Niet-farmacologische technieken

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van niet-farmacologische (psychologische en fysieke) technieken voor PSA bij kinderen?

Deze uitgangsvraag bevat de volgende subvragen:

-

Wat is de rol van niet-farmacologische (psychologische) technieken voor PSA bij kinderen?

-

Wat is de rol van niet-farmacologische (fysieke) technieken voor PSA bij kinderen?

Aanbeveling

Zet niet-farmacologische technieken doelmatig en doelgericht in, op elk moment van het proces en passend bij de individuele voorkeuren, kenmerken en eerdere ervaringen van het kind.

Zorg bij PSA dat de kennis en vaardigheden aanwezig zijn om het fysieke, emotionele en psychische welzijn van het kind te waarborgen, zowel voor, tijdens als na afloop van een procedure, zoals beschreven in de Rights Based Standards. De hoofdbehandelaar en sedationist zijn verantwoordelijk voor de omgeving, interprofessionele afstemming en rolverdeling (zie hiervoor de generieke module over verantwoordelijkheden in de richtlijn PSA bij volwassenen).

Maak indien nodig gebruik van de expertise van de medisch pedagogisch zorgverlener (MPZ). Voor sommige kinderen geldt dat PSA alleen maar gepland kan worden wanneer de medisch pedagogisch zorgverlener beschikbaar is.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de conclusies uit de literatuursamenvatting voor de uitkomstmaat pijn lijkt de kwaliteit van het bewijs onvoldoende om conclusies te kunnen trekken over de effecten van het gebruik van psychologische en/of fysieke interventies. Dit geldt ook voor de uitkomstmaten angst en procedureel succes. De kwaliteit van het bewijs is voor alle uitkomsten zeer laag, dit is met name het gevolg van kleine studies, grote heterogeniteit in zowel de interventies, controle-interventies en de resultaten. Het ligt voor de hand dat gestandaardiseerde interventies mogelijk heterogene effecten hebben, afhankelijk van de context en van de voorkeuren van de patiënt. Daarnaast zijn de aantallen patiënten laag. Er zijn geen studies gevonden die de patiëntvoorkeuren of PROM’s als uitkomstmaat hebben gerapporteerd. In het algemeen kan de literatuursamenvatting daarom geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming omtrent de onderzochte interventies.

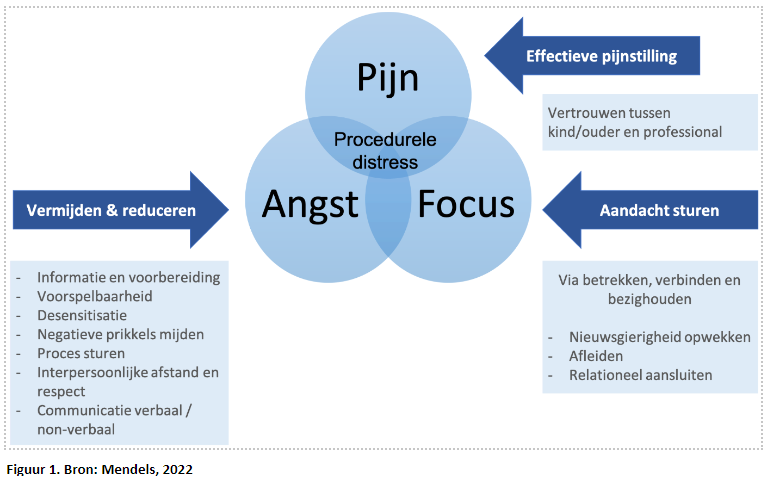

Het ondergaan van een medische procedure kan voor kinderen een angstige en stresserende aangelegenheid zijn. PSA kan uitkomst bieden, maar is op zichzelf geen garantie voor een comfortabele ervaring. De zogenaamde procedurele distress die door kinderen wordt ervaren, kan worden beschouwd als een samenspel tussen de angst voor de procedure, de pijn die erbij gepaard gaat en focus hierop (Baxter, 2013). Procedurele distress als multifactorieel fenomeen vraagt daarom ook om een multimodale aanpak.

De inzet van niet-farmacologische technieken bij PSA wordt om deze reden beschouwd als een essentiële voorwaarde om te komen tot een succesvolle, comfortabele ervaring voor het kind waarbij naast de fysieke veiligheid ook de psychologische veiligheid geborgd blijft.

De term “niet-farmacologie” is een parapluterm voor een zeer grote verscheidenheid aan technieken die ieder verschillende (en soms zelfs wisselende) onderliggende werkzame mechanismen/elementen kunnen bevatten. Het opblazen van een ballon kan bijvoorbeeld een fysieke (ontspannings-)respons teweegbrengen, maar ook werkzaam zijn als afleiding of het effect geven van een positieve verwachting. Met name het zelf kiezen voor een strategie kan zorgen voor een gevoel van controle en autonomie en daarmee leiden tot een afname van angst (Birnie, 2019; Koller, 2012). De niet-farmacologische strategieën die worden ingezet dienen dan ook passend te zijn bij het doel wat men wil bereiken. Grof gezegd kan onderscheid gemaakt worden tussen technieken die gericht zijn op angstreductie en technieken die de aandacht van het kind sturen en verleggen (zie figuur 1).

Naast de grote variatie in beschikbare technieken, bestaat er een minstens zo grote variatie aan kindfactoren waaronder variaties in ontwikkelingsniveau, psychopathologie, temperament, coping, individuele voorkeuren, mate van angst en eerdere ervaringen. Gemiddelde effecten uit literatuurstudies zijn hierdoor beperkt toepasbaar op het individu. De uitdaging en de sleutel ligt in het identificeren van de aanleg, voorgeschiedenis en voorkeuren van het kind. Het zorgvuldig kunnen triëren, inschatten en individualiseren van de best passende niet-farmacologische strategieën is dan ook een onmisbare niet te onderschatten professionele competentie (Koller, 2012). De medisch pedagogisch zorgverlener (MPZ) kan hier een belangrijke rol in vervullen. Evenals ouders die een belangrijke bron van informatie kunnen zijn. Hoe complexer het kind is, hoe meer relevant de informatie van ouders/verzorgers is om de juiste strategie te kunnen bepalen.

Zorgprofessionals die PSA uitvoeren, dienen te beschikken over een grote variatie aan niet-farmacologische technieken en in staat te zijn deze doelmatig toe te passen en individualiseren naar gelang de behoeften van het kind, en zo nodig aan te passen wanneer de situatie daarom lijkt te vragen.

Daarnaast is het effect van de niet-farmacologische technieken afhankelijk van het vermogen van de professional om een connectie te maken met het kind en ouders en een setting van vertrouwen te creëren. Binnen deze setting ontstaat co-creatie en komen de gezamenlijk gekozen niet-farmacologische strategieën optimaal tot hun recht. Het is zinvol om het plan van te voren zorgvuldig te doorlopen met ouder(s)/verzorgers en de betrokken zorgprofessionals.

Tot slot verdient de rol van de ouder/verzorger hier expliciet benoemd te worden. Ouders/verzorgers zijn immers expert over hun eigen kind en kunnen waardevolle ideeën hebben over welke niet-farmacologische strategieën effectief zouden kunnen zijn. Echter, met betrekking tot de aanwezigheid van ouders/verzorgers tijdens medische procedures is bekend dat de aanwezigheid op zichzelf niet leidt tot een aantoonbare vermindering van angst of verhoging van medewerking van het kind. Een angstige ouder/verzorger heeft daarentegen wel degelijk een negatief effect op de gemoedstoestand van het kind. Afwezigheid van ouders is echter niet gewenst. Het voorlichten en coachen van ouders/verzorgers om op een kalme ondersteunende manier aanwezig te zijn, het aanleren van voorbereidende en/of afleidende strategieën dient daarom mee te worden genomen in het plan van aanpak. (Bevan 1990, Manyande 2015).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het vermijden van pijn en angst bij kinderen dient evenzo belangrijk te zijn als de medische verrichting zelf. Kinderen hebben ook bij medisch handelen recht op de beste zorg. Zoals ‘Artikel 9’ beschrijft van het Handvest Kind & Zorg: Zieke kinderen worden beschermd tegen onnodige behandelingen en onderzoeken en maatregelen worden genomen om pijn, lichamelijk ongemak en emotionele spanningen te voorkomen dan wel te verlichten (art.3,12,17 VRK).

Voor het kind is het (op korte termijn) van belang dat de procedure zo comfortabel mogelijk verloopt, met zo min mogelijk angst, pijn en stress gepaard gaat en dat psychotrauma wordt voorkomen. Op lange termijn is het doel om het vertrouwen van het kind in de zorg(verleners) te behouden en daarmee zorgmijding en onderbehandeling te voorkomen.

Subgroepen die in het bijzonder kwetsbaar zijn en gebaat zijn bij goede ervaringen zijn langdurig of chronisch zieke kinderen, kinderen met psychopathologie en/of een ontwikkelingsachterstand of communicatieve beperking. Tegelijk vormt deze subgroep voor de professional een uitdaging omdat voorbereiding, afstemming met ouders/verzorgers en professionals onderling een vereiste is en niet alle niet-farmacologische technieken even effectief zullen zijn.

