Esketamine

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van esketamine in combinatie met propofol bij sedatie van volwassen patiënten buiten de OK?

Aanbeveling

Weeg voor de keuze van medicijnen voor PSA per patiënt het risico op apneu en hypotensie af tegen het risico op post procedurele misselijkheid en braken.

Maak op basis van deze afweging de keuze voor een opioïde of esketamine als adjuvant bij propofol sedatie.

Gebruik bij voorkeur esketamine in plaats van een opioïde als adjuvant bij propofol sedatie wanneer het verkleinen van het risico op apneu of hypotensie opweegt tegen het verhoogde risico op post procedurele misselijkheid en braken.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van procedurele sedatie en analgesie (PSA) met propofol in combinatie met esketamine in vergelijking met sedatie met propofol in combinatie met een opioïde op de veiligheid, patiënt tevredenheid, efficiëntie en kwaliteit van PSA bij patiënten die PSA ondergaan.

Veiligheid van PSA was gedefinieerd als cruciale uitkomstmaat. Op basis van de literatuur kan geconcludeerd worden dat complicaties als respiratoire afwijkingen en complicaties, hypotensie en bradycardie minder vaak lijken voor te komen wanneer patiënten sedatie ondergaan met propofol in combinatie met esketamine vergeleken met propofol in combinatie met een opioïde. Er zijn echter ook aanwijzingen dat dit niet leidt tot een verhoging van de incidentie van desaturatie als fysiologisch gevolg. Voor de complicatie “desaturatie” lijkt geen verschil te zijn tussen het gebruik van propofol en esketamine of propofol met een opioïde. Hetzelfde geldt voor het optreden van hypertensie en tachycardie: er lijkt geen verschil te zijn tussen het gebruik van propofol en esketamine of propofol met een opioïde. Misselijkheid en overgeven lijkt juist vaker voor te komen bij patiënten na sedatie met propofol en esketamine. De overall bewijskracht was laag. Er dient echter opgemerkt te worden dat de ASA-klasse in het merendeel van de trials ASA I-II was, en dat ouderen in het merendeel van de trials niet geïncludeerd werden.

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten kwaliteit en effectiviteit van PSA, als ook patiënt tevredenheid is bewijskracht voor deze uitkomsten zeer laag, waardoor deze geen richting kunnen geven aan de besluitvorming. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat operator tevredenheid lijkt er geen verschil te zijn tussen het gebruik van propofol en esketamine of propofol met een opioïde.

Hoewel (es-)ketamine bekend staat om beperkte of afwezige nadelige effecten op de ademhaling, zijn er in de literatuur onvoldoende aanwijzingen om te concluderen dat dit schijnbare voordeel van belang blijft wanneer esketamine wordt gecombineerd met propofol voor het gebruik tijdens PSA voor volwassenen. Dit blijkt ook uit een lagere frequentie van respiratoire problemen tijdens PSA zoals apneu en verslechtering van de ademhaling, waarbij de relevante fysiologische resultante daarvan, namelijk “desaturatie” niet beïnvloed wordt en dus de data te beperkt zijn om te kunnen spreken van een klinisch relevant verschil.

Hierbij kan ter overweging worden meegenomen dat propofol en esketamine zich op vele manieren laten combineren, waarbij esketamine als primair sedativum gebruikt kan worden met propofol als aanvulling ter bestrijding van psychotrope effecten, maar dat ook esketamine ingezet kan worden als analgeticum naast propofol, waarbij het laatste middel dan als primair sedativum dient. Er bestaan onvoldoende vergelijkende studies om aanbevelingen te doen over de te gebruiken verhoudingen esketamine:propofol en in de beschikbare literatuur worden verscheidene combinaties gebruikt.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten is het belangrijkste doel van PSA het op een veilige manier vermijden van discomfort tijdens en na de procedure. Amnesie, post-procedurele pijn en/of misselijkheid zijn vaak genoemde factoren die voor de patiënt hiervoor bepalend zijn.

Het gebruik van esketamine lijkt niet te leiden tot grotere operatortevredenheid. Op basis van de huidige literatuur is het onduidelijk of het gebruik van esketamine resulteert in een grotere patiënttevredenheid. Patiënten die behandeld zijn met esketamine hebben mogelijk wel een grotere kans op het optreden van post procedurele misselijkheid en braken (PONV). De verkoevertijd kan door het gebruik van een opioïde mogelijk (marginaal) verkort worden, dat wil zeggen dat in de gepoolde resultaten een gemiddeld verschil van 2 minuten ten faveure van de opioïde groep gevonden is. Dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Waarschijnlijk liggen de kosten van het gebruik van esketamine hoger dan die van de toevoeging van een kortwerkend opioïde zoals alfentanil of fentanyl.

Er zijn in de literatuur weinig aanwijzingen dat deze kosten opwegen tegen voordelen van het gebruik van esketamine. De kosten van de bestrijding van eventueel toegenomen incidentie van PONV door het gebruik van esketamine zijn daar nog bij te rekenen.

Hoewel er aanwijzingen zijn dat het gebruik van een opioïde kan leiden tot een kortere verkoevertijd moet er rekening mee gehouden worden dan het gemiddelde verschil in de gepoolde resultaten slechts 2 minuten betrof. Dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Vanuit patiënten perspectief moet rekening gehouden worden met de aanvaardbaarheid van een keuze voor esketamine wanneer gekend is dat dit de kans op post-procedurele misselijkheid en braken kan vergroten. Deze afweging moet gemaakt worden tegen het licht van een verkleining van het risico op apneu en hypotensie. Zowel esketamine als een scala aan kortwerkende opioïden zijn in Nederland voorhanden en verkrijgbaar. De beide middelen kunnen middels bolusinjectie en via infusor-pomp intraveneus worden toegediend en ze zijn beide verenigbaar met propofol bij intraveneuze toediening. De werkgroep voorziet daarom geen problemen op het gebied van haalbaarheid en implementatie voor het gebruik van beide middelen. Dit zal het beste op lokaal niveau geregeld kunnen worden. De werkgroep noemt hierbij nog wel expliciet de overweging van het kostenaspect zoals gemaakt in de voorgaande paragraaf.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Esketamine kan gebruikt worden in combinatie met propofol voor PSA bij volwassenen. Er is slechts bewijs van lage kwaliteit dat de keuze voor esketamine zal leiden tot een lagere incidentie van respiratoire of hemodynamische complicaties. Esketamine heeft een vergelijkbaar, mogelijk iets gunstiger veiligheidsprofiel in vergelijking met het gebruik van een opioïde. Hierbij moet rekening gehouden worden met het feit dat in de literatuur geen standaard aangehouden wordt voor de verhoudingen esketamine-propofol en opioïde-propofol. Het is denkbaar dat wanneer esketamine als primair analgosedativum wordt gebruikt en propofol wordt gebruikt als antipsychotropicum, de verschillen in effecten op ademhaling en bloeddruk maar ook de verschillen in het optreden van andere bijwerkingen uitvergroot worden. De literatuur biedt hiervoor echter momenteel te weinig eenduidigheid. Er zijn echter wel aanwijzingen dat het gebruik van esketamine kan leiden tot een hogere incidentie van PONV. Het gebruik van een opioïde zou kunnen leiden tot een kostenbesparing in de vorm van lagere medicijnkosten voor de sedatie en de bestrijding van PONV na de procedure. Aangezien dit kostenverschil per patiënt waarschijnlijk beperkt is zou deze afweging niet moeten leiden tot een keuze die voor individuele patiënten tot een verlaging van de veiligheid leidt.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Tijdens procedurele sedatie en analgesie (PSA) wordt doorgaans gebruik gemaakt van een combinatie van een sedativum en een analgeticum. Bekende combinaties zijn een sedativum als midazolam of propofol gecombineerd met een opioïde of esketamine. Vooral de combinaties van propofol met een opioïde of esketamine worden veel gebruikt voor matig/diepe sedatie (MD-PSA). Zowel esketamine als opioïden hebben voor- en nadelen op verschillende vlakken. Gezien het grootschalige toepassen van deze combinaties voor MD-PSA in Nederland acht de werkgroep het wenselijk waar mogelijk adviezen en aanbevelingen te formuleren ten aanzien van de relatieve geschiktheid van opioïden in combinatie met propofol of esketamine in combinatie met propofol.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Safety

|

Low GRADE |

It is likely that procedural sedation with esketamine and propofol may result in a lower incidence of respiratory depression, apnea, hypotension, and bradycardia compared to sedation with propofol with an opioid.

