Totale versus hemiprothese bij patiënt met artrose en intacte cuff

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van een hemiprothese in vergelijking met een totale schouderprothese bij een patiënt met glenohumerale artrose en een functioneel intacte rotator cuff en een indicatiestelling voor een schouderprothese?

Aanbeveling

Plaats bij patiënten met glenohumerale artrose en een functioneel intacte rotator cuff bij voorkeur een totale schouderprothese.

Overweeg bij een jongere patiënt met glenohumerale artrose en een functioneel intacte rotator cuff een hemiprothese te plaatsen.

Overweeg in het geval van een ongeschikt glenoid bij een patiënt met glenohumerale artrose en een functioneel intacte rotator cuff een hemi- of een omgekeerde schouderprothese te plaatsen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar patiëntrelevante klinische uitkomsten na een totale schouderprothese en een hemiprothese bij patiënten met schouderartrose en een functioneel intacte rotator cuff. In drie gerandomiseerde studies met kleine patiëntaantallen leken de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en functie in het voordeel uit te vallen van de totale schouderprothese. De belangrijke uitkomstmaten complicaties en prothese survival werden beschreven, maar door de zeer lage bewijskracht konden geen conclusies worden getrokken. De belangrijke uitkomstmaat kwaliteit van leven leek niet klinisch relevant verschillend tussen de twee prothesen. Patiënttevredenheid en prothese overleving werden niet beschreven in de gevonden literatuur. De totale bewijskracht, de laagste bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten, is laag door de geringe patiëntaantallen en beperkingen in de studieopzet. Op basis van deze resultaten lijkt er bij een maximale follow-up van 3 jaar een voorkeur te zijn voor een totale schouderprothese ten opzichte van een hemiprothese.

Volgens de werkgroep is er een voorzichtige trend zichtbaar in de gerefereerde studies dat de pijnverlichting en functieverbetering beter is na een totale schouderprothese dan bij een hemiprothese, bij patiënten met glenohumerale artrose en een functioneel intacte rotator cuff. Of er een verschil is in aantal complicaties tussen de prothesen is onduidelijk, maar progressieve glenoid erosie na een hemiprothese, met als gevolg een toename van pijn, werd al binnen 2 jaar waargenomen na de operatie. Progressieve glenoid erosie zal vaker gezien worden als patiënten langer vervolgd worden na het plaatsen van de hemiprothese. Deze complicatie kan aanleiding zijn om patiënten opnieuw te opereren en een glenoid prothese bij te plaatsen of op indicatie een totale revisie en conversie naar een omgekeerde schouderprothese te verrichten. In de enige studie met een langere follow-up van 10 jaar leken meer (pijnlijke) glenoid erosies gezien na een hemiprothese, dan bij de twee studies met een kortere follow-up van 2 tot 3 jaar.

Een nadeel van het plaatsen van een totale schouderprothese kan zijn dat er in de loop van tijd loslating gezien wordt van de glenoid prothese. Deze complicatie werd niet gerapporteerd in de gerefereerde studies. Studies met grotere aantallen en langere follow-up kunnen hier meer duidelijkheid over geven. Met name bij jongere, actieve patiënten kan dit een belangrijke overweging zijn om een hemiprothese te plaatsen, en dus geen risico te lopen op een loslating van de glenoid prothese. De werkgroep adviseert om bij jongere patiënten een hemiprothese te plaatsen, vanwege de verhoogde kans op loslating van het glenoid deel bij een totale schouderprothese. Zoals eerder beschreven kan op basis van de literatuur geen specifiek afkappunt voor leeftijd worden gegeven. Kalenderleeftijd is geen goed criterium; het gaat meer om biologische leeftijd, activiteitsniveau en vitaliteit van de patiënt. De behandelend arts zal altijd een inschatting moeten maken op basis van de kenmerken van de individuele patiënt.

Om een totale schouderprothese te kunnen plaatsen moet de kwaliteit van het glenoid beoordeeld worden. In het geval van ernstige glenoid erosie, glenoid defecten of slechte botkwaliteit hebben de huidige systemen de opties om het glenoid te augmenteren en zo een totale schouderprothese te plaatsen. Mocht dit niet tot de technische mogelijkheden behoren, dan moet er gekozen worden ofwel voor een hemiprothese, danwel voor een omgekeerde schouderprothese (eventueel met botgraft).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

De mogelijk grotere verbetering in pijn en functie bij een totale schouderprothese zijn voor een patiënt belangrijk, onafhankelijk van de pathologie. Daarnaast is de kans op re-operaties kleiner bij het plaatsen van een totale schouderprothese. Een voordeel van de hemiprothese is dat de operatie en daarmee de narcose korter zijn, en daarmee minder belastend voor de patiënt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Een totale schouderprothese is duurder dan een hemiprothese. De verwachte voordelen in klinische effectiviteit van een totale schouderprothese bij een oudere patiënt, wegen volgens de werkgroep op tegen de iets hogere kosten van een totale schouderprothese.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het plaatsen van een totale schouderprothese is technisch uitdagender dan het plaatsen van een hemiprothese. Echter, voor een ervaren orthopedisch chirurg, gespecialiseerd in schouderchirurgie, zal dit geen belangrijke overweging zijn bij de keuze voor een hemi- of totale schouderprothese. Volgens de werkgroep is de operatieduur geen relevante overweging om te kiezen voor een hemiprothese.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

