Gecementeerde versus ongecementeerde glenoidfixatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van een gecementeerde glenoidcomponent in vergelijking met een ongecementeerde glenoidcomponent bij een totale schouderprothese?

Aanbeveling

Kies bij een anatomische totale schouderprothese bij voorkeur voor een gecementeerde glenoidcomponent.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van ongecementeerde fixatie ten opzichte van gecementeerde fixatie van het glenoidcomponent bij een totale schouderprothese. Er zijn verschillende typen ongecementeerde glenoidcomponenten: metal-backed, all-polyethyleen en trabecular metal. De laatste is relatief nieuw, en daarvan vinden we nog maar beperkt gegevens in de literatuur.

De cruciale uitkomstmaat protheseoverleving dan wel revisie werd in een aantal registerstudies beschreven met een redelijke bewijskracht. Bij ongecementeerde fixatie van het glenoid was de kans op revisie mogelijk ruim 3 maal zo groot als bij gecementeerde fixatie. Over de andere cruciale uitkomstmaat pijn kon geen uitspraak worden gedaan door de zeer lage bewijskracht. Daarmee was de totale bewijskracht zeer laag. De belangrijke uitkomstmaten functie en complicaties konden door de zeer lage bewijskracht geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming. Patiënttevredenheid en kwaliteit van leven werden niet beschreven in de gevonden literatuur. Op basis van de revisiedata gaat de voorkeur uit naar gecementeerde fixatie van het glenoidcomponent.

Hoewel er een verhoogde revisie kans is na ongecementeerde fixatie tegenover gecementeerde fixatie van de glenoidcomponent lijkt enig perspectief ter duiding nog wel van belang. De genoemde studies baseren zich op prothesen die hoofdzakelijk geplaatst zijn in de jaren ’90, bij het schrijven van deze richtlijn al met al dus ruim 20 jaar geleden. Inmiddels zijn er op het gebied van ontwerp nieuwe ontwikkelingen. Dit betreft onder andere verbeteringen in het metal-backed design (Castagna, 2010). Hierbij is een bijkomend voordeel dat deze makkelijk te reviseren is, indien nodig, naar een omgekeerde prothese. Daarnaast is er de ontwikkeling van hybride glenoidcomponenten (Nelson, 2018). Een hybride component bestaat uit een polyethyleen component die in een centrale peg van trabeculair titanium/metaal wordt geperst. Hierbij wordt voor de fixatie gebruik gemaakt van een minimale hoeveelheid cement voor het polyethyleen in combinatie met de ongecementeerde ingroei in het bot van het trabeculaire deel. Deze kan mogelijk ook volledig ongecementeerd worden bevestigd. De eerste middellange termijn resultaten van studies in cohort verband zijn veelbelovend (Friedman, 2019; Wijeratna, 2016). Resultaten voor de langere termijn, 10 jaar en langer, zijn nog niet bekend.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Voor de patiënt leidt het plaatsen van een gecementeerde glenoidcomponent van een anatomische schouderprothese waarschijnlijk tot een kleinere kans op revisie en langere levensduur van de glenoidcomponent ten opzichte van ongecementeerde fixatie. Voor de patiënt is dit een belangrijke reden om te kiezen voor een gecementeerde glenoidcomponent. Wel kan in sommige gevallen, indien een revisie plaats moet vinden, de ongecementeerde metal-backed component relatief eenvoudig gereviseerd worden. Hierbij hoeft slechts het polyethyleen gewisseld te worden. Een voorbeeld hiervan is falen van de anatomische prothese door bijvoorbeeld een niet functionerende rotator cuff. Dit betreft echter uiteraard niet de gevallen waarin loslating van de glenoidcomponent de reden voor revisie is. Hoewel de overige bewijslast betreffende de complicatie risico’s gering is, lijkt het complicatierisico na het plaatsen van een ongecementeerde glenoidcomponent algeheel hoger dan na een gecementeerde component. Hoewel dit niet expliciet onderzocht is, is het aannemelijk dat de opname- en revalidatieduur vergelijkbaar zullen zijn tussen de gecementeerde en ongecementeerde glenoidcomponent.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Qua kosten is het niet duidelijk of er een verschil is tussen het type fixatie. Aan de ene kant is er de meerprijs van cement, aan de andere kant is er het gebruik van schroeven ter fixatie naast de combinatie van metal-backed prothese en het polyethyleen welke bij de ongecementeerde component daarin geklikt wordt. Afhankelijk van lokale afspraken met de fabrikant die de prothesen levert zijn er mogelijk verschillen, maar deze zijn op voorhand niet duidelijk. Het lijkt voor zich te spreken dat de kosten in het geval van een (vroege) revisie naar een omgekeerde schouderprothese aanzienlijk hoger zullen uitvallen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Zowel een totale schouderprothese met een gecementeerde als met een ongecementeerde glenoidcomponent kennen goede resultaten. Het risico van revisie na een ongecementeerde glenoidcomponent op de lange termijn (10 tot 15 jaar) is echter wel significant groter. Hierbij wordt weliswaar de kanttekening gemaakt dat het onderzochte, ongecementeerde, metal-backed design van een oudere generatie is dan de huidige ontwerpen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Bij het plaatsen van een totale schouderprothese geeft het gebruik van een gecementeerde glenoidcomponent waarschijnlijk een lagere kans op revisie dan een (oudere generatie) ongecementeerde glenoidcomponent. Wegens het ontbreken van langetermijnresultaten van nieuwere generatie ongecementeerde glenoidcomponenten, is het vooralsnog onduidelijk of deze een gunstiger beloop geven.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De (fixatie van de) glenoidcomponent lijkt, meer dan de humeruscomponent, een cruciale rol te spelen in het succes van behandeling en de levensduur van een totale schouderprothese. Aanvankelijk werd de glenoidcomponent altijd met cement gefixeerd. In een poging om (snelle) loslating van gecementeerde componenten te voorkomen werd ook een ongecementeerde component ontwikkeld. De meest gebruikte ongecementeerde component, de zogeheten ‘metal-backed’ glenoidcomponent, waarbij een metalen kom met schroeven aan het glenoid gefixeerd wordt en een polyethyleen lager daarin gefixeerd, bracht echter ook de nodige problemen met zich mee. In de literatuur lijkt een gecementeerde glenoidcomponent, waarbij een polyethyleen lager direct met cement in het bot wordt gefixeerd, derhalve nog de gouden standaard, maar de meningen daarover verschillen. De afgelopen jaren zijn er voor beide technieken meerdere ontwikkelingen en voor- en nadelen gerapporteerd die de vraag doen rijzen welk type fixatie de voorkeur verdient.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Critical outcomes

