Standaard beeldvorming

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de minimale standaard beeldvorming bij een kind met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel?

De uitgangsvraag omvat de volgende deelvragen:

- X-thorax: Wanneer is een X-thorax geïndiceerd?

- Abdomen: Wat zijn de indicaties voor een FAST/e-FAST?

- X-bekken: Wanneer is een X-bekken geïndiceerd?

Aanbeveling

Maak in principe bij elk kind met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel standaard een X-thorax en X-bekken.

Uitzonderingen voor het maken van een X-bekken zijn:

- Indien de patiënt ter plaatse van het ongeval nog heeft gelopen en er geen afwijkingen bij lichamelijk onderzoek zijn.

- Als de kliniek en het trauma mechanisme onverdacht is voor bekkenletsel.

Indien er een directe indicatie is voor een CT-thorax en/of CT-abdomen kan er voor gekozen worden om de conventionele beeldvorming over te slaan, mits er een CT op of nabij de traumakamer staat.

Verricht e-FAST bij de hemodynamisch instabiele traumapatiënt als snelle diagnostiek naar het bloedingsfocus.

Maak in principe bij een kind met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel met verdenking op of niet te excluderen buikletsel een e-FAST, houdt hierbij wel rekening met de relatief lage sensitiviteit van de e-FAST voor het opsporen van intra-abdominaal letsel.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Bij de acute traumaopvang worden de X-thorax en X-bekken al lange tijd als standaard modaliteiten verricht. Het bewezen nut van de beeldvorming gecombineerd met de snelheid en relatief lage stralingsbelasting maakt dat de werkgroep dit als standaard beeldvorming ziet bij de trauma-opvang van kinderen. Er is derhalve geen systematische literatuuranalyse gedaan om dit ter discussie te stellen. Een X-thorax geeft snel informatie over ernstige potentieel levensbedreigende letsels: pneumothorax (eventuele spannings component), hematothorax, longcontusie en afwijkingen aan het mediastinum. Daarnaast geeft een X-thorax duidelijke informatie over de positie van tube, maagsonde en lijnen.

Bij elke multitrauma opvang worden er derhalve standaard een X-thorax en X-bekken gemaakt, dit is overeenkomend met de volwassen populatie. Wel komen bekkenfracturen veel minder vaak voor bij kinderen.

Er is een aantal uitzonderingen op het maken van een standaard X-bekken:

- Als patiënt ter plaatste van het ongeval nog gelopen heeft en er bij lichamelijk onderzoek geen afwijkingen zijn. Testen van stabiliteit is onbetrouwbaar bij jongere kinderen.

- Als het letsel of traumamechanisme volstrekt onverdacht is voor bekkenletsel, en er bij lichamelijk onderzoek geen afwijkingen zijn.

Om onnodig tijdsverlies te voorkomen is het van belang dat het duidelijk is wanneer er een indicatie bestaat voor het vervaardigen van een FAST/e-FAST. Wanneer blijkt dat er situaties zijn waarin het uitvoeren van FAST/e-FAST niet zinvol is, zou dit onder andere tijdswinst in een potentieel levensbedreigende situatie kunnen betekenen. Anderzijds zijn er ook situaties waarbij de FAST/e-FAST juist tijdswinst oplevert, bijvoorbeeld in het geval van een instabiele patiënt waarbij de FAST/e-FAST juist extra preoperatieve informatie kan geven, zoals het aantonen van een mogelijke bloedingsfocus. Er is een literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de diagnostische accuratesse van initiële trauma opvang met en zonder FAST/e-FAST waarbij ook is gekeken naar de uitkomstmaten mortaliteit, veranderen in klinisch handelen, morbiditeit en tijdswinst.

De beschikbare literatuur is voornamelijk uit Amerika afkomstig en niet goed te vergelijken met de Nederlandse setting. De werkgroep vermoedt dat in deze studies voornamelijkpatiënten met een hogere ISS score zijn geïncludeerd, waardoor de studies een onvolledig beeld geven en er dus sprake is van bias. De doelpopulatie van deze richtlijn betreft alle patiënten die gepresenteerd worden na trauma, variërend van lage tot hoge ISS scores. Tot deze populatie behoren ook patiënten die hemodynamisch stabiel zijn, met een lage verdenking op intra-abdominaal letsel. Dit is juist de groep waarbij een CT-abdomen vaak geen gevolgen heeft voor het beleid en/of de behandeling van de patiënt in de acute setting en waarbij dus onnodige stralingsbelasting voorkomen zou kunnen worden. Het betreft hier dus een lage a-priori kans op abdominaal letsel. De meerwaarde van aanvullend onderzoek hangt af van de a-priori kans op abdominaal letsel, bepaald door traumamechanisme, anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek.

Ook wordt in de beschikbare studies de e-FAST verricht door verschillende specialismen, met mogelijk beperktere expertise. De werkgroep is van mening dat het gebruik van e-FAST in de traumasetting in Nederland ten opzichte van in andere landen meer geaccepteerd is en acht het daarom waarschijnlijk dat er ook meer expertise is op dit gebied. De werkgroep denkt daarom dat de conclusies uit de literatuuranalyse niet zomaar vertaald kunnen worden naar aanbevelingen voor de patiëntenpopulatie in de traumasetting in Nederland.

Conform de volwassen literatuur is de sensitiviteit van het e-FAST onderzoek laag. Het doel van de e-FAST is het aantonen van intra-abdominaal vocht, waarbij we een onderscheid kunnen maken tussen hemodynamische stabiele en instabiele patiënten in combinatie met het trauma mechanisme.