In drie gerandomiseerde studies met kleine patiëntaantallen leken de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en functie in het voordeel uit te vallen van totale schouderprothese. Bij de totale schouderprothese zou de glenoidcomponent echter los kunnen gaan zitten. Dit gebeurt waarschijnlijk sneller als de schouder meer belast wordt en er meer krachten op komen te staan, bijvoorbeeld bij jongere patiënten. Een revisieoperatie is lastiger bij een totale schouderprothese dan bij een hemiprothese. Bij jongere patiënten lijkt een hemiprothese daarom de voorkeur te hebben.

Bij een hemiprothese kan op langere termijn erosie met botverlies van het glenoid ontstaan ten gevolge van metaal-botcontact. Dit kan leiden tot pijnklachten en kan een indicatie zijn voor een revisieoperatie. Bij oudere patiënten met minder goede botkwaliteit is dit risico groter. Bij oudere patiënten lijkt het dus raadzaam eerder een totale schouderprothese te plaatsen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij patiënten met glenohumerale artrose en een functioneel intacte rotator cuff kan gekozen worden voor een totale schouderprothese of een hemiprothese. In het verleden werd vaak gekozen voor een hemiprothese, omdat dit chirurgisch technisch eenvoudiger is. Op dit moment wordt echter steeds vaker gekozen voor een totale schouderprothese, omdat er aanwijzingen zijn dat de uitkomsten op lange termijn daarvan beter zijn. Het is op dit moment onduidelijk wat de beste keuze is.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

Low GRADE |

The level of pain may be lower after total shoulder arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff when measured as a pain component in the UCLA shoulder score, but not when measured with the McGill pain score and the McGill pain Visual Analogue Scale.

Sources: (Sandow, 2013; Lo, 2005; Gartsman, 2000) |

|

Low GRADE |

Shoulder function may be higher after total shoulder arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff.

Sources: (Gartsman, 2000; Sandow, 2013; Lo, 2005) |

|

Low GRADE |

Quality of life may be comparable after total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff.

Sources: (Lo, 2005) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether total shoulder arthroplasty leads to fewer complications compared to hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff.

Sources: (Sandow, 2013; Lo, 2005; Gartsman, 2000) |

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown whether total shoulder arthroplasty affects prosthesis survival compared to hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff. |

|

- GRADE |

It is unknown whether patient satisfaction differs in patients after a total shoulder arthroplasty compared to an hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Sandow (2013) performed a randomized controlled trial in patients with osteoarthritis and an intact rotator cuff. The aim of the study was to compare the short-term efficacy of hemiarthroplasty (HA) and total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Patients were identified who might be suitable for the study where there was a reasonable expectation that the rotator cuff was intact, there was obvious advanced osteoarthritis of the shoulder, and no evidence of infection, inflammatory disease, or previous fracture. Patients were excluded if there was a significant rotator cuff tear (such that a major defect would remain after subscapularis tendon repair and rotator interval closure). The intervention consisted of a TSA and the control consisted of an HA. A total of 20 patients (5 men, 15 women) were included in the TSA group and 13 (6 men, 7 women) in the HA group. Patients were a median age of 72 years in the TSA group and 68 years in the HA group. Before the recruitment of sufficient patients to achieve the number identified in the sample size calculation, post-operative reviews noted that 2 HA patients required early revision and 2 further patients were experiencing a deterioration of their pain levels. The institutional review board independently assessed the outcomes up to that stage and recommended that recruitment of patients be suspended until all of those patients within the study had reached the 2-year mark post-operatively, at which time the results were again analysed. Because a significant difference was identified at that review, the study was terminated. The study followed participants for 10 years, follow-up data was available at 2,3 and 10 years. At ten years, 14 patients with a TSA and 8 patients with a HA were available for follow-up.

Lo (2005) performed a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial in patients with osteoarthritis of the shoulder. The purpose of the study was to compare the effectiveness of hemiarthroplasty with that of total shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the shoulder. The patients included in the study had a diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis of the shoulder, had a failure of a minimum of six months of nonoperative treatment (including analgesics, anti-inflammatory medication, and physiotherapy), and wished to have surgical intervention. Primary osteoarthritis of the shoulder was defined as shoulder pain; no history of major trauma, infection, osteonecrosis, cuff tear arthropathy, chronic dislocation, or a secondary cause of osteoarthritis; and radiographic evidence of joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, and/or subchondral sclerosis. Exclusion criteria included a condition other than shoulder osteoarthritis that would substantially contribute to shoulder dysfunction (for example cervical spine disease), a rotator cuff tear (> 1 cm), inflammatory arthritis, post-capsulorrhaphy osteoarthritis, a major medical illness that would substantially influence quality of life (for example unstable angina), an active infection, substantial muscle paralysis, and a lack of fitness for surgery or an unwillingness to be followed for two years. The intervention consisted of a Neer Series-II modular total shoulder arthroplasty and the control consisted of a hemi prosthesis (3M Modular Shoulder System; 3M Canada, London, Ontario, Canada). A total of 20 patients were included in the total shoulder arthroplasty group and 21 patients in the hemiarthroplasty group. Follow-up was 2 years. One patient in the hemiarthroplasty group had a full-thickness 1-cm tear of the supraspinatus tendon, which was repaired. Patients were a mean age of 70.4 years (SD= 9.0) in the total shoulder arthroplasty group and 70.3 years (SD=7.3) in the hemiarthroplasty group. The male to female ratio was 1:1 in the total shoulder arthroplasty group and 8:13 in the hemiarthroplasty group.

