Bariatrische chirurgie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van bariatrische chirurgie in de behandeling van patiënten met MASLD, en in het bijzonder van patiënten met MASH met ernstige leverfibrose?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg bariatrische chirurgie bij patiënten met MASLD/MASH en gevorderde of ernstige fibrose met een BMI > 35 kg/m2 en bij wie leefstijlinterventies onvoldoende effect hebben gehad.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van bariatrische chirurgie bij patiënten met MASLD. Resolutie van MASH en ≥ 1 fibrosestadium afname en lever-gerelateerde complicaties waren gedefinieerd als cruciale uitkomstmaten. Er zijn voor deze vraag uitsluitend observationele studies gevonden, waarbij sprake is van heterogeniteit. Op basis van de beschikbare literatuur is de bewijskracht voor deze cruciale uitkomstmaten daarom beoordeeld als zeer laag, waardoor geen richting gegeven kan worden aan de besluitvorming.

Voor patiënten met obesitas en MASLD/MASH is momenteel alleen van leefstijlinterventies een positief effect op de lever en geassocieerde cardiometabole complicaties beschreven. Hoewel dieet en beweging leiden tot gewichtsreductie, is bekend dat minder dan 15% van de patiënten het gewichtsverlies kan vasthouden. Daarnaast leidt een gewichtsverlies van 3-5% tot afname van steatose, maar is gewichtsverlies van minstens 7-10% nodig om een afname in inflammatie en fibrose te realiseren. Daarom is leefstijlinterventie alleen waarschijnlijk onvoldoende om patiënten met progressieve MASLD/MASH met fibrose te behandelen. In aanvulling op leefstijlinterventies zijn er momenteel geen bewezen farmacotherapeutische behandelingsopties beschikbaar. Vanuit observationele studies is bekend dat bariatrische chirurgie aanhoudend klinisch effect heeft op het gewicht en het histologische spectrum van MASLD (steatose, inflammatie, levercelverval en fibrose). Daarom zou bariatrische chirurgie overwogen kunnen worden voor patiënten met obesitas en MASLD/MASH met gevorderde fibrose die at risk zijn voor het ontwikkelen van cirrose.

Er dient rekening gehouden te worden met eventuele complicaties van bariatrische chirurgie: directe complicaties zoals naadlekkage en wondinfectie, maar ook complicaties op de lange termijn, zoals malabsorptie, dumping en nesidioblastose. De risico’s op beide vormen complicaties zijn laag (Gilmore, 1995; Seef, 2010). Er bestaat ook een MASLD-gerelateerde lange termijn complicatie, namelijk paradoxale progressie van MASLD/MASH na bariatrische chirurgie. In de meta-analyse van Lee (2019) werd dit tot in 12% van de patiënten beschreven. In de controleconditie, namelijk geen bariatrische chirurgie ondanks progressieve MASLD-stadia met fibrose, kan levercirrose, hepatocellulair carcinoom en lever-gerelateerde mortaliteit optreden. Dit zijn relatief zeldzame eindstadia maar ernstig en toenemend in incidentie door de toename van MASLD en progressieve/ernstige stadia van dit ziektebeeld.

Een gevorderde leverziekte met portale hypertensie wordt gezien als een relatieve contra-indicatie voor bariatrische chirurgie. Recente studies laten zien dat in een geselecteerde populatie patiënten met obesitas en gecompenseerde cirrose bariatrische chirurgie haalbaar lijkt (Ahmed, 2021). Een gedecompenseerde cirrose is een absolute contra-indicatie voor bariatrische chirurgie vanwege het verhoogd aantal postoperatieve complicaties, die gepaard gaan met een toegenomen mortaliteit. Patiënten met obesitas, cirrose en portale hypertensie bij wie bariatrische chirurgie wordt overwogen, dienen bij voorkeur verwezen te worden naar een bariatrisch centrum die een samenwerkingsverband heeft met een levertransplantatiecentrum.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De belangrijkste doelen van bariatrische chirurgie voor de patiënt zijn genezing dan wel reductie van MASLD/MASH en het voorkomen van aan MASLD/MASH gerelateerde complicaties op de langere termijn: levercirrose, hepatocellulair carcinoom en lever-gerelateerde mortaliteit. Dit zijn voordelen die de patiënt ziet, en hiernaast zijn gewichtsreductie en zich gezonder en energieker voelen belangrijke voordelen. Nadelen die patiënten zien, kunnen ook zwaar wegen: een ingrijpende en invasieve procedure aan intacte organen, met een kans op complicaties, een kans op geen effect en zelfs een kleine kans op progressie van de ziekte van de ingreep. De waarde die individuele patiënten hechten aan deze voor- en nadelen, is overigens niet systematisch onderzocht.

Patiënten met fibrotische MASH hebben naast obesitas vaak co-morbiditeiten zoals DM2, hypertensie en obstructief slaapapneu syndroom. Deze factoren zijn naast de BMI bestaande meewegende factoren voor de indicatiestelling bariatrische chirurgie. De aan- dan wel afwezigheid van een of meerdere van deze factoren kan de voorkeur van de patiënt met MASLD/MASH voor bariatrische chirurgie beïnvloeden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen publicaties waarbij specifiek voor patiënten met MASH leverfibrose (stadium F1 of hoger) met een BMI > 35 kg/m2 is gekeken naar kosteneffectiviteit (definitie: wanneer een interventie vergelijkbaar effectief is met lagere kosten in vergelijking met de controle interventie of hetzelfde kost maar effectiever is) of kostenbesparing (definitie: wanneer een interventie minder kost maar effectiever is dan de controle interventie). De studies die gedaan zijn naar kosteneffectiviteit van bariatrische chirurgie zijn heterogeen en hebben geen eenduidige uitkomst (o.a. Klebanoff, 2017 en Maciejewski, 2013).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Door de obesitas pandemie met de hierbij groeiende aantallen patiënten met MASLD is er in aanvulling op leefstijlinterventie een sterke behoefte aan alternatieve behandelingen om progressieve leverziekte en cardiometabole complicaties te voorkomen. In Nederland zijn er 18 bariatrische centra die zodanig zijn verdeeld over Nederland dat deze zorg voor iedere Nederlander in de eigen regio beschikbaar is. Er zijn daarnaast ook duidelijke richtlijnen beschikbaar over wanneer patiënten verwezen kunnen worden voor bariatrische chirurgie en er vergoeding mogelijk is. Argumenten waardoor men terughoudend zou kunnen zijn om bariatrische chirurgie te verrichten bij patiënten met MASLD is het ontbreken van grote vergelijkende studies met MASLD als eindpunt. Verder vraagt een patiënt met MASLD met gevorderde fibrose dan wel cirrose extra expertise die niet in elk centrum beschikbaar is. Om voor iedere patiënt met MASLD en een verhoogd risico op een eindstadium leverziekte gepaste zorg te bieden, is het noodzakelijk om te investeren in het besef bij zorgverleners en patiënten dat obesitas kan leiden tot een chronische leveraandoening. Daarnaast is er behoefte aan een duidelijk (diagnostisch) zorgpad gericht op diagnostiek van MASLD bij obesitas en een behandelingsalgoritme voor deze categorie patiënten.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

MASLD/MASH is een progressieve leverziekte met mogelijk ernstige lever-gerelateerde complicaties en mortaliteit tot gevolg. Leefstijlinterventies zijn waarschijnlijk niet krachtig genoeg om patiënten met progressieve en ernstige stadia te kunnen stabiliseren dan wel te genezen. Er is nog geen bewezen of effectieve farmacotherapie voor ernstige, progressieve MASLD/MASH. Relatief kleine observationele studies met bariatrische chirurgie voor patiënten met MASLD/MASH tonen positieve behandeleffecten effecten op histologisch niveau voor alle drie de ziektecomponent van MASLD/MASH: steatose, MASH-activiteit en fibrose. Deze laatste hangt sterk samen met levergerelateerde mortaliteit en all cause mortality. De complicatiesrisico’s van bariatrische ingrepen zijn laag. Ondanks de nog lage bewijskracht van de onderliggende evidence, geven wij daarom een aanbeveling om bij een patiënt met BMI > 35 kg/m2 met ≥F2 fibrose ten gevolge van MASLD/MASH bij wie progressieve leverschade optreedt ondanks goed uitgevoerde leefstijlinterventies en bij wie farmacotherapeutische behandeling in studieverband geen optie is, om bariatrische chirurgie te overwegen als behandeling van het ernstige stadium van MASLD/MASH.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Voor patiënten met MASH en ernstige leverfibrose die niet verbeterd op leefstijlinterventies is er momenteel nog geen bewezen effectieve of geregistreerde farmacotherapie beschikbaar. Bariatrische chirurgie kan bij patiënten die aan de selectiecriteria voldoen, wel regressie en zelfs resolutie van MASH en fibrose induceren. Dit potentieel gunstige effect is mechanistisch plausibel: bariatrische ingrepen leiden tot snellere verzadiging en vermindering van insulineresistentie door toegenomen secretie van GLP-1 en PYY vanuit de dunne darm, tot toegenomen galzout-activatie van FXR waardoor lipogenese in de lever afneemt en afname van de inflammatie van perifeer vetweefsel waarvoor de vetzuurflux naar de lever afneemt (Lefere, 2021).