Sources: Akin, 2005; Singh, 2013 Sources: Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Hasanein, 2013 Sources: Eberl,2020; Hasanein, 2013; Kilic, 2016; Singh, 2013; Singh, 2018 Sources: Akin, 2005; Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013; Kilic, 2016; Sing, 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Procedural sedation with esketamine and propofol may result in little to no difference in incidence of desaturation, hypertension and tachycardia compared to sedation with propofol with an opioid.

Sources: Aminiahidashti, 2018; Eberl,2020; Hasanein, 2013; Singh, 2018 Sources: Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013 Sources: Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

It is likely that procedural sedation with esketamine and propofol may increase the incidence of nausea and vomiting compared to sedation with propofol with an opioid.

Sources: Akin, 2005; Bahrami Gorji, 2017; Hasanein, 2013; Khajavi, 2012; Kilic, 2016; Sing, 2013 |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether procedural sedation with esketamine and propofol results in a lower incidence of amnesia and psychological emergence compared to sedation with propofol with an opioid.

Source: Hwang, 2005 Source: Khajavi, 2012 |

Quality & effectiveness PSA

|

Low GRADE |

Procedural sedation with esketamine and propofol may result in little to no difference in recovery time compared to sedation with propofol with an opioid.

Sources: Akin, 2005; Bahrami Gorji, 2017; Hasanein, 2013; Khajavi, 2012; Kilic, 2016; Sing, 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Procedural sedation with esketamine and propofol may result in little to no difference in post-procedural pain compared to sedation with propofol with an opioid.

Sources: Aminiahidashti, 2018; Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Eberl, 2020; Kilic, 2016; Nazemroaya, 2018; Singh, 2013 |

Patient satisfaction

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether procedural sedation with esketamine and propofol may improve patient satisfaction compared to sedation with propofol with an opioid.

Sources: Akin, 2005; Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013; Hwang, 2005; Khajavi, 2012; Kilic, 2016; Singh, 2013 |

Operator satisfaction

|

Low GRADE |

Procedural sedation with esketamine and propofol may result in little to no difference in operator satisfaction compared to sedation with propofol with an opioid.

Sources: Aminiahidashti, 2018; Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Eberl, 2020; Kilic, 2016; Singh, 2018 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Akin (2005) conducted an RCT comparing the clinical activities of ketamine and fentanyl when used in combination with propofol for outpatients undergoing endometrial biopsy. Patients were randomized to an intervention group receiving intravenous doses of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) + propofol (1 mg/kg), or a control group receiving intravenous doses of fentanyl (1 µg/kg) + propofol (1 mg/kg). In total, 20 patients (mean age 47.5±10.4 years; mean weight 72.2±8.4 kg) were allocated to the intervention group and 20 patients (mean age 43.8±6.5 years; mean weight 70.2±11 kg) were allocated to the control group. Outcomes were heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, and peripheral O2 saturation were monitored in all patients. The time to Aldrete score ≥8, respiratory depression (respiratory rate ≤8 breaths per minute, apnea longer than 15 seconds, or Spo2 <90%), bradycardia (heart rate <45 beats per minute), pain on injection, hypotension (more than 20% decrease of the initial value), increased secretions, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and visual disturbances were recorded. Outcomes were recovery and discharge properties and observed adverse effects between the intervention and control group.

Aminiahidashti (2018) conducted an RCT comparing the efficacy of propofol and fentanyl combination with propofol and ketamine combination for procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) in trauma patients in the emergency department. Included in the study were patients with trauma presenting to the emergency department who needed PSA. Patients were randomized to either 1 mg/kg ketamine in 10 ml normal saline + 0.5 mg/kg propofol (intervention group) or 1 μg/kg fentanyl in 10 ml normal saline 0.5 mg/kg propofol (control). In total, 66 patients (mean age 33.77±9.22 years; 63.86% male), were allocated to the intervention group and 70 patients (mean age 31.71±8.76 years; 66.67% male) were allocated to the control group. depth of sedation was divided into four levels with Level 1 being minimal sedation, level 2 being moderate sedation, level 3 being deep sedation and level 4 being general anaesthesia. Severity of pain was categorized from 0 to 10 based on visual analogue scale (VAS), with 0 being no pain and 10 being worst possible pain. Physician satisfaction with PSA method was divided in 3 groups and categorized as Good, Moderate or Poor. Outcomes were level of sedation, severity of pain, and unexpected side-effects (changes in blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, O2 saturation, requiring intervention to maintain respiratory status), recovery time and physician satisfaction with PSA method

Bahrami Gorji (2016) conducted an RCT comparing the analgesic and sedative effects of propofol-ketamine versus propofol-fentanyl in patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Patients were randomly divided into a group receiving ketamine 0.5 mg/kg (intervention group), or a group receiving fentanyl 50 - 100 micrograms (control group). Both groups received propofol 0.5 mg/kg in a loading dose followed by 75 µg/kg/minute in an infusion. In total, 30 patients (mean age 56±19.75 years; 43% male) were allocated to the intervention group, and 42 patients (mean age 60.50±15.66 years; 48% male) were allocated to the control group. Outcomes were the quality of analgesia based on a VAS scale (0 = no pain and 10 = the worst pain) blood pressure, respiratory rate, heart rate, arterial oxygen saturation, recovery time (based on Aldrete scores >9), and endoscopist and patient satisfaction a VAS scale (0 = not satisfied and 10 = most satisfied).

Eberl (2020) conducted an RCT assessing the effectiveness of esketamine versus alfentanil as an adjunct to propofol target-controlled infusion (TCI) for deep sedation during ambulant ERCP. Included in the trial were adult (aged 18 years or older, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status I to III patients scheduled to undergo ERCP. Patients were randomly assigned to receive sedation for an ERCP with 150µg/kg esketamine (intervention group), or alfentanil (control group). Both groups were sedated using a TCI of propofol 1% to a target level of 1.5 µg/ml-1. In total, 83 patients (median age 63 years; IQR 52 to 73 years; 58% male) were allocated to the intervention group, and 79 patients (median age 58 years; IQR 43 to 70 years; 49% male) were allocated to the control group. Patients completed a survey directly before the intervention, every 15 min after the procedure in the recovery unit and on the first day after discharge. Pain and nausea were assessed using a VAS (0=no pain/no nausea to 100=worst imaginable pain or nausea). Perceptual changes were assessed using a VAS (0=normal to 100=extremely altered). Mood states were ranked between 0 and 100 in five categories (anxious to composed, hostile to agreeable, depressed to elated, tired to energetic and confused to clear-headed). Endoscopists rated their perception of the patient’s pain using the same VAS scale, sedation level (MOAA/S), and the ease of the procedure (grade 1= easy to grade 3=difficult). The endoscopists’ satisfaction was determined using a five-point Likert scoring system (1=very dissatisfied to 5=highly satisfied). Outcomes were recovery time (Modified Observer’s Alertness/Sedation Scale (MOAA/S) >4), sedation-related adverse events in entire group during entire procedure, cumulative dose of propofol, patient satisfaction, endoscopist satisfaction and endoscopist perception of pain.

Hasanein (2013) conducted an RCT comparing two techniques of sedation for obese patients undergoing ERCP, using either ketofol or fentanyl–propofol as regards propofol consumption, recovery time, patients’ satisfaction, and sedation-related adverse events. Included int this RCT were patients aged 18 or over with BMI 25-35 and ASA physical status I, II, or III. Patients were randomly allocated to ketamine 50 mg/ml (intervention group) or fentanyl 1.5 µg/kg (control group). Both groups were given as an initial bolus dose of 0.5 mg/kg propofol. In total, 100 patients (mean age 57.67±13.3 years; 49% male) were allocated to the intervention group, and 100 patients (mean age 56.93±11.9 years; 50% male) were allocated to the control group. Outcomes were sedation related side effects (hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia, tachycardia, apnea, SpO2 <90%), and time to Aldrete score ≥9. Patient’s satisfaction was assessed using a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) (0 =least satisfied, 100 = most satisfied). patients with score ≥75 were considered satisfied.