Gartsman (2000) performed a randomized controlled trial in patients with degenerative osteoarthritis. The aim of the study was to evaluate the outcomes of treatment of osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint with or without resurfacing of the glenoid. All patients who were to have a shoulder arthroplasty between December 1992 and December 1996 were evaluated for inclusion in this study. The criteria for inclusion in the study were a diagnosis of osteoarthritis, an intact rotator cuff, and a concentric glenoid. A diagnosis other than osteoarthritis was a criterion for exclusion. The intervention consisted of a total shoulder arthroplasty and the control consisted of a hemiarthroplasty. A total of 27 shoulders in 25 patients (15 men and 10 women, two of whom had a bilateral procedure) had a total shoulder arthroplasty and 24 shoulders in 22 patients (13 men, two of whom had a bilateral procedure, and 9 women) had a hemiarthroplasty. The mean age ± standard deviation of the patients who had a total shoulder arthroplasty was 65.3 ± 8.4 years (range, 50 to 86 years) compared with 64.6 ± 6.3 years (range, 45 to 78 years) for the patients who had the hemiarthroplasty. The mean duration of follow-up was 34 months (range 27 to 70) after HA, and it was 36 months (range 24 to 72 months) after TSA.

Results

Pain (critical)

Two studies reported pain with the UCLA Shoulder Score, with 0 as the worst function and 10 as the least pain. Sandow (2013) reported a post-operative (3 years) score of 10 (range 8 to 10) and 4 (range 2 to 8) in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. Gartsman (2000) reported a post-operative score of 8.2 and 6.0 in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. These differences are clinically relevant. Due to missing information about the data distribution, it was not possible to calculate the pooled differences.

Lo (2005) reported pain with the McGill pain score (0 to 78; higher = worse) and the McGill pain Visual Analogue Scale (0 to 100; higher = worse). A post-operative McGill pain score of 0.9 ± 1.4 and 2.7 ± 6.8 was reported in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. The mean difference of -1.80 (95% CI -4.77, 1.17) in favour of the total shoulder arthroplasty group was not clinically relevant. A post-operative McGill Visual Analogue Scale of 6.1 ± 13.5 and 13.9 ± 27.4 was reported in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. The mean difference of -7.80 (95% CI -20.93, 5.33) in favour of the total shoulder arthroplasty group was not clinically relevant.

Function (critical)

Shoulder function was reported using the Constant and Murley shoulder score and the UCLA score, which are scores combining functional scores, as well as pain and patient satisfaction. If available, also the function sub-scores were reported.

Two studies reported the Constant and Murley shoulder score. At 3-year follow-up, Sandow (2013) reported a higher median score of 77 (range 67 to 95) after TSA versus 54.5 (range 43 to 59) after HA. This is a clinically relevant difference. However, Lo (2005) did not find clinically relevant differences at 2 years follow-up, with 70.8 ± 17.2 after TSA and 67.1 ± 19.6 after HA.

Three studies used the UCLA score to express function. Gartsman (2000) reported a UCLA score (35-point scale) at 1 year follow-up of 27.4 ± 4.9 in the TSA group, versus 23.2 ± 5.9 in the HA group. Sandow (2013) found a 3-year postoperative median score of 33 (range 24 to 34) after TSA, and 18.5 (10 to 25) after HA. These differences are clinically relevant. Lo (2015), however, did not find clinically relevant differences at 2-year follow-up, with 26.7 ± 3.8 for TSA and 24.2 ± 5.0 for HA.

Two studies reported function with the UCLA Shoulder Score functional component, with 0 as the worst function and 10 as the best function. Sandow (2013) reported a post-operative (3 years) score of 10 (range 4 to 10) in the TSA group and 4 (2 to 6) in the hemiarthroplasty group. Gartsman (2000) reported post-operative scores of 7.3 after total shoulder arthroplasty and 6.2 after hemiarthroplasty. The higher function scores in TSA were clinically relevant. Taken together, function scores seem higher after TSA compared with HA.