Het is van groot belang in het voorbereidende proces en tijdens interventies steeds bewust te zijn van samen beslissen met zowel kind als ouders/verzorgers volgens de geldende WGBO regels. Naast dat kinderen het recht hebben om samen met ouders en zorgprofessional te beslissen blijkt uit onderzoek dat het positieve effecten voor het kind heeft. Het Samen Beslissen heeft volgens Coyne en Harder (2011) voor kinderen als positief effect dat zij meer bereid zijn om mee te werken bij een behandeling, pijnlijke behandelingen geduldiger ondergaan, minder boosheid ervaren, beter om kunnen gaan met het begrijpen van hun ziekte en behandeling en beter herstellen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Niet-farmacologische technieken brengen op zichzelf weinig kosten met zich mee. Directe (personele) kosten zijn er in de vorm van tijd en aandacht tijdens, voorafgaand aan en na de interventie. Indirecte kosten zijn verbonden aan het opleiden en deskundig maken van personeel.

In de Rights Based Standards (Bray, 2021) wordt beschreven dat kinderen het recht hebben om verzorgd te worden door professionals die beschikken over de juiste kennis en vaardigheden om hun fysieke, emotionele en psychische welzijn te waarborgen, zowel voor, tijdens als na afloop van een procedure. Naast deze ethische en humane aspecten, zorgt het voorkomen van angst en psychotrauma voor een belangrijke kostenbesparing op de daarbij benodigde intensieve en soms langdurige psychologische behandelingen om deze gevolgen terug te dringen (met alle impact op het hele leven van het kind en gezin). Tevens zal een positieve ervaring voor het kind ook leiden tot behoud van vertrouwen in de zorg/zorgverlener. Dit kan worden beschouwd als een duurzame uitkomstmaat, omdat er aanwijzingen zijn dat dit leidt tot een betere arts-patiëntrelatie, betere behandeluitkomsten (bij een coöperatieve patiënt), kortere herstelperioden, minder mislukte procedures, minder vermijding van zorg of no-shows, en een goede medewerking bij volgende ingrepen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Met betrekking tot implementatie is het opleiden en competent maken van professionals om hen de juiste kennis, attitudes, vaardigheden en technieken aan te leren van belang. Dit vraagt tijd (leerproces) en brengt kosten met zich mee.

Bij voorkeur zijn zowel de zorgprofessionals die de PSA uitvoeren, als de zorgprofessionals die de procedure uitvoeren bekwaam en in staat om tussen meerdere scenario’s te schakelen.

Het waarborgen van continuïteit van deze zorg verdient tevens aandacht bij implementatie; in de avonden of weekenden, op verschillende afdelingen, bij afwezigheid van medisch pedagogische zorg (MPZ).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Vanuit humaan perspectief hebben kinderen recht op de beste zorg (internationaal verdrag rechten van het kind).

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Rondom medische procedures bij kinderen wordt veelvuldig gebruik gemaakt van niet-farmacologische technieken. Bekende voorbeelden hiervan zijn voorbereiden en informeren, afleiding door middel van fysiek of digitaal spel en het doelgericht verleggen van de focus door middel van suggestie, visuele technieken, focustaal en/of hypnotische technieken. Fysieke technieken (bijvoorbeeld vibratie al dan niet in combinatie met lokaal koelen) is intussen een veelgebruikte methode voor lokale pijnstilling. Ook het doelgericht inzetten van de ouders/verzorgers, het streven naar comfortabele posities en processen en het doseren van zintuigelijke prikkels kunnen worden beschouwd als niet-farmacologische onderdelen van een beleid gericht op comfort.

Hoewel voor sommige van deze technieken wetenschappelijk bewijs bestaat, is het onduidelijk hoe deze technieken het best in de praktijk kunnen worden toegepast.

Vast staat dat vele niet-farmacologische technieken inconsistent worden ingezet. Zo blijken sommige technieken (bijvoorbeeld toegepast door de medisch pedagogisch zorgverlener) alleen tijdens kantoortijden inzetbaar te zijn. Andere technieken zoals Virtual Reality, digitale projecties en focustaal worden tegenwoordig door velen omarmd, terwijl de wetenschappelijke onderbouwing voor gebruik op de kinderleeftijd nog beperkt is en ze niet op alle leeftijden en voor alle kinderen even effectief blijken. Niet-farmacologische technieken hebben een sterk wisselende effectiviteit afhankelijk van voor wie en door wie ze worden toegepast. Het zijn met andere woorden methodes waarvan het succes sterk contextueel wordt bepaald. Precies deze ideale context is tot op heden amper onderwerp van onderzoek geweest.

Het is onduidelijk hoe niet-farmacologische technieken het beste in de dagelijkse werkprocessen kunnen worden ingezet, hoe de individueel best passende methode kan worden gekozen en welke deskundigheden medische en verpleegkundige zorgprofessionals nodig hebben om ze in te bouwen in hun procedurele processen.

Ten slotte is het concept ‘niet-farmacologische techniek’ een betrekkelijk betekenisloos containerbegrip waaronder zeer uiteenlopende cognitieve, psychologische, communicatieve en fysieke methodes worden verstaan. Dit maakt het onmogelijk om over ‘niet-farmacologie’ een eenduidige literatuurstudie te verrichten, laat staan een zinnige aanbeveling te formuleren. Beter zou zijn om deze methodes te gaan ordenen volgens het therapeutisch doel dat ze nastreven.

Er worden landelijk veel verschillende niet-farmacologische middelen aangeboden op het gebied van PSA bij kinderen. Dit betreft psychologische en fysieke technieken of een combinatie daarvan. Onduidelijk is welke dit zijn en of het effect hiervan werkelijk een positieve uitkomst heeft voor de kinderen en hun omgeving. En welk uitvoeringsplan het beste past bij het toepassen van de techniek. Wanneer en op welk moment niet-farmacologische middelen wel of niet worden aangeboden is ook verschillend.

De niet-farmacologische technieken zijn volop in ontwikkeling en er worden veel nieuwe initiatieven genomen op dit gebied. Op dit moment is echter te weinig duidelijk welke niet-farmacologische technieken bewezen en van meerwaarde zijn bij de PSA van kinderen. Er is hier geen duidelijke landelijke richtlijn over.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Sub question 1

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of distraction on pain during a medical procedure when compared with standard care in pediatric patients.

Sources: Lambert, 2020; Birnie, 2018 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of distraction on distress when compared with standard care in pediatric patients.

Sources: Lambert, 2020; Birnie, 2018; Riddell, 2015; Manyande, 2015 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of distraction on procedural success when compared with standard care in pediatric patients.

Sources: Manyande, 2015 |

Sub question 2

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of vibratory stimulation on pain during needle related procedures when compared to standard care in pediatric patients.

Sources: Ueki, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of vibratory stimulation on anxiety when compared to standard care in pediatric patients.

Sources: Ueki, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

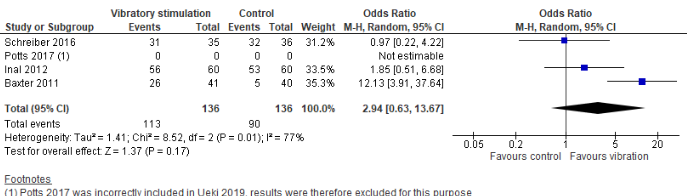

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of vibratory stimulation on procedural success when compared with standard care in pediatric patients.

Sources: Ueki, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of swaddling and holding in an upright position on observed pain when compared with standard care in neonatal patients.

Sources: Morrow, 2010 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Sub question 1

Preparation/information, distraction (e.g. guided imagery, breathing exercises, videos, video games, virtual reality), hypnosis, focused language, and relaxation techniques are psychological interventions used to assist in reducing pain, anxiety, distress, and increasing patient satisfaction during and around a potentially painful procedure. From a systematic literature search, four systematic reviews were selected based on full-text (Lambert 2020, Riddell 2015, Birnie 2018, Manyande 2015). These reviews included studies with participants aged 0 to 19 years.

Lambert et al (2020) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the effect of virtual reality (VR) distraction on pain, compared with no distraction or non-VR distraction during various painful procedures in children and adolescents aged 4 to 18 years. This review included seventeen randomised controlled trials (RCTs). This study reported self-reported pain, and child satisfaction with the VR intervention as outcomes. In general, no or small beneficial effects of VR interventions were found, and in some participants, nausea and motion sickness due to the intervention were reported. The evidence reported in this study is of low to very low quality, mostly due to a high risk of bias for not blinding participants, caregivers and observers to the allocation of the intervention, and serious imprecision or indirectness. The results from this review are presented in Table 2.

Riddell et al (2015) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to estimate the effects of various forms of patient distraction during a vaccine injection compared to “control” conditions on patient distress. Studies in infants aged 0 to 3 years were included in this review. The evidence was of very low quality due to no blinding with regard to the intervention, imprecision due to small samples, and indirectness. For one type of intervention (directed video), a beneficial effect was reported. No significant effects were reported for other interventions. The results from this review are summarised in Table 2.

Birnie et al (2018) performed a systematic review that included RCTs to estimate the effects of distraction, cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnosis on pain (self-reported and observer-reported) and distress during needle-related procedures in children and adolescents aged 2 to 19. Nine studies used cartoons or a movie as distraction method, eight used listening to music or a story, three used an interactive handheld computer or video games, three used distraction cards, two used virtual reality, two used playing with a toy, two used parent distraction, one used a medical clown, one used squeezing a ball, and five used a combination or selection of different distractors. In general, the study found beneficial effects of these interventions on pain and distress. The evidence was of very low or low quality, as studies had a high risk of bias due to lack of blinding and concealment of allocation, were inconsistent and imprecise. The results from this review are summarized in Table 2.

