relatie met sedatie 6. NASH - NN9931-4296 Investigation of efficacy and safety of three dose levels of subcutaneous semaglutide once daily versus placebo in subjects with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis L016-061. Sponsor NovoNordisk. Studie afgesloten Feb. 2020. Geen relatie met sedatie 7. Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Parallel-group Efficacy and Safety Study of SHP647 as Induction Therapy in Subjects with Moderate to Severe Crohn's Disease (CARMEN CD 305). SHD-647-305. Sponsor Shire. Studie loopt sinds 2019. Geen relatie met sedatie 8. Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Parallel-group Efficacy and Safety Study of SHP647 as Maintenance Therapy in Subjects with Moderate to Severe Crohn's Disease (CARMEN CD 307). SHD-647-307. Sponsor Shire. Studie loopt sinds 2019. Geen relatie met sedatie 9. Estimating the prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis in a population cohort in care in Northern-Holland with the use of the non-invasive FIB-4 index. Grant van Gilead. Onderzoek afgesloten sept. 2019. Geen relatie met sedatie |

Incidenteel deelname aan advisory boards van de farmaceutische industrie (Gilead, Janssen Cilag, AbbVie: (hepatologische onderwerpen, vooral hepatitis C) Incidenteel voordrachten tijdens symposia gesponsord van de farmaceutische industrie (Gilead, AbbVie)

|

Geen actie vereist; meeste studies afgerond; nr. 1,7,8 lopen. Sponsoren (Dr. Falk Pharma & Shire) hebben geen relatie met sedatie. |

|

Reumkens |

Physician Assistant Anesthesiologie Radboud UMC |

Voorzitter vakgroep PA Anesthesiologie NAPA |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Van der Leeuw |

Anesthesioloog |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Robijn |

Mdl arts rijnstate ziekenhuis Arnhem |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Van der Heijden |

Longarts |

Voormalig Secretaris Sectie Interventie longziekten NVALT (onbezoldigd)

Lid Board of National Delegates European Association of Bronchology and International Pulmonology (namens NL, onbezoldigd)

|

Buiten het veld van deze richtlijn heeft mijn afdeling de afgelopen 3 jaar vergoedingen ontvangen voor de volgende activiteiten: - unrestricted research grants: Pentax Medical Europe, Philips, Astra Zeneca, Johnson&Johnson. - adviseur / consultant: Pentax Medical, Philips IGT, Johnson&Johnson. - spreker: Pentax Medical. |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Van der Pas |

Tandarts, UMC Utrecht |

Commissielid Horace Wells van de KNMT, stimulatie van de intercollegiale samenwerking bij tandheelkundige behandeling van bijzondere zorggroepen met farmacologische ondersteuning. Onbetaald. Voormalig commissielid Bijzondere Zorggroepen van de KNMT, toegankelijkheid van mondzorg voor kwetsbare zorggroep. Betaald via vacatiegelden. Gastdocent opleiding mondzorgkunde HU. Lezing mondzorg aan mensen met een verstandelijke beperking. Betaald. Gastdocent opleiding verpleegkundig-specialist GGZ. Lezing mondzorg in de geestelijke gezondheidszorg Betaald. Cursusleider lichte sedatie in de mondzorg, BT Academy. Meerdaagse cursus voor tandartsen en mondhygienisten om zich te bekwamen in lichte sedatie, m.n. training in de inhalatiesedatie met lachgas-zuurstof mengsel middels titratietechniek. Betaald. |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

De Hoog |

Oogarts in Amsterdam UMC (0,2 fte.) en Retina Operatie Centrum Amstelveen (0,4 fte.). Medisch manager Retina Operatie Centrum (0,2 fte.) |

Voorzitter Werkgroep Vitreoretinale Chirurgie Nederland (onbetaald) Lid redactieraad vaktijdschrift 'De Oogarts', uitgave van BPM-medica (onbezoldigd) Medeorganisator Eilanddagen (bijscholing uveïtis voor oogartsen, onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Geeraedts |

Interventieradioloog Afdeling Radiologie en Nucleaire geneeskunde Erasmus Medisch Centrum, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Van Pul |

Klinisch fysicus in Maxima Medisch Centrum |

Universitair Hoofd Docent aan de Technische Universiteit van Eindhoven (0,2 fte). Daar supervisor van PhD studenten bij HTSM (NWO-TTW gesubsidieerd) project waaraan ook een industriële partner deelneemt (https://www.nwo.nl/projecten/15345-0).

|

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Friederich |

Gynaecoloog NWZ Den Helder, Algemeen gynaecoloog met als aandachtsgebieden benigne gynaecologie, minimaal invasieve chirurgie en bekkenbodemproblematiek |

Vicevoorzitter calamiteitencommissie NVZ lid klachtencommissie NWZ Den Helder |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Segers |

Klinisch geriater, St. Jans Gasthuis, Weert

|

Klinisch farmacoloog in opleiding, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven Onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Kanninga |

Arts Verstandelijk Gehandicapten (arts VG) bij Cordaan Amsterdam Anesthesioloog niet praktiserend |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

|

Visser |

Hoogleraar geriatrische tandheelkunde fulltime (1 fte) - Afdeling Gerodontologie, Centrum voor Tandheelkunde en Mondzorgkunde, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Nederland - Afdeling Gerodontologie, Faculteit Tandheelkunde, Radboud UMC, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, Nederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie vereist |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference. Het verslag hiervan (zie aanverwante producten) is besproken in de werkgroep. Aanvullend heeft een afgevaardigde van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland deelgenomen in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de richtlijn. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming gedaan of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie ook het hiervoor gebruikte stroomschema dat als uitgangspunt voor de beoordeling is gebruikt).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn. Een overzicht van uitkomsten van de kwalitatieve raming met bijbehorende toelichting vindt u in onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Submodule Propofol |

geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die procedurele sedatie en/of analgesie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Anesthesiologie, de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde, de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie, de Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen, de Vereniging voor Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied, de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Intensive Care, de Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging, de Nederlandse Vereniging van Spoedeisende Hulp Artsen, het Nederlands Genootschap van Abortusartsen, de Nederlandse Vereniging van Anesthesiemedewerkers, de Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland, de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Mondziekten, Kaak- en Aangezichtschirurgie, de Vereniging Mondzorg voor Bijzondere Zorggroepen, Stichting Kind & Ziekenhuis, Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd en de Vereniging van Artsen voor Verstandelijk Gehandicapten via een invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.