Medicamenteuze behandeling

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van medicatie in de behandeling van volwassenen met MASH?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg eventueel een medicamenteuze behandeling in patiënten met MASH én fibrose waarbij leefstijlinterventies niet succesvol zijn gebleken. Leefstijlinterventies zijn de eerste keus behandeling, mede gezien de lage bewijsvoering voor de effectiviteit van medicamenteuze behandeling, onduidelijkheid over lange termijn resultaten en bijwerkingen en de beperkte opties van geschikte medicatie op dit moment.

Indien er gekozen wordt voor een medicamenteuze behandeling, overweeg dan het gebruik van pioglitazon of vitamine E. Schrijf geen vitamine E voor aan patiënten met MASH en diabetes mellitus type 2. Schrijf geen vitamine E of pioglitazon voor aan patiënten met levercirrose. Er zijn momenteel nog geen andere geschikte opties beschikbaar.

Bespreek de voor-en nadelen van de behandelingen met de patiënt.

Evalueer periodiek (bijv. na 3 of 6 maanden) de effecten van de behandeling en ga na of het veilig gecontinueerd kan worden.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In totaal zijn vier RCT’s gevonden die hebben gekeken naar de (on)gunstige effecten van medicamenteuze behandeling bij patiënten met MASH (stadia F1 t/m F4) vergeleken met placebo. Hiervan hebben drie studies de effecten van pioglitazon onderzocht en twee studies de effecten van vitamine E (één overlappende studie). Er zijn geen fase 3-studies gevonden met betrekking tot de effecten van obeticholzuur in patiënten met MASH. Voor de uitkomstmaten cirrose, HCC en decompensatie zijn eveneens geen studies gevonden.

De bewijskracht van de resultaten werd gelimiteerd door imprecisie en mogelijk risico op bias, vanwege onduidelijke rollen van de studie sponsoren en de wijze van toekennen van de interventies. De studiepopulaties bevatten enkel patiënten met diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) of patiënten met DM2 werden juist geëxcludeerd. Het bewijs voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat fibrose was voor zowel pioglitazon als vitamine E afkomstig uit één kleine studie met enkel patiënten met DM. Hierdoor is de bewijskracht zeer laag. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten steatose, MASH (middels de NAS-score) en adverse events is de bewijskracht laag. De algehele bewijskracht is zeer laag. Er is dus sprake van een kennislacune.

Chehrehgosha (2022) voerde een dubbel geblindeerde, placebo-gecontroleerde RCT uit naar het effect van onder andere pioglitazon (n=35) vergeleken met placebo (n=36) in patiënten met MASLD en DM2. Deze studie is niet opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse omdat in deze studie mogelijk ook patiënten zonder MASH zijn geïncludeerd. In deze studie vond men in de pioglitazon groep na 24 weken een grotere verbetering in steatose op basis van de CAP score gemeten met een FibroScanÒ (T0: 313.14 ± 30.40 dB/m à T24: 296.73 ± 40.13 dB/m, p<0.001) dan in de placebogroep (T0: 308.76 ± 30.59 à T24: 280.91 ± 34.52, p<0.001). Dit gold echter niet voor de uitkomstmaat fibrose, waar men in de placebogroep een groter verschil zag (T0: 7.49 ± 2.65 à T24: 7.17 ± 2.67, p=0.27) dan in de pioglitazon groep (T0: 6.48 ± 1.67 à T24: 6.42 ± 2.14, p=0.80). Er was een hoge drop-out in alle behandelgroepen. Daarnaast is er geen biopsie uitgevoerd om de status van MASLD te bepalen. Om deze redenen dienen de resultaten met voorzichtigheid geïnterpreteerd te worden.

De eerste keus therapie in patiënten met MASLD/MASH zijn leefstijlaanpassingen op het gebied van dieet en beweging. Er zijn enkele medicijnen onderzocht voor behandeling van patiënten met MASH in fase 3-studies, waaruit is gebleken dat pioglitazon en vitamine E overwogen kunnen worden in een selecte groep patiënten met MASH. Ondanks dat het gebruik van pioglitazon en vitamine E op korte termijn tot een reductie van steatose en necro-inflammatie in MASH zou kunnen leiden, zijn op de lange termijn de anti-fibrotische effecten onduidelijk. Tevens is het effect van vitamine E op MASH in patiënten met DM2 en levercirrose niet duidelijk. Ook zijn er onvoldoende gegevens over de effecten van pioglitazon bij patiënten met levercirrose.

Conform andere richtlijnen (o.a. EASL en AASLD) adviseren wij om medicamenteuze therapie (pioglitazon of vitamine E) alleen te overwegen in patiënten met MASH en enige vorm van fibrose, aangezien beide geen verbetering van de mate van fibrose laten zien en er geen data beschikbaar zijn over de uitkomsten op de lange termijn (EASL, 2016 and Chalasani, 2018). Pioglitazon kan eventueel preferentieel worden gebruikt bij de behandeling van patiënten met DM, indien er ook sprake is van MASLD. De dagelijkse praktijk laat echter zien dat pioglitazon steeds minder wordt ingezet bij de behandeling van DM, mede door de komst van nieuwe medicatie zoals GLP1-agonisten die een gunstiger effect hebben op (over)gewicht en metabole factoren. Een fase 2b-studie in 320 patiënten met MASH liet gunstige effecten zien van semaglutide in patiënten met MASH, alhoewel ook in deze studie geen significante verbetering van de mate van fibrose werd gezien ten opzichte van placebo (Newsome, 2021). Momenteel zijn fase 3-studies nog gaande, waardoor wij bij het schrijven van de richtlijn het gebruik van GLP1-agonisten en combinatiepreparaten hiervan (nog) niet mee hebben genomen bij het opstellen van de definitieve adviezen.

Pioglitazon is geassocieerd met gewichtstoename in patiënten die reeds obesitas hebben. Tevens is er onduidelijkheid over het veilig gebruik van pioglitazon op lange termijn. Zo zijn er bijvoorbeeld in studies in andere populaties associaties gevonden tussen het gebruik van pioglitazon en blaaskanker (Lewis, 2011; Levin, 2015). Ook is het onduidelijk of thiazolidinediones veilig gebruikt kunnen worden in patiënten met een pre-existente cardiale voorgeschiedenis (Schernthaner, 2010). Verder geldt ook voor vitamine E dat er enige onduidelijkheid is over veilig gebruik op lange termijn, bijvoorbeeld gezien eerdere associaties (uit non-MASH studies) met gastro-intestinale bloedingen en prostaatkanker.

Tijdens het gebruik van vitamine E en pioglitazon in de behandeling van MASH adviseren wij periodiek (drie tot zes maandelijks) te evalueren wat het effect is op verbetering van MASH, om daarmee verder gebruik te rechtvaardigen. Pragmatisch kan dan wellicht gevaren worden op verbetering van leverenzymafwijkingen, ondanks dat het werkelijke effect in studies is geëvalueerd middels histologie. Histologie verkrijgen in patiënten middels leverbiopsie is echter een invasieve procedure met bijkomende risico’s. Hierdoor zou het gebruik van deze medicatie niet alleen minder goed ontvangen kunnen worden bij de patiënt, maar wordt ook de patiënt wellicht blootgesteld aan (onnodige) risico’s. Wij adviseren derhalve te varen op indirecte parameters zoals leverenzymafwijkingen wellicht aangevuld met (jaarlijks) leverelasticiteit.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor aanvang van de medicamenteuze therapie is het verstandig om met de patiënt te bespreken dat het gebruik van pioglitazon en vitamine E off-label is in de behandeling van MASH en dat leefstijlaanpassingen de eerste keus behandeling is. Het is belangrijk om de voor- en nadelen van de medicamenteuze behandelingen met de patiënt te bespreken. Wij adviseren daarom om voorafgaand aan gebruik van vitamine E of pioglitazon te bespreken dat ondanks studies op korte termijn verbetering in MASH variabelen hebben laten zien, de lange termijn-effecten niet voldoende duidelijk zijn. Datzelfde geldt voor de mogelijke bijwerkingen op lange termijn. Gebruik van pioglitazon kan leiden tot een geringe gewichtstoename. Wij verwachten dat dit wordt gezien als een groot nadeel door zowel zorgverleners als patiënten aangezien de meeste patiënten met MASH reeds overgewicht hebben.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De geringe kosten van pioglitazon vormen geen belemmering voor de inzet van pioglitazon als behandeling van patiënten met MASH (www.medicijnkosten.nl).