Manyande et al (2015) performed a systematic review of RCTs to estimate the effect of (video, video game, or two or one parent) distraction on anxiety and co-operation during induction of anesthesia in children and adolescents aged 0 to 18. The review found a beneficial effect of all forms of distraction on anxiety and co-operation during the procedure, compared to no video distraction, or presence of one or no parents. The evidence was of very low quality because of high risk of bias (selection bias and lack of blinding), and imprecision. The results from this review are summarized in Table 2.

Of note is the finding that parental presence in subgroup of anxious parents had a negative effect on child anxiety, while presence of calm parents had no effect.

Table 2 is presented in the tables section.

Conclusions

The review of Lambert et al (2020) concluded that due to the very low quality of the included studies, it was difficult to assess the real advantages and disadvantages of virtual reality distraction methods to reduce pain in children in various healthcare situations. Moreover, because of the large variety in study methods and reported outcome measures, it was not possible to pool the results on many outcomes.

The review of Riddell et al (2015) concluded that studies that investigated the effects of directed video, and directed and nondirected toy distraction were of low to very low quality. Therefore no definitive conclusions could be formulated on the benefits and disadvantages of these interventions on distress in children.

The review of Birnie et al (2018) concluded that although the quality of the evidence was low to very low, moderate to large effects ranging from SMD -0.56 (95% CI: -0.78 to -0.33) for the effect of distraction on self-reported pain to SMD -0.82 (95% CI: -1.45 to 0.18) for the effect of distraction on self-reported distress were found in favour of distraction.

The review of Manyande et al (2015) concluded that there is no evidence that the presence of one or more parents during the induction of anaesthesia is beneficial to decrease anxiety of the child.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias: intervention not blinded); conflicting results (inconsistency); indirectness; imprecision (broad confidence intervals), and publication bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure anxiety was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias: intervention not blinded); conflicting results (inconsistency); indirectness; imprecision (broad confidence intervals), and publication bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure procedural success was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias: intervention not blinded); conflicting results (inconsistency); indirectness; imprecision (low number of included patients), and publication bias.

Sub question 2

Different physical interventions are used to achieve procedural analgesia, e.g. cooling, vibration, or holding an infant in a certain position. From a systematic literature search, two studies were included: one systematic review (Ueki 2019), and one randomised controlled trial (Morrow, 2010). Both investigated the effects of physical interventions on pain, and Ueki also investigated the outcomes anxiety and success rate of the first venipuncture. Morrow et al included neonates, while Ueki et al included studies that included infants and children aged 15 days to 18 years.

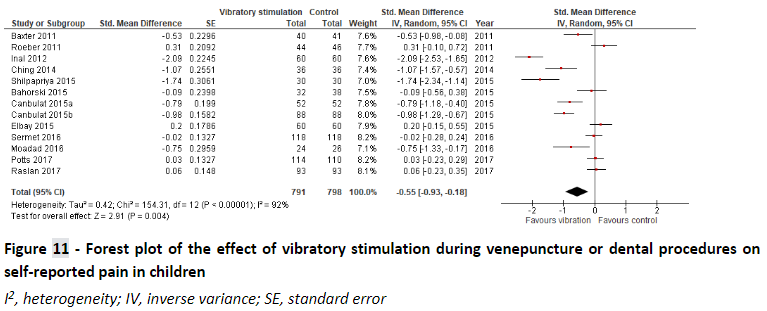

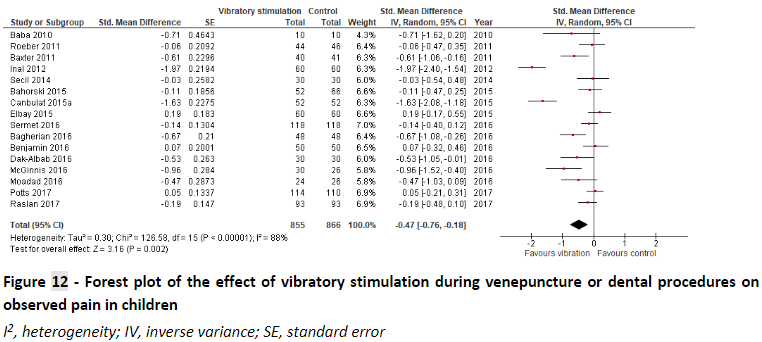

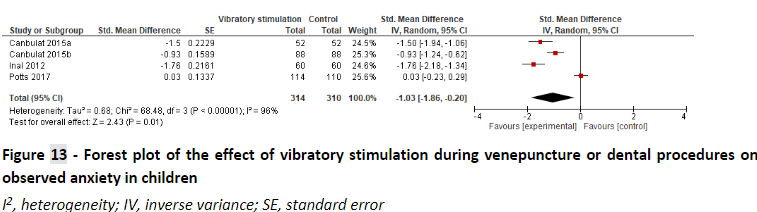

Ueki et al. (2019) performed a systematic review to analyze the effect of vibratory stimulation as a pain reducing measurement for needle-related procedures (NRP) on pediatric patients. They searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Igaku Chuo Zasshi for published trials and searched Clinical-Trials.gov, EU Clinical Trials Register, UMIN Clinical Trials Registry and OpenGrey for unpublished studies. Included were studies that included pediatric participants up to 18 years old with any condition who were undergoing an NRP. NPR’s existed of puncture, injection, and IV catheter insertion. They did not have any exclusion criteria. They included 21 RCT studies for a total of 1717 patients of which 8 studies were cross-over studies. It should be noted that on several occasions, results presented in this review were incorrectly adopted from the underlying clinical trials. Therefore in this summary, the meta-analyses were repeated using results that were retrieved from the original studies as much as possible.

Morrow et al. (2010) executed a RCT study to examine the pain-reducing effect of swaddling and holding the newborn pediatric patient in an upright position during heel-lance procedures compared to the standard care position. They included neonates in a tertiary hospital who would undergo a standard total serum bilirubin (TSB) procedure. Excluded from the study were neonates admitted to the NICU, diagnosed with hyperbilirubinemia and other medical complications, and infants delivered by diabetic mothers. They included 42 patients in total; 22 in the intervention group and 20 in the control group. Group assignment was randomized on the basis of the last digit of the infants patient number.

Results

Ueki et al. (2019) performed a meta-analysis to determine the effect of vibratory stimulation on self-rated pain score (SRPS), observer-rated pain score (ORPS), observer-rated anxiety (ORA), and success rate of first venipuncture (SRFV). Pooled effects are shown below:

None of the trials was blinded, as it could be observed whether a device was used or not. A sub-analysis using a turned on device as intervention group and turned off device as control group gave the following results:

Table 1 – Pooled effect measures of a vibrating and/or cooling device to prevent pain and discomfort in children undergoing a needle-related procedure

|

Outcome |

Number of studies included |

Pooled SMD (RE) |

CI 95% |

I2 |

p-value |

|

SRPS |

5 |

-0.07 |

-0.43 to 0.28 |

83.2% |

0.02 |

|

ORPS |

5 |

-0.16 |

-0.40 to 0.07 |

59% |

0.17 |

CI, confidence interval; I2, heterogeneity; ORPS, observer-rated pain score; RE, random-effects; SMD, standardized mean difference; SRPS, self-reported pain score

There is no significant evidence for a relevant effect of vibratory stimulation as a pain-reducing intervention.

Morrow et al. (2010) found that swaddling a neonate and holding them in an upright position during a heel-lance procedure gave a mean Neonatal Inventory Pain Scale (NIPS) score of 1.3 (SD 0.9), while the control group had a mean score of 2.7 (SD 1.3). The performed t-test (-4.48) showed this difference was statistically significant (P<0.001). While the study’s results are in favor of this intervention, the duality of the intervention as well as the small sample size reduces their claim of clinical significance. It should be noted that due to the position the infant is held in during the intervention in the intervention position, arm movement could be obscured from observation. Arm movement is part of the NIPS score, the results are likely biased in the direction of a beneficial effect of the intervention.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure self-reported pain was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias: intervention not blinded); conflicting results (inconsistency), imprecision (confidence interval crossed minimal clinically important difference), and publication bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure observed pain was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias: intervention not blinded); conflicting results (inconsistency); indirectness; imprecision (confidence interval crossed minimal clinically important difference), and publication bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure observed anxiety was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias: intervention not blinded); conflicting results (inconsistency); indirectness; imprecision (low number of included patients), and publication bias.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure procedural success was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations (risk of bias: intervention not blinded); conflicting results (inconsistency); indirectness; imprecision (confidence interval crossed null), and publication bias.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

-

Wat zijn de (on)gunstige effecten van niet-farmacologische psychologische interventies tijdens of voorafgaand aan een procedure bij kinderen die een pijnlijke procedure (zullen) ondergaan?

