Indicaties voor CT-abdomen

Uitgangsvraag

Wat zijn de indicaties voor een CT-abdomen na buiktrauma bij kinderen met potentieel meervoudig of levensbedreigend letsel?

Aanbeveling

Observeer (via monitorbewaking) een patiënt met potentieel intra-abdominaal letsel na stomp buiktrauma aangezien aanvullende diagnostiek vaak niet bijdragend is voor de behandeling. Het merendeel van de letsels herstelt namelijk zonder interventie.

Maak alleen hoogdrempelig een CT-abdomen bij kinderen met potentieel intra-abdominaal letsel (alleen de aanwezigheid van vrij vocht op de e-FAST is geen indicatie voor CT!).

Overweeg (de hemodynamiek in acht nemende) het maken van een CT-abdomen alleen indien de e-FAST positief is, het vervaardigen van een CT-abdomen behandelconsequenties heeft en er sprake is van een van de volgende symptomen:

- Aanwezigheid van een seatbelt sign.

- Peritoneale prikkeling bij lichamelijk onderzoek.

- Verminderde Eye Motor Verbal (EMV < 14) in combinatie met buikpijn.

- Afwijkende X-thorax.

- Verhoogde ASAT waarde.

- Afwijkende pancreasenzymen (gestegen lipase of amylase).

Overweeg bij patiënten met penetrerend abdominaal letsel geen CT-abdomen te maken als er sprake is van:

- Oppervlakkig letsel volgens lichamelijk onderzoek.

- Hemodynamische instabiliteit.

- Evisceratie van de darm.

Maak afspraken binnen het lokale traumanetwerk en stem onderling af waar de CT-abdomen gemaakt wordt indien er een indicatie voor CT-abdomen bestaat. Indien een CT-abdomen wordt gemaakt is het belangrijk deze beelden mee te sturen naar het ontvangend centrum.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het is niet duidelijk wat de waarde is van een CT-abdomen voor de behandeling van een kind na buiktrauma en of deze CT-scan echt noodzakelijk is, aangezien het merendeel van de letsels zonder interventie herstelt. Om te voorkomen dat kinderen onnodig een CT-abdomen ondergaan, die niet bijdragend is in de identificatie van letsels of letsels identificeert die geen behandeling vereisen, is het van belang dat er duidelijkheid bestaat over de indicatie voor het vervaardigen van een CT-abdomen. Het vervaardigen van een CT-abdomen moet behandelconsequenties hebben met in achtneming van het ALARA principe, conform artikel 8.2 en 8.3 van de wet Besluit Basisveiligheidsnormen Stralingsbescherming (Besluit Basisveiligheidsnormen Stralingsbescherming, 2017).

De externe validiteit van verschillende prognostische modellen is onderzocht. Het PedSRC-model en het model van Holmes missen geen abdominaal letsel dat behandeling behoeft in kinderen met meervoudig trauma (Holmes, 2009; Springer, 2019). Deze modellen, maar ook de BATiC-score hebben een negatief voorspellende waarde tussen de 97.5% en 100% (Arbra, 2018; Holmes, 2009; Springer, 2019). Dit wil zeggen dat deze modellen goed in staat zijn om de afwezigheid van abdominaal letsel dat behandeling behoeft te voorspellen. Het model van PECARN geeft echter aan dat er in een enkel geval toch een kind met trauma gemist kan worden ondanks het toepassen van het prognostische model, hoewel de bewijskracht van dit model lager is.

De studies die de impact van het gebruik van een prognostisch model onderzoeken geven aan dat het aantal CT-scans van het abdomen afneemt zodra er een protocol wordt ingevoerd met betrekking tot het voorspellen van abdominaal trauma (Fallon, 2016; Leeper, 2018; Mahajan, 2015; Odia, 2020). De studies laten ook zien dat door toepassing van een dergelijk model de mortaliteit niet verandert en de kosten afnemen (Fallon, 2016). Deze onderzoeken zijn echter nog niet uitgevoerd in een Nederlandse studie.

In de Nederlandse situatie is het gebruikelijk om tijdens de traumaopvang te starten met het maken van een e-FAST. Indien bij de e-FAST aanwijzingen zijn voor intra-abdominaal letsel door het aantonen van vrij vocht, wordt overwogen of nadere diagnostiek geïndiceerd is. Gezien het feit dat de grote meerderheid van letsels na stomp buikletsel herstellen middels een conservatief beleid, maakt dat aanvullende diagnostiek vaak niet bijdragend is voor de behandeling. In Nederland wordt dus nadrukkelijk gebruik gemaakt van de mogelijkheid tot (via monitor bewaakte) observatie als alternatief voor het vervaardigen van een CT-abdomen. Dit is in de buitenlandse setting vaak niet het geval en daar wordt de e-FAST niet als zodanig gebruikt. Dit impliceert dat de gevonden literatuur kans heeft op een andere insteek bij het gebruik van een CT-abdomen bij een traumatisch gewond kind. De werkgroep heeft gemeend deze overweging mee te nemen in haar aanbeveling.

Uit de literatuurstudie komen een aantal klinische predictoren naar voren die de kans op abdominaal letsel vergroten. De predictoren die naar voren komen uit de externe validatie studies zijn in Tabel 5. op een rij gezet.

Tabel 5. Indicatoren die naar voren komen uit het literatuuronderzoek als mogelijke predictoren voor intra-abdominaal letsel bij kinderen. Alleen de studies die een externe validatie hebben uitgevoerd zijn opgenomen in deze tabel

|

Indicator |

Reverences |

|

Clinical signs |

|

|

Abdominal wall trauma or seatbelt sign |

Arbra, 2018; Springer, 2019 |

|

Abdominal tenderness |

Arbra, 2018; Holmes, 2009; Springer, 2019 |

|

Peritoneal irritation |

De Jong, 2014 |

|

Complaints of abdominal pain |

Arbra; 2018; De Jong, 2014; Springer, 2019 |

|

Low age-adjusted systolic blood pressure |

Holmes, 2009 |

|

Hemodynamic instability |

De Jong, 2014 |

|

Decreased breath sounds |

Springer, 2019 |

|

Thoracic wall trauma |

Springer, 2019 |

|

Vomiting after the injury |

Springer, 2019 |

|

EMV-score (<14) (GCS) |

Springer, 2019 |

|

Abnormal chest X-ray |

Arbra, 2018 |

|

Abnormal abdominal ultrasound findings |

De Jong, 2014 |

|

Femur fracture |

Holmes, 2009 |

|

Laboratory values |

|

|

Increased liver enzymes (AST, ALT) |

Arbra, 2018; Holmes, 2009; De Jong, 2014 |

|

Abnormal pancreatic enzymes (amylase or lipase) |

Arbra, 2018; De Jong, 2014 |

|

Abnormal lactate dehydrogenase |

De Jong, 2014 |

|

Abnormal white blood cell count |

De Jong, 2014 |

|

Abnormal creatinine |

De Jong, 2014 |

|

Microscopic hematuria |

Holmes, 2009 |

|

Initial hematocrit level (<30%) |

Holmes, 2009 |

AST: aspartate transaminase, ALT: alanine transaminase, EMV: Eye opening, best Motor response, best Verbal response, CGS: Glasgow Coma Scale, RBC: red blood cells

Omdat een eventueel model bruikbaar moet zijn in de praktijk is het van belang dat er duidelijke indicaties worden opgesteld voor het vervaardigen van beeldvorming van het abdomen middels CT. De werkgroep is dan ook van mening dat de volgende indicatoren toepasbaar zijn voor de Nederlandse praktijk: de aanwezigheid van een seatbelt sign, peritoneale prikkeling bij lichamelijk onderzoek, verminderde EMV (< 14) in combinatie met buikpijn, een afwijkende X-thorax, verhoogde ASAT waarde, afwijkende pancreasenzymen (gestegen lipase of amylase). Dit zijn factoren die in de meeste modellen zijn meegenomen terwijl de overige factoren slechts in enkele modellen zijn opgenomen.

In de geselecteerde literatuur werden alleen patiënten met stomp buiktrauma onderzocht. In 90% van de kinderen met abdominaal trauma is er sprake van stomp buiktrauma (Alzahem, 2017). Indien er sprake is van penetrerend letsel is het regelmatig noodzakelijk om chirurgisch in te grijpen (Alzahem, 2017; Wieck, 2018; Sandler, 2010). De werkgroep is van mening dat een CT-abdomen overgeslagen kan worden bij oppervlakkig letsel, hemodynamisch instabiele patiënten of als er sprake is van evisceratie van de darmen aangezien er dan een indicatie voor operatief ingrijpen bestaat. In de overige groep patiënten zou een CT-abdomen overwogen kunnen worden met dien verstande dat de uitslag van de CT-abdomen leidt tot verandering in beleid anders dan observatie. De werkgroep is daarom van mening dat men terughoudend moet zijn met het maken van een CT-abdomen bij patiënten met penetrerende letsels.