Vitamine E (tocoferol) kan worden voorgeschreven door de behandelaar in de vorm van tocoferol drank. Deze wordt echter niet vergoed door de zorgverzekeraar. Hoewel de kosten niet hoog zijn, kan het wel een belemmering zijn voor de patiënt om vitamine E te gebruiken.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep verwacht dat het gebruik van pioglitazon en vitamine E weinig ingezet zal gaan worden voor de behandeling van MASH. Dit heeft deels te maken met de onduidelijkheid over de effecten en bijwerkingen op lange termijn. Daarnaast is pioglitazon steeds minder vaak onderdeel van de behandeling van patiënten met DM2. Daarentegen worden bijvoorbeeld GLP1-agonisten steeds meer gebruikt door patiënten met DM2, mede omdat deze medicijnen ook een significant gewichtsverlies geven. Wij verwachten dat met de mogelijke inzet van GLP1-agonisten en combinatiepreparaten hiervan voor behandeling van MASH in de toekomst, het draagvlak om deze therapie ook in te zetten ter behandeling van MASH groter zal zijn bij zowel zorgverleners en patiënten. Momenteel zijn er ook andere mogelijkheden om de MASH populatie met obesitas (BMI > 35) te behandelen, zoals bijvoorbeeld bariatrische chirurgie. Wij verwachten derhalve dat de uiteindelijke populatie patiënten met MASH die behandeld wordt en zal worden met pioglitazon en/of vitamine E klein zal zijn.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Momenteel zijn er slechts enkele fase 3-studies bekend over de medicamenteuze behandeling van patiënten met MASH. In deze studies wordt de effectiviteit van pioglitazon en vitamine E bekeken. De aanbeveling is gebaseerd op deze fase 3-studies. Er zijn hierbij enkele kanttekeningen te plaatsen; de bewijskracht van de gevonden resultaten is laag tot zeer laag, de effectiviteit op lange termijn is niet bekend, en ook de lange termijn bijwerkingen zijn niet goed bestudeerd in patiënten met MASH. Vandaar dat de aanbeveling enigszins voorzichtig is geformuleerd, waarbij er op dit moment het gebruik van pioglitazon en vitamine E gerechtvaardigd is voor een selecte groep patiënten met MASH. Leefstijlinterventies blijven echter de eerste keus behandeling. Daarnaast is het van belang om de voor- en nadelen van de behandelingen met de patiënt te bespreken en de effectiviteit en veiligheid periodiek te evalueren. Er lopen momenteel diverse fase 3-studies naar de effectiviteit van andere medicamenten – waaronder GLP-1 agonisten en schildklierreceptor agonisten– in de behandeling van patiënten met MASH. Naar verwachting is er dan een herziening nodig van onderstaande aanbevelingen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De behandeling van MASLD wordt gekenmerkt door leefstijladviezen, onder andere adviezen op gebied van gezonde voeding, beweging met uiteindelijk gewichtsverlies tot gevolg. Enkele medicamenteuze opties zijn onderzocht, maar bewijsvoering is gering en lange termijneffecten niet duidelijk. T.b.v. de voorliggende richtlijn wordt gezocht naar de toegevoegde waarde van behandeling met deze medicatie bij patiënten met MASLD. Hoewel er talrijke fase 2-studies zijn uitgevoerd en er diverse lopende fase 3-studies zijn, richten we ons alleen op medicatie waarvoor fase 3 studies zijn afgerond.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Part I: pioglitazone

Conclusions

Steatosis

|

Low GRADE |

Pioglitazone may result in a reduction of steatosis when compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Sources: Aithal, 2008; Sanyal, 2010; Cusi, 2016 |

MASH (NAS-score)

|

Low GRADE |

Pioglitazone may result in a decrease in NAS-score when compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010; Cusi, 2016 |

Fibrosis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of pioglitazone on fibrosis compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Sources: Cusi, 2016 |

Cirrhosis, HCC, Decompensation

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of pioglitazone on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation in patients with MASH. |

(serious) Adverse events

|

Low GRADE |

Pioglitazone may result in little to no difference in (serious) adverse events compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Sources: Aithal, 2008; Sanyal, 2010; Cusi, 2016 |

Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of pioglitazone on quality of life compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010 |

Part II: vitamin E

Conclusions

Steatosis

|

Low GRADE |

Vitamin E may result in a reduction of steatosis when compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010; Bril, 2019 |

MASH (NAS-score)

|

Low GRADE |

Vitamin E may result in an decrease in NAS-score when compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010; Bril, 2019 |

Fibrosis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of vitamin E on fibrosis compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Bril, 2019 |

Cirrhosis, HCC, Decompensation

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of vitamin E on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation in patients with MASH. |

(serious) Adverse events

|

Low GRADE |

Vitamin E may result in little to no difference in (serious) adverse events compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010; Bril, 2019 |

Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of vitamin E on quality of life compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010 |

Part III: obeticholic acid

Conclusions

All outcome measures

|

No GRADE |

No phase 3-study could be included on the effect of obeticholic acid in patients with MASH. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn on the effect of obeticholic acid on the outcome measures steatosis, MASH resolution, NAS, fibrosis, cirrhosis, HCC, decompensation, (serious) adverse events and quality of life in patients with MASH. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Aithal (2008) performed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the United Kingdom, in order to evaluate the effect of pioglitazone in the treatment of nondiabetic patients with MASH. The study included 74 nondiabetic adult patients with histology-proven MASH, which received either 30 mg pioglitazone (n = 37) or placebo (n = 37) once daily for 12 months. The follow period of the study was a total of twelve months. Both groups were also instructed to follow a hypocaloric diet of 500 Kcal and 30-40 minutes exercise for at least five days per week. The treatment groups did not differ with regard to mean age (range) (I: 52 (28-71) years vs. C: 55 (27-73) years), mean BMI±SD (I: 29.8±3.0 kg/m2 vs. C: 30.8±4.1 kg/m2) and proportion of patients with fibrosis (I: 23 (74%) vs. C: 25 (83%)). However the proportion of males was higher in the intervention group (70%), compared to the control group (51%). The number of patients with cirrhosis was not reported. Primary outcomes were reductions in hepatocyte injury and fibrosis scores on histology.

Sanyal (2010) performed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the United States of America, in order to investigate whether pioglitazone and vitamin E could be a possible treatment for MASH. The study included 247 nondiabetic adult patient with MASH, confirmed by two pathologists. Patients received either 30 mg pioglitazone (Ia, n = 80), 800 IU vitamin E (Ib, n = 84) or placebo (C, n = 83) once daily for 96 weeks. The follow period of the study was a total of 120 weeks. In addition, all groups received recommendation about lifestyle changes and diet. The treatment groups did not differ with regard to mean age±SD (Ia: 47±12.6 years vs. Ib: 47±12.1 years vs. C: 45±11.2 years), mean BMI (Ia: 34±6 kg/m2 vs. Ib: 34±7 kg/m2 vs C: 35±7 kg/m2), proportion of patients with fibrosis (Ia: 69 (86%) vs. Ib: 70 (83%) vs. C: 67 (81%)), number of patients with cirrhosis (Ia: 1 vs. Ib: 1 vs. C: 3) or proportion of males (Ia: 41% vs. Ib: 38% vs. C: 42%). The primary outcome of the study was an improvement in histologic features of MASH.

