Monitoren progressie van leverfibrose

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is het optimale monitoringsinterval op fibroseprogressie voor volwassenen met MASLD zonder cirrose, dat wil zeggen fibrosestadium F0 t/m F3?

Aanbeveling

Monitor patiënten met MASLD en fibrosegraad 0-3 elke 3-5 jaar op progressie van leverfibrose op non-invasieve wijze. Overweeg bij patiënten met een verhoogd risico op fibroseprogressie zoals patiënten met bewezen MASH, patiënten met diabetes mellitus type 2 en bij patiënten met een ernstig fibrosestadium (F3) een korter interval.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de literatuur kunnen er geen uitspraken gedaan worden over het beste interval voor monitoring op fibrose bij volwassenen met MASLD (F0-F3). Er zijn namelijk geen studies beschikbaar die de effectiviteit van verschillende monitoringsintervallen met elkaar vergelijken. Informatie over de snelheid van fibroseprogressie biedt geen direct bewijs, maar kan wel behulpzaam zijn bij het vaststellen van een monitoringsinterval. Uit de beschreven resultaten blijkt dat de snelheid van fibroseprogressie sterk varieert tussen de studies. Ook varieert dit naar het stadium van MASLD, bijvoorbeeld NAFL (is geïsoleerde steatose) versus MASH, en andere specifieke kenmerken zoals de aanwezigheid van lobulaire inflammatie in het leverbiopt en van het fibrosestadium. Bij de interpretatie van de data is het belangrijk om hier rekening mee te houden.

Zoals dat ook geldt voor bijvoorbeeld de surveillance op hepatocellulair carcinoom (HCC) is het relevant om naast de leeftijd ook de klinische conditie van de patiënt in de afweging voor het opstellen van een passend monitoringsinterval te betrekken. Zo zal bij de 35-jarige patiënt met MASH en F3-fibrose een korter interval passend zijn dan voor de 60-jarige patiënt met NAFL en F0-fibrose. Bij de afweging van de nadelen van een gemiste progressie naar cirrose tegen de voordelen van een minder frequente monitoring, om zo de optimale lengte van het monitoringsinterval te bepalen, spelen naast medisch-inhoudelijke ook ethische, financiële en maatschappelijke factoren een rol.

Omdat er op basis van de literatuur geen conclusie getrokken kan worden over het beste monitoringsinterval, heeft de werkgroep ook gekeken naar adviezen van andere (inter)nationale richtlijnen over dit onderwerp. Hoewel patiënten met MASH vaker fibrose ontwikkelen dan patiënten met NAFL wordt in de literatuur geen onderscheid gemaakt in het monitoringsadvies. Zowel de Italiaanse, Belgische en EASL-richtlijn adviseren een interval van 1-3 jaar (Marchesini, 2022; Francque, 2018; EASL, 2021). Hierbij wordt bij voorkeur gebruik gemaakt van non-invasieve meetmethoden en combinaties hiervan, zoals FIB-4 test, Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF)-test en transiënte elastografie. Er is momenteel onvoldoende informatie beschikbaar om adviezen te kunnen geven over hoe om te gaan met patiënten die na een aantal keren monitoring geen progressie laten zien. De verwachting is dat hierover in de komende jaren meer bekend zal worden.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het belang van patiënten is het voorkomen van cirrose, HCC en bijkomende complicaties van portale hypertensie, zoals ascites en slokdarmvarices. Zij zijn gebaat bij een effectief en toegankelijk monitoringsprogramma voor de mate van MASLD-gerelateerde fibrose. Zij willen hierover goede voorlichting en hebben soms aanmoediging nodig om bijvoorbeeld verandering van leefstijl vol te houden. De evaluatie kost meestal weinig tijd en moeite. De vervoerskosten en inkomensderving zijn voor de rekening van de patiënt. Derhalve zou het de beste optie zijn als de periodieke evaluatie van MASLD kan worden opgenomen in bestaande programma’s zoals voor cardiovasculair risicomanagement (CVRM) en DM2.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het implementeren van een periodieke evaluatie op de aanwezigheid van fibrose bij mensen met MASLD zal het aantal patiënten met ‘de novo’ complicaties van cirrose door MASLD mogelijk doen verminderen en daarmee de kosten van de Nederlandse leverzorg. De periodieke evaluatie bestaat uit beperkt standaard bloedonderzoek en/of transiënte elastografie. Vanwege het frequente voorkomen van MASLD in de algemene bevolking kan dit een toename aan kosten met zich meebrengen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De hoofdbehandelaar van de patiënt met MASLD is verantwoordelijk voor de organisatie van monitoring van MASLD-gerelateerde fibrose. Voor het merendeel van de patiënten met MASLD is dat de huisarts(praktijk), hoewel patiënten met MASLD ook in de tweede lijn bij de MDL-arts, internist en cardioloog gezien worden. Voor adequate implementatie van deze module is het belangrijk dat zowel huisartsen als medisch specialisten in de tweede lijn zich bewust zijn van toenemende voorkomen en de toenemende ernst van MASLD, de risico’s op de lange termijn en de wijze waarop deze aandoening gemonitord moet worden. Het opnemen van MASLD in richtlijnen en standaarden over DM2, obesitas en CVRM zou hierin een belangrijke rol kunnen spelen. Obesitas en DM2 zijn de belangrijkste risicofactoren voor MASLD. De behandelaar behoort deze risicofactoren optimaal te behandelen en de mensen met MASLD te begeleiden in hun streven naar een gezonde leefstijl om incidentie en progressie van MASLD zoveel mogelijk te beperken en terug te dringen. Aandachtspunten zijn gezonde voeding en een gezond gewicht, voldoende beweging en minder zitten en geen gebruik van alcohol. Ook de deelname aan de periodieke monitoring van MASLD-fibrose vraagt aandacht van de behandelaar. De behandelaar geeft informatie over de procedure en noodzaak van monitoring op zodanige wijze dat de patiënt het belang van deelname aan de monitoring inziet en daarvoor verantwoordelijkheid kan nemen. De behandelaar heeft kennis van de deelname en de resultaten van de fibrosemonitoring. De behandelaar heeft kennis van het advies dat uit de uitslag van de monitoring voortvloeit en het opvolgen van dat advies door de patiënt. Het merendeel van de patiënten met MASLD bevindt zich in de eerste lijn en zou middels een FIB-4 score kunnen worden gemonitord. Het standaard bloedonderzoek dat nodig is voor het berekenen van de FIB-4 score, is goed beschikbaar voor elke huisarts (zie module identificatie MASLD-fibrose). Transiënte elastografie zoals met een FibroScan® is meestal niet beschikbaar in de eerste lijn. Een FibroScan® is ook in de tweede lijn nog niet in elk ziekenhuis aanwezig.