Hwang (2005) conducted an RCT comparing the clinical efficacy of propofol/ketamine with propofol/ alfentanil for patient-controlled sedation (PCS) during fibreoptic bronchoscopy. Patients undergoing fibreoptic bronchoscopy were randomly assigned to receive either 4.2 mg/l ketamine (intervention group), or 83 mg/ml alfentanil (control group) via a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) device for sedation and analgesia. Both groups also received 8.3 mg/l propofol. In total, 138 patients (mean age 58.3±1.3 years; 64% male) were allocated to the intervention group and 138 patients (mean age 57.4±12.7; 65% male) were allocated to the control group. Outcomes were the amnesia, sedation time, sedation level, injection pain, and safety. Patient’s satisfaction was assessed using a 10-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) (0 =least satisfied, 10 = most satisfied).

Khajavi (2012) conducted an RCT comparing the effects of, ketamine-propofol versus fentanyl-propofol for achieving a more acceptable satisfaction of the patients during colonoscopy procedures. Included in this RCT were patients older than 18 years with ASA physical statuses I, II or III. Patients were randomized to an intravenous bolus of 0.5mg/kg ketamine, or an intravenous bolus 1μg/kg fentanyl (control group). Both groups received 0.5mg/kg propofol. In total, 30 patients (mean age 55.9±15 years; 53% male) were allocated to the intervention group and 30 patients (mean age 51.6±21 years; 60% male) were allocated to the control group. The primary outcome was patient’s satisfaction assessed using a Likert five-item scoring system Comparisons of hemodynamic parameters (mean heart rate, mean systolic blood pressure, mean diastolic blood pressure), mean SPo2 values during the procedure and side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and psychological reactions during the recovery period were secondary outcomes.

Kilic (2016) conducted an RCT comparing the effects of both propofol/alfentanil and propofol/ketamine on sedation during upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy in morbidly obese patients. Include in this RCT were patients aged older than 18 years, with body mass index (BMI) between 45 and 60 kg/m2, and ASA physical status between II and III. Patients were randomized to 0.5 mg/kg intravenous ketamine (intervention group), or 10 μg/kg intravenous alfentanil (control group). Both groups received an intravenous dose of 0.7 mg/kg propofol. In total, 26 patients (mean age 36.7±8.7 years; 23% male) were allocated to the intervention group and 26 patients (mean age 33.5±9.8 years; 23% male) were allocated to the control group. The Modified Aldrete Score (MAS) was used to assess patient recovery. A Verbal Pain Scale (VPS) was used 5 and 10 minutes after the procedure to monitor pain. The scale was as follows: 0=no pain, 1=dull pain, 2=moderate pain, and 3=intense pain. Both the patients and the physicians were questioned regarding their satisfaction with the procedure. The scale was as follows: 0=not satisfied, 1=satisfied, and 2=very satisfied. Outcomes were recovery time and side effects (hypotension, bradycardia, and nausea/vomiting).

Nazemroaya (2018) conducted an RCT comparing two‑drug combinations of propofol–ketamine and propofol–fentanyl on quality of sedation and analgesia in lumpectomy. Included in this trial were patients aged 15–70 years with breast cancer lumpectomy and ASA physical status II or less. Patients were in two groups, one received 0.5 mg/kg of ketamine plus propofol 1 mg/kg (intervention group) and the other received 1 μg/kg of fentanyl with propofol at a dose of 1 mg/kg (control group). In total, 32 patients (mean age 43.31±16.09 years) were allocated to the intervention group and 32 patients (mean age 42.64±11.84 years) were allocated to the control group. Within and after operation, factors such as mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), HR, and arterial SPO2 were recorded. Patients’ pain intensity was also recorded based on visual analogue scale scoring system. Outcomes were comparison of pain and sedation of patients between two groups and the frequency of drug complications used in the two groups.

Singh (2013) conducted an RCT comparing postoperative recovery characteristics, duration of hospital stay, patient comfort and acceptability between ketamine–propofol and fentanyl–propofol for PSA in patients undergoing laparoscopic tubal ligation. Included in this RCT were patients aged 18-45 years with ASA physical status classification I scheduled to undergo laparoscopic tubal ligation. Patients were randomized to receive premixed injection of ketamine 0.5 mg/kg + propofol 2 mg/kg (intervention group), or fentanyl 1.5 µg/kg + propofol 2 mg/kg (control group). In total, 50 patients (mean age 28.74 years) were allocated to the intervention group and 50 patients (mean age 29.14 years) were allocated to the control group. Heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic pressure, mean arterial pressure, peripheral oxygen saturation, and respiratory rate were monitored and recorded. Hemodynamic parameters were monitored at 5-min intervals. Adverse events including desaturation (SpO2 < 95%), hypotension (mean blood pressure < 20% of baseline), and coughing were recorded. Outcomes were propofol consumption, time to achieve post anaesthesia discharge score of 10, and duration of procedure, and number of patients exhibiting adverse events. ECG and SpO2 were monitored continuously. Side effects such as respiratory depression (respiratory rate <8 breaths per minute, apnea longer than 15 seconds or SpO2<92%), hypotension (more than 20% decrease from the initial value), and bradycardia (heart rate <60 beats per minute), increased secretions, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, visual disturbances, delirium, pruritis and any other side effect were recorded. Outcomes were recovery time, discharge time, comfort score, and perioperative complications.

Singh (2018) conducted an RCT assessing the effect of the addition of fentanyl and ketamine on propofol consumption in patients undergoing endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Included in this RCT were patients aged over 18 years with ASA physical status classification I/II scheduled to undergo elective EUS under sedation. Patients were randomized into three groups. Patients were premedicated intravenously with normal saline (group 1), 50μg fentanyl (group 2), and 0.5 mg/kg ketamine (group 3). All patients received intravenous propofol for sedation. In total, 68 patients (mean age 45.9±15.6 years; 68% male) were allocated to group 1, 70 patients (mean age 49.3±14.5 years; 56% male) were allocated to group 2, and 72 patients (mean age 44.4±16.4 years; 64% male) were allocated to group 3. Propofol consumption in mg/kg/h was recorded. Hemodynamic parameters were monitored at 5-min intervals. Adverse events including desaturation (SpO2 < 95%), hypotension (mean blood pressure < 20% of baseline), and coughing were recorded. Outcomes were propofol consumption, time to achieve post anaesthesia discharge score of 10, and duration of procedure, and number of patients exhibiting adverse events.

Türk (2014) conducted an RCT comparing a ketofol mixture with an alfentanil-propofol combination on sedation quality during colonoscopy. Included in this RCT were patients aged between 18-65 years with ASA physical status I-II who were scheduled for elective colonoscopy procedure. Patients were randomized to 0.5 mg/kg ketamine +1 mg/kg propofol (intervention group), or 10 mg/kg alfentanil +1 mg/kg propofol (control group). In total, 35 patients (mean age 49±10.01 years)) were allocated to the intervention group, and 35 patients (mean age 49.26±13.11 years) were allocated to the control group. Heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and Ramsey Sedation Scale (RSS) scores were recorded before, at the beginning, and at every 5-minute interval throughout the colonoscopy procedure. Colonoscopy duration included the overall time of the colonoscopy procedure. Recovery time was stipulated as the time from induction until RSS score progressed to 2. At the end of the procedure, patients were discharged when the Aldrete Score was 9 or higher. Colonoscopist’s and each patient’s satisfaction were scored on a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 1 to 10 and recorded. Outcomes were Colonoscopy duration, additional propofol requirement, total propofol consumption, complication rate, and recovery-discharge time.

Results

Safety

Respiratory depression

Two studies reported on respiratory depression (Akin, 2005; Singh, 2013).

Akin (2005) found that respiratory depression (defined as respiratory rate ≤8 breaths per minute, apnea longer than 15 seconds, or SpO2 <90%), was observed in 1/20 patient (5%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 5/29 patients (25%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The risk ratio (RR) was 0.20 (95% CI 0.03 to 1.56)in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Singh (2013) found that respiratory depression (defined as respiratory rate ≤8 breaths per minute, apnea longer than 15 seconds, or SpO2 <92%) was observed in 17/50 patient (34%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 18/50 patients (36%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 0.94 (95%CI 0.55 to 1.61) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘respiratory depression’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels level because of imprecision (low number of events and 95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance; -2) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Apnea

Two studies reported on apnea (Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Hasanein, 2013).