Mogelijk wordt deze behandeloptie voor MASH met fibrose nog te weinig toegepast. Er zijn echter ook data over ‘paradoxale’ progressie van MASH na bariatrische chirurgie. Daarnaast lijken de verschillende bariatrische procedures onvoldoende met elkaar vergeleken te zijn met betrekking tot het effect op MASH en MASH-fibrose.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

Reduction of hepatic steatosis

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain on the effect of bariatric surgery on biopsy proven reduction of steatosis, in patients with MASH and liver fibrosis.

Agarwal, 2021; Cabré, 2019; Garg, 2018; Salman, 2020; Salman, 2021a and Lee, 2019 |

Resolution of MASH

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain on the effect of bariatric surgery on biopsy-proven complete resolution of MASH features including lobular inflammation and ballooning degeneration, in patients with MASH and liver fibrosis.

Agarwal, 2021; Esquivel, 2018; Cabré, 2019; Garg, 2018; Lassailly, 2020; Salman, 2020; Salman, 2021a; Salman, 2021b and Lee, 2019. |

Resolution of MASLD-related liver fibrosis

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain on the effect of bariatric surgery on biopsy-proven complete resolution of MASLD-related liver fibrosis, in patients with MASH and liver fibrosis.

Agarwal, 2021; Esquivel, 2018; Cabré, 2019; Garg, 2018; Lassailly, 2020; Salman, 2020; Salman, 2021a; Salman, 2021b and Lee, 2019. |

Liver-related (serious) adverse events

|

very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain on the effect of bariatric surgery on (serious) liver-related adverse events, in patients with MASH and liver fibrosis.

Agarwal, 2021; Salman, 2020; Salman, 2021a; Salman, 2021b and Lee, 2019. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Lee (2019) conducted a systemic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effects of bariatric surgery on MASLD in obese patients. Lee (2019) covers the literature until May 2018 and literature searches were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Lee (2019) included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational studies examining the effect of bariatric surgery on MASLD. They included both single-arm studies (effect of bariatric surgery on MASLD status before and after surgery) or double-arm studies (bariatric surgery vs placebo or medical therapy) However, there were no double-arm studies identified. In total, 32 studies were included: 15 retrospective and 17 prospective cohort studies. In total, there is information on 3093 liver biopsies (the total number of included patients was not specified). There were no RCTs identified. All studies were single-arm studies examining the effect of bariatric surgery on MASLD before and after surgery with no comparators. Article quality of individual studies was assessed using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) tool. Quality of evidence for estimates derived from meta-analyses were assessed by Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). Outcomes were liver biopsy proven complete resolution of MASLD features (defined as the absence of histologic (biopsy) features of MASLD such as steatosis, inflammation, ballooning degeneration, and

fibrosis after bariatric surgery) and NAFLD activity score (NAS), which is a sum of the degree of steatosis (0-3), lobular inflammation (0-3) and hepatocyte ballooning (0-2). If a histopathologic grading system had a scale of 0 to 4, then 0 was considered to be complete resolution and 1 to 4 were categorized as disease.

Agarwal (2021) conducted a prospective cohort study assessing the impact of bariatric surgery on the course of MASLD. MASLD was assessed using paired liver biopsy (intra-operative and post-bariatric surgery at 1-year follow-up). Included were all consecutive patients undergoing bariatric surgery, as per the standard National Institute of Health (NIH) criteria. In total, 58 patients (70.7% females, mean age 39.9 ± 11.2 years, mean BMI …) underwent paired liver biopsy. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), and laparoscopic one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) were the bariatric procedures performed. During bariatric surgery, a liver biopsy was taken from the left lobe of the liver under laparoscopic vision. A follow-up liver biopsy was taken 1 year post bariatric surgery. Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) measurements were performed with FibroScanÒ both pre- and post-bariatric surgery. Fibrosis was graded based on the absence of fibrosis (F0); mild fibrosis (F1); moderate fibrosis (F2); bridging fibrosis (F3); and cirrhosis (F4). Steatosis was graded based on the percentage of hepatocytes containing lipid droplets as S0: <5%; S1: 5%–33%; S2: 34%–66%; and S3 >66%. Lobular inflammation was graded as L0: none; L1: <2 foci/200 fields; L2: 2–4 foci/200 fields; and L3: >4 foci/ 200 fields. Hepatocyte ballooning was graded as B0: none; B1: few; and B2: prominent ballooning. The outcome was the assessment of change in grade of steatosis and stage of fibrosis 1-year post-bariatric surgery using both liver biopsy and FibroScanÒ elastography.

Cabré (2019) conducted a prospective cohort study assessing the modulation of hepatic indices of oxidative stress and inflammation in obese patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). Included were 436 patients who attended an obesity clinic and underwent LSG for weight loss. A diagnostic intraoperative liver biopsy was obtained in a subcohort of 120 patients who agreed to a 1-year follow-up that included donation of blood samples and additional liver biopsies. Biopsies were performed by ultrasound-guided, percutaneous needle puncture. Patients were classified according to the NAS system. Values assigned were ≤2 for non-MASH, >2 and ≤4 for probable MASH, and ≥5 for definite MASH. Fibrosis was staged as the absence of fibrosis (F0), mild to moderate fibrosis (F1 and F2), bridging fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis (F4). Outcomes were change in steatosis grade, lobular inflammation, hepatocellular ballooning, fibrosis and cirrhosis pre- and post-bariatric surgery.

Esquivel (2018) conducted a prospective cohort study evaluating the evolution of MASLD in patients with obesity after 1 year of sleeve gastrectomy (SG). Included were patients between 18 and 70 years old with a BMI >40 kg/m2 or a BMI >35 kg/m2 with comorbidities. In total, 63 patients were included (mean age was 40 ± 10 years; 65% of the patients were female; mean initial weight was 129 ± 23 kg). Intraoperative liver biopsy was performed in 63 obese patients who underwent SG. Forty-three patients were again biopsied 1 year after surgery. The first hepatic biopsy was carried out during the SG, and the second one after 1 year by using percutaneous CT scan technique. Demographics, body mass index, percentage of excess weight loss, liver function tests, lipid panel, glucose panel, and histological changes of liver were prospectively analysed. Histological grades and stages of liver fibrosis were categorized by using the Brunt classification. Outcomes were changes in grade of steatosis, grade of steatohepatitis and grade of fibrosis. Patients were classified according to classified

according to Brunt classification.

Garg (2018) conducted a prospective cohort study assessing the utility of CAP for assessment of hepatic steatosis in morbidly obese individuals and evaluated the effect of bariatric surgery on hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. Included were consecutive patients with body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2 or patients with BMI >35 kg/m2 and associated co-morbidities undergoing bariatric surgery between October 2014 and June 2016. Baseline details of anthropometric data, laboratory parameters, FibroScanÒ (XL probe), and liver biopsy were collected. Follow-up liver biopsy was done at 1 year. MASLD was graded using the NAFLD activity score (NAS). NAS ≥5 with or without fibrosis was considered as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Fibrosis was staged from 0 to 4: F0—the absence of fibrosis; F1— perisinusoidal or portal; F2—perisinusoidal and portal/ periportal; F3—septal or bridging fibrosis; and F4—cirrhosis. Fibrosis with stage 2 or above was considered as significant fibrosis and fibrosis with stage 3 or above was considered advanced fibrosis. Outcomes were change in liver histology pre- and post-bariatric surgery.

Lassailly (2020) conducted a prospective study evaluating sequential liver samples, collected the time of bariatric surgery and 1 and 5 years later, to assess the long-term effects of bariatric surgery in patients with MASH. Included were patients >18 years of age with body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2 or patients with BMI >35 kg/m2 and associated co-morbidities undergoing bariatric surgery with biopsy-proven MASH, defined by the MASH clinical research network histologic scores. In total, 180 patients were included (mean age 46.7 ± 10.6 years; 66% female). The patients underwent bariatric surgery at a single centre in France and were followed for 5 years. Liver biopsies were systematically planned during the surgical procedure and approximately 1 and 5 years after surgery. The pathologists first diagnosed MASH, then determined the NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) and graded the severity of necroinflammatory activity using the Brunt’s score. Liver fibrosis was assessed using Kleiner’s fibrosis score, defined as follows: F0, normal; F1 stage is divided into 3 subclasses: 1a, mild pericellular fibrosis in zone 3, 1b, moderate pericellular fibrosis in zone 3, and 1c, portal fibrosis; F2, perivenular and pericellular fibrosis confined to zones 2 and 3, with or without portal or periportal fibrosis; F3, bridging or extensive fibrosis with architectural distortion and no clear-cut cirrhosis; and F4, cirrhosis The primary endpoint was the resolution of MASH without worsening of fibrosis at 5 years. Secondary end points were improvement in fibrosis (reduction of >1 stage) at 5 years and regression of fibrosis and MASH at 1 and 5 years.