Cusi (2016) performed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the United States of America, in order to determine the efficacy and safety of long-term

pioglitazone treatment in adult patients with histology proven MASH and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Patients received either 30 mg pioglitazone (n = 50) or placebo (n = 51) once daily for 18 months. Pioglitazone dose was increased to 45 mg per day after two months. The follow period of the study was a total of 18 months. This was followed by an open-label phase in which both study groups received pioglitazone (not analyzed). All patients in both groups were instructed to follow a hypocaloric diet. After this study period, all patient received pioglitazone, but this part of the study is not included in our literature analysis. The treatment groups did not differ with regard to mean age±SD (I: 52±10 years vs. C: 49±11 years), mean BMI±SD (I: 34.3±4.8 kg/m2 vs. C: 34.5±4.8 kg/m2), proportion of patients with fibrosis (I: 35 (70%) vs. C: 31 (61%)) or proportion of males (I: 72% vs. C: 69%). The number of patients with cirrhosis was not reported. The primary outcome was a reduction of at least two points in NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) without worsening of fibrosis.

Bril (2019) performed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the United States of America, in order to determine whether vitamin E, alone or combined with pioglitazone, improves histology in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and MASH. In our literature analysis, we focus on the comparison between vitamin E and placebo treatment. Next to this combination treatment, 68 adult (almost exclusively male) patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and biopsy-proven MASH were assigned to take either 400 IU vitamin E (n = 36) or placebo (n = 32) twice daily for 18 months. The follow period of the study was a total of twelve months. All patients received education on lifestyle modification. The treatment groups did not differ with regard to mean age±SD (I: 60±9 years vs. C: 57±11 years), mean BMI±SD (I: 33.8±4.6 kg/m2 vs. C: 33.6±4.0 kg/m2) or proportion of males (I: 91% vs. C: 94%). The proportion of patients with fibrosis or cirrhosis at baseline. was not reported. The primary outcome measure was a two-point reduction in NAS without worsening of fibrosis.

Part I: pioglitazone

Results

Cirrhosis, HCC, Decompensation

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation.

Steatosis

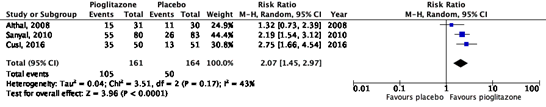

All studies reported on the outcome measure steatosis, which was defined as an improvement of ≥ 1 on a 4-point scale, developed by Brunt (1999). In total, 105/161 (65%) patients in the intervention group showed improvement in steatosis, compared to 50/164 (30%) patients in the placebo group (Figure 1). The risk ratio (95%CI) is 2.07 (1.45 to 2.97), in favor of intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

The studies by Aithal (2008) and Sanyal (2010) also reported the number of patients with deterioration of steatosis, which were 1/31 (3%) patients in the intervention group and 3/30 (10%) patients in the control group of the study by Aithal (2008). For the study by Sanyal (2010), these numbers were 3/80 (4%) and 17/83 (21%) respectively. For Sanyal (2010), the risk ratio (95%CI) is 0.18 (0.06 to 0.60), in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Forest plot of the comparison of pioglitazone vs. placebo on the reduction of steatosis in patients with MASH.

MASH (NAS-score)

Two studies reported on the outcome measure NAS-score, measured as percentage of patients with improvement (reduction) ≥ 2 points on the scale by Brunt (1999), without worsening of fibrosis (Sanyal, 2010; Cusi, 2016). In the study of Sanyal (2010), improvement of NAS-score occurred in 65/80 (81%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 41/83 (50%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.64 (1.29 to 2.09), in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. In the study of Cusi (2016), improvement of NAS-score occurred in 29/50 (58%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 9/51 (7%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 3.29 (1.74 to 6.22), in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. The study of Sanyal (2010) also reported the number of patients with deterioration of NAS-score, which were 7/80 (9%) patients in the intervention group and 26/83 (31%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 0.28 (0.13 to 0.61), in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant.

In addition, the studies by Sanyal (2010) and Cusi (2016) also reported on MASH resolution. Sanyal (2010) reported MASH resolution as absence of MASH after 96 weeks. MASH resolution occurred in 38/80 (47%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 17/83 (21%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 2.32 (1.43 to 3.76), in favor of intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant. Cusi (2016) defined MASH resolution as absence of MASH (measured by biopsy) after 18 months of therapy in patients with definite MASH at baseline. MASH resolution occurred in 26/50 (71%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 10/51 (19%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 2.65 (1.43 to 4.91), in favor of intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Fibrosis

One study reported on the outcome measure fibrosis, without deterioration of MASH. This outcome was defined as an improvement of ≥ 1 on a 4-point scale, developed by Brunt (1999)(Cusi, 2016). Fibrosis improved in 20/50 (40%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 13/51 (25%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.57 (0.88 to 2.80) in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant.

Two other studies also reported on fibrosis as an improvement of ≥ 1 on a 4-point scale, developed by Brunt (1999). However, in both studies it was not reported whether MASH deteriorated. In the study by Aithal (2008), fibrosis improvement was observed in 9/31 (29%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 6/30 (20%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.45 (0.59 to 3.58) in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. The study by Sanyal (2010) reported fibrosis improvement in 35/80 (44%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 26/83 (31%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.40 (0.93 to 2.09) in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. Besides, the studies of Aithal (2008) and Sanyal (2010) also reported the number of patients with deterioration of fibrosis. For the study of Aithal (2008), deterioration of fibrosis took place in 0/31 (0%) patients in the intervention group and 6/30 (20%) patients in the control group. For the study of Sanyal (2010), these numbers were 14/80 (17%) patients and 18/83 (22%) patients respectively. For Sanyal (2010), the risk ratio (95%CI) is 0.81 (0.43 to 1.51), in favor of the intervention group, which is not considered clinically relevant.

(serious) Adverse events

All studies reported on the outcome measure (serious) adverse events. These adverse events varied widely between studies, study groups and within study groups (Table 1). Aithal (2008) reported a total of 19 adverse events in the intervention group (n = 37), compared to 30 adverse events in the control group (n = 37). Sanyal (2010) reported a total of 43 adverse events in the intervention group (n = 80), compared to 50 adverse events in the control group (n = 83). The study of Cusi (2016) reported 118 adverse events in the intervention group (n = 50), compared to 120 events in the control group (n = 51). Details of the adverse events can be found in Table 1 and the original articles of the individual studies. No effect measures have been calculated due to absence of data on the number of patients in which the reported adverse events took place.

Table 1. Reported adverse effects (plus categories) of included studies which investigated the effect of pioglitazone in patients with MASH.

|

Study |

Adverse events |

|

Aithal, 2008 |

Intervention (pioglitazone): Digestive system (n = 5), skin (n = 4), head/neck (n = 3), nervous system (n = 2), musculoskeletal (n = 4), genitourinary system (n = 1)

Control: Digestive system (n = 9), skin (n = 5), head/neck (n = 1), cardiorespiratory system (n = 5), nervous system (n = 6), musculoskeletal (n = 4) |

|

Sanyal, 2010 |

Intervention (pioglitazone): Mild (n = 25), moderate (n = 16), severe (n = 2)

Control: Mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 20), severe (n = 10) |

|

Cusi, 2016 |

Intervention (pioglitazone): Mild events: 91 (details in original article) Severe events: Cardiovascular (n = 12), gastrointestinal (n = 1), endocrinologic (n = 5), neurologic (n = 3) gynecologic (n = 1), urologic (n = 1), hematologic (n = 2), other (n = 2)

Control: Mild events: 95 (details in original article) Severe events: Cardiovascular (n = 5), gastrointestinal (n = 2), endocrinologic (n = 10), neurologic (n = 4), urologic (n = 1), hematologic (n = 1), other (n = 3) |

Quality of life

One study reported on the outcome measure quality of life, measured as mean change in SF-36 score for the physical and the mental component (Sanyal, 2010). For the physical component, the mean change was -0.9 and -0.3 for respectively the intervention group (n = 80) and the control group (n = 83). For the mental component, the mean change was -1.9 and +0.4 for respectively the intervention and the control group. No standard deviations were reported in the study.

Level of evidence of the literature

Steatosis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure steatosis came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to low, because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment, unclear role of funding source and per protocol analysis in one study (Aithal, 2008), downgraded one level). Furthermore, the optimal information size (OIS) was not reached (imprecision, downgraded one level).

MASH (NAS-score)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure MASH (NAS-score) came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to low because of study limitations (risk of bias) and of number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment and unclear role of funding source, downgraded one level). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed one of the thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded one level).

Fibrosis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure fibrosis came from a RCT and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low because of applicability (indirectness) and number of included patients (imprecision). The study included only patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (indirectness, downgraded one level). Furthermore, only one small study could be included in the analysis (imprecision, downgraded two levels).

Cirrhosis, HCC, Decompensation

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation.

Adverse events

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to low because of study limitations (risk of bias) and of number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment and unclear role of funding source, downgraded one level). Furthermore, the optimal information size (OIS) was not reached (imprecision, downgraded one level).

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life came from a RCT and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias) and of number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment and unclear role of funding source, downgraded one level). Furthermore, the evidence came only from one small study (serious imprecision, downgraded two levels).

Conclusions

Steatosis

|

Low GRADE |

Pioglitazone may result in a reduction of steatosis when compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Sources: Aithal, 2008; Sanyal, 2010; Cusi, 2016 |

MASH (NAS-score)

|

Low GRADE |

Pioglitazone may result in a decrease in NAS-score when compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010; Cusi, 2016 |

Fibrosis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of pioglitazone on fibrosis compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Sources: Cusi, 2016 |

Cirrhosis, HCC, Decompensation

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of pioglitazone on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation in patients with MASH. |

(serious) Adverse events

|

Low GRADE |

Pioglitazone may result in little to no difference in (serious) adverse events compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Sources: Aithal, 2008; Sanyal, 2010; Cusi, 2016 |

Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of pioglitazone on quality of life compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010 |

Part II: vitamin E

Results

Steatosis

All studies reported on the outcome measure steatosis, which was defined as an improvement of ≥ 1 on a 4-point scale, developed by Brunt (1999). In the study of Sanyal (2010) 45/80 (54%) patients in the intervention group showed improvement of steatosis, compared to 26/83 (31%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.80 (1.24 to 2.61), in favor of intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

The study also reported the number of patients with deterioration of steatosis, which were7/84 (8%) patients in the intervention group and 17/83 (21%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 0.41 (0.18 to 0.93), in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. For the study of Bril (2019) improvement of steatosis took place in 24/36 (68%) patients of the intervention group, compared to 15/32 (46%) patients of the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.54 (1.01 to 2.35), in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant.

MASH (NAS-score)

All studies reported on the outcome measure NAS-score, measured as percentage of patients with improvement (reduction) ≥ 2 points on the scale by Brunt (1999). In the study of Sanyal (2010), improvement of NAS-score occurred in 63/84 (75%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 41/83 (50%) patients from the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.52 (1.18 to 1.95) in favor of intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. The study also reported the number of patients with deterioration of NAS-score, which were 9/84 (11%) patients in the intervention group and 26/83 (31%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 0.34 (0.17 to 0.69) in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. For the study by Bril (2019) improvement of NAS-score occurred in 13/36 (36%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 7/32 (22%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.65 (0.75 to 3.62) in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant.

In addition, all studies also reported on MASH resolution. Sanyal (2010) reported MASH resolution as absence of MASH after 96 weeks. MASH resolution occurred in 30/84 (36%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 17/83 (21%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.74 (1.05 to 2.91), in favor of intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant. The study of Bril (2019) reported MASH resolution as absence of ballooning and inflammation, without worsening of fibrosis. MASH resolution occurred in 14/36 (40%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 5/32 (17%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 2.49 (1.01 to 6.14), in favor of intervention group. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Fibrosis

One study reported on the outcome measure fibrosis with the criterium that deterioration of MASH was absent. This outcome was defined as an improvement of ≥ 1 on a 4-point scale, developed by Brunt (1999)(Bril, 2019). Improvement of fibrosis was observed in 19/36 (50%) patients in the intervention group, compared to 10/32 (30%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.69 (0.93 to 3.08) in favor of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant.

The study by Sanyal (2010) also reported on fibrosis as an improvement of ≥ 1 on a 4-point scale, developed by Brunt (1999). However, the criterium for no further deterioration of MASH in case of improvement of fibrosis, was not reported. In the study 34/84 (41%) patients in the intervention group showed improvement of fibrosis, compared to 26/83 (31%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 1.29 (0.86 to 1.95) in favor of intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. The study also reported the number of patients with deterioration of fibrosis, which were 16/83 (19%) patients in the intervention group and 18/83 (22%) patients in the control group. The risk ratio (95%CI) is 0.89 (0.49 to 1.62), in favor of the intervention group, which is not considered clinically relevant.

Cirrhosis, HCC, Decompensation

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation.

(serious) Adverse events

All studies reported on the outcome (serious) adverse events. These adverse events varied widely between studies, study groups and within study groups (Table 2). Sanyal (2010) reported a total of 51 adverse events in the intervention group (n = 84), compared to 50 in the control group (n = 83). The study reports life-threatening (intervention: n = 4) and death (intervention: n = 1) separately. Bril (2010) reported a total of 51 adverse events in the intervention group (n = 36), compared to 48 events in the control group (n = 32). Details of the adverse events can be found in Table 2 and the original articles of the individual studies.

Table 2. Reported adverse effects (plus categories) of included studies which investigated the effect of vitamin E in patients with MASH.

|

Study |

Adverse events |

|

Sanyal, 2010 |

Intervention (vitamin E): Mild (n = 24), moderate (n = 19), severe (n = 7), life-threatening/disabling (n = 4), death (n = 1)

Control: Mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 20), severe (n = 10) |

|

Bril, 2019 |

Intervention (vitamin E): Cardiovascular (n = 8 of which two died), gastrointestinal (n = 7), respiratory (n = 10), endocrinologic (n = 12), gynecologic (n = 1), infectious diseases (n = 2), urologic (n = 1), other (n = 10)

Control: Cardiovascular (n = 4), gastrointestinal (n = 10), respiratory (n = 8), endocrinologic (n = 8), gynecologic (n = 1), other (n = 7) |

Quality of life

One study reported on the outcome measure quality of life, measured as mean change in SF-36 score for the physical and the mental component (Sanyal, 2010). For the physical component, the mean change was +0.4 and -0.3 for respectively the intervention group (n = 84) and the control group (n = 83). For the mental component, the mean change was -0.5 and +0.4 for respectively the intervention and the control group. No standard deviations were reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

Steatosis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure steatosis came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to low, because of study limitations (risk of bias) and number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment, unclear role of funding source and infrequent loss to follow-up, downgraded one level). Furthermore, the optimal information size (OIS) was not reached (imprecision, downgraded one level).

MASH (NAS-score)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure MASH (NAS-score) came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to low because of study limitations (risk of bias) and of number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment, unclear role of funding source and infrequent loss to follow-up, downgraded one level). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed one of the thresholds for clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded one level).

Fibrosis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure fibrosis came from an RCT and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias), applicability (indirectness) and of number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (infrequent loss to follow-up (attrition bias), downgraded one level). Furthermore, the study only included diabetic patients (indirectness, downgraded one level. Furthermore, only one small study could be included in the analysis (imprecision, downgraded two levels).

Cirrhosis, HCC, Decompensation

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation.

Adverse events

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to low because of study limitations (risk of bias) and of number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment, unclear role of funding source and infrequent loss to follow-up, downgraded one level). Furthermore, the optimal information size (OIS) was not reached (imprecision, downgraded one level).

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure quality of life came from a RCT and therefore started as high. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias) and of number of included patients (imprecision). There was risk of bias (unclear allocation concealment and unclear role of funding source, downgraded one level). Furthermore, the evidence came only from one small study (serious imprecision, downgraded two levels).

Conclusions

Steatosis

|

Low GRADE |

Vitamin E may result in a reduction of steatosis when compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010; Bril, 2019 |

MASH (NAS-score)

|

Low GRADE |

Vitamin E may result in an decrease in NAS-score when compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010; Bril, 2019 |

Fibrosis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of vitamin E on fibrosis compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Bril, 2019 |

Cirrhosis, HCC, Decompensation

|

No GRADE |

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation. Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn on the effect of vitamin E on the outcome measures cirrhosis, HCC and decompensation in patients with MASH. |

(serious) Adverse events

|

Low GRADE |

Vitamin E may result in little to no difference in (serious) adverse events compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010; Bril, 2019 |

Quality of life

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of vitamin E on quality of life compared with placebo in patients with MASH.

Source: Sanyal, 2010 |

Part III: obeticholic acid

Results

All outcome measures

None of the studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Level of evidence of the literature

All outcome measures

No study could be included on the effect of obeticholic acid in patients with MASH. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn on the effect of obeticholic acid on the outcome measures steatosis, MASH resolution, NAS, fibrosis, cirrhosis, HCC, decompensation, (serious) adverse events and quality of life in patients with MASH.

Conclusions

All outcome measures

|

No GRADE |

No phase 3-study could be included on the effect of obeticholic acid in patients with MASH. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn on the effect of obeticholic acid on the outcome measures steatosis, MASH resolution, NAS, fibrosis, cirrhosis, HCC, decompensation, (serious) adverse events and quality of life in patients with MASH. |

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the (un)desirable effects of treatment with obeticholic acid, vitamin E, pioglitazon, compared with placebo or no treatment, in adults with MASH (F1-F4)?

P (patients): Adults with MASH (F1-F4)

I (intervention): Obeticholic acid, vitamine E, pioglitazon

C (comparison): Placebo, no medical treatment

O (outcomes): Steatosis, MASH, fibrosis, cirrhosis, HCC, decompensation, (serious) adverse events, quality of life

As is mentioned in the introduction, we focused the literature search and analysis on medical treatments that has been studied in patients with MASH, in Phase 3-studies.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered fibrosis as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and steatosis, MASH, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), decompensation, (serious) adverse events, quality of life as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- MASH: based on histology (i.e. NAS Score)

- Fibrosis: improvement in fibrosis with no deterioration of MASH

- Other outcome measures: the working group used the definitions of the outcome measures as defined in the included studies.

The working group defined the GRADE standard limit of 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR <0.8 or >1.25) and 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. For the outcome measure hepatocellular carcinoma a difference of at least 10% in relative risk was defined as a clinically (patient) important difference (RR < 0.91/RR > 1.10).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 16 June 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 325 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: (systematic reviews of) ≥ Phase-3 RCTs on the effects of treatment with obeticholic acid, vitamin E or pioglitazone in adults with MASH (F1-F4). 50 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 46 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included.

Results

Four studies were included in the analysis of the literature: three studies on the effectiveness of pioglitazone (Aithal, 2008; Sanyal, 2010 and Cusi, 2016) and two on the effectiveness of vitamin E (Bril, 2019; Sanyal, 2010 about both pioglitazone and vitamin E). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence table. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias table.

Referenties

- Aithal, G. P., Thomas, J. A., Kaye, P. V. et al (2008). Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in nondiabetic subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology, 135(4), 1176-1184.

- Bril, F., Biernacki, D. M., Kalavalapalli, S. et al (2019). Role of vitamin E for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes care, 42(8), 1481-1488.

- Brunt, E. M., Janney, C. G., Di Bisceglie, A. M., Neuschwander-Tetri, B. A., & Bacon, B. R. (1999). Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. The American journal of gastroenterology, 94(9), 2467-2474.

- Chalasani, N., Younossi, Z., Lavine, J. E. et al (2018). The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology, 67(1), 328-357.

- European Association for the Study of The Liver, & European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD. (2016). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Obesity facts, 9(2), 65-90.

- Cusi, K., Orsak, B., Bril, F. et al (2016). Long-term pioglitazone treatment for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine, 165(5), 305-315.

- European Association for the Study of The Liver, & European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD. (2016). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Obesity facts, 9(2), 65-90.

- Levin, D., Bell, S., Sund, R. et al & Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group and the Diabetes and Cancer Research Consortium. (2015). Pioglitazone and bladder cancer risk: a multipopulation pooled, cumulative exposure analysis. Diabetologia, 58, 493-504.

- Lewis, J. D., Ferrara, A., Peng, T. et al (2011). Risk of bladder cancer among diabetic patients treated with pioglitazone: interim report of a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes care, 34(4), 916-922.

- Newsome, P. N., Buchholtz, K., Cusi, K. et al (2021). A placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous semaglutide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(12), 1113-1124.

- Sanyal, A. J., Chalasani, N., Kowdley, K. V. et al (2010). Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(18), 1675-1685.

- Schernthaner, G., & Chilton, R. J. (2010). Cardiovascular risk and thiazolidinedioneswhat do meta?analyses really tell us?. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 12(12), 1023-1035.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What are the (un)desirable effects of treatment with obeticholic acid, vitamin E, pioglitazon, compared with placebo or no treatment, in adults with MASH (F1-F4)?

Evidence table for intervention studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Aithal, 2008 |

Type of study: RCT (parallel, double-blind)

Country: United Kingdom

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding by several pharmaceutical companies. No further conflicts of interest reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Nondiabetic patients aged 18-70 years with histology-proven MASH.

Exclusion criteria: History of alcohol excess, presence of other liver diseases, use of drugs associated with fatty live, use of lipid lowering if the dose had been stable for < 3 months, weight-reduction medication, pregnant or lactating women, current or previous heart failure, and renal impairment.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 37 Control: 37

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age (range): I: 52 (28-71) C: 55 (27-73)

Sex: I: 70% M C: 51% M

Mean BMI (SD) I: 29.8 (± 3.0) C: 30.8 (± 4.1)

N patients with fibrosis at baseline (stage 1-4) I: 23 (74%) C: 25 (83%)

N patients with cirrhosis at baseline (stage 1-4) Not reported

Groups are largely comparable at baseline, although difference in gender ratios is noteworthy. |

30 mg pioglitazone; once daily + hypocaloric diet (500 kcal less + 30-40 minutes moderate exercise for ≥ 5 days per week, for 12 months.

|

Placebo; once daily + hypocaloric diet (500 kcal less + 30-40 minutes moderate exercise for ≥ 5 days per week, for 12 months

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 6 (16%) patients from the intervention group withdrew from the study. Reasons: Personal reasons (n = 2), found to be diabetic after randomization (n = 2), diarrhoea and vomiting (n = 1), headaches and epistaxis (n = 1)

Control: 7 (19%) patients from the intervention group withdrew from the study. Reasons: Personal reasons (n = 3), right upper-quadrant pain (n = 1), weight gain (n = 1), rash (n = 1), vertigo (n = 1)

Incomplete outcome data: See ‘Loss-to-follow-up’ above No further incomplete outcome data reported.

|

Steatosis, fibrosis, adverse events

Steatosis: n (%) of patients with a change of ≥ 1 of 4-point scale, intervention vs. placebo Improvement: 15 (48%) vs. 11 (37%) Deterioration: 1 (3%) vs. 3 (10%)

Fibrosis: n (%) of patients with a change of ≥ 1 of 4-point scale, intervention vs. placebo Improvement: 9 (29%) vs. 6 (20%) Deterioration: 0 (0%) vs. 6 (20%)

Adverse events: Intervention: Digestive system (n = 5), skin (n = 4), head/neck (n = 3), nervous system (n = 2), musculoskeletal (n = 4), genitourinary system (n = 1)

Control: Digestive system (n = 9), skin (n = 5), head/neck (n = 1), cardiorespiratory system (n = 5), nervous system (n = 6), musculoskeletal (n = 4) |

Unclear why the study used a ‘relatively low dose’ of pioglitazone, as stated by the authors.

Power calculation required 33 patients in each study arm for analysis, which was not met.

Pioglitazone led to significant weight gain compared to placebo (not visible in this table), although compliance to the intervention (including diet and exercise) is not stated to differ significantly between the groups; a possible explanation is not given.