Bahrami Gorji (2016) found that apnea was observed in 1/30 patient (3%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 7/42 patients (17%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 0.20 (95% CI 0.03 to 1.54) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Hasanein (2013) found that apnea was observed in 2/100 patient (2%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 10/100 patients (10%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 0.20 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.89) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘apnea’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of risk of bias (inadequate blinding; -1) and imprecision (low number of events and 95% confidence intervals crossing both borders for clinical relevance; -1 resulting in a low level of evidence.

Desaturation

Four studies reported on desaturation (Aminiahidashti, 2018; Eberl,2020; Hasanein, 2013; Singh, 2018)

Aminiahidashti (2018) found that desaturation (SpO2 <90%), was observed in 4/66 patient (6%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 7/70 patients (10%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The risk ratio (RR) was 0.61 (95% CI 0.19 to 1.98) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

Eberl (2020) found that desaturation (defined as SpO2 75 to 90%) was observed in 11/83 patient (13%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 7/79 patients (9%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RR was 1.50 (95%CI 0.61 to 3.66) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group.

Hasanein (2013) found that desaturation (defined as SpO2 <90%) was observed in 0/100 patient (0%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 7/100 patients (7%) in the propofol+fentanyl group.

Singh (2018) found that desaturation (defined as SpO2 <95%) was observed in 5/72 patient (7%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 4/70 patients (6%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 1.22 (95%CI 0.34 to 4.34) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

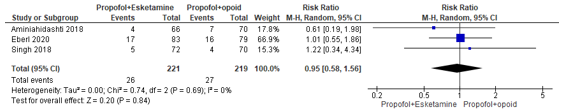

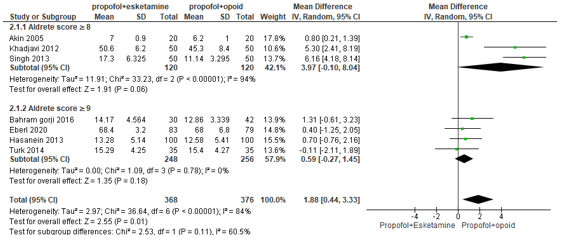

In summary, there were four studies that reported desaturation, but definitions for desaturations varied from an oxygen saturation (SpO2) of <95% to <90%. The RR could only be estimated for three studies, and these were pooled. The pooled RR was 0.95 (95% CI 0.58 to 1.756; Figure 1) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between sedation using propofol+esketamine relative to sedation using propofol+opioid for desaturation. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘desaturation’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of inconsistency (conflicting results and inconsistency in definition of desaturation; -1) imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance; -1) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Hypotension

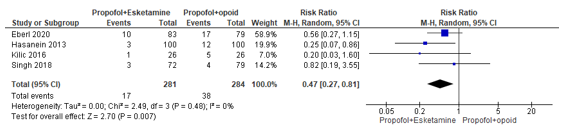

Five studies reported on hypotension (Eberl,2020; Hasanein, 2013; Kilic, 2016; Singh, 2013; Singh, 2018).

Eberl (2020) found that hypotension (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 10/83 patient (12%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 17/79 patients (22%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RR was 0.56 (95% CI 0.27 to 1.15) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

Hasanein (2013) found that hypotension (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 3/100 patient (3%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 12/100 patients (12%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 0.25 (95% CI 0.07 to 0.86) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

Kilic (2016) found that hypotension (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline or blood pressure <90 mmHg) was observed in 1/26 patient (4%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 5/26 patients (19%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RR was -0.20 (95% CI 0.03 to 1.60) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

Singh (2013) found that hypotension (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 0/50 patient (3%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 1/50 patients (2%) in the propofol+fentanyl group.

Singh (2018) found that hypotension (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 3/72 patient (4%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 4/70 patients (6%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 0.82 (95%CI 0.19 to 3.55) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

In summary, there were five studies that reported hypotension. The RR could only be estimated for four studies, and these were pooled. The pooled RR was 0.47 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.81; Figure 2) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the comparison between sedation using propofol+esketamine relative to sedation using propofol+opioid for hypotension. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘hypotension’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of inconsistency (conflicting results; -1) imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance; -1) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Hypertension

Two studies reported on hypertension (Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013).

Eberl (2020) found that hypertension (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 17/83 patient (20%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 17/79 patients (22%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RR was 0.95 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.73) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Hasanein (2013) found that hypertension (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 2/100 patient (20%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 0/100 patients (0%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The risk difference (RD) was 0.02 (95% CI -0.01 to 0.05) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘hypertension’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of inconsistency (conflicting results; -1) imprecision (confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance and a low number of events; -1) resulting in a low level of evidence

Bradycardia

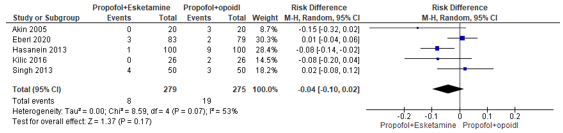

Five studies reported on bradycardia (Akin, 2005; Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013; Kilic, 2016; Sing, 2013).

Akin (2005) found that bradycardia (defined as heart rate <45 beats per minute), was observed in 0/20 patients (0%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 3/20 patients (15%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RD was -0.15 (95% CI -0.32 to 0.02) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

Eberl (2020) found that bradycardia (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 3/83 patient (4%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 2/79 patients (3%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RD was 0.01 (95% CI -0.04 to 0.06) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group.

Hasanein (2013) found that bradycardia (defined as heart rate <55 beats per minute) was observed in 1/100 patient (1%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 9/100 patients (9%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RD was -0.08 (95% CI -0.20 to 0.04) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

Kilic (2016) found that bradycardia (defined as heart rate <50 beats per minute) was observed in 0/26 patient (0%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 2/26 patients (8%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RD was -0.08 (95% CI -0.20 to 0.04) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

Singh (2013) found that bradycardia (defined as heart rate <60 beats per minute) was observed in 4/50 patient (8%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 3/50 patients (6%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RD was 0.02 (95% CI -0.08 to 0.12) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

In summary, there were five studies that reported bradycardia. The pooled RD was -0.04 (95% CI -0.10 to 0.02; Figure 3) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the comparison between sedation using propofol+esketamine relative to sedation using propofol+opioid for bradycardia. Pooled risk difference, random effects model.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘bradycardia’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of inconsistency (conflicting results and inconsistency in definition of desaturation; -1) imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance and a low number of events; -1) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Tachycardia

Two studies reported on tachycardia (Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013).

Eberl (2020) found that tachycardia (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 17/83 patient (20%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 16/79 patients (20%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RR was 1.01 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.86). This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Hasanein (2013) found that tachycardia (defined as change of more than 20% from baseline) was observed in 3/100 patient (3%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 1/100 patients (1%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RD was 0.02 (95% CI -0.02 to 0.06) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘tachycardia’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance and a low number of events; -2) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Nausea and vomiting

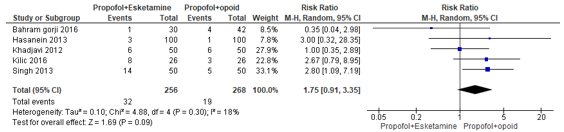

Six studies reported on nausea and vomiting (Akin, 2005; Bahrami Gorji, 2017; Hasanein, 2013; Khajavi, 2012; Kilic, 2016; Sing, 2013).

Akin (2005) found that nausea and vomiting, was observed in 7/20 patients (35%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 0/20 patients (0%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RD was 0.35 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.57) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Bahrami Gorji (2016) found that nausea and vomiting, was observed in 1/30 patients (3%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 4/42 patients (10%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 0.35 (95% CI 0.04 to 2.98) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

Hasanein (2013) found that nausea and vomiting, was observed in 3/100 patients (3%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 1/100 patients (1%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 3.00 (95% CI 0.32 to 28.35) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Khajavi (2012) found that nausea and vomiting, was observed in 6/50 patients (12.5%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 6/50 patients (12.5%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RR was 1.00 (95% CI 0.35 to 2.89).

Kilic (2016) found that nausea and vomiting, was observed in 8/26 patients (31%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 3/26 patients (12%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RR was 2.67 (95% CI 0.79 to 8.95) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group.