-

Wat zijn de (on)gunstige effecten van niet-farmacologische fysieke interventies tijdens of voorafgaand aan een procedure bij kinderen die een procedure (zullen) ondergaan?

| P: | Kinderen 0-18 jaar die een procedure ondergaan |

| I: | Psychologische interventies |

| C: | Usual care, placebo |

| O: | Efficacy, Procedural success, Comfort measured by a scale /Patient satisfaction/PROM |

PICO 2

| P: | Kinderen 0-18 jaar die een procedure ondergaan |

| I: | Fysieke interventies |

| C: | Usual care, placebo |

| O: | Efficacy, Procedural success, Comfort measured by a scale /Patient satisfaction/PROM |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered comfort measured by a scale (pain/anxiety), efficacy, and procedural success as crucial outcome measures for decision making, and patient satisfaction/PROM as an important outcome measure.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Referenties

- Bevan JC, Johnston C, Haig MJ, Tousignant G, Lucy S, Kirnon V, Assimes IK, Carranza R. Preoperative parental anxiety predicts behavioural and emotional responses to induction of anaesthesia in children. Can J Anaesth. 1990 Mar;37(2):177-82. doi: 10.1007/BF03005466. PMID: 2311148.

- Birnie KA, Noel M, Chambers CT, Uman LS, Parker JA. Psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Oct 4;10(10):CD005179. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005179.pub4. PMID: 30284240; PMCID: PMC6517234.

- Getting It Right First Time and Every Time; Re-Thinking Children's Rights when They Have a Clinical Procedure. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021 Nov-Dec;61:A10-A12. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.11.017. PMID: 34872648.

- Koller D, Goldman RD. Distraction techniques for children undergoing procedures: a critical review of pediatric research. J Pediatr Nurs. 2012 Dec;27(6):652-81. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.08.001. Epub 2011 Oct 13. PMID: 21925588.

- Lambert V, Boylan P, Boran L, Hicks P, Kirubakaran R, Devane D, Matthews A. Virtual reality distraction for acute pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Oct 22;10(10):CD010686. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010686.pub2. PMID: 33089901; PMCID: PMC8094164.

- Manyande A, Cyna AM, Yip P, Chooi C, Middleton P. Non-pharmacological interventions for assisting the induction of anaesthesia in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jul 14;2015(7):CD006447. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006447.pub3. PMID: 26171895; PMCID: PMC8935979.

- Mendels W, Zirar-Vroegindeweij A, Waagenaar G, Versteegh J, Leroy P. Kindgerichte zorg bij medische verrichtingen. Huisarts en wetenschap. 2022 (9)

- Morrow C, Hidinger A, Wilkinson-Faulk D. Reducing neonatal pain during routine heel lance procedures. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2010 Nov-Dec;35(6):346-54; quiz 354-6. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3181f4fc53. PMID: 20926970.

- Pillai Riddell R, Taddio A, McMurtry CM, Chambers C, Shah V, Noel M; HELPinKIDS Team. Psychological Interventions for Vaccine Injections in Young Children 0 to 3 Years: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin J Pain. 2015 Oct;31(10 Suppl):S64-71. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000279. PMID: 26201014; PMCID: PMC4900410.

- Ueki S, Yamagami Y, Makimoto K. Effectiveness of vibratory stimulation on needle-related procedural pain in children: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2019 Jul;17(7):1428-1463. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003890. PMID: 31021972.

Evidence tabellen

Psychological interventions

Table 2 – Summary of studies included in the systematic reviews of

| Review | ID | author | year | N | mean age | sex | intervention | control | follow-up | incomplete outcome | outcome 1 | effect measure 1 (95ci) | outcome 2 | effect measure 2 (95ci) | outcome 3 | effect measure 3 (95ci) | outcome 4 | effect measure 4 (95ci) | Comment |

| Birnie 2018 | A | Aydin | 2017 | 200 | 9.01 ± 2.35 y | 116m 84f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FACES) | -0.43 [95% CI: -0.75 , -0.11] | Observer-report pain (FACES) | -0.33 [95% CI: -0.56 , -0.10] | Observer-report distress (CFS) | -0.22 [95% CI: -0.45 , 0.00] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | B | Balan | 2009 | 100 | 7.96 ± 2.18 y | 55m 45f | Music distraction | Analgesic cream | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | -2.52 [95% CI: -3.05 , -1.99] | Observer-report pain (VAS) | -2.49 [95% CI: -3.02 , -1.96] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | C | Bellieni | 2006 | 69 | 7 to 12y | 33m 36f | Mother or video distraction | No distraction | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Oucher Pain Rating Scale) | -0.50 [95% CI: -1.01 , 0.00] | Parent-report pain (Oucher Pain Rating Scale) | -0.21 [95% CI: -0.71 , 0.29] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | D | Beran | 2013 | 57 | 6.87 ± 1.34 y | 30m 27f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | After procedure | Observer-report pain (FPS-R) | Self-reported pain | -0.50 [95% CI: -1.03 , 0.03] | Observer-reported pain | -0.57 [95% CI: -0.88 , -0.27] | Behavioral measures- Distress | -0.87 [95% CI: -1.42 , -0.33] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | D | Beran | 2013 | 57 | 6.87 ± 1.34 y | 30m 27f | Robot distraction | Toy distraction | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -0.64 [95% CI: -1.03 , -0.25] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | E | Bisignano | 2006 | 30 | 11.4y | 15m 15f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (Children’s Pain Self-Report) | After procedure | Self-report distress (Fear SR) | Self-reported pain | 0.40 [95% CI: -0.32 , 1.13] | Self-reported distress | -0.46 [95% CI: -1.19 , 0.27] | Observer-reported distress | 0.54 [95% CI: -0.21 , 1.29] | Behavioral measures- Distress | 0.39 [95% CI: -0.35 , 1.13] | |

| Birnie 2018 | E | Bisignano | 2006 | 30 | 11.4y | 15m 15f | Explanation | Standard care (may also include distraction) | Missing data, no reason addressed | Self-report pain (Children’s Pain Self-Report) | -0.02 [95% CI: -0.41 , 0.36] | ||||||||

| Birnie 2018 | F | Blount | 1992 | 60 | 5y ± 10m | 32m 28f | CBT-combined | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Observer-report distress (VAS) | -1.03 [95% CI: -1.57 , -0.49] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | G | Caprilli | 2007 | 108 | 6.67y ± 3.19 (intervention); 7.07y ± 3.47 (control) | 52m 56f | Music distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -0.49 [95% CI: -0.87 , -0.11] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | H | Cassidy | 2002 | 62 | 5y | 28m 34f | Audiovisual distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Missing data, no reason addressed | Self-report pain (FPS) | -0.40 [95% CI: -0.92 , 0.12] | Observed pain (CHEOPS) | 0.16 [95% CI: -0.38 , 0.71] | Parent-reported anxiety (VAS) | ||||

| Birnie 2018 | I | Cavender | 2004 | 43 | 7.88 ± 1.74 y | 19m 24f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | After procedure | Self-reported fear (GFS) | Self-reported pain | -0.25 [95% CI: -0.85 , 0.35] | Self-reported distress | -0.32 [95% CI: -0.92 , 0.29] | Observer-reported distress | -0.70 [95% CI: -1.32 , -0.08] | Behavioral measures- Distress | -0.32 [95% CI: -0.92 , 0.29] | |

| Birnie 2018 | I | Cavender | 2004 | 43 | 7.88 ± 1.74 y | 19m 24f | Parental positioning and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | 0.31 [95% CI: -0.28 , 0.91] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | J | Chen | 1999 | 50 | 7.3 ± 3.7 y | 33m 17f | CBT-combined | Placebo therapy+support+encouragement | After procedure | Missing non-differential | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | not reported | Observer-report pain (VAS) | not reported | Self-report distress (VAS) | not reported | Observer-report distress (VAS) | not reported | |

| Birnie 2018 | K | Cohen | 2015 | 90 | 4.8 years ± 9.7 months | 44m 46f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | After procedure | Observer-report pain (VAS) | Self-reported pain | 1.12 [95% CI: 0.57 , 1.67] | Observer-reported pain | -0.31 [95% CI: -0.67 , 0.05] | Observed distress | -0.23 [95% CI: -0.53 , 0.06] | Behavioral measures- Distress | -0.06 [95% CI: -0.35 , 0.24] | |

| Birnie 2018 | K | Cohen | 2015 | 90 | 4.8 years ± 9.7 months | 44m 46f | Distraction | parent education or standard care | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | 0.17 [95% CI: -0.34 , 0.67] | Observer-report pain (VAS) | -0.31 [95% CI: -0.67 , 0.05] | Observed distress | -0.77 [95% CI: -1.16 , -0.38] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | L | Crevatin | 2016 | 200 | 4 to 13y | 98m 102f | Computer distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R or Numerical rating scale) | 0.07 [95% CI: -0.21 , 0.34] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | M | Ebrahimpour | 2015 | 30 | 3 to 12y | 15m 15f | Explanation | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Observer distress (OSBD-R) | -0.45 [95% CI: -1.18 , 0.27] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | N | Eland | 1981 | 40 | 4.9 to 5.9y | 20m 20f | Suggestion | No explanation | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (color scale) | -0.65 [95% CI: -1.56 , 0.25] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | O | Fanurik | 2000 | 160 | 2 to 16y | 80m 80f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Missing non-differential | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | -0.17 [95% CI: -0.55 , 0.20] | Self-report anxiety (VAS) | 0.02 [95% CI: -0.35 , 0.38] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | P | Fowler-Kerry | 1987 | 200 | 5.5y | 100m 100f | CBT-combined | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (4-point VAS) | 0.40 [95% CI: -0.32 , 1.13] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | P | Fowler-Kerry | 1987 | 200 | 5.5y | 100m 100f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (4-point VAS) | After procedure | Self-reported pain | -0.64 [95% CI: -1.03 , -0.25] | ||||||||