Quality of life

Two studies reported quality of life. Sandow (2013) reported quality of life with the use of the Visual Analogue Scale, with 0 as the best quality and 10 as the worst quality. A post-operative (3 years) VAS of 0.5 (range 0 to 4.8) and 4.4 (range 0 to 6.9) was reported in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. Due to missing information regarding data distribution, no conclusions can be drawn from these results.

Lo (2005) reported quality of life using the Generic Quality of Life with Short Form-36 Mental and Physical Component Summary Scores (score range, 0 to 100; higher score = less disability) and the Disease-Specific Quality of Life/Function with Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder Index (WOOS) Scores. A score of 0 signifies that the patient had an extreme decrease in the shoulder-related quality of life, whereas a score of 100 signifies that the patient had no decrease in the shoulder-related quality of life. A post-operative SF-36 mental component scale of 58.4 ± 9.1 and 57.4 ± 10.9 was reported in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. The mean difference of -1.00 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from -7.14 to 5.14 in the favour of the total shoulder arthroplasty group, was not clinically relevant. A post-operative SF-36 physical component scale of 42.1 ± 13.2 and 42.9 ± 10.9 was reported in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. The mean difference of 0.8 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from -6.63 to 8.23 in favour of the hemiarthroplasty group, was not clinically relevant. A post-operative WOOS-score of 90.6 ± 13.2 and 81.5 ± 24.1 was reported in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. The mean difference of 9.10 (95% CI -2.72, 20.92) in favour of the total shoulder arthroplasty group was not clinically relevant.

Complications

Three studies reported complications. Sandow (2013) reported three of the twenty patients (15%) in the total shoulder replacement group had to undergo revision due to malposition and glenoid loosening, in comparison with four of the thirteen patients (31%) in the hemiarthroplasty group due to severe pain secondary to glenoid erosion in one and a deterioration of shoulder function in three.

Lo (2005) reported two of the twenty patients (10%) had intraoperative complications in the total shoulder replacement group (one nondisplaced fracture of the greater tuberosity and one fracture of the anterior-inferior corner of the glenoid during reaming) in comparison with two of the twenty-one patients (9.5%) in the hemiarthroplasty group. Late complications included superior migration of the humeral component in three patients with a hemiarthroplasty (only one patient was symptomatic) and anterosuperior migration in one patient with total shoulder replacement, indicating rotator cuff deficiency. All patients declined further treatment. An infection developed in one patient after a total shoulder arthroplasty which was treated with two operative debridements. Progressive glenoid arthrosis developed in three other patients with a hemiarthroplasty. They had pain that was severe enough to require a revision to a total shoulder arthroplasty. This was performed in two of them and was considered for the third.

Gartsman (2000) reported that three patients who received a hemiarthroplasty had a reoperation for resurfacing of the glenoid. The indication for the operation in each patient was increasing pain and decreasing space between the humeral head and the glenoid as noted on plain radiographs.

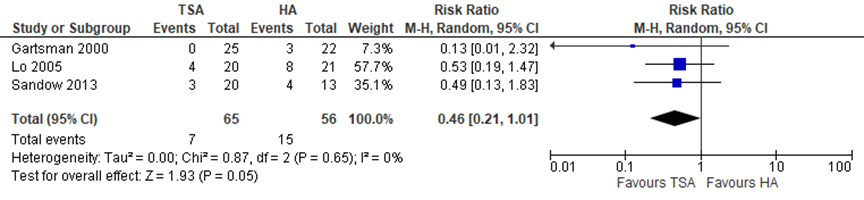

In patients with a hemiarthroplasty, symptomatic glenoid erosion was found within a short-term period of two years in 14% (Lo) and in 13% (Gartsman) of the patients, and within a long-term period of ten years in 31% (Sandow). The RR of 0.46, with a 95% CI from 0.21 to 1.01, was clinically relevant (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Complications after total or hemi shoulder arthroplasty

Z: p-value of pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval

Patient satisfaction

Two studies reported patient satisfaction on the UCLA Shoulder Score, with 0 as least satisfaction and 5 as maximal satisfaction. Sandow (2013) reported a post-operative (3 years) satisfaction score of 5 (range 5 to 5) and 5 (0 to 5) in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. Gartsman (2000) reported a post-operative satisfaction score of 3.8 and 3.2 in the total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty group, respectively. Due to missing information about the data distribution, it was not possible to calculate the pooled differences. No conclusions can be drawn from the results.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures “pain”, “function” and “quality of life” comes from randomized controlled trials and therefore starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias) and limited population size (imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures “complications” comes from randomized controlled trials and, therefore, starts high. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias), overlap of the confidence interval with the limits of clinical decision making, and limited population size (both imprecision).

The level of evidence for the outcomes “prosthesis survival” and “patient satisfaction” could not be assessed because there were no studies found which compared total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (dis)advantages of a total shoulder arthroplasty compared to a hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff?

P: patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a functionally intact rotator cuff and an indication for shoulder arthroplasty;

I: total shoulder arthroplasty;

C: hemiarthroplasty;

O: pain, function, quality of life, complications, prosthesis survival, patient satisfaction.