Rationale/balans tussen de argumenten voor en tegen

Progressie van fibrose bij MASLD lijkt een traag proces, maar is afhankelijk van diverse factoren zoals de aanwezigheid van MASH, leeftijd en co-morbiditeit zoals DM2. Hoewel de beschikbare literatuur beperkt is, is het aannemelijk dat een graad toename van fibrose minimaal 5 jaar duurt. De commissie heeft mede in overweging genomen de aanbevelingen van internationale richtlijnen om een surveillance-interval van 3-5 jaar aan te houden. Een voordeel hiervan is dat het niet nodig is de diagnose MASH middels een leverbiopt te stellen, gezien op grond van de literatuur hier een andere surveillance-interval zou kunnen worden aangehouden (zie internationale richtlijnen). Het is niet ondenkbaar dat in de komende tijd meer duidelijk wordt welke risicofactoren bijdragen aan progressie van fibrose bij MASLD en hoe deze optimaal non-invasief gemonitord kan worden. Anderzijds geeft deze aanbeveling ruimte om het interval in bepaalde gevallen te verkorten of te verlengen, afhankelijk van fibrosegraad, co-morbiditeit, leeftijd en vooral persoonlijke voorkeur van de patiënt. Dit betekent bijvoorbeeld dat de hoofdbehandelaar in overleg met de patiënt in het geval van F3 bij een 35-jarige vrouw met DM2 eerder surveillance verricht dan bij de man van 68 jaar met F0 zonder co-morbiditeit.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Volwassenen met MASLD bij wie er nog geen sprake is van cirrose (= F4-stadium), dat wil zeggen fibrosestadium F0 tot en met F3, worden gemonitord op mogelijke progressie van het fibrosestadium. Dit kan worden gedaan met non-invasieve diagnostiek (dat wil zeggen: geen leverbiopt) zoals een FIB-4 test, ELF of transiënte elastografie, bijvoorbeeld FibroScan®. Het monitoren van mogelijke fibroseprogressie is belangrijk omdat het leverfibrose-stadium bij MASLD een voorspellende factor is voor complicaties, zoals cirrose, hepatocellulair carcinoom (HCC), portale hypertensie (varices en ascites) en tevens met lever-gerelateerde mortaliteit en all-cause mortality. Er is echter geen duidelijkheid over het optimale monitoringsinterval, wat leidt tot praktijkvariatie.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Progression rate of liver fibrosis in MASLD

|

No GRADE |

The fibrosis progression rate varied widely between the studies. Pooled effects ranged from 0.03 to 0.15 fibrosis stages/year.

Fibrosis progression rate is different for 1) patients with NAFL and patients with MASH, 2) patients with MASH with inflammation at baseline and patients with MASH without inflammation at baseline, and 3) patients with fibrosis at baseline and patients without fibrosis at baseline.

Source: Argo, 2009; Singh, 2015 and Roskilly, 2021 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Argo (2009) performed a systematic review to identify predictors for the development of advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) in patients with MASH. They searched MEDLINE, PubMed and EMBASE for studies published between 1966 and 2008. Argo (2009) collected individual-level, primary data from ten longitudinal studies. Data of patients with biopsy-proven MASH were included when information on two liver biopsies was available, with at least one year interval between the liver biopsies. In total, data of 221 patients could be included. Important baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. Argo (2009) reported also on liver fibrosis progression rate.

Singh (2015) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis in order to determine differences in liver fibrosis progression (rate) in patients with NAFL (equals isolated steatosis) versus MASH. They searched several databases until June 2013, including Ovid Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science, and Scopus. Only studies in which the time between paired liver biopsies was at least one year and studies containing sufficient information to estimate the liver fibrosis progression rate were included. Singh (2015) identified 11 observational studies (N=411), which were performed in adult patients with biopsy-proven MASLD. Important baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. The quality of the studies was assessed using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale. Primary outcome measure was fibrosis progression rate, which was calculated as number of migrated stages in paired biopsies during the period between the biopsies.

Roskilly (2021) performed a systematic review on fibrosis progression rate in patients with MASH, who participated in the placebo group of RCTs. They searched several databases, including Medline, Embase and Cochrane Library, until January 2020. Roskilly (2021) included randomized placebo-controlled trials in adults with MASH, in which liver histology was an outcome measure and information on change in fibrosis based on repeated biopsy was available. In total, 35 RCTs were included, in which 1419/1709 (83%) patients had a repeated biopsy. The assessment of liver histology varied from evaluation by a single pathologist to multiple blinded pathologists. The median duration (range) of the trials was 48 (24 to 96) weeks. The quality of the studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. The outcome measure was fibrosis progression rate, which was calculated as mean change in fibrosis divided by the duration of the trial in years. This data was extracted as mean change in fibrosis or as proportions of participants that had progression or regression of fibrosis. If insufficient data were available, Roskilly (2021) assumed that reported fibrosis changes were by a single stage.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the studies included in the systematic reviews on fibrosis progression rate in patients with MASLD/MASH (Argo (2009), Singh (2015) and Roskilly (2021).

|

|

Argo (2009) |

Singh (2015) |

Roskilly (2021) |

|

N |

221 |

411 |

1419 |

|

Age (years, mean) |

47.4±11.4 |

44 to 55 |

37.9 to 55.5* |

|

Male (%) |

36.2 |

53 |

NR |

|

BMI (mean) |

31.8±5.3 |

27.4 to 37.7 kg/m2 |

26.2 to 46.8 kg/m2* |

|

Diabetes (%) ** |

79* |

49.9 |

0 to 100* |

|

NAFL/MASH (%) |

0/100 |

36.5/63.5 |

0/100 |

*Data are presented as ranges of respectively mean age, mean BMI and proportion of patients with diabetes in the trials. **It was not reported whether this was defined as diabetes mellitus type 2 and/or type 1.

Results

Progression rate of liver fibrosis in MASLD

Argo (2009), Singh (2015) and Roskilly (2021) reported on the outcome measure fibrosis progression rate. The results of Argo (2009) and Singh (2015) are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Fibrosis progression rate (SD/95%CI) and time to progression (95%CI) in patients with MASLD/MASH, included in studies in Argo (2009), Singh (2015) and Roskilly (2021).

|

Study |

Population |

Definition of progression |

Fibrosis progression rate (stages/year ± SD/95%CI) |

Time to progression (years (95%CI)) |

|

Argo (2009) |

MASH |

Progression to F3 or F4 |

0.03±0.53 |

NR |

|

|

MASH without inflammation on initial biopsy |

Progression to F3 or F4 |

NR |

13.4 (13.1 to 14.0) |

|

|

MASH with inflammation on initial biopsy |

Progression to F3 or F4 |

NR |

4.2 (3.2 to 5.9) |

|

Singh (2015) |

MASLD, with F0 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.13 (0.07 to 0.18) |

7.7 (5.5 to 14.8) |

|

|

NAFL, with F0 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.07 (0.02 to 0.11) |

14.3 (9.1 to 50.0) |

|

|

MASH, with F0 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.14 (0.07 to 0.21) |

7.1 (4.8 to 14.3) |

|

|

MASLD, with F1 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.10 (0.04 to 0.16) |

10 (6.2 to 25.0) |

|

|

NAFL, with F1 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.15 (-0.09 to 0.40) |

NR |

|

|

MASH, with F1 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.08 (-0.01 to 0.17) |

NR |

|

|

MASLD, with F0/F1 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.12 (0.07 to 0.16) |

8.3 (6.2 to 14.3) |

|

|

NAFL, with F0/F1 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.09 (0.04 to 0.14) |

11.1 (7.1 to 25.0) |

|

|

MASH, with F0/F1 at baseline |

Progression of one fibrosis stage |

0.10 (0.03 to 0.17) |

10 (5.9 to 33.3) |

|

Roskilly (2021) |

MASH |

Mean change in fibrosis or as proportion of participants that had progression of fibrosis |

No pooled effect, but rate ranges from -0.64 (-0.85 to -0.43) to 0.43 (-0.13 to 0.99) stages/year |

NR |

Argo (2009) reported on the time to progression to advanced fibrosis, which was defined as F3 or F4 on biopsy. In the entire cohort, mean progression rate (± SD) was 0.03±0.53 stages/year. In total, 37.6% patients progressed to higher fibrosis stage, 41.6% remained stable and 20.8% improved in fibrosis stage. In the group patients with fibrosis progression (n=83), mean annual progression rate (± SD) was 0.41±0.4 stages over a mean interval (±SD) of 5.9±4.9 years.