Salman (2020) conducted a prospective cohort study investigating the histological changes in MASLD that occur in obese patients 1-year post-laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) based on standardized NAS. Included were patients >18 years of age with body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2 or patients with BMI >35 kg/m2 and associated co-morbidities undergoing LSG. In total, 94 patients underwent a second liver biopsy (mean age 41.39 + 7.64 years; 60% male). Intraoperative wedge liver biopsy was taken from all patients, with a follow-up liver biopsy at 12 months after the operation. NAS is a validated score that is used to grade disease activity in patients with MASLD. The NAS is the sum of the biopsy’s individual scores for steatosis (0 to 3), lobular inflammation (0 to 3), and hepatocellular ballooning (0 to 2). Fibrosis is not included in the NAS. For statistical analyses, patients were grouped into the three different NAS groups (group 1 = NAS 0–2: probable no MASH; group 2 = NAS 3–4: borderline MASH; group 3 = NAS 5–8: probable MASH). Outcome was histological change (steatosis grade, hepatocyte ballooning, lobular inflammation, fibrosis stage) pre- and post-LSG.

Salman (2021a) conducted a prospective study evaluating the safety of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in cases that have compensated metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)-related cirrhosis and its impact on fibrosis stage. Included were Child-A cirrhotic patients between 18 and 60 years of age with body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2 or patients with BMI >35 kg/m2 and associated co-morbidities undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). In total, 70 patients completed follow-up (mean age 44.4 ± 5.6 years; 54% male). Patients underwent intraoperative wedge liver biopsy with F4 stage, and had a follow-up after 30 months with ultrasound-guided true-cut liver biopsy. NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) was determined using these biopsies. For statistical purposes, subjects were divided according to NAS into three subgroups (1: NAS 0–2, probable no MASH; 2: NAS 3–4, borderline MASH; 3: NAS 5–8, probable MASH). Importantly, fibrosis stage after 30 months was also staged (F0 = absent fibrosis; F1 = perisinusoidal or portal fibrosis; F2 = perisinusoidal and portal/ periportal fibrosis; F3 = septal or bridging fibrosis; and F4 = cirrhosis). The needle biopsies were taken at the same time point for each patient participating in the study. The primary outcome measure was the impact of LSG on fibrosis stage. Secondary outcome measures were the improvement of other features of steatohepatitis in addition to operation-related morbidity.

Salman (2021b) conducted a prospective study evaluating the effect of one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) on pathological liver changes in severely obese cases with MASLD. Included were patients between 18 and 60 years of age with body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2 or patients with BMI >35 kg/m2 and associated co-morbidities scheduled for OAGB. In total, 67 patients were included (mean age 44.4 ± 5.7; 52% male). Intraoperative liver biopsy was performed and follow-up biopsy was performed at 15 months. A single expert physician examined the liver biopsies (at first and 15 months postoperatively) using a light microscope or histological assessment guided by the NAS scoring system, which is a well-established method employed to describe the severity in MASLD cases. Cases were divided into the three NAS categories (Category 1: NAS = 0–2: probable no MASH; Category 2: NAS = 3–4: borderline MASH; and Category 3: NAS = 5–8: probable MASH). Outcomes were the effect of OAGB on MASH status and fibrosis severity.

Results

Reduction of hepatic steatosis

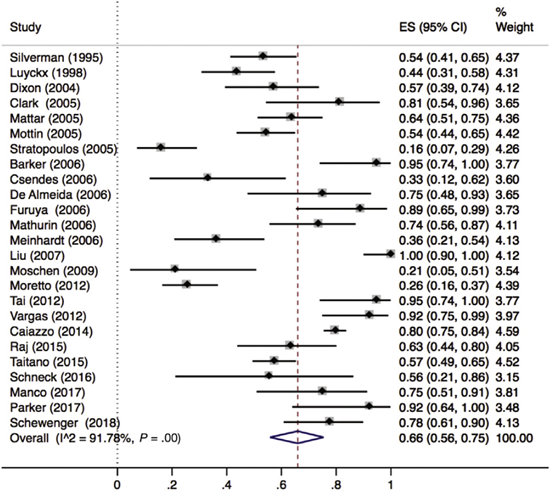

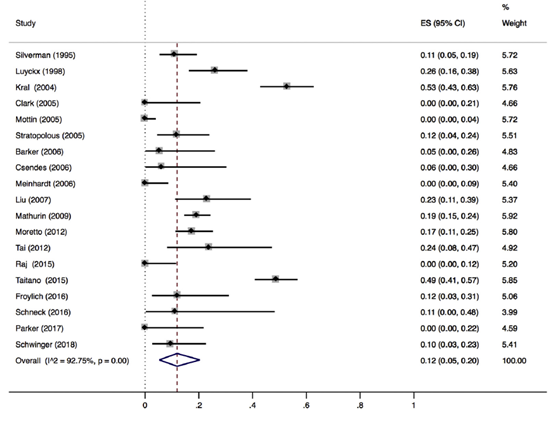

Lee (2019) included 32 observational studies with histologically characterized MASLD in patients undergoing bariatric surgery for obesity, of which, 25 reported hepatic steatosis (n=1329 patients). Lee 2019 found that 66% (95% CI 56% to 75%) of the patients had complete resolution of hepatic steatosis after bariatric surgery (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportion meta-analysis forest plot of biopsy-proven complete resolution of steatosis (adapted from Lee, 2019). ES, effect size.

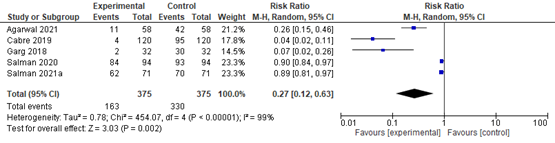

Agarwal (2021) compared the proportion of steatosis pre- and post-bariatric surgery found that 42/58 (72.4%) patients had steatosis >1 pre-bariatric surgery compared to 11/58 (19.0%) patients at 12 months post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.26 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.46) in favor of bariatric surgery. Overall, 36/58 (60.2%) patients showed improvement in hepatic steatosis at 12 months post-bariatric surgery.

Cabré (2019) compared the proportion of steatosis pre- and post-LSG found that 95/12 (79.2%) patients had steatosis >1 pre-LSG compared to 4/120 (3.3%) patients at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.04 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.11) in favor of LSG.

Garg (2018) compared steatosis pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 2/32 (6.2%) patients showed worsening steatosis while 30/32 (93.8%) patients showed improvement or no change in steatosis. The RR was 0.07 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.26) in favor of bariatric surgery.

Salman (2020) compared the proportion of steatosis pre- and post-LSG found that 93/94 (98.9%) patients had steatosis >1 pre-LSG compared to 84/94 (89.4%) patients at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.90 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.97) in favor of LSG.

Salman (2021a) compared the proportion of steatosis pre- and post-LSG found that 70/71 (98.6%) patients had steatosis >1 pre-LSG compared to 62/71 (87.3%) patients at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.89 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.97) in favor of LSG.

In summary, there were 5 additional observational studies that reported on steatosis before and after bariatric surgery. The pooled RR was 0.27 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.63; Figure 2) in favor of bariatric surgery. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the proportion of patients experiencing steatosis pre-bariatric surgery compared to post-bariatric surgery. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model.

Reduction of MASH

Lobular inflammation

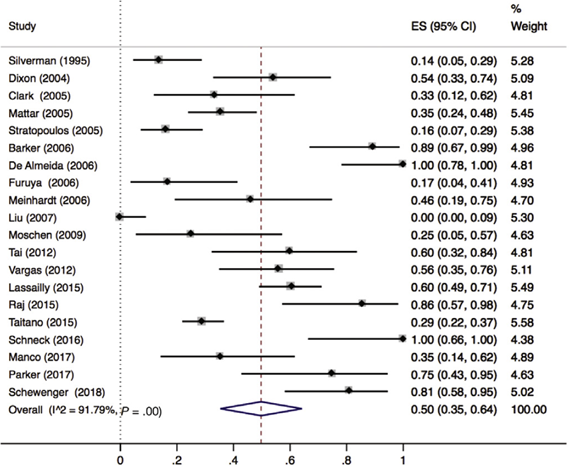

Lee (2019) included 32 observational cohort studies (n=2925 patients) that reported on resolution of MASH. Of these 32 studies, 21 reported lobular inflammation (n=657 patients). Lee 2019 found that 50% (95% CI 35% to 64%) of the patients had complete resolution of lobular inflammation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Proportion meta-analysis forest plot of biopsy-proven complete resolution of lobular inflammation (adapted from Lee, 2019). ES, effect size.

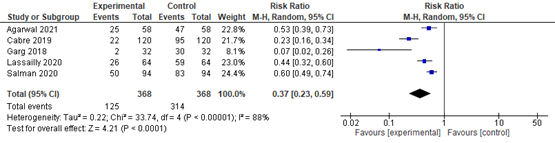

Agarwal (2021) compared the proportion of lobular inflammation pre- and post-bariatric surgery found that 47/58 (81.0%) patients had lobular inflammation >1 pre-bariatric surgery compared to 25/58 (43.1%) patients at 12 months post-bariatric surgery. The RR 0.53 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.73) in favour of bariatric surgery. Overall, 24/58 (41.4%) patients showed improvement in lobular inflammation at 12 months post-bariatric surgery.

Cabré (2019) compared the proportion of lobular inflammation pre- and post-LSG found that 95/120 (79.2%) patients had lobular inflammation >1 pre-LSG surgery compared to 22/120 (18.3%) patients at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.23 (95% CI 0.16 to 0.34) in favour of LSG.

Garg (2018) compared lobular inflammation pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 2/32 (6.2%) patients showed worsening lobular inflammation while 30/32 (93.8%) patients showed improvement or no change in lobular inflammation. The RR was 0.07 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.26) in favour of bariatric surgery.

Lassailly (2020) compared the proportion of lobular inflammation pre- and post-bariatric surgery found that 59/64 (92.2%) patients had lobular inflammation >1 pre-bariatric surgery compared to 26/64 (40.6%) patients at 5 years post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.44 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.60) in favour of bariatric surgery.

Salman (2020) compared the proportion of lobular inflammation pre- and post-LSG found that 83/94 (88.3%) patients had lobular inflammation >1 pre-LSG surgery compared to 50/94 (53.2%) patients at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.60 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.74) in favour of LSG.

In summary, there were 5 additional observational studies that reported on lobular inflammation before and after bariatric surgery. The pooled RR was 0.37 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.59; Figure 4) in favour of bariatric surgery. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the proportion of patients experiencing lobular inflammation pre-bariatric surgery compared to post-bariatric surgery. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model.

Ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes

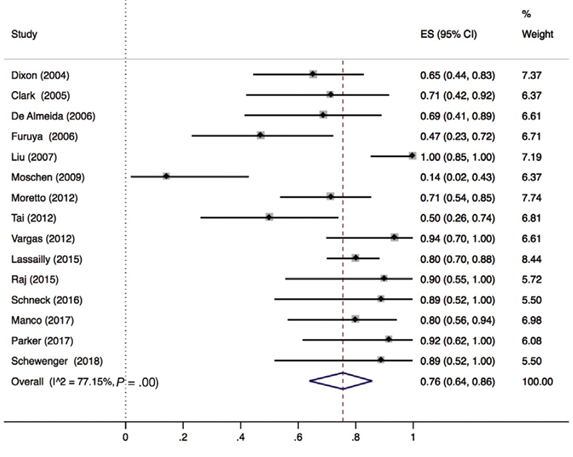

Lee (2019) included 32 observational studies of which 15 studies reported ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes (n=320 patients). Lee 2019 found that 76% (95% CI 64% to 86%) of the patients had complete resolution of ballooning degeneration after bariatric surgery (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proportion meta-analysis forest plot of biopsy-proven complete resolution of ballooning degeneration (adapted from Lee, 2019). ES, effect size.

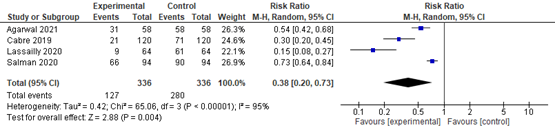

Agarwal (2021) compared the proportion of ballooning pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 58/58 (100%) patients had ballooning >1 pre-bariatric surgery compared to 31/58 (53.4%) patients at 12 months post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.54 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.68) in favour of bariatric surgery. Overall, 30/58 (51.7%) patients showed improvement in ballooning at 12 months post-bariatric surgery.

Cabré (2019) compared the proportion of ballooning pre- and post-LSG found that 71/120 (59.2%) patients had ballooning >1 pre-LSG compared to 21/120 (17.5%) patients at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.30 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.45) in favour of LSG.

Garg (2018) compared ballooning pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 0/32 (0%) patients showed worsening ballooning while 32/32 (100%) patients showed improvement or no change in ballooning.

Lassailly (2021) compared the proportion of ballooning pre- and post-bariatric surgery found that 61/64 (95.3%) patients had ballooning >1 pre-bariatric surgery compared to 9/64 (14.1%) patients at 12 months post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.15 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.27) in favour of bariatric surgery.

Salman (2020) compared the proportion of ballooning pre- and post-LSG found that 90/94 (95.7%) patients had ballooning >1 pre-LSG compared to 66/94 (70.2%) patients at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.73 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.84) in favour of LSG.

In summary, there were 5 additional observational studies that reported on ballooning degeneration before and after bariatric surgery. One study was excluded from pooled analyses because no RR could be calculated. The pooled RR of the remaining 4 observational studies was 0.38 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.72; Figure 6) in favour of bariatric surgery. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 6. Forest plot showing the proportion of patients experiencing ballooning degeneration pre-bariatric surgery compared to post-bariatric surgery. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model.

MASH

Agarwal (2021) compared the proportion of MASH pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 3/58 (5.2%) patients showed MASH pre-bariatric surgery while 2/58 (3.4%) patients showed MASH post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.67 (95%CI 0.12 to 3.84) in favour of bariatric surgery.

Esquivel (2018) compared the proportion of MASH pre- and 12 months post-LSG and found that 3/ 43 (48.8%) patients showed MASH pre-LSG surgery while 0/43 (0%) patients showed MASH at 12 months post-LSG surgery meaning that in all patients, MASH resolved completely.

Garg (2018) compared the proportion of MASH pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 4/32 (1.25%) patients showed MASH pre-bariatric surgery while 1/32 (0.03%) patients showed MASH post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.25 (0.03 to 2.12) in favour of bariatric surgery.

Lassailly (2020) found that resolution of MASH with no worsening of fibrosis

occurred in 54/64 patients with MASH (84.4%; 95% CI, 73.1%–92.2%) 5 years after bariatric surgery.

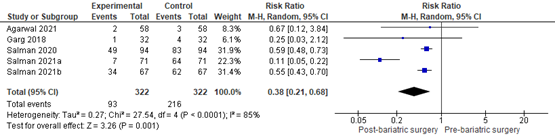

Salman (2020) compared the proportion of MASH pre- and post-LSG and found that 83/94 (88.3%) patients showed borderline or definite MASH pre-LSG while 49/94 (52.1%) patients showed borderline or definite MASH at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.59 (95% CI 0.48 to 0.73) in favour of LSG.

Salman (2021a) compared the proportion of MASH pre- and post-LSG and found that 64/71 (90.1%) patients showed borderline or definite MASH pre-LSG while 7/71 (9.8%) patients showed borderline or definite MASH at 30 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.11 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.22) in favour of LSG.

Salman (2021b) compared the proportion of MASH pre- and at 15 months post-LSG and found that 62/71 (92.5%) patients showed borderline or definite MASH pre-LSG surgery while 34/67 (50.8%) patients showed borderline or definite MASH post-LSG surgery. The RR was 0.55 (0.43 to 0.70) in favour of LSG.

In summary, there were 6 observational studies that reported on MASH before and after bariatric surgery. One study was excluded from pooled analyses because no RR could be calculated. The pooled RR of the remaining 5 observational studies was 0.43 (95% CI 0.36 to 0.51; Figure 7) in favour of bariatric surgery. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 7. Forest plot showing the proportion of MASH pre-bariatric surgery compared to post-bariatric surgery. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model.

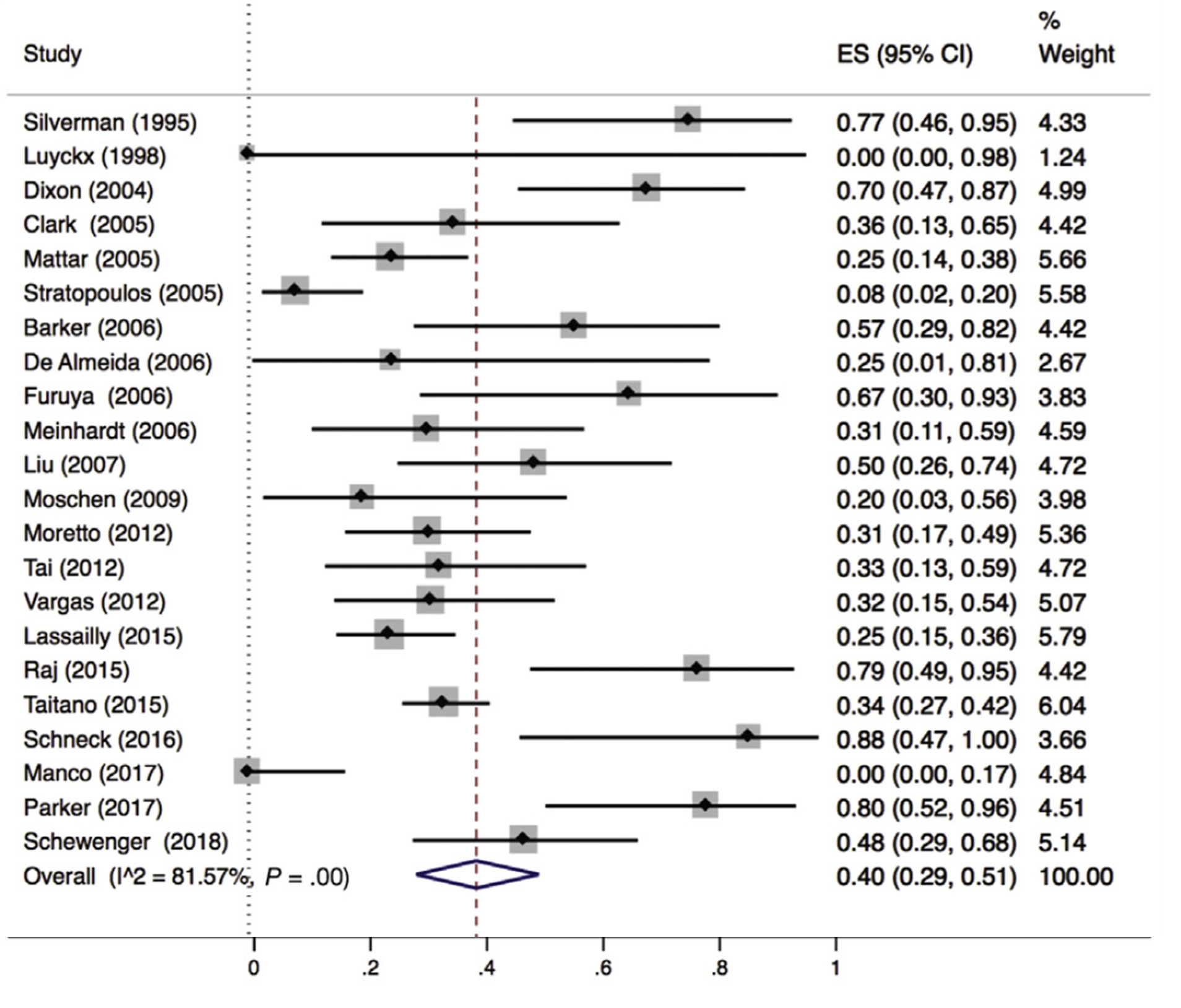

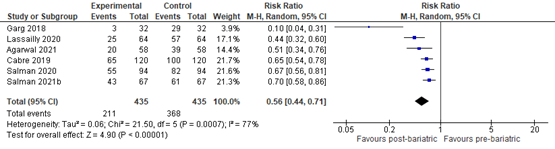

Reduction of liver fibrosis

Lee (2019) included 32 observational studies of which 22 studies reported liver fibrosis (n=619 patients). Lee 2019 found that 40% of patients (95% CI 29% to 51%) of the patients had complete resolution of fibrosis upon bariatric surgery (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Proportion meta-analysis forest plot of biopsy-proven complete resolution of fibrosis (adapted from Lee, 2019). ES, effect size.

Agarwal (2021) compared the proportion of MASLD-related liver fibrosis pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 39/58 (67.2%) patients had fibrosis stage >1 pre-bariatric surgery compared to 20/58 (34.5%) patients at 12 months post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.51 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.76) in favour of bariatric surgery. Overall, 10/58 (17.2%) patients showed worsening fibrosis while 48/58 patients showed improvement or no change in fibrosis at 12 months post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.21 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.37) in favour of bariatric surgery.

Cabré (2019) compared the proportion of MASLD-related liver fibrosis pre- and post-LSG found that 100/120 (80.0%) patients had fibrosis >1 pre-LSG compared to 65/120 (54.2%) patients at 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.65 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.78) in favour of LSG.

Esquivel (2018) compared MASLD-related liver fibrosis stages pre- and 12 months post-LSG. A second liver biopsy at 12 months was performed in only one of the patients with previous diagnosis of liver fibrosis, and showed fibrosis was resolved at 12 months after LSG.

Garg (2018) compared MASLD-related liver fibrosis stages pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 3/32 (10%) patients showed worsening fibrosis while 29/32 (90%) patients showed improvement or no change in fibrosis. The RR was 0.10 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.31) in favour of bariatric surgery.

Lassailly (2020) compared MASLD-related liver fibrosis stages pre- and post-bariatric surgery and found that 57/64 (89.1%) patients had fibrosis at baseline compared to 25/64 (39.1%) patients 5-years post-bariatric surgery. The RR was 0.44 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.60) in favour of bariatric surgery. Overall, 62.9% of patients with F1-F2 fibrosis showed resolution at 5 years post bariatric surgery compared to 45.5% with F3-F4 fibrosis at baseline.

Salman (2020) compared MASLD-related liver fibrosis stages pre- and post-LSG and found that 82/94 (89.1%) patients had fibrosis > 1 at baseline compared to 55/94 (58.5%) patients 12 months post-LSG. The RR was 0.67 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.81) in favour of LSG.

Salman (2021b) compared MASLD-related liver fibrosis stages pre- and post-OAGB and found that 61/67 (91%) patients showed worsening fibrosis while 43/67 (64.2%) patients showed improvement in fibrosis at 15 months post-OAGB. The RR was 0.70 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.86) in favour of OAGB.

In summary, there were 7 additional observational studies that reported on MASLD-related liver fibrosis before and after bariatric surgery. One study was excluded from pooled analyses because no RR could be calculated. The pooled RR of the remaining 6 observational studies was 0.56 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.71; Figure 9) in favour of bariatric surgery. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 9. Forest plot showing the proportion of patients experiencing fibrosis pre-bariatric surgery compared to post-bariatric surgery. Pooled risk ratio, random effects model.

Liver-related (serious) adverse events

Lee (2019) included 32 observational studies of which 19 studies reported on postoperative worsening of MASLD (n=1231 biopsies). Lee (2019) concluded that development or worsening of MASLD-characteristics occurred in 12% (95CI: 5% to 20%) of the patients (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Proportion meta-analysis forest plot of postoperative histologic worsening of MASLD (adapted from Lee, 2019). ES, effect size.

Agarwal (2021) reported on postoperative worsening of MASLD-characteristics, including steatosis, lobular inflammation, ballooning and MASH. In total, 10/58 (17.2%) patients had worsening of MASLD-characteristics. Four (7%) patients had worsening of steatosis, five (8.6%) patients had worsening of lobular inflammation, one (1.7%) patient had worsening of ballooning, five (8.6%) patients had worsening of MASH and ten (17.2%) patients had worsening of fibrosis.

Salman (2020) reported on postoperative worsening of MASLD-characteristics. One patient of the 94 patients had worsening of steatohepatitis. At first, this patient had non-MASH and turned into borderline MASH at 1-year follow-up. None of the patients showed worsening of fibrosis stage.

Salman (2021a) reported on (serious) adverse events, including postoperative worsening of MASLD-characteristics. In total 3/71 (4.2%) patients had postoperative worsening of steatosis.

Salman (2021b) reported on postoperative worsening of MASLD-characteristics. None of the 67 patients had worsening of MASH grade.

Level of evidence of the literature

Reduction of hepatic steatosis, resolution of MASH features, resolution of MASLD-related fibrosis and (serious) adverse events

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures reduction of hepatic steatosis, resolution of MASH features, resolution of MASLD-related fibrosis and liver-related (serious) adverse events came from observational studies and started as low. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of inconsistency (heterogeneity; downgraded one level) resulting in a very low level of evidence.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of bariatric surgery on MASLD in obese patients, particularly on MASH with advanced fibrosis?

P (population): Patients with MASH and liver fibrosis (stage F1 or higher) and a BMI > 35 kg/m2

I (intervention): Bariatric surgery

C (control): (combined) lifestyle intervention, placebo or no treatment.

O (outcomes): Reduction of steatosis on follow-up liver biopsy, resolution of MASH on follow-up liver biopsy, or reduction of ≥1 stage liver fibrosis on follow-up liver biopsy, liver-related (serious) adverse events

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered resolution of MASH on follow-up liver biopsy, reduction of ≥1 stage liver fibrosis on follow-up liver biopsy and liver-related (serious) adverse events as critical outcome measure for decision making. Reduction of steatosis was considered as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group defined the outcome measures as listed above but in the literature analysis they used the definitions of the outcome defined in the included studies.

The working group defined the GRADE standard limit of 25% difference for dichotomous outcomes (RR <0.8 or >1.25) and 0.5 SD for continuous outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

Two different literature searches were performed. At first we searched for systematic reviews and after this we performed an additional search to supplement the selected review(s) with observational studies that were published after the search date of the selected review(s).

Search 1: Systematic reviews (SR)

- The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 25 Augustus 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 121 hits. First, systematic reviews (SR) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were selected evaluating the effects of bariatric surgery on MASLD in obese patients compared to a lifestyle intervention, placebo, or no treatment. Studies measuring outcomes ≥ 3 months follow-up were included. 22 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 21 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one SR study (Lee, 2019) was included.