In Nederland zijn de ziekenhuizen onderverdeeld in Level 1, 2 of 3 traumacentra. Wettelijk is vastgelegd dat > 90% van de zwaargewonde kinderen gepresenteerd dient te worden in een Level 1 traumacentrum. De level 1 traumacentra zijn de spil in een netwerk van ziekenhuizen en hebben dientengevolge een verantwoordelijkheid naar de andere centra. Het is echter te verwachten dat deze kinderen ook gepresenteerd worden in een Level 2 of 3 ziekenhuis, waarbij op de e-FAST afwijkingen gevonden worden. In een poging om het aantal overbodige CT-abdomen scans dat gemaakt wordt, zo veel mogelijk te reduceren, is de werkgroep van mening dat op voorhand afspraken gemaakt moeten worden tussen de centra over de routing in het geval een CT-abdomen gemaakt zou moeten worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het vervaardigen van een CT-abdomen brengt extra kosten met zich mee.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het vervaardigen van een CT-abdomen is alleen gerechtvaardigd indien aangenomen wordt dat het potentieel leidt tot een verandering van beleid, bijvoorbeeld een interventie, ingreep of extra observatie van de patiënt. Dit komt doordat een CT-abdomen extra stralingsbelasting met zich meebrengt (zie hiervoor het kopje gebruik van ioniserende straling in de algemene inleiding). Er worden geen problemen verwacht wat betreft de aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en/of implementatie. Er zal een werkprotocol beschikbaar moeten zijn voor het vervaardigen van een CT-scan van het abdomen bij kinderen

Rationale aanbeveling

Uit de literatuurstudie zijn een aantal predictoren naar voren gekomen die gebruikt kunnen worden om te bepalen wanneer een CT-abdomen geïndiceerd is, met als kanttekening dat er praktijkvariatie bestaat in het gebruik van de e-FAST tussen de verschillende landen. De werkgroep hecht er waarde aan dat een CT-abdomen zou moeten zorgen voor een beleidswijziging en niet laagdrempelig gemaakt moet worden om alleen een letsel vast te stellen welke geen beleidswijziging in zich draagt. Door gebruik te maken van de genoemde predictoren, is de kans op het missen van letsel dat behandeling behoeft uitermate klein terwijl de potentieel schadelijke straling zoveel mogelijk wordt beperkt. Nadrukkelijk moet bij de afweging die gemaakt wordt, opname en (bewaakte) observatie als serieus alternatief wordt meegenomen. Hoewel dit niet als zodanig uit de literatuur naar voren is gekomen, kan de mate van hemodynamische stabiliteit worden meegenomen in deze beslissing, zeker indien het kind hemodynamisch stabiel is.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Als een kind opgevangen wordt na een buiktrauma en er vrij vocht gezien wordt op een e-FAST wordt laagdrempelig een CT-abdomen gemaakt. De vraag is wat de waarde is van een CT-abdomen voor de behandeling van een kind en of deze noodzakelijk is aangezien het merendeel van de letsels zonder interventie herstelt. Daarnaast is een CT-abdomen op jonge leeftijd schadelijker dan bij volwassenen omdat het kind langer heeft om een maligniteit te ontwikkelen (levensverwachting is groot) en het kind kwetsbaarder is voor het ontwikkelen van een maligniteit omdat het kind nog in de groeifase is. Om te voorkomen dat veel kinderen een onnodige CT-abdomen krijgen, die niet bijdragend is in het identificeren van letsels die behandeling behoeven, maar wel stralingsbelasting oplevert, kijken we wat indicaties zijn om een CT-abdomen uit te voeren.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1. External validation

Missed injuries (crucial)

|

Low GRADE |

PECARN-model The use of the PECARN prognostic model may result in missing abdominal injuries that require acute intervention in children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Springer, 2019) |

|

High GRADE |

PedSRC-model The use of the PedSRC prognostic model does not result in missing abdominal injuries that require acute intervention in children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Arbra, 2018) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Holmes’ model The use of Holmes prognostic model probably does not result in missing abdominal injuries that require acute intervention in children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Holmes, 2009) |

Model performance (important)

|

Low GRADE |

PECARN-model The PECARN prognostic model had a sensitivity of 99%. Therefore, this model may be used to predict the presence of abdominal injury that require intervention in children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Springer, 2019) |

|

GRADE |

PedSRC-model and BATiC-score The PedSRC prognostic model and BATIC-score both had a negative predictive value of 100%. Therefore, these model can be used to predict the absence of abdominal injury that require intervention in children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Arbra, 2018; de Jong, 2014) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Holmes’ model The prognostic model from Holmes had a negative predictive value of 97.8%. Therefore, this prognostic model can probably be used to predict the absence of abdominal injury in children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (de Jong, 2014; Holmes, 2009) |

2. Model impact

Frequency of CT examinations (crucial)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Clinical prediction rules The use of three different clinical prediction rules probably reduces the amount of abdominal CT-scans performed in children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Fallon, 2016; Leeper, 2018; Odia, 2020) |

|

Moderate GRADE |

PECARN-model The use of the PECARN prognostic model probably reduces the amount of abdominal CT-scans performed in children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Mahajan, 2015) |

Mortality (crucial)

|

Low GRADE |

Clinical prediction rule The use of a clinical prediction rule may not change the mortality among children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Fallon, 2016) |

Costs (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Clinical prediction rule The use of a clinical prediction rule may reduce the diagnostic costs of children with potential multiple trauma.

Sources: (Fallon, 2016) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

1. External validation

PECARN-model

The retrospective cohort study of Springer (2019) determined the sensitivity of the prediction rule proposed by PECARN in identifying patients at very low risk for clinically important intra-abdominal injuries (CIIAI) in their pediatric trauma registry. The initial model was developed by Holmes (2013) to identify children with blunt abdominal trauma who are at very low risk for CIIAI. The prediction rule consists of seven variables regarding patient history and physical examination, without laboratory or ultrasonographic information: evidence of abdominal wall trauma or seat belt sign, GCS score < 14, abdominal tenderness, evidence of thoracic wall trauma, complaints of abdominal pain, decreased breath sounds, and vomiting (Holmes, 2013). Springer (2019) defined CIIAI as: cases resulting in death, therapeutic intervention at laparotomy, angiographic embolization of abdominal arterial bleeding, blood transfusion for abdominal hemorrhage, and administration of intravenous fluid for two or more nights for pancreatic or gastrointestinal injuries. All trauma patients < 16 years of age are evaluated and treated in the children’s hospital, and those from 16 to 18 years of age who do not meet adult level one or two trauma activation criteria. All patients requiring acute intervention were included. In total, 133 patients were included with CIIAI requiring acute intervention. The follow-up period was not reported. The study had a high risk of bias as the study only included patients with abdominal trauma that required acute intervention.

PedSRC-model

Arbra (2018) performed external validation of a clinical prediction rule previously developed by the Pediatric Surgery Research Collaborative (PedSRC) to identify patients at very low risk for abdominal injury in whom abdominal CT-scan safely be avoided. The prediction rule consisted of complaint of abdominal pain, abdominal wall trauma, tenderness or distention on physical examination, abnormal chest x-ray, abnormal pancreatic enzymes, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) over 200 U/L. In patients with no abnormalities in any of the five prediction rule variables, the clinical prediction rule was found to be highly sensitive and had a negative predictive value of 99.4% for abdominal injury and 100% for abdominal injury requiring intervention (Streck, 2017). Arbra (2018) used the PECARN dataset to externally validate the PedSRC clinical prediction rule. The PECARN dataset included pediatric patients with blunt torso trauma who were evaluated at 20 children’s emergency departments from May 2007 until January 2010. In total, 2,435 pediatric blunt abdominal trauma patients were included with a mean age of 9.4 years old (+/- 5.2 years). The follow-up period of the PECARN trial was not reported. The study had a low risk of bias.

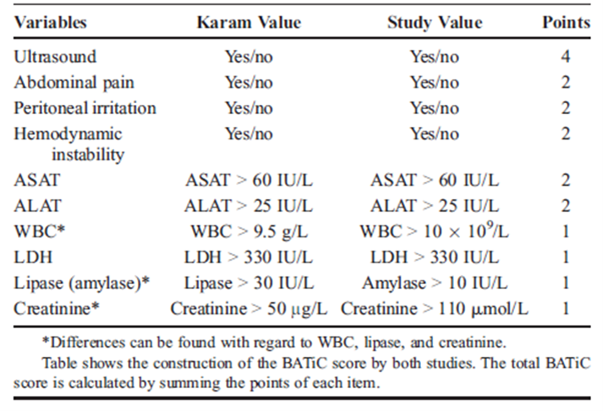

BATiC-score

De Jong (2014) performed external validation of the BATiC-score (see table 3.1), previously identified by Karam et al. (2009). Karam (2009) reported a negative predictive value of 97%. Pediatric trauma patients (< 18 years old) who were admitted to the shock room of the level 1 trauma center University Medical Center Groningen between April 2006 and September 2010 were included. The BATiC-score uses only readily available laboratory parameters, ultrasound results, and results from physical examination and does therefore not carry any risk of additional radiation exposure (Karam, 2009). BATiC-scores were retrospectively computed according to the cut offs described in Table 1. De Jong (2014) used different cut-off values for three of the ten parameters because this was the standard use in their center. These cut-off values are also described in table 3.1. In total, 216 patients were included with a median age of 12 years (range 0 to 17 years). All patients observed without imaging were available for follow-up and there was no clinical suspicion of abdominal injury in any of them. The length of the follow-up period was not specified. The study had a low risk of bias.