|

Low GRADE |

Prosthesis survival at ten to fifteen years follow-up may be higher after cemented glenoid fixation than after cementless glenoid fixation in patients with total shoulder arthroplasty.

Sources: (Fox, 2009; Gauci, 2018; Page, 2018; Sharplin, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether pain is different between cementless glenoid fixation and cemented glenoid fixation in patients with total shoulder arthroplasty.

Sources: (Boileau, 2002; Gauci, 2018) |

Important outcomes

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether shoulder function is different between cementless glenoid fixation and cemented glenoid fixation in patients with total shoulder arthroplasty.

Sources: (Boileau, 2002; Gauci, 2018; Sharplin, 2020) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether complication rate is different between cementless glenoid fixation and cemented glenoid fixation in patients with total shoulder arthroplasty.

Sources: (Kilian, 2018; Gauci, 2018) |

|

- GRADE |

For the outcome patient satisfaction, it was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence, due to the absence data. |

|

- GRADE |

For the outcome quality of life, it was not possible to draw conclusions or grade the level of evidence, due to the absence data. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

In a double-blind RCT, Boileau (2002) compared cemented all-polyethylene glenoid components and cementless metal-backed components in total shoulder arthroplasty. Forty patients (20 per group, aged 55 to 85) with primary osteoarthritis were included in this French study. Inclusion criteria were disabling pain and poor function in patients in whom nonoperative conservative treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) had failed for at least 6 months. Exclusion criteria included shoulder disease other than OA (inflammatory arthritis, avascular necrosis, cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae), previous shoulder surgery, any evidence of infection or neurologic disease, and not being available for a minimum 3-year follow-up. TSA was performed using the deltopectoral approach and the Aequalis total shoulder system. The humeral component was cemented in all cases. Revision surgery, pain and function were reported. The study had a high risk of bias due to substantial loss to follow-up.