Caution is needed with respect to generalizability, as all included patients were nondiabetic. Funding source is of some concern. |

|

Sanyal, 2010 |

Type of study: RCT (parallel, double-blind)

Country: United States

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding by pharmaceutical company Takeda Pharmaceuticals (amongst others), authors received reimbursements and consulting fees from different pharmaceutical companies. One author received fees for serving on the data and safety monitoring board for Takeda Pharmaceuticals. |

Inclusion criteria: Nondiabetic adult patients, definite or possible steatohepatitis with an activity score of ≥ 5 or definite steatohepatitis (confirmed by two pathologists) with an activity score of 4, score for hepatocellular ballooning ≥ 1

Exclusion criteria: Excessive alcohol consumption (women >20 g/day, men >30 g/day) for at least 3 consecutive months during the previous 5 years, presence of cirrhosis, hepatitis C or other liver diseases, heart failure (New York Heart Association class II to IV), use of drugs known to cause steatohepatitis.

N total at baseline: Intervention A (pioglitazone): 80

Intervention B (vitamin E): 84

Control: 83

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age (SD): IA: 47 (± 12.6) IB: 47 (± 12.1) C: 45 (± 11.2)

Sex: IA: 41% M IB: 38% M C: 42% M

Mean BMI (SD): IA: 34 (± 6) IB: 34 (± 7) C: 35 (± 7)

N patients with fibrosis at baseline (stage 1-4) IA: 69 (86%) IB: 70 (83%) C: 67 (81%)

N patients with cirrhosis at baseline IA: 1 IB: 1 C: 3

Groups are largely comparable at baseline. |

Intervention A: 30 mg pioglitazone + vitamin E–like placebo; once daily + recommendations about lifestyle changes and diet, for 96 weeks

Intervention B: 800 IU vitamin E (RRR-α-tocopherol) + pioglitazone-like placebo; once daily + recommendations about lifestyle changes and diet, for 96 weeks |

Placebo (of both pioglitazone and vitamin E); once daily + recommendations about lifestyle changes and diet, for 96 weeks

|

Length of follow-up: 120 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention A: 14 patients (18%) stopped treatment before 96 weeks. Reasons: withdrawment by physician (n = 1), loss to follow-up (n = 11), decline to participate (n = 2)

Intervention B: 6 patients (7%) stopped treatment before 96 weeks. Reasons: withdrawment by physician (n = 3), loss to follow-up (n = 2), decline to participate (n = 1)

Control: 12 patients (14%) stopped treatment before 96 weeks. Reasons: withdrawment by physician (n = 1), loss to follow-up (n = 11)

Incomplete outcome data: See ‘Loss-to-follow-up’ |

Steatosis, NAS, fibrosis, adverse events, quality of life

Steatosis: n (%) of patients with a change of ≥ 1 of 4-point scale Improvement: IA: 55 (69%), IB: 45 (54%), C: 26 (31%) Deterioration: IA: 3 (4%), IB: 7 (8%), C: 17 (21%)

MASH (MASH resolution): n (%) of patient with absence of MASH 96 weeks after baseline IA: 38 (47%), IB: 30 (36%), C: 17 (21%)

MASH (NAS): n (%) of patients with a change of ≥ 2 points of NAS (without worsening of fibrosis) on a 8-point scale Improvement: IA:65 (81%) , IB: 63 (75%), C: 41 (50%) Deterioration: IA: 7 (9%), IB: 9 (11%), C: 26 (31%)

Fibrosis: n (%) of patients with a change of ≥ 1 of 4-point scale Improvement: IA: 35 (44%), IB: 34 (41%), C: 26 (31%) Deterioration: IA: 14 (17%), IB 16 (19%), C: 18 (22%)

Adverse events: IA: Mild (n = 25), moderate (n = 16), severe (n = 2) IB: Mild (n = 24), moderate (n = 19), severe (n = 7), life-threatening (n = 4), death (n = 1) C: Mild (n = 20), moderate (n = 20), severe (n = 10)

Quality of life: Mean change in SF-36 score, physical component IA vs. C: -0.9 vs. -0.3 IB vs. C: +0.4 vs. -0.3

Mean change in SF-36 score, mental component IA vs. C: -1.9 vs. +0.4 IB vs. C: -0.5 vs. +0.4 |

Patients with incomplete outcome data, which is a large group, were included in the categories ‘no improvement’ for each outcome; no explanation for this method was given. Results are not easily generalizable as only nondiabetic patients are included. Funding source and conflicts of interest are of some concern. |

|

Cusi, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT (parallel, double-blind)

Country: United States

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funding by non-profit organizations. Main author received grants from pharmaceutical companies in the past. |

Inclusion criteria: Adults with histology-proven MASH and either prediabetes or diabetes mellitus type 2.

Exclusion criteria: Use of thiazolidinediones or vitamin E; other causes of liver disease or abnormal laboratory results; type 1 diabetes mellitus; or severe heart, hepatic or renal disease.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 51

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age (SD): I: 52 (± 10) C: 49 (± 11)

Sex: I: 72% M C: 69% M

Mean BMI (SD): I: 34.3 (± 4.8) C: 34.5 (± 4.8)

N patients with fibrosis at baseline (stage 1-4) I: 35 (70%) C: 31 (61%)

N patients with cirrhosis at baseline (stage 1-4) Not reported

Groups are largely comparable at baseline. |

30 mg pioglitazone (45 mg after two months); once daily + hypocaloric diet (500 kcal deficit, for 18 months

|

Placebo; once daily + hypocaloric (500 kcal deficit, for 18 months

|

Length of follow-up: 18 months (+ open label phase of 18 months with pioglitazone, separate analysis)

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 9 (18%) Reasons: Consent withdrawn or unclear

Control: 9 (18%) Reasons: Consent withdrawn, adverse event or unclear

Incomplete outcome data: See ‘Loss-to-follow-up’ above No further incomplete outcome data reported.

|

Steatosis, MASH resolution, NAS, fibrosis, adverse events

Steatosis: n (%) of patients with a reduction of ≥ 1 of 4-point scale, intervention vs. placebo 35 (71%) vs. 13 (26%)

MASH (MASH resolution): n (%) of patient with absence of MASH with definite MASH at baseline after 18 months of therapy, intervention vs. placebo 26 (51%) vs. 10 (19%)

MASH (NAS): n (%) of patients with a reduction of ≥ 2 points of NAS (without worsening of fibrosis) on a 8-point scale, intervention vs. placebo 29 (58%) vs. 9 (17%)

Fibrosis: n (%) of patients with improvement of ≥ 1 of 4-point scale (without worsening of MASH), intervention vs. placebo 20 (39%) vs. 13 (25%)

Adverse events: Mild adverse events: Intervention: 91 Control: 9595

Moderate to severe events: Intervention: Cardiovascular (n = 12), gastrointestinal (n = 1), endocrinologic (n = 5), neurologic (n = 3) gynecologic (n = 1), urologic (n = 1), hematologic (n = 2), other (n = 2) Control: Cardiovascular (n = 5), gastrointestinal (n = 2), endocrinologic (n = 10), neurologic (n = 4), urologic (n = 1), hematologic (n = 1), other (n = 3) |

Number of mild adverse events seems quite high, although evenly spread among the two groups.

Baseline biopsies were reread after the end of the study to patients with definite MASH, defined as zone 3 accentuation of macrovesicular steatosis (any grade), hepatocellular ballooning (any degree), and lobular inflammatory infiltrates (any amount). Appendix reveals that at least seven patients from the intervention group and six patients from the control group were not considered as patients with definite MASH.

Inclusion of only patients with T2D or prediabetes make the results less generalizable. |

|

Bril, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT (parallel, double-blind)

Country: Unites States

Funding and conflicts of interest: No financial support by pharmaceutical companies. Authors report to have no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients aged 18-70 with diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and histology confirmed MASH.

Exclusion criteria: Use of thiazolidinediones, glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, or vitamin E; other etio-logies of liver disease, drugs that can produce hepatic steatosis (amiodarone, tamoxifen, methotrexate, etc.); type 1 diabetes mellitus; or severe heart, pulmonary, or renal disease

N total at baseline5 Intervention: 36 Control: 32

Important prognostic factors2: Mean age (SD): I: 60 (± 9) C: 57 (± 11)

Sex: I: 91% M C: 94% M

Mean BMI (SD): I: 33.8 (± 4.6) C: 33.6 (± 4.0)

N patients with fibrosis at baseline (stage 1-4) Not reported

N patients with cirrhosis at baseline (stage 1-4) Not reported

Groups are largely comparable at baseline. |

400 IU vitamin E; twice daily + education on lifestyle modification, for 18 months

|

Placebo; twice daily + education on lifestyle modification, for 18 months

|

Length of follow-up: 18 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 3 (8%) patients discontinued treatment Reasons: Death (n = 2), loss to follow-up (n = 1)

Control: 8 (25%) patients discontinued treatment Reasons: withdrew consent (n = 4), decision of physician (n = 1), elevated ALT (n = 1), loss to follow-up (n = 1)

Incomplete outcome data: See ‘Loss-to-follow-up’ above. Two extra patients refused to take a second live biopsy. Unclear to which study arm they belonged.

|

Steatosis, MASH resolution, NAS, fibrosis, adverse events

Steatosis: n (%) of patients with a reduction of ≥ 1 of 4-point scale, intervention vs. placebo 24 (68%) vs. 15 (46%)

MASH (MASH resolution)6: n (%) of patients with absence of ballooning and inflammation and no worsening of fibrosis, intervention vs. placebo 14 (40%) vs. 5 (17%)

MASH (NAS)6: n (%) of patients with a reduction of ≥ 2 points of NAS (without worsening of fibrosis) on a 8-point scale, intervention vs. placebo 13 (36%) vs. 7 (22%)

Fibrosis: n (%) of patients with a reduction of ≥ 1 of 4-point scale (without worsening of MASH), intervention vs. placebo 19 (50%) vs. 10 (30%)

Adverse events: Intervention: Cardiovascular (n = 8 of which two died), gastrointestinal (n = 7), respiratory (n = 10), endocrinologic (n = 12), gynecologic (n = 1), infectious diseases (n = 2), urologic (n = 1), other (n = 10) Control: Cardiovascular (n = 4), gastrointestinal (n = 10), respiratory (n = 8), endocrinologic (n = 8), gynecologic (n = 1), other (n = 7) |

Loss to follow-up in control group is relatively high compared to the intervention group.

Difference in resolution of MASH between intervention and control group is non-significant for analyses according to authors (level of significance: p = 0.025)

Results should be viewed with caution due to inclusion of only T2D patients, almost exclusively male. |

Risk of bias tables

Risk of bias table for intervention studies

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Aithal, 2008 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization was performed with a computer program, with inclusion of anthropometric data, blood count, standard liver chemistry etc. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients were randomly allocated to either pioglitazone or placebo. No specific information on allocation.

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients, data collectors and analysts blinded. No information on health care workers (if present), but these are likely to have a minor role. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss-to-follow-up was 16% (n = 6) in intervention group and 19% (n = 7) in control group. Reasons for follow-up vary between and within the study groups. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes stated in methods were reported.

|

Probably no;

Reason: Funding by several pharmaceutical companies, unclear whether these had had an active role in the study and whether a restricted or unrestricted grant was given. Analysis was a per-protocol analysis. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) Reasons: role of funding source not fully clear, allocation concealment not fully clear, no use of ITT analysis.

|

|

Sanyal, 2010 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization was performed with a computer program. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients were randomly allocated to either pioglitazone, vitamin E or placebo. No specific information on allocation. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Study is ‘double-blind’, although no explanation on blinding method is given. Placebo and intervention pills for pioglitazone and vitamin E had a similar appearance. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Loss-to-follow-up was 7-17%, but several patients still took baseline and end-biopsies (full outcome data). Reasons for loss to follow-up are comparable among study groups. Patients with incomplete outcome data, were included in the categories ‘no improvement’ for each outcome; no explanation for this method is given. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes stated n methods were reported.

|

Probably no;

Reason: Funding by several pharmaceutical companies. One author performed several tasks for one of the funding sources. Unclear whether the funding sources had an active role in the study and whether a restricted or unrestricted grant was given. |

Some concerns (all outcome measures) Reasons: role of funding source not fully clear, allocation concealment not fully clear |

|

Cusi, 2016 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization was performed with a computer program. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients were randomly allocated to either pioglitazone or placebo. Allocation by research pharmacist, not visible for investigators. Placebo and intervention pills for pioglitazone and vitamin E had a similar appearance. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients, health care providers, investigators and outcome assessors blinded. Data collection probably took place by the investigators. |

Definitely yes:

Reason: Loss-to-follow-up was 18% in both treatment arms with similar reasons. Multiple imputation was used for missing data. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes stated in methods were reported.

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

LOW (all outcome measures) Reasons: low risk of bias for all aspects |

|

Bril, 2019 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization was performed with a computer program. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Patients were randomly allocated to either vitamin E or placebo via a computer program. Allocation by research pharmacist, not visible for investigators. Placebo and intervention pills for vitamin E had a similar appearance. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Study is ‘double-blind’, although no clear explanation of blinding method is given. Patients and outcome assessors blinded. Placebo and intervention pills for pioglitazone and vitamin E had a similar appearance. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Large difference in loss-to-follow-up between two treatment arms (I: 8%, C: 25%) with varying reasons for discontinuing study, although study population is relatively small. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes stated in methods were reported.

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted. |

SOME CONCERN (all outcome measures) Reasons: low risk of bias for all aspects. However, there was difference in loss to follow-up between study groups. This might be less important due to small study population.

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Kumar J, Memon RS, Shahid I, Rizwan T, Zaman M, Menezes RG, Kumar S, Siddiqi TJ, Usman MS. Antidiabetic drugs and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review, meta-analysis and evidence map. Dig Liver Dis. 2021 Jan;53(1):44-51. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.08.021. Epub 2020 Sep 8. PMID: 32912770. |

No combination of correct intervention with MASH patients. |

|

Xu R, Tao A, Zhang S, Deng Y, Chen G. Association between vitamin E and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015 Mar 15;8(3):3924-34. PMID: 26064294; PMCID: PMC4443128. |

outdated SR |

|

Singh S, Khera R, Allen AM, Murad MH, Loomba R. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2015 Nov;62(5):1417-32. doi: 10.1002/hep.27999. Epub 2015 Oct 1. PMID: 26189925. |

outdated SR |

|

Sawangjit R, Chongmelaxme B, Phisalprapa P, Saokaew S, Thakkinstian A, Kowdley KV, Chaiyakunapruk N. Comparative efficacy of interventions on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Aug;95(32):e4529. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004529. PMID: 27512874; PMCID: PMC4985329. |

outdated SR |

|

Malik A, Nadeem M, Amjad W, Farooq U, Malik S, Malik M. COMPARATIVE NETWORK META-ANALYSIS FOR EFFICACY OF PHARMACOLOGICAL MODALITIES FOR NON-ALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE(NAFLD). J Gastrol. 2021 May 1; 160: 840. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(21)02735-9. |

Full article not available |

|

Ahmed NR, Kulkarni VV, Pokhrel S, Akram H, Abdelgadir A, Chatterjee A, Khan S. Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of Obeticholic Acid and Semaglutide in Patients With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022 May 8;14(5):e24829. doi: 10.7759/cureus.24829. PMID: 35693370; PMCID: PMC9173657. |

Phase II studies Included |

|

Hameed B, Terrault NA, Gill RM, Loomba R, Chalasani N, Hoofnagle JH, Van Natta ML; NASH CRN. Clinical and metabolic effects associated with weight changes and obeticholic acid in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Mar;47(5):645-656. doi: 10.1111/apt.14492. Epub 2018 Jan 14. PMID: 29333665; PMCID: PMC5931362. |

Results from interim-analyse of FLINT trial |

|

Polyzos SA, Mantzoros CS. Adiponectin as a target for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with thiazolidinediones: A systematic review. Metabolism. 2016 Sep;65(9):1297-306. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.05.013. Epub 2016 May 27. PMID: 27506737. |