Table 1. BATiC cut off points as defined in the initial study (Karam value) and in the study of De Jong (2014) (study value)

Holmes’ prognostic model

The prospective observational study from Holmes (2009) performed a validation of a previously derived clinical prediction rule for the identification of children with abdominal injuries after blunt torso trauma. The clinical prediction rule being evaluated included 6 high-risk variables for abdominal injury: low age-adjusted systolic blood pressure, abdominal tenderness, femur fracture, increased liver enzyme levels (serum aspartate aminotransferase concentration > 200 U/L or serum alanine aminotransferase concentration > 125 U/L), microscopic hematuria (urinalysis > 5 RBCs/high powered field), or an initial hematocrit level less than 30% (Holmes, 2002). Children younger than 18 years who had blunt torso trauma and underwent a definite diagnostic test to evaluate for the presence of an abdominal injury were included. In total, 1,119 patients were included with a mean age of 9.7 years (SD 5.3 years). The follow-up time was not reported. The study has a high risk of bias as patients were only included when a definite diagnostic test was performed to evaluate for the presence of an abdominal injury were included.

2. Model impact

Clinical prediction rules

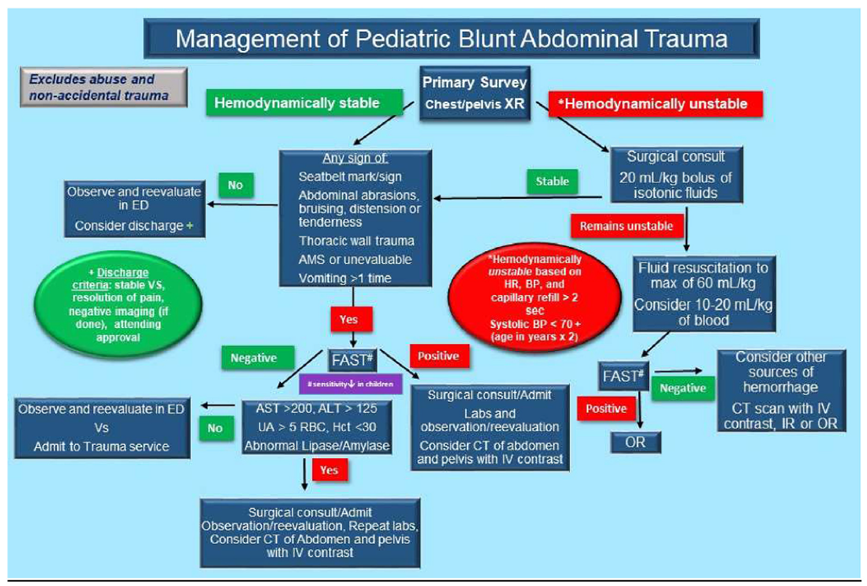

The retrospective cohort study from Odia (2020) evaluated the impact of an evidence-based algorithm on computed tomography (CT) and hospital resource use for hemodynamically stable children with blunt abdominal trauma. The evidence-based clinical algorithm (Figure 3.2) was created using imaging prediction rules for blunt abdominal trauma from the literature, with input from key stakeholders from the divisions of Pediatric Emergency Medicine and Trauma Surgery, and feedback from the faculty. This study compares the CT use and hospital resource use one year before and after implementation of the algorithm. Children ≤ 14 years of age treated in a Level 1 adult and pediatric trauma center were included. In total, 65 children were included in the pre-algorithm implementation group, and 50 in the post-algorithm implementation group. The median age was 8 years (interquartile range (IQR) 5 to 12) in the total cohort with a median injury severity score of 4 (IQR 1 to 6). Primary outcome was the percentage of patients with a CT performed, secondary outcomes were ED length-of-stay (LOS), hospital LOS, and return visits within 7 days. Patients were followed until they were discharged, transferred, or death. The study has a high risk of bias as the number of children included is low and the study did not correct for potential confounders.

Figure 2. Evidence-based clinical decision algorithm for blunt abdominal trauma

CT: computed tomography, BP: blood pressure, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ED: emergency department, FAST: Focused assessment with sonography in trauma, Hct: hematocrit, HR: heart rate, IR: interventional radiology, IV: intravenous, OR: operating room, RBC: red blood cell, UA: urinalysis, XR: radiography. From: Odia (2020)

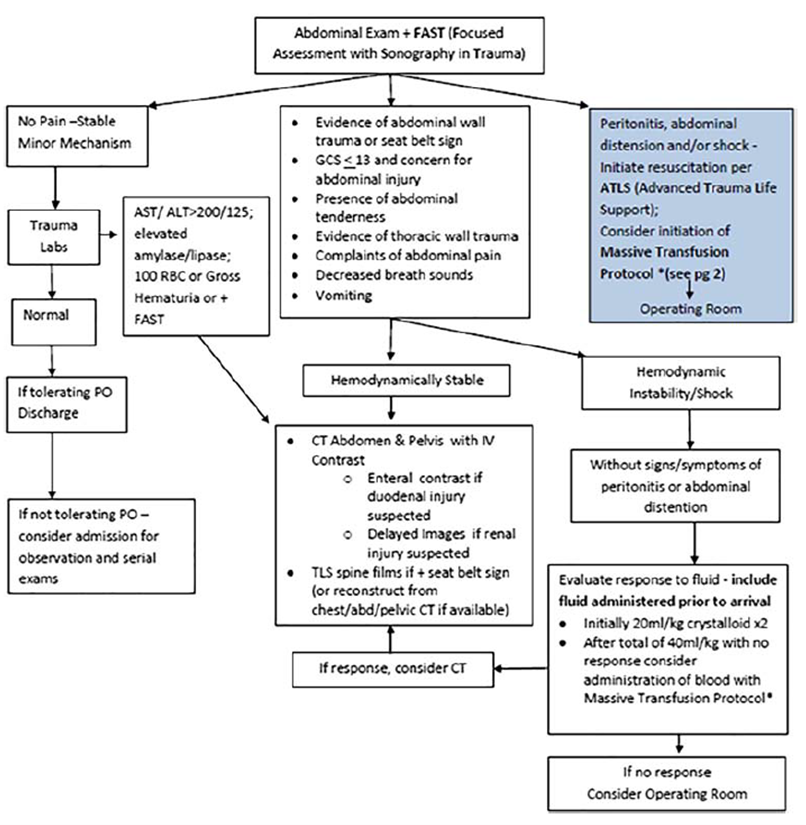

The retrospective observational study from Leeper (2018) evaluated whether the implementation of imaging guidelines reduced the total CT scans without missing clinically significant injury. The imaging guidelines (Figure 3.3) were determined by expert consensus based on the best available literature at the time. The study compared the five years before and after implementation of the screening guidelines. All pediatric patients (age 0 to 17) who were diagnosed with solid organ injury of the liver, kidney, or spleen after blunt trauma mechanism were included. In total, 403 patients were included with a median age of 11 years (IQR 6 to 14). The distribution of the number of patients between the pre- and postimplementation group was not reported. The total follow-up time was not reported. The study has a high risk of bias as the study did not correct for potential confounders and only patients that met one or more criteria for obtaining abdominal CT imaging per institution guidelines were included.