Relevant outcomes

The guideline development group considered pain and function as critical outcomes for decision making; and quality of life, complications, prosthesis survival, and patient satisfaction as important outcomes for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcomes listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group used the GRADE-standard limit of 25% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for dichotomous outcomes and 10% for continuous variables (VAS-scales and function scores).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Pubmed and Embase were searched with relevant search terms up to and including November 28, 2019. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. One search was performed for patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis or with avascular necrosis of the humeral head. The systematic literature search resulted in 481 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews or randomized controlled trials, comparing total shoulder prosthesis with hemi prosthesis in patients with an indication for a shoulder prosthesis. For literature about patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis, 31 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 28 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 3 studies were included.

Results

Three randomized clinical trials were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000 Jan;82(1):26-34. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200001000-00004. PMID: 10653081.

- Lo IK, Litchfield RB, Griffin S, Faber K, Patterson SD, Kirkley A. Quality-of-life outcome following hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005 Oct;87(10):2178-85. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02198. PMID: 16203880.

- Sandow MJ, David H, Bentall SJ. Hemiarthroplasty versus total shoulder replacement for rotator cuff intact osteoarthritis: how do they fare after a decade? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013 Jul;22(7):877-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.10.023. Epub 2013 Jan 16. PMID: 23333174.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Sandow, 2013 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: multicentre, Australia, United Kingdom, New Zealand

Funding and conflicts of interest:An educational grant was received from DePuy to initiate the study in 1994. No other funding has been received. The authors, their immediate families, and any research foundations with which they are affiliated have not received any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article |

Inclusion criteria: Patients were identified who might be suitable for the study where there was a reasonable expectation that the rotator cuff was intact, there was obvious advanced osteoarthritis of the shoulder, and no evidence of infection, inflammatory disease, or previous fracture. Exclusion criteria: Not described

N total at baseline: Intervention: 20 patients Control: 13 patients

Important prognostic factors2: Median age: I: 72 years C: 68 years

Sex: I: 25% M C: 46% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention: Total shoulder replacement

|

Describe control: hemiarthroplasty

|

Length of follow-up: 3 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 6 (32%) Reason: Died of unrelated causes

Control: 5 (35%) Reason: Died of unrelated causes

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

1. Pain at 3 year follow-up Constant Score, mean (range) (least pain = 15; most pain = 0) Intervention Pre-op = 5 (0-5) Post-op = 15 (5-15)

Control Pre-op = 5 (0-10) Post-op = 5 (0-15)

UCLA score, mean (range) (worst pain = 0; least pain = 10) Intervention Pre-op = 2 (1-6) Post-op = 10 (8-10)

Control Pre-op = 2 (1-4) Post-op = 4 (2-8)

Visual analog scale, mean (range) (no pain = 0; worst pain = 10) Intervention Pre-op = 7.3 (4.5-9.7) Post-op = 0.2 (0=4)

Control Pre-op = 7 (3.8-9.5) Post-op = 4.6 (0.4-8.5)

2. Function Constant Score (activities of daily living), mean (range) (most ADL = 20; least ADL = 0) Intervention Pre-op = 6 (0-12) Post-op = 16 (12-20)

Control Pre-op = 8 (0-18) Post-op = 10 (6-20)

UCLA score, mean (range) (worst function = 0; best function = 10) Intervention Pre-op = 3 (1-6) Post-op = 10 (4-10)

Control Pre-op = 4 (1-4) Post-op = 5 (2-10)

Visual analog scale, mean (range) (best function = 0; worst function = 10) Intervention Pre-op = 7.9 (1-9.8) Post-op = 0.4 (0-9.4)

Control Pre-op = 7 (3-9.5) Post-op = 4.6 (0.7-7.1)

3. Quality of life Visual analogue scale, mean (range) (best quality = 0; worst quality = 10) Intervention Pre-op = 6.2 (0-10) Post-op = 0.5 (0-4.8)

Control Pre-op = 6 (2.6-9.3) Post-op = 4.4 (0-6.9)

4. Side effects/ complications I: 1 patients (revision due to malposition) C: 0 patients

5. Patient satisfaction UCLA score, mean (range) (least satisfaction = 0; max satisfaction = 5) Intervention Pre-op = NA Post-op = 5 (5-5)

Control Pre-op = NA Post-op = 5 (0-5) |

Author’s conclusion: TSR has advantages over HA with respect to pain and function at 2 years, and there has not been a reversal of the outcomes on longer follow-up. This longer-term review does not support the contention that HA will avoid later TSR complications, and in particular, an unacceptable rate of glenoid component failure. |

|

Lo, 2005 |

Type of study: prospective, double-blind, randomized trial

Setting and country: single centre, Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest:In support of their research or preparation of this manuscript, one or more of the authors received grants or outside funding from 3M Canada. None of the authors received payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity. No commercial entity paid or directed, or agreed to pay or direct, any benefits to any research fund, foundation, educational institution, or other charitable or nonprofit organization with which the authors are affiliated or associated |

Inclusion criteria: The patients included in the study had a diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis of the shoulder, had a failure of a minimum of six months of nonoperative treatment (including analgesics, anti-inflammatory medication, and physiotherapy), and wished to have surgical intervention. Primary osteoarthritis of the shoulder was defined as shoulder pain; no history of major trauma, infection, osteonecrosis, cuff tear arthropathy, chronic dislocation, or a secondary cause of osteoarthritis; and radiographic evidence of joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, and/or subchondral sclerosis.