| Birnie 2018 | P | Fowler-Kerry | 1987 | 200 | 5.5y | 100m 100f | Suggestion and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (4-point VAS) | -0.17 [95% CI: -0.55 , 0.21] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | Q | Gold | 2006 | 20 | 10.2y | 12m 8f | VR distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -0.13 [95% CI: -1.01 , 0.75] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | R | Gonzalez | 1993 | 28 | 3 to 7y | 21m 21f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Oucher Pain Rating Scale) | -0.27 [95% CI: -1.02 , 0.47] | Observer distress (Modified Frankl Behaviour Rating Scale) | -0.70 [95% CI: -1.47 , 0.06] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | S | Goodenough | 1997 | 117 | 3.5 to 17.7y | 73m 44f | Suggestion | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Incomplete data addressed | Self-report pain (FPS) | 0.05 [95% CI: -0.39 , 0.50] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | T | Gupta | 2006 | 75 | 6 to 12y | 44m 31f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | -1.30 [95% CI: -1.92 , -0.69] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | T | Gupta | 2006 | 75 | 6 to 12y | 44m 31f | Breathing technique | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | -2.07 [95% CI: -2.77 , -1.38] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | U | Harrison | 1991 | 100 | 8.4y | 51m 49f | Explanation | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | not reported | Observer-report pain (VAS-score) | not reported | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | U | Harrison | 1991 | 100 | 8.4y | 51m 49f | Preparation and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | -0.70 [95% CI: -1.11 , -0.30] | Observer-report pain (VAS-score) | -0.77 [95% CI: -1.18 , -0.37] | Observer-report distress (VAS-score) | ||||

| Birnie 2018 | V | Huet | 2011 | 29 | 5 to 12y | 16m 13f | Hypnosis | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Missing non-differential | Observer-report pain (MOPS) | -1.01 [95% CI: -1.79 , -0.23] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | W | Inal | 2012 | 123 | 9.36 ± 1.96y | 62m 61f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -1.44 [95% CI: -1.84 , -1.04] | Observer-report pain (FPS-R) | -1.35 [95% CI: -1.63 , -1.07] | Observer-report distress (CAPS) | -1.97 [95% CI: -2.28 , -1.67] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | X | Jeffs | 2007 | 27 | 14.06 ± 2.31 y | 17m 15f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (APPT) | 0.30 [95% CI: -0.53 , 1.13] | numbers don't add up | ||||||

| Birnie 2018 | Y | Kamath | 2013 | 160 | 4 to 10y | 85m 75f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | After procedure | Observer-report pain (TPPPS) | Self-reported pain | -0.02 [95% CI: -0.41 , 0.36] | Observer-reported pain | -1.52 [95% CI: -2.12 , -0.92] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | Y | Kamath | 2013 | 160 | 4 to 10y | 85m 75f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -2.21 [95% CI: -3.37 , -1.05] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | Z | Katz | 1987 | 36 | 8.3 ± 1.68 y | 24m 12f | Hypnosis | Distraction | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | 0.09 [95% CI: -0.57 , 0.74] | Self-report anxiety (VAS) | -0.24 [95% CI: -0.89 , 0.42] | Observer report distress | -0.20 [95% CI: -0.86 , 0.45] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AA | Kleiber | 2001 | 44 | 4 to 7y | 11m 33f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (Oucher Pain Rating Scale) | After procedure | Observer distress (PPQ-R) | Self-reported pain | 0.31 [95% CI: -0.28 , 0.91] | Observer-reported distress | 0.22 [95% CI: -0.38 , 0.81] | Behavioral measures- Distress | -0.11 [95% CI: -0.70 , 0.48] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AA | Kleiber | 2001 | 44 | 4 to 7y | 11m 33f | Parent coaching and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Incomplete data addressed | Self-report pain (Oucher Pain Rating Scale) | 0.09 [95% CI: -0.08 , 0.27] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AB | Kristjansdottir | 2010 | 118 | 14 ± 0.18y | 63m 55f | Music distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | -0.04 [95% CI: -0.43 , 0.34] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AC | Kuttner | 1987 | 25 | 3 to 6y | not reported | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Observer-report distress (5-point scale) | 0.89 [95% CI: -0.15 , 1.93] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AD | Liossi | 1999 | 30 | 8 ± 2.5 y | 17m 13f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | After procedure | Self-report distress (Wong and Baker Scale) | Self-reported pain | -2.21 [95% CI: -3.37 , -1.05] | Self-reported distress | -1.24 [95% CI: -2.22 , -0.27] | Behavioral measures- Distress | -1.08 [95% CI: -2.03 , -0.12] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AD | Liossi | 1999 | 30 | 8 ± 2.5 y | 17m 13f | Hypnosis | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -2.65 [95% CI: -3.92 , -1.39] | Self-report distress (Wong and Baker Scale) | -4.12 [95% CI: -5.79 , -2.45] | Observer report distress | -1.74 [95% CI: -2.80 , -0.68] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AE | Liossi | 2003 | 60 | 8.73 ± 2.86 y | not reported | Hypnosis | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -2.07 [95% CI: -2.73 , -1.41] | Self-report distress (Wong and Baker Scale) | -2.43 [95% CI: -3.13 , -1.73] | Observer report distress | -1.40 [95% CI: -2.00 , -0.81] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AF | Liossi | 2006 | 45 | 8.84 ± 2.86 y | 23m 22f | Hypnosis | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -1.46 [95% CI: -2.28 , -0.64] | Self-report distress (Wong and Baker Scale) | -2.45 [95% CI: -3.43 , -1.47] | Observer report distress | -1.92 [95% CI: -2.80 , -1.03] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AG | Liossi | 2009 | 30 | 8.5 ± 2.21 y | 14m 16f | Hypnosis | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS scale) | -1.18 [95% CI: -1.97 , -0.40] | Self-report distress (VAS scale) | -3.89 [95% CI: -5.16 , -2.61] | Observer report distress | -1.56 [95% CI: -2.39 , -0.73] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AH | Luthy | 2013 | 54 | 5.2 ± 3.4 y | 32m 36f | Video distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Observer report pain (Wong and Baker FACES) | 0.14 [95% CI: -0.42 , 0.71] | Observer report distress (0-5 scale) | 0.00 [95% CI: -0.56 , 0.56] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AI | McCarthy | 2010 | 542 | 6.95 ± 1.90 y | 280m 262f | CBT-combined | Observer report distress (single item question) | After procedure | Observer report distress (OSBD-R) | Self-reported pain | 0.09 [95% CI: -0.08 , 0.27] | Observer-reported distress | -0.06 [95% CI: -0.23 , 0.10] | % change in salivary cortisol | -3.14 [95% CI: -3.52 , -2.76] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AI | McCarthy | 2010 | 542 | 6.95 ± 1.90 y | 280m 262f | Parent coaching and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Observer report distress (single item question) | -0.20 [95% CI: -0.84 , 0.45] | Observer report distress (OSBD-R) | -0.02 [95% CI: -0.19 , 0.15] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AJ | Meiri | 2016 | 60 | 5.3 ± 2.5 y | 53m 47f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Self-report pain (10 FACES) | -0.32 [95% CI: -0.81 , 0.16] | Observer-report pain (VAS-score) | -0.84 [95% CI: -1.19 , -0.48] | Observed anxiety (VAS-scale) | -1.37 [95% CI: -1.91 , -0.83] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AK | Miguez-Navarro | 2016 | 140 | 3 to 11y | 81m 59f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -1.19 [95% CI: -1.55 , -0.83] | Self-report distress (Groninger Distress Scale) | -1.27 [95% CI: -1.63 , -0.90] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AL | Miller | 2016 | 98 | 6.73 ± 2.71 y | 48m 50f | CBT-combined | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-reported pain | -0.30 [95% CI: -0.94 , 0.33] | Observer-report pain (VAS-score) | -0.98 [95% CI: -1.65 , -0.31] | Observer-report pain (FLACC) | 0.23 [95% CI: -0.40 , 0.86] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AL | Miller | 2016 | 98 | 6.73 ± 2.71 y | 48m 50f | Preparation and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -0.02 [95% CI: -0.65 , 0.61] | Observer-report pain (VAS-score) | -0.83 [95% CI: -1.38 , -0.27] | Observer-report pain (FLACC) | -0.87 [95% CI: -1.43 , -0.31] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AM | Minute | 2012 | 97 | 4 to 10y | 49m 48f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | 0.06 [95% CI: -0.34 , 0.45] | Observer-report pain (FLACC) | -0.24 [95% CI: -0.64 , 0.16] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AN | Mutlu | 2015 | 88 | 9 to 12y | 48m 40f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Missing non-differential | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | ||||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AN | Mutlu | 2015 | 88 | 9 to 12y | 48m 40f | Breathing technique | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Missing non-differential | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -1.56 [95% CI: -2.04 , -1.08] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AO | Nguyen | 2010 | 40 | 7 to 12y | 25m 15f | Music distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (NRS 0-100 scale) | -1.46 [95% CI: -2.16 , -0.75] | Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | -1.44 [95% CI: -2.14 , -0.73] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AP | Nilsson | 2015 | 37 | 11 to 12y | 0m 37f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (color scale) | After procedure | Self-report distress (0-10) | Self-reported pain | -0.20 [95% CI: -0.84 , 0.45] | Self-reported distress | 0.23 [95% CI: -0.43 , 0.89] | Cortisol | -0.17 [95% CI: -0.83 , 0.49] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AP | Nilsson | 2015 | 37 | 11 to 12y | 0m 37f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (color scale) | -2.20 [95% CI: -3.03 , -1.36] | Self-report distress (0-10) | -0.38 [95% CI: -0.92 , 0.16] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AQ | Noguchi | 2006 | 62 | 4.55 ± 0.65 y | 37m 25f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -0.07 [95% CI: -0.60 , 0.46] | Observer distress (OSBD-R) | -0.21 [95% CI: -0.75 , 0.32] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AR | Oliveira | 2017 | 40 | 8.72 ± 1.80 y | 16m 24f | Audiovisual distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS scale) | -1.98 [95% CI: -2.52 , -1.44] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AS | Pourmovahed | 2013 | 100 | 9.45 ± 2.80 y | 58m 42f | Breathing technique | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Incomplete data addressed | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -0.54 [95% CI: -0.94 , -0.14] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AT | Press | 2003 | 94 | 6 to 16y | 57m 37f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS scale) | -0.40 [95% CI: -0.81 , 0.01] | Observer-report pain (VAS scale) | 0.07 [95% CI: -0.33 , 0.48] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AU | Ramírez-Carrasco | 2017 | 40 | 90 ± 17.15 m | 16m 24f | Hypnosis | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Observer-report pain (FLACC) | 0.20 [95% CI: -0.42 , 0.83] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AV | Rimon | 2016 | 53 | 2 to 15y | 21m 32f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | After procedure | Self-report pain (VAS scale) | Self-reported pain | -2.20 [95% CI: -3.03 , -1.36] | Cortisol | -0.13 [95% CI: -0.78 , 0.53] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AV | Rimon | 2016 | 53 | 2 to 15y | 21m 32f | Medical clown | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Incomplete data addressed | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -0.34 [95% CI: -0.62 , -0.07] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AW | Sahiner | 2016 | 120 | 9.1 ± 1.6 y | 63m 57f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -0.42 [95% CI: -0.86 , 0.02] | Observer-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -0.29 [95% CI: -0.60 , 0.03] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AW | Sahiner | 2016 | 120 | 9.1 ± 1.6 y | 63m 57f | Breathing technique | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -0.07 [95% CI: -0.58 , 0.44] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AX | Sander Wint | 2002 | 30 | 10 to 19y | 16m 14f | VR distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS scale) | -0.29 [95% CI: -1.02 , 0.43] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | AY | Sinha | 2006 | 240 | 6 to 18y | 120m 120f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -0.16 [95% CI: -0.42 , 0.09] | Self-report anxiety (STAIC) | -0.70 [95% CI: -1.06 , -0.35] | Observer report anxiety (VAS) | -0.36 [95% CI: -0.62 , -0.11] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | AZ | Tak | 2006 | 40 | 3 to 12y | 25m 15f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Self-report pain (Oucher Pain Rating Scale) | 0.45 [95% CI: -0.17 , 1.08] | Groningen Distress Scale (GDS) | -0.16 [95% CI: -0.78 , 0.46] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | AZ | Tak | 2006 | 40 | 3 to 12y | 25m 15f | Preparation and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Self-report pain (Oucher Pain Rating Scale) | 0.30 [95% CI: -0.24 , 0.84] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | BA | Tyc | 1997 | 55 | 6.3 - 18.6 y | 28m 27f | CBT-combined | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-reported distress | -0.15 [95% CI: -0.67 , 0.38] | Observer-report distress (VAS scale) | -0.39 [95% CI: -0.92 , 0.14] | Behavioral measures- Distress | -0.45 [95% CI: -0.98 , 0.09] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | BB | Vessey | 1994 | 100 | 7y 4m ± 3.3m | 62m 38f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | -0.61 [95% CI: -1.02 , -0.21] | Observed pain (CHEOPS) | -0.39 [95% CI: -0.79 , 0.00] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | BC | Vosoghi | 2010 | 72 | 3 to 6y | 37m 35f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Self-report pain (Oucher Pain Rating Scale) | -1.99 [95% CI: -2.55 , -1.42] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | BD | Wang | 2008 | 200 | 8 to 9 y | 98m 102f | CBT-combined | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS scale) | 1.12 [95% CI: 0.57 , 1.67] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | BD | Wang | 2008 | 200 | 8 to 9 y | 98m 102f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (VAS scale) | After procedure | Self-reported pain | -0.34 [95% CI: -0.62 , -0.07] | ||||||||