Singh (2013) found that nausea and vomiting, was observed in 14/50 patients (28%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 5/50 patients (10%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 2.80 (95% CI 1.09 to 7.19) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

In summary, there were six studies that reported nausea and vomiting. The RR could only be estimated for five studies, and these were pooled. The pooled RR was 1.75 (95% CI 0.91 to 3.35; Figure 4) in favour of the propofol+opioid group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the comparison between sedation using propofol+esketamine relative to sedation using propofol+opioid for nausea and vomiting. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘nausea and vomiting’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of inconsistency (conflicting results; -1) imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance; -1) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Amnesia

Only one study reported on amnesia (Hwang, 2005).

Hwang (2005) found that visual amnesia, was observed in 113/138 patients (82%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 84/138 patients (61%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RR was 1.35 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.57) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group. This is a clinically relevant difference

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘psychological emergence’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of risk of bias (inadequate blinding; -1) imprecision (95% confidence interval crossing border for clinical relevance, and only one study reporting the outcome with a low number of events; -2) resulting in a very low level of evidence.

Psychological emergence

Only one study reported on psychological emergence (Khajavi, 2012).

Khajavi (2012) found that psychological emergence, was observed in 3/50 patients (7.5%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 0/50 patients (0%) in the propofol+alfentanil group. The RD was 0.06 (95% CI -0.01 to 0.13) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘psychological emergence’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of risk of bias (inadequate blinding; -1) imprecision (95% confidence interval crossing border for clinical relevance, and only one study reporting the outcome with a low number of events; -2) resulting in a very low level of evidence.

Quality & effectiveness PSA

Recovery time

Eight studies reported on recovery time after procedure (Akin, 2005; Aminiahidashti, 2018; Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013; Khajavi, 2012; Singh, 2013; Türk, 2013).

Akin (2005) defined recovery time as reaching an Aldrete score ≥8. They found that the mean recovery time was 7.0±0.9 minutes in the propofol+esketamine group and 6.2±1.0 minutes in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was 0.80 minutes (95% CI 0.21 to 1.39) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Aminiahidashti (2018) defined recovery time as the time interval between drug injection and the time when the patient leaves the recovery room and does not require accurate and close monitoring anymore. The estimated mean recovery time was 25.5±6.39 minutes in the propofol+esketamine group and 24±6.33 minutes in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was 1.50 minutes (95% CI -0.64 to 3.64) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Bahrami Gorji (2016) defined recovery time as reaching an Aldrete score ≥9. They found that the mean recovery time was 14.17±4.564 minutes in the propofol+esketamine group and 12.86±3.339 minutes in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was 1.31 minutes (95% CI -0.61 to 3.23) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Eberl (2020) defined recovery time as reaching an Aldrete score ≥9. The estimated mean recovery time was 68.4±3.2 minutes in the propofol+esketamine group and 68±6.8 minutes in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference is 0.40 (95% CI-1.25 to 2.05) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group.

Hasanein (2013) defined recovery time as reaching an Aldrete score ≥9. They found that the mean recovery time was 13.28±5.14 minutes in the propofol+esketamine group and 12.58±5.41 minutes in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was 0.70 minutes (95% CI -0.76 to 2.16) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Khajavi (2012) defined recovery time as reaching an Aldrete score ≥8. They found that the mean recovery time was 50.6±6.2minutes in the propofol+esketamine group and 45.3±8.4 minutes in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference was 5.30 minutes (95% CI 2.41 to 8.19) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group.

Singh (2013) defined recovery time as reaching an Aldrete score ≥8. They found that the mean recovery time was 17.3±6.325 minutes in the propofol+esketamine group and 11.14±3.295 minutes in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was 6.16 minutes (95% CI 4.18 to 8.14) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Türk (2013) defined recovery time as reaching an Aldrete score ≥9. They found that the mean recovery time was 15.29±4.25 minutes in the propofol+esketamine group and 15.4±4.27 minutes in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference was -0.11 minutes (95% CI -2.11 to 1.89) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group.

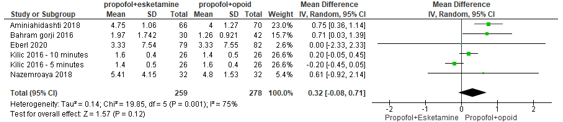

In summary, there were eight studies that reported time to recovery of whom three defined recovery time as reaching an Aldrete score ≥8 and four defined as an Aldrete score ≥9. One study did not mention the use of the Aldrete score to define time to recovery (Aminiahidashti, 2018). The pooled mean difference of the four studies that defined recovery as reaching an Aldrete score ≥8 was 3.97 minutes (95% CI -0.10 to 8.04; Figure 5) in favour of the propofol+opioid group. The pooled mean difference of the four studies that defined recovery as reaching an Aldrete score ≥9 was 0.59 minutes (95% CI -0.27 to 1.45; Figure 5) in favour of the propofol+opioid group. The overall pooled mean difference of the seven studies that did use the Aldrete score to define time to recovery were pooled studies was 1.88 minutes (95% CI 0.44 to 3.33; Figure 5) in favour of the propofol+opioid group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 5. Forest plot showing the comparison between sedation using propofol+esketamine relative to sedation using propofol+opioid for time to recovery. Pooled mean difference, random effects model.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘recovery’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of risk of bias (inadequate blinding; -1) and imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance; -1) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Pain

Seven studies reported on the experience of pain after procedure (Aminiahidashti, 2018; Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Eberl, 2020; Kilic, 2016; Nazemroaya, 2018; Singh, 2013).

Aminiahidashti (2018) measured pain on a 0-10mm VAS scale (0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain). The estimated mean pain score after 120 minutes of PSA was 4.75±1.06 in the propofol+esketamine group and 4±1.27 in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was 0.75 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.03) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Bahrami Gorji (2016) measured post-procedural pain on a 0-10mm VAS scale (0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain). They found that mean post-procedural pain was 1.97±1.742 in the in the propofol+esketamine group and 1.26±0.921 in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was 0.71 (95% CI 0.03 to 1.39) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Eberl (2020) measured endoscopist perception of pain on a 0-10mm VAS scale (0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain). The estimated mean pain score was 3.33±7.54 (IQR 0-10) in the in the propofol+esketamine group and 3.33±7.55 in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference was 0.00 (95% CI -2.32 to 2.32).

Kilic (2016) measured pain on a three-point verbal pain scale 5 and 10 minutes after the procedure (0=no pain, 1=dull pain, 2=moderate pain, and 3=intense pain). They found that the mean verbal pain score after 5 minutes was 1.4±0.5 in the propofol+esketamine group and 1.6±0.4 in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference was -0.20 (95% CI -0.05 to 0.45) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. The mean verbal pain score after 10 minutes was 1.6±0.4 in the propofol+esketamine group and 1.4±0.5 in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference was 0.20 (95% CI -0.05 to 0.45) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group.

Nazemroaya (2018) measured post-procedural pain on a 0-10mm VAS scale (0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain). They found that mean post-procedural pain was 5.41±4.15 in the in the propofol+esketamine group and 4.8±1.53 in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was 0.61 (95% CI -0.92 to 2.14) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group.

Singh (2013) measured pain on a 10mm VAS scale (0=no pain and 10=worst possible pain; pain was defined as a VAS ≥3). They found that 16/50 patients (32%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 13/50 patients (26%) in the propofol+fentanyl group reported pain. The RR was 1.23 (95% CI 0.66 to 2.28) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group. This is not a clinically relevant difference

In summary, there were seven studies that reported on pain post procedure using a VAS scale, of whom six could be pooled. The pooled mean difference was 0.32 (95% CI -0.08 to 0.71; Figure 6) in favour of the propofol+opioid group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 6. Forest plot showing the comparison between sedation using propofol+esketamine relative to sedation using propofol+opioid for pain post-procedure on a VAS scale. Pooled mean difference, random effects model.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘pain’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of risk of bias (inadequate blinding; -1) and imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance; -1) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Patient satisfaction

Eight studies reported on patient satisfaction (Akin, 2005; Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Eberl, 2020; Hasanein, 2013; Hwang, 2005; Khajavi, 2012; Kilic, 2016; Singh, 2013).

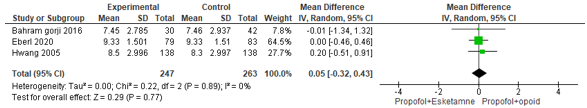

Three of these eight studies reported patient satisfaction using a VAS scale (Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Eberl, 2020; Hwang, 2005)

Bahrami Gorji (2016) measured patient satisfaction on a 0-10mm VAS scale (0 = not satisfied and 10 = most satisfied). They found that mean patient satisfaction was 7.45±2.785 in the in the propofol+esketamine group and 7.46±2.937 in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was -0.01 (95% CI -1.34 to 1.32).

Eberl (2020) measured patient satisfaction on a 0-100mm VAS scale (0 = not satisfied and 100 = most satisfied). The estimated mean patient satisfaction was 93.3±15.01 in the in the propofol+esketamine group and 93.3±15.10 in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference was 0.00 (95% CI -4.64 to 4.64).

Hwang (2005) measured patient satisfaction on a 0-10mm VAS scale (0 = not satisfied and 10 = most satisfied). The estimated mean patients satisfaction was 8.5±2.996 in the in the propofol+esketamine group and 8.3±2.997 in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference was 0.20 (95% CI -0.51 to 0.91) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group.

These three studies were pooled and the pooled mean difference was 0.05 (95% CI -0.32 to 0.43; Figure 7) in favour of the propofol+opioid group. This is not a clinical relevant difference.

Figure 7. Forest plot showing the comparison between sedation using propofol+esketamine (experimental) relative to sedation using propofol+opioid (control) for patient satisfaction on a VAS scale. Pooled mean difference, random effects model.

Akin (2005) found that 12/20 patients (60%) in the propofol+esketamine group rated the

anesthesia as successful and stated that they would prefer the same regimen in the future, compared to 19/20 patients (95%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 0.63 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.92) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Hasanein (2013) measured patient satisfaction using a 100-mm VAS scale (0 =least satisfied, 100 = most satisfied). Only patients with score ≥75 were considered satisfied. They found that 90/100 patient (90%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 91/100 patients (91%) in the propofol+fentanyl group were satisfied. The RR was 1.01 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.11) in favour of the esketamine+fentanyl group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Khajavi (2012) measured patient satisfaction on 5-point Likert scale (0 = not satisfied and 5 = very satisfied). They found that mean patient satisfaction score was 3.9±0.5 in the in the propofol+esketamine group and was 1.8±0.4 in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference was 2.10 (95% CI 1.92 to 2.28) in favour of the propofol+esketamine group. This is a clinically relevant difference

Kilic (2016) questioned patients regarding their satisfaction with the procedure using a three-point scale (0=not satisfied, 1=satisfied, and 2=very satisfied). They found that 25/26 (99%) patients in the propofol+esketamine group and 26/26 patients (100%) in the propofol+alfentanil group were satisfied or very satisfied. The RR was 0.96 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.07) in favour of the propofol+alfentanil group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Singh (2013) reported patient satisfaction using a five-point comfort score (1, very unpleasant; 2, unpleasant; 3, neither pleasant nor unpleasant; 4, pleasant; 5, very pleasant). The mean comfort score was 2.9±0.61 in the propofol+esketamine and 3.46±0.7 in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was -0.56 (95%CI -0.82 to -0.30) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘patient satisfaction’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of risk of bias (inadequate blinding; -1), inconsistency (conflicting results and inconsistency in definition of patient satisfaction; -1) imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance; -1) resulting in a very low level of evidence.

Operator satisfaction

FIve studies reported on operator satisfaction (Aminiahidashti, 2018; Bahrami Gorji, 2016; Eberl, 2020; Kilic, 2016; Singh, 2018).

Aminiahidashti (2018) found that physicians rated the anesthesia as good in 59/66 patients (89%) in the propofol+esketamine group, compared to 63/70 patients (90%) in the propofol+fentanyl group. The RR was 0.99 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.11) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Bahrami Gorji (2016) measured endoscopist satisfaction on a 0-10mm VAS scale (0 = not satisfied and 10 = most satisfied). They found that mean endoscopist satisfaction was 7.91±1.242 in the in the propofol+esketamine group and 7.93±1.118 in the propofol+fentanyl group. The mean difference was -0.02 (95% CI -0.58 to 0.54) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Eberl (2020) measured endoscopist satisfaction on 5-point Likert scale (0 = not satisfied and 5 = very satisfied). The estimated endoscopist satisfaction was 4.67±0.75 in the in the propofol+esketamine group and 4.67±0.76 in the propofol+alfentanil group. The mean difference is 0.00 (95% CI -0.23 to 0.23).

Kilic (2016) questioned physicians regarding their satisfaction with the procedure using a three-point scale (0=not satisfied, 1=satisfied, and 2=very satisfied). They found that physicians were satisfied with sedation of 26/26 patients (100%) in the propofol+esketamine group and 26/26 patients (100%) in the propofol+alfentanil group.

Singh (2018) questioned physicians regarding their satisfaction with the procedure using a three-point scale (0=Poor, 1=Average, and 2=Good). They found that no procedures in poor in any group. Physicians rated 60/72 procedures (83%) in the propofol+esketamine and 62/70 procedures (87%) in the propofol+fentanyl group as good. The RR was 0.94 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.07) in favour of the propofol+fentanyl group. This is not a clinically relevant difference.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding ‘operator satisfaction’ came from RCTs and started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of risk of bias (inadequate blinding; -1) and imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance; -1) resulting in a low level of evidence.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of procedural sedation with propofol combined with esketamine compared to sedation with propofol combined with an opioid on the safety, patient satisfaction, efficiency and quality of PSA in patients undergoing PSA?

P: patients undergoing PSA outside of the IC

I: sedation with propofol and esketamine

C: sedation with propofol and an opioid

O: safety of PSA, patient satisfaction, quality and efficiency of PSA, operator satisfaction

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered safety as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and quality and effectiveness, patient satisfaction, and operator satisfaction as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions as were used in the respective studies.

The working group defined a limit of 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR <0.8 or >1.25) and 10% for continuous outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. For recovery time, a difference of 15 minutes was considered as clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from the 1st of January 2005 until the 28th of April 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 300 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (with meta-analyses) and randomized controlled trials (RCT), investigating the effect of procedural sedation with propofol and esketamine compared to sedation with propofol and an opioid on the safety, patient satisfaction, efficiency and quality of PSA in patients undergoing PSA. Forty-one studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 29 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 12 studies were included.

Results

A total of twelve RCTs was included in this literature summary.

Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Akin, A., Guler, G., Esmaoglu, A., Bedirli, N., & Boyaci, A. (2005). A comparison of fentanyl-propofol with a ketamine-propofol combination for sedation during endometrial biopsy. Journal of clinical anesthesia, 17(3), 187-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.06.019

- Aminiahidashti, H., Shafiee, S., Hosseininejad, S. M., Firouzian, A., Barzegarnejad, A., Kiasari, A. Z., Kerigh, B. F., Bozorgi, F., Shafizad, M., & Geraeeli, A. (2018). Propofol-fentanyl versus propofol-ketamine for procedural sedation and analgesia in patients with trauma. The American journal of emergency medicine, 36(10), 1766-1770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.080

- Bahrami Gorji, F., Amri, P., Shokri, J., Alereza, H., & Bijani, A. (2016). Sedative and Analgesic Effects of Propofol-Fentanyl Versus Propofol-Ketamine During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology and pain medicine, 6(5), e39835. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.39835

- Eberl, S., Koers, L., van Hooft, J., de Jong, E., Hermanides, J., Hollmann, M. W., & Preckel, B. (2020). The effectiveness of a low-dose esketamine versus an alfentanil adjunct to propofol sedation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A randomised controlled multicentre trial. European journal of anaesthesiology, 37(5), 394-401. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000001134

- Hasanein, R. & El-Sayed, W. (2013) Ketamine/propofol versus fentanyl/propofol for sedating obese patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia, 29:3, 207-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egja.2013.02.009

- Hwang, J., Jeon, Y., Park, H. P., Lim, Y. J., & Oh, Y. S. (2005). Comparison of alfetanil and ketamine in combination with propofol for patient-controlled sedation during fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 49(9), 1334-1338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00842.x

- Khajavi, M., Emami, A., Etezadi, F., Safari, S., Sharifi, A., & Shariat Moharari, R. (2013). Conscious Sedation and Analgesia in Colonoscopy: Ketamine/Propofol Combination has Superior Patient Satisfaction Versus Fentanyl/Propofol. Anesthesiology and pain medicine, 3(1), 208-213. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.9653