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria included a condition other than shoulder osteoarthritis that would substantially contribute to shoulder dysfunction (e.g., cervical spine disease), a rotator cuff tear (>1 cm), inflammatory arthritis, post-capsulorrhaphy osteoarthritis, a major medical illness that would substantially influence quality of life (e.g., unstable angina), an active infection, substantial muscle paralysis, and a lack of fitness for surgery or an unwillingness to be followed for two years.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 20 patients Control: 21 patients

Important prognostic factors2:

Mean age ± SD: I: 70.4 ± 9.0 C: 70.3 ± 7.3

Male:female ratio I: 10:10 C: 8:13

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention:

Neer Series-II modular total shoulder prosthesis

|

Describe control:

hemiprosthesis (3M Modular Shoulder System; 3M Canada, London, Ontario, Canada). |

Length of follow-up: 2 years

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

1. Pain McGill pain score, mean ± SD (0-78; higher = worse) Intervention Pre-op = 12.5 ± 9.4

Control Pre-op = 16.0 ± 10.6

the mean differnece between the hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty group was 1.80 favoring total shoulder arthroplasty (95% CI -1.2 to 4.8; 0-78 point scale, higher = worse McGill Visual analogue scale, mean ± SD (0-10; higher = worse) Intervention Pre-op = 65.0 ± 20.9

Control Pre-op = 65.2 ± 24.3

The mean difference between the hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty group was 7.80 (95% CI -5.33 to 20.93, 100 mm scale); the mean pain score was slightly lower (indicating less pain) in the TSA group 2. Function American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) evaluation form, mean ± SD higher = better function Intervention Pre-op = 30.7 ± 19.5 Post-op = 91.1 ± 14.3

Control Pre-op = 31.1 ± 16.6 Post-op = 83.1 ± 25.6

3. Quality of life Generic Quality of life with Short Form-36 Mental and Physical Component Summary Scores, mean ± SD score range, 0 to 100; higher score = less disability Intervention Pre-op = 51.4 ± 14.7 and 31.3 ± 8.4 Post-op = 58.4 ± 9.1 and 42.1 ± 13.2

Control Pre-op = 55.5 ± 11.8 and 29.5 ± 7.6 Post-op = 57.4 ± 10.9 and 42.9 ± 10.9

WOOS, mean ± SD score range, 0 to 1900; higher is worst or most symptomatic Intervention Pre-op = 31.4 ± 17.7

Control Pre-op = 33.5 ± 19.7

4. Side effects/ complications I: 2 patient s(nondisplaced fracture of the greater tuberosity and fracture of the anterior-inferior corner of the glenoid during reaming) C: 2 patients (intraoperative fracture)

5. Patient satisfaction Not reported |

Author’s conclusion: Both total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty improve disease-specific and general quality-oflife measurements. With the small number of patients in our study, we found no significant differences in these measurements between the two treatment groups. |

|

Gartsman, 2000 |

Type of study: randomized controlled trial

Setting and country: Single centre, United States of America

Funding and conflicts of interest:*No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. Funds were received in total or partial support of the research or clinical study presented in this article. The funding source was a research fellowship provided by HCA/Columbia and Texas Orthopedic Hospital (T. S. R.). |

Inclusion criteria: The criteria for inclusion in the study were a diagnosis of osteoarthritis, an intact rotator cuff, and a concentric glenoid.

Exclusion criteria: A diagnosis other than osteoarthritis was a criterion for exclusion

N total at baseline: Intervention: 25 patients (27 shoulders) Control: 22 patients (24 shoulders)

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 65.3 ± 8.4 years (range, 50 to 86 years) C: 64.6 ± 6.3 years (range, 45 to 78 years)

Sex: I: 60% M C: 59% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention: total shoulder arthroplasty

|

Describe control : hemiarthroplasty

|

Length of follow-up: I: 36 months (24 – 72) C: 34 months (range: 27 – 70)

Loss-to-follow-up: 4 patients, not stated from which group

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

1. Pain American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) evaluation form, mean (range 0-100; higher = better) Intervention Pre-op = 9.6 Post-op = 41.1

Control Pre-op = 9.4 Post-op = 30.2

UCLA score, mean (worst pain = 0; least pain = 10)

Intervention Pre-op = 1.5 Post-op = 8.2

Control Pre-op = 1.5 Post-op = 6.0

2. Function American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) evaluation form, mean (range 0-100; higher = better) Intervention Pre-op = 13.1 Post-op = 36.1

Control Pre-op = 13.2 Post-op = 34.9

UCLA score, mean (worst function = 0; best function = 10)