Figure 3. Clinical effectiveness guideline for the imaging and management of pediatric patients with blunt torso trauma

From: Leeper (2018)

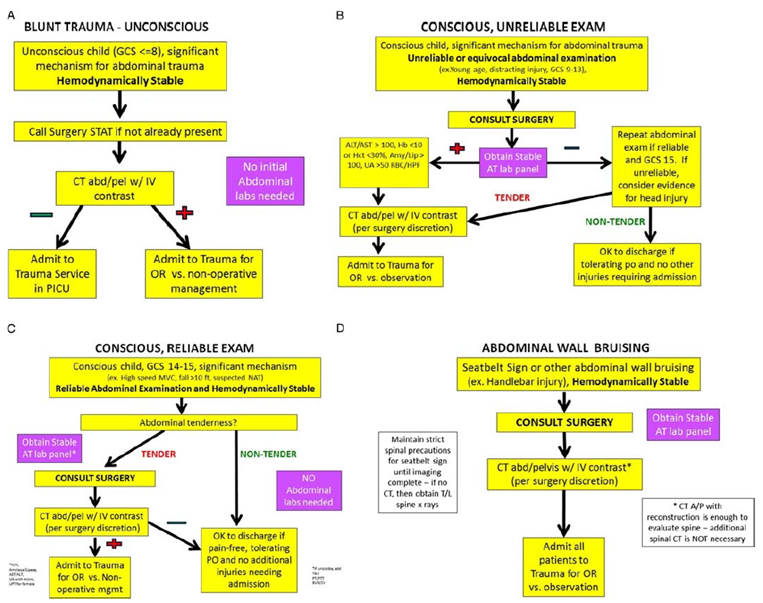

The prospective, longitudinal study of Fallon (2016) evaluated whether the implementation of a protocol to standardize the emergency center management of abdominal trauma in children improved patient safety by decreasing unnecessary CT radiation and improved quality of care by decreasing EC length of stay (LOS) and laboratory costs. The study compared the patients treated during the preimplementation period to those who were treated during two postimplementation periods. The development of the abdominal trauma protocol was a multidisciplinary effort between the trauma surgeons and pediatric emergency medicine physicians. A literature review was performed to identify predictors of injury and for areas in which the evidence was lacking or controversial, a consensus statement was agreed upon. The protocol was based on the mechanism of injury and the ability of the provider to perform an accurate abdominal examination. The final protocol included four categories of patients with suspected blunt abdominal injury (all had to have a significant mechanism for abdominal trauma): (1) unconscious patient, (2) conscious patient with an unreliable examination, (3) conscious patient with a reliable examination, and (4) abdominal wall bruising (Figure 3.4). The protocol emphasizes surgical consultation early on when there is concern for abdominal trauma because we felt that it was important for the trauma surgical team to evaluate all these children to ensure safety and to maximize exposure for surgical trainees within this complex area of pediatric trauma. All patients who had a CT-scan of their abdomen with or without pelvis ordered from the EC for trauma were eligible for inclusion. In total, 321 patients were included: 117 patients were included in the preimplementation period (median age of 8.4, SD 5.2), 148 patients in the first postimplementation period (median age of 9.1, SD 4.8), and 56 patients in the second postimplementation period (median age of 7.8, SD 5.3). Patients were followed during hospital stay and until 48 hours of discharge. The study has a high risk of bias as they did not correct for potential confounders and only patients who had a CT-scan performed were included.

Figure 4. Revised abdominal trauma protocols, including laboratory panels. A: unconscious, B: conscious with unreliable examination, C: conscious, reliable examination, D: abdominal wall bruising

From: Fallon (2016)

PECARN-model

A planned subanalysis of the prospective PECARN trial from Mahajan (2015) compared the test characteristics of clinical suspicion (usual care) with the PECARN prediction rule developed by Holmes (2013) to identify children at risk of abdominal injuries undergoing acute intervention following blunt torso trauma. Abdominal injuries undergoing acute intervention were defined by a therapeutic laparotomy, angiographic embolization, blood transfusion for abdominal hemorrhage, or intravenous fluid administration for 2 or more days in those with pancreatic or gastrointestinal injuries. Patients were considered to be positive for clinical suspicion if suspicion was documented as ≥ 1%. All children younger than 18 years old with blunt torso trauma evaluated at participating PECARN emergency department. Patients were excluded when the injury occurred > 24 hours prior to presentation, penetrating trauma, pre-existing neurologic disorders preventing reliable examination, known pregnancy, or transfer from another hospital with prior abdominal CT-scanning or diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Patients were also excluded when the clinician did not document his or her clinical suspicion of abdominal injury undergoing acute intervention on the data collection form. In total, 11,919 patients were included with a mean age of 11 years old (range 2 days until 17.9 years). Clinicians completed standardized data collection forms prior to abdominal CT (if performed). Patients were followed-up until 1 week after discharge from the emergency department by telephone interview or mail. In case this was unsuccessful, the medical records, ED process improvement records, local trauma registries, and morgue records were reviewed to identify any potentially missed patients with abdominal injuries. The study has a low risk of bias.

Results

1. External validation

Missed injuries (crucial)

The outcome missed injuries due to the application of a prognostic model was reported in three studies (Arbra, 2018; Holmes, 2009; Springer, 2019).

Springer (2019) reported one out of the 133 patients (< 1%) with clinically important abdominal injury that met low-risk criteria during initial chart review. This patient had an adrenal laceration, grade 3 liver laceration. In addition, the patient had a femur fractur and superficial femoral artery damage. Not detecting this patient with a clinically important abdominal injury is considered clinically relevant.

Arbra (2018) reported six (0.7%) patients with abdominal injury in the PECARN dataset that were not identified by the PedSRC clinical prediction model. Abdominal injuries were identified by abdominal CT-scans in all six patients. However, none of these patients’ abdominal injuries required intervention. Therefore, these missed injuries are not considered clinically relevant.

Holmes (2009) reported 8 out of the 365 patients that tested negative for the clinical prediction rule (2.2%) had abdominal injuries. Only one of these eight patients received therapy. This patient underwent a nontherapeutic laparotomy. The patient had a serosal tear and a mesenteric hematoma but did not require therapy during laparotomy. Because this patient received a non-therapeutic laparotomy, missing this injury was not considered clinically relevant.

Model performance (important)

The outcome model performance was reported in four studies (Arbra; 2018; De Jong, 2014; Holmes, 2009; Springer, 2019).

Springer (2019) performed external validation of the PECARN prediction rule and reported a sensitivity of 99% (95%CI 95.9% to 100%). The study did not report enough details to calculate the specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value.

Arbra (2018) performed external validation of the PedSRC prediction rule. 229 out of 235 patients with abdominal injury were predicted correctly, yielding a sensitivity for abdominal injuries of 97.5%. The sensitivity for abdominal injury requiring intervention was 100%. The specificity was 36.9% for abdominal injury and 34.5% for abdominal injury requiring intervention. The NPV of the rule was 99.3% for abdominal injury and 100% for abdominal injury requiring intervention.

De Jong (2014) performed external validation of the BATiC-score and used two cut-off points: When a BATiC score with a cut-off point of 6 (> 6 is abnormal) is used, the sensitivity was 100%, the specificity 87%, the NPV 100% and the PPV 41%; when a BATiC-score with a cut-off point of 7 (> 7 is abnormal) is used, the sensitivity was 89%, the specificity 94%, the NPV 99%, and the PPV 59%.

Holmes (2009) performed external validation of a high-risk prediction rule. 754 out of 1119 patients tested positive for the clinical prediction rule, including 149 patients with abdominal injury. The remaining 365 patients tested negative for the rule, including 8 patients with abdominal injury. This resulted in a sensitivity of 94.9%, specificity of 37.1%, NPV of 97.8%, and PPV of 19.7%.

2. Model impact

Frequency of CT examinations (crucial)

The outcome frequency of CT examinations due to the application of a prognostic model was reported in four studies (Fallon, 2016; Leeper, 2018; Mahajan, 2015; Odia, 2020).

Odia (2020) reported a significantly decreased CT examinations after algorithm implementation from 72.3% to 44%. This corresponds to a 27% decrease of CT examinations, which is considered clinically relevant.

Leeper (2018) reported that the percentage of CT-scans obtained over all trauma admissions decreased significantly when comparing the pre and post protocol time points (17.5% versus 8.7%, p = 0.010). This corresponds to a decrease of CT examinations of 8,8%, which is not considered clinically relevant.

Fallon (2016) did not report the number of CT-scans that were avoided as a result of the implementation of the pediatric abdominal trauma protocol. However, they reported a change of positive CT-scans from the preimplementation period towards the two postimplementation periods: from 23% to 32% to 49%. The rate of clinically significant scans changed as well: from 14% to 22% to 32%. This indicates that application of the guidelines resulted in a higher yield of positive findings, suggesting that less patients with negative scan results underwent CT-scanning.

Mahajan (2015) did not report the number of CT-scans due to the application of a clinical prediction model/ rule, but reported the number of CT-scans that could have been avoided when clinicians practiced according to their reported clinical suspicion. CT-scans were obtained in 3,016 (33%) of the 9,252 patients considered at very low clinical suspicion (< 1%). This suggests an opportunity to reduce unnecessary abdominal CT-scans in children by appropriate use of a clinical prediction rule. The number of abdominal CT-scans that could be avoided would be clinically relevant.

Mortality (crucial)

The outcome mortality due to the application of a clinical prediction model/rule was reported in one study (Fallon, 2016). Fallon (2016) reported no changes in the mortality after the implementation of the trauma protocol.

Costs (important)

The outcome costs due to the application of a prognostic model was reported in one study (Fallon, 2016). Fallon (2016) reported that after the second version of the protocol was implemented the total laboratory costs decreased by 39%. The median cost of laboratory studies remained the same from preimplementation to the first postimplementation period, and decreased after the second protocol revision included an emphasis on laboratory work in the second postimplementation period. The reduction in costs was considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. External validation

Missed injuries (crucial)

PECARN-model

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding patient selection and because of a small study population (imprecision). The resulting level of evidence was therefore low.

PedSRC-model

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was not downgraded. The resulting level of evidence was therefore high.

Holmes’ model

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 1 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding patient selection). The resulting level of evidence was therefore moderate.

Model performance (important)

PECARN-model

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding patient selection and because of a small study population (imprecision). The resulting level of evidence was therefore low.

PedSRC-model and BATiC-score

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was not downgraded. The resulting level of evidence was therefore high.

Holmes’ model

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 1 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding patient selection). The resulting level of evidence was therefore moderate.

2. Model impact

Frequency of CT examinations (crucial)

Clinical prediction rules

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding the lack of correction for potential confounders). The resulting level of evidence was therefore moderate.

PECARN-model

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding selection bias). The resulting level of evidence was therefore moderate.

Mortality (crucial)

Clinical prediction rules

The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding the lack of correction for potential confounders) and because of a small number of patients (imprecision). The resulting level of evidence was therefore low.

Costs (important)

Clinical prediction rules

Because we included prognostic studies, the level of evidence started high. The level of evidence was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias regarding the lack of correction for potential confounders) and because of a small number of patients (imprecision). The resulting level of evidence was therefore low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following questions:

1. What is the predictive value of a prognostic model to predict the occurrence of abdominal injury in children with potential multiple trauma of life threatening injuries?

P: patients children with potential multiple trauma or life threatening injury (< 16 years);

I: intervention using a prognostic model for predicting abdominal injury in an external population;

C: comparison no use of prognostic model for predicting abdominal injury or the use of another prognostic model (care as usual);

O: outcome measure missed injuries, model performance (positive predictive value, negative predictive value):

Timing: after initial trauma admission;

Setting: (pediatric) emergency department.

2. What is the clinical impact of a prognostic model to predict the occurrence of abdominal injury in children with potential multiple trauma of life threatening injuries?

P: patients children with potential multiple trauma or life threatening injury (< 16 years);

I: intervention using a prognostic model for predicting abdominal injury;

C: comparison no use of prognostic model for predicting abdominal injury or the use of another prognostic model (care as usual);

O: outcome measure CT use, mortality, and costs:

Timing: after initial trauma admission;

Setting: (pediatric) emergency department.

Studies investigating the external validity or the impact of a prognostic model were included. Studies were excluded when they described a model that was only internally validated, as these are inferior to the studies that included external validation.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered missed injuries, the frequency of CT examinations, and mortality as critical outcome measures for decision making. The remaining outcome measures were considered important for decision making.

Abdominal injury was defined as injury to any of the following: spleen, liver, urinary tract (kidney to bladder), pancreas, gallbladder, adrenal gland, gastrointestinal tract (including bowel and associated mesentery from the stomach to the sigmoid colon), abdominal vascular structure, or abdominal fascial disruption.

A priori, the guideline committee did not define the outcome measures but used the definitions used in the studies.

The guideline committee considered the following differences as clinically important:

- Any missed abdominal injury that required intervention. Missed abdominal injuries that did not require intervention are not considered clinically important.

- A difference of 10% in mortality rate (RR < 0,91 of > 1,10).

- A minimal difference of 10% in obtained abdominal CT-scans.

- Any reduction in costs was considered clinically relevant.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 22nd of April 2020. The detailed search strategy can be found under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1642 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: primary research on the external validation of a multivariable model or model performance for predicting abdominal injury in children with potential multiple trauma or life threatening injuries. In total, 42 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 34 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 8 studies were included.

Results

In total, 8 observational studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Arbra, C. A., Vogel, A. M., Plumblee, L., Zhang, J., Mauldin, P. D., Dassinger, M. S., Russell, R. T., Blakely, M. L., & Streck, C. J. (2018). External validation of a five-variable clinical prediction rule for identifying children at very low risk for intra-abdominal injury after blunt abdominal trauma. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery, 85(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001933.

- Besluit Basisveiligheidsnormen Stralingsbescherming (2017). Geraadpleegd op 18-11-2020. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0040179/2018-07-01.

- De Jong, W. J., Stoepker, L., Nellensteijn, D. R., Groen, H., El Moumni, M., & Hulscher, J. B. (2014). External validation of the Blunt Abdominal Trauma in Children (BATiC) score: ruling out significant abdominal injury in children. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery, 76(5), 1282–1287. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000175.

- Fallon, S. C., Delemos, D., Akinkuotu, A., Christopher, D., & Naik-Mathuria, B. J. (2016). The use of an institutional pediatric abdominal trauma protocol improves resource use. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery, 80(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000712.

- Holmes, J. F., Sokolove, P. E., Brant, W. E., Palchak, M. J., Vance, C. W., Owings, J. T., & Kuppermann, N. (2002). Identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma. Annals of emergency medicine, 39(5), 500–509. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2002.122900.

- Holmes, J. F., Mao, A., Awasthi, S., McGahan, J. P., Wisner, D. H., & Kuppermann, N. (2009). Validation of a prediction rule for the identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt torso trauma. Annals of emergency medicine, 54(4), 528–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.01.019.

- Holmes, J. F., Lillis, K., Monroe, D., Borgialli, D., Kerrey, B. T., Mahajan, P., Adelgais, K., Ellison, A. M., Yen, K., Atabaki, S., Menaker, J., Bonsu, B., Quayle, K. S., Garcia, M., Rogers, A., Blumberg, S., Lee, L., Tunik, M., Kooistra, J., Kwok, M., … Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) (2013). Identifying children at very low risk of clinically important blunt abdominal injuries. Annals of emergency medicine, 62(2), 107–116.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.11.009.

- Karam, O., Sanchez, O., Chardot, C., & La Scala, G. (2009). Blunt abdominal trauma in children: a score to predict the absence of organ injury. The Journal of pediatrics, 154(6), 912–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.001.

- Leeper, C. M., Nasr, I., Koff, A., McKenna, C., & Gaines, B. A. (2018). Implementation of clinical effectiveness guidelines for solid organ injury after trauma: 10-year experience at a level 1 pediatric trauma center. Journal of pediatric surgery, 53(4), 775–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.05.025.

- Mahajan, P., Kuppermann, N., Tunik, M., Yen, K., Atabaki, S. M., Lee, L. K., Ellison, A. M., Bonsu, B. K., Olsen, C. S., Cook, L., Kwok, M. Y., Lillis, K., Holmes, J. F., & Intra-abdominal Injury Study Group of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) (2015). Comparison of Clinician Suspicion Versus a Clinical Prediction Rule in Identifying Children at Risk for Intra-abdominal Injuries After Blunt Torso Trauma. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 22(9), 1034–1041.

- Odia, O. A., Yorkgitis, B., Gurien, L., Hendry, P., Crandall, M., Skarupa, D., & Fishe, J. N. (2020). An evidence-based algorithm decreases computed tomography use in hemodynamically stable pediatric blunt abdominal trauma patients. American journal of surgery, 220(2), 482–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.01.006.

- Springer, E., Frazier, S. B., Arnold, D. H., & Vukovic, A. A. (2019). External validation of a clinical prediction rule for very low risk pediatric blunt abdominal trauma. The American journal of emergency medicine, 37(9), 1643–1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.11.031.

- Streck, C. J., Vogel, A. M., Zhang, J., Huang, E. Y., Santore, M. T., Tsao, K., Falcone, R. A., Dassinger, M. S., Russell, R. T., Blakely, M. L., & Pediatric Surgery Research Collaborative (2017). Identifying Children at Very Low Risk for Blunt Intra-Abdominal Injury in Whom CT of the Abdomen Can Be Avoided Safely. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 224(4), 449–458.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.041

Evidence tabellen

Evidencetabellen

1. External validation

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Candidate predictors |

Model development, performance and evaluation |

Outcome measures and results |

Comments Interpretation of model |

|

Springer, 2019

Data from the initial model was abstracted from Holmes, 2013. |

Source of data1 and date: retrospective chart review (January 2011 – 2016).

Setting/ number of centres and country: pediatric emergency department in an academic, tertiary care children’s hospital level 1 trauma center, USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. |

Recruitment method2: consecutive patients with correct ICD codes were included.

Inclusion criteria: all trauma patients <16 years of age are evaluated and treated in the children’s hospital, and those from 16 to 18 years of age who do not meet adult level one or two trauma activation criteria. All patients requiring acute intervention were included.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with penetrating trauma, known pregnancy, and pre-existing neurologic disorders precluding reliable examination were excluded from the PECARN cohort. In addition, patients that did not require acute intervention were excluded.