| Birnie 2018 | BD | Wang | 2008 | 200 | 8 to 9 y | 98m 102f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS scale) | -0.28 [95% CI: -0.56 , 0.00] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | BE | Windich-Biermeier | 2007 | 50 | 10.5 ± 3.8 y | 27m 23f | CBT-combined | Self-report pain (CAS) | After procedure | Self-reported fear (GFS) | Self-reported pain | -0.33 [95% CI: -0.89 , 0.23] | Self-reported distress | -0.18 [95% CI: -0.74 , 0.38] | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | BE | Windich-Biermeier | 2007 | 50 | 10.5 ± 3.8 y | 27m 23f | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (CAS) | -0.33 [95% CI: -0.89 , 0.23] | |||||||

| Birnie 2018 | BF | Yinger | 2016 | 58 | 56.6 ± 6.7 m | 27m 31f | CBT-combined | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Missing non-differential | Observer-report pain (UCLA Pain Assessment tool) | -0.49 [95% CI: -1.03 , 0.04] | Observer-report distress (7-point scale) | 1.00 [95% CI: 0.45 , 1.55] | Behavioral measures- Distress | -0.88 [95% CI: -1.43 , -0.33] | |||

| Birnie 2018 | BG | Zieger | 2013 | 120 | 6 to 12y | 60m 60f | Explanation | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | not reported | Observed pain (FLACC) | not reported | |||||

| Birnie 2018 | BG | Zieger | 2013 | 120 | 6 to 12y | 60m 60f | Preparation and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (FPS-R) | -0.18 [95% CI: -0.54 , 0.18] | Observed pain (FLACC) | 0.07 [95% CI: -0.29 , 0.43] | |||||

| Lambert 2020 | A | Atzori | 2018 | 15 | 7 to 17y | 10m 5f | VR (immersive) distraction | No distraction | After procedure | 2 withdrew | Pain (VAS-score) | MD -1.60, 95% CI -3.24 to 0.04 | Nausea | Not reported | |||||

| Lambert 2020 | C | Chan | 2019 | 129 | 4 to 11y | 74m 55f | VR (immersive) distraction | Non-VR distraction | After procedure | Missing <10% | Self-report pain | MD -1.39; 95% CI, -2.68 to -0.11 | Caregiver's reported distress | Number of needle attempts | |||||

| Lambert 2020 | B | Chan | 2019 | 123 | 4 to 11y | 67m 56f | VR (immersive) distraction | Non-VR distraction | After procedure | Missing <10% | Self-report pain | MD -1.78; 95% CI, -3.24 to -0.32 | Caregiver's reported distress | Number of needle attempts | |||||

| Lambert 2020 | D | Chen | 2019 | 136 | 7 to 12y | 77m 59f | VR (immersive) distraction | No distraction | Five minutes post procedure | Missing <10% | Self-report pain | MD -1.00, 95% CI -1.90 to -0.10 | Observed pain | MD -1.03, 95% CI -1.88 to -0.18 | Self-reported fear | MD -0.46, 95% CI -0.90 to -0.02 | |||

| Lambert 2020 | E | Das | 2005 | 9 | 5 to 16y | 6m 3f | VR (immersive) distraction | No distraction | After procedure | Missing >10% | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | Mean 4.1, SD 2.9 | Observed anxiety | Not reported | |||||

| Lambert 2020 | F | Dumoulin | 2019 | 59 | 8 to 17y | 38m 21f | VR (immersive) distraction | Non-VR distraction | 15 minutes after procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | MD -13.68, 95% CI -29.64 to 2.28 | Satisfaction questionnaire | 0.00, 95% CI -11.19 to 11.19) | Nausea (side effects) | not significant | |||

| Lambert 2020 | G | Gerceker | 2018 | 121 | 7 to 12y | 61m 60f | VR (immersive) distraction | 1. Non-VR distraction 2. no distraction | 5 minutes after procedure | Missing 21% | Self-report pain (Faces Pain Rating Scale) | MD -0.50 (95% CI -0.59 to -0.41) | Observed pain (Faces Pain Rating Scale) | MD -0.50 (95% CI -0.59 to -0.41) | |||||

| Lambert 2020 | H | Gold | 2006 | 20 | 8 to 12y | 12m 8f | VR (immersive) distraction | No distraction | following IV placement | No missing data | Self-report pain (Faces Pain Rating Scale) | MD -0.60 (95% CI -2.47 to 1.27) | Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index | Not reported | Satisfaction (with pain management) | not reported | |||