Intervention Pre-op = 1.3 Post-op = 7.3

Control Pre-op = 1.5 Post-op = 6.2

3. Quality of life Not reported

4. Side effects/ complications There were no complications in both groups

5. Patient satisfaction UCLA score, mean UCLA score, mean (range) (least satisfaction = 0; max satisfaction = 5) Intervention Pre-op = 0.1 Post-op = 3.8

Control Pre-op = 0.3 Post-op = 3.2 |

Author’s conclusion: Total shoulder arthroplasty provided superior pain relief compared with hemiarthroplasty in patients who had glenohumeral osteoarthritis, but it was associated with an increased cost of $1177 per patient |

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Sandow, 2013 |

yes |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

|

Lo, 2005 |

Yes |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Likely |

|

Gartsman, 2000 |

yes |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Bryant, 2005 |

Studies kwamen overeen met Cochrane review |

|

Duan, 2013 |

Studies kwamen overeen met Cochrane review |

|

Sayegh, 2015 |

Geen vergelijkende studies geïncludeerd |

|

Steinhaus, 2019 |

Verkeerde populatie |

|

Van de Sande, 2006 |

Geen vergelijkende studies geïncludeerd |

|

Van den Bekerom, 2013 |

Geen vergelijkende studies geïncludeerd |

|

Franceschi, 2017 |

Verkeerde studiepopulatie |

|

Norris, 2002 |

Geen vergelijkende studie |

|

Arman, 2003 |

Studie in het Duits |

|

Orfaly, 2003 |

Geen RCT |

|

Sowa, 2017 |

Geen RCT |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 02-11-2021

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 11-10-2021

Algemene gegevens

De herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten die een schouderprothese krijgen.

Werkgroep

- dr. J.J.A.M. van Raaij, orthopedisch chirurg bij Martini Ziekenhuis (voorzitter), NOV

- dr. T.D.W. Alta, orthopedisch chirurg bij Spaarne Gasthuis, NOV

- dr. C.P.J. Visser, orthopedisch chirurg bij Alrijne Ziekenhuis en Eisenhower Kliniek, NOV

- dr. O.A.J. van der Meijden, orthopedisch chirurg bij Albert Schweitzer Ziekenhuis, NOV

- dr. C. Th. Koorevaar, orthopedisch chirurg bij Deventer Ziekenhuis, NOV

- dr. H.J. van der Woude, radioloog bij OLVG, NVvR

- R. Schuurmans, Diagnostisch Fysiotherapeut en MSK echografist bij Flevoziekenhuis en Bergman Clinics Naarden, KNGF

- K.M.C. Hekman, fysiotherapeut en manueel therapeut bij Schoudercentrum IBC Amstelland, KNGF

- drs. G. Willemsen, voorzitter Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland

- N. Lopuhaä, beleidsmedewerker Patiëntbelangen, ReumaNederland

Met ondersteuning van

- dr. M. de Weerd, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot september 2019)

- drs. T. Geltink, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot december 2020)

- dr. M.S. Ruiter, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (vanaf september 2019)

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Van Raaij (voorzitter) |

Orthopedisch chirurg Martini Ziekenhuis Groningen |

Opleider orthopedie Martiniziekenhuis Groningen; secretaris/vice voorzitter ROGO orthopedie Noordoost; voorzitter COC Martiniziekenhuis Groningen; lid regionale COC OOR Noordoost; secretaris concilium orthopedicum, lid RGS orthopedie; bestuurslid werkgroep schouder/elleboog NOV; lid LEARN Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (onderzoeksgroep opleiding/onderwijs); docent Hanzehogeschool Groningen; reviewer diverse orthopedische tijdschriften; beoordelaar/reviewer ingediende projecten ZonMW; lid editorial board Orthopedics (orthopedisch journal); voorzitter stichting ortho research noord (extern gefinancierd door Smith en Nephew en door wetenschapscommissie Martiniziekenhuis Groningen) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Willemsen-de Mey |

Voorzitter Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Lopuhaä |

Beleidsmedewerker Patiëntenbelangen ReumaNederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Visser |

Orthopedisch chirurg Alrijne Ziekenhuis, Leiden |

Reviewer diverse orthopedische tijdschriften; |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van der Meijden |

Orthopedisch chirurg; Albert Schweitzer Ziekenhuis Dordrecht |

Reviewer diverse orthopedische tijdschrijften |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van der Woude |

Radioloog, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (Oost) Amsterdam |

Lid/consulent Nederlandse Commissie voor Beentumoren (onbezoldigd) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Alta |

Orthopedisch chirurg Spaarne Gasthuis (Haarlem/Hoofddorp) |

Congres Commissie Nederlandse Vereniging voor Arthroscopie

Bestuurslid Europese schouder en elleboog society en hoofd Health Care Delivery committeer

Wetenschappelijke commissie wereld schouder en elleboog congres |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Koorevaar |

Orthopedisch chirurg Deventer Ziekenhuis |

Opleider Orthopedie Deventer Ziekenhuis. Reviewer diverse orthopedische tijdschriften. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Schuurmans |