In an American RCT, Kilian (2018) compared TSA with a finned, cementless central pegged component (N=28, mean age 65) with TSA with a conventional cemented pegged glenoid component (N=26, mean age 67). Patients with an intact rotator cuff and primary glenohumeral OA, inflammatory arthritis, or instability arthropathy electing to undergo primary TSA in 2012 were included. History of skeletal dysplasia or prior shoulder infection were reasons for exclusion. The Aequalis Ascend Flex shoulder arthroplasty system was used for all 54 patients. Focus of the study, with a follow-up of 2 years, was on radiographic outcomes. The study reported complications. There was a high risk of bias due to considerable loss to follow-up.

In an American cohort study, Fox (2009) compared different glenoid implant designs in 1337 patients with 1542 TSAs. Six types of glenoid components were reported: Neer II all-polyethylene (N=99, mean age 63), Neer II metal-backed (N=254, mean age 64), Cofield 1 metal-backed bone-ingrowth (N=316, mean age 65), Cofield 1 all-poly keeled (N=18, mean age 54), and Cofield 2 all-poly keeled/pegged (not included in present analysis). All TSAs that used one of the glenoid components that were implanted at this institution from 1984 to 2004 were included in the study. Revision surgery and Kaplan-Meier survival with a follow-up of 15 years were reported. The study had a low risk of bias.

Gauci (2018) performed a cohort study specifically in young patients (< 60 years) with OA. In this French study, 69 consecutive TSAs were performed in 67 young patients with primary glenohumeral OA from 1994 to 1999. Inclusion criteria were: age < 60 years at the time of surgery, a single diagnosis of primary glenohumeral OA, an intact rotator cuff preoperatively, and minimum clinical and radiological follow-up of five years. Exclusion criteria included other diagnoses, those undergoing revision arthroplasty, and those whose operation involved glenoid bone graft. Cemented polyethylene (N=46, mean age 55) or cementless metal-backed Aequalis glenoid components (N=23, , mean age 53) were compared. The same cemented Aequalis third generation humeral component was used in all patients. With a follow-up of 12 years, the study reported revision surgery, pain, function and complications. There was a low risk of bias.

Page (2018) described results from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). All conventional primary TSA procedures with a primary diagnosis of osteoarthritis, reported to the AOANJRR between 2004 and 2016 were included, with the aim of comparing the revision rates of cemented and cementless design glenoid components in TSA. Within the study period, 10,805 primary conventional TSAs were identified, 3,159 with cementless and 7,646 with cemented glenoid fixation. The median age of men in the study was 67, of women it was 71. The follow-up was 10 years. The study had a low risk of bias.

Based on the New Zealand Joint Registry, Sharplin (2020) analysed revision rate in 2,613 patients who underwent conventional primary TSA for osteoarthritis from 2000 to 2017. With a follow-up of 15 years, revision rate was compared between several cementless (N=794) and cemented (N=1819) glenoid components in TSA. In addition, Oxford shoulder score was reported up to five years. Age distribution in the study was 4.5% < 55y, 23% 55 to 65y, 45% 65 to 75y and 28% ≥ 75y. The study had a low risk of bias.

Results

Prosthesis survival (critical outcome)

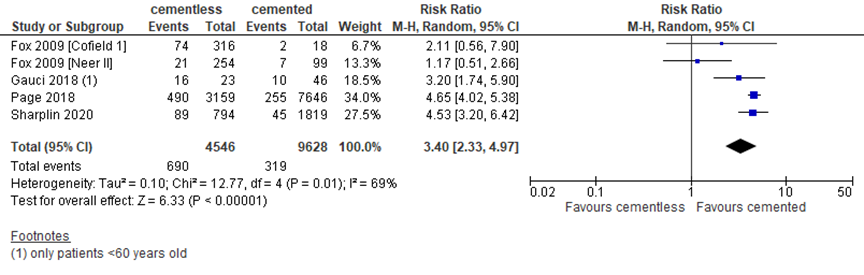

Revision was used to assess the critical outcome prosthesis survival. Four studies reported revision surgery with follow-up of 10 to 15 years, as depicted in figure 1. Revision in studies with a shorter follow-up was not included. All studies found more revision surgery in TSAs with a cementless glenoid component (15%; N=4,546) compared to cemented fixation (3%; N=9,628). The pooled relative risk (RR) was 3.40 in favour of cemented fixation, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from 2.33 to 4.97. This difference is clinically relevant.