Treatment received? All patients required acute intervention.

Participants: N= 133

Mean age ± SD: 8 (4.4)

Sex: 60% M

Other important characteristics: The most commonly injured organs were bowel or mesentery, liver (median grade 3 (IQR 3,4)), and spleen (median grade 3 (IQR 2,4)). Motor vehicle collisions were the most frequent mechanism of injury. |

Describe candidate predictors3 and method and timing of measurement:

Model: PECARN prediction rule (Holmes, 2013). Data on the predictors was abstracted from Holmes, 2013.

Predictor 1: evidence of abdominal wall trauma or seat belt sign Predictor 2: GCS score <14 Predictor 3: abdominal tenderness Predictor 4: evidence of thoracic wall trauma Predictor 5:complaints of abdominal pain Predictor 6: decreased breath sounds Predictor 7: vomiting

The prediction rule identifies patients with low-risk criteria. The prediction rule consists of patient history and physical examination findings; without laboratory or ultrasonographic information.

Number of participants with any missing value4? Not reported.

How were missing data handled5? NA

|

Development Modelling method6: From Holmes, 2013: binary recursive partitioning, an analytic technique used to develop clinical decision rules when rule sensitivity is most important.

Performance Calibration measures7 and 95%CI: not reported.

Discrimination measures8 and 95%CI: not reported.

Classification measures9: Reported by Holmes, 2013: Sensitivity: 97% Specificity: 42.5% NPV: 99,9% PPV: 2,8% NLR: 0.07

Evaluation Method for testing model performance10: External validation.

|

Type of outcome: single/combined? The outcome abdominal injury was defined according to the definition below.

Definition and method for measurement of outcome: Intra-abdominal injury included any radiographically- or surgically-apparent injury to the following structures: spleen, liver, urinary tract (from the kidney to the urinary bladder), gastrointestinal tract (including the bowel and associated mesentery from the stomach to the sigmoid colon), pancreas, gall bladder, adrenal gland, intra-abdominal vascular structure, or traumatic fascial defect (traumatic abdominal wall hernia).

Endpoint or duration of follow-up: not explicitly reported. However, as data was retrospectively collected based on ICD10 codes, data was collected at least until the final diagnosis was made.

Number of events/outcomes: 133 patients had clinical important intra-abdominal injuries.

RESULTS Multivariable model11:

1/133 patients with intra-abdominal injuries met very low risk criteria. This resulted in a clinical prediction rule sensitivity of 99%, 95% CI (95.9, 100).

Alternative presentation of final model12: not reported. |

Interpretation: exploratory, more research among a larger group of patients is required.

Comparison with other studies? Only included patients with abdominal trauma that required acute intervention.

Generalizability? Only patients who required acute intervention were included for the external validation. Further research is required to be able to apply this prediction rule for all children with possible abdominal trauma. |

|

Mahajan, 2015

Data from the initial model was abstracted from Holmes, 2013. |

Source of data1 and date: prospective observational cohort study (may 2007 to 2010)

Setting/ number of centres and country: 20 emergency departments within the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) in the USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose. This work was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1 R49CE00100201. PECARN is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) Program through the following cooperative agreements: U03MC00001, U03MC00003, U03MC00006, U03MC00007, U03MC00008, U03MC22684, and U03MC22685. |

Recruitment method2: consecutive patients.

Inclusion criteria: The parent study included children younger than 18 years old with blunt torso trauma evaluated at participating PECARN EDs.

Exclusion criteria: injury occurring > 24 hours prior to presentation, penetrating trauma, preexisting neurologic disorders preventing reliable examination, known pregnancy, or transfer from another hospital with prior abdominal CT scanning or diagnostic peritoneal lavage. For this analysis we additionally excluded those patients for whom the clinician did not document his or her clinical suspicion of intra-abdominal injury undergoing acute intervention on the data collection form.

Treatment received? Clinicians completed standardized data collection forms prior to abdominal CT (if performed).

Participants: N= 11,919

Mean age ± SD: 11 years (range 2 days – 17.9 years)

Sex: 61% M

Other important characteristics: 203 patients with intra-abdominal injuries undergoing acute intervention.

|

Describe candidate predictors3 and method and timing of measurement:

Predictor 1: no evidence of abdominal wall trauma or seat belt sign Predictor 2: Glasgow Coma Scale score > 13 Predictor 3: no abdominal tenderness Predictor 4: no evidence of thoracic wall trauma Predictor 5: no complaints of abdominal pain Predictor 6: no decreased breath sounds Predictor 7: no history of vomiting after the injury.

Number of participants with any missing value4? Not reported.

How were missing data handled5? NA. |

Development Modelling method6: From Holmes, 2013: binary recursive partitioning, an analytic technique used to develop clinical decision rules when rule sensitivity is most important.

Performance Calibration measures7 and 95%CI:

Discrimination measures8 and 95%CI:

Classification measures9: Reported by Holmes, 2013: Sensitivity: 97% Specificity: 42.5% NPV: 99,9% PPV: 2,8% NLR: 0.07

Evaluation Method for testing model performance10: NA

|

Type of outcome: single/combined? The outcome abdominal injury was defined according to the definition below.

Definition and method for measurement of outcome: Intra-abdominal injury was defined as any injury identified to the following intra-abdominal structures: spleen, liver, urinary tract (kidney to the urinary bladder), gastrointestinal tract (from the stomach to the sigmoid colon including the mesentery), pancreas, gallbladder, adrenal gland, intra-abdominal vascular structure, or traumatic fascial defect. Intra-abdominal injury undergoing acute intervention was defined by death due to the abdominal injury, surgical intervention at laparotomy, angiographic embolization due to bleeding from the injury, blood transfusion for anemia secondary to intra-abdominal hemorrhage from the injury, or administration of intravenous fluids for at least two nights in those patients with pancreatic or gastrointestinal injuries.

Endpoint or duration of follow-up: We reviewed medical records of all admitted patients and conducted a telephone follow-up survey at least 1 week after the index ED evaluation for those discharged from the ED. If telephone follow-up was unsuccessful, the same follow- up survey was mailed. If this was not returned, we reviewed medical records, ED process improvement records, local trauma registries, and morgue records to identify any potentially missed patients with intra-abdominal injuries.

Number of events/outcomes:

RESULTS Multivariable model11: The derived clinical prediction rule was more sensitive than clinician suspicion, but was less specific.

Abdominal CT scans were obtained in the ED for 2,302 (86%, 95% CI 85% to 88%) of the 2,667 = patients with clinician suspicion = 1%.

Clinicians, however, frequently did not practice in accordance with their reported clinical suspicions, as CT scans were obtained in 3,016 (33%, 95% CI 32% to 34%) of 9,252 = patients considered at very low clinician suspicion (<1%).

Alternative presentation of final model12: |

Interpretation: exploratory, the model is useful for practice, however, the model should be externally validated before the prediction rule can assist in clinical decision-making around abdominal CT use in children with blunt torso trauma.

Comparison with other studies? The study compared a clinical prediction model to clinical suspicion.

Generalizability? The model should first be externally validated before the model is generalizable to other populations outside PECARN.

Clinician suspicion was Documented in all patients (irrespective of the performance of an abdominal CT) and prior to awareness of abdominal CT results if such imaging was performed.

At the time of patient enrolment, clinicians were unaware of the specific variables in the clinical prediction rule, as the rule was not yet derived. |

|

Arbra, 2018

Data from initial model was abstracted from Streak, 2017. |

Source of data1 and date: cohort data from the PECARN study collected from May 2007 through January 2010.

Setting/ number of centres and country: The dataset contained data from children evaluated at 20 children’s emergency departments in the USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest. |

Recruitment method2: Consecutive patients.

Inclusion criteria: pediatric patients with blunt torso trauma who were evaluated at 20 children’s emergency departments from May 2007 until January 2010.

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria for the PECARN study were known pregnancy, patients transferred with a previous diagnostic lavage, pre-existing neurologic disease impacting mental status or abdominal examination and any intra-abdominal injury within 30 days before arrival. Additional exclusion criteria for this analysis were: age > 16 years old, penetrating mechanism of injury, isolated focal head or extremity mechanism, delayed presentation (>6 hours after injury), abdominal CT before arrival, missing data on one of the five variables of the PedSRC clinical prediction model, and laboratory test ordered >6 hours after arrival.

Treatment received? Patients were treated and diagnosed with or without abdominal trauma.

Participants: N=2,435

Mean age ± SD: 9.4 (5.2)

Sex: not reported.