- Kılıc , E., Demiriz, B., Is?kay, N., Y?ld?r?m, A. E., Can, S., & Basmac?, C. (2016). Alfentanil versus ketamine combined with propofol for sedation during upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy in morbidly obese patients. Saudi medical journal, 37(11), 1191-1195. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2016.11.14557

- Nazemroaya, B., Majedi, M. A., Shetabi, H., & Salmani, S. (2018). Comparison of Propofol and Ketamine Combination (Ketofol) and Propofol and Fentanyl Combination (Fenofol) on Quality of Sedation and Analgesia in the Lumpectomy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Advanced biomedical research, 7, 134. https://doi.org/10.4103/abr.abr_85_18

- Singh, R., Ghazanwy, M., & Vajifdar, H. (2013). A randomized controlled trial to compare fentanyl-propofol and ketamine-propofol combination for procedural sedation and analgesia in laparoscopic tubal ligation. Saudi journal of anaesthesia, 7(1), 24-28. https://doi.org/10.4103/1658-354X.109801

- Singh, S. A., Prakash, K., Sharma, S., Dhakate, G., & Bhatia, V. (2018). Comparison of propofol alone and in combination with ketamine or fentanyl for sedation in endoscopic ultrasonography. Korean journal of anesthesiology, 71(1), 43-47. https://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2018.71.1.43

- Türk, H. Ş., Aydoğmuş, M., Ünsal, O., Işıl, C. T., Citgez, B., Oba, S., & Açık, M. E. (2014). Ketamine versus alfentanil combined with propofol for sedation in colonoscopy procedures: a randomized prospective study. The Turkish journal of gastroenterology : the official journal of Turkish Society of Gastroenterology, 25(6), 644-649. https://doi.org/10.5152/tjg.2014.7014

Evidence tabellen

1. Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Akin, 2005

|

Type of study: parallel group, randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Hospital, Turkey

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged between 38 years and 61 with American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) physical status I and II undergoing elective endometrial biopsy

Exclusion criteria: Patients who took sedatives in the last 24 hours, had neurological problems, or had been receiving treatment of psychiatric, cardiac, or pulmonary diseases

N total at baseline: Total: 40 Intervention:20 Control: 20

Important prognostic factors2: Intervention/Control

Age (mean ± SD), years 43.8±6.5/47.5±10.4

Weight (mean ± SD), kg: 70.2±11/72.2±8.4

Height (mean ± SD), cm 160.6±3.5/160±4.7

Endometrial biopsy time (mean ± SD), min 8.40±1.74/8.62±1.83

Total dose of propofol (mean ± SD), mg 78.3±10.3/80.4±9.2

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention: Patients received intravenous bolus doses of ketamine 0.5 mg/kg and propofol 1 mg/kg |

Describe control: Patients received intravenous bolus doses of fentanyl 1µg/kg and propofol 1 mg/kg |

Length of follow-up: No follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data

|

Outcome measures and effect size

Respiratory depression; RR (95%CI) 0.61 (0.19 to 1.98)

Bradycardia; RD (95%CI) -0.15 (-0.32 to 0.02)

Nausea and vomiting; RD (95%CI) 0.35 (0.13 to 0.57)

Recovery time (min); MD (95%CI) 0.80 (0.21 to 1.39)

Patient satisfaction; RR (95%CI) 0.63 (0.44 to 0.92) |

The authors conclude that propofol+fentanyl and ketamine-fentanyl combinations can be used safely in patients undergoing endometrial biopsy. However, with regard to side effects and patient satisfaction, the propofol+fentanyl was superior

RoB: Patients were randomized to 2 groups via sealed envelope assignment.

|

|

Aminiahidashti, 2018

(IRTC 2016112224606) |

Type of study: parallel group, randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Hospital, Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged between 18 years and 60 with American Society of ASA physical status I and II referred to the emergency department and needed PSA

Exclusion criteria: Patients under 18 and over 60 years old, patients with ASA physical status classification of 3 or above, intoxicated trauma patients, patients with head trauma, patients with addiction history, pregnant women, patients with blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg, pulse oximetry lower than 90%, pulse rate lower than 60 and patients with allergies or contraindications for fentanyl, propofol and ketamine

N total at baseline: Total: 136 Intervention:66 Control: 70

Important prognostic factors2: Intervention/Control

Age (mean ± SD), years 31.71±8.76/33.77±9.22

Male, n (%) 44(66.67)/44(62.86)

Female, n (%) 22(33.33)/26(37.14)

ASA 1, n (%) 57(86.36)/64(91.43)

ASA 2, n (%) 9(13.64)/6(8.57)

Diagnosis dislocation, n (%) 30(45.45)/ 27(38.57)

Diagnosis fracture (FX), n(%) 25(37.88)/30(42.86)

Diagnosis laceration repair, n (%) 9(13.64)/ 13(18.57)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention:

1 mg/kg ketamine in 10ml normal saline and 0.5 mg/kg propofol |

Describe control:

1 μg/kg fentanyl in 10ml normal saline and 0.5 mg/kg propofol |

Length of follow-up: No follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data

|

Outcome measures and effect size

Desaturation, RR (95% CI) 0.20 (0.03 to 1.56)

Recovery (min), MD (95%CI) 1.50 (-0.64 to 3.64

Pain 120 min PSA, MD (95% CI) 0.75 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.03)

Operator satisfaction; RR (95% CI) 0.99 (0.89 to 1.11) |

The authors conclude that propofol and fentanyl caused better analgesia and deeper sedation and it is recommended for use in emergency departments. Although there were undesirable side-effects, they have not been clinically considerable and have no effect on satisfaction and recovery time, and the pain is significantly reduced after PSA

RoB: Randomization was performed using a computer assisted randomization table. Propofol was administered in both groups but ketamine and fentanyl were prepared in two separate syringes only labeled with a number, each patient was assigned a number by the emergency department pharmaceutic nurse based on randomization table and based on that number, a syringe was ordered by the resuscitation room nurse who was unaware of the type of the medication. |

|

Bahrami Gorji, 2016

(IRCT201410187752N6) |

Type of study: parallel group, randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Hospital, Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged between 30 years and 70 with ASA physical status I and II referred for elective Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

Exclusion criteria: Neurological, mental, pulmonary, or heart disorders; a short, thick neck; liver disease (Child-Pugh classification C); a history of gastrointestinal surgery; addiction; ASA class 3 or 4; pregnancy; known hypersensitivity to any of the study medications; and acute gastrointestinal bleeding.

N total at baseline: Total: 72 Intervention:30 Control: 42

Important prognostic factors2: Intervention/Control

Age (mean ± SD), years 56±19.75/60.50±15.66

Male, n (%) 13(43)/20(48)

Female, n (%) 17(57)/22(52)

Basic MAP mmHg (mean±SD), 90.75±27.613/94.84±19.263

Basic respiratory rate (mean ± SD), min 12.31±0.780/12.30±0.988

Basic SaO2 (mean ± SD), % 97.33±2.52/97.70±1.87

Basic heart rate (mean ± SD), min 83.8±15.147/85.37±15.199

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention: 0.5 mg/kg ketamine and 0.5 mg/kg propofol |

Describe control: 50-100 μg/kg fentanyl and 0.5 mg/kg propofol |

Length of follow-up: No follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data

|

Outcome measures and effect size

Apnea; RR (95 %CI) 0.20 (0.03 to 1.54)

Nausea and vomiting; RD (95% CI) -0.06 (-0.17 to 0.05)

Recovery time; MD (95% CI) 1.31(-0.61 to 3.23)

Pain (VAS), MD (95 %CI) 0.71 (0.03 to 1.39)

Patient satisfaction (VAS), MD (95 %CI) -0.01 (-1.34 to 1.32)

Operator satisfaction (VAS), MD (95 %CI) -0.02 (-0.58 to 0.54) |

The authors conclude that the sedative effects of propofol-fentanyl and propofol-ketamine were acceptable and equal. Pain after ERCP in the propofol-fentanyl group was less than in the propofol-ketamine group. Patient and endoscopist satisfaction and recovery time showed no differences between the two groups

RoB: Randomization method was not described |

|

Eberl, 2020

(NTR5486) |

Type of study: parallel group, randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Hospital, Netherlands

Funding and conflicts of interest: No specific funding reported

No conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged over 18 with ASA physical status I to III referred for elective Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