Flevoziekenhuis: Diagnostisch Fysiotherapeut en MSK echografist poli Orthopedie; Bergman Clinics: Diagnostisch Fysiotherapeut en MSK echografist op de schouderpoli van dr. van der List; |

Voorzitter Schouder Netwerk Flevoland (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hekman |

Fysio, -manueeltherapeut; Schoudercentrum IBC Amstelland Advanced clinical practioner; MC Jan van Goyen |

Bestuursvoorzitter Schouder Netwerken Nederland : onbetaald Gastdocent Nederlands Paramedisch Instituut : betaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntperspectief door Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en andere relevante patiëntenorganisaties uit te nodigen voor een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. Het verslag hiervan (zie bijlagen) is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen. Bovendien werd het patiëntperspectief vertegenwoordigd door afvaardiging van patiëntenorganisaties ReumaNederland en Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland in de werkgroep. Tot slot werden de modules voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en andere relevante patiëntenorganisaties en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die een schouderprothese krijgen. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door stakeholders door middel van een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

- Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

- Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

- Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

- Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

- Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html

- Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Pubmed

("Arthroplasty, Replacement, Shoulder"(Mesh) OR ats(tiab) OR total shoulder(tiab) AND ("Hemiarthroplasty"(Mesh) OR hemi shoulder(tiab) OR hemi arthroplast*(tiab) OR hemiarthroplast*(tiab) OR hemishoulder(tiab))

|

Search |

Query |

Items found |

|

Search #7 AND #10 |

||

|

Search #7 AND #9 |

||

|

Search #7 AND #8 |

||

|

Search "Epidemiologic Studies"(Mesh) OR cohort(tiab) OR (case(tiab) AND (control(tiab) OR controll*(tiab) OR comparison(tiab) OR referent(tiab))) OR risk(tiab) OR causation(tiab) OR causal(tiab) OR "odds ratio"(tiab) OR etiol*(tiab) OR aetiol*(tiab) OR "natural history"(tiab) OR predict*(tiab) OR prognos*(tiab) OR outcome(tiab) OR course(tiab) OR retrospect*(tiab) |

||

|

Search ((random*(tiab) AND (controlled(tiab) OR control(tiab) OR placebo(tiab) OR versus(tiab) OR versus(tiab) OR group(tiab) OR groups(tiab) OR comparison(tiab) OR compared(tiab) OR arm(tiab) OR arms(tiab) OR crossover(tiab) OR cross-over(tiab)) AND (trial(tiab) OR study(tiab))) OR ((single(tiab) OR double(tiab) OR triple(tiab)) AND (masked(tiab) OR blind*(tiab)))) |

||

|

https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/catalog/375 Meest sensitieve SR filter |

||

|

Search #3 AND #6 |

||

|

Search "Hemiarthroplasty"(Mesh) OR hemi shoulder(tiab) OR hemi arthroplast*(tiab) OR hemiarthroplast*(tiab) OR hemishoulder(tiab) |

||

|

Search "Arthroplasty, Replacement, Shoulder"(Mesh) OR ats(tiab) OR total shoulder(tiab) OR anatomical total shouder(tiab) |

Embase

(('total shoulder arthroplasty'/exp OR ats:ti,ab,kw OR 'total shoulder arthroplast*':ti,ab,kw OR 'anatomical total shouder':ti,ab,kw) AND ('hemiarthroplasty'/exp OR 'hemiarthroplast*':ti,ab,kw OR 'hemi shoulder prosthes*':ti,ab,kw OR 'hemi arthroplast*':ti,ab,kw OR 'hemi shoulder arthroplast*':ti,ab,kw))

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#25 |

#21 NOT #24 |

224 |

|

#24 |

#20 NOT #19 |

50 |

|

#23 |

#16 AND #22 |

3 |

|

#22 |

#19 OR #20 OR #21 |

299 |

|

#21 |

#3 AND #18 |

262 |

|

#20 |

#2 AND #18 |

61 |

|

#19 |

#1 AND #18 |

31 |

|

#18 |

#17 NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'conference paper'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

540 |

|

#17 |

#4 AND #7 |

577 |

|

#16 |

#13 OR #14 OR #15 |

4 |

|

#15 |

sandow AND shoulder AND replacement AND rotator AND cuff |

1 |

|

#14 |

lo AND arthroplasty AND 2005 AND shoulder AND hemiarthroplasty |

2 |

|

#13 |

gartsman AND glenoid AND osteoarthritis AND 2000 |

1 |

|

#7 |

'hemiarthroplasty'/exp OR 'hemiarthroplast*':ti,ab,kw OR 'hemi shoulder prosthes*':ti,ab,kw OR 'hemi arthroplast*':ti,ab,kw OR 'hemi shoulder arthroplast*':ti,ab,kw |

4321 |

|

#4 |

'total shoulder arthroplasty'/exp OR ats:ti,ab,kw OR 'total shoulder arthroplast*':ti,ab,kw OR 'anatomical total shouder':ti,ab,kw |

10902 |

|

#3 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

5033726 |

|

#2 |

('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it |

2316120 |

|

#1 |

('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

464452 |