| Lambert 2020 | I | Hoffman | 2019 | 48 | 6 to 17y | 34m 14f | VR (immersive) distraction | No distraction | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (GRS) | MD -3.42 (95% CI -4.47 to -2.37) | Satisfaction questionnaire | Not reported | Nausea (side effects) | less than one on 10 point scale | |||

| Lambert 2020 | J | Hua | 2015 | 65 | 4 to 16y | 31m 34f | VR (immersive) distraction | Non-VR distraction | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Faces Pain Rating Scale) | MD -1.77 (95% CI -2.74 to -0.80) | Observed pain (VAS) | MD -1.90 (95% CI -3.23 to -0.57) | Duration procedure | not reported | |||

| Lambert 2020 | K | Jeffs | 2014 | 28 | 10 to 17y | 19m 9f | VR (semi-immersive) distraction | 1. Non-VR distraction 2. no distraction | post-procdure | Missing >10% | Self-report pain (Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool) | MD 21.20, 95% CI -8.31 to 50.71 | |||||||

| Lambert 2020 | L | Kipping | 2012 | 41 | 11 to 17y | 28m 13f | VR (immersive) distraction | Non-VR distraction | After procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | MD -1.77, 95% CI -2.74 to -0.80 | Observed pain (FLACC) | no difference | Nausea (side effects) | no difference | |||

| Lambert 2020 | M | Koushali | 2017 | 40 | 7 to 12y | 26m 14f | VR (immersive) distraction | No distraction | Immediately after procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (Wong and Baker Scale) | MD -2.90, 95% CI -3.57 to -2.23 | |||||||

| Lambert 2020 | N | Nilsson | 2009 | 42 | 5 to 18y | 25m 17f | VR (non-immersive) distraction | No distraction | 3-5 minutes after procedure | Missing <10% | Self-report pain (CAS and FAS) | MD 0.54, 95% CI -0.32 to 1.40; | Observed pain (FLACC) | MD 0.10, 95% CI -0.22 to 0.42 | |||||

| Lambert 2020 | O | Schmitt | 2011 | 53 | 6 to 18y | 43m 10f | VR (immersive) distraction | Non-VR distraction | Immediately after procedure | No missing data | Self-report pain (GRS) | MD -14.33, 95% CI -25.42 to -3.24 | |||||||

| Lambert 2020 | P | Walther-Larsen | 2019 | 59 | 7 to 16y | 52m 7f | VR (immersive) distraction | Non-VR distraction | 15 minutes after procedure | Missing <10% | Self-report pain (VAS-score) | no difference | Self-report satisfaction (VAS-score) | no difference | |||||

| Lambert 2020 | Q | Wolitzky | 2005 | 20 | 7 to 14y | 12m 8f | VR (immersive) distraction | No distraction | Immediately after procedure | Missing <10% | Observed pain (CHEOPS) | MD -3.40, 95% CI -5.01 to -1.79 | Self-report anxiety (VAS-score) | no difference | Pulse rate | ||||

| Manyande 2015 | A | Akinci | 2008 | 100 | 2 to 10y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | No missing data | Observer-report distress | MD 0 [95% CI: -0.39,0.39] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | B | Arai | 2007 | 60 | 1 to 3y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | C | Berghmans | 2012 | 120 | 6m to 16y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | No missing data | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | D | Bevan | 1990 | 134 | 2 to 10y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Observer-report distress | MD 0 [95% CI: -0.34,0.34] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | E | Calipel | 2005 | 50 | 2 to 11y | not reported | Hypnosis | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Observer-report distress | MD 0.59 [95% CI: 0.33,1.04] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | F | Campbell | 2005 | 198 | 3 to 10y | not reported | Preparation and distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | 15% missing data | no effect measure | ||||||||

| Manyande 2015 | G | Fernandes | 2010 | 70 | 5 to 10y | 53m 17f | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | No missing data | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | H | Golan | 2009 | 65 | 3 to 8y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | No missing data | Observer-report distress | MD -12.7 [95% CI: -21.67,-3.73] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | I | Kain | 1996b | 84 | 1 to 6y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | <10% missing data | Outcome in parent | na | Time to induction | MD -0.2[95% CI: -0.65,0.25] | |||||

| Manyande 2015 | J | Kain | 1998 | 93 | 2 to 8 y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Co-operation | MD 12.47 [95% CI: 0.72,216.2] | Time to induction | MD -1.7[95% CI: -2.28,-1.12] | |||||

| Manyande 2015 | K | Kain | 2000 | 103 | 2 to 8y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | L | Kain | 2001 | 70 | 2 to 7y | not reported | Music distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | M | Kain | 2003 | 80 | about 5 y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | No missing data | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | N | Kain | 2004 | 123 | 3 to 7y | not reported | Music distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | O | Kain | 2007 | 308 | 2 to 10y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | <10% missing data | Observer-report distress | MD -0.08[95% CI: -0.36,0.21] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | P | Kain | 2009 | 61 | not reported | not reported | Parental distraction | One parent present | After procedure | <10% missing data | Co-operation | MD 1.88[95% CI: 0.61,5.72] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | Q | Kazak | 2010 | 60 | 2 to 6y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | No missing data | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | R | MacLaren | 2008 | 112 | 2 to 7y | not reported | Explanation | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | <10% missing data | Observer-report distress | MD 6.44 [95% CI: 0.78,53.23] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | S | McEwen | 2007 | 122 | not reported | not reported | Explanation (parents) | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | T | Meisel | 2009 | 61 | 3 to 12y | not reported | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | U | Mifflin | 2012 | 89 | 2 to 10y | not reported | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | <2% missing data | Outcome in parent | na | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | V | Palermo | 2000 | 83 | 1 to 12m | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | After procedure | >10% missing data, possibly differential | Observer-report distress | MD 0.4 [95% CI: -0.07,0.86] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | W | Patel | 2006 | 112 | 4 to 12y | not reported | Distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | After procedure | No missing data | Observer-report distress | MD -9.8 [95% CI: -19.42,-0.18] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | X | Vagnoli | 2005 | 40 | 5 to 12y | not reported | Distraction | parental presence | After procedure | No missing data | Observer-report distress | MD -30.75[95% CI: -46.36,-15.14] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | Y | Vagnoli | 2010 | 75 | 5 to 12y | not reported | Distraction | One parent present | After procedure | No missing data | Observer-report distress | MD -32.24[95% CI: -44.5,-19.98] | |||||||

| Manyande 2015 | Z | Wang | 2004 | 67 | 2 to 7y | not reported | Acupunture | "Sham" acupuncture | No missing data | Observer-report distress | MD -17 [95% CI: -30.51,-3.49] | ||||||||

| Manyande 2015 | AA | Wright | 2010 | 61 | 3 to 6y | not reported | Parental distraction | No parent present | No missing data | Observer-report distress | MD 0.05 [95% CI: -0.45,0.56] | ||||||||

| Manyande 2015 | AB | Zuwala | 2001 | 80 | 10m to 10y | not reported | Explanation | Standard care (may also include distraction) | No missing data | Outcome in parent | na | ||||||||

| Riddell 2015 | I | Basiri-Moghadam | 2014 | 50 | 4m | not reported | Toy distraction | 1. Lidocaine cream 2. Standard care | not reported | Incomplete data addressed | Distress (MBPS) | See comment in Cohen 2002 | |||||||

| Riddell 2015 | A | Cohen | 2002 | 90 | 2m to 3y | not reported | Video and toy distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | not reported | Incomplete data addressed | Distress (MBPS) | 1. Video distraction: SMD -0.68 [95% CI, -1.04 to -0.32] in favour of distraction 2. Toy distraction SMD -0.47 [95% CI, -0.91 to -0.02] in favour of distraction 3. Nondirected toy distraction SMD -0.93 [95% CI, -1.86 to -0.00] in favour of toy distraction |

|||||||

| Riddell 2015 | B | Cohen | 2006 | 84 | 12 to 18m | not reported | Distraction | 1. Lidocaine cream 2. Standard care | not reported | Incomplete data not addressed | Distress (MBPS) | See comment in Cohen 2002 | |||||||

| Riddell 2015 | C | Cohen | 2006 | 136 | 1 to 21m | not reported | Video distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | not reported | Incomplete data not addressed | Distress (MAISD) | See comment in Cohen 2002 | |||||||

| Riddell 2015 | E | Cramer-Berness | 2005 | 117 | 2 to 24m | not reported | Toy or tickling distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | not reported | Incomplete data addressed | Distress (MBPS) | See comment in Cohen 2002 | |||||||

| Riddell 2015 | F | Cramer-Berness | 2005 | 123 | 2 to 24m | not reported | Toy distraction or supportive care by parent | Standard care (may also include distraction) | not reported | Unclear whether incomplete data was addressed | Distress (MBPS) | See comment in Cohen 2002 | |||||||

| Riddell 2015 | D | Gedam | 2013 | 350 | 12 to 30m | not reported | Video and toy distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | not reported | Incomplete data addressed | Distress (FLACC) | See comment in Cohen 2002 | |||||||

| Riddell 2015 | G | Hillgrove-Stuart | 2013 | 99 | 12 to 20m | not reported | Toy distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | not reported | Incomplete data addressed | Distress (MBPS) | See comment in Cohen 2002 | |||||||

| Riddell 2015 | J | Ozdemir | 2012 | 120 | 2m | not reported | Toy or music distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | not reported | Incomplete data addressed | Distress (MBPS) | See comment in Cohen 2002 | |||||||

| Riddell 2015 | H | Singh | 2012 | 90 | 1 to 3y | not reported | Toy or music distraction | Standard care (may also include distraction) | not reported | Incomplete data addressed | Distress (FLACC modified) | See comment in Cohen 2002 |

Physiological interventions

Randomized controlled trials

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Morrow 2010 |

Type of study:

RCT

Setting and country: Tertiary hospital in the USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest:

Authors declare no conflicts of interest |

Inclusion criteria: Newborn infants born after at least 37 weeks of pregnancy, who were clinically stable and qualified for a total serum bilirubin (TSB) procedure. Exclusion criteria: “Infants who were admitted to the NICU, neonates born to diabetic mothers, those previously diagnosed with hyperbilirubinemia, as well as infants with other medical complications.”