Exclusion criteria: known allergic reaction to planned medication, a history of unregulated or malignant hypertension, significant ischaemic heart disease, psychiatric disease, chronic pain, pregnancy, seizure disorders, increased intracranial pressure, substance abuse or use of drugs that affect the central nervous system

N total at baseline: Total: 162 Intervention:83 Control: 79

Important prognostic factors2: Intervention/Control

Age median (IQR), years 63 (52-73)/58 (43-70)

Male, n (%) 48(58)/39(49)

Weight (kg); median (IQR) 76 (68.5-88.5)/79 (67-88)

Length (cm); median (IQR) 177 (168-184)/176 (1.70-1.81)

ASA PS; median (IQR 2 (1-2)/2 (2-2)

Cardiovascular disease 13 (15%)/5 (6.3%)

Pulmonary disease; n (%) 11 9 (10.8%)/(13.9%)

Diabetes; n (%) 12 (14.4%)10 (12.7%)

Smoker; n (%) 9 (10.8%)/10 (12.7%)

Alcohol; n (%) 32 (38.6%)/31 (39.2%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention: 150 μg/kg ketamine and 1.5 µg/ml propofol |

Describe control: 2 μg/kg alfentanil and 1.5 µg/ml propofol |

Length of follow-up: No follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data

|

Outcome measures and effect size

Desaturation; RR (95% CI) 1.50 (0.61 to 3.66)

Hypotension; RD (95%CI) -0.09 (-0.21 to 0.02)

Hypertension; RR (95%CI) 0.95 (0.52 to 1.73)

Bradycardia; RD (95%CI) -0.01 (-0.04 to 0.06)

Tachycardia; RR (95%CI) 1.01 (0.55 to 1.86)

Recovery (min); MD (95 %CI) 0.40 (-1.25 to 2.05 Pain (VAS); MD (95%CI) 0.00 (-2.32 to 2.32)

Patient satisfaction (VAS); MD(95 %CI) 0.00 (-4.65 to 4.65).

Operator satisfaction; MD (95 %CI) 0.00 (-0.23 to 0.23)

|

The authors conclude that propofol-esketamine significantly reduces total propofol requirement for ERCP in ASA PS I and II patients without effect on recovery time, endoscopists’ and patients’ satisfaction or cardiorespiratory adverse effects compared with a deep sedation regimen with propofol-alfentanil

RoB: Patients were randomised by the sedation practitioner using the online ALEA software program for centralised randomisation in clinical trials. Patients were allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio. An independent researcher collected data. |

|

Hasanein, 2013 |

Type of study: parallel group, randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Hospital, Saudi Arabia

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged 18 to 80 with BMI25-35 and ASA physical status I to III referred for ERCP

Exclusion criteria: Pregnant patients, morbidly obese patients, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, complicated airway, ASA physical classification IV–V, history of allergy or contraindications to the drugs used in the study, emergency need for ERCP, those whose informed consent could not be signed, and those with possible complex ERCP

N total at baseline: Total: 200 Intervention:100 Control: 100

Important prognostic factors2: Intervention/Control

Age (mean ± SD), years 57.67±13.3/56.93±11.9

Male, n (%) 49(49)/50(50)

BMI (mean ± SD) 29.6±3.53/28.9±4.42

Procedure’s duration (mean ± SD); min 31.61±17.65/27.88±14.38

ASA classification; n (%) I: 16/17 II: 61/62 III: 23/21

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention: A bolus dose of 10 ml normal saline followed by ketofol infusion (ketamine: propofol concentration 1:4) prepared in 50 ml syringe, by mixing 40 ml propofol 1% (10 mg/ml) with 2 ml ketamine (50 mg/ml) and 8 ml dextrose 5% (each ml contained 8 mg propofol and 2 mg ketamine) |

Describe control: a bolus of fentanyl 1.5 µg/kg i.v., the volume of which was made to 10 ml followed by 40 ml propofol 1%, was mixed with 10 ml dextrose 5%, so that each millilitre contained 8 mg of propofol. |

Length of follow-up: No follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data

|

Outcome measures and effect size

Apnea; RR (95% CI) 0.20 (0.04 to 0.89)

Desaturation; RR (95% CI) 0.07 (0.00 to 1.15)

Hypotension; RD (95%CI) -0.09 (-0.16 to -0.02)

Hypertension; RD (95%CI) 0.02 (-0.01 to 0.05)

Bradycardia; RD (95%CI) -0.08 (-0.20 to 0.04)

Tachycardia; RD (95%CI) 0.02 (95% CI -0.02 to 0.06)

Nausea and vomiting; RD (95%CI) 0.02 (95% CI -0.02 to 0.06)

Recovery time (min); MD (95% CI) 0.70 (-0.76 to 2.16)

Patient satisfaction; RR (95% CI) 1.01 (0.92 to 1.11) |

The authors conclude that Ketamine–propofol combination (1:4) provided better sedation quality than fentanyl/propofol combination, with less hemodynamic and respiratory depression and appears to be a safe and useful technique for sedating obese patients undergoing ERCP

RoB: Patients were randomised by the sedation practitioner using the online ALEA software program for centralised randomisation in clinical trials. Patients were allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio. An independent researcher collected data. |

|

Hwang, 2005 |

Type of study: parallel group, randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Hospital, south Korea

Funding and conflicts of interest: None declared |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged between 18 years and 70 with ASA physical status I and II undergoing elective fibreoptic bronchoscopy

Exclusion criteria: allergy to study medication, those felt to be unable to use the PCS system, and patients who had an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy.

N total at baseline: Total: 172 Intervention:138 Control: 138

Important prognostic factors2: Intervention/Control

Age (mean ± SD), years 58.3±1.3/57.4 12.7

Male, n (%) 90(65)/88(64)

Weight (mean ± SD), kg 60.2±11.1/60.6±12.1

Height (mean ± SD), cm 161.8±8.6/163.7±8.0

Time to start of the Procedure (mean ± SD), min 2.1±0.2/2.1±0.3

Duration of sedation (mean ± SD), min 14.4±6.8/14.2±6.5

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention: propofol 10 ml (8.3 mg/l), ketamine 1 ml (4.2 mg/l)

|

Describe control: propofol 10 ml (8.3 mg/l) and alfentanil 2 ml (83 mg/ml) |

Length of follow-up: No follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data

|

Outcome measures and effect size

Amnesia; RR (95% CI) 1.35 (1.15 to 1.57)

Patient satisfaction (VAS),; MD (95%CI) 0.20 (-0.51 to 0.91)

|

The authors conclude that although both techniques proved effective for sedation in patients undergoing fibreoptic bronchoscopy, ketamine is superior to alfentanil when used in combination with propofol because of the high patient satisfaction and amnesia

RoB: Patients were randomized to 2 groups via sealed envelope assignment. |

|

Khajavi, 2012 |

Type of study: parallel group, randomised controlled trial

Setting and country: Hospital, Iran

Funding and conflicts of interest: The study project was funded by research deputy of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

No conflict of interest |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged older than 18 with ASA physical status I and II scheduled for colonoscopy procedures.

Exclusion criteria: Recent history of colonoscopy, a previous colonic resection, severe heart failure (ejection fraction < 30%) and known history of hypersensitivity to midazolam, propofol, ketamine or fentanyl.

N total at baseline: Total: 60 Intervention:30 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2: Intervention/Control

Age (mean ± SD), years 55.9±15/51.6±21

Male, n (%) 16(53)/18(30)

Weight (mean ± SD), kg 59±17/56±14

Height (mean ± SD), cm 157 ± 8/155 ± 5

ASA a physical status, n(%) I 14 (47)/12 (40) II 9 (30)/12 (40) III 7 (23)/6 (20)

Duration of Procedure (mean ± SD), min 23.3 ± 7.7/21.8 ± 9.7

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention: IV dose of ketamine 0.5mg/ kg and propofol 0.7mg/kg. |

Describe control: IV dose of 10 μg/kg alfentanil and propofol 0.7mg/kg. |

Length of follow-up: No follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete outcome data

|

Outcome measures and effect size

Nausea and vomiting; RD (95% CI) 0.19 -0.02 to 0.41)

Psychological emergence; RD (95% CI) 0.06 (-0.01 to 0.13)

Recovery time (min); MD (95% CI) 5.30 (2.41 to 8.19)

Patient satisfaction; MD (95% CI) 2.10 (1.92 to 2.28) |