Bij een hemodynamisch instabiele patiënt is een relatief snelle en stralingsloze e-FAST een betekenisvol onderzoek om richting te geven aan het behandel plan, bijvoorbeeld wel of geen laparotomie. Het e-FAST onderzoek levert dan tijdswinst op ten opzichte van de CT-abdomen. Bij de hemodynamisch stabiele patiënt zal de meerwaarde van de e-FAST mede afhangen van de kliniek en het traumamechanisme, met andere woorden: de a-priori kans op intra-abdominaal letsel. Een e-FAST geeft hier in ieder geval tijd en rust om zo gelijk een verder beleid te bepalen. De keuze voor aanvullend onderzoek of observatie is aan het traumateam.

Het volledig weglaten van de e-FAST bij kindertrauma vindt de werkgroep niet wenselijk, gezien het risico dat veel laagdrempeliger een CT-abdomen gemaakt zal gaan worden. Juist dit willen we gezien de extra/ onnodige stralingsbelasting voorkomen. Het gebruik van de e-FAST kan leiden tot een lager aantal CT’s (Scaife, 2013). Dit beleid is ook conform de volwassen richtlijn.

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat mortaliteit was geen literatuur beschikbaar en ook blijft het onduidelijk of het klinisch handelen verandert als gevolg van het uitvoeren van een e-FAST. De totale bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten is zeer laag. Dit komt voornamelijk omdat de studies die werden geïncludeerd in de SR van Liang (2019) een risico op bias hebben vanwege de flow en timing. Daarnaast rapporteren de individuele studies maar een laag aantal patiënten en/of events waardoor er sprake kan zijn van imprecisie. Het is daarom goed mogelijk dat nieuwe studies de conclusies kunnen veranderen.

De werkgroep is van mening dat gezien de stralingsbelasting er in eerste instantie gekozen moet worden voor een e-FAST. Het valt te overwegen om, indien mogelijk, direct een CT-thorax/abdomen te maken wanneer er sprake is van een hemodynamisch stabiele patiënt en er een serieuze verdenking is op ernstig letsel.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

De e-FAST is een praktisch onderzoek voor de patiënt omdat het een makkelijke tool is die vrijwel altijd en overal beschikbaar is. De patiënt hoeft niet verplaatst te worden en het is een snel non-invasief onderzoek zonder stralingsbelasting, wat juist in de populatie van deze richtlijn nog zwaarder weegt dan in de volwassen richtlijn. Het grootste nadeel is dat de sensitiviteit laag is en dat er meestal weinig consequenties aan de e-FAST worden verbonden, zoals overigens ook geldt voor de CT.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het vervaardigen van een e-FAST brengt minimale extra kosten met zich mee. Er moet 24/7 een radioloog (in opleiding) of ander persoon met dergelijke expertise beschikbaar zijn.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De X-thorax en X-bekken zijn al sinds jaar en dag opgenomen als standaard modaliteiten. Ook de e-FAST is een modaliteit die in alle centra in Nederland beschikbaar is waardoor beeldvorming snel verricht kan worden. De werkgroep verwacht dan ook geen problemen wat betreft de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie wat betreft de opname van deze modaliteit als standaard beeldvorming bij de trauma-opvang van kinderen.

Op basis van de beschikbare literatuur is het lastig conclusies te trekken over de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van de interventies. Alleen Holmes (2017) geeft een waarde bij hemodynamisch stabiele patiënten. Echte harde morele of ethische bezwaren kunnen er tegen een e-FAST niet gemaakt worden. Een echte waarde is moeilijk te geven. Er is veel variatie en we willen in de richtlijn uniformiteit nastreven.

De beschikbare literatuur is voornamelijk uit Amerika afkomstig. De werkgroep vermoed dat hier veel CT-scans en relatief weinig e-FAST onderzoeken worden vervaardigd. Expertise van de echografist(e) voor e-FAST is in de literatuur niet altijd duidelijk omschreven. Uit de literatuur blijkt dat de e-FAST vaak wordt verricht door andere specialisten dan de radioloog, zoals veelal in Nederland gebeurt. Een voorwaarde voor het succes van de e-FAST is expertise van de echografist(e).

Rationale van de aanbevelingen

Bij de acute traumaopvang zijn de X-thorax en X-bekken opgenomen als standaard modaliteiten. Bij elke multitrauma opvang worden er derhalve standaard een X-thorax en X-bekken gemaakt, dit is overeenkomend met de volwassen populatie. Houdt hierbij wel in het achterhoofd dat bekkenfracturen veel minder vaak voorkomen bij kinderen.

De X-thorax en X-bekken gaan gepaard met relatief lage stralingsbelasting en zijn erg snel, niet invasief en kunnen levensbedreigende letsels aantonen. Er is geen verder onderzoek gedaan om de waarde opnieuw te toetsen.

Op basis van expert opinion en beperkte beschikbare literatuur is de werkgroep van mening dat de e-FAST een plek heeft als modaliteit bij de acute beeldvorming. De beschikbare literatuur is niet direct toepasbaar op de huidige Nederlandse trauma opvang. In de literatuur wordt een CT-abdomen laagdrempelig gebruikt om zekerheidshalve alle traumatische bevindingen te diagnosticeren bij zowel stabiele als instabiele patiënten. Deze aanpak is defensiever dan de Nederlandse aanpak. De e-FAST moet gezien worden als onderdeel van de gehele strategie van de trauma opvang, inclusief lichamelijk onderzoek en laboratorium onderzoek. De e-FAST geeft direct belangrijke informatie, waarbij of afwachtend beleid, of direct aanvullend onderzoek of interventie volgt. De werkgroep is van mening, ondersteund door literatuur, dat het gebruik van e-FAST leidt tot minder aanvullende CT-onderzoeken in de initiële setting.

De combinatie van traumamechanisme, lichamelijk onderzoek en hemodynamiek is leidend om als traumateam een keuze te maken. Bij hoge verdenking op ernstig letsel is een CT-scan gerechtvaardigd, al dan niet voorafgegaan door een e-FAST. Het traumateam dient op de hoogte te zijn van beperkingen van de e-FAST. De relatieve onderdiagnostiek wordt in secundaire en tertiaire survey opgepakt bij klinisch relevante afwijkingen, met zo nodig herhalen van de e-FAST of toch aanvullend CT of MRI onderzoek. Bevindingen op CT-abdomen en e-FAST bij primaire survey leiden bij kinderen niet altijd tot interventie, waar dit bij volwassenen vaker wel zo is. Wanneer het behandelend team op de hoogte is van de beperkingen van de e-FAST, zal bij klinische verslechtering van het kind het team direct ingrijpen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In de acute fase wordt veelal gebruik gemaakt van drie snelle beeldvormende modaliteiten: de X-thorax, X-bekken en de extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (e-FAST). Bij vrijwel iedere hoogenergetische traumaopvang worden een X-thorax en X-bekken gemaakt. Er is praktijkvariatie bij het gebruiken van e-FAST, waarbij de aanvullende waarde onderwerp is van discussie. Wanneer blijkt dat er situaties (patiëntgroepen, type trauma) zijn waarin het initieel uitvoeren van e-FAST niet zinvol is, zou dit onder andere tijdswinst in een potentieel levensbedreigende situatie kunnen betekenen.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

- GRADE |

Mortality Due to the lack of studies reporting the outcome measure mortality, it was not possible to draw a conclusion for this outcome. |

|

Very low GRADE |

Changes in clinical course It remains unclear whether initial examination with FAST/e-FAST changes the clinical course in children with potentially multiple or life-threatening injuries in comparison with initial trauma examination without FAST/e-FAST.

Sources: (Calder, 2017; Scaife, 2013; Vasquez, 2019) |

|

Low GRADE |

Diagnostic accuracy The initial trauma examination with FAST/e-FAST does possibly not have added value in children with potentially multiple or life-threatening injuries in comparison with initial trauma examination without FAST/e-FAST based on the diagnostic accuracy.

Sources: (Liang, 2019; Vasquez, 2019; Zeeshan, 2019) |

|

- GRADE |

Morbidity Due to the lack of studies reporting the outcome measure morbidity, it was not possible to draw a conclusion for this outcome. |

|

Very low GRADE |

Time to CT It remains unclear whether initial examination with FAST/e-FAST changes the time to CT in children with potentially multiple or life-threatening injuries in comparison with initial trauma examination without FAST/e-FAST.

Sources: (Holmes, 2017) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Systematic review

The systematic review from Liang (2019) evaluated the utility of the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination for diagnosis of intra-abdominal injury in children presenting with blunt abdominal trauma. Medical literature published in PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science from January 1966 to March 2018 was evaluated for inclusion. Studies were included when they examined pediatric patients who underwent a FAST after blunt trauma, and if the FAST was completed and interpreted by a (pediatric) emergency medicine physician or surgical staff at the bedside. Narrative reviews, case-control studies, retrospective studies, case reports, and studies with FAST examinations performed by radiology staff were excluded. In addition, studies were excluded of patients who died in the emergency department, were hemodynamically unstable, or met the criteria for emergent surgical exploration. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2). In total, 8 prospective studies were included encompassing 2,135 patients, of which 289 were diagnosed with intra-abdominal injury. All included studies diagnosed the presence or absence of intra-abdominal injuries with either CT-scans, laparotomy, hospital observation, and/or outpatient follow-up as a reference standard to confirm FAST results. The included studies had variable quality, with most at risk for partial and differential verification bias. A meta-analysis was performed to estimate the pooled diagnostic accuracy.

As the systematic review only reported the diagnostic accuracy, the individual studies were consulted for the remaining outcomes of interest. The studies that reported additional outcome measures are described below:

The RCT of Holmes (2017) determined whether FAST examination during initial evaluation of injured children improved clinical care. The study included 975 hemodynamically stable children and adolescents (< 18 years old) treated for blunt torso trauma in a level I trauma center. Patients were included when they presented to the emergency department within 24 hours of the traumatic event. Patients were excluded when they had hypotension, a Glasgow Coma Scale score < 9, an abdominal seat belt sign, penetrating trauma, when they were transferred from another hospital, or when they had a known disease resulting in intraperitoneal fluid (e.g. liver failure or ventriculoperitoneal shunts). Patients were stratified in three age categories (< 3 years, 3 to 9.99 years, ≥ 10 years) and randomized in blocks of 20 within these age cohorts. Patients were randomly assigned to standard trauma evaluation with FAST examination or to standard trauma evaluation alone. In total, 460 patients received standard trauma evaluation with FAST, and 465 received standard care alone. Data was collected from the electronic medical records from the hospitalized patients. The guardians of patients who were discharged from the emergency department were contacted 1 week after the emergency department.

The prospective observational study of Calder (2017) investigated the role of FAST for intra-abdominal injury and intra-abdominal injuries that require acute intervention in children after blunt abdominal trauma. The study included all patients (< 16 years old) at pediatric trauma centers. Patients were excluded when they presented later than 6 hours after the injury, when they have had abdominal CT imaging before arrival to the pediatric trauma center, isolated head or extremity mechanism of injury, same level fall, and/or penetrating/bum/hanging mechanism. In total, 2,188 patients were included with a mean age of 7.8 years old. 829 of these children received FAST, while 1,359 children did not receive FAST. Follow-up was 30 days or time of discharge of the hospital.

The prospective observational study of Scaife (2013) investigated whether the use of FAST might decrease CT use. The study included all patients (< 18 years old) that required trauma team activation and had potential abdominal trauma. Patients were excluded when they had abdominal imaging (CT or FAST) from a referring hospital or when they had penetrating or open abdominal wounds. Furthermore, patients were excluded when assistance was provided to the surgeon as part of training opportunities, non-surgeon use of ultrasound, and equipment malfunction. In total, 88 patients were included with a median age of 7 years old. The follow-up time was not reported.

Additional observational studies

The retrospective study of Vasquez (2019) examined the sensitivity and specificity of one lung ultrasound methodology (single-point anterior exam) as an extension of the FAST in the pediatric trauma population, compared to chest radiography or CT. The study included children (< 18 years old) identified in the trauma registry who received a lung US exam in conjunction with a FAST scan and treated between May 1, 2016 and Sept 21, 2017. The study excluded all patients that did not have complete data in the dataset or did not have confirmatory chest radiography or CT-scans. In total, 226 pediatric were included with a mean age of 9.4 years old. The chest radiography or CT-scans were used as the gold standard for diagnosis. The follow-up time was not reported.

The retrospective study of Zeeshan (2019) determined if the combination of physical examination, serum transaminases along with FAST would effectively rule out major hepatic injuries after blunt abdominal trauma in hemodynamically stable pediatric patients. The study included all pediatric patients (< 18 years old) with a blunt abdominal injury who were evaluated with CT-scans and underwent FAST on admission. The study excluded all patients who were transferred from other hospitals or dead on arrival. In total, 423 patients were included with a mean age of 11 years old. The study compared the diagnostic accuracy of physical examination and serum transaminases (AST and ALT) with and without FAST. The CT scan was used as the gold standard for diagnosis. The follow-up time was not reported.

Results

Mortality (crucial)

None of the studies reported a comparison of the mortality for trauma examination with and without e-FAST.

Changes in clinical course (crucial)

The outcome changes in clinical course was reported in three studies (Calder, 2017; Scaife, 2013; Vasquez, 2019).

The study of Vasquez (2019) reported that all true positive findings, but none of the false negatives on FAST had pulmonary contusions. None of the false negatives on FAST required intervention. When FAST was incorporated in trauma examination, no changes in clinical course were identified in comparison with chest radiography or CT.

The study of Calder (2017) reported a slightly lower CT scan utilization after the use of FAST (41%) in comparison to those who did not receive FAST (46%). However, this difference was not considered clinically relevant. Among the 27 patients with true positive FAST examinations, 12 patients received intervention. These patients all had an abnormal abdominal examination and therefore, no changes in clinical course were identified when FAST was incorporated in trauma examination for intra-abdominal injuries.

The study of Holmes (2017) reported the changes in clinical course due to the introduction of FAST and the amount of abdominal CT scans that were performed with and without the usage of FAST during trauma management. Physicians documented changes in their plans to order CTs for 25 patients after FAST examinations. In 13 cases, physicians decided not to perform a planned abdominal CT following the FAST examination, and none were diagnosed with intra-abdominal injuries. In 12 cases, physicians decided to obtain an abdominal CT when this was originally not planned. One was diagnosed with an intra-abdominal injury. In this case, the FAST examination demonstrated intraperitoneal fluid in the Morison pouch. After the development of peritonitis, the patient was found to have a jejunal injury. This indicates that changes do occur due to the addition of FAST to standard trauma evaluation. However, the proportion of patients with abdominal CT-scans was 241 of 460 (52.4%) in the group who received FAST and 254 of 465 (54.6%) in the group of patients who received standard care without FAST. The difference was 2.2% (95%CI -0.6% to 1.2%). This difference in the amount of abdominal CT-scans was not considered clinically relevant.

The study of Scaife (2013) reported the amount of cancelled CT-scans after FAST. The study reported that surgeons would have elected to cancel the abdominal CT in 42 (48%) of the cases. The FAST was negative in 40 of these cases (95%). The FAST was positive in 1 of the cases, but this patient was directly transported to the operating room and therefore CT was omitted. This difference of 48% less CT-scans after the introduction of FAST was considered clinically relevant.

Diagnostic accuracy (crucial)

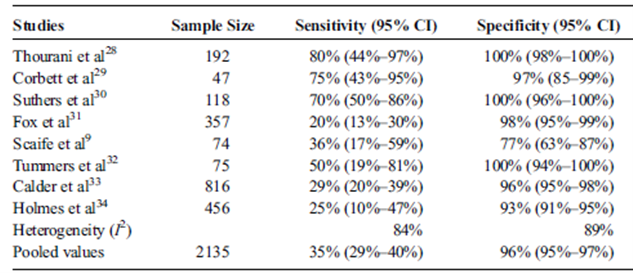

The outcome diagnostic accuracy were reported in 3 studies (Liang, 2019; Vasquez, 2019; Zeeshan, 2019). The systematic review of Liang (2019) reported the pooled values of the diagnostic accuracy of detecting intra-abdominal injuries with e-FAST (Table 1.1). The overall sensitivity of their analysis was 35% (95% confidence interval (CI) 29% to 40%) and the pooled specificity was 96% (95%CI 95% to 97%).

Table 1.1 The diagnostic accuracy of FAST examination

Source: Liang (2019)

The study of Vasquez (2019) reported the diagnostic accuracy of using single-point exam anteriorly positioned as an extension of the FAST for trauma exam, for the detection of pneumothoraces. The sensitivity of the FAST was 45.5% (95%BI 16.8 to 76.6%), the specificity was 98.6% (96.0% to 99.7%). The positive predictive value was 62.5% (31.3% to 85.9%) and the negative predictive value was 97.3% (95.4% to 98.4%).

The study of Zeeshan (2019) compared the diagnostic accuracy of trauma examination with and without FAST to detect liver injuries. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of physical examination and serum transaminases without FAST were 84%, 63%, 44%, and 97% respectively, whereas this was 97%, 95%, 87%, and 98% when FAST was included in the trauma examination. This means that the diagnostic accuracy to detect liver injuries was improved when FAST was included. The improvement for the sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value was considered clinically relevant.

Morbidity (important)

None of the studies reported the outcome measure morbidity.

Time to CT

The outcome time to CT was reported in the study of Holmes (2017). The mean time to CT was 2.65 hours (95%CI 2.44 to 2.86) in the group that received FAST, compared to 2.54 hours (95%CI 2.32 to 2.76) in the group that received standard care alone. The difference was 0.11 hours (95%CI -0.20 to 0.42). This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

Mortality and morbidity

The level of evidence could not be graded for these outcome measures, as they were not reported in the included studies.

Changes in clinical course

The level of evidence regarding the changes in clinical course started low. The level of evidence regarding the changes in clinical course was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to no adjustment for potential confounders, 1 level) and because of imprecision (low number of events or included patients, 1 level). Therefore, the level of evidence was graded very low.

Diagnostic accuracy

The level of evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy started high. The level of evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias due to limitations in flow and timing) and because of inconsistenty (heterogeneity in study results). Therefore, the level of evidence was graded low.

Time to CT

The level of evidence regarding the changes in clinical course started low. The level of evidence regarding the changes in clinical course was downgraded by 1 level because the null value was present within the confidence interval (imprecision, 1 level). Therefore, the level of evidence was graded very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the additional value (diagnostic accuracy/effectivity) of initial trauma examination with FAST/e-FAST (chest X-ray, pelvic X-ray, FAST/e-FAST) in comparison with initial trauma examination without FAST/e-FAST in children with potentially multiple or life-threatening injuries?

P: patients children with potential multiple trauma or life threatening injury (< 16 years);

I: intervention trauma examination without FAST/e-FAST;

C: comparison trauma examination with FAST/e-FAST;

R: reference computed tomography (CT) or clinical follow-up;

O: outcome measure mortality, morbidity, time to diagnosis, changes in clinical course, and diagnostic accuracy for the detection of free fluid and trauma related organ injuries.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality, changes in clinical course, and diagnostic accuracy as critical outcome measure for decision making; and morbidity and time to diagnosis as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the guideline committee did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

The guideline committee used the standard minimal clinically (patient) important difference for the dichotomous outcome measure mortality of 10% (RR < 0.91 or > 1.10). For continuous outcome measures, a difference of 10% was considered clinically important.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase via Embase.com were searched with relevant search terms until 25th of February 2020. The detailed search strategy can be found under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 95 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: randomized controlled trials, comparative observational studies, or systematic reviews on the validity/accuracy of trauma examination with and without FAST/e-FAST in children with potential multiple trauma. In total, 22 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 19 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 3 studies were included.

Results

In total, 1 systematic review and 2 additional observational studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Calder BW, Vogel AM, Zhang J, Mauldin PD, Huang EY, Savoie KB, Santore MT, Tsao K, Ostovar-Kermani TG, Falcone RA, Dassinger MS, Recicar J, Haynes JH, Blakely ML, Russell RT, Naik-Mathuria BJ, St Peter SD, Mooney DP, Onwubiko C, Upperman JS, Zagory JA, Streck CJ. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma in children after blunt abdominal trauma: A multi-institutional analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Aug;83(2):218-224. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001546. PubMed PMID: 28590347.

- Holmes JF, Kelley KM, Wootton-Gorges SL, Utter GH, Abramson LP, Rose JS, Tancredi DJ, Kuppermann N. Effect of Abdominal Ultrasound on Clinical Care, Outcomes, and Resource Use Among Children With Blunt Torso Trauma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017 Jun 13;317(22):2290-2296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6322. PubMed PMID: 28609532; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5815005.

- Liang T, Roseman E, Gao M, Sinert R. The Utility of the Focused Assessment With Sonography in Trauma Examination in Pediatric Blunt Abdominal Trauma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Mar 12. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001755. (Epub ahead of print) PubMed PMID: 30870341.

- Scaife ER, Rollins, M. D., Barnhart, D. C., Downey, E. C., Black, R. E., Meyers, R. L., Stevens, M. H., Gordon, S., Prince, J. S., Battaglia, D., Fenton, S. J., Plumb, J., & Metzger, R. R. (2013). The role of focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) in pediatric trauma evaluation. Journal of pediatric surgery, 48(6), 1377–1383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.038.

- Vasquez, D. G., Berg, G. M., Srour, S. G., & Ali, K. (2020). Lung ultrasound for detecting pneumothorax in injured children: preliminary experience at a community-based Level II pediatric trauma center. Pediatric radiology, 50(3), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-019-04509-y.

- Zeeshan M, Hamidi M, O'Keeffe T, Hanna K, Kulvatunyou N, Tang A, Joseph B. Pediatric Liver Injury: Physical Examination, Fast and Serum Transaminases Can Serve as a Guide. J Surg Res. 2019 Oct;242:151-156. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2019.04.021. Epub 2019 May 9. PubMed PMID: 31078899

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies

Research question: What is the additional value (diagnostic accuracy/effectivity) of initial trauma examination with e-FAST (X-thorax, X-pelvis, e-FAST) in comparison with initial trauma examination without e-FAST in children with potentially multiple or life-threatening injuries?

| Study reference | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | Index test | Reference test | Follow-up | Outcome measures and effect size | Comments |

|

Liang, 2019

Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs / cohort studies.