Outdated SR |

|

Mahady SE, Webster AC, Walker S, Sanyal A, George J. The role of thiazolidinediones in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis - a systematic review and meta analysis. J Hepatol. 2011 Dec;55(6):1383-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.016. Epub 2011 Apr 14. PMID: 21703200. |

Outdated SR |

|

Perumpail BJ, Li AA, John N, Sallam S, Shah ND, Kwong W, Cholankeril G, Kim D, Ahmed A. The Role of Vitamin E in the Treatment of NAFLD. Diseases. 2018 Sep 24;6(4):86. doi: 10.3390/diseases6040086. PMID: 30249972; PMCID: PMC6313719. |

Narrative review |

|

Yaghoubi M, Jafari S, Sajedi B, Gohari S, Akbarieh S, Heydari AH, Jameshoorani M. Comparison of fenofibrate and pioglitazone effects on patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Dec;29(12):1385-1388. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000981. PMID: 29023319. |

Incorrect control group |

|

Hajiagha Mohammadi A A, Khajeh Jahromi S, Ahmadi Gooraji S, Bastani A. Comparison of the Therapeutic Effects of Melatonin, Metformin and Vitamin E on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Adv Med Biomed Res 2022; 30 (140) :232-240. doi: 10.30699/jambs.30.140.232 |

No difference between MAFLD and MASH patients |

|

Ekhlasi G, Kolahdouz Mohammadi R, Agah S, Zarrati M, Hosseini AF, Arabshahi SS, Shidfar F. Do symbiotic and Vitamin E supplementation have favorite effects in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Res Med Sci. 2016 Nov 2;21:106. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.193178. PMID: 28250783; PMCID: PMC5322689. |

Incorrect outcome measurements |

|

Balmer ML, Siegrist K, Zimmermann A, Dufour JF. Effects of ursodeoxycholic acid in combination with vitamin E on adipokines and apoptosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int. 2009 Sep;29(8):1184-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02037.x. Epub 2009 Apr 28. PMID: 19422479. |

Incorrect intervention (vitamin E with other compound) |

|

Chehrehgosha H, Sohrabi MR, Ismail-Beigi F, Malek M, Reza Babaei M, Zamani F, Ajdarkosh H, Khoonsari M, Fallah AE, Khamseh ME. Empagliflozin Improves Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Diabetes Ther. 2021 Mar;12(3):843-861. doi: 10.1007/s13300-021-01011-3. Epub 2021 Feb 14. PMID: 33586120; PMCID: PMC7882235. |

No difference between MAFLD and MASH patients |

|

Huang JF, Dai CY, Huang CF, Tsai PC, Yeh ML, Hsu PY, Huang SF, Bair MJ, Hou NJ, Huang CI, Liang PC, Lin YH, Wang CW, Hsieh MY, Chen SC, Lin ZY, Yu ML, Chuang WL. First-in-Asian double-blind randomized trial to assess the efficacy and safety of insulin sensitizer in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Hepatol Int. 2021 Oct;15(5):1136-1147. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10242-2. Epub 2021 Aug 12. PMID: 34386935. |

Phase II study |

|

Zang S, Chen J, Song Y, Bai L, Chen J, Chi X, He F, Sheng H, Wang J, Xie S, Xie W, Yang Y, Zhang J, Zheng M, Zou Z, Wang B, Shi J; Chinese NAFLD Clinical Research Network (CNAFLD CRN). Haptoglobin Genotype and Vitamin E Versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in China: A Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial Design. Adv Ther. 2018 Feb;35(2):218-231. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0670-8. Epub 2018 Feb 6. PMID: 29411270. |

Co-intervention (personalized dietary and lifestyle advice) + ongoing study |

|

Siddiqui MS, Van Natta ML, Connelly MA, Vuppalanchi R, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Tonascia J, Guy C, Loomba R, Dasarathy S, Wattacheril J, Chalasani N, Sanyal AJ; NASH CRN. Impact of obeticholic acid on the lipoprotein profile in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2020 Jan;72(1):25-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.006. Epub 2019 Oct 18. PMID: 31634532; PMCID: PMC6920569. |

Incorrect outcome measurements |

|

Gastaldelli A, Harrison SA, Belfort-Aguilar R, Hardies LJ, Balas B, Schenker S, Cusi K. Importance of changes in adipose tissue insulin resistance to histological response during thiazolidinedione treatment of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2009 Oct;50(4):1087-93. doi: 10.1002/hep.23116. PMID: 19670459. |

Incorrect outcome measurements |

|

Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Sanyal AJ, Neuschwander-Tetri BA; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Improvements in Histologic Features and Diagnosis Associated With Improvement in Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Results From the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network Treatment Trials. Hepatology. 2019 Aug;70(2):522-531. doi: 10.1002/hep.30418. Epub 2019 Mar 7. PMID: 30549292; PMCID: PMC6570584. |

Study Includeds results from ongoing study |

|

Kakazu E, Kondo Y, Ninomiya M, Kimura O, Nagasaki F, Ueno Y, Shimosegawa T. The influence of pioglitazone on the plasma amino acid profile in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Hepatol Int. 2013 Jun;7(2):577-85. doi: 10.1007/s12072-012-9395-y. Epub 2012 Aug 14. PMID: 26201790. |

Incorrect outcome measurements |

|

Voican CS, Perlemuter G. Insulin resistance and oxidative stress: two therapeutic targets in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2011 Feb;54(2):388-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.054. Epub 2010 Nov 10. PMID: 21112115. |

Commentary article |

|

Rinella ME, Dufour JF, Anstee QM, Goodman Z, Younossi Z, Harrison SA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Bonacci M, Trylesinski A, Natha M, Shringarpure R, Granston T, Venugopal A, Ratziu V. Non-invasive evaluation of response to obeticholic acid in patients with NASH: Results from the REGENERATE study. J Hepatol. 2022 Mar;76(3):536-548. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.10.029. Epub 2021 Nov 15. PMID: 34793868. |

Interim analysis |

|

Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K, Darland C, Finch J, Hardies J, Balas B, Gastaldelli A, Tio F, Pulcini J, Berria R, Ma JZ, Dwivedi S, Havranek R, Fincke C, DeFronzo R, Bannayan GA, Schenker S, Cusi K. A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 30;355(22):2297-307. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060326. PMID: 17135584. |

Phase II study |

|

Bugianesi E, Gentilcore E, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, David E, Rizzetto M, Marchesini G. A randomized controlled trial of metformin versus vitamin E or prescriptive diet in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 May;100(5):1082-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41583.x. PMID: 15842582. |

Incorrect control group (metformin) |

|

Bell LN, Wang J, Muralidharan S, Chalasani S, Fullenkamp AM, Wilson LA, Sanyal AJ, Kowdley KV, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, McCullough AJ, Bass NM, Diehl AM, Unalp-Arida A, Chalasani N; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Relationship between adipose tissue insulin resistance and liver histology in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a pioglitazone versus vitamin E versus placebo for the treatment of nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis trial follow-up study. Hepatology. 2012 Oct;56(4):1311-8. doi: 10.1002/hep.25805. Epub 2012 Aug 21. PMID: 22532269; PMCID: PMC3432683. |

Includeds results from ongoing study |

|

Anushiravani A, Haddadi N, Pourfarmanbar M, Mohammadkarimi V. Treatment options for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May;31(5):613-617. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001369. PMID: 30920975. |

Incorrect control group (diet) |

|

Blazina I, Selph S. Diabetes drugs for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019 Nov 29;8(1):295. doi: 10.1186/s13643-019-1200-8. PMID: 31783920; PMCID: PMC6884753. |

Focus on diabetes drugs |

|

Mantovani A, Byrne CD, Scorletti E, Mantzoros CS, Targher G. Efficacy and safety of anti-hyperglycaemic drugs in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with or without diabetes: An updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab. 2020 Nov;46(6):427-441. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2019.12.007. Epub 2020 Jan 7. PMID: 31923578. |

Focus on anti-hyperglycaemic drugs |

|