In addition, Argo (2009) found that inflammation on the initial biopsy is a key predictor for developing advanced fibrosis. Therefore, they calculated the median time for progression to advanced fibrosis separately for the group with and without lobular pattern of inflammation on initial biopsy. The median time for progression to advanced fibrosis (95%CI) was respectively 4.2 (3.2 to 5.9) years and 13.4 (13.1 to 14.0) years in patients with and without inflammation on initial biopsy.

Singh (2015) reported on the outcome measure fibrosis progression rate in the entire cohort, but also separately for NAFL and MASH. Progression and improvement in fibrosis stage were defined as respectively an increase or decrease of at least one fibrosis stage compared to baseline.

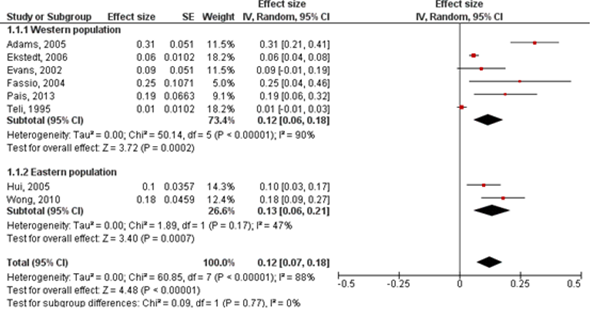

Patients with MASLD

Eleven studies (N=366) provided information to estimate fibrosis progression rate in patients with MASLD. In total, 132/366 (36.1%) patients with MASLD had progression in fibrosis stage, 158/366 (46.2%) patients remained stable and 76/366 (20.8%) patients improved in fibrosis stage. The overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with baseline F0 (n=131) was 0.12 (0.07 to 0.18) stages. This corresponds to a mean progression (95%CI) of one fibrosis stage over 7.7 (5.5 to 14.8) years (Figure 1). The overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with baseline F1 (n=119) was 0.10 (0.04 to 0.16) stages. This corresponds to a mean progression (95%CI) of one fibrosis stage over 10 (6.2 to 25.0) years. In patients with baseline F0 or F1 (n=250), the overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) was 0.12 (0.07 to 0.16) stages, which corresponds to a mean progression (95%CI) of one fibrosis stage over 8.3 (6.2 to 14.3) years.

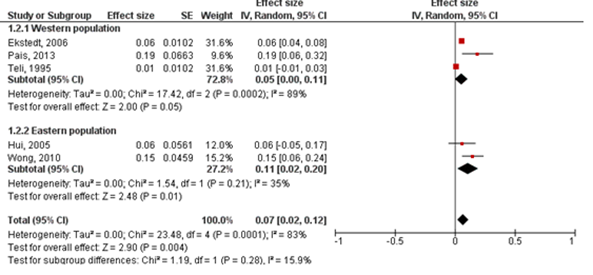

Patients with NAFL

Six studies (N=133) provided information to estimate fibrosis progression rate in patients with NAFL. In total, 52/133 (39.1%) patients with NAFL had progression in fibrosis stage, 70/133 (52.6%) patients remained stable and 11/131 (8.3%) patients improved in fibrosis stage. The overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with NAFL and baseline F0 (n=81) was 0.07 stages (0.02 to 0.12). This corresponds to a mean progression (95%CI) of one fibrosis stage over 14.3 (9.1 to 50.0) years (Figure 2). The overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with baseline F1 (n=39) was 0.15 (-0.09 to 0.40) stages. The corresponding time taken to progress by 1 fibrosis stage was not reported, since the lower limit of the 95%CI suggest that there could be net regression of fibrosis stage. In patients with baseline F0 or F1 (n=120), the overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) was 0.09 (0.04 to 0.14) stages, which corresponds to a mean progression (95%CI) of one fibrosis stage over 11.1 (7.1 to 25.0) years.

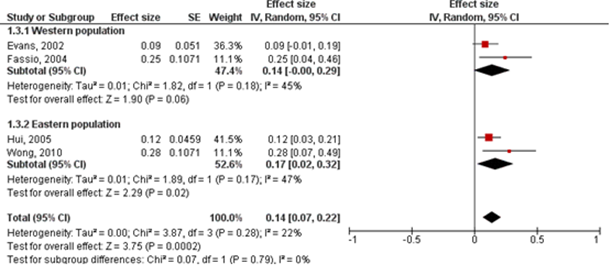

Patients with MASH

Seven studies (N=116) provided information to estimate fibrosis progression rate in patients with MASH. In total, 40/116 (34.5%) patients with MASH had progression in fibrosis stage, 45/116 (38.8%) patients remained stable and 31/116 (26.7%) patients improved in fibrosis stage. The overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with MASH and baseline F0 (n=) was 0.14 stages (0.07 to 0.22). This corresponds to a mean progression (95%CI) of one fibrosis stage over 7.1 (4.8 to 14.3) years (Figure 3). The overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with baseline F1 (n=49) was 0.08 (-0.01 to 0.17) stages. The corresponding time taken to progress by 1 fibrosis stage was not reported, since the lower limit of the 95%CI suggest that there could be net regression of fibrosis stage). In patients with baseline F0 or F1 (n=70), the overall annual fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) was 0.10 (0.03 to 0.17) stages, which corresponds to a mean progression (95%CI) of one fibrosis stage over 10 (5.9 to 33.3) years.

Figure 1: Fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with MASLD and F0 at baseline. Adapted from Singh (2015).

Figure 2: Fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with NAFL and F0 at baseline. Adapted from Singh (2015).

Figure 3: Fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in patients with MASH and F0 at baseline. Adapted from Singh (2015).

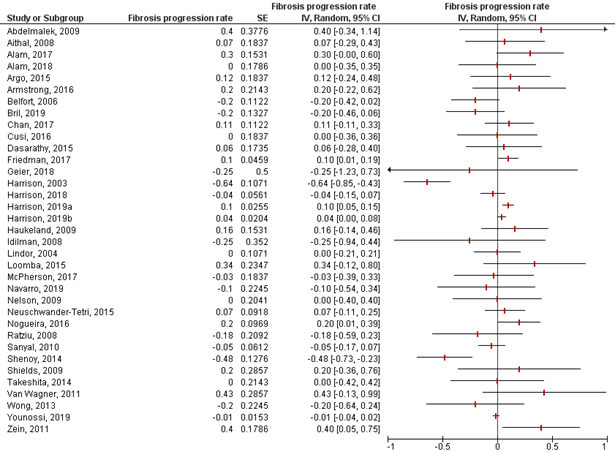

Roskilly (2021) reported on the outcome measure fibrosis progression rate in placebo-treated participants with MASH in randomized placebo-controlled trials (Figure 4). The fibrosis progression rate in individual studies ranged from -0.64 (-0.85 to -0.43) to 0.43 (-0.13 to 0.99) stages/year. Since there is high heterogeneity between the studies, we decided not to report the pooled effect in our literature analysis.

Figure 4: Fibrosis progression rate (95%CI) in placebo treated patients with MASH, included in trials in Roskilly (2021). Adapted from Roskilly (2021).

Level of evidence of the literature

Progression rate of liver fibrosis in MASLD

Since the evidence comes from observational, non-comparative studies, we did not perform a GRADE assessment. It is important to take the following issues into account, in interpreting the data:

- Risk of (selection) bias in the study of Roskilly (2021);

- Inconsistent results and heterogenous population;

- Assumption of Roskilly (2021): if insufficient data were available, they assumed that reported fibrosis changes were by a single stage;

- Serious imprecision: for some (subgroup) analyses, the number of patients is very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

In order to answer the clinical question on the optimal interval for monitoring of liver fibrosis in patients with MASLD, we preferably should have found studies in which the effectiveness of different intervals for fibrosis monitoring is evaluated in patients with MASLD with F0-F3 fibrosis stage. However, these studies are not available yet. The working group decided to search for studies which provide information on fibrosis progression rate in adult patients with MASLD. Therefore, a systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the progression rate of liver fibrosis in adults with MASLD without cirrhosis, i.e. F0-F3?

P (patients): Adults with MASLD without cirrhosis (F0-F3)

O (outcome measure): Progression rate of liver fibrosis

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered progression rate of liver fibrosis in MASLD as a critical outcome measure for decision making.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 19 July 2022. The detailed search strategy is given under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 358 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews on fibrosis progression rate in adults with MASLD without cirrhosis. 14 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, eleven studies were excluded, see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods, and three studies were included. Since those studies are non-comparative studies, we described the results of the studies and did not perform a GRADE assessment.

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Argo, 2009; Singh, 2015 and Roskilly, 2021). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Argo, C. K., Northup, P. G., Al-Osaimi, A. M., & Caldwell, S. H. (2009). Systematic review of risk factors for fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of hepatology, 51(2), 371-379.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (2021). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis2021 update. Journal of hepatology, 75(3), 659-689.

- Francque, S., Lanthier, N., Verbeke, L. et al (2018). The Belgian association for study of the liver guidance document on the management of adult and paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Gastroenterol Belg, 81(1), 55-81.

- Marchesini, G., Bugianesi, E., Burra, P. et al (2022). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults 2021: A clinical practice guideline of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF), the Italian Society of Diabetology (SID) and the Italian Society of Obesity (SIO). Digestive and Liver Disease, 54(2), 170-182.

- Singh, S., Allen, A. M., Wang, Z. et al (2015). Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology, 13(4), 643-654.

- Srivastava, A., Gailer, R., Tanwar, S. et al (2019). Prospective evaluation of a primary care referral pathway for patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of hepatology, 71(2), 371-378.

- Roskilly, A., Hicks, A., Taylor, E. J. et al (2021). Fibrosis progression rate in a systematic review of placebo?treated nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver International, 41(5), 982-995.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What is the fibrosis progression rate in adults with MASLD without cirrhosis (F0-F3)?

Evidence table for systematic reviews

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Roskilly, 2021 |

SR and meta-analysis of placebo-treated patients in RCTs

Literature search up to January 2020

A: Abdelmalek, 2009 B: Aithal, 2008 C: Alam, 2016 D: Alam, 2017 E: Argo, 2015 F: Armstrong, 2016 G: Belfort, 2006 H: Bril, 2019 I:Chan, 2017 J: Cusi, 2016 K: Dasarathy, 2015 L: Friedman, 2017 M: Geier, 2018 N: Harrison, 2003 O: Harrison, 2018 P: Harrison, 2019a Q: Harrison, 2019b R: Haukeland, 2009 S: Idilman, 2008 T: Lindor, 2004 U: Loomba, 2015 V: McPherson, 2017 W:Navarro, 2019 X: Nelson, 2009 Y: Neuschwander- Tetri, 2015 Z: Nogueira, 2016 A1: Ratziu, 2008 B1: Sanyal, 2010 C1: Shenoy, 2014 D1: Shields, 2009 E1: Takeshita, 2014 F1: Van Wagner, 2011 G1: Wong, 2013 H1: Younossi, 2019 I1: Zein, 2011

Study design: RCT (only placebogroups were included)

Setting and Country: A: Multicentre B: Single centre C: Single centre D: Single centre E: Single centre F: Multi centre G: Single centre H: Multi centre I:Single centre J: Single centre K: Multi centre L: Multi centre M: Multi centre N: Single centre O: Multi centre P: Multi centre Q: Multi centre R: Multi centre S: Single centre T: Multi centre U: Multi centre V: Multi centre W: Multi centre X: Multi centre Y: Multi centre A1: Single centre B1: Single centre C1: Multi centre D1: Multi centre E1: Single centre F1:Single centre G1 :Single centre H1: Multi centre I1: Multi centre

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Most of the included trials have commercial funding. Besides: The authors of the SR have no relevant conflicts to declare. Dr Parker has received personal fees from Sandoz outside the submitted work. Dr Rowe has received personal fees from Abbvie and Roche outside the submitted work. |

Inclusion criteria SR: placebo-controlled RCTs in adults with MASH, which have liver histology as an endpoint and reported information on change in fibrosis (in aggregate or individual level).

Exclusion criteria SR: NR

35 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N (with paired biopsy) A: 29 B: 30 C: 15 D: 10 E: 13 F: 22 G: 21 H: 24 I:42 J: 42 K: 19 L: 12 M: 4 N: 20 O: 69 P: 74 Q: 93 R: 24 S: 25 T: 57 U: 25 V: 17 W:21 X: 6 Y: 98 Z: 28 A1: 31 B1: 72 C1:32 D1:10 E1:15 F1:7 G1:20 H1:25 I1: 26

Mean age: A: 45.7 B: 55 C: 37.9 D: 38.8 E: 47.2 F: 52 G: 51 H: 57 I:50.1 J: 49 K: 49.8 L: 53.7 M: NR N: 50.2 O: 56 P: 54.6 Q: NR R: 49.9 S: 45.8 T: 48.5 U: 49.5 V: 45 W: 49.5 X: 52.5 Y: 51 Z: 53.9 A1: 54.1 B1: 45.4 C1: 41.1 D1: 44.4 E1: 55.5 F1: 53 G1: 48 H1: 55 I1: 49.6

Sex: NR

BMI (kg/m2) A: 34.7 B: 30.8 C: 26.2 D: 41.5 E: 46.8 F: 37.7 G: 32.9 H: 33.6 I:31 J: 34.5 K: 35.7 L: 34.1 M: NR N: 30.8 O: 32.7 P: 35.0 Q: 33.9 R: 30.3 S: 32.2 T: 31.7 U: 32.9 V: 34.1 W:33.4 X: 34 Y: 34 Z: 30.3 A1: 54.1 B1: 45.4 C1: 41.1 D1: 44.4 E1: 55.5 F1: 53 G1: 48 H1: 55 I1: 49.6

Diabetes (%) A: 32 B: 0 C: 10 D: 20 E: 35.3 F: 31 G: NR H: 100 I:60 J: 55 K: 100 L: 44.4 M: NR N: 23 O: 66 P: 50 Q: 48.6 R: 33 S: NR T: NR U: 28 V: 57 W:28 X: 16 Y: 52 Z: NR A1: 35 B1: 0 C1: NR D1:0 E1: NR F1: 13 G1: 40 H1:56 I1:13.8

Also reported: hypertension, participants with F0

Groups comparable at baseline? NA |

NA

|

NA

|

End-point of follow-up (weeks):

A: 48 B: 48 C: 48 D: 48 E: 48 F: 48 G: 24 H: 72 I:48 J: 72 K: 48 L: 48 M: 48 N: 24 O: 96 P: 52 Q: 72 R: 24 S: 48 T: 96 U: 24 V: 96 W:48 X: 48 Y: 72 Z: 24 A1: 48 B1: 96 C1:16 D1: 48 E1: 24 F1: 48 G1: 24 H1: 72 I1: 48

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? NA (focus on patients with paired biopsies)

|

Fibrosis progression rate Defined as rate per year, calculated by dividing the change in fibrosis by the duration of each trial measured in years.

Effect measure: FPR [95% CI]: A: 0.40 (-0.34 to 1.14) B: 0.07 (-0.29 to 0.42) C: 0.30 (0.00 to 0.60) D: 0.00 (-0.35 to 0.35) E: 0.12 (-0.25 to 0.48) F: 0.20 (-0.22 to 0.62) G: -0.20 (-0.42 to 0.02) H: -0.20 (-0.46 to 0.06) I: 0.11 (-0.11 to 0.33) J: 0.00 (-0.36 to 0.36) K: 0.06 (-0.28 to 0.40) L: 0.10 (0.01 to 0.19) M: -0.25 (-1.23 to 0.73) N: -0.64 (-0.85 to -0.43) O: -0.04 (-0.15 to 0.08) P: 0.10 (0.05 to 0.15) Q: 0.04 (0.00 to 0.08) R: 0.16 (-0.14 to 0.46) S: -0.25 (-0.94 to 0.44) T: 0.00 (-0.21 to 0.21) U: 0.34 (-0.12 to 0.80) V: -0.03 (-0.39 to 0.33) W: -0.10 (-0.54 to 0.34) X: 0.00 (-0.40 to 0.40) Y: 0.07 (-0.11 to 0.24) Z: 0.20 (0.01 to 0.39) A1: -0.18 (-0.59 to 0.23) B1: -0.05 (-0.17 to 0.07) C1: -0.48 (-0.73 to -0.23) D1: 0.20 (-0.36 to 0.76) E1: 0.00 (-0.42 to 0.42) F1: 0.43 (-0.13 to 0.99) G1: -0.20 (-0.64 to 0.24) H1: -0.01 (-0.04 to 0.01) I1: 0.40 (0.05 to 0.75)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.00 (-0.05 to 0.06) Heterogeneity (I2): 68%

|

Authors conclusion: The FPR in placebo-treated randomised trial participants with MASH is substantially lower than the rate described in observational studies. The true rates of fibrosis progression in MASH may be lower than previously estimated. Reduced rates of fibrosis progression have an important effect on projected rates of cirrhosis development, reducing these and the estimated future burden of disease.

Remarks: In most of the studies, patients in both treatment groups also received lifestyle intervention (for details see Table 2 in Roskilly, 2021).

Sensitivity analyses were performed: Trials with low risk of bias Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.03 (-0.02 to 0.07) Heterogeneity (I2): 59%

Trials including >50 patients in placebo group Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.03 (-0.01 to 0.08) Heterogeneity (I2): 72%

However, heterogeneity was still high between the studies. Therefore, we decided not to show the pooled effect.

|

|

Singh, 2015 |

SR and meta-analysis of observational studies

Literature search up to June 2013.

A: Adams, 2005 B: Argo, 2009 C: Ekstedt, 2006 D: Evans, 2002 E: Fassio, 2004 F: Hamaguchi, 2010 G: Hui, 2005 H: Pais, 2013 I: Ratziu, 2000 J: Teli, 1995 K: Wong, 2010

Study design: observational studies

Setting and Country: A: MN B: VA C: Sweden D: UK E: Argentina F: Japan G: Hong Kong H: France I: France J: UK K: Hong Kong

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: not reported for the individual studies

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

11 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N (with paired biopsies) A: 103 B:5 C:70 D:7 E:22 F:39 G:17 H:70 I:14 J:12 K:52

Mean age (SD)/ median (range): A: 45±11 B:NR C: 51±13 D: 49±10 E: 45±13 F: 47 (20-79) G: 42±3 H: 52±10 I: 49 (20-79) J: 55 (26-79) K: 44±9

Sex (% males): A: 37 B: NR C: 67 D: 43 E: 41 F: 56 G: 65 H: NR I: 34 J: 55 K: 65

BMI (kg/m2, SD) or median (range): A: NR B: 37.7±6.5 C:28.3±3.8 D:32.4±5.0 E:29.8 (24.0 to 38.2) F: 27.8 (22.5 to 44.4) G: 29.3 (23 to 35.5) H:29±3.6 I: 29.1 (25.1 to 45.7) J: NR K: 27.4±3.7

Diabetes (%): A: 42 B:60 C:85 D: 43 E:36 F:77 G:24 H:35 I:16 J:10 K:50

Groups comparable at baseline: NA |

NA

|

NA |

End-point of follow-up (total person years; mean (SD) and /or range)

A: NR; 3.2 (3.0); 0.7-21 B: 22 p-y; 4.4; 3.0-6.4 C: 1202 p-y; 13.8 (1.2); 10.3-16.3 D: 57.2 p-y; 8.2; 5.5-11.9 E: NR; 5.3 (2.7); 3.0-14.3 F: NR; 2.4; 1.0-8.5 G: 97.8 p-y; 6.1; 3.8-8.0 H: 102.7 p-y; 3.7 (2.1) I: 73 p-y; NR; 1.5-15.0 J: NR; 11.6; 7.6-16 K: NR; 3.0; NR

|

Fibrosis progression rate Defined as number of stages migrated in paired biopsy specimens, over the time difference between the two biopsy samples. Calculated as the difference in fibrosis stage between first and last biopsy divided by the time between biopsies in years.

Entire cohort (patients with baseline F0): A: 0.19 (0.06 to 0.31) H: 0.31 (0.21 to 0.41) J: 0.01 (-0.01 to 0.03) D: 0.09 (-0.01 to 0.19) E: 0.25 (0.04 to 0.46) C: 0.06 (0.04 to 0.08) G: 0.10 (0.03 to 0.18) K: 0.18 (0.09 to 0.26)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.13 (0.07 to 0.18) Heterogeneity (I2): 88.1%*

Patients with NAFL (with baseline F0): J: 0.01 (-0.01 to 0.03) C: 0.06 (0.04 to 0.08) H: 0.19 (0.06 to 0.31) K: 0.15 (0.06 to 0.24) G: 0.06 (-0.05 to 0.16)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.07 (0.02 to 0.11) Heterogeneity (I2): 81.2%*

Patients with MASH (with baseline F0): D: 0.09 (-0.01 to 0.19) E: 0.25 (0.04 to 0.46) K: 0.28 (0.07 to 0.49) G: 0.12 (0.03 to 0.31)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.14 (0.07 to 0.21) Heterogeneity (I2): 21.1%*

*subgroup analyses available for western population vs eastern population.

Also reported: Pooled FPR for patients with baseline F1 and F0 + F1 (see table 3 in Singh, 2015).

|

Authors conclusion: In this systematic review and meta-analysis of paired liver biopsy studies in patients with MASLD, contrary to conventional paradigm, we found that both patients with NAFL and MASH develop progressive hepatic fibrosis, progressing by 1 fibrosis stage (from baseline stage 0 fibrosis) over 14.3 and 7.1 years, respectively. A small subset of these patients may develop rapidly progressive hepatic fibrosis. Based upon this systematic review, assuming that 80-100 million Americans are afflicted with MASLD in the United States, a significant number of patients with MASLD are at risk for progressive liver disease than previously appreciated. Effective therapies are needed to halt progression of fibrosis in MASLD.

Remarks: In some of the studies patients received potential disease modifying therapy (metformin, TZD or vitamin E) an/or non-pharmacological interventions (for details, see table 2 in Singh (2015). |

|

Argo, 2009 |

SR and meta-analysis of observational studies and case-series (individual patient-level data)

Literature search up to 2008.

A: Lee, 1989 B: Powell, 1990 C: Bacon, 1994 D: Ratziu, 2000 E: Evans, 2002 F: Harrison, 2003 G: Fassio, 2004 H: Adams, 2005 I: Hui, 2005 J: Ekstedt, 2006

Study design: Retrospective observational studies and case-series

Setting and Country: A: clinical and hospital database B: clinical and hospital database C: unknown D: clinical and hospital database E: clinical and hospital database F: clinical and hospital database G: clinical and hospital database H: clinical and hospital database I: clinical and hospital database J: national registry data Country not reported in the SR.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The authors who have taken part in this study declared that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript. Not reported in the SR for the individual studies.

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

10 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N (with paired biopsies) A: 13 B: 13 C: 2 D: 10 E: 7 F: 19 G: 22 H: 94 I: 12 J: 29

Mean age (SD)/ median (range): A: 55.4±11.1 B: 48.9±12.2 C: NR D: NR E: 57.5±9.1 F: 50.4±8.1 G: 44.7±13.0 H: 45.2±11.2 I: 43.3±11.1 J: 49.7±11.0

Sex (n/N males): A: 2/13 B: NR C: NR D: NR E: 3/7 F: 11/19 G: 9/22 H: 34/94 I: 6/12 J: 19/29

BMI (kg/m2, SD) or median (range): A: NR B: NR C: NR D: NR E: 32.4 (±5.1) F: 33.8 (±5.9) G: 30.7 (±4.5) H: 32.8 (±5.4) I: 28.1 (±3.3) J: 29.3 (±4.4)

Diabetes (n/N): A: 7/13 B: 6/13 C: NR D: NR E: 3/7 F: 8/19 G: 8/22 H: 42/94 I: 5/12 J: 3/29

Groups comparable at baseline: NA |

NA

|

NA |

End-point of follow-up (total person years; mean (SD) and /or range)

A: 3.6±1.8 B: 3.5±1.6 C: 5.5 (4–7) D: 4.4±4.0 E: 8.2±2.6 F: 5.4±2.7 G: 5.3±2.7 H: 3.0±2.8 I: 5.8±1.4 J: 13.7±1.0

|

Fibrosis progression rate Advanced fibrosis was defined as the presence of stage 3 or 4 fibrosis on biopsy.

Values for individual studies are not reported à individual patient-level data

Entire cohort Mean rate of fibrosis progression: 0.0.3±0.53 stages/year

Patients with fibrosis progression Mean rate of fibrosis progression: 0.41±0.4 stages/year

Patients with inflammation Median time for progression to F3 or F4: 4.2 (3.2 to 5.9) years

Patients without inflammation Median time for progression to F3 or F4: 13.4 (13.1 to 14.0) years

|

Authors conclusion: Our study estimates that 5–10% of patients with MASH diagnosed on their initial biopsy will have clinically significant fibrosis on their initial biopsy and an additional 15–20% will progress to severe fibrosis in less than a decade, with the majority of affected patients being younger than 60 years. Although it remains unclear whether inflammation is a sequelae of lipid peroxidation or a primary facilitator of oxidative stress, the results of this analysis point to inflammation as the key predictor of eventual histological progression and thus potentially a major therapeutic target in MASH

Remarks:

|

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Argo, 2009 |

Yes |

Yes |

No (no description of excluded studies) |

Yes |

NA |

NR |

May be (heterogenous cohort with MASH patients) |

No |

No (not for the individual studies) |

|

Singh, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

No (no references of excluded studies included) |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

May be (heterogenous population with biopsy proven MASLD, however subgroup analyses were available) |

No |

No (not for the individual studies) |

|

Roskilly, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

No (no references of excluded studies included) |

Yes |

NA |

Yes |

May be (heteregenous population with MASH à selection criteria of RCTs might be different) |

No |

No (not for the individual studies) |

Risk of bias tables

Risk of bias table for systematic reviews

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Loomba R, Wesley R, Pucino F, Liang TJ, Kleiner DE, Lavine JE. Placebo in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: insight into natural history and implications for future clinical trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Nov;6(11):1243-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.013. Epub 2008 Jul 25. PMID: 18829391; PMCID: PMC3133944. |

Wrong outcome (no information on progression rate, only information available on at least one or two point reduction in fibrosis ) |

|

Ng CH, Xiao J, Lim WH, Chin YH, Yong JN, Tan DJH, Tay P, Syn N, Foo R, Chan M, Chew N, Tan EX, Huang DQ, Dan YY, Tamaki N, Siddiqui MS, Sanyal AJ, Loomba R, Noureddin M, Muthiah MD. Placebo effect on progression and regression in NASH: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2022 Jun;75(6):1647-1661. doi: 10.1002/hep.32315. Epub 2022 Jan 24. PMID: 34990037. |

Wrong outcome (no information on progression rate, only information available on at least one point reduction/advancement in fibrosis ) |

|

Ampuero J, Gallego-Durán R, Maya-Miles D, Montero R, Gato S, Rojas Á, Gil A, Muñoz R, Romero-Gómez M. Systematic review and meta-analysis: analysis of variables influencing the interpretation of clinical trial results in NAFLD. J Gastroenterol. 2022 May;57(5):357-371. doi: 10.1007/s00535-022-01860-0. Epub 2022 Mar 24. PMID: 35325295; PMCID: PMC9016009. |