Literature search up to March 2018

A: Thourani, 1998

Study design:

Setting and Country:

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion criteria SR: Studies were included if they examined pediatric patients who underwent a FAST after blunt trauma, and if the FAST was completed and interpreted by PEM, EM, or surgical staff at the

Exclusion criteria SR: Studies were excluded if they did not provide sufficient data to construct a 2 x 2 table. Narrative review, case-control studies,

8 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

mean age (years)

Sex:

Prevalence IAI: |

Describe index test:

Cut-off point(s):

Comparator test : |

Describe reference test:

Cut-off point(s): |

Time between the index test en reference test:

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available?

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? |

Outcome measure-1

Pooled effect (random effects model): |

IAI = intra-abdominal injuries

Heterogeneity: Interstudy

Author’s conclusion: In hemodynamically stable pediatric patients presenting to the ED with blunt abdominal trauma, a negative POCUS FAST examination result alone cannot preclude further workup for IAI. |

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

Research question: What is the additional value (diagnostic accuracy/effectivity) of initial trauma examination with e-FAST (X-thorax, X-pelvis, e-FAST) in comparison with initial trauma examination without e-FAST in children with potentially multiple or life-threatening injuries?

| Study reference | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | Index test | Reference test | Follow-up | Outcome measures and effect size | Comments |

| Zeeshan, 2019 |

Type of study1:

Setting and country: trauma center, US.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding |

Inclusion criteria: All pediatric patients (< 18 years) with a blunt abdominal

Exclusion criteria: Patients who were transferred from other hospitals or dead on arrival.

N= 423 patients.

Other important characteristics: Most patients |

Describe index test:

Comparator test2 :

Cut-off point(s):

For serum transaminases:

For FAST: no cut-off point was described. |

Describe reference test3:

Cut-off point(s): not described. |

Time between the index test en reference test: both occurred on admission.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available?

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? NA. |

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available)4:

Diagnostic accuracy:

Index test:

Comparison test: |

Author’s conclusion: Our study has shown that combining FAST, PE, and ALT and AST levels had significantly increased both the sensitivity and negative predictive value for screening pediatric blunt trauma

Subgroup: hemodynamically stable children. |

| Vasquez, 2019 |

Type of study: observational study (retrospective).

Setting and country: community-based Level II pediatric trauma center.

Funding and conflicts of interest: none.

|

Inclusion criteria: We searched the trauma registry and medical records of pediatric patients who received a lung US exam in conjunction

Exclusion criteria: We excluded children from analysis if they: (1) did not have a lung US/ FAST assessment,

N= 226

Prevalence: 11 confirmed pneumothoraces

Mean age ± SD: 9.4 years (SD 5.8 years).

Sex: 59.7% M

Other important characteristics: NA |

Describe index test:

Cut-off point(s):

Comparator test:

Cut-off point(s): Lung US findings were confirmed as true or false by chest radiography or CT scans. |

Describe reference test:

Cut-off point(s): Lung US findings were confirmed as true or false by chest radiography or CT scans.

|

Time between the index test en reference test: not reported.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? None.

N (%)

Reasons for incomplete outcome data described? Not applicable.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Mortality: N=10 (4.4%).

Changes in clinical course:

Diagnostic accuracy:

Specificity: Specificity Morbidity: not reported. Time savings: not reported. |

Study describes the sensitivity and specificity of lung pneumothoraces. |

1 In geval van een case-control design moeten de patiëntkarakteristieken per groep (cases en controls) worden uitgewerkt. NB; case control studies zullen de accuratesse overschatten (Lijmer et al., 1999)

2 Comparator test is vergelijkbaar met de C uit de PICO van een interventievraag. Er kunnen ook meerdere tests worden vergeleken. Voeg die toe als comparator test 2 etc. Let op: de comparator test kan nooit de referentiestandaard zijn.

3 De referentiestandaard is de test waarmee definitief wordt aangetoond of iemand al dan niet ziek is. Idealiter is de referentiestandaard de Gouden standaard (100% sensitief en 100% specifiek). Let op! dit is niet de “comparison test/index 2”.

4 Beschrijf de statistische parameters voor de vergelijking van de indextest(en) met de referentietest, en voor de vergelijking tussen de indextesten onderling (als er twee of meer indextesten worden vergeleken).

Risk of bias assessment diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS II, 2011)

Research question: What is the additional value (diagnostic accuracy/effectivity) of initial trauma examination with e-FAST (X-thorax, X-pelvis, e-FAST) in comparison with initial trauma examination without e-FAST in children with potentially multiple or life-threatening injuries?

| Study reference | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | Comments with respect to applicability |

| Zeeshan, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled?

Was a case-control design avoided?

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard?

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? |

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition?

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard?

Did all patients receive a reference standard?

Did patients receive the same reference standard?

Were all patients included in the analysis? |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question?

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question?

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? |

|

CONCLUSION:

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION:

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION:

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION

RISK: LOW |

||

| Vasquez, 2019 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled?

Was a case-control design avoided?

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard?

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? |

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition?

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard?

Did all patients receive a reference standard?

Did patients receive the same reference standard?

Were all patients included in the analysis? |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question?

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question?

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? |

|

CONCLUSION:

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION:

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION:

RISK: UNCLEAR |

CONCLUSION

RISK: LOW |

Judgments on risk of bias are dependent on the research question: some items are more likely to introduce bias than others, and may be given more weight in the final conclusion on the overall risk of bias per domain:

Patient selection:

- Consecutive or random sample has a low risk to introduce bias.

- A case control design is very likely to overestimate accuracy and thus introduce bias.

- Inappropriate exclusion is likely to introduce bias.

Index test:

- This item is similar to “blinding” in intervention studies. The potential for bias is related to the subjectivity of index test interpretation and the order of testing.

- Selecting the test threshold to optimise sensitivity and/or specificity may lead to overoptimistic estimates of test performance and introduce bias.

Reference standard:

- When the reference standard is not 100% sensitive and 100% specific, disagreements between the index test and reference standard may be incorrect, which increases the risk of bias.

- This item is similar to “blinding” in intervention studies. The potential for bias is related to the subjectivity of index test interpretation and the order of testing.

Flow and timing:

- If there is a delay or if treatment is started between index test and reference standard, misclassification may occur due to recovery or deterioration of the condition, which increases the risk of bias.

- If the results of the index test influence the decision on whether to perform the reference standard or which reference standard is used, estimated diagnostic accuracy may be biased.

- All patients who were recruited into the study should be included in the analysis, if not, the risk of bias is increased.

Judgement on applicability:

Patient selection: there may be concerns regarding applicability if patients included in the study differ from those targeted by the review question, in terms of severity of the target condition, demographic features, presence of differential diagnosis or co-morbidity, setting of the study and previous testing protocols.

Index test: if index tests methods differ from those specified in the review question there may be concerns regarding applicability.

Reference standard: the reference standard may be free of bias but the target condition that it defines may differ from the target condition specified in the review question.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

| Liang, 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 11-05-2022

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 01-03-2022

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de radiologische diagnostiek bij de acute trauma-opvang van kinderen.

Werkgroep

- Drs. J. (Joost) van Schuppen, radioloog, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVvR (voorzitter)

- Drs. M.H.G. (Marjolein) Dremmen, radioloog, Erasmus MC te Rotterdam, NVvR (voorzitter)

- Dr. R. (Roel) Bakx, kinderchirurg, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVvH

- Drs. L.G.J. (Linda) Bel, SEH-arts, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep te Alkmaar, NVSHA

- Drs. I.G.J.M. (Ivar) de Bruin, traumachirurg, UMC Utrecht te Utrecht, NVvH (voorzitter)

- Ir. D.J.W. (Dennis) Hulsen, klinisch fysicus, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis te Den Bosch, NVKF

- Drs. M. (Maayke) Hunfeld, kinderneuroloog, Erasmus MC te Rotterdam, NVN

- Drs. D.R.J. (Dagmar) Kempink, orthopeed, LUMC te Leiden en Erasmus MC te Rotterdam, NOV

- Drs. M.J. (Maeke) Scheerder, radioloog, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVvR

- Dr. A. (Annelie) Slaar, radioloog, Dijklander Ziekenhuis te Hoorn, NVvR

- Drs. L. (Linda) van Wagenberg, anesthesioloog-kinderintensivist, UMC Utrecht te Utrecht – onder volledig mandaat van Prof. dr. J.B.M. (Job) van Woensel, kinderintensivist, Emma Kinderziekenhuis Amsterdam UMC, NVK

klankbordgroep:

- Dr. L.N.A. (Leon) van Adrichem, plastisch chirurg, Velthuis kliniek te Rotterdam en Den Haag, NVPC

- Dr. D.R. (Dennis) Buis, neurochirurg, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVvN

- Drs. M.M.A.C. (Martine) van Doorn, interventieradioloog, NVvR

- Dr. L. Dubois, (Leander) MKA-chirurg, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVMKA

- Dr. M.J.W. (Marcel) Greuter, klinisch fysicus, UMCG te Groningen, NVKF

- Dr. L.A. (Luitzen) Groen, kinderuroloog, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVU

- Drs. M. (Miranda) Prins, anesthesioloog-intensivist, Isala te Zwolle, NVA

Met ondersteuning van

- Drs. K. (Kristie) Venhorst, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. R. (Romy) Zwarts - van de Putte, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. M. (Miriam) van der Maten, junior literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Schuppen |

Radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC |

- Lid bestuur sectie kinderradiologie NVvR - Lid bestuur Stichting Bevordering Kinderradiologie (SBKR) |

Geen 6-5-2019 |

Geen actie vereist, geen relevante belangen |

|

Dremmen |

Radioloog, Erasmus MC (kinderradiologie) |

- 2 dagen cursus gegeven over kindertrauma (betaald) |

Geen 26-4-2019 |

Geen |

|

Bruin, de |

Traumachirurg, UMC Utrecht |

- ATLS instructeur - Lid diverse beroepsverenigingen: NVvH, NVT, AO-trauma, ESTES, OTA |

Geen 24-5-2019 |

Geen |

|

Slaar |

Radioloog, Dijklander ziekenhuis, locatie Hoorn |

- Eigenaar Diagnose in beeld: 3-wekelijkse radiologische casuïstiek per app of per e-mail (onbetaald) |

Geen 24-4-2019 |

Geen |

|

Scheerder |

Radioloog, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC |

- Voorzitter sectie Acute Radiologie Nederland (onbetaald) - Voorzitter Richtlijn initiële radiodiagnostiek bij volwassen traumapatiënten (betaald) |

Geen 1-5-2019 |

Geen |

|

Bakx |

Kinderchirurg, Amsterdam UMC |

- Bestuurslid SHK (onbetaald) - Voorzitter richtlijnencommissie NVvH (onbetaald) |

Geen 4-6-2019 |

Geen |

|

Hunfeld |

Neuroloog – kinderneuroloog, Erasmus MC – Sophia kinderziekenhuis |

- |

Geen 1-5-2019 |

Geen |

|

Kempink |

Kinder-orthopaedisch chirurg – traumatoloog werkzaam in: Erasmus MC - Sophia Kinderziekenhuis (70%) en LUMC (30%) |

- |

Geen 9-5-2019 |

Geen |

|

Wagenberg, van |

Anesthesioloog- kinderintensivist , Wilhelmina kinderziekenhuis |

- |

Geen 23-7-2019 |

Geen |

|

Bel |

SEH-arts, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep |

- |

Geen 8-7-2019 |

Geen |

|

Hulsen |

Klinisch Fysicus, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis |

- Externe promovendus, MUMC+ (onbetaald) - Secretaris commissie stralingshygiëne, NVKF (onbetaald) |

Geen 6-10-2019 |

Geen |

|

Woensel, van |

Hoofd PICU Amsterdam UMC |

- |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis heeft input gegeven in de schriftelijke Invitational conference. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten bij de radiologische diagnostiek bij de acute trauma-opvang van kinderen. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door: LNAZ, NAPA, NHG, NOV, NVK, NVKMA, NVN, NVNN, NVZ, NVvH, NVvR, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, V&VN, ZiNL en ZN via een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. De aangedragen knelpunten (zie bijlage 1) is besproken in de werkgroep. Op basis van de verkregen input zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello, 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE-gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de aan de werkgroep deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en aan Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekverantwoording

|

Richtlijn: Radiologische diagnostiek bij de acute trauma opvang van kinderen |

|

|

Uitgangsvraag: Wat is de waarde (effectiviteit/diagnostische accuratesse) van initieel radiodiagnostisch onderzoek inclusief (e-)FAST (X-thorax, X-bekken, (e-)FAST) ten opzichte van initieel radiodiagnostisch onderzoek zonder (e-)FAST in de initiële trauma-opvang van kinderen tot 16 jaar met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel? |

|

|

Database(s): Medline, Embase |

Datum: 25-2-2020 |

|

Periode: Geen rectrictie |

Talen: Engels |

|

Literatuurspecialist: Miriam van der Maten |

|

|

Toelichting en opmerkingen: Voor deze uitgangsvraag is gezocht op de P en de I van de PICO. Voor de P (kinderen tot 16 jaar met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel) is het standaard kinderfilter gecombineerd met termen gerelateerd aan trauma/injury en verder aangevuld met kind-specifieke trauma termen zoals APLS. De zoekopdracht is verder niet gelimiteerd op datum gezien het aantal hits. |

|

Zoekopbrengst

|

|

EMBASE |

OVID/MEDLINE |

Ontdubbeld |

|

SRs |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

RCTs |

15 |

4 |

15 |

|

Observationele studies |

28 |

17 |

30 |

|

Overig |

41 |

21 |

44 |

|

Totaal |

88 |

47 |

95 |

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Embase

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medline (OVID)

|

1 ('paediatric advanced life support' or 'pediatric advanced life support').ti,ab,kf. (271) 2 (exp "Wounds and Injuries"/ or exp Traumatology/ or exp Emergency Medicine/ or exp Emergency Medical Services/ or exp Emergency Service, Hospital/ or exp Critical Care/ or exp Multiple Trauma/ or injur*.ti,ab,kf. or trauma*.ti,ab,kf. or emergenc*.ti,ab,kf. or polytrauma*.ti,ab,kf.) and (child* or schoolchild* or infan* or adolescen* or pediatri* or paediatr* or neonat* or boy or boys or boyhood or girl or girls or girlhood or youth or youths or baby or babies or toddler* or childhood or teen or teens or teenager* or newborn* or postneonat* or postnat* or puberty or preschool* or suckling* or picu or nicu or juvenile?).tw. (219929) 3 1 or 2 (220035) 4 (('focused assessment' adj2 sonography adj2 trauma) or eFAST or 'extended focused asessment').ti,ab,kf. (545) 5 3 and 4 (47) 6 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (432528) 7 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1948940) 8 Epidemiologic studies/ or case control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ or Controlled Before-After Studies/ or Case control.tw. or (cohort adj (study or studies)).tw. or Cohort analy$.tw. or (Follow up adj (study or studies)).tw. or (observational adj (study or studies)).tw. or Longitudinal.tw. or Retrospective*.tw. or prospective*.tw. or consecutive*.tw. or Cross sectional.tw. or Cross-sectional studies/ or historically controlled study/ or interrupted time series analysis/ (Onder exp cohort studies vallen ook longitudinale, prospectieve en retrospectieve studies) (3367896) 9 5 and 6 (5) 10 (5 and 7) not 9 (4) 11 (5 and 8) not (9 or 10) (17) 12 5 not (9 or 10 or 11) (21) 13 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 (47) |

Exclusietabel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Fox, 2011 |

Artikel opgenomen in de SR van Liang (2019) |

|

Holmes, 2017 |

Artikel opgenomen in de SR van Liang (2019) |

|

Calder, 2017 |

Artikel opgenomen in de SR van Liang (2019) |

|

Tummers, 2016 |

Artikel opgenomen in de SR van Liang (2019) |

|

Suthers, 2004 |

Artikel opgenomen in de SR van Liang (2019) |

|

Shwe, 2020 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Riera, 2019 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: Geen structurele vergelijking met/zonder (e-)FAST |

|

Netherton, 2019 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Van Schuppen, 2014 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: geen structurele vergelijking met/zonder (e-)FAST |

|

Menaker, 2014 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: geen vergelijking met/zonder (e-)FAST |

|

Tunuka, 2014 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Kumar, 2014 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Brook, 2009 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Kuncir, 2007 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Holmes, 2007 |

Verouderd review (Liang, 2019 is recenter) |

|

Ollerton, 2006 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Tam, 2005 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Rozycki, 2005 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |

|

Todd Miller, 2003 |

Voldoet niet aan PICO: studie includeert niet alleen kinderen |