Search 2: Observational studies

- The search strategy of the systematic review (Lee, 2019) was completed on May 2019. Therefore, we performed an additional search on observational studies in the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) with relevant search terms between 1st of January 2019 until the 1st of November 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 265 hits. Studies measuring outcomes for periods of ≥ 3 months post bariatric surgery were included. 45 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 37 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 8 studies were included.

In total, 1 SR (search 1) and 8 observational studies (search 2) were included.

Results

Nine studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Agarwal, L., Aggarwal, S., Yadav, R. et al (2021). Bariatric surgery in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): impact assessment using paired liver biopsy and fibroscan. Obesity surgery, 31(2), 617-626.

- Ahmed, S., Pouwels, S., Parmar, C. et al (2021). Outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with liver cirrhosis: a systematic review. Obesity Surgery, 31(5), 2255-2267.

- Cabré, N., Luciano-Mateo, F., Fernández-Arroyo, S. et al (2019). Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy reverses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease modulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Metabolism, 99, 81-89.

- Esquivel, C. M., Garcia, M., Armando, L. et al (2018). Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy resolves NAFLD: another formal indication for bariatric surgery?. Obesity surgery, 28(12), 4022-4033.

- Garg, H., Aggarwal, S., Yadav, R. et al (2018). Utility of transient elastography (fibroscan) and impact of bariatric surgery on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in morbidly obese patients. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 14(1), 81-91.

- Gilmore, I. T., Burroughs, A., Murray-Lyon, I. M. et al (1995). Indications, methods, and outcomes of percutaneous liver biopsy in England and Wales: an audit by the British Society of Gastroenterology and the Royal College of Physicians of London. Gut, 36(3), 437-441.

- Klebanoff, M. J., Corey, K. E., Samur, S. et al (2019). Cost-effectiveness analysis of bariatric surgery for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis. JAMA network open, 2(2), e190047-e190047.

- Lassailly, G., Caiazzo, R., Ntandja-Wandji, L. C. et al (2020). Bariatric surgery provides long-term resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and regression of fibrosis. Gastroenterology, 159(4), 1290-1301.

- Lee, Y., Doumouras, A. G., Yu, J. et al (2019). Complete resolution of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical gastroenterology and Hepatology, 17(6), 1040-1060.

- Maciejewski, M. L., & Arterburn, D. E. (2013). Cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery. JAMA, 310(7), 742-743.

- Salman, M. A., Salman, A. A., Abdelsalam, A. et al (2020). Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on the horizon as a promising treatment modality for NAFLD. Obesity Surgery, 30(1), 87-95.

- Salman, M. A., Mikhail, H. M. S., Nafea, M. A. et al (2021). Impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on fibrosis stage in patients with child-A NASH-related cirrhosis. Surgical Endoscopy, 35(3), 1269-1277.

- Salman, M. A., Salman, A. A., Omar, H. S. et al (2021). Long-term effects of one-anastomosis gastric bypass on liver histopathology in NAFLD cases: A prospective study. Surgical endoscopy, 35(4), 1889-1894.

- Seeff, L. B., Everson, G. T., Morgan, T. R. et al & HALTC Trial Group. (2010). Complication rate of percutaneous liver biopsies among persons with advanced chronic liver disease in the HALT-C trial. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology, 8(10), 877-883.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: What is the effect of bariatric surgery on MASLD in obese patients, particularly on MASH with advanced fibrosis?

Evidence table for systematic reviews

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control I

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Lee, 2019

|

SR and met cohort studies

Literature search up to may, 2018

See table 1 (Lee, 2019) for study characteristics of the included studies.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: The authors of report no conflict of interest but conflict of interests for the included studies were not reported.

No funding was reported but included studies were funded private or by public funds. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Articles were eligible for inclusion if the studies examined the effect of bariatric surgery on MASLD. We included both single-arm studies (effect of bariatric surgery on MASLD status before and after surgery) or double-arm studies (bariatric surgery vs placebo or medical therapy).

Exclusion criteria SR:

32 studies included (1) case-series/reports, expert opinions, basic science, and review articles; (2) nonhuman studies; (3) studies with fewer than 10 eligible patients; and (4) patients with cirrhosis or a history of liver transplants.

Important patient characteristics at baseline: See table 1 (Lee, 2019) for study characteristics of the included studies.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

MASLD features pre-bariatric surgery

|

Describe control:

MASLD features post-bariatric surgery

|

End-point of follow-up:

1 month to 5 years. (See table 1, Lee, 2019 for study characteristics of the included studies.)

….

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) Not reported

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of inflammation; % (95% CI) 21 studies/657 patients

50% (95% CI 35% to 64%) of the patients had complete resolution of inflammation

Resolution of ballooning degeneration; % (95% CI) 15 studies /320 patients

76% (95% CI 64% to 86%) of the patients had complete resolution of ballooning degeneration after bariatric surgery

Resolution of steatosis; % (95% CI) 25 studies/1329 patients 66% (95% CI 56% to 75%) of the patients had complete resolution of steatosis after bariatric surgery

Resolution of fibrosis; % (95% CI) 22 studies/619 patients

40% of patients (95% CI 29% to 51%) of the patients had complete resolution of fibrosis after bariatric surgery |

Facultative:

The authors conclude that bariatric surgery leads to complete resolution in histologic features of MASLD as well as a significant reduction of NAS in a substantial proportion of patients. However, the certainty of evidence is very low, warrants further high-quality studies, preferably RCTs, to recommend bariatric surgery as a therapy for MASLD remission.

|

Evidence table for intervention studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control I

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Agarwal 2021 |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital India

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding source had been reported.

The authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Included were all consecutive patients undergoing bariatric surgery, as per the standard National Institute of Health (NIH) criteria

Exclusion criteria: Alcohol consumption > 21 drinks/week for men and > 14 drinks per week for women; Patients with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection; Associated other causes of liver diseases such as autoimmune disease or any other metabolic storage disorders; Consumption of medicines known to induce fatty liver or insulin sensitization such as estrogens, tamoxifen, methotrexate, and glitazones

N total at baseline: N=179

Important prognostic factors2: MASH: 78.2% (140/179) Any grade of fibrosis (≥ F1): 117 (65.4%) |

MASH features pre-bariatric surgery

|

MASH features post-bariatric surgery

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 12 patients did not have valid Transient Elastography(TE) 83 patients did not give consent for post bariatric 1-year follow-up biopsy

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of MASH; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 3/58 (5.2%) Post-bariatric surgery: 2/58 (3.4%) RR= 0.67 (95%CI 0.12 to 3.84)

Resolution of inflammation; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 47/58 (81.0%) Post-bariatric surgery: 25/58 (43.1%) RR= 0.53 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.73)

Resolution of ballooning degeneration; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 58/58 (100%) Post-bariatric surgery: 31/58 (53.4%) RR= 0.54 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.68)

Resolution of steatosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 42/58 (72.4%) Post-bariatric surgery: 11/58 (19.0%) RR= 0.26 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.46)

Resolution of fibrosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 39/58 (67.2%) Post-bariatric surgery: 20/58 (34.5%) RR= 0.51 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.76) |

The authors conclude that Bariatric surgery significantly improves MASLD histology, including steatosis, ballooning, inflammation, and fibrosis. |

|

Cabré, 2019 |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital spain

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study was funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), and by Fundació La Marató de TV3

The authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Included were all consecutive patients with severe obesity who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG)

Exclusion criteria: age <25 years, alcohol abuse, infectious diseases, primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune diseases, and cancer.

N total at baseline: N=436

Important prognostic factors2: Male: 24.5% (107/436)

MASH: 56.2% (245/436)

Any grade of fibrosis (≥ F1): 71.3% (311/436)

Any grade of steatosis: 63.6% (277/436)

Any grade of inflammation: 63.3% (363/436)

Any grade of Ballooning : 43.8% (191/436) |

MASH features pre-LSG

|

MASH features post-LSG

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 316 patients did not have a post bariatric 1-year follow-up biopsy

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of inflammation; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 95/120 (79.2%) Post-bariatric surgery: 22/120 (18.3%) RR= 0.23 (95% CI 0.16 to 0.34)

Resolution of ballooning degeneration; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 71/120 (59.2%) Post-bariatric surgery: 21/120 (17.5%) RR= 0.30 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.45)

Resolution of steatosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: that 95/12 (79.2%) Post-bariatric surgery: 4/120 (3.3%) RR= 0.07 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.26)

Resolution of fibrosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 100/120 (80.0%) Post-bariatric surgery: 65/120 (54.2%) RR= 0.65 (CI 0.54 to 0.78) |

The authors conclude that that LSG improves the histology and liver function of patients with morbid obesity. |

|

Esquivel, 2018 |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital Argentina

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding source had been reported.

The authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Included were all consecutive patients aged >18 and <70 years with a BMI >40 without comorbidities or a BMI >35 with comorbidities who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG)

Exclusion criteria: Patients with major psychiatric disorders or major depression. Patients with severe mental retardation. Patients who suffer from alcohol or drug abuse.

N total at baseline: N=63

Important prognostic factors2: mean age 40 ± 10 years;

female 65% (n = 41). Mean initial weight 129 ± 23 kg |

MASH features pre-LSG

|

MASH features post-LSG

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 20 patients did not have a post bariatric 1-year follow-up biopsy

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of MASH; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 3/ 43 (48.8%) Post-bariatric surgery: 0/43 (0%)

|

The authors conclude that LSG significantly improves MASLD after 12 months of follow-up, showing even a total regression in some of the patients. Neither of the patients presented worsening of the disease. |

|

Garg, 2018 |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital India

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding source had been reported.

The authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Included were all consecutive patients with a BMI >40 without comorbidities or a BMI >35 with comorbidities who underwent bariatric surgery.

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria were patients undergoing revision surgery; patients with alcohol consumption >21 drinks/week for men and >14 drinks per week for women; patients with hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection; patients with liver diseases due to other etiologies–autoimmune liver disease or metabolic storage disorders; patients on drugs known to induce fatty liver or insulin sensitization, such as estrogens, tamoxifen, amiodarone, methotrexate, and glitazones.

N total at baseline: N=124

Important prognostic factors2: mean age 39.3 ± 10.9 years

female 76.6% (n = 95)

mean initial weight 117.9 ± 20.2 kg |

MASH features pre-bariatric surgery

|

MASH features post-bariatric surgery

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 15 patients did not have valid TE measurements 33 patients did not undergo liver biopsy 1 patient died due to cellulitis of leg and septic shock 6 months a er surgery

7 patients lost to follow-up 10 patients did not give consent for follow-up liver Biopsy

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of MASH; RR (95% CI) Worsened: 4/32 (1.25%) Improved: 4/32 (1.25%) RR= 0.25 (0.03 to 2.12)

Resolution of inflammation; RR (95% CI) Worsened: 2/32 (6.2%) Improved: 30/32 (93.8%) RR= 0.07 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.26)

Resolution of ballooning degeneration; RR (95% CI) Worsened: 0/32 (0%) Improved: 32/32 (100%)

Resolution of steatosis; RR (95% CI) Worsened: 2/32 (6.2%) Improved: 30/32 (93.8%) RR= 0.90 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.97)

Resolution of fibrosis; RR (95% CI) Worsened: 3/32 (10%) Improved: 29/32 (90%) RR= 0.10 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.31)

|

The authors conclude that bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvement in metabolic parameters, LSM, CAP, steatohepatitis, and fibrosis on liver biopsy postsurgery |

|

Lassailly, 2020 |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital France

Funding and conflicts of interest: This study was funded the French Ministry of Health, the Conseil Régional Nord-Pas de Calais, Agence National de la Recherche and the European commission.

The authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Included were patients over 18 years, with a BMI >40 without comorbidities or a BMI >35 with comorbidities who underwent bariatric surgery.

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria: medical or psychologic contraindications to bariatric surgery; drink excessively, defined as an average daily consumption of alcohol of 20 g/d for women and 30 g/d for men, and had no history of excessive drinking for a period longer than 2 years at any time in the past 20 years; history of long-term consumption of hepatotoxic drugs; positive for chronic liver disease

N total at baseline: N=94

Important prognostic factors2: mean age 48.1 ± 7.9 years

female 66% (n = 116)

mean initial weight 117.9 ± 20.2 kg |

MASH features pre-bariatric surgery

|

MASH features post-bariatric surgery

|

Length of follow-up: 5 years

Loss-to-follow-up: 30 did not have a liver biopsy at 5 years follow-up

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of MASH; % (95% CI) resolution of MASH with no worsening of fibrosis occurred in 54/64 patients with MASH (84.4%; 95% CI, 73.1%–92.2%) 5 years after bariatric surgery

Resolution of inflammation; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 59/64 (92.2%) Post-bariatric surgery: 26/64 (40.6%) RR= 0.44 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.60)

Resolution of ballooning degeneration; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 61/64 (95.3%) Post-bariatric surgery: 9/64 (14.1%) RR= 0.30 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.45)

Resolution of fibrosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 57/64 (89.1%) Post-bariatric surgery: 25/64 (39.1%) RR= 0.44 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.60 |

The authors conclude that the 5-year follow-up of obese MASH patients showed that the beneficial effects of bariatric surgery on the resolution of MASH were durable and led to a sustained reduction in fibrosis over 5 years |

|

Salman, 2020 |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding was received.

The authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Included were all consecutive patients aged >18 and <60 years with a BMI >40 without comorbidities or a BMI >35 with comorbidities who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG)

Exclusion criteria: Severe medical diseases making anesthesia risky, unwilling to change lifestyle after surgery, psychologically unstable, those with unsupportive home environment, history of bariatric surgery, pregnancy, or lactation at screening or surgery

N total at baseline: N=94

Important prognostic factors2: mean age 41.39 + 7.64 years;

male 60.6% (n = 57).

Mean initial weight 123.56 ± 13.96 kg |

MASH features pre-LSG

|

MASH features post-LSG

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: none

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of MASH; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 83/94 (88.3%) Post-bariatric surgery: 49/94 (52.1%) RR= 0.59 (95% CI 0.48 to 0.73)

Resolution of inflammation; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 83/94 (88.3%) Post-bariatric surgery: 50/94 (53.2%) RR= 0.60 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.74)

Resolution of ballooning degeneration; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 90/94 (95.7%) Post-bariatric surgery: 66/94 (70.2%) RR= 0.73 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.84)

Resolution of steatosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 93/94 (98.9%) Post-bariatric surgery: 84/94 (89.4%) RR= was 0.90 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.97)

Resolution of fibrosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 82/94 (89.1%) Post-bariatric surgery: 55/94 (58.5%) RR= was 0.67 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.81) |

The authors conclude that LSG significantly improves steatosis, steatohepatitis, and fibrosis at a 1-year follow-up. LSG can lead to resolution of MASLD. |

|

Salman, 2021a |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding was received.

The authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Included were all consecutive patients aged >18 and <60 years with a BMI >40 without comorbidities or a BMI >35 with comorbidities who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG)

Exclusion criteria: dangerous medical conditions preventing anesthesia, not intending to modify their habits after the procedure; psychological issues; underwent previous metabolic surgery; gestation or lactation at initial nrolment or operation. Those who proved to have other etiologies of hepatic disorders, including viral, alcohol, immune-related, drug-elicited, cholestatic, genetical, or metabolic disorders

N total at baseline: N=71

Important prognostic factors2: mean age 44.4 ± 5.6 years;

male 53.5% (n = 38).

Mean initial weight 122.5 ± 14.5 kg |

MASH features pre-LSG

|

MASH features post-LSG

|

Length of follow-up: 30 months

Loss-to-follow-up: 61 patients did not undergo follow-up biopsy

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of MASH; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 64/71 (90.1%) Post-bariatric surgery: 7/71 (9.8%) RR= .11 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.22)

Resolution of steatosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 70/71 (98.6%) Post-bariatric surgery: 62/71 (87.3%) RR= 0.89 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.97)

|

The authors conclude that in patients with MASH-related liver cirrhosis of Child class A, LSG may be a secure approach for the management of morbid obesity. It has a long-term benefit for both obesity and liver condition. It assured a considerable weight reduction and resolution of comorbidities. Steatosis, steatohepatitis, and degree of liver fibrosis showed a significant resolution in more than two-thirds of patients. |

|

Salman 2021b |

Type of study: prospective observational cohort study

Setting and country: Hospital Egypt

Funding and conflicts of interest: No funding was received.

The authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: Included were all consecutive patients aged >18 and <60 years with a BMI >40 without comorbidities or a BMI >35 with comorbidities who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG)

Exclusion criteria: dangerous medical conditions preventing anesthesia, not intending to modify their habits after the procedure; psychological issues; underwent previous metabolic surgery; gestation or lactation at initial nrolment or operation. Those who proved to have other etiologies of hepatic disorders, including viral, alcohol, immune-related, drug-elicited, cholestatic, genetical, or metabolic disorders

N total at baseline: N=67

Important prognostic factors2: mean age 44.4 ± 5.7 years;

male 52.2% (n = 35).