Figure 1 Revision surgery for TSA with cementless versus cemented glenoid component

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect. Only studies reporting revision with a follow-up of at least 10 years were included in the analysis

In addition to the revision rate, Page (2018) determined the hazard ratio for the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (N=10,805) and found that cementless glenoids had a higher 10-year revision rate than cemented glenoids (hazard ratio 4.77; 95% CI 4.10 to 5.55). Based on the New Zealand Joint Registry (N=2613), Sharplin (2020) assessed the revisions per 100 component years and found this rate to be 2.03 for uncemented glenoids versus 0.41 for cemented glenoid components. Fox (2009) reported Kaplan-Meier survival per implant type in an American registry study. For Neer II implants, 15-year survival was 94 (95% CI 89 to 100; N=99) for cemented, versus 89 (95% CI 85 to 94; N=254) for uncemented glenoid components. For the Cofield 1 implants, 15-year survival for cemented and uncemented glenoids was 87 (95% CI 71 to 100; N=18) and 67 (95% CI 59 to 76; N=316), respectively.

Pain (critical outcome)

The critical outcome postoperative pain was described in two studies, with different scales and at different follow-up times. The RCT by Boileau (2002) reported the Constant pain subscore (0 to 15, higher is better) at 1 year, and found a mean score of 12 (range 5 to 15; N=20) for cementless fixation versus 12.5 (range 4 to 15; N=20) for cemented fixation. At 3 years, the scores were 13 (range 3 to 15; N=18) for uncemented and 12 (range 0-15; N=17) for cemented fixation. Due to the lack of information regarding the distribution of the data, the confidence interval could not be determined. Therefore, observational studies were also included. Gauci (2018) reported pain with the VAS-score (0 to 10, lower is better) after 10 years. Mean ± SD were 4 ± 3 (n=7) for cementless and 3 ± 3 (n=36) for cemented fixation.

Overall, there was no clinically relevant difference.

Function

Three studies reported the important outcome shoulder function. Sharplin (2020) assessed the Oxford shoulder score (12 to 60, lower is better) at 6 months in the New Zealand Joint Registry and reported mean ± SD of 40.3 ± 7.9 (N=1275) for cementless fixation versus 39.7 ± 7.7 (N=549) for cemented fixation. At 5 years, these values were 42.1 ± 7.5 (N=471) and 42.8 ± 7.0 (N=250), respectively.

Gauci (2018) found a mean ± SD Constant score (0 to 100, higher is better) after 10 years of 64 ± 24 (n=7) for cementless versus 64 ± 17 (n=36) for cemented glenoid fixation in a French cohort study with patients younger than 60.

In the RCT by Boileau (2002) a mean Constant score 73 (range 17 to 89; N=20) was reported 1 year postoperatively in cementless glenoids, versus 66 (range 6 to 89; N=20) in cemented glenoids. At 3 years, the Constant scores were 73 (range 42 to 89; N=18) and 68 (range 6 to 92; N=17), respectively. Standard deviations were not provided in this study. Overall, the differences were not clinically relevant.

Complications

The RCT of Kilian (2018) reported 6/28 (21%) complications after implants with cementless fixation versus 1/26 (4%) with cemented fixation, giving a RR of 5.57 (95% CI 0.72 to 43.22) in favour of cemented fixation. Since the level of evidence for the study was very low (risk of bias, imprecision), observational studies were also included.

Gauci (2018) found 21/23 (91%) complications with cementless fixation versus 13/46 (28%) for cemented glenoid fixation. The most relevant complications glenoid loosening and excessive polyethylene wear occurred in 14/23 (61%) of cases with cementless fixation versus 10/46 (22%) with cemented glenoid fixation. Taken together, the two studies found a clinically relevant higher complication rate with cementless fixation.

Quality of life

The important outcome quality of life was not reported in the selected literature.

Patient satisfaction

The important outcome patient satisfaction was not reported in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes was based on observational data and, therefore, started at low. For the outcomes pain, function and complications, the level of evidence was downgraded to very low due to the limited number of patients included (imprecision). For the outcomes patient satisfaction and quality of life, the level of evidence could not be determined due to the lack of data.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)favourable effects of a cementless glenoid component compared with a cemented glenoid component in total shoulder arthroplasty?

P: patients with total shoulder prosthesis;

I: cementless glenoid component;

C: cemented glenoid component;

O: prosthesis survival, pain, function, quality of life, complications, patient satisfaction.

Relevant outcomes

The guideline development group considered prosthesis survival and pain as critical outcomes for decision making; and function, quality of life, complications and patient satisfaction as important outcomes for decision making.

For each individual outcome, we aimed to obtain the highest level of evidence, either by limiting the analysis to RCTs, or by including large observational datasets. For prosthesis survival, a minimum follow-up of 10 years was considered relevant. The working group did not define the other outcomes listed above but followed the definitions used in the studies.

The working group used the GRADE-standard limit of 25% as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for dichotomous outcomes and 15% of the maximum score for continuous variables (VAS-scales, quality of life scores and function scores).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms up to and including July 21, 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 402 hits. Randomized and non-randomized comparative studies published between 2000 and 2020 that compared cemented and metal-backed cementless glenoid components in total shoulder arthroplasty, and reported clinical outcomes, were selected. Initially, based on title and abstract screening, eleven studies were selected. After reading the full text, six studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and six studies were included.

Results

Two RCTs were identified for the analysis of the literature. Since these studies did not report the critical outcome prosthesis survival with a minimum follow-up of 10 years, four observational studies were also included. For each outcome, inclusion of only the RCTs or all studies was determined separately, to obtain the highest level of evidence. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Boileau P, Avidor C, Krishnan SG, Walch G, Kempf JF, Molé D. Cemented polyethylene versus uncemented metal-backed glenoid components in total shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective, double-blind, randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002 Jul-Aug;11(4):351-9. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.125807. PMID: 12195253.

- Castagna A, Randelli M, Garofalo R, Maradei L, Giardella A, Borroni M. Mid-term results of a metal-backed glenoid component in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Oct;92(10):1410-5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.23578. PMID: 20884980.

- Fox TJ, Cil A, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Survival of the glenoid component in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009 Nov-Dec;18(6):859-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.020. Epub 2009 Mar 17. PMID: 19297199.

- Friedman RJ, Cheung E, Grey SG, Flurin PH, Wright TW, Zuckerman JD, Roche CP. Clinical and radiographic comparison of a hybrid cage glenoid to a cemented polyethylene glenoid in anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019 Dec;28(12):2308-2316. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.04.049. Epub 2019 Jul 16. PMID: 31324502.

- Gauci MO, Bonnevialle N, Moineau G, Baba M, Walch G, Boileau P. Anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty in young patients with osteoarthritis: all-polyethylene versus metal-backed glenoid. Bone Joint J. 2018 Apr 1;100-B(4):485-492. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B4.BJJ-2017-0495.R2. PMID: 29629579; PMCID: PMC6503758.

- Nelson CG, Brolin TJ, Ford MC, Smith RA, Azar FM, Throckmorton TW. Five-year minimum clinical and radiographic outcomes of total shoulder arthroplasty using a hybrid glenoid component with a central porous titanium post. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Aug;27(8):1462-1467. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.01.012. Epub 2018 Mar 8. PMID: 29526600.

- Page RS, Pai V, Eng K, Bain G, Graves S, Lorimer M. Cementless versus cemented glenoid components in conventional total shoulder joint arthroplasty: analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Oct;27(10):1859-1865. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.03.017. Epub 2018 May 8. PMID: 29752154.

- Sharplin PK, Frampton CMA, Hirner M. Cemented versus uncemented glenoid fixation in total shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a New Zealand Joint Registry study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020 Oct;29(10):2097-2103. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.03.008. Epub 2020 Jun 9. PMID: 32564898.

- Wijeratna M, Taylor DM, Lee S, Hoy G, Evans MC. Clinical and Radiographic Results of an All-Polyethylene Pegged Bone-Ingrowth Glenoid Component. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016 Jul 6;98(13):1090-6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00475. PMID: 27385682.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy - otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question: What are the (un)favourable effects of a cementless glenoidcomponent compared with a cemented glenoidcomponent in total shoulder arthroplasty?

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question: What are the (un)favourable effects of a cementless glenoidcomponent compared with a cemented glenoidcomponent in total shoulder arthroplasty?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome accessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Boileau, 2002 |

Group allocation was decided by use of a random table after humeral preparation at the time of glenoid preparation. |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unclear |

likely |

unlikely |

|

Kilian, 2017 |

Randomization was performed using a random numbers table with the glenoid component type sealed in an envelope. |

unlikely |

unlikely |

likely |

unlikely |

unclear

|

likely |

unlikely

|

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (observational: non-randomized clinical trials, cohort and case-control studies)

Research question: What are the (un)favourable effects of a cementless glenoidcomponent compared with a cemented glenoidcomponent in total shoulder arthroplasty?

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Fox, 2009 |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Gauci, 2018 |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Page, 2018 |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

|

Sharplin, 2020 |

unclear |

unlikely |

unlikely |

unlikely |

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Clitherow, 2014 |

Updated by Sharplin, 2020 |

|

Papadonikolakis, 2014 |

SR, no separate data from individual studies reported |

|

Kim, 2020 |

SR, no separate data of comparative studies presented |

|

Wallace, 1999 |

Published before 2000 |

|

Dillon, 2020 |

no comparison of interventions |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 02-11-2021

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 11-10-2021

Algemene gegevens

De herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten die een schouderprothese krijgen.

Werkgroep

- dr. J.J.A.M. van Raaij, orthopedisch chirurg bij Martini Ziekenhuis (voorzitter), NOV

- dr. T.D.W. Alta, orthopedisch chirurg bij Spaarne Gasthuis, NOV

- dr. C.P.J. Visser, orthopedisch chirurg bij Alrijne Ziekenhuis en Eisenhower Kliniek, NOV

- dr. O.A.J. van der Meijden, orthopedisch chirurg bij Albert Schweitzer Ziekenhuis, NOV

- dr. C. Th. Koorevaar, orthopedisch chirurg bij Deventer Ziekenhuis, NOV

- dr. H.J. van der Woude, radioloog bij OLVG, NVvR

- R. Schuurmans, Diagnostisch Fysiotherapeut en MSK echografist bij Flevoziekenhuis en Bergman Clinics Naarden, KNGF

- K.M.C. Hekman, fysiotherapeut en manueel therapeut bij Schoudercentrum IBC Amstelland, KNGF

- drs. G. Willemsen, voorzitter Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland

- N. Lopuhaä, beleidsmedewerker Patiëntbelangen, ReumaNederland

Met ondersteuning van

- dr. M. de Weerd, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot september 2019)

- drs. T. Geltink, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot december 2020)

- dr. M.S. Ruiter, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (vanaf september 2019)

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Van Raaij (voorzitter) |

Orthopedisch chirurg Martini Ziekenhuis Groningen |

Opleider orthopedie Martiniziekenhuis Groningen; secretaris/vice voorzitter ROGO orthopedie Noordoost; voorzitter COC Martiniziekenhuis Groningen; lid regionale COC OOR Noordoost; secretaris concilium orthopedicum, lid RGS orthopedie; bestuurslid werkgroep schouder/elleboog NOV; lid LEARN Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (onderzoeksgroep opleiding/onderwijs); docent Hanzehogeschool Groningen; reviewer diverse orthopedische tijdschriften; beoordelaar/reviewer ingediende projecten ZonMW; lid editorial board Orthopedics (orthopedisch journal); voorzitter stichting ortho research noord (extern gefinancierd door Smith en Nephew en door wetenschapscommissie Martiniziekenhuis Groningen) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Willemsen-de Mey |

Voorzitter Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Lopuhaä |

Beleidsmedewerker Patiëntenbelangen ReumaNederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Visser |

Orthopedisch chirurg Alrijne Ziekenhuis, Leiden |

Reviewer diverse orthopedische tijdschriften; |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van der Meijden |

Orthopedisch chirurg; Albert Schweitzer Ziekenhuis Dordrecht |

Reviewer diverse orthopedische tijdschrijften |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van der Woude |

Radioloog, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (Oost) Amsterdam |

Lid/consulent Nederlandse Commissie voor Beentumoren (onbezoldigd) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Alta |

Orthopedisch chirurg Spaarne Gasthuis (Haarlem/Hoofddorp) |

Congres Commissie Nederlandse Vereniging voor Arthroscopie

Bestuurslid Europese schouder en elleboog society en hoofd Health Care Delivery committeer

Wetenschappelijke commissie wereld schouder en elleboog congres |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Koorevaar |

Orthopedisch chirurg Deventer Ziekenhuis |

Opleider Orthopedie Deventer Ziekenhuis. Reviewer diverse orthopedische tijdschriften. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Schuurmans |

Flevoziekenhuis: Diagnostisch Fysiotherapeut en MSK echografist poli Orthopedie; Bergman Clinics: Diagnostisch Fysiotherapeut en MSK echografist op de schouderpoli van dr. van der List; |

Voorzitter Schouder Netwerk Flevoland (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hekman |

Fysio, -manueeltherapeut; Schoudercentrum IBC Amstelland Advanced clinical practioner; MC Jan van Goyen |

Bestuursvoorzitter Schouder Netwerken Nederland : onbetaald Gastdocent Nederlands Paramedisch Instituut : betaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntperspectief door Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en andere relevante patiëntenorganisaties uit te nodigen voor een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. Het verslag hiervan (zie bijlagen) is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen. Bovendien werd het patiëntperspectief vertegenwoordigd door afvaardiging van patiëntenorganisaties ReumaNederland en Nationale Vereniging ReumaZorg Nederland in de werkgroep. Tot slot werden de modules voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en andere relevante patiëntenorganisaties en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die een schouderprothese krijgen. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door stakeholders door middel van een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

- Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

- Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

- Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

- Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

- Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site.html

- Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Algemene informatie

|

Richtlijn: Schouderprothese |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: Wat is de effectiviteit van een gecementeerd glenoid component in vergelijking met een ongecementeerd glenoidcomponent bij een patiënt met een indicatiestelling voor een totale schouderprothese? |

|

|

Database(s): PubMed, Embase |

Datum: 21-7-2020 |

|

Periode: 1995- |

Talen: niet van toepassing |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Ingeborg van Dusseldorp |

|

|

Toelichting en opmerkingen: Omdat het artikel van Sharplin uit juni 2020 is heeft het nog niet de juiste indexering meegekregen in PubMed. In Embase heeft het de term controlled study gekregen. Deze is toegevoegd aan het zoekblok RCT, waarmee ook dit sleutelartikel is gevonden. |

|

PubMed

|

Search |

Query |

Results |

|

#12 |

Search: #10 NOT #9 NOT #8 |

286 |

|

#11 |

Search: #9 NOT #8 |

19 |

|

#8 |

Search: #4 AND #5 |

18 |

|

#10 |

Search: #4 AND #7 |

310 |

|

#9 |

Search: #4 AND #6 |

23 |

|

#7 |

Search: "Epidemiologic Studies"(Mesh) OR cohort(tiab) OR (case(tiab) AND (control(tiab) OR controll*(tiab) OR comparison(tiab) OR referent(tiab))) OR risk(tiab) OR causation(tiab) OR causal(tiab) OR "odds ratio"(tiab) OR etiol*(tiab) OR aetiol*(tiab) OR "natural history"(tiab) OR predict*(tiab) OR prognos*(tiab) OR outcome(tiab) OR course(tiab) OR retrospect*(tiab) |

6,709,587 |

|

#6 |

Search: ("Randomized Controlled Trial" (Publication Type) OR random*(tiab) OR pragmatic clinical trial*(tiab) OR practical clinical trial*(tiab) OR non-inferiority trial*(tiab) OR noninferiority trial*(tiab) OR superiority trial*(tiab) OR equivalence clinical trial*(tiab)) NOT (("Animals"(Mesh)) OR "Models, Animal"(Mesh) NOT humans(mh)) NOT (letter(pt) OR comment(pt) OR editorial(pt)) |

1,130,145 |

|

#5 |

Search: ("Meta-Analysis" (Publication Type) OR "Meta-Analysis as Topic"(Mesh) OR metaanaly*(tiab) OR meta-analy*(tiab) or metanaly*(tiab) OR "Systematic Review" (Publication Type) OR systematic(sb) OR "Cochrane Database Syst Rev"(Journal) or prisma(tiab) OR preferred reporting items(tiab) OR prospero(tiab) OR ((systemati*(ti) OR scoping(ti) OR umbrella(ti) OR structured literature(ti)) AND (review*(ti) OR overview*(ti))) OR systematic review*(tiab) OR scoping review*(tiab) OR umbrella review*(tiab) OR structured literature review*(tiab) OR systematic qualitative review*(tiab) OR systematic quantitative review*(tiab) OR systematic search and review(tiab) OR systematized review(tiab) OR systematised review(tiab) OR systemic review(tiab) OR systematic literature review*(tiab) OR systematic integrative literature review*(tiab) OR systematically review*(tiab) OR scoping literature review*(tiab) OR systematic critical review(tiab) OR systematic integrative review*(tiab) OR systematic evidence review(tiab) OR Systematic integrative literature review*(tiab) OR Systematic mixed studies review*(tiab) OR Systematized literature review*(tiab) OR Systematic overview*(tiab) OR Systematic narrative review*(tiab) OR ((systemati*(tiab) OR literature(tiab) OR database*(tiab) OR data-base*(tiab) OR structured(tiab) OR comprehensive*(tiab) OR systemic*(tiab)) AND search*(tiab)) OR (Literature(ti) AND review(ti) AND (database*(tiab) OR data-base*(tiab) OR search*(tiab))) OR ((data extraction(tiab) OR data source*(tiab)) AND study selection(tiab)) OR (search strategy(tiab) AND selection criteria(tiab)) OR (data source*(tiab) AND data synthesis(tiab)) OR medline(tiab) OR pubmed(tiab) OR embase(tiab) OR Cochrane(tiab) OR ((critical(ti) OR rapid(ti)) AND (review*(ti) OR overview*(ti) OR synthes*(ti))) OR (((critical*(tiab) OR rapid*(tiab)) AND (review*(tiab) OR overview*(tiab) OR synthes*(tiab)) AND (search*(tiab) OR database*(tiab) OR data-base*(tiab)))) OR metasynthes*(tiab) OR meta-synthes*(tiab)) NOT ("Comment" (Publication Type) OR "Letter" (Publication Type) OR "Editorial" (Publication Type) OR (("Animals"(Mesh) OR "Models, Animal"(Mesh)) NOT "Humans"(Mesh))) |

469,190 |

|

#4 |

Search: #1 AND #2 Filters: from 1995 - 2020 |

477 |

|

#3 |

Search: #1 AND #2 |

501 |

|

#2 |

Search: "Polyethylene"(Mesh) OR cement*(tiab) OR uncement*(tiab) OR "metal back*"(tiab) OR ‘poly-ethylene’(tiab) OR polyethylene(tiab) |

122,401 |

|

#1 |

Search: "Arthroplasty, Replacement, Shoulder"(Mesh) OR ats(tiab) OR "total shoulder"(tiab) |

7,436 |

Embase

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#15 |

#13 NOT #12 NOT #11 |

131 |

|

#14 |

#12 NOT #11 |

161 |

|

#13 |

#7 AND #10 |

189 |

|

#12 |

#7 AND #9 |

163 |

|

#11 |

#7 AND #8 |

12 |

|

#10 |

'major clinical study'/de OR 'clinical study'/de OR 'case control study'/de OR 'family study'/de OR 'longitudinal study'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'cohort analysis'/de OR ((cohort NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('case control' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('follow up' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (observational NEAR/1 (study OR studies)) OR ((epidemiologic NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) OR (('cross sectional' NEAR/1 (study OR studies)):ab,ti) |

5326563 |

|

#9 |

('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR 'prospective study'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti) NOT 'conference abstract':it |

2415707 |

|

#8 |

('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

503630 |

|

#7 |

#6 AND (1-1-1995)/sd NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) NOT (('adolescent'/exp OR 'child'/exp OR adolescent*:ti,ab OR child*:ti,ab OR schoolchild*:ti,ab OR infant*:ti,ab OR girl*:ti,ab OR boy*:ti,ab OR teen:ti,ab OR teens:ti,ab OR teenager*:ti,ab OR youth*:ti,ab OR pediatr*:ti,ab OR paediatr*:ti,ab OR puber*:ti,ab) NOT ('adult'/exp OR 'aged'/exp OR 'middle aged'/exp OR adult*:ti,ab OR man:ti,ab OR men:ti,ab OR woman:ti,ab OR women:ti,ab)) |

479 |

|

#6 |

#4 AND #5 |

564 |

|

#5 |

'polyethylene'/exp OR cement*:ti,ab,kw OR uncement*:ti,ab,kw OR 'metal back*':ti,ab,kw OR 'poly-ethylene':ti,ab,kw OR 'polyethylene':ti,ab,kw |

141738 |

|

#4 |

'total shoulder arthroplasty'/exp OR ats:ti,ab,kw OR 'total shoulder arthroplast*':ti,ab,kw OR 'anatomical total shouder':ti,ab,kw OR 'total shoulder replacement':ti,ab,kw |

11868 |

|

#3 |

20884980 AND castagna |

1 |

|

#2 |

cemented AND polyethylene AND versus AND uncemented AND 'metal backed' AND glenoid AND components AND in AND total AND shoulder AND arthroplasty AND boileau |

1 |

|

#1 |

cemented AND versus AND uncemented AND glenoid AND fixation AND in AND total AND shoulder AND arthroplasty AND for AND osteoarthritis AND sharplin |

1 |