Other important characteristics: The most common mechanisms of injury were motor vehicle collision (MVC) (34.5%), pedestrian or bicyclist struck by a motor vehicle (25.4%), and falls from a significant height (18.9%). |

Describe candidate predictors3 and method and timing of measurement:

Predictor 1: complaints of abdominal pain Predictor 2: abnormal abdominal physical examination Predictor 3: abnormal chest x-ray Predictor 4: abnormal pancreatic enzymes (amylase or lipase) Predictor 5: abnormal AST (>200 U/L)

Number of participants with any missing value4? Patients with missing values were deleted on beforehand.

How were missing data handled5? NA, complete case analysis.

|

Development Modelling method6: Recursive partitioning. They combined clinical and statistical (a Gini splitting technique and 10-fold imputation logistic regression model) to generate a tree.

In addition, multivariable logistic regression was performed.

Performance Calibration measures7 and 95%CI: Not reported.

Discrimination measures8 and 95%CI: Not reported.

Classification measures9: The negative predictive value of the rule was 99.4% for IAI. The negative predictive value of the rule for IAI-I was 100%, as no patient with injury receiving an acute intervention had an absence of all 5 rule variables.

IAI versus. IAI-I Specificity: 98.4% versus. 100% Sensitivity: 38.1% versus. 34.7% PPV: 17.7% versus. 4.3% NLR: 0.04 versus. 0.00

Evaluation Method for testing model performance10: external

|

Type of outcome: single/combined? The outcome abdominal injury was defined according to the definition below.

Definition and method for measurement of outcome: Intra-abdominal injuries included any injuries diagnosed on CT or from operative findings. The definition of IAI receiving an acute intervention (IAI-I) included therapeutic angiographic embolization, therapeutic operation, blood transfusion, and death from IAI.

Endpoint or duration of follow-up: Not reported.

Number of events/outcomes: 235 patients with IAI, 60 with IAI-I.

RESULTS Multivariable model11:

When the five-variable clinical prediction rule was applied to the study population (n = 2,435), 229 patients out of 235 patients with IAI were correctly predicted, yielding a sensitivity for IAI of 97.5%, for IAI-I 100%. The specificity was 36.9% for IAI and 34.5% for IAI-I.

IAI versus. IAI-I NPV: 99.3% versus. 100% PPV: 14.2% versus 3.7% NLR: 0.07 versus. 0.07

Alternative presentation of final model12:

In subset analysis, the prediction rule did not miss any IAI or IAI-I in patients younger than 3 years of age.

The prediction rule had a lower NPV in patients with GCS score 3–8 (95.2%) but identified all patients with IAI requiring an acute intervention. |

Interpretation: confirmatory, model is useful for clinical practice.

Comparison with other studies? External validation of a prediction rule.

Generalizability? Both the initial model and the validation study were performed on a dataset from the USA. Validation in a Dutch setting is required to be sure the rule is generalizable to the Dutch pediatric population. |

|

De Jong (2014)

Data from initial model was abstracted from Karam, 2009. |

Source of data1 and date: cohort of pediatric trauma patients admitted between April 2006 and September 2010.

Setting/ number of centres and country: level 1 trauma center, the Netherlands.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. |

Recruitment method2: Consecutive patients.

Inclusion criteria: Pediatric trauma patients < 18 years old.

Exclusion criteria: patients who sustained penetrating trauma, patients not primarily admitted to our hospital, and patients with five or more missing BATiC variables (of 10).

Treatment received? Yes, all clinical procedures were finished, BATiC scores were retrospectively computed.

Participants: N= 216

Mean age ± SD: 12 (range 0-17)

Sex: 67% M

Other important characteristics: Trauma mechanisms included pedestrians struck (15.3%), falls from height (27.8%), motor vehicle crashes (14.4%), motorcycle crashes (19.9%) and bi cycle crashes (16.7%), as well as miscellaneous mechanisms (6.0%).

|

Describe candidate predictors3 and method and timing of measurement:

Predictor 1: abnormal ultrasound Predictor 2: abdominal pain Predictor 3: peritoneal irritation Predictor 4: hemodynamic instability Predictor 5: ASAT > 60 IU/L Predictor 6: ALAT > 25 IU/L Predictor 7: WBC >10 x 10^9/L Predictor 8:LDH > 330 IU/L Predictor 9: amylase > 10 IU/L Predictor 10: creatinine > 110umol/L

In the shock room, all laboratory values are available within 1 hour after obtaining the samples.

Number of participants with any missing value4? N (%): 400 (18.5%) of data points were missing.

How were missing data handled5? Multiple imputation (5x).

|

Development Modelling method6: From Karam, 2009: ROC curves for the laboratory examinations were used to determine cut off limit.

The variables with NPV ≥ 80% and PPV ≥ 95% were incorporated. The RR of the individual variables was calculated (univariate analysis).

Performance Calibration measures7 and 95%CI: Not reported.

Discrimination measures8 and 95%CI: not reported.

Classification measures9: When applying the BATiC score to our study population, we found a significant difference between the 2 groups, with, respectively, a mean score of 11.1 ± 3.6 for the patients with an intra-abdominal organ injury (n=23) versus 4.4 ± 2.5 for the patients without intra-abdominal organ injury (n = 76)

Using a cut off value of ≤7, the sensitivity was 91%; specificity, 84%; PPV, 64%; and NPV, 97% (95% IC: 89% to 99%). The positive and negative likelihood ratios were 5.69 and 0.11, respectively.

Evaluation Method for testing model performance10: external.

|

Type of outcome: single/combined?

Definition and method for measurement of outcome: Abdominal injury was therefore defined as the presence of intra-abdominal injury on CT scan or during surgical intervention. Patients who did not undergo an abdominal CT scan and had an asymptomatic clinical course were considered not to have abdominal organ injury.

Endpoint or duration of follow-up: not defined.

Number of events/outcomes: 18 patients sustained abdominal injury.

RESULTS Multivariable model11: When a BATiC score with a cut off point of 6 (96 is considered abnormal) is used, the sensitivity was 100% and the specificity was 87%. NPV and PPV were 100% and 41% respectively.

When the cutoff of 7 was used, the sensitivity was 89%, specificity 94%, NPV 99% and PPV 59%.

When a BATiC cutoff value of 6 would have been used, 16 (47%) of the 34 performed abdominal CT scans could have been avoided. When a cutoff value of 7 would have been used, 19 (56%) of 34 would have been unnecessary in the present cohort. This would have led to a decrease in health care costs of €2,368 or €2,812, respectively.

The area under the ROC curve was 0.98 for both cutoff values.

Alternative presentation of final model12: not reported. |

Interpretation: confirmatory, model is useful in practice.

Comparison with other studies? The model is based on univariate analyses, while actually multivariate analyses are preferred.

Generalizability? The study uses external validation in a Dutch population, which makes the results generalizable to the Dutch setting. |

|

Holmes, 2009

Data from initial model was abstracted from Holmes, 2002. |

Source of data1 and date: prospective observational study during a 3-year study period.

Setting/ number of centres and country: level 1 trauma center, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Funded in part by the UC Davis Children’s Miracle Network Research Grant and the SAEM Research Training Grant.

Conflicts of interest are not reported. |

Recruitment method2: Consecutive patients were included.

Inclusion criteria: children younger than 18 years who had blunt torso trauma and underwent a definitive diagnostic test to evaluate for the presence of an intra-abdominal injury.

Exclusion criteria: patients with penetrating trauma, patients who were pregnant, patients who presented more than 24 hours after their traumatic injury, and patients who did not undergo a definitive diagnostic test because of such low clinical suspicion of intra-abdominal injury.

Treatment received? All patients underwent a definite diagnostic test to evaluate for the presence of an intra-abdominal injury.

Participants: N= 1,119

Mean age ± SD: 9.7 (5.3)

Sex: not described.

Other important characteristics:

|

Describe candidate predictors3 and method and timing of measurement:

Predictor 1: low age-adjusted systolic blood pressure Predictor 2: abdominal tenderness Predictor 3: femur fracture Predictor 4: increased liver enzyme levels (serum aspartate aminotransferase concentration 200 U/L or serum alanine aminotransferase concentration 125 U/L), Predictor 5: microscopic hematuria (urinalysis 5 BCs/high powered field) Predictor 6: an initial hematocrit level less than 30%.

The clinical prediction rule being evaluated included 6 “high-risk” variables, the presence of any of which indicated that the child was not at low risk for intra-abdominal injury.

Number of participants with any missing value4? None, only patients with data on all 6 variables in the prediction rule were included (=complete case analysis).

How were missing data handled5? NA. |

Development Modelling method6: From Holmes, 2002. Multiple logistic regression and binary recursive partitioning analyses to identify which physical examination findings and laboratory variables were independently associated with intra-abdominal injury.

Performance Calibration measures7 and 95%CI: The model demonstrated satisfactory goodness- of-fit, as measured by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (P=.58). The area under the model receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.89.

Discrimination measures8 and 95%CI: Not reported.