Mean initial weight 122.1 ± 14.0 kg |

MASH features pre-one‑anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB)

|

MASH features post-OAGB

|

Length of follow-up: 15 months

Loss-to-follow-up: No loss to follow-up reported

Incomplete outcome data: None

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Resolution of MASH; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 62/71 (92.5%) Post-bariatric surgery: 34/67 (50.8%) RR= 0.55 (0.43 to 0.70)

Resolution of fibrosis; RR (95% CI) Pre-bariatric surgery: 61/67 (91%) Post-bariatric surgery: 43/67 (64.2%) RR= 0.70 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.86) |

The authors conclude that OAGB resolved MASH from nearly 42% of patients and reduced the histological features of MASLD 15 months after surgery.

|

Risk of bias tables

Risk of bias table for systematic reviews

|

|

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies? Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies? Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable? Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account? Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Lee, 2019 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Unclear1 |

1 Potential conflicts of interest are not reported for the individual studies.

Risk of bias table for interventions studies

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables? |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Agarwal 2021 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Consecutive patients were follow-up pre and post bariatric surgery |

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was based on histological biopsy |

Definitely yes

Reason: participants were followed up pre-and post-bariatric surgery to determine improvement on MAFLD features present at baseline. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no incomplete data. Only patients with adequate follow-up were included |

Definitely yes

Reason: There were no co-interventions |

Low

|

|

Cabré, 2019 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Consecutive patients were follow-up pre and post LSG |

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was based on histological biopsy |

Definitely yes

Reason: participants were followed up pre-and post-LSG to determine improvement on MAFLD features present at baseline. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no incomplete data. Only patients with adequate follow-up were included |

Definitely yes

Reason: There were no co-interventions |

Low

|

|

Esquivel, 2018 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Consecutive patients were follow-up pre and post LSG |

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was based on histological biopsy |

Definitely yes

Reason: participants were followed up pre-and post-LSG to determine improvement on MAFLD features present at baseline. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no incomplete data. Only patients with adequate follow-up were included |

Definitely yes

Reason: There were no co-interventions |

Low

|

|

Garg, 2018 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Consecutive patients were follow-up pre and post bariatric surgery |

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was based on histological biopsy |

Definitely yes

Reason: participants were followed up pre-and post-bariatric surgery to determine improvement on MAFLD features present at baseline. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no incomplete data. Only patients with adequate follow-up were included |

Definitely yes

Reason: There were no co-interventions |

Low

|

|

Lassailly, 2020 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Consecutive patients were follow-up pre and post bariatric surgery |

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was based on histological biopsy |

Definitely yes

Reason: participants were followed up pre-and post-bariatric surgery to determine improvement on MAFLD features present at baseline. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no incomplete data. Only patients with adequate follow-up were included |

Definitely yes

Reason: There were no co-interventions |

Low

|

|

Salman, 2020 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Consecutive patients were follow-up pre and post LSG |

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was based on histological biopsy |

Definitely yes

Reason: participants were followed up pre-and post-LSG to determine improvement on MAFLD features present at baseline. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no incomplete data. Only patients with adequate follow-up were included |

Definitely yes

Reason: There were no co-interventions |

Low

|

|

Salman, 2021a |

Definitely yes

Reason: Consecutive patients were follow-up pre and post LSG |

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was based on histological biopsy |

Definitely yes

Reason: participants were followed up pre-and post-LSG to determine improvement on MAFLD features present at baseline. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no incomplete data. Only patients with adequate follow-up were included |

Definitely yes

Reason: There were no co-interventions |

Low

|

|

Salman 2021b |

Definitely yes

Reason: Consecutive patients were follow-up pre and post-OAGB |

Probably yes

Reason: Exposure was based on histological biopsy |

Definitely yes

Reason: participants were followed up pre-and post-OAGB to determine improvement on MAFLD features present at baseline. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria. |

Probably yes

Reason: confounding variables were part of the exclusion criteria |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: There was no incomplete data. Only patients with adequate follow-up were included |

Definitely yes

Reason: There were no co-interventions |

Low

|

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Search 1: systematic reviews and RCTs |

|

|

Froylich D, Corcelles R, Daigle C, Boules M, Brethauer S, Schauer P. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a comparative study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016 Jan;12(1):127-31. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.04.004. Epub 2015 Apr 8. PMID: 26077701. |

Included in Systematic Review Lee (2019) |

|

Jamialahmadi T, Jangjoo A, Rezvani R, Goshayeshi L, Tasbandi A, Nooghabi MJ, Rajabzadeh F, Ghaffarzadegan K, Mishamandani ZJ, Nematy M. Hepatic Function and Fibrosis Assessment Via 2D-Shear Wave Elastography and Related Biochemical Markers Pre- and Post-Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obes Surg. 2020 Jun;30(6):2251-2258. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04452-0. PMID: 32198617. |

C does not meet PICO |

|

Ahmed S, Pouwels S, Parmar C, Kassir R, de Luca M, Graham Y, Mahawar K; Global Bariatric Research Collaborative. Outcomes of Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: a Systematic Review. Obes Surg. 2021 May;31(5):2255-2267. doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05289-x. Epub 2021 Feb 17. PMID: 33595790. |

P does not meet PICO |

|

Baldwin D, Chennakesavalu M, Gangemi A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass against laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for amelioration of NAFLD using four criteria. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019 Dec;15(12):2123-2130. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2019.09.060. Epub 2019 Sep 18. PMID: 31711944. |

P does not meet PICO |

|

Bower G, Toma T, Harling L, Jiao LR, Efthimiou E, Darzi A, Athanasiou T, Ashrafian H. Bariatric Surgery and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: a Systematic Review of Liver Biochemistry and Histology. Obes Surg. 2015 Dec;25(12):2280-9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1691-x. PMID: 25917981. |

O does not meet PICO |

|

Chavez-Tapia NC, Tellez-Avila FI, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Mendez-Sanchez N, Lizardi-Cervera J, Uribe M. Bariatric surgery for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in obese patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20;2010(1):CD007340. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007340.pub2. PMID: 20091629; PMCID: PMC7208314. |

Lee (2019) is a more recent systematic review and of better quality |

|

de Brito E Silva MB, Tustumi F, de Miranda Neto AA, Dantas ACB, Santo MA, Cecconello I. Gastric Bypass Compared with Sleeve Gastrectomy for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2021 Jun;31(6):2762-2772. doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05412-y. Epub 2021 Apr 13. PMID: 33846949. |

Lee (2019) includeds the same references but is of better quality |

|

Fakhry TK, Mhaskar R, Schwitalla T, Muradova E, Gonzalvo JP, Murr MM. Bariatric surgery improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019 Mar;15(3):502-511. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.12.002. Epub 2018 Dec 6. PMID: 30683512. |

Lee (2019) is a more recent systematic review and of better quality |

|

Jan A, Narwaria M, Mahawar KK. A Systematic Review of Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Obes Surg. 2015 Aug;25(8):1518-26. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1727-2. PMID: 25982807. |

P does not meet PICO |

|

Keleidari B, Mahmoudieh M, Gorgi K, Sheikhbahaei E, & Shahabi S. Hepatic failure after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Hepatitis Monthly. 2019; 19(1). |

Wrong publication type (no meta analysis) |

|

Laursen TL, Hagemann CA, Wei C, Kazankov K, Thomsen KL, Knop FK, Grønbæk H. Bariatric surgery in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - from pathophysiology to clinical effects. World J Hepatol. 2019 Feb 27;11(2):138-149. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i2.138. PMID: 30820265; PMCID: PMC6393715. |

Wrong publication type (no meta analysis) |

|

Mummadi RR, Kasturi KS, Chennareddygari S, Sood GK. Effect of bariatric surgery on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Dec;6(12):1396-402. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.012. Epub 2008 Aug 19. PMID: 18986848. |

Lee (2019) is a more recent systematic review and of better quality |

|

Panunzi S, Maltese S, Verrastro O, Labbate L, De Gaetano A, Pompili M, Capristo E, Bornstein SR, Mingrone G. Pioglitazone and bariatric surgery are the most effective treatments for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A hierarchical network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021 Apr;23(4):980-990. doi: 10.1111/dom.14304. Epub 2021 Jan 15. PMID: 33368954. |

C does not meet PICO |

|

Baltasar A, Serra C, Pérez N, Bou R, Bengochea M. Clinical hepatic impairment after the duodenal switch. Obes Surg. 2004 Jan;14(1):77-83. doi: 10.1381/096089204772787338. PMID: 14980038. |

P does not meet PICO |

|

Billeter AT, Senft J, Gotthardt D, Knefeli P, Nickel F, Schulte T, Fischer L, Nawroth PP, Büchler MW, Müller-Stich BP. Combined Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Sleeve Gastrectomy or Gastric Bypass?-a Controlled Matched Pair Study of 34 Patients. Obes Surg. 2016 Aug;26(8):1867-74. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-2006-y. PMID: 26660688. |

P does not meet PICO |

|

Sherf-Dagan S, Zelber-Sagi S, Zilberman-Schapira G, Webb M, Buch A, Keidar A, Raziel A, Sakran N, Goitein D, Goldenberg N, Mahdi JA, Pevsner-Fischer M, Zmora N, Dori-Bachash M, Segal E, Elinav E, Shibolet O. Probiotics administration following sleeve gastrectomy surgery: a randomized double-blind trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018 Feb;42(2):147-155. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.210. Epub 2017 Aug 30. PMID: 28852205. |

I does not meet PICO |

|