N total at baseline: Intervention: 22 Control: 20

Important prognostic factors2: Gestational age ± SD: I: 39.45 (1.14) C: 38.77 (1.51)

Sex: I: 50% M C: 41.1% M

Weight: I: 3371.77 (417.96) C: 3546.88 (340.85)

Apgar at 1 min: I: 8.45 (0.65) C: 8.66 (0.47)

Vaginal birth: I: 77.2% C: 76.4%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Infants were swaddled and held upright during the procedure (90 degrees).

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Infants received standard care (30 degrees). |

Length of follow-up:

Experimental: 2 minutes 17 seconds (SD = 59)

Control: 2 minutes 47 seconds (SD = 85) Loss-to-follow-up:

N.A.

Incomplete outcome data:

N.A.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Pain (Neonatal Inventory Pain Scale).

Mean (SD) I: 1.3 (0.9) C: 2.7 (1.3)

t-test = -4.48 p<0.001 |

Conclusion from the author:

The RCT showed that swaddling the infant while holding it in an upright position significantly decreases the painscore compared to holing the infant in a standard care position during heel lance procedures. |

Notes:

-

Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

-

Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders)

-

For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

-

For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Systematic reviews

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Ueki, 2019

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis

Literature search up to October, 2017

21 studies included A: Aminabadi, 2008 B: Baba, 2010 C: Baxter, 2011 D: Roeber, 2011 E: Inal, 2012 F: Ching, 2014 G: Secil, 2014 H: Shilpapriya, 2015 I: Canbulat, 2015a J: Canbulat, 2015b K: Elbay, 2015 L: Bahorski, 2015 M: Moadad, 2016 N: Benjamin, 2016 O: Schreiber, 2016 P: McGinnis, 2016 Q: Dak-Albab, 2016 R: Bagherian, 2016 S: Sermet, 2016 T: Potts, 2017 U: Raslan, 2017 .....

Study design: 21 RCT (8 Crossover RCT B,F,H,K,Q,R,S,U)

Setting and Country: Clinics/Hospitals. USA, Turkey, India, Italy, Iran and Syria,

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: C: Author is developer of the Buzzy device D, P, R: funded by industry.

|

Inclusion criteria SR: Children with any condition undergoing a needle-related procedure (NRP).

Exclusion criteria SR: -

21 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: 1717 paediatric patients ranging from 15 days to 18 years of age

N, mean age A: n=52, 4.72 years B: n=20, 37 weeks C: n=81, 9.97 years D: n=90, 5.66 years E: n=120, 9.3 years F: n=72, 14 years G: n=60, N.A. H: n=60, 7.5 years I: n=104, 7 years J: n=176, 8.43 years K: n=120, 8.32 years L: n=118, N.A. M: n=50, 8.7 years N: n=100, N.A. O: n=71, 9 years P: n=56, N.A. Q: n=60, N.A. R: n=96, 5.94 years S: n=236, 7.31 years T: n=224, 8.17 years U: n=186, 8.2 years

….

Sex: Not specified |

Describe intervention:

A: Topical anesthetic agent and vibration of the injection site by a finger B: Hitachi Magic Wand With Wonder wand C: BUZZY D: Vibraject E: BUZZY F: Topical Anesthetic gel and DentalVibe G: VAD H: DentalVibe I: BUZZY J: BUZZY K: Topical anesthetic spray and DentalVibe L: BUZZY and topical anesthetic ointment M: BUZZY N: BUZZY without cold pack O: BUZZY P: Norco mini vibrator Q: DentalVibe R: “Cotton roll with topical anesthesia gel remaining in place with a mild vibratory stimulus applied by the left hand during injection lasting around 1 minute.” S: Topical anesthetic and DentalVibe .....

|

Describe control:

A: Topical anesthetic agent without vibration B: Without vibrator C: Normal practice D: Vibraject turned off E: No BUZZY F: Topical Anesthetic gel and DentalVibe turned off G: No VAD H: Topical Anesthesia I: No BUZZY J: No BUZZY K: Topical anesthetic spray and DentalVibe turned off L: Topical anesthetic ointment M: No BUZZY N: No BUZZY O: No Buzzy P: No vibrator Q: Topical analgesia R: “Cotton roll with topical anesthesia gel remaining in place without vibratory stimuli.” S: Topical anesthetic and DentalVibe turned off .....

|

End-point of follow-up:

Not applicable ….

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control)

O: 1/0 R: 17.5% overall ….

|

Self-rated Pain score - 1

Std. mean difference (95% CI) (IV, Random effect): C: -0.53 (95% CI -0.98 to -0.09) D: 0.31 (95% CI -0.10 to 0.73) E: -2.09 (95% CI -2.53 to -1.64) F: -1.07. (95% CI -1.57 to -0.58) H: -1.74 (95% CI -2.34 to -1.14) I: -0.79 (95% CI -1.18 to -0.39) J: -0.98 (95% CI -1.29 to -0.66) K: 0.20 (95% CI -0.15 to 0.56) L: -0.09 (95% CI -0.56 to 0.38) M: -0.75 (95% CI -1.33 to -0.17) S: -0.02 (95% CI -0.28 to 0.23) T: 0.03 (95% CI -0.23 to 0.29) U: 0.06 (95% CI -0.23 to 0.35)

…

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.55 (95% CI -0.92 to -0.18) favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 92% P-value = 0.003

Observer-rated pain score - 2

Std. Mean difference (95% CI) (IV, Random effect): B: -0.71 (95% CI -1.62 to 0.20) C: -0.61 (95% CI -1.06 to -0.17) D: -0.06 (95% CI -0.47 to 0.36) E: -1.97 (95% CI -2.40 to -1.53) G: -0.03 (95% CI -0.54 to 0.47) I: -1.63 (95% CI -2.08 to -1.19) K: 0.19 (95% CI -0.17 to 0.54) L: -0.11 (95% CI -0.47 to 0.26) M: -0.47 (95% CI -1.03 to 0.10) N: 0.07 (95% CI -0.33 to 0.46) P: -0.96 (95% CI -1.52 to -0.40) Q: -0.53 (95% CI -1.04 to -0.01) R: -0.67 (95% CI -1.08 to -0.26) S: -0.14 (95% CI -0.40 to 0.12) T: 0.05 (95% CI -0.22 to 0.31) U: -0.19 (95% CI -0.48 to 0.10)

Pooled effect (random effects model): -0.47 (95% CI -0.76 to -0.18) favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 88% P-value = 0.001

Anxiety, by observer-rated outcome measurement - 3.

Mean difference (95% CI) (IV, Random effect): E: -1.76 (95% CI -2.18 to -1.33) I: -1.50 (95% CI -1.93 to -1.06) J: -0.93 (95% CI -1.25 to 0.62) T: 0.03 (95% CI -0.23 to 0.29)

Pooled effect (random effects model): -1.03 (95% CI -1.85 to -0.20) favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 96% P-value = 0.01

Success rate of first venipuncture - 4

Odds Ration (M-H, Random effects, 95% CI): E: 0.54 (95% CI 0.15 to 1.95) O: 0.97 (95% CI 0.22 to 4.22) T: 1.12 (95% CI 0.50 to 2.48) C: 3.14 (95% CI 1.06 to 9.27)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 1.23 (95% CI 0.62 to 2.45) favoring intervention Heterogeneity (I2): 35% P-value = 0.56

|

Facultative:

The funnel plot and Egger’s test showed a possible publication bias for the self-rated pain studies. Excluding studies funded by the industry did not change the direction of results.

Participation bias is possible, as all but three studies excluded critical or chronically sick children.

High level of heterogeneity, possibly due to the differences between usual care as comparison.

Level of evidence: GRADE

Pain, as measured by self-rated outcome measurement, from NRP, is reduced by 0.36 SMD (GRADE level LOW)

Pain, as measured by observer-rated outcome measurement, from NRP, is reduced by 0.34 SMD (GRADE level LOW)

Anxiety, measured by observers using scales, from NRP is reduced by 0.74 SMD (GRADE level LOW)

Sensitivity analyses (excluding small studies; excluding studies with short follow-up; excluding low quality studies; relevant subgroup-analyses);

When topical anesthesia was used during the intervention as well as during the control, no vibratory stimulation was deemed statistically significant in reducing pain score.

A sub-analysis differentiating between controlgroups with no device and controlgroups with the device turned off, showed that vibrations did not significantly reduce pain score: