Teamtraining bij schouderdystocie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van teamtraining met betrekking tot het oplossen van een schouderdystocie ter verbetering van de uitkomsten na schouderdystocie?

Aanbeveling

Organiseer teamtrainingen om de vaardigheden, kennis en logistiek rondom een schouderdystocie te optimaliseren en mogelijk neonatale uitkomsten te verbeteren.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is beperkte literatuur beschikbaar over het effect van teamtraining op neonatale en maternale uitkomsten. Er zijn drie pre-poststudies gevonden naar de effecten van teamtraining in het behandelen van schouderdystocie (Dahlberg, 2018; Crofts, 2016; Van de Ven, 2016). Deze studies laten positieve effecten zien van teamtraining op zowel de korte als langetermijn. Gunstige effecten van een teamtraining werden gevonden op het aantal fracturen (clavicula en humerus) en het aantal plexusbrachialuslaesie. Er werd ook één multicenter RCT gevonden (Fransen, 2016). Echter, deze studie rapporteerde neonataal trauma die doorgaans het gevolg is van schouderdystocie maar rapporteerde niet specifiek over schouderdystocie. De belangrijkste bevinding uit deze studie was dat teamtraining mogelijk positieve effecten heeft op het reduceren van het aantal kinderen met een geboortetrauma die doorgaans met name veroorzaakt worden door een schouderdystocie (Fransen, 2016). Ten aanzien van de uitkomstmaat plexusbrachialuslaesie toont de RCT van Fransen (2016) geen verschil aan tussen de groep die wel of geen teamtraining heeft gevolgd. Het is onbekend of de studie van Fransen (2016) voldoende statistische power heeft om een potentieel statistisch verschil tussen de groepen aan te tonen, deze onzekerheid zien we terug in de gradering van de bewijskracht. De resultaten moeten daarom ook voorzichtig worden geïnterpreteerd.

De pre-poststudies vergeleken uitkomsten voor en na implementatie van een trainingsprogramma gericht op schouderdystocie (Dahlberg, 2018; Crofts, 2016; Van de Ven, 2016). De grootste beperking van deze studies was dat er naast de training veel andere factoren een mogelijk effect hebben op de uitkomst. De pre-post observationele studies hebben, inherent aan het studiedesign, een zeer lage bewijskracht. Desondanks zijn er positieve effecten gevonden voor teamtraining op het voorkomen van fracturen en plexusbrachialuslaesie. Met name de subgroep-analyse en de langetermijneffecten na de training laten positieve effecten van een teamtraining zien. Het positieve effect kan ook worden veroorzaakt door een toename in het aantal kinderen dat werd gediagnosticeerd met een ‘eenvoudigoplosbareschouderdystocie’, wat mogelijk verklaard kan worden door een toename in algehele alertheid op geboortecomplicaties. De resultaten berusten op observationeel onderzoek en hebben een zeer lage bewijskracht waardoor de resultaten kritisch moeten worden beschouwd.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Het is aannemelijk dat een multidisciplinaire teamtraining bijdraagt aan reductie van het aantal complicaties. Echter, het is onduidelijk of teamtrainingen ook effect heeft op het opheffen van een schouderdystocie of de uitkomsten na een schouderdystocie. Hoewel niet primair meegenomen, blijkt uit de meer subjectieve resultaten uit het onderzoek van Dahlberg (2018) dat teamtraining voor meer zekerheid en vertrouwen kan zorgen bij de zorgprofessionals. Zo geeft het merendeel (48 tot 62%) aan meer vertrouwen te hebben in de dagelijkse praktijk na het volgen van een teamtraining (Dahlberg, 2018). Door middel van teamtrainingen zullen medische kennis, vaardigheden en zelfvertrouwen van alle betrokken zorgverleners met betrekking tot het oplossen van zeldzaam voorkomende complicaties, zoals schouderdystocie, verbeteren. Het is te verwachten dat dit bijdraagt aan betere uitkomsten voor moeder en kind.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De implementatie van teamtrainingen brengt extra kosten met zich mee. Zorgprofessionals doen de training in werktijd en trainers moeten worden opgeleid. Obstetrische teams kunnen getraind worden in simulatiecentra. Ook kan een systeem van regelmatige trainingen met eigen trainers lokaal worden opgezet.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep verwacht mogelijk implementatieproblemen wanneer teamtrainingen uitsluitend worden ingezet om de gevolgen van schouderdystocie te reduceren omdat een positief effect op neonatale morbiditeit en mortaliteit niet duidelijk is aangetoond en de incidentie van deze complicaties laag is. Een mogelijke barrière valt te verwachten rondom de beschikbaarheid van goed getraind personeel om een goede teamtraining te verzorgen. De werkgroep acht het echter haalbaar om in elke kliniek een vorm van teamtraining te organiseren. Hoewel dit advies berust op expertopinie, wordt het in teamverband oefenen van acute situaties in een simulatiesetting, door obstetrische zorgverleners gewaardeerd.

Rationale van de aanbeveling

Teamtrainingen worden opgezet om kennis en vaardigheden van relatief weinig voorkomende acute obstetrische situaties te vergroten. Er is weinig onderzoek gedaan naar de effectiviteit van dergelijke trainingen bij schouderdystocie. De gevonden studies laten wel gunstige effecten zien van teamtrainingen op het aantal fracturen (clavicula en humerus) en plexusbrachialuslaesies. De teamtraining kan mogelijk ook bijdragen aan de tevredenheid en het zelfvertrouwen van de zorgprofessional. Daarnaast kunnen teamtrainingen de logistiek rondom een spoedsituatie zoals schouderdystocie verbeteren, waarbij de organisatie en een procesmatige aanpak het medisch handelen optimaliseert. Teamtraining heeft mogelijk een gunstig effect op de neonatale morbiditeit na schouderdystocie, hoewel met lage bewijskracht. Ook dragen teamtrainingen mogelijk bij aan het verbeteren van teamperformance en kunnen zij daardoor gunstige effecten hebben op maternale en neonatale uitkomsten.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Van een schouderdystocie wordt gesproken als de zorgprofessional tijdens de uitdrijving van een kind in hoofdligging extra handgrepen moet toepassen om de schouders van het kind geboren te laten worden. Schouderdystocie ontstaat als de voorste, of zeldzamer, de achterste schouder van het kind haakt respectievelijk op de maternale symfyse of het sacrale promontorium en het vast komt te zitten. Er wordt grote variatie gerapporteerd in incidentie van schouderdystocie (Crofts, 2016; Dahlber, 2018; van de Ven, 2015). Als een schouderdystocie optreedt wordt er een verhoogde maternale en neonatale morbiditeit en mortaliteit gezien, ook al wordt deze correct opgelost. Voorbeelden hiervan zijn fluxus post partum en derde- en vierdegraadsperineumrupturen (OASIS: Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injuries). Een plexusbrachialuslaesie bij het kind is de meest belangrijke foetale complicatie. Schouderdystocie is slecht voorspelbaar.

De vraag is of structurele teamtrainingen met betrekking tot het snel en goed oplossen van een schouderdystocie de uitkomsten voor moeder en kind verbeteren.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Teamtraining in shoulder dystocia

|

Very Low GRADE |

Teamtraining may reduce the number of children with clavicle or humeral fractures following shoulder dystocia but the evidence is very uncertain.

Bronnen: (Dahlberg, 2018; Crofts, 2016; Van de Ven, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Teamtraining may reduce the number of children with brachial plexus injury following shoulder dystocia but the evidence is very uncertain.

Bronnen: (Dahlberg, 2018; Crofts, 2016; Van de Ven, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Teamtraining may have little to no effect on the number of children with neonatal apgarscore < 7 at 5 minutes following shoulder dystocia but the evidence is very uncertain.

Bronnen: (Crofts, 2016; Dahlberg, 2018) |

Teamtraining in obstetric units

|

Very low GRADE |

Teamtraining may reduce the number of children with neonatal trauma (likely due to shoulderdystocia) compared to no teamtraining but the evidence is very uncertain.

Bronnen: (Fransen, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Teamtraining may reduce the number of children with clavicle or humeral fractures (likely due to shoulderdystocia) compared to no teamtraining but the evidence is very uncertain.

Bronnen: (Fransen, 2016) |

|

Very low GRADE |

Teamtraining may have little to no effect on the number of children with brachial plexus injuries (likely due to shoulderdystocia) compared to no teamtraining but the evidence is very uncertain.

Bronnen: (Fransen, 2016) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Three studies described a retrospective before-after study design (Crofts, 2016; Dahlberg, 2018; van de Ven, 2016). These studies evaluated the effects of teamtraining in shoulder dystocia. Another study described a multicentre cluster randomized controlled trial (Fransen, 2017) and evaluated the effects of teamtraining on patient outcomes in multiprofessional obstetric care teams in the Netherlands. This study did not specifically analyse the effects of teamtraining in shoulder dystocia.

Crofts (2016) evaluated the outcomes of incidences of shoulder dystocia in the 12 year after introduction of an obstetric emergencies training program. A multi-professional 1-day intrapartum emergencies training course was given in 1 hospital in Bristol (UK) in 2000. All midwifery and obstetric medical staff had to attend annually. Each session was facilitated by a midwife and/or an obstetrician and attended by a multi-professional team of five to eight members of staff. The training day included a 30-minute practical session on shoulder dystocia management using the PROMPT Birthing Trainer. Data concerning neonatal morbidity and documented management of shoulder dystocia were collected before training was given between 1996 and 1999, early training implementation (2001 and 2004) and late training implementation (2009 and 2012) and compared between the pre-training and the two post-training periods. Data was analysed in women with shoulder dystocia.

Dahlberg (2018) evaluated the impact of 10 years of simulation-based shoulder dystocia training on clinical outcomes. A simulation-based team-training program (PROBE) was introduced at a delivery unit in Linköping (Sweden) in 2008. The objectives of the training were to improve obstetric emergency skills and develop interprofessional teamwork, thus promoting better patient outcome. Participation in PROBE was mandatory for obstetricians, midwives and nurse assistants who worked at the delivery ward. Participants were scheduled during working hours for simulation exercises at an interval of 1.5 years. PROBE included a 40-min shoulder dystocia scenario. Data concerning obstetric and neonatal clinical outcomes were collected before PROBE was introduced between 2004 and 2007, early postPROBE (2008 and 2011) and late postPROBE (2012 and 2015). Data was analysed in women with shoulder dystocia.

Van de Ven (2016) evaluated the effectiveness of simulation teamtraining on the number of fatal complications caused by shoulder dystocia, being perinatal asphyxia and neonatal trauma, combined as fatal injury. A simulation-based teamtraining was implemented in 1 teaching hospital in the Netherlands in 2005. The teamtraining comprised on average of two scenarios of acute obstetric emergencies per session, including shoulder dystocia, using the Prompt Birthing Trainer. All physicians, clinical midwives and nurses who worked on the delivery ward were scheduled during working time to attend these training sessions. Data were collected before training was given between November 2001 to December 2004, and an equal period from January 2007 to February 2010 after all care workers had been trained. Data could be analysed at cohort level, but also in women with shoulder dystocia.

Fransen (2017) performed a multicentre cluster RCT (TOSTI study) in the Netherlands investigating whether a 1-day simulation-based obstetric teamtraining improves patient outcome compared to no training during 1-year follow-up. The effects of teamtraining were evaluated at the cluster level and could not be analysed solely in women with shoulder dystocia. A total of 24 hospitals were randomized to the intervention (N=12) or control group (N=12). Units in the intervention group received a 1-day (8-hour), simulation based, multi-professional obstetric teamtraining, focusing on crew resource management CRM skills in a medical simulation centre. The entire multi-professional staff of the obstetric units of the intervention group were obliged to participate. They were divided into several multi-professional obstetric teams consisting of a gynaecologist/obstetrician, a clinical midwife and/or a resident, and nurses. In the intervention group, 74 multi-professional teams, comprising 471 healthcare professionals, received the training (74 gynaecologists/ obstetricians, 36 residents, 79 secondary care midwives and 282 nurses). Units in the control group did not receive any training. Primary outcome was a composite outcome of the number of obstetric complications, i.e. low apgarscore, severe postpartum haemorrhage, trauma due to shoulder dystocia (brachial plexus injury, clavicle fracture, humeral fracture or other injuries for example other fractures, pneumothorax, hypoxia/acidosis, HIE or mortality), eclampsia and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE). Secondary outcomes were perinatal and maternal mortality. Perinatal mortality was defined as fatal or neonatal mortality beyond 24 weeks of gestation and within 7 days postpartum. Maternal mortality was defined as the death of a woman during or within 6 weeks after pregnancy. All outcomes were collected for the pre- and post-intervention period, both of which lasted for 1 year.

Results

Clavicle or humeral fractures in shoulder dystocia

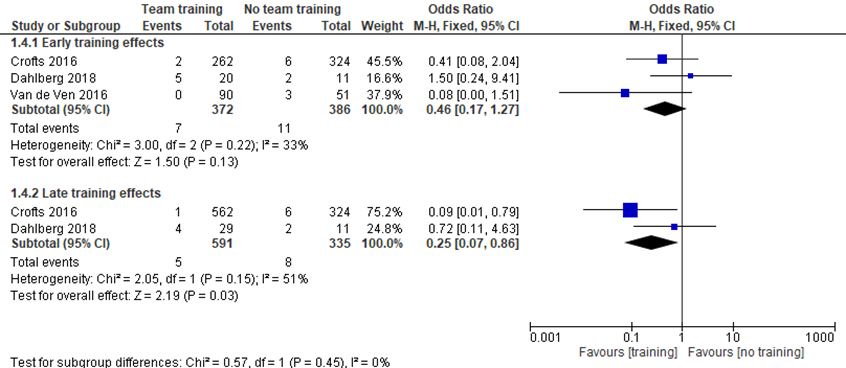

Crofts (2016) reported cases of shoulder dystocia in the pre-training (324/15.908, 2.0%), early training (262/13.117, 2.0%) and late training period (562/17.037, 3.3%). The number of fractured clavicle or humerus per case of shoulder dystocia between the pre-traning period (6/324; 1996 to 1999) was compared to the early post-traning period (2/262; 2001-2004) and the late post-training period (1/562; 2009 to 2012). Calculating the OR, there was no significant difference in OR for shoulder dystocia related clavicle or humerus fractures between the pre-training period and the early post-training period (OR 1.50; 95% CI 0.24 to 9.41), but there was a significant OR for the late post-training period (OR 0.09; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.79).

Dahlberg (2018) reported cases of shoulder dystocia in the prePROBE (11/11.064, 0.01%), early postPROBE (20/11.122, 0.18%) and late postPROBE period (29/11.667, 0.25%). The number of clavicular and humerus fractures in women with shoulder dystocia between the prePROBE training period (2/11; 2004 to 2007) was compared to the early postPROBE (5/20; 2008 to 2011) and late postPROBE period (4/29; 2012-2015). Calculating the OR for both periods, there were no significant differences in OR for clavicular and humerus fractures between the pre- and early postPROBE (OR 1.50; 95% CI 0.24 to 9.41) and the pre- and late postPROBE period (OR 0.72; 95% CI 0.11 to 4.63).

Van de Ven (2016) reported cases of shoulder dystocia before training (51/3.492, 1.46%) and after training (90/3.496, 2.57%). They analysed the difference in the number of fractures in women with shoulder dystocia between the period before training (3/51) compared to the period after traning (0/90). Calculating the OR, there was no significant difference in OR for fractures before and after the trainingperiod (OR 0.20; 95% CI 0.01 to 4.16).

Overall training effects

Meta-analyses showed that the difference in the number of clavicular and humerus fractures was not significant between the pre- and early trainingperiod (OR 0.46; 95% CI 0.17 to 1.27), but the number of these fractures differed significantly between the pre- and late trainingperiod (OR 0.25; 95%CI 0.07 to 0.86), favouring training.

Figure 1 Teamtraining versus no teamtraining (early and late effects): clavicle or humeral fractures in infants with shoulder dystocia

Brachial plexus injury in shoulder dystocia

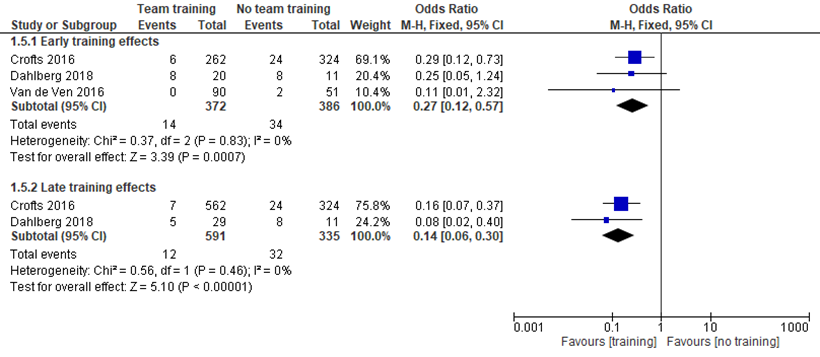

Crofts (2016) reported the number of brachial plexus injuries per case of shoulder dystocia between the pre-traning period (24/324; 1996 to 1999) compared to the early post-training period (6/262; 2001 to 2004) and the late post-training period (7/562; 2009 to 2012). Calculating the OR, there were significant ORs for shoulder dystocia related brachial plexus injury between the pre-training period and the early post-training period (OR 0.29; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.73), and late post-training period (OR 0.16; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.37).

Dahlberg (2018) reported the number of brachial plexus injuries in woment with shoulder dystocia between the prePROBE training period (8/11; 2004 to 2007) compared to the early postPROBE period (8/20; 2008 to 2011) and late postPROBE period (5/29; 2012 to 2015). Calculating the ORs for both periods, there was no significant OR for brachial plexus injuries between the pre- and early postPROBE period (OR 0.25; 95% CI 0.05 to 1.24), but a significant OR between the pre- and late postPROBE period (OR 0.08; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.40).

Van de Ven (2016) analysed the difference in number of brachial plexus injuries between the period before training (3/51) compared to the period after traning (0/90). Brachial plexus injuries were calculated in women with shoulderdystocia. Calculating the OR, there was no significant OR for fractures before and after the trainingperiod (OR 0.20; 95% CI 0.01 to 4.16).

Overall training effects

Meta-analyses showed that the difference in the number of brachial plexus injuries was significant between the pre- and early trainingperiod (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.57) and between the pre- and late trainingperiod (OR 0.14; 95%CI 0.06 to 0.30), favouring training.

Figure 2 Teamtraining versus no teamtraining (early and late effects): brachialis plexus injury in infants with shoulder dystocia

Apgarscore < 7 at 5 minutes in shoulder dystocia

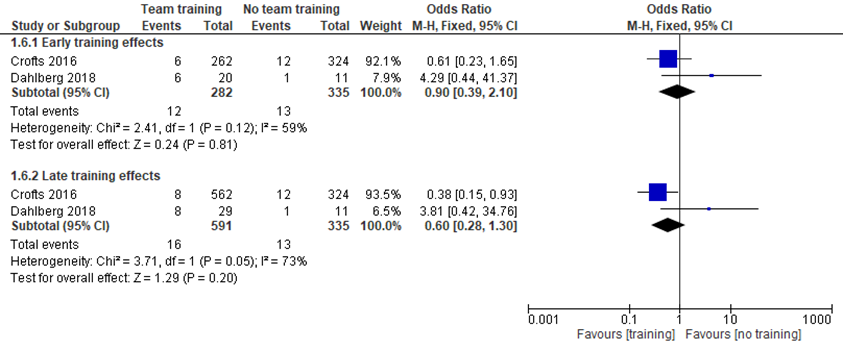

Crofts (2016) reported the number of infants with apgarscore < 7 per case of shoulder dystocia between the pre-traning period (12/324; 1996 to 1999) compared to the early post-traning period (6/262; 2001 to 2004) and the late post-training period (8/562; 2009 to 2012). Calculating the OR, there were no significant ORs between the pre-training period and the early post-training period (OR 0.61; 95% CI 0.23 to 1.65), and late post-training period (OR 4.29; 95% CI 0.44 to 41.37).

Dahlberg (2018) reported the number of infants with apgarscore < 7 in children with shoulder dystocia between the prePROBE training period (1/11; 2004 to 2007) compared to the early postPROBE period (6/20; 2008 to 2011) and late postPROBE period (8/29; 2012 to 2015). Calculating the ORs for both periods, there were no significant ORs between the pre- and early postPROBE period (OR 0.38; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.93) and the pre- and late postPROBE period (OR 3.81; 95% CI 0.42 to 34.76).

Overall trainingeffects

Meta-analyses showed that the difference in the number of infants with Apgar-score < 7 was not significant between the pre- and early trainingperiod (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.39 to 2.10) and also not significant between the pre- and late trainingperiod (OR 0.60; 95%CI 0.28 to 1.30).

Figure 3 Teamtraining versus no teamtraining (early and late effects): Apgarscore < 7 at 5 minutes in children with shoulder dystocia

Neonatal trauma in women giving birth in obstetric units

Fransen (2016) studied 14.500 births in the intervention group and 14.157 in the control group. They reported on composite trauma that is likely due to shoulder dystocia, including brachial plexus injury, clavicle fracture, humeral fracture or other injuries (for example other fractures, pneumothorax, hypoxia/acidosis, hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) or mortality) in women giving birth in obstetric units in the Netherlands. They did not report the number of shoulder dystocia in their study, only trauma that was likely due to shoulder dystocia. A statistically significant difference in the number of neonates with trauma in the intervention group was reported, using a random intercept per hospital (OR 0.50; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.99). The percentage neonates with trauma in the pre-intervention period was 0.31% (43/13971) in the intervention group and 0.19% (26/13538) in de control group. The percentage neonates with trauma in the post-intervention period was 0.16% (23/14500) in the intervention group and 0.25% (35/14157) in de control group. The difference in morbidity (likely due to shoulder dystocia) was mainly driven by a lower number of clavicle fractures in the intervention group compared to the control group (0.09% versus 0.18%: OR 0.38; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.93).

Clavicle or humeral fractures in women giving birth in obstetric units

Fransen (2016) reported the difference in number of clavicular and humerus fractures between the intervention and control group. Fractures could not be analysed separately in women with shoulder dystocia. The percentage neonates with clavicle or humeral fractures in the pre-intervention period was 0.21% (30/13971) in the intervention group and 0.14% (19/13538) in de control group. The percentage neonates with clavicle or humeral fractures in the post-intervention period was 0.16% (23/14500) in the intervention group and 0.25% (35/14157) in de control group. There was a significant difference in OR for clavicular and humerus fractures between the control and intervention group (OR 2.49; 95% CI 0.48 to 12.82), favouring the interventiongroup.

Brachial plexus injury in women giving birth in obstetric units

Fransen (2016) reported number of brachial plexus injury. The number of brachial plexus injuries could not be analysed in women with shoulder dystocia. The percentage neonates with brachial plexus injury in the pre-intervention period was 0.09% (13/13971) in the intervention group and 0.07% (9/13538) in de control group. The percentage neonates with brachial plexus injury in the post-intervention period was 0.04% (6/14500) in the intervention group and 0.08% (12/14157) in de control group. No significant difference in the number of brachial plexus injuries was reported (OR 1.40; 95% CI 0.48 to 4.09).

Level of evidence of the literature

Teamtraining in shoulder dystocia

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures clavicle or humeral fractures, brachial plexus injury and 5-minute apgarscore < 7 was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors in before-after design), the confidence interval crossed the default clinical decision threshold (imprecision) and minimal or no overlap of confidence intervals (inconsistency of results). The levels of evidence is ’very low’.

Teamtraining in women giving birth in obstetric units

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure trauma, clavicle or humeral fractures, brachial plexus injury due to shoulder dystocia in women giving birth in obstetric units was based on a RCT and starts at ‘high’-GRADE and was downgraded by two level, because of study limitations (risk of bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors) and imprecision (only one single study). The level of evidence is ‘very low’.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

PICO

What are the benefits and/or harms of teamtraining to solve shoulder dystocia and to prevent morbidity after shoulder dystocia and improve neonatal and maternal outcomes?

P: patients women giving birth to children with suspected shoulder dystocia;

I: intervention teamtraining;

C: control no teamtraining;

O: outcome neonatal outcomes: brachial plexus injury, neonatal mortality, early neurodevelopmental morbidity, apgarscore, pH in cord blood, birth trauma, NICU admission, death, disability in childhood.

maternal outcomes: harm to mother from intervention, maternal mortality, longer-term maternal outcomes (at three months), emergency caesarean section, postpartum haemorrhage (TBL>1000ml), bloodtransfusion, thromboembolism, urinary retention requiring bladder catheter > 24 hours longer as local protocol prescribes, OASIS (Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injuries), breastfeeding failure, perineal pain, any pain, dyspareunia, urinary incontinence, flatus incontinence, faecal incontinence.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered shoulder dystocia (severe), offspring and maternal mortality, brachial plexus injury and humerus or clavicle fractures as critical outcome measures for decision making; and Apgar-score < 7, NICU admissions, disability in childhood, neurodevelopmental morbidity, as important outcome for decision making.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until July 17th, 2019. The literature search was updated at 2020-11-30. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search produced 188 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: the study population had to meet the criteria as defined in the PICO, intervention as defined in the PICO, original research or systematic review. Seventeen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, thirteen studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and four included. Four studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Crofts JF, Lenguerrand E, Bentham GL, Tawfik S, Claireaux HA, Odd D, Fox R, Draycott TJ. Prevention of brachial plexus injury-12 years of shoulder dystocia training: an interrupted time-series study. BJOG. 2016 Jan;123(1):111-8. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13302. Epub 2015 Feb 17. PubMed PMID: 25688719.

- Dahlberg J, Nelson M, Dahlgren MA, Blomberg M. Ten years of simulation-based shoulder dystocia training- impact on obstetric outcome, clinical management, staff confidence, and the pedagogical practice - a time series study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):361. Published 2018 Sep 5. doi:10.1186/s12884-018-2001-0.

- Fransen AF, van de Ven J, Schuit E, van Tetering A, Mol BW, Oei SG. Simulation-based teamtraining for multi-professional obstetric care teams to improve patient outcome: a multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2017 Mar;124(4):641-650. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14369. Epub 2016 Oct 10. PubMed PMID: 27726304.

- Gonzalves A, Verhaeghe C, Bouet PE, Gillard P, Descamps P, Legendre G. Effect of the use of a video tutorial in addition to simulation in learning the maneuvers for shoulder dystocia. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2018 Apr;47(4):151-155. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2018.01.004. Epub 2018 Jan 31. PubMed PMID: 29391292.

- van de Ven J, van Deursen FJ, van Runnard Heimel PJ, Mol BW, Oei SG. Effectiveness of teamtraining in managing shoulder dystocia: a retrospective study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(19):3167-3171. doi:10.3109/14767058.2015.1118037.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy - otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question:

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors ((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question:

|

Study reference

|

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Fransen, 2017 |

Random allocation of obstetric units in a 1:1 ratio by an independent researcher using a computer-generated list. Randomisation was stratified for units being situated in teaching or nonteaching hospitals, |

Unlikely |

Unlikely, blinding not possible due to the design of the study. |

Unlikely, blinding not possible due to the design of the study. |

Unlikely, data collected by local assessors verified by data from Perined. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (observational: non-randomized clinical trials, cohort and case-control studies)

Research question:

|

Study reference

(first author, year of publication) |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Dahlberg, 2018 |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely, no adjustments for prognostic factors/ confounders were made |

|

Crofts, 2016 |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely, no adjustments for prognostic factors/ confounders were made |

|

Van de Ven, 2016 |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely, no adjustments for prognostic factors/ confounders were made |

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- 2 Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Ameh, 2019 |

Wrong intervention: not specific shoulder dystocia |

|

Crofts, 2006 |

Wrong comparison: Low-Fidelity versus High-Fidelity mannequins |

|

Daniels, 2010 |

Before - after study, no randomization (12-year interval shoulder dystocia teamtraining in UK) |

|

Deering, 2004 |

Before - after study, no randomization (10-year interval shoulder dystocia teamtraining in Sweden) |

|

Draycott, 2008 |

Wrong intervention: simulation versus didactive teamtraining |

|

Fransen, 2013 |

Wrong outcome: performance of caregiver (no patient outcomes measured) |

|

Fransen, 2012 |

Before - after study, no randomization (same study as Crofts 2016: 5-year follow-up results) |

|

Kordi, 2017 |

Same study as Fransen, 2012 |

|

Mannella, 2016 |

Wrong outcome: team performance and medical technical skills |

|

Raynal, 2016 |

not specific shoulder dystocia |

|

Sorensen, 2009 |

Wrong comparison: oral versus simulation training, wrong outcome: performance caregiver |

|

van de Ven, 2009 |

Wrong outcome: performance of caregiver (no patient outcomes measured) |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 10-10-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid :

|

Module[1] |

Regiehouder(s)[2] |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn[3] |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit[4] |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit[5] |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling[6] |

|

Teamtraining bij schouderdystocie |

NVOG |

2020 |

2025 |

Elke 5 jaar |

NVOG |

Nieuwe literatuur |

[1] Naam van de module

[2] Regiehouder van de module (deze kan verschillen per module en kan ook verdeeld zijn over meerdere regiehouders)

[3] Maximaal na vijf jaar

[4] (half)Jaarlijks, eens in twee jaar, eens in vijf jaar

[5] regievoerende vereniging, gedeelde regievoerende verenigingen, of (multidisciplinaire) werkgroep die in stand blijft

[6] Lopend onderzoek, wijzigingen in vergoeding/organisatie, beschikbaarheid nieuwe middelen

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Deze richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen met een kind met een dreigende schouderdystocie.

Werkgroep

- Dr. C.J. (Caroline) Bax, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVOG, (voorzitter, vanaf januari 2020)

- Dr. A.C.C. (Annemiek) Evers, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, NVOG (voorzitter, tot december 2019)

- Drs. A. (Ayten) Elvan-Taspinar, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, Groningen, NVOG

- Dr. F. (Frédérique) van Dunné, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Medisch Centrum Haaglanden, Den Haag, NVOG

- Drs. A.J.M. (Anjoke) Huisjes, gynaecoloog-perinatoloog, werkzaam in de Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn en omgeving, NVOG

- Dr. H.J.H.M. (Thierry) van Dessel, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Elisabeth- TweeSteden Ziekenhuis, Tilburg, NVOG

- J. (Julia) Bloeming, eerstelijns verloskundige , werkzaam in Verloskundigepraktijk Vechtdal in Hardenberg, KNOV

- MSc J.C. (Anne) Mooij, adviseur, Patientenfederatie Nederland

- Dr. S.V. (Steven) Koenen, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het ETZ, locatie Elisabeth Ziekenhuis, NVOG, lid stuurgroep

- Dr. Duvekot, gynaecoloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC, NVOG, lid stuurgroep

Meelezer

- Leden van de Otterlo- werkgroep (2019)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. W.J. (Wouter) Harmsen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. L. (Laura) Viester, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde belangen |

Actie |

|

Evers* |

Gynaecoloog, UMCU |

"Lid van Ciekwal, voorzitter 50 geboortemodules NVOG Werkgroep multidisciplinaire richtlijn extreme vroeggeboorte, NVOG" |

Geen |

Geen actie. |

|

Elvan-Taspinar

|

Gynaecoloog UMCG, Groningen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie. |

|

van Dunné

|

Gynaecoloog Medisch Centrum Haaglanden, Den Haag |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie. |

|

Huisjes

|

Gynaecoloog Gelre Ziekenhuizen |

"Onderwijs coördinator Gelre ziekenhuizen (betaald) Voorzitter Stichting M.O.E.T. (onbetaald) Lid DB Stichting A.L.S.G. (onbetaald) Expertise-werkzaamheden (betaald) Klachtencommissie Gelre ziekenhuizen (betaald) Docent Opleiding tot Klinisch Verloskundige (Universiteit Utrecht) (betaald)" |

Geen |

Geen actie. |

|

Van Dessel

|

Gynaecoloog, Elisabeth- TweeSteden Ziekenhuis, Tilburg

|

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie. |

|

Bloeming |

"Klinisch verloskundige praktijk Vechtdal in Hardenberg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie. |

|

Mooij |

Adviseur Patientenbelang, Patientenfederatie Nederland |

Niet van toepassing |

Geen |

Geen actie. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van patiëntvertegenwoordigers van verschillende patiëntverenigingen voor de Invitational conference en afvaardiging van patiëntenverenigingen in de clusterwerkgroep. Het verslag hiervan is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie per module ook ‘Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)’. De conceptrichtlijn wordt tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan de betrokken patiëntenverenigingen (Vereniging van Ouders van Couveusekinderen (VOC) en Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis).

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de werkgroep de knelpunten rondom de zorg voor zwangere vrouwen met een kind met een dreigende schouderdystocie. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door patiëntenverenigingen tijdens de Invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen in de bijlagen.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule wordt aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Kunz R, Craig J, Montori VM, Bossuyt P, Guyatt GH; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008 May 17;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008 May 24;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139.

Schünemann, A Holger J (corrected to Schünemann, Holger J). PubMed PMID: 18483053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2386626.

Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016 Oct;104(4):320-324. PubMed PMID: 27822157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5079497.

Zoekverantwoording

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

|

Medline (OVID)

2000 – juli 2019

|

1 (shoulder adj3 dystocia*).ti,ab,kw. or exp Brachial Plexus Neuropathies/ or (obstetric* adj3 brachial plexus).ti,ab,kw. or obpp.ti,ab,kw. or exp Asphyxia/ or asphyxia.ti,ab,kw. (20109) 2 exp Simulation Training/ or simulation.ti,ab,kw. or (team and (train* or skill*)).ti,ab,kw. (200959) 3 1 and 2 (154) 4 limit 3 to (english language and yr="2000- 2019") (136)

= 136

|

188 |

|

Embase (Elsevier) |

('shoulder dystocia'/exp OR ((shoulder NEAR/3 dystocia*):ti,ab) OR 'obstetric brachial plexus palsy'/exp OR 'obstetrical brachial plexus palsy'/exp OR ((obstetric* NEAR/3 'brachial plexus'):ti,ab) OR obpp:ti,ab OR 'brachial plexus neuropathy'/exp OR 'asphyxia'/exp OR asphyxia:ti,ab) AND ('simulation training'/exp OR 'simulation based training'/exp OR simulation:ti,ab OR (team:ti,ab AND (train*:ti,ab OR skill*:ti,ab))) AND (2000-2019)/py AND (english)/lim NOT 'conference abstract':it

= 162 |