Wrong outcome (variables influencing interpretation of trial results) |

|

Balakrishnan M, Patel P, Dunn-Valadez S, Dao C, Khan V, Ali H, El-Serag L, Hernaez R, Sisson A, Thrift AP, Liu Y, El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Women Have a Lower Risk of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease but a Higher Risk of Progression vs Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jan;19(1):61-71.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.067. Epub 2020 Apr 30. PMID: 32360810; PMCID: PMC8796200. |

Wrong outcome (gender differences in e.g. prevalence of MAFLD /progression) |

|

Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J, Soni M, Prokop LJ, Younossi Z, Sebastiani G, Ekstedt M, Hagstrom H, Nasr P, Stal P, Wong VW, Kechagias S, Hultcrantz R, Loomba R. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017 May;65(5):1557-1565. doi: 10.1002/hep.29085. Epub 2017 Mar 31. PMID: 28130788; PMCID: PMC5397356. |

Wrong outcome (mortality) |

|

Farooqui MT, Khan MA, Cholankeril G, Khan Z, Mohammed Abdul MK, Li AA, Shah N, Wu L, Haq K, Solanki S, Kim D, Ahmed A. Marijuana is not associated with progression of hepatic fibrosis in liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Feb;31(2):149-156. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001263. PMID: 30234644; PMCID: PMC6467701. |

Wrong outcome (role of marijuana) |

|

Gruneau L, Ekstedt M, Kechagias S, Henriksson M. Disease Progression Modeling for Economic Evaluation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Oct 29:S1542-3565(21)01153-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.10.040. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34757199. |

Wrong outcome ((differences in) disease progression modelling) |

|

Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med. 2011 Dec;43(8):617-49. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.518623. Epub 2010 Nov 2. PMID: 21039302. |

Information on progression rate is very limited |

|

Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Aug;34(3):274-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x. Epub 2011 May 30. PMID: 21623852. |

Wrong study design (no meta-analysis, narrative review) |

|

Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016 Jul;64(1):73-84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. Epub 2016 Feb 22. PMID: 26707365. |

Studies (n=2) on fibrosis progression are also included in Singh (2015), no new information. |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 04-04-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 19-03-2024

De NVMDL is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied. De werkgroep heeft per module een inschatting gemaakt van de periode waarbinnen de modules beoordeeld zouden moeten worden voor eventuele herziening.

|

Module |

Uiterlijk jaar voor beoordeling |

|

Identificatie MASLD-fibrose |

2027 |

|

Leefstijlinterventies |

2027 |

|

Medicamenteuze behandeling |

2025 |

|

Bariatrische chirurgie |

2027 |

|

Cardiovasculair risicomanagement |

2027 |

|

Monitoring progressie van leverfibrose |

2027 |

|

HCC-surveillance |

2025 |

|

Organisatie van zorg |

2025 |

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met MASLD/MASH.

Werkgroep

- Dr. M.E. Tushuizen (voorzitter), MDL-arts, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, NVMDL

- Dr. A.G. Holleboom, internist-endocrinoloog en vasculaire geneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC, NIV

- Dr. J.G.P. Reijnders (vice-voorzitter), MDL-arts, HagaZiekenhuis, NVMDL

- Dr. M.M.J. Guichelaar, MDL-arts, Medisch Spectrum Twente, NVMDL

- Dr. J. Blokzijl, MDL-arts, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, NVMDL

- Dr. G. H. Koek, MDL-arts en leefstijlcoach, Maastricht UMC+, NVMDL

- Dr. S. Simsek, internist-endocrinoloog en vasculaire geneeskunde, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep, NIV

- Prof. dr. M.E. Numans, hoogleraar huisartsengeneeskunde/huisarts, NHG

- T.A. Korpershoek, Verpleegkundig specialist MDL, Albert Schweitzer ziekenhuis, V&VN MDL

- Drs. L.C. te Nijenhuis-Noort, Diëtist, NVD

- Drs. J.A. Willemse, Directeur/patiëntvertegenwoordiger, NLV

Klankbordgroep

- Prof. dr. J. Verheij, patholoog, Amsterdam UMC, NVVP

Met ondersteuning van

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Dr. M.E. Tushuizen (voorzitter) |

MDL-arts, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum |

Geen |

Ontwikkeling screening NAFLD bij DM2, projectleider, financier: Novo Nordisk; Ontwikkeling zorgpad NAFLD/NASH, geen projectleider, financier: Gilead; Ontwikkeling zorgpad NAFLD/NASH, projectleider, financier MLDS; Internationaal onderwijsprogramma, projectleider, financier: Pfizer. |

Vicevoorzitter aangesteld, voor module over medicamenteuze behandeling en module over CVRM. Daarmee restricties ten aanzien van besluitvorming bij de betreffende modules. |

|

Dr. J.G.P. Reijnders (vice-voorzitter) |

MDL-arts, HagaZiekenhuis, Erasmus MC (vanaf sept 2023) |

Lid Raad Kwaliteit NVMDL (onbetaald); Lid clinical board DGEA/DRCE/PRISMA netwerk |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Dr. M.M.J. Guichelaar |

MDL-arts, Medisch Spectrum Twente |

Lid Kwaliteitsvisitatie commissie-audits; Lid Auto-immuun hepatitis werkgroep (onbetaald); Secretaris NAFLD/ NASH werkgroep (onbetaald) |

Ontwikkeling Serious game voor NAFLD, financier: MLDS |

Geen restricties |

|

Dr. J. Blokzijl |

MDL-arts, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen |

Geen |

Extracellular vesicles: towards personalized monitoring NAFLD, geen projectleider, financier MLDS |

Geen restricties |

|

Dr. G. Koek |

MDL-arts, Maastricht UMC+, onderzoeker NUTRIM Universiteit Maastricht |

Lid adviesraad NLV |

Nieuwe medicatie bij NASH, projectleider, financier: Boehringer Ingelheim; Genfit Resolve-it trial, projectleider, financier Convance/Genfit; Onderzoek semaglutide, projectleider, financier: Novo Nordisk; ontwikkeling Happi Lever App, rol als projectleider, financier MLDS |

Restricties ten aanzien van besluitvorming bij de module over medicamenteuze behandeling. |

|

Dr. A.G. Holleboom |

Internist-endocrinoloog en vasculaire geneeskunde en assistant professor Amsterdam UMC; staflid vasculaire geneeskunde |

Betaald adviseurschap Novo Nordisk (neergelegd) |

Studie naar autophagic turnover of lipid droplets in NASH, projectleider, financier: Gilead; Ontwikkeling zorgpad NAFLD/NASH, geen projectleider, financier: Gilead; onderzoek naar non-invasieve proxies en Fibroscan in NAFLD in Helius study population, financier: Novo Nordisk. |

Restricties ten aanzien van besluitvorming bij de module over medicamenteuze behandeling. |

|

Dr. S. Simsek |

Internist-endocrinoloog Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep en Amsterdam UMC |

Voorzitter wetenschapscommissie NWZ; Begeleider promovendi |

Onderzoek naar semaglutide, participatie, financier: Novo Nordisk |

Restricties ten aanzien van besluitvorming bij de module over medicamenteuze behandeling. |

|

Prof. dr. M.E. Numans |

hoogleraar huisartsengeneeskunde LUMC |

Huisarts in Utrecht (betaald); voorzitter Autorisatiecommissie Standaarden NHG (vacatiegelden); Bestuurslid stichting SALTRO2 Diagnostic Living Lab (vacatiegelden); Adviesraad Leefstijl Norgine (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

T.A. Korpershoek |

Verpleegkundig specialist MDL, Albert Schweitzer ziekenhuis; flex-docent HAN-MDL opleiding |

Bestuurslid V&VN MDL; Voorzitter netwerk VS MDL V&VN MDL (vacatiegelden) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Drs. L.C. te Nijenhuis-Noort |

Diëtist/Klinisch epidemioloog |

Lid Netwerk MDL diëtisten (onbetaald); Lid Commissie Voeding NVMDL (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Drs. J.A. Willemse |

Directeur NLV |

Board member Liver Patients International (onbetaald); Member management board ERN RARE LIVER (patient advocate, (onbetaald); lid diverse internationale expert groups NAFLD/NASH (onbetaald) |

|

Geen restricties |

|

Klankbordgroep lid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Prof. dr. J. Verheij |

Patholoog, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door afvaardiging van de Nederlandse Leverpatiënten Vereniging in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kopje waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Nederlandse Leverpatiënten Vereniging en de aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Monitoring progressie van leverfibrose |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met MASLD/MASH. Tevens zijn er (aanvullende) knelpunten aangedragen door de Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen, Nederlandse Internisten Vereniging, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Klinische Geriatrie en de Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuizen via een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Literature search strategy

Zoekverantwoording

Algemene informatie

|

Cluster/richtlijn: Non-alcoholische leververvetting (NAFLD/NASH) |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag/modules: Wat is het optimale monitoringsinterval op fibrose progressie voor volwassenen met NAFLD zonder cirrose (F0 t/m F3)? |

|

|

Database(s): Ovid/Medline, Embase.com |

Datum: 19 juli 2022 |

|

Periode: 2005 - heden |

Talen: Engels, Nederlands |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Miriam van der Maten |

|

|

BMI-zoekblokken: voor verschillende opdrachten wordt (deels) gebruik gemaakt van de zoekblokken van BMI-Online https://blocks.bmi-online.nl/ Bij gebruikmaking van een volledig zoekblok zal naar de betreffende link op de website worden verwezen. |

|

|

Toelichting: Voor deze vraag is gezocht op de elementen:

à Het sleutelartikel van McPherson wordt, zoals al aangegeven, niet gevonden omdat dit geen SR betreft. Qua terminologie zou de studie wel gevonden worden.

à De overige sleutelartikelen worden wel gevonden met de zoekopdracht. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

323 |

226 |

358 |

Zoekstrategie

Embase.com

|

No. |

Query |

Results |

|

#6 |

#4 AND #5 |

323 |

|

#5 |

'meta analysis'/exp OR 'meta analysis (topic)'/exp OR metaanaly*:ti,ab OR 'meta analy*':ti,ab OR metanaly*:ti,ab OR 'systematic review'/de OR 'cochrane database of systematic reviews'/jt OR prisma:ti,ab OR prospero:ti,ab OR (((systemati* OR scoping OR umbrella OR 'structured literature') NEAR/3 (review* OR overview*)):ti,ab) OR ((systemic* NEAR/1 review*):ti,ab) OR (((systemati* OR literature OR database* OR 'data base*') NEAR/10 search*):ti,ab) OR (((structured OR comprehensive* OR systemic*) NEAR/3 search*):ti,ab) OR (((literature NEAR/3 review*):ti,ab) AND (search*:ti,ab OR database*:ti,ab OR 'data base*':ti,ab)) OR (('data extraction':ti,ab OR 'data source*':ti,ab) AND 'study selection':ti,ab) OR ('search strategy':ti,ab AND 'selection criteria':ti,ab) OR ('data source*':ti,ab AND 'data synthesis':ti,ab) OR medline:ab OR pubmed:ab OR embase:ab OR cochrane:ab OR (((critical OR rapid) NEAR/2 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ti) OR ((((critical* OR rapid*) NEAR/3 (review* OR overview* OR synthes*)):ab) AND (search*:ab OR database*:ab OR 'data base*':ab)) OR metasynthes*:ti,ab OR 'meta synthes*':ti,ab |

841282 |

|

#4 |

#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND ([english]/lim OR [dutch]/lim) AND [2005-2022]/py NOT ('conference abstract'/it OR 'editorial'/it OR 'letter'/it OR 'note'/it) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp) |

4879 |

|

#3 |

'disease course'/de OR 'disease exacerbation'/exp OR 'staging'/exp OR 'disease severity'/exp OR progression:ti,ab,kw OR enhance*:ti,ab,kw OR advance*:ti,ab,kw |

5891345 |

|

#2 |

'liver fibrosis'/exp/mj OR 'liver cirrhosis'/exp/mj OR fibrosis:ti,ab,kw OR fibrosing:ti,ab,kw |

423724 |

|

#1 |

'nonalcoholic fatty liver'/exp/mj OR 'nonalcoholic steatohepatitis'/exp/mj OR (((nonalcohol* OR 'non-alcohol*') NEAR/3 (steato* OR 'fatty liver*')):ti,ab,kw) OR nash*:ti,ab,kw OR nafld:ti,ab,kw |

64499 |

|

# |

Searches |

Results |

|

8 |

6 and 7 |

226 |

|

7 |

meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (metaanaly* or meta-analy* or metanaly*).ti,ab,kf. or systematic review/ or cochrane.jw. or (prisma or prospero).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or scoping or umbrella or "structured literature") adj3 (review* or overview*)).ti,ab,kf. or (systemic* adj1 review*).ti,ab,kf. or ((systemati* or literature or database* or data-base*) adj10 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((structured or comprehensive* or systemic*) adj3 search*).ti,ab,kf. or ((literature adj3 review*) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ti,ab,kf. or (("data extraction" or "data source*") and "study selection").ti,ab,kf. or ("search strategy" and "selection criteria").ti,ab,kf. or ("data source*" and "data synthesis").ti,ab,kf. or (medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane).ab. or ((critical or rapid) adj2 (review* or overview* or synthes*)).ti. or (((critical* or rapid*) adj3 (review* or overview* or synthes*)) and (search* or database* or data-base*)).ab. or (metasynthes* or meta-synthes*).ti,ab,kf. |

606896 |

|

6 |

5 not (comment/ or editorial/ or letter/ or ((exp animals/ or exp models, animal/) not humans/)) |

4757 |

|

5 |

limit 4 to ((english language or dutch) and yr="2005 -Current") |

5539 |

|

4 |

1 and 2 and 3 |

5831 |

|

3 |

exp Disease Progression/ or exp "Severity of Illness Index"/ or progression.ti,ab,kf. or enhance*.ti,ab,kf. or advance*.ti,ab,kf. |

3323007 |

|

2 |

exp Liver Cirrhosis/ or exp Fibrosis/ or fibrosis.ti,ab,kf. or fibrosing.ti,ab,kf. |

353533 |

|

1 |

exp Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/ or ((nonalcoholic or 'non-alcoholic') adj3 (steato* or 'fatty liver*')).ti,ab,kf. or nash*.ti,ab,kf. or nafld.ti,ab,kf. |

39791 |