Classification measures9: Sensitivity: 98% Specificity: 49% PPV: 17& NPV: 99.6%

Evaluation Method for testing model performance10: external

|

Type of outcome: single/combined? Combined: intra-abdominal injury that requires intervention.

Definition and method for measurement of outcome: Intra Abdominal injury was defined as an injury to any of the following abdominal structures, detected by definitive diagnostic testing: spleen, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, adrenal gland, kidney, ureter, urinary bladder, gastrointestinal tract, or an intra-abdominal vascular structure. Any patient with an intra-abdominal injury was considered to require acute specific intervention for the intra-abdominal injury if he or she underwent any of the following: blood transfusion for anemia as a result of intra-abdominal hemorrhage, angiographic embolization of an injured vascular structure or organ, or a therapeutic intervention at laparotomy.

Endpoint or duration of follow-up: Not reported.

Number of events/outcomes: Of the 1,119 enrolled patients, 157 (14.0%; 95% CI 12.0% to 16.2%) had identified intra-abdominal injuries.

RESULTS Multivariable model11: A total of 754 patients tested positive for the clinical prediction rule (ie, positive for any of the 6 components of the rule), including 149 (19.8%; 95% CI 17.0% to 22.8%) with intra-abdominal injury.

Three hundred sixty-five patients tested negative for the rule, including 8 (2.2%; 95% CI 1.0% to 4.3%) with intra-abdominal injury.

The clinical prediction rule had the following other test characteristics: sensitivity = 149 of 157, 94.9% (95% CI 90.2% to 97.8%) and specificity = 357 of 962, 37.1% (95% CI 34.0% to 40.3%).

If the clinical decision rule was strictly applied to the study sample such that abdominal CT scans were not performed if the patient had a negative result for the rule, 365 of the abdominal CT scans would have been avoided.

Alternative presentation of final model12: not reported. |

Interpretation: confirmatory, the model is externally validated.

Comparison with other studies? This study presents a model for high risk patients; while other presented prediction rules for patients with very low risk.

Generalizability? The prediction rule is externally validated, however both internal and external validation was performed in a dataset from the USA. Whether this is also applicable to the Dutch situation remains the question. |

|

Study reference (first author, year of publication)

Classification1

|

Participant selection 1) Appropriate data sources?2 2) Appropriate in- and exclusion?

Risk of bias: low/high/unclear |

Predictors 1) Assessed similar for all participants? 2) Assessed without knowledge of outcome? 3) Available at time the model is intended to be used?

Risk of bias: low/high/unclear |

Outcome 1) Pre-specified or standard outcome definition? 2) Predictors excluded from definition? 3) Assessed similar for all participants? 4) Assessed without knowledge of predictors? 5) Time interval between predictor and outcome measurement appropriate?

Risk of bias: low/high/unclear |

Analysis 1) Reasonable number of participants with event/outcome? 2) All enrolled participants included in analysis? 3) Missing data handled appropriately? 4) No selection of predictors based on univariate analysis? 5) Relevant model performance measures evaluated appropriately?3 6) Accounted for model overfitting4 and optimism? 7) Predictors and weights correspond to results from multivariate analysis?

Risk of bias: low/high/unclear |

Overall judgment

High risk of bias: at least one domain judged to be at high risk of bias.

Model development only: high risk of bias.

Risk of bias: low/high/unclear |

|

Springer, 2019

External validation of model |

Risk of bias: high

Only patients with abdominal trauma requiring acute intervention were included. |

Risk of bias: low

Retrospective analysis of risk factors. |

Risk of bias: low

Retrospective analysis of risk factors to predict the outcome. |

Risk of bias: low

|

Risk of bias: high |

|

Mahajan, 2015

Model impact |

Risk of bias: low

|

Risk of bias: low

Clinician suspicion was documented in all patients (irrespective of the performance of an abdominal CT) and prior to awareness of abdominal CT results if such imaging was performed.

At the time of patient enrolment, clinicians were unaware of the specific variables in the clinical prediction rule, as the rule was not yet derived. |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

|

Arbra, 2018 |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

|

De Jong (2014) |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

|

Holmes, 2009 |

Risk of bias: high

Only patients with a definite diagnostic test to evaluate for the presence of an intra-abdominal injury were included. |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: low |

Risk of bias: high |

2. Model impact

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Odia, 2020 |

Type of study: retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: before-after design in level 1 adult and pediatric trauma setting and its associated emergency department that serves a large geographic area encompassing approximately 15 counties in the USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest: none. |

Inclusion criteria: This study included patients 14 years and younger who were evaluated for BAT and were hemodynamically stable.

Exclusion criteria: hemodynamically unstable patients (defined a priori as hypotension for age and/or Glasgow Coma Score <10. We also excluded patients who were victims of penetrating trauma or who transferred from an outside institution with CTAP already performed.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 65

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 9.5 (IQR 5-13) C: 7 (IQR 4-10)

Sex: I: 64.0% M C: 55.4% M

Groups comparable at baseline? As between the pre- and post-cohorts, there were no significant differences in injury severity scores (ISS) (p = 0.47). Significantly more patients in pre cohort had abdominal guarding on exam (p =0.005), while significantly more patients in the post-cohort (p = 0.003) had a seatbelt sign on exam. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Post-algorithm implementation

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Pre-algorithm implementation

|

Length of follow-up: data was obtained from patients who were admitted, until discharge, until they were transferred or until they died.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

CTAP utilization CTAP utilization significantly decreased after algorithm implementation from 72.3% to 44% (p = 0.002), with no significant difference in CTAP findings of IAI. The unadjusted and adjusted odds of a pediatric BAT patient receiving a CTAP post-implementation were 0.3 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.1-0.6) and 0.2 (95% CI 0.07-0.67), respectively.

ED trauma center LOS ED/trauma center LOS significantly decreased after algorithm implementation from 256 min to 203 min (p = 0.003).

Hospital length of stay Despite the decrease in CTAP imaging, there was no significant increase in hospitalization rates in the post cohort, however post cohort patients who were admitted did have a significantly longer hospital LOS (2-3 days, p < 0.001).

Changes in clinical course There were no statistically significant differences in patients who received surgery or other interventions, nor differences in 7-day return visits after the BAT algorithm was implemented.

Missed injuries There were no major missed IAIs in the post cohort that did not receive a CTAP during the initial evaluation. However, there was a case in the post cohort of a 12-year old male who was admitted for observation, became more tachycardic after admission, and a subsequent CTAP scan showed a hollow viscus injury. He underwent a laparotomy for bowel resection and repair and recovered uneventfully. |

Generalizability? The model was developed and tested in only 1 hospital and associated emergency departments covering 15 counties in the USA. Whether the model is also applicable in the Netherlands remains questionable. |

|

Leeper, 2018 |

Type of study: retrospective cohort study

Setting and country: before-after design in level 1 pediatric trauma setting, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: nothing reported on funding, conflicts of interest: none. |

Inclusion criteria: All pediatric patients (age 0-17) who were diagnosed with solid organ injury of the liver, kidney, or spleen after blunt trauma mechanism were included.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they were transferred from another hospital with diagnosis of solid organ injury based on CT scan from that location, as this study focuses on the impact of imaging guidelines on decision making in their institution.

N total at baseline: 403 patients, not reported how many in the intervention and control group.

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: 11 (IQR 6 – 14)

Sex: 30.5% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Unknown, not reported. |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Post imaging guidelines implementation.

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Pre imaging guidelines implementation. |

Length of follow-up: Not reported.

Loss-to-follow-up: Not reported.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported.

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

CT examinations The percentage of CT scans obtained over all trauma admission decreased Significantly when comparing pre and post protocol time points (17.5% versus 8.7%, p = 0.010) (Fig. 2).

High and low-grade injury diagnoses There was a significant difference in the median percentage diagnosed with low grade injury between pre and post protocol implementation, with fewer low grade being captured after implementation of the screening guidelines (1.3% versus 0.6%; p = 0.019) (Fig. 3). However, there was no difference in the median percentage of high grade injuries diagnosed between the same two time periods (1.3% versus 1.1%; p = 0.394). (See Fig. 4.) |

Generalizability? The model was developed and tested in only 1 hospital in the USA. Whether the model is also applicable in the Netherlands remains questionable. |

|

Fallon, 2016 |

Type of study: prospective cohort study

Setting and country: level 1 pediatric trauma center, USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: All patients who had a CT scan of their abdomen with or without pelvis ordered from the EC for trauma were eligible for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria included neonates, patients presenting with a CT obtained at the transferring institution, suspected patients of nonaccidental trauma, and remote injuries greater than 24 hours before presentation.

N total at baseline: Intervention 1: 148 Intervention 2: 56 Control: 117

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I1: 9.1 (SD 4.8) I2: 7.8 (5.3) C: 8.4 (5.2)

Sex: I1: 63% M I2: 55% M C: 61% M